Sir,

On 1 April 2020 a 66-year-old woman was seen in the emergency room for dyspnoea. She also suffered from diffuse pain and severe fatigue for two days and headache, fever, dysgeusia and agenesis for four days. She had received a 1 g dose of azithromycin, with no improvement. Chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed bilateral ground glass opacities compatible with COVID-19, although the nasopharyngeal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was negative. She was sent home to be confined and treatment with amoxicillin-clavulanate and doxycycline was initiated, without improvement. On 6 April she began treatment with prednisolone 60 mg/day. Three days later the patient reported cheilitis. The next day an erythematous, pustular, non-pruriginous rash appeared on the neck and slowly spread to the upper trunk (Fig. 1 ). The possibility of a drug reaction was raised, but the rash improved without interruption of antibiotic therapy. A skin biopsy was performed on the neck on 12 April. Clinical signs improved significantly from 13 April onwards.

Fig. 1.

Clinical picture showing the erythematous and pustular rash of the neck.

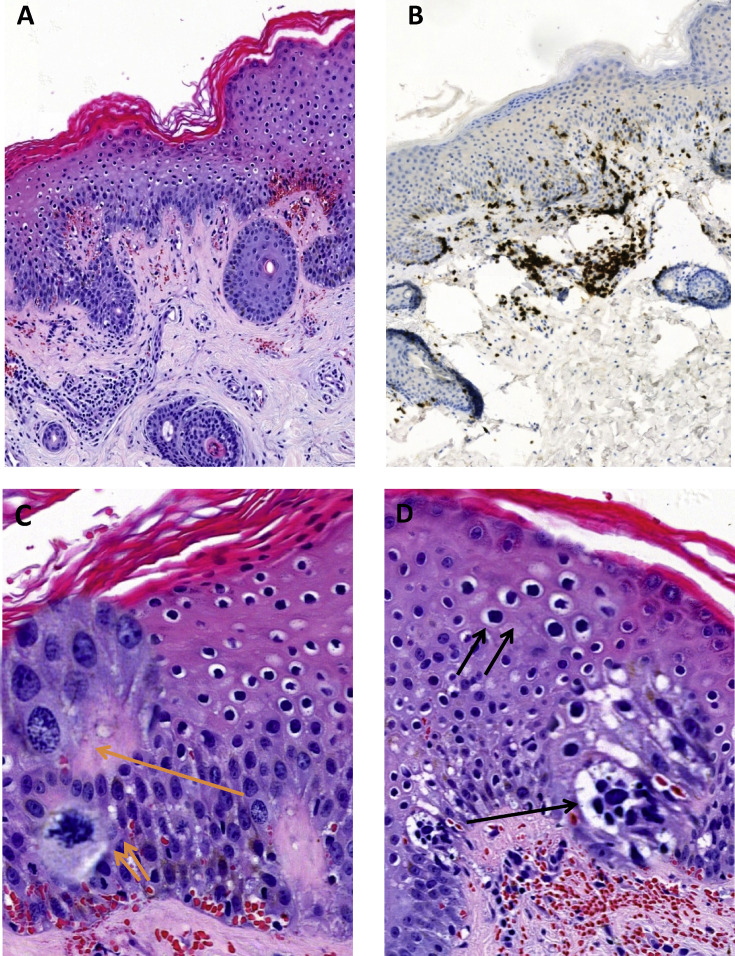

The histological examination of the cutaneous lesion using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining showed hyperkeratosis acanthotic epidermis with focal parakeratosis (Fig. 2 A). Some superficial and intermediate keratinocytes had hyperchromatic nuclei and clear peri-nuclear halo (koilocyte-like cells). The cellular modifications were more marked in the basal layers of the epidermis. We observed a moderate cellular atypia with an increase in cell size and cytoplasm vacuolation (foamy degeneration), enlarged nuclei, often vesicular in appearance, with prominent nucleoli. Some nuclei had diffused fine chromatin, others had coarse-looking chromatin condensations. We observed an increased number of mitoses in the basal layer of the epidermis, some of which were atypical (Fig. 2C,D). The papillary dermis was slightly oedematous with dilated small vessels associated with extravasated erythrocytes. In the superficial and reticular dermis, a moderate perivascular inflammatory infiltrate was observed, consisting mainly of lymphocytes. Neutrophils were visible mainly in the lumen of vessels, without appearance of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. The nuclei of some endothelial cells appeared swollen and turgid. We did not observe inclusion bodies or syncytial polynuclear giant cells, neither in epidermal keratinocytes nor in vascular endothelial cells.

