Abstract

Objective.

Determine the association between household food insecurity and habitual sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption among WIC-enrolled families during the first 1,000 days.

Methods.

Cross-sectional analysis of pregnant women and mothers of infants under 2 years-old in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) was performed. Families recruited sequentially at consecutive visits completed food insecurity and beverage intake questionnaires. Estimated logistic regression models controlled for socio-demographic characteristics.

Results.

Of 394 Hispanic/Latino mothers and 281 infants, 63% had household food insecurity. Food insecurity significantly increased odds of habitual maternal (unadjusted odds ratio (OR)=2.39, 95% CI=1.27–4.47, P=0.01) and infant SSB consumption (OR=2.05, 95% CI=1.15–3.65, P=0.02), and the relationship was not attenuated by maternal age, education, or foreign-born status.

Conclusions and Implications.

Food insecurity increased odds of habitual SSB consumption in WIC families. Interventions to curb SSB consumption among WIC-enrolled families in the first 1,000 days in the context of household food insecurity are needed. (149 words)

Keywords: pregnancy, infant, food insecurity, sugar-sweetened beverages, drinking behavior

INTRODUCTION

Poor nutrition in the first 1,000 days-pregnancy through age 2 years-influences risk for childhood obesity and adverse health.1 Sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption by pregnant women and young children has been implicated in child obesity, a precursor to cardio-metabolic syndrome.2 Sugar-sweetened beverages, such as regular soda and sports drinks, are liquids sweetened with added sugars.3 Increased SSB intake has been associated with lower household income, racial/ethnic minority status, and poor diet quality.4 Young children exposed to SSBs may develop habitual intake, with negative effects on growth and development.5 Thus, it is important to understand modifiable drivers of SSB consumption during pregnancy and early childhood.

One potential driver of SSB consumption is food insecurity, defined by a lack of consistent access to sufficient nutritious food.6 Food insecurity affects roughly 12% of U.S. households and 1 in 7 U.S. children.6 Research has shown increased SSB consumption among adults with food insecurity,7–10 although one study of food-insecure pregnant women found no differences in SSB consumption.4 Previous work on the relationship between food insecurity and child SSB consumption was limited to children age 2 years and older,11–15 and the effect of food insecurity on SSB consumption spanning the first 1,000 days remains poorly understood.

Quantifying the relationship between food insecurity and SSB intake in the first 1,000 days will inform future nutrition interventions to limit SSB consumption during a vulnerable time in child development. The objectives of this study were to examine the association between household food insecurity and habitual SSB consumption in mothers and infants during the first 1,000 days.

METHODS

PARTICIPANTS AND SETTING

This original research study was a cross-sectional analysis of low-income predominantly Hispanic/Latino families enrolled in a multisite Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) in northern Manhattan who participated in the New York City First 1,000 Days Study between March and June 2017.16 Written informed consent from mothers (pregnant women and women with infants less than 2 years-old) who were recruited sequentially at consecutive visits and could answer questions in English or Spanish was obtained. A total of 394 mothers (113 pregnant women, 9 pregnant women with infants, and 272 mothers of infants) and 281 infants less than 2 years-old participated. The study was approved by the Columbia University Irving Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

MEASURES

Maternal SSB consumption was measured from the 15-item Beverage Intake Questionnaire (BEVQ-15), a validated staff-administered quantitative beverage frequency questionnaire for adults about intake in the past month.17 The BEVQ-15 SSB intake categories included soft drinks, sweetened juice, tea or coffee with sugar, and energy drinks. Maternal habitual SSB consumption was defined as intake at least once per week. Infant SSB consumption was measured from a validated infant beverage frequency questionnaire utilized in the Iowa Fluoride Study18 that captured intake in the past week of sugared juice drinks, sports drinks, reconstituted powders, and soda. Habitual infant SSB consumption was defined as any consumption as added sugars are not recommended for children under 2 years,19 and any infant SSB consumption is correlated with habitual SSB intake in childhood.20,21 One hundred percent fruit juice was not counted as a SSB.

Household food insecurity was measured using the validated 2-item Hunger Vital Sign™.22 Households were food insecure if the response was “sometimes true” or “always true” to either of the following statements: “Within the past 12 months we worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more” and “Within the past 12 months the food we bought just didn’t last and we didn’t have money to get more.”

Maternal age, race/ethnicity, education, foreign-born status, marital status, household size, infant sex, and infant age were self-reported characteristics that were clinically relevant and a priori demonstrated a relationship with food insecurity risk factors. Mothers self-reported race/ethnicity from a categorized list: White/Caucasian; Asian Indian; Chinese; Filipino; Black or African-American; Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish; American Indian or Alaskan Native; or some other race. Maternal education was based on highest level attained and was used as the socio-economic status indicator because of the sensitivity of income data.

