Abstract

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a heterogenous group of RNAs, which can encode small proteins. The extent to which developmentally regulated lncRNAs are translated and whether the produced microproteins are relevant for human development is unknown. Using a human embryonic stem cell (hESC)-based pancreatic differentiation system, we show that many lncRNAs in direct vicinity of lineage-determining transcription factors (TFs) are dynamically regulated, predominantly cytosolic, and highly translated. We genetically ablated ten such lncRNAs, most of them translated, and found that nine are dispensable for pancreatic endocrine cell development. However, deletion of LINC00261 diminishes insulin+ cells, in a manner independent of the nearby TF FOXA2. One-by-one disruption of each of LINC00261's open reading frames suggests that the RNA, rather than the produced microproteins, is required for endocrine development. Our work highlights extensive translation of lncRNAs during hESC pancreatic differentiation and provides a blueprint for dissection of their coding and noncoding roles.

Research organism: Human

Introduction

Defects in pancreatic endocrine cell development confer increased diabetes risk later in life (Bakhti et al., 2019). Therefore, a detailed understanding of the factors that orchestrate endocrine cell differentiation is highly relevant to human disease. Many of the molecular mechanisms that underlie the formation of pancreatic endocrine cells have been defined (Romer and Sussel, 2015; Schiesser and Wells, 2014). However, despite some evidence that long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are important for proper development and function of pancreatic beta cells (Arnes et al., 2016; Morán et al., 2012; Wong et al., 2019), a systematic functional assessment of the noncoding transcriptome during pancreas development is lacking.

Most lncRNAs with to date demonstrated roles in the regulation of fundamental developmental processes are active in the cell's nucleus (Daneshvar et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2015; Klattenhoff et al., 2013; Kurian et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2014; Luo et al., 2016; Ramos et al., 2015). However, a large proportion of lncRNAs is predominantly cytosolic (Cabili et al., 2015; van Heesch et al., 2014), and the functional relevance of these lncRNAs has remained unexplored in the context of human development. It is now widely accepted that many cytosolic lncRNAs possess short, ‘non-canonical’ open reading frames (sORFs) that are translated (Bazzini et al., 2014; Makarewich and Olson, 2017; Ruiz-Orera et al., 2014). What fraction of these non-canonical ORFs is functional, and whether sORF translation serves a pure regulatory purpose or results in the production of stable microproteins, remains an active topic of debate (Levy, 2019; Ruiz-Orera et al., 2018). Since high rates of conservation have historically been employed for the identification and annotation of canonical protein coding sequences (Lin et al., 2011; Mudge et al., 2019), a primary reason for doubting the protein-coding capacity of sORFs in presumed lncRNAs is their generally poor sequence conservation across species. To address these questions, several recent studies have systematically assessed the biological activity of newly discovered sORFs, revealing that many produce evolutionary young microproteins with roles across cellular organelles and processes, and a subset being essential for cell survival (Chen et al., 2020; Martinez et al., 2020; Prensner et al., 2020; van Heesch et al., 2019). This previously unrecognized coding capacity of supposedly noncoding RNAs illustrates their functional diversity and has called into question the noncoding classification of some lncRNAs. Thus, there is a need for careful investigation and dissection of any gene's coding and noncoding functions.

LncRNAs, translated or fully noncoding, are not randomly distributed in the genome but are frequently located close to, and coregulated with, canonical protein-coding genes in cis (Luo et al., 2016; Neumann et al., 2018; van Heesch et al., 2019). For example, the lncRNAs DIGIT (also known as GSC-DT) and Gata6as (also known as lncGata6 or GATA6-AS1) have been reported to enhance expression of divergently expressed endoderm regulators Goosecoid (GSC) and Gata6, respectively (Daneshvar et al., 2016; Luo et al., 2016; Neumann et al., 2018). Similarly, the Pax6-associated lncRNA Paupar promotes pancreatic islet alpha cell formation through the alternative splicing of Pax6 transcripts in mice (Singer et al., 2019). Furthermore, LINC00261 (also known as DEANR1) and its neighboring TF FOXA2 are both induced in endoderm formation, during which LINC00261 has been proposed to positively regulate FOXA2 expression (Jiang et al., 2015). However, whether such cis-acting lncRNAs are translated and may exert cytosolic functions through trans-acting, microprotein-dependent mechanisms relevant for endoderm and pancreas development is not known.

In this study, we classified lncRNAs based on their dynamic regulation, subcellular localization, and translation in a hESC differentiation system that recapitulates in vivo pancreas development. Next, we used this classification to prioritize select dynamically regulated and highly translated lncRNAs for deletion in hESCs, followed by extensive phenotypic characterization across multiple intermediate states of pancreas development. Nine out of the ten selected lncRNAs were not essential for pancreatic development and, despite their vicinity to lineage-determining TFs, none of these lncRNAs regulated the expression of these TFs in cis.

The deletion of one lncRNA, LINC00261, impaired human endocrine cell development and led to a significant reduction in the number of insulin-producing cells. Contrary to previous studies of LINC00261 knockdown hESCs (Jiang et al., 2015), deletion of LINC00261 had no effect on the expression of nearby TF FOXA2 or other proximal genes, suggesting control of endocrine cell formation through a trans- rather than cis-regulatory mechanism. LINC00261 was among the most highly translated lncRNAs based on ribosome profiling (Ribo-seq) and produced multiple microproteins with distinct subcellular localizations upon overexpression in vitro. To systematically assess LINC00261's coding and noncoding functions, we separately introduced frameshift mutations into each of seven identified LINC00261 sORFs. However, rigorous phenotypic characterization revealed no apparent consequences of loss of each of the seven LINC00261-sORF-encoded microproteins on endocrine cell development. Our comprehensive assessment of functional lncRNA translation identified a likely trans-regulatory role for LINC00261 in endocrine cell differentiation that appears to be independent of the seven microproteins that were individually deleted. With this detailed investigation we provide a blueprint for the proper dissection of a gene's coding and noncoding roles in a human disease-relevant system.

Results

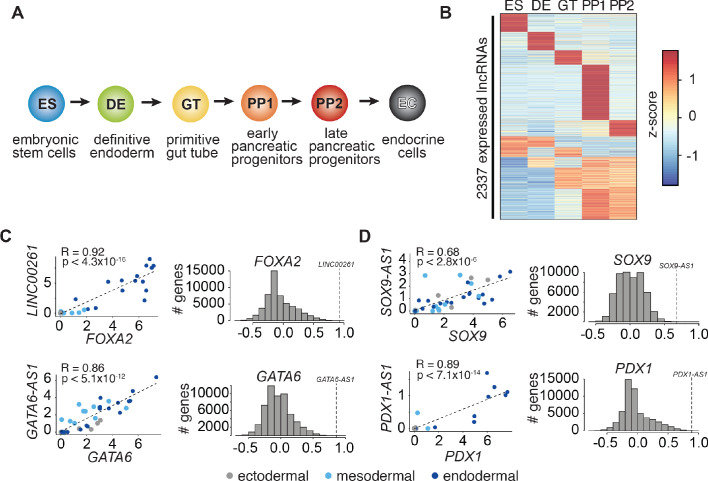

LncRNAs and nearby lineage-determining transcription factors exhibit dynamic coregulation during pancreas development

To identify lncRNAs involved in the regulation of pancreas development, we profiled RNA expression at five defined stages of hESC differentiation toward the pancreatic lineage: hESCs (ES), definitive endoderm (DE), primitive gut tube (GT), early pancreatic progenitor (PP1), and late pancreatic progenitor (PP2) (Figure 1A). While some lncRNAs were constitutively expressed (n = 592; 25.3%), the majority showed dynamic expression patterns (n = 1745; 74.7%), being either strongly enriched in (n = 874; 37.4%) or specific to (n = 871; 37.3%) a single developmental intermediate of pancreatic lineage progression (Figure 1B and Figure 1—source data 1A). The expression of many of these dynamically regulated lncRNAs correlated with that of proximal coding genes (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A–D and Figure 1—source data 1B,C), further exemplified by a subset of lncRNAs that was specifically coregulated with the key endodermal and pancreatic TFs GATA6, FOXA2, PDX1, and SOX9 (Figure 1C,D). The expression coregulation of these lncRNA-TF pairs is likely explained by a shared chromatin environment (Figure 1—figure supplement 1E–H), which raises the possibility that like the TFs, the function of the lncRNAs is also required for endoderm and pancreas development.

Figure 1. LncRNA expression and regulation during pancreatic differentiation.

(A) Stages of directed differentiation from human embryonic stem cell (hESCs) to hormone-producing endocrine cells. The color scheme for each stage is used across all figures. (B) K-means clustering of all lncRNAs expressed (RPKM ≥ 1) during pancreatic differentiation based on their expression z-score (mean of n = 2 independent differentiations per stage; from CyT49 hESCs). (C,D) Left: Scatterplots comparing the expression of early (C) and late (D) expressed endodermal transcription factors (TFs) with the expression of their neighboring lncRNAs across 38 tissues. The dot color indicates the germ layer of origin of these tissues. Pearson correlation coefficients and p-values (t-test) are displayed. Right: Distribution of the Pearson correlation coefficients for each TF with all Ensembl 87 genes across the same 38 tissues. Dashed lines denote the correlation for the neighboring lncRNA, which for all lncRNAs shown is higher than expected by chance. See also Figure 1—figure supplement 1 and Figure 1—source data 1.

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Characterization of lncRNAs expressed during pancreatic differentiation.

