Abstract

Objective

Falls are a leading cause of injury-related emergency department (ED) visits and may serve as a sentinel event for older adults, leading to physical and psychological injury. Our primary objective was to characterize patient- and caregiver-specific perspectives about care transitions after a fall.

Methods

Using a semistructured interview guide, we conducted in-depth, qualitative interviews using grounded theory methodology. We included patients enrolled in the Geriatric Acute and Post-acute Fall Prevention Intervention (GAPcare) trial aged 65 years and older who had an ED visit for a fall and their caregivers. Patients with cognitive impairment (CI) were interviewed in patient–caregiver dyads. Domains assessed included the postfall recovery period, the skilled nursing facility (SNF) placement decision-making process, and the ease of obtaining outpatient follow-up. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and coded and analyzed for a priori and emergent themes.

Results

A total of 22 interviews were completed with 10 patients, eight caregivers, and four patient–caregiver dyads within the 6-month period after initial ED visits. Patients were on average 83 years old, nine of 14 were female, and two of 14 had CI. Six of 12 caregivers were interviewed in reference to a patient with CI. We identified four overarching themes: 1) the fall as a trigger for psychological and physiological change, 2) SNF placement decision-making process, 3) direct effect of fall on caregivers, and 4) barriers to receipt of recommended follow-up.

Conclusions

Older adults presenting to the ED after a fall report physical limitations and a prominent fear of falling after their injury. Caregivers play a vital role in securing the home environment; the SNF placement decision-making process; and navigating the transition of care between the ED, SNF, and outpatient visits after a fall. Clinicians should anticipate and address feelings of isolation, changes in mobility, and fear of falling in older adults seeking ED care after a fall.

Falls are the leading cause of fatal and nonfatal injuries among older adults over age 65.1 About 30% of older adults fall every year, often resulting in serious injuries, loss of function, and fear of falling again.1–4 Estimated at $31.3 billion, the annual Medicare costs for older adult falls is expected to increase given the aging population.5,6 Aside from the high associated morbidity and cost, falls serve as a sentinel event in predicting future functional decline, emergency department (ED) recidivism, and mortality.7 Within 6 months of a fall-related ED visit, 22.6% of older adults have at least one recurrent fall, 42.6% revisit the ED, and 2.6% died.8 Furthermore, the risk of admission to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) increases with injurious and noninjurious falls. Indeed, fall-related injuries account for up to one-third of SNF admissions.9

The Society for Academic Emergency Medicine has specified “falls” as one of four high-yield research opportunities.10 Despite an increasing focus on fall detection using sensor technology,11 there is limited emergency medicine research on falls and little is known about the difficulties older adults and their caregivers face during recovery following a fall-related ED visit.7 This research addresses this question. We asked patients and caregivers to describe the lived experience of the ED visit, how they made decisions about their postinjury health care needs (e.g., whether to go to a SNF, what to change about their home environment), and what barriers they encountered accessing care in follow-up. We aimed to elucidate the physical and psychological trajectory after an ED visit for a fall, elucidate patient- and caregiver-specific perspectives in determining the appropriate living setting for older adults after a fall, and identify barriers to receiving necessary health care after the event. Understanding the unique experiences of patients after a fall could allow emergency medicine clinicians to provide more patient-centric care and anticipatory guidance to patients and caregivers after this sentinel event.

METHODS

Study Design

In this qualitative study, we used grounded theory methodology12 and included participants who were a part of the Geriatric Acute and Post-acute Fall Prevention Intervention (GAPcare) study. The GAPcare study aimed to examine the feasibility and acceptability of the GAPcare intervention to determine if ED-based pharmacy and physical therapy (PT) consultations reduced subsequent falls and health care utilization.13 The trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03360305). In this study, we analyzed data from semistructured interviews of patients and/or their caregivers to assess their experiences after a fall-related ED visit. We also evaluated the transition of care after the ED visit including the decision to consider/not consider SNF placement for the care recipient. The qualitative research methods used in this study provided an open-ended inquiry to focus on discovery and interpretation, allowing investigators to understand patient and caregiver experiences of their care after an ED-related fall visit. The hospital institutional review board approved the study. Study methods and results are presented according to the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ).14

Study Setting and Population

Recruitment for GAPcare occurred at two different EDs: an academic community hospital and a Level I trauma center and tertiary referral ED within the same health system. Patients 65 years and older were eligible to participate in the main study if they presented to the ED within 7 days of a fall, if they primarily spoke English or Spanish, and if their ED clinician determined they were likely to be discharged from the ED (i.e., not admitted). As they represent an important understudied subgroup of people who experience falls, patients with cognitive impairment (CI) were eligible for participation. The cognitive status of the patient was assessed using the validated Six-Item Screener.15 A score of <4 on the 6-point questionnaire indicated high risk for CI. If a patient identified with CI remained interested in participating in the study, a legally authorized representative was asked to provide written consent. Individuals who were altered (e.g., intoxicated), undomiciled, living in a SNF, or could not provide a phone number for follow-up were excluded. After providing written consent, participants were randomized to the usual care (UC) or intervention (INT) arm. Participants in the UC arm received routine care as directed by the ED clinicians. Participants in the INT arm received the pharmacy and PT GAPcare consultations.

