Abstract

Human groups have long faced ecological threats such as resource stress and warfare, and must also overcome strains on coordination and cooperation that are imposed by growing social complexity. Tightness–looseness (TL) theory suggests that societies react to these challenges by becoming culturally tighter, with stronger norms and harsher punishment of deviant behaviour. TL theory further predicts that tightening is associated with downstream effects on social, political and religious institutions. Here, we comprehensively test TL theory in a sample of non-industrial societies. Since previous studies of TL theory have sampled contemporary countries and American states, our analysis allows us to examine whether the theory generalizes to societies in the ethnographic record and also to explore new correlates of tightness that vary more in non-industrial societies. We find that tightness covaries across domains of social norms, such as socialization, law and gender. We also show that tightness correlates with several theorized antecedents (ecological threat, complexity, residential homogeneity) and several theorized consequences (intergroup contact, political authoritarianism, moralizing religious beliefs). We integrate these findings into a holistic model of tightness in non-industrial societies and provide metrics that can be used by future studies on cultural tightness in the ethnographic record.

Keywords: tightness–looseness, cultural evolution, non-industrial societies

1. Introduction

Over the last 12 000 years, many human groups have transformed from small autonomous communities to large, complex societies with social stratification, political hierarchy, and market economies [1]. This is a remarkable feat, because large societies must maintain high levels of cooperation and organization in order to achieve stability, and threats such as disease, famine, and warfare can destabilize groups of any size. A major goal of the social sciences is to understand how groups responded and overcame these survival pressures, with implications for the evolution of human diversity.

An emerging theory of culture suggests that variation in cultural tightness—the strictness of cultural norms and harshness of punishments for norm violations—may be a key factor in the cultural evolution of human groups [2]. Tightness–looseness (TL) theory suggests that strong norms and harsh punishments are effective for keeping groups organized and cohesive, especially in the face of ecological threats such as famine and warfare or growing social complexity [2–4]. TL theory also makes downstream predictions for how the strength of norms shapes political hierarchy, intergroup contact, and religion, among other factors [2–8].

This paper tests TL theory in a global sample of non-industrialized societies using data from the ethnographic record. We view this analysis as important for several key reasons. Past tests of TL theory have used samples of industrialized countries [3] and American states [4], but have not yet been applied to smaller scale societies from earlier time periods in the ethnographic record. If TL is a general theory of culture, its central predictions should generalize to groups of different scales and time periods. Showing that predictions from TL theory generalize to non-industrial samples from the seventeenth to twentieth centuries helps demonstrate that these are broad patterns of cultural evolution. To our knowledge, this is one of the first attempts to apply theories of cultural psychology developed with modern nations to societies from the ethnographic record.

Testing TL theory in non-industrialized societies not only demonstrates the generalizability of the theory, but also makes it possible to extend the theory to test new variables that are theoretically important but are absent or do not vary sufficiently in industrialized societies. Moreover, testing TL theory in non-industrial societies also contributes to basic anthropological and psychological research on the foundations of human diversity, and the coevolution of ecological, social, political, and religious facets of society. Scholars have long studied the nature of governance, religion, social complexity, and ecology in small-scale societies, but these variables are often examined in isolation rather than together. Our paper situates these different variables in a broader theoretical framework, showing how some variables may be directly and indirectly connected in non-industrial societies through their relationship with cultural tightness.

The remainder of this introduction lays out three theorized antecedents and three theorized consequences of TL theory in non-industrialized societies, with careful attention to relationships that have been tested before, and those that have been theorized but never tested in past research. We then discuss the possible structure of cultural tightness across different domains of cultural norms, such as socialization, gender, and sexuality and test our theory across 86 non-industrial societies. Our results replicate and extend previous research and provide new metrics for the study of social norms in pre-industrial societies.

(a). Tightness–Looseness theory

Scholars from the ancient Greek historian Herodotus to the twentieth century anthropologist Pertti Pelto have recognized that human groups vary in their cultural tightness [9,10], but TL theory goes beyond these descriptive accounts to make predictions about why societies vary in tightness and how tightness shapes other facets of society.

(b). Theorized antecedents of tightness

Past research has shown that ecological threat—broadly defined as inclusive of social and environmental threats [2–5]—is a major antecedent of cultural tightness in contemporary countries and states [3,4]. Two of the tightest countries are India—which spends a large share of its budget fighting natural disasters [11]—and Japan—which has faced chronic hazards and warfare throughout its history. Tight American states such as Texas, Alabama and Mississippi also have histories of flooding, storms and resource scarcity [4]. Cultural evolutionary models suggest that threat increases tightness because threat depletes resources and increases the likelihood of individual-level defection [12]. Strong norms and the expectation of harsh punishment are therefore crucial in the face of threat to avoid large-scale defection and preserve order [2–4,12]. These models suggest that threat should predict tightness in non-industrial societies, but this association has never been tested.

