Abstract

Fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) is a powerful method to develop potent small-molecule compounds starting from fragments binding weakly to targets. As FBDD exhibits several advantages over high-throughput screening campaigns, it becomes an attractive strategy in target-based drug discovery. Many potent compounds/inhibitors of diverse targets have been developed using this approach. Methods used in fragment screening and understanding fragment-binding modes are critical in FBDD. This review elucidates fragment libraries, methods utilized in fragment identification/confirmation, strategies applied in growing the identified fragments into drug-like lead compounds, and applications of FBDD to different targets. As FBDD can be readily carried out through different biophysical and computer-based methods, it will play more important roles in drug discovery.

Keywords: fragment-based drug discovery, screening, drug discovery, structural biology, lead design

Introduction

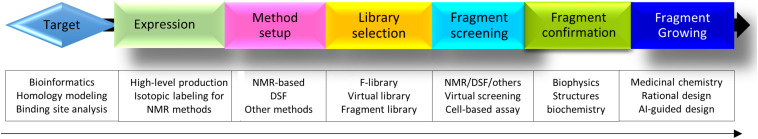

Fragment-based drug design (FBDD) is an approach to develop potent compounds from fragments. FBDD usually generates a compound starting from a chemical fragment with a low binding affinity to the target, low complexity in chemical structures and low molecular weight (less than 300 Da) (Murray and Rees, 2009; Doak et al., 2016). These starting hits are usually identified from a compound library using sensitive biophysical methods. The identified hit is then grown into drug-like molecules through different strategies. Although FBDD cannot replace high-throughput screening (HTS) campaigns in drug discovery, it has some attractive advantages such as saving experimental cost, offering diverse hits, and exhibiting multiple ways to develop novel compounds (Erlanson et al., 2016). These advantages have encouraged researchers to adopt this method to develop inhibitors of different types of targets. With the development of new approaches in screening and progress made in structural biology, FBDD has been readily carried on and playing important roles in target-based drug discovery (Bollag et al., 2010, 2012; Harner et al., 2013). Several drugs such as vemurafenib-an inhibitor of oncogenic B-RAF kinase activity derived from fragment-based approach have been approved by FDA (Erlanson, 2012). With more and more compounds derived from FBDD entering different stages of clinical studies, this method has been highly recognized in drug discovery. To carry out a fragment screening experiment, following procedures are usually required, namely selecting a compound library, setting up a method for hits identification, determining structures of fragment-target complexes, developing an assay for analyzing structure-activity relationship (SAR) and designing a strategy to grow the fragment into a potent inhibitor (Figure 1). In this review, fragment library, methods utilized in fragment screening, strategies applied in fragment optimization and targets that have been studied using FBDD are summarized. With more and more compounds developed through this method, FBDD will be playing essential roles in target-based drug discovery (Whittaker et al., 2010; Jacquemard and Kellenberger, 2019).

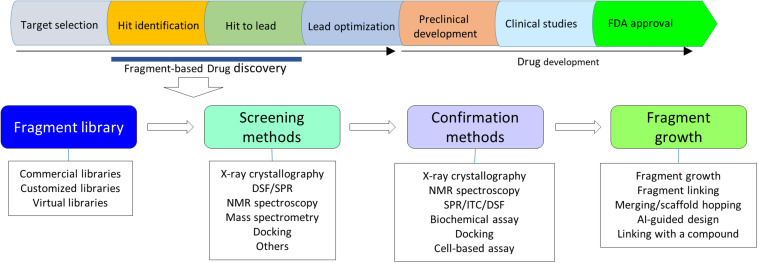

FIGURE 1.

A flowchart of FBDD. Upper panel shows steps in a target-based drug discovery. Lower panel shows a flowchart in FBDD. X-ray crystallography should be always considered in FBDD. NMR plays critical roles in fragment screening.

Fragment Library

There are no strict rules for the size and the number of compounds in a library. The term of fragment indicates that the molecular weight of compounds is relatively small, which gives rise to high ligand efficiency and provides more opportunities for growing the hits. It is suggested that fragments should follow the rules-of-three in which compounds have a molecular weight less than 300 Da, ClogP value less than three, and less than three hydrogen donors and acceptors (Congreve et al., 2003). Recent studies indicated that a fragment does not have to follow the rule-of-three as the fragment in screening utilizes simple organic compounds that can be modified efficiently (Jhoti et al., 2013). Researchers usually have their own customized libraries in FBDD and molecular weight of a fragment can be above 300 Da. In a virtual screening, the fragment library can be expanded with increasing diversity as the screening can be accomplished in a short time. As fragments can provide diverse compounds for optimization, the number of compounds in the fragment library is not a limitation factor. A potent compound was able to be developed through FBDD in which a library of about 800 fragments was utilized (Sabbah et al., 2020). Quite a few fragment libraries are commercially available (Singh et al., 2018). Many researchers have built up their own fragment libraries based on their respective experience (Garner et al., 2019; Heidrich et al., 2019). The customized library usually does not contain molecules that are reactive to targets, bind to proteins un-specifically, form aggregate or form covalent bonds with proteins. One of the fragment libraries in Fesik group consists of approximately 14,000 compounds with a molecular weight of 100–250 Da. Some compounds are following the rule-of-three while some compounds have four hydrogen donors and ClogP value up to 3.5 (Harner et al., 2013). A different library with scaffold-like compounds was utilized for screening kinase inhibitors. This library contains approximately 20,000 compounds with selected chemical properties and molecular weight of 150–350 Da (Bollag et al., 2012). The availability of diverse compound libraries makes FBDD possible to be applied to various targets (Kidd et al., 2018).

Fragment Screening Methods

Binding affinities between fragments and their targets are normally very low in micromolar to millimolar range. Probing fragment and target interactions through biochemical methods which are based on spectrophotometric and fluorescence assays is very challenging. Therefore, other sensitive approaches that are able to determine low binding affinities are very useful in hit identification. These approaches such as differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF), isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), surface plasmon resonance (SPR), and X-ray crystallography have been widely used in FBDD.

Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF)

Differential scanning fluorimetry is to measure thermally induced protein denature in the presence of a fluorescence dye such as Synpro Orange that binds to hydrophobic regions of a protein. The method is based on a phenomenon that stability of most proteins decreases when the environmental temperature (Tm) is increased. The Tm at which the amounts of folded and unfolded proteins are equal is termed as melting Tm (Niesen et al., 2007). The compound binding to a protein enhances the Tm of a protein and such a compound is then considered as a positive hit. DSF is a sensitive method and also utilized to understand the effect of point mutations on protein stability (Gayen et al., 2011). DSF experiments can be performed at a medium or high throughput level, making this method more attractive in fragment screening. In the assay mixture, protein concentration is very low and only a small amount of sample is required, which is especially useful for some proteins with low yields or unstable at high concentrations (Niesen et al., 2007). The protein concentration is normally in μM range and the compound concentration is in mM range. Such a high ligand-to-protein ratio will give rise to significant shifts in Tm values. It has been noted that the shift of Tm is proportional to the concentration or affinity of fragments in most cases, but it is not straightforward to correlate the shifts in Tms of compounds with their binding affinities. It is always a good strategy to confirm the identified hits through other biophysical methods (Cramer et al., 2017; Hassaan et al., 2020; Figure 2). It has been noted that other factors such as protein dynamics might influence Tm changes induced by ligand binding. The ligand binding to a protein might not always result in a positive shift. Both positive and negative shifts in Tm values could be observed in a screening. Although DSF is a very powerful tool in FBDD, this approach also has some limitations such as low hit rate due to exhibiting no shift or negative shift of Tm for the ligand binding. Therefore, other methods to confirm the identified hits are required.

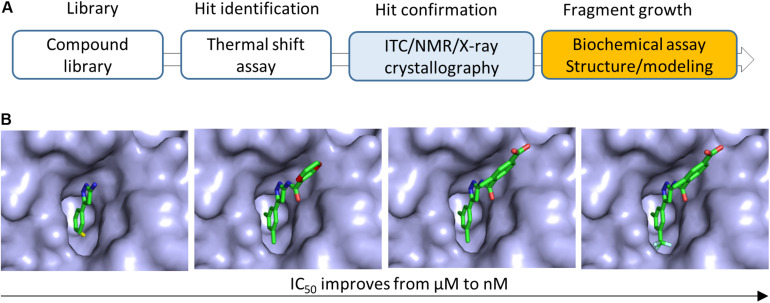

FIGURE 2.

Fragment growing in FBDD. (A) Flowchart of FBDD in developing inhibitors of bacterial Gyrase B. Methods utilized for growing fragments are indicated. (B) Fragment growing strategy was applied to grow a fragment to a potent compound. The IC50 of the compound was improved from 628 μM to 160 nM. This figure illustrated the modification of the compound (Chen et al., 2015). Details should be referred to the original publication (Chen et al., 2015).

