Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a Th2‐associated fibroinflammatory autoimmune disease, in which B cells are suggested to exert antibody‐independent functions. We found that CD30+GM‐CSF‐producing B cells (GM‐Beffs) were generated from memory B cells by Th2 cytokines along with TGF‐β and induced differentiation to monocyte‐derived dendritic cells. CD30+GM‐Beffs were increased in SSc patients with the diffuse type and concomitant ILD, suggesting their pivotal role in disease pathogenesis.

Keywords: GM‐CSF, Th subsets, B cells, CD30, systemic sclerosis

Summary

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a T helper type 2 (Th2)‐associated autoimmune disease characterized by vasculopathy and fibrosis. Efficacy of B cell depletion therapy underscores antibody‐independent functions of B cells in SSc. A recent study showed that the Th2 cytokine interleukin (IL)‐4 induces granulocyte–macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (GM‐CSF)‐producing effector B cells (GM‐Beffs) in humans. In this study, we sought to elucidate the generation mechanism of GM‐Beffs and also determine a role of this subset in SSc. Among Th‐associated cytokines, IL‐4 most significantly facilitated the generation of GM‐Beffs within memory B cells in healthy controls (HCs). In addition, the profibrotic cytokine transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β further potentiated IL‐4‐ and IL‐13‐induced GM‐Beffs. Of note, tofacitinib, a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, inhibited the expression of GM‐CSF mRNA and protein in memory B cells induced by IL‐4, but not by TGF‐β. GM‐Beffs were enriched within CD20+CD30+CD38−/low cells, a distinct population from plasmablasts, suggesting that GM‐Beffs exert antibody‐independent functions. GM‐Beffs were also enriched in a CD30+ fraction of freshly isolated B cells. GM‐Beffs generated under Th2 conditions facilitated the differentiation from CD14+ monocytes to DC‐SIGN+CD1a+CD14−CD86+ cells, which significantly promoted the proliferation of naive T cells. CD30+ GM‐Beffs were more pronounced in patients with SSc than in HCs. A subpopulation of SSc patients with the diffuse type and concomitant interstitial lung disease exhibited high numbers of GM‐Beffs. Together, these findings suggest that human GM‐Beffs are enriched in a CD30+ B cell subset and play a role in the pathogenesis of SSc.

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is an intractable autoimmune disease (AID) characterized by vasculopathy, fibrosis and immune dysregulation [1]. Although the pathogenesis of SSc remains still largely uncharacterized, genomewide association studies showed that a set of immune‐related genes is closely associated with this disease [2, 3]. T helper type 2 (Th2) cytokines such as interleukin (IL)‐4 and IL‐13 exert profibrotic functions [4]; however, an impact of these cytokines on immune cells in SSc remains somewhat elusive. Due to the debilitating nature of the disease, there are still high unmet needs for novel therapeutic strategies.

The efficacy of B cell‐targeting agents such as anti‐CD20 in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and SSc highlights a pathogenic role of B cells in AIDs [5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. Notably, correlation is not always found between autoantibody titers and clinical symptoms, thus underscoring antibody‐independent functions, particularly cytokine production, of B cells [5, 10]. Cytokine‐producing B cells are functionally divided into two subsets, effector B cells (Beffs) and regulatory B cells (Bregs). In patients with RA, Bregs are less abundant and their suppressive function is impaired [11, 12]. We showed that synovial fluid of patients with RA includes abundant receptor activator of nuclear factor κB (NF‐κB) ligand (RANKL)‐producing Beffs capable of inducing osteoclast differentiation [13]. In patients with SSc, although IL‐6‐producing Beffs are increased and Bregs are functionally defective [10, 14, 15], it remains to be elucidated whether other cytokine‐producing Beffs are also involved [1].

Granulocyte–macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (GM‐CSF) was originally recognized as a hematopoietic growth factor that can induce proliferation and differentiation of granulocytes and macrophages. However, GM‐CSF also exerts proinflammatory functions and plays critical roles in AIDs [16]. For instance, GM‐CSF is involved in the differentiation of monocytes to myofibroblasts and macrophages that harbor the potential to promote fibrosis in the pathogenesis of SSc [17, 18]. It is well known that GM‐CSF is abundantly produced by monocyte/macrophages and dendritic cells. Notably, T cells have recently drawn attention as another source of GM‐CSF. GM‐CSF‐producing CD4+ T cells are involved in inflammatory mouse models such as experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), collagen‐induced arthritis (CIA) and interstitial lung disease in SKG mice [19, 20, 21, 22]. Similarly, in humans, the significance of GM‐CSF‐producing CD4+ T cells is implicated in RA and multiple sclerosis (MS) [23, 24].

A recent study showed that GM‐CSF‐producing B cells (GM‐Beffs) abundantly exist in patients with MS and IL‐4 appears to be a potent inducer of GM‐Beffs [25]. However, the generation mechanisms and the specific markers of GM‐Beffs remain somewhat elusive. In addition, given that Th2 cytokines are associated with SSc [4], it is of great interest to determine whether GM‐Beffs are involved in the pathogenesis of this disease.

In this study, we sought to demonstrate how GM‐Beffs are induced by Th‐associated cytokines, and to clarify what surface marker enriches for GM‐Beffs in humans. In addition, we aimed to demonstrate whether GM‐Beffs really exist and their functional roles in SSc.

Materials and methods

SSc patients and controls

We studied 44 Japanese patients with SSc who were treated at the Kyushu University hospital and 16 healthy controls (HCs). We included the patients who fulfilled the 1980 classification criteria of the American College of Rheumatology for SSc. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Board of Kyushu University Hospital approved all research on human subjects (no. 29‐544). We obtained information from the medical records of the patients, including demographic data, clinical manifestations, laboratory findings and medications. Patients with SSc were classified as having limited cutaneous or diffuse cutaneous disease according, to the criteria of LeRoy et al. [26]. The existence of SSc‐related interstitial lung disease (ILD) was based on chest high‐resolution computed tomography (HRCT).