Social complexity may be another key predictor of tightness. Pelto [10] noted that larger and more complex societies may be tighter because these societies feature legal, religious and economic institutions that require large-scale coordination and organization. For instance, complex societies are more likely to have legal codes, taxation systems and standing armies [13], all of which require strong norms and punishments to maintain. Other research found that more complex societies practicing intensive agriculture, such as the Azande of North Central Africa, had tighter socialization styles than smaller and less complex hunter–gatherer groups [14].

Although social complexity has long been a theorized predictor of tightness, the relationship between complexity and tightness has, to our knowledge, not been tested. This may be because countries and states do not vary sufficiently in terms of their complexity, all featuring market economies, international trade networks and established political systems. Yet non-industrialized societies vary more in complexity. For example, only 13% of non-industrialized societies have communities larger than 1000 people [15]. Sampling from the ethnographic record therefore offers the first opportunity to test the complexity-tightness link.

Whereas ecological threat and complexity may facilitate tightness, social heterogeneity may be a key inhibitor of cultural tightness. In both nationwide and statewide surveys, cultures with ethnically and religiously diverse histories such as Brazil and California have been the loosest, whereas historically homogenous groups such as Austria and Japan have been tighter [3,4]. This may be because heterogeneity prevents the consolidation of strong group norms, as many different systems of norms are competing within the same society.1

It is more difficult to measure social heterogeneity in non-industrial societies because these societies are more likely than modern countries to be religiously and ethnically uniform. However, different residence patterns may influence kinship heterogeneity in small-scale societies. Anthropologists [17] have noted that there are different community organization patterns in matrilocal (husbands settle near their wives' parents) versus patrilocal societies (wives settle near their husband's parents). Patrilocal societies tend to have wives coming from other communities (community exogamy); matrilocal societies tend to lack exogamy [18]. This means that patrilocal communities are often dominated by one group of related males, making it easier to enforce a single set of norms. By contrast, matrilocal communities incorporate different sets of kin groups and are more heterogeneous compared with patrilocal communities. Bilocal societies have a mixture of patrilocal and matrilocal residence. Matrilocal and bilocal societies therefore have higher kinship heterogeneity and may encourage looseness more than patrilocal societies [17–19]. Indeed, these trends may be robust even when controlling for social organization factors, such as polygyny, and matrilineality/patrilineality (the rule of descent that affiliates individuals with kin related to them through women/men only).

(c). Theorized consequences of tightness

Cultural tightness may also have far-reaching consequences for other social institutions. Two major consequences involve the effects of tightness on political authoritarianism and intergroup contact. Recent work has found that tight countries such as Turkey and Malaysia tend to have more authoritarian governments than loose countries such as New Zealand and Greece [3,5]. Furthermore, individual people who support strong norms often endorse authoritarian leaders because they see these leaders as better suited to maintain law and order and uphold existing norms [5]. In these studies, tightness also predicted nation-level and individual-level prejudice towards foreigners, and experimentally increasing perceived threat led people to value tighter in-group norms and traditions while increasing people's distrust in and avoidance of foreigners [5]. This dynamic has not yet been tested in non-industrial societies, but past research suggests that tightness might predict authoritarian leadership and negatively predict the frequency of intergroup contact in these groups.

Tightness may also lead to more moralizing and authoritarian conceptions of supernatural agents for many of the same reasons it leads to more support for authoritarian leaders. Recent research suggests that people in societies with strong cultural norms view punitive traits of gods as more important because these traits suggest that rule-breakers will be supernaturally punished for their behaviour, even if they cannot be punished by secular institutions [8]. Consistent with this dynamic, historical fluctuations in tightness predict citations of Bible passages in which the Christian God punishes wrongdoers, and tightness can explain why moralizing god beliefs are most widespread during times of warfare [8]. This evidence suggests that tight non-industrial societies may therefore have the strongest beliefs in moralizing high gods.

(d). Theorized structure of tightness

While most research on TL theory has focused on the antecedents and consequences of cultural tightness, there are also interesting questions about the structure of tightness. Specifically, it is not clear whether tightness in one domain of life (e.g. gender norms) should translate to tightness in other domains of life (e.g. socialization). Preliminary evidence supports the covariance of tightness across domains [4], and this may occur because it is easier to strengthen norms than to loosen them, leading tight norms in one domain to spill over into tightness in other domains, rather than vice versa. Indeed, a new theory of ‘concept creep' uses this as the reason that, once topics gain a moral taboo, it is very difficult to break this taboo [20]. Tightness may also covary across domains because community executives influence the strength of norms across all domains of life. When tightness is enforced through top-down regulation, an executive body may often restrict norms across a variety of domains. For example, the Catholic church calls for restrictions on marriage, socialization, religious practices and etiquette. A correlation between tightness across domains may stem from a combination of these top-down and bottom-up processes.

However, it is also plausible that tightness is relatively independent across domains of life because domains tighten in response to domain-specific ecological threats. For example, the outbreak of a sexually transmitted infection may lead to tighter norms around sexuality and marriage, while having little effect on socialization norms. Many non-industrial societies have been documented extensively, and there is a wealth of information available about the norms related to gender, marriage, socialization, mourning, ethics and sexuality in these societies [21]. Measuring tightness across domains of norms makes it feasible to test whether cultural tightness is best captured by a single dimension, or whether it varies across domains.

