Abstract

Summary

An earlier systematic review on interventions to improve adherence and persistence was updated. Fifteen studies investigating the effectiveness of patient education, drug regimen, monitoring and supervision, and interdisciplinary collaboration as a single or multi-component intervention were appraised. Multicomponent interventions with active patient involvement were more effective.

Introduction

This study was conducted to update a systematic literature review on interventions to improve adherence to anti-osteoporosis medications.

Methods

A systematic literature review was carried out in Medline (using PubMed), Embase (using Ovid), Cochrane Library, Current Controlled Trials, ClinicalTrials.gov, NHS Centre for Review and Dissemination, CINHAL, and PsycINFO to search for original studies that assessed interventions to improve adherence (comprising initiation, implementation, and discontinuation) and persistence to anti-osteoporosis medications among patients with osteoporosis, published between July 2012 and December 2018. Quality of included studies was assessed.

Results

Of 585 studies initially identified, 15 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria of which 12 were randomized controlled trials. Interventions were classified as (1) patient education (n = 9), (2) drug regimen (n = 3), (3) monitoring and supervision (n = 2), and (4) interdisciplinary collaboration (n = 1). In most subtypes of interventions, mixed results on adherence (and persistence) were found. Multicomponent interventions based on patient education and counseling were the most effective interventions when aiming to increase adherence and/or persistence to osteoporosis medications.

Conclusion

This updated review suggests that patient education, monitoring and supervision, change in drug regimen, and interdisciplinary collaboration have mixed results on medication adherence and persistence, with more positive effects for multicomponent interventions with active patient involvement. Compared with the previous review, a shift towards more patient involvement, counseling and shared decision-making, was seen, suggesting that individualized solutions, based on collaboration between the patient and the healthcare provider, are needed to improve adherence and persistence to osteoporosis medications.

Keywords: Adherence, Counseling, Education, Osteoporosis, Patient, Persistence

Introduction

Osteoporosis remains a major health problem worldwide influencing patient’s health-related quality of life, mortality, and representing a substantial economic burden on society. The burden of osteoporosis is further expected to increase as a result of the aging population [1, 2]. Osteoporosis medications have shown to be effective in fracture risk reduction [3]; however, it is well known that adherence to osteoporosis medications is poor and suboptimal, varying from 34 to 75% in the first year of treatment [4, 5]. Persistence levels at 1 year were estimated between 18 and 75% [6]. This suboptimal adherence and persistence leads to increased fracture rate (up to 30%) and worse health outcomes (more subsequent fractures, lower quality of life, and higher mortality), substantially deteriorating the cost-effectiveness resulting from these medications [7, 8].

Improving adherence to osteoporosis medications is therefore needed but this remains a challenging task. Many factors of non-adherence and non-persistence to osteoporosis medications have been identified such as older age, polypharmacy, side effects, and lack of patient education. Reasons for non-adherence are thus numerous and multidimensional, varying for each patient [9]. Several interventions and programs have therefore been developed to improve osteoporosis medications adherence. A previous systematic literature review (SLR) published in 2012 noted several promising interventions to improve osteoporosis medication adherence and persistence, such as drug regimen and patient support, automatic electronic prescription, and pharmacist intervention [10]. This SLR, limited to articles published up to June 2012, further revealed a limited number of studies, the lack of rigorous evaluation of clinical effectiveness, and therefore the need for further studies [10].

Since this SLR, theories and practical experience on adherence and adherence interventions have evolved [11]. Moreover, the methodological quality of non-pharmacological interventions has overall improved. This, together with continuing low adherence to anti-osteoporosis medications [12], the frequent access to the previous SLR, and the publications of several new adherence interventions preceding this study, justifies an update [10].

For this updated review, it was aimed to appraise studies concerning interventions to improve adherence and persistence to medications for osteoporosis patients in primary of secondary care, published between July 2012 and December 2018.

Methods

This systematic review was executed in accordance with the PRISMA statement and with the use of a review protocol [13, 14]. The protocol for this systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (unique ID number: 97472, available on https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/).

Search strategy

With the help of an expert library specialist, a comprehensive systematic literature search was designed and performed in Medline (using PubMed), Embase (using Ovid), Cochrane Library, Current Controlled Trials, ClinicalTrials.gov, NHS Centre for Review and Dissemination, CINHAL, and PsycINFO. Reference list of identified articles were then manually searched, and forward reference searching was conducted in Web of Science. Detailed search strategies can be found in Appendix 1.

Selection criteria

Articles were included if they met the following eligibility criteria: (1) original study which assessed the effects of interventions aimed on improving adherence or persistence of osteoporosis medications, (2) publication date between July 1, 2012, and December 31, 2018 (the search was restricted to this period to provide an update of the previously published SLR [10]), and (3) available in English language. Conference proceedings were not included.

The selection of articles was performed in a standardized manner in a three-step process. First, duplicate records were deleted. Second, articles were analyzed by screening the title and abstract (DC). In case of doubt, the article was included for full-text review. Third, full texts were independently reviewed on the eligibility criteria by two authors (DC and SdK). If necessary, consensus was reached by both authors through discussion with a third author (MH).

Definitions of adherence and persistence

Adherence and persistence to medications have been defined differently in several ways [15]. For organizing data for this review, the following ABC taxonomy, according to Vrijens et al., was followed [16]. Medication adherence consists of the three following quantifiable phases: (A) initiation (when the patient takes the first dose of a prescribed medication), (B) implementation (the extent to which a patient’s actual dosing corresponds to the prescribed dosing regimen, from initiation until the last dose), and (C) discontinuation (when the patient stops taking the prescribed medication, for whatever reason(s)). Persistence is defined as the length of time between initiation and the last dose, which immediately precedes discontinuation [16].

Extracted information

Data from the included studies were independently extracted by two authors (DC and SdK) in a predesigned data abstraction sheet. A third author (LS) checked independently all extracted data. General information including author, year of publication, country, and setting (primary care, secondary care, or other) were first collected, then the intervention specialist (GP, medical specialist, pharmacist, or other), type of study, population, sample size, outcome measurements (adherence or persistence), type of intervention, and follow-up time.

Type of interventions

Interventions extracted from data were classified into four categories based on previous studies [10, 12]: (1) patient education (provision of information), (2) drug regimen, (3) monitoring and supervision, and (4) interdisciplinary collaboration. These interventions were frequently combined with patient counseling (advice and debate on provided information focused on the individual patient). These modalities could be administered as a single- or multicomponent intervention. In this review, a multicomponent intervention halters two different types of components, e.g., provision of educational material and patient counseling, whereas a single component solely uses one intervention.

Study quality

Risk of bias of the included studies was assessed by two researchers (DC and SdK) with the Revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) or the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies - of Interventions (ROBINS-I) assessment tool [17, 18]. To assess study quality, different quality appraisal tools were used specifically designed for each type of study. For observational studies, the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) tool [19] was used. For clinical trials, the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) tool [20] was used. Two researchers (DC and VW) independently evaluated the selected studies. A third researcher (LS) randomly checked four appraisals as additional check. All differences were resolved by consensus through discussion.

Synthesis of results

Due to the expected heterogeneity in the methods of adherence measurement and of study outcomes, the analysis was focused on a qualitative assessment, and no meta-analysis was conducted.

