Abstract

Background

A premise of this study was that different psychological processes would predict the initiation and maintenance of weight loss after surgery for morbid obesity. Our aim was to examine whether more favorable preoperative expectations of psychosocial outcomes predict weight loss in the first year after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) and whether postoperative satisfaction with these outcomes predicts weight maintenance in the second year after the operation.

Methods

Six months before and 1 year after surgery, the “Obesity Psychosocial State Questionnaire” was filled out by 91 patients (77 female, 14 male, mean age 45 ± 9 years, mean preoperative body mass index 47 ± 6 kg/m2). We evaluated the preoperative outcome expectations and the postoperative satisfaction for the seven domains of psychosocial and physical functioning of this questionnaire, as well as the correlations between these scores and both weight loss and weight maintenance.

Results

Patients showed high satisfaction with psychosocial outcomes after LAGB in all seven domains (p < 0.001), even though the improvement was less than expected in five of the domains (p ≤ 0.01). While weight loss 1 year after the operation was related to satisfaction with psychosocial outcomes (p ≤ 0.05), preoperative expectations were not related to weight loss in the first year after surgery, and satisfaction with the outcomes was not related to weight maintenance in the second year after surgery.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that surgically induced effects of weight loss and weight maintenance are achieved independently of the patient’s preoperative expectations of and postoperative satisfaction with the psychosocial outcomes.

Keywords: Morbid obesity, Obesity, Bariatric surgery, Body mass index, Weight loss, Satisfaction, Health psychology, Health behavior, Expectation

Introduction

Morbid obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) of 40 kg/m2 or higher, is a life-threatening condition with prevalent comorbidity and severely reduced quality of life [1]. Although surgery is considered to be the treatment of choice for morbid obesity [2], it is not a panacea that makes lifestyle changes superfluous. Not all patients will achieve a successful weight outcome [3–5], and a number of patients will fail to adopt healthy and enduring dietary changes following surgery [6, 7].

Within the field of health psychology, it has been proposed that health behavior may depend on outcome expectations and satisfaction with the outcome. One model is based on the premise that the initiation and maintenance of behavior change involve different decision processes [8]. Positive expectations of the consequences of behavior change are thought to guide the initiation of health behavior, whereas satisfaction with the outcome guides decisions on maintenance of health behavior [9]. According to this model, initiation can be considered an “approach”-based, self-regulated process in which people strive to reduce the discrepancy between their current state and their desired state [8–11], whereas maintenance can be regarded as an “avoidance”-based, self-regulated process in which people strive to maintain the discrepancy between their favorable current state and an undesired prior state [9, 10].

Especially in nonsurgical weight loss interventions, higher outcome expectations are associated with increased weight loss [12–14], a finding that was not confirmed in one study evaluating a surgical intervention [15]. While a qualitative study [16] and a pilot study [4] both suggested that satisfaction is associated with weight loss maintenance, a quantitative study did not confirm these observations [17]. One aspect of expectation and satisfaction is the disparity between them, i.e., the extent of unfulfilled expectations. In general, patients tend to have unrealistic expectations with respect to the outcome of bariatric surgery [18]. In nonsurgical weight loss interventions, these unrealistic expectations have been shown to be linked to higher attrition [19], lower satisfaction [12], and less healthy psychological and eating behavior characteristics [13] but not to maintenance of weight loss [12, 17]. In the current study, the prognostic effects of expectations, satisfaction and unfulfilled expectations are disentangled.

Although weight loss is an obvious outcome of surgery for morbid obesity, it is not the ultimate goal patients want to achieve [18]. Instead, weight loss is a means to achieve goals such as the improvement of physical function, mental health, physical appearance, self-efficacy regarding eating and weight control, social acceptance, intimacy, and social contacts. The purpose of our study was to examine the preoperative expectations of achieving these psychosocial outcomes and the satisfaction with these outcomes as predictors of weight loss and weight loss maintenance following laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) for severe obesity. Our hypotheses were that (1) more favorable preoperative expectations with respect to psychosocial states after the operation would promote weight loss at 1 year after LAGB and (2) more satisfaction with the psychosocial outcomes 1 year after the operation would predict weight loss maintenance at 2 years after LAGB. Related to these hypotheses is the expectation that (3) a greater extent of “unfulfilled expectations” with respect to the psychosocial outcomes could be linked to more weight loss at 1 year and less weight maintenance at 2 years after LAGB.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedure

Between October 2000 and April 2004, 156 patients were subjected to a LAGB procedure at the St. Antonius Hospital Nieuwegein, the Netherlands, using the Lap-Band® system (INAMED Health, Santa Barbara, CA, USA), following screening by a bariatric surgeon, an endocrinologist, a psychologist, and a dietician. Surgical indications were a BMI ≥ 40 or a BMI between 35 and 40 with serious comorbidity. The operation was performed according to the techniques described by Belachew et al. [20]. The study protocol was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the hospital.

