Abstract

Surgical innovation and multidisciplinary management have allowed children born with univentricular physiology congenital heart disease to survive into adulthood. There is an estimated global population of 70,000 patients who have undergone the Fontan procedure alive today, most of whom are under 25 years old. There are several unexpected consequences of the Fontan circulation, including Fontan-Associated Liver Disease (FALD). Surveillance biopsies have demonstrated that virtually 100% of these patients develop clinically silent fibrosis by adolescence. As they mature, there are increasing reports of combined heart-liver transplantation due to advanced liver disease including bridging fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma in this population. In the absence of a transplant option, these young patients face a poor quality of life and death. Acknowledging that there are no consensus guidelines for diagnosing and monitoring FALD or when to consider heart-transplant versus combined heart-liver transplantation in these patients, a multidisciplinary working group reviewed the literature surrounding FALD, with a specific focus on considerations for transplantation.

Keywords: Fontan-associated liver disease, heart transplant, combined heart-liver transplant

Introduction

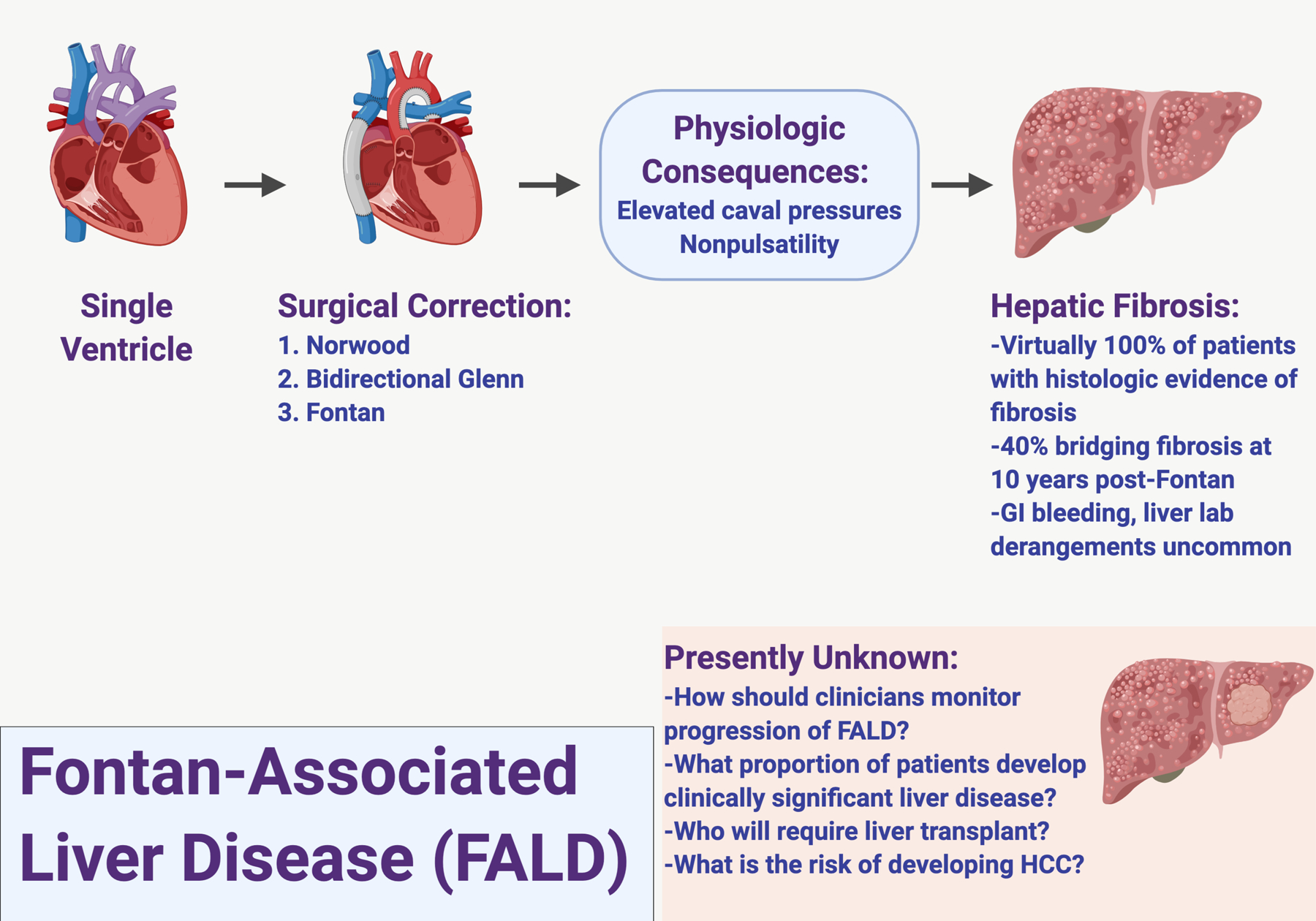

The Fontan operation was first described in 1971 for patients with tricuspid atresia, but has increasingly been applied as final stage surgical palliation for pediatric patients with univentricular physiology heart disease1. As this procedure has gained acceptance and achieved excellent short-term outcomes, it has become evident that most patients post-Fontan develop hepatic fibrosis and even cirrhosis over time, referred to as Fontan-associated liver disease (FALD). FALD is in the spectrum of congestive hepatopathy, related at least in part to chronically elevated central venous pressures and a lack of pulsatility, resulting in passive venous congestion and impaired hepatic blood flow (Figure 1)2. While it is generally accepted that all patients post-Fontan have some degree of FALD, it is unclear what proportion of patients post-Fontan will develop clinically significant advanced liver disease. Similarly, the prevalence of and preferred algorithm to provide surveillance for FALD-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is yet to be determined.

Figure 1:

Fontan-Associated Liver Disease.

Recognizing the challenges of managing patients with FALD and the paucity of guidelines for selection and management of patients for heart transplant alone versus combined heart liver transplant (CHLT), a multidisciplinary group of American Society of Transplantation members collaborated to review FALD specifically from the perspective of the transplant professional. In this article, we provide the epidemiology, clinical diagnosis, and options for monitoring progression of FALD. We also explain the challenges and considerations for patients post-Fontan who may benefit from liver transplant. It is projected that the mean age of patients post-Fontan will be 23 years by 2025, with an estimated global population of 70,000 patients post-Fontan that could double over the next decade. It is therefore imperative that the transplant community proactively develops algorithms for managing patients post-Fontan with FALD3,4.

Brief Review of the Fontan Physiology

Most children born with unrepaired univentricular physiology face an early death during infancy. Due to advancements in surgical technique and perioperative care, these patients can now expect to survive into adulthood. A single, functional ventricle can be found in patients with tricuspid or mitral atresia, hypoplastic left or right heart syndrome, and other rare complex congenital heart disorders where bi-ventricular repair is not possible. Following the Norwood and Glenn procedures, which create a superior cavopulmonary connection, the Fontan procedure involves implantation of a surgical shunt to divert blood from the inferior vena cava and superior vena cava to the pulmonary arteries, without passing through the sub-pulmonic ventricle: a total cavopulmonary connection1. In essence, the systemic and pulmonary circulations are placed in series with the functional single ventricle. The consequence of this total cavopulmonary connection is chronic hepatic venous congestion secondary to high pressure non-pulsatile flow in the inferior vena cava.

The primary characteristic of Fontan hemodynamics is a lack of a subpulmonary ventricle, which automatically leads to high central venous pressure (CVP). This creates additional driving pressure for the pulmonary circulation and diminished cardiac preload for the systemic ventricle (SV), resulting in chronically low cardiac output (CO)1,5. Mild but significant low arterial blood oxygen saturation is also a major hemodynamic feature, which likely results from intrapulmonary ventilation-perfusion mismatch as well as the development of veno-venous collaterals6. Thus, it is postulated that the pathophysiologic complications after the Fontan operation are driven by the following conditions: multi-end-organ congestion due to high central venous pressure (CVP), chronic heart failure due to low CO, and mild but significant hypoxia which over time may contribute to multi-organ dysfunction7. Possible causes of elevated CVP include (but are not limited to) pre-capillary factors, such as stenosis of the Fontan conduit and high pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), or post-capillary factors, like systolic and/or diastolic SV dysfunction and atrioventricular valve regurgitation and/or stenosis.

