Introduction

Currently, there is a paucity of data on the cardiac manifestations of the novel coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). We present a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia complicated by hypotension and cytokine storm, followed by viral myocarditis mimicking features of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Rapid improvement of cardiac function after treatment highlights the importance of obtaining early cardiac biomarkers and noninvasive imaging in this patient population. We also illustrate that cardiac involvement may occur with COVID-19 cases that have predominantly respiratory tract signs and symptoms.

Case report

A 76-year-old woman who presented with subjective fevers, nonproductive cough, and dyspnea was admitted to the intensive care unit for acute hypoxic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 infection. On examination, her blood pressure was 110/53 mm Hg, pulse rate was 124 beats/min and regular, respiratory rate was 31 breaths/min, oxygen saturation was 79% on 10 L oxygen nasal cannula, her temperature was 102.3°F, and she was in severe respiratory distress. Cardiovascular examination revealed tachycardia. Lung exam revealed diffusely decreased breath sounds and crackles. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Medical history

The patient’s medical history was notable for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hypothyroidism.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of acute dyspnea with hypoxia in a 73-year-old woman is broad. COVID-19-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome was a major concern. Other differential diagnoses were acute pulmonary embolism, acute heart failure, septic shock, cardiac tamponade, acute coronary syndrome, viral pneumonia from other pathogens, bacterial pneumonia, and viral cardiomyopathy.

