Abstract

Introduction

Engaging family caregivers could be a critical asset to make the ‘ageing-in-place’ imperative a reality. This is particularly evident in rural and remote areas, where caregivers can fill the gaps that exist due to the fragmentation of the welfare system. However, there is little knowledge about the expectations that family caregivers have from healthcare services in rural and remote areas.

Place4Carers (P4C) project aims to co-produce an innovative organisational model of social and healthcare services for family caregivers of older citizens living in Vallecamonica (Italy). The project is expected to facilitate ageing-in-place for older citizens, thus helping caregivers in their daily care activities.

Methods and analysis

P4C is a community-based participatory research project featuring five work packages (WPs). WP1 consists of a survey of unmet needs of caregivers and older people receiving services in Vallecamonica. WP2 consists of a scoping literature review to map services that provide interventions of support to caregivers living in remote areas and promote engagement. WP3 organises co-creation workshops with caregivers to co-design, co-manage, and co-assess ideas and proposals for shaping caregiver-oriented services and organisational models. WP3 enriches the results of WP1 (survey) and WP2 (scoping literature review), and aims to co-create new ideas for intervention support with and for caregivers in relation to the objectives, features and characteristics of a new service able to address the caregivers’ needs and expectations. WP4 tests the service ideas co-created in WP3 through piloting an intervention based on ideas co-created with caregivers. Finally, WP5 assesses the transferability of the intervention to other similar contexts.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been approved by the Ethics Committees of the Department of Psychology of Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore and Politecnico of Milan. Results will be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals, scientific meetings and meetings with the general population.

Keywords: organisation of health services, qualitative research, health services administration & management

Strengths and limitation of this study.

This study aims to use participatory methods to co-design an accessible and sustainable service for family caregivers of older citizens.

Participation in the planning, design and implementation of the service will include family caregivers, older citizens, researchers and representatives from the welfare system (as ATSP, the agency that provide home services to local community).

To our knowledge, this is the first co-produced study that uses participatory methods to enhance and sustain the role of family caregivers to make ‘ageing-in-place’ a sustainable reality in rural and remote areas.

The methodology of this study implies a multi-stakeholder, multilevel and self-sustainable approach, which will have both short-term and long-term beneficial effects on the possibility to continue the service deployment even after the end of the project.

Further studies are warranted to validate in other context the implied methodology.

Introduction

Rationale of the study

This study’s rationale is based on the insight that successful ageing is a complex phenomenon that is intrinsically intertwined with the ‘places’ and spaces that people belong to.1 Spaces are not only a physical backdrop to events, but also have social, psychological and symbolic meanings.2 People may have quite different life experiences, expectations and opinions related to a particular space. None of these aspects of space (social, physical and symbolic) is necessarily more ‘real’ or important than any other. Instead, they are interconnected and directly dependent on each other.3 Ageing is a dynamic process that is largely influenced by physical, social and cultural spaces.4 Literature5–8 discusses the concept of space in the ageing process from a threefold perspective of (i) ageing spaces as ecosystems, (ii) ageing spaces as mesosystems and (iii) ageing spaces as microsystems. These inter-relationships are particularly noticeable in rural and remote areas. The research setting is Vallecamonica, an outreach territory in Italy and the local partner is ATSP (Azienda Territoriale per i Servizi alla Persona), the agency that provide home services to local community.

Vallecamonica is a mountainous territory in the northern part of the Lombardy region. It is divided into 44 municipalities, all of which have been categorised as ‘peripheral’ or ‘ultra-peripheral’, due to a poor access to services, scarce infrastructures, limited economic prosperity and negative demographic trends. Residential areas in Vallecamonica are geographically dispersed, and the viability is not made easy by the configuration of the territory and the limited network of infrastructures, and public transportation services. The population living in the area is characterised by an ageing index, computed as the ratio between the number of people aged 65 or more and those aged 14 or less, equal to 157.3 (the average for the Lombardy Region is 152.6; DGR X/5208). The high proportion of elderly people attest a situation of a multidimension frailty, with several social and healthcare needs. Against this widespread need, most of the municipalities are at a distance of 20 to 40 km (or more) from the main hospital and healthcare structures (DGR X/5208). Unsurprisingly, the amount of social and assistance services required and provided to support the difficult access to services increases year after year.

By assuming a social-ecological framework of analysis,9 the Place4Carers (P4C) project will disentangle the role of spaces and their inter-related dynamics in the ageing process.

Ageing space as ecosystem: the uniqueness of ageing in rural and remote areas

In the Italian context, compared to other European countries, the elderly are becoming a prominent feature of the population, especially in rural and remote areas.10 Literature suggests that inequities in access to healthcare systems for older people in rural and remote populations are more frequent compared with access in urban areas.11 Ageing societies present many challenges for the healthcare system, particularly in rural and remote areas where workforce shortage and lack of access to specialist services are very frequent. It is interesting to note that scientific literature is less focussed on ageing population in rural and remote areas, even if these areas have more elders than urban areas.12 For these reasons, we can say that research on ageing populations are urban biassed. The need for health and social care-related services in rural and remote areas has not been met by service provision delivered in urban contexts.11 13 14 Research focussing on older persons living at the geographical and social peripheries argue that in policy and economic debates, the local experiences of older persons living in rural and remote communities have often been ignored.15 16 The P4C project aims to address this gap.