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

Isothermal titration calorimetry is a powerful technique to measure binding affinity, binding stoichiometry and enthalpy changes of molecular interactions between a protein and a protein/ligand in solution. ITC experiment is usually carried out in following steps (Du et al., 2016). The first step is to titrate one molecule into a solution containing another molecule (protein). The second step is to monitor heat changes in the mixture. The final step is data analysis to obtain the required parameters. ITC has been routinely applied to determine binding affinities. Therefore, it is very useful to rank binding capabilities of molecules against a protein, making it very attractive in selecting hits for further development. ITC can also be applied in hit-to-lead and lead optimization steps in which SAR can be interpreted. Although ITC is very useful to characterize protein and ligand interactions, there are some limitations which hinder its application in some drug discovery projects. It is not an efficient tool in fragment screening due to the following drawbacks. Firstly, fragments with low binding affinities might not give measurable results easily, making this method unable to identify weak binders. Secondly, it is a time-consuming technique and a large amount of protein sample is required in comparison with other techniques such as DSF. Lastly, not every protein is suitable for ITC studies as protein aggregation and dynamics might affect the results. Nonetheless, ITC is still a powerful tool in drug discovery furnishing useful information for protein–ligand interactions while experimental conditions need to be optimized.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

Surface plasmon resonance has been widely applied in probing protein–protein, protein–ligand, protein–DNA/RNA, and DNA–DNA interactions in real time (Bakhtiar, 2013). In addition to measuring binding specificity, binding affinity and thermodynamic parameters, SPR is able to determine dissociation and association rate constants, which provides additional information to understand molecular interactions. This information is particularly useful in lead-optimization step as it offers information to understand the relationship between binding affinity and activity. The dissociation and association rates will guide medicinal chemists to better understand SAR. Immobilizing samples on a biosensor chip is a critical step in the measurement. There are various chips available for immobilizing protein samples. For example, samples can be attached on the surface of chips through covalent bond formation and non-covalent reaction via a high affinity molecule (Arslan Yildiz et al., 2013; Bakhtiar, 2013). Another advantage of SPR is that the amount of sample required for immobilization is very low and the sample immobilized on the chips can be reutilized. Therefore, proteins with low yields are applicable to this method. SPR is able to measure the off rates of ligands, which becomes prevalent in characterizing and ranking the identified hits in drug discovery (Murray et al., 2014).

Surface plasmon resonance has been shown to play important roles in screening and guiding cell-based assays. In the development of regulatory phosphatase PPP1R15B, SPR was utilized to rank small molecules binding to R15A and R15B as other available assays did not have sufficient sensitivity (Krzyzosiak et al., 2018). Based on the measured steady-state affinity of inhibitors for R15A-PP1, the authors were able to define a concentration for inhibitors used in cell-based assays (Krzyzosiak et al., 2018). This study provides an evidence that SPR can be performed in complicated systems in which multiple proteins are present. SPR has advantages in fragment screening over other biophysical methods as this approach consumes very little amount of protein samples and furnishes kinetics and thermodynamics for molecular interactions (Navratilova and Hopkins, 2010). SPR-based fragment screening has been successfully applied to different targets such as carbonic anhydrase II (Navratilova and Hopkins, 2010), thrombin, carbonic anhydrase, glutathione-S-transferase (Hämäläinen et al., 2008).

NMR Spectroscopy

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy is a powerful tool in drug discovery especially in FBDD. This technique is sensitive enough to identify fragments with different binding affinities (from nanomolar to millimolar). Compared with other methods, NMR screening gives rise to less false positive hits and a mixture of fragments can be screened. A number of NMR experiments have been utilized in FBDD by identifying various hits binding to a specific site on targets (Gossert and Jahnke, 2016; Norton et al., 2016; Li and Kang, 2017; Sugiki et al., 2018; Kang, 2019a, b). As shown in Table 1, several methods can be applied in fragment screening. All these experiments can be summarized as two methodologies. One is to monitor signal changes from fragments (ligands) and the other is to monitor signal changes from targets (proteins). Monitoring signals from ligands in the absence and presence of the target protein is an economic strategy in screening (Mayer and Meyer, 1999). In this method, the amount of the target protein required for screening is less than that utilized in protein-observed NMR studies. Saturation transfer difference spectroscopy (STD) (Mayer and Meyer, 1999; Munawar et al., 2018) and Water-LOGSY (Dalvit et al., 2001) are frequently applied in hit identification. As signal changes from compounds can be monitored through these two methods, there is no limitation for the size of the target protein. Although compound mixtures can be utilized in screening, the number of compounds is limited due to signal overlap. These methods can be also applied to rank binding affinities of the screened hits and determine which groups of the hits are critical for binding (Aretz and Rademacher, 2019).

TABLE 1.

Some NMR methods frequently used in screening.

| Experiments | Signal origin | References |

| STD | Ligands | Mayer and Meyer, 1999; Viegas et al., 2011 |

| Water Logsy | Ligands | Dalvit et al., 2001 |

| 1H-15N/13C-HSQC | Proteins | Hajduk et al., 1999, 2000, 2005; Petros et al., 2006; Williamson, 2013 |

| 19F-NMR | Proteins and ligands | Gee et al., 2016; Norton et al., 2016 |

| 31P-NMR | Ligands | Manzenrieder et al., 2008 |

| 1D-NMR | Target-immobilized NMR, ligands | Vanwetswinkel et al., 2005 |

| NOESY | Proteins and ligands | Becattini and Pellecchia, 2006 |

| PRE | Protein modified with a probe | Akter et al., 2019 |

19F-NMR is an efficient approach when it is applied in fragment screening (Norton et al., 2016). Fluorine atom is not present in biological molecules while it is commonly used in drug discovery as it can improve the property of compounds. Therefore, 19F-NMR has no background for biological samples, giving rise to clear signals. Like proton atoms, 19F nucleus has 100% natural abundance, making it measured easily in NMR experiments. The high signal sensitivity (83% of protons) makes it attractive in drug discovery as samples with low concentrations can be measured. The wide dispersion of 19F signals make it possible to use fragment mixtures in screening, which saves the data acquisition time. The availability of 19F-labeled compound libraries makes 19F-NMR more powerful in FBDD (Kang, 2019b; Lingel et al., 2020). 19F-NMR is most attractive in fragment screening for the reason that a mixture of compounds can be screened and the correct hit can be readily picked out, making it become a high-throughput method.

Another frequently used method in probing protein–ligand interactions is 1H-15N-HSQC (hetero-nuclear single quantum coherence spectroscopy) experiment in which chemical shifts of amino acids of a protein are compared in the absence and presence of a ligand. This method is able to confirm molecular interactions between a target and a ligand, determine the binding affinity and map the ligand binding site. It has been noted that this method has been widely utilized to confirm interactions of ligands with different binding affinities to a target. Based on docking software such as HADDOCK (High Ambiguity Driven biomolecular DOCKing), the protein–ligand complex can be obtained according to the chemical shift perturbation induced by ligand binding (Proudfoot et al., 2017). This approach is particularly useful for a target which is difficult to be crystallized (Li et al., 2018a). Unlike proton or 19F-NMR experiments, 1H-15N-HSQC experiment requires the target protein to be isotopically labeled. Since SAR by NMR was proposed in 1996 (Shuker et al., 1996), this method has been widely applied in FBDD. The cost in protein production can be reduced by using sensitive probes, low-volume samples, more sensitive or faster data acquisition strategies, application of compound mixtures in screening and recycle of the protein sample (Hajduk et al., 1997).

X-Ray Crystallography

X-ray crystallography is a powerful tool to obtain structures of proteins and complexes at high resolutions. It plays essential roles in structure-based drug discovery (Hartshorn et al., 2005; Thomas et al., 2019). Many potent inhibitors were developed based on the structural information obtained through X-ray crystallography (Salah et al., 2011). There is no doubt that co-crystal structures offer direct and clear information to understand SAR and mechanism of action of the developed compounds (Carvalho et al., 2010). X-ray structures furnish structural information to understand binding modes of various inhibitors that bind to the active site of a target, inhibit the target through allosteric mechanisms and form covalent bonds with the target (Li et al., 2017a, b, 2018b; Anantharajan et al., 2019; Zhong et al., 2019). X-ray crystallography is a robust method that can be applied in fragment hit identification and confirmation (Schiebel et al., 2016a; Glockner et al., 2020). The bottleneck in X-ray structural studies is to obtain the crystals of targets and complexes (Carpenter et al., 2008). X-ray crystallography plays important roles in FBDD as fragments can be soaked into crystals to obtain their binding modes at a high resolution (Böttcher et al., 2011). Combination of X-ray structures with other biophysical methods is commonly used in drug discovery (Wyss et al., 2012; Munzker et al., 2020). It has been noted that not all targets can be crystallized for X-ray studies. Sometimes, the initial fragments soaked into crystals of the target might not generate high-resolution structures. Under such conditions, other biophysical methods have to be applied to guide fragment growth (Erlanson et al., 2019).

