Abstract

COVID-19 has dramatically challenged the healthcare system of almost all countries. The authorities are struggling to minimize the mortality along with ameliorating the economy downturn. Unfortunately, till now, there has been no promising medicine or vaccine available. Herein, we deliver a perspective of nanotechnology for increasing the specificity and sensitivity of current interventional platforms towards the urgent need of quickly deployable solutions. This review summarizes the recent involvement of nanotechnology from the development of biosensor to fabrication of multifunctional nanohybrid system practiced for respiratory and deadly viruses, along with the recent interventions and current understanding about SARS-CoV-2.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, viruses, pandemic, nanotechnology, nanomaterials, nanosensors, curcumin, niclosamide, theranostics

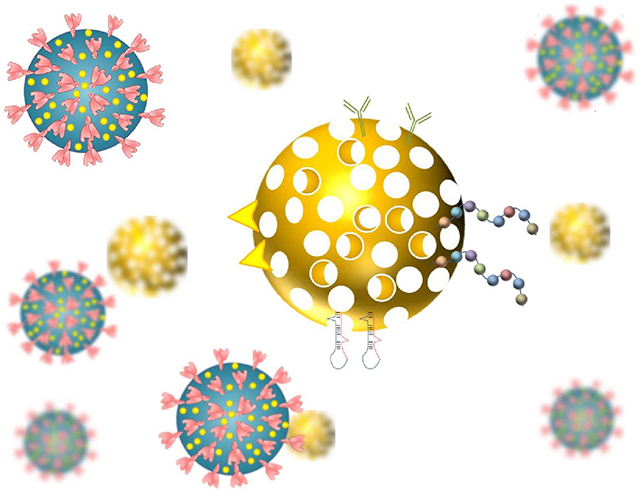

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is popularly named as novel coronavirus 2019 disease (nCoV-2019 or COVID-19) 1. The emergence of COVID-19 is not the first pandemic due to coronaviruses. In the last decade, the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS, 2002 and 2004) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS, 2012) has shown the capability to cross the interspecies barrier and infect humans. Different from earlier coronavirus outbreaks, COVID-19 has spread to more than 100 countries with millions of cases and thousands of deaths, sparking international health organizations to declare a global health emergency 2. It appears that the moderate mortality rate, high infection rate, and longer incubation period of SARS-CoV-2 are the perfect combination for prolonging the pandemic. This pandemic can induce the ripple effect and hard challenges to the global health system along with serious financial crisis. In many countries, hospitals have compromised with the shortage of doctors, nurses, and trained personnel due to crowding of COVD-19 patients. Almost all countries are facing the issue of shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE), ventilators, and other critical medical equipment.

Initially, a very low number of cases were reported due to lack of resources and inability to distinguish between common flu and COVID-19. For example, Indonesia has reported only 2 cases 3. However, there is much tourism from China. Now several nucleic acid and protein-based diagnostic tests are available for the COVID-19. A few repurposed drug candidates are also under clinical trials but none of them has shown good efficacy without major safety issues 4 5. Additionally, some of the vaccines have entered phase I, phase II, and even phase III clinical trials 6. Apparently, the final approval may take more than 12 months; realising the sense of urgency, interdisciplinary and deployable solutions are highly sought to control this pandemic.

Nanotechnology, an interest of chemistry, physics, biology, and medicine disciplines, emerged as a medically viable approach to enhance the efficacy of the system(s) with minimal efforts and resources. In general, nanotechnology-based interventions increase the specificity, selectivity, sensitivity, and multiplexing characteristics of the diagnostic tests 7–9. In terms of therapeutic perspective, nanotechnology can help to develop targeted delivery of therapeutics to avoid the severe systemic side-effects of regimen 10. The recent extensive exploration of the drug carriers towards enhancing their biocompatibility, biodegradability, and eco-friendly nature has opened the door of nanotechnology for a wide range of healthcare applications. Overall, nanotechnology advancements can be helpful not only to track COVID-19 but offer innovative and affordable therapeutic solutions. Apart from therapeutic perspectives, there is a lot of scope of nanotechnology in early and accurate detection of COVID-19. In addition, nanotechnology can be applied to the prevention purposes that includes disinfecting surfaces to nanotextile coating for achieving improved viral inhibition or trap.

Keeping the unmet clinical needs of current pandemic, we aim to document various aspects such as etiology, pathogenicity, repurposed drugs, biologics, diagnostic, and prevention techniques of COVID-19. Additionally, this review is comprised in reference to nanotechnology advancements for helping the researchers to relate things together and follow up their research accordingly.

2. COVID-19: Epidemiology, Etiology, and Pathogenesis

COVID-19 is primarily linked to an increase in the pneumonia cases in the hospitals of Wuhan, and the sources were traced to the Huanan seafood market 11. In Dec. 12, 2019, the first COVID-19 patient was declared to suffer from ‘unexplainable pneumonia,’ and later, 27 viral pneumonia cases with similar symptoms were officially announced on 31 Dec. 2019. On 22 Jan. 2020, pathogen has been declared as a novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, that has been originated from the wild bats 12, 13. Earlier SARS outbreak was during the Spring Festival of China (Jan. 17 to Feb. 23 in 2003). Similarly, COVID-19 also detected and lasted the duration of festival. A record-high transmission of viral disease and its associated death was primarily due to an increase in the number of travelers (3.11 billion vs. 1.82 billion) 1. This became pandemic in almost all counties due to extensive Chinese traveling around the globe.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), as of July 02, 2020, the total number of COVID-19 cases registered is 10,514,028 with 512,311 of death worldwide 14. The human to human transmission of COVID-19 has been noticed as virus spread from either close contact or droplets 15, 16. The reproductive number of viral transmit infection has been determined to be around 2.20 and 3.58 17. However, further studies need to be conducted to clearly define the dynamics of transmission. The male to female fatality ratio was found to be 2.4:1, and the median mortality age is 70.3, with IQR (65–81) years 18. The median time from symptoms to death is 14 days, with an average incubation period of 5.2 days. It has been found longer (20 days) in under 70 years old patients. These studies suggest a high risk of old age than the younger. Online sources represent that the higher mortality was found in African American and Hispanic population in the US. The major risk factor for COVID-19 is other chronic diseases, such as diabetics, cardiovascular, and hypertension 19.

COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2 is a single-stranded RNA virus with a length of 29903 bp and a diameter of ~ 50–150 nm 20. The shape of this novel virus varies from spherical to oval, or pleomorphic morphology, Figure 1. This belongs to the subgenus Sarbecovirus and genus Betcicoronavirus. The culture time varies from 4–6 days, as observed in human airway epithelial cells and Vero E6/Huh-7 cell lines 21.

Figure 1.

Schematic representing the structure and morphology of SARS-CoV-2.

The organization of the RNA is followed as 5’-leader-UTR-replicase-S-E-M-N-3’-UTR-poly A tail with unknown open reading frames; wherein S (spike), E (envelope), M (membrane) and N (nucleocapsid) 22, Figure 2. It has 80.26% sequence identity with query coverage over 98% to the human SARS-CoV genome 23. Pangolins are considered being the intermediate host as Guangdong pangolin coronavirus has very high sequence similarity in the receptor-binding domain to SARS-CoV-2. The SARS-CoV-2 enters the host cells via angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor 24, Figure 2. This receptor is highly expressed in the lungs, upper oesophageal epithelial cells, enterocytes of the ileum and colon, and kidney tubules. Thus, indicate the respiratory and digestive routes are the potential entry door for infection 25, 26.

Figure 2.

SARS-CoV-2 genome organization, proteins codified, and sequence comparison in the region of S1/S2 boundary. Inset- illustrating ACE2 interaction with the RBD of SARS-CoV-2. Abbreviation: PPC- proprotein convertase, NTD- N-terminal domain, RBD- receptor binding domain, FP- fusion peptide, HR1- heptad repeat 1, HR2- heptad repeat 2, S1- receptor binding subunit, S2- membrane fusion subunit, TM- transmembrane anchor, IC- intracellular tail, NSP- non-structural protein.

A study revealed that spike proteins of SARS-CoV-2 bind to the ACE2 receptors of the airway passage cells, which cause the entry into the cells 27 ACE2 is a homolog of ACE, an enzyme known for controlling hypertension. It is a transmembrane metallocarboxypeptidase (primary substrate- angiotensin II) and key players in renin-angiotensin system. Although the binding of SARS-CoV-2 to the ACE2 is not as strong as SARS-CoV, it is above the threshold and sufficient for infection 28. Recent findings also suggest that some of the folds may bind tighter in comparison to SARS-CoV 29. ACE2 facilitated entry of SARS-CoV-2 was examined systematically in the HeLa cells and Vero-E6 cells 16, 25, 30. Further, it was noticed that Gln493 residue of COVID-19 receptor binding motif helps in maximizing the interaction with the ACE2 31.

The spike (S) protein is a homotrimer glycoprotein and composed of two subunits responsible for binding to host cell receptor and fusion of virus and host cell membrane 22, 31, 32. At the boundary of the cell membrane, S protein is cleaved into the S1 and S2 subunit without breaking apart. The S1 subunit binds to the receptor while maintaining the prefusion conformation of S2 subunit (contains the fusion machinery) for fusion with the host cell membrane. S protein priming is necessary for the fusion of SARS-CoV, i.e., breakage of S protein by cellular protease at S2’ sites. It leads to the activation of protein by rendering irreversible change in the confirmation. The extensive decoration of S protein with N-linked glycans helps in the proper folding and thus accessing the host proteases, Figure 2. For priming, Transmembrane Serine Protease 2 (TMPRSS2) is responsible 30. Consequently, the Calu-2 human lung cell lines treated with the camostat mesylate (a serine protease inhibitor) efficiently blocked the partial infection of SARS-CoV-2.

The alveolar type I and II epithelial cells express the ACE2 receptor 33. However, RNA profiling studies show that viral receptor ACE2 is concentrated in alveolar type II epithelial cells and express 20 other genes helpful in virus replication and transmission. It is important to note that ACE2 is expressed in only 0.64% of all human lung cells. The expression of ACE2 is correlated with the differentiation state of epithelial cells 34. The fully differentiated cells (apical surfaces expressing more ACE2) are prone to viral infection, while poorly differentiated cells (express less ACE2) remain poorly infected. SARS-CoV-2 infection relates to the state of the cells, ACE2 expression, as well as ACE2 localization. The percentage of ACE2 positive cells is higher in Asians (2.5%) compared to Africans and Caucasians (0.47%) 35. Also, ACE2 expression is higher in males than females 36.

The lack of correlation between the mRNA expression and enzyme activity of ACE2 has been established using the drugs, lisinopril, and losartan 37 Lisinopril treatment found to increase the ACE2 mRNA level but not activity, while losartan treatment increased both the activity and expression level of ACE2. Moreover, combination of losartan and lisinopril treatment has shown no increase in activity and offset in the level of ACE2 mRNA. This study suggests the involvement of angiotensin via ACE inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor antagonist (ARB) to regulate the ACE2 expression and activity. The correlation between hypertension drugs, ACE2 expression, and activity need to be properly established for controlling the COVID-19.

3. Diagnosis and Current Treatment

It is highly difficult to differentiate the COVID-19 using common clinical tests from other respiratory disorders (influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human metapneumovirus, other coronaviruses, bacterial, mycoplasma, and chlamydia infections) 38. The patients’ average age for COVID-19 infection is much higher than the MERS and H1N1 39, 40. Most of the COVID-19 patients are suffering from chronic comorbidities and undergo silent hypoxemia, i.e., no symptoms of respiratory failure. Some patients have the failure of other vital organs, kidney, liver, and lungs, before the respiratory failure. Thus, the new early warning score and quick sequential organ failure assessment may not help in foreseeing the respiratory failure 41.

3.1. Diagnosis

The impact of early detection offers prevention of potential cases, while delayed reporting leads to minimal control of contagious diseases 42–44. Currently, there are number of nucleic acid, and protein-based diagnostic tests are available, Table 1. However, there is also an urgent need for point of care (POC) devices for rapid, cost-effective, and self-diagnosis.

Table 1.