Of the 156 patients who underwent surgery, 134 attended a preoperative meeting during which they were asked to participate in this prospective questionnaire study. Seven patients who attended the meeting did not return a signed informed consent form, and four patients underwent surgery before the researcher had sent out the preoperative questionnaire, resulting in 123 eligible patients.

Of these patients, 113 (92%) filled out questionnaires before the operation. After surgery, two patients underwent a gastric bypass, three patients withdrew participation due to severe psychopathology, and 17 patients had incomplete weight records 1 or 2 years after the operation or did not return the questionnaire 1 year after the operation. There were no differences in gender, age, and mean BMIs between the 91 patients with complete records and the 32 eligible patients with incomplete records (p values > 0.27).

The 91 participating patients consisted of 77 women and 14 men with a mean age of 45 ± 9 years. The highest level of education attained by the patients was: primary education seven patients, secondary education 75 patients, and tertiary education nine patients. The mean BMIs 6 months before the operation and 1 and 2 years after the operation were 47 ± 6, 37 ± 7, and 36 ± 7, respectively.

Instruments

The actual, expected, and past psychosocial states were measured using the “Obesity Psychosocial State Questionnaire” (OPSQ) [21]. The OPSQ measures seven domains: “physical function” (15 items, e.g., “to kneel or stoop easily”), “mental well-being” (six items, e.g., “to feel depressed”), “physical appearance” (nine items, e.g., “to feel fat when photographed”), “social acceptance” (four items, e.g., “to be singled out because of my weight”), “self-efficacy regarding eating and weight control” (three items, e.g., “to feel helpless about my eating behavior”), “intimacy” (four items, e.g., “to have sexual problems because of my weight”), and “social network” (two items, e.g., “to visit friends and acquaintances”). The questionnaire has a five-point Likert rating format, ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The psychometric characteristics of the OPSQ, established in a sample of 287 patients before and after (surgical or dietary) treatment for (severe) obesity, are satisfactory [21].

Procedure

The OPSQ questionnaire was filled out by the patients 6 months before and 1 year after the operation. Six months preoperatively, patients were asked (A) to what extent the item had applied to them in the past 2 months and (B) how they expected the item would apply to them about 1 year after the operation. One year after the operation, the patients were asked (C) to what extent the item had applied to them in the past 2 months and (D) to what extent the item had applied to them before the operation.

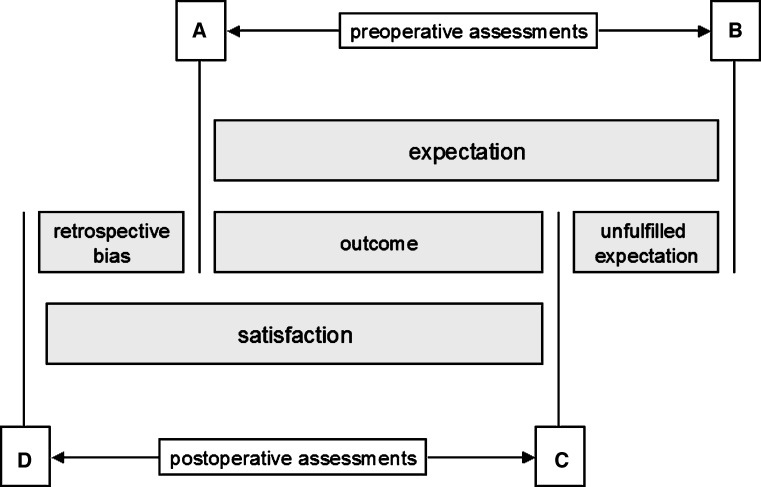

Figure 1 shows the definitions of this study. The two main definitions—preoperative outcome expectation (B − A) and postoperative satisfaction (C − D)—are composed of three other definitions: improvement (C − A), unfulfilled expectation (B − C), and retrospective bias (A − D).