Results

Literature search

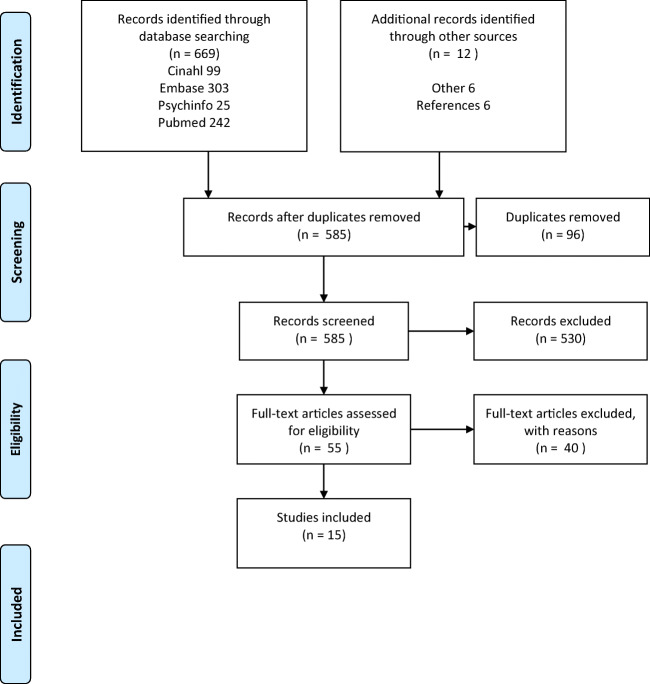

After deletion of duplicate records, our search resulted in 585 articles, of which 55 passed the abstract and title screening (Fig. 1). After full-text assessment, 40 articles were excluded because of the following reasons: no full text available (n = 8), not specific for osteoporosis patients (n = 1), review article (n = 2), lack of a medication adherence intervention (n = 22), conference proceedings (n = 4), published before July 1, 2012 (n = 2), and methodologic article (n = 1), resulting in 15 articles. The PRISMA flow chart is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRIMSA flow chart

Study characteristics

The main study characteristics can be found in Table 1. Twelve studies were randomized controlled trials (RCT) [21–31] of which one was a cross-over RCT design [32]. Other studies were non-randomized, uncontrolled studies [33–35]. A total of 162,804 patients were included, 155,803 in the intervention group and 7001 control patient [30, 35]. There was a large difference in sample sizes varying from 79 to 147,071 [28, 35]. Ninety-five percent of patients came from two studies [24, 35]. The majority of patients were female, and eight studies included solely females [22, 25–28, 30, 32]. Seven studies were European [22, 26, 27, 30–33], five studies North-American [24, 25, 29, 34, 35], two from Australia [21, 28], and one from Japan [23]. Follow-up time varied from 6 to 24 months [21, 28]. Interventions were executed in secondary care (n = 13) [22–32, 34, 35], primary care (n = 1) [33], or in both primary and secondary care (n = 1) [21]. Seven of the 15 interventions were conducted by either physicians and/or nurses/nurse practitioners (n = 7) [21, 24, 26–28, 31, 34]. Other interventions were conducted by trained coordinators (n = 1) [35], medical secretaries (n = 1) [22], pharmacists (n = 1) [33], or a combination of physicians and allied healthcare workers (n = 1) [36]. Four studies did not report by whom the intervention was conducted [23, 25, 30, 32].

Table 1.

The main study characteristics

| Author | Country | Year | Setting | Study design | Inclusion criteria | Number of patients included | Planned follow-up | Administered by | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient education | |||||||||

| 1 | Roux et al. | Canada | 2013 | Secondary care | RCT | Aged ≥ 50 years with a fragility fracture |

I1 370 I2 311 C 200 |

12 months | Allied health professionals and primary care physicians |

| 2 | Tüzün et al. | Turkey | 2013 | Secondary care | RCT | Women aged between 45 and 75 years with postmenopausal osteoporosis and eligible for oral bisphosphonates |

I1 222 I2 226 C NR |

12 months | NR |

| 3 | Bianchi et al. | Italy | 2015 | Secondary care | RCT | Females aged 45–80 years, diagnosed with post-menopausal osteoporosis, receiving a first prescription of an oral drug for OP |

I1 110 I2 111 C 113 |

12 months | Hospital staff (physicians and nurses) |

| 4 | Cram et al. | USA | 2016 | Secondary care | RCT | Aged ≥ 50 presenting for DXA. |

I 3.917 C 3.865 |

12 weeks | Physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants |

| 5 | Gonnelli et al. | Italy | 2016 | Secondary care | RCT | Osteoporotic woman aged ≥ 50 receiving a prescription of an oral osteoporosis medication for the first time |

I 402 C 414 |

12 months | Physician NS |

| 6 | LeBlanc et al. | Australia | 2016 | Secondary care | RCT | English speaking woman aged ≥ 50 with a diagnosis of osteopenia or osteoporosis, not taking anti-osteoporotic medication |

I1 33 I2 32 C 14 |

6 months | Nurse practitioners and physician assistants |

| 7 | Seuffert et al. | USA | 2016 | Secondary care | Observational study | Patients with osteoporosis or osteopenia diagnosed after DXA |

I 447 C 347 |

12 months | Nurse practitioner |

| 8 | Beaton et al. | Canada | 2017 | Secondary care | Cohort study | Fragility fracture patients (≥ 50 years; hip, humerus, forearm, spine, or pelvis fracture) |

I 147.071 C NR |

12 months | A trained coordinator |

| 9 | Danila et al. | USA | 2018 | Secondary care | RCT | Women with self-reported fracture history after age 45 years not using osteoporosis therapy |

I 1.342 C 1.342 |

18 months | NR |

| Drug regimen | |||||||||

| 10 | Stuurman-Bieze et al. | The Netherlands | 2014 | Primary care (pharmacist) | Intervention study | Patients initiating osteoporosis medication or a fixed combination with supplements |

I 495 C 442 |

12 months | Pharmacist |

| 11 | Oral et al. | Turkey and Poland | 2015 | Secondary care | Crossover RCT | Women with postmenopausal osteoporosis aged 55 to 85 years, eligible for anti-osteoporosis treatment | I/C 4481 | 26 weeks | NR |

| 12 | Tamechika et al. | Japan | 2018 | Secondary care | RCT | Systemic rheumatic diseases aged ≥ 20 years, receiving systemic glucocorticoid treatment or risedronate tablets |

I 74 C 71 |

76 weeks | NR |

| Monitoring and supervision | |||||||||

| 13 | Ducoulombier et al. | France | 2015 | Secondary care | RCT | Women aged > 50 years, a documented osteoporosis-related fracture warranting initiation of an oral anti-osteoporosis treatment |

I 79 C 85 |

12 months | Medical secretaries |

| 14 | van den Berg et al. | Netherlands | 2018 | Secondary care | RCT | Female aged ≥ 50 years attending the FLS due to a recent non-vertebral or clinical vertebral fracture. |

I 60 C 59 |

12 months | FLS nurse |

| Interdisciplinary collaboration | |||||||||

| 15 | Ganda et al. | Australia | 2014 | Primary and secondary care | RCT | Aged > 45 years and sustained a symptomatic fracture due to minimal trauma |

I 53 C 49 |

24 months | FLS staff (NS) and PCP |

I, intervention; C, control group; NR, not reported; NS, not specified

1Patients were their own control

The studied interventions, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and summarized outcomes can be found in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

The studied interventions and summarized outcomes

| Author | Intervention | Single/multicomponent Outcome | Defined as | Results | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient education and supervision | ||||||

| 1 | Roux et al. |

Intervention group one (I1) ▪ Educational material ▪ Phone calls Intervention group two (I2)l ▪ Educational material ▪ Phone calls ▪ Blood tests and BMD test prescription ▪ Extra involvement primary care physician Control ▪ Usual care |

Initiation | Initiation of osteoporosis treatment by primary care physician 12 months after a fragility fracture |

I1 vs. C OR 2.55 95% CI 1.58–4.12 I2 vs. C OR 5.07 95% CI 3.13–8.21 |

Information and follow-up by primary care physician improved treatment initiation. Additional blood tests and BMD test prescription have no statistically significant effect on treatment initiation. |

| 2 | Tüzün et al. |

Intervention group one (I1) ▪ Educational material Intervention group two (I2) ▪ Educational material ▪ Patient counseling ▪ Group meetings ▪ Phone calls Control group ▪ Not reported |

Implementation | Receiving treatment as per the instructions of the physician at regular intervals and dosages. |

I1 49.5% I2 50.5% p value 0.86 |

Active or passive training does not improve adherence to anti-osteoporosis medication. |

| Discontinuation | Continuing to receive treatment over the long term |

I1 43.8% I2 56.2% p value 0.48 |

||||

| 3 | Bianchi et al. |

Intervention group one (I1) ▪ Usual care ▪ Educational material ▪ Alarm clock ▪ Suggestions about the use of reminders Intervention group two (I2) ▪ Usual care ▪ Educational material ▪ Alarm clock ▪ Suggestions about the use of reminders ▪ Phone calls ▪ Group meetings Control group ▪ Usual care |

Implementation | The percentage of the prescribed dose taken |

I1 41% I2 48% C 49% No p value provided |

Providing information and an alarm clock or telephonic reminders and patient meetings does not improve adherence and persistence. |

| Persistence | Taking the medication 10 out of 12 months without pauses longer than 2 weeks |

I1 90% I2 85% C 92% p value 0.29 |

||||

| 4 | Cram et al. |

Intervention group one (I1) ▪ Educational brochure ▪ Provision of the test results Control group ▪ Usual care |