In the U.S., more than 900 Fontan operations are performed each year, with 97% early survival3. To put that in perspective, there are an estimated 500–600 children born with biliary atresia each year in the U.S., and approximately half will undergo primary liver transplant, which makes up the majority of pediatric liver transplants performed each year8,9. The Fontan operation is usually performed in children two to five years of age, but the effects of the post-Fontan physiology continue to impact these patients through adulthood10. Only one third of adult patients post-Fontan are in ‘optimal condition’, defined as acceptable cardiac function with no clinically evident end-organ disease11. While these results have been encouraging and represent a dramatic survival effect on what was previously considered a terminal patient population, these patients may develop clinically silent liver, kidney, and pulmonary disease as well as chronic systemic inflammation.

Which patients post-Fontan are at risk for FALD?

FALD, including the development of cardiac cirrhosis and liver neoplasms, is recognized to be highly prevalent in patients post-Fontan12–16. Chronic passive congestion of the liver due to the absence of a functional subpulmonic ventricle is likely the chief driver of the hepatic fibrosis and hepatomegaly observed in FALD. Systemic venous pressure elevation due to passive pulmonary blood flow results in elevated systemic venous pressure, causing liver congestion17. Additionally, cardiac output and cardiac index are diminished, and as a result zone three hepatocytes may be compromised by decreased oxygen delivery to centrilobar cells18. Over the long term, systolic performance diminishes19. Shear stress on the hepatic vasculature due to chronic congestion results in reactive fibrogenesis due to centrilobular hepatocyte atrophy, sinusoidal fibrosis and eventual bridging fibrosis and then cardiac cirrhosis20,21.

In a retrospective study at a single center, 13/32 patients post-Fontan evaluated for heart transplant had imaging studies suggestive of cirrhosis (irregular and nodular liver contour, but liver tests did not distinguish among those with and without cirrhosis16. In a prospective assessment of adult patients post-Fontan, most had advanced liver disease. Histologic evidence of fibrosis was present in all biopsies and was classified as severe based on a gross architectural distortion score (modified from METAVIR staging) of 3–4 in 68% of the patients12,22. Complications of portal hypertension including varices and ascites were present in over half of the patients, and the presence of varices correlated with the severity of fibrosis. Liver nodules were detected in more than half of these patients. While the majority of studies describing FALD involve young adult patients, it is important to note that adolescents, particularly those with refractory intrapulmonary shunting and a failing Fontan, may develop evidence of end-stage liver disease much earlier. It is also important to note that both radiographic and histologic findings are incompletely evaluated in FALD and may not accurately represent all aspects of the disease.

Over the last decade, several studies have attempted to identify relationships between hemodynamics and the extent of liver fibrosis in patients post-Fontan. A recent study involving 33 patients post-Fontan who were undergoing routine surveillance liver biopsy and had no clinical signs of chronic liver disease determined that the degree of liver fibrosis on biopsy was independent of total cavopulmonary connection hemodynamics23. This has also been observed in a larger single center cohort of approximately 100 adolescent patients undergoing surveillance cardiac catheterization and liver biopsy ≥ 10 years post-Fontan24,25. Another surveillance cardiac catheterization and liver biopsy cohort involving 49 patients 15.2 years post-Fontan reported that all patients had histologic evidence of liver fibrosis, and Fontan pressure ≥ 14 mmHg and MR elastography liver stiffness >4 kPA were associated with more advanced fibrosis26. In a study involving 46 adult patients with late post-Fontan follow-up (mean 17.8 years), a weak positive correlation between liver stiffness and Fontan pressures was observed27. A retrospective review of invasive hemodynamic right heart cardiac catheterization in 60 adult patients with failing Fontans was recently published28. In the univariate analysis of associations between liver dysfunction and hemodynamic variables, an increase in CVP was associated with the presence of liver disease (as measured by Child-Pugh and Model of End Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores). Notably, except for CVP, none of the hemodynamic measurements were remarkably abnormal in this group, even according to the reference values for subjects with normal biventricular hearts.

There is a lack of robust literature describing a direct relationship between invasive cardiac hemodynamics in patients post-Fontan with confirmed FALD. Multiple surveillance biopsy studies in adolescent patients with no overt evidence of failing Fontan or decompensated chronic liver disease have shown that all patients post-Fontan exhibit some degree of liver fibrosis23,24,26,29. Thus, it should not be assumed that ‘acceptable’ Fontan hemodynamics implies that liver fibrosis will not occur. That being said, several smaller single center studies have suggested that there may be a relationship between hemodynamic cardiac catheterization values and the progression of fibrosis; i.e., high Fontan pressures or increased liver stiffness measurements are associated with more advanced fibrosis23,26–28.

The best methods for surveillance of Fontan hemodynamic status and associated liver health are still being investigated and debated. In many centers, the routine use of right heart catheterization in the management of Fontan patients remains ‘for cause’; i.e. limited to the evaluation of anatomic or structural issues, such as stenosis in the Fontan conduit, that may be amenable to catheter based directed intervention, and to make adjustment to medication regimens as deemed appropriate by clinicians. In parallel, some centers have begun surveillance cardiac catheterization combined with transjugular liver biopsy in all patients 10–15 years post-Fontan with minimal procedural complications, and these studies have shown that the prevalence and severity of FALD-related liver histopathology most strongly correlates with overall time post-Fontan13,15,24–26,29.

Diagnosis and Monitoring Progression of FALD

Serum biomarkers

While FALD is highly prevalent in the Fontan population, it can be a clinical challenge to diagnose and monitor. The value of history or physical examination in identifying progressive, clinically significant liver disease is limited, as the majority of patients will have no detectable abnormalities. In 74 patients 15 years post-Fontan, physical examination identified hepatomegaly in 30%, splenomegaly in 9%, and ascites in 4%30. Liver enzyme evaluation is inadequate in identifying FALD or determining its severity (summarized in Table 1). In a single center series, the only biomarker associated with a high-grade stage of fibrosis (F3–4) and sinusoidal fibrosis was an elevated INR (P = 0.046 and P = 0.018, respectively)30. The MELD score is generally not elevated in patients post-Fontan. The MELD excluding INR (MELD-XI) score has been explored to eliminate the impact of therapeutically elevated INR among patients who are being pharmacologically anticoagulated. In a cohort of 70 patients post-Fontan, the MELD-XI was reported to have a statistically significant correlation with biopsy-proven fibrosis, although a specific MELD-XI threshold was not identified that could indicate advanced fibrosis with high sensitivity and specificity31.

Table 1:

Considerations for diagnostic testing in patients with suspected FALD.

| Investigation | Utility | Problems |

|---|---|---|

| Liver Biopsy | 1) Gold standard for histologic assessment of fibrosis and cirrhosis 2) Transvenous approach allows for simultaneous hemodynamic pressure measurements |

1) Risk for procedural complications (low) 2) No universally accepted scoring criteria 2) Useful for screening for FALD |

| Blood Tests | ||

| Liver Enzymes (ALT, AST) |

Assess for hepatocyte injury/dysfunction | 1) Rarely elevated in stable FALD 2) Do not correlate with degree of fibrosis in FALD |

| ALP, Bilirubin, GGT | Evaluate biliary injury or stasis (ALP, Bilirubin, GGT) | 1) Rarely elevated in stable FALD 2) Elevated GGT across all patients post-Fontan in one case series 3) Do not correlate with degree of fibrosis in FALD |

| INR | Marker of hepatic synthetic dysfunction | Elevated INR correlated with degree of fibrosis in FALD in one case series |

| AFP | Serum tumor marker that may be raised in some patients with HCC | 1) Does not correlate with disease severity in FALD 2) No data regarding proportion of patients with FALD and HCC that have elevated AFP |

| MELD-Na | 1) Determine mortality risk in patients with end-stage liver disease 2) Calculated with INR, Creatinine, Bilirubin, Na, and presence/absence of renal replacement therapy 3) Used for liver transplant waiting list prioritization |

1) Does not correlate with disease severity and is rarely elevated in patients with FALD 2) Can be confounded by systemic anticoagulation in patients post-Fontan |

| MELD-XI | Modified MELD without INR to risk stratify patients with cirrhosis on anticoagulation | Correlated with degree of fibrosis in FALD in one case series |

| Imaging Modalities | ||

| MR Elastography | 1) Assess global liver stiffness 2) Can perform serial studies to evaluate for progression 3) Evaluate for and characterize liver nodules vs. HCC (with contrast phase) 4) Evaluate portal hypertension, identify complex anatomical variations for surgical planning for liver transplant (with contrast phase) |