(e). The current research

Here, we test TL theory among ethnographically documented societies in the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample (SCCS), a sample of non-industrial societies which were pre-selected to have low levels of borrowing and distant phylogenetic heritage [15]. In this sample, we test whether cultural tightness has associations with its theorized antecedents and consequences, and whether it has a unidimensional or multidimensional structure. We then integrate these paths into a structural equation model (SEM) of cultural tightness that approximates the theoretical model we have laid out in this paper (figure 4). This model simultaneously estimates the fit of our theorized model, while also displaying the strength of individual paths between variables.

Figure 4.

A structural equation model of cultural tightness in non-traditional societies. Open arrows represent regression paths. Closed arrows represent indicators of the cultural tightness latent variable. Unshaded boxes represent theorized predictors, outcomes and indicators of tightness and shaded boxes represent control variables. All coefficients have been standardized, which means that they can be interpreted as effect sizes similar to r values in a correlation. Coefficients for control variables have been omitted here for clarity, but all coefficients are presented in the electronic supplementary material. Single-asterisk relationships represent statistical significance at p < 0.05. Double-asterisk relationships represent statistical significance at p < 0.005. †Geography and subsistence are also entered as control variables for the association between tightness and its theorized consequences, in addition to predicting tightness itself.

These are correlational analyses, which do not establish whether threats, complexity, and social structure cause cultural tightness or whether cultural tightness causes authoritarian leadership, less intergroup contact or belief in moralizing high gods. However, our SEM situates our analyses within a broader model that enables us to provide an overall test of the patterns of theorized relations. Our study also provides new metrics on TL (see the electronic supplementary material, table S1) that can be used by others to test broad questions about culture that we do not address here.

2. Method

In addition to this method section, readers may also refer to our glossary of terms in the electronic supplementary material, S11, for further clarifications about semantics and measurement.

(a). Sample

We drew our sample of 86 groups from the SCCS, which is a sample of 186 anthropologically described societies pinpointed in a particular time and space (e.g. the Nama people from South Africa were documented around a focal date of 1860). We chose the SCCS to minimize linguistic and geographical relatedness, so only one society was chosen from a given cultural area. However, the SCCS is a tremendously diverse sample in many other ways beyond geographical distribution, with societies that practice diverse subsistence strategies and live in a diverse range of environments. For example, the Copper Inuit live in the Nunavut Kitikmeot region of Canada and have historically procured food through fishing (including sea mammal hunting), whereas the Mbuti people are an indigenous group in Central Africa who have long practiced hunting and gathering as their primary subsistence strategy.

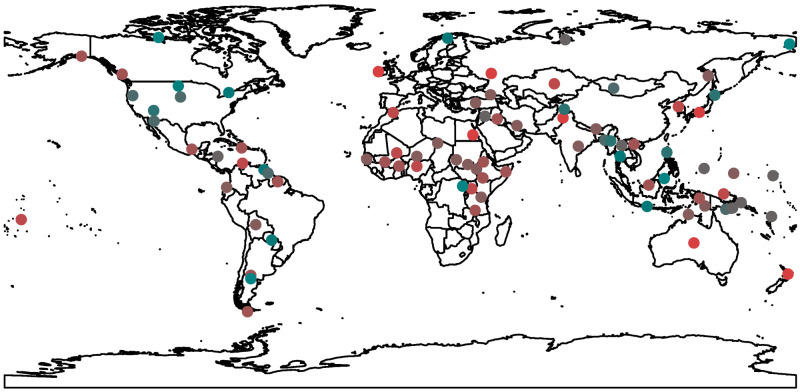

We developed our TL codes using ethnographic material available in electronic Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures wherever possible. For those SCCS societies not yet in eHRAF, we obtained the major ethnographic sources specified for the focal time and place from libraries. Our final sample included 86 societies that had sufficient ethnographic information to code, and included groups across a wide variety of subsistence styles (see the electronic supplementary material for more information on how we selected these 86 groups). This sample's diversity alleviated our concerns about sampling bias, which could arise when subsampling from the SCCS. Figure 1 displays the geographical distribution of our sample and electronic supplementary material, table S1 displays other sample characteristics.

Figure 1.

The worldwide distribution of societies in our sample. Redder (versus bluer) points represent societies with a higher tightness score. Tightness here is averaged across domains. (Online version in colour.)

(b). Tightness–looseness codes

Measuring cultural variance in the ethnographic record requires different methodology than studies of current-day populations. Cross-cultural researchers use ethnographic descriptions to develop quantitative ‘codes' to enable comparison of cultures [22]. Pelto [10] developed an early attempt at coding tightness in the ethnographic record by examining the presence or absence of 12 variables (e.g. theocracy, corporate ownership of stored food) in 21 societies. Yet Pelto only coded a small sample and had no measure of coding reliability. Building on these efforts, we designed a theory-driven coding scheme that directly measured tightness.

