Abstract

Background:

There is a rising prevalence of dermatophyte infection especially in the tropics. It has been observed that the antifungals are not as effective as they used to be.

Aims:

To determine the effectiveness of terbinafine and itraconazole in different doses and in combination in the treatment of tinea infection.

Materials and Methods:

Study design was a randomized parallel group trial. Patients were randomly divided into five parallel arms in which two of the standard drugs in recommended doses were compared with their double doses and with combination of both the drugs. Patients were followed up every 2 weeks. Outcomes were assessed at 4 and 8 weeks. Cure was considered as complete clinical resolution of the lesions. Fungal culture and sensitivity were done by disk diffusion method for all patients. Parametric one-way analysis of variance (F test) and Chi-square test were used for the analysis.

Results:

Two-hundred seventy-five patients were included in the study. Itraconazole containing groups showed significantly higher cure rates than terbinafine only groups both at 4 and 8 weeks (P < 0.001). Itraconazole containing groups, when compared against each other, were not found to be significantly different. The outcomes between terbinafine only groups were also not significantly different. Cure rates at 8 weeks were found to be greater than that at 4 weeks for all groups which were found to be highly significant (P < 0.001).

Conclusions:

Itraconazole seems to be more effective than terbinafine. There is no benefit in increasing the dose or using a combination regimen in the treatment of tinea. Prolonged duration of treatment is required for complete cure.

KEY WORDS: Combination treatment, itraconazole, terbinafine, tinea infection

Introduction

Tinea is a superficial fungal infection caused by dermatophytes which invade and multiply within the keratinized tissue (skin, hair, nails). Approximately 20%-25% of the world population is affected by tinea.[1] There is a rise in the prevalence in recent years especially in the tropical countries[2] along with an increase in the number of chronic and recurrent dermatophytosis. There is a huge gap between the treatment required in the present scenario and the treatment guidelines given in the standard books.[3,4,5]

There is a paucity of original studies especially in India depicting dermatophytosis becoming a huge menace both to the patient and to the treating physician. Terbinafine is a fungicidal drug and acts by inhibiting the enzyme squalene epoxidase which converts squalene to lanosterol. Itraconazole is basically a fungistatic drug that acts through inhibition of the enzyme 14α-demethylase. Many dermatologists have started using higher doses and combination regimens of antifungals to counter this problem. However, such regimens have not been validated. Hence, in this study we decided to evaluate the commonly used systemic antifungal drugs, i.e., terbinafine and itraconazole, at various doses and in combination.

Materials and Methods

The study design was a randomized parallel group open labeled trial conducted at a tertiary healthcare center. The study was conducted between August 2018 and July 2019. The trial was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. This trial was registered with CTRI (CTRI/2018/07/015063).

Participant’s inclusion criteria were KOH positive cases of tinea cruris, corporis and faciei.

Exclusion criteria were: (a) pregnancy and lactation, (b) children less than 12 years of age, (c) weight less than 40 kg and more than 80 kg, (d) any history of drug reaction or allergy to any of the two drugs, (e) any significant abnormality in complete blood counts (CBC), liver function test (LFT), renal function test (RFT) and electrocardiogram (ECG), (f) history of intake of oral antifungal agents in the last one month, (g) patient with any other disease requiring systemic therapy and (h) patients with co-morbidities like cardiac disorder, liver disorder, renal disorder.

Intervention: Five parallel study groups were as follows:

Terbinafine 250 mg/day: T 250

Itraconazole 200 mg/day in two divided doses: I 200

Terbinafine 250 mg + Itraconazole 200 mg: T + I

Terbinafine 500 mg/day in two divided doses: T 500

Itraconazole 400 mg/day in two divided doses: I 400.

Treatment and follow-up:

A written and informed consent was taken from each patient or his/her guardian. Patients were prescribed the allocated antifungal drug. Topical antifungal was not prescribed. The clinical improvement was assessed based on total body surface area involved (BSA) at each visit. The enrolled patients were called for follow up at every two weeks for a total of 8 weeks or till complete clearance of lesions. Investigations done at baseline were CBC, LFT, RFT, and ECG. At every second visit, LFT and ECG were repeated in the itraconazole groups and LFT and CBC in the terbinafine group. RFT was done at every second visit for all the groups. In the combination group, LFT, CBC and ECG were repeated at every second visit. Fungal culture and sensitivity of the skin scrapings were done by the disk diffusion method for all patients.

