Abstract

Background

Given the exceptional diversity of orchids (26 000+ species), improving strategies for the conservation of orchids will benefit a vast number of taxa. Furthermore, with rapidly increasing numbers of endangered orchids and low success rates in orchid conservation translocation programmes worldwide, it is evident that our progress in understanding the biology of orchids is not yet translating into widespread effective conservation.

Scope

We highlight unusual aspects of the reproductive biology of orchids that can have important consequences for conservation programmes, such as specialization of pollination systems, low fruit set but high seed production, and the potential for long-distance seed dispersal. Further, we discuss the importance of their reliance on mycorrhizal fungi for germination, including quantifying the incidence of specialized versus generalized mycorrhizal associations in orchids. In light of leading conservation theory and the biology of orchids, we provide recommendations for improving population management and translocation programmes.

Conclusions

Major gains in orchid conservation can be achieved by incorporating knowledge of ecological interactions, for both generalist and specialist species. For example, habitat management can be tailored to maintain pollinator populations and conservation translocation sites selected based on confirmed availability of pollinators. Similarly, use of efficacious mycorrhizal fungi in propagation will increase the value of ex situ collections and likely increase the success of conservation translocations. Given the low genetic differentiation between populations of many orchids, experimental genetic mixing is an option to increase fitness of small populations, although caution is needed where cytotypes or floral ecotypes are present. Combining demographic data and field experiments will provide knowledge to enhance management and translocation success. Finally, high per-fruit fecundity means that orchids offer powerful but overlooked opportunities to propagate plants for experiments aimed at improving conservation outcomes. Given the predictions of ongoing environmental change, experimental approaches also offer effective ways to build more resilient populations.

Keywords: Orchid, conservation, genetics, mycorrhiza, pollination, conservation translocations, reintroduction, restoration, demography

INTRODUCTION

The Orchidaceae is one of the most species-rich of all angiosperm families, with in excess of 26 000 named species (WCSPF, 2019). The distribution of the family spans all continents except Antarctica, and includes most major island groups (Dressler, 1981). Orchids reach their highest diversity in the epiphytic communities of the tropics, particularly at middle elevations, where they make up a large component of plant species richness (Gentry and Dodson, 1987; Ibisch et al., 1996; Vasquez et al., 2003). While ~70 % of orchid species are epiphytic, there are also diverse terrestrial communities in some tropical and temperate regions (Dressler, 1981).

In some countries, such as Ecuador, China and Australia, orchids feature prominently among lists of threatened plant species (e.g. León-Yánez et al., 2011; Qin et al., 2017; Australian Government, 2019). However, given that in biodiverse tropical countries many orchid species are poorly known, the numbers of endangered orchid species are likely to continue to grow on both national and international lists (Joppa et al., 2011a, b). Like many other plant groups, orchids face unprecedented levels of threat from habitat destruction and fragmentation, overcollecting, climate change and a range of other human-induced issues (Diamond, 1989; Dixon et al., 2003; Thomas et al., 2004; Swarts and Dixon, 2009; Reiter et al., 2016; Hinsley et al., 2018). However, some unusual aspects of orchid biology suggest that many species may present unique conservation challenges. Further, many species of terrestrial and epiphytic orchids naturally occur in small isolated populations, in part as a result of specialized habitat preferences (Dressler, 1981; Tremblay et al., 2005).

Aims and approach

Despite considerable advances in our knowledge of orchid biology (see reviews of Swarts and Dixon, 2009; McCormick and Jacquemyn, 2014; Rasmussen et al., 2015; Bohman et al., 2016; Johnson and Schiestl, 2016; Fay, 2018; McCormick et al., 2018) and some important conservation success stories (e.g. Fig. 1; Willems, 2001; Schrautzer et al., 2011; Reiter et al., 2018a), there are clear signs in the literature that orchid conservation is not being as effective as required to avert the extinction of a large number of species. Many threatened orchid species have already undergone large population declines (Cribb et al., 2003) and, based on resources such as the IUCN red list (IUCN, 2020) and government recovery plans (e.g. Australian Government, 2019), most species that are listed as endangered experience threats beyond the destruction of habitat (Wraith and Pickering, 2019). Further, in a global review of 74 published conservation translocations, an action commonly applied for threatened orchids, Reiter et al. (2016) found that only 25 % of studies observed any fruit set and just 2.8 % of studies observed recruitment. Given this lack of success, it is clear that there is an urgent need for a critical appraisal of the current approaches to orchid conservation.

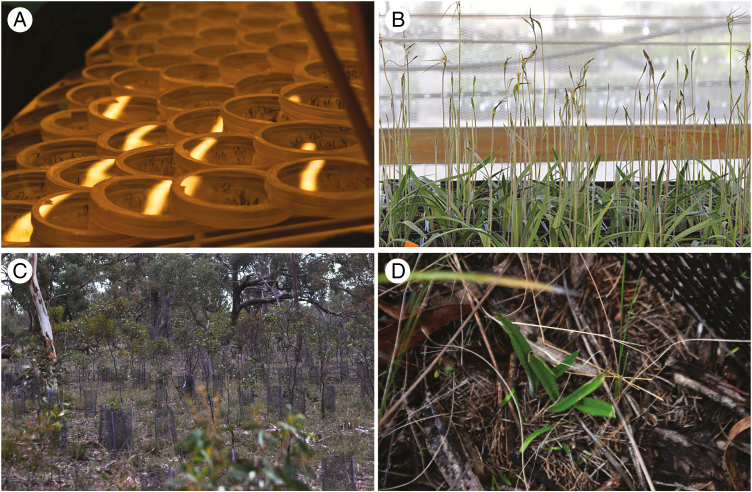

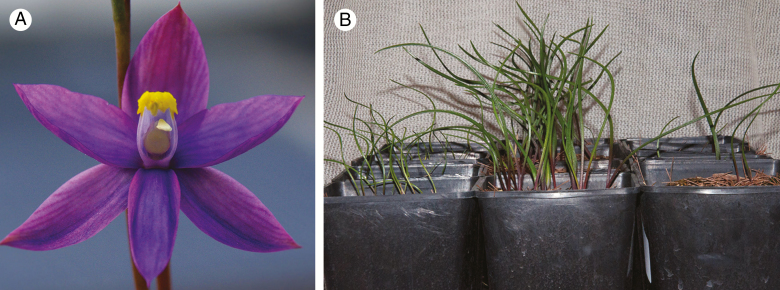

Fig. 1.

Steps in the currently successful conservation translocation programme of Caladenia colorata, a threatened species from south-eastern Australia. (A) Petri dishes of seedlings germinated symbiotically using a specific species of Serendipita mycorrhizal fungi. (B) Plants grown through to adulthood in glasshouse conditions. (C) Translocation to wild sites that were selected based on a detailed assessment of the vegetation community and confirmation of the presence of the primary pollinator species (Reiter et al., 2018a). (D) Wild recruits around the adult orchids that were originally planted. A total of 883 plants were introduced between 2013 and 2017. As of September 2018 there were 593 (67 %) of these plants surviving plus an additional 580 recruits, an increase of 65 % in the population beyond those initially planted and 97.8 % beyond those that survived translocation. Monitoring will now be conducted to either confirm long-term viability of established populations or alert managers to life cycle stages that are limiting the maintenance of positive population growth. Photographs by Noushka Reiter.

Practical techniques for orchid conservation such as propagation, seed storage and genetic analysis have been comprehensively reviewed elsewhere (Swarts and Dixon, 2017). Therefore, here we consider how biological knowledge of a species, and its interactions, might be used to improve conservation outcomes. For example, no matter how good the propagation technique or the ex situ collection, failure to consider the availability of effective pollinators in a conservation translocation programme could mean that such efforts are merely a ‘gardening exercise’ with little prospect of achieving a self-sustaining population. Our focus in this review is on topics that are likely to be more prevalent in orchids than other plants, and on conservation issues that are likely to be broadly applicable across geographical regions and taxonomic groups within the Orchidaceae. Nonetheless, many of the issues we raise also have some general applicability beyond orchids. We do not cover the adverse effects of the trade in wild collected orchids (e.g. removal of wild orchids for horticulture, food or medicine), as this has recently been comprehensively reviewed by Hinsley et al. (2018).

To provide a framework for the review, we use the orchid life cycle as an organizing principle (Fig. 2; Table 1). Firstly, we highlight four unusual aspects of the biology of orchids: (1) a high incidence of specialized pollination systems; (2) pollinator-limited fruit set, but with high fecundity; (3) dust-like seed and high dispersal; and (4) dependence on mycorrhiza for germination and growth through the protocorm stage. In this section we also provide a comprehensive review of the literature to quantify the incidence of specialized mycorrhizal associations in orchids. We then establish whether these unusual aspects of orchid biology have been adequately addressed in studies aiming to improve conservation outcomes. Finally, we identify current innovations and future directions that if implemented could deliver large-scale, effective orchid conservation programmes.

