Abstract

Objective:

To assess the efficacy of non-hormonal, hyaluronic acid (HLA)-based vaginal gel in improving vulvovaginal estrogen-deprivation symptoms in women with a history of endometrial cancer.

Methods:

For this single-arm, prospective, longitudinal trial, we enrolled disease-free women with a history of endometrial cancer who underwent surgery (total hysterectomy) and postoperative radiation. Participants used HLA daily for the first 2 weeks, and then 3x/week until weeks 12-14; dosage was then increased to 5x/week for non-responders. Vulvovaginal symptoms and pH were assessed at 4 time points (baseline [T1]; 4-6 weeks [T2]; 12-14 weeks [T3]; 22-24 weeks [T4]) with clinical evaluation, the Vaginal Assessment Scale (VAS), Vulvar Assessment Scale (VuAS), Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), and Menopausal Symptom Checklist (MSCL).

Results:

Of 43 patients, mean age was 59 years (range, 38-78); 54% (23/43) were partnered; and 49% (21/43) were sexually active. VAS, VuAS, MSCL, and SAQ (Sexual Activity Questionnaire) scores significantly improved from baseline to each assessment point (all p<.002). FSFI total mean scores significantly increased from T1 to T2 (p<.05) and from T1 to T4 (p<.03). At T1,41% (16/39) felt confident about future sexual activity compared to 68% (17/25) at T4 (p=.096). Severely elevated vaginal pH (>6.5) decreased from 30% (13/43) at T1 to 19% (5/26) at T4 (p=.41).

Conclusion:

The HLA-based gel improved vulvovaginal health and sexual function of endometrial cancer survivors in perceived symptoms and clinical exam outcomes. HLA administration 1-2x/week is recommended for women in natural menopause; a 3-5x/week schedule appears more effective for symptom relief in cancer survivors.

Keywords: endometrial cancer, hyaluronic acid, non-hormonal vaginal moisturizer, vulvar health, vaginal health, sexual function

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic cancer and the fourth most common cancer overall among women. It is estimated that 65,620 cases of endometrial cancer will be diagnosed in 2020. [1, 2]. The 5-year survival rate for all stages of endometrial cancer combined is approximately 81% [3]. For cases detected at the localized stage (nearly 70%), the 5-year survival rate increases to 95% [2]. There are more than 600,000 endometrial cancer survivors in the United States, and the prevalence of sexual dysfunction among this patient population is approximately 90% [2,3]. Studies have indicated that treatment modalities, including surgery, chemotherapy and radiation, significantly reduce sexual function and quality of life (QOL) through a series of long-term physical and psychological changes [4]. Menopause triggered by cancer treatment is qualitatively different from natural menopause; it is typically abrupt, with more intense and prolonged estrogen-deprivation symptoms. This often results in more chronic side effects to the vagina and surrounding tissues than gradual menopausal decline. External-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) and intravaginal brachytherapy (IVRT) remain integral aspects of adjuvant therapy and are associated with vulvovaginal changes such as dryness, stenosis, and atrophy [5]. Furthermore, hysterectomy type and lack of vaginal lubricant use are significant indicators for sexual dysfunction in endometrial cancer survivors [5]. While local vaginal treatment with estrogen is effective in reversing atrophic vaginal changes and relieving symptoms, many women tend to decline intravaginal low-dose hormonal therapies due to their fear of systemic absorption and any potential risk of cancer recurrence [4, 6]. Effective natural, non-hormonal therapies are needed to address the sexual health concerns of endometrial cancer survivors.

Non-hormonal vaginal gels containing hyaluronic acid (HLA) for postmenopausal populations have been gaining interest in Europe and more recently in the United States. HLA sodium salt retains high amounts of water due to its high molecular weight and has a moisturizing effect on the epithelium, thereby promoting epithelial elasticity of tissues. Findings from recent studies have supported HLA vaginal gel as an effective treatment in relieving menopausal symptoms [7–12]. In a study by Laliscia et al., the use of topical HLA therapy demonstrated a clinical benefit for intermediate-risk endometrial cancer patients receiving adjuvant vaginal brachytherapy following surgery [13]. Yet there are limited data regarding HLA’s benefits and impact on sexual function in female cancer patients. To address these gaps in the literature, we sought to examine the feasibility and efficacy of sustained HLA use in endometrial cancer survivors.

Our study aims were (1) to investigate the feasibility of a 12-week HLA treatment regimen, indicated by the percentage of endometrial cancer patients who completed the 12-week assessment and by patient-reported satisfaction with the treatment; (2) to evaluate the efficacy of 12 weeks of treatment with an HLA-based vaginal gel on improving vaginal and vulvar health, as well as sexual function; and (3) to explore whether a more frequent schedule of HLA administration during weeks 12–24 could improve vaginal and vulvar health in those who showed no improvement at the 12-week assessment point (i.e., non-responders).

METHODS

Study design

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK)’s Institutional Review Board approved this single-arm, prospective, longitudinal study examining the feasibility and efficacy of using an HLA-based vaginal gel to improve estrogen deprivation symptoms of vulvovaginal dryness and discomfort in women with a history of endometrial cancer.