Fig. 1.

Diagram showing the definitions used in this study. Six months preoperatively, the patients indicated (A) their current psychosocial state and (B) their expected psychosocial state 1 year after the operation. One year after the operation, the patients indicated (C) their current psychosocial state and (D) the retrospective judgment of their psychosocial state before the operation. The preoperative outcome expectation, i.e., the discrepancy between the current preoperative state and the expected postoperative state (B − A), is composed of the improvement (C − A) combined with the unfulfilled expectation (B − C). The postoperative satisfaction, i.e., the discrepancy between the current postoperative state and an undesired preoperative state (C − D), is composed of the improvement (C − A) combined with retrospective perception bias (A − D)

Statistical Analyses

Weight loss in the first and second years after the operation was defined as the percentage of excess body mass index lost (%EBL) according to standard procedures [22]. Weight loss maintenance in the second postoperative year was defined as the difference between %EBL at 1 and 2 years after the operation.

The Wilcoxon signed ranks test was used to compare the number of patients who obtained a negative, zero, or positive score for preoperative outcome expectations, postoperative satisfaction, and unfulfilled expectations.

The score distributions of the psychosocial state and weight loss variables were normal [23]. Pearson correlations were calculated to determine whether preoperative outcome expectations, postoperative satisfaction, and unfulfilled expectations were related to weight loss in the first year after surgery and to weight loss maintenance in the second year after surgery.

In ancillary analyses, Pearson correlations were used to examine the relationship of the current state before the operation (A), the expected state after the operation (B), the current state after the operation (C), and the retrospective appraisal of the state before the operation (D) with weight loss in the first year and weight maintenance in the second year after the operation.

All analyses were performed with SPSS 15.0 (Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

The mean percentage of excess BMI loss was 46 ± 22 (range 7 to 106) in the first year and 51 ± 26 (range −9 to 122) in the first 2 years. The mean excess BMI loss in the second year minus excess weight loss in the first year was 5 ± 14 (range −39 to 39).

Analysis of Frequencies

Table 1 shows the number of patients who obtained a negative, zero, or positive score on outcome expectations, satisfaction, and unfulfilled expectations. The “social network” variable was a two-item variable with only a few possible scores, which explains the relatively large number of patients who obtained a zero score for this variable. The vast majority of patients had a positive outcome expectation before the operation and was satisfied with the psychosocial outcome after the operation (p < 0.001 in all cases). Analyses of “unfulfilled expectations” showed that preoperatively, more patients had been too optimistic than too pessimistic about five postoperative outcomes (p < 0.01). For “mental well-being” (p = 0.12) and “social network” (p = 0.81) the number of too optimistic and too pessimistic patients did not significantly differ.

Table 1.

The number of patients (out of a total of 91) who obtained a negative (−), zero (0), or positive (+) score on preoperative outcome expectations, postoperative satisfaction, and unfulfilled expectations

| Psychosocial states | − | 0 | + | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative outcome expectations (B − A) | ||||

| Physical function | – | – | 91 | <0.001 |

| Mental well-being | 1 | 13 | 77 | <0.001 |

| Physical appearance | 1 | – | 90 | <0.001 |

| Social acceptance | 2 | 7 | 82 | <0.001 |

| Self-efficacy | 1 | 2 | 88 | <0.001 |

| Intimacy | 1 | 13 | 77 | <0.001 |

| Social network | 4 | 38 | 49 | <0.001 |

| Postoperative satisfaction (C − D) | ||||

| Physical function | 6 | 1 | 84 | <0.001 |

| Mental well-being | 6 | 10 | 75 | <0.001 |

| Physical appearance | 2 | 3 | 86 | <0.001 |

| Social acceptance | 2 | 10 | 79 | <0.001 |

| Self-efficacy | 1 | 4 | 86 | <0.001 |

| Intimacy | 3 | 18 | 67 | <0.001 |

| Social network | 3 | 44 | 44 | <0.001 |

| Unfulfilled expectations (B − C) | ||||

| Physical function | 28 | 3 | 60 | <0.001 |

| Mental well-being | 35 | 13 | 43 | 0.12 |

| Physical appearance | 17 | 4 | 70 | <0.001 |

| Social acceptance | 24 | 12 | 55 | <0.001 |

| Self-efficacy | 19 | 13 | 59 | <0.001 |

| Intimacy | 32 | 8 | 48 | 0.004 |

| Social network | 30 | 28 | 33 | 0.49 |

A positive (+) score indicates that the patient preoperatively expects a good outcome, is postoperatively satisfied with the outcome, or appraises the postoperative state as worse than expected before the operation.