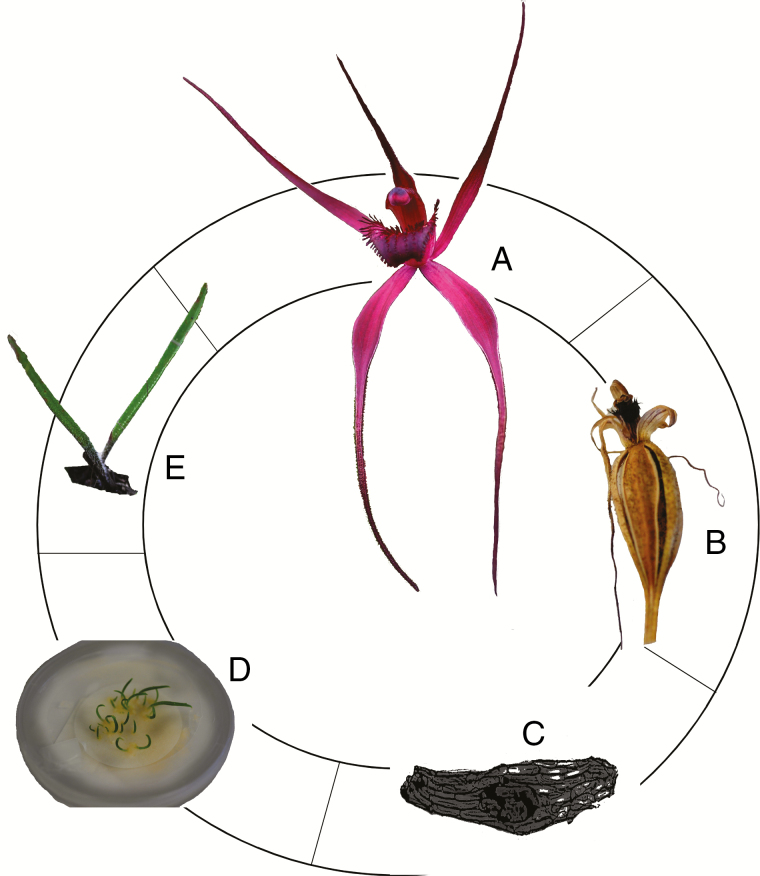

Fig. 2.

The life cycle of orchids. (A) Flowering. (B) Fruit formation. (C) Seed dispersal. (D) Germination through association with mycorrhizal fungi. (E) Recruitment to adulthood. Features associated with these life cycle stages are elaborated upon in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of life cycle stages of orchids, their unusual features and their consequences for conservation. Life cycle stages are illustrated in Fig. 2

| Life cycle stage | Features | Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Pollination | Often exhibit a specialized strategy | Potentially limited by pollinator availability |

| Often exhibit a deceptive strategy | Many species have low fruit set | |

| Chemicals can be crucial for pollinator attraction | Potential for cryptic taxa using different semiochemicals | |

| Fruit formation | High seed output from a single capsule | High seed output for propagation and experiments; low genetic diversity of seed crop sourced from a single fruit |

| Small number of seed parents per capsule | Low genetic diversity of seed crop sourced from a single fruit | |

| Seed dispersal | Tiny, wind-dispersed seed | Capable of long-distance dispersal; low genetic differentiation among populations |

| Germination | Association with mycorrhizal fungi for germination | Not all fungi are equally effective; germination limited by fungal abundance and distribution; low per-seed germination rates |

| Tiny seed, usually lacking an endosperm | Low per-seed germination and survival rates in the wild | |

| Recruitment to adulthood | Terrestrial orchids require mycorrhizal association through to adulthood | Not all fungi are equally effective; persistence to adulthood limited by fungal abundance and distribution |

| Some terrestrial orchids exhibit dormancy | Difficult to assess population numbers and response to management without long-term population monitoring |

THE DEFINING FEATURES OF ORCHIDS

Despite the vast array of shapes, colours and odours of orchid flowers (Pridgeon et al., 1999), a common set of floral traits characterize virtually all orchids. For example, all orchid flowers are zygomorphic with the stamen(s) on one side of the flower rather than in a symmetrical arrangement of separate anthers. Further, the stamen and pistil are at least partly united, with most species bearing a single stamen that is completely united with this pistil into one structure, called the column (Dressler, 1981). In the majority of orchids the petal opposite the column is modified into a lip known as the labellum (though see Dafni and Calder, 1987). Due to the resupinate development seen in most species, where the inferior ovary twists 180° while the flower is in bud, this petal is positioned on the underside of the column (though see Peakall, 1989). The pollen grains are numerous and typically bound in large masses known as pollinia (Johnson and Edwards, 2000). In virtually all species of orchid, the numerous seeds are tiny (mostly 0.05–6 mm) and lack an endosperm (Arditti and Ghani, 2000).

Orchids occupy a broad range of habitats, and their growth habits can be terrestrial, epiphytic, lithophytic or even predominantly underground. Therefore, it is no surprise that their growth forms show considerable variation across the family (Dressler, 1981). Nonetheless, one feature that is prevalent is the velamen, comprising one or more layers of spongy cells on the outside of the roots (Dressler, 1981). This structure occurs in virtually all epiphytic orchids, as well as many terrestrial genera (Pridgeon et al., 1999; Zotz et al., 2017). The presence of this spongy, water-absorbing layer may have acted as a pre-adaptation to the evolution of epiphytism (Dressler, 1981; Benzing, 1990; Gravendeel et al., 2004), which is so prevalent in the family.

UNUSUAL FEATURES OF ORCHID BIOLOGY

High incidence of specialized pollination systems

The Orchidaceae exhibits the full continuum of pollination systems from generalized to highly specialized (e.g. Joffard et al., 2019), as well as various forms of autogamy (Dressler, 1981). In orchids, highly generalized pollination strategies involving multiple pollinator functional groups appear to be unusual (e.g. flies, bees and butterflies as effective pollinators of a single species; Johnson and Hobbhahn, 2010). Alternatively, many orchid species exhibit specialization at the level of pollinator functional groups (Argue, 2012). For example, several species of noctuid moths, but not other insects, pollinate the North American orchid Tipularia discolor (Whigham and McWethy, 1980; Argue, 2012). Further, as we show below, orchids are unusual in that many species exhibit specialization on only one or few pollinator species (i.e. exhibiting ecological specialization as defined by Ollerton et al., 2007; Armbruster, 2017). While highly specialized pollination strategies occur in many plant families, the orchids may have been predisposed to the evolution of specialized pollination strategies due to several floral features: the packing of pollen in pollinia means that there can be efficient pollen transfer even at low visitation rates (Johnson and Edwards, 2000); the positioning of pollinaria in close proximity to the labellum means that only pollinators of a particular size may lead to pollen transfer (Li et al., 2008; Schiestl and Schlüter, 2009; Reiter et al., 2018a); and the labellum of their zygomorphic flowers can be extensively modified for positioning of the pollinator (e.g. Phillips et al., 2014b; De Jager and Peakall, 2016) or for utilizing different methods of attraction (Johnson and Schiestl, 2016).

Several regional and global summaries of the number of known pollinator species in orchid pollination systems are available (summarized in Table 2). While the number of pollinator observations and study sites varies between studies, for several regional and global estimates the number of pollinator species most commonly recorded for any given orchid species was one (i.e. the modal value was one). As such, while the average number of pollinator species varies among pollination strategies (e.g. more in nectar-rewarding than sexually deceptive systems; Joffard et al., 2019) and geographical regions (e.g. more generalist species in Europe than South Africa; Johnson and Steiner, 2003), the literature currently shows that highly specialized pollination predominates within the Orchidaceae. Thus, in many orchid species reproductive success in a given population depends on just one or a few pollinator species.

Table 2.

Estimates of the frequency of specialized pollination systems in orchid floras at the global, continental or subcontinental scale based on pollinator records from published studies

| Orchid flora | Mode | Mean/median | N | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global | 1 | – | 479 | Tremblay (1992) |

| Global | 1 | 3.97 ± 0.97 (mean ± s.e.) | 424 | Gravendeel et al. (2004); data from Van der Cingel (2001) |

| Global* | – | 2.30 ± 1.87 (mean ± s.d.) | 186 | Schiestl and Schlüter (2009) |

| Southern Africa | 1 | 1 (median) | 73 | Johnson and Steiner (2003) |

| North America and Europe | 3 | 5 (median) | 41 | Johnson and Steiner (2003) |

| Europe | 1 | 7.44 (mean) | 153 | Joffard et al. (2019); data before 2011 from Claessens and Kleynen (2011) |

| Global sexually deceptive** | 1 | 1.29 ± 0.87 (mean ± s.d.) | 288 | Gaskett (2011) |

| Western Australian sexually deceptive Caladenia | 1 | 1.05 (mean) | 45 | Phillips et al. (2017) |

Mode and mean/median refer to the number of pollinator species per orchid species.

N refers to the number of orchid species included in a review.

*Only included studies where the pollination of more than one orchid species had been presented.

**Summary statistics were calculated in the present study using data from Gaskett (2011). For the data from Gaskett (2011) we only included orchid species where sexual deception was confirmed, and where pollinator(s) were identified below family level.