Reagents

An affiniPure F (ab′)2 fragment goat anti‐human immunoglobulin (Ig)A/IgG/IgM (H+L) (anti‐BCR, 10 μg/ml) was purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA, USA). Recombinant human CD40 ligand (CD40L; 100 ng/ml) was from Biolegend (San Diego, CA, USA). Recombinant human cytokines [IFN‐γ (20 ng/ml), IL‐4 (20 ng/ml), IL‐17 (100 ng/ml), IL‐13 (20 ng/ml), IL‐6 (50 ng/ml), IL‐10 (10 ng/ml), IL‐15 (10 ng/ml), IL‐21 (50 ng/ml), transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β (50 ng/ml), recombinant human IL‐6 receptor (100 ng/ml)] and a fully human monoclonal antibody (mAb) against GM‐CSF (αGM‐CSF, 1 μg/ml) were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Tofacitinib (CP‐690550) was purchased from Selleckchem (Houston, TX, USA). Anti‐CD3 mAb (OKT3) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) and dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) was from Sigma‐Aldrich (S Louis, MO, USA)

Isolation and cell sorting of B cell subsets

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained using density centrifugation with LSM (MP Biomedicals, LLC, Santa Ana, CA, USA). B cells were isolated by positive selection with CD19+ mAbs and a magnetic‐activated cell sorting (MACS) system (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Isolated B cells exhibited greater than 99·5% viability and more than 95% purity, confirmed by flow cytometry. Cells were stained with mouse or rabbit mAbs against human CD19, CD20, CD27, CD30, CD38, CD124 (IL‐4Ra) and CD183 [CXC chemokine receptor (CXCR)3] (all from BioLegend). Memory (CD19+CD27+) B cell subsets were purified by flow cytometry. Isolated memory B cells exhibited more than 99% purity (Supporting information, Fig. S1a).

Quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (qRT–PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from primary B cells using Isogen II reagent (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan). qPCR was performed using the ABI Prism 7500 Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). TaqMan target mixes for CSF2 (Hs00929873_m1), TNF (Hs00174128_m1), TNFRSF11 (Hs00243533_m1), PRDM1 (Hs00153357_m1) and IL6 (Hs00174131_m1) were all purchased from Applied Biosystems. A 18S ribosomal RNA was separately amplified in the same plate as an internal control for variation in the amount of cDNA in PCR. The collected data were analyzed using Sequence Detector software (Applied Biosystems). Data were expressed as the fold change in gene expression relative to the expression in control cells.

Intracellular staining of GM‐CSF

Phorbol 12‐myristate 13‐acetate (PMA, 50 ng/ml; Calbiochem, Nottingham, UK), ionomycin (1 μM; Calbiochem) and Golgi Stop (Brefeldin‐A; eBioscience, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were added 4 h before staining. Cell surface staining was performed before intracellular cytokine staining. After washing two times, fixation/permeabilization buffer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) was added to fix the cells. Antibody to detect GM‐CSF (BD Biosciences) was added to the cell suspension and cells were analyzed by FACS Aria III (BD Biosciences).

Enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Sorted memory B cells were stimulated for 48 h with Th‐associated cytokines in the presence of anti‐BCR and CD40L and supernatants were collected afterwards. The concentration of supernatants was measured by using Quantikine ELISA kits (R&D Systems), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Co‐culture experiments

Purified memory B cells were prestimulated with IL‐4 and TGF‐β in the presence of anti‐BCR and CD40L for 48 h, washed thoroughly and co‐cultured with CD14+ monocytes for 72 h with anti‐BCR and IL‐4. CD14+ monocytes were cultured in a 12‐well plate at a ratio of 1 : 10 monocytes: B cells (2× 105 monocytes: 2 × 106 B cells/ml). Cells were harvested and the expression of surface markers including CD1a, CD1c, CD14 and CD86 in DC‐SIGN+CD19− cells was analyzed by flow cytometry.

T cell proliferation assay

Naive CD4+ T cells were labeled with cell trace yellow (CTY) using cell trace yellow cell proliferation kits, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific), then cultured alone or co‐cultured with sorted DC‐SIGN+CD19− cells differentiated from CD14+ monocytes in the manner described above for 5 days with OKT3 (1 μg/ml) and IL‐2 (100 U/ml). DC‐SIGN+CD19− cells were cultured in a 96‐well plate at a ratio of 1 : 2 DC‐SIGN+CD19− cells: naive CD4+ T cells (1 × 105 DC‐SIGN+CD19− cells: 2 × 105 naive CD4+ T cells/ml). Cells were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

Numerical data in the in‐vitro experiments were presented as mean of the different experiments and standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Multiple group comparisons were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test. The significance of the differences was determined by Student’s t‐test for comparing differences between two groups. Numerical data in patient‐sample analyses were presented as mean, and the significant differences (s.d.) were determined by Student’s t‐test or non‐parametric Mann–Whitney U‐test according to distributions. For all tests, P‐values less than 0·05 were considered significant. All analyses were performed using jmp statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

