Abstract

This cohort study examines the outcome of venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in 40 patients recently hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 in the US.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) can lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), necessitating prolonged mechanical ventilation.1 In some cases, even ventilatory support fails. Venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has been used in severe cases of respiratory failure.2 However, the need for prolonged ventilation, sedation, and immobility may limit its long-term benefits.3 The application of ECMO in patients with COVID-19 whose condition has rendered mechanical ventilatory support insufficient is not fully established. We present our experience in using single-access, dual-stage venovenous ECMO, with an emphasis on early extubation of patients while they received ECMO support.

Methods

Data were collected retrospectively from 40 consecutive patients with COVID-19 who were in severe respiratory failure and supported with ECMO. Each diagnosis of COVID-19 was confirmed using polymerase chain reaction–based assays. Patients were treated at 2 tertiary medical centers in Chicago, Illinois, from March 17 to July 17, 2020. The research protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the Advocate Christ Medical Center and the Rush University Medical Center with a waiver for consent because of the inability of patients to give consent. A single-access, dual-stage right atrium–to-pulmonary artery cannula was implanted (eFigure in the Supplement), following which ventilation was discontinued while the patient continued to receive ECMO. Patient selection criteria were similar to those of the ECMO to Rescue Lung Injury in Severe ARDS (EOLIA) trial group (eMethods in the Supplement).2 The primary outcome was survival following safe discontinuation of ventilatory and ECMO supports. Excel for Office 365 2020 (Microsoft) was used for data analysis.

Results

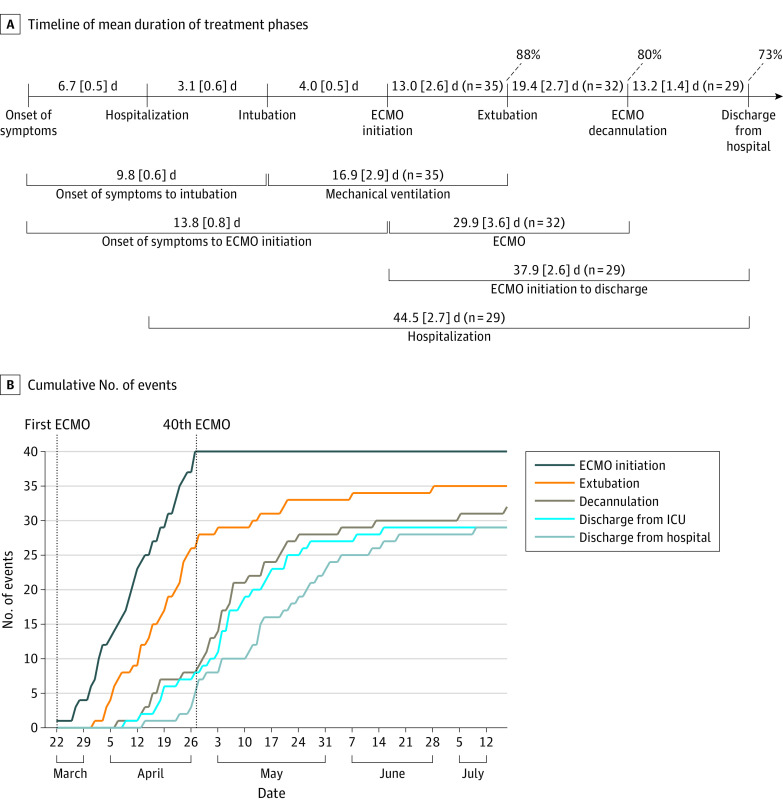

Care with ECMO was performed in 40 consecutive patients between the ages of 22 and 64 years (mean [SE] age, 48.4 [1.5] years); 30 (75%) were men, 16 (40%) were African American individuals, and 14 (35%) were Hispanic individuals (Table). The mean (SE) body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) was 34.2 (1.1). Obesity was the primary preexisting condition (28 patients [70%]). All patients reached maximum ventilator support, with 90% placed in a prone position (29 patients [73%]), paralyzed (31 patients [78%]), or both, pre-ECMO; 24 patients (60%) required vasopressors. Eleven patients could not be placed in a prone position because of increasing hemodynamic instability and/or worsening oxygenation or ventilation with pronation. All patients demonstrated considerably elevated levels of inflammatory markers, such as D-dimer and ferritin, prior to ECMO use. The mean (SE) time from intubation to ECMO was 4.0 (0.5) days (Figure, A).

Table. Patient Characteristics (N = 40).

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Prehospitalization | |

| Age, mean (SE), y | 48.4 (1.5) |

| Median (range), y | 51 (22-64) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 30 (75) |

| Female | 10 (25) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 8 (20) |

| African American | 16 (40) |

| Hispanic | 14 (35) |

| Other | 2 (5) |

| BMI, mean (SE) [range] | 34.2 (1.1) [20.4-52.4] |

| Medical history | |

| Obesitya | 28 (70) |

| Hypertension | 23 (58) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 7 (18) |

| Diabetes | 10 (25) |

| Asthma | 6 (15) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 (3) |

| Smoking | 7 (18) |

| Alcohol use | 11 (28) |

| Coronary artery disease | 1 (3) |

| Deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism | 6 (15) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4 (10) |