Correlational Analyses

Table 2 shows the correlations of outcome expectations, satisfaction, and unfulfilled expectations for the seven psychosocial states with weight loss in the first year after the operation and with weight loss maintenance in the second year after the operation.

| Psychosocial states | Weight loss | Weight loss maintenance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r value | p value | r value | p value | |

| Preoperative outcome expectations (B − A) | ||||

| Physical function | 0.01 | 0.90 | 0.03 | 0.75 |

| Mental well-being | 0.06 | 0.60 | 0.14 | 0.18 |

| Physical appearance | 0.02 | 0.89 | 0.14 | 0.19 |

| Social acceptance | −0.07 | 0.50 | 0.07 | 0.53 |

| Self-efficacy | 0.08 | 0.45 | 0.07 | 0.54 |

| Intimacy | 0.07 | 0.50 | −0.15 | 0.16 |

| Social network | 0.09 | 0.41 | 0.23 | 0.03 |

| Postoperative satisfaction (C − D) | ||||

| Physical function | 0.39 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.96 |

| Mental well-being | 0.37 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.51 |

| Physical appearance | 0.52 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.93 |

| Social acceptance | 0.54 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.89 |

| Self-efficacy | 0.43 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.60 |

| Intimacy | 0.38 | <0.001 | 0.04 | 0.72 |

| Social network | 0.21 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.89 |

| Unfulfilled expectations (B − C) | ||||

| Physical function | −0.31 | 0.002 | 0.03 | 0.75 |

| Mental well-being | −0.27 | 0.009 | −0.01 | 0.90 |

| Physical appearance | −0.31 | 0.003 | 0.09 | 0.39 |

| Social acceptance | −0.28 | 0.007 | −0.06 | 0.57 |

| Self-efficacy | −0.25 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.97 |

| Intimacy | −0.12 | 0.26 | −0.04 | 0.69 |

| Social network | −0.24 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.80 |

Preoperative Outcome Expectations

Neither weight loss in the first year after the operation nor weight loss maintenance in the second year after the operation was significantly correlated to any of the preoperative outcome expectations for the seven psychosocial states, with only one exception. The expectation of an improved social network was correlated with a better maintenance of weight loss in the second year after the operation (r = 0.23, p = 0.03).

Postoperative Satisfaction

Weight loss in the first year after the operation was correlated significantly with postoperative satisfaction for all psychological states. Patients who had lost more weight felt most satisfaction. Two correlations were large (r > 0.50): Patients who lost more weight were more satisfied with both their “physical appearance” (r = 0.52; p < 0.001) and “social acceptance” (r = 0.54; p < 0.001). Weight loss maintenance in the second year after the operation was not related to the satisfaction of any of the seven psychosocial states.

Unfulfilled Expectations

Less weight loss in the first year after the operation was significantly correlated with higher unfulfilled expectations for six of the seven psychosocial states. Patients with less weight loss had expected to improve more on these psychosocial states than they actually did. Weight loss maintenance between the first and second years was not correlated with unfulfilled expectations for the seven psychological states.

Ancillary Analyses

To further insight into the correlation between weight loss and psychosocial states, we correlated the four scores that were used to define preoperative outcome expectations, postoperative satisfaction, and unfulfilled expectations with weight loss in the first year after the operation and with weight loss maintenance in the second year after the operation.

Weight loss in the first year after the operation was correlated with neither the psychosocial states before the operation (A; correlations varied from r = −0.15, p = 0.17 to r = 0.15, p = 0.16) nor the postoperative psychosocial states expected after the operation (B; correlations varied from r = −0.12, p = 0.24 to r = 0.16, p = 0.14).

More weight loss in the first year correlated with a better score on five of the seven psychological states after the operation (C): physical function, r = 0.39, p < 0.001; mental well-being, r = 0.25, p = 0.02; physical appearance, r = 0.37, p < 0.001; social acceptance, r = 0.40, p < 0.001; and self-efficacy, r = 0.33, p = 0.001.