Computational-Based Methods

Virtual screening has been applied in fragment screening (Erlanson et al., 2004a; Behnen et al., 2012; Abdulmalek et al., 2020; De Souza Neto et al., 2020), furnishing diverse chemical structures as the number of libraries in a virtual screening is not a limitation factor (Hoffer et al., 2013). This strategy usually includes structure determination of the target, virtual library preparation, docking, and hit confirmation through docking and MD simulation (Bian and Xie, 2018; De Souza Neto et al., 2020). A library with a large number of fragments can be screened, which offers a high hit rate (Zoete et al., 2009). Artificial intelligence (AI) will furnish a rational design in the hit-to-lead step. An example has been cited in the development of inhibitors of the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 (Choudhury, 2020).

Other Methods

While aforementioned methods are useful in FBDD, other methods that are able to probe protein–ligand interactions have been utilized in FBDD. An anchoring approach was applied to develop protease inhibitors (Hassaan et al., 2020; Konstantinidou et al., 2020). Capillary electrophoresis was successfully applied to identify fragment hits binding to heat shock protein 90 ATPase (Austin et al., 2012). Weak affinity chromatography was developed as a tool to screen hits in FBDD (Duong-Thi et al., 2011). Fragment-based screening was also carried out using cell-based assays (Szõllõsi et al., 2015; Schulze et al., 2018). A study showed that fragments reacting with cysteine residues were able to identify proteins that formed interactions with these compounds (Backus et al., 2016). Mass spectrometry is particular useful for identifying fragments that form covalent interactions with targets (Pedro and Quinn, 2016). In practice, any methods that can probe protein–ligand interactions can be utilized in fragment screening while experimental cost and time have to be considered. Whenever possible, application of X-ray crystallography in FBDD should be considered, which will offer a clear guidance for fragment growth (Schiebel et al., 2016b). In a FBDD, the following strategy can be considered (Figure 1). Bioinformatics analysis of a target should be carried on and its ligand binding site could be analyzed upon an available structure/model. Crystallization trials will be first applied to the target, if the fragment could be soaked into the crystals (Schiebel et al., 2016a, b). Virtual screening, DSA and NMR will be considered in fragment identification when a protein structure is available and the target protein can be purified easily (Figure 1).

Compound Optimization

As fragments usually bind weakly to targets and exhibit no potent inhibitory effect on the activity of the targets, further chemical modification of the hits is required in hit-to-lead step. In this procedure, hits will be developed into leads which bind to the target with higher affinities and exhibit potent activities against the target (Erlanson, 2006; Erlanson et al., 2016; Lamoree and Hubbard, 2017). Three strategies namely fragment growing, fragment hopping, and fragment linking are frequently utilized.

Growing of Fragment Hits

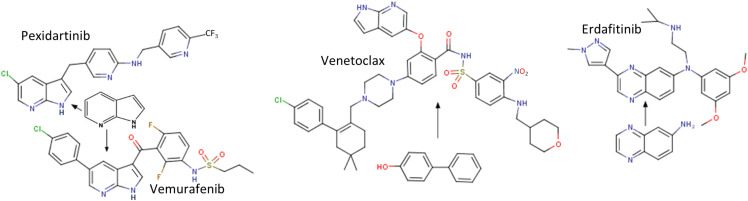

Fragment growing is the most commonly used strategy to grow fragments into compounds with higher molecular weights and higher potencies. Various chemical groups can be added to the building block (hit) to improve its potency (Mondal et al., 2016; Lamoree and Hubbard, 2017). Co-crystal structures of hits with the target are very important for fragment growing (Tao et al., 2015). It has been noted that a fragment can be grown into a potent compound even without structural information (Erlanson et al., 2019). Availability of biochemical or biophysical assays to understand SAR is critical in hit-to-lead step. This strategy has been proven to be successful in numerous targets such as developing bacterial Gyrase B inhibitors (Figure 2; Chen et al., 2015). It has been noted that the four approved drugs were developed by this strategy (Figure 3; Tsai et al., 2008; Souers et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Murray C.W. et al., 2019). The details of these drugs and other compounds in clinical studies are listed in the Practical Fragments blog website1.

FIGURE 3.

Structures of four approved drugs derived from FBDD. PLX3397 (Pexidartinib) was started from 7-azaindole (Zhang et al., 2013). Vemurafenib was built from the same fragment (Tsai et al., 2008). Structures of Venetoclax (an inhibitor of Bcl2) (Souers et al., 2013) and Erdafitinib (Murray C.W. et al., 2019) are shown. More information about FBDD can be obtained from the blog website http://practicalfragments.blogspot.com/.

Merging/Scaffold Hopping of Fragment Hits

Fragment merging or scaffold hopping is another strategy to grow fragments into potent compounds (Miyake et al., 2019). This strategy is based on condition that the identified fragments have an overlapped binding site. Potent compounds can be developed by combining/merging chemical features of two or more fragments (Temple et al., 2019). To carry out fragment merging of the identified hits, binding modes of fragments should be determined through X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or docking methods. This strategy is very useful for replacing non-drug like core structures in the hits with suitable scaffolds to generate more drug-like molecules (Harner et al., 2013). In addition, it offers a chance to generate more patentable compounds (Lamberth, 2018). Unlike the fragment growth strategy, fragment merging requires structural information to understand the binding mode or certain type of experiments such as STD–NMR to determine which part of the ligand is critical for binding. This strategy has been successfully applied in several targets (Fradera et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020) such as the development of inhibitors of cytochrome P450 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by which fragment merging of the hits resulted in a compound with 15–60 fold improvement in binding affinity comparing to its origins (Hudson et al., 2012).

Fragment Linking

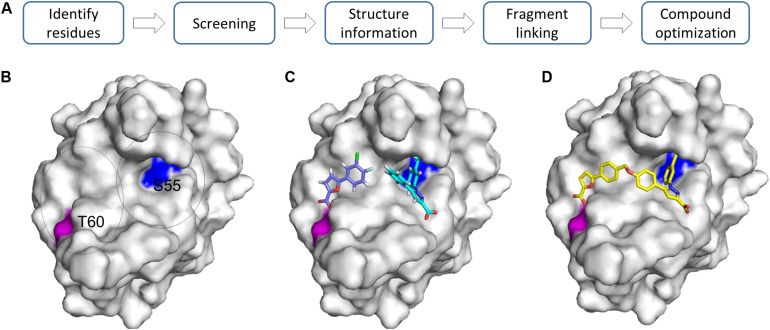

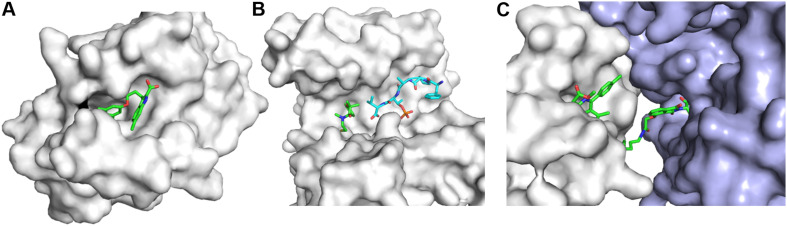

Fragment linking is considered as the most powerful way to develop potent inhibitors from fragments. A lead compound can be developed by linking two or more fragments together (Mondal et al., 2016). This is an attractive strategy as binding affinities can be improved dramatically (Mondal et al., 2016). Based on the calculated binding free energy, linking two fragments with binding affinities in mM range will result in a compound with an affinity in nM range (Ichihara et al., 2011; Harner et al., 2013). The challenge in this strategy is to identify fragments that are in close proximity and the introduced linker has no negative effect on the activity of the fragment. The target usually should have a relatively large binding pocket to enable identification of hits binding to different regions in the pocket. Extensive structural information is helpful to understand such molecular interactions. Ideally, this strategy can be carried on when the ligand binding pocket contains two sites with different binding affinities to the fragment (Harner et al., 2013). The first binding site favors identifying fragments with higher binding affinities. To identify fragments binding to the second binding site, the first binding site should be blocked using identified compounds. This can be achieved by growing a fragment into a more potent fragment or inducing a Cys residue at the first site to form a covalent bond with the fragment (Erlanson et al., 2004b). Then the target with the first site occupied can be utilized for screening another type of fragments (Erlanson et al., 2004b). Fragments binding to different sites can also be selectively screened by designing a spy molecule which is fully characterized through different methods (Skora and Jahnke, 2017). Screening can be carried out to monitor release of the spy molecule, which is able to identify the required fragments. 19F-based NMR is very useful for achieving this goal (Li and Kang, 2017; Kang, 2019b). 1H-15N-HSQC based screening plays important roles in screening fragments binding to different sites. This strategy has been successfully applied in the development of compounds binding to replication protein A (RPA70) (Frank et al., 2013). In the study, the N-terminal region of RPA70 composed of approximately 110 amino acids was labeled and utilized for fragment screening (Frank et al., 2013). To analyze the identified hits, the potential ligand binding sites were analyzed carefully. Two residues S55 and T60 from two sites in close proximity were selected to identify the required fragments. Fragments affecting chemical shift of S55, T60 or both were classified (Figure 4). By linking the identified fragments, a potent inhibitor was developed.