1) Does not distinguish between passive congestion and fibrosis 2) For high quality liver imaging, patient must be in scanner for at least 30 min. and participate in exam with breath-holding, etc. which may be challenging in pediatric patients or those with a failing Fontan 3) Liver nodules in FALD being evaluated for HCC may be difficult to categorize using OPTN Criteria |

| Shear Wave US Elastography | 1) Assess global liver stiffness 2) Can perform serial studies to evaluate for progression |

1) Does not distinguish between passive congestion and fibrosis 2) Limited utility in patients with ascites |

| Transient Elastography | 1) Assess liver stiffness 2) Can perform serial studies to evaluate for progression |

1) Does not distinguish between passive congestion and fibrosis 2) Limited utility in patients with ascites |

| Ultrasound | 1) Assess liver morphology 2) Evaluate for liver nodules and vascular patency 3) Evaluate for ascites |

1) Difficult to detect small lesions due heterogeneous parenchyma 2) Limited utility in patients with ascites |

| Contrast CT | 1) Assess liver morphology and vascular patency 2) Evaluate for and characterize liver nodules versus HCC 3) Evaluate complex anatomical variations for surgical planning for liver transplant |

1) Radiation exposure 2) Nephrotoxic contrast 3) Liver nodules in FALD being evaluated for HCC may be difficult to categorize using OPTN Criteria |

ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase, AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase, ALP: Alkaline Phosphatase, GGT: gamma-glutamyl transferase, INR: International Normalized Ratio, MELD: Model of End-stage Liver Disease, AFP: Alpha-Fetoprotein, OPTN: Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, HCC: Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Liver imaging approaches for FALD

Several imaging methodologies have been evaluated for their ability to diagnose advanced FALD (summarized in Table 1). In patients with congestive hepatopathy, ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have traditionally been employed to detect findings suggestive of cirrhosis and its complications. A study of 55 patients post-Fontan screened with US imaging found heterogeneous hepatic echotexture or surface or liver surface nodularity in 67% of patients, and this correlated with time from Fontan32. A specific consideration when reviewing cross-sectional imaging in FALD is that the presence of nodularity does not necessary imply underlying cirrhosis. The imaging changes of contrast enhanced CT or MRI in patients post-Fontan include signs of portal hypertension: altered portal venous phase enhancement of the liver periphery when compared with the hilar region, heterogeneous reticular enhancement of the liver parenchyma in the portal venous phase, as well as ascites, venous collaterals, and/or dilated hepatic veins with contrast reflux and intrahepatic venous-venous collaterals33,34.

The Role of Elastography

Elastography, a non-invasive approach to measure liver stiffness, may be useful for patient evaluation and management in the Fontan population. While elastography is not specific for hepatic fibrosis, as it also detects congestive hepatopathy from hepatic venous outflow obstruction, liver stiffness increases as fibrosis progresses35. Currently, three major modalities are employed to assess liver stiffness: MRI elastography, shear wave elastography, and transient elastography. It is important to note that elastography using any of these techniques can be hampered by the presence of ascites.

There are only small case series which have evaluated the performance of imaging and elastography to determine the degree of fibrosis in FALD. A recent study of 38 patients post-Fontan who underwent multiple modalities of hepatic surveillance detected biopsy-confirmed cirrhosis in 29%12. However, neither transient elastography nor MRI elastography were able to discriminate between mild and severe fibrosis. In a separate study of 50 patients post-Fontan who underwent transient elastography plus hemodynamic testing via cardiac catheterization, transient elastography measurements were associated with higher Fontan pressures36. Serial measurements of liver stiffness have been shown to correlate with clinical deterioration and may be useful in monitoring patients over time37. Thus, elastography may be a more useful marker of failing Fontan physiology than severe fibrosis in FALD. Standardizing liver stiffness ranges to account for a combination of congestion and fibrosis may be useful in the Fontan population.

Other liver-related, invasive approaches to monitor FALD

Endoscopy allows for the assessment of esophageal varices and other gastrointestinal pathologies in cirrhosis and may have a role in patients post-Fontan with evidence of liver disease. However, there are few reports detailing the use of screening endoscopy to detect varices in FALD. Chang and colleagues reported that 27% of adult patients at approximately 15 years post-Fontan had esophageal varices on upper endoscopy. Most studies have relied on noninvasive imaging to determine the presence of varices. Cross-sectional imaging helped identify of varices in 19 of 38 adult patients (50%) at a mean of 21 years post-Fontan12. Similarly, a study examining MRI, CT and/or ultrasound data illustrated that 19.2% of adult and pediatric patients had radiographic evidence of varices at an average age of 24 years and an average of 16 years post-Fontan38. The necessity of surveillance endoscopy (versus imaging) for the detection of varices—and the appropriate intervention if varices are noted—remains to be clarified but may be useful in patients with evidence of liver fibrosis.

Utility of Hepatic Venous Pressure Gradients

Hepatic venous pressure gradients (HVPG) are measured as a surrogate measurement of portal hypertension, comparing the wedged hepatic sinusoidal pressure to the unwedged free hepatic venous pressure (HVPG normally 1–5 mmHg). The value of the hepatic venous pressure gradients in FALD is unclear, as small studies have shown an absence of a significant gradient even in patients with confirmed cirrhosis33. Catheter-measured hemodynamic variables more often associated with the outcomes of death or heart transplant in patients post-Fontan include central venous pressures and cardiac index28. It is unknown if further efforts to associate these measures with FALD will provide additional insight.

Liver Biopsy

Liver biopsy remains the gold standard for the detection of advanced fibrosis in FALD12. However, the potential for procedural complications, including bleeding, may discourage its routine use. Notably, a report of 67 patients post-Fontan who underwent 68 liver biopsies identified hemorrhage in 7.4% as the sole complication; one patient required blood transfusions due to hemobilia39. That being said, in a single center’s experience with >100 surveillance biopsies performed during cardiac catheterization approximately 10 years post-Fontan, only one patient had a post-biopsy bleed, which did not require transfusion24,25. Single center experience at a mature adult congenital and transplant center also suggest, as noted above, the risk of transjugular liver biopsy in the post Fontan patient is safe, with limited periprocedural complications40. Traditional staging of portal fibrosis, such as METAVIR, can identify the development of cirrhosis. However, intermediate METAVIR stages of portal fibrosis may not sufficiently describe the overall disease severity of FALD. Due to hepatic venous outflow obstruction in FALD, the degree of centrilobular and sinusoidal fibrosis should also be taken into consideration. Studies have calculated the overall percent collagen deposition using quantitative Sirius red staining, which provides a global interpretation of portal, sinusoidal, and centrilobular fibrosis30. In a group of 67 patients 15 years post-Fontan, 56% demonstrated ≥20% collagen deposition on Sirius red staining of liver biopsy specimens29. Increasingly, the Congestive Hepatic Fibrosis Score is being reported in FALD studies, which may be a more appropriate approach to grade severity of fibrosis in this patient population26,30,39,41. However, unless cirrhosis is confirmed, a biopsy should always be interpreted with caution due to the risk of sampling bias, such that focal areas may be more or less representative of the patient’s overall true degree of fibrosis. Many programs are performing two distinct passes during the biopsy procedure to reduce the effect of sampling bias24,26,29,30,42.

Evaluation of Liver Lesions

Elevated central venous pressures post-Fontan are associated with the growth of hypervascular nodules in the liver33,43,44. Large regenerative nodules and focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) are common and may occur in as many as 20–30% of patients post-Fontan32,43,45,46. Nodules in patients with cirrhosis from any etiology including post-Fontan, should be vigorously evaluated as potential HCC44,47. Two recent retrospective, single center studies have reported rates of 3–15% for development of HCC in FALD, up to 22 years post-Fontan48,49. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) guidelines for HCC surveillance in general recommend US and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) determination every six months50. For patients post-Fontan, the optimal imaging modality remains unclear due to unique liver morphology and vascular characteristics, but AASLD guidelines may be reasonable until a FALD-specific approach is validated. Reports of MRI elastography evaluation have demonstrated an association between elevated liver stiffness and the development of malignant lesions, though it is unclear whether increased fibrosis alone or in combination with the failing Fontan physiology contributes to this finding51. MRI may be helpful in characterizing these tumors, though a liver biopsy is usually necessary as the typical HCC pattern of contrast washout in the delayed venous phase may not be appreciable with a background of congestive hepatopathy52. In particular, distinguishing dysplastic lesions due to underlying FALD from true HCC within the Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System (LiRADS) criteria (which has not been validated in FALD) or the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) guidelines can be extremely challenging53.