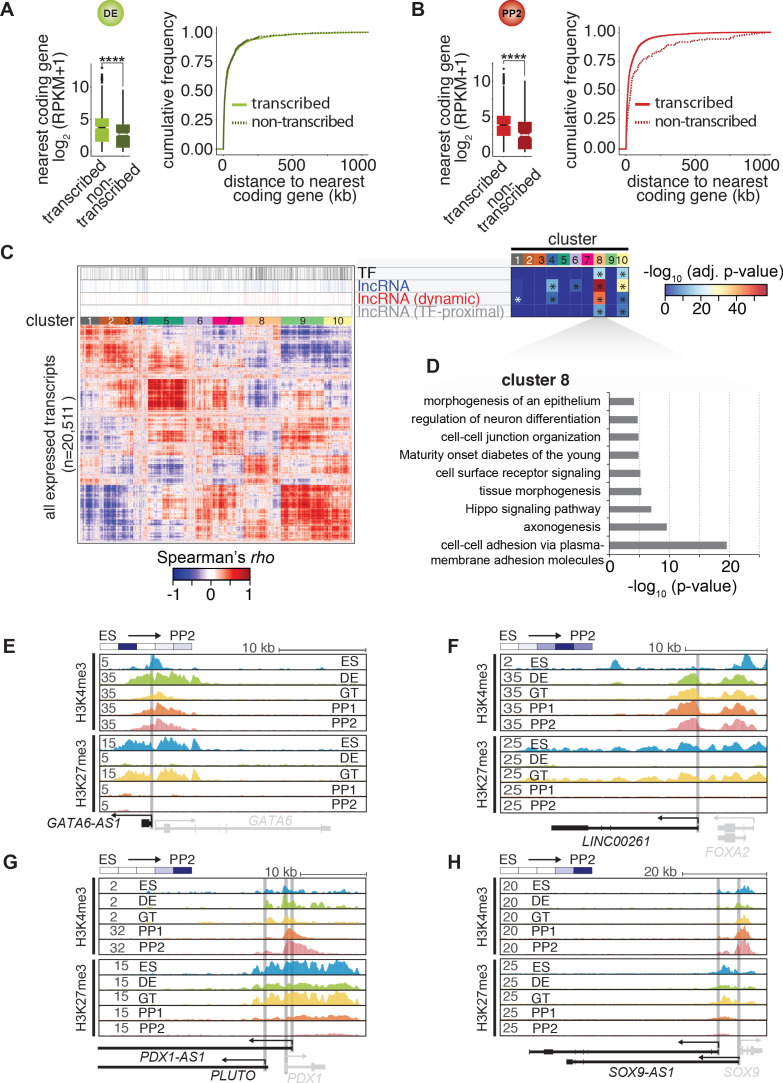

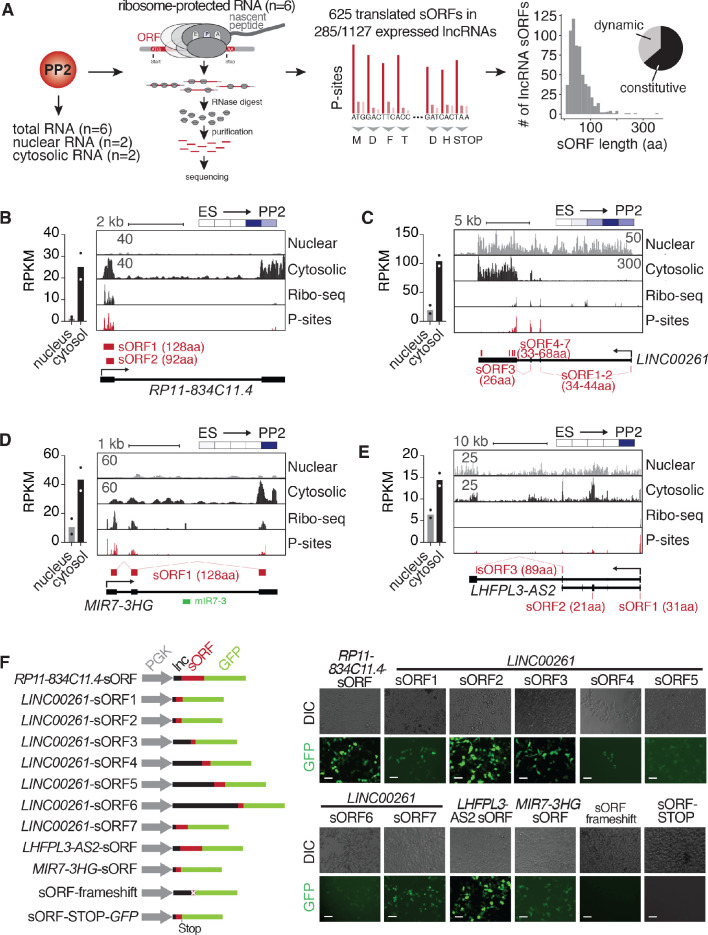

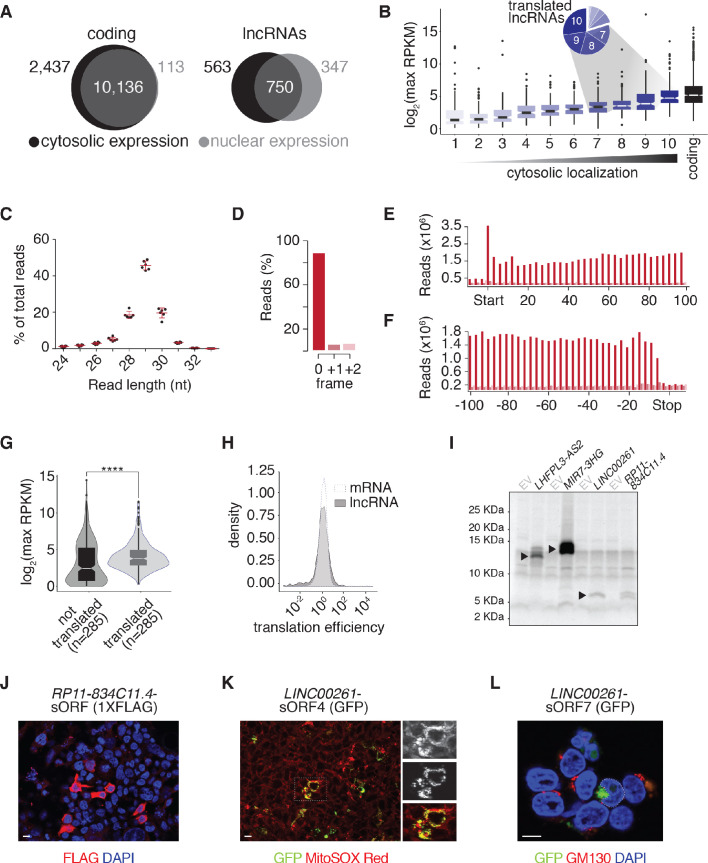

Many pancreatic progenitor-expressed lncRNAs are cytoplasmically enriched and translated

Although most functional roles described for lncRNAs to date have been predominantly nuclear (Marchese et al., 2017), multiple recent studies have shown that many lncRNAs are cytosolic and translated into sometimes biologically active microproteins (reviewed in Makarewich and Olson, 2017). To further characterize the above-identified dynamically regulated lncRNAs, we analyzed their subcellular localization and translation potential using fractionation RNA-seq and Ribo-seq across multiple hESC clones independently differentiated into PP2 stage pancreatic progenitors (Figure 2A). Of all lncRNAs expressed in two replicate differentiations into PP2 cells, we classified 21% (n = 347) as localized to the nucleus, whereas a larger number (n = 563; 34%) primarily resided in the cytosol (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A and Figure 2—source data 1A). This subcellular distribution of pancreatic lncRNAs is in agreement with previous lncRNA localization studies by us and others (Cabili et al., 2015; Clark et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2015; van Heesch et al., 2014). LncRNAs enriched in the cytosol were expressed at higher levels than nucleus-localized lncRNAs, with expression levels similar to canonical protein-coding mRNAs (Figure 2—figure supplement 1B). Intriguingly, almost half (49.4%) of all cytosol-enriched lncRNAs (278 out of 563) displayed dynamic expression regulation during the differentiation of hESCs to pancreatic progenitors, raising the possibility that many lncRNAs with putative developmental functions do not act in the nucleus, but instead in the cytosol where they may be translated.

Figure 2. Cytosolic lncRNAs contain translated small open reading frames.

(A) Overview of experimental strategy for subcellular fractionation and Ribo-seq-based identification of translated small open reading frames (sORFs) from lncRNAs expressed in PP2 cells. Replicates from six independent differentiations to PP2 stage each for total (polyA) RNA-seq and Ribo-seq experiments, and two biological replicates for the subcellular fractionation were analyzed. The histogram on the far right depicts the size distribution of the sORF-encoded small peptides as number of amino acids (aa). The pie chart summarizes the percentages of constitutively and dynamically expressed sORF-encoding lncRNAs during pancreatic differentiation of CyT49 hESCs. (B–E) Left: Bar graphs showing nuclear and cytosolic expression (in RPKM) of lncRNAs RP11-834C11.4 (B), LINC00261 (C), MIR7-3HG (D), and LHFPL3-AS2 (E). Data are shown as mean, with individual data points represented by dots (n = 2 biological replicates). Right: Subcellular fractionation RNA-seq, Ribo-seq, and P-site tracks (ribosomal P-sites inferred from ribosome footprints on ribosome-protected RNA) for loci of the depicted lncRNAs. Identified highest stringency sORFs (ORF in 6/6 replicates) are shown in red. For LINC00261, visually identified sORFs 1 and 2 are also shown. Heatmaps in the top right visualize the relative expression of the shown lncRNAs during pancreatic differentiation (means of two biological replicates per stage), on a minimum (white)/maximum (dark blue) scale. (F) In vivo translation reporter assays testing whether sORFs computationally defined in (A) give rise to translation products in HEK293T cells when fused in-frame to a GFP reporter. Left: Schematic of the constructs (gray: PGK promoter, black: lncRNA sequence 5’ to sORF to be tested, red: sORF, green: GFP ORF). Right: Representative DIC and GFP images of HEK293T cells transiently transfected with the indicated reporter constructs. Scale bars = 50 µm. See also Figure 2—figure supplement 1 and Figure 2—source data 1.

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. Cytosolic lncRNAs engage with ribosomes.

To investigate the translation potential of these cytosolic lncRNAs, we used Ribo-seq, through which we obtained exceptionally deep and high quality translatome coverage across six replicate differentiations (Figure 2—figure supplement 1C and Figure 2—source data 1B). As nearly 90% of the sequenced ribosomal footprints exhibited clear 3-nucleotide codon movement characteristic of translation (Figure 2—figure supplement 1D–F), these data have strong predictive value for the computational detection of non-canonical ORFs, such as upstream ORFs (uORFs) in the 5' leader sequences of mRNAs and sORFs in genes annotated as lncRNAs (Figure 2—source data 1C). Requiring stringent reproducibility criteria (the exact ORF needed to be detected by RiboTaper (Calviello et al., 2016) in at least four out of six replicates), we identified a total of 625 new sORFs in lncRNAs with a median length of 47 amino acids (aa) (Figure 2—source data 1D). The majority of detected sORFs (76%; n = 477/625) is currently not present in the sORFs.org database (Olexiouk et al., 2016). The translated sORFs are located within 285 cytosolically localized lncRNAs (25.3% of all expressed lncRNAs) (Figure 2—figure supplement 1B), which are expressed at higher levels than untranslated lncRNAs (Figure 2—figure supplement 1G) and exhibit translational efficiencies similar to mRNAs (Figure 2—figure supplement 1H and Figure 2—source data 1E). Of note, almost none of the newly identified sORFs are highly conserved across species, as judged by their low PhyloCSF scores (Lin et al., 2011; Figure 2—source data 1D).

Using approaches similar to ours, non-canonical sORFs have previously been characterized in multiple immortalized human cell lines (Bazzini et al., 2014; Calviello et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2020; Ji et al., 2015; Martinez et al., 2020; Prensner et al., 2020; Raj et al., 2016) and human tissues (van Heesch et al., 2019). However, to our knowledge, our data constitute the first comprehensive set of non-canonical human ORFs generated from a non-transformed human cell model of development, providing a valuable resource for future functional studies.

Translated lncRNAs in pancreatic progenitors produce microproteins with distinct subcellular localizations

Having established that many stage-specific pancreatic lncRNAs are translated, we next sought to validate their translation potential through independent experimental approaches, additionally investigating the production of the predicted microproteins at the protein level. To this end, we first performed coupled in vitro transcription:translation assays on endogenous and complete transcript isoforms of four of the most highly translated lncRNAs (LINC00261, RP11-834C11.4, LHFPL3-AS2, and MIR7-3HG; Figure 2—figure supplement 1I; expression and ORF information in Figure 2B–E). Second, we generated a series of in vivo translation reporter constructs to assess the subcellular localization of microproteins translated from each of ten sORFs derived from the same four lncRNAs. Transient expression of individual constructs carrying in-frame GFP fusions in HEK293T cells produced GFP signal for all ten assayed microproteins, which was abolished upon introduction of a frameshift within the sORF or a stop codon following the sORF sequence (Figure 2F and Figure 2—figure supplement 1J–L). To rule out a possible localization bias induced by the GFP fusion, we also expressed a FLAG-tag fusion peptide (RP11-834C11.4 sORF-1xFLAG), which revealed a cytoplasmic localization identical to the one observed for the GFP construct (Figure 2—figure supplement 1J). While most sORF-GFP fusion products were ubiquitously distributed throughout transfected cells, LINC00261 sORF4-GFP specifically localized to mitochondria (Figure 2—figure supplement 1K), and LINC00261 sORF7-GFP exhibited a perinuclear accumulation pattern reminiscent of aggresomes (Figure 2—figure supplement 1L). Taken together, our results validate the translation potential of sORFs encoded by pancreatic progenitor-expressed lncRNAs and show that, upon ectopic expression, these translation events result in the production of microproteins with different subcellular localizations.

