Abstract

There is a close relationship between serotonergic (5-HT) activity and anxiety. ErbB4, a receptor tyrosine kinase, is expressed in 5-HT neurons. However, whether ErbB4 regulates 5-HT neuronal function and anxiety-related behaviors is unclear. Here, using transgenic and viral approaches, we show that mice with ErbB4 deficiency in 5-HT neurons exhibit heightened anxiety-like behavior and impaired fear extinction, possibly due to an increased excitability of 5-HT neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN). Notably, the chemogenetic inhibition of 5-HT neurons in the DRN of ErbB4 mutant mice rescues anxiety-like behaviors. Altogether, our results unravel a previously unknown role of ErbB4 signaling in the regulation of DRN 5-HT neuronal function and anxiety-like behaviors, providing novel insights into the treatment of anxiety disorders.

Subject terms: Emotion, Anxiety

Introduction

Anxiety is a response to potentially threatening situations, and anxiety disorders area group of mental disorders characterized by excessive and persistent anxiety and fear [1–4]. An increasing number of people are being diagnosed with anxiety disorders [5], and current medical treatments for anxiety disorders are not satisfying; it is thus of great importance to obtain a better understanding of the pathogenesis of this disease to aid the development of new and more effective treatments.

Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) is a major neurotransmitter that is widely distributed throughout the entire brain [6, 7]. 5-HT neurons are predominately located in the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) and project widely throughout the brain [6]. Studies have shown that 5-HT neurons are involved in the regulation of anxiety behaviors [7–10]. For example, acute but not chronic chemogenetic activation of 5-HT neurons induces anxiogenic behavioral responses [11]. Meanwhile, acute chemogenetic stimulation of 5-HT neuronal activity in the wild-type mice is anxiogenic, whereas inhibition has no effect [12]. Moreover, chemogenetic activation of central amygdala (CeA)-projecting DRN serotonin neurons promotes anxiety-like behavior [13]. Optogenetic-specific stimulation of DRN 5-HT neuronal terminals in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) elicits anxiogenic behaviors and promotes fear [9], but optogenetic activation of DRN 5-HTneuronal cell body has no effect on anxiety [14–16]. This inconsistency may be caused by the heterogeneity of 5-HT neurons in terms of their connectivity and functions [13, 17]. Moreover, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the first-line interventions for anxiety disorders [18]. However, the molecular mechanisms by which 5-HT neurons regulate anxiety are largely unknown.

ErbB4 is a receptor tyrosine kinase, and the ErbB4-encoding gene is a well-known susceptibility gene for schizophrenia [19]. Studies have shown that ErbB4 receptors are essential for neural development and functions, and most studies have focused on the roles of ErbB4 in GABAergic interneurons in cortical areas [19–21]. ErbB4 receptors are also expressed on 5-HT neurons in the DRN [22], however, little is known about their functions.

In this study, we investigated the consequences of ErbB4 knockdown in DRN 5-HT neurons on anxiety-like behaviors in mice. We found that the specific knockdown of ErbB4 in DRN 5-HT neurons induced anxiety-like behaviors by increasing the activity of 5-HT neurons. Our findings shed new light on the pathogenesis of anxiety disorders and suggest that targeting ErbB4 signaling in DRN 5-HT neurons might represent a novel treatment for anxiety disorders.

Materials And methods

Animals

Mice were housed under standard housing conditions (a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle) with food and water ad libitum. LoxP-flanked ErbB4 [23], Sert-Cre [24], and ErbB4 reporter [22] mice were described previously. To label all Sert-Cre cells, Sert-Cre and Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice were crossed with Ai14 reporter mice to drive the expression of the red fluorescent protein tdTomato. Three or four male mice were housed in a cage. Approximately 9- to 12-week-old male mice were used to perform all behavior tests. Mice used in Fig. 1 in each assay were separate cohorts, and mice were the same group in Figs. 2e–i, 3c–g, or 5c–f, respectively. Each behavioral paradigm was separated at least 1 week. All mice were handled for 3 days before behavioral assays. All of the experiments were conducted in accordance with the Regulations for the Administration of Affairs Concerning Experimental Animals (China) and were approved by the Southern Medical University Animal Ethics Committee.

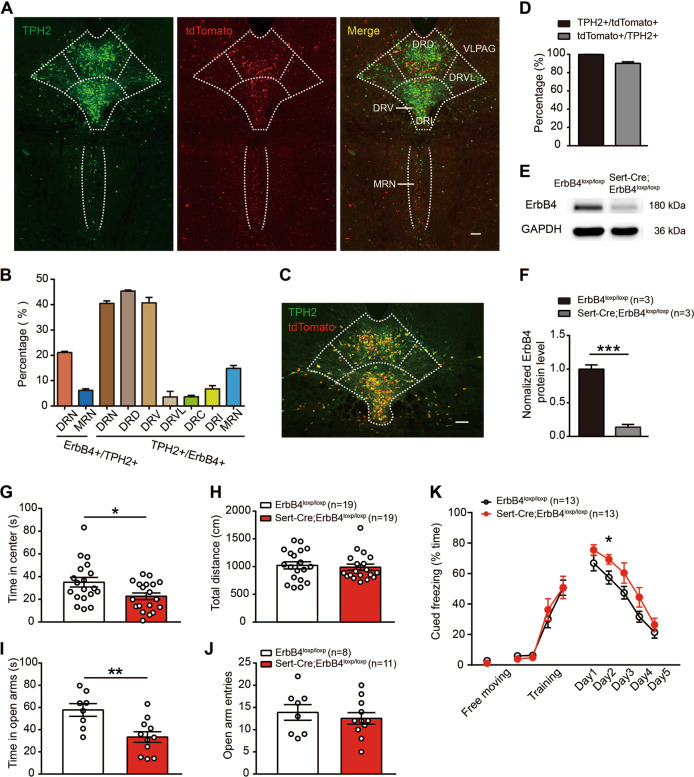

Fig. 1. Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice show anxiety-like behaviors and fear extinction impairment.

a Representative confocal images of tdTomato distribution (red) in the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) and the median raphe nucleus (MRN). Slices were obtained from ErbB4-reporter mice and stained with an antibody against tryptophan hydroxylase 2 (TPH2) (green), a marker of 5-HT neurons. Scale bar, 200 µM. b The colocalization of TPH2 and Cre/tdTomato in the DRN and MRN, and the distribution of TPH2 + /ErbB4 + cells within the different DRN subnuclei. DRD dorsal DRN, DRV ventral DRN, DRVL ventrolateral DRN, DRC caudal DRN, DRI interfascicular DRN. Three mice were studied, and five slices were chosen from each mouse. c A representative confocal image showing tdTomato distribution (red) in the DRN of Sert-Cre;Ai14 mouse. Slices were stained with a TPH2 antibody (green). Scale bar, 200 µM. d Four mice were studied, and five slices were chosen from each mouse. e, f The protein levels of ErbB4 were decreased in the DRN of Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, t(4) = 11.53, p = 0.0003. g, h The time spent in the center in the OFT was decreased in Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice compared to wild-type controls. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, t(36) = 2.417, p = 0.021. i, j The time spent in the open arms in the EPM test was decreased in Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, t(17) = 3.263, p = 0.005. k Fear extinction but not fear training was impaired in Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice. One-way repeated measures, Mauchly’s test of sphericity, W = 0.546, p = 0.140; tests of between-subjects effects, group, F(1, 1) = 5.702, p = 0.025. Day 2, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, t(24) = –2.275, p = 0.032. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. The numbers of mice are shown in parentheses.

