Abstract

Antibiotic‐tolerant persisters are often implicated in treatment failure of chronic and relapsing bacterial infections, but the underlying molecular mechanisms have remained elusive. Controversies revolve around the relative contribution of specific genetic switches called toxin–antitoxin (TA) modules and global modulation of cellular core functions such as slow growth. Previous studies on uropathogenic Escherichia coli observed impaired persister formation for mutants lacking the pasTI locus that had been proposed to encode a TA module. Here, we show that pasTI is not a TA module and that the supposed toxin PasT is instead the bacterial homolog of mitochondrial protein Coq10 that enables the functionality of the respiratory electron carrier ubiquinone as a “lipid chaperone.” Consistently, pasTI mutants show pleiotropic phenotypes linked to defective electron transport such as decreased membrane potential and increased sensitivity to oxidative stress. We link impaired persister formation of pasTI mutants to a global distortion of cellular stress responses due to defective respiration. Remarkably, the ectopic expression of human coq10 largely complements the respiratory defects and decreased persister levels of pasTI mutants. Our work suggests that PasT/Coq10 has a central role in respiratory electron transport that is conserved from bacteria to humans and sustains bacterial tolerance to antibiotics.

Keywords: antibiotic tolerance, electron transport chain, persistence, toxin–antitoxin, ubiquinone, uropathogenic Escherichia coli

Previous work on antibiotic‐tolerant persisters of pathogenic Escherichia coli highlighted the role of PasT, described as a toxin of a toxin–antitoxin system, in their resilience. Here, we show that PasT is not a toxin but rather the bacterial homolog of mitochondrial Coq10 that guides the electron carrier ubiquinone in respiratory electron transport. Consistently, pasT mutants of pathogenic E. coli and Salmonella Typhimurium show pleiotropic phenotypes of defective respiration including impaired persister formation that can largely be complemented by human Coq10.

1. INTRODUCTION

Bacterial persisters are cells that transiently display antibiotic tolerance due to a dormant physiology and constitute a subpopulation of cells within the overall bacterial population (Balaban et al., 2019). This phenomenon has been linked to treatment failure of chronic and relapsing infections in different clinical settings (Fauvart, De Groote, & Michiels, 2011; Harms, Maisonneuve, & Gerdes, 2016; Lewis, 2010). One common example is urinary tract infections (UTIs) that often relapse and are frequently caused by uropathogenic strains of Escherichia coli (UPEC) (Flores‐Mireles, Walker, Caparon, & Hultgren, 2015). These bacteria are thought to persist during antibiotic treatment in rectal reservoirs and intracellular biofilms, and the survival of UPECs isolated from recurrent UTIs was shown to correlate with higher levels of persister cells detectable in the population (Anderson et al., 2003; Blango & Mulvey, 2010; Glover, Moreira, Sperandio, & Zimmern, 2014; Goneau et al., 2014).

Although persister cells are ubiquitous and their formation and evolution have been studied in multiple human pathogens (Michiels, Van den Bergh, Verstraeten, Fauvart, & Michiels, 2016), the molecular mechanisms underlying their antibiotic tolerance have remained largely elusive. Mechanistic studies have been performed primarily in laboratory model strains like E. coli K‐12 where multiple different pathways of persister cell formation have been described (Harms et al., 2016; Lewis, 2010). Among these, the dormant physiology of persister cells has been linked repeatedly to the reversible activation of toxin–antitoxin (TA) systems in different strains of E. coli as well as closely related Salmonella Typhimurium (Dörr, Vulic, & Lewis, 2010; Harms et al., 2016; Helaine et al., 2014; Norton & Mulvey, 2012; Verstraeten et al., 2015). TA systems are composed of a toxin protein that can inhibit key cellular processes and a cognate antitoxin that represses the toxin's activity until it is degraded in response to cellular signaling (Harms, Brodersen, Mitarai, & Gerdes, 2018). They can therefore act as genetically controlled switches to reversibly shut down bacterial growth, and as such, it is generally intuitive that TA systems might be well suited to control persister cell formation, survival, and resuscitation (Ronneau & Helaine, 2019). However, the relative importance of specific factors such as TA systems has remained controversial compared to global changes via modulation of the cellular core machinery including electron transport or ATP synthesis (Goneau et al., 2014; Goormaghtigh et al., 2018; Harms et al., 2016; Pontes & Groisman, 2019; Shan et al., 2017). We previously discovered that a once well‐established link between ten particular TA systems of E. coli K‐12 and persister formation is wrong (Goormaghtigh et al., 2018; Harms, Fino, Sørensen, Semsey, & Gerdes, 2017), and the link between TA systems and persister formation in Salmonella Typhimurium has also recently been disputed (Pontes & Groisman, 2019).

Given these debates, we became interested in a study that found the pasTI TA module of UPEC strain CFT073 to be critical for antibiotic‐tolerant persister cells (Norton & Mulvey, 2012). Remarkably, the orthologous system in E. coli K‐12, ratAB, seemed to play no role in persister formation under the same conditions. However, the molecular basis of PasTI‐dependent drug tolerance in UPECs remained unclear. Previous work had proposed that the RatA toxin of E. coli K‐12 is a translation inhibitor that interferes with 70S ribosome assembly but did not experimentally confirm the role of RatB as the cognate antitoxin, questioning the notion that RatAB/PasTI is indeed a TA system (Zhang & Inouye, 2011).

In this study, we therefore aimed at uncovering the molecular activity and biological function of PasTI/RatAB in E. coli to shed more light on the role of this TA system in persister formation and persister cells in clinical contexts. While we readily reproduced that PasT is critical for the formation or survival of ciprofloxacin‐tolerant cells by E. coli CFT073 and other pathogenic enterobacteria, we could not confirm that PasTI is a TA system. Instead, we show that PasT is the bacterial homolog of mitochondrial protein Coq10 that acts as an important accessory factor in the ubiquinone‐dependent electron transport chain (ETC). We find that E. coli mutants lacking pasT display the same pleiotropic phenotypes as yeast coq10 mutants including decreased membrane potential, increased sensitivity to oxidative stress, and modestly decreased ubiquinone biosynthesis. Remarkably, these signs of defective respiration in E. coli can be complemented by ectopic expression of human coq10, suggesting that PasT and Coq10 are functionally equivalent. We therefore conclude that PasT is a previously unrecognized player in bacterial respiratory electron transport and likely affects antibiotic tolerance indirectly via its roles in redox balance and/or energy metabolism.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Bacterial handling and culturing

Escherichia coli was routinely cultured in LB or M9 liquid medium at 37°C in glass culture tubes or Erlenmeyer flasks with agitation at 160 rpm, usually in a water bath shaker for physiological experiments. LB agar plates were routinely used as a solid medium. Selection for plasmid maintenance was performed with ampicillin at 30 µg/ml (mini‐R1 origin of replication) or 100 µg/ml (other origins of replication), chloramphenicol at 25 µg/ml, and kanamycin at 25 µg/ml. Plac was induced with 1 mM of isopropyl β‐d‐1‐thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), while ParaB was induced with 0.2% w/v of l‐arabinose. Whenever appropriate, liquid and solid media were supplemented with 1% w/v d‐glucose to reduce basal expression of both Plac and ParaB promoters through catabolite repression. Unless indicated differently, the complementation of bacterial mutants with E. coli genes was performed using low‐copy plasmids (pNDM220 derivatives) carrying these genes including their own promoter, so that no ectopic induction of the constructs was necessary. When enforced expression was required (e.g., for the experiments shown in Figure 1 and Figure A6f in Appendix 2) or to test heterologous complementation with distant homologs (e.g., Figure 8), isogenic plasmids encoding genes without their endogenous promoters were used and the bacteria were continuously cultured in the presence of 1 mM of IPTG in overnight cultures and throughout the experiment to induce expression from the Plac promoter of pNDM220 derivatives (see all plasmids listed in Table A2 in Appendix 1).

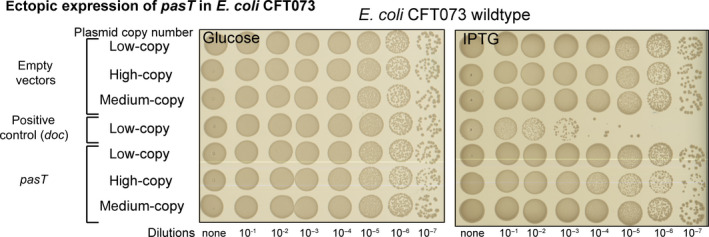

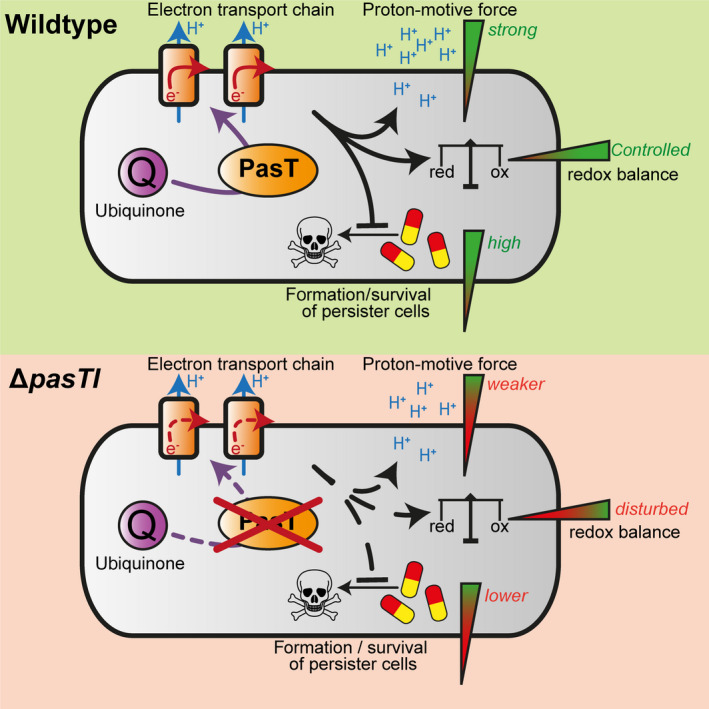

FIGURE 1.

PasT does not inhibit bacterial growth. Spot assay of E. coli CFT073 harboring isogenic plasmids with different copy number encoding either pasT or the well‐studied TA module toxin doc (as positive control) under the control of a Plac promoter on LB agar plates containing 1 mM isopropyl β‐d‐1‐thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and repressed on LB agar plates containing 1% w/v d‐glucose (see details in Materials and Methods). Similar results were obtained for pasT expression in E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI, E. coli K‐12 MG1655, and E. coli K‐12 MG1655 ΔratAB (Figure A1a/b in Appendix 2). No growth inhibition was also observed for the expression of pasI (Figure A1c in Appendix 2).

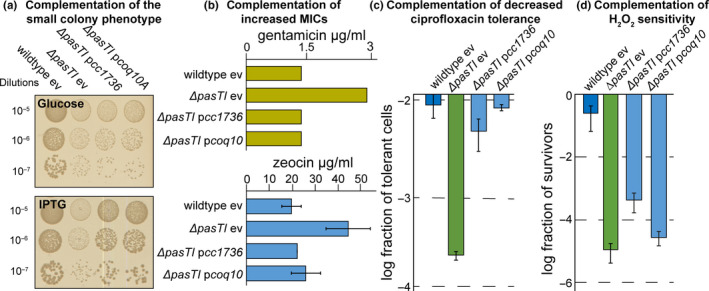

FIGURE 8.

CC1736 of Caulobacter crescentus and human mitochondrial Coq10 can functionally complement the E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI mutant. (a) The colony sizes of E. coli CFT073 strain harboring the empty vector (ev) or complementation plasmids encoding pasT homolog cc1736 from C. crescentus or human coq10 under Plac control were analyzed on LB agar plates supplemented with 1% d‐glucose (repressing expression of complementation constructs) or 1 mM IPTG (inducing expression of complementation plasmids). Similar results were obtained with E. coli K‐12 MG1655 ΔratAB (Figure A6f in Appendix 2). (b) Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of these strains for gentamicin (top) and zeocin (bottom) was determined via broth dilution assays. For gentamicin, results of one representative experiment are presented; additional independent replicates and similar data obtained with E. coli K‐12 MG1655 ΔratAB are shown in Appendix 2 (Figure A5a‐c). (c) Antibiotic tolerance assays were performed like those shown in Figure 2, and the fraction of ciprofloxacin‐tolerant cells 5 hr after inoculation was determined for cultures of E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI harboring complementation plasmids encoding cc1736 or coq10 or the empty vector (ev). Time–kill curves at this time point showed biphasic killing, revealing that the differences in antibiotic tolerance reflect different levels of persister cells (Figure A2a in Appendix 2). (d) The sensitivity of E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI to treatment with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) 2 hr after inoculation was determined for strains carrying cc1736 or coq10 complementation plasmids or the empty vector (ev) as shown in Figure 7c. Unless indicated otherwise, all data points in (a‐d) represent the mean of results from at least three independent experiments and error bars indicate standard deviations. In all experiments, the Plac promoter on all plasmids was induced during overnight cultures and throughout the experiment by supplementing culture media with 1 mM IPTG.