Weight loss in the first year was correlated with retrospective appraisals of one psychosocial state before the operation (D): self-efficacy, r = −0.25, p = 0.02. The patients with less weight loss reported retrospectively the most positive appraisal of self-efficacy before the operation.

None of the scores of the participants (A, B, C, or D) correlated with weight loss maintenance in the second year after the operation.

Discussion

Our study did not confirm the hypotheses that preoperative outcome expectations and postoperative outcome satisfaction can predict weight loss and weight loss maintenance after LAGB. Assets of this study are the prospective design, the use of an obesity-tailored quality-of-life instrument, and the comprehensive definition of current, predictive, and retrospective evaluations of psychosocial states.

Many theories in the field of health psychology reflect the idea that positive outcome expectations guide decisions to initiate behavior change, for example the “Health Belief Model” [24], “Theory of Planned Behavior” [25], “Stages of Change (transtheoretical) Model” [26], and “Social Cognitive Theory” [27]. These theories, as well as the observation that positive outcome expectations predict the outcome of nonsurgical weight loss interventions [12–14], led to our first hypothesis that favorable preoperative expectations with respect to the psychosocial outcomes after LAGB would promote postoperative weight loss at 1 year. As shown in another study on bariatric surgery patients [15], the hypothesis was not confirmed. This suggests that, during the weight loss phase after bariatric surgery, the effect of the gastric banding on weight loss is more important than the supporting effect of psychological variables on the weight loss. While the idea that positive outcome expectations guide decisions to initiate behavior change appears to apply to heterogeneous groups with less severe obesity, this idea did not apply to our group in which the surgical intervention was a final solution after a long history of unsuccessful behavioral attempts to lose weight.

Our definition of outcome expectation included two components: the actual improvement and the unfulfilled expectations. The latter overlaps with definitions of “unrealistic optimism,” which has been considered a common, healthy, and adaptive human characteristic [28] that is thought to guide decisions to initiate behavior change [9]. In agreement with a previous study [17], the weight loss-related psychosocial benefits in our patients were smaller than expected. For six variables, a greater degree of unfulfilled expectation was correlated with less weight loss. This suggests that unrealistic expectations are associated with a poor psychosocial outcome. However, this suggestion was not supported by our results. Ancillary analyses demonstrated that the degree of weight loss was correlated with the actual psychosocial state after the operation but not with the postoperative psychosocial state that was expected preoperatively. In our morbidly obese group of patients who applied for an operation, it proved impossible to predict weight outcome based on expectations before the surgical intervention.

In line with the psychological theory that people strive to maintain a discrepancy between their favorable current state and an undesired prior state [10, 16], our second hypothesis was that increased satisfaction with the psychosocial outcome at 1 year would predict weight loss maintenance at 2 years after LAGB. We included in our definition of satisfaction the postoperative appraisal of the preoperative situation as a reflection of an undesired prior state. The retrospective perception of the preoperative situation is considered more important for current satisfaction than the actual situation before the operation. The hypothesis was not confirmed; satisfaction with the psychosocial outcome after 1 year did not predict weight loss maintenance in the year thereafter. Ancillary analyses showed that five of the seven perceived psychosocial states 1 year after the operation were linked to weight loss during the first but not the second year. This result suggests that a favorable psychosocial outcome is a consequence of weight loss, rather than the converse situation in which psychosocial states predict weight loss or weight loss maintenance after LAGB.

The findings of our prospective study with respect to the prediction of weight loss maintenance only apply to the relatively short 2-year follow-up. Some patients regain weight from 2 years after bariatric surgery [5, 29]. Our analyses do not refute the possibility that dissatisfaction with the psychosocial outcome impedes long-term weight loss maintenance. Since there were no significant differences in either demographic characteristics or weight between those who participated in our study and those who declined participation, it is unlikely that the generalizability of the findings is hampered by the patients who declined participation in the study.