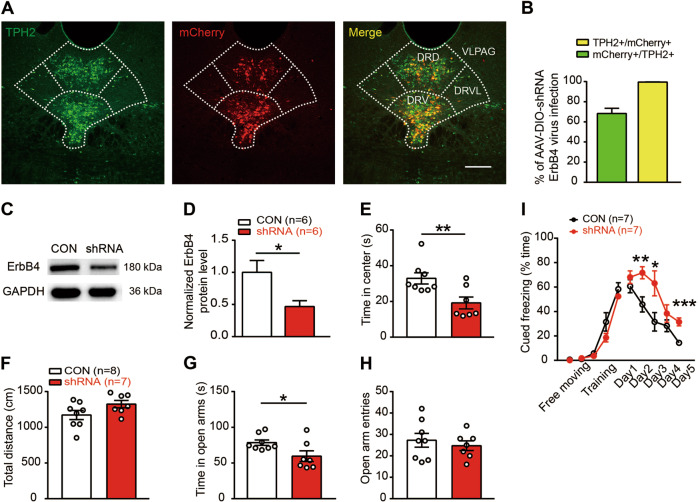

Fig. 2. Specific interference of ErbB4 expression in DRN 5-HT neurons is sufficient to produce anxiety-like behaviors and fear extinction impairment.

a Representative confocal images of ErbB4-shRNA-mCherry distribution (red) in the DRN of Sert-Cre mice. Slices were stained with a TPH2 antibody (green). Scale bar, 200 µM. b The colocalization of TPH2 and mCherry. Five mice were studied, and five slices were chosen from each mouse. c, d The protein levels of ErbB4 were decreased in the DRN of Sert-Cre mice injected with an AAV expressing ErbB4-shRNA. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, t(10) = 2.586, p = 0.027. e, f The time spent in the center (e) and the total distance traveled (f) in the OFT. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, t(13) = 3.017, p = 0.001. g, h The time spent in the open arms (g) and the number of open arm entries (h) in the EPM test. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, t(13) = 2.343, p = 0.036. i Fear extinction was impaired in Sert-Cre mice injected with an AAV expressing ErbB4 shRNA. One-way repeated measures, Mauchly’s test of sphericity, W = 0.217, p = 0.072; tests of between-subjects effects, group, F(1, 1) = 16.356, p = 0.002. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, t(12) = −3.284, p = 0.007 (day 2); t(12) = −2.480, p = 0.029 (day 3); t(12) = −1.178, p = 0.261 (day 4); t(12) = −4.707, p = 0.001 (day 5). CON, DIO-scramble-shRNA-mCherry; shRNA, DIO-ErbB4-shRNA-mCherry. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. The numbers of mice are shown in parentheses.

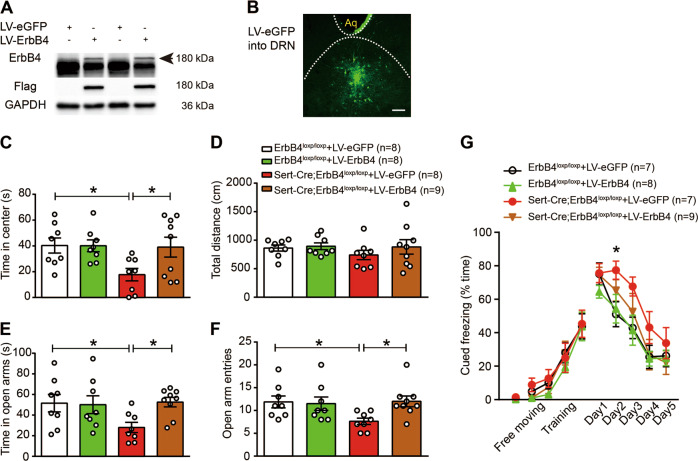

Fig. 3. ErbB4 overexpression in the DRN rescues the behavioral phenotypes of Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice.

a Western blotting showing that LV-ErbB4 was successfully expressed in HEK293T cells. The large band below ErbB4 was a nonspecific band, which might represent an unknown protein of HEK293 cells, as ErbB-4 antibody we used was a polyclonal antibody. b A representative confocal image showing LV-eGFP expression (green) in the DRN. Scale bar, 200 µM. c, d The time spent in the center (c) and the total distance traveled (d) in the OFT. c Two-way ANOVA, F(3, 29) = 3.320, p = 0.034; ErbB4loxp/loxp + LV-eGFP vs. Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + LV-eGFP, p = 0.014; Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + LV-eGFP vs. Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + LV-ErbB4, p = 0.017. e, f The time spent in the open arms (e) and the number of open arm entries (f) in the EPM test. e, one-way ANOVA, F(3, 29) = 2.928, p = 0.050; ErbB4loxp/loxp + LV-eGFP vs. Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + LV-eGFP, p = 0.023; Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + LV-eGFP vs. Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + LV-ErbB4, p = 0.015. f One-way ANOVA, F(3, 29) = 3.029, p = 0.045, ErbB4loxp/loxp + LV-eGFP vs. Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + LV-eGFP, p = 0.019; Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + LV-eGFP vs. Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + LV-ErbB4, p = 0.014. g Fear conditioning test. One-way repeated measures, Mauchly’s test of sphericity, W = 0.718, p = 0.493; tests of between-subjects effects, group, F(1, 3) = 4.071, p = 0.017. Day 2, one-way ANOVA, ErbB4loxp/loxp + LV-eGFP vs. Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + LV-eGFP, p = 0.020. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05. The numbers of mice are shown in parentheses.