Outcome measures and statistical analysis

Patients were labeled as the following at both fourth and eighth weeks.

Primary outcome: Cured (complete clinical resolution of all lesions)

Secondary outcome: Partially cured (more than 50% improvement in the total BSA) and failure (increase in severity of the lesions or no improvement in the lesions after 4 weeks of staring antifungal agents).

Note: Partially cured and failure measures as secondary outcomes were added after commencement of the trial.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was calculated with 95% level of confidence, power of 80% and considering cure rates of 65% and 90%. By taking 1:1 allocation and considering the dropout rates to be 10%, the final sample size calculated was 275.

Randomization

Participants were randomized equally in a 1:1 allocation (unstratified) into five parallel treatment groups by a computer-generated random number sequence using the MS Excel software and one of the author assigned participants to the interventions. Blinding was not done.

Statistical analysis

Parametric one-way analysis of variance (F test) was applied to find out the mean differences among five treatment groups. Chi-square test was used to find out significant difference in the proportions among treatment groups and it was also used to test the significance of change from baseline to various follow-up within the groups. A P value less than 0.05 was considered as significant. Patients who were excluded from the study due to adverse events or lost to follow-up were not included in the data for statistical analysis.

Clinico-mycological correlation was done at the end of the study.

Results

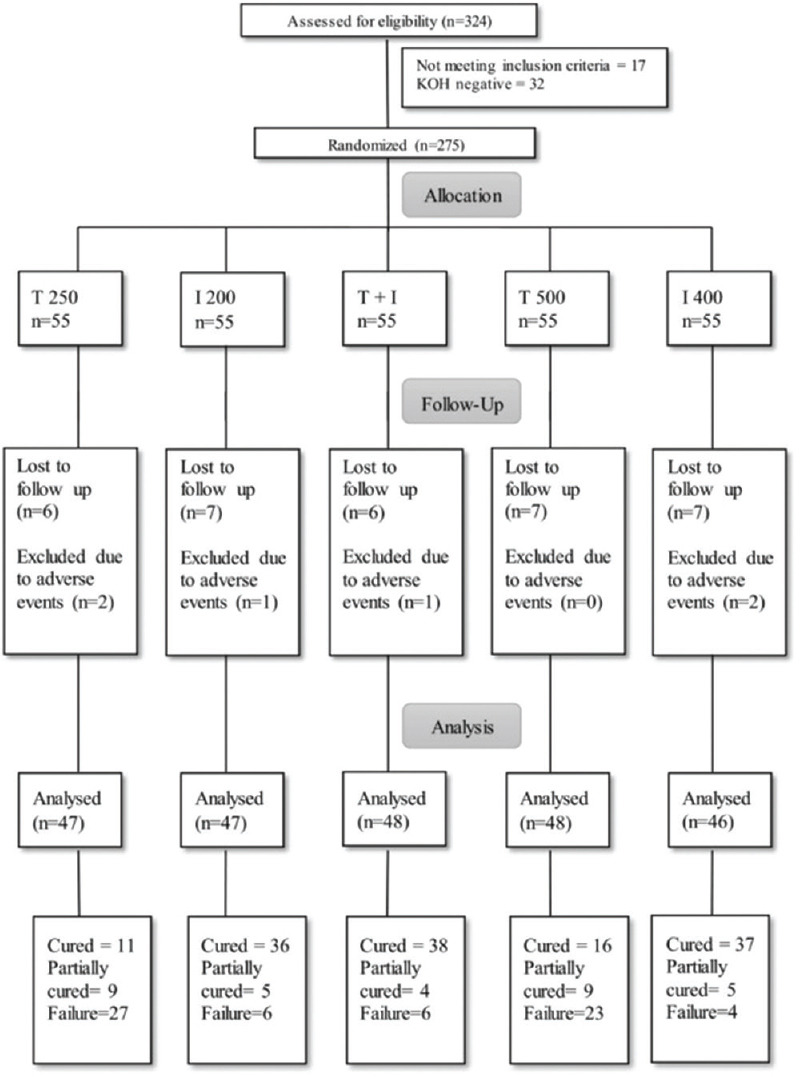

A total of 324 patients were screened and 275 patients (55 in each group) of tinea cruris, corporis and faciei were enrolled in the study [Figure 1]. The mean age of the patients was 29.36 ± 11.37 years. Majority of the patient (36.4%) belonged to 21 to 30 years of age. The disease was more common in males (74.1%) and male to female ratio was 2.8:1. Majority of the patients had BSA less than 5% (69.9%) and 81.2% had the disease for 1-6 months duration. Most of the patients weighed 51 to 60 kg (35%). The patient characteristics were comparable in all the groups [Table 1]. In this study, 81.7% had used topical corticosteroid either alone or in combination with an antifungal and/or antibiotic. Topical antifungal only creams were used by 10.1% and 8.05% did not apply any topical agent. Most common clinical variant was tinea corporis and cruris (69%) [Table 2].

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics (n=236)

| Characteristics | Groups | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T 250 | I 200 | T+I | T 500 | I 400 | ||

| Age (years) (Mean±SD) | 32.45±11.411 | 28.06±12.541 | 29.67±10.125 | 27.02±10.680 | 29.65±11.733 | 0.187 |

| Male (%) | 70.2 | 72.3 | 75.0 | 68.8 | 84.8 | 0.417 |

| Female (%) | 29.8 | 27.7 | 25.0 | 31.3 | 15.2 | |