FIGURE 4.

Growing fragments through fragment-linking. (A) Strategy for FBDD. (B) Two representative residues are identified in the same pocket. (C) Two fragments were identified and selected for linking experiments. (D) A linked compound was developed. The structures (PDB id 4LUZ and 4LUV) of protein–ligand complexes are shown. The protein is shown as a surface and compounds are shown as sticks. For more information, please refer to the original publication (Frank et al., 2013).

Growing fragment hits into potent leads can be performed in different strategies, which depends on the hit rate, available structural information, availability of assays for SAR, and assays used for screening (Sommer et al., 2019). Identified fragments can also be linked with hits from HTS, which is seen in a recent study and provides an efficient way to develop potent inhibitors of undruggable targets (Hillig et al., 2019). With the development of docking methods, these computation-based strategies will play a role in guiding fragment growth (Korczynska et al., 2016).

Targets for FBDD

Fragment-based drug discovery is mainly applicable to target-based drug discovery. Druggability of a target is always analyzed in target-based drug discovery projects and is utilized to predict possibility of developing drugs by identifying a pocket favoring binding to small-molecule compounds (Aretz et al., 2016; Gee et al., 2016). In most cases, druggable targets are of great interests as the probability to develop small molecule drugs is very high (Dang et al., 2017). FBDD has been applied to quite a few druggable and undruggable targets (Stamford and Strickland, 2013; Kessler et al., 2019). Some examples are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

List of some targets with inhibitors designed using FBDD*.

| Targets | Methods | References |

| KRAS | NMR and microscale thermophoresis | Kessler et al., 2019 |

| PYCR1 | Biochemical assay | Milne et al., 2019 |

| Colony-stimulating factor 1 | Computational approach | Machiraju et al., 2019 |

| Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase | Mass spectrometry | Hopkins et al., 2019 |

| The atypical protein kinase C-iota | Thermal shift assay | Kwiatkowski et al., 2018, 2019 |

| Latency-associated nuclear antigen | SPR, DSF | Kirsch et al., 2019 |

| Monoamine oxidase | X-ray crystallography | Cheng et al., 2019 |

| Myeloid cell leukemia 1 | NMR | Murray J.B. et al., 2019; Szlávik et al., 2019 |

| β-ketoacyl-ACP synthases | X-ray crystallography | Patterson et al., 2020 |

| VEGFR-2 | Computational design | Zhang et al., 2019 |

| West Nile viral protease | STD-NMR | Schöne et al., 2017 |

| Transcriptional repressor EthR2 | TSA and X-ray | Prevet et al., 2019 |

| Programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) | NMR and X-ray | Perry et al., 2019 |

| Estrogen Receptor α and 14-3-3 (PPI) | MS and X-ray | Sijbesma et al., 2019 |

| The RNA-dependent RNA polymerase | X-ray | Riccio et al., 2019 |

| Apical membrane antigen 1 | PRE, NMR | Akter et al., 2019 |

| Glyoxalase 1 | Computational approach | Perez et al., 2019 |

| Focal Adhesion Kinase | SPR and NMR | Alvarado et al., 2019 |

| E. coli DsbA | NMR/X-ray | Duncan et al., 2019 |

| PDEδ-RAS (PPI) | STD, CMPG-NMR | Chen et al., 2019 |

*This table lists some studies using FBDD. Only a few studies published in 2019 were list for elucidating the application of FBDD to multiple targets. There are over two hundred publications in 2019 and over one hundred publications as of June 2020 when fragment-based drug discovery is searched as a keyword in pubmed (http://www.pubmed.gov).

Targets With a Well-Defined Pocket

Druggability is utilized to evaluate whether a small-molecule drug can be developed to affect the biological function of a protein (Owens, 2007). Several methods are applied to determine the druggability of targets (Cheng et al., 2007), which is important in drug discovery. A druggable target usually contains a hydrophobic pocket favoring its binding to hydrophobic compounds. However, undruggable targets do not have a pocket or the pocket is highly hydrophilic and shallow. This type of targets includes unstructured proteins that play important roles in disease regulation. A high hit rate can be obtained when FBDD is applied to these druggable targets, furnishing more candidates for further development. For example, several research groups have carried out FBDD against bacterial Gyrase B, and they have developed compounds with different scaffolds (Basarab et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2015).

Targets With a Shallow Pocket

An undruggable target refers to those proteins with shallow pockets un-favoring small molecule interactions (Dang et al., 2017). Many undruggable targets are important for cancer development. These targets include protein–protein interactions (PPIs), transcription factors, phosphatases, Ras proteins, and others (Arkin et al., 2014; Dang et al., 2017). These undruggable targets are usually not considered in small-molecule drug discovery due to challenges in hit identification and lead optimization. Accumulated studies have shown that it is still feasible to develop small molecules binding to these targets (Macalino et al., 2018; Das et al., 2019). One strategy is to develop allosteric inhibitors which induce a new binding site to affect function of the target (Anantharajan et al., 2019). FBDD is successful in the development of KRAS inhibitors. KRAS is a validated target due to its association with cancer initiation and progression (Kano et al., 2019). It was considered as an undruggable target due to lacking of a pocket that is suitable for small molecule binding (Welsch et al., 2017). Potent KRAS inhibitors have been developed using FBDD, proving that this method is very powerful in drug discovery.

Fragment-based drug discovery has been applied for developing compounds targeting PPIs (Si et al., 2019; Figure 5). Several strategies such as hot spot and allosteric site identification can be pursued for this type of targets (Turnbull et al., 2014). It is known that many PPIs are important in drug discovery while the development of small-molecule inhibitors disrupting such targets is challenging (Laraia et al., 2015; Goncearenco et al., 2017). Although HTS campaign is a strategy to identify hits, FBDD is playing important roles in developing various types of compounds disrupting or initiating PPIs as assays for hit screening can be set up easily (Patrone et al., 2013; Turnbull et al., 2014). Compounds affecting PPIs will be achieved through the following mechanisms. Firstly, compounds bind to one protein to generate a protein–ligand complex that does not favor the interaction with another protein. Secondly, compounds are able to stabilize PPIs to affect certain signaling pathways (Andrei et al., 2017). Disulfide screening paradigm was utilized to screen fragments that affect the interaction between 14-3-3σ and a peptide derived from Estrogen Receptor α, offering a strategy to develop PPI stabilizers (Sijbesma et al., 2019). Lastly, compound binding to proteins induces PPIs in which the two proteins are not physically interacting under physiological conditions. A proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTAC) is a multi-functional compound that can link a target of interest with an E3 ligase resulting in protein degradation (Lu et al., 2015; Gadd et al., 2017; Pettersson and Crews, 2019).

FIGURE 5.

Three types of compounds targeting PPIs. (A) An inhibitor binding to PPI interface to disrupt PPIs. The structure of the complex (PDB id 4HW2) is shown. The development of myeloid cell leukemia inhibitors was described in the reference (Friberg et al., 2013). (B) A PPI stabilizer. The structure (PDB id 6HHP) is shown. A fragment forms a disulfide bond with the target and a fragment from another protein is shown in cyan (Sijbesma et al., 2019). (C) Ligand-induced PPIs. The structure (PDB id 6BN7) is shown. BRD4 and CRBN are shown in white and light blue, respectively. Proteins in this figure are shown in surface representation and compounds are shown as sticks.

Perspectives

Fragment-based drug discovery has been applied to various targets and plays important roles in target-based drug discovery. This method is also very important in chemical biology by developing high-quality chemical probes for diverse targets (Scott et al., 2012). FBDD can be pursued by considering the following steps (Figure 6). Firstly, when a target is defined, bioinformatics will be applied to understand the structure which can be obtained from X-ray crystallography or other methods such as homology modeling. Secondly, the target protein will be overexpressed. If the isotopically labeled protein can be easily purified and the purified protein exhibited dispersed cross-peaks in 1H-15N-HSQC spectrum, this protein-based NMR can be considered in screening. Otherwise, DSF, or 19F-NMR will be utilized in fragment screening. X-ray crystallography will be the first method in screening if the target can be crystallized easily. Virtual screening can be always carried out when a structure of the target is available. Thirdly, a suitable library will be selected from many sources, which is not a limitation factor. Fourthly, hit confirmation will be performed through structural, biophysical and biochemical methods. Lastly, fragment growth can be utilized via suitable strategies. Medicinal chemists will play key roles in this step.

FIGURE 6.

A flowchart of FBDD. The steps required in FBDD are listed. Structural information of the target with a fragment is always helpful for fragment growth. X-ray, DSF, and NMR are commonly used methods in fragment screening.