Following the ED visits, participants from both study arms were contacted over the phone and asked to participate in a brief interview about their experience in GAPcare. We aimed to interview participants until thematic saturation was reached. Interviews took place over the phone or at the home of the participant, depending on the individual needs. We completed interviews with randomly selected patients and caregivers from the original study from June 2018 until January 2019. Interviews occurred within 6 months of the fall-related ED visit. We felt that patients and caregivers would be able to remember details regarding the fall and ED visit within this time frame. The ideal time frame between fall event and interview has not been studied. Dyads (i.e., patient with CI and caregiver) were only interviewed in person. When desired by the patient or caregiver, we interviewed them together.

Study Protocol

We developed an interview guide based on prior qualitative research on falls16 and the clinical expertise of the study authors. The qualitative interview consisted of queries into the following domains: 1) experiences with ED care, 2) symptom management after ED evaluation, 3) quality of in-ED and outpatient professional and provider communication, 4) views of the care transition, 5) perceptions of barriers to engage with follow-up care, and 6) perceptions of clinical trajectories after the ED visit.

We developed two interview guides—one tailored to the patient and the other to the caregiver. The patient and caregiver interview guides are available as supplementary material accompanying the online article (Data Supplement S1, Appendixes S1 and S2 [, available as supporting information in the online version of this paper, which is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/acem.13938/full]). The semistructured interview guide included the study rationale, an overview of the qualitative in-depth interview process, and potential queries designed to capture the domains listed above. It contained open-ended questions with follow-up questions and probes specific to study goals. We piloted the planned questions with two older adults prior to recruiting participants into the study to ensure that the questions were understood as intended. The piloted study questions were refined based on feedback from these individuals and members of the study team with expertise in qualitative methods, including incorporating exact language of the older adults from the piloting process.

Prior to starting the interview, participants were asked to verbally consent to the interview and its recording. Study personnel (EG and AM; both female) conducted interviews with patients and caregivers. EG is an emergency physician with formal qualitative research training who performs research on fall-related ED visits in older adults. AM completed graduate studies in qualitative research techniques and was trained to the interview guide by the PI. Interviewers collected basic demographic information and recorded brief field notes immediately after the interview. The interviewers were not part of the care team that recruited participants into the study during the index ED visit and therefore did not have an existing relationship when the interviews commenced.

Interviews were recorded, deidentified, and transcribed verbatim by professional medical transcriptionists. Transcripts were reviewed by the authors and corrected when the transcript passage was incomprehensible or had transcription errors. Recordings were destroyed after certification of the transcription to ensure confidentiality.

Data Analysis

We used applied thematic analysis12 to guide the data analysis, which included the following steps: 1) familiarization with the data through reading and rereading the transcripts and noting initial observations and 2) developing a set of codes based on our interview questions and interview debriefs to identify and sort textual data. Major topics and subtopics were coded in pairs by four study personnel and then reconciled through team discussion. NVivo software (version 12) was used to organize the coded data.17 Transcripts and final codes were entered into the NVivo project. 3) We used a team-based approach and two authors iteratively reduced the data, identifying patterns, themes, and subthemes that emerged across participants and interviews. 4) We reviewed themes in relation to the coded extracts and entire data set and selected representative quotes from the interviews to illustrate the themes. 5) We recorded coding definitions and decisions as well as ideas about emerging themes in an ongoing audit trail. 6) Two study authors (CG and EG) then prepared the analytic narrative and contextualized it using the existing literature.

RESULTS

The GAPcare intervention study recruited 110 patients from January 2018 until March 2019.18 None of the patients or caregivers called refused to participate or had hearing impairment. We conducted interviews until thematic saturation was achieved with a total of 22 interviews with 14 patients and 12 caregivers. Four interviews were patient–caregiver dyads. No repeat interviews were performed. Interviews lasted a mean of 43 minutes, with a range of 14 to 109 minutes. Interviews were conducted a mean (±SD) of 95 (±41) days after the initial ED encounter, with a range of 18 to 173 days. Patients were on average 83 years old, nine of 14 patients were women, and two of 14 had CI (Table 1). Six of the 12 caregiver interviews were with reference to a patient with CI. Of the 12 caregivers, four were daughters, one was a son, three were wives, one was a husband, one was a sister, one was a niece, and one was a female cousin. We identified four main themes from the qualitative data: 1) the fall as a trigger for psychological and physiological changes, 2) SNF placement decision-making process, 3) direct effects of fall on caregivers, and 4) barriers to receipt of recommended follow-up. Subthemes and representative quotes for each theme are identified in Table 2.

Table 1.