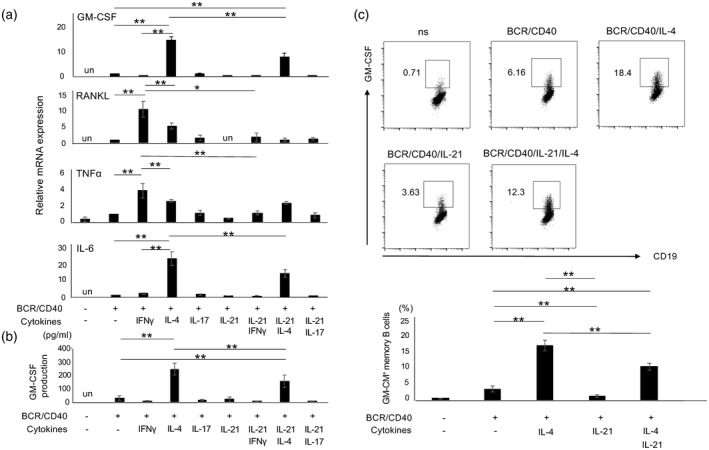

GM‐Beffs are induced under Th2 and, to a lesser extent, Tfh2 conditions

We first sought to determine how GM‐Beffs are induced in‐vitro. Given that Th–B cell interaction plays a critical role in cytokine production by B cells, identification of a major Th cell subset responsible for generation of GM‐Beffs was of great interest. As GM‐CSF production is much higher in CD19+CD27+ memory B cells than in CD19+CD27‐ B cells [25], we used memory B cells in this study. Purified human memory B cells were cultured with cytokines, including Th1 cytokine IFN‐γ (20 ng/ml), Th2 cytokine IL‐4 (20 ng/ml), Th17 cytokine IL‐17 (100 ng/ml) and the T follicular helper (Tfh) cytokine IL‐21 (50 ng/ml), in a combination of anti‐BCR (10 μg/ml) and CD40L (1 μg/ml). GM‐CSF mRNA was remarkably up‐regulated with IL‐4, but not IFN‐γ or IL‐17, in memory B cells (Fig. 1a, upper panel). IL‐4 exerted such an effect upon BCR/CD40 stimulation because IL‐4R was remarkably induced only in stimulated B cells (Supporting information, Fig. S1b). The concentration of IL‐4 in serum is within the range of 1–10 pg/ml in patients with SSc [27, 28], although may be much higher in tissues. The levels of GM‐CSF mRNA were significantly up‐regulated by IL‐4 in a dose‐dependent manner (Supporting information, Fig. S2a). Of note, IL‐6 mRNA was also significantly up‐regulated with IL‐4 (Fig. 1a, bottom panel). In contrast, as we have previously reported [13], RANKL and TNF‐α mRNAs were up‐regulated most with IFN‐γ (Fig. 1a, middle two panels). Intriguingly, IL‐21, involved in plasma cell differentiation [29], suppressed the generation of these cytokine‐producing B cells, including GM‐Beffs (Fig. 1a). Consistent with transcript data, stimulation with IL‐4‐induced high levels of GM‐CSF proteins in memory B cells (Fig. 1b,c). Circulating T follicular helper type 2 (Tfh2) cells produce IL‐4 as well as IL‐21 [30, 31]. GM‐Beffs were thus induced, to some extent, under Tfh2 conditions. These results suggest that GM‐Beffs are induced under Th2 and, to a lesser extent, Tfh2 conditions.

Fig. 1.

Cytokine expression by human memory B cells under T cell‐dependent conditions. (a) Purified human memory B cells (CD19+CD27+ cells) stimulated with several cytokines including, interferon (IFN)‐γ, interleukin (IL‐4), IL‐17 and IL‐21 in combination with anti‐B cell receptor (BCR) and CD40L were cultured for 24 h. Cells were harvested, then the transcriptions of several cytokines including granulocyte–macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (GM‐CSF), RANKL, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α and IL‐6 were evaluated by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). (b) Memory B cells stimulated under the same conditions as (a) were cultured for 48 h, then culture supernatants were collected, tested for GM‐CSF by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (n = 3). (c) The top panel depicts representative GM‐CSF expression in memory B cells stimulated under designated conditions for 48 h [phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin were added for the last 4 h] and the bottom panel summarizes the results (n = 4). *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, un: undetected; n.s. = no stimulation.

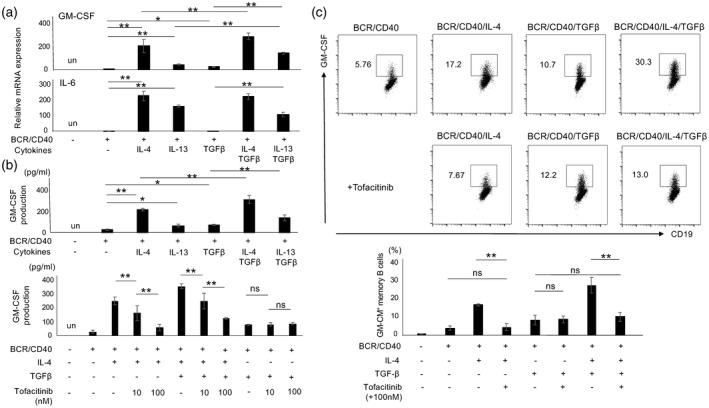

TGF‐β enhances IL‐4‐ and IL‐13‐mediated GM‐Beff induction

GM‐Beffs were induced under Th2 conditions (Fig. 1); however, we further sought to identify optimal conditions of GM‐Beffs induction. In addition to IL‐4, IL‐13 (20 ng/ml), another Th2 cytokine [31], and the profibrotic cytokine TGF‐β (50 ng/ml) were added to the culture. TGF‐β increased BCR/CD40‐induced GM‐CSF mRNA but not IL‐6 mRNA (Fig. 2a). IL‐13, a cytokine capable of activating the type II IL‐4R, up‐regulated GM‐CSF and IL‐6 mRNAs (Fig. 2a). The concentration of IL‐13 and TGF‐β in serum is within a range of 1–5 ng/ml and 10–50 ng/ml in patients with SSc [27, 28], although it may be much higher in tissues. The levels of GM‐CSF mRNA were significantly up‐regulated by IL‐13 and TGF‐β in a dose‐dependent manner (Supporting information, Fig. S2b,c). Consistent with transcript data, TGF‐β enhanced IL‐4‐ and IL‐13‐mediated GM‐CSF protein production in memory B cells (Fig. 2b). Janus kinase (JAK) is a pivotal signaling molecule of IL‐4 and IL‐13 [32]. Tofacitinib, a JAK inhibitor, inhibited the expression of GM‐CSF mRNA and protein in memory B cells induced by IL‐4, but not by TGF‐β (Fig. 2b, lower panel, Fig. 2c). Tofacitinib did not affect the viability of stimulated B cells (data not shown). These results suggest that GM‐Beffs are most efficiently induced under Th2 conditions together with TGF‐β and this process is partially abrogated by JAK inhibition.

Fig. 2.

Granulocyte–macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (GM‐CSF)‐producing effector B cells (GM‐Beffs) are most efficiently induced under T helper type 2 (Th2) conditions with transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β. (a) Purified memory B cells stimulated with several cytokines including interleukin (IL)‐4, IL‐13 and TGF‐β in combination with anti‐B cell receptor (BCR) and CD40L were cultured for 24 h. Cells were harvested, then the transcriptions of GM‐CSF and IL‐6 were evaluated by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). (b) Stimulated memory B cells were cultured for 48 h, then culture supernatants were collected, tested for GM‐CSF by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (top panel). In addition, tofacitinib or vehicle control [0·1% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)] was added and culture supernatants were tested for GM‐CSF by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (bottom panel). (c) The top panel depicts representative GM‐CSF expression in memory B cells stimulated under designated conditions for 48 h [phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin were added for the last 4 h] and the bottom panel summarizes the results (n = 4). *P < 0·05, **P < 0.01; un = undetected, n.s. = non‐significant.