Associated with their high incidence of specialized pollination systems, the orchids contain perhaps the most bewildering array of pollination strategies of any plant family (Fig. 3). In many orchids there is strong evidence of floral traits as adaptations to attract specific pollinator species or pollinator groups (see examples in Johnson and Schiestl, 2016). Even among orchid species that provide nectar reward (perhaps the most common pollination strategy outside the orchids) there is evidence for specific adaptations to pollen vectors drawn from a wide range of taxonomic groups, including birds, moths, long-tongued flies, solitary bees and wasps (Nilsson et al., 1987; Van der Cingel, 1995; Johnson et al., 1998; van der Niet et al., 2015; Reiter et al., 2018a). One unusual rewarding pollination strategy, found in numerous neotropical orchid species (~600 species), is the provision of fragrance to male euglossine bees that incorporate the compounds into a bouquet of chemicals that they use in courtship (Ackerman, 1983; Ramírez et al., 2011).

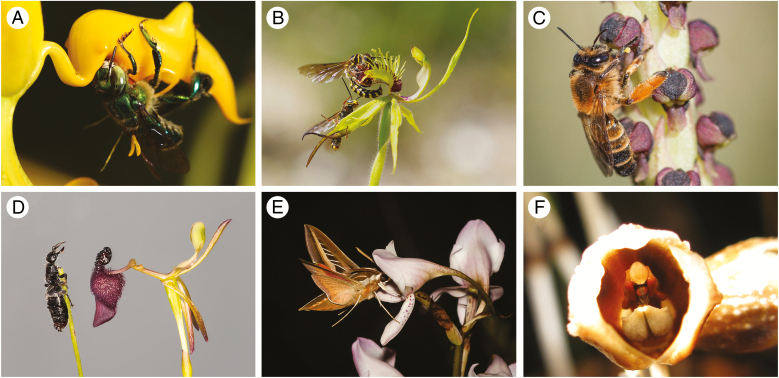

Fig. 3.

Examples of pollination strategies in the orchids. (A) Pollination by fragrance-collecting euglossine bees: a species of Euglossa bee pollinating a species of Gongora. The bees are attracted by fragrances that they collect and use in courtship bouquets (Ramirez et al., 2011). Photograph: Santiago Ramirez. (B) Pollination by sexual deception: Caladenia crebra is pollinated by sexual deception of the thynnine wasp Campylothynnus flavopictus (Phillips et al., 2017). Long-distance attraction is by mimicry of a blend of (methylthio)-phenol sex pheromones (Bohman et al., 2017). Photograph: Rod Peakall. (C) Pollination by oil-collecting bees: Corycium nigrescens is pollinated by the melittid bee Rediviva brunnea, which collects oil to provision its brood. Photograph: Michael Whitehead. (D) Pollination by sexual deception: Drakaea glyptodon is pollinated by sexual deception of the thynnine wasp Zaspilothynnus trilobatus (Peakall, 1990). Long-distance attraction is by mimicry of a blend of pyrazine sex pheromones (Bohman et al., 2014). Here the flower is shown along side the female wasp. Photograph: Rod Peakall. (E) Pollination by nectar foraging hawkmoths: Disa crassicornis is pollinated by hawkmoths that feed on nectar produced at the end of the long nectar spur. Photograph: Michael Whitehead. (F) Pollination by brood site mimicry: Gastrodia similis mimics forest fruits using chemical cues, which attract pollinating Scaptodrosophila flies searching for an oviposition site (Martos et al., 2015). Photograph: David Caron.

Another unusual feature of the orchids is the very high frequency of deceptive pollination strategies (Jersáková et al., 2006; Johnson and Schiestl, 2016). While precise estimates are lacking for most regions (Shrestha et al., 2020), it is commonly cited that approximately one-third of all orchids employ such strategies (see references in Jersáková et al., 2006). Many deceptive strategies are specialized through the use of floral signals that are attractive to particular pollinators (Johnson and Schiestl, 2016). For example, deceptive pollination systems involving Batesian mimicry of food plants (e.g. Nilsson, 1983; Peter and Johnson, 2008; Jersáková et al., 2012), sexual deception by the mimicry of female insects (most recently reviewed by Bohman et al., 2016) and mimicry of brood sites (Martos et al., 2015) all typically involve the attraction of one or few pollinator species using chemical or visual signals.

Pollinator-limited fruit set, but high fecundity

While reproductive success has only been assessed for a very small fraction of the Orchidaceae, for non-autogamous species fruit set within a flowering season appears to be primarily limited by the number of flowers receiving pollen, a trend that holds for both terrestrial and epiphytic species (Tremblay et al., 2005). Indeed, pollen limitation in orchids is often substantial, with 2- to 20-fold increases in fruit set commonly being reported following experimental hand pollination (reviewed in Tremblay et al., 2005). While deceptive orchids have on average much lower fruit set than rewarding species [Tremblay et al., 2005; mean for deceptive species = 20.7 % (N = 130); mean for rewarding species = 37.1 % (N = 84)] and fruit set is on average lower in tropical species (Tremblay et al., 2005), pronounced pollen limitation within a flowering season appears to hold true regardless of geography or the pollination strategy. Experimental investigations extending beyond a single flowering season have shown that many orchids exhibit a subsequent cost of fruit formation, with individuals often showing less vigorous growth or reduced investment in flowering the following season (Snow and Whigham, 1989; Ackerman and Montalvo, 1990; Primack et al., 1994; Sletvold and Agren, 2015). However, in these experiments the number of artificially pollinated flowers is often well above natural pollination levels, thus pollen limitation, not resource limitation, seems likely to dominate across the lifetime of non-autogamous orchids (Calvo and Horwitz, 1990).

By virtue of the packaging of pollen as pollinia in orchids (though see Dressler, 1981 for some exceptions), when a pollination event does occur vast numbers of pollen grains are deposited on the stigma. The estimated number of pollen grains per pollinium varies from ~5000 to ~4 000 000 depending on the species (Nazarov and Gerlach, 1997; Johnson and Edwards, 2000). Therefore, even when just a portion of the pollinium is deposited on a flower, subsequent fertilization can yield thousands of seeds per capsule (Darwin, 1877; Arditti and Ghani, 2000). Indeed, while varying widely among orchid genera, reported maximum estimates range from ~100 to ~6 000 000 seeds per capsule (Arditti and Ghani, 2000; Meléndez-Ackerman and Ackerman, 2001), with most species having well over 1000 seeds per capsule. Therefore, even when a low number of fruits are produced in any given season, seed output by orchids can be exceptionally high.

A corollary of the en masse pollination of orchids is that the resulting seed is likely to be fathered by only a small number of pollen donors. While pollen-labelling studies have shown that there is some level of pollen carryover among flowers of different plants, confirming the potential for multiple fathers per fruit (e.g. Peakall, 1989; Peakall and Beattie, 1996; Johnson and Nilsson, 1999), such studies in multiflowered species have also revealed moderate rates of geitonogamy (reviewed in Kropf and Renner, 2008). To date, the only two studies to conduct paternity analysis of orchid seed showed that there was either one father per fruit (Trapnell and Hamrick, 2004), or an average of 1.35 fathers per fruit (Whitehead et al., 2015). As such, many orchids may exhibit the unusual situation of high seed output, but with a low genetic diversity among the progeny, particularly among those species with solid rather than sectile or mealy pollinia.

Dust-like seed and high dispersal

While the dust-like seeds of orchids appear well adapted for wind dispersal (Beer, 1863), much of the seed falls close to the parent plant (e.g. Murren and Ellison, 1998; Nathan et al., 2000; Jersakova and Malinova, 2007; Brzosko et al., 2017). Nonetheless, observations of orchid colonization of distant areas of suitable habitat and remote oceanic islands (Dressler, 1981; Arditti and Ghani, 2000; Partomihardjo, 2003) demonstrate that such tiny seeds do have an exceptional capability for long-distance dispersal, with a small proportion of seeds presumably moving a very long way. Given the colonizing potential of many species, orchids are expected to exhibit comparatively high levels of seed-mediated gene flow with low levels of population genetic differentiation as a consequence (Phillips et al., 2012). Indeed, allozyme and microsatellite data for terrestrial orchids support this scenario, with most species exhibiting low genetic differentiation, even across relatively large geographical distances (see review by Phillips et al., 2012). While rare species, which presumably have more geographically isolated populations, have on average greater genetic variation between populations (Phillips et al., 2012), this is still typically less than that seen in most other plant families (Hamrick and Godt, 1996; Phillips et al., 2012; but see Arduino et al., 1996; Wong and Sun, 1999; Wallace 2002; Chung and Chung, 2007 for species with high differentiation).

Although most orchid population genetic studies have been based on terrestrial species, the few studies of epiphytic and lithophytic taxa show a similar pattern of low levels of differentiation across spatial scales of tens to hundreds of kilometres (Ackerman and Ward, 1999; Borba et al., 2001; Trapnell and Hamrick, 2004; Avila-Diaz and Oyama, 2007; Ribeiro et al., 2008; Kisel et al., 2012). From a conservation perspective, it remains to be seen whether, following the decline of many orchid populations via extensive vegetation clearing or inappropriate habitat management, there are still sufficient orchids reproducing to maintain both regular gene flow among populations and long-range colonization.