According to past literature on TL theory, cultural tightness is defined and measured by the strength of norms and the punishment of normative violations. We used previous surveys of tightness to develop new ethnographic codes measuring strength of norms via (i) the degree that cultural norms constrained behaviour and (ii) the extent that people followed cultural norms. We measured the punishment of violations with codes assessing (iii) how often people expected punishment for norm violations and (iv) how harsh punishment was expected to be for norm violations. Each code included a 1–4 scale. We also included an ‘overall' code that integrated the four specific scores into a general 1–4 number where higher values indicated greater tightness.

We applied these codes to six domains of cultural norms that were universally important for human groups. We also made sure that these domains had subject categories in eHRAF World Cultures and sufficient material for coding in the ethnographic record. Based on these criteria, we included ‘law and ethics', ‘gender', ‘socialization', ‘marriage', ‘sexuality', and ‘funerals and mourning'. We separated the ethnographic material corresponding to each domain on the basis of the HRAF's outline of cultural materials (OCM) subject categories. For example, paragraphs tagged with ‘law' categories (OCM 670–677) in HRAF would be coded under the broader ‘law and ethics' domain, whereas paragraphs tagged with ‘socialization' (OCM 860–869) would be coded under the ‘socialization' domain. Overall, this procedure produced 2580 total cultural tightness data-points. The full set of OCM codes is available in our coding manual, which is hosted on https://osf.io/93keq/, which also hosts our data files and analysis script.

Two full-time research assistants implemented this coding scheme. Before formal coding began, we established reliability between these research assistants by selecting random subsets of cases and computing the association between each research assistant's codes using Krippendorf's alpha. Once we had established appropriate reliability between the coders (α = 0.75; intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) = 0.66), each coder was then randomly assigned half of our sample to code individually. We established acceptable reliability after coding 40 societies. The worldwide distribution of tightness, according to our final codes, is displayed in figure 1.

(c). Measures: theorized antecedents of tightness

(i). Ecological threats

We selected pathogen prevalence, warfare, food scarcity, natural hazards, and population pressure as ecological threats because they have been tied to cultural tightness in past studies, and because they create pressure for communities to cooperate and coordinate owing to their impact on mortality and food availability.

(ii) Pathogen prevalence

We measured pathogen prevalence using data from Low [23], in which seven pathogens were coded on a 1–3 scale where 1 = absent or not recorded, 2 = present (no indication of severity), 3 = present and serious, widespread or endemic. We recoded this variable so that 0 = pathogens absent or not reported and 1 = pathogens reported. We then summed across the seven pathogens so that a score of 7 would represent that all pathogens which Low [23] measured were reported. We also developed a binary code to code for the presence of at least one pathogen. Because our results were identical across these variables, we focus on the summed score here and report the dummy-coded score in the electronic supplementary material.

(iii) Warfare

We measured warfare using variables from Ross [24] measuring the frequency of warfare within and between polities (usually factions within a society), which we reverse scored such for 1 (rare or never) to 4 (frequent, occurring at least yearly) scale. Our electronic supplementary material further explore two additional measures of warfare by Ember & Ember [25] that uses the society, rather than the polity, as the unit of analysis.

(iv). Food scarcity

We created a composite food scarcity index by averaging together codes from two prominent papers on two types of scarcity [25,26]: from Dirks [26], we took ‘occurrence of famine' and ‘severity of famine' variables, which were coded from a 1 (very low/not at all severe) to 5 (very high/severe). From Ember & Ember [25], we used variables measuring ‘famine', which was coded on a 1 (low threat) to 4 (2+ famines in a −15/+10 years around the time of description) scale, and ‘chronic scarcity,' coded from a 1 (low or rare) to 4 (most members of the population do not have enough to eat). These four items showed moderate reliability (α = 0.75), suggesting that they each tapped the level of scarcity facing societies.

(v). Natural hazards

We measured natural hazards with data from Ember & Ember [25], who coded potential food-destroying hazards (e.g. droughts, pest infections, and food-destroying floods or storms) with numbers ranging from 1 (low threat) to 4 (two or more in a 15 to 10 years around the time of description). Ember & Ember [25] did not count hazards that usually do not affect food supplies, such as earthquakes.

(vi). Population pressure

We measured population pressure using Lang's [27] binary code indicating whether there was land shortage owing to overpopulation.2

(vii). Complexity

Complexity across societies in the ethnographic record is often measured using a sum of 10 different indicators from Murdock & Provost [28]. These include writing and records, money, fixity of residence, agriculture, urbanization, technological specialization, land transport, population density, political integration, and social stratification. The summed index is used in the present paper because the items were highly intercorrelated (α = 0.90), and previous work has suggested that these measures tap a single underlying construct [13,28,29]. We also summarize analyses of individual complexity indicators in our electronic supplementary material, analyses.

(viii). Kinship heterogeneity

Data on marital residence came from the Ethnographic Atlas [30] and was used to create a variable such that 1 = society has matrilocal or bilocal residence structure and 0 = society has neither matrilocal or bilocal residence structure. Our electronic supplementary material contains more detail.