The literature makes clear that time post-Fontan is the most important predictor of advanced FALD25,26,28,30. Thus, any hepatic surveillance strategy can likely be infrequent and non-invasive in the first ten years post-Fontan. However, patients 10–15 years post-Fontan may benefit from a systematic approach to testing. As described here, few tests are associated with advanced FALD, and severe fibrosis on a liver biopsy may not in and of itself indicate the need for liver transplantation or an increased risk of liver-related mortality. However, it would be prudent to provide surveillance for liver dysfunction with liver biochemistry, INR testing, and MELD-XI calculation, as well as for malignancy with ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging. Elastography may be helpful to alert the multi-disciplinary team to increased congestive hepatopathy from a failing Fontan and the need to reduce pulmonary pressures. Ideally, these patients should be followed by an integrated multidisciplinary team that includes congenital cardiologists, heart failure cardiologists, cardiac interventionalists, cardiac surgeons, radiologists, and hepatologists to monitor and manage FALD.

Summary and recommendations for FALD surveillance

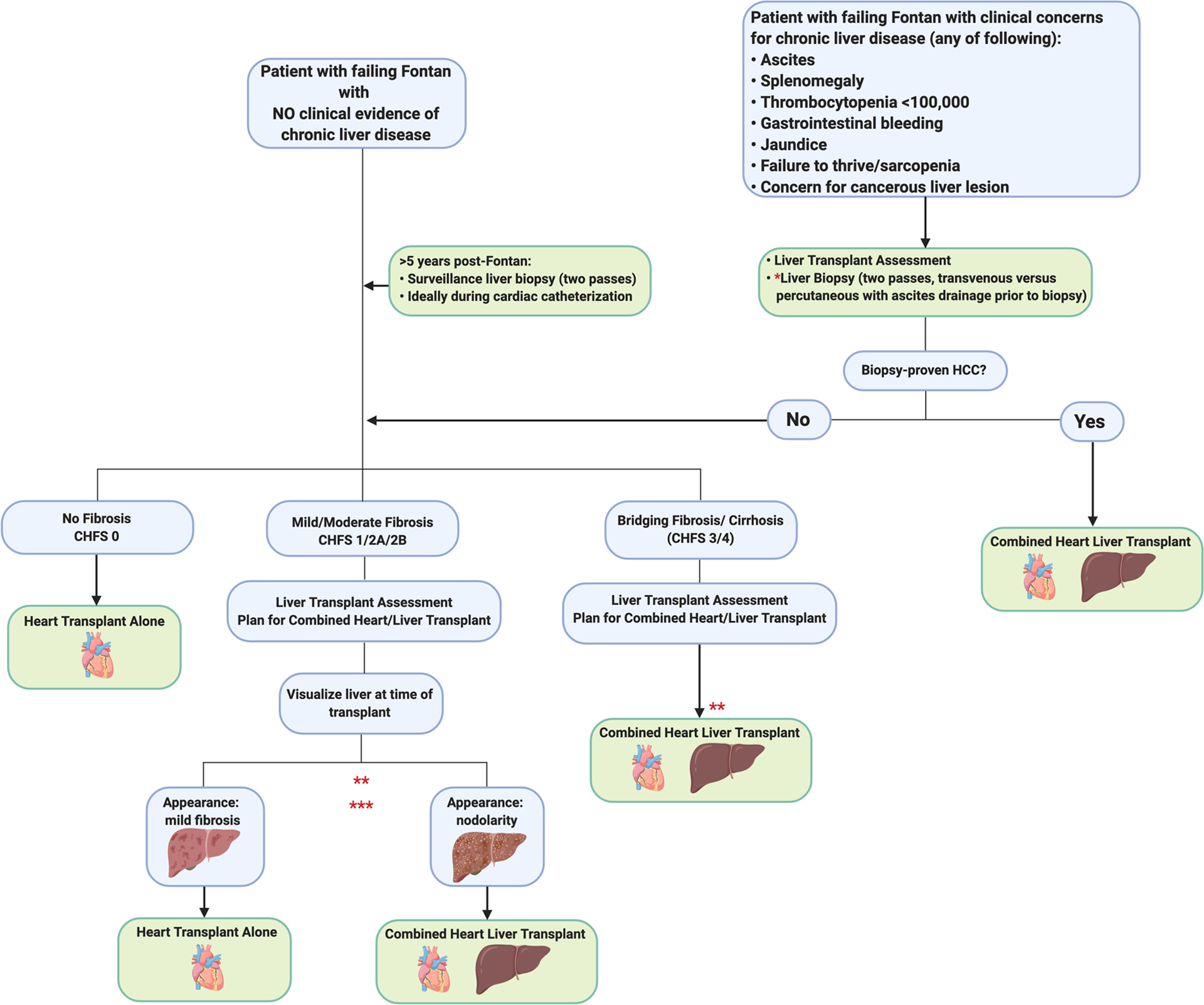

While there have been no comprehensive studies to clearly define the best practice for monitoring development and progression of FALD, we have proposed an algorithm that should capture most patients with FALD based on biopsy findings (Figure 2). Patients without clinical signs and symptoms of chronic liver disease should undergo surveillance biopsy at approximately 10 years post-Fontan, as virtually all patients have been reported to have some evidence of fibrosis at this point and these data will direct further clinical management24,26,29. Based on the severity of the fibrosis on biopsy, these patients should also undergo baseline MR elastography with continued surveillance to determine liver stiffness and also establish initial anatomical features, identify concerning nodules, and evaluate for signs of portal hypertension and splenomegaly. While liver labs alone do not correlate with severity of fibrosis, monitoring these values over time will provide additional perspective for a liver specialist. For patients with evidence of bridging fibrosis and/or cirrhosis, upper endoscopy may be useful to assess for the presence of varices. Interventions for modifiable risk factors for chronic liver disease, including fatty liver (steatosis on biopsy), obesity, hepatotoxic medications, and alcohol use should be considered in all patients with bridging fibrosis and cirrhosis. Screening for HCC is particularly challenging, but serial US and AFP measurements to assess changes over time according to AASLD guidelines is reasonable until FALD-specific approaches can be proven. Finally, for patients with concern for decompensating chronic liver disease, including the presence of ascites, splenomegaly, thrombocytopenia <100,000, gastrointestinal bleeding, jaundice, or failure to thrive/sarcopenia, collaboration with hepatology will be important to fully assess the severity of liver disease and consider referral for liver transplant evaluation.

Figure 2: Approach to surveillance of FALD.

Caveats: MR may be challenging in patients with pacemaker devices, and shearwave elastography for liver stiffness and CT abdomen/pelvis with contrast to assess for stigmata of portal hypertension can be considered in these patients. Transvenous biopsy may be safer than percutaneous approach for patients at higher risk of bleeding (blood thinners, thrombocytopenia, etc). There are no validated modalities or criteria for diagnosing HCC in the setting of FALD. Current HCC screening guidelines from the AASLD recommend AFP and US every six months in patients with cirrhosis.

When does FALD require liver transplantation?

Once high-grade fibrosis is observed in a patient post-Fontan, strategies can be implemented to lower right sided heart pressures and improve hepatic venous outflow. What remains unclear is how to correlate degree of fibrosis with the risk of progression to decompensated cirrhosis and need for liver transplantation (Figure 3). Furthermore, it is uncertain how to predict which patients can stabilize or even regress their hepatic fibrosis following heart transplantation alone, versus those who may unexpectedly decompensate their liver disease post-heart transplant alone, which represents the most feared early-postoperative outcome in these patients. Even with a ‘perfect’ Fontan, liver transplant alone in this population is not advisable due to the inability to manage or control elevated right-sided pressures, particularly during the anhepatic and reperfusion phases of the procedure. However, several centers have reported excellent outcomes for CHLT in patients post-Fontan (summarized in Table 2)40,54–58.

Figure 3:

Transplant Considerations for patients post-Fontan.