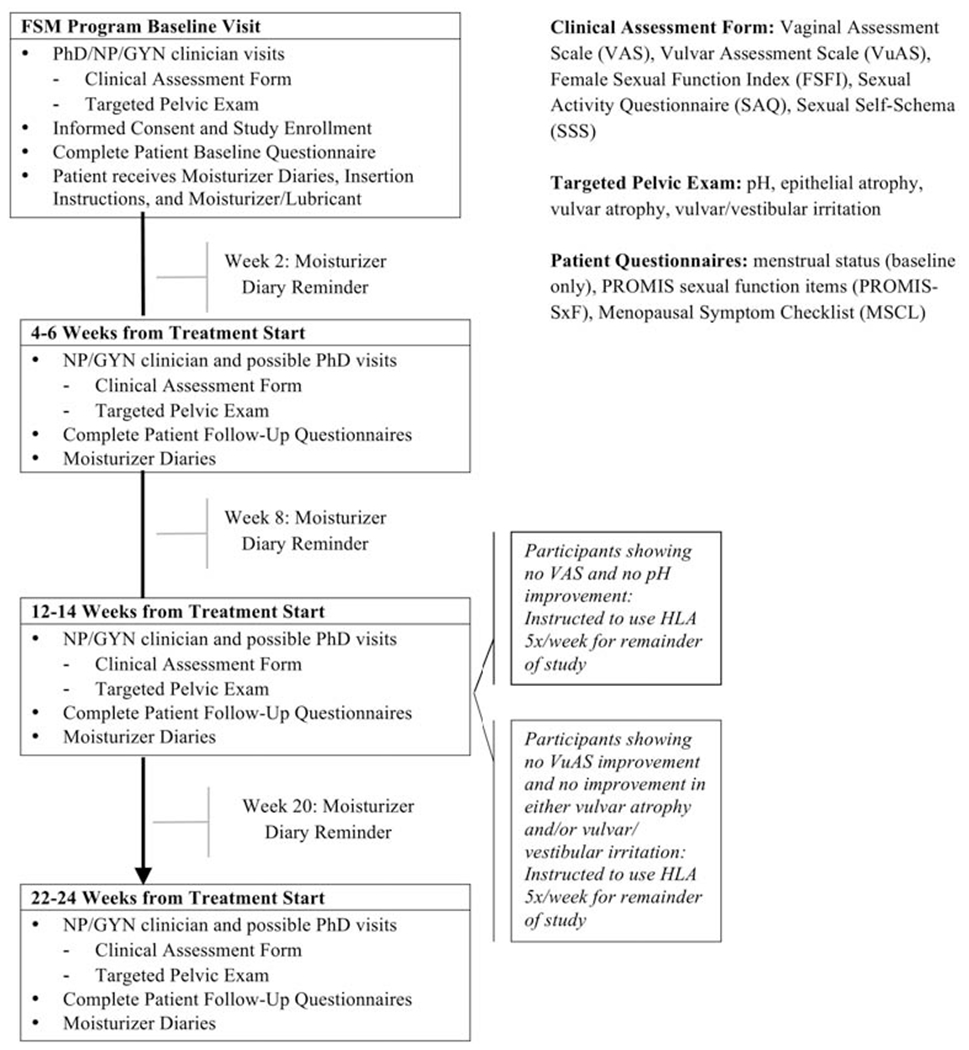

Potential participants experiencing vulvovaginal symptoms (i.e., vulvovaginal dryness or discomfort [pain with intercourse or examination]) were referred to a Female Sexual Medicine Program (FSMP) at MSK. After obtaining informed consent, clinical exam and patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures were collected at baseline (pretreatment) and at 4-6 weeks, 12-14 weeks, and 22-24 weeks (Figure 1). Data collection occurred from June 2013 through December 2017.

Figure 1.

Study schema

Study cohort

Eligible participants included postmenopausal women with a history of endometrial cancer who had undergone surgical treatment (total hysterectomy) and had completed radiation therapy (EBRT or IVRT) 1-60 months and/or chemotherapy 3-60 months prior to enrollment. Potential participants were excluded for any vaginal bleeding of unknown etiology within 12 months of study entry and/or concurrent use of local or systemic hormone replacement therapy.

All participants reported being bothered by estrogen deprivation symptoms (i.e., vulvovaginal dryness or discomfort with intercourse or examination), were currently not consistently using any vaginal health-promotion strategies, had no current clinical evidence of disease, and had no cancer history outside of endometrial cancer (with the exception of non-melanoma skin cancer). Any woman with active hormone replacement therapy (local or systemic) was not considered eligible for this study unless she had discontinued hormone replacement therapy 2 weeks prior to study enrollment.

Potential participants were screened for eligibility at the FSMP, were given a description of the study, and invited to participate. All participants received the standard-of-care intervention at the FSMP, including education about common changes in vaginal/vulvar symptoms and sexual health after cancer treatment, psychosexual education about the sexual response, recommendations for vulvovaginal health promotion, and the benefit and instruction for dilators and pelvic floor exercises in the post-RT setting. Baseline data were collected on the day of study consent, and participants began HLA-based treatment within 1 week of their baseline exam, with instruction on how to use the product for the duration of the 24 weeks on study.

Study Intervention

The HLA-based product used in this study was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in 2010. The principal component of the hydrating gel is a hyaluronic acid derivative. Other components include propylene glycol, carbomer (Carbopol 974P), methyl p-hydroxy-benzoate, propyl p-hydroxybenzoate, sodium hydroxide, and purified water. Participants were instructed to measure a full application of the HLA-based vaginal gel and insert it into the vagina (using the applicator provided) and to measure another full application and apply it on the vulva (manually) every day at bedtime for the first 2 weeks and then 3 times per week for 10-12 weeks. At 12-14 weeks, all participants were re-assessed for improvement in vaginal pH and Vaginal Assessment Scale (VAS) score, as well as improvement in vulvar atrophy and/or vulvar/vestibular irritation and Vulvar Assessment Scale (VuAS) score. Participants were required to keep a moisturizer diary to record the date and time of HLA vaginal gel administration, was and these data were collected at their appointments. In order to be considered eligible for the protocol, participants had to complete at least 75% of the total dosage. Those who did not use (vaginal) or apply (vulvar) at least 75% of the total dosage were taken off study and counted as treatment failures for the purpose of the feasibility endpoint. Clinical team members consisted of a psychologist (PhD), FSMP nurse practitioner (NP), and general gynecologist (MD). Symptoms were recorded on the Female Sexual Medicine Clinical Assessment Form (FSMCAF) as part of routine clinical care. Participants completed an additional questionnaire about their experience with the HLA-based gel and their acceptability of and satisfaction with the product at study completion (24 weeks).

Vaginal symptom improvement was assessed based on change in VAS score and vaginal pH. Vulvar symptom improvement was assessed based on change in vulvar atrophy and/or vulvar/vestibular irritation on exam and the VuAS. For those with noted improvement, the HLA-based product was continued at 3 times per week for study duration. Women who improved on only one or neither vaginal and/or vulvar symptoms were deemed “non-responders”. For these patients, HLA administration was increased to 5 times per week for the remaining 12 weeks of the study. If participants showed improvement only in one area (i.e., vagina or vulva), the application frequency of 3 times per week was continued for the improved area and increased to 5 times per week for the unaffected/worsened area (Figure 1).

Study Measures

PROs and vulvovaginal symptom outcomes were assessed at baseline, 4-6 weeks, 12-14 weeks, and 22-24 weeks (Figure 1). Objective vaginal symptoms (vaginal pH and degree of epithelial atrophy) and vulvar symptoms (vulvar atrophy and/or vulvar/vestibular irritation) on clinical gynecologic exam and subjective vaginal symptoms (VAS) and vulvar symptoms (VuAS) were monitored and recorded (baseline to 24 weeks). The VAS and VuAS measures [14] have been validated in a female cancer patient sample (including gynecologic cancer survivors) and were the primary efficacy outcome measures, and change in scores from baseline to T3 (12-14 weeks) was the primary efficacy endpoint. These instruments measure patients’ perceptions of their vulvovaginal tissue quality. The VAS assesses vaginal symptoms of dryness, soreness, irritation, and dyspareunia. The VuAS evaluates vulvar symptoms of dryness, soreness, irritation, and external pain post-stimulation. Symptoms are graded on a 4-point scale (0=none; 1 =mild; 2=moderate; 3=severe) and are averaged to create VAS and VuAS composite scores. Higher scores indicate more symptoms.