| Weight (kg) (Mean±SD) | 61.85±10.685 | 58.70±9.666 | 61.33±8.873 | 61.65±9.723 | 63.72±10.195 | 0.188 |

| Baseline BSA (Mean±SD) | 5.21±4.288 | 7.49±11.371 | 4.40±3.187 | 5.25±4.071 | 5.43±4.385 | 0.169 |

Table 2.

Clinical variants of tinea (n=236)

| Diagnosis | Total n (%) |

|---|---|

| T. corporis et cruris | 163 (69) |

| T. corporis et cruris et faciei | 34 (14.4) |

| T. cruris | 21 (8.8) |

| T. corporis | 15 (6.3) |

| T. faciei | 2 (0.8) |

| T. corporis et faciei | 1 (0.4) |

T: Tinea

Out of 275 samples cultured at baseline, fungal growth was seen in 111 samples (40.3%). The most common growth observed was of Trichophyton mentagrophytes (72.9%). T. interdigitale was found in 25 (22.5%) and a combination of T. mentagrophytes and T. interdigitale was detected in four cases. Only a single strain of Trichophyton rubrum was isolated. Ninety nine (89%) isolates were sensitive to itraconazole and only 28 (25.2%) isolates were sensitive to terbinafine. Two hundred thirty-six patients completed the study, rest were excluded due to adverse events or lost to follow-up. The outcome of the study was assessed at 4 and 8 weeks. At 4 weeks, 2 (4.3%), 8 (17%), 9 (18.9%), 3 (6.3%) and 9 (19.6%) were cured with T 250, I 200, I + T, T 500 and I 400 respectively (P < 0.001). At 8 weeks, 11 (23.4%), 36 (76.6%), 38 (79.2%), 16 (33.3%) and 37 (80.4%) were cured respectively (P < 0.001).

At 4 weeks, 38.3%, 70.2%, 68.8%, 45.8% and 71.7% were partially cured among T 250, I 200, I + T, T 500 and I 400 groups respectively. At 8 weeks, the figures were 19.1%, 10.6%, 8.3%, 18.8% and 10.9%, respectively. Itraconazole containing groups showed statistically highly significant cure rates than terbinafine only groups at both 4 and 8 weeks. Cure rates of I 200 vs I 400 vs I + T against each other were not significant. The outcome between T 250 and T 500 was also not statistically significant. Cure rates at 8 weeks were found to be greater than that at 4 weeks for all groups, which was found to be highly significant.

Lichenoid drug eruption and acute urticaria developed in one patient each in T-250 group. One patient in each group taking itraconazole developed increased liver enzymes (AST/ALT more than two times the upper limit of normal) and one patient developed erectile dysfunction in I 400 group.

One of the most important aspects of the study was the clinico-mycological correlation, which was done at the end of the study. Eighty three culture positive cases completed the study. A good clinical correlation was seen with majority of the sensitivity results. However, some exceptions were noted. Out of the 72 isolates sensitive to itraconazole five did not respond to itraconazole. Two out of 11 isolates resistant to itraconazole responded to treatment, both were cured. One out of 20 isolates sensitive to terbinafine failed to respond to terbinafine. Two out of the 63 isolates which were resistant to terbinafine, responded to treatment with terbinafine. One patient got cured completely and the other got partially cured.

