Abstract

Purpose:

To understand why a housing mobility experiment caused harmful effects on adolescent boys’ risky behaviors.

Methods:

Moving to Opportunity (MTO) (1994–2010) randomly assigned volunteer families to a treatment group receiving a Section 8 rental voucher or a public housing control group. Our outcome was a global risky behavior index (RBI; measured in 2002, N=750 boys) measuring the fraction of 10 items the youth engaged in, 6 measuring past 30-day substance use and 4 measuring recent risky sexual behavior. Potential mediators (measured in 2002) included peer social relationships (e.g., peer drug use, peer gang membership).

Results:

The voucher treatment main effect on boys’ RBI was harmful (B(SE)=.05(.02), 95% CI .01, .08), and treatment marginally increased having friends who used drugs compared to controls ((B(SE)=.67(.23), 95% CI .22, 1.12). Having friends who used drugs marginally mediated the MTO treatment effect on RBI (indirect effect: B(SE)=.02(.01), 95% CI −.002, .04), reducing the total treatment effect by 39%.

Conclusions:

Incorporating additional supports into housing voucher programs may help support teenage boys who experience disruptions to their social networks, to buffer potential adverse consequences of residential mobility.

Keywords: Risky Behaviors, Mediation, Peers, Randomized controlled trial, Mobility, Public Housing, Adolescence

INTRODUCTION

Adolescent risky behaviors, such as substance use and risky sexual behavior, may harm health and social development over the life course.1 Given the tendency for these behaviors to escalate and persist into adulthood,2 early identification of the causes of risky behaviors is important for minimizing their public health impacts.3–5 Previous observational studies on residential mobility suggest that frequent residential moves are a stressor for children,6–8 leading to problems during adolescence. Residential mobility negatively impacts risky behaviors,9,10 as well as delinquency,11 behavior problems,12 recidivism,13 and education.6 However, this literature might be confounded by factors that affect mobility choices, such as family socioeconomic status.

A growing literature examining the effects of residential mobility and neighborhood context on health leverages quasi-experimental and experimental data to overcome the potential for confounding in observational data.14 Much of this literature relies on the Moving to Opportunity (MTO) demonstration. MTO randomly assigned low-income families in public housing to receive a voucher to be used in neighborhoods with less than 10% poverty, receive an unrestricted voucher, or remain in public housing.15 The goal was to reduce concentrated poverty and improve economic outcomes for low-income families.16

Interim survey findings (4–7 years after randomization) documented beneficial effects of mobility for adolescent girls, with reductions in psychological distress, lifetime marijuana use, lifetime smoking, and risky behaviors in the treatment group vs. controls.17–21 Boys experienced harmful effects, with increases in psychological distress, behavior problems, smoking, and risky behaviors, compared to controls.17–21 Moreover, the harmful effects on boys’ risky behaviors were concentrated among boys 10 years of age or older at baseline.21 The final survey findings (10–15 years after randomization) showed, among a younger cohort of adolescents, decreased psychological distress, serious behavioral/emotional problems, and alcohol use for girls, but increased lifetime smoking for boys and the total sample.22

It is important to understand why mobility may exert harmful effects for boys, especially because housing vouchers are the largest federal affordable housing mechanism in the United States.23 Yet scarce evidence explains why we see these harmful effects. Few papers have explicitly tested mediation of MTO effects using quantitative methods, and these focused on adult obesity and BMI,24 youth asthma,25 adolescent mental health,26 past 30-day smoking and marijuana use, and past-year problem drug use.27 Qualitative evidence from MTO suggests that boys’ social relationships may be a pathway through which mobility impacts adolescent outcomes, for example, by contributing to the formation of deviant peer groups or the loss of friendships and mentors present in old neighborhoods.28 However, no quantitative studies have tested social context as a mediator of the effects of mobility on boys’ risky behaviors.

To fill this important gap in the literature, this study leverages experimental data and semi-parametric, weight-based mediation methods to examine the causal mechanisms through which MTO increased risky behaviors among treatment group boys. Since MTO is a randomized controlled trial, the effect of MTO on risky behaviors, and of MTO on the hypothesized mediators, is unconfounded by factors such as family socioeconomic status. Given prior qualitative research, we hypothesized that mobility induced by the MTO voucher mechanism may operate through peer social relationship to increase boys’ risky behaviors.