DATA ANALYSES

Using descriptive statistics, distributions of all covariates were examined. Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests for continuous variables were performed to test for significant differences between covariates among those with and without household food insecurity. Covariates of interest were selected for regression models based on 1) clinical significance (e.g., infant age) and 2) statistical significance in bivariate testing. The association between household food insecurity and habitual maternal or infant SSB consumption was estimated in unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models. In adjusted models, each covariate of interest was individually added to the model. As the high proportion of families with household food insecurity led to small sample sizes for the comparison group, one covariate per model was included in each model. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS® 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Tests were 2-sided and a p value of < .05 was selected for statistical significance.

RESULTS

Study participants were 94% Hispanic/Latina, 55% had completed some college or higher education level, and 53% were married or cohabitating (Table). Median age was 29 years and 72% of mothers were foreign-born. Infants had a median age of 6 months and just over 50% were male. Household food insecurity was experienced by 63% of all mothers and 29% of the pregnant women. Mothers born outside of the U.S. were more likely to experience food insecurity.

Table.

Characteristics of WIC-Enrolled Women and Infants According to Household Food Insecurity Status

| Total Sample (N = 394) | Household Food Insecurity | P valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any (N = 249) | None (N = 145) | |||

| Maternal and Household Characteristics | ||||

| Maternal age, years, median (interquartile range (IQR)) | 29 (24–34) | 29 (25–34) | 28 (24–33) | .06 |

| Pregnant woman, n (%) | 122 (31%) | 73 (29%) | 49 (34%) | .37 |

| Parental education, some college or above (either parent), n (%) | 217 (55%) | 127 (51%) | 90 (62%) | .04 |

| Maternal race/ethnicity, Hispanic/Latina, n (%) | 370 (94%) | 236 (95%) | 134 (92%) | .60 |

| Born in the United States, n (%) | 111 (28%) | 56 (22%) | 55 (38%) | .001 |

| Household size, number, median (IQR) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | .48 |

| Infant Characteristics | N=281 | (N=183) | (N=98) | |

| Boy, n (%)a | 143 (51%) | 97 (53%) | 46 (47%) | .38 |

| Age, months, median (IQR) | 6(3–15) | 10 (4–16) | 4 (1–11) | <.001 |

| Maternal and Infant Sugar-Sweetened Beverage (SSB) | ||||

| Consumption | ||||

| Maternal habitual SSB consumption, n (%) | 349 (89%) | 229 (92%) | 120 (83%) | .01 |

| Infant habitual SSB consumption, n (%) | 83 (30%) | 63 (34%) | 20 (20%) | .01 |

WIC: Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

1 infant had missing sex

Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests for continuous variables were performed to test for significant differences between covariates among those with household food insecurity compared to those without (p<.05 selected for statistical significance).