(d). Measures: theorized consequences of tightness

(i). Authoritarian leadership

We measured authoritarian leadership by reverse-coding Ross's [24] code ‘Checks on Leader's Power' such that 1 = no leaders act independently lest their community backing lost, 2 = leaders carefully secure substantial support before taking action, 3 = checks exist which seem to make leaders sensitive to populace, 4 = few, or those that exist not invoked very often.

(ii). Intergroup contact

We measured intergroup contact by reverse-coding Ross's [24] measure of intergroup contact, with a revised scale of 1 (rare or never) to 3 (frequent).

(iii). Moralizing religious belief

We measured moralizing religious belief by dummy-coding the moralizing high god variable from the Ethnographic Atlas [30]. As in past studies, societies with high gods that were specifically supportive of human morality received a ‘1’ in this dummy-code and all other societies received a ‘0' [31,32].

(e). Analytic strategy

Our main text presents three sets of analyses. Our first set of analyses tested whether tightness was best characterized by a unidimensional structure across domains, or whether it instead formed a higher dimensional structure. We assess this through a combination of maximum-likelihood exploratory factor analysis (EFA)—which uses eigenvalues to make recommendations about the factor structure of a measure—principal components analysis (PCA)—a similar test which indicates the explanatory power of underlying principal components—and by calculating the ICC. The ICC indicates the average correlation across domains, the percentage of variance explained by cross-domain variation within societies versus cross-society variation.

We next used multi-level regression to estimate the association between cultural tightness and its theorized antecedents and consequences. These models nested domains of life (n = 453) within societies (n = 86), with intercepts randomly varying across societies. We also ran three-level multi-level models that further nested societies within language families (n = 53), with intercepts varying across societies and language families. These tests are similar to correlations involving a tightness score that is aggregated across domains, but feature more power and also account for the ancestral relationships between societies.

Finally, we integrated our correlations into an SEM. This model tested whether the significant links between tightness and its antecedents and consequences were robust to each other. Our model also controlled for geography (via latitudes and longitudes), subsistence style (pastoralist, horticulturalist, intensive agriculturalist, other) and social organization styles (via patrilineality, matrilineality and polygyny) to ensure our theorized relations were found above and beyond these factors. Global fit statistics in an SEM allowed us to evaluate whether our analysis reproduced a realistic model of cultural tightness, or whether it omitted or misplaced key variables. Our electronic supplementary material also includes analyses of domains of tightness, individual indicators of social complexity, further analyses of ecological threats, and correlations between all variables in our analyses.

3. Results

(a). The structure of cultural tightness

Funerals and mourning was the tightest domain (mean (M) = 3.37), followed by law and ethics (M = 2.99), gender (M = 2.85), sexuality (M = 2.81), marriage (M = 2.77) and socialization (M = 2.65). An EFA of the six domains supported a unidimensional structure cultural tightness across domains. The first factor had an eigenvalue of 3.56, whereas the next highest eigenvalue was 0.74 (figure 2). Parallel analysis, optimal coordinates analysis, and accelerated factor analysis also suggested a one-factor solution.

Figure 2.

(a) The results of a maximum-likelihood exploratory factor analysis (EFA). (b) Variance explained from principal components of a PCA analysis. Both analyses suggested that cultural tightness was best explained through a unidimensional structure across domains. (Online version in colour.)

A PCA also found a unidimensional solution. The first PC explained 59% of variation across domains, whereas the second PC only explained 12% (figure 2). Finally, the ICC of cultural tightness across domains was 0.47, indicating that 47% of variation in tightness was explained by differences between societies (versus differences across domains within a society). All domains correlated significantly with each other, and these correlations are displayed in table 1. Given these results, our primary analyses measured tightness as a global factor. Nevertheless, our electronic supplementary material analyse domains of tightness separately.

Table 1.

Cultural tightness across different domains of cultural norms. (*significant at the 0.05 level; **significant at the 0.001 level.)

| law | socialization | gender | marriage | sexuality | funerals/mourning | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| law | 1 | |||||