METHODS

Data and Sample

The MTO study, sponsored by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), was a housing mobility experiment conducted in Boston, Baltimore, Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York. Eligible families lived in highly distressed public housing at baseline, qualified for rental assistance, and had children under 18.29 Over 4600 volunteer families were eligible and randomly-assigned using software developed by Abt Associates to one of the following treatment groups from 1994–199815,30: 1) a “low-poverty” group receiving a Section 8 voucher to be used in a neighborhood with less than 10% of residents living in poverty and housing counseling to assist with finding housing; 2) a “Section 8” group receiving only a traditional Section 8 voucher to be used in any neighborhood with no housing counseling; and 3) a control group eligible to remain in public housing. Participants had 90 days to use the voucher, or the voucher was revoked. Surveys were administered at the baseline (1994–1998), interim (2001–2002), and final (2008–2010) evaluations using in-person interviews with household heads and children (up to two randomly-selected per family at interim).17,22 Consent was obtained from adults and youth over 18, and assent from children under 18.15,17,29 The University of Minnesota IRB approved this study.

This study focuses on male youth who completed the baseline and interim surveys (89% effective response rate).17 The harmful treatment effect on risky behaviors was concentrated among boys 10–16 years old at baseline (13–19 years old at interim, 2001–2002), while treatment was nonsignificant at younger ages,21 so we further restrict our analyses to boys aged 10–16 at baseline (N=750). In sensitivity analyses, we estimated all models using the full sample of boys (N=1403). Although final survey data are available,22 we focused on the interim data because boys 10–16 at baseline were ages 23 and older at the final survey, at which point these outcomes are no longer developmentally appropriate; we wanted to understand the impact of housing mobility for outcomes occurring in adolescence.

Measures

Outcomes (measured at interim in 2002):

Risky Behavior Index (RBI):

Risky behavior was measured as the fraction of 10 binary items the youth engaged in, tapping risky substance use (6 items) and sexual behavior (4 items). Risky substance use included past 30-day alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use; alcohol use before/during work or school; marijuana use before/during work or school; and binge drinking. Risky sexual behavior included no condom use during last intercourse, no contraceptive use during last intercourse, early sexual initiation (before age 15), and two or more sexual partners in the past year. The scale ranged from 0 (exhibits no behaviors) to 1 (exhibits all behaviors), and had acceptable reliability (RBI Cronbach’s α = .75). For boys aged 10 or older, the RBI mean(SD) = .15(.24). In sensitivity analyses, we estimated main effect and mediation models for the risky substance use and sexual behavior items as separate scales (risky substance use Cronbach’s α = .74, mean(SD) = .09(.23); risky sexual behavior Cronbach’s α = .64, mean(SD) = .25 (.36)). Outcome missingness was small (1.5% to 5% depending on the outcome), so we analyzed complete cases.

Treatment:

The low poverty and Section 8 voucher groups were combined because of homogenous treatment effects on RBI, so the treatment effect models receipt of a Section 8 housing voucher with or without location restriction (69%), compared to the public housing control group (31%). We estimated all models with the 3 original treatment groups, but, given the lack of power from small group sample sizes, mediation effects were non-significant (results available upon request).

Potential Mediators:

Mediators were self-reported at interim (2002; contemporaneous with outcomes). We examined six aspects of boys’ peer groups: whether boys’ friends used drugs, belonged to a gang, carried weapons, or were involved in school activities, whether boys still had friends in their baseline neighborhoods, and their total number of friends. All measures were binary (yes/no) except for total number of friends (count).

Baseline Confounders:

Baseline covariates associated with the outcome or that were imbalanced across treatment groups were included in the model to adjust for potential confounding of the mediator-outcome relationship, since the mediators were not randomized. Confounders included site; youth age, learning problems, behavior problems, school problems, expulsion, problems requiring special medicine/equipment or (separately) that interfere with school/play; household head was teen parent, on welfare, enrolled in school at baseline, education level.

Analytic Approach

We estimated the total effect of MTO treatment on RBI using intent-to-treat (ITT) models appropriate for a randomized controlled trial (RCT) using covariate-adjusted linear regression. We then estimated first-leg ITT models predicting potential mediators from treatment in covariate-adjusted regression models (functional form appropriate to the outcome), to identify potential mediators. We also estimated main effect and first-leg models using instrumental variable (IV) analysis to adjust for compliance, since only 31% of boys in our sample moved using the voucher.

If treatment predicted a mediator, we then estimated inverse odds ratio weighted mediation models31,32 to decompose the ITT total effect into the natural indirect effect (NIE - the treatment effect operating through the mediator), and the natural direct effect (NDE - the treatment effect not operating through the mediator).33 Mediation is indicated by the NIE. To characterize the magnitude of mediation, we calculated the percent change in the total effect as (direct effect-total effect)/total effect. A negative percent change indicates a decrease in the effect of MTO after accounting for a mediator. All models applied survey weights, adjusted for family-level clustering, and were estimated using Stata 14.0.

Inverse Odds Ratio Weighting (IORW).