Participant and Interview Characteristics

| Patient sex | |

| Female | 9 (64.2) |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean (±SD) | 83 (±7) |

| Primary injury at ED visit | |

| Abrasion/laceration | 6 (27.2) |

| Fracture | 1 (4.5) |

| Contusion | 11 (50.0) |

| Weakness/decreased function | 2 (9.1) |

| Back pain | 2 (9.1) |

| ED discharge disposition | |

| Home | 6 (27.2) |

| Home with services | 11 (50.0) |

| Facility | 5 (22.8) |

| Any SNF stay during study time frame, yes | 7 (31.8) |

| Insurance status | |

| Medicare | 5 (22.8) |

| Private | 1 (4.5) |

| Medicare and private | 16 (72.7) |

| Interview types | |

| Patient | 10 (45.5) |

| Caregiver | 8 (36.3) |

| Patient-caregiver dyads | 4 (18.2) |

| GAPcare study arm | |

| Intervention | 20 (90.9) |

| Usual care | 2 (9.1) |

| In reference to patient with cognitive impairment* | |

| Yes | 6 (27.3) |

| Time between fall ED-visit and interview (days) | |

| Mean (±SD) | 95 (±41) |

| Range | 18–173 |

| Primary language | |

| English | 22 (100.0) |

Data are reported as n (%) unless otherwise specified.

SNF = skilled nursing facility.

Identified by Six-Item Screener.

Table 2.

Summary of Themes and Illustrative Quotes

| Themes/Subthemes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Theme 1—The fall as trigger for psychological and physiological changes: patients and caregivers noted psychological and physiological changes after a fall, including the development of fear of falling and changes in gait and mobility. | |

| 1A. Gait speed and walking habits | “Yeah, well [I’m] more careful, I take a little bit more time because I used to speed around. Now I got two moves, slow and stop.” |

| 1B. Social isolation | “I took one shower a week because getting undressed, getting out of the sling was hard because my arm was just hanging down useless … I think that was the hardest thing in a way because if you can’t dress yourself. That’s a really special feature I think of being human. I slept in my clothes for weeks because it was so difficult to, such an operation for me to change what I was wearing.” “I felt as if I was under house arrest being in the house for like six weeks and not going out … very isolated. Isolated. There was a feeling of really being isolated.” |

| 1C. Giving up prior hobbies and difficulties within the home environment | Patient: “I more have a fear of falling when it’s icy and snowy out. I get very nervous about that.” Caregiver: “She’s nervous about a bunch of other things too, like falling up the stairs. She won’t go up the stairs.” Patient: “Oh yeah he [caregiver] knows that it’s because of the way the stairway is. I’m nervous about coming down the stairs.” Caregiver “She was nervous on this particular one because what happened the last time. She’s very cautious.” Caregiver: “Are there things Dad that you don’t want to do anymore?” Patient: “Oh yeah. I’m afraid to fall. I can tell you one is the garden. That whole thing in the back, that all used to be garden, now it’s like three quarters grass, I just planted grass.” “I actually was told that by one of the doctors I see. If you fall, you could end up in the nursing home and it really might be the end of your life as you know it. So that was terrifying.” |

| 1D. Reluctance to use assistive devices after a fall | Caregiver: “There’s a couple of canes in the house. There’s a walker in the house. There was a wheelchair in the house … and he wouldn’t use it. The walker was a waste, because you’d tell him to use it and he’d come out and park it here. And I got to the bathroom, and before you could, he’d be gone. No walker.” Caregiver: “He left the hospital with a walker but doesn’t use it. He has a cane which he uses sometimes, a lot of times, but say for instance we went to a funeral and he didn’t want to use it so he didn’t. He doesn’t want to admit he’s getting old I guess. He’s having a hard time. You know, that’s giving in.” Patient: “Okay, so I got the Lifeline, but I hate how to take the cane, because I feel like an old lady. But I see that I’m getting away from it and I’m seeing more people with canes than me.” |

| Theme 2—SNF placement decision-making process: several factors influence the decision to agree to SNF placement including the amount of community and home caregiver support as well as concerns over the loss of independence. | |

| 2A. Family and community support in discharge to home | “It would be a lot of personal factors that would go into that kind of decision [to be discharged to SNF], and I had everything going for me here but I could see how many people would not and would have to go to rehab. My situation at home was so good it was better for me to be here than in a rehab place dependent on nurses or whatever that goes on there. If I didn’t have a husband who I knew would do everything for me I would have needed the rehab.” Caregiver: “So we have strong church affiliations and we have friends from church that have been more than kind, almost like family. Our neighbors are good, people from the gym, people from BoneBuilders, you know, different colleagues of his, colleagues of mine. They really have come to our aid and we really appreciate all that.” |

| 2B. Perceptions of SNFs | "Why don’t you go on live in one of them?" I says, "No! I don’t like ’em." I don’t. It’s too clustered. It’s alright for people in their 80s and 90s, but not for me! I’m used to being on the go. But, I gotta take it easy.” |

| 2C. Caregivers discern between “good” and “bad” rehabilitation facilities | “I mean, a lot of times it is the family members that do the care, but when it’s the hand-off to the homes, I feel sometimes … I mean, she’s at a good facility, it’s not like, you know, we stuck her some place, but …” |