Currently available diagnostic tests for COVID-19

| Product | Company | LOD | Time | Sensitivity % (LOD dilution) | Specifi city % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests | |||||

|

| |||||

| Qeust SARS-CoV-2 rRT-PCR | Quest | 136 copies/mL | 96–120 h | 95% (1X) | 100 |

| NY SARS-CoV-2 Real-time RT-PCR | Wadsworth Center, NY state | 25 copies/reaction | 24–72 h | 100 (2X) | 100 |

| 2019-nCoV Real-Time RT- PCR Dx Panel | CDC | 1000 copies/ml | 24–72 h | 100 (1X) | 100 |

| AvellinoCoV2 | Avellino labs | 55 copies/pL | 24–48 h | 100 (1X) | 100 |

| Covid-19 RT-PCR test | LabCorp | 6.25 copies/pL | 24 h | 95 (1X) | 100 |

| Cobas SARS-CoV-2 Test Roche | Roche | 17 – 58 copies/mL | 24 h | 100 (1.5X) | 100 |

| COV-19 IDx Assay | Ipsum | 8500 copies/mL | 24 h | 100 (1X) | 100 |

| RealTime SARS-CoV-2 | Abbott | 100 copies/mL | 4–6 h | 100 % (1–2X) | 100 |

| New Coronavirus RT-PCR | PerkinElmer | 8.3 copies/mL | 4–6 h | 100% (1.5X) | 100 |

| GeneFinder COVID-19 RealAmp Kit | OsangHealthcare | 0.5 copies/pL | 4–6 h | 100 (1X) | 100 |

| Lyra SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Quidel | 800 copies/mL | 4–6 h | 100 (1X) | 100 |

| NxTAG CoV Extended Panel Assay | Luminex Molecular Diagnostics | 5000 copies/mL | 4 h | 95% (2X) | 100 |

| TaqPath COVID-19 Combo Kit | ThermoFisher | 10 copies/reaction | 4 h | 100 (1X) | 100 |

| Allplex 2019-nCov Assay | Seegene | 1250 copies/mL | 4 h | 95 (1X) | 100 |

| Real-Time Fluorescent RT-PCR kit | BGI | 100 copies/mL | 3 h | 100 % ( 1X) | 100 |

| Panther Fusion SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Hologic | 0.01 TCID50/mL | 3 h | 100 (1–5X) | 100 |

| BD SARS-CoV-2 Reagents | Becton Dickonson | 40 copies/mL | 2–3 h | 100 % (3–5X) | 100 |

| ePlex SARS-CoV-2 test | GenMark Diagnostics | 10 copies/mL | 2 h | 94.4 (1X) | 100 |

| ARIES SARS-CoV-2 Assay | Luminex Molecular Diagnostics | 1000 copies/mL | 2 h | 100 (1X) | 100 |

| COVID-19 genesis Real-Time PCR assay | Primerdesign | 330 copies/mL | 2 h | 100% (3–5X) | 100 |

| DiaPlexQ 2009-nCoV Detection kit | SolGent | 200 copies/mL | 2 h | 100 (1X) | 100 |

| QuantiVirus SARS-CoV-2 Test Kit | DiaCarta | 100 copies/mL | 2 h | 95 (1X) | 100 |

| Logix Smart Coronavirus COVID-19 Test | Co-Diagnostics | 4290 copies/mL | 1–2 h | 100 (1X) | 100 |

| Simplexa COVID-19 Direct | Diasorin Molecular | 500 copies/mL | 1 h | 100 (1X) | 100 |

| QIAstat-Dx Respiratory SARC- Cov-2 panel | Qiagen | 500 copies/mL | 1 h | 100 (1–2X) | 100 |

| Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 testa | Cepheid | 250 copies/mL | <1 h | 100 (2X) | 100 |

| Accula SARS-CoV-2 testa | Mesa Biotech | 100 copies/reaction |

<1 h | 100 (2–50X) | 100 |

| NeuMoDx SARS-CoV-2 Assay | NeuMoDx | 150 copies/mL | <1 h | 100 (1.5X) | 100 |

| ID NOW COVID-19 testa | Abbott | 125 copies/mL | <1 h | 100 % (2–5X) | 100 |

| BIOFIRE COVID-19 test | BioMerieux-BioFire Defence |

330 copies/mL | <1 h | 100 (1X) | 100 |

| Gnomegen COVID-19 RT- Digital PCR Detection Kit | Gnomegen | 60 copies/mL | - | 100 (1–2X) | 100 |

|

| |||||

| Serological Tests | |||||

|

| |||||

| Platelia SARS-CoV-2 Total Ab assay | Bio-Rad | 2 h | 92.2 | 99.6 | |

| VITROS Immunodiagnostic Products Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG |

Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, Inc. | 48 min |

87.5 | 100 | |

| LIAISON® SARS-CoV-2 S1/S2 IgG |

DiaSorin Inc. | 35 min |

97 | 98 | |

| SARS-CoV-2 IgG | Abbott Laboratories Inc. | 29 min |

100 | 99.9 | |

| Elecsys® Anti-SARS-CoV-2 | Roche | 18 min |

100 | 99.8 | |

| Roche’s Elecsys IL-6 | Roche Diagnostics | 18 min |

84 | 63 | |

| Cellex qSARS-CoV-2 IgG/IgM Rapid Test |

Cellex | 15–20 min |

93.8 | 95.6 | |

| Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Rapid Test | Autobio Diagnostics Co. Ltd. (jointly with Hardy Diagnostics) | 15 min |

99 | 99 | |

| COVID-19 Antibody Rapid Detection Kit |

Healgen Scientific LLC | 10 min |

96.7 | 97 | |

| SARS-CoV-2 Total Assay | Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc. | 10 min |

100 | 99.8 | |

| COVID-19 ELISA IgG Antibody Test | Mount Sinai Laboratory COVID-19 ELISA IgG Antibody Test | < 1 h | 92.5 | 100 | |

| Anti-SARS-CoV-2 ELISA IgA and IgG | Euroimmun AG | - | 90 | 100 | |

| New York SARS-CoV Microsphere Immunoassay |

Wadsworth Center, New York State Department of Health | - | 88 | 98.8 | |

| Vibrant COVID-19 Ab assay | Vibrant America Clinical Labs |

- | 98.1 | 98.6 | |

| RightSign™ COVID-19 IgG/IgM Rapid Test Cassette |

Hangzhou Biotest Biotech Co., Ltd |

- | 92.5 | 99.5 | |

| SCoV-2 Detect™ IgG ELISA | InBios International, Inc. | - | 97.8 | 98.9 | |

3.1.1. Nucleic acid-based diagnosis tests

Nucleic acid-based diagnostic tests are the most common for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Isothermal techniques require no specialized equipment, like, polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Reverse transcription loop mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) based tests use the strand displacement polymerase instead of heat to generate the single strand template 45–47 It uses the 4–6 primers and DNA polymerase, which binds to different regions of the target genome, and the amplified DNA is detected by the change in turbidity, which can be reflected in the change in color due to change in pH or fluorescent dye incorporated double-stranded DNA. The reaction completes in less than 1 h at 60–65 °C with ~75 copies that can be easily detected 48. This technique is very specific because of the usage of high number of primers, simple, easy to visualize, less noise, and doesn’t require thermocycler 49. It can also be multiplexed at the reading or amplification stage by functionalizing the beads with different optical signatures or involvement of different genes to cut out the possibility of mutation lead false-negative tests 44, 48. The multiplexing helps to increase the information, specificity, and sensitivity of the tests. However, the challenges of LAMP tests are optimization of conditions and primers.