Bacteria were grown anaerobically on LB agar plates incubated in a plastic jar (cat# 1.16387.0001; Merck) with an anaerobic atmosphere generation bag (cat# 68061; Sigma). The formation of an anaerobic atmosphere was confirmed using Anaerotest strips (cat# 1.15112.0001; Merck). 1% w/v d‐glucose was added as a fermentable carbon source to LB agar plates incubated anaerobically.

2.2. Preparation of culture media

Lysogeny broth (LB) was prepared by dissolving 1% w/v of tryptone (cat# LP0042; Oxoid), 0.5% w/v of yeast extract (cat# LP0021; Oxoid), and 1% w/v of sodium chloride (cat# 27810.364; VWR Chemicals) in Milli‐Q H2O and sterilized by autoclaving. LB agar plates were prepared by supplementing LB medium with agar and 1.5% w/v before autoclaving. M9 medium was prepared according to the Cold Spring Harbor Protocols (M9 minimal medium (standard), 2010) with modifications in the form of 1× M9 salts (stock solution prepared from 5× M9 salts, see below) supplemented with 0.4% w/v Amicase (cat# 1002372245; Sigma; from 10% w/v sterile‐filtered stock), 0.4% w/v d‐glucose (cat# 101176K; VWR Chemicals; from 40% w/v autoclaved stock), 2 mM MgSO4 (cat#. 25.165.292; VWR Chemicals), 1 µg/ml thiamine (cat# T1270; Sigma), and 100 µM CaCl2 (cat# C3306; Sigma). The 5× M9 salt solution was prepared by dissolving 25.6 g Na2HPO4 (cat# S9390; Merck), 6 g KH2PO4 (cat# P0662; Sigma), 1 g NaCl (cat# 277810.364; VWR Chemicals), and 2 g NH4Cl (cat# 5470.1; Roth) in 400 ml Milli‐Q H2O supplemented with 20 µl of a 10 mg/ml FeSO4 solution (cat# F8048; Sigma). After confirming a pH of 7.4, the solution was sterile‐filtered and stored in the dark.

2.3. Strain construction

E. coli K‐12 MG1655 ΔratAB and E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI mutants (with identifiers CF083 and CF069/CF378, respectively) were constructed as scarless deletions using two‐step recombineering with a double‐selectable cassette encoding chloramphenicol resistance and sacB (sucrose sensitivity) that was amplified from template plasmid pKO4 (Lee et al., 2001). Recombineering functions were expressed from pWRG99 (Blank, Hensel, & Gerlach, 2011). The first step of recombineering replaced the target gene with the double‐selectable cassette, and the second step removed the double‐selectable cassette via recombineering with a pair of annealed 80‐mer oligonucleotides composed of twice 40 bp homologies flanking the desired deletion (Blank et al., 2011). The negative selection was performed on LB agar plates supplemented with 6% w/v sucrose (cat# S0389; Sigma; from a 60% w/v sterile‐filtered stock solution). E. coli K‐12 MG1655 and E. coli CFT073 derivatives were routinely transformed with plasmids using TSS transformation (Chung, Niemela, & Miller, 1989) and electroporation, respectively. Deletions of pasTI in E. coli strains O157:H7 EDL933 and 55989 as well as in Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica Typhimurium strain SR‐11 were constructed using recombineering functions expressed from pKM208 of Murphy and Campellone (2003). For E. coli EDL933 and S. enterica SR‐11, scarless deletions via the double‐selectable cassette of pWRG100 were achieved (see above). For E. coli 55989, the pasTI locus was first replaced with an FRT‐flanked gene cassette encoding kanamycin resistance. In the second step, gene cassettes were removed using Flp recombinase expressed from pCP20 in a way that only a short FRT scar remained. All bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table A1 (Appendix 1), all plasmids are listed in Table A2 (Appendix 1), and all oligonucleotides are listed in Table A3 (Appendix 1).

2.4. Plasmid construction

Plasmids were constructed using standard techniques of restriction‐based molecular cloning. Briefly, a PCR‐amplified fragment and the vector backbone were each cut with appropriate FastDigest restriction enzymes (Thermo Scientific). After fragment purification and backbone dephosphorylation (using FastAP dephosphorylase; Thermo Scientific), the two components were ligated together using the T4 ligase (Thermo Scientific). Site‐directed mutagenesis of plasmids was performed by PCR with partially overlapping primers as described by Liu and Naismith (2008). Plasmid construction was always confirmed by DNA sequencing. A list of all plasmids used in this study as well as details of their construction are given in Table A2 (Appendix 1). The sequences of all oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table A3 (Appendix 1).

The open reading frames of Caulobacter crescentus cc1736 and human coq10A (one of the two human coq10 isoforms) were obtained from GenScript after codon optimization for heterologous expression in E. coli. For coq10, we cloned the C‐terminal portion homologous to pasT/cc1736 without the N‐terminal mitochondrial signal peptide sequence at its 5′ end (see Figure A4a in Appendix 2).

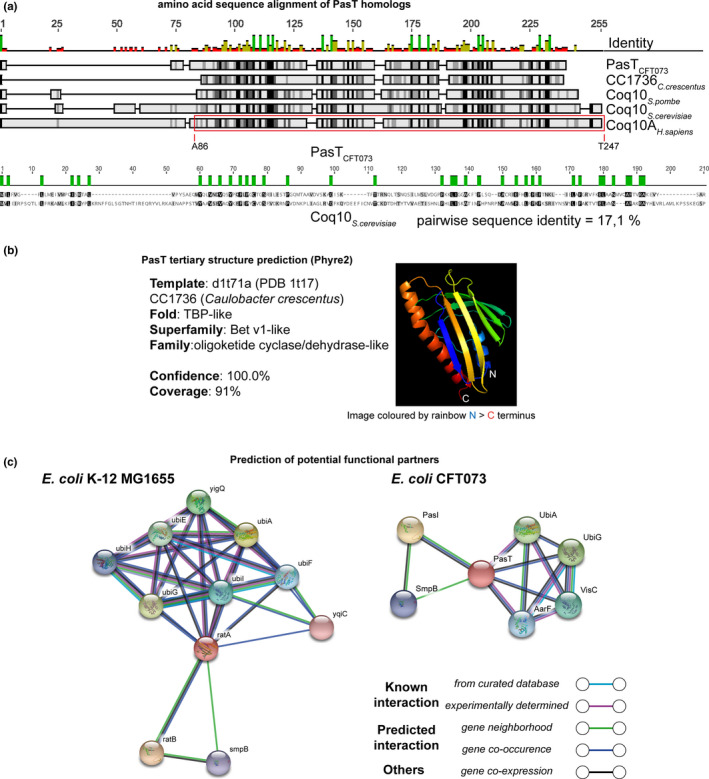

2.5. Sequence analyses and in silico predictions

For the protein alignment shown in Figure A4a of Appendix 2, amino acid sequences of E. coli CFT073 PasT (UniProt accession Q8FEY4), C. crescentus CC1736 (UniProt accession Q9A7I7), Coq10 of Schizosaccharomyces pombe (UniProt accession Q9USM9), and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (UniProt accession Q08058), as well as human Coq10A (UniProt accession Q96MF6), were aligned using MAFFT (implemented in Geneious v10.1.3) and manually curated. For the synteny analysis of pasTI loci shown in Figure 3, the presence of prophages at a known integration hotspot next to ssrA (see Mao et al. (2009)) was detected with PHASTER (Arndt et al., 2016) while the integration of other specific gene content was analyzed by manual sequence comparisons.

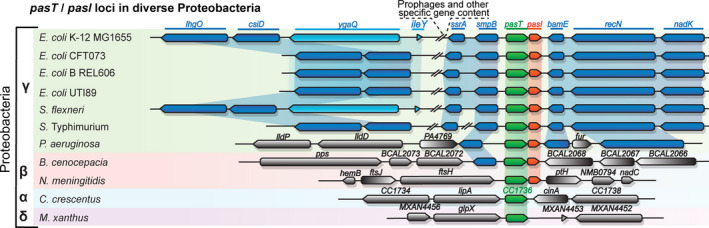

FIGURE 3.

pasT and, to a lesser extent, pasI are widely conserved among Proteobacteria. The genomic organization of pasT (green)/pasI (orange) loci is shown for representative Proteobacteria. Genes conserved in two or more organisms are shown in blue. A list of full strain names and genome accessions used for this synteny analysis is found in Table A4 (Appendix 1).

Phyre2 (https://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/phyre2; Kelley, Mezulis, Yates, Wass, & Sternberg, 2015) was used for the prediction of the tertiary structure of PasT (Figure A4b in Appendix 2). The prediction of potential functional partners in Figure A4c in Appendix 2 was obtained using STRING (https://string‐db.org/; Szklarczyk et al., 2018).

2.6. Spot assays

For the detection of bacterial growth inhibition upon expression of different proteins, 1.5 ml of dense overnight cultures of E. coli harboring indicated plasmids was adjusted to have the same optical density at 600 nm (OD600), washed once, and then serially diluted in sterile phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS). Subsequently, 10 µl of the serial dilutions was spotted on LB agar plates containing indicated supplements that induce or repress protein expression. Different copy numbers of otherwise isogenic plasmid vectors were achieved by merely changing the origin of replication on the otherwise identical plasmid backbone. Based on pNDM220 (mini‐R1 origin, low‐copy; Gotfredsen & Gerdes, 1998), we thus created pAH186_SC101 and pAH186_ColE1 with SC101 (medium‐copy) and ColE1 (high‐copy) origins, respectively (Jahn, Vorpahl, Hubschmann, Harms, & Muller, 2016). We assume that pasT/ratA cloned in pNDM220 is expressed at physiologically relevant levels due to a low plasmid copy number that should drive expression similar to the native chromosomal loci. A recent proteomic study revealed that RatA(YfjG) and RatB(YfjF) are expressed, under conditions identical to our experimental conditions (M9 medium with glucose as sole carbon source), to levels of ca. 30 and 50 molecules per cell, respectively (Supplementary Table 9 in Schmidt et al. (2015)).

The Doc and HipA TA system toxins are kinases that inhibit bacterial growth through phosphorylation and concomitant inactivation of elongation factor Tu (EF‐Tu) or glutamyl tRNA synthetase, respectively (Castro‐Roa et al., 2013; Germain, Castro‐Roa, Zenkin, & Gerdes, 2013). To compare the colony size between strains, 1.5 ml of dense overnight cultures was washed in 100 µl of phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS), serially diluted in PBS, and spotted (10 µl) on LB agar plates. When indicated, LB agar plates were supplemented with inducers and/or incubated under anaerobic conditions.

2.7. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

The MIC of antibiotics for different E. coli strains was determined by broth dilution assays. In short, serial 1.5‐fold dilutions of antibiotics in M9 medium with suitable supplements were inoculated with the different bacterial strains as indicated, sealed with a breathable film, and agitated at 37°C/160 rpm overnight. The MIC was determined as the lowest concentration of antibiotic that prevented bacterial growth as detected by visual inspection.

2.8. Antibiotic tolerance assays

The dynamics of antibiotic tolerance throughout the growth phases of E. coli were studied by performing antibiotic killing assays with bacterial cultures that had grown for different times after inoculation from overnight culture into the fresh medium as described previously (Harms et al., 2017). In more detail, overnight cultures were inoculated from single colonies into 3 ml of M9 medium and grown for ca. 16 hr in plastic culture tubes (cat# 62.515.006; Sarstedt). Subcultures of 10 ml M9 medium in Erlenmeyer flasks were inoculated 1:100 from these overnight cultures and agitated in a water bath at 37°C/160 rpm. All viable colony‐forming units (cfu) and antibiotic‐tolerant cfu (see below) were determined for isogenic cultures that had grown for different times after subculturing (from 0 hr to 8 hr) and represented the spectrum of bacterial growth phases from lag phase over exponential growth into stationary phase (see, e.g., the curve of colony‐forming units (cfu) plotted over time in Figure 2a). Antibiotic tolerance was assayed by treating 3 ml aliquots of culture in plastic tubes with lethal concentrations of ciprofloxacin (10 µg/ml), ampicillin (100 µg/ml), or colistin (6.6 µg/ml) for 5 hr at 37°C/160 rpm. In parallel, cfu counts of the same untreated cultures were determined by plating serial dilutions on LB agar plates. The MIC of ciprofloxacin for E. coli K‐12 MG1655 and CFT073 including all tested mutant derivatives was 0.00780 µg/ml, that is, the bacteria were treated with >1,000× MIC to avoid secondary effects of prophage activation (Harms et al., 2017). The MIC of colistin for E. coli K‐12 MG1655 and CFT073 including all tested mutant derivatives was 1.3 µg/ml, that is, the treatment was done with ca. 4× MIC. The MIC of ampicillin was found to be 8.88 µg/ml for the K‐12 strains and 33 µg/m for the CFT073 strains, meaning that treatment with 100 µg/ml ampicillin (following reference Norton & Mulvey, 2012) represented 11× MIC and 3× MIC, respectively.