| 2D. Costs of long-term care | Caregiver: “I’m very grateful and I do have concerns of I really want to keep him at home. We have long-term care insurance. So when the time comes, I’m hoping that I have people in place that I have reliable help. But I do want to keep him at home. I want him to be comfortable and feeling he’s in a safe environment that he knows. But if the day comes that I really can’t do that, then we will go into skilled living or dementia care and I’ll be there every day.” Caregiver: “My mother has exhausted all her income. Now, we got to pay for everything. It would be a lot cheaper for them to keep her here.” |

| 2E. Safety at SNFs | Caregiver: “And, because she has dementia, most of the time she wouldn’t use a walker. At the nursing home, she doesn’t move without it. But, when she’s here, she will not use the walker. She’ll sneak. Because she thinks she can get away with it. There [at SNF], she won’t sneak because she knows that they’ll… Well, they already won’t let her walk by herself anymore. They put a belt on her, and she walks with a walker, but there’s somebody right with her the whole time.” |

| Theme 3—Direct effects of fall on caregivers: caregivers make changes to their lives to accommodate their family member after a fall occurs. | |

| 3A. Adjustments by caregivers | Caregiver: “I can’t do it by myself. I can’t be trapped in the house 24 hours a day because there’s nobody coming in here to watch her.” Caregiver: “I sleep on the sofa now so that if he needs anything, I’m there and that’s fine. I’m trying, you know, to find [help, so] I’m comfortable with leaving him … My neighbor next door will stay with him if I want to go grocery shopping. The other night I needed to go to the drug store. My neighbor across the street came and sat with him, but I hate to ask too often.” |

| 3B. Part of the health care team | Caregiver: “I call myself a health care worker while I had him home, cause it was difficult.” |

| Theme 4—Barriers to receipt of recommended follow-up: patients and families feel overwhelmed and uncertain and are often choosing not to obtain recommended follow-up. | |

| 4A. Discordant recommendations | Caregiver: “We go to the face-to-face [with the primary care doctor], and now he tells us this, this, this, this. The hospital wanted him to have one of those Holters on to monitor his heart. He felt, let’s do a stress test, not [the Holter]…We go over the hospital visit, all that. He said, basically, the hospital wanted him to do one thing, he decided something else. And then, my mother ‘the boss’ decides well, we’re not doing that either. We’re going to see the heart doctor, which is good because the heart doctor told us that he didn’t want … the stress test.” |

| 4B. Ambivalence | Interviewer: “Have you seen your doctor since you had your lip repaired? Your primary care doctor?” Patient: Probably. Probably. I’ve been going to so many doctors and dentists. This tooth was coming out, too.” |

| 4C. Fear of falling | Caregiver: “Only hurdle now is to get her out of the house to see her primary care physician. She has not seen him in a year, and he has put his foot down and said he’s not renewing anymore of her prescriptions until he sees her. She doesn’t want to go out of the house because she’s afraid to fall.” |

| 4D. Wait time | Interviewer: “Do you have plans to see her primary care doctor? Or have you seen her primary care doctor after the fall? Caregiver: “I called the primary care doctor and the first appointment I could get was right before Christmas. She has an appointment right after Christmas. So, I just didn’t think it was that important …” |

SNF = skilled nursing facility.

Illustrative quotes below are noted with a transcript ID number and participant characteristics: C = caregiver; CD = caregiver of person with dementia; P = person without dementia; PwD = person with dementia).

Theme 1—The Fall as Trigger for Psychological and Physiological Changes: Patients and Caregivers Noted Psychological and Physiological Changes After a Fall, Including the Development of Fear of Falling and Changes in Gait and Mobility

Patients were noted to have varying levels of physical recovery in the postfall period. Several patients appeared to be unfazed by the fall, stating that they had not appreciated a decline in functional ability after the fall. In caregivers and patients who did note a change in function after the fall, those who noted a quicker recovery to prefall level of function attributed the response to various visiting in-home services as well as staff at SNFs. Several other older adults bolstered their postfall level of independence by engagement in classes.

In addition to the potential physical sequelae of the fall, patients recounted a significant psychological burden in the postfall time period. One participant in the UC arm of the study stated,

I felt as if I was under house arrest being in the house for like six weeks and not going out because, of course, the weather was awful. Very isolated. Isolated. There was a feeling of really being isolated. [220P_woman]

Participants reported experiencing the fear of falling again after their initial fall. Despite family member’s installation of safety-supporting instruments in the house and the continued use of assistive devices, one caregiver stated, “She’s nervous about a bunch of other things too, like falling up the stairs. She won’t go up the stairs” [130C_niece]. After the fall, two patients also noted giving up hobbies (e.g., gardening) that they enjoyed and found meaningful due to the fear of falling.

After a fall, the physical and psychological recoveries were inextricably linked for several interviewees. One participant sustained a humerus fracture and required the use of a sling. In describing her new mobility limitations and the subsequent psychological toll, she described her arm as “hanging down useless” and her inability to get dressed as particularly dehumanizing.