Ageing space as mesosystem: opportunity and challenges of the ‘ageing-in-place’ imperative

‘Ageing-in-place’ is a popular term in current ageing policy and is today recognised as a strategic priority for making the ageing process more sustainable for both individuals and societies.17–20 ‘Ageing-in-place’ is defined as ‘remaining living in the community, with some level of independence, rather than in residential care’.21 Some research highlighted that people prefer to age in place1 because it has been shown that this strategy effectively enables older persons to maintain independence, autonomy and meaningful relations in terms of connection to social support, including friends and family.22 23 Promoting the aging-in-place reduces the economic expenditures of public institutions, impacting positively on governments, health and social care organisations, and elders and their family.23 The term ‘place’ has several dimensions that are inter-related: a physical dimension that can be seen and touched like home or neighbourhood; a social dimension involving relationships with people and the ways in which individuals remain connected to others; an emotional and psychological dimension, which has to do with a sense of belonging and attachment; and a cultural dimension, which has to do with older people’s values, beliefs, ethnicity and symbolic meanings. Sustainable communities should offer affordable and holistic services, and a continuum of care to effectively engage elderly and their family in effective and sustainable health and social care, enabling ageing in health in place.

Several interventions and projects both at a national and international level aim to reduce the fragmentation of welfare services by putting citizens—and their needs—at the centre of service delivery. However, a study conducted in Europe24 found that a fragmented system of services was unable to meet the holistic needs of ageing societies, because the integration between social and health services is complex, including problems in interdisciplinary teamwork, financing and legal aspects. Integration of health and social services is on the agenda of many ageing countries.25 Furthermore, in rural and remote context, welfare and social system are often fragmented and poorly accessible, making the ageing-in-place a possible paradigm only with high care out-of-pocket costs for families that have to take care alone of their elders. Few interventions devoted to ageing-in-place are related to digital/telemedicine intervention, without regarding the social aspect of care.26

Ageing space as microsystem: the role of family relationship and caregiving for elderly citizens

Family caregiver engagement is indeed regarded as a key factor for improving the quality and the sustainability of care services for older people.27–32 Several studies have shown that caregivers are the invisible backbone of social and healthcare settings, particularly in rural and remote areas, as they facilitate the integration, especially in areas and communities with limited access to services.33 Despite their unquestionable role in increasing the chance of ageing-in-place for the older people they take care of, the caregivers experience several criticalities such as burden, social isolation and depletion. In fact, caregivers attest to a critical decrease in their quality of life,34 and they report health issues, such as tiredness, insomnia, depression, weight loss or gain, drug use and need for psychological support;35 these issues are frequently reported by women, especially older. The European Commission report on ‘The indirect cost of long-term care’ (2013)36 reveals that situation of psychosocial distress is widespread for caregivers not only in Italy but also in other countries. This is especially the case for caregivers of older people37 and for those who are required to dedicate a significant amount of time to caring activities.37 Actually, the caregivers of older people often become the primary interlocutors for the health and social care services to take decisions over the patients’ therapies and long-term treatments.38

Moreover, caregivers support the compliance to treatments and therapies and they support older persons in managing follow-ups and clinical exams.39 Finally, caregivers are often the primary sources of psychological support and empathy for the care receiver and for whom they represent the main reference. Against this background, research shows that family caregivers who are more engaged in the care of their loved one have more capability to deal with stressful situations such as caregiving, and thus have less anxiety and depression, and better perceived health.40–43 By feeling more empowered and engaged in the caregiving tasks, caregivers might also reach a better work-family balance.

Appropriate engagement and tailored support of caregivers have the potential to improve their experiences and quality of life, and facilitate shared decision making while enhancing the quality of care provided to older persons and reducing the use of unnecessary health and social services,44 as well as increasing the effectiveness of health and social care interventions.45 Furthermore, supporting the role of informal carers (ie, family and friends providing mostly unpaid care to frail seniors) is important to provide an adequate continuum of care between informal and formal care.

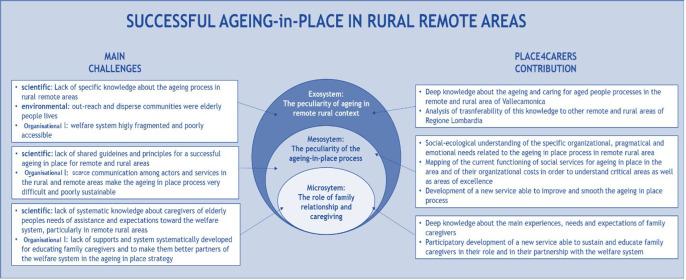

Figure 1.

Describes the threefold social-ecological framework of analysis adopted by Place4Carers.

Aims

The project aims to achieve the following objectives:

to explore, understand and measure caregivers’ needs in terms of education, welfare, assistance and social inclusion, and in relation to the services planned by the local homecare agency, which is responsible for the delivery of basic social services and social assistance towards fragile people in the territory of Vallecamonica;

to assess the cost (both economic and social) sustained by families when caring for their older relatives and to understand the critical aspects faced when accessing and using welfare services that are present in the territory;

to co-produce a new—better accessible and sustainable—service targeting family caregivers of older citizens on the basis of the participative cooperation among family caregivers, older citizens, researchers and welfare system representatives;

to test the transferability of the new service concept in other and similar rural and remote territories of the Lombardy region (Italy).

Methods and analysis

Methodological approach

The proposed study is designed according to a Community Based Participatory Research approach46 47 to engage and capture the perspectives of all the relevant stakeholders involved in the home-based service of long-term care. Thanks to its participatory nature, the P4C project will not only deepen the ageing and caregiving dynamics in the specific outreach territory of Vallecamonica, but also be an innovative co-productive setting, where to engage older citizens, their caregivers and the welfare system will generate ideas for more accessible, effective and economically sustainable welfare services targeting family caregivers.