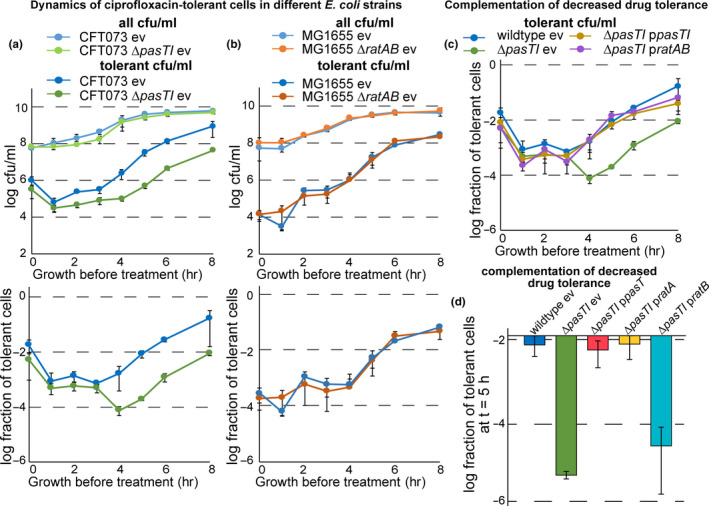

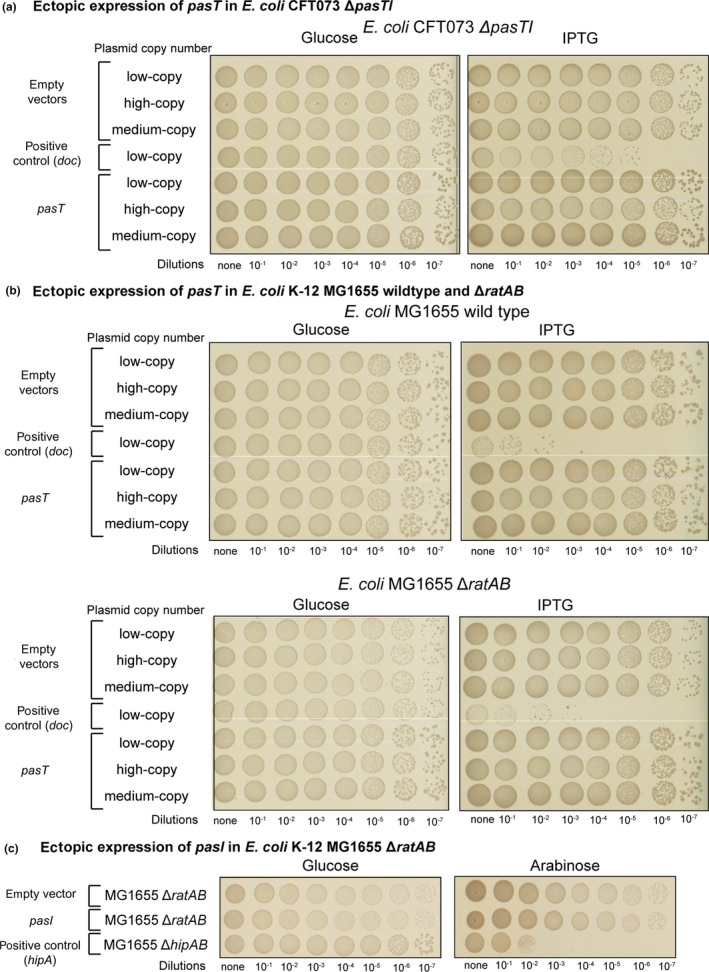

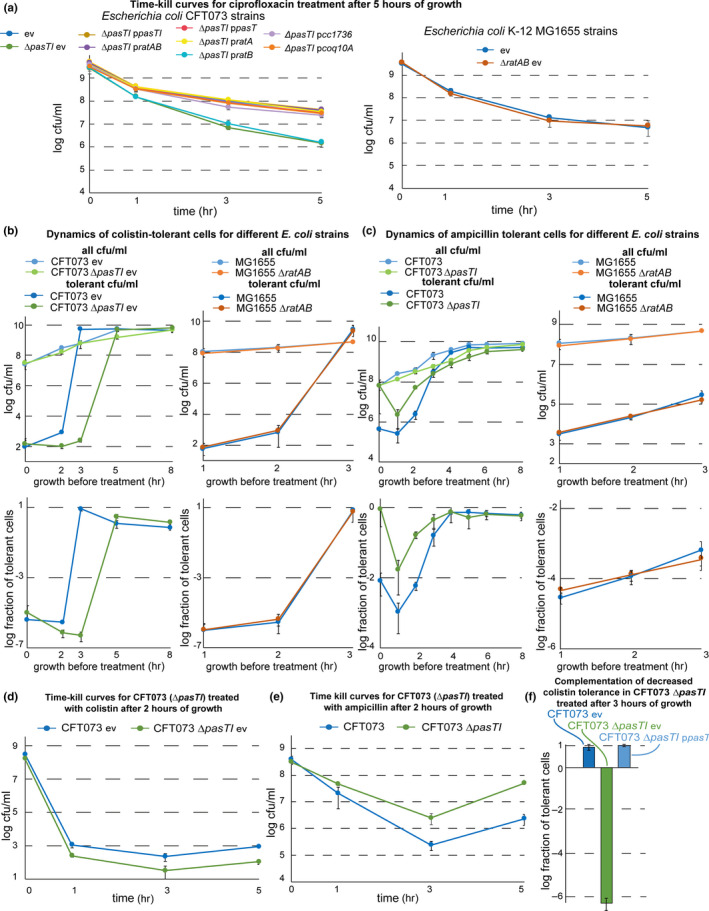

FIGURE 2.

PasT is important for the formation or survival of ciprofloxacin‐tolerant persisters. (a) Bacterial growth (colony‐forming units (cfu)/ml; top graph) and dynamics of ciprofloxacin‐tolerant cells (tolerant cfu/ml; top graph), as well as the fraction of tolerant cells at each data point (bottom graph), were determined for cultures of E. coli CFT073 and CFT073 ΔpasTI over time from inoculation over exponential growth into stationary phase. In short, bacteria were cultured for 1 hr, 2 hr, 3 hr, etc., and at each time point, we determined (1) total bacterial cfu/ml by direct plating and (2) drug‐tolerant cfu/ml by plating after 5 hr of treatment with 10 µg/ml ciprofloxacin (see Materials and Methods for details). (b) The same experiment as described in (a) was performed for cultures of E. coli K‐12 MG1655 and its ΔratAB derivative. A similar drop of tolerance in E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI (and the lack thereof in E. coli K‐12 MG1655 ΔratAB) was also observed for treatment with the membrane‐targeting antibiotic colistin but not with the β‐lactam ampicillin (Figure A2b/c in Appendix 2). Similar results as obtained with E. coli CFT073 and its ΔpasTI mutant in (a) were also obtained with different pathogenic E. coli strains and Salmonella Typhimurium (Figure A3a in Appendix 2). (c) Fractions of tolerant cells for cultures of E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI harboring complementation plasmids encoding pasTI or ratAB as well as wild‐type and ΔpasTI carrying the empty vector (ev) were determined as shown in (a). (d) The fraction of tolerant cells at 5 hr after inoculation was determined for cultures of E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI harboring complementation plasmids encoding pasT, ratA, or ratB. Time–kill curves of all strains included in (a‐d) sampled at this time point showed biphasic killing, demonstrating that the differences in surviving cfu/ml reflect different levels of persister cells (Figure A2a in Appendix 2). All data points in (a‐d) represent the mean of results from at least three independent experiments, and error bars indicate standard deviations

After antibiotic treatment, 1.5 ml of the samples was washed in 1 ml of PBS, concentrated in 100 µl of PBS, serially diluted in PBS, and spotted (10 µl) on LB agar plates. Agar plates were incubated at 37°C for at least 24 hr, and cfu counts per milliliter were determined from spots containing 10 to 100 bacterial colonies. The fraction of antibiotic‐tolerant cells was calculated as the ratio of the cfu counts per milliliter after and before antibiotic treatment. To verify that antibiotic‐tolerant cfu represented persister cells, we performed time–kill curves and confirmed biphasic kinetics of antibiotic killing (see, e.g., Figure A2a in Appendix 2).

2.9. Hydrogen peroxide sensitivity assay

The dynamics of hydrogen peroxide sensitivity throughout bacterial growth phases were assayed similarly to the antibiotic tolerance assay with the exception that bacteria were challenged with 10 mM of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (from 10 M stock; #cat 31642; Sigma) for 30 min instead of antibiotic treatment. Furthermore, experiments were only performed with bacteria grown up to no later than late‐exponential phase (4 hr after inoculation 1:100 from overnight culture) because we consistently observed complete tolerance to H2O2 in the stationary phase for all bacterial strains. When indicated, the cultures were treated with 20 mM of the antioxidant ascorbate (vitamin C; from 1 M stock; cat# A5960) for 20 min before the challenge with H2O2.

2.10. Assessment of membrane potential using DiOC2(3)

The bacterial membrane potential was assessed using indicator dye 3,3′‐diethyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC2(3)) as implemented in the BacLight Bacterial Membrane Potential Kit (Invitrogen, Thermo Fischer Scientific) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The DiOC2(3) dye shows green fluorescence in bacteria at low concentrations but becomes more concentrated in cells with larger membrane potential, causing it to aggregate and shift the fluorescence toward red emission.

Per strain and replicate, 2 μl cells from stationary‐phase cultures were inoculated into 2 ml of fresh LB medium in 14‐ml Falcon round‐bottom tubes (Corning) and grown to an OD600 of 0.2 at 37°C with shaking (180 rpm). 10 μl culture was transferred to 980 μl filtered phosphate‐buffered saline. To each cell solution, 10 μl of a 3 mM DiOC2(3) solution was added and cells were stained for 30 min at room temperature. The assay was verified by depolarizing the membrane with the protonophore carbonyl cyanide 3‐chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) at a final concentration of 5 μM. Data were recorded on a BD Biosciences Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer (Becton, Dickinson, and Company), with emission filters suitable for detecting red and green fluorescence. Settings on the flow cytometer were as follows: 25'000 recorded events at an FSC threshold of 15.000 and medium flow rate. Gating of stained cell population and analysis of flow cytometry data were performed in CFlow® (BD Accuri). As an indicator of membrane potential, the ratio of red to green fluorescence intensity was calculated.

2.11. Quantification of ubiquinone biosynthesis and levels

Levels of isoprenoid quinones were determined in cell extracts using HPLC‐ECD‐MS (electrochemical detection–mass spectrometry) as previously described (Hajj Chehade et al., 2019; Loiseau et al., 2017). The de novo synthesis of ubiquinone (UQ8) and its early biosynthetic intermediate octaprenyl‐phenol (OPP) was studied by supplementing bacterial cultures with their 13C‐labeled precursor 4‐hydroxybenzoic acid (4‐HB) and analyzing the accumulation of 13C label in the molecules of interest. An illustration of the UQ8 biosynthetic pathway in E. coli was included in Figure 5a for clarity.

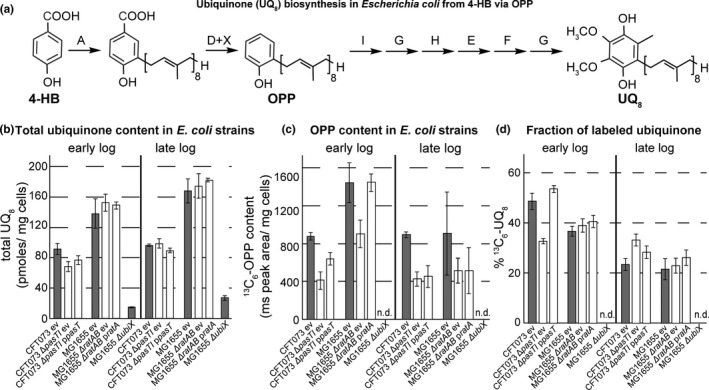

FIGURE 5.