Conclusion

Fragment-based drug discovery should be applied in drug discovery projects. FBDD is applicable to diverse targets and the hit rate of fragment screening can be also utilized to assess druggability of a target, which can further guide HTS activities to offer an evidence to make Go or No-Go decision for a project. In addition, FBDD is very useful for developing potent binders of a protein which does not have enzymatic activity.

Author Contributions

QL conceived the study and wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

QL appreciates the support from Guangdong Bioengineering Institute (Guangzhou Sugarcane Industry Research Institute), Guangdong Academy of Sciences, Guangdong, China.

Funding. This research was supported by funds from the “Hundred-Talent Program” (Grant Numbers: 2020GDASYL-20200102010 and 2020GDASYL-20200102009), Guangdong Academy of Sciences, China.

References

- Abdulmalek A. B., Sufyan M. A., Abdulrahman K. A., Mohammed A. K. (2020). Fragment-based discovery of potential anticancer lead: computational and in vitro studies. Curr. Comput. Aid. Drug Design 16 1–9. 10.2174/1573409916666200620195025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akter M., Drinkwater N., Devine S. M., Drew S. C., Krishnarjuna B., Debono C. O., et al. (2019). Identification of the binding site of apical membrane antigen 1 (AMA1) inhibitors using a paramagnetic probe. ChemMedChem 14 603–612. 10.1002/cmdc.201800802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado C., Stahl E., Koessel K., Rivera A., Cherry B. R., Pulavarti S. V. S. R. K., et al. (2019). Development of a fragment-based screening assay for the focal adhesion targeting domain using SPR and NMR. Molecules 24 3352. 10.3390/molecules24183352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharajan J., Zhou H., Zhang L., Hotz T., Vincent M. Y., Blevins M. A., et al. (2019). Structural and Functional analyses of an allosteric EYA2 phosphatase inhibitor that has on-target effects in human lung cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Therapeut. 18 1484–1496. 10.1158/1535-7163.mct-18-1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrei S. A., Sijbesma E., Hann M., Davis J., O’Mahony G., Perry M. W. D., et al. (2017). Stabilization of protein-protein interactions in drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 12 925–940. 10.1080/17460441.2017.1346608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aretz J., Kondoh Y., Honda K., Anumala U. R., Nazaré M., Watanabe N., et al. (2016). Chemical fragment arrays for rapid druggability assessment. Chem. Commun. 52 9067–9070. 10.1039/C5CC10457B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aretz J., Rademacher C. (2019). Ranking Hits From saturation transfer difference nuclear magnetic resonance–based fragment screening. Front. Chem. 7:215. 10.3389/fchem.2019.00215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkin M. R., Tang Y., Wells J. A. (2014). Small-molecule inhibitors of protein-protein interactions: progressing toward the reality. Chem. Biol. 21 1102–1114. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan Yildiz A., Kang C., Sinner E. K. (2013). Biomimetic membrane platform containing hERG potassium channel and its application to drug screening. Analyst 138 2007–2012. 10.1039/c3an36159d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin C., Pettit S. N., Magnolo S. K., Sanvoisin J., Chen W., Wood S. P., et al. (2012). Fragment Screening Using capillary electrophoresis (CEfrag) for hit identification of heat shock protein 90 ATPase inhibitors. J. Biomol. Screening 17 868–876. 10.1177/1087057112445785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backus K. M., Correia B. E., Lum K. M., Forli S., Horning B. D., González-Páez G. E., et al. (2016). Proteome-wide covalent ligand discovery in native biological systems. Nature 534 570–574. 10.1038/nature18002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtiar R. (2013). Surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy: a versatile technique in a biochemist’s toolbox. J. Chem. Educ. 90 203–209. 10.1021/ed200549g [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basarab G. S., Manchester J. I., Bist S., Boriack-Sjodin P. A., Dangel B., Illingworth R., et al. (2013). Fragment-to-hit-to-lead discovery of a novel pyridylurea scaffold of ATP competitive dual targeting type II topoisomerase inhibiting antibacterial agents. J. Med. Chem. 56 8712–8735. 10.1021/jm401208b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becattini B., Pellecchia M. (2006). SAR by ILOEs: an NMR-based approach to reverse chemical genetics. Chemistry 12 2658–2662. 10.1002/chem.200500636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnen J., Köster H., Neudert G., Craan T., Heine A., Klebe G. (2012). Experimental and computational active site mapping as a starting point to fragment-based lead discovery. ChemMedChem 7 248–261. 10.1002/cmdc.201100490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian Y., Xie X.-Q. S. (2018). Computational fragment-based drug design: current trends, strategies, and applications. AAPS J. 20:59. 10.1208/s12248-018-0216-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollag G., Hirth P., Tsai J., Zhang J., Ibrahim P. N., Cho H., et al. (2010). Clinical efficacy of a RAF inhibitor needs broad target blockade in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Nature 467:596. 10.1038/nature09454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollag G., Tsai J., Zhang J., Zhang C., Ibrahim P., Nolop K., et al. (2012). Vemurafenib: the first drug approved for BRAF-mutant cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 11:873. 10.1038/nrd3847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böttcher J., Jestel A., Kiefersauer R., Krapp S., Nagel S., Steinbacher S., et al. (2011). “Chapter three–key factors for successful generation of protein–fragment structures: requirement on protein, crystals, and technology,” in Methods in Enzymology, ed. Kuo L. C. (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press; ), 61–89. 10.1016/b978-0-12-381274-2.00003-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter E. P., Beis K., Cameron A. D., Iwata S. (2008). Overcoming the challenges of membrane protein crystallography. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 18 581–586. 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho A. L., Trincão J., Romão M. J. (2010). “X-ray crystallography in drug discovery,” in Ligand-Macromolecular Interactions in Drug Discovery: Methods and Protocols, ed. Roque A. C. A. (Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; ), 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- Chen D., Chen Y., Lian F., Chen L., Li Y., Cao D., et al. (2019). Fragment-based drug discovery of triazole inhibitors to block PDEδ-RAS protein-protein interaction. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 163 597–609. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G.-Y., Ng F. M., Tan Y. W., Poulsen A., Seetoh W., Lin G., et al. (2015). Application of fragment-based drug discovery against DNA Gyrase B. ChemPlusChem 80 1250–1254. 10.1002/cplu.201500197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng A. C., Coleman R. G., Smyth K. T., Cao Q., Soulard P., Caffrey D. R., et al. (2007). Structure-based maximal affinity model predicts small-molecule druggability. Nat. Biotechnol. 25 71–75. 10.1038/nbt1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng K., Li S., Lv X., Tian Y., Kong H., Huang X., et al. (2019). Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel human monoamine oxidase B inhibitors based on a fragment in an X-ray crystal structure. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. Lett. 29 1012–1018. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury C. (2020). Fragment tailoring strategy to design novel chemical entities as potential binders of novel corona virus main protease. J. Biomol. Struct. Dynam. 20 1–14. 10.1080/07391102.2020.1771424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congreve M., Carr R., Murray C., Jhoti H. (2003). A ‘Rule of Three’ for fragment-based lead discovery? Drug Discovery Today 8 876–877. 10.1016/S1359-6446(03)02831-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer J., Schiebel J., Wulsdorf T., Grohe K., Najbauer E. E., Ehrmann F. R., et al. (2017). A false-positive screening hit in fragment-based lead discovery: watch out for the red herring. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 1908–1913. 10.1002/anie.201609824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalvit C., Fogliatto G., Stewart A., Veronesi M., Stockman B. (2001). WaterLOGSY as a method for primary NMR screening: practical aspects and range of applicability. J. Biomol. NMR 21 349–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang C. V., Reddy E. P., Shokat K. M., Soucek L. (2017). Drugging the ‘undruggable’ cancer targets. Nat. Rev. Cancer 17 502–508. 10.1038/nrc.2017.36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S. K., Sarkar D., Cavenee W. K., Emdad L., Fisher P. B. (2019). Rethinking glioblastoma therapy: MDA-9/syntenin targeted small molecule. ACS Chem. Neurosc. 10 1121–1123. 10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza Neto L. R., Moreira-Filho J. T., Neves B. J., Maidana R. L. B. R., Guimarães A. C. R., Furnham N., et al. (2020). In silico strategies to support fragment-to-lead optimization in drug discovery. Front. Chem. 8:93. 10.3389/fchem.2020.00093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doak B. C., Norton R. S., Scanlon M. J. (2016). The ways and means of fragment-based drug design. Pharmacol. Therapeut. 167 28–37. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X., Li Y., Xia Y.-L., Ai S.-M., Liang J., Sang P., et al. (2016). Insights into protein–ligand interactions: mechanisms, models, and methods. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17:144. 10.3390/ijms17020144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan L. F., Wang G., Ilyichova O. V., Scanlon M. J., Heras B., Abbott B. M. (2019). The fragment-based development of a benzofuran hit as a new class of Escherichia coli DsbA inhibitors. Molecules 24:3756. 10.3390/molecules24203756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duong-Thi M.-D., Meiby E., Bergström M., Fex T., Isaksson R., Ohlson S. (2011). Weak affinity chromatography as a new approach for fragment screening in drug discovery. Anal. Biochem. 