Additionally, the fear of falling noted by many older adults resulted in its own form of physical limitations, articulated by one patient, “I take a little bit more time because I used to speed around. Now I got two moves, slow and stop” [150P_woman]. Despite the varying physical needs surrounding recovery, patients and caregivers noted a reluctance to use instrumental and assistive devices after the fall, as it seemingly made the patient appear “old.”

Theme 2—SNF Placement Decision-making Process: Several Factors Influence the Decision to Agree to SNF Placement Including the Amount of Community and Home Caregiver Support as Well as Concerns Over the Loss of Independence

Patients and caregivers noted many things that influenced their decision to go (or not) to a SNF after the ED visit. The level of community support was frequently shared as a positive benefit to continued community dwelling. Patients stated that dedicated and effective caregiver support also helped them decide against SNF placement. One patient captured the sentiments of several others by acknowledging that patients lacking significant support in the home environment may require a SNF.

It would be a lot of personal factors that would go into that kind of decision [to be discharged to SNF], and I had everything going for me here but I could see how many people would not and would have to go to rehab. My situation at home was so good it was better for me to be here than in a rehab place dependent on nurses or whatever that goes on there. If I didn’t have a husband who I knew would do everything for me I would have needed the rehab. [130P_woman]

Caregivers noted that they played a significant role in the SNF placement decision, particularly when taking into account their own functional abilities. The decision to place their loved one in a SNF was made clear when the assistance needs became greater than their own functional abilities. Several additional caregivers described their attempt to discern between “good” and “bad” SNF facilities, not wanting to be viewed as abandoning their loved ones.

In the postfall time period, caregivers also noticed a difference in their loved one’s acceptance of assistance between the home setting and the SNF setting. One daughter, whose mother lived in a SNF, noted that her mother with CI was more open to receiving help at a SNF than at home. In the home environment, the patient was more likely to ignore assistive devices, despite their incorporation into numerous rooms within the house. Alternatively, attentive SNF staff limited the patient from walking without an assistive device, as they “wouldn’t let her get away with it.” The decision regarding SNF placement was also influenced by financial considerations described by caregivers. Another caregiver also cited the importance of long-term care insurance and the comfort that is provided to the family should SNF services be required in the future.

Two related patient-specific barriers were frequently communicated during interviews regarding the decision for SNF placement. Prominent among many participants was the desire for older adults to maintain independence in the community setting. Despite prior falls, patients also did not want to be placed in SNFs, because that step seemed a loss of independence and a prominent sign of aging. Recounting her conversation with health care professionals and caregivers, one participant stated,

‘Why don’t you go and live in one of them?’ I says, ‘No! I don’t like ‘em.’ I don’t. It’s too clustered. It’s alright for people in their 80s and 90s, but not for me! … I felt like I was an old lady … I came home, they checked me all out, I was okay. Then I came home, I had one more fall, they took me to the ED to check me out. And they said that I should put me in for rehabilitation. So, I says, ‘Okay. That was fine.’ [200P_-woman]

Theme 3—Direct Effects of Fall on Caregivers: Caregivers Make Changes to Their Lives to Accommodate Their Family Member After a Fall Occurs

Caregivers noted many home modifications that were made after the fall to accommodate the return home of their loved one. Modifications implemented by caregivers included additional handrails, handicapped-accessible home entrances, and the removal of rugs. Caregivers also made modifications to their own lives, particularly regarding driving requirements, sleep habits, and daily care in the postfall time period. To avoid the risk associated with driving, one caregiver stated, “I’m going to pick him up. Pick him and my mother up because I just don’t want my dad driving long distances as much” [90C_daughter]. In the time period while trying to gather additional home services, one caregiver shared the direct effects the patient’s fall had on their sleep pattern as well as the uncomfortable need to ask neighbors for support.

I sleep on the sofa now so that if he needs anything, I’m there and that’s fine. That’s no big deal. I’m trying, you know, to find something that can accommodate me that I’m comfortable with leaving him with whoever it is. My neighbor next door will stay with him if I want to go grocery shopping. The other night I needed to go to the drug store. My neighbor across the street came and sat with him, but I hate to ask too often. [30CD_wife]

Given the implementation of new safety modifications, the need for frequent monitoring of their loved ones, and the coordination of care in the outpatient setting, caregivers were noted to undertake a significant burden in the postfall time period. One caregiver felt as though she were part of the health care team, stating, “I call myself a healthcare worker while I had him home, ‘cause it was difficult” [100CD_wife]. Another caregiver relayed the psychological burden frequently evident when managing a loved one without assistance, “I can’t do it by myself. I can’t be trapped in the house 24 hours a day because there’s nobody coming in here to watch her” [40CD_daughter].

