Abstract

Introduction

Specific pre-existing medical conditions (e.g. hypertension or obesity), advanced age and male sex appear linked to more severe manifestations of SARS Co-V2 infection, thus raising the question of whether Parkinson's disease (PD) poses an increased risk of morbidity and mortality in COVID-19 patients.

Methods

In order to describe the outcome of COVID-19 in multi-centre a cohort of PD patients and explore its potential predictors, we gathered the clinical information of 117 community-dwelling patients with COVID-19 followed in 21 tertiary centres in Italy, Iran, Spain, and the UK.

Results

Overall mortality was 19.7%, with a significant effect of co-occurrence of dementia, hypertension, and PD duration.

Conclusions

The frailty caused by advanced PD poses an increased risk of mortality during COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, Dementia, Parkinson's disease, Outcome

Highlights

-

•

Specific pre-existing conditions are linked to worse COVID-19 outcome.

-

•

Whether Parkinson's disease (PD) poses an increased risk is unknown.

-

•

117 PD patients with COVID-19 from in 21 centres in 4 country were analyzed.

-

•

Mortality was 19.7%, with an effect of dementia, hypertension, and PD duration.

-

•

The frailty caused by advanced PD increased the risk of mortality during COVID-19.

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS Co-V2) emerged in the region of Wuhan in China around December last year and spread so rapidly that the World Health Organization declared coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) a pandemic on March 11, 2020. Although most infected subjects may be asymptomatic or only develop mild upper respiratory symptoms, severe manifestations occur, including acute respiratory distress syndrome eventually resulting in death [1]. In addition to anosmia and ageusia, severe other neurologic complications have been associated with human coronavirus infections. There is now evidence that SARS Co-V2 can directly involve the central nervous system as shown by the reported case of an encephalopathy in a 74-year-old also affected by Parkinson's disease (PD) [2].

Specific pre-existing medical conditions (e.g. hypertension or obesity), advanced age and male sex appear linked to more severe manifestations of the infection [1], thus raising the question of whether PD poses an increased risk of morbidity and mortality in COVID-19 patients. The first available evidence comes from a small series of 10 PD patients collected in Padua (Italy) and London (UK), which found a substantially high mortality rate (40%) and suggested that older age, longer disease duration and advanced therapies contribute to an increase risk of poor outcome [3].

In order to describe the outcome of COVID-19 in PD patients and explore its potential predictors, we gathered the clinical information of 120 community-dwelling PD patients with COVID-19 followed in 21 tertiary centres in Italy (14), Iran (5), Spain (1), and the UK (1), world regions that experienced a surge of the pandemic.

2. Methods

A standardized electronic case report form was used to collect anonymized demographic and clinical information. Patients were collected through a total of 2238 phone calls of PD patients (3 centres), access to all hospital records (8 centres) or when patients informed the treating neurologist (10 centres). COVID-19 diagnosis was confirmed by means of real-time PCR assay or when symptoms were compatible with COVID-19 and the patient has been in contact with a PCR-confirmed case (usually a family member). l-dopa and dopamine agonist doses were converted in l-dopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) [4]. Comorbidities known to influence COVID-19 outcome were also collected [1]. COVID-19 outcome was categorized as mild (i.e. not requiring hospitalization), requiring hospital admission, or death.

Normal data distribution was confirmed with Shapiro-Wilk test, continuous variables were compared with ANOVA using Bonferroni for post-hoc analyses while categorical data were compared with chi-square test applying Yates's correction. Due to a non-parametric distribution, the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables in a sub-analysis taking into account patients' geographical provenience.

The study followed ethical standards and the principles of Helsinki declarations but no approval was requested, in keeping with similar observational studies conducted at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic [3,5].