Investigations

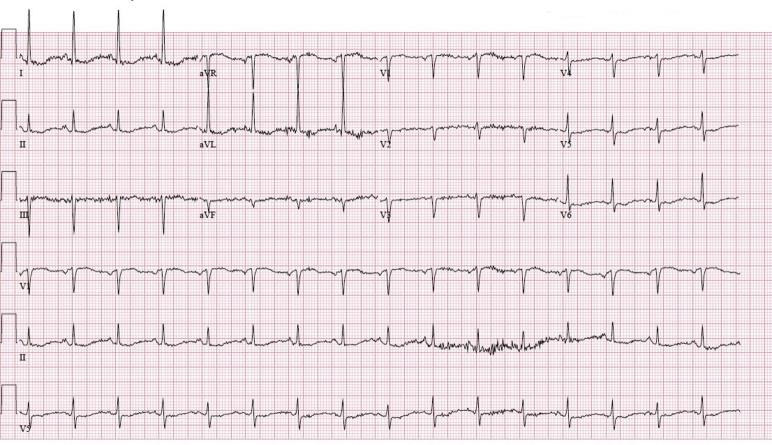

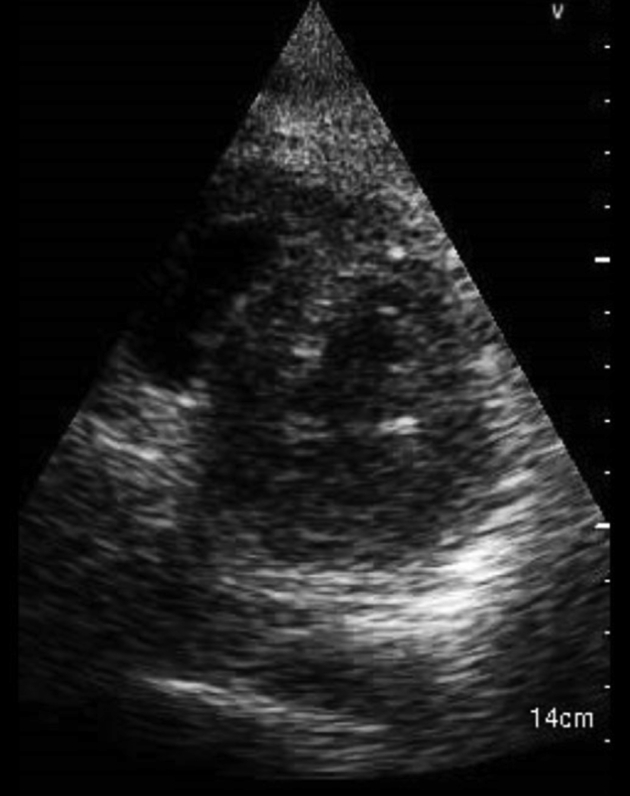

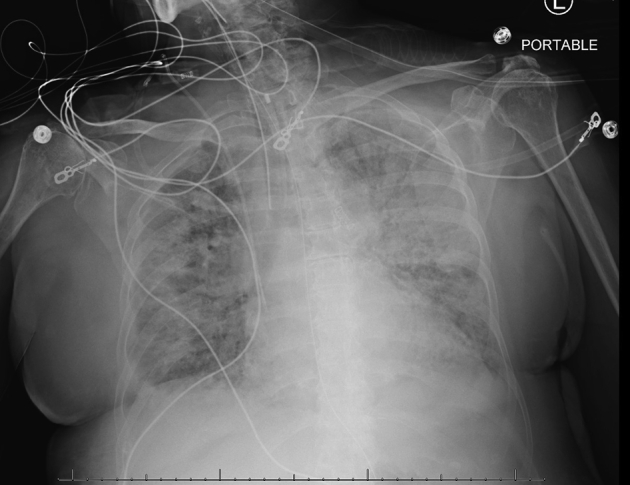

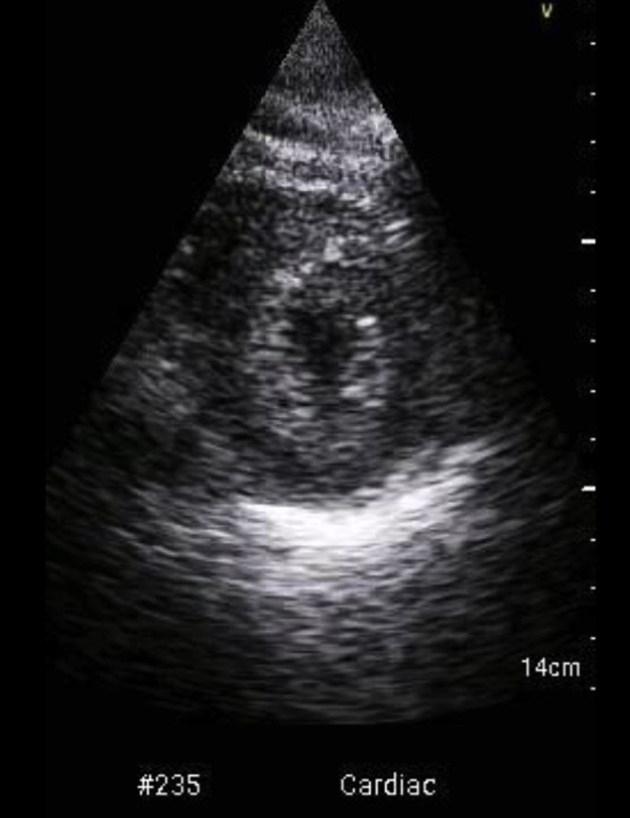

Results of laboratory testing during initial hospital admission were the following: potassium 2.2 mEQ/L (3.5–5.0 mEQ/L), creatinine 1.79 mg/dL (0.7–1.3 mg/dL), C-reactive protein 23.10 mg/L (0.0–0.8 mg/dL), interleukin-6 (IL-6) 781.46 mg/L (0–12.4 mg/L), lactate dehydrogenase 334 U/L (60–100 U/L), ferritin 457 ng/mL (15–200 ng/mL), procalcitonin 15.20 ng/mL (0.10–0.49 ng/mL), prothrombin time 18.9 seconds (11–13 seconds), fibrinogen >600 mg/dL (150–350 mg/dL), white blood cell count 16.1 cells/L (4000–10,000 cells/μL) with 92.7% neutrophils, IgG 1622 mg/dL (700–1600 mg/dL). The patient tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Initially, the troponin was 0.03 ng/dL; however, high-sensitivity troponin peaked later in the hospital course at 503 ng/L (<14 ng/L for women) and proBNP was 35,000 pg/mL (<450 pg/mL). These values indicated extraordinarily high levels of these serum enzymes. A chest radiograph showed diffuse bilateral pulmonary edema vs infiltrates (Supplemental Figure 1). A repeat chest radiograph revealed worsening diffuse bilateral pulmonary opacities/infiltrates vs edema (Figure 1). An electrocardiogram showed no signs of ischemia, normal sinus rhythm with a short PR interval of 72 ms, left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy, and a QTc interval of 680 ms (Supplemental Figure 2). Previous echocardiograms from prior hospitalizations and initially on admission showed a normal LV ejection fraction (LVEF) and no wall motion abnormalities. Now, a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) revealed a severely decreased LV systolic function with segmental wall motion abnormalities, akinesis of the distal segments of the left ventricle with relatively preserved function at the base, and akinesis of the mid and distal portions of the right ventricle with preserved function at the base of the free wall as well as an ejection fraction (EF) of 25%–30% (normal range >50%) (Figure 2, Supplemental Figure 3, Supplemental Videos 1–3).