| socialization | 0.71** | 1 | ||||

| gender | 0.63** | 0.48** | 1 | |||

| marriage | 0.63** | 0.56** | 0.50** | 1 | ||

| sexuality | 0.56** | 0.49** | 0.46** | 0.43** | 1 | |

| funerals/mourning | 0.50** | 0.51** | 0.32* | 0.46** | 0.33* | 1 |

(b). Correlates of cultural tightness

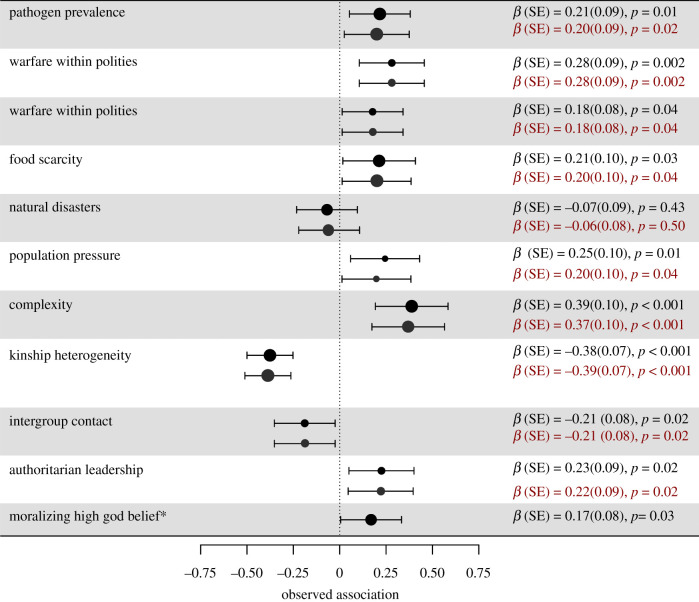

We next tested for whether cultural tightness was associated with our theorized correlates using a series of multi-level models. Figure 3 visually summarizes each association from these models. All variables have been standardized, meaning that the regression coefficients from these analyses represent effect sizes similar to correlation coefficients.

Figure 3.

Associations between cultural tightness and its theorized antecedents (top 10 variables) and consequences (bottom three variables). Node size indicates the number of societies in the analysis. Black nodes represent multi-level models nested in society; red nodes represent multi-level models nested within society and language family. Effect sizes and p-values are displayed on the right, and additional statistics for each model are available in the electronic supplementary material. Moralizing high god belief has an asterisk because the three-level model controlling for language family did not converge, and we did not interpret this model. (Online version in colour.)

Many of these regressions supported TL theory's predictions. Cultural tightness was positively associated with several forms of threat (pathogen prevalence, warfare between polities, warfare within polities, food scarcity, and population pressure) and social complexity, and was negatively associated with kinship heterogeneity. Cultural tightness was also significantly associated with the three theorized consequences that we tested. Cultural tightness predicted fewer checks on leader's power (an indicator of authoritarian leadership), less intergroup contact, and greater belief in moralizing high gods.

We note not all theorized paths reached significance. While tightness was associated with food scarcity, it was not associated with natural hazards. This may be related to the measurement of this variable within the ethnographic record. Past research on current-day countries has measured natural hazards via their economic and mortality toll, but our ethnographic measure assessed only the occurrence of food-destroying natural hazards. Therefore, these hazards may not have been sufficiently threatening to elicit greater tightness. Future research could address this issue by exploring how non-industrial societies react to different forms of natural hazards.

(c). An integrated model of cultural tightness

We next used an SEM to test whether our significant regression results were independent from one another, robust to other control variables, and whether they were best organized based on TL theory's model of antecedents and consequences. We estimated this SEM at the society level and constructed a latent tightness factor that took loadings from each domain. This analysis also provided global fit statistics indicating whether we organized our model appropriately. A low global fit might indicate that our single-factor measure of tightness was inappropriate, or that antecedents would be better situated as consequences or vice versa. Prior to this analysis, we explored a lower dimensional organization of threat. Past research has summed ecological threats into a single index [3–5] but a maximum-likelihood EFA showed that threats formed a robust two-factor structure, with one factor (eigenvalue = 2.05, variance explained = 22%) containing food scarcity (0.96), natural hazards (0.52) and population pressure (0.35), and another factor (eigenvalue = 1.45, variance explained = 21%) containing external warfare (0.56), internal warfare (0.80) and pathogens (0.41). Whereas the first factor contained threats explicitly marking resource shortage, the second factor contained a broader set of threats related to survival pressure. Figure 4 illustrates our SEM.

The model converged normally after 122 iterations. Global fit statistics showed a chi-square statistic that was significant but less than double the degrees of freedom, p = 0.03, a root mean squared error of approximation value of 0.06, and a confirmatory fit index of 0.91, indicating appropriate model fit. Our electronic supplementary material shows that several changes to the model (e.g. adding paths to model the residual relationship between antecedents, adding paths to model the residual relationship between consequences, switching the antecedents and consequences) resulted in worse model fit, supporting our model's structure. Fixed effects in this model showed that many significant paths from our individual regressions remained significant. Interestingly, threats involving warfare and pathogens more strongly predicted tightness than threats involving resource stress (e.g. scarcity, food-destroying natural hazards). Our discussion section explores some potential reasons for the null relationship between natural hazards and tightness in this analysis.

4. Discussion

Human communities have grown and diversified to an extraordinary extent throughout our species' history, but this process has seldom been easy. Pathogens, scarcity, warfare, and other forms of ecological threat pose acute threats to the survival of human groups, and larger, more complex societies must maintain coordination and cooperation across groups of individuals who are not bound by reputation or kin group ties [2]. TL theory suggests that strict norms and harsh punishment of normative deviance is instrumental in overcoming each of these challenges, and that the tightest cultures should therefore be those with the most social complexity and historical levels of threat [2–4].