3. Results

Three patients were excluded due to duplicated report, missing information and treatment discontinuation at admission, resulting in a total sample of 117 patients (43 women, age: 71.4 ± 10.8 years, disease duration: 9.4 ± 5.8 years). The majority of patients (n = 99) were followed by Italian centres and their features were comparable to non-Italian PD patients with the exception of a younger age at study entry (Suppl Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical features of the 117 PD patients according to COVID-19 outcome.

| Mild (n = 57) | Admitted (n = 37) | Dead (n = 23) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 67.2 ± 10.5 | 73.3 ± 10.6 | 78.8 ± 6.6 | 0.092 |

| Males | 34 (59.6%) | 24 (64.9%) | 16 (69.6%) | 0.838 |

| PD duration (years) | 8.3 ± 5.0 | 9.6 ± 6.0 | 11.7 ± 6.6 | 0.053 |

| LEDD from DA (mg/day) | 82.2 ± 93.6 | 34.9 ± 78.1 | 77.4 ± 197.9 | 0.146 |

| LEDD from l-dopa (mg/day) | 557.6 ± 444.4 | 567.4 ± 363.5 | 823.6 ± 619.6 | 0.054 |

| Total LEDD (mg/day) | 639.8 ± 459.9 | 602.3 ± 372.9 | 901.0 ± 686.6 | 0.053 |

| DA | 30 (52.6%)a,b | 10 (27.0%)a | 5 (21.7%)b | 0.019 |

| Amantadine | 2 (3.5%) | 1 (2.7%) | 1 (4.3%) | 0.878 |

| iCOMT | 10 (17.5%) | 4 (10.8%) | 5 (21.7%) | 0.724 |

| Entacapone | 5 (8.7%) | 2 (5.4%) | 4 (17.4%) | 0.543 |

| DBS | 4 (7.0%) | 2 (5.4%) | 1 (4.3%) | 0.973 |

| LCIG | 2 (3.5%) | 2 (5.4%) | 3 (13.0%) | 0.529 |

| Active cancer | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.3%) | 0.748 |

| Cardiac issues | 3 (5.3%)a | 10 (27.0%)a | 5 (21.7%) | 0.029 |

| Dementia | 3 (5.3%) | 5 (13.5%) | 6 (26.1%) | 0.084 |

| Diabetes | 8 (14.0%) | 5 (13.5%) | 5 (21.7%) | 0.850 |

| Hypertension | 20 (35.1%) | 14 (37.8%) | 14 (60.9%) | 0.163 |

| Immunodeficiency* | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (2.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.864 |

| Obesity | 7 (12.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.3%) | 0.164 |

| Respiratory disorders | 5 (8.8%) | 4 (10.8%) | 1 (4.3%) | 0.908 |

Values are mean ± SD or n (%), significant data are bold-typed. Abbreviations: a = post hoc mild vs admitted patients (p < 0.03), b = post hoc mild vs dead patients (p < 0.03), *primary or secondary to immunosuppressants use, COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 19, DA = dopamine agonist (apomorphine, pramipexole, ropinirole, rotigotine), DBS = deep brain stimulation, iCOMT = COMT inhibitors (entacapone, opicapone, tolcapone), LCIG = l-dopa carbidopa intestinal gel, LEDD = l-dopa equivalent daily dose [4], PD = Parkinson's disease.

