Summary box.

Studies conclude that frameworks and tools defining governance have been developed independently, seldom building on strengths and weaknesses as well as practical applications of previous instruments.

However, these existing frameworks lack a shared frame of reference which may enable governance to become a truly actionable health system function. This conceptual challenge creates considerable gaps in the way we have appraised and applied governance in health systems.

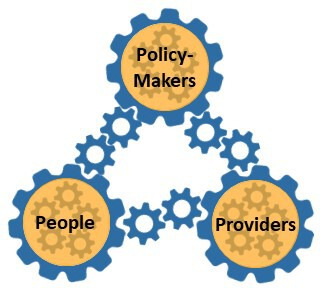

We propose here an adaptation of the governance triangle put forward in the World Development Report 20048 exploring six governance spaces between and within three categories of stakeholders: policy makers, providers of health services and the people.

This paper uses the framework to further explore both formal and informal relations between stakeholders in the governance triangle and identify, as we reflect on our past investments in health system governance, a number of gaps or ‘missing links’.

These missing links relate to formal relations of accountability, relations of power, the exercise of population voice and collective action in health systems.

Exploring the missing links described in this paper will help us better understand governance mechanisms in health system and design and implement more effective health policies and interventions.

Introduction

Over the past decades, health systems have experienced major transformation. The role of ministries of health has changed, progressively shifting from direct provision of health services to overall stewardship of the health sector, including financing and oversight of private providers.1 Health reforms have triggered that shift, fostering new institutions, such as national medicines agencies, public health agencies, disease control agencies (eg, National Cancer Agencies) or health financing organisations responsible for risk and fund pooling, purchasing of health services, or targeting the poor or vulnerable groups. Shocks such as political or financial crises, natural disasters or epidemics have also affected the governing of the health system in many countries. In this changing environment, exercising stewardship2 requires balancing the interest of a wide range of actors, particularly when decentralisation multiplies the number of actors involved in health services delivery, usually with greater autonomy.

Health systems processes must move from a top-down to inclusive policy, planning and implementation processes, increasingly adopting a people-centred approach.3 Democratic rights, human rights, equity and ethics values have become prominent in national policy debates. In response to this call, twenty-first century health systems need to be participatory, inclusive and pluralist, following Whole of Society and Whole of Government principles.3 4 People’s voice is a core driver of health systems’ performance towards Universal Health Coverage.5 In such a context, governance arrangements are changing and rely more on inclusion, participation and co-production.6

This paper presents a framework to help understand health systems governance; examine what we know about this important health system function, and what has been less explored, leaving an important gap in our health system knowledge and practice.

Conceptual framework

In this paper, we understand ‘governance’ as ‘ensuring that strategic policy frameworks exist and are combined with effective oversight, coalition building, regulation, attention to system-design and accountability’.7 The framework proposed here (figure 1) is an adaptation of the governance triangle put forward in the World Development Report 2004,8 further adapted by Brinkerhoff and Bossert in 2008.9 The governance triangle reflects the set of arrangements that are the fabric of governance in practice by exploring key relationships between and within three categories of stakeholders: Policy-makers, Providers of health services and the People:

Figure 1.

Health Systems Governance Framework (adapted from World Development Report 2004.8).

Policy makers: include different government organisations and agencies at the central and subnational levels, and the way they are organised in terms of hierarchy, delegations of authority and cooperative linkages, and so on. Actors in this sphere include the legislative and the executive branches, elected (politicians) and non-elected (bureaucrats) officials.

Health services providers: the different public and private (for and not-for-profit) clinical, paramedical and non-clinical health services providers (practitioners, clinical facilities and hospitals, pharmacies, laboratories, paramedical facilities, etc); unions and other professional associations (all cadres); networks of care or of services. Organisations responsible for supply of medicines as well as training of health professionals are part of the providers’ sphere, and so on.

People: citizens and residents, population representatives, patients’ associations, Civil Society Organisation (CSOs)/Non Governmental Organisations (NGOs), citizens’ associations protecting the poor or the elderly, the Media, and so on. Citizens become service users when they interact with health service providers.