Deletion phenotypes of translated lncRNAs during hESC pancreatic differentiation

To identify potential functional roles of translated lncRNAs during pancreas development, we selected ten candidates for CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing in hESCs through excision of the lncRNA promoter or entire lncRNA locus (Figure 3A,B). These ten lncRNAs were prioritized based on (i) high expression and endodermal tissue-specificity, (ii) dynamic regulation during pancreas development, (iii) abundant translation of sORFs, and (iv) proximity to TFs with known roles in endoderm and pancreas development. For seven of the selected lncRNAs, translation was highly abundant and reproducibly detected across Ribo-seq replicates: LINC00617 (also known as TUNAR; Lin et al., 2014), GATA6-AS1 (also known as GATA6-AS; Neumann et al., 2018), LINC00261, RP11-834C11.4, SOX9-AS1, MIR7-3HG, and LHFPL3-AS2. Although for two additional lncRNAs the translation potential could not be determined, they were nonetheless included because of a previously reported requirement for definitive endoderm formation (DIGIT, also known as GSC-DT) (Daneshvar et al., 2016) and genomic localization adjacent to the definitive endoderm TF LHX1 (RP11-445F12.1, also known as LHX1-DT). Lastly, LINC00479 was chosen as a non-translated control with expression dynamics and a subcellular localization similar to LINC00261. Of note, for each of the ten selected lncRNAs, we generated at least two independent hESC knockout (KO) clones and used different combinations of single guide RNAs where possible (Figure 3—source data 1A).

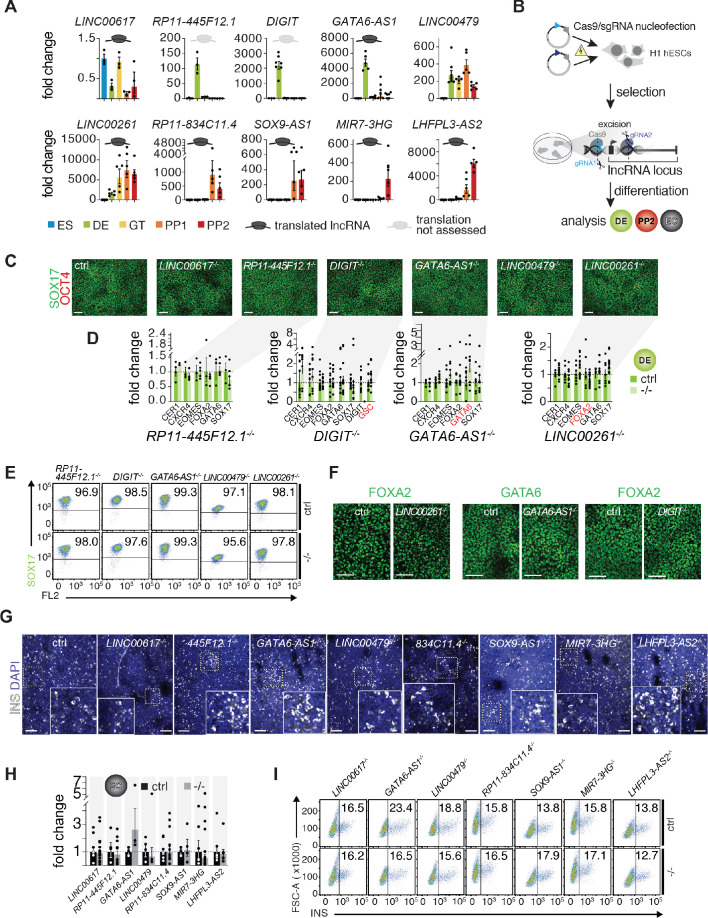

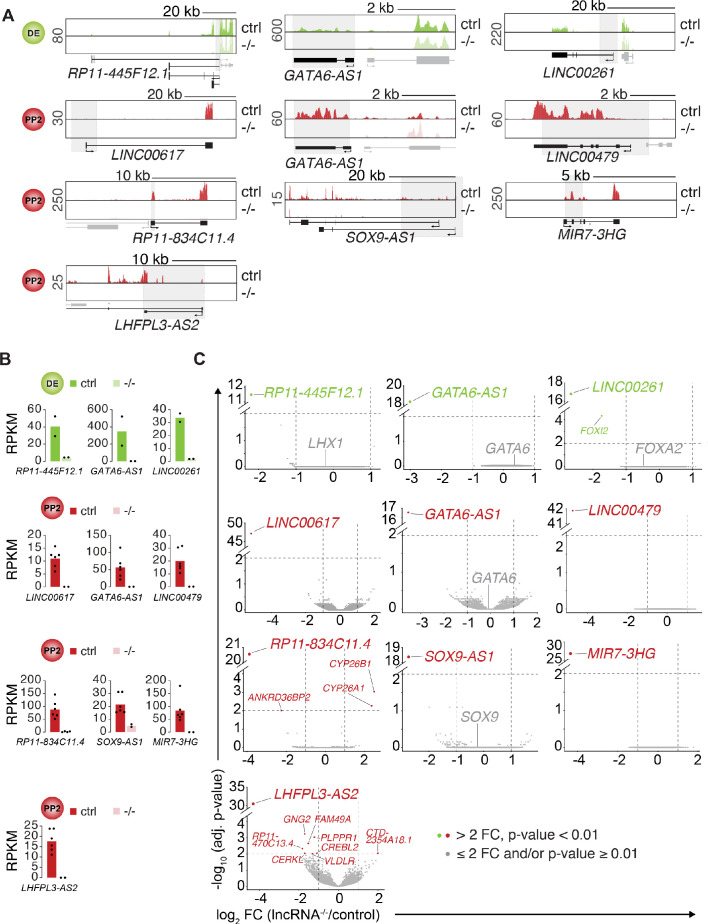

Figure 3. A small-scale CRISPR loss-of-function screen for dynamically expressed and translated lncRNAs during pancreatic differentiation.

(A) qRT-PCR analysis of candidate lncRNAs during pancreatic differentiation of H1 hESCs relative to the ES stage. Data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. (mean of n = 2–6 independent differentiations per stage; from H1 hESCs). Individual data points are represented by dots. See also Figure 3—source data 2. (B) CRISPR-based lncRNA knockout (KO) strategy in H1 hESCs and subsequent phenotypic characterization. (C) Immunofluorescence staining for OCT4 and SOX17 in DE from control (ctrl) and KO cells for the indicated lncRNAs (representative images, n ≥ 3 independent differentiations; at least two KO clones were analyzed). (D) qRT-PCR analysis of DE lineage markers in DE from control and lncRNA KO (-/-) cells. TF genes in cis to the lncRNA locus are highlighted in red. Data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 3–16 replicates from independent differentiations and different KO clones). Individual data points are represented by dots. NS, p-value>0.05; t-test. See also Figure 3—source data 3. (E) Flow cytometry analysis at DE stage for SOX17 in control and KO (-/-) cells for indicated lncRNAs. The line demarks isotype control. Percentage of cells expressing SOX17 is indicated (representative experiment, n ≥ 3 independent differentiations from at least two KO clones). (F) Immunofluorescence staining for FOXA2 or GATA6 in DE from control and LINC00261, GATA6-AS1, and DIGIT KO cells. (G) Immunofluorescence staining for insulin (INS) in endocrine cell stage (EC) from control and KO hESCs for the indicated lncRNAs (representative images, n ≥ 3 independent differentiations from at least two KO clones). Boxed areas (dashed boxes) are shown in higher magnification. (H) qRT-PCR analysis of INS in EC stage cultures from control and lncRNA KO (-/-) hESCs. Data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. (n ≥ 4 replicates from independent differentiations of at least two KO clones). Individual data points are represented by dots. NS, p-value>0.05; t-test. See also Figure 3—source data 4 (I) Flow cytometry analysis at EC stage for INS in control and KO (-/-) cells for indicated lncRNAs. The line demarks isotype control. Percentage of cells expressing insulin is indicated (representative experiment, n ≥ 3 independent differentiations each from at least two KO clones). Scale bars = 100 µm. See also Figure 3—figure supplement 1 and Figure 3—source data 1–4.

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. Minor gene expression changes in definitive endoderm or pancreatic progenitor cells after lncRNA deletion.

We next differentiated each of the lncRNA KO hESC lines stepwise toward the pancreatic endocrine cell stage, conducting up to 16 replicate differentiations for each KO clone. Because LINC00617, RP11-445F12.1, DIGIT, GATA6-AS1, LINC00479, and LINC00261 were first expressed at, or before, the definitive endoderm stage (Figure 3A), we determined whether KO hESCs for these lncRNAs exhibited defects in definitive endoderm formation. Despite efficient lncRNA depletion (Figure 3—figure supplement 1A,B), neither quantification of definitive endoderm marker gene expression by qRT-PCR, nor immunofluorescence staining or flow cytometric analysis of the definitive endoderm marker SOX17 showed differences indicative of impaired endoderm formation in lncRNA KO lines (Figure 3C–E). Importantly, expression of TFs located in the direct vicinity of these lncRNAs, including GSC (DIGIT), LHX1 (RP11-445F12.1), GATA6 (GATA6-AS1), and FOXA2 (LINC00261), was unaffected by the lncRNA KO (Figure 3F, Figure 3—figure supplement 1C, Figure 3—source data 1B–D), arguing against cis-regulation by these lncRNAs. These findings are in contrast to prior reports that have shown a requirement for LINC00261 and DIGIT in definitive endoderm formation and the regulation of neighboring TFs FOXA2 and GSC, respectively (Amaral et al., 2018; Daneshvar et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2015; Swarr et al., 2019).

Next, we further differentiated control and KO lines for eight out of ten lncRNAs toward the endocrine cell stage, excluding DIGIT and RP11-445F12.1 because they are not expressed after the definitive endoderm stage (Figure 3A). In KO hESC lines of seven out of these eight lncRNAs, we observed no effect on pancreatic progenitor cell formation or gene expression, with the exception of a handful of dysregulated genes in LHFPL3-AS2 and RP11-834C11.4 KO cells (Figure 3—figure supplement 1C and Figure 3—source data 1E–K). Furthermore, deletion of seven out of the eight lncRNAs did not impair endocrine cell formation, as determined by quantification of insulin+ cells and insulin mRNA levels (Figure 3G–I). Similar to the RNA expression results obtained at the definitive endoderm stage, deletion of none of the lncRNAs close to pancreatic TFs (e.g. GATA6-AS1 and SOX9-AS1) altered the expression of these TFs, once more arguing against cis-regulation of these TFs by the neighboring lncRNA (Figure 3—figure supplement 1C). Thus, nine out of ten endoderm- and pancreatic progenitor-enriched lncRNAs functionally investigated here appear to be nonessential for induction of the pancreatic fate and formation of insulin+ cells. Furthermore, these lncRNAs do not appear to control the transcript levels of proximal TFs.