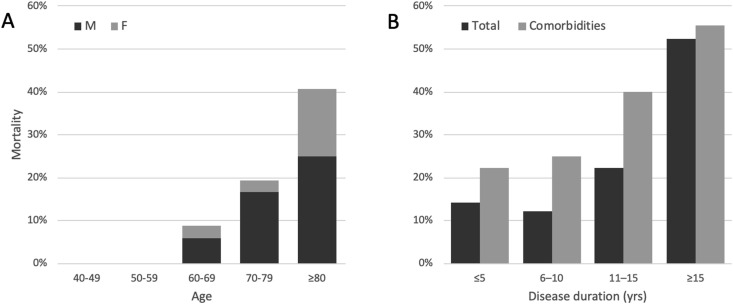

Dopamine agonists were more frequently used in mild patients (Table 1) but the effect was lost excluding patients older than the median age of the sample (<72 years, 58 patients, p = 0.47). Overall mortality was 19.7% (Fig. 1 ), with a significant effect of concomitant dementia (26.1% in deceased patients vs. 8.5% in mild/admitted cases, p = 0.049), PD duration (11.7 ± 8.8 vs. 6.6 ± 5.4 years, p = 0.029) and – as statistical trend – hypertension (63.6% vs. 37.6%, p = 0.054, Fig. 1B). Mortality of the Italian cohort was significantly lower than non-Italian patients (16.2% vs. 38.9%, p = 0.03, Suppl Table 1).

Fig. 1.

A. Mortality rate according to age group and sex in the total sample of 117 patients. B. Mortality rate according to Parkinson's disease duration in the total sample and the selected sample of 53 patients with hypertension and/or dementia (comorbidities).

4. Discussion

In this multi-centre cohort of PD patients with COVID-19 we detected an overall mortality of 20% and confirmed the role of known risk factors, such as advanced age and hypertension [1]. In addition, we confirmed that known causes of neurological frailty – such as advanced PD and co-occurrence of dementia, have a negative effect on COVID-19 outcome, as recently reported in a small series [3].

Recent epidemiological data suggest an overall COVID-19 mortality of 9.5% for all patients over 50 years of age, increasing to 12.8% for patients in their seventies [6]. Our study suggests that mortality rate is higher in PD patients compared to the general population and it is lower – and possibly more accurate – than the first reported figure for PD (40%), which was based on a selected series of only 10 patients [3]. Nonetheless, our mortality rate is probably inflated by the nature of our data collection. This is further confirmed by the sub-analysis of the Italian cohort, where mortality was slightly reduced (16.2%) and the overall outcome was better than non-Italian patients (Suppl Table 1), most likely because of the younger age of the former sample. In this regard, we recently conducted a single-centre case-controlled phone survey on 1486 Italian PD patients and reported a lower mortality rate (7.1%), similar to the 7.6% found in 1207 family members also interviewed [7]. On the other hand, this latter survey probably underestimated mortality as it could not reach patients living in nursing homes or other long-term care facilities, where outbreaks with high mortality rates have been reported [8]. In addition, some patients could not be reached for unknown reasons, thus raising the possibility of patient's death due to COVID-19.

Frailty has been shown to be common in PD, affecting 22.2% of community-based patients [9], and to have an impact on quality of life, morbidity and life expectancy. PD patients are nearly twice as likely to be admitted to hospital for disease complications, with pneumonia being the second commonest diagnosis in most of the studies [10]. Little information is available on the relationship between PD and pandemics. Of 631 UK patients hospitalized during the first pandemic wave of H1N1, neurological comorbidities failed to correlate with disease severity or duration of hospitalization [11]. A retrospective study of 397,453 patients aged ≥60 years with Parkinsonism found lower in-hospital mortality than those patients without Parkinsonism. However, length of stay was 8.1% longer in patients with Parkinsonism, who were also less likely to be discharged home. Higher age, lower body mass index, lower Barthel index, higher A-DROP (Age, Dehydration, Respiratory Failure, Orientation Disturbance, and Blood Pressure) score, and a Charlson comorbidity index ≥3 were significantly associated with higher in-hospital mortality [12]. In another retrospective study, mortality was 12.5% after ICU admission in 62 PD patients with sepsis and variable age, duration and severity of underlying conditions. A Hoehn and Yahr score >3 was associated with higher mortality, which also increased over the 18 months of follow-up, and only 38% of these patients returned home [13].

Patients with advanced PD with restricted pulmonary capacity due to axial akinesia are at higher risk for pulmonary decompensation [14]. Interestingly, in mouse models of coronavirus encephalitis, the virus can enter the brain trans-neuronally through the olfactory pathways and seropositivity for coronaviruses has been reported in a variety of neurological disorders, including PD [15]. Therefore, it has been argued that SARS Co-V2 might have a direct detrimental effect on bulbar respiratory centre [16].