Adherence | Not defined |

I1 75.1% C 75.0% No p value provided |

Tailored letters providing patients with the DXA score and educational material does not improve adherence. |

| 5 | Gonneli et al. |

Intervention group one (I1) ▪ Provision of educational material Control group ▪ Usual care |

Implementation | Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS) ≥ 75% |

I1 64.2% C 58.1% No p value provided |

Providing the patients with their individual fracture risk information was not effective to improve adherence or persistence. |

| Persistence | Case reports, not specified |

I1 66.8% C 62.6% No p value provided |

||||

| 6 | Leblanc et al. |

Intervention group one (I1) ▪ Decision aid discussed during the consultation ▪ Patient counseling Intervention group two (I2) ▪ Provision of FRAX-results ▪ Patient counseling Control group ▪ Usual care |

Implementation | Percentage of days covered ≥ 80% |

I1 46.7% I2 + C 85% p value 0.08 |

Supporting both patients and clinicians during the clinical encounter with the Osteoporosis Choice decision aid does not improve treatment decision-making when compared with usual care with or without clinical decision support with FRAX results. |

| 7 | Seuffert et al. |

Intervention group one (I1) ▪ Educational material ▪ Provision of the test-results ▪ Referral to an endocrinologist when indicated Control group ▪ Usual care |

Implementation | Active treatment 12 months after initiation |

Females I1 95% C 90% p value 0.04 Males I1 97% C 82% p value 0.04 |

An educational program combined with a referral to an endocrinologist improves the treatment adherence. |

| 8 | Beaton et al. |

Intervention group one (I1) ▪ Identification of patients at risk of osteoporosis by a screening coordinator ▪ Offering education to both patient and primary care provider |

Implementation | Proportion of days covered (PDC) ≥ 50% |

I1 56.4% C 54.2% p value 0.02 |

A screening coordinator does not improve adherence. |

| Implementation | Proportion of days covered (PDC) ≥ 80% |

I1 pre intervention 59.9% Post intervention 56.4% p value 0.02 |

||||

| 9 | Danila et al. |

Intervention group one (I1) ▪ Provision of educational material containing of video material Control group ▪ Usual care |

Implementation | Self-report of current osteoporosis medication use at 6 months. |

I1 11.7% C 11.4% p value 0.83 |

A multi-modal tailored direct-to-patient video intervention does not change the adherence to anti-osteoporosis medication or testing. |

| Drug regimen combined with patient support | ||||||

| 10 | Stuurman-Bieze et al. |

Intervention group one (I1) ▪ Patient counseling ▪ Signaling of non-adherence ▪ Offering patients an alternative in case of non-adherence Control group ▪ Usual care |

Implementation | Medication possession rate ≤ 80% |

I1 96.8% C 95.0% p value 0.18 |

Counseling sessions by pharmacists did not improve implementation of osteoporosis medication. By providing tailored counseling sessions, pharmacists are able to improve non-discontinuation of anti-osteoporotic medication. |

| Discontinuation | Permanent stopping anti-osteoporosis medication |

I1 84.2% C72.2% p value < 0.01 |

||||

| 11 | Oral et al. |

Intervention group one (I1) ▪ Cross-over medication scheme Control group ▪ Usual care |

Implementation | > 50% dose taken |

I1 59.9% C 61.9% p value 0.46 |

A flexible dosing regimen can improve non-discontinuation of anti-osteoporosis medication. It does however not affect implementation. |

| Discontinuation | Continuation of treatment after 26 weeks |

I1 86.0% C 78.9% p value 0.03 |

||||

| 12 | Tamechika et al. |

Intervention group one (I1) ▪ Switching from weekly bisphosphonates to monthly minodronate Control group ▪ Usual care |

Adherence | Not defined |

I1 99.4% C 99.5% No p value provided |

Switching from weekly bisphosphonates to monthly minodronate does not improve adherence to anti-osteoporosis medication. |

| Monitoring and supervision | ||||||

| 13 | Ducoulombier et al. |

Intervention group one (I1) ▪ Phone calls ▪ Patient counseling Control group ▪ Usual care |

Implementation | Medication possession rate ≥ 80% |

I1 64.6% C 32.9% p value < 0.01 |

Telephonic follow-ups enhance patient’s implementation and non-discontinuation. |

| Discontinuation | Continuing to take a medication after 12 months |

I1 72.6% C 50.6% p value < 0.01 |

||||

| 14 | van den Berg et al. |

Intervention group one (I1) ▪ Phone calls Control group ▪ Usual care |

Persistence | Not defined |

I1 93.0% C 88.0% No p value provided |

Telephonic follow-up of osteoporosis patients does not improve persistence. |

| Interdisciplinary collaboration | ||||||

| 15 | Ganda et al. |

Intervention group one (I1) ▪ Transferring the patient to the GP after 3 months Control group ▪ Usual care |

Implementation | Medication possession rate ≥ 80% |

I1 64.0% C 61.0% p value 0.75 |

Transferring the care from the FLS clinic to the GP has no influence on implementation. |

I, intervention; C, control group; NR, not reported; NS, not specified

Table 3.

The study population and setting, inclusion and exclusion criteria and results per type of adherence

| Author | Study population and setting | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Activities and intensity of intervention | Component | Effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient education and supervision | |||||||

| 1 | Roux et al. | Patients who present themselves with a hip fracture or attending the orthopedic fracture clinic at Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke | Aged ≥ 50 years, hospitalized with a hip fracture or were seen at the orthopedic fracture clinics with a fragility fracture | Psychiatric and cognitive problems, language barriers |

I1 Information to patient and primary care physician. Follow-up calls at 6 and 12 months. 2nd intervention if not treated at 6 months I2 Extra information to patient and primary care physician. Follow-up calls at 4, 8, and 12 months. 2nd intervention if not treated at 6 months. Blood test and BMD prescription C Usual care |

Multi-component |

Initiation + |

|

Implementation NR | |||||||

|

Discontinuation NR | |||||||

|

Persistence NR | |||||||

| 2 | Tüzün et al. |

Women aged between 45 and 75, diagnosis of postmenopausal osteoporosis, eligible for osteoporosis treatment with weekly oral bisphosphonates Centre NS |

Women aged between 45 and 75 years, had a diagnosis of postmenopausal osteoporosis according to WHO criteria, and had a clinical presentation appropriate for osteoporosis treatment with weekly oral bisphosphonates | Secondary osteoporosis, receiving anti-osteoporosis treatment |

I1 Educational material (booklets osteoporosis in general, osteoporosis and exercise, osteoporosis and nutrition, osteoporosis and patient) at baseline. I2 Educational material (booklets osteoporosis in general, osteoporosis and exercise, osteoporosis and nutrition, osteoporosis and patient) at baseline. Group meetings with the topics (1) Osteoporosis in General (2), Osteoporosis and Exercise,( 3) Osteoporosis and Nutrition, and (4) Osteoporosis and Patient Rights 3, 6, 9, 12 months. Follow-up phone calls to remind patients to read the information booklets 2, 5, 8, 11 months |

Multi-component |

Initiation NR |

|

Implementation -/- | |||||||

|

Discontinuation -/- | |||||||

|

Persistence NR | |||||||

| 3 | Bianchi et al. | The study design is a multicenter, prospective, randomized study of women affected by primary post-menopausal osteoporosis, starting oral therapy. Carried out at six Italian hospital centers distributed in Northern. Central and Southern Italy |

Female aged 45–80 years, diagnosis of post-menopausal osteoporosis receiving a prescription of an oral drug for osteoporosis for the first time Possess the ability to read and understand simple educational materials and to answer simple questionnaires, availability for phone calls, and ability to come to the hospital’s outpatient clinic for meetings |

On oral therapy at beginning of the study, secondary osteoporosis, affected by other diseases requiring complex drug therapy, severe cognitive, visual, or hearing impairment |

I1 Usual care Two booklets providing information on osteoporosis and the importance of adherence to treatment. Colored memo stickers for a calendar or diary, a small alarm clock, suggestions about the use of these reminders to improve adherence to therapy I2 Similar to group one with the addition of phone calls (every 3 months) to remind patients to take the medication and invite patients to the informational group meetings (4 meetings during the 12 months) Content of the meetings were not specified C Usual care. |

Multi-component |

Initiation NR |

|

Implementation -/- | |||||||

|

Discontinuation NR | |||||||

|

Persistence -/- | |||||||

| 4 | Cram et al. | Patients presenting themselves for a DXA at three health centers, the University of Iowa. the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), and Kaiser Permanente of Georgia (KPGA) | Age ≥ 50. presenting for DXA | Age < 50, prisoners, overt cognitive disability, unable to speak or read English, deaf, no access to telephone |