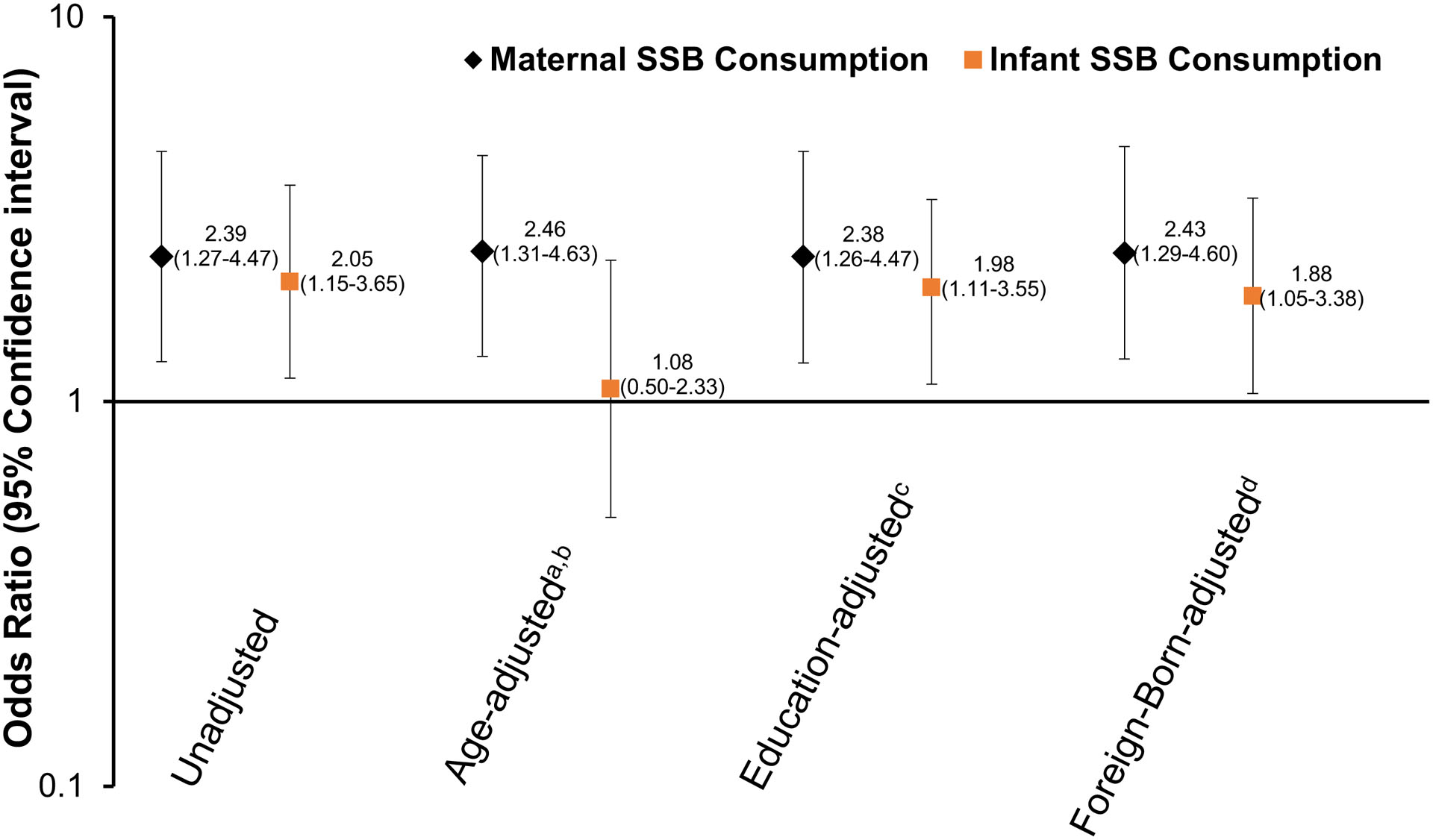

Of the 249 mothers with household food insecurity, 92% habitually consumed SSBs. Of the 183 infants with food insecurity, 34% habitually consumed SSBs (Table). Mothers with food insecurity were 2.4 times more likely to consume SSBs compared to mothers without food insecurity (unadjusted odds ratio (OR): 2.39; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.27–4.47, P=.01) (Figure). These findings persisted after adjusting for maternal age (adjusted OR (AOR): 2.46; 95% CI, 1.31–4.63, P=.01); education (AOR: 2.38; 95% CI, 1.26–4.47, P=.01); or foreign-born status (AOR: 2.43; 95% CI, 1.29–4.60, P=.01). Infants with food insecurity compared were 2 times more likely to consume SSBs compared to infants without food insecurity (OR: 2.05, 95% CI, 1.15–3.65, P=.02), even after adjusting for maternal education (AOR: 1.98; 95% CI, 1.11–3.55, P=.02) or foreign-born status (AOR: 1.88; 95% CI, 1.05–3.38, P=.03). Food insecurity was not significantly associated with infant SSB consumption when adjusting for infant age (AOR: 1.05; 95% CI, 0.40–2.77, P=.85). Per convention, odds ratios were presented on a logarithmic scale.23

Figure.

Associations of Household Food Insecurity with Habitual Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption in the First 1,000 Days. Data from 394 mothers and 281 infants in WIC-Enrolled Families. Odds ratios from multiple logistic regression models for maternal habitual sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption (diamond) and infant habitual SSB consumption (square) on a logarithmic axis.

WIC: Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

aMaternal SSB consumption adjusted for parent age at time of research visit (by 1 year increase)

bInfant SSB consumption adjusted for infant age at time of research visit (by 1 month increase)

cSSB consumption adjusted for highest maternal education level

dSSB consumption adjusted for maternal foreign-born status

DISCUSSION

The first 1,000 days represents a vulnerable time in child growth and development, and nutrition during this window can influence child obesity risk and future health trajectories. The current study showed that among WIC-enrolled predominantly Hispanic/Latino pregnant women, mothers, and infants less than 2 years-old, household food insecurity was significantly associated with maternal and infant habitual SSB consumption within the first 1,000 days. The association between household food insecurity and habitual SSB consumption remained significant after adjusting for maternal age, maternal education, and foreign-born status in separate regression models. However, the association between household food insecurity and infant SSB consumption was not significant when adjusting for infant age.