This approach has the value to be grounded in the needs of communities and of the community-based organisations that serve them. It will allow community transformation and social change by directly engaging target stakeholders and their knowledge in the research process and its outcomes. This is a partnership approach to research that equitably involves community members, organisational representatives and researchers in all the phases of the research process. In this approach, all partners contribute expertise and ownership to reach shared decisions and to make the knowledge produced best rooted in the community experience and more able to be translated into the practice of services development.

In this project, we will mainly focus on the community of Vallecamonica with 41 municipalities and 120 000 inhabitants, 19% of whom are over 65 years old,48 to deepen the unique experiences and needs of family caregivers caring for elderly citizens located in that geographical area. Moreover, the involvement of the local homecare agency (ATSP) will be a key asset in this project, to produce knowledge that is well-integrated with situated interventions and policies, and thus better able to generate social change and improve the health and quality of life of community members. The ATSP is a public agency that coordinates with third parties such as professional social service to deliver services to fragile persons such as old people, families and disabled. Community members, professionals belonging to homecare agency and the researchers will collaborate in all the phases of the project to improve its sustainability and its ability to set the ground not only for a better knowledge production process, but also for the translation of such knowledge into a real opportunity for policy, organisational and social change. We will also guarantee the continuous methodological and scientific supervision of an International Advisory Board to validate the research design and the tools used in the research. An important aspect of this study is to provide insight from all the stakeholders’ perspectives by involving them in all phases of the research process.

Study design

The P4C Research Protocol is articulated in five work packages (WPs), as described in the next paragraphs.

WP1—quantitative survey to define family caregivers’ needs, current services usage and sustained costs

Objectives

This research module is conceived as an extensive assessment on the entire population of family caregivers of elderly people receiving services from the ATSP in Vallecamonica and aims to:

Analyse, quantify and map experiences of unmet needs, and preferences and expectations of support and assistance of family caregivers involved in elderly care, in general and in relation to the specific service offered by ATSP.

Perform a service and costs analysis in order to map the actual use of available services by caregivers and the direct costs sustained by families for elderly care and support.

Identify caregivers to be involved in the participatory phases of the project, specifically those with significant caregiving difficulties.

Tools and methods

A quantitative descriptive survey was designed comprehending measures of caregivers’ needs, levels of engagement and questions to gather information about the direct costs sustained by the families for providing assistance to the elderly (ie, out-of-pocket payments both for the services received by the ATSP and for additional assistance services). The survey was administered by a psychologist at caregivers’ homes. The WP1 started in March 2018 and finished in June 2018.

Sampling

Only family caregivers who had concrete difficulties in the daily care of their care receivers were involved in the survey. We focussed on caregivers whose elders had activated home-based long-term care services from 2 to 12 months49 and had been living in Vallecamonica. Based on this constraint, the research identified five local providers who were offering this type of service in the valley and expressly consented to participate in the project (ie, ATSP and four rest houses). In doing so, the selection criteria were: family caregivers, whose elders have been living at home in Vallecamonica and assisted from 2 to 12 months by one of the five home-based long-term care service providers involved in the project.

The overall number of family caregivers eligible for the study was 321. We asked the five service providers to explain the research and its objectives to all eligible family caregivers and to collect their interest in the project. Since caregivers do not usually have the time nor the interest in explaining their personal condition to unknown parties,50 the sample size of family caregivers that are both eligible and interested in the research was quite limited: 147 caregivers. To increase the response rate, a psychologist contacted (through phone) all the caregivers of the sample to organise with them face-to-face meetings for submitting the survey. Although this approach required time and resources, it reduced the number of bias that arose during the self-administration of the questionnaire. We expected that the large majority of family caregivers have medium-low health literacy and education. Thus, the presence and assistance of a psychologist supported them in understanding and filling the questionnaire correctly, by reducing the number of missing data.51 Based on this approach, we reached a satisfactory response rate of 45%.52 Caregivers involved in WP1 were invited to participate in WP3 for the co-creation of a new service.

Data analysis

Survey data were anonymised, stored in an electronic database and shared with the research partners. The data collected by the survey were analysed with the aim of taking a clear picture of the population of the family caregivers in the area, in terms of psychosocial needs, level of engagement, out-of-pocket expenditures for caregiving activities (eg, drugs, private professional assistance, transportation)53 and cost of time loss for employment, calculated as the time used by the family caregiver in caring activity multiplied by the average cost of an Italian professional caregiver.54 We designed the questionnaire by using tested scales, and clear and familiar terms. The analysis of data was organised into four main steps. First, we performed a preliminary data analysis by computing descriptive statistics, such as mean, median, mode and SD of all variables of the questionnaire. Second, we carried out a confirmatory factor analysis that aimed at confirming the theoretical relationships between factors and their related variables of tested scales used in the questionnaire. Third, we investigated the correlation between psychosocial needs, level of engagement and economic expenditures. Finally, we performed a cluster analysis to identify subgroups of caregivers that had similarities in terms of psychosocial needs, level of engagement and economic expenditures. Overall, this analysis helped us understand the condition of caregivers by developing a taxonomy that clusters caregivers with similar needs, level of engagement and economic expenditures.

WP2—analysis of the literature to map existing initiatives and services for caregiver engagement

Objective

The aim of WP2 was to map the good practices described in the literature related to support and engage family caregivers of elderly people in rural and remote settings. The WP2 started in May 2018, mapping interventions published in scientific articles, and finished in February 2019 with the acceptance of the scoping review in a scientific journal.