LINC00261 knockout impairs endocrine cell development

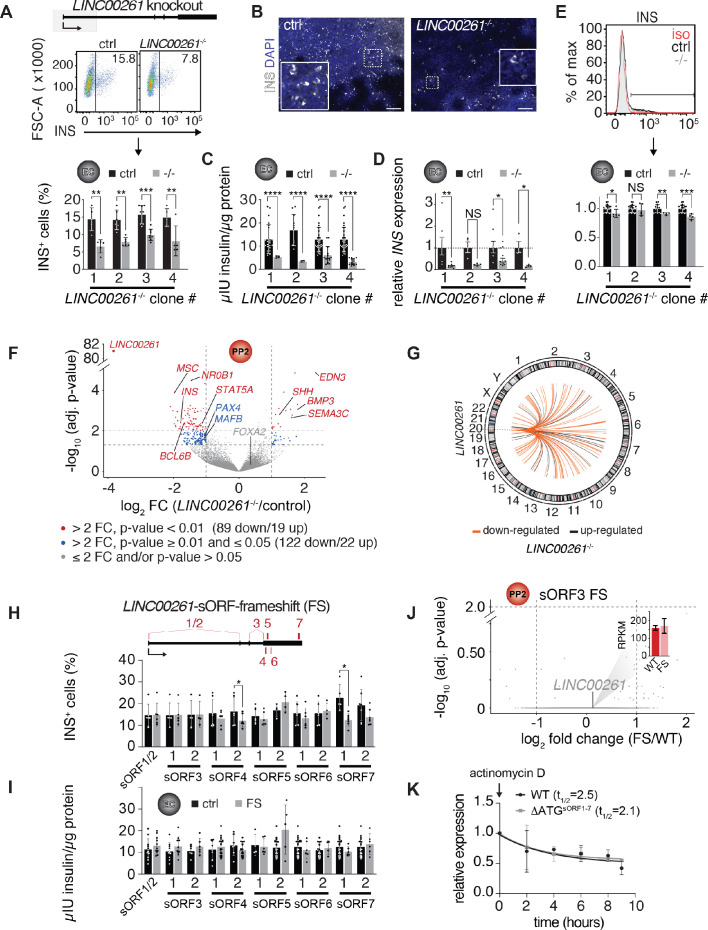

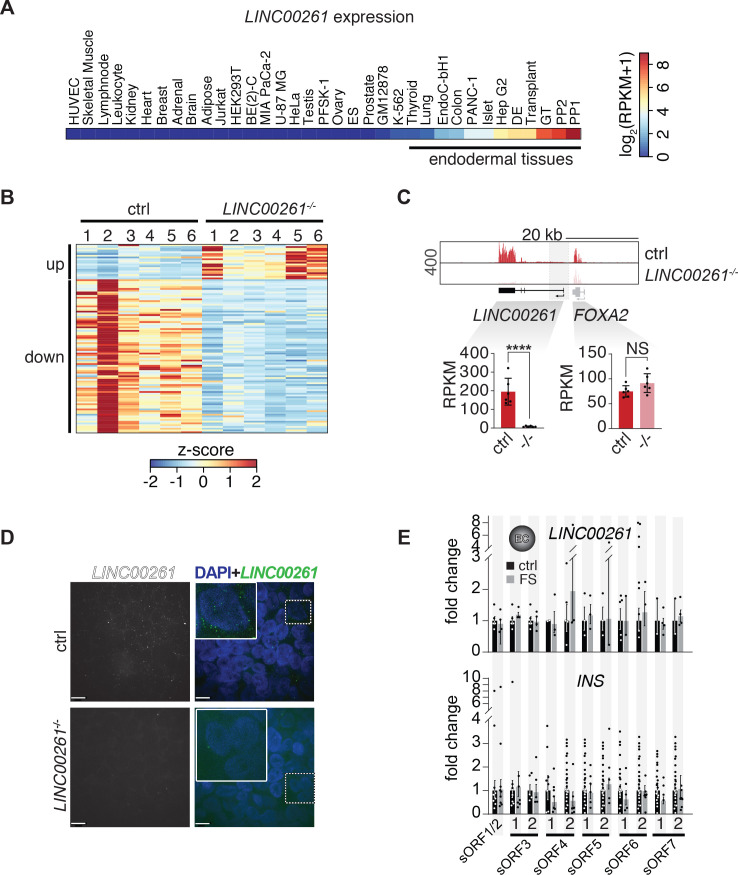

The exception was the endoderm-specific lncRNA LINC00261, which is highly expressed and translated in pancreatic progenitors (Figure 4—figure supplement 1A and Figure 2C). While deletion of LINC00261 caused no discernable phenotype in definitive endoderm (Figure 3C–F and Figure 3—figure supplement 1C), we observed a significant 30–50% reduction in the number of insulin+ cells at the endocrine cell stage (Figure 4A,B). This reduction in insulin+ cell numbers was consistent across four separately derived LINC00261 KO hESC lines, each independently differentiated to endocrine cell stage 5–8 times. In agreement with reduced insulin+ cell numbers, insulin content and insulin mRNA levels were also reduced in LINC00261 KO endocrine stage cultures (Figure 4C,D). Analysis of insulin median fluorescence intensities by flow cytometry further showed no reduction in insulin levels per cell in one LINC00261 KO clone and a mild reduction in the three other clones (Figure 4E), indicating that LINC00261 predominately regulates endocrine cell differentiation rather than maintenance of insulin production in beta cells.

Figure 4. LINC00261 deletion impedes pancreatic endocrine cell differentiation.

(A) Flow cytometry analysis at endocrine cell stage (EC) for insulin (INS) in control (ctrl) and LINC000261-/- H1 hESCs. Top panel: Schematic of the LINC00261 locus. The dashed box represents the genomic deletion. Middle panel: The line demarks isotype control. Percentage of cells expressing INS is indicated (representative experiment, n = 4 deletion clones generated with independent sgRNAs). Bottom panel: Bar graph showing percentages of INS-positive cells. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n = 5 (clone 1), n = 6 (clone 2), n = 8 (clone 3), n = 5 (clone 4) independent differentiations). Individual data points are represented by dots. (B) Immunofluorescence staining for INS in EC stage cultures from control and LINC000261-/- hESCs (representative images, number of differentiations see A). Boxed areas (dashed boxes) are shown in higher magnification. (C) ELISA for INS in EC stage cultures from control and LINC00261-/- hESCs. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n = 3 (clone 1), n = 2 (clone 2), n = 14 (clone 3), n = 13 (clone 4) independent differentiations). Individual data points are represented by dots. (D) qRT-PCR analysis of INS in EC stage cultures from control and LINC00261-/- hESCs. Data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 8 (clone 1), n = 4 (clone 2), n = 10 (clone 3), n = 3 (clone 4) independent differentiations). Individual data points are represented by dots. (E) Quantification of median fluorescence intensity after INS staining of control and LINC00261-/- EC stage cultures. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n = 5 (clone 1), n = 5 (clone 2), n = 4 (clone 3), n = 4 (clone 4) independent differentiations). iso, isotype control. Individual data points are represented by dots. (F) Volcano plot displaying gene expression changes in control versus LINC00261-/- PP2 cells (n = 6 independent differentiations from all four deletion clones). Differentially expressed genes are shown in red (DESeq2;>2 fold change (FC), adjusted p-value<0.01) and blue (>2 fold change, adjusted p-value≥0.01 and≤0.05). Thresholds are represented by vertical and horizontal dashed lines. FOXA2 in cis to LINC00261 is shown in gray (gray dots represent genes with ≤ 2 fold change and/or adjusted p-value>0.05). (G) Circos plot visualizing the chromosomal locations of the 108 genes differentially expressed (DESeq2;>2 fold change (FC), adjusted p-value<0.01) in LINC00261-/- compared to control PP2 cells, relative to LINC00261 on chromosome 20. No chromosome was over- or underrepresented (Fisher test, p-value>0.05 for all chromosomes). (H) Top panel: Schematic of the LINC00261 locus, with the location of its sORFs (1 to 7) marked by vertical red bars. Bottom panel: Flow cytometric quantification of INS-positive cells in control and LINC00261-sORF-frameshift (FS) at the EC stage. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n = 4–7 independent differentiations per clone). (I) ELISA for INS in EC stage cultures from control and LINC00261-sORF-FS hESCs. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n = 3–7 independent differentiations per clone). (J) Volcano plot displaying gene expression changes in control versus LINC00261-sORF3-FS PP2 cells. No gene was differentially expressed (DESeq2;>2 fold change, adjusted p-value<0.01; indicated by dashed horizontal and vertical lines; n = 2 independent differentiations). LINC00261 is shown in gray, the bar graph insert displays LINC00261 RPKM values in control and LINC00261-sORF3-FS PP2 cells. (K) LINC00261 half-life measurements in HEK293T cells transduced with lentivirus expressing either wild type (WT) LINC00261 or ΔATGsORF1-7 LINC00261 (mutant in which the ATG start codons of sORFs 1–7 were changed to non-start codons). HEK293T were treated with the transcription inhibitor actinomycin D and RNA isolated at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 9 hr post actinomycin D addition. LINC00261 expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR relative to the TBP gene. Data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 3 biological replicates for each assay time point). *, p-value<0.05; **, p-value<0.01; ***, p-value<0.001; ****, p-value<0.0001; NS, p-value>0.05; t-test. Scale bars = 100 µm. See also Figure 4—figure supplement 1 and Figure 4—source data 1–3.

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. Characterization of LINC00261-deleted pancreatic progenitor cells.

To determine the molecular effects of LINC00261 deletion, we performed RNA-seq in pancreatic progenitors derived from LINC00261 KO and control hESCs. Similar to the absence of cis-regulatory functions observed in the other lncRNA KOs, we found no evidence for cis-regulation of FOXA2 by LINC00261 (Figure 4F and Figure 4—figure supplement 1C). However, we observed downregulation of the TFs MAFB and PAX4 (Figure 4F, Figure 4—figure supplement 1B, Figure 4—source data 1A), which are important regulators of beta cell differentiation (Artner et al., 2007; Sosa-Pineda et al., 1997). Of note, genes differentially expressed in LINC00261 KO cells mapped to all chromosomes and showed no enrichment for chromosome 20 where LINC00261 resides (Figure 4G). These results suggest a trans- rather than cis-regulatory function for LINC00261, consistent with its predominantly cytosolic localization, translation, and diffuse distribution within the nucleus (Figure 2C and Figure 4—figure supplement 1D). Trans-regulatory roles of LINC00261 have also been observed in previous studies (Aguet et al., 2019; Shi et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2019). This potential trans functionality prompted us to further investigate whether LINC00261's coding or noncoding features are essential for endocrine cell differentiation.