Discussion

There has been a drastic change in the Indian scenario of dermatophytosis with increase in the occurrence, relapse, recurrence and chronicity in the recent years which have added to the morbidity. This may partly be attributed to the injudicious use of oral antifungals and the rampant misuse of topical steroids due to easy availability of over-the-counter (OTC) topical steroid combination products.[6] The patients, pharmacists, quacks and few general physicians have a nonchalant attitude toward the use of these OTC products, which have led to an epidemic of “steroid-modified tinea”.[7] Older effective antifungals in literature seem to have lost their efficacy and the standard treatment recommendations for treatment of tinea seem to be no longer valid.

The most common age group involved in this study was 21-30 years of age (36.4%) with mean of 29.36 ± 11.37 year, which is similar to that of the previous studies.[8,9,10,11,12] Male:Female ratio was approximately 2.8:1. This may be attributed to the fact that males are mostly involved in outdoor physical activities, which lead to excessive sweating making a favorable environment for the fungal infections. Tinea may be underdiagnosed in females and their treatment-seeking behavior is also less. This finding of male predominance is similar to other previous studies, in which M:F ratio varied from 2-4:1.[13,14] Most common clinical variant was tinea corporis and cruris (69%). Mahajan et al. also reported mixed tinea corporis and cruris infection as the commonest form.[15] In this study, 81.7% had used topical corticosteroid either in combination with an antifungal, an antibiotic or alone.

Fungal growth was seen in 111 out of 275 samples (40.3%). There is a wide variation in the yield of the fungus in the culture. Most studies reported higher yield, greater than 40%[13,16,17,18] and some reported yield less than 40%.[19,20] The most common growth observed was of Trichophyton mentagrophytes (30.7%). Previously Trichophyton rubrum used to be the most common species but now as observed in the recent studies Trichophyton mentagrophytes has emerged as a dominant one.[15,21,22,23] Ajello mentioned that fungal strains causing dermatophytoses not only differed from region to region but might change with the passage of time.[24] Antifungal susceptibility was done using disk diffusion method. Many studies have shown a good correlation between disk diffusion method and Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) micro broth dilution method.[25,26,27] Ninety-nine (89%) isolates were sensitive to itraconazole and only 28 (25.2%) isolates were sensitive to terbinafine. Singh et al. has reported 82% of 44 strains of dermatophyte resistant to terbinafine and 15% of strains resistant to itraconazole.[23] Molecular resistance to terbinafine due to mutation of squalene epoxidase gene has been reported.[28,29]

In this study, itraconazole was the more effective drug. Majid et al.[30] reported a cure rate of 65% with terbinafine 250 mg daily after 2 weeks; Singh and Shukla[31] reported a decreased cure rate of 30% after 4 weeks and in this study the cure rate has further plummeted down to 23% even after 8 weeks. This finding is consistent with the decreased response observed with terbinafine-treated patients. The cure rate of terbinafine 500 was 33%, which was not found to be significantly different from that of T-250. This finding is in contrast to that seen by Bhatia et al.[32] who reported a cure rate of 74%. In a retrospective study by Babu et al., 80% of patients showed more than 75% improvement with terbinafine 500 mg daily.[33] Multidrug therapy and increasing the dose do not seem to have any added benefit.

Tearaki and Shiohara[34] and Zheng et al.[35] have reported lichenoid drug eruption following terbinafine. FDA has mentioned decreased libido as an adverse drug reaction with itraconazole occurred in clinical trials with an incidence of 1%. Bailey et al. and Tucker et al. have reported erectile dysfunction as a rare side effect following itraconazole intake.[36,37] FDA stated liver function abnormalities occurred in 3% of the patients in the clinical trials. In our study, derangement of liver enzymes occurred in 1.27% of patients taking itraconazole. On clinico-mycological correlations, most of the patients with sensitive isolates responded with respective drugs. Few patients did not respond. On the other hand few patients responded while their isolates were resistant to a particular drug. This discrepancy of results may be due to a multitude of factors, such as drug pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, host response, local treatment of the infection site. This prompted Rex and Pfaller to coin the phrase the 90-60 rule.[38] In general if a microbe is found to be susceptible to a drug, 90% of patients are likely to have a favorable therapeutic response. In contrast to with resistant strain, nearly 60% of patients may be expected to respond to therapy.