Dependence on mycorrhiza for germination and protocorm growth

Given that orchid seeds typically lack an endosperm (Arditti and Ghani, 2000; Yeung, 2017), they are reliant on mycorrhizal fungi to provide the essential nutrition for germination and protocorm growth through to the green leaf stage (Smith and Read, 2008; Rasmussen and Rasmussen, 2009). Often this fungal association is maintained into adulthood, although the reliance of the adult plant on fungi is likely to vary between life forms (e.g. epiphytic versus terrestrial; Hadley and Williamson, 1972; Bayman et al., 2002; Rasmussen and Rasmussen, 2009). In some adult photosynthetic terrestrial orchids, the plant exports sugars to the fungus (Cameron et al., 2006), while the plant receives phosphorus across intact membranes, and fungal phosphorus, nitrogen and carbon from the lysis of the hyphae that form pelotons (Cameron et al., 2006, 2008; Bougoure et al., 2013; Dearnaley and Cameron, 2017; Fochi et al., 2017). However, it is increasingly being recognized that some photosynthetic orchids are partial mycoheterotrophs, which in adulthood retain an ability to acquire some carbon from fungi (Gebauer et al., 2016). Interestingly, the retention of a fully mycoheterotrophic state, where the plant remains completely reliant on the fungus for carbon in adulthood, has also evolved sporadically across the Orchidaceae (Merckx, 2013).

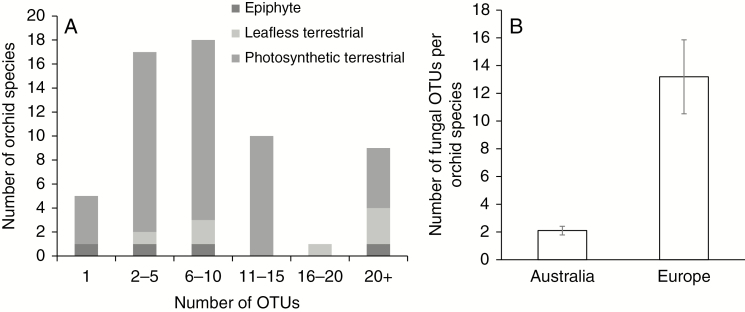

Many of the orchid species studied thus far, including epiphytes and both photosynthetic and mycoheterotrophic terrestrial orchids, associate with a range of fungal species (e.g. Shefferson et al., 2005b; Jacquemyn et al., 2010; De Long et al., 2013; Waud et al., 2017) (Fig. 4; see Supplementary Data Table S1 for full list of studies and methodology). However, a number of orchid species have highly specialized relationships, often using just one or a few fungal species (e.g. Shefferson et al., 2005b; Otero et al., 2007; Bougoure et al., 2009; Swarts et al., 2010; Phillips et al., 2011; Linde et al., 2014; McCormick and Jacquemyn, 2014; Reiter et al., 2020). Many of the more extreme reported cases of specialization are from the terrestrial orchids of Australia. For example, based on our literature review of studies that have quantified mycorrhizal specificity in detail via DNA sequencing of the ITS locus, terrestrial Australian species associate with an average of 2.1 ± 0.3 (s.e.) (N = 10) fungal operational taxonomic units per orchid species, compared with an average of 13.2 ± 2.7 (N = 32) for terrestrial European orchids (Fig. 4; Supplementary Data Table S1). These findings highlight the potential for regional and/or taxonomic variation in the patterns of specificity among orchid–mycorrhizal associations. However, at present a lack of data on the relative effectiveness of the fungal associates detected in orchids makes it challenging to draw generalizations about variation in mycorrhizal specialization among clades of orchids and geographical regions.

Fig. 4.

Summary of the number of fungal operational taxonomic units (OTUs) that orchid species associate with based on the literature summarized in Supplementary Data Table S1. Studies were included if they presented data on the ITS sequence locus, 15 or more orchid individuals were sampled, and orchids were sampled from two or more sites. For full methodology see Supplementary Data Table S1. (A) Number of orchid species that exhibit varying levels of specialization in mycorrhizal association, subdivided into species that are photosynthetic terrestrials, leafless terrestrials and epiphytes. (B) Mean number (± s.e.) of fungal OTUs associated with photosynthetic terrestrial orchids in Europe compared with Australia.

Despite epiphytes representing the majority of all orchid species, comparatively little is known about their mycorrhizal ecology (Rasmussen et al., 2015). In fact, the sporadic appearance and low abundance of pelotons in most adult epiphytic orchids has led some researchers to question their importance for plant nutrition, at least for adult plants (Hadley and Williamson, 1972; Lesica and Antibus, 1990; Bayman et al., 2002). For example, in Lepanthes rupestrisBayman et al. (2002) found only a solitary intact peloton in 300 root sections. Further, the Rhizoctonia-like fungi isolated from the roots of Lepanthes were also frequently detected in the leaves of the plant, raising the possibility that they may be non-functional endophytes (Bayman et al., 1997). Nonetheless, while evidence for the importance of mycorrhiza in adults is equivocal in epiphytic orchids, mycorrhizal fungi are present in protocorms (Zettler et al., 2011; Khamchatra et al., 2016; Izuddin et al., 2019) and fungi isolated from seedlings and/or adult plants can lead to increased germination and seedling growth in vitro compared with asymbiotic controls (Otero et al., 2005, 2007; Hoang et al., 2017; Meng et al., 2019). Furthermore, direct DNA sequencing of fungi from the roots of epiphytic orchids tends to recover a number of species of fungus from groups known to form mycorrhizal relationships with orchids more generally (e.g. Martos et al., 2012; Herrera et al., 2019; Rammitsu et al., 2019), hinting at their potential importance. Nonetheless, due to the lack of germination experiments testing for function (though see Meng et al., 2019), just how many species of fungal endophytes actually form mycorrhizal associations remains largely unknown in epiphytic orchids.

UNUSUAL ORCHID LIFE CYLE FEATURES AND CONSERVATION CONSIDERATIONS

Maintaining reproductive success: a key to effective conservation

Pollinator availability in specialized pollination systems. For the many orchids with specialized pollination, their reliance on just one or a few pollinator species for reproduction raises three key questions: (1) Does the geographical range of the pollinator(s) limit the distribution of the orchid? (2) Does the abundance of the pollinator(s) limit available habitat for the orchid? (3) What are the effects of anthropogenic habitat modification on specialized pollination systems? These questions apply equally when an orchid is reliant on one or few pollinator species across its entire geographical range and when, despite geographical replacement of pollinators, there is high pollinator specificity for a given orchid population. In a study investigating the potential for pollinator availability to limit the geographical range of plants, Duffy and Johnson (2017) showed that the geographical range of the pollinator was the best predictor of the environmental niche of the orchid for 11 out of 17 species of South African orchids with specialized pollination systems. At the scale of suitable habitat patches within a species’ geographical range, Phillips et al. (2014a) found that rarity of Drakaea orchids is correlated with low occupancy of suitable habitat patches by the respective pollinator species. These studies suggest that pollinator availability may be a key process controlling the spatial distribution of specialized orchid species. Further, Moeller et al. (2012) showed that this scenario is also possible in plants with more generalist pollination systems. In this case, a member of the Onagraceae had lower visitation by pollinating bees and greater pollen limitation at its range margin (Moeller et al., 2012). As such, managing landscapes to support populations of suitable pollinators could be critical for the persistence of numerous species of rare orchids, irrespective of their pollination strategy.

In some orchid species, pollinator availability could also place a major constraint on the sites suitable for conservation translocations. For example, of the 233 potentially suitable sites surveyed for population establishment of the rare Caladenia hastata, the pollinating thynnine wasp species was only detected at five sites (Reiter et al., 2017). Remarkably, surveys to confirm that suitable pollinators are present prior to conservation translocations are very rarely done (just 1 % of orchid conservation translocations outside of Australia; Reiter et al., 2016). Furthermore, the failure to consider pollinator availability is likely to have been a key factor contributing to the observation that half of the published conservation translocations that achieved flowering did not achieve any natural fruit set (Reiter et al., 2016).

Declines of pollinator populations. Pollinator declines are of growing global concern for flowering plants in general (e.g. Potts et al., 2010; Sánchez-Bayo and Wyckhus, 2019), with subsequent reductions in reproductive success and population size of non-orchid plant species already being documented (Biesmeijer et al., 2006; Anderson et al., 2011). In many regions, the key reason for the decline in the availability of pollinators has been the destruction of habitat and the fragmentation and degradation of the remaining habitat (Didham et al., 1996). To date, within the orchids few studies have explicitly tested the effects of habitat fragmentation on reproductive success and population persistence (but see Pauw, 2007; Meekers and Honnay, 2011; Parra-Tabla et al., 2011; Phillips et al., 2015b). However, the oil-producing members of the South African orchid genus Pterygodium offer one of the best-documented examples to date. In this case, orchid populations were rapidly lost from habitat fragments due to local extinction of the pollinating bee, with the least clonal species most rapidly going extinct from small habitat remnants (Pauw, 2007; Pauw and Hawkins, 2011).