One-by-one disruption of LINC00261's sORFs does not impact endocrine cell differentiation

We established that LINC00261 harbors multiple distinct and highly translated sORFs, which raises the possibility that the translation of these sORFs is functionally important for endocrine cell differentiation. To systematically discriminate LINC00261's coding and noncoding roles, we individually mutated its seven most highly translated sORFs independently in hESCs, leaving the lncRNA sequence, and hence any noncoding function coupled to RNA sequence or structure, grossly intact. Each of these hESC lines either carried a homozygous frameshift mutation near the microprotein's N-terminus (for sORFs 1–6) or a full sORF deletion (sORF7; Figure 4—source data 1B). After verifying that CRISPR editing of the LINC00261 locus did not impact LINC00261 transcript levels (Figure 4—figure supplement 1E), we quantified (i) insulin mRNA levels, (ii) insulin+ cells, and (iii) total insulin content in endocrine cell stage cultures. We observed no difference between sORF loss-of-function and control hESC lines for most of these endpoints (Figure 4H,I and Figure 4—figure supplement 1E), although we noticed that the number of insulin+ cells, but not the amount of insulin produced, was reduced in one of the two sORF4 and sORF7 KO clones. Transcriptome analysis of pancreatic progenitors with frameshifts in sORF3 (the most highly translated LINC00261-sORF; Figure 2C and Figure 2—source data 1D) revealed no differentially expressed genes between LINC00261-sORF3 frameshift and control cells (Figure 4J and Figure 4—source data 1C), contrasting observations in LINC00261 RNA KO pancreatic progenitors (Figure 4F and Figure 4—source data 1A). These results indicate that there is not one dominant LINC00261 sORF that is required for endocrine cell formation, suggesting a functional role of the LINC00261 transcript and not the individual sORFs mutated here. However, it is possible that the different sORFs, or the microproteins translated from these sORFs, are functionally redundant and capable of phenotypic rescue.

It has been suggested that ribosome association can control lncRNA transcript levels by inducing nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) (Carlevaro-Fita et al., 2016; Tani et al., 2013). Therefore, we determined whether the presence of multiple sORFs could regulate LINC00261 stability. To this end, we simultaneously mutated start codons of all seven sORFs (ΔATGsORF1-7 LINC00261) and expressed either wild type or ΔATGsORF1-7 LINC00261 ectopically in HEK293T cells, where LINC00261 is normally not expressed. LINC00261 half-life measurements upon transcriptional inhibition with actinomycin D revealed no difference in LINC00261 levels between wild type and ΔATGsORF1-7 LINC00261 (Figure 4K), suggesting that the translation of the seven sORFs does not reduce LINC00261 transcript stability.

In sum, through the systematic, one-by-one removal of sORFs within a highly translated lncRNA with functional importance for pancreatic endocrine cell formation, we found no evidence to implicate the individual sORFs, or the microproteins they produce, in endocrine cell development. Although LINC00261's sORFs may share functional redundancy or have developmental roles that do not affect the production of insulin+ cells, our findings strongly suggest that by themselves, these sORFs are not functionally required for endocrine cell formation.

Discussion

Limited cis-regulatory consequences of lncRNA deletion

In this study we globally characterized molecular features of lncRNAs expressed during progression of hESCs toward the pancreatic lineage, including their subcellular localization and potential to be translated. We performed a phenotypic CRISPR loss-of-function screen, focusing on ten developmentally regulated, highly expressed, and highly translated lncRNAs proximal to TFs known to regulate pancreas development. The first important observation from this screen is that we found no evidence to implicate the lncRNAs LINC00261, DIGIT, GATA6-AS1, SOX9-AS1, and RP11-445F12.1 in the cis-regulation of their neighboring TFs FOXA2, GSC, GATA6, SOX9, and LHX, respectively, despite tight transcriptional coregulation of the lncRNA-TF pairs.

Contrasting our findings, a number of studies have reported cis-regulation of FOXA2 by LINC00261 (Amaral et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2015; Swarr et al., 2019). However, several lines of evidence strongly support the conclusion that FOXA2 is not regulated by LINC00261 in our experimental system. First, we examined FOXA2 mRNA expression in LINC000261-/- cells at both the definitive endoderm and pancreatic progenitor cell stages. Second, we analyzed FOXA2 expression using two independent methods, namely qRT-PCR and RNA-seq. Third, immunofluorescence staining in definitive endoderm revealed no difference in FOXA2 protein expression between control and LINC00261-/- cells.

While different cellular contexts and species could explain the discrepancy between our findings and the ones by Amaral et al., 2018 and Swarr et al., 2019, Jiang et al., 2015 reported FOXA2 regulation by LINC00261 in hESC-derived definitive endoderm. One important difference between our study and the study by Jiang et al. is that we employed CRISPR-Cas9-mediated deletion, whereas Jiang et al. used shRNA-mediated knockdown to inactivate LINC00261. It is possible that lncRNA deletion triggers compensatory mechanisms that are not activated after shRNA-mediated knockdown. For coding genes, mutant mRNA degradation has been shown to trigger genetic compensation (El-Brolosy et al., 2019). Another difference between our study and the one by Jiang et al. is that our differentiation protocol was more efficient in generating definitive endoderm. It is conceivable that the stability of the cell fate and identity of neighboring cells could influence how LINC00261 loss-of-function affects gene regulation.

Translation of short, non-canonical ORFs in lncRNAs: regulatory, microprotein-producing, or just tolerated?

Although lncRNAs are now appreciated as a novel and abundant source of sORF-encoded biologically active microproteins (Makarewich and Olson, 2017), it remains largely unknown which translation events lead to the production of microproteins, which solely have regulatory potential, or which have no functional roles, but are not negatively selected against. The cytosolic localization and translation of many RNAs classified as lncRNAs provides a strong rationale for considering both, coding and noncoding functions.

In this study, we identified the translated lncRNA LINC00261 as a novel regulator of pancreatic endocrine cell differentiation, as evidenced by a severe reduction in insulin+ cell numbers upon LINC00261 deletion. We show that LINC00261 transcripts are highly abundant in pancreatic progenitors and, albeit present in the nucleus, are predominantly localized to the cytoplasm. Here, they frequently associate with ribosomes which leads to the translation of multiple independent sORFs. We show that the sORFs are capable of producing microproteins with distinct subcellular localizations upon expression in vitro. In contrast to LINC00261 deletion, individual frameshift mutations in each of LINC00261's sORFs did not impair endocrine cell development, suggesting that the requirement of LINC00261 for endocrine cell development can be uncoupled from the translation of its multiple sORFs. However, this does not exclude the possibility that these sORFs or the microproteins they produce could possess functions that become relevant under specific environmental, developmental, or disease conditions not examined in this study.

We found that mutating all translated LINC00261 sORFs simultaneously, thereby likely reducing LINC00261's ability to bind ribosomes, did not affect LINC00261 transcript levels in HEK293T cells. This indicates that, in contrast to reports suggesting that translated sORFs can regulate RNA stability by promoting nonsense-mediated RNA decay (Carlevaro-Fita et al., 2016; Tani et al., 2013), the high translation levels and multiple sORFs of LINC00261 are unlikely to be part of a LINC00261 decay pathway. It would have been interesting to determine how concurrent mutation of all sORFs in LINC00261 affects pancreatic cell differentiation. However, given the size of the LINC00261 locus and the many sORFs, such an approach comes with technical challenges and significant caveats.

LINC00261 - a potential trans regulator of endocrine cell differentiation?

Several lines of evidence suggest that LINC00261 regulates endocrine cell differentiation in trans: (i) LINC00261 transcripts show a diffuse distribution in multiple subcellular compartments, (ii) genes differentially expressed in LINC00261 KO cells are randomly distributed throughout the genome, (iii) expression of the nearby TF FOXA2 is not affected by LINC00261 deletion. Such a trans regulatory mechanism for LINC00261 is supported by a recent study from the GTEx Consortium, where LINC00261 is highlighted as one of a few lncRNAs that forms a potential trans regulatory hotspot through genetic interactions that influence the expression of multiple distant genes (Aguet et al., 2019). Consistent with its preferential cytosolic localization, and further supporting the notion of a trans regulatory mechanism, LINC00261 has been suggested to regulate gene expression through non-nuclear mechanisms, e.g. by preventing nuclear translocation of β-catenin (Wang et al., 2017) or by acting as a miRNA sponge (Shi et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019; Yan et al., 2019). Although our observations and current literature strongly hint to a function in trans independent of the produced microproteins, the exact mechanism by which LINC00261 regulates gene expression in pancreatic progenitors remains to be determined.

Limitations and future directions

In this study, we have characterized the role of translated lncRNAs, and in particular LINC00261, in a hESC differentiation system that mimics pancreas development. However, there are several potential limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the results. First, a small subset of analyses in this study was based on low numbers of replicate differentiations, in particular the cytosolic versus nuclear fractionation RNA-seq experiments, where only two replicate differentiations into pancreatic progenitor cells were analyzed. Second, although we provide evidence that LINC00261 can produce microproteins using Ribo-seq, which is further supported by in vitro translation assays and overexpression of LINC00261 constructs with different in-frame tags, we provide no protein-level evidence for the endogenous production and stability of LINC00261's microproteins in this differentiation system or in human pancreas development in vivo. Moreover, due to its highly specific expression pattern, LINC00261 has not been previously detected by sORF analyses in other cell types (Bazzini et al., 2014; Calviello et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2020; Ji et al., 2015; Martinez et al., 2020; Prensner et al., 2020; Raj et al., 2016; van Heesch et al., 2019). Even though we show microprotein production in vitro, it is possible that the act of translation has a key regulatory role rather than the protein products of LINC00261’s sORFs. Lastly, LINC00261's microproteins and sORFs may have redundant functions, which could explain why deletion of individual sORFs produces no apparent phenotype. Thus, despite limited sequence similarity and stark differences in translation rates between the identified translated sORFs in LINC00261, we cannot rule out that different microproteins produced by LINC00261 compensate when one sORF is deleted. Future studies of LINC00261's precise mechanisms of action could be aimed at further dissecting the potential regulatory features of sORF translation and possibility of redundancy between sORFs.

Conclusions

In summary, we here present a rigorous, in-depth characterization of dynamically regulated and translated lncRNAs in a disease-relevant cell model of human developmental progression. Our combination of ultra-high-coverage RNA- and Ribo-seq, in vitro protein-level validation of microprotein production and localization, and the systematic, one-by-one deletion of all individual microproteins encoded by a single translated lncRNA, not only provides a detailed resource of translated 'non-canonical' sORFs and their microproteins in pancreatic development, but also serves as a blueprint for the systematic functional interrogation of translated lncRNAs.