Dosage of terbinafine according to body weight is approved for tinea capitis. Singh et al. has used 5 mg/kg body weight for the treatment of tinea corporis, cruris, faciei in children and adults.[31] Itraconazole dosage of 5 mg/kg body weight has been used in children and infants with superficial dermatophytosis and found to be effective and safe.[39,40] In adults a fixed-dose regimen of 250 mg/day terbinafine and 200 mg/day itraconazole is recommended.[3,4]

The sudden increase in the number of recalcitrant tinea in India is of major concern. Antifungals no longer seem to work like they used to previously. Itraconazole is the most effective antifungal drug against dermatophytes and longer duration of treatment is required for complete cure of the disease. Use of higher doses of both terbinafine and itraconazole or combination does not seem to have any additional benefit. Results of antifungal susceptibility tests predict the clinical outcome in majority of the cases. The decline in the efficacy of antifungal is of grave concern. The reasons are not fully understood but many speculate it to be due to use of OTC topical steroid combination products, misuse of drugs and development of resistance. It is crucial that the use of OTC products and misuse of these drugs should be reduced. In the coming years just like terbinafine, there is a chance that efficacy of itraconazole may drop as well leaving us with very limited armamentarium of drugs that can be used.

The limitations of the study were non-blinding and use of fixed doses although variation in the weights of subjects. Long follow-up for recurrences also was not done.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycose. 2008;51:2–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sahoo AK, Mahajan R. Management of tinea corporis, tinea cruris, and tinea pedis: A comprehensive review. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:77–86. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.178099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hay RJ, Ashbee HR. Fungal infections. In: Griffiths CE, Barker J, Bleiker T, Chalmers R, Creamer D, editors. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 9th ed. II. West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell; 2016. p. 945. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schieke SM, Garg A. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffel DJ, Wolff K, editors. 8th ed. II. New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012. p. 2294. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shenoy MM, Shenoy SM. Superficial fungal infections. In: Sacchidanand S, Oberoi C, Inamdar AC, editors. IADVL Textbook of Dermatology. 4th ed. I. Mumbai: Bhalani Publishing House; 2015. pp. 459–516. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarkar S. A treatise on topical corticosteroid in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol. 2018;63:530–1. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verma S, Madhu R. The great Indian epidemic of superficial dermatophytosis: An appraisal. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:227–36. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_206_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grover WC, Roy CP. Clinico-mycological profile of superficial mycosis in a hospital in North-East India. Med J Armed Forces India. 2003;59:114–6. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(03)80053-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh S, Beena PM. Profile of dermatophyte infections in Baroda. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:281–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sumana V, Singaracharya MA. Dermatophytosis in Khammam (Khammam district, Andhra Pradesh, India) Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2004;47:287–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel P, Mulla S, Patel D, Shrimali G. A study of superficial mycosis in South Gujarat Region. Natl J Community Med. 2010;1:85–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamothi MN, Patel BP, Mehta SJ, Kikani KM, Pandhya JM. Prevalence of dermatophyte infection in District Rajkot. Electron J Pharmacol Ther. 2010;3:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bindu V, Pavithran K. Clinico-mycological study of dermatophytosis in Calicut. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2002;68:259–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh RR, Ray RN, Ghosh TK, Ghosh AP. Clinicomycological profiles of dermatophytosis in a tertiary care rural hospital. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2014;3:655–66. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahajan S, Tilak R, Kaushal SK, Mishra RN, Pandey SS. Clinico-mycological study of dermatophytic infections and their sensitivity to antifungal drugs in a tertiary care center. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:436–40. doi: 10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_519_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kannan P, Janaki C, Selvi GS. Prevalence of dermatophytes and other fungal agents isolated from clinical samples. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2006;24:212–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta CM, Tripathi K, Tiwari S, Rathore Y, Nema S, Dhanvijay AG. Current trends of clinicomycological profile of dermatophytosis in Central India. J Dent Med Sci. 2014;13:23–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta AK, Mohan A, Singh SK, Pandey AK. Studying the clinic mycological pattern of the dermatophytic infection attending OPD in tertiary care hospital in eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Int J Res Dermatol. 2018;4:118–25. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyngdoh CJ, Lyngdoh WV, Choudhury B, Sangma KA, Bora I, Khyriem AB. Clinico-mycological profile of dermatophytosis in Meghalaya. Int J Med Public Health. 