414 138–146. 10.1016/j.ab.2011.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlanson D. A. (2006). Fragment-based lead discovery: a chemical update. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 17 643–652. 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlanson D. A. (2012). “Introduction to fragment-based drug discovery,” in Fragment-Based Drug Discovery and X-Ray Crystallography, eds Davies T. G., Hyvönen M. (Berlin: Springer; ), 1–32. 10.1007/128_2011_180 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erlanson D. A., Davis B. J., Jahnke W. (2019). Fragment-based drug discovery: advancing fragments in the absence of crystal structures. Cell Chem. Biol. 26 9–15. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlanson D. A., Fesik S. W., Hubbard R. E., Jahnke W., Jhoti H. (2016). Twenty years on: the impact of fragments on drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15 605–619. 10.1038/nrd.2016.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlanson D. A., McDowell R. S., O’Brien T. (2004a). Fragment-based drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 47 3463–3482. 10.1021/jm040031v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlanson D. A., Wells J. A., Braisted A. C. (2004b). Tethering: fragment-based drug discovery. Ann. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 33 199–223. 10.1146/annurev.biophys.33.110502.140409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fradera X., Methot J. L., Achab A., Christopher M., Altman M. D., Zhou H., et al. (2019). Design of selective PI3Kδ inhibitors using an iterative scaffold-hopping workflow. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. Lett. 29 2575–2580. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank A. O., Feldkamp M. D., Kennedy J. P., Waterson A. G., Pelz N. F., Patrone J. D., et al. (2013). Discovery of a potent inhibitor of replication protein a protein–protein interactions using a fragment-linking approach. J. Med. Chem. 56 9242–9250. 10.1021/jm401333u [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friberg A., Vigil D., Zhao B., Daniels R. N., Burke J. P., Garcia-Barrantes P. M., et al. (2013). Discovery of Potent myeloid cell leukemia 1 (Mcl-1) inhibitors using fragment-based methods and structure-based design. J. Med. Chem. 56 15–30. 10.1021/jm301448p [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadd M. S., Testa A., Lucas X., Chan K.-H., Chen W., Lamont D. J., et al. (2017). Structural basis of PROTAC cooperative recognition for selective protein degradation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13:514. 10.1038/nchembio.2329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner P., Cox P. B., Rathnayake U., Holloran N., Erdman P. (2019). Design and synthesis of pyrrolidine-based fragments that sample three-dimensional molecular space. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 10 811–815. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayen S., Li Q., Chen A. S., Nguyen T. H., Huang Q., Hill J., et al. (2011). An NMR study of the N-terminal domain of wild-type hERG and a T65P trafficking deficient hERG mutant. Proteins 79 2557–2565. 10.1002/prot.23089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee C. T., Arntson K. E., Urick A. K., Mishra N. K., Hawk L. M. L., Wisniewski A. J., et al. (2016). Protein-observed 19F-NMR for fragment screening, affinity quantification and druggability assessment. Nat. Protoc. 11:1414. 10.1038/nprot.2016.079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glockner S., Heine A., Klebe G. (2020). A Proof-of-concept fragment screening of a hit-validated 96-compounds library against human carbonic anhydrase II. Biomolecules 10:518. 10.3390/biom10040518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncearenco A., Li M., Simonetti F. L., Shoemaker B. A., Panchenko A. R. (2017). “Exploring protein-protein interactions as drug targets for anti-cancer therapy with in silico workflows,” in Proteomics for Drug Discovery: Methods and Protocols, eds Lazar I. M., Kontoyianni M., Lazar A. C. (New York, NY: Springer; ), 221–236. 10.1007/978-1-4939-7201-2_15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossert A. D., Jahnke W. (2016). NMR in drug discovery: a practical guide to identification and validation of ligands interacting with biological macromolecules. Prog. Nuclear Magnet. Resona. Spectros. 97 82–125. 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajduk P. J., Augeri D. J., Mack J., Mendoza R., Yang J., Betz S. F., et al. (2000). NMR-based screening of proteins containing 13C-labeled Methyl Groups. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122 7898–7904. 10.1021/ja000350l [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hajduk P. J., Huth J. R., Fesik S. W. (2005). Druggability indices for protein targets derived from NMR-based screening data. J. Med. Chem. 48 2518–2525. 10.1021/jm049131r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajduk P. J., Meadows R. P., Fesik S. W. (1997). Discovering high-affinity ligands for proteins. Science 278 497–499. 10.1126/science.278.5337.497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajduk P. J., Meadows R. P., Fesik S. W. (1999). NMR-based screening in drug discovery. Q. Rev. Biophys. 32 211–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hämäläinen M. D., Zhukov A., Ivarsson M., Fex T., Gottfries J., Karlsson R., et al. (2008). Label-free primary screening and affinity ranking of fragment libraries using parallel analysis of protein panels. J. Biomol. Screen. 13 202–209. 10.1177/1087057108314651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harner M. J., Frank A. O., Fesik S. W. (2013). Fragment-based drug discovery using NMR spectroscopy. J. Biomol. NMR 56 65–75. 10.1007/s10858-013-9740-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorn M. J., Murray C. W., Cleasby A., Frederickson M., Tickle I. J., Jhoti H. (2005). Fragment-based lead discovery using X-ray crystallography. J. Med. Chem. 48 403–413. 10.1021/jm0495778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassaan E., Hohn C., Ehrmann F. R., Goetzke F. W., Movsisyan L., Hüfner-Wulsdorf T., et al. (2020). Fragment screening hit draws attention to a novel transient pocket adjacent to the recognition site of the tRNA-modifying enzyme TGT. J. Med. Chem. 13 6802–6820. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidrich J., Sperl L. E., Boeckler F. M. (2019). Embracing the diversity of halogen bonding motifs in fragment-based drug discovery—construction of a diversity-optimized halogen-enriched fragment library. Front. Chem. 7:9. 10.3389/fchem.2019.00009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillig R. C., Sautier B., Schroeder J., Moosmayer D., Hilpmann A., Stegmann C. M., et al. (2019). Discovery of potent SOS1 inhibitors that block RAS activation via disruption of the RAS–SOS1 interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116 2551–2560. 10.1073/pnas.1812963116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffer L., Renaud J.-P., Horvath D. (2013). In Silico fragment-based drug discovery: setup and validation of a fragment-to-lead computational protocol using S4MPLE. J. Chem. Inform. Model. 53 836–851. 10.1021/ci4000163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins B. T., Bame E., Bell N., Bohnert T., Bowden-Verhoek J. K., Bui M., et al. (2019). Optimization of novel reversible Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors identified using tethering-fragment-based screens. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 27 2905–2913. 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson S. A., McLean K. J., Surade S., Yang Y.-Q., Leys D., Ciulli A., et al. (2012). Application of fragment screening and merging to the discovery of inhibitors of the mycobacterium tuberculosis cytochrome P450 CYP121. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51 9311–9316. 10.1002/anie.201202544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichihara O., Barker J., Law R. J., Whittaker M. (2011). Compound design by fragment-linking. Mol. Inform. 30 298–306. 10.1002/minf.201000174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemard C., Kellenberger E. (2019). A bright future for fragment-based drug discovery: what does it hold? Exp. Opin. Drug Discov. 14 413–416. 10.1080/17460441.2019.1583643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhoti H., Williams G., Rees D. C., Murray C. W. (2013). The ‘rule of three’ for fragment-based drug discovery: where are we now? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12 644–644. 10.1038/nrd3926-c1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang C. B. (2019a). Applications of in-cell NMR in structural biology and drug discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:139. 10.3390/ijms20010139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang C. B. (2019b). 19F-NMR in target-based drug discovery. Curr. Med. Chem. 26 4964–4983. 10.2174/0929867326666190610160534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano Y., Gebregiworgis T., Marshall C. B., Radulovich N., Poon B. P. K., St-Germain J., et al. (2019). Tyrosyl phosphorylation of KRAS stalls GTPase cycle via alteration of switch I and II conformation. Nat. Commun. 10:224. 10.1038/s41467-018-08115-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler D., Gmachl M., Mantoulidis A., Martin L. J., Zoephel A., Mayer M., et al. (2019). Drugging an undruggable pocket on KRAS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116 15823–15829. 10.1073/pnas.1904529116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd S. L., Osberger T. J., Mateu N., Sore H. F., Spring D. R. (2018). Recent applications of diversity-oriented synthesis toward novel, 3-dimensional fragment collections. Front. Chem. 6:460. 10.3389/fchem.2018.00460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch P., Jakob V., Oberhausen K., Stein S. C., Cucarro I., Schulz T. F., et al. (2019). Fragment-based discovery of a qualified hit targeting the latency-associated nuclear antigen of the oncogenic kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus/human herpesvirus 8. J. Med. Chem. 62 3924–3939. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinidou M., Magari F., Sutanto F., Haupenthal J., Jumde V. R., Ünver M. Y., et al. (2020). Rapid discovery of aspartyl protease inhibitors using an anchoring approach. ChemMedChem 15 680–684. 