IORW is a semiparametric causal mediation method with several advantages: 1) it can perform effect decomposition on nonlinear mediators and outcomes, 2) it can model multiple mediators simultaneously, and 3) it does not need to specify complex interactions that exist between treatment and mediators because they are captured in the weight.31,32 IORW deactivates all indirect pathways through the mediator by condensing information on the treatment-mediator relationship into a weight, allowing one to estimate the direct effect of treatment on the outcome. The indirect effect is calculated by subtracting the direct effect from the total effect. Details and code have been presented previously.32 Briefly, IORW is estimated in five steps. First, estimate the predicted odds from a logistic regression predicting treatment from the mediator and covariates; here we use the predicted odds rather than the odds ratio to obtain a stabilized weight. Second, calculate the inverse odds weight (IOW) by taking the inverse of the predicted odds, and set all controls to a value of 1. Third, estimate the total effect of treatment on the outcome. Fourth, estimate the same model as in step 3, but apply the IOW to neutralize the treatment effect operating through the mediator; this provides the direct effect. Fifth, calculate the indirect effect by subtracting the direct effect from the total effect. Direct and indirect effect standard errors were obtained using bootstrapping with 1000 replications.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents baseline descriptive statistics by treatment group for boys aged 10–16 at baseline. Boys were primarily African American (59.3%) and Hispanic (33.9%), and were 12 years old on average at baseline. The majority of household heads received welfare (74.3%) and half did not have a high school diploma or GED (50.8%). All but two baseline covariates were balanced across treatment, as expected given randomization: treatment group boys were more likely to report problems interfering with school/play, and less likely to take a class for gifted students or do advanced work (Table 1). Treatment boys fared worse than controls on all risky behavior outcomes and most mediators, with the exception of peer gang membership (Table 2; see Supplemental Table 1 for mediators and outcomes on the full sample of boys).

Table 1.

Moving to Opportunity Baseline Variables (1994–1997) among Boys 10–16 Years Old at Baseline, Overall and by Treatment Group

| Treatment Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | Variable | Overall | Treatment | Controls | pa |

| Total in Interim Survey in 2002 | N | 750 | 534 | 216 | |

| Baseline mean poverty rate | Percent poverty rate in the 1990 census tract | 50.8% | 50.7% | 51.0% | |

| Family Characteristics | |||||

| Victimization | Household member victimized by crime during past 6 months | 45.9% | 44.9% | 48.1% | |

| Site | Baltimore | 11.2% | 12.1% | 9.1% | |

| Boston | 15.5% | 14.5% | 18.0% | ||

| Chicago | 24.5% | 26.5% | 19.4% | ||

| Los Angeles | 21.8% | 20.2% | 25.6% | ||

| New York | 27.0% | 26.6% | 27.8% | ||

| Household size | 2 people | 5.8% | 5.3% | 7.2% | |

| 3 people | 19.2% | 18.8% | 20.1% | ||

| 4 people | 24.4% | 25.1% | 22.6% | ||

| 5 or more people | 50.6% | 50.8% | 50.1% | ||

| Youth Characteristics | |||||

| Age (in years) | 11.8 | 11.9 | 11.7 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | African American | 59.3% | 61.2% | 54.8% | |

| Hispanic ethnicity, any race | 33.9% | 34.1% | 33.5% | ||

| White | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | ||

| Other race | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | ||

| Missing race | 6.7% | 4.7% | 11.7% | ||

| Gifted | Special class for gifted students or did advanced work | 18.4% | 15.2% | 26.4% | * |

| Developmental Problems | Special school, class, or help for learning problem in past 2 years | 27.0% | 27.1% | 26.7% | |

| Special school, class, or help for behavioral or emotional problems in past 2 years | 12.2% | 13.9% | 7.8% | ||

| Problems that made it difficult to get to school and/or to play active games | 8.0% | 9.6% | 3.8% | * | |

| Problems that required special medicine and/or equipment | 11.7% | 12.9% | 8.8% | ||

| School asked to talk about problems child having with schoolwork or behavior in past 2 years | 36.7% | 38.8% | 31.4% | ||

| Household Head Characteristics | |||||

| Family Structure | Never married | 53.2% | 52.2% | 55.5% | |

| Teen parent | 25.8% | 25.8% | 25.7% | ||

| Socioeconomic Status | Employed | 29.7% | 32.0% | 24.2% | |

| On AFDC (welfare) | 74.3% | 73.3% | 76.8% | ||

| Education | Less than high school | 50.8% | 51.0% | 50.5% | |

| High school diploma | 14.5% | 14.7% | 14.1% | ||

| GED | 34.6% | 34.3% | 35.5% | ||

| In School | 12.0% | 12.3% | 11.1% | ||

| Neighborhood/Mobility Variables | Lived in neighborhood 5 or more years | 69.0% | 69.4% | 68.1% | |