Direct measurements of ubiquinone levels and biosynthesis. (a) Schematic summary of the ubiquinone (UQ8) biosynthetic pathway in E. coli. The precursor of 4‐hydroxybenzoic acid (4‐HB) is prenylated by UbiA and decarboxylated by UbiD to form the early intermediate octaprenyl‐phenol (OPP). Subsequent modifications of the aromatic ring by Ubi enzymes (UbiI, UbiG, UbiH, UbiE, and UbiF) yield ubiquinone 8 (UQ8). When 13C7‐4‐HB is added to cultures to evaluate de novo synthesis of UQ, 13C6‐OPP and 13C6‐UQ8 are formed (13C carbon atoms represented in green). (b) Total ubiquinone (UQ8) content (sum of 13C6‐UQ8 and unlabeled ubiquinone UQ8) was assessed after HPLC‐ECD‐MS analysis (see Materials and Methods) for early and late log‐phase cultures of E. coli CFT073, K‐12 MG1655, their ΔpasTI/ΔratAB mutant derivatives, and the complemented strains. (c) The content of 13C6‐OPP (octaprenyl‐phenol, an early intermediate of the UQ8 pathway, see (a)) is reported for the same strains. (d) The plot shows the fraction of 13C6‐UQ8 over total UQ8 and is thus informative about the de novo biosynthesis of UQ8 for the same strains as in (b) and (c). All data points represent the mean of results from four independent experiments, and error bars indicate standard deviations. An E. coli K‐12 MG1655 ubiX mutant was used as a negative control in these experiments since UbiX is required for ubiquinone biosynthesis by producing a crucial cofactor for UbiD (Aussel et al., 2014; White et al., 2015; see also in (a)). ev = empty vector pNDM220, n.d. = not detected

Bacterial subcultures in 10 ml of M9 medium in Erlenmeyer flasks were inoculated 1:100 from dense overnight cultures and agitated in a shaking water bath at 37°C/160 rpm to early log phase (2 hr of growth for wild‐type and ΔpasTI/ΔratAB strains; ca. 108 cfu/ml) or late log phase (4 hr of growth for wild‐type and ΔpasTI/ΔratAB strains; ca. 109 cfu/ml) and then supplemented with 10 µM 13C7‐4‐HB (cat# 587869; Sigma) for an additional period of 30 min. Subsequently, cells were cooled on ice, harvested by centrifugation, and washed with 1 ml of cold PBS. The weight of each cell pellet was determined, a proportional amount of the UQ10 standard was added, and isoprenoid quinones were extracted and analyzed by HPLC‐ECD‐MS. Single‐ion monitoring detected the following molecules: 13C6‐OPP (M+NH4 +), m/z 662.0–663.0, 5–10 min, scan time 0.2 s; UQ8 (M+H+), m/z 727.0–728.0, 6–10 min, scan time 0.2 s; 13C6‐UQ8 (M+H+), m/z 733.0–734.0, 6–10 min, scan time 0.3 s; and UQ10 (M+NH4 +), m/z 880.2–881.2, 10–17 min, scan time 0.2 s. Peak areas were corrected for sample loss during extraction based on the recovery of the UQ10 internal standard (typically higher than 80%) and were then normalized to the cell's wet weight. The ECD signal of UQ8 was converted into picomoles based on a calibration curve obtained with commercial UQ10.

2.12. Quantification and statistical analysis

Data sets were analyzed by calculating the mean and standard deviation of at least three biological replicates for each experiment. Detailed information for each experiment is provided in the figure legends.

3. RESULTS

3.1. pasTI does not encode a toxin–antitoxin system

One previous study proposed that the pasTI locus encodes a new TA system composed of the PasT toxin and the PasI antitoxin (Norton & Mulvey, 2012). However, we did not detect any growth inhibition of E. coli CFT073 when pasT was either expressed at physiologically relevant levels from a low‐copy‐number plasmid or overexpressed from isogenic plasmids replicating at higher copy numbers (Figure 1). Deletion mutants lacking the chromosomally encoded pasTI locus, a possible source of experimental interference, also failed to show any inhibition of growth upon pasT overexpression (Figure A1a, Appendix 2). Similarly, the expression of pasT failed to inhibit the growth of E. coli K‐12 MG1655 (Figure A1b, Appendix 2). No growth inhibition was also observed upon expression of the proposed antitoxin pasI (Figure A1c, Appendix 2). We therefore concluded that the pasTI locus is unlikely to encode a TA system.

3.2. Lack of pasT impairs antibiotic tolerance of E. coli CFT073

To gain deeper insight into the role of pasTI in E. coli persister formation, we monitored the level of antibiotic‐tolerant cells throughout the different bacterial growth phases as previously described (Harms et al., 2017). Interestingly, we observed decreased survival of the E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI mutant when treated with ciprofloxacin compared to the wild‐type during exponential growth and over into the stationary phase. This defect in survival was caused by a lower level of persister cells in the ΔpasTI mutant population (Figure 2a; see also Figure A2a in Appendix 2), and similar results were obtained for treatment with the membrane‐targeting antibiotic colistin (Figure A2b,d,f in Appendix 2). For the β‐lactam ampicillin, we observed increased levels of tolerant cells for the ΔpasTI mutant, possibly caused by its partial growth defect since this class of antibiotics only kills actively growing cells (Figure A2c,e in Appendix 2). Conversely, no phenotype was observed at any time of the growth curve when comparing antibiotic tolerance of E. coli K‐12 MG1655 and its ΔratAB derivative (Figure 2b; see also Figure A2a in Appendix 2).

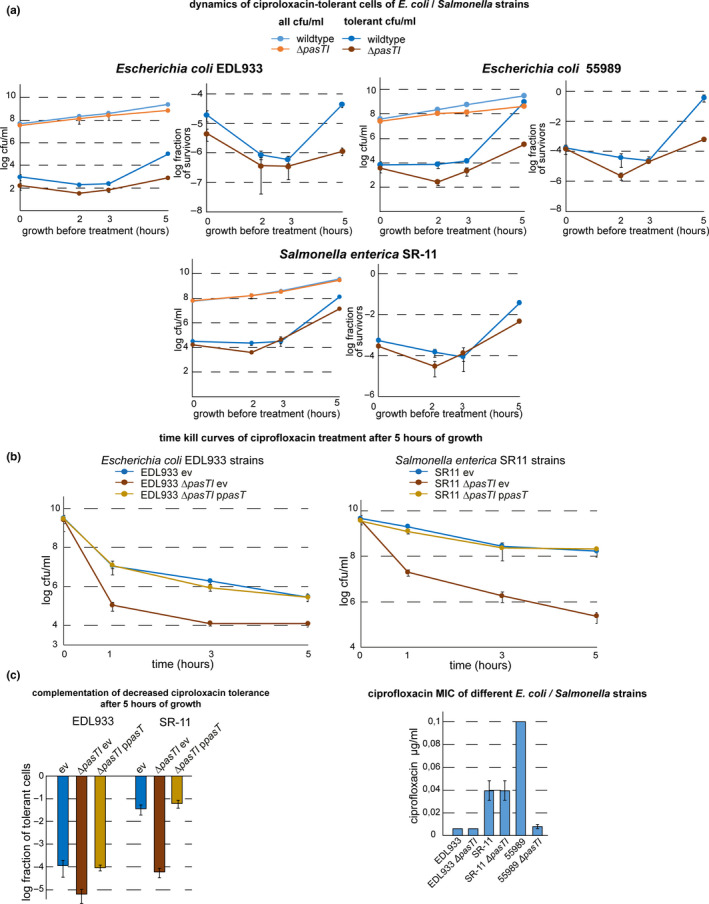

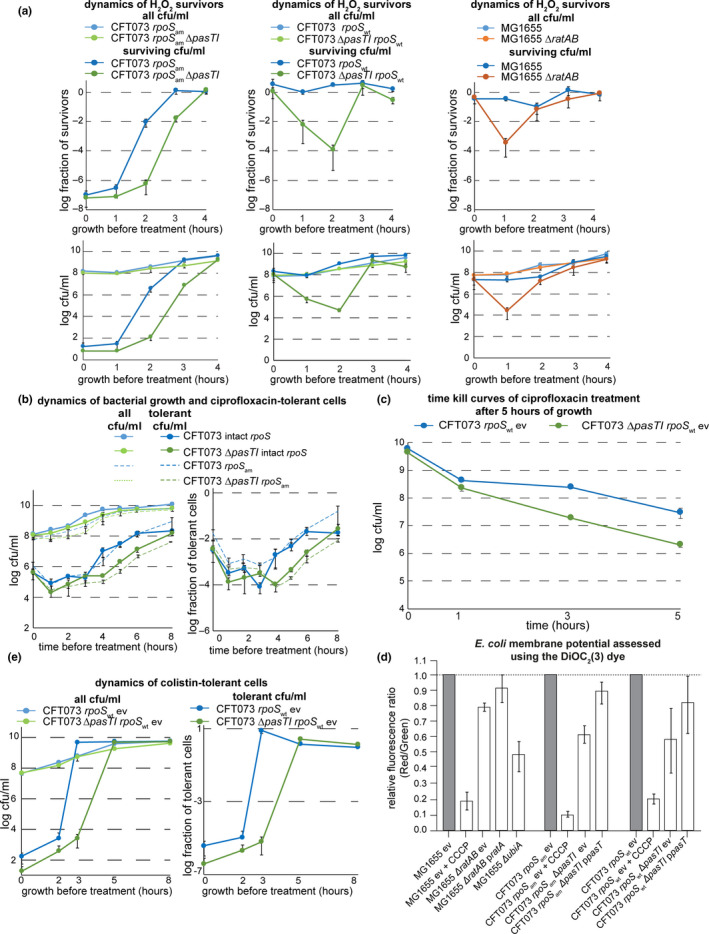

These results were overall consistent with the previous observation that pasTI is somehow critical for the formation or survival of antibiotic‐tolerant persister cells in E. coli CFT073 but that ratAB in E. coli K‐12 MG1655 is not (Norton & Mulvey, 2012). Both the pasTI and ratAB loci, provided in trans from a low‐copy plasmid, as well as pasT or ratA alone, could complement the phenotype of decreased ciprofloxacin persister levels of E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI (Figure 2c,d; see also Figure A2a in Appendix 2). These results demonstrate that the defect of E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI in persister formation or survival is linked to the lack of PasT. Furthermore, they reveal that the differential effect of a pasTI/ratAB knockout in the two E. coli strains is not due to differences between PasT and its ortholog RatA. This finding is not unexpected given the near identity of PasT and RatA protein sequences with two amino acid differences only (S90 and D111 in PasT of E. coli CFT073, and N90 and E111 in E. coli K‐12 MG1655). To clarify whether E. coli CFT073 or K‐12 is representative of enterobacteria in general, we tested the ciprofloxacin tolerance phenotype of pasTI mutants constructed in two additional pathogenic E. coli strains and the more distantly related Salmonella Typhimurium (Figure A3, Appendix 2). Clearly, pasTI knockouts of E. coli O157:H7 strain EDL933 and S. enterica Typhimurium SR‐11 showed decreased levels of ciprofloxacin‐tolerant persisters that could be complemented by expression of E. coli CFT073 pasT. The other tested pathogenic E. coli strain 55989 also showed lower ciprofloxacin tolerance after pasTI was knocked out, but we cannot exclude that this phenotype might be partially caused by decreased intrinsic ciprofloxacin resistance of the pasTI mutant in this strain (Figure A3, Appendix 2). Taken together, these results suggest that the phenotypes of E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI and not of E. coli K‐12 ΔratAB are more broadly representative.

3.3. E. coli PasT/RatA is the homolog of mitochondrial Coq10

The pasT/ratA gene is well conserved among Proteobacteria and not always associated with pasI/ratB orthologs (Figure 3), suggesting that PasT/RatA might have a conserved housekeeping function that can be exerted independently of its previously proposed antitoxin partner.

Interestingly, PasT shares a protein domain (Pfam: Polyketide_cyc2, PF10604; InterPro: StART domain, IPR005031) and modest sequence similarity to the mitochondrial protein Coq10 (Figure A4a/b, Appendix 2; Shen et al., 2005; Tsui et al., 2019). Coq10 has been studied as an accessory factor of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC), a series of protein complexes that create an electrochemical gradient across a membrane (the “proton‐motive force”) which fuels cellular ATP synthesis (Figure 4a; Anraku, 1988). In E. coli, electron transport along the ETC involves the electron shuttle ubiquinone under aerobic conditions (Sharma, Teixeira de Mattos, Hellingwerf, & Bekker, 2012) while two related but distinct molecules, menaquinone and demethylmenaquinone, predominate under anaerobic conditions (Nitzschke & Bettenbrock, 2018 and literature cited therein). Studies on yeast Coq10 indicated that this protein might serve as a “lipid chaperone” carrying newly synthesized ubiquinone to the respiratory complexes and/or localizing it properly within the ETC using a steroidogenic acute regulatory protein‐related lipid transfer (StART) domain (Figure 4a; Awad et al., 2018; Tran & Clarke, 2007). Based on the similarity of the two proteins, we hypothesized that PasT/RatA might be the bacterial homolog of mitochondrial Coq10 and have a related or even equivalent role in cellular respiration.