Materials and methods

Key resources table.

| Reagent type (species) or resource |

Designation | Source or reference |

Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene (Homo sapiens) | LINC00617; TUNAR | Ensembl 87 | ENSG00000250366 | |

| Gene (Homo sapiens) | RP11-445F12.1; LHX-DT | Ensembl 87 | ENSG00000250366 | |

| Gene (Homo sapiens) | DIGIT; GSC-DT | HGNC and NCBI RefSeq |

HGNC:53074; NCBI RefSeq 108868751 | |

| Gene (Homo sapiens) | GATA6-AS1; GATA6-AS | Ensembl 87 | ENSG00000277268 | |

| Gene (Homo sapiens) | LINC00479 | Ensembl 87 | ENSG00000236384 | |

| Gene (Homo sapiens) | LINC00261; DEANR1; ALIEN; onco-lncRNA-17; lnc-FOXA2-2 | Ensembl 87 | ENSG00000236384 | |

| Gene (Homo sapiens) | RP11-834C11.4 | Ensembl 87 | ENSG00000250742 | |

| Gene (Homo sapiens) | SOX9-AS1 | Ensembl 87 | ENSG00000234899 | |

| Gene (Homo sapiens) | MIR7-3HG | Ensembl 87 | ENSG00000176840 | |

| Gene (Homo sapiens) | LHFPL3-AS2 | Ensembl 87 | ENSG00000225329 | |

| Strain, strain background (Escherichia coli) | Stbl3 | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# C737303 | Chemically competent cells |

| Strain, strain background (Escherichia coli) | DH5α | New England Biolabs | Cat# C2987I | Chemically competent cells |

| Cell line (Homo sapiens) | H1 (embryonic stem cells) | WiCell Research Institute | NIHhESC-10–0043, RRID:CVCL_9771 | |

| Cell line (Homo sapiens) | HEK293T (embryonic kidney) | ATCC | Cat# CRL-3216, RRID:CVCL_0063 | |

| Antibody | anti-human OCT-4A (Rabbit monoclonal) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 2890, RRID:AB_2167725 |

IF (1:1000) |

| Antibody | anti-human SOX17 (Goat polyclonal) | R and D Systems | Cat# AF1924, RRID:AB_355060 |

IF (1:250) |

| Antibody | anti-human FOXA2 (Goat polyclonal) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-6554, RRID:AB_2262810 | IF (1:250) |

| Antibody | anti-human GATA6 (Goat polyclonal) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-9055, RRID:AB_2108768 | IF (1:50) |

| Antibody | anti-human Insulin (Guinea pig polyclonal) |

Dako | Cat# A0564, RRID:AB_10013624 | IF (1:1000) |

| Antibody | Alexa Fluor 488 AffiniPure anti-Goat IgG (Donkey polyclonal) | Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs | Cat# 706-545-148, RRID:AB_2340472 | IF (1:1000) |

| Antibody | Alexa Fluor 488 AffiniPure anti-Rabbit IgG (Donkey polyclonal) | Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs | Cat# 711-545-152, RRID:AB_2313584 | IF (1:1000) |

| Antibody | Cy3 AffiniPure anti-Goat IgG (Donkey polyclonal) | Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs | Cat# 705-165-147, RRID:AB_2307351 | IF (1:1000) |

| Antibody | anti-human Insulin-PE (Rabbit monoclonal) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 8508S, RRID:AB_11179076 | Flow cytometry (1:50) |

| Antibody | anti-human SOX17-PE (Mouse monoclonal) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 561591, RRID:AB_10717121 | Flow cytometry (5 ul per test) |

| Antibody | IgG-PE (Rabbit monoclonal) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 5742S, RRID:AB_10694219 | Flow cytometry isotype control antibody (1:50) |

| Antibody | IgG1, κ antibody (Mouse monoclonal) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 556650, RRID:AB_396514 | Flow cytometry isotype control antibody (1:50) |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pSpCas9(BB)−2A-Puro (Px459; V2.0) | Feng Zhang | RRID:Addgene_62988 | Cas9 from S. pyogenes with 2A-Puro, and cloning backbone for sgRNA |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pSpCas9(BB)−2A-GFP (PX458) | Feng Zhang | RRID:Addgene_48138 | Cas9 from S. pyogenes with 2A-EGFP, and cloning backbone for sgRNA |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pCMVR8.74 | Didier Trono | RRID:Addgene_22036 | 2nd generation lentiviral packaging plasmid |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pMD2.G | Didier Trono | RRID:Addgene_12259 | VSV-G envelope expressing plasmid |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pENTR/D-TOPO-LINC00261 | Kurian et al., 2015 (PMID:25739401) | Leo Kurian (University of Cologne) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-GFP.WPRE | Didier Trono | RRID:Addgene_12252 | 3rd generation lentiviral backbone |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-LINC00261.WPRE | This paper | Transient (transfection) or stable (lentiviral integration) expression of wild type LINC00261 | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-ΔATGsORF1-7 LINC00261.WPRE | This paper | Transient (transfection) or stable (lentiviral integration) expression of ΔATGsORF1-7 LINC00261 | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-LINC00261-sORF1-GFP.WPRE | This paper | Transient (transfection) or stable (lentiviral integration) expression of LINC00261-sORF1-GFP fusion protein | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-LINC00261-sORF2-GFP.WPRE | This paper | Transient (transfection) or stable (lentiviral integration) expression of LINC00261-sORF2-GFP fusion protein | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-LINC00261-sORF3-GFP.WPRE | This paper | Transient (transfection) or stable (lentiviral integration) expression of LINC00261-sORF3-GFP fusion protein | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-LINC00261-sORF4-GFP.WPRE | This paper | Transient (transfection) or stable (lentiviral integration) expression of LINC00261-sORF4-GFP fusion protein | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-LINC00261-sORF5-GFP.WPRE | This paper | Transient (transfection) or stable (lentiviral integration) expression of LINC00261-sORF5-GFP fusion protein | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-LINC00261-sORF6-GFP.WPRE | This paper | Transient (transfection) or stable (lentiviral integration) expression of LINC00261-sORF6-GFP fusion protein | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-LINC00261-sORF7-GFP.WPRE | This paper | Transient (transfection) or stable (lentiviral integration) expression of LINC00261-sORF7-GFP fusion protein | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-LINC00261-sORF3-FS-GFP.WPRE | This paper | LINC00261-sORF3-frameshift-GFP control plasmid | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-LINC00261-sORF2-STOP-GFP.WPRE | This paper | LINC00261-sORF2-STOP-GFP control plasmid | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-RP11-834C11.4-sORF-GFP.WPRE | This paper | Transient (transfection) or stable (lentiviral integration) expression of RP11-834C11.4-sORF-GFP fusion protein | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-RP11-834C11.4-sORF-FLAG.WPRE | This paper | Transient (transfection) or stable (lentiviral integration) expression of RP11-834C11.4-sORF-FLAG fusion protein | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-MIR7-3HG-sORF-GFP.WPRE | This paper | Transient (transfection) or stable (lentiviral integration) expression of MIR7-3HG-sORF-GFP fusion protein | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-RP11-LHFPL3-AS2-sORF-GFP.WPRE | This paper | Transient (transfection) or stable (lentiviral integration) expression of LHFPL3-AS2-sORF-GFP fusion protein | |

| Peptide, recombinant protein | Activin A | R and D Systems | Cat# 338-AC/CF | |

| Peptide, recombinant protein | Wnt3a | R and D Systems | Cat# 1324-WN-010 | |

| Peptide, recombinant protein | KGF/FGF7 | R and D Systems | Cat# 251 KG | |

| Peptide, recombinant protein | Noggin | R and D Systems | Cat# 3344 NG-050 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | RNeasy Mini Kit |

QIAGEN | Cat# 15596018 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | RNA Clean and Concentrator−25 | Zymo Research | Cat# R1018 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | Paris Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific |

Cat# AM1921 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | RNase-Free DNase Set (50) | QIAGEN | Cat# 79254 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | TURBO DNA-free Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# AM1907 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | TruSeq Ribo Profile (Mammalian) Library Prep Kit | Illumina | Cat# RPYSC12116 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep | Illumina | Cat# 20020594 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Gold | Illumina | Cat# 20020599 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | KAPA mRNA HyperPrep Kit | Roche | Cat# KK8581 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | High Sensitivity D1000 ScreenTape | Agilent Technologies | Cat# 5067–5584 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | RNA ScreenTape | Agilent Technologies | Cat# 5067–5576 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | RNA ScreenTape Sample Buffer | Agilent Technologies | Cat# 5067–5577 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | RNA ScreenTape Ladder | Agilent Technologies | Cat# 5067–5578 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | Qubit ssDNA assay kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# Q10212 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | KOD Xtreme DNA Hotstart Polymerase | Millipore | Cat# 71975 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | GoTaq Green Master Mix | Promega | Cat# M7123 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | TOPO TA Cloning Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# K452001 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | Monarch Plasmid Miniprep Kit | NEB | Cat# T1010L | |

| Commercial assay or kit | MinElute PCR Purification Kit | QIAGEN | Cat# 28006 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit | Bio-Rad | Cat# 1708890 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | iQ SYBR Green Supermix | Bio-Rad | Cat# 1708880 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | Human Stem Cell Nucleofector Kit 2 |

Lonza | Cat# VPH-5022 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | XtremeGene 9 DNA Transfection Reagent | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 06365779001 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | Cytofix/Cytoperm W/Golgi Stop Kit | BD Biosciences | Cat# 554715 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | Insulin ELISA Jumbo | Alpco | Cat# 80-INSHU-E10.1 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 23227 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | TnT Coupled Wheat Germ Extract System | Promega | Cat# L4130 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | Penicillin-Streptomycin | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 15140122 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | Puromycin dihydrochloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# P8833 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | ALK5 Inhibitor II | Enzo Life Sciences | Cat# ALX-270–445 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | Retinoic Acid | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# R2625 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | Ascorbic Acid | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A4403-100MG | |

| Chemical compound, drug | LDN-193189 | Stemgent | Cat# 04–0074 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | SANT-1 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# S4572 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | TPB | Calbiochem | Cat# 565740 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | TGFβ R1 kinase inhibitor IV | EMD Biosciences | Cat# 616454 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | KAAD-Cyclopamine | Toronto Research Chemicals | Cat# K171000 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | TTNPB | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# T3757 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | Cycloheximide | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# C7698 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | Actinomycin D | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A9415 | |

| Chemical compound, drug |

Polyethylenimine (PEI) | Polysciences | Cat# 23966–1 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | Hoechst 33342, Trihydrochloride, Trihydrate | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# H3570 | |

| Chemical compound, drug |

MitoSOX Red | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# M36008 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | D-(+)-Glucose Solution, 45% | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# G8769 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | Sodium Bicarbonate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# NC0564699 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | ROCK Inhibitor Y-27632 | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat# 72305 | |

| Software, algorithm | Flowjo-v10 | FlowJo, LLC | RRID:SCR_008520 | http://www.flowjo.com/download-newest-version/ |

| Software, algorithm | STAR 2.5.3a | Dobin et al., 2013 | RRID:SCR_015899 | https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR |

| Software, algorithm | Bowtie 1.1.1 | Langmead et al., 2009 | RRID:SCR_005476 | http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/index.shtml |

| Software, algorithm | Cufflinks 2.2.1 | Trapnell et al., 2010 | RRID:SCR_014597 | https://github.com/cole-trapnell-lab/cufflinks |

| Software, algorithm | HTSeq 0.6.1 | Anders et al., 2015 | RRID:SCR_005514 | https://htseq.readthedocs.io/en/master/install.html |

| Software, algorithm | DEseq2 1.10.1 | Love et al., 2014 | RRID:SCR_015687 | https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/devel/bioc/html/DESeq2.html |

| Software, algorithm | RiboTaper | Calviello et al., 2016 | RRID:SCR_018880 | https://ohlerlab.mdc-berlin.de/software/RiboTaper_126/ |

| Software, algorithm | R 3.5.0 | RRID:SCR_001905 | https://cran.r-project.org/ | |

| Software, algorithm | SAMtools 1.3 | Li et al., 2009 | RRID:SCR_002105 | https://github.com/samtools/samtools |

| Software, algorithm | BEDTools 2.17.0 | Quinlan and Hall, 2010 | RRID:SCR_006646 | https://bedtools.readthedocs.io/en/latest/content/installation.html |

| Software, algorithm | HOMER 4.10 | Heinz et al., 2010 | RRID:SCR_010881 | http://homer.ucsd.edu/homer/download.html |