2013;3:254–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agrawal E, Marothi Y, Varma K, Agrawal M, Murthy R. Distribution and characterization of dermatophytes in a tertiary care hospital in Madhya Pradesh. J Evolution Med Dent Sci. 2015;4:201–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.VK Bhatia, PC Sharma. Epidemiological studies on dermatophytosis in human patients in Himachal Pradesh, India. Springerplus. 2014;3:1–7. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pathania S, Rudramurthy SM, Narang T, Saikia UN, Dogra S. A prospective study of the epidemiological and clinical patterns of recurrent dermatophytosis at a tertiary care hospital in India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:678–84. doi: 10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_645_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh SK, Patwa DK, Tilak R, Das A, Singh TB. In vitro susceptibility of dermatophytes to oral antifungal drugs and amphotericin B in Uttar Pradesh, India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2019;85:388–92. doi: 10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_319_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ajello L. Geographic distribution and prevalence of the dermatophytes. Ann New York Acad Sci. 1960;89:30–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1960.tb20127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venugopal PV, Venugopal TV. Disk diffusion susceptibility testing of dermatophytes with allylamines. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:730–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1994.tb01522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alim MA, Halim RM, Habib SA. Comparison of broth micro dilution and disk diffusion methods for susceptibility testing of dermatophytes. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2017;69:1923–30. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta S, Kumar RA, Mittal G, Roy S, Khan F, Agrawal A. Comparison of broth micro dilution and disk diffusion method for susceptibility testing of dermatophytes. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2015;4:24–33. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh A, Masih A, Khurana A, Singh PK, Gupta M, Hagen F, et al. High terbinafine resistance in Trichophyton interdigitale isolates in Delhi, India harbouring mutations in the squalene epoxidase gene. Mycoses. 2018;61:477–84. doi: 10.1111/myc.12772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudramurthy SM, Shankarnarayan SA, Dogra S, Shaw D, Mushtaq K, Paul RA, et al. Mutation in the squalene epoxidase gene of Trichophyton interdigitale and Trichophyton rubrum associated with allylamine resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62:pii:2522–17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02522-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02522-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Majid I, Sheikh G, Kanth F, Hakak R. Relapse after oral terbinafine therapy in dermatophytosis: A clinical and mycological study. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:529–33. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.190120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh S, Shukla P. End of the road for terbinafine?. Results of a pragmatic prospective cohort study of 500 patients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:554–7. doi: 10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_526_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhatia A, Kanish B, Badyal DK, Kate P, Choudhary S. Efficacy of oral terbinafine versus itraconazole in treatment of dermatophytic infection of skin - A prospective, randomized comparative study. Indian J Pharmacol. 2019;51:116–9. doi: 10.4103/ijp.IJP_578_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Babu PR, Pravin AJ, Deshmukh G, Dhoot D, Samant A, Kotak B. Efficacy and safety of terbinafine 500 mg once daily in patients with dermatophytosis. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:395–9. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_191_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teraki Y, Shiohara T. Spontaneous tolerance to terbinafine-induced lichenoid drug eruption. Dermatology. 2004;208:81–2. doi: 10.1159/000075054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng Y, Zhang J, Chen H, Lai W, Maibach HI. Terbinafine-induced lichenoid drug eruption. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2017;36:101–3. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2016.1160101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bailey EM, Krakovsky DJ, Rybak MJ. The triazole antifungal agents: A review of itraconazole and fluconazole. Pharmacotherapy. 1990;10:146–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tucker RM, Haq Y, Denning DW, Stevens DA. Adverse events associated with itraconazole in 189 patients on chronic therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990;26:561–6. doi: 10.1093/jac/26.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rex JH, Pfaller MA. Has antifungal susceptibility testing come of age? Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:982–9. doi: 10.1086/342384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gupta AK, Nolting S, de Prost Y, Delescluse J, Degreef H, Theissen U, et al. The use of itraconazole to treat cutaneous fungal infections in children. Dermatology. 1999;199:248–52. doi: 10.1159/000018256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen S, Sun KY, Feng XW, Ran X Lama J, Ran YP. Efficacy and safety of itraconazole use in infants. World J Pediatr. 2016;12:399–407. doi: 10.1007/s12519-016-0034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]