| No family living in neigh | 62.9% | 62.0% | 65.3% | ||

| No friends living in neigh | 34.2% | 34.0% | 34.6% | ||

| Had applied for section 8 voucher before | 43.6% | 44.3% | 42.0% | ||

| Neighbor Relationships | Chats with neighbors at least once a week | 51.2% | 50.8% | 52.1% | |

| Respondent very likely to tell neighbor if saw neighbor’s child getting into trouble | 56.0% | 56.1% | 55.6% | ||

p<.05

P-value from test of treatment group differences calculated from Wald chi-square tests outputted from logistic regression for dichotomous baseline characteristics and multinomial logistic regression for categorical characteristics. F-tests were used with linear regression for continuous variables. The null hypothesis is that the treatment and control group proportions or means did not differ. NOTES: All variables range between 0 & 1 except baseline age (5–16) and mean poverty rate, so means represent proportions. Analysis weighted for varying treatment random assignment ratios across time, and for attrition. All tests were adjusted for clustering at the family level. Regression analyses were adjusted for site.

Table 2.

Moving to Opportunity Outcome and Mediator Descriptive Statistics (at Interim, 2001–2002), among Boys 10–16 Years Old at Baseline.

| Treatment | Control | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | p |

| Risky Behavior Index | 510 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 201 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.01 |

| Risky Substance Use | 522 | 0.15 | 0.28 | 213 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.001 |

| Risky Sexual Behavior | 503 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 199 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.18 |

| Mediators | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | |

| Peer Drug Use (binary) | 487 | 0.46 | 0.61 | 198 | 0.32 | 0.58 | 0.01 |

| Peer Gang Membership (binary) | 506 | 0.13 | 0.41 | 204 | 0.21 | 0.49 | 0.04 |

| Friends in Baseline Neighborhood (binary) | 515 | 0.66 | 0.58 | 212 | 0.73 | 0.54 | 0.04 |

| Peer Weapon Use (binary) | 500 | 0.17 | 0.46 | 207 | 0.15 | 0.44 | 0.35 |

| Peer Involvement in School Activities (binary) | 512 | 0.66 | 0.57 | 200 | 0.70 | 0.57 | 0.16 |

| Number of Friends (count) | 534 | 7.24 | 7.70 | 216 | 7.23 | 7.92 | 0.78 |

IOW Mediation.