PRO Measures:

Sexual function was measured by the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), the Sexual Activity Questionnaire (SAQ), and PROMIS sexual function items (PROMIS-SxF). The FSFI is a 19-item self-report measure of female sexual function [15] that has been validated for use in female cancer survivors (including gynecologic cancer) [16]. Higher FSFI scores indicate better functioning, with a total score <26.0 indicating sexual dysfunction [16]. The SAQ is a 14-item screening tool used to assess whether women are sexually active, to evaluate sexual function, and to identify reasons for any reported inactivity [17, 18]. The PROMIS-SxF items address sexual interest, pain, orgasm, lubrication, and subjective arousal [19–24]. Thirteen items from the PROMIS-SxF measure were selected for our study. Menopausal symptoms were assessed by the Menopausal Symptom Checklist (MSCL), a 36-item questionnaire querying a range of physical and psychological symptoms associated with estrogen deprivation, with higher scores indicating bothersome menopausal symptoms [25–27]. Participants also were asked one question regarding time in menopause on the baseline questionnaire.

Clinical Gynecologic Exam Outcomes:

Vaginal pH was coded into clinically meaningful categories (<5, 5-6.5, >6.5). Normal vaginal pH is less than 5. Higher vaginal pH indicates greater vaginal atrophy. Four additional indicators of vaginal health were assessed (epithelial integrity, thickness, vaginal secretions, and vascularity) and rated on a 4-point scale (0, 1, 2, 3). These ratings were summed and rescaled to range from 0 to 100 to create a vaginal exam composite index, with higher scores indicating greater degrees of vaginal symptoms. Vulvar and vestibular health was assessed by examination (for vulvar atrophy and/or vulvar/vestibular irritation). Vulvar atrophy and vulvar irritation are both rated on a 4-point scale (0, 1, 2, 3). A score of 0 indicates normal vulvar characteristics or no presence of symptoms. A rating of 1 indicates some concern for symptoms or presence of vestibular irritation, and a rating of 3 indicates severe symptoms. These ratings were summed and rescaled to range from 0 to 100 to create a vulvar exam composite index. Higher scores indicate greater degrees of symptoms.

Statistical Analysis Methods

Demographic/medical characteristics and categorical endpoints were summarized using descriptive statistics (e.g., means and standard deviations for continuous variables, frequencies and percentages for categorical variables). For continuous endpoints, linear mixed models (LMMs) controlling for assessment time, months since treatment completion, and age were used to estimate the adjusted means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) at each assessment time. LMM-based contrasts were used to test for statistically significant changes in the adjusted means from baseline to each follow-up assessment, as well as between the T3 and T4 assessments. For categorical endpoints, McNemar’s tests were used to test for significant changes between pairs of time points. Significance tests with a p<.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted in R version 3.6.1 [28].

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

The mean age of the 43 patients on study was 59 years (range, 38-78 years). Fifty-four percent (23/43) were partnered, 33% (14/43) were single, and 14% (6/43) were either widowed or divorced at the time of study enrollment. Participants self-identified as White (77%, 33/43), Black (5%, 2/43), Asian (5%, 2/43), or “other”/declined to respond (14%, 6/43). Mean time from completion of radiation therapy to study enrollment was 17.2 months (range, 2-57 months). Additionally, 67% (29/43) underwent chemotherapy and completed treatment an average 14.8 months (range, 3-58 months) prior to enrollment. Time in menopause ranged from 11 to 340 months; 5% (2/43) were in menopause for less than 1 year, 33% (14/43) from 1 to 5 years, and 63% (27/43) for more than 5 years. Forty-nine percent (21/43) reported being sexually active, and 41% (16/39) felt confident about future sexual activity at study enrollment.

Intervention Sample

Forty-six women enrolled on the study and completed the baseline assessment. Three eligible participants withdrew for reasons unrelated to the study product or design, leaving 43 evaluable patients for treatment initiation. Thirty-four participants completed the T2 assessment, 33 completed the T3 assessment, and 27 completed the T4 assessment. Of the 43 initial participants, 10 withdrew from the study before completing the T3 assessment for reasons related to the study product or design (i.e., lost to follow-up, noncompliant with dosing schedule, urinary tract infection, irritation/discharge, etc.). These participants were evaluable for the primary objective (feasibility) but not evaluable for the secondary objective (effectiveness), which required completion of the T3 assessment. An additional 6 participants withdrew before completing the T4 assessment.

Sexual functioning and Menopausal Outcomes

Estimates of means and 95% CIs for each continuous endpoint were calculated at each of the 4 assessment time points using LMMs adjusted for assessment time, months since treatment completion, and age. Similar patterns of improvement were seen for most endpoints at each follow-up relative to baseline, including sexual function as measured by the PROMIS-Sxf and SAQ scales, and menopausal symptoms as measured by the MSCL. PROMIS-Sxf vaginal discomfort scale and SAQ discomfort scale scores significantly improved from baseline to all time points (all p<001). Additionally, PROMIS-SxF scores for interest in sexual activity, labial discomfort, and clitoral discomfort all showed significant improvement from baseline to T4 (all p<01). Regarding menopausal symptoms, both MSCL scores (total score and number of symptoms) improved significantly from baseline to T2, T3, and T4 (all p<.001). FSFI mean scores at each time point are shown in Table 1. Mean domain scores in order of highest to lowest functioning at baseline were as follows: desire, 2.61; satisfaction, 2.59; orgasm, 1.76; arousal, 1.72; pain, 1.5; and lubrication, 1.41. The lowest functioning domain, lubrication, showed significant improvement at T2 and again at T4 relative to baseline (both p<.03) (Table 1). Other FSFI sexual function scores generally showed improvement at T4 relative to baseline, although the satisfaction and pain subscales did not show significant improvement (Table 1).

Table 1.