We have purposively decided to replace the arrows of the original triangle by a series of gears, to picture the dynamic and interconnected nature of relationships linking stakeholders in health systems.

We also propose to unpack the governance triangle in more detail by examining six different spaces where governance function takes place:

Three spaces between the spheres: the relationships between the three spheres, formally or informally linking categories of stakeholders to each other.

Three spaces within the spheres: the relationships within the three spheres described above, formally or informally linking the variety of stakeholders within each sphere or category.

Relationships between the spheres

Between the Policy makers and Providers: Policy makers set objectives’ standards and rules and provide financial and non-financial resources in exchange for an agreed level and quality of services. Depending on the level of transparency of the system, providers and lobbies can sometimes use this space to exert considerable pressure on decision makers.

Between Providers and the People: This relationship is at the heart of the health system and refers to the organisation and delivery of promotive, preventive and curative health services. The ability for users to exercise their client power strengthens utilisation and quality of services and increases providers’ accountability to service users. Providers can also influence the behaviour of users through information dissemination.

Between the People and the Policy-Makers: The relationship is the exercise of voice, which consists of the expression of demands, needs and preferences of the population. This could be through processes such as elections, lobbying and advocacy, media, activism, formal population consultation processes in the health sector (eg, National Health Assemblies, national surveys, etc). However, practices like tokenism or distortion of the information disseminated (eg, through state-owned media) can undermine the impact of participatory processes. Political accountability ensures a certain level of participation and that voice is taken into consideration.

Relationships within the spheres

Within the Policy-makers sphere: Through a system of checks and balances, the legislative branch holds the executive power accountable and ensures reasonable use of power in accordance with the constitution. The Policy-makers sphere is also the arena of multisectoral engagement and power delegation. Relationships within this sphere include processes of delegation, of engagement between ministries (eg, Ministry of Health and Ministry of Finance), and of influence struggle between the different stakeholder groups such as parliamentarians, executive power and non-elected officials.

Within the Providers sphere: Relationships in the providers sphere are largely composed of those among the market of healthcare provision. Providers can choose to compete or cooperate and form networks of care, depending on the national policies regulating the sector. In this space workers can form associations and unions to hold their own members to account, according to professional charters; and to negotiate with health facilities for a fair work environment.

Within the People sphere: It is important to disaggregate the People sphere, as it comprises a wide diversity of stakeholder groups with very different vested interests. Relationships in that sphere involve different interest groups competing for their increased benefit in a finite pool of resources (eg, patient groups lobbying for inclusion in benefit packages, the elite and the poor negotiating for a balance between financial coverage and health taxes). Consensus among this group can be reached through vote, however small groups with important vested interests are more likely to influence the system while other groups that are less strongly affected are, therefore, less likely to organise actively and efficiently to defend their interests.10 The political process is typically influenced by the balance of power between the elite, the middle class and the poor. But other proximates of this balance can be found such as language, religion, and ethnic or geographical background. These relationships rely heavily on information and influence and are reflected in the behaviour of the media.

The key relationships between governance stakeholders that are the very fabric of the triangle can be divided into two categories: formal mechanisms and informal processes.

Missing links

The past decade experienced an increase of the literature on health system governance; various frameworks presenting attributes or dimensions of governance have emerged and define the nature and scope of this function.11 12 In a review published in 2014, Barbazza and Tello highlight the challenge of reaching a consensus and communicating a clear agenda on governance in health.10 They conclude that frameworks and tools defining governance have been developed independently, seldom building on strengths and weaknesses as well as practical applications of previous instruments; they lack a shared frame of reference which would enable governance to become a truly actionable health system function. In a more recent systematic review (2017), Pyone et al identify 16 frameworks for health systems governance published between 1994 and 2016, but only 5 of them have been applied in practice.12

While approaches are bound to differ given the nature, goals and target audiences of the different tools, governance as a field still lacks a broad consensus on basic concepts, models and measurements. This conceptual challenge hinders considerably our capacity to compare research and nourish an actionable governance evidence base; it also creates considerable gaps in the way we have appraised and applied governance in health systems. In reference to the ‘triangle’ conceptual framework referred to in this paper, we, as a global health community, have essentially focused on one sphere of stakeholders, that is, the providers; venturing only partially in the spheres of policy makers and clients.