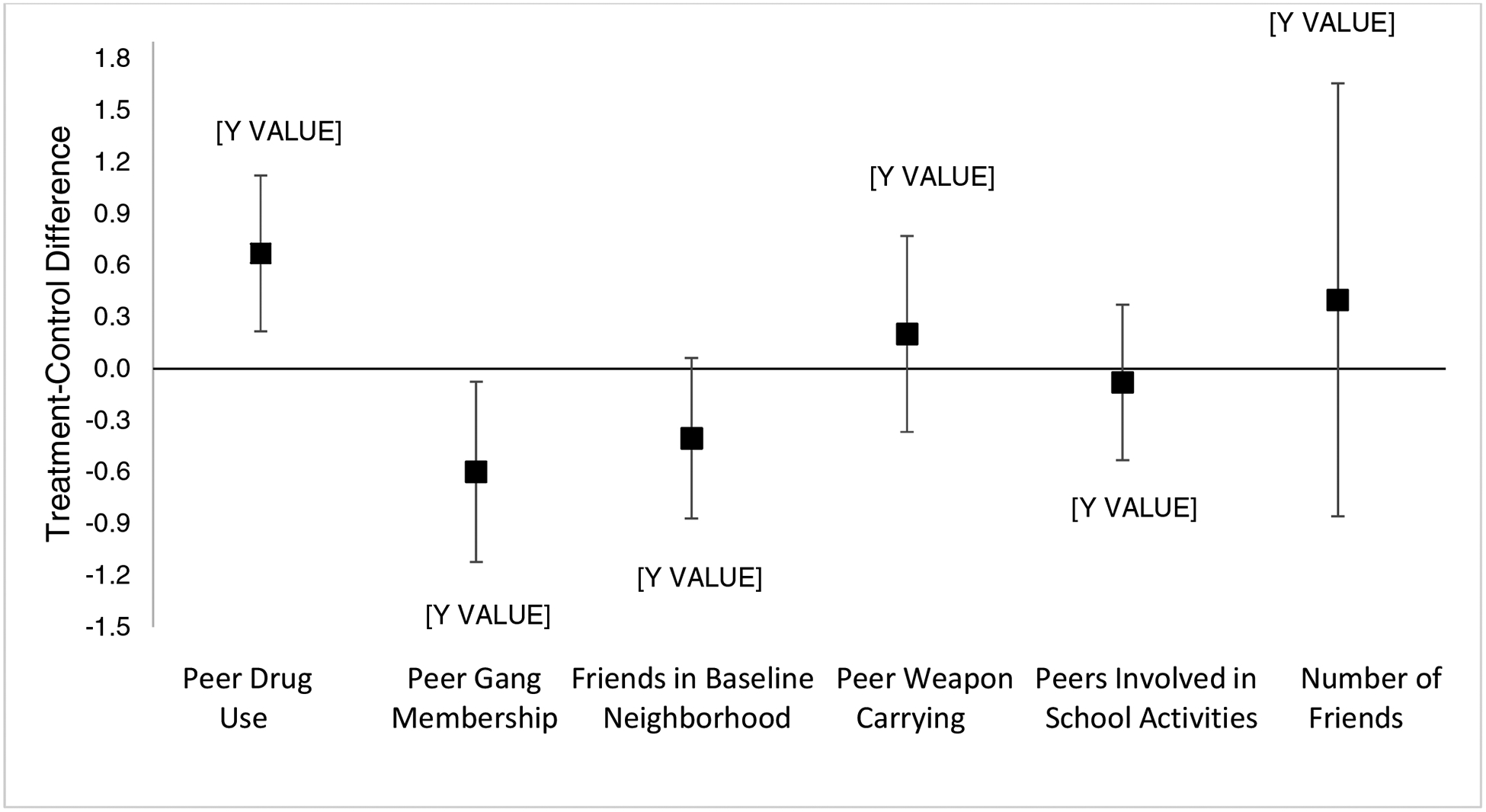

The total effect of MTO treatment on boys’ RBI was higher (harmful) (B(SE) = .05(.02), p = .02, 95% CI: .01, .08), compared to controls. This is an effect size of .19 (Cohen’s D), considered a small effect.34 We estimated first-leg models of the treatment effect on potential mediators to identify variables that may mediate the harmful total effect of MTO on boys’ RBI (Figure 1 and Supplemental Table 2). Although MTO treatment decreased having friends who belonged to a gang membership, it also increased having friends who used drugs and marginally decreased having friends from the baseline neighborhood, compared to controls. MTO effects on peer weapon carrying, peer involvement in school activities, and number of friends were nonsignificant. Since mediation requires a treatment-mediator association, we did not test mediation for variables with nonsignificant treatment associations. These patterns were replicated among the total sample of boys (Supplemental Table 3). IV models showed similar main effect and first-leg results, with IV effects over twice as large as ITT (Supplemental Tables 4 and 5).

Figure 1.

First-leg ITT Effects of Moving to Opportunity Treatment on Potential Mediators (at Interim, 2001–2002), among Boys 10–16 Years Old at Baseline.

Peer drug use partially mediated the harmful relationship between MTO treatment and boys’ RBI, as evidenced by its marginally significant indirect effect (Table 3 and Figure 2). Peer drug use accounted for 39% of the MTO treatment effect on boys’ RBI, comparing the total to the direct effect. Peer gang membership and having friends in the baseline neighborhood did not account for the harmful MTO treatment effect on RBI.

Table 3.

Natural Indirect effects (NIE) and Natural Direct Effects (NDE) of Moving to Opportunity Treatment on Risky Behavior Index (RBI), Risky Substance Use (RSU), and Risky Sexual Behavior (RSB) (at Interim, 2001–2002), among Boys 10–16 Years Old at Baseline.

| Risky Behavior Index | Risky Substance Use | Risky Sexual Behavior | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p | LCI | UCI | B | SE | p | LCI | UCI | B | SE | p | LCI | UCI | |

| MTO Treatment Main Effect | 0.045 | 0.018 | 0.015 | 0.009 | 0.081 | 0.059 | 0.018 | 0.001 | 0.024 | 0.094 | 0.019 | 0.028 | 0.495 | −0.036 | 0.074 |

| Peer Drug Use | B | SE | p | LCI | UCI | B | SE | p | LCI | UCI | B | SE | p | LCI | UCI |

| NIE | 0.017 | 0.009 | 0.077 | −0.002 | 0.035 | 0.017 | 0.009 | 0.057 | −0.001 | 0.035 | 0.015 | 0.013 | 0.272 | −0.011 | 0.04 |

| NDE | 0.027 | 0.02 | 0.177 | −0.012 | 0.065 | 0.043 | 0.019 | 0.023 | 0.006 | 0.08 | 0.002 | 0.033 | 0.96 | −0.063 | 0.066 |