I1Usual care. Mailed tailored-letter with their DXA results accompanied by an educational brochure C Usual care |

Multi-component |

Initiation NR |

|

Implementation NR | |||||||

|

Discontinuation NR | |||||||

|

Persistence NR | |||||||

| 5 | Gonnelli et al. | Osteoporotic women aged 50 years or over receiving a prescription of an oral osteoporosis medication for the first time were recruited at 34 Italian outpatient centers (Departments of Internal Medicine. Rheumatology. Rehabilitation and Geriatrics) | Women aged ≥ 50 years or over, referred as outpatients for a follow-up visit 12 months after receiving a prescription of an oral osteoporosis medication (bisphosphonates, strontium ranelate, and selective estrogen receptor modulators [SERMs]) for the first time. Osteoporosis was defined as a T-score B-2.5 at lumbar spine and/or hip evaluated by dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) according to the WHO criteria | Presence of malignancies, multiple myeloma, Paget’s disease of bone, hyperparathyroidism, history of alcohol abuse (400 g/week), severe hearing or visual impairment, cognitive problems which would prevent reliable participation to the study, and any history of fragility fractures in the last 12 months |

I1Usual care Detailed information about individual fracture risk along with a leaflet containing the absolute fracture risk value by DeFRA algorithm (group 2; n = 402) C Usual care |

Multi-component |

Initiation NR |

|

Implementation -/- | |||||||

|

Discontinuation NR | |||||||

|

Persistence -/- | |||||||

| 6 | LeBlanc et al. | Women age over 50 with a diagnosis of osteopenia or osteoporosis from participating practices (family medicine, preventive medicine, primary care internal medicine, and general internal medicine) were all affiliated to the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN, USA) | Women aged over 50, with a diagnosis of osteopenia or osteoporosis, were not taking bisphosphonates or other prescription medications to treat their condition, were identified by their clinician as potentially eligible for bisphosphonates, were available for a 6-month follow-up after randomization, and had no major learning barriers | N/R |

I1 Patients were provided a decision aid consisting their individualized 10-year risk of having a bone fracture estimated using the FRAX calculator and potential side effect of bisphosphonates I2 Clinicians providing patients their individualized 10-year risk of having a bone fracture estimated using the FRAX calculator C Usual care |

Multi-component |

Initiation NR |

|

Implementation -/- | |||||||

|

Discontinuation NR | |||||||

|

Persistence NR | |||||||

| 7 | Seuffert et al. | Patients who visit an orthopedic office NS. | Patients diagnosed with osteoporosis by DXA (T-score − 2.5 and below) or a recent fragility fracture. Presence of osteopenia was also noted (defined as a T-score between − 1.1 and − 2.5) | N/R |

I1 Educated by a nurse practitioner about the DXA results, calcium and vitamin D supplementation, provision of materials (brochures published by the National Osteoporosis Foundation) • C Usual care and a letter with the patients’ DXA score |

Multi-component |

Initiation NR |

|

Implementation + | |||||||

|

Discontinuation NR | |||||||

|

Persistence NR | |||||||

| 8 | Beaton et al. | Patients who are identified by the Fracture Clinic Screening Program (FCSP) | Fragility fracture patients. | Having a prescription filled < 12 months before the fracture | I1Identification of patients at risk of osteoporosis, educational material, intensity not specified | Multi-component |

Initiation NR |

|

Implementation -/- | |||||||

|

Discontinuation NR | |||||||

|

Persistence NR | |||||||

| 9 | Danila et al. | Patients included in the Activating Patients at Risk for OsteoPorOsiS (APRROPOS)-study. | Women aged ≥ 45 with a self-reported fracture | N/R |

I1 Educational videos emailed and sent through DVD containing an (1) introduction video explaining the reason for receiving the materials, (2) personalized videos addressing barriers to osteoporosis therapy or presenting general osteoporosis information (for those who did not rank barriers to treatment), and (3) a video on “How to communicate with your doctor about bone health” C Usual care |

Single-component |

Initiation NR |

|

Implementation -/- | |||||||

|

Discontinuation NR | |||||||

|

Persistence NR | |||||||

| Drug regimen combined with patient support | |||||||

| 10 | Stuurman-Bieze et al. | Patients initiating osteoporosis medication, recruited from 13 Dutch community pharmacies | All patients who initiated osteoporosis medication registered in the participating pharmacies between March 2006 and March 2007 | N/R |

I1 Patient counseling during the first two dispensary moments Active monitoring and signaling, 3 months after initiating medication. Non-adherent patients were intervened if warranted. C Usual pharmacy care |

Multi-component |

Initiation NR |

|

Implementation -/- | |||||||

|

Discontinuation + | |||||||

|

Persistence NR | |||||||

| 11 | Oral et al. | Women with post-menopausal osteoporosis enrolled in 10 centers in Turkey and 9 centers in Poland | Ambulatory women aged 55 to 85 years, eligible for anti-osteoporosis treatment | N/R | I1 Switching with drug regimen at 1, 2, 3, and 23 weeks to the preferred regimen | Single-component |

Initiation NR |

|

Implementation -/- | |||||||

|

Discontinuation + | |||||||

|

Persistence NR | |||||||

| 12 | Tamechika et al. | Patients with systemic rheumatic disease, aged ≥ 20, receiving systemic glucocorticoid from rheumatology clinics in Nagoya City University Hospital, Kainan Hospital, and Nagoya City West Medical Center | Systemic rheumatic disease, aged ≥ 20 receiving systemic glucocorticoid and weekly oral alendronate or risedronate tablets before screening | Taking bisphosphonates other than weekly oral alendronate or risedronate tablets previously taking parathyroid hormone analogues, denosumab, or other investigational new drugs for the treatment of osteoporosis |

I1:24 weeks bisphosphonates followed by 52 weeks minodronate C Usual care |

Single-component |

Initiation NR |

|

Implementation NR | |||||||

|

Discontinuation NR | |||||||

|

Persistence NR | |||||||

| Monitoring and supervision | |||||||

| 13 | Ducoulombier et al. | Patients attending a FLS |

Women aged ≥ 50 years A documented osteoporosis-related fracture warranting initiation of oral osteoporosis medication. |

Previously used osteoporosis medication |

I1:Two monthly phone calls lasting 10 min by medical secretaries to detect any difficulties in complying with the treatment and to remind patients to the importance of continuation the treatment as prescribed. When poor adherence was signaled, the secretary advised the patient to consult the primary care physician C Usual care |

Multi-component |

Initiation NR |

|

Implementation + | |||||||

|

Discontinuation + | |||||||

|

Persistence NR | |||||||

| 14 | van den Berg et al. | Patients attending a FLS | Females aged ≥ 50 years attending the FLS due to a recent non-vertebral or clinical vertebral fracture | Metabolic bone disorders |

I1:Phone calls in months 1, 4, and 12 to remind the patient to take the medication and to exchange views on the side effects C Usual care |

Single-component | Initiation NR |

|

Implementation NR | |||||||

|

Discontinuation NR | |||||||

| Persistence- | |||||||

| Interdisciplinary collaboration | |||||||

| 15 | Ganda et al. | Patients attending the FLS-clinic | Aged > 45 years and sustained a symptomatic fracture due to minimal trauma | Unable to provide informed consent, resided in a nursing home or hostel at the time of the incident fracture, a life expectancy < 3 years, not having a local medical practitioner, malignant or metabolic bone disease, gastrointestinal malabsorption syndromes, contra-indications to oral antiresorptive therapy |

I1:3 months visit at the FLS 21 months care by the primary care provider C Usual care of 24-month follow-up at the FLS |

Single-component |

Initiation NR |

|

Implementation -/- | |||||||

|

Discontinuation NR | |||||||

|

Persistence NR | |||||||

I, intervention; C, control group; NR, not reported; NS, not specified, -/-, no effect; +, a significant effect

Definition and measures

Measures of adherence

Adherence to prescribed medication was mentioned as an outcome in fourteen studies [21–25, 27–35]. Adherence was reported as initiation (n = 1), implementation (n = 9), and discontinuation (n = 4). In two studies, the type of adherence was not described [23, 24]. Initiation was described as initiation of osteoporosis treatment by primary care physician 12 months after a fragility fracture [29]. Implementation was described as medication possession rate (MPR) ≥ 80% [21, 22, 28, 33, 35], a medication possession rate (MPR) ≥ 50% [32, 35], per the instructions of the physician at regular intervals and dosages [30], the percentage of the prescribed dose taken [27], scoring ≥ 75% on the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS) [31], self-report of current osteoporosis medication use at 6 months [25], or active treatment 12 months after initiation [34]. Discontinuation was described as continuing to receive treatment over the long term [30], as permanently stopping anti-osteoporosis medication [33], continuation of treatment after 26 weeks [32], or continuing of medication after 1 year [22]. Persistence was mentioned as an outcome in three studies [26, 27, 31]. It was described as taking medication 10 out of 12 months without medication gaps longer than 2 weeks [27]. Two studies did not describe persistence [26, 31]. In six studies [21, 23, 25, 26, 31, 32], the effect of a single-component intervention was studied, while nine studies [22, 24, 27–30, 33–35] studied a multicomponent intervention.