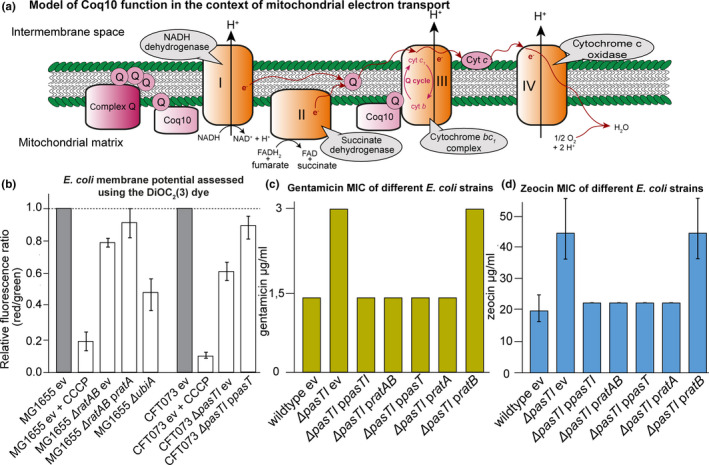

FIGURE 4.

E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI and E. coli MG1655 ΔratAB mutants have a defective electron transport chain (ETC). (a) The figure illustrates how electrons (e−) flow in the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) from complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) or complex II (succinate dehydrogenase) to complex III (cytochrome bc 1 complex) via membrane‐bound ubiquinone (commonly abbreviated as Q). Then, electrons transit via cytochrome C molecules and reach complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) where they reduce dioxygen into water. Electron transfer is coupled to the active export of protons through the ETC complexes. The overall setup of this ETC is related in mitochondria and E. coli, but E. coli can also respire anaerobically by using alternative terminal electron acceptors and the dedicated anaerobic electron carriers menaquinone and demethylmenaquinone instead of ubiquinone. Studies on the mitochondrial ETC in yeast suggested that Coq10 is a “lipid chaperone” involved in the delivery of ubiquinone (synthesized by the multi‐subunit protein complex Q) to its sites of function and/or proper localization at the sites of function (recently reviewed by Awad et al., 2018; Stefely & Pagliarini, 2017; Tran & Clarke, 2007). (b) The membrane potential of different E. coli samples was assessed using the DiOC2(3) dye in a way that a decrease in red/green ratio is indicative of depolarization (see Materials and Methods). Results were compared to values obtained with the uncoupler CCCP (complete depolarization) and the E. coli K‐12 ubiA mutant (unable to synthesize ubiquinone; Pelosi et al., 2019). Both ratAB and—more pronounced—pasTI knockouts showed a decrease in the signal that was less strong than the effect of a ubiA knockout and could be complemented by ratA/pasT. (c, d) Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI for gentamicin (c) and zeocin (d) were determined by broth dilution assays. The bacteria carried either an empty vector (ev) or complementation plasmids encoding pasTI, ratAB, pasT, ratA, or ratB. For gentamicin, the result of one representative experiment is shown (additional independent replicates in Figure A5a in Appendix 2). Similar results were obtained for E. coli K‐12 MG1655 ΔratAB. (Figure A5b/c in Appendix 2). Unless specified otherwise, data points represent the mean of results from three independent experiments, and error bars indicate standard deviations.

3.4. E. coli ΔpasTI/ΔratAB mutants display defective respiration and modest phenotypes in ubiquinone biosynthesis

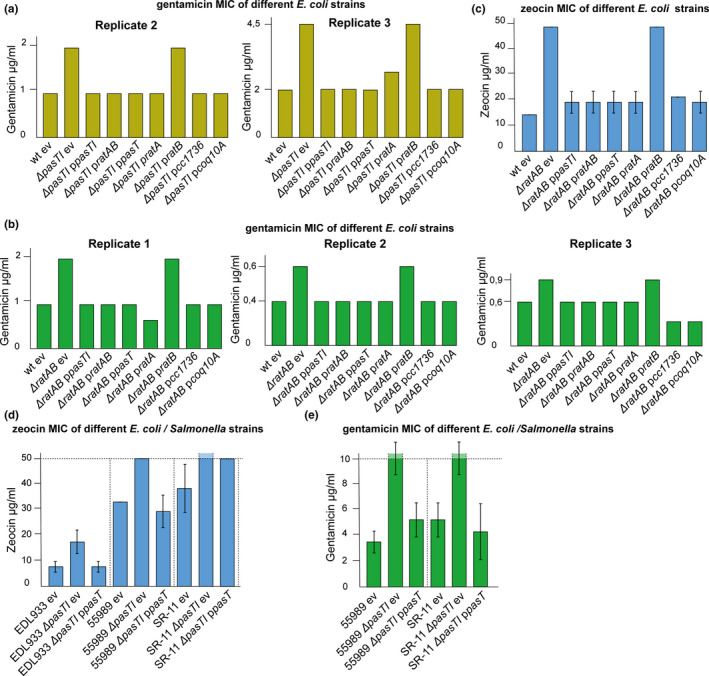

Yeast mutants lacking coq10 are known to display defective electron transport (Allan et al., 2013; Cui & Kawamukai, 2009), and we therefore studied whether ETC functionality is also compromised in E. coli mutants lacking PasT/RatA. The efficiency of bacterial electron transport was assessed using fluorescent indicator dye DiOC2(3) to probe the cellular membrane potential. Compared to the parental wild‐type strains, both pasTI and ratAB mutants revealed a modest shift of signal toward the depolarized controls that could be complemented by providing pasT or ratA in trans (Figure 4b). As an independent approach to study the same phenomenon, we compared the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of gentamicin and zeocin for growth of the E. coli pasTI and ratAB mutants and their parental wild‐type strains (Figure 4c,d; see also Figure A5a‐c in Appendix 2). The uptake of gentamicin and zeocin, antibiotics of the aminoglycoside and the bleomycin families, is directly dependent on and proportional to the proton‐motive force, so that impaired functionality of the ETC results in an increased MIC of these antibiotics (Krause, Serio, Kane, & Connolly, 2016; Miller, Edberg, Mandel, Behar, & Steigbigel, 1980; Søballe & Poole, 2000). We indeed observed elevated MICs of both drugs for the pasTI and ratAB mutants that could be complemented with pasT or ratA but not ratB (Figure 4c,d; see also Figure A5a‐c in Appendix 2). Taken together, these results suggest a clear but modest decrease in membrane polarization as a consequence of defective electron transport for both E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI and E. coli K‐12 MG1655 ΔratAB mutants. Similar results were obtained with wild‐type and ΔpasTI variants of different pathogenic E. coli/S. enterica strains (Figure A5d/e in Appendix 2).

To study the role of ubiquinone in these phenotypes, we quantified the total levels of ubiquinone and biosynthetic intermediates as well as the de novo biosynthesis of ubiquinone in E. coli ΔpasTI/ΔratAB mutants (Figure 5a‐d). Previous work found that yeast coq10 mutants show decreased efficiency of ubiquinone biosynthesis specifically in exponential growth but have largely normal overall levels of ubiquinone in their mitochondria (Allan et al., 2013; Barros et al., 2005). Similarly, we saw no differences in total ubiquinone content when comparing E. coli ΔpasTI/ΔratAB mutants to their parental wild‐type strains (Figure 5b). However, we indeed found a decrease in ubiquinone precursor levels for both ΔpasTI and ΔratAB mutants during the exponential growth phase and a mild defect in the de novo biosynthesis of ubiquinone specifically for CFT073 ΔpasTI in early log phase that could be complemented by pasT/ratA (Figure 5c/d).

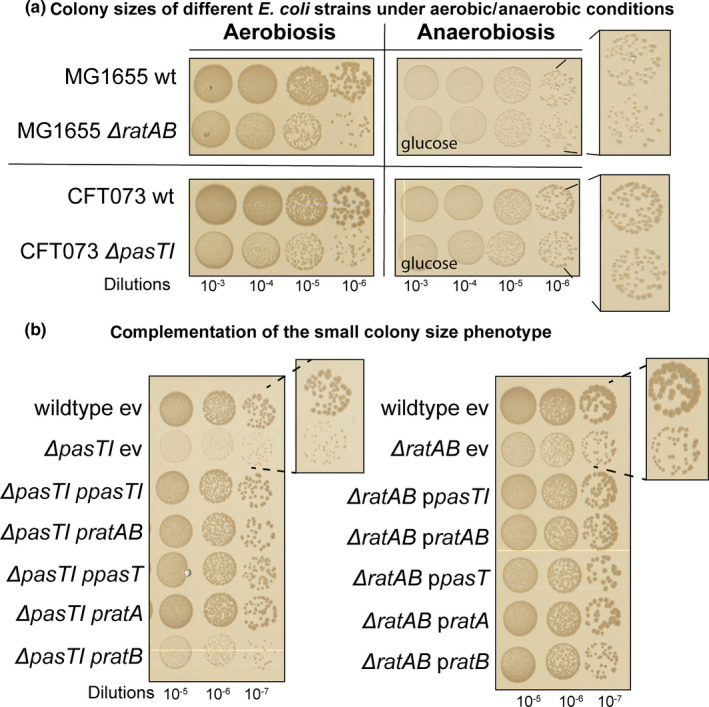

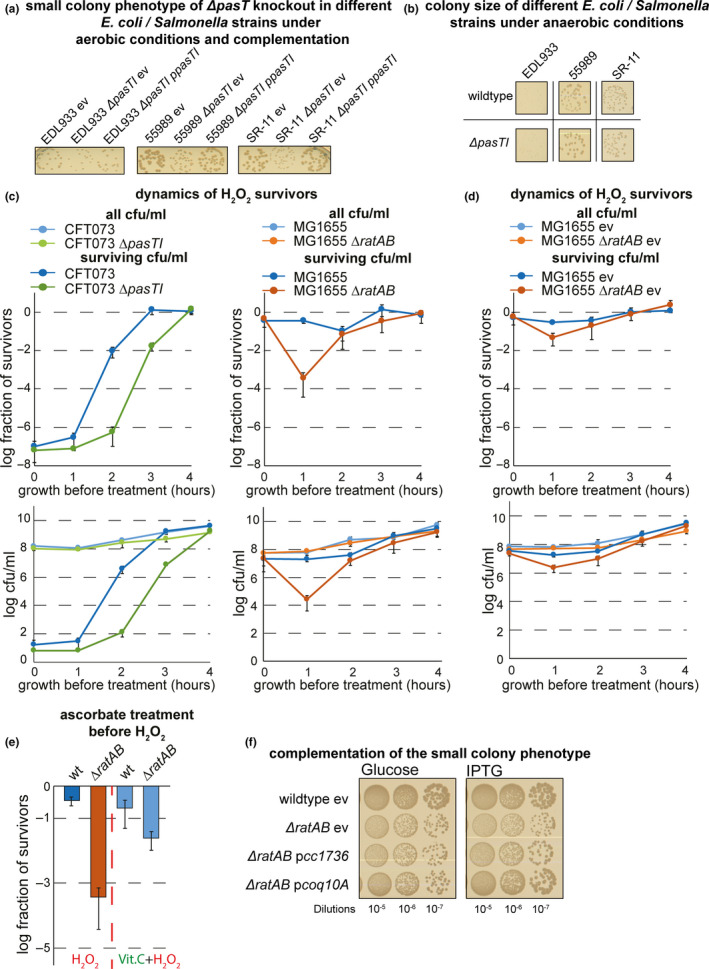

3.5. E. coli ΔpasTI/ΔratAB mutants display increased susceptibility to oxidative stress

Beyond defects in electron transport and log‐phase ubiquinone biosynthesis, yeast mutants lacking Coq10 are known to be hypersensitive to oxidative stress (Allan et al., 2013; Cui & Kawamukai, 2009). This phenomenon is consistent with our observation that E. coli and Salmonella pasTI and ratAB mutants grow like their parental wild‐types in the absence of oxygen but show a small‐colony phenotype under aerobic conditions (Figure 6a; see also Figure A6a‐b in Appendix 2). Similar phenotypes are typical for bacterial mutants with defects in respiration and/or ubiquinone biosynthesis and have also been described for the pasT knockout of E. coli CFT073 in previous work (Aussel et al., 2014; Day, 2013; Koskiniemi, Pranting, Gullberg, Näsvall, & Andersson, 2011; Norton & Mulvey, 2012; Poon et al., 2000; Proctor et al., 2014; Xia et al., 2017). Complementation with pasT or ratA, but not ratB, provided on a low‐copy plasmid enabled the growth of E. coli pasTI and ratAB mutants to normal colony size under aerobic conditions (Figure 6b,c; see Figure A6a in Appendix 2).

FIGURE 6.