Theme 4—Barriers to Receipt of Recommended Follow-up: Patients and Families Feel Overwhelmed and Uncertain and Are Often Choosing Not to Obtain Recommended Follow-up

After a fall, older adults noted discussions with their PCP regarding fall contributors and the effects of prescribed medications. Aside from interviewees reporting shortcomings with ED to PCP communication on ED discharge and the time-consuming nature of organizing follow-up care, participants noted barriers regarding their ability to understand the complex outpatient setting and the time-consuming nature of arranging follow-up. One caregiver described a situation of discordant recommendations between her mother’s PCP and specialist, resulting in subsequent confusion as to the appropriate diagnostic evaluation and management.

We go to the face-to-face, and now he tells us this, this, this, this. The hospital wanted him to have one of those [Holters] on to monitor his heart. He felt, let’s do a stress test, not [the Holter]…We go over the hospital visit, all that. He said, basically, the hospital wanted him to do one thing, he decided something else. And then, my mother the boss decides well, we’re not doing that either. We’re going to see the heart doctor, which is good because the heart doctor told us that he didn’t want him for the stress test.” [90C_daughter]

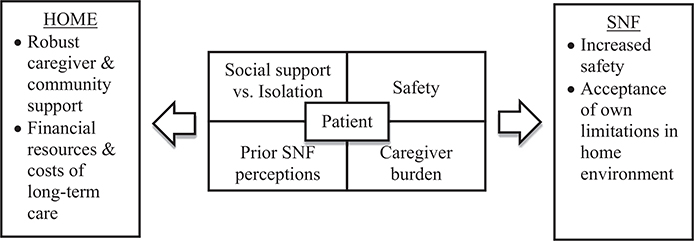

Many narratives highlighted the numerous providers seen after a fall-related ED visit, prompting patients to exhibit ambivalence. When asked if a patient had her lip repaired after the fall, the interviewee responded, “Probably. Probably. I’ve been going to so many doctors and dentists. This tooth was coming out, too” [70P_woman]. Similarly, a separate caregiver noted the prolonged wait to see the PCP gave the impression that follow-up care was not important. “I called the primary care doctor and the first appointment I could get was right before Christmas [2 months after ED visit]. So, I just didn’t think it was that important …” [40CD_daughter]. When the importance of follow-up was evident to caregivers, they were still noted to struggle with the psychological burden that patients experience in the postfall period. A significant fear of falling prevented one patient from attending a PCP visit: her caregiver stated, “Only hurdle now is to get her out of the house to see her primary care physician. He has put his foot down and said he’s not renewing anymore of her prescriptions until he sees her … She doesn’t want to go out of the house because she’s afraid to fall” [140CD_-cousin]. A developed care transition conceptual model (Figure 1) identifies four areas considered by older adults in selecting between home and SNF care settings: social support versus isolation, safety, prior SNF perceptions, and caregiver burden.

Figure 1.

Care transition conceptual model for older adults after a fall-related ED visit. SNF = skilled nursing facility.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to characterize perspectives of older adults who presented to the ED after a fall and their caregivers regarding post-fall recovery and the SNF placement decision-making process. Through in-depth qualitative interviews we identified four central themes: 1) the fall as a trigger for psychological and physiological changes; 2) SNF placement decision-making process; 3) direct effects of fall on caregivers; and 4) barriers to receipt of recommended follow-up. The lived experiences of patients and caregivers highlight opportunities to improve the care of older adults presenting to the ED after a fall. Clinicians should be aware of the concerns that patients and families have about SNF placement and what their anticipated experiences are after ED discharge. This is particularly important given the aging of population.

Our study revealed that patients experience varying trajectories of physiological recovery after a fall. Many of the interviewees described a major psychological burden that was brought on by the fall, with prominent feelings of isolation and further fear of falling. The important link between the physical recovery and the psychological outcomes that older adults experience after a fall is a finding not to be overlooked. Prior qualitative studies, including Yardley et al.,16 noted the views of older adults towards fall prevention interventions. While interventions (e.g. strength and balance training) were not ED-initiated, participants noted that they experienced many unanticipated benefits aside from solely future fall reduction. Benefits of exercise for fall prevention can be discussed with older adults in the ED and include: interest and enjoyment, improved health, mood, and independence. Similar to the findings of our study, barriers to participation in fall prevention strategies identified by this prior literature include: denial of falling risk, the belief that no additional falls-prevention measures were necessary, and practical barriers to participation (e.g. transport, cost). Given the noted reluctance, more recent technology-based (e.g. sensors, cameras) interventions have been used in a myriad of ways for older adults including injury prevention19,20 and fall detection.21,22 Older adults seeking care in the ED after a fall offer healthcare providers a critical ‘sentinel moment’ to assess fall risk, discuss prevention techniques and perceived barriers, and set expectations regarding the possibility of future fear of falling.