The CRISPR-based SHERLOCK diagnostic technology test became famous during the Zika outbreak, could also be used for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Herein, the cDNA is synthesized and amplified using isothermal reaction, and then it again converted to RNA. Cas13a bind to amplified RNA, and on specific target binding gets activated, which cuts off the quencher from fluorescence to give the signals 50, 51. It has been reported to detect ~2000 copies/ml from serum and urine of Zika infected patients 52. The optimized protocol for SARS-CoV-2 has been published with different Cas13a detection system and soon might be commercialized 53.

3.1.2. Protein-based tests

For the protein-based tests, antigens and antibodies are used for diagnosis. However, changes in viral load during the course of infection cause difficulties in detection. Like, high viral load in the salivary gland during the first week of infection and later declines 54, 55, Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The standard relation between the changes in analytes level with respect to the course of infection. In general, PCR tests are likely positive in the first week of infection, and likely negative after 3 weeks of infection due to overcome of viral phase with the host response. This trend might vary from person to person. Adapted with permission from reference 55 [Siddiqi, H. K., and Mehra, M. R. (2020) COVID-19 illness in native and immunosuppressed states: A clinical-therapeutic staging proposal. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation: the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation 39, 405–407.].

Antibodies may provide a longer window for the detection; however, cross-reactivity of the antibody with other coronavirus antibody pose the problem 56. Currently, these serological tests are in development to detect asymptomatic patients 57–59. Nucleocapsid protein is highly immunogenic phosphoprotein and most abundant in the virus. It is commonly used for the biomarker tests because it hardly mutates. Zhang et al, have used the Rp3 nucleocapsid protein from SARS-CoV-2 to detect the IgG and IgM antibodies from the COVID-19 patients 57. Rp3 nucleocapsid has been found to have 90% similarity with SARS related virus. The serological tests are performed by adsorbing recombinant protein to the bottom of the multi-well plate, and then diluted patient serum is added to perform ELISA. The horseradish peroxidase functionalized secondary IgG antihuman antibody is added to obtain the signals. If anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG is present, it will be sandwiched between the adsorbed protein and antihuman IgG probe. Similarly, IgM has also been used for the sandwiched assay. It was found that after 5 days of symptoms, antibody level is increased. Like, on day 0 of SARS-CoV-2 infection, only 51% and 81% of patients were found positive for the IgM and IgG respectively, and after five days, it increased to 81% and 100%, respectively. These antibodies may also be found in the suspected cases, as recent studies show other proteins and biomarkers may also be used for the detection 58. Currently, number of serological tests have been approved by FDA for the emergency use authorization (EUA), Table 1.

3.1.3. Lymphopenia-based assessment

It has been observed that the course of the disease was different in different patients, but the variations in blood test parameters were constant from the onset of disease to death or discharge. The lymphocyte percentage was found to be the most consistent and significant parameter for the disease progress 60. For example, in the sample size of 12 patients (death case) with the mean average age of 76, lymphocyte percentage reduced up to 5% in 2 weeks after the disease onset. In case of 7 patients (average age 35, therapeutic time 35 days) with severe symptoms, lymphocytes percentage decreased initially but raised to more than 10% when discharged, however in 11 patients (average age 49, therapeutic window 26 days) with moderate symptoms, lymphocyte percentage was almost constant and higher than 20% on the discharge. It shows that lymphopenia to be one of the reliable parameters for determining the prognosis. The clinical data were collected from the General Hospital of Central Theater Command, Wuhan, China 60.

3.2. Current treatment options

3.2.1. Repurposable Drugs

The repurposing of the drugs that have been approved for other indications has come up as an effective strategy to reduce the cost, time, and risk significantly in comparison to de novo drug development for COVID-19.

3.2.1.1. Chloroquine

Since 1934, the 9-aminoquinoline, known as chloroquine, has been an inexpensive and safe drug for the treatment of malaria and prophylactic measure of autoimmune diseases. Recently, it has also been explored during in vitro studies for the antiviral properties against the HCoV-OC43 and SARS-CoV 61. It has been found to interferes with the ACE2 of the host cells and prevents the interaction of spike proteins of SARS family coronavirus 62. However, the mechanism of action is still speculative. The determination of precise mechanism is important for finding new prophylactic and therapeutic measures. The correlated studies show that chloroquine interferes with the pH-dependent viral fusion and replication, and also glycosylation of the receptor as well as envelope protein 61, 63. Additionally, it also reports the interruption of the assembly in the endoplasmic reticulum - Golgi intermediate compartment. Chloroquine also attenuates the expression of proinflammatory receptors and factors majorly responsible for the SARS-CoV-2 mortality 61, 64.

SARS-CoV-2, similar to synthetic nanoparticles, falls in the same range of shape and size 65, 66. Thus, another mechanism is the suppression of phosphatidylinositol binding clathrin assembly protein (PICALM) for preventing the uptake of nanosized clathrin-mediated endocytosis 67–70, Figure 4. This clathrin-mediated endocytosis path is being used by other members of the Coronaviridae family for entering the host cells. In the case of SARS-CoV, it is known that after binding to ACE2, endocytosis-driven entry of the virus is triggered 71, 72.

Figure 4.

Potential action mechanism of chloroquine against SARS-CoV-2. Chloroquine suppress the expression of PICALM to inhibit the uptake of virus. PICALM is a clathrin assembly protein to assist the uptake of particles. Adapted with permission from reference 70 [Hu, T. Y., Frieman, M., and Wolfram, J. (2020) Insights from nanomedicine into chloroquine efficacy against COVID-19. Nature nanotechnology 15, 247–249.].