Table 2:

Reported experience of Heart Transplant Alone and Combined Heart-Liver Transplant in patients with FALD.

| Heart Transplant Alone | |||||||

| Italy | 2004 | 14 | 10.3 | 86% | 50% | No data if CLD was exclusion criteria | 59 |

| New York, NY USA | 2004 | 24 | 6.1 | 71.5 | N.R. | No data if CLD was exclusion criteria | 60 |

| Delaware, USA | 2012 | 43 | 8.6 | 62.4 | N.R. | No data if CLD was exclusion criteria | 61 |

| Chicago, IL USA | 2013 | 22 | 7.1 | 77 | N.R. | No data if CLD was exclusion criteria | 62 |

| Europe | 2015 | 61 | 10.7 | 81.9 | N.R. | No data if CLD was exclusion criteria | 63 |

| Atlanta, GA USA | 2016 | 33 | 8.8 | 84.8 | N.R. | Excluded patients with CLD 2 episodes of ACR per Pt. in Year 1 |

64 |

| St. Louis, MO USA | 2016 | 47 | 7.1 | 90 | N.R. | No data if CLD was exclusion criteria | 65 |

| Los Angeles, CA USA | 2017 | 36 | 13.0 | 75 | N.R. | No data if CLD was exclusion criteria | 66 |

| Boston, MA USA | 2017 | 30 | 7.5 | N.R. | No data if CLD was exclusion criteria | 67 | |

| PHTS Registry (US, Canada, UK) | 2017 | 252 | 6.7 | 89% | N.R. | No data if CLD was exclusion criteria | 68 |

| Switzerland | 2018 | 1 | 14 | 100% | 0% | Child-Pugh A. Listed for heart only. Plan for urgent liver listing if post-op. decompensation. Regression of bridging fibrosis 18mo. post-transplant | 69 |

| Combined Heart-Liver Transplant | |||||||

| Pittsburgh, PA USA | 2011 | 1 | 15 | 100% | 0% | Situs ambiguous; Reported alive with no ACR at 2 years post-transplant | 70 |

| Omaha, NB USA | 2014 | 1 | N.R., Tx at 18yr. | 100% | 0% | Transplanted across positive T and B-cell XM | 71 |

| Mayo Clinic, MN, USA | 2016 | 4** | N.R. | 86.4%* | 31.8%* | *Survival and rate of ACR include 19 non-Fontan patients. ACR rates may include patients >1-year post-transplant | 54 |

| Newcastle, UK | 2017 | 1 | 41 | 100% | 0% | Explant with cirrhosis, multiple dysplastic nodules, no HCC | 56 |

| Los Angeles, CA, USA | 2018 | 5 | 26.8 | N.R. | N.R. | Study published when 3/5 < 1-year post-transplant | 15 |

| Stanford, CA, USA | 2019 | 9 | 16.6 | 100% | 0% | En bloc heart-liver transplantation | 58 |

| Philadelphia, PA USA | 2019 | 11 | 22.9 | 100% | 9.1% | ACR data is includes non-Fontan patients and may extend >1-year post-transplant | 40,55 |

PHTS: Pediatric Heart Transplant Society, CLD: Chronic Liver Disease, ACR: Acute Cellular Rejection; N.R. Not Reported.

One additional Fontan CHLT since this publication (T.T., personal communication)

The impact of FALD on graft and patient survival following heart transplant alone is limited. Since histologic evidence of fibrosis in FALD is typically observed at least 10 years post-Fontan, the discussion surrounding proceeding with heart transplant alone in the setting of underlying FALD generally refers to late adolescent or adult transplant candidates, as opposed to pediatric patients who proceed to heart transplant alone within a few years of the Fontan. These children can achieve acceptable long-term outcomes, presumably with minimal risk for progression of FALD post-heart transplant, although there is very little data surrounding chronic liver disease as an exclusion criteria for proceeding with heart transplant alone (Table 2)18,64. A retrospective review of a single institutional experience with heart transplant alone in 30 pediatric patients post-Fontan demonstrated an overall 30% mortality at 4.8 years post-transplant, with no mortalities related to liver etiology72. Unfortunately, in the United States there are no diagnostic codes in the OPTN heart dataset that specifically captures patients post-Fontan. Similarly, there are no diagnostic codes to capture FALD in the OPTN liver dataset. Instead, a code for “Congenital Heart Disease with Surgery” has been used a surrogate marker to study these patients from the heart dataset57. In this study, there were approximately 900 patients in the ‘Congenital Heart Disease with Surgery’ category that underwent heart transplant alone, while there were 27 who underwent CHLT. In both circumstances, patients with congenital heart disease had a higher early mortality with superior long-term survival when compared to non-congenital heart disease heart transplant alone recipients. In a recent analysis of the OPTN data, there were ten patients with a history of heart transplant for ‘Congenital Heart Disease with Surgery’ who were subsequently placed on the liver transplant waitlist. Only one pediatric patient ultimately received a liver transplant, and 4/6 (67%) of the adult patients died on the liver transplant waitlist73.

There is some evidence that FALD can stabilize following heart transplant alone. In a retrospective histological study of 74 patients post-Fontan, with five who underwent heart transplant alone, the degree of pre-transplant hepatic fibrosis was not predictive of heart transplant-free survival or overall survival74. In another series of 20 patients post-Fontan who received a heart transplant alone, one-year survival was not affected by the presence of pre-existing cirrhosis, although the average time interval between Fontan and heart transplant was only 8.5 years in this study16. A recent case report from Switzerland described a 24-year-old patient with Childs-Pugh A cirrhosis who underwent heart transplant alone 14 years post-Fontan. They report histological evidence of regression of bridging fibrosis 18 months post-transplant, suggesting that this phenomenon is possible although this may represent sampling bias69. Importantly, this team proceeded with heart transplant alone with a mechanism in place to list the patient for urgent liver transplant should he experience hepatic decompensation post-operatively. It remains to be determined what the long-term risk of developing HCC will be in the heart transplant alone post-Fontan patient population, as it well-recognized that HCC can still occur in the absence of frank cirrhosis and even following regression of other chronic liver diseases75.

CHLT is one of the rarest multivisceral transplants reported in the OPTN dataset, and as stated above there is no way to know with certainty the proportion of patients who had a history of Fontan76. However, there are several recent single-institution series of CHLT, including patients post-Fontan, that provide intriguing results. Stanford has reported their experience with en bloc CHLT in nine adolescent and adult patients post-Fontan since 2006, with 100% one year patient survival and 0% rejection episodes at 30 days and one year post-transplant58. The Mayo Clinic has reported their experience between 2004–2013 with 22 CHLT compared to 223 heart transplant alone, with three of the CHLT patients having a diagnosis of congenital heart disease, post-Fontan54. In this series, the overall survival for CHLT versus heart transplant alone were similar, while CHLT resulted in a significant decrease in T-cell mediated rejection confirmed by routine surveillance endocardial biopsies, despite similar immunosuppression (31.8% for CHLT vs. 84.8% for heart transplant alone, p<0.0001). Recently, the University of Pennsylvania reported their experience, with 33 CHLT versus 283 heart transplant alone; 11 patients post-Fontan were included in the CHLT cohort40,55. There was a similar finding with regards to reduced acute cellular rejection, with only 9.1% of CHLT patients experiencing a rejection episode, versus 42.7% of the heart transplant alone patients. Taken together, it is clear that excellent, if not superior outcomes can be achieved for patients post-Fontan that undergo CHLT versus heart transplant alone, and there may be an immunologic benefit to proceeding with CHLT with significantly less acute cellular and humoral rejection episodes.

The most challenging aspect to proceeding with CHLT versus heart transplant alone is patient selection. The University of Pennsylvania transplant team reports that they decide at the time of transplant via direct visualization of the recipient native liver whether to proceed with CHLT. They have also reported discordant explant histology when compared to pre-transplant liver biopsy, with approximately 30% of patients exhibiting more advanced fibrosis on explant (K.O. and J.W., unpublished data). As well, they have proceeded with listing two patients for CHLT based on the diagnosis of HCC, versus the decision being based on a failing Fontan. Ultimately the decision of the multidisciplinary transplant team will be driven by both by biopsy and clinical findings, as well as the presence or absence of malignancy (considerations outlined in Figure 4). Given the potential immunologic benefit of CHLT, programs may consider the degree of HLA allosensitization in their decision to proceed with heart transplant alone versus CHLT. The frequency of HLA allosensitization has not been reported for patients post-Fontan specifically, but up to 20% of patients with congenital heart disease are reportedly sensitized, presumably secondary to the transfusion requirement associated with multiple cardiac procedures77. There are data that CHLT can overcome antibody mediated rejection, and thus it is possible that in the highly sensitized Fontan patient with mild to moderate FALD, proceeding with CHLT will result in the best overall outcome for that patient and allow for transplant candidacy in a patient who may be deemed unacceptable risk for heart transplant alone78.