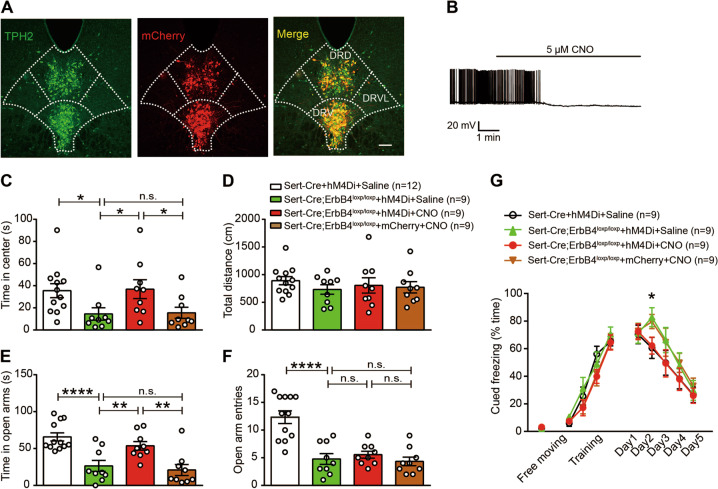

Fig. 5. Chemogenetic inhibition of 5-HT neurons in the DRN of Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice can rescue heightened anxiety-like behaviors and impaired fear extinction.

a A representative confocal image showing DIO-hM4Di-mCherry distribution (red) in the DRN. Slices were stained with a TPH2 antibody (green). Scale bar, 100 µM. b The firing of 5-HT neurons induced by current injection was inhibited by CNO. c, d The time spent in the center (c) and the total distance traveled (d) in the OFT. The time spent in the center, Sert-Cre + hM4Di + saline vs. Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + hM4Di + saline, p = 0.036; Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + hM4Di + saline vs. Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + hM4Di + CNO, p = 0.028; Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + hM4Di + CNO vs. Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + mCherry + CNO, p = 0.036. e, f The time spent in the open arms (e) and the number of open arm entries (f) in the EPM test. The time spent in the open arms, Sert-Cre + hM4Di + saline vs. Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + hM4Di + saline, p < 0.0001; Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + hM4Di + saline vs. Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + hM4Di + CNO, p = 0.007; Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + hM4Di + CNO vs. Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + mCherry + CNO, p = 0.002. The number of open arm entries, Sert-Cre + hM4Di + saline vs. Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + hM4Di + saline, p < 0.0001. g Fear conditioning test. CNO or saline was administered 30 min before fear extinction. One-way repeated measures, Mauchly’s test of sphericity, W = 0.673, p = 0.212; tests of between-subjects effects, group, F(1, 3) = 5.959, p = 0.002. Day 2, one-way ANOVA, Sert-Cre + hM4Di + saline vs. Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + hM4Di + saline, p = 0.022; Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + hM4Di + saline vs. Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp + hM4Di + CNO, p = 0.033. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA (c–f), *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. n.s., not significant. The numbers of mice are shown in parentheses.

Tamoxifen injection

To induce Rosa::LSL-tdTomato fluorescent protein expression in ErbB4-positive cells, adult male ErbB4 reporter mice aged about 8 weeks were administered 180 mg/kg tamoxifen (T5648, Sigma, USA) for 5 consecutive days (i.p.). A week later, the mice were sacrificed, and their brains were harvested.

Chemogenetic manipulations

The designer drug clozapine-N-oxide (CNO, 5 mg/kg, i.p.; Sigma) was administered 30 min before behavioral tests. In Fig. 5, mice received an injection of CNO 30 min before fear extinction for consecutive 5 days.

Cell culture and virus infection

HEK293T cells were grown at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and 95% air. A lentivirus containing ErbB4-Flag (LV-ErbB4-Flag) was constructed and packed by BrainVTA (Wuhan, China). Cultured HEK293T cells were transfected with 107 ml of the virus. According to the instructions, the virus was added to the cells at an optimal ratio (1:500), and after 8–12 h, the solution was changed, and the infection rate was observed after 72–96 h. Then, the cells were harvested for western blot analysis.

Behavioral assays

Open-field test

The open-field apparatus consisted of a rectangular chamber (40 × 40 × 30 cm) that was made of gray polyvinyl chloride. The mice were gently placed in the center and left to explore the area for 5 min. The box was cleaned with a solution of 75% ethanol in water between sessions. A digitized image of the path taken by each mouse was recorded, and the total distance traveled and time spent in the center both were analyzed using VERSADAT software.

Elevated plus-maze test

The elevated plus-maze test consisted of two opposing open arms (30 × 5 × 0.5 cm) and two opposing enclosed arms (30 × 5 × 15 cm) that were connected by a central platform (5 × 5 cm), forming the shape of a plus sign. All of the measurements were taken in a silent and dimly lit experimental room, to which the mice were acclimatized for at least 30 min before testing. The time spent in and the number of entries into the open arms were recorded over a 5-min test period. The maze was cleaned with a solution of 75% ethanol in water between sessions. All data were analyzed post hoc using EthoVision XT 11.5 software.

Fear conditioning

For cued fear conditioning experiments, mice were placed in a chamber with numerous parallel stainless-steel grid bars connected to a shock generator along the floor (the FreezeFrame System, Coulbourn Instruments, Woonsocket, USA). Cued freezing (% time) was calculated by an automated freezing analysis software (FreezeFrame System). The control mouse whose freezing time (%) was lower than 10% in day 1 was excluded. For conditioning (day 1), 2 min after being placed in the chamber (this period was used for the free-moving freezing), the mice were exposed to 30-s tones (2.8 kHz, 80 dB) terminated with a foot shock at 60 s inter-trail intervals. Mice were presented with four tone-shock pairings (0.75 mA, 1-s shocks). The chamber was cleaned with 75% ethanol at the end of each trial. The following days (days 1–5, fear extinction), the mice were placed in a different context (floor and walls were changed). First, the mice were exposed to a short 30 s baseline to measure fear retrieval (tone 1 on days 1–5). Subsequently, the mice were exposed to 10 tones (30 s) (tones 2–11 on days 1–5) with a 30 s inter-trial interval to induce fear extinction.

Stereotaxic injection

For virus injection into the DRN, adult male mice were anesthetized with 1% pentobarbital (i.p. injection) and mounted onto a mouse stereotaxic frame. The skin was cut, and a small craniotomy was made 5.00 mm posterior to bregma along the midline. Using a microsyringe pump (Nanoliter 2000 Injector, WPI), AAV virus (500 nl) was slowly injected (100 nl per min) into the DRN through a glass pipette at a 15° angle from caudal to rostral (depth = 3.15 mm). The glass pipette was left in place for ten additional minutes and then slowly withdrawn. AAV vectors carrying the DIO-ErbB4-shRNA-mCherry, DIO-scramble-shRNA-mCherry, DIO-hM4Di-mCherry, and DIO-mCherry constructs were packaged into AAV2/9 serotype viral vectors at a titer of 3–6 × 1013 viral particles per ml. For ErbB4 overexpression experiments, the mice were injected into the DRN with 0.5 µl of LV-ErbB4-Flag virus. At the end of the experiments, the mice were perfused for further immunohistology, and only mice that exhibited virus expression confined to the target region were used.