COVID-19 pandemic has forced health systems to rapidly change priorities in medical care and research. Drug repurposing has been the first step in finding a suitable treatment for obvious advantages over developing an entirely new drug in the context of a rapidly spreading threat. During the past month a number of anti-PD drugs have been hypothesized to play a therapeutic role in COVID-19. The protective effect of dopamine combined with a detrimental effect of dopa decarboxylase (DCC) inhibitors has been recently theorised on the basis of the co-expression of DCC and ACE-2, the gene encoding Angiotensin I Converting Enzyme 2, the main receptor to SARS-CoV2 [17]. An interactome analysis of SARS-CoV-2 and human proteins uncovered the COMT inhibitor entacapone among the 69 existing FDA-approved drugs with a potential impact on viral biology [18]. Finally, amantadine – approved by the FDA in 1968 as a prophylactic agent for influenza and nowadays mainly used for PD – has been hypothesized to disrupt the lysosomal machinery needed for SARS-CoV-2 replication [19].

Although limited by an underpowered study (particularly for subgroup comparisons), in this multi-centre cohort of PD patients we did not find any clear effect of these drugs but certainly more studies on much larger cohorts of patients are needed. The reduced use of dopamine agonists in patients with worse outcome likely mirrors the attitude of simplifying therapy in elderly/frail PD patients. This is also supported by the high LEDD (mainly coming from l-dopa) observed in these patients. It is however well known that motor function tends to decompensate with acute stress and particularly with fever, both key symptoms of COVID-19 [20,21]. Under these circumstances, PD patients are at risk of developing severe generalized akinesia or akinetic crises, and dopaminergic medication may require a rapid increase. The possible effect of undertreatment on PD-related respiratory function cannot be entirely ruled out in our cohort and warrants future studies. Likewise, the contribution of dysautonomia in advanced PD patients deserve future studies, as these patients often present dementia and supine hypertension.

The lack of PCR confirmation of COVID-19 diagnosis in patients with compatible symptoms and exposure to SARS Co-V2 (i.e. a family member affected) is another important limitation of our study. This study was conducted in the midst of the national lockdowns and many patients refused to be further investigated. Nevertheless, most observational studies published so far adopted a strategy similar to ours.

In conclusion, in spite of some important limitations, our study is the largest series of PD patients with COVID-19 collected so far, thus allowing a more accurate definition of their mortality and – more importantly – highlighting the risk factors that should guide the actions of the medical community engaged in the care of these patients. A better-designed study on a larger sample of PD patients with confirmed COVID-19 and thorough assessment of their clinical features is urgently needed to confirm and refine the observations of the present study.

Funding sources

None.

Author contributions

(1) Research project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; (2) Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; (3) Manuscript: A. Writing of the first draft, B. Review and Critique.

AF: 1A, 1B, 2B, 3A

AEE: 1C, 2B, 3B

CD: 1C, 3B

MC: 1C, 3B

DA: 1C, 3B

CS: 1C, 3B

AAC: 1C, 3B

GP: 1B, 1C, 3B

Declaration of competing interest

AF received honoraria from Abbvie, Abbott, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, UCB, Ipsen and research support from Abbvie, Medtronic, and Boston Scientific.