Questionnaires and/or diaries (n = 8) [22, 23, 25, 27–31], and pharmacist databases (n = 3) [21, 26, 33] were the most common sources methods for data collection. Other methods included patient records (n = 1) [35], empty drug boxes (n = 1) [27], laboratory tests (n = 1) [26], collection of medication during a consultation (n = 1) [32], and retrieved from the PAADRN trial (n = 1) [24, 37]. In one study, the authors did not report the method of data collection [34].

Patient education

Nine studies assessed the effects of patient education of which were seven RCTs, one cohort study, and one observational study [24, 25, 27–31, 34, 35]. In these nine studies, adherence was used as an outcome [24, 25, 27–31, 34, 35], and in two studies, persistence was also reported [27, 31]. Interventions can further be classified into educational sessions (consisted of meetings with 4–6 patients and a psychologist) (n = 2) [27, 30], provision of educational material (n = 8) [24, 25, 27, 29–31, 34, 35], and the use of a decision aid (n = 1) [28]. Educational material varied between providing information booklets or flyers [24, 25, 27, 29–31, 34], providing DVDs with visual information regarding the intervention, (treatment of) osteoporosis, and how to discuss this with the physician [25], or a decision aid which included the personal risk on a fracture [28]. In seven studies, education was combined with counseling. The way and the intensity of patient counseling varied from offering patients advice and recommendation concerning the educational material [35] to up to four telephonic follow-up calls combined with 4 group sessions in 12 months [30].

A significant effect on medication adherence was observed in two of the nine studies, both multicomponent interventions [29, 34]. One study combining patient education, counseling, blood tests, BMD test prescription, and follow-up phone calls resulted in an increase in adherence between 40 and 53% in the intervention groups, compared with 19% in usual care and odds ratios of 2.55–5.07 [29]. When an educational program was combined with a referral to an endocrinologist for a consultation, implementation rates improved significantly compared with usual care (for females, intervention 95% vs. control 90%; for males, intervention 97% vs. control 82%; both p = 0.04) [34]. Seven studies were unable to significantly affect adherence to osteoporosis medications or provide a significance level with their results [24, 25, 27, 28, 30, 31, 35]. Albeit, of these studies, the single-component interventions included solely providing educational material [25, 31]. The multicomponent interventions included providing patients the DXA score combined with educational material [24], identification of patients at risk for osteoporosis combined with educational material [35] providing a decision aid or FRAX results combined with patient counseling [28], and the more extensive provision of educational material, an alarm clock, phone calls, and patient counseling/group meetings [27, 30]. In none of the included studies, a significantly positive effect on persistence was described.

Drug regimen

Three studies evaluated the effect of alterations in drug regimen compared with usual care. Of these studies, two were RCTs and one was an observational study [23, 32, 33]. Adherence (not further defined) was the primary outcome in one study [23], while the two other studies focused on both implementation and discontinuation [32, 33]. The studies concerned single-component interventions as either offering patients a choice of flexible dosing regimen [32] or switching to an alternative drug with longer dosing intervals [23], or multicomponent interventions of a combination of signaling of non-adherence, and offering alternative medication combined with counseling [33]. None of the studies resulted in a significant improvement of adherence/implementation. There was a significant positive effect on discontinuation in two studies. In one study, a choice of flexible dosing regimen compared with usual care resulted in 86% vs. 79% no discontinuation (p = 0.03) [32], and the combination of signaling of non-adherence with offering alternative medication combined with counseling compared with usual care led to no discontinuation 84% vs. 72% (p < 0.01) [33].

Monitoring and supervision

Monitoring and supervision was investigated in two RCT studies [22, 26]. Implementation and discontinuation to osteoporosis medications were the outcome in one study [22] and persistence in the other [26]. In both studies, patients frequently received telephone calls as a reminder to take their medication as prescribed, compared with usual care. In one study, this was a multicomponent intervention, where the phone calls were combined with patient counseling [22]. There was a positive effect on both implementation and discontinuation in one study with increased implementation rates of 65% vs. 33% (p < 0.01) and non-discontinuation rates of 73% vs. 51% (p < 0.01) in the intervention group [22]. Persistence was not significantly affected [26].

Interdisciplinary collaboration

Finally, the influence of setting of care was assessed in one RCT study, with longer term implementation of osteoporosis medications as outcome [21]. During this single-component study [21], patients, in whom anti-osteoporosis medication was initiated at the Fracture Liaison Service (FLS), were either allocated after 3 months to further follow up in the FLS (usual care) or transferred to the principal care provider (PCP). After 24 months, there was no difference between the groups in terms of implementation of anti-osteoporosis medications.

Quality assessment

The risk of bias was assessed with the RoB 2 or ROBINS-I tool [17, 18]. The overall risk of bias of the included studies varied from low to high/serious, increased risk of bias concerned missing outcome data and selection of participants. The results are presented in Appendix 2.

The quality of the three observational studies and twelve RCTs was assessed with the STROBE tool [19] and with the CONSORT tool [38], respectively. Overall, the quality of the studies was variable and moderate. The results are presented in Appendix 3. In general, the setting, eligibility criteria, and the rationale were described well in the observational studies [33–35]. However, sensitivity analysis, handling of missing data, and the sample size calculation were absent in all three studies. The sources of data for each variable fully were only described in one study [35]. The RCTs were sufficient when considering abstracts, eligibility criteria of the participants, and the statistical analysis. One study reported changes which occurred after the trial commenced [28]. None of the studies reported any harms and methods of randomization, and allocations were poorly described. Sources of funding were not reported in one study [31]. In none of the studies, the interventions or data were blinded for the patient, physician, or analyst.

There was no evident difference regarding the risk of bias or study quality, when considering the different types of interventions or between single or multicomponent interventions.

Discussion

For this updated review, 15 studies and 19 comparisons in which interventions to improve adherence and persistence to osteoporosis medications were assessed. Interventions included patient education, monitoring and supervision, change in drug regimen combined with patient support, and interdisciplinary collaboration.

Different approaches for patient education (combined with counseling) were the most studied interventions, but the effect on adherence was limited. Only two out of nine studies reported significant improvements on implementation and discontinuation [29, 34], and none of the interventions reported a positive effect on persistence. Change in drug regimen, combined with patient support [23, 32, 33], did not result in a positive effect on implementation. Furthermore, a significantly positive effect on discontinuation to osteoporosis medications was sorted when patients were offered a choice of flexible dosing regime and a combination of signaling of non-adherence with offering alternative medication combined with counseling. There was a notable difference in patient participation and involvement; if the patient was counseled or offered participation in the choice regarding the decision concerning drug regimen, there was an improvement in no discontinuation [32, 33], in contrast to no improvement in adherence when the patient was not involved [23]. This implicates that patient involvement is an important factor to improve medication persistence while employing flexible dosing regimen. Also, since there was no effect on implementation, but an effect on discontinuation, it seems change in drug regimen is only useful for patients already using osteoporosis medications. Monitoring and supervision were shown to have a positive effect on both implementation and discontinuation, but only in one study. In this study, patients were offered counseling, and not solely monitored or supervised [22]. Finally, there was no difference in terms of persistence to osteoporosis medications when patients were either allocated to the regular FLS for 24 months (usual care) or transferred to the principal care provider (PCP) after 3 months for a follow-up of 21 months [21]. Although this did not lead to an improvement in medication persistence, it also did not lead to a decrease. This implicates that the role of the rheumatologist can partially be replaced by other physicians making the treatment more flexible.