Tools and methods

WP2 adopted a scoping review approach as set out by Arksey and O’Malley55.55 We explored the conceptualisation of ageing and of intervention mechanisms adopted to promote caregiver's engagement which oriented such interventions. The following search terms have been adopted: ((caregivers OR family member*) AND (ageing OR elderly* OR old*) OR (patient*) AND (support OR intervention OR programme OR education OR counselling) AND (rural* OR mountain* OR “hard to reach”*)). The terms caregivers and family members were adopted in order to differentiate from professional, paid caregivers. The terms patients and older people were included to indicate the care receiver. Moreover, we included the terms support, intervention, programme, education and counselling to map a broader variety of initiatives. Finally, as our primary interest is in hard to reach areas, we included the terms rural, mountain and hard to reach. We originally included the term remote, but the research did not give any new result, as the notion of remote is still not explored in literature research. We checked qualitatively the results of the search string, reading titles, abstracts and full text.

This scoping review was carried throughout the following scientific databases: Scopus, PsycINFO, CINAHL and PubMed.

Data analysis

For the data analysis, we followed the Arksey and O’Malley approach.55 All articles were merged in a unique Excel database to remove duplicates. Then, titles and abstracts were checked for the inclusion criteria, and in cases of ambiguity, full texts were read to be sure for the inclusion. Moreover, the reference list were screened to identify additional material. Our inclusion criteria were related to data and language of publication, accessibility of full text and focus of intervention, type of caregivers, age of care receivers and context of intervention. Articles published from 2012, recognised European Year of Active ageing, in English and for which the full text was accessible. We decided to start from 2012, considering that year as starting date, and identified 2545 articles, a consistent result. Among all the articles selected, there were no cited previous interventions. Moreover, the focus of the articles must have been on interventions during the planning, piloting, implementation or analysis of the results. Finally, receivers of these interventions must have been informal caregivers of family members. The care receivers, as mentioned before, should be over 60 years old. On the other side, exclusion criteria were applied to articles that reflected on the necessity to provide intervention to caregivers, without providing a service, were not included. Finally, the geographical context of the provided service must be hard to reach area, including rural and remote or mountain area. Articles were analysed at two levels: (1) Intervention characteristics: objective of the intervention, characteristics of the receiver (by type of patient), context of intervention, presence or absence of technologies, individual or group setting, and tools and duration of the intervention. More precisely, the retrieved studies were organised according to their main objective (ie, psychosocial interventions, educational interventions and organisational interventions) following the categorisation of Roter et al.56 (2) Study characteristics: country, study design (randomised controlled trial (RCT), controlled trial (CT), cross‐sectional (CS) and pilot (P)), sample and number of participants, and outcome measures and results.

WP3—co-creation of workshop with caregivers

Objectives

This WP is dedicated to co-design, co-manage and co-assess (together with family caregivers, service providers and researchers) new ideas about a new service. The objectives and features of the new service should able to address caregivers’ needs and expectations that emerged in WP1 and take a cue from the good practices suggested by the results of the scoping literature review in WP2. This analysis is a unique opportunity for discussing with family caregivers the challenges of the aging-in-place imperative in the context of rural and remote areas and co-designing, co-managing and co-assessment along all the phases of the project a possible solution. The WP3 started in July 2018 and is expected to finish by September 2020.

Sampling

Only family caregivers that highlighted their interest in the project during the WP1 are eligible to participate in the co-creation workshops. Thus, the selection criteria were: family caregivers that participate in WP1 and whose elders have been living at home in Vallecamonica and assisted by one of the five home-based long-term care service providers. A psychologist invited caregivers through phone by calling them in random order to arrive at an average of 8 to 10 participants for each workshop. To increase the participation rate, we tried to invite 10 to 12 caregivers at each workshop, knowing that logistical difficulties would often lead to some abandonment. Based on literature suggestions and the sample dimension, we expect to organise a minimum of three to six co-creation workshops in the co-design, co-managing and co-assessment phases of the service cycle.57

Tools and methods

We will carry out co-creation workshops in three main phases of the service life cycle, that is, design, managing and assessment. Each workshop will last about 2 hours and will be conducted by two researchers specifically trained in qualitative research. To include different point of view and enrich the discussions, the workshops will involve both users (family caregivers) and service providers (ATSP). The workshops will be audio-recorded.

In the design phase of the service, we will involve family caregivers to identify their needs and to co-design new services for supporting them. Researchers will facilitate the co-design workshops using the following steps:

Mutual acquaintance: presentation of the project, presentation of participants with their biographical info and description of their role as informal caregiver.

Focus on the needs: what are the difficulties of caregiving in the context of Vallecamonica for them and for their elders.

Insights, ideas for the new service: starting from emerged needs, what are the caregivers’ ideas for a new service, with particular attention to information, educational and psychosocial help.

Conclusion: caregivers, together with the moderator and members of the team of research try to merge ideas for the new service in a unique project idea and define it accurately.

In the managing and assessment phases of the service, we will involve family caregivers to collect their opinions about the service’s activities. While the caregivers’ feedback in the managing phase are used to improve the service’s activities currently underway, in the assessment phase, they will support researchers in assessing the service after its conclusion. Researchers will facilitate the co-managing and co-assessment workshops accomplishing the following steps:

Mutual acquaintance: presentation of the results of ongoing service pilot, highlighting the number of activities, the participation and satisfaction rate of the caregivers involved.

Opinions, feedback on the ongoing service: starting from service’s results, what are the caregivers’ suggestions for improving the ongoing service (ie, co-managing phase) or for assessing the overall service results (ie, co-assessment phase).

Conclusion: caregivers, together with the moderator and members of the team of research try to give practical suggestions for improving the new service both during its implementation and after its conclusion.