Moreover, chloroquine prevents the fusion of endosomes with the lysosome to disturb endocytic trafficking 70. It disrupts the membrane recycling, thus the entry of viruses. The pH change in endosome for the activation of endosomal protease like cathepsin required for the priming of S protein can be disturbed due to chloroquine driven inhibition of endosomal acidification, which leads to stalling of virus in the endosome. Thus, there are chances of multiple mechanisms of action that are reflected in the broad-spectrum nature of the drug. Hydroxychloroquine has been reported to have the same anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity along with a higher safety profile.

Although, FDA suggests that excessive and long-term usage of CQ and HCQ result in eye damage, corrected QT prolongation, neuropsychiatrie effects, and hypoglycemia 73. These risks are amplified several folds when CQ and HCQ are combined with other drugs (e.g., azithromycin) reported prolonging the QT intervals. Further, heart problem is amplified if patient is also suffering from renal diseases. Also, a paper published in reputed journal Lancet corroborated the ineffectiveness of CQ and HCQ either with or without combination of macrolide in the treatment of COVID-19, and also concluded that it might cause the ventricular arrhythmias in the hospitalized patients. All these indicated to revoke the CQ and HCQ EUA 74. This report also halted the enrolling of patients in the WHO Solidarity clinical trial arm and other random clinical trials in different countries. However, shortly after few weeks, this paper was retracted due to conflict between the co-authors due to the veracity of data sources. Meanwhile, a study published in another reputed journal New England Journal of Medicine, again established that CQ and HCQ are not better than placebo in the treatment of COVID-19 hospitalized patients. Although, no comments made on the usage for pre-exposure prophylaxis, which salvaged the continuation of clinical trials in the high-risk population 75.

3.2.1.2. Ribavirin

Ribavirin (tribavirin) is an antiviral medication, a synthetic guanosine analog, widely used to treat hepatitis C, RSV infection, and viral hemorrhagic fever(s). It checks the hepatitis C virus polymerase and shows broad-spectrum effects against other DNA and RNA viruses, Figure 5. This drug was extensively used with or without steroids during the SARS outbreak 76. The higher dose (1.2 to 1.4 g orally in every 8 h) for its effective action poses severe toxicities, e.g., hemolysis and liver injury 77, 78. Its inhalation formulation has also shown no benefits over the oral and intravenous administration. Clinical studies showed that ribavirin could work synergistically with interferon–β and inhibits the SARS-CoV replication. However, blood transfusion was required in 40% of the patients 79. Ribavirin shows teratogen (abnormalities of physiological development) activity, thus not recommended for the pregnant woman 80.

Figure 5.

Action mechanism of small molecules, antivirals, and protease inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2.

3.2.1.3. Lopinavir, ritonavir, and nelfinavir

Lopinavir (LPV) and ritonavir (RTV) are protease inhibitors widely used for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Figure 5. RTV is combined with LPV to increase the half-life by inhibiting the cytochrome P450 81. The LPV/RTV has been combined with ribavirin, which has shown better outcomes in the treatment of SARS 82. Combination therapy using cocktail of interferon-β, LPV/RTV, and ribavirin has been employed for the treatment of MERS-CoV disease 83. This combination therapy is effective within 7–10 days of infection. The known side-effects of this treatment include diarrhea, nausea, and hepatotoxicity. This treatment may pose exacerbated effects in the case of COVID-19 patients (who may already be experiencing liver issues). It is important to note that HIV and SARS-CoV have different proteases; thus, also concern about the specificity of the combination 70. Nelfinavir is a protease inhibitor of HIV, responsible for the post-translational processing 84. It strongly inhibits the replication of SARS-CoV, thus an option for the SARS-CoV-2 85.

3.2.1.4. Remedesivir

Remedesivir (GS-5734™) is a monophosphate prodrug of an adenosine nucleoside analog. Remedesivir has been reported to inhibit the humans and zoonotic coronavirus, including SARS-CoV in in vitro and in vivo studies 86, Figure 5. This molecule shows superior activity (low EC50) and selectivity of host polymerase against the Ebola virus. Remedesivir has been found effective in preventing lung hemorrhage during murine MERS infection lung model. In the case of SAR-CoV-2, the in vitro studies have shown the EC50 to 0.77 μM and EC90 to 1.76 μM 87, 88. In recent reports, the combination of remedesivir and interferon-β was found to have higher efficacy than the triple combination of LPV/RPV, ribavirin, and interferon-β [105]. In the united states, the first COVID-19 patient was treated with remedesivir when the patients’ condition was critical 89. The random and controlled clinical trials of remedesivir are in process, and results have started to come. Remedesivir has been approved by the FDA for emergency use after finding it to reduce the hospitalization stay of COVID-19 patients.

3.2.1.5. Umifenovir

Umifenovir (Arbidol, ABD) is a small indole derived molecule for the treatment of respiratory viral infections, influenza, and prophylaxis in Russia and China 90, 91. The action mechanism includes interrupting the interaction of S protein and ACE2 receptor to inhibit the fusion of the virus to the host cell membrane 92, Figure 5. ABD shows broad-spectrum antiviral activity by blocking the fusion of influenza A, B, and hepatitis C. The mesylate derivative of arbidol has been found to be 5 times more effective than arbidol in the treatment of SARS-CoV (in vitro) 93. A clinical trial data of 67 patients treated with arbidol showed less mortality and a higher discharge rate compared to untreated patients 94. However, further studies need to be conducted to reach any conclusion.

3.2.1.6. Nitric oxide

Nitric oxide (NO) is a gas produced by NO synthetase and arginine. Nitric oxide changes to peroxynitrite by reacting with superoxides, and inhibit the bactericidal and other cytotoxic reactions 95. NO is given to manage the airway function and also practiced as an antiviral agent to inhibits the replication of RNA and protein synthesis of the virus96, 97. The S-nitroso-N-acetyl penicillamine (NO-donor) significantly blocks the replication of SARS-CoV in a concentration-dependent manner 98. Thus, NO inhalation is being considered as another choice for the treatment of COVID-19.