| % Change | −39.4% | −26.8% | −89.5% | ||||||||||||

| Peer Gang Membership | B | SE | p | LCI | UCI | B | SE | p | LCI | UCI | B | SE | p | LCI | UCI |

| NIE | −0.002 | 0.008 | 0.844 | −0.017 | 0.014 | −0.005 | 0.008 | 0.56 | −0.02 | 0.011 | 0.002 | 0.013 | 0.908 | −0.024 | 0.027 |

| NDE | 0.037 | 0.021 | 0.076 | −0.004 | 0.077 | 0.049 | 0.02 | 0.013 | 0.01 | 0.088 | 0.018 | 0.032 | 0.571 | −0.044 | 0.08 |

| % Change | −16.9% | −16.6% | −5.2% | ||||||||||||

| Friends in Baseline Neighborhood | B | SE | p | LCI | UCI | B | SE | p | LCI | UCI | B | SE | p | LCI | UCI |

| NIE | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.882 | −0.015 | 0.017 | −0.002 | 0.008 | 0.824 | −0.016 | 0.013 | 0.003 | 0.013 | 0.818 | −0.022 | 0.028 |

| NDE | 0.043 | 0.02 | 0.032 | 0.004 | 0.083 | 0.06 | 0.019 | 0.001 | 0.023 | 0.097 | 0.017 | 0.031 | 0.573 | −0.043 | 0.078 |

| % Change | −3.5% | 2.1% | −10.4% | ||||||||||||

NOTES: Models adjusted for site; youth age, race/ethnicity, learning problems, behavior problems, school problems, expulsion, problems requiring special medicine/equipment or (separately) that interfere with school/play, attended gifted classes; household head was teen parent, employed, on welfare, enrolled in school at baseline, education level, moved more than 3 times in past 5 years, moved for better schools, had no friends in the neighborhood.

Figure 2.

Natural Indirect, Natural Direct, and Total Effects of Moving to Opportunity Treatment on Risky Behavior Index (at Interim, 2001–2002), among Boys 10–16 Years Old at Baseline.

Sensitivity Analyses.

Mediation models including younger boys (aged 5–16 at baseline), produced similar patterns (Supplemental Table 6). MTO treatment effects on RBI were harmful but weaker (as expected) than among 10 to 16-year-old boys, translating to a Cohen’s D effect size of .09, likely because the nonsignificant effect among younger boys dilutes the effect. Despite this weaker first-leg effect, peer drug use continued to emerge as a mediator, mediating 59% of the effect on RBI.

The pattern of results for risky substance use was similar to RBI, with peer drug use mediating 27% of the harmful MTO treatment effect (Table 3). Mediation models among the total sample of boys (aged 5–16 at baseline) demonstrated similar patterns (Supplemental Table 6), with peer drug use mediating 24% of the effect on risky substance use. Peer gang membership and baseline neighborhood friends did not mediate MTO treatment effects on risky substance use. Treatment group boys exhibited no increased risky sexual behavior, compared to controls, thus no variables were identified as mediators (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This study applied semi-parametric, weight-based causal mediation to test peer social relationships as a mechanism through which MTO-induced residential mobility increased boys’ risky behaviors. Of the measures available to characterize boys’ peer relationships, three were changed by MTO treatment, making them candidate mediators. Compared to control group boys, treatment group boys were less likely to have friends in gangs or friends from their baseline neighborhoods, but more likely to have friends who used drugs. How boys are socialized likely plays a role in how they form peer groups in their new neighborhoods. In poor neighborhoods, boys are conditioned to carry themselves in a way that earns respect.35 Ways of behaving, speaking, and dressing that are considered ‘dominant’ cultural capital in higher poverty neighborhoods might be ‘non-dominant’ cultural capital in lower poverty neighborhoods36, and these behaviors suddenly fall outside of social norms.37 Ultimately, this may marginalize boys in lower poverty neighborhoods, leading them to select into more deviant peer groups.28

Having friends who used drugs emerged as the only mediator of the effect of mobility on boys’ risky behaviors. This result aligns with evidence that peer risky behavior affects an adolescent’s risky behaviors.38,39 Although the indirect effect was marginally significant, friends’ drug use reduced the total effect of MTO by 39 percent. Restricting the sample to 10–16 year old boys reduced our power, likely explaining why the effect of friend’s drug use was only marginally significant despite a sizeable percent reduction in the total effect. Sensitivity analyses among all boys (aged 5–16 at baseline), showed a weaker, marginally significant total effect on risky behaviors, but friends’ drug use remained a statistically significant mediator, explaining 59% of the total effect.