Our main concern has been to strengthen service delivery, essentially through the supply of services in relation to norms and standards (eg, essential health service packages). We have supported and strengthened health services supply by investing in compacts: health system strengthening interventions have focused on improving service quality and enhancing performance through financial and non-financial incentives. Performance-based financing is an excellent example of how we have, in the past decade or so, concentrated our efforts on strengthening the compact.13

Furthermore, we have so far equated governance with government, recognising only the legitimacy of the Ministry of Health as the main governing body in the health sector.

As we reflect on our past investments in health system governance, a number of gaps or ‘missing links’ appear clearly and would warrant further investments in the future. These missing links relate to formal relations of accountability, relations of power, the exercise of population voice and collective action in health systems. They are detailed hereafter.

Formal relations of accountability

Focusing on service delivery and the stewardship role of the Ministry of Health,8 we have, in the past neglected other formal stakeholders and relations of accountability that link these together.

Modern health systems however require engagement of multiple players in both legislative and executive arms of the government, starting with parliaments to ministry of finance. Many areas such as the fight against Non Communicable Diseases (NCDs) or antimicrobial resistance require engagement of ministries of agriculture, industry or commerce. In many countries, independent or autonomous agencies such as public health or medicines agencies, as well as social health insurance organisations participate in the governance function in the health system. In fact, relationships among these agencies and between these agencies and ministries of health; as well as division of roles and responsibilities, and definition of accountability lines is critically important in the decision making arena. We have to invest more in understanding often messy health system architectures, mandates of respective ministries and agencies, and how this influences decision making at both policy and implementation levels. This includes processes such as mapping actors and their mandates in the health systems, exploring their capacity to carry these mandates out, and examining how models that have worked in some setting have been adapted to different contexts to fit their individual governance and institutional environment.

Relations of power

In parallel to the formal divisions of roles and responsibilities between organisations taking part in health systems governance, relations of power create informal links or tensions between stakeholder groups in the health system. Analyses of the political economy of health interventions and reform do exist14 but they are rare and the skills to perform these analyses in major organisations such as WHO are still scarce.15

The World Development Report 2017 highlights power asymmetries and the direct influence of elites in reforms, whether by wielding de jure (eg, formally mandated) or de facto power (eg, control over resources).16 Changes in a society occur only when powerful elites agree to that change whereas resistance to change from those elites create suboptimal policies and governance arrangements. Elites are different from one policy arena to the other and we must try to understand who the health elites are. Elites are themselves not a monolithic group and we should investigate what informal powerful relationships link them together, what are their different preferences and what are their different incentives.

Informal power relations can happen between spheres. A recent example in Morocco is the medical students’ strike with a massive boycott of medical schools’ examinations by all public medical schools students, well aware that they represent a rare health system resource.17 Another past example is the massive strike of South Korean doctors when the regulations on separation of prescribing and dispensing were issued.18 In these two examples, provider groups use their collective power to confront the main formal relation that we have invested in strengthening, that is, the compact, undermining its potential to deliver on health system performance.

Informal power relations can also occur within spheres. This happens, for example, when policy makers in the government are from different political parties, belong to different ethnic groups or emerge from different elites and fundamentally disagree on health issues such as tobacco laws, sexual and reproductive rights, or health matters that have strong social, cultural or commercial determinants. In these situations, they cannot meaningfully engage in multisectoral action as what divides them belongs to hidden informal relations that evidence, norms or standards cannot overcome.

Population voice

Another important missing link in our approaches to health systems governance is that we have neglected the sphere of ‘People’. At best, we have limited this stakeholder group to the ‘Patients’, the passive users of health services. And even in that role, consideration is often only given to the users who need curative care. Even in the field of population health, we have engaged with communities as recipients of promotion and prevention services. Only recently, a trend has emerged towards considering individuals and communities as actors of their own health and as important stakeholders in priority setting, planning and monitoring of health interventions.19

While people-centred approaches are put forward in integrated model of service delivery or primary healthcare, they are often designed to support services supply. Population voice, as a powerful governance mechanism, holding decision makers responsible and providers accountable has seldom been explored or used as a governance mechanism in the health sector. Attempts to use population voice to improve health system governance exists in examples such as Etats généraux de la santé in France, National Health Assembly in Thailand or Dialogue sociétal in Tunisia.20–22 These are however recent initiatives that we still have to evaluate to understand their impact on improving health system performance and population health.