In agreement with previous observations [30, 31], our study suggests that it is difficult to predict the postoperative weight outcome based on preoperative psychological variables. The operation is necessary to be able to discover who will and who will not need psychological guidance to achieve a successful outcome. Our study indicates that weight loss after the operation leads to satisfaction with the achieved psychosocial outcomes. The surgically induced effects of weight loss and short-term weight loss maintenance are achieved independently of patients’ preoperative expectations and postoperative satisfaction with the psychosocial outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Van Nunen AM, Wouters EJ, Vingerhoets AJ, et al. The health-related quality of life of obese persons seeking or not seeking surgical or non-surgical treatment: a meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2007;17:1357–1366. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9241-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brolin RE. Update: NIH consensus conference. Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity. Nutrition. 1996;12:403–404. doi: 10.1016/S0899-9007(96)00154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchwald H, Williams SE. Bariatric Surgery Worldwide 2003. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1157–1164. doi: 10.1381/0960892042387057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsu LK, Benotti PN, Dwyer J, et al. Nonsurgical factors that influence the outcome of bariatric surgery: a review. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:338–346. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larsen JK, Van Ramshorst B, Geenen R, et al. Binge eating and its relationship with outcome after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1111–1117. doi: 10.1381/0960892041975587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karlsson J, Sjöström L, Sullivan M. Swedish obese subjects (SOS). An intervention study of obesity. Two-year follow-up of health-related quality of life (HRQL) and eating behavior after gastric surgery for severe obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:113–126. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Latner JD, Wetzler S, Goodman ER, et al. Gastric bypass in a low-income, inner-city population: eating disturbances and weight loss. Obes Res. 2004;12:956–61. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rothman AJ. Toward a theory-based analysis of behavioral maintenance. Health Psychol. 2000;19:64–69. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.Suppl1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King CM, Rothman AJ, Jeffery RW. The Challenge study: theory-based interventions for smoking and weight loss. Health Educ Res. 2002;17:522–530. doi: 10.1093/her/17.5.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carver CS, Scheier M. Principles of self-regulation: action and emotion. In: Higgins ET, Sorrentino R, editors. Handbook of motivation and cognition: foundations of social behavior. New York: Guilford; 1990. pp. 3–52. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins ET. Beyond pleasure and pain. Am Psychol. 1997;52:1280–1300. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.52.12.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fabricatore AN, Wadden TA, Womble LG, et al. The role of patients’ expectations and goals in the behavioral and pharmacological treatment of obesity. Int J Obes. 2007;31:1739–1745. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Provencher V, Bégin C, Gagnon-Girouard MP, et al. Defined weight expectations in overweight women: anthropometrical, psychological and eating behavioral correlates. Int J Obes. 2007;31:1731–1738. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linde JA, Jeffery RW, Levy RL, et al. Weight loss goals and treatment outcomes among overweight men and women enrolled in a weight loss trial. Int J Obes. 2005;29:1002–1005. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White MA, Masheb RM, Rothschild BS, et al. Do patients’ unrealistic weight goals have prognostic significance for bariatric surgery? Obes Surg. 2007;17:74–81. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byrne S, Cooper Z, Fairburn C. Weight maintenance and relapse in obesity: a qualitative study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:955–962. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorin AA, Pinto AM, Tate DF, et al. Failure to meet weight loss expectations does not impact maintenance in successful weight losers. Obesity. 2007;15:3086–3090. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wee C, Jones D, Davis R, et al. Understanding patients’ value of weight loss and expectations for bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2006;16:496–500. doi: 10.1381/096089206776327260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Molinari E, et al. Weight loss expectations in obese patients and treatment attrition: an observational multicenter study. Obes Res. 2005;13:1961–1969. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belachew M, Legrand M, Defechereux T, et al. Laparoscopic adjustable silicone gastric banding in the treatment of morbid obesity. A preliminary report. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:1354–1356. doi: 10.1007/BF00188302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsen JK, Geenen R, van Ramshorst B, et al. Psychosocial functioning before and after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: a cross-sectional study. Obes Surg. 2003;13:629–636. doi: 10.1381/096089203322190871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deitel M, Gawdat K, Melissas J. Reporting weight loss 2007. Obes Surg. 2007;17:565–568. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9116-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 4. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janz N, Becker M. The Health Belief Model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11:1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psychol. 1992;47:1102–1114. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bandura AT. Social foundation of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Locke EA, Latham GP. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation. A 35-year odyssey. Am Psychol. 2002;57:705–717. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.57.9.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elfhag K, Rössner S. Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain. Obes Rev. 2005;6:67–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zijlstra H, Larsen JK, van Ramshorst B, et al. The association between weight loss and self-regulation cognitions before and after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding for obesity: A longitudinal study. Surgery. 2006;139:334–339. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larsen JK, Geenen R, Van Ramshorst B, et al. Binge eating and exercise behavior after surgery for severe obesity: A structural equation model. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39:369–375. doi: 10.1002/eat.20249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]