Abstract

This cohort study surveyed practicing physicians in the US about their use of thyroid ultrasonography to examine the rate at which misuse occurs.

In the US, there is an ongoing national dialogue about avoiding unnecessary medical tests, with the Choosing Wisely campaign recommending against ordering thyroid ultrasonographic examinations for abnormal thyroid function test results.1,2 However, despite this national dialogue, little is known about physician-reported use of thyroid ultrasonography, a known driver of thyroid cancer incidence.3,4

Methods

Between October 2018 and August 2019, we surveyed surgeons, endocrinologists, and primary care physicians who were identified as being involved in thyroid cancer care by patients with differentiated thyroid cancer who were diagnosed between 2014 and 2015 and affiliated with Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries of Georgia and Los Angeles, California.4 This study was approved by institutional review boards of participating institutions. Survey completion was considered implied consent for participation.

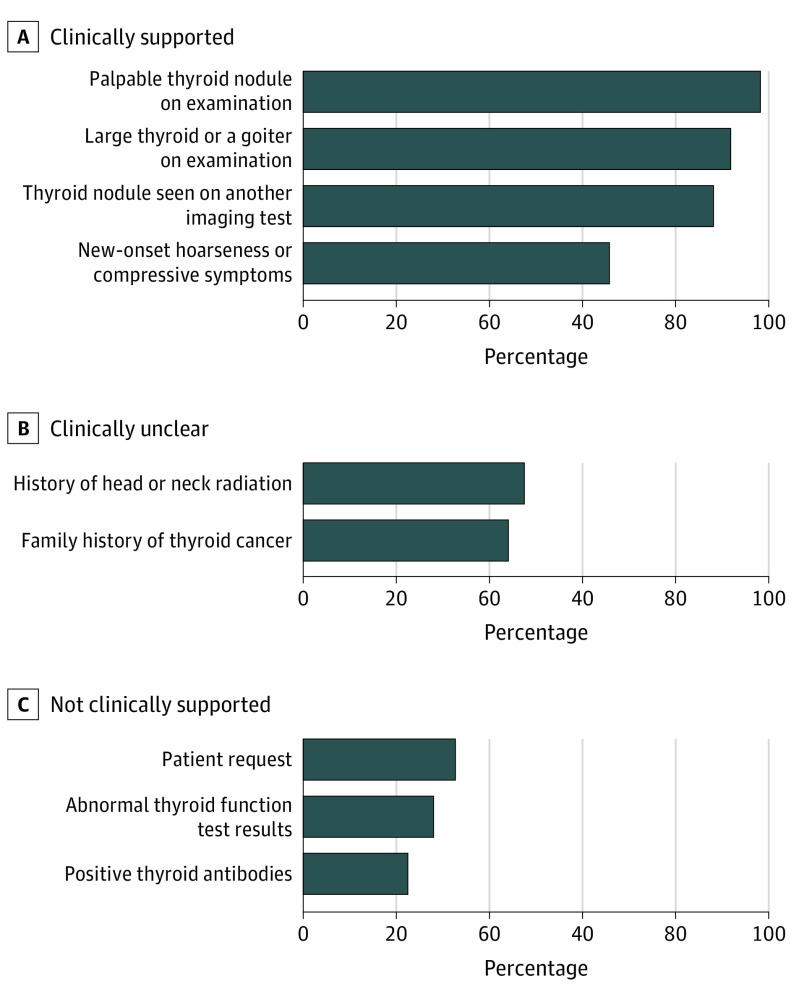

Physicians were asked to select clinical scenarios in which they would schedule a thyroid or neck ultrasonography examination (eMethods in the Supplement). For the analysis, we grouped response options into categories (clinically supported, clinically unclear, and not clinically supported), based on clinical practice guidelines and review by thyroid experts.2,5,6 Since data are conflicting or limited, the clinically unclear reasons included a history of head or neck radiation and a family history of thyroid cancer. Physicians were also asked to select the informational sources most influential in their decisions for treating patients with thyroid nodules and thyroid cancer (clinical guidelines, meetings, experts, training, colleagues, journal articles, and employer guidelines). We generated descriptive statistics for all categorical variables, and we report nonweighted frequencies and weighted percentages. Statistical analyses (performed with R version 3.5.2 [R Foundation for Statistical Computing] and Stata version 15.1 [StataCorp]) incorporated nonresponse weights. All P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 610 physicians responded, yielding a 65% response rate. The cohort consisted of primary care physicians (n = 162), endocrinologists (n = 176), otolaryngologists (n = 130), and general surgeons (n = 134). Of the respondents, 405 (66.0%) were men, 392 (67.3%) self-identified as White, 347 (59.6%) worked in private practice, and 432 (69.7%) reported that they had read the 2015 American Thyroid Association (ATA) management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer and/or the 2017 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology–Thyroid Carcinoma. Two hundred eighty-eight physicians (46.9%) reported that they had read the 2015 ATA guidelines alone, 33 (5.3%) had read the 2017 NCCN guidelines alone, and 111 (17.6%) had read both the ATA and NCCN guidelines. These physician respondents had treated 74% of the previously surveyed 2014-2015 SEER patient cohort.4