Previous tests of TL theory's predictions were conducted using current-day countries and American states that are each industrialized and globalized [3,4]. Here, we examined these predictions in a more diverse and historically representative sample of non-industrial societies from the ethnographic record. Replicating and extending TL theory in non-industrialized societies enables us to test broad pan-cultural and historical patterns of human variation that transcend space and time and that are critical to understanding processes of cultural evolution.

Our investigation reproduced previous associations between cultural tightness and ecological threat, authoritarian leadership, and less intergroup contact [3–8]. We also uncovered new links between cultural tightness, cultural complexity and kinship heterogeneity via residence structure. Social complexity predicted greater tightness, whereas kinship heterogeneity predicted greater looseness. Finally, we showed that cultural tightness covaries highly across domains, consistent with past research that has found cultural tightness is a unidimensional construct [4].

Not all hypothesized effects reproduced the findings of past research, which shows differences between non-industrial and industrialized samples. For example, tightness did not correlate with the frequency of natural hazards. This may be because in some past studies, natural hazards have been measured through their toll, in terms of property damage or lives lost [3]. The ethnographic measure, by contrast, coded for frequency of food-destroying natural hazards, which may have scored highly for cultures that frequently experienced such hazards but were well-prepared and relatively unaffected by disaster. The ethnographic measure also did not include natural hazards such as earthquakes that do not destroy food. The fact that food scarcity was a significant predictor of tightness, but hazards were not, suggests that the effect of ecological threats has to be psychologically salient to have an effect on TL.

We also note that our correlational analysis cannot claim that complexity, ecological threat, or residence heterogeneity causes cultural tightness. However, testing our associations across a diverse set of cultures and controlling for shared language family membership allows us to rule out the possibility that our results were confounded by interdependence of observations and offers more confidence as to the validity of our findings. Furthermore, our SEM suggested that our organization of antecedents and consequences fit the data well, did not omit empirically significant paths, and transcended other possible confounds such as geography or subsistence style. Further research could use time-series methods to test whether longitudinal changes in cultural tightness foreshadow changes in moralizing religion or political authoritarianism. Other research could build on recent experimental work showing that temporarily priming ecological threats increases people's preference for stricter norms and more punitive gods [5–8].

We also encourage future studies to continue exploring cultural tightness in the ethnographic record, and we have shared our codes, data and analysis scripts on https://osf.io/93keq/ to facilitate this process. For example, it would be interesting to further examine in the ethnographic record the connection between TL and other indicators of societal order such as frequent communal ritual, ritualistic synchrony, standardized adornment and repression of emotional expression. Likewise, further analyses may wish to test how cultural tightness is related to other cultural differences in non-industrial societies. Previous research [3] has shown that collectivism, power distance and conformity values [33,34] are moderately correlated with tightness in industrialized societies, yet, it is unclear whether this is the case in non-industrial societies [35]. Finally, a fruitful avenue for future research could be to test these hypotheses in current-day small-scale societies, rather than societies from the ethnographic record. Mapping cultural variation in small-scale societies offers a useful way of reproducing results derived from current-day nations and may help us identify the roots of many current-day cultural differences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Christina Carolus and Tahlisa Brougham for research assistance on this project. The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of these funding agencies.

Endnotes

It is also plausible that extremely heterogenous groups become tighter because extreme diversity could lead to potential conflict and coordination pressures [16].

Past research has correlated population density with cultural tightness across nations and American states, assuming that population density poses the threat of too many people occupying the same space [3,4]. However, in smaller scale societies, population density is probably not a good indicator of pressure on resources unless the food-getting technology is relatively uniform [25]; this is because smaller scale societies have a very broad range of subsistence types ranging from hunting and gathering to intensive agriculture. Population ‘pressure’—land shortage owing to overpopulation—is a better indicator of overpopulation than population density.

Data accessibility

All data and code from this study can be found at https://osf.io/93keq/.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Funding

This research was sponsored by a National Science Foundation grant (grant no 1416651) to C.R.E. and M.G. and awards from the National Science Foundation and the Royster Society of Fellows to J.C.J.