The greater resilience of clonal Pterygodium species highlights the potential for orchid communities to exhibit an extinction debt. This is the situation where, due to clonality or individual longevity, extinction is yet to occur despite the population size or habitat quality already falling below the threshold for persistence (Tilman et al., 1994; Kuussaari et al., 2009). While the potential loss of pollinators from habitat remnants is clearly an issue for any species that exhibit specialized pollination at the population level, increased extinction risks could also apply to species with more generalized pollination when total pollinator declines cause orchid population growth rates to fall below 0. However, extinction debts in these more generalist cases may only become evident over a longer time scale.

In addition to the pervasive threat of habitat destruction, there are many other factors impacting pollinator availability, such as changes of habitat suitability through altered management (Goulson et al., 2008), competition with invasive pollinators (Morales et al., 2017; Vanbergen et al., 2018), shifts in phenology and local abundance through climate change (Robbirt et al., 2014), the use of pesticides (Brittain et al., 2010) and the spread of pathogens through human movement of pollinators (Graystock et al., 2013). The best strategies for mitigating pollinator declines may vary between regions, and depend on the surrounding land use. For example, in Europe sowing wildflower strips has been shown to consistently increase the local abundance and diversity of insect communities, although with a bias towards commonly occurring insect species (Haaland et al., 2011; Johansen et al., 2019). Similarly, supplementation of nest sites can increase bee pollinator populations in areas where nesting sites are limited (Steffan-Dewenter and Schiele, 2008; Westerfelt et al., 2015; Fortel et al., 2016). While it is presently unknown how effective such mitigation strategies are for rare pollinators or those with more complex life cycles (e.g. parasitoids), they highlight the potential for manipulating habitat features to increase pollinator availability.

For the large majority of orchids that are pollinated by insects, the targeted management of orchid pollinators will often be hampered by the lack of biological knowledge of the pollinator. However, for some nectar- and pollen-feeding pollinators, information on diet is more readily attainable. In these cases, it may be possible to manipulate the abundance of suitable forage plants to sustain populations of the pollinators, thereby facilitating pollination of co-occurring orchids that are either deceptive or provide a meagre reward (the ‘magnet effect’; Laverty, 1992; Johnson et al., 2003; Peter and Johnson, 2008; Menz et al., 2011). Indeed, the plant–pollinator network approach (e.g. Pauw and Stanway, 2015; Phillips et al., 2020) could possibly be extended to identify the range of co-occurring food plants that function to support a population of the orchid pollinator. However, there is some experimental evidence that plants that produce abundant nectar can outcompete orchids for visitation by pollinators (Lammi and Kuitunen, 1995), though these orchids still had higher than average fruit set for a deceptive orchid (Lammi and Kuitunen, 1995; compare with data reviewed in Tremblay et al., 2005).

Pollination ecotypes and species management. An interesting by-product of pollination strategies based on chemical attractants is that orchid populations can exhibit similar colour and morphology while being reproductively isolated by their chemical-based attraction of different pollinator species (Xu et al., 2011; Whitehead and Peakall, 2014). In sexually deceptive orchids there are several instances of ecotypic variation in the semiochemicals involved in pollinator attraction without obvious divergence in floral colour or morphology (e.g. Bower, 2006; Breitkopf et al., 2013; Peakall and Whitehead, 2014; Menz et al., 2015; Phillips et al., 2015a). Furthermore, cryptic floral ecotypes have even been found within sexually deceptive species of varying distribution size and continuity of populations (Menz et al., 2015; Phillips et al., 2015a), indicating that the presence of ecotypes is not readily predictable.

It remains to be determined if species or floral ecotypes that are morphologically cryptic are prevalent in chemical-based pollination systems outside of sexual deception, although visually recognizable floral ecotypes are known in orchids using other pollination strategies (e.g. references in Van der Niet et al., 2014). Should ecotypes be present, such populations may need independent genetic management, particularly if conducting hand pollinations to obtain seed for ex situ collections, translocation or reintroduction, as hybrids may be of lower fitness (Phillips et al., 2020). Further, different pollinators may have different habitat requirements, and the use of ecotypes in conservation translocations would need to be tailored to reflect the locally most effective pollinator species. In some cases ecotypes may prove worthy of taxonomic recognition, and knowledge of the geographical range of ecotypes should be incorporated into decisions for the protection of populations.

Orchid pollination and the planting design for conservation translocations. Larger translocated populations are more likely to be successful (Godefroid et al., 2011; Albrecht and Maschinski, 2012; Silcock et al., 2019), in part because larger populations are less susceptible to stochastic risks, Allee affects and inbreeding depression (Allee et al., 1949; Lande, 1993; Armstrong and Seddon, 2008). In orchids that secure pollination via rewards, reproductive success per plant is predicted to increase with population size due to the increased ability of the population to attract and sustain pollinators (Johnson et al., 2009; Meekers and Honnay, 2011). However, in deceptive orchid species the reverse may be true. For example, in sexually deceptive orchids the per-plant rates of reproduction may actually decline at high density or large population size, likely due to pollinators avoiding multiple visits to deceptive flowers (Peakall and Beattie, 1996; Phillips et al., 2014a). A similar pattern of higher fruit set in small patches has also been reported for food-deceptive strategies (Brundrett, 2019). Therefore, for such species, planting them in small subpopulations or at low density may be the optimal design for conservation translocations. This planting layout would also spread the risk of translocation failure between sites, and create the potential for regular gene flow between populations and thus potentially reduce the risks of inbreeding depression in small populations (Willi et al., 2006). Indeed, this may be the first step towards replicating the natural metapopulation structure that appears to characterize many orchid species (Tremblay et al., 2006; Winkler et al., 2009). While experimental tests of optimal population size are difficult to achieve in animals and many plant groups (Armstrong and Seddon, 2008), orchids are sufficiently fecund that even for many rare species an experimental approach is a realistic possibility.

Pollinator-limited fruit set, but high fecundity as an asset for conservation

The typical high per-capsule seed production in orchids means that pollinator-limited fruit set may not be a conservation issue if recruitment rates are sufficiently high to maintain a stable population. However, if human intervention is required to keep reproductive rates high enough to maintain populations (Phillips et al., 2015b), or if seed needs to be collected for propagation or seed banks, then sampling of genotypes from the population needs to be carefully considered. While a single fruit can provide sufficient seed to propagate a large number of adult plants (Arditti and Ghani, 2000), as already noted, the seeds may have been fathered by only one or a few sires (Trapnell and Hamrick, 2005; Kopf and Renner, 2008; Whitehead et al., 2015). As such, seed needs to be collected from a variety of individuals, with a diversity of fathers, to avoid any potential issues associated with low genetic diversity during later stages of the conservation programme. If hand pollinations are used to increase reproductive output, pollen could be selected to maximize paternal diversity (e.g. pollen mixes from multiple plants), or pollen donors used that may confer higher fitness on the offspring. When sourcing pollen from within populations, targeting plants beyond the distance over which there is positive spatial genetic structure (usually less than 10 m for orchids; see Peakall and Beattie, 1996; Chung et al., 2004; Jacquemyn et al., 2007b; though see Trapnell et al., 2004) may lead to seed of higher fitness.

Conservation consequences of dust-like seed and high dispersal

Genetic rescue as a viable management option for orchids. Genetic rescue (the artificial transfer of genes/individuals to counteract the negative fitness effects of inbreeding depression) has been a successful management action for rare species of plants and animals in both natural populations and those initiated through conservation translocation (Frankham, 2015). However, when there is local adaptation (Leimu and Fischer, 2008) and/or pronounced genetic differences among populations, crosses between such populations could pose a risk of outbreeding depression. Therefore, unless there are experimental data to the contrary, genetic rescue is only advised in populations that are from broadly similar environments, have experienced relatively recent gene flow (within last 500 years), do not have chromosomal differences and are not autogamous (Frankham et al., 2011).

To our knowledge, very few published studies have considered the risks and benefits of genetic rescue in orchids. One exception is a recent experimental study by Del Vecchio et al. (2019) on Himantoglossum adriaticum. They showed that experimental pollination of plants in small populations, using pollinia transferred from large populations, led to higher in vitro germination rates in the small populations. This result indicates that genetic rescue may be effective in some of the smaller populations of this species. Similar studies that also track the fitness of experimental crosses through to adulthood would be of particular interest in groups of orchids that are more likely to show outbreeding depression, such as predominantly self-pollinating species.

We predict that genetic rescue will be a viable management option for many orchid species, given that low levels of genetic differentiation are the norm (Phillips et al., 2012; see Fig. 5 for an example where genetic rescue is likely to be beneficial). However, as already noted above, some caution may be needed if chromosome number variation exists. For example, recent estimates suggest that 12–16 % of plant species exhibit cytotype variation (Soltis et al., 2007; Wood et al., 2009; Rice et al., 2015), including several European and Australasian terrestrial orchids (Dawson et al., 2007; Trávníček et al., 2012; Pegoraro et al., 2016). Due to low seed production and depressed offspring fitness in matings between cytotypes (Ramsey and Schemske, 1998), mixed cytotype populations can suffer reduced reproductive output that can lead to the exclusion of one of the cytotypes (Levin, 1975; Fowler and Levin, 1984; Husband, 2000). Similarly, crosses between plant ecotypes can lead to lower seed viability or rates of protocorm formation (Jacquemyn et al., 2018), as well as the potential for maladaptation at later life history stages.