Figure 1.

Chest radiograph 2 days after intubation with worsening bilateral pulmonary opacities vs edema.

Figure 2.

Initial transthoracic echocardiogram of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, parasternal long-axis view.

Management

The patient was intubated for respiratory distress and hypoxic respiratory failure. At that time, a limited bedside TTE was conducted to evaluate the thoracic structures and overall hemodynamic state of the patient, which revealed a normal cardiac EF of 55%. She was found to be in a shock state and required vasopressor support with norepinephrine. This was followed by initiation of the ARDSnet protocol. The patient was treated with 2 doses of tocilizumab (480 mg and 240 mg), intravenous immunoglobulin (25 g for 5 days), ceftriaxone, cefdinir, and cefepime owing to cytokine storm from COVID-19 and leukocytosis. She was not treated with hydroxychloroquine or azithromycin owing to a prolonged QTc interval.

A repeat chest radiograph (Figure 1) revealed worsening bilateral airspace opacities vs vascular congestion, so the patient was treated with intravenous furosemide 40 mg. At this time, cardiac enzymes were found to be elevated. A repeat bedside TTE was performed and revealed an LVEF of 20%–25%. The resulting findings created concern for severe viral myocarditis, so the patient was transferred to a tertiary center for possible advanced management. At the facility, a complete 2D echocardiogram revealed an LVEF of 25%–30% along with wall motion abnormalities (Supplemental Videos 1–3). Her non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction was suspected to be secondary to a viral cardiomyopathy, but she was treated with therapeutic enoxaparin as a precaution.