Most of the physicians reported use of ultrasonography for clinically supported reasons: palpable nodules (599 [98.2%]), large goiter (560 [91.8%]), nodule seen on another imaging test (538 [88.1%]), and new-onset hoarseness or compressive symptoms (398 [65.8%]). However, a substantial number endorsed use for clinically unsupported reasons: patient request (202 [32.7%]), abnormal thyroid function test results (169 [28.0%]), and positive thyroid antibody test result (136 [22.5%]) (Figure 1). Three physicians (0.5%) endorsed use of ultrasonography for fatigue, and no physician endorsed use for routine well-patient visits.

Figure 1. Physician-Reported Use of Thyroid Ultrasonography for Clinically Supported, Clinically Unclear, and Not Clinically Supported Reasons.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis identified factors associated with thyroid ultrasonography misuse (Figure 2). Endocrinologists (odds ratio [OR], 2.46 [95% CI, 1.22-4.97], otolaryngologists (OR, 2.87 [95% CI, 1.49-5.54]), and general surgeons (OR, 2.20 [95% CI, 1.19-4.06]) were more likely to schedule ultrasonography examinations in response to a patient request compared with primary care physicians. Physicians in private practice were more likely to schedule ultrasonography examinations for abnormal thyroid function test results (OR, 2.45 [95% CI, 1.28-4.69]) and positive thyroid antibody test results (OR, 2.61 [95% CI, 1.28-5.32]) compared with those in academic medical centers. Physicians who managed 10 or fewer patients with thyroid nodules per year, compared with more than 50 such patients, were less likely to schedule ultrasonography examinations for positive thyroid antibody test results (OR, 0.41 [95% CI, 0.18-0.93]).

Figure 2. Multivariable-Adjusted Odds Ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs of Characteristics Associated With Scheduling Thyroid Ultrasonography Examinations for Patient Request, Abnormal Thyroid Function Test Results, and Positive Thyroid Antibody Test Results.

Reference categories: primary care (medical specialty), Georgia (study site), academic medical center (practice setting), 1 to 9 years in practice, more than 50 patients with thyroid nodules managed in the past 12 months, and American Thyroid Association and/or National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical guidelines read. HMO indicates health maintenance organization.

Most surveyed physicians (428 [69.3%]) reported recently published clinical guidelines as most influential in their decisions for treating patients with thyroid nodules and thyroid cancer.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first survey study to evaluate use of thyroid ultrasonography by a diverse cohort of physicians involved in the care of a population-based cohort of patients with thyroid cancer. A substantial number of physicians endorsed use of ultrasonography for reasons not supported by clinical guidelines and in conflict with the Choosing Wisely recommendations.2,5,6

Our study has limitations in that direct links between physician-reported practice patterns and unnecessary thyroid cancer diagnoses were not possible, and physicians were not asked if they personally performed thyroid ultrasonography examinations or specific details about patients’ ultrasonography requests. Despite limitations, this study highlights the need for focused physician education on clinically supported and unsupported indications for use of thyroid ultrasonography, with potential roles for future clinical practice guidelines, patient decision-making aids, and clinical decision-making support tools.

eMethods. Key Survey Item.

References

- 1.Smith-Bindman R, Kwan ML, Marlow EC, et al. Trends in use of medical imaging in US health care systems and in Ontario, Canada, 2000-2016. JAMA. 2019;322(9):843-856. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.11456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choosing Wisely Endocrine Society: five things physicians and patients should question. Published October 16, 2013. Updated July 13, 2017. Accessed February 20, 2017. https://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/endocrine-society/

- 3.Haymart MR, Banerjee M, Reyes-Gastelum D, Caoili E, Norton EC. Thyroid ultrasound and the increase in diagnosis of low-risk thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(3):785-792. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-01933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esfandiari NH, Hughes DT, Reyes-Gastelum D, Ward KC, Hamilton AS, Haymart MR. Factors associated with diagnosis and treatment of thyroid microcarcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(12):6060-6068. doi: 10.1210/jc.2019-01219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma, version 1.2017. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx#site. Accessed April 1, 2017.

- 6.Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26(1):1-133. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Key Survey Item.