Lack of pasT/ratA causes a small‐colony phenotype under aerobic conditions. (a) Cultures of E. coli CFT073 wild‐type, E. coli K‐12 MG1655 wild‐type, and their ΔpasTI/ΔratAB derivatives were diluted and spotted on LB agar plates incubated either in the presence (left) or absence (right) of oxygen. d‐glucose (1% w/v) was added as a fermentable carbon source to LB agar plates incubated anaerobically (see Materials and Methods). (b, c) Spot assay of E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI (b) or E. coli K‐12 MG1655 ΔratAB (c) carrying the empty vector (ev) or different complementation plasmids was spotted on LB agar plates to visualize differences in colony size. Similar results as shown in (a‐c) were also obtained with different pathogenic E. coli strains and Salmonella Typhimurium (Figure A6a/b in Appendix 2)

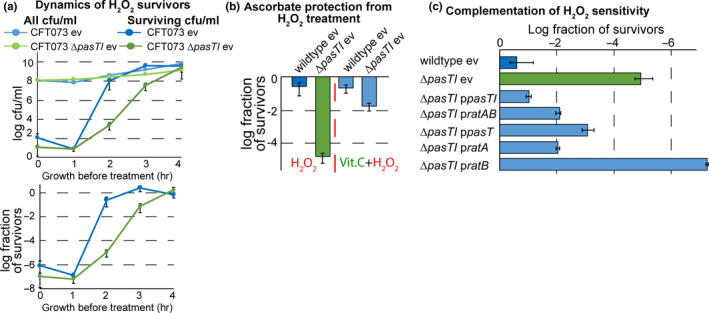

We further compared the sensitivity of E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI and its parental wild‐type to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as an exogenous source of oxidative damage (Figure 7a). Similar to previous observations with yeast coq10 mutants (Cui & Kawamukai, 2009), the pasT knockout was hypersensitive to oxidative damage which could be abolished by pretreating the cultures with the potent antioxidant ascorbic acid (vitamin C; Figure 7b and Figure A6c‐e in Appendix 2). The H2O2 sensitivity of E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI could also be complemented in trans by pasT/ratA, but not ratB, expressed from their promoter (Figure 7c). Taken together, these results presented in Figures 4, 5, 6, 7 establish that the lack of PasT or RatA in E. coli causes similar phenotypes as known for yeast coq10 mutants.

FIGURE 7.

pasT/ratA deficiency causes hypersensitivity to redox stress and oxidative damage in E. coli. (a) Dynamics of colony‐forming units (cfu/ml: top graph; a fraction of survivors: bottom graph) before and after treatment with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) for E. coli CFT073 wild‐type/ΔpasTI over time after inoculation from stationary phase into fresh medium (see Materials and Methods). (b) The fraction of cells surviving H2O2 treatment 2 hr after inoculation from the stationary phase was determined for cultures of E. coli CFT073 wild‐type/ΔpasTI with or without pretreatment with the antioxidant vitamin C (ascorbate). Similar results as shown in (a) and (b) for E. coli CFT073 wild‐type/ΔpasTI were also obtained for E. coli K‐12 MG1655 wild‐type/ΔratAB (Figure A6d/e in Appendix 2). (c) The fraction of cells surviving H2O2 treatment 2 hr after inoculation from stationary phase was determined for cultures of E. coli CFT073 wild‐type/ΔpasTI carrying either the empty vector (ev) or different complementation plasmids. We could not assay the complementation of H2O2 sensitivity for E. coli K‐12 MG1655 ΔratAB because, curiously, already the empty vector caused a strong decrease in H2O2 sensitivity of this strain (Figure A6d in Appendix 2). All data points in (a‐c) represent the mean of results from at least three independent experiments, and error bars indicate standard deviations

3.6. PasT deficiency in E. coli can be functionally complemented with human mitochondrial Coq10

Given the high conservation of respiratory electron transport including the electron shuttle ubiquinone, we wondered whether PasT/RatA knockout phenotypes could be heterologously complemented by other bacterial or even mitochondrial homologs. Previous work had already shown that the alphaproteobacterial PasT homolog CC1376 of C. crescentus and human Coq10 can complement the S. cerevisiae Δcoq10 phenotypes (Allan et al., 2013; Barros et al., 2005; Cui & Kawamukai, 2009). Remarkably, both CC1376 and human mitochondrial Coq10 could also complement all phenotypes of RatA/PasT knockout mutants in E. coli: small colony size under aerobic condition, increased MIC of gentamicin/zeocin, defect of E. coli CFT073 in antibiotic tolerance, and, at least to some extent, H2O2 sensitivity (Figure 8a‐d and Figure A6f in Appendix 2). These results show that RatA/PasT and CC1376 or Coq10 are not merely homologs (Figure A4a/b in Appendix 2) but seem to also share a function linked to respiratory electron transport that is conserved from bacteria to humans.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. No evidence for links between PasT and PasI or a common function as a TA system

Our study had initially been inspired by previous work proposing that PasT is a TA‐encoded toxin that inhibits ribosome assembly and somehow contributes to persister cell formation of uropathogenic E. coli (Norton & Mulvey, 2012; Zhang & Inouye, 2011). Given recent debates about the role of TA systems in antibiotic tolerance of E. coli, this was a very interesting result (Goormaghtigh et al., 2018; Harms et al., 2017; Shan et al., 2017). However, we found no evidence for a link of PasT to either TA systems or ribosomes. Consistently, the data of a previous study also showed that expression of the PasT/RatA ortholog of Salmonella Typhimurium did not affect bacterial growth (Lobato‐Marquez, Moreno‐Cordoba, Figueroa, Diaz‐Orejas, & Garcia‐del Portillo, 2015). The discrepancy between our results and earlier work reporting growth inhibition upon PasT expression may be explained by the very high overexpression of protein constructs in previous studies that is prone to interfere with cellular physiology. Consistently, severe overexpression of coq10 in yeast inhibited cellular growth by interfering with mitochondrial respiration (Zampol et al., 2010).

Our study also did not find evidence for a functional link between PasT and PasI, because phenotypes observed with ΔpasTI mutants could always be complemented by pasT and its homologs alone but never by its proposed antitoxin partner. Consistently, only pasT genes of beta‐ and gammaproteobacteria are accompanied by a pasI gene while solitary pasT (including mitochondrial coq10) is much more abundant (Figure 3; Shen et al., 2005; Tsui et al., 2019). Future studies could therefore explore whether PasI might be an accessory factor to PasT that constitutes an evolutionary innovation in beta‐ and gammaproteobacteria or whether pasI is just a functionally unrelated protein that these lineages acquired and encoded next to pasT merely by chance.

4.2. Unification of the PasT/Coq10 family of StART domain proteins

Though we cannot exclude that PasT has a moonlighting function linked to ribosome assembly, multiple observations suggest that PasT is the bacterial equivalent of its mitochondrial homolog Coq10 that acts as an accessory factor in the ubiquinone‐dependent ETC: E. coli mutants lacking PasT/RatA display phenotypes linked to defective ubiquinone‐dependent electron transport that are similar to phenotypes observed for coq10 mutants (Figures 4, 5, 6, 7), and these phenotypes can be largely complemented by human Coq10 (Figure 8). Consistently, a prediction of potential functional partners for PasT/RatA using STRING (https://string‐db.org/; Szklarczyk et al., 2018) retrieved many proteins involved in ubiquinone biosynthesis and the ETC but no ribosomal proteins (Figure A4c in Appendix 2). From these results, we therefore conclude that PasT/RatA are not only homologous to Coq10 but at least to large extent functionally equivalent as “lipid chaperones” that arrange the utilization of ubiquinone in the ETC (recently reviewed by Awad et al., 2018; Stefely & Pagliarini, 2017).

These findings close one of the multiple gaps in our understanding of the electron transport chain and the functionality of ubiquinone that are widely conserved and thus relevant both for human diseases and—given the broad conservation of pasT among pathogenic Proteobacteria (Figure 3)—for antibiotic treatment (Aussel et al., 2014; Hirose et al., 2019; Stefely & Pagliarini, 2017). Notably, eukaryotic ubiquinone biosynthesis and respiratory electron transport chain are mitochondrial pathways that have been acquired by the eukaryotic lineage from the primordial bacterial endosymbiont during its evolution from a proteobacterium into extant mitochondria (Andersson et al., 1998; Stefely & Pagliarini, 2017). We therefore anticipate that future studies on the PasT/Coq10 family might use the technically highly accessible E. coli system to unravel the molecular function of these proteins in ubiquinone‐dependent respiration that seems to be conserved from bacteria to humans.

4.3. Links between PasT, electron transport, and oxidative stress

E. coli ΔratAB/ΔpasTI mutants display several phenotypes linked to oxidative stress sensitivity or redox balance (Figure 4 and Figure 6/Figure 7) that correlates with modest defects in exponential‐phase ubiquinone biosynthesis as also previously observed for yeast coq10 mutants (see above). However, it is not clear how defective respiration causes these phenotypes or what is the molecular function of Coq10 (Allan et al., 2013; Awad et al., 2018; Barros et al., 2005; Cui & Kawamukai, 2009; Stefely & Pagliarini, 2017; Tsui et al., 2019). In this regard, our study moves the understanding of PasT/RatA roughly to the point of how far the field understands Coq10.

Notably, the mild defect of E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI in ubiquinone biosynthesis (Figure 5c/d) was too weak to affect steady‐state ubiquinone levels (Figure 5a). It therefore cannot explain the multiple phenotypes of E. coli ΔpasTI/ΔratAB mutants that are linked to defective aerobic respiration given that, for example, the considerable reduction of ubiquinone levels in an E. coli ubiI mutant (ca. 15% of wild‐type) still enables normal respiration (Pelosi et al., 2016). These strong pleiotropic phenotypes of PasT/RatA deficiency (and the lack of Coq10) are therefore likely caused by problems linked to the proposed role of these proteins as “lipid chaperones” that facilitate the implementation of ubiquinone at the electron transport chain (recently reviewed by Awad et al., 2018; Stefely & Pagliarini, 2017). Consequently, the observed phenotypes in ubiquinone biosynthesis might rather be downstream consequences—maybe via a feedback mechanism—of improperly utilized ubiquinone.

In general, impaired aerobic respiration often causes growth defects and a small‐colony phenotype specifically under aerobic conditions (Aussel et al., 2014; Day, 2013; Koskiniemi et al., 2011; Poon et al., 2000; Proctor et al., 2014; Xia et al., 2017). On the one hand, this observation could be explained by the poor energy metabolism of these mutants due to their limited ability to use oxygen as a terminal electron acceptor, while under anaerobic conditions other quinone electron shuttles serve other terminal acceptors or merely fermentation takes place instead. On the other hand, these observations could be explained as a consequence of reactive oxygen species (ROS) sensitivity and/or production. Consistently, E. coli K‐12 defective for ubiquinone production grows poorly under aerobic conditions where it shows signs of oxidative stress (Nitzschke & Bettenbrock, 2018), and similar observations have been made for a yeast coq10 mutant (Cui & Kawamukai, 2009). These results could be explained by the pro‐ and antioxidant activities of different forms of ubiquinone, but the details of this relationship have not been resolved (Wang & Hekimi, 2016). Also, defects in the electron transport chain cause leakage of electrons and uncontrolled formation of ROS that damages cellular macromolecules, a problem inherent to respiration, and linked to many human diseases (Jastroch, Divakaruni, Mookerjee, Treberg, & Brand, 2010). We anticipate that future studies unraveling the precise biological function of PasT/Coq10 in the context of ubiquinone‐dependent respiration will also reveal how the lack of its activity is linked to oxidative stress and cellular redox balance in bacteria and humans.

4.4. PasT highlights the importance of electron transport for bacterial persister cells

The initial focus of our study was to understand the specific defect of uropathogenic E. coli CFT073 lacking pasTI in the formation or survival of persister cells (Norton & Mulvey, 2012). We readily reproduced this phenotype in E. coli CFT073 itself and different pathogenic E. coli strains as well as Salmonella Typhimurium (Figure 2 as well as Figures A2 and A3 in Appendix 2). However, our results also showed that PasTI is not just a genetic switch controlling transition into dormancy as a TA module would supposedly be. Instead, PasT seems to be deeply wired into bacterial redox balance and energy metabolism through its role as a facilitator of ubiquinone‐dependent respiration (Figure 9). The link of PasT to antibiotic tolerance is therefore likely indirect and mediated through broad distortions of bacterial physiology caused by defective aerobic respiration.

FIGURE 9.

Working model: pasT deficiency causes pleiotropic phenotypes by interfering with ubiquinone‐dependent respiration. The illustration summarizes and interprets the main results of our study. In the absence of PasT, membrane potential, resilience to oxidative stress, and (for pathogenic E. coli as well as Salmonella Typhimurium) levels of antibiotic‐tolerant persisters are reduced (Figure 2/Figures 4, 5, 6, 7 and Figure A2/Figure A3/Figure A5/Figure A6 in Appendix 2). These phenotypes are—similar to findings for yeast coq10 mutants—likely caused by defective aerobic respiration due to impaired ubiquinone functionality at the electron transport chain (Figure 4/Figure 8)

A general link between persister formation and ETC functionality is well established; various mutations in ETC components can show both increased and decreased levels of persisters (Harms et al., 2016; Shan, Lazinski, Rowe, Camilli, & Lewis, 2015; Van den Bergh et al., 2016). However, the physiological basis of this link and the underlying molecular mechanisms are poorly understood. One possibility is that the ETC could modulate persister levels by affecting ATP production since persister formation can be associated with decreased ATP levels (Shan et al., 2017). However, impaired electron transport upon PasT deficiency should then rather cause increased persister formation by limiting cellular ATP production. Alternatively, it has been hypothesized repeatedly that bacterial killing by various antibiotics is causally linked to the generation of ROS by a hyperactivated ETC in response to metabolic perturbations (Kohanski, Dwyer, & Collins, 2010; Yang, Bening, & Collins, 2017), though these ideas have been disputed by others (Keren, Wu, Inocencio, Mulcahy, & Lewis, 2013; Liu & Imlay, 2013). This view would suggest that the decreased antibiotic tolerance upon pasT deficiency is linked to drug‐induced ROS production and ultimately rooted in a general hypersensitivity to ROS. Consistently, mechanisms involved in reducing oxidative stress and increasing ROS detoxification have been linked previously to persister survival in E. coli CFT073 and other bacteria (Molina‐Quiroz, Lazinski, Camilli, & Levy, 2016; Nguyen et al., 2011).