| Software, algorithm | GREAT 3.0.0 | McLean et al., 2010 | RRID:SCR_005807 | http://great.stanford.edu/public/html/ |

| Software, algorithm | Adobe Illustrator CS5 | Adobe | RRID:SCR_010279 | |

| Software, algorithm | Adobe Photoshop CS5 | Adobe | RRID:SCR_014199 | |

| Software, algorithm | GraphPad Prism v7.05 | GraphPad Software, LLC | RRID:SCR_002798 | |

| Other | Novex 16% Tricine Protein Gel | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# EC66955BOX | |

| Other | Novex Tricine SDS Sample Buffer (2X) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# LC1676 | |

| Other | Immobilon-PSQ PVDF Membrane | Merck Millipore | Cat# ISEQ00010 | |

| Other | Stellaris RNA FISH Hybridisation Buffer | LGC Biosearch Technologies | Cat# SMF-HB1-10 | |

| Other | Stellaris RNA FISH Wash Buffer A | LGC Biosearch Technologies | Cat# SMF-WA1-60 | |

| Other | Stellaris RNA FISH Wash Buffer B | LGC Biosearch Technologies | Cat# SMF-WB1-20 | |

| Other | QuickExtract DNA Extraction Solution | Lucigen | Cat# QE09050 | |

| Other | Vectashield Antifade Mounting Medium | Vector Laboratories | Cat# H-1000 | |

| Other | FastDigest BpiI | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# FD1014 | |

| Other | FastDigest BshTI | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# FERFD1464 | |

| Other | FastDigest SalI | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# FD0644 | |

| Other | TRIzol | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 15596018 | |

| Other | Matrigel | Corning | Cat# 356231 | |

| Other | GlutaMAX | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 35050061 | |

| Other | DPBS (without calcium and magnesium) | Corning | Cat# 45000–434 | |

| Other | mTeSR1 Complete Kit - GMP | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat# 85850 | |

| Other | RPMI 1640 Medium, HEPES | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 22400–089 | |

| Other | DMEM/F12 with L-Glutamine, HEPES | Corning | Cat# 45000–350 | |

| Other | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium | Corning | Cat# 45000–312 | |

| Other | HyClone Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Medium | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# SH30081.FS | |

| Other | MCDB 131 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 10372–019 | |

| Other | Opti-MEM Reduced Serum Medium | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 31985062 | |

| Other | Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium-Ethanolamine (ITS-X) (100X) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 51500–056 | |

| Other | B-27 Supplement (50X) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 17504044 | |

| Other | Bovine Albumin Fraction V (7.5%) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 15260037 | |

| Other | Fetal Bovine Serum | Corning | Cat# 35011CV | |

| Other | Donkey Serum | Gemini Bio-Products | Cat# 100-151/500 | |

| Other | Fatty Acid-Free BSA | Proliant Biologicals | Cat# 68700 | |

| Other | Accutase | eBioscience | Cat# 00-4555-56 |

HEK293T cell culture

HEK293T cells (female) were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 using Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Corning; 4.5 g/L glucose, [+] L-glutamine, [-] sodium pyruvate) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Corning, Cat# 35011CV). HEK293T cells were purchased from ATCC (Cat# CRL-3216, RRID:CVCL_0063) and tested for mycoplasma prior to the experiment.

hESC culture and maintenance

H1 hESCs (male) were obtained from WiCell (NIHhESC-10–0043, RRID:CVCL_9771) and tested for mycoplasma on a yearly basis. H1 hESCs were grown in feeder-independent conditions on Matrigel-coated dishes (Corning, Cat# 356231) with mTeSR1 media (STEMCELL Technologies, Cat# 85850). Propagation was carried out by passing the cells every 3 to 4 days using Accutase (eBioscience, Cat# 00-4555-56) for enzymatic cell dissociation. hESC research was approved by the University of California, San Diego, Institutional Review Board and Embryonic Stem Cell Research Oversight Committee.

Pancreatic differentiation

H1 hESCs were differentiated in a monolayer format as previously described (Rezania et al., 2012), with minor modifications. Undifferentiated hESCs were seeded into 24-wells at 0.4 × 106 cells/well in 500 µl mTeSR1 medium. The next day the cells were washed in RPMI media (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 22400–089) and then differentiated with daily media changes. In addition to GlutaMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 35050061), RPMI medium was supplemented with 0.12% (w/v) NaHCO3 and 0.2% (Day 0) or 0.5% (Day 1–3) (v/v) FBS (Corning, Cat# 35011CV). DMEM/F12 medium (Corning, Cat# 45000–350) was supplemented with 2% (v/v) FBS and 0.2% (w/v) NaHCO3, and DMEM High Glucose medium (HyClone, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# SH30081.FS) was supplemented with 0.5X B-27 supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 17504044). Human Activin A, mouse Wnt3a, human KGF, and human Noggin were purchased from R and D Systems (Cat# 338-AC/CF, Cat# 1324-WN-010, Cat# 251 KG, Cat# 3344 NG-050). Other media components included TGFβ R1 kinase inhibitor IV (EMD Bioscience, Cat# 616454), KAAD-Cyclopamine (Toronto Research Chemicals, Cat# K171000), the retinoid analog TTNPB (Sigma Aldrich, Cat# T3757), the protein kinase C activator TPB (EMD Chemicals, Cat# 565740), the BMP type one receptor inhibitor LDN-193189 (Stemgent, Cat# 04–0074), and an inhibitor of the TGF-β type one activin like kinase receptor ALK5, ALK5 inhibitor II (Enzo Life Sciences, Cat# ALX-270–445).

Stage 1 (DE; collection on day 3):

Day 0: RPMI/FBS, 100 ng/mL Activin A, 25 ng/mL mouse Wnt3a

Day 1–2: RPMI/FBS, 100 ng/mL Activin A

Stage 2 (GT; collection on day 6):

Day 3: DMEM/F12/FBS, 2.5 µM TGFβ R1 kinase inhibitor IV, 50 ng/mL KGF

Day 4–5: DMEM/F12/FBS, 50 ng/mL KGF

Stage 3 (PP1; collection on day 10):

Day 6–9: DMEM/B27, 3 nM TTNPB, 0.25 mM KAAD-Cyclopamine, 50 ng/mL Noggin

Stage 4 (PP2; collection on day 13):

Day 10–12: DMEM/B27, 100 nM ALK5 inhibitor II, 100 nM LDN-193189, 500 nM TPB, 50 ng/mL Noggin

Stage 5 (endocrine cell stage; collection on day 16):

Day 13–15: DMEM/B27, 100 nM ALK5 inhibitor II, 100 nM LDN-193189, 500 nM TPB, 50 ng/mL Noggin

For ribosome profiling experiments, a scalable suspension culture protocol was employed for differentiation of H1 cells to the PP2 stage (Rezania et al., 2014). Undifferentiated hESCs were aggregated by preparing a single cell suspension in mTeSR1 media (STEMCELL Technologies; supplemented with 10 µM Y-27632) at 1 × 106 cells/mL and overnight culture in six-well ultra-low attachment plates (Costar) with 5.5 ml per well on an orbital rotator (Innova2000, New Brunswick Scientific) at 100 rpm. The following day, undifferentiated aggregates were washed in MCDB 131 media (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 10372–019) and then differentiated using a multistep protocol with daily media changes and continued orbital rotation at either 100 rpm or at 115 rpm from days 8 to 14. In addition to 1% GlutaMAX (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 35050061) and 10 mM (days 0–10) or 20 mM (days 11–14) glucose, MCDB 131 media was supplemented with 0.5% (days 0–5) or 2% (days 6–14) fatty acid-free BSA (Proliant Biologicals, Cat# 68700), 1.5 g/L (days 0–5 and days 11–14) or 2.5 g/L (days 6–10) NaHCO3 (Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.25 mM ascorbic acid (days 3–10).

Human Activin A, mouse Wnt3a, and human KGF were purchased from R and D Systems (Cat# 338-AC/CF, Cat# 1324-WN-010, Cat# 251 KG). Other media components included Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium-Ethanolamine (ITS-X; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 51500–056; days 6–10), retinoic acid (RA) (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# R2625), the sonic hedgehog pathway inhibitor SANT-1 (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# S4572), the protein kinase C activator TPB (EMD Chemicals, Cat# 565740), the BMP type one receptor inhibitor LDN-193189 (Stemgent, Cat# 04–0074), and the TGFβ type one activin like kinase receptor ALK5 inhibitor, ALK5 inhibitor II (Enzo Life Sciences, Cat# ALX-270–445).

Stage 1 (DE; collection on day 3):

Day 0: MCDB 131, 100 ng/mL Activin, 25 ng/mL mouse Wnt3a

Day 1–2: MCDB 131, 100 ng/mL Activin A

Stage 2 (GT; collection on day 6):

Day 3 – Day 5: MCDB 131, 50 ng/mL KGF

Stage 3 (PP1; collection on day 8)

Day 6 – Day 7: MCDB 131, 50 ng/mL KGF, 0.25 µM SANT-1, 1 µM RA 100 nM LDN-193189, 200 nM TPB

Stage 4 (PP2; collection on day 11):

Day 8 – Day 10: MCDB 131, 2 ng/mL KGF, 0.25 µM SANT-1, 0.1 µM RA, 200 nM LDN-193189, 100 nM TPB

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated lncRNA knockout

To generate clonal lncRNA knockout hESC lines, combinations of pSpCas9(BB)−2A-Puro plasmid pairs (Addgene plasmid #62988, RRID:Addgene_62988, gift from Feng Zhang) expressing Cas9 and single sgRNAs targeting upstream and downstream regions of the lncRNA promoter/locus were co-transfected into 1.5 × 106 H1 hESCs using the Human Stem Cell Nucleofector Kit 2 (Lonza) and the Amaxa Nucleofector II (Lonza). 24 hr after plating into Matrigel-coated six-well plates, nucleofected cells were selected with puromycin (1 µg/mL mTeSR1 media) for 2–3 consecutive days. Individual colonies that emerged within 7 days after transfection were subsequently transferred manually into 96-well plates for expansion. Genomic DNA for PCR genotyping with GoTaq Green Mastermix (Promega) and Sanger sequencing was then extracted using QuickExtract DNA Extraction Solution (Lucigen).

To generate sORF frameshift mutations, sgRNA sequences targeting the N-terminal region of the predicted small peptides were inserted into pSpCas9(BB)−2A-GFP (Addgene plasmid #48138, RRID:Addgene_48138, gift from Feng Zhang) via its BpiI cloning sites. 3 µg of the resulting plasmids were then transfected into 500,000 H1 cells plated into Matrigel-coated six-wells the day prior, using XtremeGene 9 Transfection Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 24 hr post-transfection, 10,000 GFP+ cells were sorted on an Influx Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences) into Matrigel-coated six-wells containing 1 mL mTeSR1 media supplemented with 10 µM ROCK inhibitor and 1X penicillin/streptomycin. Seven days after sorting, emerging colonies were hand-picked and transferred into 96-well plates for genotyping. Frameshifts inside the targeted sORFs were confirmed by PCR-amplification of the sORF sequence with GoTaq Green Mastermix (Promega, Cat# M7123) and subsequent subcloning the PCR products into pCR2.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For each hESC clone, at least six pCR2.1 clones were Sanger sequenced. Oligonucleotide sequences for sgRNA cloning are provided in Figure 4—source data 2A.