Data analysis

All workshops will be transcribed and analysed using content analysis58 59 with an inductive approach.60 Since we investigate a specific phenomenon (ie, ageing-in-place) by observing the behaviours of family caregivers, we prefer to adopt an open and flexible analysis of data.61 We will start coding the transcripts by using an open coding approach and grouping relevant concepts in categories.62 Then, we will investigate the relationships between categories and creating higher-order themes. The coding process will continue until all the relevant insights are coded and data saturation is reached.63 To ensure the reliability of the analysis, two researchers will code the transcripts in parallel, analysing and checking any inconsistency. Then, authors will discuss results and assemble the final set of categories in high-level themes that represent the main concepts of investigation.64 Resulting themes and categories will be compared in term of similarities and differences with the results of WP1 and WP2.65

WP4—piloting and preliminary assessment

Objectives

This WP is dedicated to the testing of the service ideas co-created in WP3 through a piloting action organised and delivered by ATSP. Specifically, the pilot study is aimed at:

Assessing the feasibility and conditions for implementing the service in terms of effort and resources.

Piloting the service.

Evaluating the service.

The WP4 started in April 2019 and is expected to end by September 2020.

Tools and methods

To test service ideas and to ensure the iterative improvement of the pilot, we are using a service prototyping approach.66 Among the several prototyping techniques, we have chosen ‘The Service Prototyping Practical Framework’ that guides researchers in service prototyping process through six steps. First, the research team stated clearly the purpose of the service. Second, the team defined the most suitable and effective way to use the resources and skills for the service’s implementation.67 To achieve this aim, we performed a feasibility study for defining the capabilities and resources needed from legal, economic, operational, technical and scheduling point of view.68 Third, the research team chose the most suitable technique for implementing the service, in line with team and users’ knowledge and competences. Fourth, the team defined the drivers that evaluated the service resolution and quality. We will assess the pilot through a set of quantitative metrics suggested by the existing literature. For each activity of the pilot, we will identify the most appropriate set of indicators. Since the number of participants in this rural and remote area might not be very significant, we will integrate this quantitative data with interviews. Mixing both quantitative and qualitative data in a single study will allow us to improve the understanding of future issues related to the implementation of the pilot.69 We will collect the opinion of the providers of the pilot with individual interviews. Fifth, the project team verified the validity of the service prototyping by using the results of the pilot’s assessment.

Sample

All the caregivers, whose elders are using at least one of the two types of homecare services identified in WP1, were invited to participate to the pilot. We are spreading the project’s activities and meetings through both online and offline channels to include all caregivers who wish to participate. ATSP is in charge of the pilot delivery.

Data analysis

Once we collect the assessment’s results and the users’ opinions on the service, we will try to generalise results by proposing a set of barriers and enablers that may have limited or facilitated the implementation of the pilot. We will start listing all possible barriers and enablers that will arise from the analysis of the pilot. Then, we will compare them in term of differences, similarities, frequency of occurrence and consistency. Finally, we will discuss the final list with the research team and other stakeholders involved in the project to check the reliability of results.

WP5—assessment of transferability to other regions and stakeholder involvement

Objectives

The transferability analysis, intends to make the insights and the idea of the new service better exportable to other similar extra-urban contexts. The transferability is assessed in Valtellina, which is an area geographically close to Vallecamonica and shares the same demographic challenges and similar difficulties in access to assistance and services, with the specific aim to:

Investigate if the needs expressed by the family caregivers in mountainous and outreach communities are similar.

Assess the transferability of the service ideas generated in WP3.

Engage stakeholders in the transferability, by adapting the service idea to the new specific context.

The WP5 started in December 2019 and is expected to end by December 2020.

Tools and methods

The module adopted a mixed-methods design by using a qualitative study to integrate and deepen the previous quantitative one. In the first study, we will give an exploratory survey to the heads of service providers in charge of social and welfare services for elders living in Valtellina. We will involve the heads of service providers because they know the territory and the needs of family caregivers; so, they can give us an objective and valuable opinion on the P4C project and its implementation effectiveness in Valtellina. The survey’s aim is twofold. First, it checks the interests of the local districts in the project by investigating the correspondence with family caregivers’ needs. Second, it intends to understand the future issues that may arise in adopting the project in the new context. Since we do not expect a significant number of respondents, we will integrate survey’s results by organising focus groups with the providers of long-term household care in the districts who express their interest in the study. The aim of this second qualitative study is to collect further insights about possible issues and barriers related to transferability of the project in that area. Based on surveys and focus groups’ results, we will organise a feasibility study that will analyse legal, economic, operational, technical and scheduling constraints.70 In this project, even if we do not deliver a new service in another territorial context, we want to develop the foundation for a transferability plan that could be done in another action research project.

Sample

At the beginning, we will present the pilot’s activities and results to the professionals in charge of social and welfare services of local districts in Valtellina, collecting their interests in the project. We will involve and contact the districts interested in the project to discuss a possible transferability of the service in their territory. For each district that will give us its availability, we will organise a focus group, inviting the operators and staff that are managing and providing long-term household services for elders. The direct involvement and interaction with professionals and operators who might be in charge to create the service will allow us to collect insights for adopting the service in the new context.

Data analysis

Data from surveys and focus group will be triangulated with official and internal documentation related to the welfare systems in Valtellina.71 Results of the assessment of transferability will be verified through interviews with key actors of the local districts of Valtellina for collecting their opinions and checking the reliability of results.