10.1002/cmdc.202000024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korczynska M., Le D. D., Younger N., Gregori-Puigjané E., Tumber A., Krojer T., et al. (2016). Docking and linking of fragments to discover jumonji histone demethylase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 59 1580–1598. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzyzosiak A., Sigurdardottir A., Luh L., Carrara M., Das I., Schneider K., et al. (2018). Target-based discovery of an inhibitor of the regulatory phosphatase PPP1R15B. Cell 174 1216–1228.e1219. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski J., Baburajendran N., Poulsen A., Liu B., Tee D. H. Y., Wong Y. X., et al. (2019). Fragment-based discovery of a small-molecule protein kinase c-iota inhibitor binding post-kinase domain residues. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 10 318–323. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski J., Liu B., Tee D. H. Y., Chen G., Ahmad N. H. B., Wong Y. X., et al. (2018). Fragment-based drug discovery of potent protein kinase C iota inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 61 4386–4396. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamberth C. (2018). Agrochemical lead optimization by scaffold hopping. Pest Manag. Sci. 74 282–292. 10.1002/ps.4755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamoree B., Hubbard R. E. (2017). Current perspectives in fragment-based lead discovery (FBLD). Essays Biochem. 61 453–464. 10.1042/ebc20170028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laraia L., McKenzie G., Spring D. R., Venkitaraman A. R., Huggins D. J. (2015). Overcoming chemical, biological, and computational challenges in the development of inhibitors targeting protein-protein interactions. Chem. Biol. 22 689–703. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Meng L., Zhou S., Deng X., Wang N., Ji Y., et al. (2019). Rapid generation of novel benzoic acid–based xanthine derivatives as highly potent, selective and long acting DPP-4 inhibitors: scaffold-hopping and prodrug study. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 180 509–523. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.07.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Kang C. (2017). Solution NMR spectroscopy in target-based drug discovery. Molecules 22:1399. 10.3390/molecules22091399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Liu S., Ng E. Y., Li R., Poulsen A., Hill J., et al. (2018a). Structural and ligand-binding analysis of the YAP-binding domain of transcription factor TEAD4. Biochem. J. 475 2043–2055. 10.1042/BCJ20180225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhang Z., Phoo W. W., Loh Y. R., Li R., Yang H. Y., et al. (2018b). Structural insights into the inhibition of zika virus NS2B-NS3 protease by a small-molecule inhibitor. Structure 26 555–564.e553. 10.1016/j.str.2018.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Phoo W. W., Loh Y. R., Zhang Z., Ng E. Y., Wang W., et al. (2017a). Structural characterization of the linked NS2B-NS3 protease of Zika virus. FEBS Lett. 591 2338–2347. 10.1002/1873-3468.12741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhang Z., Phoo W. W., Loh Y. R., Wang W., Liu S., et al. (2017b). Structural dynamics of zika virus NS2B-NS3 protease binding to dipeptide inhibitors. Structure 25 1242–1250.e1243. 10.1016/j.str.2017.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingel A., Vulpetti A., Reinsperger T., Proudfoot A., Denay R., Frommlet A., et al. (2020). Comprehensive and high-throughput exploration of chemical space using broadband 19F NMR-based screening. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 10.1002/anie.202002463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., Qian Y., Altieri M., Dong H., Wang J., Raina K., et al. (2015). Hijacking the E3 ubiquitin ligase cereblon to efficiently target BRD4. Chem. Biol. 22 755–763. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macalino S. J. Y., Basith S., Clavio N. A. B., Chang H., Kang S., Choi S. (2018). Evolution of in silico strategies for protein-protein interaction drug discovery. Molecules 23:963. 10.3390/molecules23081963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machiraju P. K., Yedla P., Gubbala S. P., Bohari T., Abdul J. K. V., Xu S., et al. (2019). Identification, synthesis and evaluation of CSF1R inhibitors using fragment based drug design. Comput. Biol. Chem. 80 374–383. 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2019.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzenrieder F., Frank A. O., Kessler H. (2008). Phosphorus NMR spectroscopy as a versatile tool for compound library screening. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47 2608–2611. 10.1002/anie.200705256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M., Meyer B. (1999). Characterization of ligand binding by saturation transfer difference NMR spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 38 1784–1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne K., Sun J., Zaal E. A., Mowat J., Celie P. H. N., Fish A., et al. (2019). A fragment-like approach to PYCR1 inhibition. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. Lett. 29 2626–2631. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.07.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake Y., Itoh Y., Hatanaka A., Suzuma Y., Suzuki M., Kodama H., et al. (2019). Identification of novel lysine demethylase 5-selective inhibitors by inhibitor-based fragment merging strategy. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 27 1119–1129. 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal M., Radeva N., Fanlo-Virgós H., Otto S., Klebe G., Hirsch A. K. H. (2016). Fragment Linking and optimization of inhibitors of the aspartic protease endothiapepsin: fragment-based drug design facilitated by dynamic combinatorial chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55 9422–9426. 10.1002/anie.201603074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munawar A., Beelen S., Munawar A., Lescrinier E., Strelkov S. V. (2018). Discovery of novel druggable sites on zika virus NS3 helicase using x-ray crystallography-based fragment screening. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:3664. 10.3390/ijms19113664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munzker L., Petrick J., Schleberger C., Clavel D., Cornaciu I., Wilcken R., et al. (2020). Fragment-based discovery of non-bisphosphonate binders of Trypanosoma brucei farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase. Chembiochem 10.1002/cbic.202000246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C. W., Newell D. R., Angibaud P. (2019). A successful collaboration between academia, biotech and pharma led to discovery of erdafitinib, a selective FGFR inhibitor recently approved by the FDA. MedChemComm 10 1509–1511. 10.1039/C9MD90044F [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J. B., Davidson J., Chen I., Davis B., Dokurno P., Graham C. J., et al. (2019). Establishing drug discovery and identification of hit series for the anti-apoptotic proteins, Bcl-2 and Mcl-1. ACS Omega 4 8892–8906. 10.1021/acsomega.9b00611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C. W., Rees D. C. (2009). The rise of fragment-based drug discovery. Nat. Chem. 1 187–192. 10.1038/nchem.217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J. B., Roughley S. D., Matassova N., Brough P. A. (2014). Off-rate screening (ORS) by surface plasmon resonance. an efficient method to kinetically sample hit to lead chemical space from unpurified reaction products. J. Med. Chem. 57 2845–2850. 10.1021/jm401848a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navratilova I., Hopkins A. L. (2010). Fragment screening by surface plasmon resonance. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 1 44–48. 10.1021/ml900002k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niesen F. H., Berglund H., Vedadi M. (2007). The use of differential scanning fluorimetry to detect ligand interactions that promote protein stability. Nat. Protoc. 2:2212. 10.1038/nprot.2007.321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton R. S, Leung E. W, Chandrashekaran I. R, MacRaild C. A. (2016). Applications of 19F-NMR in fragment-based drug discovery. Molecules 21:860. 10.3390/molecules21070860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens J. (2007). Determining druggability. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6 187–187. 10.1038/nrd2275 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patrone J. D., Kennedy J. P., Frank A. O., Feldkamp M. D., Vangamudi B., Pelz N. F., et al. (2013). Discovery of protein–protein interaction inhibitors of replication protein a. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 4 601–605. 10.1021/ml400032y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson E. I., Nanson J. D., Abendroth J., Bryan C., Sankaran B., Myler P. J., et al. (2020). Structural characterization of β-ketoacyl ACP synthase I bound to platencin and fragment screening molecules at two substrate binding sites. Proteins 88:47. 10.1002/prot.25765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedro L., Quinn R. J. (2016). Native mass spectrometry in fragment-based drug discovery. Molecules 21:984. 10.3390/molecules21080984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez C., Barkley-Levenson A. M., Dick B. L., Glatt P. F., Martinez Y., Siegel D., et al. (2019). Metal-Binding pharmacophore library yields the discovery of a glyoxalase 1 inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 62 1609–1625. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry E., Mills J. J., Zhao B., Wang F., Sun Q., Christov P. P., et al. (2019). Fragment-based screening of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 29 786–790. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.01.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petros A. M., Dinges J., Augeri D. J., Baumeister S. A., Betebenner D. A., Bures M. G., et al. (2006). Discovery of a potent inhibitor of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-xL from NMR and parallel synthesis. J. Med. Chem. 49 656–663. 10.1021/jm0507532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson M., Crews C. M. (2019). PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs) — Past, present and future. Drug Discov. Today 31 15–27. 