The promise of these approaches is to reinforce or create a social contract around health, with direct accountability to the population, which represents a potentially potent way of overcoming informal power relations, the influence of political or commercial interest groups on the behaviour of policy makers or providers. Population voice can be fostered through the creation of platforms for citizen engagement, at given time points or on a continuing basis, and at different moments in the policy making and policy implementation continuum.

However, the exercise of population voice in health is difficult to use as a governance mechanism. The trap of tokenism is not easy to avoid.23 There is also the danger that population voice is captured by interest groups such as pharmaceutical companies.24

Collective action

Very often, we place decision making power in the hands of the Minister of Health while actually, critical decisions in health systems may depend on a variety of actors from party elites, local governors, civil society organisations, labour unions and international actors. All stakeholder groups can create coalitions and try to influence the system through collective action: health professionals, medical students, and even patients and citizen. However, some groups—the elites—have more influence over the policy and reform processes. Attention needs to be paid to how social groups can build coalition with elites, whether because they share preferences,25 or by changing their incentives.26 Effective pressure groups have also been built on coalitions between the middle class and the poorest groups, or between social movements and experts. Understanding how these pressure groups arise and the way institutions respond to this pressure is critically important in health systems governance.

A special focus should be applied to understanding how effective collective action has come to appear to support the provision of public goods that affect health (eg, sanitation, road safety, health surveillance system, pollution reduction).27 These goods on which societies have underinvested for a range of behavioural and economic reasons,28 of critical importance as illustrated by the COVID-19 pandemic, cannot be delivered by the market. We must invest more on understanding what events and incentives have driven effective collective action for the provision of this type of goods in the past to design interventions that will foster such action for the future.

Conclusion

The governance triangle is not a new framework and was published 15 years ago to support framing service delivery to the poor and vulnerable populations. It has been applied to health service delivery in the past. This paper however uses the framework to explore further both formal and informal relations between stakeholders in the governance triangle. It serves the dual purpose of continuing to promote a common understanding of health systems governance by building up on widespread approaches, and to identify important gaps warranting further research. Exploring the missing links described in this paper will help us—as practitioners, academics, policy makers and other committed stakeholders—better understand governance mechanisms in health system and design, and implement more effective health policies and interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the “Bellagio Group” for their valuable inputs. The authors also thank the Rockefeller Foundation for supporting the meeting.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @BenjaminRouffy, @bendownslane

Collaborators: The "Bellagio Group": Seye Abimbola; Syed Masud Ahmed; Franz-Hermann Freiherr von Roenne; Nicholas Leydon; Rene Loewenson; Precious Matsoso; Gorik Ooms; Ligia Paina; Shomikho Raha; Cecilia Alejandra Rodriguez Ruiz; Helen Schneider; Archana Shah; Peter Smith; Benjamin Karabu Tsofa; Sara Bert Van Belle; Godelieve Van Heteren; Rajani Ved.

Contributors: MB and AS conceived the idea and structure of this paper. MB, with assistance from BR, wrote the first draft, received and integrated inputs from all authors, and finalised the paper. All authors contributed intellectual content and approved the final version for submission.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data available.