Adjusted Means (95% Confidence Interval) of Female Sexual Function Index Outcomes over Time

| Total Score | Desire | Arousal | Lubrication | Orgasm | Satisfaction | Pain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean* 95% CI P value** |

Mean* 95% CI P value** |

Mean* 95% CI P value** |

Mean* 95% CI P value** |

Mean* 95% CI P value** |

Mean* 95% CI P value** |

Mean* 95% CI P value** |

|

| BL | 11.43 (8.71, 14.14) |

2.61 (2.25, 2.97) |

1.72 (1.14, 2.3) |

1.41 (0.85, 1.96) |

1.76 (1.11, 2.4) |

2.59 (2.06, 3.12) |

1.5 (0.87, 2.13) |

| T2 | 13.71 (10.8, 16.57) 0.0424 |

2.92 (2.53, 3.31) 0.1012 |

2.32 (1.71, 2.94) 0.0226 |

2 (1.41, 2.6) 0.0215 |

2.4 (1.72, 3.09) 0.0297 |

2.8 6 (2.3, 3.42) 0.3083 |

1.49 (0.83, 2.16) 0.9825 |

| T3 | 13.51 (10.6, 16.43) 0.0714 |

2.85 (2.45, 3.25) 0.2133 |

2.32 (1.7, 2.95) 0.0249 |

1.72 (1.12, 2.32) 0.2251 |

2.22 (1.52, 2.91) 0.1263 |

3.0 2 (2.44, 3.59) 0.1265 |

1.74 (1.06, 2.42) 0.4336 |

| T4 | 14.14 (11.11, 17.17) 0.0283 |

3.2 (2.78, 3.63) 0.0048 |

2.2 8 (1.63, 2.93) 0.0488 |

2.1 (1.47, 2.73) 0.0139 |

2.39 (1.67, 3.12) 0.0475 |

2.49 (1.87, 3.11) 0.7443 |

2.01 (1.3, 2.72) 0.1177 |

Means are from linear mixed models adjusting for time point, months since treatment completion, and age. The endpoint marginal means were calculated from these models for each time point holding the other variables constant at their sample means.

P values are from tests of differences between the baseline mean and each of the follow-up means.

CI, Confidence Interval; BL, Baseline; T2, Timepoint 2; T3, Timepoint 3; T4, Timepoint 4; FSFI, Female Sexual Function Index

Vulvovaginal Health Outcomes

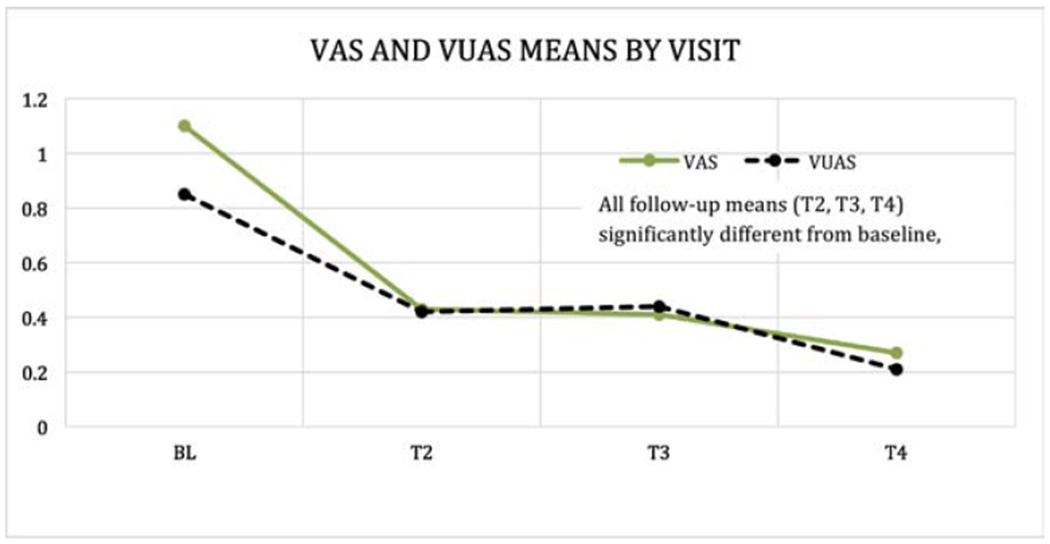

Estimated means and 95% CIs (adjusted for assessment time, months since treatment completion, and age) were also calculated for VAS and VuAS total scores at each of the 4 assessment points. Compared to baseline, both measures were significantly better (lower) at each of the 3 follow-up assessments (VAS, all p<.001; VuAS, all p≤002, Figure 2). The mean difference in VAS composite at T3 versus baseline, controlling for age and months since treatment, was −0.69 (95% CI, −0.87 - 0.50), and the corresponding difference in VuAS composite was −0.41 (95% CI, −0.63 - 0.20). The vulvar composite score consisting of vulvar atrophy and/or vulvar/vestibular irritation summed to create a composite index also improved at each follow-up assessment compared to baseline (T2, p=0.01; T3, p=0.007; T4, p=0.03).

Figure 2.

Vaginal Assessment Scale (VAS) and Vulvar Assessment Scale (VuAS) means by visit

Table 2 demonstrates the changes of vaginal and vulvar symptoms at each time point according to patient-reported and pelvic exam measures. At baseline, patient-reported perception of mild to severe dryness was more common for the vagina (VAS1; 100%, 43/43) than for the vulva (VuAS1; 77%, 33/43). Patient-reported mild to severe pain was higher with insertion (VAS4; 100%, 25/25) than with external touch (VuAS4; 36%, 12/33). Both measures substantially improved from baseline to T2, T3, and T4. Reported mild to severe vaginal dryness dropped to 56% (19/34) at T2, 45.5% (15/33) at T3, and 18.5% (5/27) at T4; mild to severe vulvar dryness dropped to 59% (20/34) at T2, 45.5% (15/33) at T3, and 30% (8/27) at T4. At T4, reports of mild to severe pain with insertion decreased to 64% (7/11) and reports of mild to severe pain with external touch decreased to 14% (3/21) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in Vulvovaginal Health Outcomes over Time

| Vaginal Dryness (VAS1) | Vaginal Dryness (VuAS1) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| BL | 0 (0%) | 15 (35%) | 11 (26%) | 17 (39%) | 10 (23%) | 12 (28%) | 10 (23%) | 11 (26%) |

| T2 | 15 (44%) | 14 (41%) | 4 (12%) | 1 (3%) | 14 (41%) | 12 (35%) | 6 (18%) | 2 (6%) |

| T3 | 18 (55%) | 12 (36%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 18 (55%) | 8 (24%) | 5 (15%) | 2 (6%) |