Compared with the previous SLR, there was a notable difference in interventions; in the included articles for this review, there was more emphasis on patient involvement, counseling, and shared decision-making, hence multicomponent interventions, instead of solely patient information/education or supervision each (single component intervention), and there was a larger variation of healthcare professionals involved in conduction of these interventions. Earlier studies described that patient education had the potential to increase adherence, but new research published since the previous SLR could not confirm this, despite some reasonable effect size, and the effect of solely patient education seems limited [39–41]. Improvement is only expected when it is combined with counseling. Similarities are found when comparing strategies in other chronic diseases, as diabetes; education is seen as the cornerstone which is integrated in each intervention strategy combined with involvement of the healthcare provider and patient, a so-called combined educational-behavioral strategy [42]. Compared with the previous SLR, an improvement in the quality of studies is observed. Of the fifteen included studies, the majority were randomized controlled trials, mostly of reasonable quality. However, there was heterogeneity in methodology and (reporting of) results, similar to the previous SLR. Risk of bias was variable, from low to high/serious. As in the previous SLR, almost all studies used adherence as outcome, and persistence was less frequently used. The definitions which were used for adherence and persistence still varied greatly; for instance, we found twelve different descriptions of adherence. These findings show that the taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications by Vrijens et al. is not fully implemented yet [16], as was also concluded in the previous SLR.

There was an effect of a change in drug regimen, as reported in earlier studies, in which flexible dosing regimens were effective in increasing adherence, regardless of the level of patient involvement [10]. However, multicomponent interventions, where a change of drug regimen is combined with counseling, also led to an increase of no discontinuation levels. In the field of neurology, especially migraine/chronic headache, it is emphasized that drug regimens concerning preventive medication should be tailored to lifestyle, to increase adherence, thus also focusing on multicomponent intervention [43].

Interdisciplinary collaboration was described successful when improving adherence in other studies within the field of osteoporosis or in other diseases [44, 45], contrary to our findings. However, to lift the burden on medical specialists, interdisciplinary collaboration could be of added value, since there was no decrease of persistence either [46–48].

The currently available data on adherence and persistence to osteoporosis medications have several limitations. First, the available data was mostly self-reported, introducing social desirability and recall bias, or may not be true values due to the use of prescription data and time until last prescription refill [6]. In addition, this resulted also in an increased risk of bias of missing outcome data.

Second, in none of the studies, the intervention or data were blinded for the patient, physician, or analyst. While this is not always possible, especially for patients, it could result in confirmation bias and selection bias. Third, the follow-up time was limited to a maximum of 24 months; hence, osteoporosis is a chronic disease; this could be of influence on the long-term results of adherence and persistence.

There were strengths and potential issues in relation to the methodology and execution of this review. The search was designed with the help of an expert library specialist. Article selection, data extraction, and quality appraisal were conducted by at least two researchers. Furthermore, the review was executed in accordance with the PRISMA statement. Although we found 15 new adherence intervention studies, the conclusions on adherence interventions remain blurred, and still no clear recommendations regarding interventions to improve medication adherence and persistence can be derived from our review. Moreover, we recognized the same limitations with regard to quality and thus interpretation, comparison, or meta-analyses. In other words, we confirmed variability in definition and measurement of adherence outcome, challenges to classify adherence interventions, and limitations in design related to blinding of patients and/or physicians, sensitivity analysis, handling of missing data, and often sample calculations. Notwithstanding, we feel our review does provide added value by pointing to the direction on which future research should focus, namely, multicomponent interventions with active patient involvement.

With regard to the classification of interventions into four categories, non-homogenous groups are possibly not comparable with other studies/reviews. The ABC taxonomy by Vrijens et al. [16] was used for organizing and comparing data for this review, resulting in the use of the terms adherence, subdivided in initiation, implementation and discontinuation, and persistence, which sometimes differed compared with the terms used in the original articles. Also, the influence of the health system (e.g., co-payments, reimbursement, and difference in primary and secondary care), which differs per country, was not considered [9]. In a recent ESCEO paper, different recommendations to improve medication adherence and persistence were drafted by an international working group [12]. These include patient education and counseling, improving patient interaction and shared-decision making, and dose simplification such as the use of gastro-resistant risedronate tablets that could be taken after breakfast. In addition, the ESCEO working group recognized the need for more evidence and high-quality research and provides recommendations for further research in the field.

In conclusion, this updated review suggests that improving adherence and persistence to osteoporosis medications remains a complex and challenging issue, and no clear recommendations can unfortunately be derived from it. Patient education, monitoring and supervision, change in drug regimen combined with patient support, and interdisciplinary collaboration were shown to have some effect on either adherence or persistence but only in some of the studies. However, interestingly, multicomponent interventions with active patient involvement were the most effective interventions when aiming to increase adherence and/or persistence to osteoporosis medications. It would thus be important to design appropriate multicomponent interventions and to critically evaluate them with means of well-designed randomized controlled trials, ideally with longer follow-up.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Vera Meeda for her assistance in quality evaluation of the studies, and Mr. Gregor Franssen and Mr. Stefan Jongen, medical information specialists at Maastricht University library, for their assistance in optimizing the search strategy.

Appendix 1

Pubmed

"Osteoporosis"[Mesh] OR Osteoporosis [tiab] OR "Bone Diseases, Metabolic"[Mesh] OR

Metabolic Bone Disease*[tiab] OR "Bone Demineralization, Pathologic"[Mesh] OR Bone

Demineralization[tiab] OR "Decalcification, pathologic"[MeSH Terms] OR Patholog*

Decalcification*[tiab] OR "Bone Density"[Mesh] OR Bone Densit*[Tiab]

AND

"Guideline adherence"[MeSH Terms] OR Guideline adherence*[tiab] OR "Patient

Satisfaction"[Mesh] OR Patient Satisfaction[tiab] OR "Patient Preference"[Mesh] OR Patient

Preference*[tiab] OR "Attitude to Health"[Mesh] OR Health attitude*[tiab] OR "Health

Knowledge, Attitudes Practice"[Mesh] OR "Treatment Adherence and Compliance"[Mesh] OR

Treatment Adherence [tiab] OR Therapeutic adherence [tiab] OR “Treatment compliance”[tiab]

OR “Therapeutic compliance”[tiab] OR "Patient Acceptance of Health Care"[Mesh] OR "Patient

Acceptance of Health Care"[tiab] OR "Patient Dropouts"[Mesh] OR "Patient dropout*"[tiab] OR

"Patient Participation"[Mesh] OR "Patient Participation"[tiab] OR "Patient Compliance"[Mesh]

OR Patient Compliance [tiab] OR Patient engagement [tiab] OR Patient Acceptance [tiab] OR

Patient involvement [tiab] OR Medication adherence [tiab] OR Medication persistence [tiab] OR

Medication compliance [tiab]

Embase

*metabolic bone disease/ or *bone disease/ or *bone demineralization/ or *osteoporosis/ or

*bone demineralization/

01-07-2012 t/m 31-12-2018

AND

*disease management/ or patient attitude/ or *attitude/ or *health care quality/ or *human

relation/ or *patient attendance/ or *patient compliance/ or *patient dropout/ or *patient

participation/ or *patient preference/ or *patient satisfaction/ or *refusal to participate/ or

*treatment interruption/ or *treatment refusal/ or *protocol compliance/ or *attitude to

health/ or *attitude/ or *health behavior/ or *knowledge/ or *attitude to illness/ or *health

behavior/ or *behavior/ or *medication compliance/ or *patient education/ or *health

education/

2012-2018

PSYCHINFO

(MM "Treatment Compliance" OR (MM "Compliance" OR MM "Treatment Compliance" OR MM

"Client Attitudes" OR MM "Health Attitudes" OR MM "Health Behavior" OR MM "Health Care

Utilization" OR MM "Health Education" OR MM "Health Knowledge" OR MM "Health Literacy"

OR MM "Client Education" OR MM "Client Satisfaction" OR MM "Client Participation" OR MM

"Client Attitudes" OR MM "Treatment Refusal")

AND

(MM "Osteoporosis") OR (MM "Bone Disorders")

01-07-2012 t/m 31-12-2018

Cinahl

(MM "Guideline Adherence") OR (MM "Medication Compliance") OR (MM "Patient

Compliance") OR (MM "Compliance with Medication Regimen (Saba CCC)") OR (MM

"Compliance with Therapeutic Regimen (Saba CCC)") OR (MM "Compliance with Medical

Regimen (Saba CCC)") OR (MM "Patient Satisfaction") OR (MM "Attitude to Illness") OR (MM

"Attitude to Medical Treatment") OR (MM "Attitude to Health") OR (MM "Patient Attitudes")

OR (MM "Knowledge: Health Behaviors (Iowa NOC)") OR (MM "Knowledge") OR (MM "Health

Knowledge") OR (MM "Acceptance and Commitment Therapy") OR (MM "Patient Dropouts")

AND

(MM "Osteoporosis")

01-07-2012 t/m 31-12-2018

Appendix 2

Table 4.