3.2.1.7. Dexamethasone

Recently, it has been reported that corticosteroid dexamethasone reduces the mortality of COVID-19 patients by 30% 99, 100. The higher mortality rate is primarily due to the hyperimmune response stemming from the inflammatory cytokines storm. Dexamethasone is an FDA approved corticosteroid for immunosuppression, and 30 times more potent than cortisone. Although it inhibits the cytokine storm, also affects the T cells adaptability and B cells antibody-forming capability that could lead to persistent higher viral load even after patient appears recovered. The function of macrophages required for blood clearance may be severely affected. Thus, it should be carefully used only for critically intubated patients and not for already recovering patients. It could be beneficial to give the combination of corticosteroid with natural flavonoids like luteolin known to have antiviral properties via nebulization for targeted delivery to the lungs.

3.2.2. Protease inhibitors

3-chymotrypsin-like (3CL) protease, papain-like protease (PLP), and transmembrane serine protease (TMPRSS2) are the main proteases of coronavirus and responsible for the replication and inhibiting the host immune response 101. Serine protease is majorly responsible for S priming and uptake of the virus. Thus, targeting of these proteases has been sought as a promising approach in controlling the coronavirus.

Camostat mesylate (CM), an inhibitor of TMPRSS2, can block the spread and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, Figure 5. It is natively used to treat chronic pancreatitis in Japan. It prevents the uptake of SARS-CoV-2 by the ACE2 receptor. Currently, CM in phase 2 clinical trial in USA. Cinanserin is a serotonin receptor antagonist and a very old drug used to inhibit the 3CL protease and thus replication of SARS-CoV 30. The SARS-CoV-2 also found to produce 3CL protease; thus, cinanserin could be another choice in controlling the pandemic.

Flavonoids are the natural antioxidants and have several other medicinal effects, including antiviral activity. Flavonoids from Pterogyne nitens inhibit the infection of hepatitis C 102. The other flavonoids, such as herbacetin, pectolinarin, rhoifolin, and biflanoids have been tested for the inhibition of 3CL protease 103, 104 Quercetin 3-β-d-glucoside, herbacetin, and isobavachlcone have been found effective against the MERS-CoV. Diarylheptanoids (an extract from the bark of Alnus japonica) has shown to inhibit the PLP of SARS-CoV very effectively 105. Thus, the combination of cinanserin, flavonoids, and others could also be chosen as an alternative to fight against the SARS-CoV-2.

3.2.3. Biologics

The biologics have broadened the treatment options by leveraging the clinical practices during the SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV outbreaks. More than 500 patents have been filed featuring the antibodies, RNA, cytokines, vaccines, and other biologics 106.

3.2.3.1. Antibodies

The neutralizing antibodies are the most common biologics. The literature suggests that S protein of SARS-CoV-2 has been the target for the antibodies development due to its role in the fusion and uptake of the virus into the host cells 107 The site saturation mutagenesis, along with the human framework reassembly and DNA display technology, is being used to determine the complementary regions of potent humanized mouse antibodies with high affinities. The antibody (2978/10) with more than 80% neutrality has been selected, which specifically targets the fusion region of the S protein. Therefore, understating additional details about this region is critical for the development of efficient antibodies 108.

3.2.3.2. Cytokines

Low molecular weight biologics with immune-modulating properties can be generated to attack pathogens 106. Since ~40 years, different types of cytokines (composed of chemokines, interleukins, interferons, and lymphokines) have been recognized. Interferons are the most common ones to be used to regulate the viral load by restricting the replication. Interferon α and β have been studied for the coronaviruses, and interferon β has also shown positive effect against MERS-CoV 109. The combination with LPV/RTV and ribavirin can be expected to restrict the SARS-CoV-2 growth.

3.2.3.3. RNA Therapy

Complementary RNA neutralizes the mRNA and stop its expression. The interfering RNA is 21–25 nucleotide long small interfering (siRNA) or micro RNA. The short hairpin RNA (shRNA) can be the precursors of siRNA, which folds into the hairpin structure and block the target gene. The antisense RNA is single-stranded 19–23 nucleotides long, occurs naturally, or synthesized. The delivery of interfering RNA is usually performed using viruses, bacteria, or delivery vectors like plasmids, liposomes, etc. 110.

A patent (CN1648249) presents that dsRNA targets the M protein region of the mRNA from SARS-CoV. siRNA-M1 targets the 220–241 region of the M-mRNA, while siRNA-M2 targets the 460–480 region of the M-mRNA. The interference efficiency is more than 70%. The N and E region targeted siRNA can also inhibit the expression from GFP N and GFP E fusion proteins of SARS-CoV, respectively. The mutation at the 3’ end of siRNA increased the inhibition efficiency. The 6 siRNAs have also been proven to inhibit the replication by targeting the replicase 1A region of the SARS genome 111. SARSsi-4 found to be very efficient. There are also other siRNAs, e.g., SARSi-7, 8, 9, 10, and 11, which can target the S, M, N, and E region as disclosed by patent (US20050004063A1). The efficiency of SARSi-2, 3, 4, 7 – 11 has been tested in FRhk-4 cells and found to kill 50–90% of the virus.

The usage of RNA aptamers for SARS-CoV inhibition is also under an evaluation phase. RNA aptamers have a distinct affinity for SARS-CoV nucleocapsid and inhibit the unwinding of DNA double helix. Patent (JP2007043942) relates the development of ribozymes (RNA/DNA hybrid structure), which can recognize the conserved domain and loop region of the genes of coronavirus. It specifically recognizes the GUC having loop confirmation. Additionally, patent (US20050004063A1) relates that the antisense oligonucleotide has been tested to reduce the severity of the coronavirus. DNA/RNA antisense has been designed for disrupting the pseudoknots in the frameshift region of SARS-CoV. It might also be used to target the proteins involved in the inflammation.

3.2.3.3. Vaccine

Currently, there are about 115 vaccine projects running around the globe. Out of which 73 are in preclinical stages, and few of them have moved to clinical trials like mRNA-1273, Ad5-nCoV, INO-4800, pathogen-specific aAPC, etc., Table 2 (https://clinicaltrials.gov, Data accessed on May 18, 2020). Most of the vaccine development is in USA (46%), while the rest as following China (18%), Asia (except China) and Australia (18%), and Europe (18%) 6.

Table 2.