| T4 | 22 (81%) | 1 (4%) | 2 (7%) | 2 (7%) | 19 (70%) | 3 (11%) | 5 (19%) | 0 (0%) |

| Vaginal Irritation (VAS3) | Vulvar Irritation (VuAS3) | |||||||

| None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| BL | 33 (77%) | 8 (19%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 20 (47%) | 12 (28%) | 8 (19%) | 3 (7%) |

| T2 | 30 (88%) | 4 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 25 (74%) | 8 (23%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| T3 | 25 (76%) | 7 (21%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 18 (55%) | 12 (36%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (3%) |

| T4 | 25 (93%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 24 (89%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Dyspareunia (VAS4) | Painful to Touch (VuAS4) | |||||||

| None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| BL | 0 (0%) | 4 (16%) | 14 (56%) | 7 (28%) | 21 (64%) | 6 (18%) | 4 (12%) | 2 (6%) |

| T2 | 4 (31%) | 4 (31%) | 2 (15%) | 3 (23%) | 20 (87%) | 1 (4%) | 2 (9%) | 0 (0%) |

| T3 | 5 (38%) | 3 (23%) 2 (15%) | 3 (23%) 2 (15%) | 2 (15%) | 21 (91%) | 2 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| T4 | 4 (36%) | 3 (27%) | 3 (27%) | 1 (9%) | 18 (86%) | 3 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Vaginal Irritation (on exam) | Vulvar Irritation (on exam) | |||||||

| None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| BL | 28 (80%) | 5 (14%) | 2 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 23 (55%) | 12 (28%) | 5 (12%) | 2 (5%) |

| T2 | 22 (79%) | 6 (21%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 22 (65%) | 10 (29%) | 2 (6%) | 0 (0%) |

| T3 | 25 (89%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 24 (73%) | 7 (21%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) |

| T4 | 22 (92%) | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (78%) | 5 (18%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Vaginal pH (on exam) | Vulvar Atrophy (on exam) | |||||||

| <5 | 5-6.5 | >6.5 | None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| BL | 4 (9%) | 26 (61%) | 13 (30%) | 17 (39%) | 19 (44%) | 5 (12%) | 2 (5%) | |

| T2 | 3 (9%) | 16 (47%) | 15 (44%) | 20 (59%) | 13 (38%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| T3 | 9 (27%) | 19 (58%) | 9 (27%) | 19 (58%) | 13 (39%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| T4 | 4 (15%) | 17 (65%) | 5 (19%) | 12 (44%) | 13 (48%) | 2 (7%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Vaginal Stenosis (on exam) | Vestibular Irritation (on exam) | |||||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |||||

| BL | 31 (94%) | 2 (6%) | 27 (63%) | 16 (37%) | ||||

| T2 | 26 (93%) | 2 (7%) | 21 (64%) | 12 (36%) | ||||

| T3 | 25 (89%) | 3 (11%) | 24 (73%) | 9 (27%) | ||||

| T4 | 19 (83%) | 4 (17%) | 20 (74%) | 7 (26%) | ||||

BL, Baseline; T2, Timepoint 2; T3, Timepoint 3; T4, Timepoint 4; VAS, Vaginal Assessment Scale; VuAS, Vulvar Assessment Scale

In contrast, patient-reported irritation at baseline was more common for the vulva (VuAS3; 53%, 23/43) than for the vagina (VAS3; 23%, 10/43). At T4, patient-reported mild to severe irritation decreased to 11% (3/27) for the vulva and 7% (2/27) for the vagina (Table 2). Irritation on baseline pelvic exam was also more common for the vulva (45%, 19/42) than for the vagina (20%, 7/35). Vulvar irritation rates declined to 35% (12/34) at T2, 27% (9/33) at T3, and 22% (6/27) at T4. Vaginal irritation rates also decreased to 21% (6/28) at T2, 11% (3/28) at T3, and 8% (2/24) at T4. Other clinical exam outcomes, such as vestibular irritation, vulvar atrophy, and pH also improved over the study period. Among patients with both baseline and T4 assessments, the prevalence of vestibular irritation decreased from approximately 33% (9/27) at baseline to 26% (7/27) at T4 (p=.48). The rate of vulvar atrophy on clinical exam significantly improved from 60% (26/43) at baseline to 41% (14/34) at T2 (p=.02). Among patients with both baseline and T4 assessments, severe vaginal pH (>6.5) decreased from approximately 23% (6/26) at baseline to 19% (5/26) at T4 (p=.71). However, the prevalence of vaginal stenosis on exam increased from 6% (2/33) at baseline to 17% (4/23) at T4 (Table 2).