PCR genotyping of CRISPR clones

Four days after transfer of single cell-derived clones into 96-wells, cell culture supernatants containing dead cells were collected from each well prior to the daily media change. Cell debris was then pelleted and used for gDNA extraction with 10–20 µl QuickExtract DNA Extraction Solution (Lucigen, Cat# QE09050) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 1 µl DNA was then PCR-amplified with GoTaq Green Mastermix (Promega, Cat# M7123) and locus-specific primers that anneal either within or outside of the excised genomic DNA. PCR products generated with ‘inside’ primers were visualized on a 2% agarose gel, PCR bands generated with primers flanking the deletion were gel-purified and submitted for Sanger sequencing (see Figure 4—source data 2B for genotyping and sequencing primers).

For genotyping of sORF frameshift clones, PCR amplicons designed to encompass the Cas9 cut site were amplified and Sanger sequenced (Figure 4—source data 2B). If out-of-frame indels were apparent in the sequencing chromatogram, the sequenced PCR product was ligated into pCR2.1-TOPO via TOPO-TA cloning. A minimum of six clones were Sanger sequenced in order to determine the genotype at both alleles with high confidence.

Generation of sORF translation reporter plasmids

The four lncRNAs tested were PCR-amplified with KOD Xtreme DNA Hotstart Polymerase (Millipore) from their 5’ end up until the last codon of the sORF to be tested, omitting its stop codon (primer sequences are listed in Figure 4—source data 2D). cDNA was used as PCR template for LINC00261 and LHFPL3-AS2; RP11-834C11.4, and MIR7-3HG were amplified from a gBlock synthetic gene fragment (Integrated DNA Technologies; see Figure 4—source data 2F). The GFP coding sequence (without start codon; amplified from pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-GFP.WPRE; RRID:Addgene_12252) was then fused in-frame to the sORF via overlap extension PCR. The resulting fusion product was cloned into pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-GFP.WPRE (Addgene plasmid #12252, gift from Didier Trono) via BshTI and SalI restriction sites included in the PCR primers. Due to the 3’-location of sORF7 within LINC00261, not the entire LINC00261 cDNA was amplified but only 65 bp preceding sORF7.

To create the RP11-834C11.4-sORF-1XFLAG reporter construct in an analogous way, a gBlock synthetic gene fragment encompassing the FLAG-tagged sORF served as PCR template (Figure 4—source data 2F). The resulting PCR product was cloned into pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-GFP.WPRE via BshTI and SalI restriction sites.

Generation of LINC00261 wild type and ΔATGsORF1-7 expression plasmids

The LINC00261 wild type cDNA was PCR-amplified from pENTR/D-TOPO-LINC00261 (gift from Leo Kurian) with KOD Xtreme DNA Hotstart Polymerase (Millipore, Cat# 71975). The resulting PCR product was inserted into pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-GFP.WPRE via its appended BshTI/SalI cloning sites. Full-length LINC00261 ΔATGsORF1-7 was assembled through overlap extension PCR from the following three fragments and subsequently cloned into pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-GFP.WPRE via appended BshTI/SalI cloning sites: (i) a 1,248 bp PCR product amplified from a synthetic gene construct (Genewiz; see Figure 4—source data 2F for sequence) in which the ATG start codons of sORFs 1–6 had been mutated (ATG → AAG/ATT/ AGG/AAG/ ATA/AGG), and (ii-iii) 3,111 bp/610 bp PCR fragments (amplified from the LINC00261 cDNA) in which the sORF7 start codon was mutated (ATG → AAG). The obtained plasmids were sequence-verified by Sanger sequencing.

Immunofluorescence staining

H1 hESC-derived cells grown as monolayer on Matrigel-coated coverslips were washed twice with PBS and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. Following three washes in PBS, samples on coverslips were permeabilized and blocked with Permeabilization/Blocking Buffer (0.15% (v/v) Triton X-100% and 1% normal donkey serum in PBS) for 1 hr at room temperature. Primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in Permeabilization/Blocking Buffer. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies, and then secondary antibodies for 30 min at room temperature. The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-OCT4 (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat# 2890, RRID:AB_2167725, 1:500), goat anti-SOX17 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat# AF1924, RRID:AB_355060, 1:250), goat anti-FOXA2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat# sc-6554, RRID:AB_2262810, 1:250), goat anti-GATA6 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat# sc-9055, RRID:AB_2108768, 1:50), guinea pig anti-insulin (Dako, Cat# A0564, RRID:AB_10013624). Secondary antibodies (1:1000) were Cy3- or Alexafluor488-conjugated antibodies raised in donkey against guinea pig, rabbit or goat (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Cat# 706-545-148, RRID:AB_2340472, Cat# 711-545-152, RRID:AB_2313584, Cat# 705-165-147, RRID:AB_2307351). Images were acquired on a Zeiss Axio-Observer-Z1 microscope with a Zeiss AxioCam digital camera, and figures prepared with Adobe Photoshop/Illustrator CS5.

Flow cytometry analysis

For intracellular flow cytometry, single cells were washed three times in FACS buffer (0.1% (w/v) BSA (Thermo Fisher Scientific in PBS) and then fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm Fixation/Permeabilization Solution (BD Biosciences) for 20 min at 4°C, followed by two washes in BD Perm/Wash Buffer. Cells were next incubated with either PE-conjugated anti-SOX17 antibody (BD Biosciences; Cat# 561591, RRID:AB_10717121), or PE-conjugated anti-INS antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat# 8508S, RRID:AB_11179076) in 50 µl BD Perm/Wash Buffer for 60 min at 4°C. Following three washes in BD Perm/Wash Buffer, cells were analyzed on a FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences) cytometer.

Insulin content measurements

To measure total insulin content of endocrine cell stage control and lncRNA KO cells, adherent cultures were enzymatically detached from a 24-well at day 16 of differentiation. Upon quenching with FACS buffer (0.1% (w/v) BSA (Thermo Fisher Scientific in PBS), the cells were pelleted and extracted over night at 4°C in 100 µl acid-ethanol (2% HCl in 80% ethanol). Insulin was measured by Insulin ELISA (Alpco, Cat# 80-INSHU-E10.1) and normalized to total protein, as quantified with a BCA protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 23227).

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from hESC-derived cells and HEK293T cells using either TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 15596018) or the RNAeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Cat# 15596018), respectively. Upon removal of genomic DNA (TURBO DNA-free Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# AM1907 or RNase-free DNase Set, Qiagen, Cat# 79254) cDNA was synthesized using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Cat# 1708890). PCR reactions were run in triplicate with 6.25–12.5 ng cDNA per reaction using the CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (BioRad). TATA-binding protein (TBP) was used as endogenous control to calculate relative gene expression using the ΔΔCt method. Primer sequences are provided in Figure 4—source data 2C.

Transient transfection of HEK293T cells with polyethylenimine (PEI)

Two hours prior to transfection, fresh pre-warmed DMEM medium (Corning, Cat# 45000–312) was added to each well. Transfection mix was prepared by combining PEI (Polysciences Cat# 23966–1) and plasmid DNA (4:1 ratio; 4 µg PEI per 1 µg DNA) in Opti-MEM Reduced Serum Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 31985062) followed by brief vortexing. After five minutes, the transfection complex was added dropwise to the cells.

Lentivirus preparation and ectopic LINC00261 expression

Lentiviral particles were prepared by co-transfecting HEK293T cells (using PEI) with the pCMVR8.74/pMD2.G helper plasmids (Addgene plasmids #22036/12259, RRID:Addgene_22036 and RRID:Addgene_12259, gift from Didier Trono) and with pRRLSIN.cPPT.PGK-GFP.WPRE transfer plasmid (RRID:Addgene_12252), in which the GFP ORF had been replaced with the 4.9 kb LINC00261 cDNA. Virus-containing supernatant was collected for two consecutive days and concentrated by ultracentrifugation for 2 hr at 19,400 rpm using an Optima L-80 XP Ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter).

To express LINC00261 (wild type) and LINC00261 (ΔATGsORF1-7) in HEK293T cells, the cells were plated in 6-well plates and transduced with lentivirus the following day. Two days post infection, the cells were passaged for RNA half-life measurements.

LINC00261 RNA half-life measurement

HEK293T cells transduced with either LINC00261 (wild type) or LINC00261 (ΔATGsORF1-7) lentivirus were seeded in six 24-wells. 48 hr after plating, cells from one well were collected for RNA isolation as the ‘0 hr’ time point. To the remaining five wells, 100 µl growth media supplemented with 10 µg/ml actinomycin D (Sigma-Aldrich Cat# A9415) were added to inhibit transcription. At 2, 4, 6, 8, and 9 hr following actinomycin D addition, samples were collected for RNA isolation. Total RNA was then reverse transcribed and analyzed by qPCR, where the abundance of each time point was calculated relative to the abundance at the 0 hr time point (ΔCt). The half-life was then determined by non-linear regression (One phase decay; GraphPad Prism).

Single molecule RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (smRNA FISH)

H1-derived PP2 stage cells (control and LINC00261 KO) were cultured on Matrigel-coated 12 mm diameter coverslips in a 24-well plate. Following 10 min fixation in 1 mL Fixation Buffer (3.7% (v/v) formaldehyde in PBS) at room temperature, the cells were washed twice in PBS and subsequently permeabilized in 70% (v/v) ethanol for one hour at 4°C. Following a five minute wash in Stellaris RNA FISH Wash Buffer A (LGC Biosearch Technologies, Cat# SMF-WA1-60; 1:5 diluted concentrate, with 10% (v/v) formamide added), the coverslips were incubated in a humidified chamber at 37°C for 14 hr with probes diluted in Stellaris RNA FISH Hybridisation Buffer (LGC Biosearch Technologies, Cat# SMF-HB1-10; with 10% (v/v) formamide added) to 125 nM. After a 30 min wash at 37°C in Wash Buffer A, the cells were counter-stained with Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 15 min and washed in RNA FISH Wash Buffer B (LGC Biosearch Technologies, Cat# SMF-WB1-20) for 5 min at room temperature. The coverslips were mounted in Vectashield Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories, Cat# H-1000) and imaged on a UltraView Vox Spinning Disk confocal microscope (PerkinElmer) using a 100X oil objective.

In vitro transcription/translation of lncRNAs

Synthetic gene constructs containing complete transcript isoforms (including the predicted 5’ and 3’ UTR) of four translated lncRNAs (RP11-834C11.4, LINC00261, MIR7-3HG, and LHFPL3-AS2) were produced by Genewiz (constructs available upon request). Microproteins were translated in vitro from 0.5 µg linearized plasmid DNA using the TnT Coupled Wheat Germ Extract system (Promega; Cat# L4140) in the presence of 10 mCi/mL [35S]-methionine (Hartmann Analytic) according to manufacturer’s instructions. 5 µL lysate was denatured for 2 min at 85°C in 9.6 µL Novex Tricine SDS Sample Buffer (2X) (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Cat# LC1676) and 1.4 µL DTT (500 mM). Proteins were separated on 16% Tricine gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Cat# EC66955BOX) for 1 hr at 50 V followed by 3.5 hr at 100 V and blotted on PVDF-membranes (Immobilon-PSQ Membrane, Merck Millipore; Cat# ISEQ00010). Incorporation of [35S]-methionine into newly synthesized proteins enabled the detection of translation products by phosphor imaging (exposure time of 1 day).

In vivo translation assays