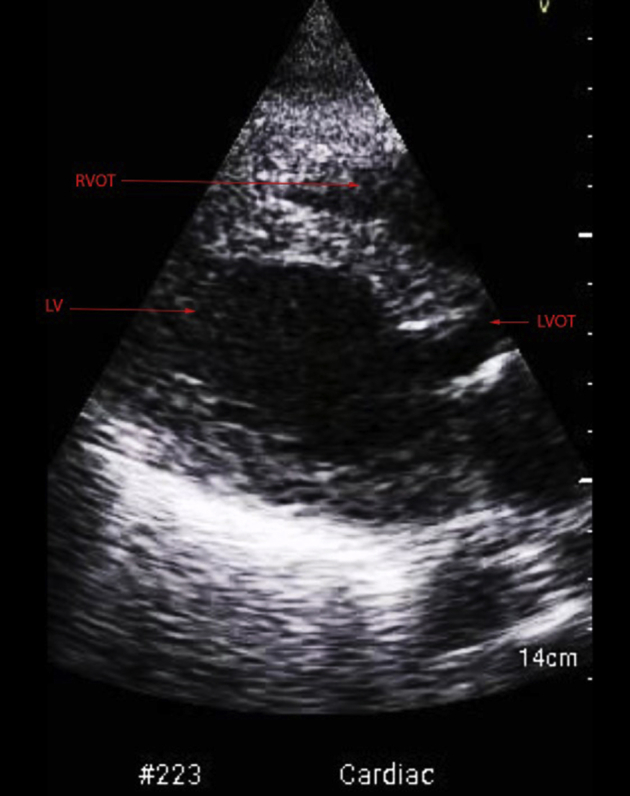

After completion of tocilizumab, and within 2 days of completing intravenous immunoglobulin, her LVEF recovered to 50% on TTE, with overall mildly reduced LV systolic function, mid-septal and apical hypokinesis, and mildly reduced right ventricular function (Figure 3, Supplemental Figure 4, Supplemental Videos 4–6). Blood and respiratory cultures were negative. Inflammatory markers greatly improved but then worsened again. IL-6, however, continued to downtrend from 781.46 mg/L to 171.82 mg/L 2 days after the completion of treatment. A decrease in the level of high-sensitivity troponin from 503 ng/L to 418 ng/L was also observed. She was not a candidate for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation owing to her advanced age. After improvement of her LVEF, the patient was transferred back to our intensive care unit.

Figure 3.

Follow-up transthoracic echocardiogram showing resolution of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, parasternal long-axis view.

Discussion

After the first case of COVID-19 occurred in Wuhan, China, SARS-CoV-2 swiftly spread worldwide and became a pandemic. The data of 1527 patients with SARS-Cov-2-induced (COVID-19) infection from China’s Center for Disease Control revealed that mortality and morbidity rates have been as high as 16.4% in patients with hypertension and 17.1% in patients who have other cardiovascular disease.1, 2, 3

Virus infection is known to be one of the most common causes of myocarditis.3 Acute myocardial injury has increasingly been observed as an initial cardiac complication of COVID-19.2 For our patient, there was concern for direct myocardial injury because SARS-CoV-2 can enter cardiac myocytes by binding to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, thus disrupting the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 signaling pathways leading to injury of cardiac myocytes.1 Findings of severely reduced LV systolic function, SARS-CoV-2-positive status, and signs and symptoms of infection alluded to a viral-induced myocarditis.2,4 However, certain aspects on TTE, such as apical ballooning, made Takotsubo cardiomyopathy a part of our differential diagnosis. The right ventricle, though, is rarely involved in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and viral myocarditis can present with regional wall motion abnormalities. Thus, our patient was diagnosed with a viral myocarditis with features mimicking Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

The American College of Cardiology recently released an advisory discouraging random measurement of cardiac biomarkers such as troponins and brain natriuretic peptides.2 However, having these measurements was important, as they revealed a significant degree of cardiac injury secondary to COVID-19 and informed our management plan, ultimately prompting a transfer to a tertiary care center. These findings suggest that patients, such as ours with severe symptoms, could have complications involving acute myocardial injury5 contributing to their hemodynamic instability and shock state.

Patients demonstrating heart failure, arrhythmia, electrocardiogram changes, or cardiomegaly should have echocardiography despite the cautious use of imaging for patients with COVID-19.3 The echocardiogram helped us better diagnose our patient and transfer her to a higher level of care. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging or cardiac biopsy was not performed to limit exposure. These diagnostic studies would have been helpful in distinguishing between myocarditis and Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Viral myocarditis is distinguished by the presence of many inflammatory cells and interstitial edema on examination of an endomyocardial biopsy specimen, and a gadolinium enhancement pattern on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.6

Our patient was managed with several medications with anti-inflammatory properties. These treatments helped reduce her myocardial injury and allowed for LVEF recovery. Proposed mechanisms of myocardial and lung injury are cytokine storm, which has been theorized to be secondary to an imbalanced response by type 1 and type 2 T-helper cells, and increased activity of the Notch pathway that increases proliferation of IL-6.7 Tocilizumab is an immunosuppressive drug and an anti-human IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody, which blocks IL-6 from binding to its receptor, and as a result stunts the immune inflammatory response.8 Tocilizumab has been proven to be effective in treating patients with severe manifestations of COVID-19 by improving clinical symptoms and stunting deterioration.8

Furthermore, steroids are currently not being employed in the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome in COVID-19, but perhaps there is a role for them in patients with COVID-induced myocarditis without other contraindications.6 Employment of noninvasive techniques (bedside TTE and cardiac biomarkers) should be considered to assess hypotensive patients given the possibility of insidious and potentially deadly cardiac complications of COVID-19. More randomized trials are needed for each of these treatments to properly assess their impact on myocardial injury and cardiac dysfunction in patients with COVID-19.