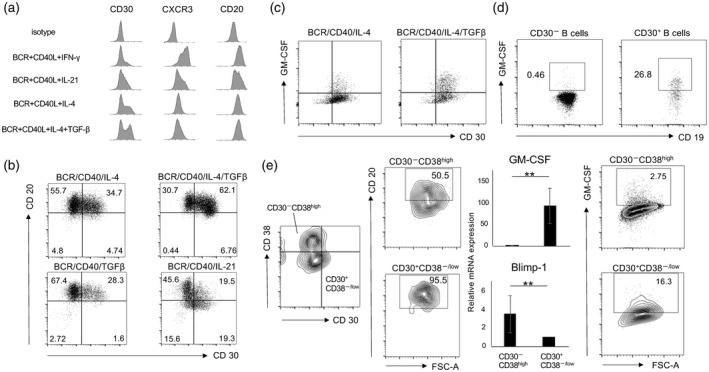

GM‐Beffs are enriched within CD20+CD30+CD38−/low cells, a distinct population from plasmablast (PB)

To enrich human GM‐Beffs prospectively, we next focused on CD30, previously described as a Th2‐specific marker [33, 34]. We checked CXCR3, CD20 and CD30 expressions on human memory B cells cultured with several cytokines, including IFN‐γ, IL‐4, IL‐21 and TGF‐β, together with anti‐BCR and CD40L, for 4 days (Fig. 3a). CD30 expression was up‐regulated most with IL‐4 in combination with TGF‐β, whereas CXCR3 expression was up‐regulated most with IFN‐γ and CD20 expression was down‐regulated most with IL‐21 (Fig. 3a). Notably, IL‐4 in combination with TGF‐β was most potent for the generation of CD20+CD30+ B cells (Fig. 3b). To test whether GM‐CSF production is derived from CD30+ B cells induced by IL‐4 and TGF‐β, we co‐stained CD30 and GM‐CSF on memory B cells. GM‐CSF expression was mainly confined to CD30+ B cells (Fig. 3c). We also tested whether the same is true in freshly isolated B cells. GM‐Beffs were again enriched in CD30+ B cells in this condition (Fig. 3d). Acquisition of CD30 can distinguish activated B cells from the pre‐PB stage and loss of CD30, together with strong expression of CD38, characterizes PB stage [35]. Given that IL‐21 suppressed the induction of GM‐Beffs (Fig. 1), we hypothesized that GM‐Beffs were distinct cellular populations from PB. To test this, we induced the differentiation of human memory B cells into PB using a combination of anti‐BCR, CD40L, IL‐21, IL‐15 (10 ng/ml) and IL‐6 (50 ng/ml) for 6 days. IL‐10 (50 ng/ml) and IL‐4 were added for the last 24 h. Representative flow cytometry plots of CD30 and CD38 are shown (Fig. 3e, left panel). As expected, CD30‐CD38high B cells down‐regulated CD20 expression, whereas CD30+CD38−/low B cells retained its expression (Fig. 3e, second from left panel). In addition, GM‐CSF mRNA in CD30+CD38−/low cells was more significantly up‐regulated than that in CD30−CD38high cells (Fig. 3e, second from right panel). The same was true at the protein level (Fig. 3, right panel). Conversely, Blimp‐1 mRNA in CD30‐CD38high cells was more significantly up‐regulated than that in CD30+CD38−/low cells (Fig. 3e, second from right panel). These results strongly suggest that GM‐Beffs are enriched in CD20+CD30+CD38−/low cells, which are distinct from cells of the PB stage.

Fig. 3.

Granulocyte–macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (GM‐CSF)‐producing effector B cells (GM‐Beffs) are enriched within CD30+ memory B cells. (a) The histogram panels show the expression of several surface molecules including CD20, CD30 and C‐X‐C motif chemokine receptor 3 (CXCR3) on memory B cells stimulated for 96 h. (b) These panels show expression of CD20 and CD30 on stimulated memory B cells with several cytokines including interleukin (IL)‐4, IL‐21 and transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β. (c) The panels show expression of CD30 and GM‐CSF. (d) The panels show GM‐CSF expression in freshly isolated CD30− and CD30+ B cells. (e) The left panel shows expressions of CD30 and CD38 (CD30+CD38−/low and CD30−CD38+ gates surrounded by heavy lines). The second from left panel shows the expression level of CD20+ cells. The second from right panel shows the transcription levels of GM‐CSF and B lymphocyte‐induced maturation protein‐1 (Blimp‐1) in CD30+CD38−/low and CD30−CD38+ cells. The right panel shows GM‐CSF production by flow cytometry. **P < 0·01.

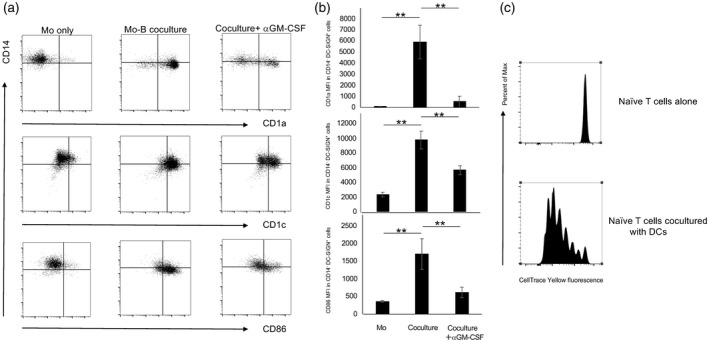

GM‐Beffs induce differentiation to monocyte‐derived dendritic cells (MoDCs)

Given that a combination of GM‐CSF and IL‐4 induces differentiation of monocytes to DCs [36], we reasoned that GM‐Beffs cause such differentiation. To test this, purified CD14+ monocytes from HCs were cultured alone or co‐cultured with memory B cells stimulated with anti‐BCR and IL‐4 for 3 days with subsequent analysis of surface markers, including CD1a, CD1c, CD14, CD86 and DC‐SIGN (DC‐specific intercellular adhesion molecule‐grabbing nonintegrin) [37], in CD19− cells by flow cytometry. Because CD14 is down‐regulated as monocytes differentiate into DCs, which express CD1, DC‐SIGN and co‐stimulatory molecules including CD86 [36, 37], we focused on the populations of CD14−CD1a+, CD14−CD1c+ and CD14−CD86+ cells among DC‐SIGN+CD19− cells. Intriguingly, GM‐Beffs significantly increased the populations of CD14‐CD1a+, CD14‐CD1c+ and CD14−CD86+ cells among DC‐SIGN+CD19‐ cells, and this process was significantly suppressed by anti‐GM‐CSF, indicating that GM‐Beffs significantly enhanced differentiation of CD14+ monocytes into DCs via GM‐CSF secretion (Fig. 4a,b). To further validate the function of GM‐Beff‐induced DCs, naive CD4+ T cells were cultured alone or co‐cultured with sorted DC‐SIGN+CD19− cells with anti‐CD3 mAb and IL‐2, then analyzed for their proliferation by flow cytometry. DC‐SIGN+ CD19− cells clearly promoted the proliferation of naive CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4c). These results suggest that GM‐Beffs have the potential to differentiate of CD14+ monocytes to functional DCs in vitro.