Given the complexity of the post-fall time period and the SNF placement decision-making process, qualitative research is well suited to assess generated themes. Prior qualitative studies have assessed community caregivers’ concerns of care recipients’ risk of falling and management at home,23 as well as families’ experiences with relationships and the quality of care following SNF placement of an older relative.24 Ang et al.23 identified four themes in their interviews with carers: carers’ perception of fall and fall risk, care recipient’s behavior and attitude towards fall risk, care recipient’s health and function, and care recipient’s living environment. The findings of our study highlight the many factors in the post-fall period that patients and caregivers consider in determining if SNF placement is indicated. The decision to accept SNF care after a fall represents a branch point, where older adults confront the sense of losing independence, being away from family on a daily basis, and also the perception of appearing ‘old’. With the known and observed desire for older adults to remain independent for as long as able, the SNF setting is viewed as a ‘last resort’. Our conceptual model (Figure 1) identifies key considerations of the patient in the SNF placement decision-making process: social support vs. isolation, prior SNF perceptions, safety, and caregiver burden. We found that patients prefer the home environment if they have a robust support system and the financial means to pay for long-term care costs. Patients stated they would consider SNF placement if they had physical and environmental limitations or if the caregiver identified home safety concerns. Prior SNF research has focused on predictors for institutionalization,25 with less known regarding the placement decision-making process from the patient and caregiver’s perspective. Program development and future research studies are needed to better incorporate support persons of older adults as they provide unique perspectives to fall prevention intervention strategies and the SNF placement decision-making process.

Patient deterioration has long been considered a driving factor for the decision to end home care,26 with this study adding qualitative caregiver fatigue themes such as sleep changes, feeling ‘trapped’, and reluctantly requiring neighborhood assistance to care for their loved one after a fall-related ED visit. Aside from the direct effects on caregivers, interviews often highlighted the financial considerations that families experience in determining the optimal care setting for their loved ones. Furthermore, the caregivers in this study were noted to frequently balance promoting independence and autonomy in their loved one, with attempting to maintain their safety in the community setting. Notably, caregivers sometimes cited the familiarity of the home environment as a reason their loved ones were more likely to be resistant to assistance in the home setting in comparison to the SNF environment.

Future research should focus on the relationships between caregivers and patients and explore tools that could be used to aid the decision-making process surrounding SNF placement. Prior research highlights that caregivers appreciated a healthcare professional acting as a decision-making coach,27–29 yet few interventions exist to improve caregivers’ involvement in the decision-making process.30 Clinicians should be encouraged to seek the perspectives of both patients and caregivers in the acute setting to promote an open and early conversation regarding an environment that balances autonomy and safety.

Finally, our study determined that older adults recognize many barriers in acquiring post-fall follow-up care in the outpatient setting that should be considered by ED clinicians before discharge. Most evident from caregivers and patients was the confusion regarding conflicting care plans of different providers, as well as the high volume of providers individuals were asked to see in follow-up. Optimal triage of patients into primary care physician (PCP) visits, using technology to help with transitions, and providing patients and caregivers with tools to make health care appointments easier would help address some of the barriers found in this study. From this study, we have learned that a disjointed and uncoordinated approach to follow-up care in the outpatient setting often will result in ambivalence and the impression that follow-up care is not important. This may, in part, strengthen the argument that fall prevention strategies should start in the ED before discharge and should provide urgency to policymakers to present solutions that help patients get the care they need expeditiously.

LIMITATIONS

Our study was conducted at two EDs within one health system in the Northeast United States, therefore potentially restricting generalizability. However, we expect that many older adults and caregivers will have similar experiences after a fall. This study mainly included patients from the INT arm of the GAPcare study, because a major objective of this work was to improve the intervention and care delivered to older adults after a fall. These patients were provided with additional support through PT and pharmacy consultations in anticipating their recovery from injury and identifying reasons for the fall and may have had a more favorable experience than the average older adults presenting to the ED for a fall. However, we believe that lessons learned from these interviews can inform ED care of older adults as a whole. Additionally, women were overrepresented in our study population as both patients and caregivers. This reflects that women are more likely to experience nonfatal falls and are more likely to be caregivers. Additionally, our understanding and interpretation of the data may have potentially introduced researcher or confirmation bias. We minimized this bias by using semistructured interview guides and reconciling discrepancies through team discussion. We included team members who are neither physicians nor trained in emergency medicine in this study to independently evaluate analyses and avoid researcher bias. Although many best practices of qualitative research12,13 were followed, we did not return transcripts to participants for checking or solicit interviewee feedback after themes were generated.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, this study qualitatively reports on the perspectives of older adults and caregivers after a fall-related ED visit. The fall was seen as a trigger for postfall physiological and psychological changes including changes in gait and a prominent fear of falling. The multifactorial decision-making process regarding skilled nursing facility placement for older adults after a fall often evoked patient discussions of their desire for independence and not appearing “old” as primary reasons for reluctance to skilled nursing facility placement. The direct effects of their loved one’s fall caused caregivers to cite changes to sleep location, driving habits, and seeking assistance from neighbors. Patients and caregivers also recognized significant barriers in the coordination of care to the outpatient setting after discharge from the ED after a fall. Consideration of these perspectives is essential in developing practices to improve the overall transition of care between the ED, primary care physician, and skilled nursing facility settings in older adults after a fall.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by the Yale National Clinician Scholars Program and by CTSA grant TL1 TR001864 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH. The research reported also received support from the National Institute on Aging (R03AG056349), AHRQ (T32AG023482), and SAEMF/EMF GEMSSTAR for Emergency Medicine Supplemental Funding (RF2017-010).