Critically, none of these hypotheses can explain why the four E. coli strains investigated in this work as well as Salmonella Typhimurium share most phenotypes linked to pasT/ratA deficiency except for the persister defect that is specifically absent in the E. coli K‐12 MG1655 laboratory strain (Figure 2/Figure 4/Figure 6/Figure 7 and Figure A2/Figure A3/Figure A5/Figure A6 in Appendix 2). Also, the E. coli K‐12 ΔratAB mutant did not show the modest defect in exponential‐phase ubiquinone biosynthesis that was readily apparent for E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI (Figure 5d). Before testing the other strains beyond E. coli K‐12 and CFT073, we initially suspected that the widespread use of strains carrying rpoS loss‐of‐function alleles (rpoSam) as E. coli CFT073 “wild‐type” might explain the increased sensitivity of this strain compared to K‐12 MG1655 (Hryckowian, Baisa, Schwartz, & Welch, 2015; Hryckowian & Welch, 2013) since RpoS is a central player in E. coli stress responses (Battesti, Majdalani, & Gottesman, 2011). Targeted sequencing of rpoS indeed confirmed that our E. coli CFT073 strain carried the rpoSam allele. However, control experiments with a variant carrying intact rpoS found no differences in antibiotic tolerance and all other phenotypes to our original data beyond a change in the dynamics of H2O2 survival that in this strain look much more similar to E. coli K‐12 MG1655 (Figure A7 in Appendix 2). These results suggest that RpoS‐controlled stress responses can buffer against some of the distortions of bacterial physiology that are caused by a lack of PasT but do not explain the severe defect of E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI in antibiotic tolerance. Given that this defect and all other phenotypes are also shared by different pathogenic E. coli as well as Salmonella Typhimurium (Figure A3/Figure A5/Figure A6 in Appendix 2), it is likely to be more representative of enterobacteria while the divergent behavior of E. coli K‐12 MG1655 might be related to one or more features of the peculiar physiology of this laboratory‐adapted strain (Hobman, Penn, & Pallen, 2007).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Cinzia Fino: Conceptualization (supporting); data curation (lead); formal analysis (lead); investigation (lead); validation (equal); visualization (equal); methodology (equal); resources (equal); writing—original draft preparation (equal); writing—review and editing (equal). Martin Vestergaard: Data curation (supporting); formal analysis (supporting); investigation (supporting); resources (supporting); methodology (supporting); writing—original draft preparation (supporting); writing—review and editing (supporting). Hanne Ingmer: Conceptualization (supporting); writing—review and editing (supporting); funding acquisition (supporting); supervision (supporting). Fabien Pierrel: Conceptualization (supporting); data curation (supporting); formal analysis (supporting); funding acquisition (supporting); investigation (supporting); methodology (supporting); resources (supporting); writing—original draft preparation (supporting); writing—review and editing (supporting). Kenn Gerdes: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); funding acquisition (lead); project administration (lead); supervision (equal); writing—original draft (equal); writing—review and editing (equal). Alexander Harms: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); funding acquisition (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); resources (equal); supervision (equal); validation (equal); visualization (equal); writing—original draft (equal); writing—review and editing (equal).

ETHICS STATEMENT

None required.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Nick R. Thomson, Eva Heinz, Gal Horesh, and Anders Løbner‐Olesen for valuable input and critical reading of the manuscript. Escherichia coli strain CFT073 with and without the inactive rpoSam allele was generously shared by Anders Løbner‐Olesen and Daniel R. Brown, respectively. Escherichia coli strain 55989 and Salmonella enterica serovar enterica Typhimurium SR‐11 were obtained from Karen A. Krogfelt, and an attenuated variant of E. coli O157:H7 strain EDL933 was obtained from Anders Løbner‐Olesen. This work was supported by Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF) grant DNRF120 and a Novo Nordisk Foundation Laureate Research Grant (to K.G.). A.H. was supported by the European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO) Long‐Term Fellowship ALTF 564‐2016 and Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) Ambizione Fellowship PZ00P3_180085.

Appendix 1.

TABLE A1.

List of all strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source/description |

|---|---|---|

| CF323 | Escherichia coli K‐12 MG1655: F– λ– ilvG – rfb‐50 rph‐1 | Wild‐type strain; Gerdes laboratory collection |

| EG94 | E. coli K‐12 MG1655 ΔhipAB::FRT pBAD33 ParaB:: SD4 atg hipA | MG1655 hipAB::FRT harboring pBAD33 ParaB:: SD4 atg hipA (Germain et al., 2013) |

| CF083 | E. coli K‐12 MG1655 ΔratAB | This study; derivative of E. coli K‐12 MG1655 with scarless deletion of ratAB |

| CF002 | Escherichia coli CFT073: hly+ pap1+ sfa1+ pil1+ (rpoSam) | Obtained from Anders Løbner‐Olesen; a 5 bp duplication (TAGAG) at the 3′ end of c3307 ORF causes a frameshift and premature amber stop codon in rpoS as reported earlier (Hryckowian et al., 2015); used throughout most of this study |

| CF069 | E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI (rpoSam) | This study; derivative of CF002 with scarless deletion of pasTI; used throughout most of this study |

| CF370 | E. coli CFT073 (intact rpoS) | E. coli CFT073 wild‐type with intact rpoS; obtained from Daniel R. Brown, Imperial College London (UK) |

| CF378 | E. coli CFT073 ΔpasTI (intact rpoS) | This study; derivative of CF370 with scarless deletion of pasTI |

| ALO3978 | E. coli GM9255 EDL933 (933w Δstx2AB::kan) | Anders Løbner‐Olesen laboratory collection; attenuated version of E. coli O157:H7 strain EDL933 with deletion of the Shiga toxin (Marinus & Poteete, 2013) |

| CF583 | EDL933 ΔpasTI | This study; derivative of ALO3978 with scarless deletion of pasTI |

| CF555 | E. coli 55989 | Obtained from Karen A. Krogfelt, Roskilde University (DK) |

| CF598 | E. coli 55989 ΔpasTI::FRT | This study; derivative of CF555 after disruption of pasTI locus with an FRT‐kmFRT selectable cassette, then flipped out |

| CF557 | Salmonella enterica serovar enterica str. SR‐11 | Obtained from Karen A. Krogfelt, Roskilde University (DK) |

| CF587 | SR‐11 ΔpasTI | This study; derivative of CF557 with scarless deletion of pasTI |

| CF574 | E. coli K‐12 MG1655 ΔubiA::cat | Pierrel laboratory collection (Pelosi et al., 2019) |

| CF575 | E. coli K‐12 MG1655 ΔubiX::km | Pierrel laboratory collection (Pelosi et al., 2019) |

TABLE A2.

List of all plasmids used in this study

| Identifier | Plasmid | Genotype/selection | Source/description/construction |

|---|---|---|---|

| n.a. | pNDM220 | mini‐R1 ori; bla; lacIq; Plac promoter. Amp 30 µg/ml | Gerdes laboratory collection |

| n.a. | pBAD33 | pA15 ori; cat; araC; ParaB promoter. Cam 25 µg/ml | Gerdes laboratory collection |

| n.a. | pWRG99 | TS ori; bla; ParaB promoter; λred. Amp 100 µg/ml | (Blank et al., 2011); recombineering plasmid |

| n.a. | pKO4/pELO4 | Cam 25 µg/ml | (Lee et al., 2001); template plasmid for amplification of the cat‐sacB cassette for recombineering |

| n.a. | pKM208 | TS ori; bla; Plac promoter; λred Amp 100 µg/ml | (Murphy & Campellone, 2003); recombineering plasmid |

| n.a. | pCP20 | TS ori; bla; Amp 100 µg/ml | Gerdes laboratory collection; plasmid used to flip out the resistance cassette upon expression of the flippase (FLP) at 30°C |

| n.a. | pKD3 | Amp 30 µg/ml; Cam 25 30 µg/ml | Gerdes laboratory collection; template plasmid for amplification of the FRT‐cat‐FRT cassette for recombineering |

| n.a. | pKD13 | Amp 30 µg/ml; Km 25 30 µg/ml | Gerdes laboratory collection; template plasmid for amplification of the FRT‐km‐FRT cassette for recombineering |

| n.a. | pAH186_ColE1 | ColE1 ori; bla; lacIq; Plac promoter. Amp 100 µg/ml | This study; derivative of pNDM220 with ColE1 ori (copy number 15‐20) instead of mini‐R1; the ColE1 ori was amplified from pBR322 (our collection) with primers prAH1206/prAH1207, and a fragment comprising bla‐lacIq‐Plac was amplified from pNDM220 with primers prAH1202/prAH1203; the PCR products were ligated after restriction digest with NsiI and HindIII |

| n.a. | pAH186_SC101 | SC101 ori; bla; lacIq; Plac promoter. Amp 100 µg/ml | This study; derivative of pNDM220 with SC101 ori (copy number ~5) instead of mini‐R1; the SC101 ori was amplified from pUA139 (Zaslaver et al., 2006) with primers prAH1204/prAH1205, and a fragment comprising bla‐lacIq‐Plac was amplified from pNDM220 with primers prAH1202/prAH1203; the PCR products were ligated after restriction digest with NsiI and HindIII |

| Inducible pasT (low copy) | pCF001_pasT_v1 | Derivative of pNDM220 encoding pasT. Amp 30 µg/ml | This study; the pasT ORF was amplified from E. coli CFT073 with a strong RBS and a GTG SC (AGGAGAaacaattttGTG) using primers prCF070/prCF071 and ligated into pNDM220 downstream Plac after digestion of backbone and insert with BamHI/EcoRI. The GTG has been converted into ATG by site‐directed mutagenesis using primers prCF291/prCF292. IPTG induction of pasT expression. |

| Inducible pasT (high copy) | pAH186_ColE1_pasT_v1 | Derivative of pAH186_ColE1 encoding pasT . Amp 100 µg/ml | This study; the pasT ORF was amplified from E. coli CFT073 with a strong RBS and a GTG SC (AGGAGAaacaattttGTG) using primers prCF070/prCF071 and ligated into pAH186_ColE1 downstream Plac after digestion of backbone and insert with BamHI/EcoRI. The GTG has been converted into ATG by site‐directed mutagenesis using primers prCF291/prCF292. IPTG induction of pasT expression |

| Inducible pasT (medium copy) | pAH186_SC101_pasT_v1 | Derivative of pAH186_SC101 encoding pasT . Amp 100 µg/ml | This study; the pasT ORF was amplified from E. coli CFT073 with a strong RBS and a GTG SC (AGGAGAaacaattttGTG) using primers prCF070/prCF071 and ligated into pAH186_SC101 downstream Plac after digestion of backbone and insert with BamHI/EcoRI. The GTG has been converted into ATG by site‐directed mutagenesis using primers prCF291/prCF292. IPTG induction of pasT expression |

| pdoc | pAH154_doc_v2 | Derivative of pNDM220 encoding doc. Amp 30 µg/ml | This study; the ORF of doc was amplified from bacteriophage P1vir with a weak RBS (ATTCCTCCaacaattttATG) using primers prAH1542/prAH1541 and ligated into pNDM220 downstream Plac after digestion of backbone and insert with KpnI/XhoI. IPTG induction of doc expression |

| ppasTI | pCF006_pasTI_v1 | Derivative of pNDM220 encoding pasTI. Amp 30 µg/ml | This study; pasTI operon including ≈300 bp upstream was amplified from E. coli CFT073 using primers prCF222/prCF223 and ligated into pNDM220 after digestion of backbone and insert with BamHI/EcoRI. V1 = strong SD and original SC (ATG). Expression of pasTI under endogenous transcriptional control |

| pratAB | pCF006_ratAB_v1 | Derivative of pNDM220 encoding ratAB. Amp 30 µg/ml | This study; ratAB operon including ≈300 bp upstream was amplified from E. coli MG1655 using primers prCF222/prCF224 and ligated into pNDM220 after digestion of backbone and insert with BamHI/EcoRI. V1 = strong SD and original SC (ATG). Expression of ratAB under endogenous transcriptional control |