Risk of bias (Revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2))

| Author | Roux | Tüzün | Bianchi | Cram | Gonnelli | LeBlanc | Danila | Oral | Tamechika | Ducoulombier | van den Berg | Ganda |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk of Bias | ||||||||||||

|

Domain 1: Risk of bias arising from the randomization process |

Low | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | High | Low |

|

Domain 2: Risk of bias due to deviations from the intended interventions (effect of adhering to intervention) |

Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

|

Domain 3: Missing outcome data |

Low | High | High | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | High | Low |

|

Domain 4: Risk of bias in measurement of the outcome |

Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

|

Domain 5: Risk of bias in selection of the reported result |

Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Low |

| Overall risk of bias | Low | High | High | Low | Some concerns | High | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | High | Low |

Table 5.

Risk of bias (the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies - of Interventions (ROBINS-I) assessment tool)

| Author | Seuffert | Beaton | Stuurman-Bieze |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk of Bias | |||

| Bias due to confounding | Low | Low | Low |

| Bias in selection of participants into the study | Low | Low | Serious |

| Bias in classification of interventions | Low | Low | Serious |

| Bias due to deviations from intended interventions | Low | Low | Low |

| Bias due to missing data | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Bias in measurement of outcomes | Low | Low | Low |

| Bias in selection of the reported result | Low | Low | Low |

| Overall risk of bias | Moderate | Moderate | Serious |

Appendix 3

Table 6.

Quality of the selected studies

| Consort checklist | Articles | |||

| Consort Item | Roux | Tuzun | Bianchi | |

| Title and abstract | ||||

| 1a | Identification as a randomized trial in the title | - | + | - |

| 1b | Structured summary of trial design, methods, results, and conclusions. | + | + | + |

| Introduction | ||||

| 2a | Scientific background and explanation of rationale | + | + | + |

| 2b | Specific objectives or hypotheses | + | + | + |

| Methods | ||||

| 3a | Description of trial design (such as parallel, factorial) including allocation ratio | + | + | + |

| 3b | Important changes to methods after trial commencement (such as eligibility criteria), with reasons | - | - | +/- |

| 4a | Eligibility criteria for participants | + | + | + |

| 4b | Settings and locations where the data were collected | + | +/- | + |

| 5 | The interventions for each group with sufficient details to allow replication, including how and when they were actually administered | + | + | + |

| 6a | Completely defined pre-specified primary and secondary outcome measures, including how and when they were assessed] | + | + | + |

| 6b | Any changes to trial outcomes after the trial commenced, with reasons | - | N/a | N/a |

| 7a | How sample size was determined | + | - | - |

| 7b | When applicable, explanation of any interim analyses and stopping guidelines | - | - | N/A |

| 8a | Method used to generate the random allocation sequence | - | + | + |

| 8b | Type of randomization; details of any restriction (such as blocking and block size) | - | + | + |

| 9 | Mechanism used to implement the random allocation sequence (such as sequentially numbered containers), describing any steps taken to conceal the sequence until interventions were assigned | - | + | +/- |

| 10 | Who generated the random allocation sequence, who enrolled participants, and who assigned participants to interventions | - | - | - |

| 11a | If done, who was blinded after assignment to interventions (for example, participants, care providers, those assessing outcomes) and how | - | - | N/a |

| 11b | If relevant, description of the similarity of interventions | + | + | + |

| 12a | Statistical methods used to compare groups for primary and secondary outcomes | + | + | + |

| 12b | Methods for additional analyses, such as subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses | - | - | + |

| Results | ||||

| 13a | For each group, the numbers of participants who were randomly assigned, received intended treatment, and were analyzed for the primary outcome | + | + | + |

| 13b | For each group, losses and exclusions after randomization, together with reasons | - | - | - |

| 14a | Dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up | + | - | - |

| 14b | Why the trial ended or was stopped | - | - | - |

| 15 | A table showing baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for each group | - | + | +/- |

| 16 | For each group, number of participants (denominator) included in each analysis and whether the analysis was by original assigned groups | + | + | - |

| 17a | For each primary and secondary outcome, results for each group, and the estimated effect size and its precision (such as 95% confidence interval) | + | + | +/- |

| 17b | For binary outcomes, presentation of both absolute and relative effect sizes is recommended | + | + | - |

| 18 | Results of any other analyses performed, including subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses, distinguishing pre-specified from exploratory | - | - | N/a |

| 19 | All important harms or unintended effects in each group (for specific guidance see CONSORT for harms) | - | - | - |

| Discussion | ||||

| 20 | Trial limitations, addressing sources of potential bias, imprecision, and, if relevant, multiplicity of analyses | + | + | +/- |

| 21 | Generalisability (external validity, applicability) of the trial findings | + | +/- | +/- |

| 22 | Interpretation consistent with results, balancing benefits and harms, and considering other relevant evidence | + | + | +/- |

| Other information | ||||

| 23 | Registration number and name of trial registry | + | - | + |

| 24 | Where the full trial protocol can be accessed, if available | + | - | + |

| 25 | Sources of funding and other support (such as supply of drugs), role of funders | + | + | + |

| Consort checklist | Articles | |||

| Consort Item | Cram | Gonelli | Leblanc | |

| Title and abstract | ||||

| 1a | Identification as a randomized trial in the title | + | - | + |

| 1b | Structured summary of trial design, methods, results, and conclusions. | + | + | + |

| Introduction | ||||

| 2a | Scientific background and explanation of rationale | + | + | + |

| 2b | Specific objectives or hypotheses | + | + | + |

| Methods | ||||

| 3a | Description of trial design (such as parallel, factorial) including allocation ratio | + | + | + |

| 3b | Important changes to methods after trial commencement (such as eligibility criteria), with reasons | N/a | - | - |

| 4a | Eligibility criteria for participants | + | + | +/- |

| 4b | Settings and locations where the data were collected | + | +/- | + |

| 5 | The interventions for each group with sufficient details to allow replication, including how and when they were actually administered | + | -/+ | + |

| 6a | Completely defined pre-specified primary and secondary outcome measures, including how and when they were assessed] | + | + | + |

| 6b | Any changes to trial outcomes after the trial commenced, with reasons | N/a | N/a | N/a |

| 7a | How sample size was determined | + | - | _ |

| 7b | When applicable, explanation of any interim analyses and stopping guidelines | N/a | - | - |

| 8a | Method used to generate the random allocation sequence | + | - | + |

| 8b | Type of randomization; details of any restriction (such as blocking and block size) | + | - | + |

| 9 | Mechanism used to implement the random allocation sequence (such as sequentially numbered containers), describing any steps taken to conceal the sequence until interventions were assigned | + | - | + |

| 10 | Who generated the random allocation sequence, who enrolled participants, and who assigned participants to interventions | +/- | - | - |

| 11a | If done, who was blinded after assignment to interventions (for example, participants, care providers, those assessing outcomes) and how | + | - | + |

| 11b | If relevant, description of the similarity of interventions | N/a | + | + |

| 12a | Statistical methods used to compare groups for primary and secondary outcomes | + | + | + |

| 12b | Methods for additional analyses, such as subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses | - | - | - |

| Results | ||||

| 13a | For each group, the numbers of participants who were randomly assigned, received intended treatment, and were analyzed for the primary outcome | + | + | + |

| 13b | For each group, losses and exclusions after randomization, together with reasons | +/- | - | + |

| 14a | Dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up | - | +/- | + |

| 14b | Why the trial ended or was stopped | - | - | - |

| 15 | A table showing baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for each group | + | - | - |

| 16 | For each group, number of participants (denominator) included in each analysis and whether the analysis was by original assigned groups | +/1 | + | + |

| 17a | For each primary and secondary outcome, results for each group, and the estimated effect size and its precision (such as 95% confidence interval) | - | + | + |

| 17b | For binary outcomes, presentation of both absolute and relative effect sizes is recommended | N/a | + | + |

| 18 | Results of any other analyses performed, including subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses, distinguishing pre-specified from exploratory | N/a | - | - |