Fig. 5.

Example of the potential benefits of genetic rescue in orchids. (A) The endangered Thelymitra mackibbinii, as of 2017 known from 40 wild plants across three populations (15, 22 and 1 plant per population) in Victoria, Australia. (B) Thelymitra mackibbinii plants grown from seed generated from the remaining wild plants via hand cross-pollination. Using the two largest remaining populations, plants on the left and right are from cross-pollination within populations, while the plants in the centre exhibiting the most robust growth are from cross-pollination between populations. All seedlings shown belong to the F1 generation. Photographs and cultivation by Noushka Reiter.

Given the uncertainties regarding outbreeding depression, when introducing genotypes into an existing population prior experiments should be undertaken to test for any potentially adverse effects from the introduction of foreign genotypes (to at least the F2 generation; Edmands, 2007). An exception to this would be when the recipient population is already down to very low numbers, and the adverse effects of inbreeding depression are already occurring or imminent. Alternatively, when initiating new populations via conservation translocation, the process can be treated as an experiment to test which genotypes are most fit in the recipient site, and if interpopulation crosses lead to increased fitness. This experimental approach is also more likely to maximize evolutionary potential for anticipated future environmental change.

Dependence on mycorrhiza for germination and protocorm growth

Use of effective mycorrhizal fungi for orchid conservation. Laboratory germination studies for both terrestrial and epiphytic orchids have demonstrated that not all fungal species isolated from adult orchids are equally effective at supporting germination [Otero et al., 2005; Bidartondo and Read, 2008; De Long et al., 2013; Meng et al., 2019 (or even fungal individuals; Huynh et al., 2009)], or have the same optimal conditions for germination in the laboratory (Reiter et al., 2018b). Similarly, field studies have shown that the fungal species capable of supporting germination are in some cases a subset of those that associate with the adult (Bidartondo and Read, 2008; Jacquemyn et al., 2010) or a different suite of fungal species altogether (McCormick et al., 2004), or vary between habitats (Ruibal et al., 2017; Reiter et al., 2018b). It follows that for those orchids that associate with multiple fungal species, determining which fungi are most effective will be critical to maximize the success of ex situ conservation, particularly when subsequent relocation to the wild is planned.

Surprisingly, despite well-established techniques being available for the symbiotic germination of terrestrial orchids for several decades (e.g. Clements and Ellyard, 1979; Clements et al., 1986), experiments to determine the most efficacious fungus species appear to be rarely performed. Ideally, fungi would be isolated from wild plants (preferably including protocorms or seedlings) and tested to determine which fungal species support high germination rates or yield the most vigorous seedlings. To account for genetic diversity of the symbiotic partner, multiple fungal individuals should be maintained ex situ and used to generate plants for conservation actions. Another interesting possibility that appears to have not yet been applied in orchid conservation is to combine the use of relevant strains of endophytic bacteria with the appropriate mycorrhizal fungi to promote germination and seedling growth. The potential merit of this approach has been demonstrated in an experimental germination study involving the terrestrial orchid genus Pterostylis (Wilkinson et al., 1989), and more recently in a lithophytic species of Dendrobium (Wang et al., 2016).

Not all microsites are equally suitable for germination. In orchids, the suitability of sites for germination is likely to be determined by both the spatial distribution of fungi and the physiological requirements of both orchid and fungus. In both terrestrial and epiphytic species orchid mycorrhizal fungi are generally geographically widespread and often occur across a range of habitat types (Otero et al., 2007; Davis et al., 2015; Phillips et al., 2016; Jacquemyn et al., 2017). However, direct DNA sequencing of fungi from the soil indicates that fungal distribution is highly patchy within sites and is most often correlated with close proximity to orchids and microsite-scale environmental conditions (McCormick et al., 2009, 2018; Waud et al., 2016; Rock-Blake et al., 2017). Furthermore, McCormick et al. (2012) showed experimentally in some North American terrestrial orchids that increasing the availability of rotting wood increased both fungal abundance and germination, but that the effect differed depending on the stage of wood decomposition. In another terrestrial orchid, Isotria medeoloides, higher abundance of fungi at the microsite scale also appears to increase the probability that the plant emerges from dormancy (Rock-Blake et al., 2017). Taken together, this evidence indicates that during orchid translocation the choice of appropriate microsites could strongly increase the vigour of adult plants. Therefore, managing sites to encourage growth of orchid mycorrhizal fungi could lead to increases in orchid populations.

INNOVATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Improving survival in conservation translocations

Given that conservation translocations are an increasingly common approach for the preservation of endangered orchids, and that even in successful translocation projects orchids still experience mortality in the year after planting (Reiter et al., 2016), optimizing the planting process could substantially increase the number of wild plants. In general, there appear to have been few experimental tests of the roles of size, age and season of planting on the success of translocations of wild orchids (though see Smith et al., 2009). However, in terrestrial orchids the use of seed burial trials has been a common strategy to investigate the suitability of particular microhabitats for supporting germination (e.g. Rasmussen and Whigham, 1993; Batty et al., 2001; Diez, 2007; Phillips et al., 2011). Unfortunately, germination does not guarantee microsite suitability for the adult plant and, for many endangered orchids, insufficient supplies of seed may severely limit the opportunity to use this approach. In Table 3 we compare and contrast seed baiting with other approaches that have been employed for investigating microsite suitability that may be less wasteful of seed. Some of these alternatives, such as experimental plantings, also offer crucial insights into the microsite’s ability to support both seedlings and adult plants. In addition, it would be of interest to test if survival of plants is increased by deliberately inoculating the sites with suitable orchid mycorrhizal fungi (e.g. Hollick et al., 2007), or if this is already achieved via the introduction of symbiotically grown plants.

Table 3.

Benefits and drawbacks of alternative methods for investigating microsite suitability for the introduction of orchids. Note that the references were not necessarily studies designed to identify introduction sites, but rather were chosen to illustrate applicable methods

| Technique | Benefits | Drawbacks | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seed burial trials | Tests for germination in the wild | Uses large quantities of seed. May be capable of germinating but not surviving through to adulthood. Results affected by environmental conditions when experiment was done. | Batty et al. (2001) Phillips et al. (2011) |

| Use species that share mycorrhizal fungi as a guide | No wastage of seed | Need to confirm which species share fungi. Orchid species may show differences in habitat preferences. | |

| Introduce symbiotically propagated orchids | Introduced orchids contain effective fungi No wastage of seed | Site may not be suitable for fungus and/or plant in the long term. | Reiter et al. (2016) Reiter et al. (2018a) |

| Microhabitat of adult plant | No wastage of seed | Assumes knowledge of variables likely to be important for seed germination and adult growth. | Menz (2013) |

| Experimental planting in microsites with different habitat features | Experimental test | Assumes knowledge of variables likely to be important for seed germination and adult growth. Spare seedlings needed for experimentation. | Reiter et al. (2018b) |

| DNA sequencing of soil | Can detect the presence of fungi in the absence of orchids | Presence of fungus does not guarantee germination or survival to adulthood. | McCormick et al. (2016) |

While most orchid conservation translocations have been attempted with terrestrial species, a few have now been undertaken with epiphytes with some success, at least as far as achieving flowering and fruiting (Izuddin et al., 2018). However, many of these cases have been conservation translocations into heavily modified habitats (Izuddin et al., 2018). Thus, more work remains to be done to optimize the process in natural habitats, particularly with respect to optimizing the placement of translocated plants. For epiphytes in general, different strata within the trunk and canopy of the tree represent different ecological niches to which different species are adapted (Johansson, 1974; Gentry and Dodson, 1987). Similarly, while true host specificity is rare among epiphytes (though see Tremblay et al., 1998), many epiphytic plants, including some orchids, show a preference for particular host traits or surface characteristics (Callaway et al., 2002; Crain, 2012; Gowland et al., 2013; Wagner et al., 2015; Timsina et al., 2016).

We predict that many translocated epiphytic orchids will exhibit variation in recruitment and survival rates within the canopy, with the most favourable stratum presumably matching the habitat of the adult plants. An experimental test of this prediction was conducted by Kartzinal et al. (2013) for the orchid Epidendrum firmum, where trials with seed packets demonstrated that germination was greatest when the seed was in close proximity to adult plants. Germination was also found to be primarily restricted to large native trees in microsites with high canopy cover. Izzudin et al. (2019) also showed that in some epiphytic species germination was associated with particular host tree traits, such as trunk diameter at breast height and the presence of humus at the microsite. These findings highlight the necessity to identify the microsite characteristics and canopy strata most favourable to germination in order to optimize conservation outcomes in epiphytes. However, it would be of interest to test if the presence of adult plants is a good indicator of germination potential more generally, as the presence of adult plant plants could affect microsite characteristics or be indicative of a shift in the epiphytic community since the population was founded.