10.1016/j.ddtec.2019.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevet H., Moune M., Tanina A., Kemmer C., Herledan A., Frita R., et al. (2019). A fragment-based approach towards the discovery of N-substituted tropinones as inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis transcriptional regulator EthR2. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 167 426–438. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot A., Bussiere D. E., Lingel A. (2017). High-confidence protein–ligand complex modeling by nmr-guided docking enables early hit optimization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139 17824–17833. 10.1021/jacs.7b07171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccio F., Talapatra S. K., Oxenford S., Angell R., Mazzon M., Kozielski F. (2019). Development and validation of RdRp Screen, a crystallization screen for viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases. Biol. Open 8:bio037663. 10.1242/bio.037663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbah M., Mendes V., Vistal R. G., Dias D. M. G., Záhorszká M., Mikušová K., et al. (2020). Fragment-based design of mycobacterium tuberculosis InhA inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 63 4749–4761. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salah E., Ugochukwu E., Barr A. J., von Delft F., Knapp S., Elkins J. M. (2011). Crystal Structures of ABL-related gene (ABL2) in complex with imatinib, tozasertib (VX-680), and a type i inhibitor of the triazole carbothioamide class. J. Med. Chem. 54 2359–2367. 10.1021/jm101506n [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiebel J., Krimmer, Stefan G., Röwer K., Knörlein A., Wang X., et al. (2016a). High-throughput crystallography: reliable and efficient identification of fragment hits. Structure 24 1398–1409. 10.1016/j.str.2016.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiebel J., Radeva N., Krimmer S. G., Wang X., Stieler M., Ehrmann F. R., et al. (2016b). Six biophysical screening methods miss a large proportion of crystallographically discovered fragment hits: a case study. ACS Chem. Biol. 11 1693–1701. 10.1021/acschembio.5b01034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schöne T., Grimm L. L., Sakai N., Zhang L., Hilgenfeld R., Peters T. (2017). STD-NMR experiments identify a structural motif with novel second-site activity against West Nile virus NS2B-NS3 protease. Antiv. Res. 146 174–183. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze J., Baukmann H., Wawrzinek R., Fuchsberger F. F., Specker E., Aretz J., et al. (2018). CellFy: a cell-based fragment screen against C-Type lectins. ACS Chem. Biol. 13 3229–3235. 10.1021/acschembio.8b00875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott D. E., Coyne A. G., Hudson S. A., Abell C. (2012). Fragment-based approaches in drug discovery and chemical biology. Biochemistry 51 4990–5003. 10.1021/bi3005126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuker S. B., Hajduk P. J., Meadows R. P., Fesik S. W. (1996). Discovering high-affinity ligands for proteins: SAR by NMR. Science 274 1531–1534. 10.1126/science.274.5292.1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si Y., Xu D., Bum-Erdene K., Ghozayel M. K., Yang B., Clemons P. A., et al. (2019). Chemical space overlap with critical protein–protein interface residues in commercial and specialized small-molecule libraries. ChemMedChem 14 119–131. 10.1002/cmdc.201800537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijbesma E., Hallenbeck K. K., Leysen S., de Vink P. J., Skóra L., Jahnke W., et al. (2019). Site-directed fragment-based screening for the discovery of protein–protein interaction stabilizers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 3524–3531. 10.1021/jacs.8b11658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M., Tam B., Akabayov B. (2018). NMR-fragment based virtual screening: a brief overview. Molecules 23:233. 10.3390/molecules23020233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skora L., Jahnke W. (2017). 19F-NMR-based dual-site reporter assay for the discovery and distinction of catalytic and allosteric kinase inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 8 632–635. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer K., Flachsenberg F., Rarey M. (2019). NAOMInext–synthetically feasible fragment growing in a structure-based design context. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 163 747–762. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.11.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souers A. J., Leverson J. D., Boghaert E. R., Ackler S. L., Catron N. D., Chen J., et al. (2013). ABT-199, a potent and selective BCL-2 inhibitor, achieves antitumor activity while sparing platelets. Nat. Med. 19 202–208. 10.1038/nm.3048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamford A., Strickland C. (2013). Inhibitors of BACE for treating Alzheimer’s disease: a fragment-based drug discovery story. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 17 320–328. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiki T., Furuita K., Fujiwara T., Kojima C. (2018). Current NMR techniques for structure-based drug discovery. Molecules 23:148. 10.3390/molecules23010148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szlávik Z., Ondi L., Csékei M., Paczal A., Szabó Z. B., Radics G., et al. (2019). Structure-guided discovery of a selective Mcl-1 inhibitor with cellular activity. J. Med. Chem. 62 6913–6924. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szõllõsi E., Bobok A., Kiss L., Vass M., Kurkó D., Kolok S., et al. (2015). Cell-based and virtual fragment screening for adrenergic α2C receptor agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 23 3991–3999. 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao W., Mian-Bin W., Zheng-Jie C., Hua C., Jian-Ping L., Li-Rong Y. (2015). Fragment-based drug discovery and molecular docking in drug design. Curr. Pharmaceut. Biotechnol. 16 11–25. 10.2174/1389201015666141122204532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple K. J., Engers J. L., Long M. F., Gregro A. R., Watson K. J., Chang S., et al. (2019). Discovery of a novel 3,4-dimethylcinnoline carboxamide M4 positive allosteric modulator (PAM) chemotype via scaffold hopping. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 29:126678. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.126678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S. E., Collins P., James R. H., Mendes V., Charoensutthivarakul S., Radoux C., et al. (2019). Structure-guided fragment-based drug discovery at the synchrotron: screening binding sites and correlations with hotspot mapping. Philos. Transact. R. Soc. A 377:20180422. 10.1098/rsta.2018.0422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J., Lee J. T., Wang W., Zhang J., Cho H., Mamo S., et al. (2008). Discovery of a selective inhibitor of oncogenic B-Raf kinase with potent antimelanoma activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 3041–3046. 10.1073/pnas.0711741105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull A. P, Boyd S. M, Walse B. (2014). Fragment-based drug discovery and protein-protein interactions. Res. Rep. Biochem. 4 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Vanwetswinkel S., Heetebrij R. J., van Duynhoven J., Hollander J. G., Filippov D. V., Hajduk P. J., et al. (2005). TINS, target immobilized NMR screening: an efficient and sensitive method for ligand discovery. Chem. Biol. 12 207–216. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viegas A., Manso J., Nobrega F. L., Cabrita E. J. (2011). Saturation-transfer difference (STD) NMR: a simple and fast method for ligand screening and characterization of protein binding. J. Chem. Educat. 88 990–994. 10.1021/ed101169t [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Welsch M. E., Kaplan A., Chambers J. M., Stokes M. E., Bos P. H., Zask A., et al. (2017). Multivalent small-molecule pan-RAS inhibitors. Cell 168 878–889.e829. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker M., Law R. J., Ichihara O., Hesterkamp T., Hallett D. (2010). Fragments: past, present and future. Drug Discov. Today 7 e163–e171. 10.1016/j.ddtec.2010.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson M. P. (2013). Using chemical shift perturbation to characterise ligand binding. Prog. Nuclear Magnet. Res. Spectr. 73 1–16. 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss D. F., Wang Y.-S., Eaton H. L., Strickland C., Voigt J. H., Zhu Z., et al. (2012). “Combining NMR and X-ray crystallography in fragment-based drug discovery: discovery of highly potent and selective BACE-1 inhibitors,” in Fragment-Based Drug Discovery and X-Ray Crystallography, eds Davies T. G., Hyvönen M. (Berlin: Springer; ), 83–114. 10.1007/128_2011_183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Ibrahim P. N., Zhang J., Burton E. A., Habets G., Zhang Y., et al. (2013). Design and pharmacology of a highly specific dual FMS and KIT kinase inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 5689–5694. 10.1073/pnas.1219457110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P., Jia L., Tian Y., Xi L., Duan R., Chen X., et al. (2020). Discovery of potential Toxoplasma gondii CDPK1 inhibitors with new scaffolds based on the combination of QSAR and scaffold-hopping method with in-vitro validation. Chem. Biol. Drug Design 95 476–484. 10.1111/cbdd.13603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Zhang M., Wang Y., Fan Y., Chen X., Yang Y., et al. (2019). Protein–ligand interaction-guided discovery of novel VEGFR-2 inhibitors. J. Biomol. Struct. Dynam. 19 1–16. 10.1080/07391102.2019.1635915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong W., Koay A., Ngo A., Li Y., Nah Q., Wong Y. H., et al. (2019). Targeting the bacterial epitranscriptome for antibiotic development: discovery of novel tRNA-(N(1)G37) methyltransferase (TrmD) inhibitors. ACS Infect Dis. 5 326–335. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.8b00275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoete V., Grosdidier A., Michielin O. (2009). Docking, virtual high throughput screening and in silico fragment-based drug design. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 13 238–248. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00665.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]