Conclusions

Recognition of COVID-19-associated cardiac complications will be vital to early intervention, surveillance, and management of embattled patients, highlighting the importance of early cardiology involvement in patients developing cardiac complications secondary to COVID-19 infection during this pandemic.

Footnotes

Key Teaching Points.

-

•COVID-19 seems to have a multitude of cardiac manifestations, including myocarditis mimicking Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

-

•Hemodynamic instability in COVID-19 can be secondary to cardiac manifestations.

-

•The exact mechanism of SARS-CoV-2-induced myocardial injury is currently unknown, but perhaps there is a role for cardiac biomarkers and imaging for surveillance.

-

•Early use of anti-inflammatory medications can play a role in blunting cardiac injury secondary to SARS-CoV-2.

Appendix. Supplementary data

Initial Formal 2D Echo: Parasternal long axis view depicting EF of 25-30% with regional wall motion abnormalities.

: Initial Formal 2D Echo: Parasternal short axis view depicting EF of 25-30% with regional wall motion abnormalities.

Initial Formal 2D Echo: Apical four chamber view depicting EF of 25-30% with regional wall motion abnormalities. Akinesis of the distal segments of the left ventricle with relatively preserved function at the base, and akinesis of the mid and distal portions of the right ventricle with preserved function at the base of the free wall.

Post Treatment Formal 2D Echo: Parasternal long axis view depicting EF of 50-55%

Post Treatment Formal 2D Echo: Parasternal short axis view depicting EF of 50-55%.

Post Treatment Formal 2D Echo: Apical four chamber view depicting EF of 50-55%, with improvement in segmental wall motion abnormalities.

Supplemental Figure 1.

Chest x-ray after intubation.

Supplemental Figure 2.

Electrocardiogram after intubation.

Supplemental Figure 3.

Initial TTE of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, parasternal short axis view.

Supplemental Figure 4.

Follow-up TTE showing resolution of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, parasternal short axis view.

References

- 1.Inciardi RM, Lupi L, Zaccone G, et al. Cardiac involvement in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [published online ahead of print March 27, 2020]. JAMA Cardiol. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Bansal M. Cardiovascular disease and COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:247–250. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loscalzo J., Roy N., Shah R.V. Case 8-2018: A 55-year-old woman with shock and labile blood pressure. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1043–1053. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc1712225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kochi A.N., Tagliari A.P., Forleo G.B., Fassini G.M., Tondo C. Cardiac and arrhythmic complications in patients with COVID-19. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2020;31:1003–1008. doi: 10.1111/jce.14479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alhazzani W., Møller M.H., Arabi Y.M. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Intensive Care Med March. 2020:1–34. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Libby P. The heart in COVID19: primary target or secondary bystander? JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2020;5:537–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu X., Han M., Li T. Effective treatment of severe COVID-19 patients with tocilizumab. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:10970–10975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2005615117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Initial Formal 2D Echo: Parasternal long axis view depicting EF of 25-30% with regional wall motion abnormalities.

: Initial Formal 2D Echo: Parasternal short axis view depicting EF of 25-30% with regional wall motion abnormalities.

Initial Formal 2D Echo: Apical four chamber view depicting EF of 25-30% with regional wall motion abnormalities. Akinesis of the distal segments of the left ventricle with relatively preserved function at the base, and akinesis of the mid and distal portions of the right ventricle with preserved function at the base of the free wall.

Post Treatment Formal 2D Echo: Parasternal long axis view depicting EF of 50-55%

Post Treatment Formal 2D Echo: Parasternal short axis view depicting EF of 50-55%.

Post Treatment Formal 2D Echo: Apical four chamber view depicting EF of 50-55%, with improvement in segmental wall motion abnormalities.