Current vaccines undergoing clinical trials of COVID-19

| Vaccine, Developer, Platform, and Stage of evaluation | Clinical trial information |

|---|---|

|

| |

| mRNA- 1273, Moderna/Lonza, RNA, and Phase I | https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04283461 |

| Ad5-nCoV, CanSino Bio, Non-Replicating Viral Vector, and Phase I | https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04341389 |

| ChAdOx nCoV-19, University of Oxford, NonReplicating Viral Vector and Phase I/II | https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04324606 |

| LV-SMENP-DC, ShenZhen Geno-Immune Medical Institute, Lentiviral, and Phase I/II | https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04276896 |

| BNT162 (a1, b1, b2, c2), (BioNTech, Fosun Pharma, Pfizer), RNA, and Phase I/II | https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04368728 |

| New COVID-19 vaccine, Sinovac Biotech, Chemically Inactivated SARS-CoV-2, and Phase I/II | https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04352608 |

| INO-4800, Inovio Pharmaceuticals, DNA, and Phase I/II | https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04336410 |

| bac TRL-Spike, Symvivo Corporation, DNA, and Phase I | https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04334980 |

| New COVID-19 vaccine, Beijing Institute of Biological Products, inactivated SARS-CoV-2, and Phase I | http://www.chictr.org.cn/showproien.aspx?proi=52227 |

| NVX-CoV2373, Novavax, Protein, and Phase I | https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03293498 |

| Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) Vaccine, Research Group Netherlands, Live Attenuated Virus, and Phase I/II | https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04362124 |

Vaccines are broadly classified into the following types: attenuated, vector-based, protein-based, mRNA based, and DNA based vaccines 112, Figure 6. Since the SARS-CoV-2 shares significant homology with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, analyzing the existing research could facilitate the development of vaccines for SARS-CoV-2. The safety of the vaccine is a very important factor along with its efficacy 106. Almost half of the vaccine development focussed based on the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of S protein. It was found that there was higher number of neutralizing bodies due to recombinant S protein subunit with only 2 folds less than produced by SARS-CoV-2 infection 113.

Figure 6.

Approaches followed in the development of live, viral vector, DNA, RNA, and protein-based vaccine for the SARS-CoV-2. Currently, most of the vaccines are in clinical phase. Adenovirus based vaccine (Ad5-nCoV) has been approved for the military usage, and RNA based vaccine (mRNA-1273) is gearing up for phase III clinical trial.

Attenuated virus:

After deleting the virulence determinant by reverse engineering, attenuated virus still remains the most robust and viable option for increasing immunity and wide cross-protection 114. There are approaches like restricting the virus replication in the upper respiratory tract only with limited copy numbers. For example, mutations (Y6398H) at Orf1a/b polyprotein inactivate (reduce the replication rate) the mouse coronavirus 106. However, in the face of pandemic, the large-scale production of attenuated virus in biosafety level 3 is a challenging task.

DNA vaccine:

The SARS antigen-specific CD8+ T cell response can be achieved with the help of chimeric nucleic acid, i.e., endoplasmic reticulum chaperone (e.g., calreticulin) linked to the antigen polypeptide of SARS-CoV 115. Gold nanoparticles or other delivery vectors can further improve delivery and the generation of humoral and T cell response specific to nucleocapsid of SARS-CoV. It was observed that titter of SARS significantly reduced in vaccinated animals. DNA coated gold nanoparticles inducted both the humoral and cellular immune response with the help of IgG, neutralizing antibodies, and increase in T cells response (CD3+ CD4+ and CD3+ CD8+) for the release of TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-2 116. Inovio Pharmaceutical announced that DNA vaccine (INO-4800) is ready for SARS-CoV-2 and human trials to be initiated soon117.

Protein vaccine:

GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) is developing a protein-based vaccine with the help of S protein and oil-based adjuvant. On the administration of soluble S protein (obtained from trimer-tag technology) along with GSK2 adjuvant produced high levels of neutralizing antibodies, and IgG2a and IgG2b antibody response in animal models 118. Patent (20070003577) relates the usage of full length recombinant trimeric spike protein of SARS-CoV for the generation of TriSpike vaccine. It showed the native immunogenicity comparable to the convalescent plasma of SARS patients. Also, a hybrid vaccine based on MHC II by Antigen Express in collaboration with Chinese consortium 119, which consist of i) an invariant chain, i.e., peptide enhancing the antigen presentation, ii) linker between the peptide and antigenic epitope, iii) an antigenic epitope for the MHC II molecule.

microRNA vaccine:

Moderna has filed a patent (WO2017070626) for the development of the mRNA vaccine by combining the multiple mRNAs of S, S1, and S2 proteins of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV into lipid nanoparticle formulation. This combination shows very high level of neutralizing antibodies in comparison to the mRNA encoded by S2 subunit. The viral load was reduced by 90% and the generation of the high amount of neutralizing bodies after its administration in New Zealand white rabbits. Moderna has announced mRNA-1273 vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 clinical trials 120. Currently, it has successfully completed the phase I and II clinical trials and now gearing up for the phase III clinical trials 121.

The precision vaccines help in inducing the specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTLs) without generating the antibody response 122. The clinical studies of SARS, MERS, and HIV have shown that the CTLs response protects patients from developing severe conditions due to hyper immune response. In the convalescent phase, the more severe response, the higher the level of antibody was recorded in plasma 123. Thus, the killing of infected cells with the help of CTLs in the absence of antibodies seems better options. The CTLs induced by vaccines might kill the virus before it starts the production. For example, CTLs should target the first polyprotein produced from the ORF lab of viral mRNA. The infected cell will process the polyprotein to peptides, and few of them will be presented on the surface of cells by human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I molecule, which could be recognized by CTLs. Hence, CTLs which are targeted to the replicase polyprotein will kill the infected cells even before it starts the synthesis of virus structural proteins 124 It has been reported that CTLs can be induced with 80% probability by protein binding to more than 3 HLA class I molecule, Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Role of precision vaccine in activating the T-lymphocytes. The peptide binds 3 FILA class I alleles can activate the CTLs with more than 80% probability.

Topical delivery of DNA using polyethyleneimine-mannose nanoparticles induce a potent CTLs response in mice, monkeys, and humans 125, 126. Thus, a similar approach could be applied against SARS-CoV-2 by inhaling the particles and directing the CTLs in the lungs 127.