Patient and public involvement

Citizens and members of the public institutions are involved in P4C at various stages of the study. We are holding information/ discussion sessions with key community stakeholders (caregivers, elderly citizens and public institutions) to co-create the envisaged family caregiver services and recommendations across the spectrum of the project. This helps to create a positive and receptive environment for the ultimate implementation of the outputs of the project. The involvement in the research protocol of representatives belonging to both private and public institutions allows us to create synergic exchange between stakeholders having different points of view, and resulting in alignment and cohesion of approach, without compromising independence of any party. In particular, the involvement of ATSP of Vallecamonica in the project guarantees access to the field and a more ‘ecological’ insight on the ageing and caring dynamics in this territory. It also guarantees more concrete applicability of ideas of services developed with the real commitment of the key welfare actors in the territory.

This inclusion of patients/public in this way helps with enhanced recruitment and enables the participants to share their experiences of taking part with others and to underline the importance of the study to people like themselves. Finally, citizens and public representatives are actively involved in disseminating the results of the research.

Project implications and future policy

The P4C’s mission is to enhance and sustain the role of family caregiver in making the ‘ageing-in-place’ imperative a sustainable reality in rural and remote areas. The results of the project will contribute to deliver more value to elderly citizens and health and social system, while making the welfare processes more efficient. Furthermore, by enhancing the skills and the psychological well-being of family caregivers of elderly citizens, the project will also contribute towards improving the quality of life and social inclusion of the care receiver. Existing knowledge on meaningful family caregiver engagement will be aligned, and sustainably implemented through involvement of relevant stakeholders. The P4C project will deliver a transformative network structure and instruments by creating the resources for making the current welfare system more responsive to the needs of elderly citizens and of their family caregivers. To serve this mission, the research is a multi-stakeholder, multilevel and self-sustained project, which will have both short-term and long-term beneficial effects, as outlined below. Furthermore, the long-term impact of the implementation of the sustainability strategy will be, family caregiver engagement will be a common standard in the welfare ecosystem guided by commonly accepted practices. Moreover, the P4C protocol is expected to sensitise family caregiver about the available resources to be activated in the territory and how to make the healthcare/welfare process more fluid and less fragmented. This would also reduce the waste of health and social resources.

Overall, all the stakeholders involved in the project may benefit from each other’s expertise and develop a better understanding of how diverse viewpoints can positively drive and impact successful ageing processes. The impact of this is mutual trust and understanding nurtured by both the P4C results and the participation in the project. The study might have some limitations. The impact of P4C activities should be conceived as local. However, since it includes actions and strategies to assess the generalisability of the insights produced to other extra-urban contexts in Lombardy, we are going to have some insights about results’ exportability.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of both Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore and Politecnico di Milano. Informed consent will be collected from all participants. Data will be treated in anonymised form and only the P4C research team will have access to the data.

The research team will provide a wide dissemination of the key achievements and recommendations to diverse stakeholders through various activities, thus supporting the impact of the project outcomes. Moreover, caregivers will be central to dissemination of the baseline information, which helped to motivate community involvement during and beyond the study.

According to these premises, the aims of the dissemination activities will be: (1) to generate awareness about the concept and the main aims of the project; (2) to ensure strategic and extensive outreach to the ageing research community at large and engage with all other external relevant initiatives and projects to ensure optimal synergy and cross-fertilisation, and avoid duplication of efforts; (3) to identify opportunities to collaborate in developing a cohesive and coherent ecosystem to support possible next phases of the project, its adoption and sustainability.

Potential limitations

The present protocol paper presents at least two possible limitations related to the target population chosen for this study. First, we expect a small sample size in WP1, WP3 and WP4, due to the peculiarity of the rural and remote context that limits the generalisation of the research findings.72 Second, the direct involvement in the design phase of the service may influence its level of innovativeness. Since the target population have medium-low level managerial or technological capabilities, we expect to identify low innovative service solution that may not involve any usage of technology. However, we believe that the investigation of the conditions of family caregivers in rural and remote areas is innovative ‘per se’12 and gives new insights regarding the opinions of this marginalised population that are usually excluded from the regional and national policies.73 By explaining this protocol research, we would like to foster the investigation of marginalised population in rural and remote areas to reduce the social, economic and health discrepancies with the urban areas.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the four local nursing homes, that is, Fondazione O.N.L.U.S. Ninj Beccagutti, Fondazione O.N.L.U.S. 'Villa Mons. Damiano Zani', Fondazione O.N.L.U.S. Angelo Maj and Fondazione O.N.L.U.S. Giovannina Rizzieri for some of the research on which this article is based.

Footnotes

Contributors: GG is the study principal investigator and contributed to develop the study design and write the protocol. SB, NM, CM, EG, AL, MC, VG, CF and RF contributed to develop the study design and write the protocol. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This project has been supported by a grant from Fondazione Cariplo, Italian private foundation (call 'Ricerca sociale - 2017', rif. 2017–0955).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Andrews GJ, Evans J, Wiles JL. Re-spacing and re-placing gerontology: relationality and affect. Ageing Soc 2013;33:1339–73. 10.1017/S0144686X12000621 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valentine G. Social Geographies: space and society. Harlow: Routledge, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiles J. Conceptualizing place in the care of older people: the contributions of geographical gerontology. J Clin Nurs 2005;14:100–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01281.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kadam UT, Croft PR, North Staffordshire GP Consortium Group . Clinical multimorbidity and physical function in older adults: a record and health status linkage study in general practice. Fam Pract 2007;24:412–9. 10.1093/fampra/cmm049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molinari E, Spatola C, Pietrabissa G, et al. The role of Psychogeriatrics in healthy living and active ageing. Stud Health Technol Inform 2014;203:122–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Malderen L, Mets T, De Vriendt P, et al. The active Ageing-concept translated to the residential long-term care. Qual Life Res 2013;22:929–37. 10.1007/s11136-012-0216-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Small N, Bower P, Chew-Graham CA, et al. Patient empowerment in long-term conditions: development and preliminary testing of a new measure. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:263. 10.1186/1472-6963-13-263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alwan A, Armstrong T, Bettcher D, et al. The members of the core writing and coordination team were contributions were also made. Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. Available: http://www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html [Accessed 8 May 2020].