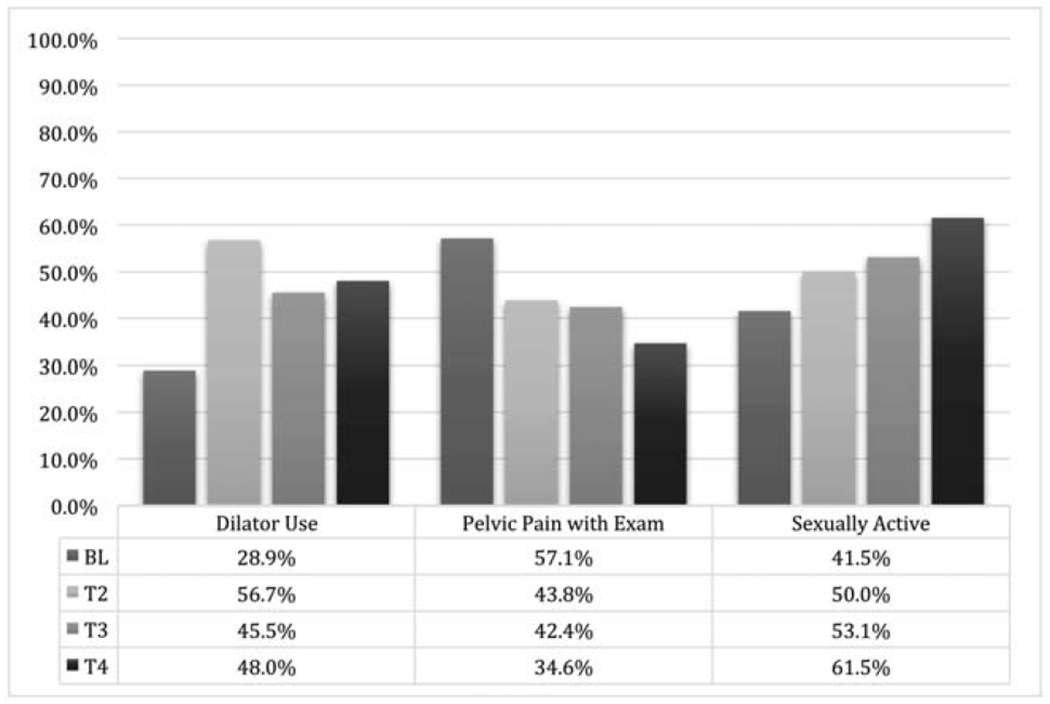

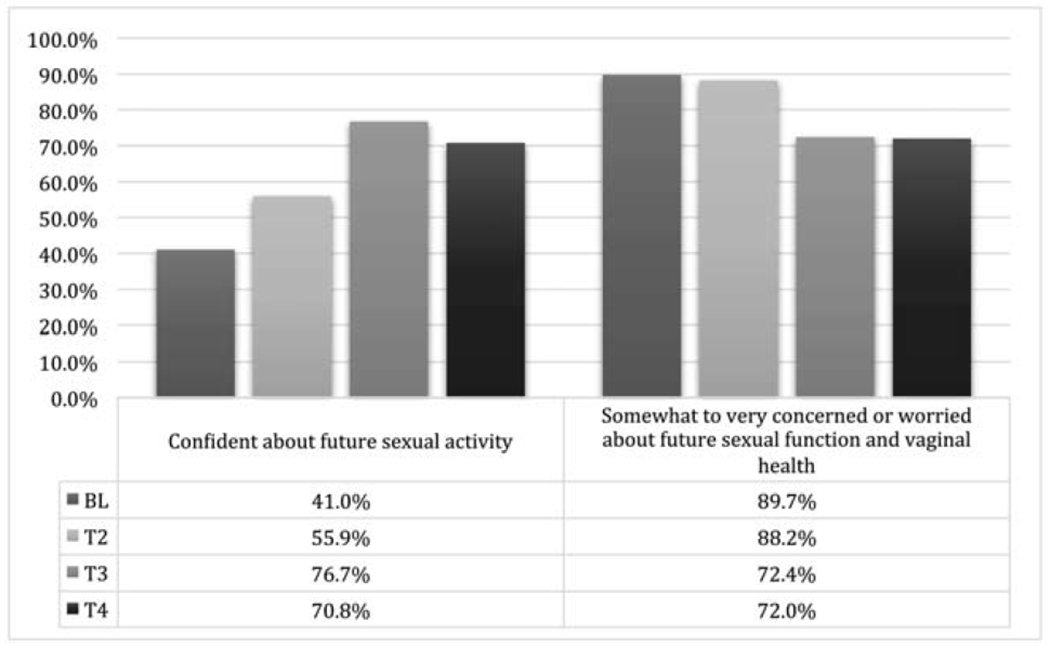

Rates of Health-Promotion Strategies, Sexual Activity, and Future Confidence

Health-promotion strategies reported at baseline included vaginal lubricants with sexual activity (88%, 38/43), dilator therapy (29%, 11/38), application of internal vaginal moisturizers (26%, 11/42) and external moisturizers (12%, 5/41), and pelvic floor exercises (9.5%, 4/42). Participant compliance generally improved over the course of the study (Supplemental Figure 1). Dilator therapy usage increased from 29% (11/38) at baseline to 57% (17/30) at T2, 45.5% (15/33) at T3, and 48% (12/25) at T4. The use of a dilator size >3 increased from 78% (21/27) at baseline to 90% (18/20) at T2, 88% (23/26) at T3, and 100% (21/21) at T4. Figure 3 presents dilator therapy compliance with rates of sexual activity (as reported on the FSFI) and pain with exam. Sexual activity rates increased from 41% (17/41) at baseline to 50% (17/34) at T2, 53% (17/32) at T3, and 61.5% (16/26) at T4 (Figure 3). Pelvic pain with exam frequency decreased from 57% (24/42) at baseline to 44% (14/32) at T2, 42% (14/33) at T3, and 35% (9/26) at T4. The rate of confidence about future sexual activity increased from 41% (16/39) at baseline to 71% (17/24) at T4. The rate of concerns about future sexual function and vaginal health also decreased from 90% (35/39) at baseline to 72% at T4 (18/25) (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Dilator therapy, pelvic pain with exam, and sexual activity over time

Figure 4.

Patient-reported confidence and concern over time

Five of the 7 participants presenting with vaginal stenosis over the course of the study had previously undergone brachytherapy. All 7 had also received chemotherapy. Of the 4 patients with persistent stenosis at T4, rare or absent dilator use was noted.

Feasibility

The study was deemed feasible based on the retention rates for the 12-week HLA-based treatment regimen (baseline through T3). Retention rates were 79% at T2, 77% at T3, and 63% at T4. Of those who completed the T3 assessment (12-14 weeks), 94% (31/33) answered most or all items on a questionnaire about overall symptom improvement. The study questionnaire contained items to assess whether participants felt their vaginal and vulvar symptoms had improved on study and whether improvement was due to the HLA-based product. Sixty-eight percent (21/31) indicated improvement in vaginal symptoms, with 26% (8/31) reporting a partial benefit. Results were comparable for vulvar symptoms, with 70% improvement (14/20) or partial benefit (25%, 5/20). Ninety-seven percent of all patients (30/31) with vaginal symptoms and 100% of all patients (20/20) with vulvar symptoms attributed symptom improvement to the HLA-based treatment or felt the treatment was partly responsible for symptom relief.

Satisfaction

Satisfaction was evaluated by participants’ expectations for the product, ease of use, and helpfulness in addressing tissue quality issues. Of those who completed the final assessment (T4), 96% (26/27) responded to the satisfaction items. Eighty-five percent (22/26) felt the HLA-based product moderately to extremely met their expectations. Participants found the product easy (quite to extremely) to use both in the vagina (77%, 20/26) and on the vulva (89%, 17/19), and viewed it to be helpful (somewhat to very) for vaginal tissue (96%, 25/26) and vulvar tissue (100%, 19/19) quality. By study completion, 85% (22/26) of vaginal symptoms and 84% (16/19) of vulvar symptoms had resolved (somewhat to very). Ninety-two percent (24/26) stated they would recommend the HLA-based product to other female cancer survivors. Within our cohort, 54% (14/26) of patients indicated they had never used a moisturizer in their vagina and 89% (17/19) indicated they had never used a moisturizer on their vulva. Of those who had tried a vaginal moisturizer, 75% (9/12) felt the HLA-based product was more helpful.