MTO slightly reduced the likelihood that boys had friends in their baseline neighborhood (a marginally significant effect). One might expect that the loss of social support could explain the detrimental effect on risky behaviors. However, we did not find that losing friends from the baseline neighborhoods affected boys’ risky behaviors. Perhaps the loss of social support is not the most critical pathway, but rather it is who boys end up associating with in their new neighborhoods.

Limitations

Since the mediators and outcomes were measured contemporaneously, it is unclear whether peer groups promote one’s own risky behaviors, or vice versa. Although some studies suggest that adolescents with risky behaviors self-select into more deviant peer groups,40 other studies do not.41 Moreover, since these analyses are restricted to older children (10–16 years old at baseline), many would have already begun engaging in risky behaviors by study baseline – the randomized design ensures balance among treatment groups at baseline in all factors, thus we would expect the impact of self-selection to be even across groups. It is also likely that peers use of drugs is measured with error. Since measurement error of this mediator is not patterned by exposure (i.e., nondifferentially misclassified), it is possible that the natural indirect effect is biased toward the null, and thus is underestimated.42

Our results present natural direct and indirect effects of being offered a housing voucher from ITT analyses, because IOW mediation does not accommodate estimating IV per protocol analyses. Only 31% of boys in our analytic sample moved with a voucher, thus ITT effects were diluted relative to IV effects. The identification of natural direct and indirect effects relies on the assumption that the mediator-outcome relationship is unconfounded by post-randomization variables, which may be unrealistic in an RCT with imperfect compliance.27 New methods do not rely on this assumption. One such MTO study tested the effects of school and peer factors on substance use, and found that having peers who used drugs continued to exert a small mediating effect on these outcomes, after adjusting for compliance.27 Although this is a valuable methodological innovation, from a policy standpoint, the ITT effect remains substantively important, since policy makers cannot force compliance. That we see similar findings for the effect of peer drug use using two different mediation methods, with different assumptions, and on distinct outcomes lends confidence in our findings that this is an important mediating mechanism.

Conclusion and Implications

Housing vouchers, such as the treatment administered in MTO, remain the largest mechanism to provide low-income families with affordable housing in the US, making this study policy-relevant with high potential for translation.43 Since boys experience harmful effects as a result of this prominent federal policy, it is important to identify pathways to minimize the negative impacts. This study suggests that adolescent boys may need additional supports to promote the development of prosocial peer groups that will allow them to succeed in new neighborhoods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements/Funding Source:

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant 1R03HD082679 (Dr. Schmidt, PI) and 1R21AA024530 (Dr. Osypuk, PI). The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the Minnesota Population Center (P2C HD041023) funded through a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). Funders did not have any role in design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) had no role in the analysis or the preparation of this manuscript. HUD reviewed the manuscript to ensure respondent confidentiality was maintained in the presentation of results.

Financial Disclosure Statement: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Abbreviations:

- MTO

Moving to Opportunity

- RCT

Randomized Controlled Trial

- HUD

US Department of Housing and Urban Development

- RBI

Risky Behavior Index

- ITT

intent-to-treat

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Ries Merikangas K. Mood disorders in children and adolescents: an epidemiologic perspective. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49(12):1002–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingoldsby EM, Shaw DS. Neighborhood Contextual Factors and Early-Starting Antisocial Pathways [Article]. Springer Science & Business Media B.V; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses-United States, 1997–2001. MMWR. 2005;54:625–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(1):64–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King RD. The Co-Occurrence of Psychiatric and Substance Use Diagnoses in Adolescents in Different Service Systems: Frequency, Recognition, Cost, and Outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2000;27:417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leventhal T, Newman S. Housing and child development. Children and youth service review. 2010;32(9):1165–1174. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jelleyman T, Spencer N. Residential mobility in childhood and health outcomes: A systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2008;62:584–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mok PL, Webb RT, Appleby L, Pederson CB. Full spectrum of mental disorders linked with childhood residential mobility. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2016;78:57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The Neighborhoods They Live In: The Effects of Neighborhood Residence on Child and Adolescent Outcomes. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126(2):309–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Browning CR, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Neighborhood context and racial differences in early adolescent sexual activity. Demography. 2004;41(4):697–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.South S, Haynie D, Bose S. Residential mobility and the onset of adolescent sexual activity. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67(2):499–514. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adam EK, Chase-Lansdale PL. Home sweet home(s): Parental separations, residential moves, and adjustment problems in low-income adolescent girls. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(5):792–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolff KT, Baglivio MT, Intravia J, Greenwald MA, Epps N. The mobility of youth in the justice system: Implications for recidivism. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2017;46:1371–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt N, Nguyen Q, Osypuk T. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs in neighborhood health effects research: Strengthening causal inference and promoting translation In: Duncan D, Kawachi I, eds. Neighborhoods and Health, Second Edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goering J, Kraft J, Feins J, McInnis D, Holin M, Elhassan H. Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program: Current Status and Initial Findings. Washington, DC: US Department of Housing & Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research;1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goering J, Feins J. Choosing a Better Life? Evaluating the Moving to Opportunity Social Experiment. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orr L, Feins J, Jacob R, et al. Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program: Interim Impacts Evaluation. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research;2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kling J, Liebman J, Katz L. Experimental analysis of neighborhood effects. Econometrica. 2007;75(1):83–119. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osypuk T, Tchetgen Tchetgen E, Acevedo-Garcia D, et al. Differential mental health effects of neighborhood relocation among youth in vulnerable families. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(12):1284–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osypuk T, Schmidt N, Bates L, Tchetgen-Tchetgen E, Earls F, Glymour M. Gender and crime victimization modify neighborhood effects on adolescent mental health. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):472–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt NM, Glymour MM, Osypuk TL. Adolescence is a sensitive period for housing mobility to influence risky behaviors: An experimental design. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2017;60(4):431–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanbonmatsu L, Ludwig J, Katz LF, et al. Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program: Final Impacts Evaluation. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research;2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Low Income Housing Coalition. Federal Budget & Approps, HUD Budget Charts, FY11 and FY12 Budget Chart for Selected HUD Programs, Updated April 27, 2011 https://www2398.ssldomain.com/nlihc/template/page.cfm?id=28http://www.nlihc.org/doc/FY11_12_Budget_Chart_HUD.pdf. Published 2011 Accessed 4/29/11, 2011.