Western blot analysis

Tissue homogenates isolated from the DRN or infected HEK293T cells were prepared in cold RIPA Lysis Buffer (P0013B, Beyotime, China). Bound proteins were resolved on sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for 3 h at 320 mA. Then, these membranes were incubated in TBS buffer containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 5% milk for 2 h at room temperature. Then, the membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4 °C. After washing, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies in TBST for 2 h at room temperature. Chemiluminescence Apparatus (Bio-Rad) was used to detect the desired signals. The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit polyclonal anti-ErbB4 (ErbB-4 (C-18): sc-283; 1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH (1:5000, Proteintech, China), and mouse monoclonal anti-Flag (1:1000, Proteintech).

Immunofluorescence

The mice were anesthetized with 1% pentobarbital sodium and transcardially perfused with saline, followed by 4% formaldehyde. After cryoprotection in 30% sucrose for 2 days, 40 μm thick coronal slices were cut on a freezing microtome (CM-1950, Leica, Germany). The slices were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 1% Triton-100 and subsequently incubated with an anti-TPH2 primary antibody (1:400, Millipore, USA) overnight at 4 °C. After washing with 0.01 M PBS, the sections were incubated with an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (1:500; A11034; Invitrogen, USA) at room temperature for 2 h. The slices were cover slipped with Vectashield Mounting Medium with DAPI (H-1200, Vector, USA). Fluorescence images were captured using a fluorescence microscope (A1R, Nikon, Japan).

Slice preparation

Slices were prepared as described previously [25]. Mice (6–8-weeks-old, male) were anesthetized with ether, and the brains were quickly removed and chilled in iced-cold modified artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mM) 250 glycerol, 2 KCl, 10 MgSO4, 0.2 CaCl2, 1.3 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 10 glucose. Horizontal slices (300 μm) were then cut on a vibrating microtome (VT1000S; Leica). The slices were maintained at room temperature for an additional 1 h before recording. All solutions were saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2 (vol/vol).

Electrophysiological recording

Slices were moved to a recording chamber, and the recording solution (ACSF) was maintained at a temperature of 32–34 °C. Fluorescent neurons were visually identified under an upright microscope (Nikon, Eclipse FN1) equipped with an infrared-sensitive charge-coupled device camera. Electrophysiological recordings were performed in cell-attached mode for to record spontaneous firing and in whole-cell mode to detect intrinsic membrane properties with a Multi Clamp 700B Amplifier equipped with Digidata 1440 A analog-to-digital converter. For spontaneous firing recordings, microelectrodes (3–5 MΩ) were filled with a solution containing 130 mM potassium gluconate, 20 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES buffer, 2 mM MgCl·6H2O, 4 mM Mg-ATP, 0.3 mM Na-GTP, and 10 mM EGTA. The pH was adjusted to 7.25 with 10 M KOH. The intrinsic excitability of the neurons was assessed by measuring the firing rate in response to a series of depolarizing pulses in the presence of 20 μM CNQX, 100 μM AP5, and 20 μM BMI. Spontaneous firing was recorded for at least 2 min for each neuron. Cell was injected a depolarized current to induce spike generation. For intrinsic membrane properties recordings, cells were held at −70 mV. The minimal current injection sufficient for spike generation from −70 mV was defined as the rheobase. Action potential threshold was measured as the voltage at which the slope = 20 V/s. The input resistance was calculated by injecting a 20 pA hyperpolarized current to induce voltage changes. The effects of CNO were determined in current clamp mode. After a 2 min stable baseline, CNO (5 μM) was bath applied for 10 min. All analyses were performed using Clampfit 10.2 (Axon Instruments/Molecular Devices) or Minianalysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS 13.0. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for comparisons of two individual groups. One-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for comparisons of correlated samples. One-way or two-way ANOVA followed by post hoc test were used for comparisons of independent groups. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Results

To determine the distribution of ErbB4 on 5-HT neurons in the DRN, we crossed ErbB4::CreERT2 mice, which allows the fused Cre-ER protein to translocate into the nucleus following tamoxifen treatment, with Rosa::LSL-tdTomato mice, which harbor a loxp-flanked tdTomato red fluorescent protein, to generate ErbB4::CreERT2;Rosa::LSL-tdTomato mice, in which ErbB4-expressing neurons are labeled with tdTomato [22]. We then performed immunostaining for the 5-HT neuronal marker TPH2. We found that 40.47 ± 1.00% of DRN ErbB4-positive cells were colocalized with TPH2, and 21.09 ± 0.48% of DRN 5-HT neurons expressed ErbB4 (Fig. 1a, b), while 14.85 ± 1.18% of MRN (median raphe nucleus) ErbB4-positive cells were colocalized with TPH2, and 6.19 ± 0.63% of MRN 5-HT neurons were positive for ErbB4 (Fig. 1a, b), which are consistent with a previous study [22]. Notably, the ErbB4-positive cells of 5-HT neurons were mainly distributed in the dorsal (about 53%) and ventral (about 44.9%) parts of the DRN (Fig. 1b). To investigate the role of ErbB4 in 5-HT neurons, we generated Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice by crossing Sert-Cre mice with ErbB4loxp/loxp mice. First, to examine the specificity and efficiency of Cre expression in 5-HT neurons, we crossed Sert-Cre mice with Ai14 reporter mice to generate Sert-Cre;Ai14 mice. Immunostaining analysis showed that ~ 99.8% Cre/tdTomato + neurons were colocalized with TPH2 and 90.1% TPH2 + neurons expressed Cre/tdTomato in the Sert-Cre;Ai14 mice (Fig. 1c, d). In the DRN of Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice, there was a remarkable reduction in ErbB4 expression (Fig. 1e, f; 1f, t(4) = 11.53, p = 0.0003). To examine anxiety-related behaviors, we performed the open-field test (OFT), the elevated plus-maze (EPM) test and the fear conditioning (FC) test. In the OFT, Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice showed normal motor activity (Fig. 1h), but spent less time in the center than controls (Fig. 1g, t(36) = 2.417, p = 0.021). In the EPM test, the time spent in the open arms by Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice was dramatically decreased compared with that spent by control mice (Fig. 1i, j; 1i, t(17) = 3.263, p = 0.005). In the FC test, Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice showed normal fear learning but impaired extinction (Fig. 1k, F(1, 1) = 5.702, p = 0.025). These data indicate that the specific deletion of ErbB4 in 5-HT neurons induces anxiety-like behaviors.