Combining experimental and demographic approaches to improve management outcomes

Many threatening processes can impact multiple life history stages but predicting the severity of impact across the different stages is a challenging task. Demographic approaches can be powerful tools for determining which life history stages have the greatest influence on population growth, and how they are affected by environmental or ecological parameters (Schemske et al., 1994; Ehrlén et al., 2016). Not only do these approaches provide the ability to test the effectiveness of different management regimes, but such studies can be used to test if a population is declining and so requires additional conservation actions (Menges, 2008).

To maximize the benefits of demographic analysis, both experimental and control treatments should be applied within the same study site. A good example of this approach was the work of Sletvold et al. (2010), who investigated the effects of different mowing regimes on the grassland orchid Dactylorhiza lapponica by combining a long-term demographic study with treatments of different mowing practices. While populations persisted in the absence of mowing due to the high rates of adult survival, population sizes increased in the presence of traditional mowing. Because many terrestrial orchids typically exhibit dormancy (Kery and Gregg, 2004; Shefferson et al., 2005a, 2011, 2018; Coates et al., 2006; Tremblay et al., 2009; Hutchings, 2010), investigating the effects of different management regimes will require the monitoring of populations over several years before experimental treatments are applied, and then for several to many years thereafter to ensure that the final census accurately reflects the number of individuals.

A major research gap is the need to identify the specific local or regional management issues that adversely affect orchids. Among terrestrial orchids, some of the key local factors that have been linked to population declines include a lack of grazing or mowing of grasslands (e.g. Europe, Willems, 2001; Wotavová et al., 2004; Sletvold et al., 2010), inappropriate fire regimes (e.g. Australia, Coates et al., 2006; Jasinge et al., 2018; USA, Primack et al., 1994; Madagascar, Whitman et al., 2011), weed invasion (e.g. Australia, Scade et al., 2006), herbivory (e.g. Australia, Faast and Facelli 2009), trampling (e.g. Ballantyne and Pickering, 2011) and collection by humans (Hinsley et al., 2018). Epiphytes are less well studied, but factors implicated in population declines include herbivores (Winkler et al., 2005), a reduction in precipitation (Zotz and Schmidt, 2006) and fire invasions from drier adjoining habitats (Cribb et al., 2003). Unfortunately, many of the predicted drivers of orchid population decline have not been fully investigated by combined experimental and demographic approaches. However, such tests are urgently needed to confirm the extent of the threat and how it is best mitigated.

Demographic data to inform assisted migration

Assisted migration is the translocation of species beyond their natural range as a conservation measure, and is often advocated as a potential strategy to help mitigate the effects of climate change on threatened species (Thomas, 2011; for a debate over the merits of the approach see McLachlan et al., 2007; Ricciardi and Simberloff, 2009). For assisted migration to be effective, the introduced population must be able to maintain positive growth rates in both current and future climatic conditions. Therefore, wherever possible, long-term demographic and climatic data should be used to predict suitable sites for orchid translocation [e.g. the use of integrated projection models (Merow et al., 2014)], as well as provide guidance on the optimal conditions for the translocation itself. The widespread geographical ranges of orchid mycorrhizal fungi (Jacquemyn et al., 2017) and the wide range of fungal species associated with many orchids (e.g. Jacquemyn et al., 2010; De Long et al., 2013; Waud et al., 2017) suggest that their availability should not constrain the geographical region in which assisted migration could occur, assuming that the symbiosis remains effective outside of the orchid’s current geographical range. On the other hand, for the many orchids with specialized pollination strategies the geographical ranges of the pollinator, not the fungi (e.g. Phillips et al., 2014a; Davis et al., 2015), may well constrain the geographical regions in which assisted migration will be effective.

Integrating orchids into restoration programmes

The increasing number of large-scale restoration projects attempting to offset the extensive worldwide habitat clearing of the past three centuries (e.g. Miller et al., 2017) raises the question of whether these may offer opportunities to incorporate orchids into restored landscapes. Such restoration projects can be grouped into three broad categories that are likely to have different implications for orchids: (1) changing management approaches to a particular vegetation community (e.g. reinstating traditional grazing); (2) attempting to recreate original habitat after vegetation removal, but with the original abiotic soil properties largely intact; and (3) bringing vegetation back to a cleared landscape with highly altered soil properties (e.g. a tailings dump from mining). While there is some dispersal limitation if relying on natural colonization into restored sites (De Hert et al., 2013), in Europe there are several cases of the successful restoration of orchid habitat following re-establishment of mowing and/or grazing regimes (Willems, 2001; Wotavová et al., 2004; Sletvold et al., 2010; Schrautzer et al., 2011; Gijbels et al., 2012). Further, some orchids are known to colonize highly modified habitats (e.g. Shefferson et al., 2008). However, evidence from Australia and Puerto Rico has shown that some orchid species can struggle to colonize habitats where restoration has been attempted (Grant and Koch, 2003; Bergman et al., 2006), highlighting the need to adapt restoration approaches to local conditions and species.

Several key steps may be relevant for restoring orchids in highly modified landscapes lacking natural vegetation (e.g. restoration types 2 and 3 above). Based on other groups of soil fungi (e.g. Emam, 2016; Wubs et al., 2016), the use of topsoil could be an effective source of inoculum of orchid mycorrhizal fungi. However, because orchid seeds are short-lived, with a relatively small (Whigham et al., 2006) or non-existent soil seed bank (Batty et al., 2000), stored topsoil may be ineffective for providing propagules. Germination rates of orchids are also typically very low, even in the presence of suitable orchid mycorrhizal fungi (Hollick et al., 2007), meaning that in most cases the introduction of symbiotically grown plants may be the most effective method for establishing new populations. While the suitability of habitat for germination and adult orchids can be manipulated at the microsite scale (McCormick et al., 2012), the dependency of orchids on other ecological partners (mycorrhizas, pollinators, and phorophytes in epiphytes) means that many orchids may need to be introduced at later stages in the restoration process, once their ecological partners are already established. An interesting corollary of the observation that germination is highest near adult plants (e.g. Diez, 2007) is that during restoration it may be best to introduce additional orchids into microsites where establishment has already occurred.

The capacity of some tropical forests to rapidly regenerate suggests that at least partial restoration of epiphytic orchid communities will be possible. Furthermore, some epiphytic orchids regularly persist in remnant paddock trees (Köster et al., 2009; Kartzinel et al., 2013; Böhnert et al., 2016), remnant edges or secondary growth (Williams-Linera et al., 1995; Hundera et al., 2013). However, often the species of highest conservation concern will be those that occupy primary forest habitats (Hietz, 2005). Unfortunately, such species are likely to be susceptible to landscape modification, and their establishment in restored landscapes may prove to be particularly challenging. Reid et al. (2016) demonstrated that in restored forest communities epiphytic angiosperms reached their highest species richness when in close proximity to existing forest. Therefore, the retention of nearby intact forest may hold the key to achieving the rapid restoration of diverse orchid communities.

CONCLUSIONS

Exceptional opportunities provided by orchids

Due to the unusual life cycle of orchids, their effective conservation can present unique challenges, but also novel opportunities. For example, while many orchid species exhibit highly specialized pollinator and fungal interactions, these relationships are often effective even at small population sizes. Therefore, given the evidence in other organisms for persistence through surprisingly small genetic bottlenecks and the potential to use genetic rescue, we believe that conservation biologists should not be deterred from working on orchid species with small population sizes. Furthermore, orchids produce very large numbers of seed per capsule and, with good horticultural practice, can provide the raw material for both conservation programmes and scientific experiments, even in particularly rare species (e.g. Reiter et al., 2019).

The combination of long-term demographic data and experimental approaches to test the effectiveness of alternative management strategies is potentially a powerful approach for plant conservation (e.g. Sletvold et al., 2010). Among plants, the collection of long-term demographic data should be particularly achievable for orchids, as there is an exceptional capacity to use citizen scientists with a passion for orchids to contribute to data collection (e.g. Reiter and Thomson, 2018). Given the tremendous theoretical and practical inroads in our knowledge of orchid biology, the challenge that remains for scientists and practitioners is how best to use this growing knowledge to deliver large-scale, effective orchid conservation programmes.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at https://academic.oup.com/aob and consist of the following. Table S1: summary of studies that have quantified the diversity of putative mycorrhizal associates in orchid species.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Michael Whitehead, Myles Menz, Dennis Whigham and three anonymous reviewers for comments that improved the final version, and Michael Whitehead, Santiago Ramirez and David Caron for the use of images in figures.

FUNDING

This work was supported by an Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Early Career Research Award (DE150101720) to R.D.P.; grants from the Wimmera Catchment Management Authority (National Landcare Program), Department of Land Water and Primary Industry community grants, Grampians Threatened Species Hub, Saving our Species funding NSW Office of Environment and Heritage, and the Office of the threatened Species Commissioner to N.R.; and ARC Discovery Project (DP150102762) and ARC Linkage Projects (LP110100408 and LP130100162) to R.P.