Fig. 2.

Histological findings of cutaneous COVID-19 lesion. (A) Acanthotic epidermis with moderate perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis (H&E). (B) The majority of lymphocytes are of T CD3+ phenotype (IHC). (C) The nuclear and chromatin modifications (H&E stain, one orange arrow and focus spot), and an atypical mitosis (H&E stain, two orange arrows and focus spot). (D) Foamy cytoplasmic vacuolation (H&E stain, one black arrow and focus spot), and koilocyte-like perinuclear halo (H&E stain, one black arrow and focus spot).

A complementary immunohistochemical study revealed a prominent T lymphocytes infiltrate (CD3+), mostly T ‘helper’ CD4+ (65%) with some T ‘cytotoxic’ CD8+ (35%) (Fig. 2B). In addition, there was a discrete intraepidermal T lymphocytic exocytosis (CD3+ and CD4+), and very few B lymphocytes (CD20+) in the upper dermis.

These unusual epidermal histological changes (Fig. 2C,D) in the absence of significant interface dermo-epidermal inflammatory infiltrate or leukocytoclastic vasculitis may correspond to a viral cytopathogenic effect.

Since the first clinical reports of COVID-19 in China, this infection has been linked to several cutaneous signs: maculo-papular rash, urticaria, chickenpox-like lesions,1 , 2 pseudo chilblains,3 dengue-like rash with petechiae,4 livedo or necrosis.5 Case reports of skin symptoms in COVID-19 often lack clinical images and/or histology. Unspecific histological findings have been reported so far, including a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and dermal oedema,6 or undetailed signs consistent with viral infection.2

In this letter, we report a pustular and erythematous rash, another example of the various skin presentations of COVID-19. This disease has already been linked to rashes mimicking drug related exanthema.7 This rash could have been mistaken for skin drug reaction but the clinical improvement despite continuation of the treatment is not in favour of this hypothesis, nor is the histology. More importantly, we report histological images of possible cytopathogenic signs of SARS-CoV-2 infection in cutaneous tissue, suggesting a direct effect of the viral infection on skin cells. Herpes-like aspects have recently been observed in keratinocytes of an infected patient in Italy.8 In addition, the presence of the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and proteases already implicated in SARS-CoV-2 infection in the skin would allow the infestation of cutaneous tissue by the virus.9, 10, 11 Obviously, the formal confirmation of such a hypothesis requires the detection of the virus or its particles in the infected epidermis using immunohistochemistry or PCR technique.

Conflicts of interest and sources of funding

The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:e212–e213. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marzano A.V., Genovese G., Fabbrocini G., et al. Varicella-like exanthem as a specific COVID-19-associated skin manifestation: multicenter case series of 22 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hedou M., Carsuzaa F., Chary E., et al. Comment on “Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective” by Recalcati S. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:e299–e300. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joob B., Wiwanitkit V. COVID-19 can present with a rash and be mistaken for dengue. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:e177. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galván Casas C., Català A., Carretero Hernández G., et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:71–77. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez-Nieto D., Ortega-Quijano D., Segurado-Miravalles G., et al. Comment on: cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. Safety concerns of clinical images and skin biopsies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:e252–e254. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahé A., Birckel E., Krieger S., Merklen C., Bottlaender L. A distinctive skin rash associated with coronavirus disease 2019? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:e246–e247. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gianotti R., Veraldi S., Recalcati S., et al. Cutaneous clinico-pathological findings in three COVID-19-positive patients observed in the metropolitan area of Milan, Italy. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100 doi: 10.2340/00015555-3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grzegrzolka J., Swiatko K., Pula B., et al. ACE and ACE2 expression in normal and malignant skin lesions. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2013;51:232–238. doi: 10.5603/FHC.2013.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ziegler C.G.K., Allon S.J., Nyquist S.K., et al. SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 is an interferon-stimulated gene in human airway epithelial cells and is detected in specific cell subsets across tissues. Cell. 2020;181:1016–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drak Alsibai K. Expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and proteases in COVID-19 patients: a potential role of cellular FURIN in the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2. Med Hypotheses. 2020;143:109893. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]