To test whether the knockdown of ErbB4 in 5-HT neurons in the DRN is sufficient to induce anxiety-like behaviors and fear extinction impairment, we injected an adeno-associated virus (AAV2/9) expressing ErbB4-shRNA and mCherry in a Cre-dependent manner into the DRN of Sert-Cre mice. ErbB4-shRNA-mCherry was expressed specifically in DRN 5-HT neurons, with 99.56% of mCherry + neurons being TPH2 + (Fig. 2a, b). By using immunoblotting, we confirmed a high efficiency of ErbB4 knockdown in the DRN of Sert-Cre mice after AAV2/9-DIO-ErbB4-shRNA injection (Fig. 2c, d; 2d, t(10) = 2.586, p = 0.027). Behavioral tests were performed 3 weeks after viral injection. We observed an anxiogenic effect, as mice with viral-mediated region-specific knockdown of ErbB4 in the DRN exhibited decreased time spent in the center in the OFT (Fig. 2e, f; 2e, t(13) = 3.017, p = 0.001) and time spent in the open arms in the EPM test (Fig. 2g, h; 2g, t(13) = 2.343, p = 0.036). In the FC test, DRN ErbB4 knockdown impaired fear extinction but not fear learning (Fig. 2i, F(1, 1) = 16.356, p = 0.002). These results show that the specific knockdown of ErbB4 in DRN 5-HT neurons is sufficient to induce anxiety-like behaviors, which is similar to those observed in Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice.

As the specific knockdown ErbB4 in DRN 5-HT neurons led to anxiety-like behaviors and impaired fear extinction comparable to what was observed in Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice, we tested whether ErbB4 expression in DRN 5-HT neurons is required for anxiety-like/fear behaviors. To this end, we generated a lentiviral ErbB4 expression vector with Flag tag (LV-ErbB4-Flag) [26]. The infection of HEK293T cells, which do not express ErbB receptors [27], with LV-ErbB4-Flag led to a dramatic increase in ErbB4 protein levels, assessed by western blotting (Fig. 3a). Then, LV-ErbB4-Flag or LV-eGFP was injected into the DRN of Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice and ErbB4loxp/loxp mice (as a control). The expression of the LV-eGFP virus in the DRN was confirmed, as shown in Fig. 3b. Anxiety-like/fear behaviors were tested 3 weeks after viral injection. We found that ErbB4 overexpression in the DRN of Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice increased the time spent in the center in the OFT (Fig. 3c, d; 3c, F(3, 29) = 3.320, p = 0.034) and the time spent in and the number of entries into the open arms in the EPM test (Fig. 3e, f; 3e, F(3, 29) = 2.928, p = 0.05). Furthermore, LV-mediated ErbB4 overexpression rescued impaired fear extinction (Fig. 3g, F(1, 3) = 4.071, p = 0.017). These results further support that ErbB4 in DRN 5-HT neurons plays an important role in anxiety-like behaviors.

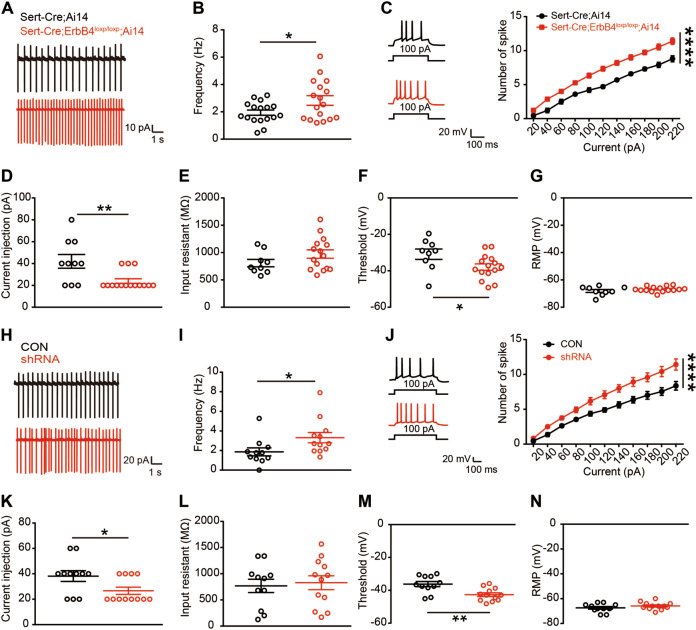

To study the effects of ErbB4 deficiency on 5-HT neuronal electrophysiology, Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice were further crossed with Ai14 mice to specifically label Cre-positive neurons with the red fluorescent protein tdTomato. We recorded the spontaneous activity of DRN 5-HT neurons in acute brain slices from Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp;Ai14 mice and found that the spontaneous firing frequency of DRN 5-HT neurons was dramatically increased (Fig. 4a, b; 4b, t(32) = 2.218, p = 0.034). Consistently, the evoked firing frequency in response to depolarizing current injection from 20 to 220 pA was also significantly increased (Fig. 4c, F(1, 251) = 204.1, p < 0.0001), and the minimal current needed to induce the first action potential (rheobase current) was decreased (Fig. 4d, t(21) = 3.145, p = 0.005). While the input resistance and resting membrane potential were unaltered (Fig. 4e, g), the action potential threshold of DRN-5-HT neurons was decreased in the absence of ErbB4 (Fig. 4f, t(21) = 2.251, p = 0.035). To study the effects of ErbB4-shRNA on 5-HT neuronal electrophysiology, mCherry + neurons in the DRN of CON and shRNA mice were recorded 3 weeks after viral injection (Fig. 4h–n). We recorded the spontaneous activity of DRN 5-HT neurons in acute brain slices and found that the spontaneous firing frequency of DRN 5-HT neurons was increased in the shRNA mice (Fig. 4h, i, t(21) = 2.148, p = 0.043). Consistently, the evoked firing frequency in response to depolarizing current injection from 20 to 220 pA was also significantly increased (Fig. 4j, F(1, 231) = 89.26, p < 0.0001), and the minimal current needed to induce the first action potential was decreased (Fig. 4k, t(21) = 2.296, p = 0.032). While the input resistance and resting membrane potential were unchanged (Fig. 4l, n), the action potential threshold of DRN 5-HT neurons was decreased in the absence of ErbB4 (Fig. 4m, t(21) = 3.352, p = 0.003). These data indicate that the knockdown of ErbB4 leads to a significant increase in the excitability of 5-HT neurons.