- 24.Zhao Z, Kaestner R, Xu X. Spatial mobility and environmental effects on obesity. Economics and Human Biology. 2013; 10.1016/j.ehb.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt NM, Lincoln AK, Nguyen QC, Acevedo-Garcia D, Osypuk TL. Examining mediators of housing mobility on adolescent asthma: Results from a housing voucher experiement. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;107:136–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmidt NM, Glymour MM, Osypuk TL. Housing mobility and adolescent mental health: The role of substance use, social networks, and family mental health in the Moving to Opportunity Study. SSM - Population Health. 2017;3:318–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rudolph KE, Sofrygin O, Schmidt NM, et al. Mediation of neighborhood effects on adolescent substance use by the school and peer environments. Epidemiology. 2018;29(4):590–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clampet-Lundquist S, Edin K, Kling J, Duncan G. Moving teenagers out of high-risk neighorhoods: How girls fare better than boys. American Journal of Sociology. 2011;116(4):1154–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feins JD, McInnis D. The Interim Impact Evaluation for the Moving to Opportunity Demonstration, C-OPC-21484. Cambridge, MA: Abt Associates Inc; August 14, 2001 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goering J, Feins J, Richardson T. A Cross-Site Analysis of Initial Moving to Opportunity Demonstration Results. Journal of Housing Research. 2002;13(1):1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tchetgen Tchetgen E Inverse odds ratio-weighted estimation for causal mediation analysis. Statistics in Medicine. 2013;32(26):4567–4580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen Q, Osypuk T, Schmidt N, Glymour M, Tchetgen Tchetgen E. Practical guide for conducting mediation analysis with multiple mediators using inverse odds ratio weighting. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2015;181(5):349–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearl J Direct and indirect effects. Paper presented at: Proceedings of the seventeenth conference on uncertainty in artificial intelligence 2001; San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen J Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson E Streetwise: Race, Class, and Change in an Urban Community. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carter PL. “ Black” cultural capital, status positioning, and schooling conflicts for low-income African American youth. Social problems. 2003;50(1):136–155. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pattillo M Black on the block: The politics of race and class in the city. University of Chicago Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loke AY, Mak Y-w. Family process and peer influences on substance use by adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2013;10:3868–3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ajilore O Identifying peer effects using spatial analysis: the role of peers on risky sexual behavior. Review of Economics of the Household. 2015;13(3):635–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scaramella LV, Conger RD, Spoth R, Simons RL. Evaluation of a Social Contextual Model of Delinquency: A Cross-Study Replication. Child Development. 2002;73(1):175–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trudeau L, Mason WA, Randall GK, Spoth R, Ralston E. Effects of Parenting and Deviant Peers on Early to Mid- Adolescent Conduct Problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40(8):1249–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ogburn EL, VanderWeele TJ. Analytic results on the bias due to nondifferential misclassification of a binary mediator. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2012;176(6):555–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glymour MM, Osypuk TL, Rehkopf DH. Invited commentary: Off-roading with social epidemiology - exploration, causation, translation. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;178(6):858–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.