- 9.Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychol 1977;32:513–31. 10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bacsu J, Jeffery B, Abonyi S, et al. Healthy aging in place: perceptions of rural older adults. Educ Gerontol 2014;40:327–37. 10.1080/03601277.2013.802191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phillipson C, Scharf T. Rural and urban perspectives on growing old: developing a new research agenda. Eur J Ageing 2005;2:67–75. 10.1007/s10433-005-0024-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WENGER GC. Myths and realities of ageing in rural Britain. Ageing Soc 2001;21:117–30. 10.1017/S0144686X01008042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Havens B, Hall M, Sylvestre G, et al. Social isolation and loneliness: differences between older rural and urban Manitobans. Can J Aging 2004;23:129–40. 10.1353/cja.2004.0022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kinsella K. Urban and rural dimensions of global population aging: an overview. J Rural Health 2001;17:314–22. 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2001.tb00280.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winterton R, Warburton J. Does place matter? Reviewing the experience of disadvantage for older people in rural Australia. Rural Society 2011;20:187–97. 10.5172/rsj.20.2.187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vasunilashorn S, Steinman BA, Liebig PS, et al. Aging in place: evolution of a research topic whose time has come. J Aging Res 2012;2012:1–6. 10.1155/2012/120952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scharlach A, Graham C, Lehning A. The "Village" model: a consumer-driven approach for aging in place. Gerontologist 2012;52:418–27. 10.1093/geront/gnr083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo KL, Castillo RJ. The U.S. long term care system: development and expansion of naturally occurring retirement communities as an innovative model for aging in place. Ageing Int 2012;37:210–27. 10.1007/s12126-010-9105-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mynatt ED, Essa I, Rogers W. Increasing the opportunities for aging in place. Proceedings on the 2000 conference on Universal Usability, Arlington, 2000:65–71. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonough KE, Davitt JK. It takes a village: community practice, social work, and aging-in-place. J Gerontol Soc Work 2011;54:528–41. 10.1080/01634372.2011.581744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davey J. Ageing in Place’: The Views of Older Homeowners on Maintenance, Renovation and Adaptation. Soc Policy J New Zeal 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clark DO, Frankel RM, Morgan DL, et al. The meaning and significance of self-management among socioeconomically vulnerable older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2008;63:S312–9. 10.1093/geronb/63.5.S312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiles JL, Leibing A, Guberman N, et al. The meaning of "aging in place" to older people. Gerontologist 2012;52:357–66. 10.1093/geront/gnr098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fabbricotti IN. Integrated care in Europe: description and comparison of integrated care in six EU countries. Int J Integr Care 2003:e05. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leichsenring K. Developing integrated health and social care services for older persons in Europe. Int J Integr Care 2004;4:e10. 10.5334/ijic.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Satpathy L. Smart housing: technology to aid aging in PLACE-NEW opportunities and challenges, 2006. Available: http://sun.library.msstate.edu/ETD-db/theses/available/etd-06082006-012243/

- 27.Blumenthal D, Chernof B, Fulmer T, et al. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients - An urgent priority. N Engl J Med 2016;375:909-11. 10.1056/NEJMp1608511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noel MA, Kaluzynski TS, Templeton VH. Quality dementia care: integrating caregivers into a chronic disease management model. J Appl Gerontol 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boehmer KR, Egginton JS, Branda ME, et al. Missed opportunity? Caregiver participation in the clinical encounter. A videographic analysis. Patient Educ Couns 2014;96:302–7. 10.1016/j.pec.2014.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Applebaum A. Isolated, invisible, and in-need: There should be no “I” in caregiver. Pall Supp Care 2015;13:415–6. 10.1017/S1478951515000413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lilly MB, Laporte A, Coyte PC. Labor market work and home care's unpaid caregivers: a systematic review of labor force participation rates, predictors of labor market withdrawal, and hours of work. Milbank Q 2007;85:641–90. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00504.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aronson J, Neysmith SM. The retreat of the state and long-term care provision: implications for frail elderly people, unpaid family carers and paid home care workers. Stud Polit Econ 2016;53:37–66. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caldeira C, Bietz M, Vidauri M, et al. Senior care for aging in place: balancing assistance and independence. Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, CSCW. Association for Computing Machinery, 2017:1605–17. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolff JL, Spillman BC, Freedman VA, et al. A national profile of family and unpaid caregivers who assist older adults with health care activities. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:372–9. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morelli N, Barello S, Mayan M, et al. Supporting family caregiver engagement in the care of old persons living in hard to reach communities: a scoping review. Health Soc Care Community 2019;27:1363–74. 10.1111/hsc.12826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodrigues R, Schulmann K, Schmidt A, et al. The indirect costs of long-term care. Employment, Soc Aff Incl 2013:1–42. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the caregiver health effects study. JAMA 1999;282:2215–9. 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hasselkus BR, Murray BJ. Everyday occupation, well-being, and identity: the experience of caregivers in families with dementia. Am J Occup Ther 2007;61:9–20. 10.5014/ajot.61.1.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beals KP, Wight RG, Aneshensel CS, et al. The role of family caregivers in HIV medication adherence. AIDS Care 2006;18:589–96. 10.1080/09540120500275627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barello S, Castiglioni C, Bonanomi A, et al. The caregiving health engagement scale (CHE-s): development and initial validation of a new questionnaire for measuring family caregiver engagement in healthcare. BMC Public Health 2019;19:1–16. 10.1186/s12889-019-7743-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barello S, Savarese M, Graffigna G. The role of caregivers in the elderly healthcare journey: insights for sustaining elderly patient engagement, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Provenzi L, Barello S, Fumagalli M, et al. A comparison of maternal and paternal experiences of becoming parents of a very preterm infant. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2016;45:528–41. 10.1016/j.jogn.2016.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Provenzi L, Barello S, Graffigna G. Caregiver engagement in the neonatal intensive care unit: Parental needs, engagement milestones, and action priorities for neonatal healthcare of preterm infants In: Patient engagement: a Consumer-Centered model to Innovate healthcare, 2016: 94–107. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blakemore A, Hann M, Howells K, et al. Patient activation in older people with long-term conditions and multimorbidity: correlates and change in a cohort study in the United Kingdom. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:582. 10.1186/s12913-016-1843-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McMullen CK, Schneider J, Altschuler A, et al. Caregivers as healthcare managers: health management activities, needs, and caregiving relationships for colorectal cancer survivors with ostomies. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:2401–8. 10.1007/s00520-014-2194-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goodman MS, Thompson VS, Thompson VS, et al. Community-Based participatory research In: Public health research methods for partnerships and practice, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Page-Reeves J. Community-Based participatory research for health. Health Promot Pract 2019;20:15–17. 10.1177/1524839918809007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Istituto nazionale di statistica Popolazione residente al 1° gennaio : Lombardia, 2019. Available: http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?QueryId=18548 [Accessed 8 May 2020].