Fig. 4. Increased excitability of DRN-5-HT neurons from Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp and ErbB4 knockdown mice.

a Representative spontaneous firing traces of DRN 5-HT neurons from Sert-Cre;Ai14 and Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp;Ai14 mice. b The quantification of the spontaneous firing rate of DRN 5-HT neurons. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, t(32) = 2.218, p = 0.034, n = 17 cells from four mice from each group. c Left, representative traces of action potentials evoked by injecting a depolarizing current of 100 pA. Right, the number of action potentials against the injected currents. Two-way ANOVA, F(1, 251) = 204.1, p < 0.0001. d Rheobase currents. t(21) = 3.145, p = 0.005. e Input resistance. f Action potential threshold. t(21) = 2.251, p = 0.035. g Resting membrane potential (RMP). Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (d–g), n = 9 cells from four mice (Sert-Cre;Ai14), n = 14 cells from four mice (Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp;Ai14). h Representative spontaneous firing traces of DRN 5-HT neurons from CON and shRNA mice. i The quantification of the spontaneous firing rate of DRN 5-HT neurons. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, t(21) = 2.148, p = 0.043, n = 11 cells from four mice (CON), n = 12 cells from four mice (shRNA). j Left, representative traces of action potentials evoked by injecting a depolarizing current of 100 pA. Right, the number of action potentials against the injected currents. Two-way ANOVA, F(1, 231) = 89.26, p < 0.0001. k Rheobase currents. t(21) = 2.296, p = 0.032. l Input resistance. m Action potential threshold. t(21) = 3.352, p = 0.003. n RMP. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (k–n), n = 11 cells from four mice (CON), n = 12 cells from four mice (shRNA). The data are presented as the mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

To test whether an increase in DRN 5-HT neuronal activity underlies the anxiety-like behaviors of Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice, we applied DREADD (designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs) technology to inhibit 5-HT neurons by using an AAV2 vector expressing the engineered Gi-coupled hM4D receptor [28, 29] (Fig. 5a). Whole-cell recordings of 5-HT neurons from acutely isolated DRN brain slices confirmed that clozapine-N-oxide (CNO, 5 µM), an agonist of the hM4D receptor, suppressed the firing of hM4Di-expressing 5-HT neurons (Fig. 5b). Three weeks after viral injection, we then intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected CNO (5 mg per kilogram of body weight) into Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice and found that CNO treatment produced anxiolytic effects, as the time spent in the center in the OFT (Fig. 5c, d; 5c, F(3, 35) = 3.458, p = 0.027) and in the open arms in the EPM test (Fig. 5e, f; 5e, F(3, 35) = 11.46, p < 0.0001; 5f, F(3, 35) = 17.56, p < 0.0001) was normalized by CNO application. Furthermore, CNO treatment rescued impaired fear extinction (Fig. 5g, F(1, 3) = 5.959, p = 0.002).

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated a crucial role for ErbB4 in 5-HT neurons in the regulation of anxiety-related behaviors for the first time. Our major findings are as follows. First, Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice show increased anxiety-like behaviors and impaired fear extinction. Second, the specific knockdown of ErbB4 in 5-HT neurons in the DRN induces similar behavior deficits. Third, ErbB4 overexpression in the DRN can normalize the behavioral deficits of Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice. Furthermore, ErbB4 deficiency in 5-HT neurons causes an increase in the excitability of 5-HT neurons, and the chemogenetic inhibition of 5-HT neurons in Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice normalizes anxiety-like behaviors.

While ErbB4 has been associated with anxiety, the phenotypes induced by the specific knockdown of ErbB4 in different neuronal types are inconsistent. For example, ErbB4 knock-out mice exhibit reduced anxiety-like behaviors in the EPM test and deficits in cued fear conditioning [20]. ErbB4 deficiency in somatostatin neurons in the CeA induces heightened anxiety [30], and ErbB4 deletion in noradrenergic neurons (NE) in the locus coeruleus (LC) reduces anxiety [31]. Our previous works showed that ErbB4 knockdown in the amygdala increases anxiety-like behaviors through GABAergic neurotransmission [25], and ErbB4 ablation specifically in PV neurons in the prelimbic cortex impairs fear expression [26]. In this study, we further showed that ErbB4 knockdown in 5-HT neurons in the DRN can elicit increased anxiety-like behaviors and impair fear extinction. Taken together, these studies demonstrate that ErbB4 in different neuronal subtypes may exert different functions on anxiety.

DRN is supposed to be composed of five subnuclei that differ anatomically and functionally [32, 33]. Past studies have reported that dorsalmedial, ventromeidal and caudal DRN are closely related to anxiety-like behavior, while the lateral wings are more strongly associated with panic and fear [34–38]. In this study, we found that ErbB4-positive 5-HT neurons are primarily located within the dorsal and ventral regions of the DRN. Future studies are required to specifically interfere ErbB4 in different DRN subnuclei to determine their roles on anxiety and fear.

The effects on extinction are modest in Sert-Cre/ErbB4loxp/loxp mice in our study. We thought it might be caused by the compensation during development [39], because the effect of ErbB4-shRNA virus experiment was very strong. Another possibility is that deletion of ErbB4 may affect multiple 5-HT brain areas with different role in modulation of extinction and thereby generate modest change in extinction.

Previous studies have implicated a close relationship between NRG1-ErbB4 signaling and neuronal excitability [31, 40]. For example, NR2B (a NMDAR subunit) has been identified as a downstream target of the NRG1-ErbB4 signaling in regulating neuronal excitability in the human and mouse brain [31, 41–43]. NR2B overexpression alters NMDAR activity, which might contribute to the increased spontaneous firing of locus coeruleus noradrenergic neurons in the absence of ErbB4 [31]. A study found that NRG1 application dramatically attenuates ErbB4-expressing interneuron excitability by decreasing voltage-gated sodium channel activity [40]. We reveal that the excitability of DRN 5-HT neurons was increased in the absence of functional ErbB4 in these neurons in our study, and this might be caused by abnormal functions of NR2B or voltage-gated sodium channel. However, this assumption requires further investigation. Optogenetic or chemogenetic activation of DRN 5-HT neurons could induce anxiety-like behaviors [9, 11–13], which was in consistent with the results of ErbB4 knockdown in DRN 5-HT neurons. In support of this conclusion, we found that chemogenetic inhibition of 5-HT neuronal activity in Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice normalized anxiety-like behaviors.