These findings were similar to those seen in children by Cunningham et al. in which toddlers age 2 years with food insecure mothers consumed soda more days of the week compared to toddlers of food secure mothers.11 Lee et al. also showed that children in middle childhood from food-insecure households consumed more SSBs compared to children from food-secure households.13 The current study advanced these findings by including descriptions of household food insecurity and SSB consumption both in infants under 2 years-old as well as mothers of young infants and pregnant women to span the first 1,000 days.

The current study suggested that routine screening for food insecurity in the first 1,000 days may augment health efforts to limit SSB consumption during pregnancy and prevent infant SSB introduction in a population with increased odds of SSB consumption, thereby reducing child obesity risk. Food insecurity may contribute to household trade-offs on food purchases in favor of lower cost, more calorie-dense foods with poorer nutrient content, such as SSBs, that may drive parent and child dietary patterns. Andreyeva et al. reported that SSBs accounted for 48% of WIC-household purchases.24 Infant SSB intake increases the likelihood of habitual SSB intake into later childhood, likely due to established patterns of SSB consumption in the household.20 Ha et al. showed that maternal SSB consumption was significantly associated with introduction of foods and drinks with added sugars to 6–9 month-old infants.25

Food insecurity screening with The Hunger Vital Sign™, as endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics, has been recognized as an important component of pediatric primary care efforts to identify and address health-related social needs,26 particularly as children of immigrant mothers are at increased risk of household food insecurity than children with U.S.-born mothers.27 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists also recommends that women’s health visits include screening for social determinants of health, such as food insecurity, and referring to community resources as needed.28 Routine food insecurity screening of pregnant women and families at WIC and other health care settings can highlight those who are at risk for food insecurity and increased SSB intake and contribute to targeted nutrition education and health program efforts to reduce added sugar consumption and child obesity risk.

Strengths of this study included adding to the growing body of research that household food insecurity is correlated with SSB consumption in pregnant women, mothers, and infants less than 2 years-old. Additionally, this study’s findings from New York City were consistent with increased SSB consumption noted among Hispanic/Latino toddlers and preschoolers in California.29

This study was also subject to several limitations. Study results were correlational and not causal due to the cross-sectional design. The self-reported questionnaires posed a risk for recall bias and social desirability bias, with maternal under-reporting of food insecurity and SSB intake. The Hunger Vital Sign™ did not differentiate between acute and chronic food insecurity in the last 12 months, and SSB intake patterns may have been different in households with short vs. long-term food insecurity. This study did not include grocery store access, household food purchase locations, and other potentially confounding factors in the relationship between food insecurity and SSB consumption. The sample size did not support inclusion of all covariates of interest, significant and non-significant, in a single regression model due to risk for model instability.

IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

This study expanded upon previous research and demonstrated that household food insecurity was associated with greater odds of SSB consumption in the first 1,000 days among predominantly Hispanic/Latino WIC-enrolled mothers and young infants. Food insecurity screening may be a feasible way to identify those pregnant women and mothers more likely to consume and/or introduce SSBs to infants, thereby increasing child obesity risk. Future longitudinal studies across the first 1,000 days that track food insecurity and SSB consumption patterns will be crucial for development of targeted nutrition and public health interventions to reduce SSB consumption during pregnancy and prevent SSB introduction to infants.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation New Connections Grants through Healthy Eating Research Program (RWJF Grant #74198). Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes And Digestive And Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers K23DK115682 and K01DK114383. Research was also supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program (RWJF Grant #74252). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or other funders.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mameli C, Mazzantini S, Zuccotti GV. Nutrition in the First 1000 Days: The Origin of Childhood Obesity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13090838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jen V, Erler NS, Tielemans MJ, et al. Mothers’ intake of sugar-containing beverages during pregnancy and body composition of their children during childhood: the Generation R Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105:834–841. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.147934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity. Sugar Sweetened Beverage Intake. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/data-statistics/sugar-sweetened-beverages-intake.html. Published October 23, 2018. Accessed September 18, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gamba RJ, Leung CW, Petito L, Abrams B, Laraia BA. Sugar sweetened beverage consumption during pregnancy is associated with lower diet quality and greater total energy intake. PLoS ONE. 2019;14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosales FJ, Reznick JS, Zeisel SH. Understanding the Role of Nutrition in the Brain & Behavioral Development of Toddlers and Preschool Children: Identifying and Overcoming Methodological Barriers. Nutr Neurosci. 2009;12:190–202. doi: 10.1179/147683009X423454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2018. http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=94848. Accessed November 21, 2019.