Fig. 4.

Differentiation to dendritic cells (DCs) from monocytes induced by granulocyte–macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (GM‐CSF)‐producing effector B cells (GM‐Beffs). Purified memory B cells were pre‐exposed with several cytokines including interleukin (IL)‐4 and transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β in concert with anti‐B cell receptor (BCR) and CD40L for 48 h, then were thoroughly washed and cultured in fresh medium with purified CD14+ monocytes from healthy controls (HCs) with BCR and IL‐4, added either anti‐GM‐CSF or isotype control, for an additional 72 h. After co‐culture, surface markers including CD1a, CD1c, CD86 and CD14 on DC‐SIGN+CD19− cells were assessed by flow cytometry. (a) The representative data are shown. (b) The bar charts summarize the results (n = 4). **P < 0·01. (c) Monocyte‐derived DCs promote the proliferation of naive CD4+ T cells. Purified memory B cells were pre‐exposed with IL‐4 and TGF‐β in concert with anti‐BCR and CD40L for 48 h, then thoroughly washed and cultured with CD14+ monocytes from HCs with anti‐BCR and IL‐4 for an additional 72 h, followed by sorting DC‐SIGN+CD19‐ cells. CTY‐labeled naive CD4+ T cells were cultured alone or co‐cultured with the above DC‐SIGN+CD19− cells with anti‐CD3 monoclonal antibody (mAb) and IL‐2 for 5 days, then cell proliferation of naive CD4+ T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. Histogram shows cell trace yellow (CTY) fluorescence of naive CD4+ T cells cultured alone (top panel) and co‐cultured with DC‐SIGN+CD19− cells (bottom panel).

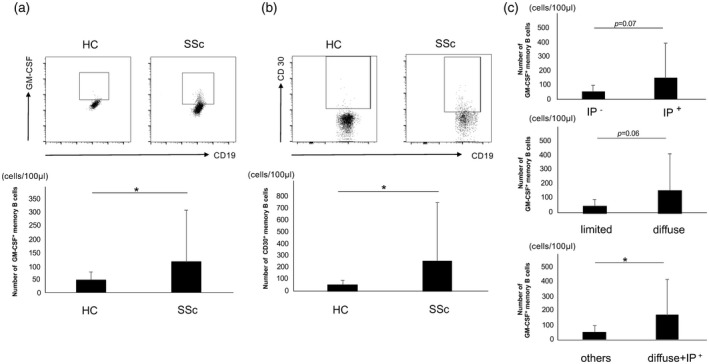

CD30+ GM‐Beffs increase in SSc patients, especially in subpopulations with the diffuse type and concomitant ILD

Given the pathological relevance of IL‐4 and TGF‐β in SSc [1, 4], we investigated the relevance of GM‐Beffs in patients with SSc. We thus evaluated GM‐CSF production from circulating B cells in patients with SSc and age‐ and sex‐matched HCs (all women; aged 57·9 ± 15·9 years) by flow cytometry. The clinical characteristics of SSc patients are shown in Supporting information, Table S1). The number of circulating GM‐Beffs was significantly increased in patients with SSc (114·6 ± 193·5 cells/100 μl, n = 44) compared with that in HCs (47·8 ± 28·8 cells/100 μl; n = 16, P = 0·043) (Fig. 5a). The number of CD30+ memory B cells in patients with SSc was also significantly increased compared with that in HCs (262·5 ± 495·0 cells/100 μl versus 58·6 ± 36·3 cells/100 μl, respectively, P = 0·042) (Fig. 5b). Moreover, the number of GM‐Beffs with diffuse type, limited type, with and without concomitant ILD were 164·2 ± 257·0, 54·0 ± 47·0, 150·6 ± 245·4 and 55·8 ± 44·3 cells/100 μl, respectively [P > 0·05 for diffuse type versus limited type; P > 0·05 for interstitial pneumonia (IP)+ versus IP−] (Fig. 5c). Intriguingly, the number of a subpopulation of SSc patients with the diffuse type and concomitant ILD was significantly increased compared to that of other patients except this characteristic (168·1 ± 248·0 versus 52·1 ± 45·3 cells/100 μl, P = 0·026) (Fig. 5c). As SSc patients with the diffuse type and concomitant ILD have a poor prognosis [38], these results suggest that GM‐Beffs are involved in the pathogenesis and severity of SSc.

Fig. 5.

CD30+ granulocyte–macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (GM‐CSF)‐producing effector B cells (GM‐Beffs) in HCs and patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc). (a) The top panels show the representative datum regarding GM‐CSF+ memory B cells from healthy controls (HCs) and patients with SSc. The bottom panel summarizes the results. (b) The top panels show the representative datum regarding CD30+ memory B cells from HCs and patients with SSc. The bottom panel summarizes the results. (c) These bar charts summarize the number of GM‐CSF+ memory B cells in each clinical feature of patients with SSc. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that GM‐Beffs were most efficiently induced under Th2 and, to a lesser extent, Tfh2 conditions. Generation of GM‐Beffs was synergistically accentuated by TGF‐β and conversely blocked by a JAK inhibitor. The phenotype of GM‐Beffs was CD20+CD30+CD38−/low cells and they co‐operated with IL‐4 to facilitate the differentiation from CD14+ monocyte to DC‐SIGN+CD1a+CD1c+CD14‐CD86+ DC‐like cells, which significantly promoted the proliferation of naive T cells. CD30+ GM‐Beffs were abundant in patients with SSc. A subpopulation of patients with the diffuse type and concomitant ILD, in particular, exhibited high levels of GM‐CSF production.