LITERATURE CITED

- Ackerman J, Montalvo A. 1990. Short- and long-term limitations to fruit production in a tropical orchid. Ecology 71: 263–272. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman JD. 1983. Specificity and mutual dependency of the orchid-euglossine bee interaction. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 20: 301–314. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman JD, Ward S. 1999. Genetic variation in a widespread, epiphyte orchid: where is the evolutionary potential? Systematic Botany 24: 282–291. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht MA, Maschinski J. 2012. Influence of founder population size, propagule stages, and life history on the survival of reintroduced plant populations. In: Maschinski J, Haskins KE, eds. Plant reintroduction in a changing climate. Seattle: Island Press/Center for Resource Economics, 171–188. [Google Scholar]

- Allee WC, Emerson AE, Park O, Park T, Schmidt KP. 1949. Principles of animal ecology. Philadelphia: Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SH, Kelly D, Ladley JJ, Molloy S, Terry J. 2011. Cascading effects of bird functional extinction reduce pollination and plant density. Science 331: 1068–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arditti J, Ghani AKA. 2000. Numerical and physical properties of orchid seeds and their biological implications. New Phytologist 145: 367–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arduino P, Verra F, Cianchi R, Rossi W, Corrias B, Bullini L. 1996. Genetic variation and natural hybridization between Orchis laxiflora and Orchis palustris (Orchidaceae). Plant Systematics and Evolution 202: 87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Argue CL. 2012. The pollination biology of North American orchids: Volume 1. North of Florida and Mexico. London:Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster WS. 2017. The specialization continuum in pollination systems: diversity of concepts and implications for ecology, evolution and conservation. Functional Ecology 31: 88–100. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong DP, Seddon PJ. 2008. Directions in reintroduction biology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 23: 20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government 2019. EPBC Act List of Threatened Flora. http//www.environment.gov.au/cgibin/sprat/public/publicthreatenedlist.pl?wanted=flora (10 December 2019).

- Avila-Díaz I, Oyama K. 2007. Conservation genetics of an endemic and endangered epiphytic Laelia speciosa (Orchidaceae). American Journal of Botany 94: 184–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne M, Pickering C. 2011. Ecotourism as a threatening process for wild orchids. Journal of Ecotourism 11: 34–47. [Google Scholar]

- Batty AL, Dixon KW, Sivasithamparam K. 2000. Soil seed bank dynamics of terrestrial orchids. Lindleyana 15: 227–236. [Google Scholar]

- Batty AL, Dixon KW, Brundrett MC, Sivasithamparam K. 2001. Constraints to symbiotic germination of terrestrial orchid seed in a Mediterranean bushland. New Phytologist 152: 511–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayman P, Lebron LL, Tremblay RL, Lodge DJ. 1997. Endophytic fungi in roots and leaves of Lepanthes (Orchidaceae). New Phytologist 135: 143–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayman P, Gonzalez EJ, Fumero JJ, Tremblay RL. 2002. Are fungi necessary? How fungicides affect growth and survival of the orchid Lepanthes rupestris in the field. Journal of Ecology 90: 1002–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Beer JG. 1863. Beiträge zur Morphologie und Biologie der Familie der Orchideen. Vienna: Carl Gerolds Sohn. [Google Scholar]

- Benzing DH. 1990. Vascular epiphytes. Melbourne, FL:Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman E, Ackerman JD, Thompson J, Zimmerman JK. 2006. Land-use history affects saprophytic orchid Wullschlaegelia calcarata in Puerto Rico’s Tabonuco forest. Biotropica 38: 492–499. [Google Scholar]

- Bidartondo MI, Read DJ. 2008. Fungal specificity bottlenecks during orchid germination and development. Molecular Ecology 17: 3707–3716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesmeijer JC, Roberts SP, Reemer M, et al. 2006. Parallel declines in pollinators and insect-pollinated plants in Britain and the Netherlands. Science 313: 351–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohman B, Phillips RD, Menz MHM, et al. 2014. Discovery of pyrazines as pollinator sex pheromones and orchid semiochemicals: implications for the evolution of sexual deception. New Phytologist 203: 939–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohman B, Flematti GR, Barrow RA, Pichersky E, Peakall R. 2016. Pollination by sexual deception – it takes chemistry to work. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 32: 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohman B, Phillips RD, Flematti GR, Barrow RA, Peakall R. 2017. The spider orchid Caladenia crebra produces sulfurous pheromone mimics to attract its male wasp pollinator. Angewandte Chemie 129: 8575–8578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhnert T, Wenzel A, Alternhövel C, et al. 2016. Effects of land use on vascular epiphyte diversity in Sumatra (Indonesia). Biological Conservation 202: 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Borba EL, Felix JM, Solferini VN, Semir J. 2001. Fly-pollinated Pleurothallis (Orchidaceae) species have high genetic variability: evidence from isozyme markers. American Journal of Botany 88: 419–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bougoure J, Ludwig M, Brundrett M, et al. 2013. High-resolution secondary ion mass spectrometry analysis of carbon dynamics in mycorrhizas formed by an obligately myco-heterotrophic orchid. Plant, Cell and Environment 39: 1123–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bougoure JJ, Brundrett MC, Grierson PF. 2009. Identity and specificity of the fungi forming mycorrhizas with the rare myco-heterotrophic orchid Rhizanthella gardneri. Mycological Research 113: 1097–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower CC. 2006. Specific pollinators reveal a cryptic taxon in the bird orchid, Chiloglottis valida sensu lato (Orchidaceae) in south-eastern Australia. Australian Journal of Botany 54: 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Breitkopf H, Schlüter PM, Xu S, Schiestl FP, Cozzolino S, Scopece G. 2013. Pollinator shifts between Ophrys sphegodes populations: might adaptation to different pollinators drive population divergence? Journal of Evolutionary Biology 26: 2197–2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittain CA, Vighi M, Bommarco R, Settele J, Potts SG. 2010. Impacts of a pesticide on pollinator species richness at different spatial scales. Basic and Applied Ecology 11: 106–115. [Google Scholar]

- Brundrett MC. 2019. A comprehensive study of orchid seed production relative to pollination traits, plant density and climate in an urban reserve in Western Australia. Diversity 11:123. [Google Scholar]

- Brzosko E, Ostrowiecka B, Kotowicz J, et al. 2017. Seed dispersal in six species of terrestrial orchids in Biebrza National Park (NE Poland). Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae 86: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Callaway RM, Reinhart KO, Moore GW, Moore DJ, Pennings SC. 2002. Epiphyte host preferences and host traits: mechanisms for species-specific interactions. Oecologia 132: 221–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo RN, Horvitz CC. 1990. Pollinator limitation, cost of reproduction, and fitness in plants: a transition matrix demographic approach. American Naturalist 136: 499–516. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron DD, Leake JR, Read DJ. 2006. Mutualistic mycorrhiza in orchids: evidence from plant-fungus carbon and nitrogen transfers in the green-leaved terrestrial orchid Goodyera repens. New Phytologist 171: 405–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron DD, Johnson I, Read DJ, Leake JR. 2008. Giving and receiving: measuring the carbon cost of mycorrhizas in the green orchid Goodyera repens. New Phytologist 180: 176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung MY, Chung MG. 2007. Extremely low levels of genetic diversity in the terrestrial orchid Epipactis thunbergii (Orchidaceae) in South Korea: implications for conservation. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 155: 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Chung MY, Nason JD, Chung MG. 2004. Spatial genetic structure in populations of the terrestrial orchid Cephalanthera longibracteata (Orchidaceae). American Journal of Botany 91: 52–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claessens J, Kleynen J. 2011. The flower of the European orchid: form and function. Geuelle: Jean Claessens and Jacques Kleynen. [Google Scholar]

- Clements MA, Ellyard RK. 1979. The symbiotic germination of Australian terrestrial orchids. American Orchid Society Bulletin 48: 810–818. [Google Scholar]

- Clements MA, Cribb PJ, Muir H. 1986. A preliminary report on the symbiotic germination of European terrestrial orchids. Kew Bulletin 14: 437–445. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Cingel NA. 1995. An atlas of orchid pollination: European orchids. Rotterdam: A. A. Balkema. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Cingel NA. 2001. An atlas of orchid pollination: Orchids of America, Africa, Asia & Australia. Rotterdam: A.A. Balkema. [Google Scholar]

- Coates F, Lunt ID, Tremblay RL. 2006. Effects of disturbance on population dynamics of the threatened orchid Prasophyllum correctum D.L. Jones and implications for grassland management in south-eastern Australia. Biological Conservation 129: 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Crain BJ. 2012. On the relationship between bryophyte cover and the distribution of Lepanthes spp. Lankesteriana 12: 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cribb PJ, Kell SP, Dixon KW, Barrett RL. 2003. Orchid conservation: a global perspective. In: Dixon KW, Kell SP, Barrett RL, Cribb PJ, eds. Orchid conservation. Kota Kinabalu: Natural History Publications, 1–24. [Google Scholar]