| 19 | All important harms or unintended effects in each group (for specific guidance see CONSORT for harms) | - | - | - |

| Discussion | ||||

| 20 | Trial limitations, addressing sources of potential bias, imprecision, and, if relevant, multiplicity of analyses | + | + | + |

| 21 | Generalisability (external validity, applicability) of the trial findings | +/- | + | + |

| 22 | Interpretation consistent with results, balancing benefits and harms, and considering other relevant evidence | + | + | + |

| Other information | ||||

| 23 | Registration number and name of trial registry | + | - | + |

| 24 | Where the full trial protocol can be accessed, if available | + | - | + |

| 25 | Sources of funding and other support (such as supply of drugs), role of funders | + | - | + |

| Consort checklist | Articles | |||

| Consort Item | Danila | Stuurman-Bieze | Oral | |

| Title and abstract | ||||

| 1a | Identification as a randomized trial in the title | + | - | +/- |

| 1b | Structured summary of trial design, methods, results, and conclusions. | + | + | + |

| Introduction | ||||

| 2a | Scientific background and explanation of rationale | + | +/- | + |

| 2b | Specific objectives or hypotheses | + | + | + |

| Methods | ||||

| 3a | Description of trial design (such as parallel, factorial) including allocation ratio | + | + | + |

| 3b | Important changes to methods after trial commencement (such as eligibility criteria), with reasons | N/a | N/a | N/a |

| 4a | Eligibility criteria for participants | + | + | + |

| 4b | Settings and locations where the data were collected | + | + | +/- |

| 5 | The interventions for each group with sufficient details to allow replication, including how and when they were actually administered | + | +/- | + |

| 6a | Completely defined pre-specified primary and secondary outcome measures, including how and when they were assessed] | + | + | +/- |

| 6b | Any changes to trial outcomes after the trial commenced, with reasons | N/a | N/a | N/a |

| 7a | How sample size was determined | + | - | - |

| 7b | When applicable, explanation of any interim analyses and stopping guidelines | - | N/a | N/a |

| 8a | Method used to generate the random allocation sequence | + | - | + |

| 8b | Type of randomization; details of any restriction (such as blocking and block size) | + | - | + |

| 9 | Mechanism used to implement the random allocation sequence (such as sequentially numbered containers), describing any steps taken to conceal the sequence until interventions were assigned | + | - | - |

| 10 | Who generated the random allocation sequence, who enrolled participants, and who assigned participants to interventions | + | - | +/- |

| 11a | If done, who was blinded after assignment to interventions (for example, participants, care providers, those assessing outcomes) and how | + | N/a | N/a |

| 11b | If relevant, description of the similarity of interventions | + | N/a | N/a |

| 12a | Statistical methods used to compare groups for primary and secondary outcomes | + | + | + |

| 12b | Methods for additional analyses, such as subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses | + | - | - |

| Results | ||||

| 13a | For each group, the numbers of participants who were randomly assigned, received intended treatment, and were analyzed for the primary outcome | + | + | + |

| 13b | For each group, losses and exclusions after randomization, together with reasons | + | + | + |

| 14a | Dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up | + | + | - |

| 14b | Why the trial ended or was stopped | N/a | + | - |

| 15 | A table showing baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for each group | + | + | - |

| 16 | For each group, number of participants (denominator) included in each analysis and whether the analysis was by original assigned groups | + | - | - |

| 17a | For each primary and secondary outcome, results for each group, and the estimated effect size and its precision (such as 95% confidence interval) | + | + | + |

| 17b | For binary outcomes, presentation of both absolute and relative effect sizes is recommended | + | + | + |

| 18 | Results of any other analyses performed, including subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses, distinguishing pre-specified from exploratory | + | N/a | - |

| 19 | All important harms or unintended effects in each group (for specific guidance see CONSORT for harms) | - | - | - |

| Discussion | ||||

| 20 | Trial limitations, addressing sources of potential bias, imprecision, and, if relevant, multiplicity of analyses | + | +/- | +/- |

| 21 | Generalisability (external validity, applicability) of the trial findings | - | + | +/- |

| 22 | Interpretation consistent with results, balancing benefits and harms, and considering other relevant evidence | + | + | + |

| Other information | ||||

| 23 | Registration number and name of trial registry | + | - | - |

| 24 | Where the full trial protocol can be accessed, if available | + | - | - |

| 25 | Sources of funding and other support (such as supply of drugs), role of funders | + | + | + |

| Consort checklist | Articles | |||

| Consort Item | Tamechika | Ducolombier | ||

| Title and abstract | ||||

| 1a | Identification as a randomized trial in the title | + | - | |

| 1b | Structured summary of trial design, methods, results, and conclusions. | + | + | |

| Introduction | ||||

| 2a | Scientific background and explanation of rationale | + | +/- | |

| 2b | Specific objectives or hypotheses | + | + | |

| Methods | ||||

| 3a | Description of trial design (such as parallel, factorial) including allocation ratio | + | - | |

| 3b | Important changes to methods after trial commencement (such as eligibility criteria), with reasons | - | N/a | |

| 4a | Eligibility criteria for participants | + | + | |

| 4b | Settings and locations where the data were collected | + | +/- | |

| 5 | The interventions for each group with sufficient details to allow replication, including how and when they were actually administered | + | + | |

| 6a | Completely defined pre-specified primary and secondary outcome measures, including how and when they were assessed] | + | + | |

| 6b | Any changes to trial outcomes after the trial commenced, with reasons | - | N/a | |

| 7a | How sample size was determined | + | + | |

| 7b | When applicable, explanation of any interim analyses and stopping guidelines | - | N/a | |

| 8a | Method used to generate the random allocation sequence | - | - | |

| 8b | Type of randomization; details of any restriction (such as blocking and block size) | - | - | |

| 9 | Mechanism used to implement the random allocation sequence (such as sequentially numbered containers), describing any steps taken to conceal the sequence until interventions were assigned | - | - | |

| 10 | Who generated the random allocation sequence, who enrolled participants, and who assigned participants to interventions | - | - | |

| 11a | If done, who was blinded after assignment to interventions (for example, participants, care providers, those assessing outcomes) and how | - | N/a | |

| 11b | If relevant, description of the similarity of interventions | + | N/a | |

| 12a | Statistical methods used to compare groups for primary and secondary outcomes | + | + | |

| 12b | Methods for additional analyses, such as subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses | - | - | |

| Results | ||||

| 13a | For each group, the numbers of participants who were randomly assigned, received intended treatment, and were analysed for the primary outcome | + | + | |

| 13b | For each group, losses and exclusions after randomisation, together with reasons | +/- | +/- | |

| 14a | Dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up | + | - | |

| 14b | Why the trial ended or was stopped | - | - | |

| 15 | A table showing baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for each group | - | + | |

| 16 | For each group, number of participants (denominator) included in each analysis and whether the analysis was by original assigned groups | + | - | |

| 17a | For each primary and secondary outcome, results for each group, and the estimated effect size and its precision (such as 95% confidence interval) | + | + | |

| 17b | For binary outcomes, presentation of both absolute and relative effect sizes is recommended | + | + | |

| 18 | Results of any other analyses performed, including subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses, distinguishing pre-specified from exploratory | - | - | |

| 19 | All important harms or unintended effects in each group (for specific guidance see CONSORT for harms) | - | - | |

| Discussion | ||||

| 20 | Trial limitations, addressing sources of potential bias, imprecision, and, if relevant, multiplicity of analyses | + | + | |

| 21 | Generalisability (external validity, applicability) of the trial findings | + | + | |

| 22 | Interpretation consistent with results, balancing benefits and harms, and considering other relevant evidence | + | + | |

| Other information | ||||

| 23 | Registration number and name of trial registry | + | - | |

| 24 | Where the full trial protocol can be accessed, if available | + | - | |

| 25 | Sources of funding and other support (such as supply of drugs), role of funders | + | + | |

| Strobe checklist | Articles | |||

| Strobe item | Beaton | Seuffert | ||

| Title and abstract | ||||

| 1a | Indicate the study’s design with a commonly used term in the title or the abstract | + | + | |

| 1b | Provide in the abstract an informative and balanced summary of what was done and what was found | + | + | |

| Introduction | ||||

| 2 | Explain the scientific background and rationale for the investigation being reported | + | + | |

| 3 | State specific objectives, including any pre-specified hypotheses | +/- | +/- | |

| Methods | ||||

| 4 | Present key elements of study design early in the paper | + | + | |