Figure 4: Algorithm for Heart Transplant Alone vs. Combined Heart-Liver Transplant in Patients with FALD.

Caveats: *Transvenous biopsy may be safer than percutaneous approach for patients at higher risk of bleeding (blood thinners, thrombocytopenia, etc). **Decision making for patients with histologic evidence of bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis whose liver disease remains compensated is complex and will require multidisciplinary discussion and further study. ***There may be immunologic benefit of CHLT for patients with high PRA. This has not been studied in patients post-Fontan.

Moving forward with CHLT in the Fontan patient: Anesthetic Considerations

The anesthetic management of CHLT in a patient with Fontan circulation is exceedingly complex. Hemodynamic instability, large-volume blood loss, coagulopathy, and metabolic derangements are commonplace. To complicate matters further, patients post-Fontan have unique anesthetic management goals due to their distinctive anatomy79. Among the most important is the maintenance of a transpulmonary pressure gradient (CVP – atrial pressure) to promote pulmonary blood flow. Since there is no active pumping of blood through the lungs, CO is dependent on passive pulmonary blood flow. A satisfactory transpulmonary gradient is reliant upon several factors: 1) adequate preload, 2) minimized PVR, 3) satisfactory ventricular function, 4) proper AV valve function, and 5) sinus rhythm80,81.

Assuming a normal atrial pressure of 5–10 mmHg, a CVP of 12–15 mmHg should promote adequate forward flow80–82. Positive pressure ventilation, though unavoidable for this operation, is not often well-tolerated. The loss of sinus rhythm requires prompt correction and can lead to ventricular failure82. Hypoxia is not uncommon in patients post-Fontan with fenestrated patients often having a baseline SpO2 that falls in the 80% range. In CHLT, it is more common that cardiac transplantation precedes liver transplantation and cardiopulmonary bypass is commonly weaned prior to liver transplantation15,56,83. Adequate cardiac function is essential to limit hepatic congestion. Depending on an individual center’s practice, it is likely that these patients will be transferred to the cardiac surgery intensive care unit post-operatively, with a multidisciplinary approach to post-transplant management.

Conclusions and future directions

In summary, FALD increasingly poses a significant clinical challenge. Without discrete International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes for ‘history of Fontan’ or ‘FALD’, it will be virtually impossible to study these patients over time and determine the lifetime risk of clinically significant chronic liver disease and the need for liver transplant73. In the short-term, the establishment of multi-institutional, collaborative registries with liver-specific outcome measures is imperative to develop evidence-based management guidelines. Prospective studies aimed at correlating liver biopsy findings and imaging features that can adequately diagnose FALD are necessary. Further, routine monitoring for liver disease starting at 10 years post Fontan surgery is recommended. Similarly, defining imaging findings that correlate with malignant liver lesions in the setting of FALD specifically will be important to monitor for HCC and define OPTN transplant criteria in these patients.

With over 70,000 patients post-Fontan worldwide now reaching adulthood, our community will face increased decisions about when to proceed with transplant and what the role is for CHLT. In the present OPTN dataset, there is no way to study patients post-Fontan or FALD directly. Adopting a policy change so that these diagnoses can be tracked moving forward will provide crucial data in understanding this population in the context of solid organ transplantation. Hepatic fibrosis will develop in all patients post-Fontan, and thus surveillance for FALD is a question of “when” and not “if.” Based on the current data, the most reliable method to diagnose FALD requires liver biopsy, but large, multicenter studies and further refinement of MELD-XI scoring and elastography techniques may allow for multiple non-invasive data points to be generated and facilitate surveillance of FALD over time. Similarly, the potential for stabilization and/or regression of FALD following heart transplant alone exists but is difficult to predict and may not eliminate the risk for HCC. Most centers would not consider liver transplant alone in patients post-Fontan feasible due to chronic elevation of central venous pressures, and OPTN data demonstrate high mortality for heart transplant recipients who are subsequently placed on the liver transplant waiting list. That being said, recent data suggest that superior outcomes can be achieved with CHLT in this patient population when compared to heart transplant alone, with additional immunologic benefit. It is evident that MELD-Na does not adequately capture FALD, and with the challenges in diagnosing HCC in these patients, it may be difficult for a patient with stable or worsening FALD following heart transplant alone to receive a subsequent liver transplant. With the current allocation policy for CHLT, where the liver follows the heart, CHLT may be the only chance for these patients to receive a liver transplant. Proceeding with CHLT requires an experienced transplant center, collaborative team, and dedicated anesthesiology group that can embrace the unique challenges of transplantation in patients post-Fontan.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript is a work product completed by the FALD Research Group that formed out of the American Society of Transplantation Liver and Intestinal Transplant Community of Practice. Figures were generated using Biorender.com.

Funding Sources: J.E. was supported by an Investigator Research Supplement from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01 HL141857-01.

Non-standard abbreviations and acronyms:

- FALD

Fontan-Associated Liver Disease

- CHLT

Combined Heart-Liver Transplant

- CVP

Central Venous Pressure

- CO

Cardiac Output

- PVR

Pulmonary Vascular Resistance

- MELD

Model of End-Stage Liver Disease

- US

Ultrasound

- CT

Computed Tomography

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- AFP

Alpha-fetoprotein

- AASLD

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

- HCC

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- ALT

Alanine Aminotransferase

- AST

Aspartate Aminotransferase

- ALP

Alkaline Phosphatase

- GGT

gamma-glutamyl transferase

- INR

International Normalized Ratio

- PHTS

Pediatric Heart Transplant Society

- CLD

Chronic Liver Disease

- ACR

Acute Cellular Rejection

- NR

Not Reported

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None

References

- 1.Cowgill LDD. The fontan procedure: A historical review. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991;51:1026–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon-Walker TT, Bove K, Veldtman G. Fontan-associated liver disease: A review. J Cardiol. 2019;74:223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs JP, Mayer JE, Mavroudis C, O’Brien SM, Austin EH, Pasquali SK, Hill KD, Overman DM, St. Louis JD, Karamlou T, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database: 2017 Update on Outcomes and Quality. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103:699–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schilling C, Dalziel K, Nunn R, Du Plessis K, Shi WY, Celermajer D, Winlaw D, Weintraub RG, Grigg LE, Radford DJ, et al. The Fontan epidemic: Population projections from the Australia and New Zealand Fontan Registry. Int J Cardiol. 2016;219:14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohuchi H Adult patients with Fontan circulation: What we know and how to manage adults with Fontan circulation? J Cardiol. 2016;68:181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohuchi H, Ohashi H, Takasugi H, Yamada O, Yagihara T, Echigo S. Restrictive Ventilatory Impairment and Arterial Oxygenation Characterize Rest and Exercise Ventilation in Patients After Fontan Operation. Pediatr Cardiol. 2004;25:513–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohuchi H Where Is the “Optimal” Fontan Hemodynamics? Korean Circ J. 2017;47:842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LeeVan E, Matsuoka L, Cao S, Groshen S, Alexopoulos S. Biliary-Enteric Drainage vs Primary Liver Transplant as Initial Treatment for Children With Biliary Atresia. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopkins PC, Yazigi N, Nylund CM. Incidence of Biliary Atresia and Timing of Hepatoportoenterostomy in the United States. J Pediatr. 2017;187:253–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gewillig M, Brown SC. The Fontan circulation after 45 years: update in physiology. Heart. 2016;102:1081–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lastinger L, Zaidi AN. The Adult With a Fontan: A Panacea Without a Cure? Circ J. 2013;77:2672–2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munsterman ID, Duijnhouwer AL, Kendall TJ, Bronkhorst CM, Ronot M, van Wettere M, van Dijk APJJ, Drenth JPHH, Tjwa ETTLTL, van Dijk APJJ, et al. The clinical spectrum of Fontan-associated liver disease: Results from a prospective multimodality screening cohort. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:1057–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rathgeber SL, Harris KC. Fontan-Associated Liver Disease: Evidence for Early Surveillance of Liver Health in Pediatric Fontan Patients. Can J Cardiol. 2019;35:217–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Téllez L, Rodríguez de Santiago E, Albillos A. Fontan-associated Liver Disease. Rev Española Cardiol (English Ed). 2018;71:192–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reardon LC, DePasquale EC, Tarabay J, Cruz D, Laks H, Biniwale RM, Busuttil RW, Kaldas FM, Saab S, Venick RS, et al. Heart and heart-liver transplantation in adults with failing Fontan physiology. Clin Transplant. 2018;32:e13329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simpson KE, Esmaeeli A, Khanna G, White F, Turnmelle Y, Eghtesady P, Boston U, Canter CE. Liver cirrhosis in Fontan patients does not affect 1-year post-heart transplant mortality or markers of liver function. J Hear Lung Transplant. 2014;33:170–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rychik J, Veldtman G, Rand E, Russo P, Rome JJ, Krok K, Goldberg DJ, Cahill AM, Wells RG, Rand E, et al. The Precarious State of the Liver After a Fontan Operation: Summary of a Multidisciplinary Symposium. Pediatr Cardiol. 2012;33:1001–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanter KR, Mahle WT, Vincent RN, Berg AM, Kogon BE, Kirshbom PM. Heart Transplantation in Children With a Fontan Procedure. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:823–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakamura Y, Yagihara T, Kagisaki K, Hagino I, Kobayashi J. Ventricular Performance in Long-Term Survivors After Fontan Operation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:172–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hilscher MB, Johnson JN, Cetta F, Driscoll DJ, Poterucha JJ, Sanchez W, Connolly HM, Kamath PS. Surveillance for liver complications after the Fontan procedure. Congenit Heart Dis. 2017;12:124–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wells ML, Fenstad ER, Poterucha JT, Hough DM, Young PM, Araoz PA, Ehman RL, Venkatesh SK. Imaging Findings of Congestive Hepatopathy. RadioGraphics. 2016;36:1024–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kendall TJ, Stedman B, Hacking N, Haw M, Vettukattill JJ, Salmon AP, Cope R, Sheron N, Millward-Sadler H, Veldtman GR, et al. Hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis in the Fontan circulation: a detailed morphological study. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:504–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trusty PM, Wei Z, Rychik J, Russo PA, Surrey LF, Goldberg DJ, Fogel MA, Yoganathan AP. Impact of hemodynamics and fluid energetics on liver fibrosis after Fontan operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;156:267–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emamaullee J, Yanni G, Kohli R, Kumar SR, Starnes V, Badran S, Patel N. Impact of Sex, Ethnicity, and Body Mass Index on Progression of Fibrosis in Fontan-Associated Liver Disease. Hepatology. 2019;70:1869.31034631 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel ND, Sabati A, Hill A, Williams R, Takao C, Badran S. Surveillance catheterization is useful in guiding management of asymptomatic Fontan patients. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;91:04. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silva‐Sepulveda JA, Fonseca Y, Vodkin I, Vaughn G, Newbury R, Vavinskaya V, Dwek J, Perry JC, Reshamwala P, Baehling C, et al. Evaluation of Fontan liver disease: Correlation of transjugular liver biopsy with magnetic resonance and hemodynamics. Congenit Heart Dis. 2019;14:600–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alsaied T, Possner M, Lubert AM, Trout AT, Szugye C, Palermo JJ, Lorts A, Goldstein BH, Veldtman GR, Anwar N, et al. Relation of Magnetic Resonance Elastography to Fontan Failure and Portal Hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2019;124:1454–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mori M, Hebson C, Shioda K, Elder RW, Kogon BE, Rodriguez FH, Jokhadar M, Book WM. Catheter-measured Hemodynamics of Adult Fontan Circulation: Associations with Adverse Event and End-organ Dysfunctions. Congenit Heart Dis. 2016;11:589–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldberg DJ, Surrey LF, Glatz AC, Dodds K, O’Byrne ML, Lin HC, Fogel M, Rome JJ, Rand EB, Russo P, et al. Hepatic Fibrosis Is Universal Following Fontan Operation, and Severity is Associated With Time From Surgery: A Liver Biopsy and Hemodynamic Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e004809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Surrey LF, Russo P, Rychik J, Goldberg DJ, Dodds K, O’Byrne ML, Glatz AC, Rand EB, Lin HC. Prevalence and characterization of fibrosis in surveillance liver biopsies of patients with Fontan circulation. Hum Pathol. 2016;57:106–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans WN, Acherman RJ, Ciccolo ML, Carrillo SA, Galindo A, Rothman A, Winn BJ, Yumiaco NS, Restrepo H. MELD-XI Scores Correlate with Post-Fontan Hepatic Biopsy Fibrosis Scores. Pediatr Cardiol. 2016;37:1274–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bae JM, Jeon TY, Kim JSJHJS, Kim S, Hwang SM, Yoo S-YY, Kim JSJHJS. Fontan-associated liver disease: Spectrum of US findings. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85:850–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiesewetter CH, Sheron N, Vettukattill JJ, Hacking N, Stedman B, Millward-Sadler H, Haw M, Cope R, Salmon AP, Sivaprakasam MC, et al. Hepatic changes in the failing Fontan circulation. Heart. 2007;93:579–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song J, Kim K, Huh J, Kang I-S, Kim SH, Yang J-H, Jun TG, Kim JH. Imaging Assessment of Hepatic Changes after Fontan Surgery. Int Heart J. 2018;59:1008–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yeh W-CC, Li P-CC, Jeng Y-MM, Hsu H-CC, Kuo P-LL, Li M-LL, Yang P-MM, Po HL, Lee PH. Elastic modulus measurements of human liver and correlation with pathology. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2002;28:467–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu FM, Opotowsky AR, Raza R, Harney S, Ukomadu C, Landzberg MJ, Valente AM, Breitbart RE, Singh MN, Gauvreau K, et al. Transient Elastography May Identify Fontan Patients with Unfavorable Hemodynamics and Advanced Hepatic Fibrosis. Congenit Heart Dis. 2014;9:438–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Egbe A, Miranda WR, Connolly HM, Khan AR, Al-Otaibi M, Venkatesh SK, Simonetto D, Kamath P, Warnes C. Temporal changes in liver stiffness after Fontan operation: Results of serial magnetic resonance elastography. Int J Cardiol. 2018;258:299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elder RW, McCabe NM, Hebson C, Veledar E, Romero R, Ford RM, Mahle WT, Kogon BE, Sahu A, Jokhadar M, et al. Features of portal hypertension are associated with major adverse events in Fontan patients: The VAST study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:3764–3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Srinivasan A, Guzman AK, Rand EB, Rychik J, Goldberg DJ, Russo PA, Cahill AM. Percutaneous liver biopsy in Fontan patients. Pediatr Radiol. 2019;49:342–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.D’Souza BA, Fuller S, Gleason LP, Hornsby N, Wald J, Krok K, Shaked A, Goldberg LR, Pochettino A, Olthoff KM, et al. Single-center outcomes of combined heart and liver transplantation in the failing Fontan. Clin Transplant. 2017;31:e12892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adani GL, Rossetto A, Bresadola V, Baccarani U, Adani GL, Lorenzin D, Bresadola V, Terrosu G, Davis GL, Alter MJ, et al. Positive HBcAb is associated with higher risk of early recurrence and poorer survival after curative resection of HBV-related HCC. J Hepatol. 