References

- 1.Waters CN, et al. 2016. The Anthropocene is functionally and stratigraphically distinct from the Holocene. Science 351, 2622 ( 10.1126/science.aad2622) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gelfand MJ, Harrington JR, Jackson JC. 2017. The strength of social norms across human groups. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 12, 800–809. ( 10.1177/1745691617708631) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gelfand MJ, et al. 2011. Differences between tight and loose cultures: a 33-nation study. Science 332, 1100–1104. ( 10.1126/science.1197754) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrington JR, Gelfand MJ. 2014. Tightness–looseness across the 50 united states. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 7990–7995. ( 10.1073/pnas.1317937111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson JC, et al. 2019. Ecological and cultural factors underlying the global distribution of prejudice. PLoS ONE 14, e0221953 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0221953) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aktas M, Gelfand MJ, Hanges PJ. 2016. Cultural tightness–looseness and perceptions of effective leadership. J. Cross-Cultural Psychol. 47, 294–309. ( 10.1177/0022022115606802) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson JC, Gelfand M, De S, Fox A. 2019. The loosening of American culture over 200 years is associated with a creativity–order trade-off. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3, 244 ( 10.1038/s41562-018-0516-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caluori NC, Jackson JC, Gray K, Gelfand MJ. 2020. Conflict changes how people view God. Psychol. Sci. 31, 280–292. ( 10.1177/0956797619895286) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herodotus, Waterfield R, Dewald C. 2008. The histories. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pelto PJ. 1968. The differences between ‘tight’ and ‘loose’ societies. Trans-action 5, 37–40. ( 10.1007/BF03180447) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta AK, Tyagi P, Sehgal VK. 2011. Drought disaster challenges and mitigation in India: strategic appraisal. Curr. Sci. 100, 1795–1806. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roos P, Gelfand M, Nau D, Lun J. 2015. Societal threat and cultural variation in the strength of social norms: an evolutionary basis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 129, 14–23. ( 10.1016/j.obhdp.2015.01.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turchin P, Currie TE, Whitehouse H, François P, Feeney K, Mullins D, Mendel-Gleason G. 2018. Quantitative historical analysis uncovers a single dimension of complexity that structures global variation in human social organization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E144–E151. ( 10.1073/pnas.1708800115) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barry H III, Child IL, Bacon MK. 1959. Relation of child training to subsistence economy. Am. Anthropol. 61, 51–63. ( 10.1525/aa.1959.61.1.02a00080) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White DR. 1989. Focused ethnographic bibliography: standard cross-cultural sample. Behav. Sci. Res. 23, 1–145. ( 10.1177/106939718902300102) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gefland MG, Harrington J, Fernandez J. 2017. Cultural tightness-looseness: ecological affordances and implications for personality. In The Praeger handbook of personality across cultures (ed. Church AT.), pp. 206–236. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider DM, Gough K (eds) 1961. Matrilineal kinship. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ember M, Ember CR. 1971. The conditions favoring matrilocal versus patrilocal residence. Am. Anthropol. 73, 571–594. ( 10.1525/aa.1971.73.3.02a00040) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulz JF, Bahrami-Rad D, Beauchamp JP, Henrich J. 2019. The church, intensive kinship, and global psychological variation. Science 366, eaau5141 ( 10.1126/science.aau5141) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haslam N. 2016. Concept creep: psychology's expanding concepts of harm and pathology. Psychol. Inq. 27, 1–17. ( 10.1080/1047840X.2016.1082418) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ember M. 1997. Evolution of the human relations area files. Cross-Cultural Res. 31, 3–15. ( 10.1177/106939719703100101) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ember CR, Ember M. 2009. Cross-cultural research methods. Lanham, MD: Rowman AltaMira. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Low BS. 1988. Pathogen stress and polygyny in humans. In Human reproductive behavior: a Darwinian perspective (eds Betzig L, Borgerhoff Mulder M, Turke P), pp. 115–127. Cambridge, UK: CUP Archive. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ross MH. 1983. Political decision making and conflict: additional cross-cultural codes and scales. Ethnology 22, 169–192. ( 10.2307/3773578) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ember CR, Ember M. 1992. Warfare, aggression, and resource problems: cross-cultural codes. Behav. Sci. Res. 26, 169–226. ( 10.1177/106939719202600108) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dirks R. 1993. Starvation and famine: cross-cultural codes and some hypothesis tests. Cross-Cultural Res. 27, 28–69. ( 10.1177/106939719302700103) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lang H. 1998. CONAN: an electronic code-text data-base for cross-cultural studies. World Cultures 9, 13–56. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murdock GP, Provost C. 1973. Measurement of cultural complexity. Ethnology 12, 379–392. ( 10.2307/3773367) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levinson D, Malone MJ. 1980. Toward explaining human culture: a critical review of the findings of worldwide cross-cultural research. New Haven, CT: Human Relations Area Files. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murdock GP. 1967. Ethnographic atlas: a summary. Ethnology 6, 109–236. ( 10.2307/3772751) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skoggard I, Ember C, Pitek E, Carulus C, Jackson JC. In press. Resource stress predicts changes in religious belief and increases in sharing behavior. Hum. Nat. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Botero CA, Gardner B, Kirby KR, Bulbulia J, Gavin MC, Gray RD. 2014. The ecology of religious beliefs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 16 784–16 789. ( 10.1073/pnas.1408701111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hofstede G, Hofstede GJ, Minkov M. 2005. Cultures and organizations: software of the mind, vol. 2. New York, NY: Mcgraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwartz SH. 1994. Beyond individualism/collectivism: new cultural dimensions of values. In Cross-cultural research and methodology series, Vol. 18. Individualism and collectivism: theory, method, and applications (eds Kim U, Triandis HC, Kâğitçibaşi Ç, Choi S-C, Yoon G), pp. 85–119. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carpenter S. 2000. Effects of cultural tightness and collectivism on self-concept and causal attributions. Cross Cult. Res. 34, 38–56. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data and code from this study can be found at https://osf.io/93keq/.