- 49.Aging Ni on What is long-term care? U.S. DEP. heal. hum. Serv, 2017. Available: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-long-term-care [Accessed 8 May 2020].

- 50.Hinton L, Guo Z, Hillygus J, et al. Working with culture: a qualitative analysis of barriers to the recruitment of Chinese-American family caregivers for dementia research. J Cross Cult Gerontol 2000;15:119–37. 10.1023/A:1006798316654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Leeuw ED. Reducing missing data in surveys: an overview of methods. Qual Quant 2001;35:147–60. 10.1023/A:1010395805406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakash RA, Hutton JL, Jørstad-Stein EC, et al. Maximising response to postal questionnaires – a systematic review of randomised trials in health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2006;6:1–9. 10.1186/1471-2288-6-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guerriere DN, Coyte PC. The ambulatory and home care record: a methodological framework for economic analyses in end-of-life care. J Aging Res 2011;2011:374237. 10.4061/2011/374237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu M, Guerriere DN, Coyte PC. Societal costs of home and hospital end-of-life care for palliative care patients in Ontario, Canada. Health Soc Care Community 2015;23:605–18. 10.1111/hsc.12170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roter DL, Hall JA, Merisca R, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to improve patient compliance: a meta-analysis. Med Care 1998;36:1138–61. 10.1097/00005650-199808000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guest G, Namey E, McKenna K. How many focus groups are enough? building an evidence base for Nonprobability sample sizes. Field methods 2017;29:3–22. 10.1177/1525822X16639015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Corrao S. Il focus group: Laboratorio sociologico. third. Franco Angeli, 2005. Available: https://www.ibs.it/focus-group-libro-sabrina-corrao/e/9788846421883 [Accessed 9 May 2020].

- 60.Yin RK. The case study as a serious research strategy. Knowledge 1981;3:97–114. 10.1177/107554708100300106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval 2006;27:237–46. 10.1177/1098214005283748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Boyatzis RE. Thematic analysis and code development the search for the Codable moment. Sage, 1998. http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=_rfClWRhIKAC&oi=fnd&pg=PR6&dq=narrative+thematic+analysis&ots=EyvHynfh_k&sig=qbJaepOG0MltWYP0mCHpRczCUus%5Cnhttp://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=_rfClWRhIKAC&oi=fnd&pg=PR6&dq=narrative+thematic+analysis&ots [Google Scholar]

- 63.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research techniques and procedures for developing Grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smebye KL, Kirkevold M, Engedal K. How do persons with dementia participate in decision making related to health and daily care? A multi-case study. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gioia DA, Price KN, Hamilton AL, et al. Forging an identity: an insider-outsider study of processes involved in the formation of organizational identity. Adm Sci Q 2010;55:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Los Angeles: London, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Muurinen H. Service-user participation in developing social services: applying the experiment-driven approach. Eur J Soc Work Serv 2019;22:961–73. 10.1080/13691457.2018.1461071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Passera S, Kärkkäinen H, Maila R. When, how, why prototyping? A practical framework for service development. XXIII ISPIM Conf 2012:16–19. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bausea K, Radimerskya A, Iwanickia M. Feasibility studies in the product development process. Procedia 24th CIRP Design Conference, 2014:473–8. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2011. https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/designing-and-conducting-mixed-methods-research/book241842 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Polit DF, Beck CT. Generalization in quantitative and qualitative research: myths and strategies. Int J Nurs Stud 2010;47:1451–8. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McConnell T, Best P, Davidson G, et al. Coproduction for feasibility and pilot randomised controlled trials: learning outcomes for community partners, service users and the research team. Res Involv Engagem 2018;4:1–11. 10.1186/s40900-018-0116-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Commins P. Poverty and social exclusion in rural areas: characteristics, processes and research issues. Sociol Ruralis 2004;44:60–75. 10.1111/j.1467-9523.2004.00262.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.