Th‐derived cytokines play a critical role in the generation of cytokine‐producing B cells. As we have shown previously [13], the Th1 cytokine IFN‐γ effectively generates RANKL‐producing Beffs, which are involved in the pathogenesis of RA. In SSc Th2 cytokines exert profibrotic functions [4]; however, their impact on cytokine‐producing Beffs has not thus far been addressed. In this study we clearly show that IL‐4 and IL‐13 generate a novel B cell subset (GM‐Beffs), which was increased in patients with SSc. It should be noted that romilkimab, a humanized bi‐specific IgG4 antibody that binds and neutralizes both IL‐4/IL‐13, was effective for diffuse cutaneous SSc in a Phase Ⅱa randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial (NCT02921971) [39]. This treatment thus would, in theory, selectively suppress the induction of GM‐Beffs.

Notably, we found that GM‐Beffs were also induced, to a lesser extent, under Tfh2 conditions (Fig. 1). Tfh cells, defined as CXCR5+CD4+T cells, mainly reside in the germinal center (GC) and produce IL‐21, that helps the generation of memory B cells and plasma cells [29]. Of note, humans have peripheral blood counterpart of Tfh cells and termed circulating Tfh (cTfh). cTfh cells can be further divided into three subsets by additional surface markers; namely, cTfh1, cTfh2, and cTfh17 [30]. Intriguingly, IL‐21 alone exerted a suppressive effect on the induction of GM‐Beffs (Fig. 1). IL‐4, however, partially abrogated IL‐21‐induced suppression of GM‐Beff induction (Fig. 1), underscoring a critical role of IL‐4 in the generation of GM‐Beffs. Recent studies have shown that Tfh cells not only induce plasma cell differentiation, but also are directly associated with skin fibrosis in SSc [40, 41]. Based on our current results that GM‐Beffs are generated by a mechanism distinct from plasma cell differentiation (Fig. 3e), Tfh‐induced GM‐Beffs might be also involved in skin fibrosis in SSc. Further work is needed to address this provocative issue.

CD30 is one of TNF receptor superfamily molecules and is expressed on activated lymphocytes [42]. It is preferentially expressed on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, which produce Th2 cytokines [43]. Indeed, CD30+ T cells are seen in several diseases, including atopic dermatitis and SSc, in which Th2 cytokines play a pathogenic role [33, 34]. In this study we clearly show that human memory B cells expressed CD30 in response to IL‐4, but not IFN‐γ or IL‐21 (Fig. 3a). This is in line with a recent paper showing that CD30 is a critical molecule downstream of the IL‐4–signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)‐6 pathway in mouse B cells [44]. In addition, TGF‐β, another profibrotic cytokine involved in the pathogenesis of SSc, synergistically accentuated the expression of CD30 (Fig. 3a). It should be noted that the clinical trial to assess the therapeutic efficacy of brentuximab vedotin, a CD30‐directed antibody–drug conjugate, in active diffuse cutaneous SSc is now ongoing (NCT03198689, NCT03222492). Thus, this treatment, in theory, would deplete preferentially GM‐Beffs as well as CD30+ T cells in patients with SSc. It is therefore of great interest to await the results in the future.

What, then, is the role of GM‐Beffs in the pathogenesis of SSc? Given that GM‐CSF and IL‐4 are critical cytokines for generation of inflammatory DC from monocytes [36], we hypothesized that GM‐Beffs induced under Th2 conditions promote this process in concert with IL‐4. As we expected, GM‐Beffs cooperated with IL‐4 to facilitate the differentiation of CD14+ monocytes into DC‐SIGN+CD1a+CD1c+CD14−CD86+ DCs (Fig. 4), a DC subset previously reported in skin of SSc patients and SSc model mice [45, 46, 47]. DCs play a role in the development of fibrosis in SSc by producing inflammatory cytokines including IL‐6 and TNF‐α. These cytokines then lead to the transformation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts that contribute to overproduction of extracellular matrix [48]. Aside from IL‐4, GM‐CSF alone induce the differentiation from CD14+ monocytes to CD1c+ DCs in patients with RA [21]. Similar situations might be also true in the case of SSc. In addition to their role in skin, B cells infiltrate in the pulmonary inflammatory lesions of SSc patients with ILD and B cell‐depleting therapy has a beneficial effect on pulmonary function, suggesting that B cells also contribute to the pathogenesis of SSc‐associated ILD [7, 8, 49]. Based on these observations, we reason that GM‐Beffs are involved in the pathogenesis of SSc by enhancing fibrosis through the induction of DCs.

Although clinical studies show the beneficial effect of rituximab, a mAb against human CD20, on skin sclerosis and pulmonary fibrosis of SSc, how B cells deteriorate the pathogenesis of SSc remains somewhat elusive [7, 8, 9]. Recent studies show that IL‐6/TGF‐β‐producing B cells play a role in the pathogenesis of SSc [10, 14, 15]. Notably, the frequency of activated B cells harboring the potential to produce IL‐6/TGF‐β is increased in the diffuse type SSc patients with concomitant ILD [10, 14]. Based on our current findings that Th2 conditions significantly induce IL‐6 as well as GM‐CSF (Figs. 1a, 2a), whether IL‐6/TGF‐β ‐producing Beffs and GM‐Beffs are identical or not needs to be further determined. Given that the clinical trial of IL‐6 blockade has provided promising results in patients with SSc [50], it is of great importance to address these issues.

Based on our findings above, it is suggested that GM‐Beffs play a role in the pathogenesis of SSc and they are an ideal target for the treatment of this disease. We show that tofacitinib, a JAK inhibitor, abrogated the generation of GM‐Beffs induced by IL‐4, which activates JAK‐1/3 (Fig. 2b,c). JAK‐STAT signature is noted in skin and ILD of patients with SSc [51], indicating the possibility that tofacitinib is an effective treatment for SSc. Indeed, the clinical trial to assess the therapeutic efficacy of tofacitinib in early diffuse cutaneous SSc (TOFA‐SSc) is now ongoing (NCT03274076). Tofacitinib, however, suppresses the signaling of several other cytokines, including IL‐2, IL‐7, IL‐15 and IL‐21, that are crucial for lymphocytes activation, proliferation and function [52]. Infectious diseases such as viral infection induced by tofacitinib have been reported [53]. The anti‐CD20 therapy non‐selectively depletes Bregs as well as pathogenic Beffs. There are thus still unmet needs for more selective targeting strategy for Beffs.