| ppasT | pCF006_pasT_v1 | Derivative of ppasTI (pCF006_pasTI_v1) encoding only pasT. Amp 30 µg/ml | This study; pasI ORF was deleted from ppasTI by site‐directed mutagenesis using primers prCF236/prCF237 |

| pratA | pCF006_ratA_v1 | Derivative of pratAB (pCF006_ratAB_v1) encoding only ratA. Amp 30 µg/ml | This study; ratB ORF was deleted from pratAB by site‐directed mutagenesis using primers prCF236/prCF240 |

| pratB | pCF006_ratB_v1 | Derivative of pratAB (pCF006_ratAB_v1) encoding only ratB. Amp 30 µg/ml | This study; ratA ORF was deleted from pratAB by site‐directed mutagenesis using primers prCF238/prCF239 |

| pCC1736 | pCF007_cc1736_v1 | Derivative of pNDM220 encoding cc1736. Amp 30 µg/ml | This study; codon‐optimized cc1736 ORF was synthesized by GenScript, amplified using primers prCF256/prCF257, and ligated into pNDM220 downstream of Plac after digestion of backbone and insert with BamHI/XhoI digestion. V1 = strong RBS and original start codon (CTG). IPTG induction of cc1736 expression |

| pCOQ10 | pCF007_coq10_v4 | Derivative of pNDM220 encoding coq10A. Amp 30 µg/ml | This study; codon‐optimized coq10 ORF (isoform A) was synthesized by GenScript, amplified using primers prCF259/prCF290, and ligated into pNDM220 downstream Plac after digestion of backbone and insert with BamHI/XhoI. V4 = N‐terminus truncated variant. IPTG induction of coq10A expression |

| ppasI | pCF003_pasI_v1 | Derivative of pBAD33 encoding pasI. Cam 25 µg/ml | This study; pasI ORF was amplified from E. coli CFT073 with a strong RBS and a GTG SC (AGGAGAaacaattttGTG) using primers prCF166/prCF251 and ligated into pBAD33 downstream ParaB after digestion of backbone and insert with HindIII/XbaI. Arabinose induction of pasI expression. V1 = original SC (GTG) and strong RBS |

| phipA | pBAD33 ParaB:: SD4 atg hipA | Derivative of pBAD33 encoding hipA. Cam 25 µg/ml | Gerdes laboratory collection. hipA ORF was amplified from E. coli K‐12 MG1655 with a strong RBS and an ATG SC (AAGGAaaaaATG) using primers OEG89/OEG60 (Germain et al., 2013) and ligated into pBAD33 downstream ParaB promoter after digestion of backbone and insert with XbaI/SphI. Arabinose induction of hipA expression |

Abbreviations: Amp, Ampicillin; araC, encodes the regulator of ParaB; bla, β‐lactamase‐encoding cassette; Cam, Chloramphenicol; cat, Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase; IPTG, Isopropyl β‐d‐1‐thiogalactopyranoside; Kan, Kanamycin; lacIq, encodes the repressor of Plac (allele with strong lacI expression); ori, plasmid origin of replication; ParaB, promoter inducible with L‐arabinose; Plac, Promoter inducible with IPTG; RBS, Ribosome binding site; SC, Start codon; TS, temperature‐sensitive; λred, recombineering system.

TABLE A3.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligo name | Sequence | Description |

|---|---|---|

| pasTI/ratAB deletion | ||

| prCF025 | GTGCTCAATGAGCACCTTTTTTCTGTCTGTTATTTATTCGCTGATTTTTCCTGGTGTC CCTGTTGATACC | rv. MG1655/CFT073. Amplification of cat‐sacB cassette. Homology to the cassette is highlighted |

| prCF026 | CCGATGTTACCCAGCGCCGGGATAGCGTTTTTTTTACAGCAGGATAAATGGGAAAA CTGTCCATATGCAC | fw. MG1655/CFT073. Amplification of cat‐sacB cassette; Homology to the cassette is highlighted |

| prCF027 | AGCACCTTTTTTCTGTCTGTTATTTATTCGCTGATTTTTCCATTTATCCTGCTGTAAAA AAAACGCTATCCCGGCGCTGG | rv. MG1655/CFT073. Scarless deletion of the cat‐sacB cassette |

| prCF028 | CCAGCGCCGGGATAGCGTTTTTTTTACAGCAGGATAAATGGAAAAATCAGCGAAT AAATAACAGACAGAAAAAAGGTGCT | fw. MG1655/CFT073. Scarless deletion of the cat‐sacB cassette |

| prCF323 | GTGCTCAATGAGCACCTTTTTTCTGTCCGTTATTTATTCGCTGATTTTTCCTGGTGTC CCTGTTGATACC | rv. EDL933. Amplification of cat‐sacB cassette. Homology to the cassette is highlighted |

| prCF324 | GGATGTTACCCAGCGCCGGGATAGCGTTTTTTTTACTGCAGGATAAATGGGAAAAC TGTCCATATGCAC | fw. EDL933. Amplification of cat‐sacB cassette. Homology to the cassette is highlighted |

| prCF325 | AGCACCTTTTTTCTGTCCGTTATTTATTCGCTGATTTTTCCATTTATCCTGCAGTAAA AAAAACGCTATCCCGGCGCTGG | rv. EDL933. Scarless deletion of the cat‐sacB cassette |

| prCF326 | CCAGCGCCGGGATAGCGTTTTTTTTACTGCAGGATAAATGGAAAAATCAGCGAATA AATAACGGACAGAAAAAAGGTGCT | fw. EDL933. Scarless deletion of the cat‐sacB cassette |

| prCF329 | CCACACCGTTATCCGGCAAAAGAGGCTAATTATCTGCCAGCCGATTTTTCCTGGTGT CCCTGTTGATACC | rv. SR11. Amplification of cat‐sacB cassette. Homology to the cassette is highlighted |

| prCF330 | ATTAAGGCATGACGGTTGGGGACAGCATTTTTTTTACTCGCTGATAAGTGGGAAAA CTGTCCATATGCAC | fw. SR11. Amplification of cat‐sacB cassette. Homology to the cassette is highlighted |

| prCF331 | ATCCGGCAAAAGAGGCTAATTATCTGCCAGCCGATTTTTCCACTTATCAGCGAGTA AAAAAAATGCTGTCCCCAACCGTC | rv. SR11. Scarless deletion of the cat‐sacB cassette |

| prCF332 | GACGGTTGGGGACAGCATTTTTTTTACTCGCTGATAAGTGGAAAAATCGGCTGGCA GATAATTAGCCTCTTTTGCCGGAT | fw. SR11. Scarless deletion of the cat‐sacB cassette |

| prCF231 | GTGCTCAATGAGCACCTTTTTTCTGTCTGTTATTTATTCGCTGATTTTTCTGTAGGCT GGAGCTGCTTCG | rv. 55989. Amplification of FRT‐km‐FRT cassette. Homology to the cassette is highlighted |

| prCF232 | CCGATGTTACCCAGCGCCGGGATAGCGTTTTTTTTACAGCAGGATAAATGATTCCG GGGATCCGTCGACC | fw. 55989. Amplification of FRT‐km‐FRT cassette. Homology to the cassette is highlighted |

| prCF023 | GAACTATCTGACCGCTAACGAC | rv. Screening pasTI/ratAB locus |

| prCF024 | GTCGCGCAGAAGGAC | fw. Screening pasTI locus |

| prCF033 | GAAATGCCTCTCCGTCAC | fw. Screening ratAB locus and pasTI locus of 55989 |

| prCF327 | GGAACTATCTTACACCTACGGAT | rv. SR11. Screening pasTI locus |

| prCF328 | CGCCATCTTTGAGGATAAC | fw. SR11. Screening pasTI locus |

| pCF001_pasT_v1 construction and related plasmids | ||

| prCF070 | CCCGAGGGATCCAGGAGAAACAATTTTGTGATATTATTTGTTGGATTTTTGTTG | fw. Amplification of pasT gene. BamHI RS |

| prCF071 | GGGCTCGAATTCTTACCTGGCACTGTAGACCTC | rv. Amplification of pasT gene. EcoRI RS |

| prCF291 | ACAATTTTATGATATTATTTGTTGGATTTTTGTTG | fw. GTG to ATG conversion |

| prCF292 | TAATATCATAAAATTGTTTCTCCTGGATCC | rv; GTG to ATG conversion |

| pCF006_pasTI_v1 and pCF006_ratAB_v1 construction | ||

| prCF222 | ACCGAGGGATCCAGGAGAAACAATTTTGGACATAGCTGTCGCTGATA | fw. Amplification of pasTI operon. BamHI RS |

| prCF223 | GGGCTCGAATTCTTATTTATTCGCTGATTTTTCTG | rv. Amplification of pasTI/ratAB operon. EcorI RS |

| prCF224 | ACCGAGGGATCCAGGAGAAACAATTTTGGACGTAGCTGTCGCTG | fw. Amplification of ratAB operon. BamHI RS |

| pCF006_pasT_v1 and pCF006_ratA_v1 construction | ||

| prCF236 | TGCCAGGTAAGAATTCACTGGCCGTCG | fw. Deletion of pasI/ratB from pCF006_pasTI/ratAB_v1 |

| prCF237 | AGTGAATTCTTACCTGGCACTGTAGACCTC | rv. Deletion of pasI from pCF006_pasTI_v1 |

| prCF240 | AGTGAATTCTTACCTGGCACTGTAAACCTC | rv. Deletion of ratB from pCF006_ratAB_v1 |

| pCF006_ratB_v1 construction | ||

| prCF238 | AGCAGGATAAGTGCCAGGTAAAATTGCC | fw. Deletion of ratA from pCF006_ratAB_v1 |

| prCF239 | TACCTGGCACTTATCCTGCTGTAAAAAAAACG | rv. Deletion of ratA from pCF006_ratAB_v1 |

| pCF003_pasI_v1 construction | ||

| prCF166 | GGGCTGAAGCTTTTATTTATTCGCTGATTTTTCTG | rv. Amplification of pasI. HindIII RS |

| prCF251 | CCCGAGTCTAGAAGGAGAAACAATTTTGTGCCAGGTAAAATTGCC | fw. Amplification of pasI. XbaI RS |

| pCF007_cc1736_v1 construction | ||

| prCF256 | CCCGAGGGATCCAGGAGAAACAATTTTCTGCACCGTCACGTGG | fw. Amplification of cc1736. BamHI RS |

| prCF257 | GGGCTCCTCGAGTTACGCACCATGCAGTTG | rv. Amplification of cc1736. XhoI RS |

| pCF007_coq10_v4 construction | ||

| prCF259 | GGGCTCCTCGAGTTAGGTTTGGTGAACTTCGT | rv. Amplification of coq10A. XhoI RS |

| prCF290 | CAAGAGGGATCCAGGAGAAACAATTTTATGGCGTACAGCGAGCGT | fw. Amplification of coq10A. BamHI RS |

| Others | ||

| prAH_pNDM220 | AAAACAGGAAGGCAAAATGC | fw. Screening for cloning in pNDM220 |

| prAH500 | CTGTTTTATCAGACCGCTTC | Rv. Screening for cloning in pNDM220 and pBAD33 |

| prAH501 | CGTCACACTTTGCTATGCC | fw. Screening for cloning in pBAD33 |

| prCF262 | GTTGTTTATGCCGGTAACG | fw. rpoS sequencing |

| prCF263 | CAATTACTGTGCGCTTAAAATG | rv. rpoS sequencing |

| prAH1541 | GCCTTCCCTCGAGCTACTCCGCAGAACCATACAA | rv. Amplification of doc from phage P1vir. XhoI RS |

| prAH1542 | CGAGTGGGTACCATTCCTCCAACAATTTTATGAGGCATATATCACCGGA | fw. Amplification of doc from phage P1vir. KpnI RS |

| prAH1202 | GACGCCAAGCTTCCTAGATCCTTTTAAATTAAAAATGAAG | fw. pNDM220 for pAH186 series |

| prAH1203 | CTCCCGGATGCATGAAGCATAAAGTGTAAAGCCTG | rv. pNDM220 for pAH186 series |

| prAH1204 | GACGCCATGCATCCGCTGTAACAAGTTGTCTC | fw. SC101 for pAH186 series |

| prAH1205 | CTCCCGGAAGCTTCGCTTGGACTCCTGTTG | rv. SC101 for pAH186 series |

| prAH1206 | GAGCGGATGCATAGTGATTTTTCTCTGGTCCC | fw. ColE1 for pAH186 series |

| prAH1207 | CTCCGCCAAGCTTCCCGTAGAAAAGATCAAAGG | rv. ColE1 for pAH186 series |

| prAH1805 | GGTTGTCTGCAGCATAAAGTGTAAAGCCTGGGG | rv. pNDM220 inserts into pAH160‐Plac |

Abbreviations: fw, Forward primer; rv, Reverse primer.

TABLE A4.

Genomes used for the synteny analysis of Figure 3

| Organism | Strain | GenBank/RefSeq accession number |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | str. K‐12; substr. MG1655 | U00096.3/NC_000913.3 |