2015;62:3. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu FM, Kogon B, Earing MG, Aboulhosn JA, Broberg CS, John AS, Harmon A, Sainani NI, Hill AJ, Odze RD, et al. Liver health in adults with Fontan circulation: A multicenter cross-sectional study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:656–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bryant T, Ahmad Z, Millward-Sadler H, Burney K, Stedman B, Kendall T, Vettukattil J, Haw M, Salmon AP, Cope R, et al. Arterialised hepatic nodules in the Fontan circulation: Hepatico-cardiac interactions. Int J Cardiol. 2011;151:268–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asrani SK, Asrani NS, Freese DK, Phillips SD, Warnes CA, Heimbach J, Kamath PS. Congenital heart disease and the liver. Hepatology. 2012;56:1160–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wallihan DB, Podberesky DJ. Hepatic pathology after Fontan palliation: Spectrum of imaging findings. Pediatr Radiol. 2013;43:330–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim T-HK, Yang HK, Jang H-J, Yoo S-J, Khalili K, Kim T-HK. Abdominal imaging findings in adult patients with Fontan circulation. Insights Imaging. 2018;9:357–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghaferi AA, Hutchins GM. Progression of liver pathology in patients undergoing the Fontan procedure: Chronic passive congestion, cardiac cirrhosis, hepatic adenoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:1348–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sagawa T, Kogiso T, Kodama K, Taniai M, Tokushige K. Characteristics of Liver Tumor Arising from Fontan‐Associated Liver Disease. Hepatology. 2018;68:901. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoteit MA, Awh K, Serper M, Khungar V, Kim YY. Surveillance for Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) in Patients with a History of Fontan Repair of Congenital Heart Disease: A Single Center Experience. Hepatology. 2018;68:1463. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, Zhu AX, Finn RS, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR, Heimbach JK. Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68:723–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poterucha JT, Johnson JN, Qureshi MY, O’Leary PW, Kamath PS, Lennon RJ, Bonnichsen CR, Young PM, Venkatesh SK, Ehman RL, et al. Magnetic Resonance Elastography: A Novel Technique for the Detection of Hepatic Fibrosis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma After the Fontan Operation. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:882–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lemmer A, VanWagner LB, Ganger D. Assessment of Advanced Liver Fibrosis and the Risk for Hepatic Decompensation in Patients With Congestive Hepatopathy. Hepatology. 2018;68:1633–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wald C, Russo MW, Heimbach JK, Hussain HK, Pomfret EA, Bruix J. New OPTN/UNOS Policy for Liver Transplant Allocation: Standardization of Liver Imaging, Diagnosis, Classification, and Reporting of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Radiology. 2013;266:376–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wong TW, Gandhi MJ, Daly RC, Kushwaha SS, Pereira NL, Rosen CB, Stegall MD, Heimbach JK, Taner T. Liver Allograft Provides Immunoprotection for the Cardiac Allograft in Combined Heart–Liver Transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:3522–3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao K, Wang R, Kamoun M, Olthoff K, Hoteit M, Rame E, Levine M, Mclean R, Abt P. Liver Allograft Provides Protection Against Cardiac Allograft Rejection in Combined Heart And Liver Transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:114. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Duong P, Coats L, O’Sullivan J, Crossland D, Haugk B, Babu-Narayan SV., Keegan J, Hudson M, Parry G, Manas D, Hasan A. Combined heart-liver transplantation for failing Fontan circulation in a late survivor with single-ventricle physiology. ESC Hear Fail. 2017;4:675–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bradley EA, Pinyoluksana K on, Moore-Clingenpeel M, Miao Y, Daniels C. Isolated heart transplant and combined heart-liver transplant in adult congenital heart disease patients: Insights from the united network of organ sharing. Int J Cardiol. 2017;228:790–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vaikunth SS, Concepcion W, Daugherty T, Fowler M, Lutchman G, Maeda K, Rosenthal DN, Teuteberg J, Woo YJ, Lui GK. Short‐term outcomes of en bloc combined heart and liver transplantation in the failing Fontan. Clin Transplant. 2019;33: e13540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gamba A, Merlo M, Fiocchi R, Terzi A, Mammana C, Sebastiani R, Ferrazzi P. Heart transplantation in patients with previous Fontan operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:555–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jayakumar KA, Addonizio LJ, Kichuk-Chrisant MR, Galantowicz ME, Lamour JM, Quaegebeur JM, Hsu DT. Cardiac transplantation after the Fontan or Glenn procedure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:2065–2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Davies RR, Sorabella RA, Yang J, Mosca RS, Chen JM, Quaegebeur JM. Outcomes after transplantation for “failed” Fontan: A single-institution experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:1183–1192.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Backer CL, Russell HM, Pahl E, Mongé MC, Gambetta K, Kindel SJ, Gossett JG, Hardy C, Costello JM, Deal BJ. Heart Transplantation for the Failing Fontan. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:1413–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Michielon G, van Melle JP, Wolff D, Di Carlo D, Jacobs JP, Mattila IP, Berggren H, Lindberg H, Padalino MA, Meyns B, et al. Favourable mid-term outcome after heart transplantation for late Fontan failure. Eur J Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2015;47:665–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kanter KR. Heart Transplantation in Children after a Fontan Procedure: Better than People Think. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2016;19:44–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miller JR, Simpson KE, Epstein DJ, Lancaster TS, Henn MC, Schuessler RB, Balzer DT, Shahanavaz S, Murphy JJ, Canter CE, et al. Improved survival after heart transplant for failed Fontan patients with preserved ventricular function. J Hear Lung Transplant. 2016;35:877–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Berg CJ, Bauer BS, Hageman A, Aboulhosn JA, Reardon LC. Mortality Risk Stratification in Fontan Patients Who Underwent Heart Transplantation. Am J Cardiol. 2017;119:1675–1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hofferberth SC, Singh TP, Bastardi H, Blume ED, Fynn-Thompson F. Liver abnormalities and post-transplant survival in pediatric Fontan patients. Pediatr Transplant. 2017;21:e13061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Simpson KE, Pruitt E, Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Singh RK, Edens RE, Barnes AP, Canter CE. Fontan Patient Survival After Pediatric Heart Transplantation Has Improved in the Current Era. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103:1315–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bouchardy J, Meyer P, Yerly P, Blanche C, Hullin R, Giostra E, Hanquinet S, Rubbia-Brandt L, Sekarski N, Prêtre R, et al. Regression of Advanced Liver Fibrosis After Heart Transplantation in a Patient With Prior Fontan Surgery for Complex Congenital Heart Disease. Circ Hear Fail. 2018;11: e003754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Horai T, Bhama JK, Fontes PA, Toyoda Y. Combined Heart and Liver Transplantation in a Patient With Situs Ambiguous. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:600–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Raichlin E, Um JY, Duncan KF, Dumitru I, Lowes BD, Moulton M, Gebhart CL, Grant WJ, Hammel JM. Combined Heart and Liver Transplantation Against Positive Cross-Match for Patient With Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome. Transplantation. 2014;98:e99–e101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hofferberth SC, Singh TP, Bastardi H, Blume ED, Fynn-Thompson F. Liver abnormalities and post-transplant survival in pediatric Fontan patients. Pediatr Transplant. 2017;21:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim MH, Nguyen A, Lo M, Kumar SR, Bucavalas J, Glynn E, Hoffman MA, Rischer R, Emamaullee JA. Big data in transplantation practice - the devil is in the detail - Fontan Associated Liver Disease. Transplantation. 2020; In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wu FM, Jonas MM, Opotowsky AR, Harmon A, Raza R, Ukomadu C, Landzberg MJ, Singh MN, Valente AM, Egidy Assenza G, et al. Portal and centrilobular hepatic fibrosis in Fontan circulation and clinical outcomes. J Hear Lung Transplant. 2015;34:883–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Desai A, Sandhu S, Lai J-P, Sandhu DS. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-cirrhotic liver: A comprehensive review. World J Hepatol. 2019;11:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) data. [Internet] [cited 2020 Jan 1];Available from: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/

- 77.Colvin MM, Cook JL, Chang PP, Hsu DT, Kiernan MS, Kobashigawa JA, Lindenfeld J, Masri SC, Miller DV., Rodriguez ER, et al. Sensitization in Heart Transplantation: Emerging Knowledge: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139: e553–e578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Atluri P, Gaffey A, Howard J, Phillips E, Goldstone AB, Hornsby N, MacArthur JW, Cohen JE, Gutsche J, Woo YJ. Combined Heart and Liver Transplantation Can Be Safely Performed With Excellent Short- and Long-Term Results. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:858–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McClain CD, McGowan FX, Kovatsis PG. Laparoscopic Surgery in a Patient with Fontan Physiology. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:856–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lim DYY, Suhitharan T, Kothandan H. Anaesthetic management of a patient with Fontan physiology for electrophysiology study and catheter ablation. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:e228520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McGowan FX. Perioperative Issues in Patients with Congenital Heart Disease. Anesth Analg. 2005;15:53–61. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nayak S, Booker PDPD. The Fontan circulation. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2008;8:26–30. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Barbara DW, Rehfeldt KH, Heimbach JK, Rosen CB, Daly RC, Findlay JY. The perioperative management of patients undergoing combined heart-liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2015;99:139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]