Other authors have no disclosures.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to the many colleagues that contributed to data collections: Michela Barichella, MD (UOS Clinical Nutrition, Pini-CTO, Milan, Italy), Erica Cassani, MD, and Valentina Ferri, MD, (Grigioni Foundation for Parkinson; Centro Parkinson, Pini-CTO, Milan, Italy), Anna Zecchinelli, MD (Centro Parkinson, Pini-CTO, Milan, Italy), Amelia Brigandì, MD, Vincenzo Cimino, MD, PhD, Giuseppe Di Lorenzo, MD, and Silvia Marino, MD, PhD (IRCCS Centro Neurolesi Bonino Pulejo, Messina, Italy), Alessio Di Fonzo, MD (Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Neurology Unit, Milan, Italy), Carla Arbasino, MD and Massimo Sciarretta, MD (Neurology Unit, ASST Pavia, Italy), Carlo Rossi, MD (Department of Neurosciences, Section of Neurology, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy), Maziar Emamikhah, MD and Mohammad Rohani, MD (Department of Neurology, Hazrat-e-Rasool Hospital, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran), Brigida Minafra, MD, Claudio Pacchetti, MD, Francesca Valentino, MD, PhD, and Roberta Zangaglia, MD (Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders Unit, IRCCS Mondino Foundation, Pavia, Italy), Roberto Cilia, MD (Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Movement DIsorders Unit, Milan, Italy), Alfonso Giordano, MD and Alessandro Tessitore, MD, PhD (Dept. DAMSS, University of Campania, “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Naples, Italy), Giovanni Iliceto, MD (Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Neuroscience and Sense Organs, University of Bari, Italy), Lucia Ricciardi, MD, PhD and Francesca Morgante, MD, PhD (Institute of Molecular and Clinical Sciences, St George's University of London, London, UK), Francesca Antonelli, MD, PhD and Vittorio Rispoli, MD (Neuroscience Head Neck Department, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Italy), Monica Colucci, MD (SC Neurologia, Ambulatorio Parkinson e Disturbi del Movimento, Ospedale Villa Scassi, Genova).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2020.08.012.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., Cheng Z., Yu T., Xia J., Wei Y., Wu W., Xie X., Yin W., Li H., Liu M., Xiao Y., Gao H., Guo L., Xie J., Wang G., Jiang R., Gao Z., Jin Q., Wang J., Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filatov A., Sharma P., Hindi F., Espinosa P.S. Neurological complications of coronavirus disease (COVID-19): encephalopathy. Cureus. 2020;12 doi: 10.7759/cureus.7352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antonini A., Leta V., Teo J., Chaudhuri K.R. Outcome of Parkinson's Disease patients affected by COVID-19. Mov. Disord. 2020 doi: 10.1002/mds.28104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomlinson C.L., Stowe R., Patel S., Rick C., Gray R., Clarke C.E. Systematic review of levodopa dose equivalency reporting in Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 2010;25:2649–2653. doi: 10.1002/mds.23429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schirinzi T., Cerroni R., Di Lazzaro G., Liguori C., Scalise S., Bovenzi R., Conti M., Garasto E., Mercuri N.B., Pierantozzi M., Pisani A., Stefani A. Self-reported needs of patients with Parkinson's disease during COVID-19 emergency in Italy. Neurol. Sci. 2020;41:1373–1375. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04442-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onder G., Rezza G., Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fasano A., Cereda E., Barichella M., Cassani E., Ferri V., Zecchinelli A.L., Pezzoli G. COVID-19 in Parkinson's disease patients living in Lombardy, Italy. Mov. Disord. 2020 doi: 10.1002/mds.28176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardner W., States D., Bagley N. The coronavirus and the risks to the elderly in long-term care. J. Aging Soc. Pol. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2020.1750543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peball M., Mahlknecht P., Werkmann M., Marini K., Murr F., Herzmann H., Stockner H., de Marzi R., Heim B., Djamshidian A., Willeit P., Willeit J., Kiechl S., Valent D., Krismer F., Wenning G.K., Nocker M., Mair K., Poewe W., Seppi K. Prevalence and associated factors of sarcopenia and frailty in Parkinson's disease: a cross-sectional study. Gerontology. 