- 7.Bruce MA, Thorpe RJ, Beech BM, Towns T, Odoms-Young A. Sex, Race, Food Security, and Sugar Consumption Change Efficacy Among Low-Income Parents in an Urban Primary Care Setting. Fam Community Health. 2018;41 Suppl 2 Suppl, Food Insecurity and Obesity:S25–S32. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leung CW, Ding EL, Catalano PJ, Villamor E, Rimm EB, Willett WC. Dietary intake and dietary quality of low-income adults in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:977–988. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.040014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davy BM, Zoellner JM, Waters CN, Bailey AN, Hill JL. Associations among chronic disease status, participation in federal nutrition programs, food insecurity, and sugar-sweetened beverage and water intake among residents of a health-disparate region. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2015;47:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2015.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharkey JR, Johnson CM, Dean WR. Less-healthy eating behaviors have a greater association with a high level of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among rural adults than among urban adults. Food Nutr Res. 2011;55. doi: 10.3402/fnr.v55i0.5819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunningham TJ, Barradas DT, Rosenberg KD, May AL, Kroelinger CD, Ahluwalia IB. Is maternal food security a predictor of food and drink intake among toddlers in Oregon? Matern Child Health J. 2012;16 Suppl 2:339–346. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1094-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharkey JR, Nalty C, Johnson CM, Dean WR. Children’s very low food security is associated with increased dietary intakes in energy, fat, and added sugar among Mexican-origin children (6–11 y) in Texas border Colonias. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee J, Kubik MY, Fulkerson JA. Diet Quality and Fruit, Vegetable, and Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption by Household Food Insecurity among 8- to 12-Year-Old Children during Summer Months. J Acad Nutr Diet. May 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2019.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trapp CM, Burke G, Gorin AA, et al. The relationship between dietary patterns, body mass index percentile, and household food security in young urban children. Child Obes Print. 2015;11:148–155. doi: 10.1089/chi.2014.0105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fram MS, Ritchie LD, Rosen N, Frongillo EA. Child experience of food insecurity is associated with child diet and physical activity. J Nutr. 2015;145:499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woo Baidal JA, Morel K, Nichols K, et al. Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Attitudes and Consumption During the First 1000 Days of Life. Am J Public Health. 2018;108:1659–1665. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hedrick VE, Savla J, Comber DL, et al. Development of a brief questionnaire to assess habitual beverage intake (BEVQ-15): sugar-sweetened beverages and total beverage energy intake. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:840–849. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.01.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marshall TA, Eichenberger Gilmore JM, Broffitt B, Levy SM, Stumbo PJ. Relative validation of a beverage frequency questionnaire in children ages 6 months through 5 years using 3-day food and beverage diaries. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:714–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muth ND, Dietz WH, Magge SN, et al. Public Policies to Reduce Sugary Drink Consumption in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2019;143:e20190282. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park S, Pan L, Sherry B, Li R. The Association of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Intake During Infancy With Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Intake at 6 Years of Age. Pediatrics. 2014;134(Suppl 1):S56–S62. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0646J [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore DA, Goodwin TL, Brocklehurst PR, Armitage CJ, Glenny A-M. When Are Caregivers More Likely to Offer Sugary Drinks and Snacks to Infants? A Qualitative Thematic Synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2017;27:74–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732316673341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hager ER, Quigg AM, Black MM, et al. Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galbraith RF. A note on graphical presentation of estimated odds ratios from several clinical trials. Stat Med. 1988;7:889–894. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780070807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andreyeva T, Luedicke J, Henderson KE, Tripp AS. Grocery store beverage choices by participants in federal food assistance and nutrition programs. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ha DH, Do LG, Spencer AJ, et al. Factors Influencing Early Feeding of Foods and Drinks Containing Free Sugars-A Birth Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14101270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Council on Community Pediatrics, Committee on Nutrition. Promoting Food Security for All Children. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e1431–e1438. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chilton M, Black MM, Berkowitz C, et al. Food insecurity and risk of poor health among US-born children of immigrants. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:556–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Importance of Social Determinants of Health and Cultural Awareness in the Delivery of Reproductive Health Care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e43–e48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watowicz RP, Taylor CA. A Comparison of Beverage Intakes in US Children Based on WIC Participation and Eligibility. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46(3 Suppl):S59–S64. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]