Serotonin is implicated in the pathophysiology of many psychiatric disorders, such as depressive and anxiety disorders [6, 44, 45]. Although it has been reported that the serotonin system is closely associated with anxiety since early in the twentieth century [10], the role played by 5-HT neurons in the regulation of anxiety is controversial. Pet-1, an ETS domain transcription factor, is important for controlling 5-HT neuron phenotype, and Pet-1 knock-out mice showed decreased anxiety behaviors [46, 47]; However, other studies have shown the opposite effects [48] or no effects [8]. Such differences may be caused by different experimental conditions. In addition, mice with a deficit in TPH2 exhibit decreased anxiety [49], while lacking the 5-HT transporter display increased anxiety behaviors [50]. Furthermore, many 5-HT receptors, including 5-HT1AR, 5-HT1BRs, 5-HT2CR, 5-HT3R, and 5-HT4R, are related to anxiety [10, 51–54].

Here, we demonstrate a direct causal relationship between the serotonin system and anxiety-like behaviors. With the advent of new technologies, in particular optogenetic and chemogenetic techniques that allow the selective targeting of DRN 5-HT neurons, recent studies have made great progress in identifying the function of 5-HT neuronal activity. The acute inhibition of 5-HT neurons via CNO-triggered hM4Di restores behaviors in a developmental model of anxiety but has no effect on naïve mice [12]. Similarly, the direct optogenetic inhibition of 5-HT neurons in normal mice does not affect anxiety-related behaviors in mice [15]. Therefore, the acute inhibition of 5-HT neurons may induce anxiolytic behavioral effects only in the context of heightened anxiety. In accord with this notion, we found that the excitability of 5-HT neurons was increased in Sert-Cre;ErbB4loxp/loxp mice, and the inhibition of 5-HT neurons normalized anxiety-like behaviors. Since only a subset of 5-HT neurons express ErbB4, future studies to identify the downstream brain areas targeted by ErbB4-expressing 5-HT neurons in the DRN are warranted.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Minmin Luo (National Institute of Biological Sciences, China) for providing the Sert-Cre mice. We also thank Dr. Lin Mei (Case Western Reserve University, USA) for providing the ErbB4::CreERT2;Rosa::LSL-tdTomato mice.

Funding and disclosure

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31430032, 31830033, 81671356), the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (IRT_16R37), the Science and Technology Program of Guangdong (2018B030334001) and Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (201707020027). The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Sheng-Rong Zhang, Jian-Lin Wu