Contributor Information

The Bellagio Group:

Folarin Oluseye Abimbola, Syed Masud Ahmed, Franz-Hermann Freiherr von Roenne, Nicholas Leydon, Rene Loewenson, Precious Matsoso, Gorik Ooms, Ligia Paina, Shomikho Raha, Cecilia Alejandra Rodriguez, Helen Schneider, Archana Shah, Peter Smith, Benjamin Karabu Tsofa, Sara Bert Van Belle, Godelieve Van Heteren, and Rajani Ved

References

- 1. Sriram V, Sheikh K, Soucat A. Addressing governance challenges and capacities in Ministries of health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Travis P, Egger D, Davies P. Towards better stewardship: concepts and critical issues. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kickbusch I, Gleicher D. Governance for Health in the 21stCentury. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schmets G, Kadandale S, Porignon D, et al. . Chapter 1. Introduction : Schmets G, Rajan D, Kadandale S, et al., Strategizing National health in the 21st century: a Handbook. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rohrer K, Rajan D. Chapter 2. Population consultation on needs and expectations : Schmets G, Rajan D, Kadandale S, Strategizing National health in the 21st century: a Handbook. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. WHO Everybody’s business: strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lehmann U, Gilson L. Action learning for health system governance: the reward and challenge of co-production. Health Policy Plan 2015;30:957–63. 10.1093/heapol/czu097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Bank World development report 2004: making services work for poor people. Washington, DC, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brinkerhoff D, Bossert T. Health governance: concepts, experience, and programming options. health systems 2020 policy brief. USAID, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Olson M. The logic of collective action: public goods and the theory of groups. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barbazza E, Tello JE. A review of health governance: definitions, dimensions and tools to govern. Health Policy 2014;116:1–11. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pyone T, Smith H, van den Broek N. Frameworks to assess health systems governance: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan 2017;32:710–22. 10.1093/heapol/czx007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cashin C, Borowitz M. Strengthening health system governance through P4P implementation : Cashin C, Chi Y-L, Smith PC, et al., Paying for performance in healthcare: implications for health system performance and accountability. Berkshire, England: Open University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kelsall T, Heng S. The political economy of inclusive healthcare in Cambodia. effective Sates and inclusive development working paper No. 43, 2014. Available: http://www.effective-states.org/wp-content/uploads/working_papers/final-pdfs/esid_wp_43_kelsall_heng.pdf

- 15. Reich MR. Political economy analysis for health. Bull World Health Organ 2019;97:514. 10.2471/BLT.19.238311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Bank World development report 2017: governance and the law. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kasraoui S. Moroccan medical students defy government, boycott final exams. Morocco world news, 2019. Available: https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2019/06/275512/moroccan-medical-students-boycott-final-exams/

- 18. BBC News South Korea doctors strike, 2000. Available: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/798353.stm

- 19. Rifkin SB. Examining the links between community participation and health outcomes: a review of the literature. Health Policy Plan 2014;29 Suppl 2:ii98–106. 10.1093/heapol/czu076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Letourmy A, Naïditch M. L’émergence de la démocratie sanitaire en France In: Santé, Société et Solidarité, n°2, 2009. La place des usagers dans Le Système de santé, 2009: 15–22. http://www.persee.fr/doc/oss_1634-8176_2009_num_8_2_1346 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rasanathan K, Posayanonda T, Birmingham M, et al. . Innovation and participation for healthy public policy: the first National health assembly in Thailand. Health Expect 2012;15:87–96. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00656.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mathivet B. Citizen involvement in Tunisia. World Health Popul 2017;17:16–18. 10.12927/whp.2017.25156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hahn DL, Hoffmann AE, Felzien M, et al. . Tokenism in patient engagement. Family Practice 2019;34:290–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ozieranski P, Rickard E, Mulinari, S. Exposing drug industry funding of UK patient organisations. BMJ 2019;9:l1806 10.1136/bmj.l1806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Buquet D, Piñeiro R. Uruguay’s Shift from Clientelism. J Democracy 2016;27:139–51. 10.1353/jod.2016.0008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Heller P. Challenges and opportunities: civil society in a globalizing world. UNDP-HDRO occasional paper 2013/06. New York: Human Development Report Office, United Nations Development Programme, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bump JB, Reddiar SK, Soucat A. When do governments support common goods for health? four cases on surveillance, traffic congestion, road safety, and air pollution. Health Syst Reform 2019;5:293–306. 5. 10.1080/23288604.2019.1661212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Savedoff WD. Why do societies ever produce common goods for health? Health Syst Reform 2019;5:402–5. 10.1080/23288604.2019.1655982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]