2019;65:216–228. doi: 10.1159/000492572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Temlett J.A., Thompson P.D. Reasons for admission to hospital for Parkinson's disease. Intern. Med. J. 2006;36:524–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2006.01123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen-Van-Tam J.S., Openshaw P.J.M., Hashim A., Gadd E.M., Lim W.S., Semple M.G., Read R.C., Taylor B.L., Brett S.J., McMenamin J., Enstone J.E., Armstrong C., Nicholson K.G. Influenza Clinical Information N (2010) Risk factors for hospitalisation and poor outcome with pandemic A/H1N1 influenza: United Kingdom first wave. Thorax. September 2009;65:645–651. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.135210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jo T., Yasunaga H., Michihata N., Sasabuchi Y., Hasegawa W., Takeshima H., Sakamoto Y., Matsui H., Fushimi K., Nagase T., Yamauchi Y. Influence of Parkinsonism on outcomes of elderly pneumonia patients. Park. Relat. Disord. 2018;54:25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2018.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salem O.B., Demeret S., Demoule A., Bolgert F., Outin H., Sharshar T., Grabli D. Characteristics and outcome of patients with Parkinson's disease admitted to intensive care unit. Mov. Disord. 2019;34:798. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monteiro L., Souza-Machado A., Valderramas S., Melo A. The effect of levodopa on pulmonary function in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Therapeut. 2012;34:1049–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fazzini E., Fleming J., Fahn S. Cerebrospinal fluid antibodies to coronavirus in patients with Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 1992;7:153–158. doi: 10.1002/mds.870070210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y.C., Bai W.Z., Hashikawa T. The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nataf S. An alteration of the dopamine synthetic pathway is possibly involved in the pathophysiology of COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon D.E., Jang G.M., Bouhaddou M., Xu J., Obernier K., O'Meara M.J., Guo J.Z., Swaney D.L., Tummino T.A., Huettenhain R., Kaake R.M., Richards A.L., Tutuncuoglu B., Foussard H., Batra J., Haas K., Modak M., Kim M., Haas P., Polacco B.J., Braberg H., Fabius J.M., Eckhardt M., Soucheray M., Bennett M.J., Cakir M., McGregor M.J., Li Q., Naing Z.Z.C., Zhou Y., Peng S., Kirby I.T., Melnyk J.E., Chorba J.S., Lou K., Dai S.A., Shen W., Shi Y., Zhang Z., Barrio-Hernandez I., Memon D., Hernandez-Armenta C., Mathy C.J.P., Perica T., Pilla K.B., Ganesan S.J., Saltzberg D.J., Ramachandran R., Liu X., Rosenthal S.B., Calviello L., Venkataramanan S., Liboy-Lugo J., Lin Y., Wankowicz S.A., Bohn M., Sharp P.P., Trenker R., Young J.M., Cavero D.A., Hiatt J., Roth T.L., Rathore U., Subramanian A., Noack J., Hubert M., Roesch F., Vallet T., Meyer B., White K.M., Miorin L., Rosenberg O.S., Verba K.A., Agard D., Ott M., Emerman M., Ruggero D., García-Sastre A., Jura N., von Zastrow M., Taunton J., Ashworth A., Schwartz O., Vignuzzi M., d'Enfert C., Mukherjee S., Jacobson M., Malik H.S., Fujimori D.G., Ideker T., Craik C.S., Floor S., Fraser J.S., Gross J., Sali A., Kortemme T., Beltrao P., Shokat K., Shoichet B.K., Krogan N.J. A SARS-CoV-2-human protein-protein interaction map reveals drug targets and potential drug-repurposing. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2286-9. 2020.2003.2022.002386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smieszek S.P., Przychodzen B.P., Polymeropoulos M.H. Amantadine disrupts lysosomal gene expression; potential therapy for COVID19. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106004. 2020.2004.2005026187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helmich R.C., Bloem B.R. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Parkinson's disease: hidden sorrows and emerging opportunities. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10:351–354. doi: 10.3233/JPD-202038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fasano A., Antonini A., Katzenschlager R., Krack P., Odin P., Evans A.H., Foltynie T., Volkmann J., Merello M. Management of advanced therapies in Parkinson's disease patients in times of humanitarian crisis: the COVID-19 experience. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2020;7:361–372. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.12965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.