The number of CD20+ B cells is much lower than that of CD3+T cells and CD68+ macrophages in skin samples from patients with SSc [54]. However, all patients who experienced more than 20% worsening in the skin score have infiltration of CD20+ B cells in the skin biopsy specimens [54], suggesting that B cells play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis and development of SSc. Although the current study clearly demonstrates the generation mechanism and the existence of GM‐Beffs in human blood, the main limitations are the lack of evidence for this novel subset in the involved tissues. Together with sensitive methods, further studies with more SSc patients along with their tissue samples are required to clarify the role of GM‐Beffs in the pathogenesis of this devastating disease.

Disclosures

The authors declare no financial or commercial conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. (a) The purity of memory B cells isolated by flow cytometry. The left panel shows expression of CD19 and CD27 on B cells before sorting. The right panel shows expression of CD19 and CD27 on B cells after sorting. (b) The histogram of IL‐4R in resting and BCR/CD40‐stimulated B cells. Shadow: isotype control; Solid line: IL‐4R in BCR/CD40‐stimulated memory B cells; Dotted line: IL‐4R in resting memory B cells.

Fig. S2. Dose titration of IL‐4, IL‐13 and TGF‐β. Purified memory B cells stimulated with the designated dose of IL‐4 (a), IL‐13 (b), or TGF‐β (c) in combination with anti‐BCR and CD40L were cultured for 24 h. Cells were harvested, then, GM‐CSF mRNA was evaluated by qPCR. ** indicates P < 0.01, un: undetected.

Table S1. Baseline characteristics.

Acknowledgements

K. H. performed the experiments, statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. Y. K., M. A., Y. K., H. M., M. K., M. A., Y. A., T. H., K. A. and H. N. designed the study and helped to draft the manuscript. Y. K. and H. N. contributed to data analysis and interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. This work was supported in part by a Grant‐in‐Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan (HN: grant number 18K08410).