DISCUSSION

Sexual dysfunction is prevalent among endometrial cancer survivors [5]. Previous studies have shown that women treated with pelvic radiation have the highest risk for developing vaginal fibrosis, which leads to impairments in sexual health [29]. Hofsjo et al. suggests that topical vaginal treatments may help to preserve a functional vaginal wall if used in combination with other health-promotion strategies such as dilators [29]. Our study showed significant improvements in perceived vaginal (VAS) and vulvar (VuAS) symptoms, as well as less bothersome menopausal symptoms and enhanced sexual function, were seen with consistent use of this non-hormonal, HLA-based moisturizer. In our cohort, the FSFI total score significantly improved over the course of the study; however, it remained significantly lower (14.14) than the clinical cutoff score of <26 at study completion. These findings are consistent with the literature and highlight the need for further sexual health interventions, including interventions at earlier time points and even prevention.

In our study, we observed patient-reported and pelvic exam differences between vaginal and vulvar symptoms. At baseline, the rate of dryness was higher in the vagina (100%) than on the vulva (77%); conversely, the rate of irritation was higher for the vulva (53%) than for the vagina (23%). On pelvic exam, the presence of irritation at baseline was also more common for the vulva (45%) than the vagina (20%). Interventions that address both types of symptoms are important for improving women’s health and sexual function. The simple strategy of applying moisturizer both internally and externally clinically improved vaginal and vulvar tissue quality on gynecologic exam by decreasing vaginal and vestibular irritation as well as vulvar irritation and atrophy. Although vaginal pH did not statistically improve from baseline, there was a decrease in severely elevated pH (6.5 of greater) with consistent non-hormonal moisturizer use. Study participants expressed increased confidence about future sexual activity using these simple non-hormonal strategies.

Seventy-six percent of the patients were vaginal non-responders at T3 (no change or worsening), and vaginal moisturizer application was increased to 5 times per week for these patients. Only participants who showed improvement on both the VAS score and vaginal pH at the 12-week assessment point could be considered “responders”. Of note, our study criteria were strict in that improvement in both PROs and pelvic exam were required to designate a participant as a responder. We now recognize that stabilization of symptoms could have been viewed as a positive response. However, our concern was to not undertreat any of the participants. Women adhering to a higher frequency of moisturizer application also continued to show improvement in their symptoms. Increased vulvovaginal tissue quality and comfort contributed to increased compliance with other sexual health-promotion strategies in our cohort. Previous studies have suggested that vulvovaginal health-promotion strategies play an important role in this population [5, 30]. Recommendations to use the moisturizer as per study protocol were given at each time point, and standardized education to use (start, continue, or increase) other health-promotion strategies such as lubricant use, dilator therapy, or pelvic floor exercises in the post-RT setting, was provided. The use of vaginal dilators generally increased over the course of the study, as did dilator size. Women who use regular moisturizers still need to comply with dilator recommendations, as it is of clinical importance in the post-RT setting. A recent study found that consistent dilator use may be protective against symptomatic vaginal stenosis in women receiving vaginal brachytherapy for gynecologic cancer treatment [30]. The majority of study participants received IVRT (79%) over EBRT (21%), reflecting common practice patterns in treating early-stage endometrial cancer. Given the high level of effectiveness of brachytherapy in the gynecologic cancer patient population, early educational interventions could lead to decreased side effects following treatment [30]. It is important to note that not only did participants report an overall increase in sexual activity (as per the FSFI), but they also experienced decreased pelvic pain with exam. Although the importance of sexual activity may vary for women, gynecologic exams are a critical part of surveillance for possible cancer recurrence, and comfort can foster compliance.

We acknowledge the limitations of this study. This study lacked a controlled arm or comparison group. Our intervention was implemented within a female sexual medicine program, with the goal to address the symptoms of our patients. This intervention was offered as a treatment option. However, we feel these results can be easily used to aid other female cancer patients and survivors who have vulvovaginal health concerns. When we started developing the study, the importance of vulvar health became apparent based on participant feedback and clinical exam outcomes. In order to study this scientifically, we added an objective to address vulvar health independently, and this contributed to the uneven numbers between the vaginal and vulvar outcomes. Nevertheless, we were able to accrue additional participants for adequate statistical power.

In addition, in order to have adequate statistical power to assess the efficacy of the HLA treatment, we were unable to further divide our sample into multiple groups based on time in menopause, time since completion of therapy, and other factors. We did, however, control for time since completion of therapy and age in our linear mixed models of our efficacy endpoints over time. With respect to increased attrition over time, our primary inferential analysis method, linear mixed models, is unbiased in the presence of missing data due to attrition under the missing at random (MAR) assumption. All patients who had at least the baseline endpoint measurement were included in these models. We assessed whether the MAR assumption was reasonable by comparing baseline characteristics of patients lost to follow-up versus those completing the study and found no significant differences.

Conclusions

Endometrial cancer patients and survivors experience significant sexual/vulvovaginal health concerns. Our study demonstrates how a non-hormonal, HLA-based moisturizing gel applied intravaginally and topically to the vulva can improve vulvovaginal tissue quality in self-perceived symptoms and on clinical exams. Improvement in these symptoms translated into improved comfort with exams, increased dilator usage, and enhanced sexual function. Based on our findings, female cancer survivors should moisturize at a higher frequency (3-5 times per week) than recommended for general menopause (1-2 times per week) for adequate symptom relief and confirmed the findings of our FSMP evaluation study [31]. Future studies may want to examine the benefits of aggressive vulvovaginal moisturizing (3-5x per week) in combination with other non-hormonal strategies to address unresolved sexual health concerns such as intravaginal DHEA [32, 33] for vulvovaginal dryness and topical lidocaine for persistent insertional dyspareunia [34].

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the use of HLA on vulvar tissue quality. Our findings demonstrated the vulvar health benefits of the hydrating moisturizer on both PROs and pelvic exam outcomes. Participants were highly satisfied with the product in improving vulvovaginal symptoms, found it easy to use, and would recommend it to others.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

To evaluate the efficacy of HLA vaginal gel in improving vulvovaginal symptoms in endometrial cancer survivors.

HLA vaginal moisturizing gel applied intravaginally and topically to the vulva improved vulvovaginal health.

HLA needs to be used at a higher frequency (3-5x/week) than recommended for general menopause (1-2x/week).