Footnotes

The authors have no potential conflicts to disclose.

Supporting Information

The following supporting information is available in the online version of this paper available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/acem.13938/full

Data Supplement S1. Supplemental material.

References

- 1.Bergen G, Stevens MR, Burns ER. Falls and fall injuries among adults ≥65 years--United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:993–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevens JA, Sogolow ED. Gender differences for non-fatal unintentional fall related injuries among older adults. Inj Prev 2005;11:115–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stel VS, Smit JH, Pluijm SM, Lips P. Consequences of falling in older men and women and risk factors for health service use and functional decline. Age Ageing 2004;33:58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar A, Carpenter H, Morris R, Iliffe S, Kendrick D. Which factors are associated with fear of falling in community-dwelling older people? Age Ageing 2014;43:76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns ER, Stevens JA, Lee R. The direct costs of fatal and non-fatal falls among older adults - United States. J Safety Res 2016;58:99–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Houry D, Florence C, Baldwin G, Stevens J, McClure R. The CDC Injury Center’s response to the growing public health problem of falls among older adults. Am J Lifestyle Med 2016;10:74–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carpenter CR, Cameron A, Ganz DA, Liu S. Older adult falls in emergency medicine - a sentinel event. Clin Geriatr Med 2018;34:355–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sri-On J, Tirrell GP, Bean JF, Lipitz LA, Liu SW. Revisit, subsequent hospitalization, recurrent fall, and death within 6 months after a fall among elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med 2017;70:516–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tinetti ME, Williams CS. Falls, injuries due to falls, and the risk of admission to a nursing home. N Engl J Med 1997;337:1279–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carpenter CR, Shah MN, Hustey FM, Heard K, Gerson LW, Miller DK. High yield research opportunities in geriatric emergency medicine: prehospital care, delirium, adverse drug events, and falls. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2011;66:775–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaudhuri S, Thompson H, Demiris G. Fall detection devices and their use with older adults: a systematic review. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2014;37:178–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 4th ed. Los Angeles: SAGE, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg EM, Resnik L, Marks SJ, Merchant RC. GAPcare: the Geriatric Acute and Post-acute Fall Prevention Intervention - a pilot investigation of an emergency department-based fall prevention program for community-dwelling older adults. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2019;5:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carpenter CR, DesPain B, Keeling TN, Shah M, Rothenberger M. The Six-Item Screener and AD8 for the detection of cognitive impairment in geriatric emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med 2011;57:653–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yardley L, Bishop FL, Beyer N, et al. Older people’s views of falls-prevention interventions in six European countries. Gerontologist 2006;46:650–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.QSR International. NVivo. Available at: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/home. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- 18.Goldberg EM, Marks SJ, Ilegbusi A, Resnik L, Strauss DH, Merchant RC. GAPcare: The Geriatric Acute and Post-Acute Fall Prevention Intervention in the Emergency Department: Preliminary Data. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68:198–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Potter P, Allen K, Costantinou E, et al. Evaluation of sensor technology to detect fall risk and prevent falls in acute care. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2017;43:414–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.France D, Slayton J, Moore S, et al. A multicomponent fall prevention strategy reduces falls at an academic medical center. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2017;43:460–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rantz M, Skubic M, Abbott C, et al. Automated in-home fall risk assessment and detection sensor system for elders. Gerontologist 2015;55:S78–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khojasteh SB, Villar JR, Chira C, González VM, de la Cal E. Improving fall detection sing an on-wrist wearable accelerometer. Sensors 2018;18:1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ang SG, O’Brien AP, Wilson A. Understanding carers’ fall concern and their management of fall risk among older people at home. BMC Geriatr 2019;19:144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryan AA, McKenna H. ‘It’s the little things that count’. Families’ experience of roles, relationships and quality of care in rural nursing homes. Int J Older People Nurs 2015;10:38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kojima G Frailty as a predictor of nursing home placement among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2018;41:42–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gold DP, Reis MF, Markiewicz D, Andres D. When home caregiving ends: a longitudinal study of outcomes for caregivers of relatives with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995;43:10–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White DB, Cua SM, Walk R, et al. Nurse-led intervention to improve surrogate decision making for patients with advanced critical illness. Am J Crit Care 2012;21:396–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Légaré F, Stacey D, Pouliot S, et al. Interprofessionalism and shared decision-making in primary care: a stepwise approach towards a new model. J Interprof Care 2011;25:18–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ducharme F, Couture M, Lamontagne J. Decision-making process of family caregivers regarding placement of a cognitively impaired elderly relative. Home Health Care Serv Q 2012;31:197–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garvelink MM, Ngangue PA, Adekpedjou R, et al. A synthesis of knowledge about caregiver decision making finds gaps in support for those who care for aging loved ones. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:619–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.