References

- 1. Katsumoto TR, Whitfield ML, Connolly MK. The pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Annu Rev Pathol 2011; 6:509–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Terao C, Kawaguchi T, Dieude P et al Transethnic meta‐analysis identifies GSDMA and PRDM1 as susceptibility genes to systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76:1150–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bossini‐Castillo L, López‐Isac E, Martín J. Immunogenetics of systemic sclerosis: defining heritability, functional variants and shared‐autoimmunity pathways. J Autoimmun 2015; 64:53–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gasparini G, Cozzani E, Parodi A. Interleukin‐4 and interleukin‐13 as possible therapeutic targets in systemic sclerosis. Cytokine 2020; 125:154799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aletaha D, Alasti F, Smolen JS. Rituximab dissociates the tight link between disease activity and joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72:7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Terrier B, Amoura Z, Ravaud P et al Safety and efficacy of rituximab in systemic lupus erythematosus: results from 136 patients from the French AutoImmunity and Rituximab registry. Arthritis Rheumatol 2010; 62:2458–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Daoussis D, Melissaropoulos K, Sakellaropoulos G et al A multicenter, open‐label, comparative study of B‐cell depletion therapy with Rituximab for systemic sclerosis‐associated interstitial lung disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017; 46:625–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jordan S, Distler JH, Maurer B et al Effects and safety of rituximab in systemic sclerosis: an analysis from the European Scleroderma Trial and Research (EUSTAR) group. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74:1188–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lafyatis R, Kissin E, York M et al B cell depletion with rituximab in patients with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 60:578–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dumoitier N, Chaigne B, Régent A et al Scleroderma peripheral B lymphocytes secrete interleukin‐6 and transforming growth factor β and activate fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017; 69:1078–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ummarino D. Rheumatoid arthritis: defective IL‐10‐producing Breg cells. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2017; 13:132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Daien CI, Gailhac S, Mura T et al Regulatory B10 cells are decreased in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and are inversely correlated with disease activity. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014; 66:2037–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ota Y, Niiro H, Ota S et al Generation mechanism of RANKL (+) effector memory B cells: relevance to the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2016; 18:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Taher TE, Ong VH, Bystrom J et al Association of defective regulation of autoreactive IL‐6‐producing transitional B lymphocytes with disease in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018; 70:450–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mavropoulos A, Simopoulou T, Varna A et al Breg cells are numerically decreased and functionally impaired in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016; 68:494–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Becher B, Tugues S, Greter M. GM‐CSF: from growth factor to central mediator of tissue inflammation. Immunity 2016; 45:963–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Binai N, O'Reilly S, Griffiths B, van Laar JM, Hügle T. Differentiation potential of CD14+ monocytes into myofibroblasts in patients with systemic sclerosis. PLOS ONE 2012; 7:e33508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lescoat A, Ballerie A, Augagneur Y et al Distinct properties of human M‐CSF and GM‐CSF monocyte‐derived macrophages to simulate pathological lung conditions in vitro: application to systemic and inflammatory disorders with pulmonary involvement. Int J Mol Sci 2018; 19;pii:E894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Croxford AL, Lanzinger M, Hartmann FJ et al The cytokine GM‐CSF drives the inflammatory signature of CCR2+ monocytes and licenses autoimmunity. Immunity 2015; 43:502–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shiomi A, Usui T, Ishikawa Y, Shimizu M, Murakami K, Mimori T. GM‐CSF but not IL‐17 is critical for the development of severe interstitial lung disease in SKG mice. J Immunol 2014; 193:849–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Nieuwenhuijze AE, van de Loo FA, Walgreen B et al Complementary action of granulocyte macrophage colony‐stimulating factor and interleukin‐17A induces interleukin‐23, receptor activator of nuclear factor‐κB ligand, and matrix metalloproteinases and drives bone and cartilage pathology in experimental arthritis: rationale for combination therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2015; 17:163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sendo S, Saegusa J, Okano T, Takahashi S, Akashi K, Morinobu A. CD11b+ Gr1dim tolerogenic dendritic cell‐like cells are expanded in interstitial lung disease in SKG mice. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017; 69:2314–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reynolds G, Gibbon JR, Pratt AG et al Synovial CD4+ T‐cell‐derived GM‐CSF supports the differentiation of an inflammatory dendritic cell population in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016; 75:899–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Muls N, Nasr Z, Dang HA, Sindic C, van Pesch V. IL‐22, GM‐CSF and IL‐17 in peripheral CD4+ T cell subpopulations during multiple sclerosis relapses and remission. Impact of corticosteroid therapy. PLOS ONE 2017; 12:e0173780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li R, Rezk A, Miyazaki Y et al Proinflammatory GM‐CSF‐producing B cells in multiple sclerosis and B cell depletion therapy. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7:310ra166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R et al Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): classification, subsets and pathogenesis. J Rheumatol 1988; 15:202–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sato S, Hasegawa M, Takehara K. Serum levels of interleukin‐6 and interleukin‐10 correlate with total skin thickness score in patients with systemic sclerosis. J Dermatol Sci 2001; 27:140–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Michel L, Farge D, Baraut J et al Evolution of serum cytokine profile after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in systemic sclerosis patients. Bone Marrow Transplant 2016; 51:1146–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yoshida T, Mei H, Dörner T et al Memory B and memory plasma cells. Immunol Rev 2010; 237:117–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ueno H. Human circulating T follicular helper cell subsets in health and disease. J Clin Immunol 2016; 36:34–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kubo M. T follicular helper and TH2 cells in allergic responses. Allergol Int 2017; 66:377–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Junttila IS. Tuning the cytokine responses: an update on interleukin (IL)‐4 and IL‐13 receptor complexes. Front Immunol 2018; 9:888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yamamoto J, Adachi Y, Onoue Y et al CD30 expression on circulating memory CD4+ T cells as a Th2‐dominated situation in patients with atopic dermatitis. Allergy 2000; 55:1011–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mavalia C, Scaletti C, Romagnani P et al Type 2 helper T‐cell predominance and high CD30 expression in systemic sclerosis. Am J Pathol 1997; 151:1751–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jourdan M, Caraux A, Caron G et al Characterization of a transitional preplasmablast population in the process of human B cell to plasma cell differentiation. J Immunol 2011; 187:3931–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chapuis F, Rosenzwajg M, Yagello M, Ekman M, Biberfeld P, Gluckman JC. Differentiation of human dendritic cells from monocytes in vitro . Eur J Immunol 1997; 27:431–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. van Kooyk Y,Geijtenbeek TB. DC‐SIGN: escape mechanism for pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol 2003; 3:697‐709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rubio‐Rivas M, Corbella X, Pestaña‐Fernández M et al First clinical symptom as a prognostic factor in systemic sclerosis: results of a retrospective nationwide cohort study. Clin Rheumatol 2018; 37:999–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Allanore Y, Denton C, Khanna D et al Efficacy and safety of romilkimab in diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis (dcSSc): a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, 24‐week, proof of concept study [Abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019; 71(suppl 10). [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ricard L, Jachiet V, Malard F et al Circulating follicular helper T cells are increased in systemic sclerosis and promote plasmablast differentiation through the IL‐21 pathway which can be inhibited by ruxolitinib. Ann Rheum Dis 2019; 78:539–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Taylor DK, Mittereder N, Kuta E et al T follicular helper‐like cells contribute to skin fibrosis. Sci Transl Med 2018; 10:eaaf5307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Horie R, Watanabe T. CD30: expression and function in health and disease. Semin Immunol 1998; 10:457–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Romagnani S, Del Prete G, Maggi E, Chilosi M, Caligaris‐Cappio F, Pizzolo G. CD30 and type 2 T helper (Th2) responses. J Leukoc Biol 1995; 57:726–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mokada‐Gopal L, Boeser A, Lehmann CHK et al Identification of Novel STAT6‐regulated proteins in mouse B cells by comparative transcriptome and proteome analysis. J Immunol 2017; 198:3737–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Raker VK, Ook KY, Haub J et al Myeloid cell populations and fibrogenic parameters in bleomycin‐ and HOCl‐induced fibrosis. Exp Dermatol 2016; 25:887–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xie Y, Zhang X, Inoue Y, Wakasugi S, Makino T, Ihn H. Expression of CD1a and CD86 on scleroderma Langerhans cells. Eur J Dermatol 2008; 18:50–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mokuda S, Miyazaki T, Ubara Y et al CD1a+ survivin+ dendritic cell infiltration in dermal lesions of systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Res Ther 2015; 17:275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Affandi AJ, Carvalheiro T, Radstake TRDJ, Marut W. Dendritic cells in systemic sclerosis: advances from human and mice studies. Immunol Lett 2018; 195:18–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lafyatis R, O'Hara C, Feghali‐Bostwick CA, Matteson E. B cell infiltration in systemic sclerosis‐associated interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheum 2007; 56:3167–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Khanna D, Denton CP, Lin CJF et al Safety and efficacy of subcutaneous tocilizumab in systemic sclerosis: results from the open‐label period of a phase II randomised controlled trial (faSScinate). Ann Rheum Dis 2018; 77:212–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang W, Bhattacharyya S, Marangoni RG et al The JAK/STAT pathway is activated in systemic sclerosis and is effectively targeted by tofacitinib. J Scleroderma Relat Disord 2019. 10.1177/2397198319865367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. O’Shea JJ. Targeting the Jak/STAT pathway for immunosuppression. Ann Rheum Dis 2004; 63:ii67–ii71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fleischmann R, Kremer J, Cush J et al Placebo‐controlled trial of tofacitinib monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:495–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bosello S, Angelucci C, Lama G et al Characterization of inflammatory cell infiltrate of scleroderma skin: B cells and skin score progression. Arthritis Res Ther 2018; 20:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. (a) The purity of memory B cells isolated by flow cytometry. The left panel shows expression of CD19 and CD27 on B cells before sorting. The right panel shows expression of CD19 and CD27 on B cells after sorting. (b) The histogram of IL‐4R in resting and BCR/CD40‐stimulated B cells. Shadow: isotype control; Solid line: IL‐4R in BCR/CD40‐stimulated memory B cells; Dotted line: IL‐4R in resting memory B cells.

Fig. S2. Dose titration of IL‐4, IL‐13 and TGF‐β. Purified memory B cells stimulated with the designated dose of IL‐4 (a), IL‐13 (b), or TGF‐β (c) in combination with anti‐BCR and CD40L were cultured for 24 h. Cells were harvested, then, GM‐CSF mRNA was evaluated by qPCR. ** indicates P < 0.01, un: undetected.

Table S1. Baseline characteristics.