| Stroke | 0 |

| Pre–extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | |

| Ventilator settings | |

| FiO2, mean (SE) | 0.98 (0.01) |

| PEEP, mean (SE) [median], cm H2O | 17.0 (0.5) [16] |

| Respiratory rate, mean (SE), breaths/min | 25.8 (1.1) |

| Tidal volume, mean (SE), mL | 429.4 (12.1) |

| Peak pressure, mean (SE) [median], cm H2O | 40.0 (2.0) [38] |

| Plateau pressure, mean (SE) [median], cm H2O | 32.7 (0.8) [32] |

| Arterial blood gas, mean (SE) | |

| pH, mean (SE) | 7.24 (0.02) |

| PaCO2, mean (SE) [median], mm Hg | 71.6 (2.5) [68] |

| PaO2, mean (SE) [median], mm Hg | 66.9 (2.8) [66] |

| O2 saturation, mean (SE), % | 88.7 (1.5) |

| PaO2/FiO2, mean (SE) [median] | 68.9 (3.1) [66] |

| Bicarbonate, mean (SE), mEq/L | 27.7 (0.9) |

| Pronation | 29 (73) |

| Chemical paralysis | 31 (78) |

| Vasopressors | 24 (60) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, mean (SE), % | 59.3 (2.3) |

| Inflammatory markers, mean (SE) | |

| D-dimer, μg/mL | 13.9 (2.0) |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 1844.3 (254.1) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; PaCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; Pao2, partial pressure of oxygen; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure.

SI conversion factors: To convert D-dimer to nmol/L, multiply by 5.476; ferritin to μg/L, multiply by 1.0.

Obesity defined as a BMI greater than 30.

Figure. Timeline.

A, Timeline with detailed mean (SE) durations of the various treatment phases. Percentages of patients who have been extubated, decannulated from extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and discharged from the hospital are also stated. All data points include 40 patients unless otherwise indicated. B, Cumulative number of events are plotted by date. ICU indicates intensive care unit.

As of July 17, ventilator support has been successfully discontinued in all patients, resulting in a mean (SE) time of 13.0 (2.6) days from ECMO initiation to extubation, while 32 (80%) were no longer receiving ECMO care (Figure, A). Twenty-nine (73%) have been discharged from the hospital while no longer receiving oxygen. Complications have been minimal, with no ischemic strokes, inotropic support, or tracheostomies. Ten patients required reintubation; however, they have all since been extubated. Mortality was 15% (6 patients). The mean duration of each treatment phase is detailed in the Figure, A. The cumulative numbers of events are shown in the Figure, B. All patients were treated with systemic anticoagulation.

Discussion

We investigated the role of ECMO in patients with severe COVID-19 respiratory failure. Demographics, extent of respiratory failure, and pre-ECMO medical management optimization were similar to those of the EOLIA group.2

The single-access, dual-stage cannula offered several advantages: direct pulmonary artery flow, thus improving oxygenation and ventilation; early mobility once off the ventilator; minimal cannula-associated complications or revisions, dissimilar to femoral cannulations4; and finally, support of the right side of the heart in case of right ventricular dysfunction. Given the higher prevalence of and associated mortality with acute cor pulmonale in patients with COVID-19,5 protecting the right side of the heart was critically important.

Prolonged ventilation, including the need for sedatives and patient immobility, may lead to complications.3 By mid-July, all patients have ceased needing a ventilator. Our specialized team of intensive care unit staff mobilized patients while they received care with the ECMO, promoting active patient participation in the recovery process.

Patients with COVID-19 are prone to developing generalized thrombosis, including intracardiac thrombi.5 We have also observed thrombosis within the ECMO circuits and oxygenators. For these reasons, all patients received systemic anticoagulation.

The limited studies on patients with COVID-19 requiring ECMO have thus far demonstrated poor survival.6 Overall, this study demonstrates promising outcomes, with most patients alive and no longer receiving ventilator care and ECMO support and 73% discharged and no longer receiving oxygen. Complications have been minimal; there were no ischemic strokes, inotropic support, and tracheostomy requirements because of the early extubation strategy. Mortality was 15%.

While this study has limitations because it is still an early, retrospective report on 40 patients, single-access, dual-stage venovenous ECMO with early extubation appears to be safe and effective in patients with COVID-19 respiratory failure. Ongoing studies are required, however, to further define the long-term outcomes of this approach.

eMethods. Supplemental Text.

eReference.

eFigure. ECMO Technique.

References

- 1.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. ; and the Northwell COVID-19 Research Consortium . Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052-2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Combes A, Hajage D, Capellier G, et al. ; EOLIA Trial Group, REVA, and ECMONet . Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(21):1965-1975. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill AD, Fowler RA, Burns KE, Rose L, Pinto RL, Scales DC. Long-term outcomes and health care utilization after prolonged mechanical ventilation. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(3):355-362. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201610-792OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lubnow M, Philipp A, Foltan M, et al. . Technical complications during veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and their relevance predicting a system-exchange—retrospective analysis of 265 cases. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e112316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creel-Bulos C, Hockstein M, Amin N, Melhem S, Truong A, Sharifpour M. Acute cor pulmonale in critically ill patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):e70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henry BM, Lippi G. Poor survival with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): pooled analysis of early reports. J Crit Care. 2020;58:27-28. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Supplemental Text.

eReference.

eFigure. ECMO Technique.