References

- 1.Craske MG, Stein MB. Anxiety. Lancet. 2016;388:3048–59. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cryan JF, Holmes A. The ascent of mouse: advances in modelling human depression and anxiety. Nat Rev Drug Disco. 2005;4:775–90. doi: 10.1038/nrd1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harro J. Animals, anxiety, and anxiety disorders: How to measure anxiety in rodents and why. Behav Brain Res. 2018;352:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graham BM, Milad MR. The study of fear extinction: implications for anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1255–65. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11040557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Disease GBD, Injury I. Prevalence C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;392:1789–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lesch KP, Waider J. Serotonin in the modulation of neural plasticity and networks: implications for neurodevelopmental disorders. Neuron. 2012;76:175–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okaty BW, Commons KG, Dymecki SM. Embracing diversity in the 5-HT neuronal system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2019;20:397–424. doi: 10.1038/s41583-019-0151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lerch-Haner JK, Frierson D, Crawford LK, Beck SG, Deneris ES. Serotonergic transcriptional programming determines maternal behavior and offspring survival. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1001–3. doi: 10.1038/nn.2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcinkiewcz CA, Mazzone CM, D’Agostino G, Halladay LR, Hardaway JA, DiBerto JF, et al. Serotonin engages an anxiety and fear-promoting circuit in the extended amygdala. Nature. 2016;537:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature19318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graeff FG, Guimaraes FS, De Andrade TG, Deakin JF. Role of 5-HT in stress, anxiety, and depression. Pharm Biochem Behav. 1996;54:129–41. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urban DJ, Zhu H, Marcinkiewcz CA, Michaelides M, Oshibuchi H, Rhea D, et al. Elucidation of the behavioral program and neuronal network encoded by dorsal raphe serotonergic neurons. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:1404–15. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teissier A, Chemiakine A, Inbar B, Bagchi S, Ray RS, Palmiter RD, et al. Activity of raphe serotonergic neurons controls emotional behaviors. Cell Rep. 2015;13:1965–76. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.10.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ren J, Friedmann D, Xiong J, Liu CD, Ferguson BR, Weerakkody T, et al. Anatomically defined and functionally distinct dorsal raphe serotonin sub-systems. Cell. 2018;175:472–87 e420. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohmura Y, Tanaka KF, Tsunematsu T, Yamanaka A, Yoshioka M. Optogenetic activation of serotonergic neurons enhances anxiety-like behaviour in mice. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17:1777–83. doi: 10.1017/S1461145714000637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishitani N, Nagayasu K, Asaoka N, Yamashiro M, Andoh C, Nagai Y, et al. Manipulation of dorsal raphe serotonergic neurons modulates active coping to inescapable stress and anxiety-related behaviors in mice and rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:721–32. doi: 10.1038/s41386-018-0254-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Correia PA, Lottern E, Banerjee D, Machado AS, Carey MR, Mainen ZF. Transient inhibition and long term facilitation of locomotion by phasic optogenetic activation of serotonin neurons. eLife. 14 February 2017. https://elifesciences.org/articles/20975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Muzerelle A, Scotto-Lomassese S, Bernard JF, Soiza-Reilly M, Gaspar P. Conditional anterograde tracing reveals distinct targeting of individual serotonin cell groups (B5–B9) to the forebrain and brainstem. Brain Struct Funct. 2014;221:535–61. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0924-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandelow B, Michaelis S, Wedekind D. Treatment of anxiety disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2017;19:93–106. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2017.19.2/bbandelow. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mei L, Nave KA. Neuregulin-ERBB signaling in the nervous system and neuropsychiatric diseases. Neuron. 2014;83:27–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shamir A, Kwon OB, Karavanova I, Vullhorst D, Leiva-Salcedo E, Janssen MJ, et al. The importance of the NRG-1/ErbB4 pathway for synaptic plasticity and behaviors associated with psychiatric disorders. J Neurosci. 2012;32:2988–97. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1899-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mei L, Xiong WC. Neuregulin 1 in neural development, synaptic plasticity and schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:437–52. doi: 10.1038/nrn2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bean JC, Lin TW, Sathyamurthy A, Liu F, Yin DM, Xiong WC, et al. Genetic labeling reveals novel cellular targets of schizophrenia susceptibility gene: distribution of GABA and non-GABA ErbB4-positive cells in adult mouse brain. J Neurosci. 2014;34:13549–66. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2021-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Rivello H, Taranda J, Said M, Cabeza-Meckert P, Vila-Petroff M, Scaglione J, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy in Erb-b4-deficient ventricular muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H1153–1160. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00048.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gong S, Doughty M, Harbaugh CR, Cummins A, Hatten ME, Heintz N, et al. Targeting Cre recombinase to specific neuron populations with bacterial artificial chromosome constructs. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9817–23. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2707-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bi LL, Sun XD, Zhang J, Lu YS, Chen YH, Wang J, et al. Amygdala NRG1-ErbB4 is critical for the modulation of anxiety-like behaviors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:974–86. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen YH, Lan YJ, Zhang SR, Li WP, Luo ZY, Lin S, et al. ErbB4 signaling in the prelimbic cortex regulates fear expression. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1168. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaushansky A, Gordus A, Budnik BA, Lane WS, Rush J, MacBeath G. System-wide investigation of ErbB4 reveals 19 sites of Tyr phosphorylation that are unusually selective in their recruitment properties. Chem Biol. 2008;15:808–17. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez JL, Bonaventura J, Lesniak W, Mathews WB, Sysa-Shah P, Rodriguez LA, et al. Chemogenetics revealed: DREADD occupancy and activation via converted clozapine. Science. 2017;357:503–7. doi: 10.1126/science.aan2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Armbruster BN, Li X, Pausch MH, Herlitze S, Roth BL. Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5163–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700293104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahrens S, Wu MV, Furlan A, Hwang GR, Paik R, Li H, et al. A central extended amygdala circuit that modulates anxiety. J Neurosci. 2018;38:5567–83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0705-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao SX, Zhang Y, Hu XY, Hong B, Sun P, He HY, et al. ErbB4 deletion in noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus induces mania-like behavior via elevated catecholamines. Elife. 2018;7:1–25. doi: 10.7554/eLife.39907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abrams JK, Johnson PL, Hollis JH, Lowry CA. Anatomic and functional topography of the dorsal raphe nucleus. Ann N. Y Acad Sci. 2004;1018:46–57. doi: 10.1196/annals.1296.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bach-Mizrachi H, Underwood MD, Kassir SA, Bakalian MJ, Sibille E, Tamir H, et al. Neuronal tryptophan hydroxylase mRNA expression in the human dorsal and median raphe nuclei: major depression and suicide. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:814–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson PL, Lightman SL, Lowry CA. A functional subset of serotonergic neurons in the rat ventrolateral periaqueductal gray implicated in the inhibition of sympathoexcitation and panic. Ann N. Y Acad Sci. 2004;1018:58–64. doi: 10.1196/annals.1296.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hiroi R, McDevitt RA, Neumaier JF. Estrogen selectively increases tryptophan hydroxylase-2 mRNA expression in distinct subregions of rat midbrain raphe nucleus: Association between gene expression and anxiety behavior in the open field. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:288–95. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hiroi R, Neumaier JF. Estrogen decreases 5-HT1B autoreceptor mRNA in selective subregion of rat dorsal raphe nucleus: inverse association between gene expression and anxiety behavior in the open field. Neuroscience. 2009;158:456–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matthiesen M, Spiacci A, Jr., Zangrossi H., Jr Effects of chemical stimulation of the lateral wings of the dorsal raphe nucleus on panic-like defensive behaviors and Fos protein expression in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2017;326:103–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lowry CA. Functional subsets of serotonergic neurones: implications for control of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. J Neuroendocrinol. 2002;14:911–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2002.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Narboux-Neme N, Pavone LM, Avallone L, Zhuang X, Gaspar P. Serotonin transporter transgenic (SERTcre) mouse line reveals developmental targets of serotonin specific reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:994–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Janssen MJ, Leiva-Salcedo E, Buonanno A. Neuregulin directly decreases voltage-gated sodium current in hippocampal ErbB4-expressing interneurons. J Neurosci. 2012;32:13889–95. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1420-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hahn CG, Wang HY, Cho DS, Talbot K, Gur RE, Berrettini WH, et al. Altered neuregulin 1-erbB4 signaling contributes to NMDA receptor hypofunction in schizophrenia. Nat Med. 2006;12:824–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pitcher GM, Kalia LV, Ng D, Goodfellow NM, Yee KT, Lambe EK, et al. Schizophrenia susceptibility pathway neuregulin 1-ErbB4 suppresses Src upregulation of NMDA receptors. Nat Med. 2011;17:470–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu JM, Li KX, Cao SX, Chen XJ, Shen CJ, Zhang Y, et al. Increased NRG1-ErbB4 signaling in human symptomatic epilepsy. Sci Rep. 2017;7:141. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00207-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luo M, Zhou J, Liu Z. Reward processing by the dorsal raphe nucleus: 5-HT and beyond. Learn Mem. 2015;22:452–60. doi: 10.1101/lm.037317.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pawluski JL, Li M, Lonstein JS. Serotonin and motherhood: From molecules to mood. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2019;53:100742. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kiyasova V, Fernandez SP, Laine J, Stankovski L, Muzerelle A, Doly S, et al. A genetically defined morphologically and functionally unique subset of 5-HT neurons in the mouse raphe nuclei. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2756–68. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4080-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schaefer TL, Vorhees CV, Williams MT. Mouse plasmacytoma-expressed transcript 1 knock out induced 5-HT disruption results in a lack of cognitive deficits and an anxiety phenotype complicated by hypoactivity and defensiveness. Neuroscience. 2009;164:1431–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.J.Hendricks T. ETS gene plays a critical role in 5-HT neuron development and is required for normal anxiety-like and aggressive behavior. Neuron. 2003;37:233–47. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mosienko V, Bert B, Beis D, Matthes S, Fink H, Bader M, et al. Exaggerated aggression and decreased anxiety in mice deficient in brain serotonin. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e122. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ansorge MS, Zhou M, Lira A, Hen R, Gingrich JA. Early-life blockade of the 5-HT transporter alters emotional behavior in adult mice. Science. 2004;306:879–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1101678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buhot MC, Martin S, Segu L. Role of serotonin in memory impairment. Ann Med. 2000;32:210–21. doi: 10.3109/07853890008998828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naughton M, Mulrooney JB, Leonard BE. A review of the role of serotonin receptors in psychiatric disorders. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2000;15:397–415. doi: 10.1002/1099-1077(200008)15:6<397::AID-HUP212>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heisler LK, Zhou L, Bajwa P, Hsu J, Tecott LH. Serotonin 5-HT(2C) receptors regulate anxiety-like behavior. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:491–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nautiyal KM, Tritschler L, Ahmari SE, David DJ, Gardier AM, Hen R. A lack of serotonin 1B autoreceptors results in decreased anxiety and depression-related behaviors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:2941–50. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]