Improvements in vulvovaginal tissue quality enhanced sexual function and confidence and reduced menopausal symptoms.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Fidia Pharmaceuticals supported the scientific aims of this clinical trial through donation of product (Hydeal-D©) and a small research grant to MSK to cover the time and effort of an MSK statistician, research assistant, and pharmacy staff member for product distribution. This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement: Outside the submitted work, Dr. Jewell reports personal fees from Covidien/Medtronic. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- [1].Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH. Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: Prevalence Trajectories and Comorbidity Burden among Older Cancer Survivors in the United States. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2016;25:1029–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2019;69:7–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].National Cancer Institute: Surveillance EaERP. SEER Cancer Statistics Review (CSR) 1975–2016. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Biglia N, Cozzarella M, Cacciari F, Ponzone R, Roagna R, Maggiorotto F, et al. Menopause after breast cancer: a survey on breast cancer survivors. Maturitas. 2003;45:29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Damast S, Alektiar KM, Goldfarb S, Eaton A, Patil S, Mosenkins J, et al. Sexual functioning among endometrial cancer patients treated with adjuvent high-dose-rate intra-vaginal radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84(4):e187–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ganz PA, Greendale GA, Kahn B, O’Leary JF, Desmond KA. Are older breast carcinoma survivors willing to take hormone replacement therapy? Cancer. 1999;86:814–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chen J, Geng L, Song X, Li H, Giordan N, Liao Q. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of hyaluronic acid vaginal gel to ease vaginal dryness: a multicenter, randomized, controlled, open-label, parallel-group, clinical trial. The journal of sexual medicine. 2013;10:1575–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Costantino D, Guaraldi C. Effectiveness and safety of vaginal suppositories for the treatment of the vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: an open, non-controlled clinical trial. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences. 2008;12:411–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ekin M, Yasar L, Savan K, Temur M, Uhri M, Gencer I, et al. The comparison of hyaluronic acid vaginal tablets with estradiol vaginal tablets in the treatment of atrophic vaginitis: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics. 2011;283:539–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jokar A, Davari T, Asadi N, Ahmadi F, Foruhari S. Comparison of the Hyaluronic Acid Vaginal Cream and Conjugated Estrogen Used in Treatment of Vaginal Atrophy of Menopause Women: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. International journal of community based nursing and midwifery. 2016;4:69–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Markowska J, Madry R, Markowska A. The effect of hyaluronic acid (Cicatridine) on healing and regeneration of the uterine cervix and vagina and vulvar dystrophy therapy. European journal of gynaecological oncology. 2011. ;32:65–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tea MKM, Priemer V, Kubista E. Wirksamkeit und Sicherheit von Hyaluron-Saure-Zapfchen (Cikatridina(R)) beider Behandlung hormon-oder chemotherapieinduzierter vaginalerAtrophie bei Mammakarzinompatientinnen. Fertilität und Reproduktion 2006;16:17–9. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Laliscia C, Delishaj D, Fabrini MG, Gonnelli A, Morganti R, Perrone F, et al. Acute and late vaginal toxicity after adjuvant high-dose-rate vaginal brachytherapy in patients with intermediate risk endometrial cancer: is local therapy with hyaluronic acid of clinical benefit? Journal of Contemporary Brachytherapy. 2016;8:512–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Eaton AA, Baser RE, Seidel B, Stabile C, Canty JP, Goldfrank DJ, et al. Validation of Clinical Tools for Vaginal and Vulvar Symptom Assessment in Cancer Patients and Survivors. The journal of sexual medicine. 2017;14:144–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of sex & marital therapy. 2000;26:191–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Baser RE, Li Y, Carter J. Psychometric validation of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) in cancer survivors. Cancer. 2012;118:4606–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Thirlaway K, Fallowfield L, Cuzick J. The Sexual Activity Questionnaire: a measure of women’s sexual functioning. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 1996;5:81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Vistad I, Fossa SD, Kristensen GB, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. The sexual activity questionnaire: pychometric properties and normative data in a norwegian population sample. Journal of women’s health (2002). 2007;16:139–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].DeWalt DA, Rothrock N, Yount S, Stone AA. Evaluation of item candidates: the PROMIS qualitative item review. Medical care. 2007;45:S12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Flynn KE, Jeffery DD, Keefe FJ, Porter LS, Shelby RA, Fawzy MR, et al. Sexual functioning along the cancer continuum: focus group results from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS(R)). Psycho-oncology. 2011;20:378–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Flynn KE, Reeve BB. Progress on the PROMIS (R) Sexual Function Measure Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2010;19:98–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Fortune-Greeley AK, Flynn KE, Jeffery DD, Williams MS, Keefe FJ, Reeve BB, et al. Using cognitive interviews to evaluate items for measuring sexual functioning across cancer populations: improvements and remaining challenges. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2009;18:1085–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Jeffery DD, Tzeng JP, Keefe FJ, Porter LS, Hahn EA, Flynn KE, et al. Initial report of the cancer Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) sexual function committee: review of sexual function measures and domains used in oncology. Cancer. 2009;115:1142–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Cook KF, Crane PK, Teresi JA, et al. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Medical care. 2007;45:S22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Land SR, Wickerham DL, Costantino JP, Ritter MW, Vogel VG, Lee M, et al. Patient-reported symptoms and quality of life during treatment with tamoxifen or raloxifene for breast cancer prevention: the NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial. JAMA. 2006; 295(23):2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Day R, Ganz PA, Costantino JP, Cronin WM, Wickerham DL, Fisher B. Health-related quality of life and tamoxifen in breast cancer prevention: a report from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2659–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Robson M, Hensley M, Barakat R, Brown C, Chi D, Poynor E, et al. Quality of life in women at risk for ovarian cancer who have undergone risk-reducing oophorectomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89:281–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Team RC. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: The R Foundation; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hofsjö A, Bohm-Starke N, Blomgren B, Jahren H, Steineck G, Bergmark K. Radiotherapy-induced vaginal fibrosis in cervical cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2017;56:661–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Park HS, Ratner ES, Lucarelli L, Polizzi S, Higgins SA, Damast S. Predictors of vaginal stenosis after intravaginal high-dose-rate brachytherapy for endometrial carcinoma. Brachytherapy. 2015;14:464–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Carter J, Stabile C, Seidel B, Baser RE, Goldfarb S, Goldfrank DJ. Vaginal and sexual health treatment strategies within a female sexual medicine program for cancer patients and survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11:274–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Barton DL, Sloan JA, Shuster LT, Gill P, Griffin P, Flynn K, et al. Evaluating the efficacy of vaginal dehydroepiandosterone for vaginal symptoms in postmenopausal cancer survivors: NCCTG N10C1 (Alliance). Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:643–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Barton DL, Shuster LT, Dockter T, Atherton PJ, Thielen J, Birrell SN, et al. Systemic and local effects of vaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA): NCCTG N10C1 (Alliance). Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:1335–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Goetsch MF, Lim JY, Caughey AB. A practical solution for dyspareunia in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(30):3394–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.