3.2.4. Plasma therapy

In the lack of vaccines and drugs, convalescent therapy/immunoglobulin therapy remains the potential option of severe patients 128. The serum of recovered patients is used to treat the infected patients, as it contains the specific antibodies against the pathogen, which may clear the free virus as well as infected cells 129. Convalescent plasma therapy reduces the virus titer in the acute phase and expedites the recovery process with the potential of preventing the reinfection 130. The viral load in the blood is at the peak on the first week of infection, hence ideal for receiving convalescent plasma 131. The collection of plasma globulin from the recovered patients remains the viable option in the fight against the SARS-CoV-2; however, safety issues need further consideration. This therapy is more effective than the hormonal shock therapy used during the SARS and H1N1 pandemic 132.

3.2.5. Nutritional interventions

Vitamins also play major role in the immune system. The deficiency of nutritional requirements is one of the reasons for the impaired immune response against infection 133. For example, vitamin A plays a significant role in viral and bacterial infections 134–136. Low vitamin A renders calf more susceptive for the bovine coronavirus 137 Vitamin B functions as co-enzymes in many reactions 138. Vitamin B and UV light have significantly reduced the titer dosage of MERS-CoV 139. Additionally, vitamin B3 can also reduce the neutrophil infiltration to the lungs, thus the inflammation. Vitamin C has been also reported to protect against coronavirus 140. The chicken trachea organ culture demonstrates resistance to coronavirus after vitamin C supplement. It also helps in the production of histamines, which help in running noses, sneezing, swollen nodes, and other flu-like symptoms 141. Three clinical trials have shown the involvement of vitamin C in the prevention of pneumonia susceptibility 142. Vitamin D is also presumed to have a significant role in COVID-19. Vitamin D deficiency prone the calves to bovine coronavirus 143. In addition to these vitamins, mucroporin-M1, emodin, promazine, nicotinamide are also known to work against SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2.

4. Nanotheranostics Perspective

There has been number of nanotechnology inventions which were applied right from diagnosis, surgical and therapeutic interventions. Nanotechnology has emerged as a wonderful tool and technology to enhance the efficacy of existing therapeutic and imaging agents. A number of multifunctional nanoparticles have been developed and approved by the FDA for various indications, including cancer treatment. Bayer’s Aspirin™ is also a particle formulation for quick relief from pain. Now, there is a circumstance to tune already FDA approved formulation for tackling COVID-19. This section delineates the nanotechnological advancements and resources that can be used for the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of viral disease, and easily extrapolated for COVID-19.

4.1. Detection

Biosensors are an alternative to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and have been developed for several viral diseases 144. However, low sensitivity and specificity are a major concern. Nanotechnology plays an important role in biosensor(s) development. It facilitates the targeted sensing, multiple analytes detection, ability to mass transfer at short distances for fast response, etc.8. This leads to high sensitivity, selectivity, and accelerate the development of POC devices. Plasmonic nanoparticles, such as silver, gold, and other metal oxide nanoparticles, quantum dots and graphene have gained significant interest in the field of biosensors, Figure 8 9, 145.

Figure 8.

Role of inorganic, organic and hybrid nanomaterials in COVID-19 theranostic. The antibody and antigen functionalization of nanomaterials are the most common approach for the diagnostic purposes.

The intriguing optical property (surface plasmon resonance) of nanoparticles is being utilized to enhance electromagnetic radiative phenomenon (absorbance and scattering) in diagnosis. The localized surface plasmonic resonance (LSPR), surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS), quenching, and fluorescence properties are widely used in biosensor function. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) attached to the antibodies, biomolecules, proteins, aptamers, can enhance the LSPR and SERS signals, and the energy transfer between the fluorophore and AuNPs 9 146. Currently, there are number of nanomaterial-based biosensors available for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses, Table 3.

Table 3.

Nanomaterials based diagnostic tests available for SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses.

| Type | Target | Virus | Nanomaterial | Role | LOD | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Piezoelectric immunosensor | Antigen (sputum) | SARS-CoV | Piezoelectric crystal consisted of quartz wafer | Immobilization of polyclonal antibodies against SARS-CoV | 0.6 μg/mL | 153 |

| LSPCF | Nucleocapsid protein (serum) | SARS-CoV | Gold nanoparticles | Immobilization of fluorophore labeled anti-N-2 antibodies | 1 pg/mL | 154 |

| Optical immunosensor | Antigen (nucleocapsid protein) | SARS-CoV | Quantam dots | Immobilization of RNA aptamers | 0.1 pg/mL | 155 |

| Electrochemical immunosensor | Antigen | SARS-CoV-2 | Gold nanoparticles | Immobilization of mAbs | 90 fM | 156 |

| FET | Antigen | SARS- CoV-2 |

Graphene sheets | Immobilization of specific antibodies | 1.6 × 10^1 pfu/m L | 157 |

| PPT effect and LSPR | RNA | SARS-CoV-2 | Gold | Immobilization of DNA | 0.22 pM | 158 |

| Electrochemical immunosensor |

1-naphthol | Influenza | Pt/CeO2/GO composites |

Immobilization of antibodies and signal amplification | 0.43 pg/mL | 159 |

| Electrochemical immunosensor |

PB1-F2 protein |

Influenza A |

Polypyrrole matrix |

Immobilization of monomeric or oligomeric PB1-F2 specific antibodies | 0.42 nM | 160 |

| Nano-flow immunosensor |

Antigen | H1N1, H5N1, and H7N9 | ZnO nanorods gro wn inside PDMS channel | Immobilization of antibodies | 1 pg/ml | 161 |

| LSV | Antigen | H7N9 | AgNPs-G / AuNPs-G | AgNPs-G as trace labels/AuNPs-G for immobilization of H7- mAbs | 1.6 pg/mL | 162 |

| Electrochemical immunosensor |

Antigen | H7N9 | Bifunctional magnetic nanobeads | Separation and signal carriers. | 6.8 pg/mL. | 163 |

| Electrochemical immunosensor |

Antigen | H1N1 | RGO | Immobilization of mAbs | 0.5 pfu/mL | 164 |

| SPR | Surface antigen |

AIV | Gold nanoparticles | Immobilization of GBP / array chip | 1 pg/mL | 165 |

| Fluorescence immunoassay |

Antigen | AIV | Gold nanoparticles and QD | Labeling and fluorescence quenching | 0.09 ng/mL | 166 |

| Voltammetry | cDNA | AIV | MWNT, PPNWs, and gold nanoparticles | Immobilization of DNA aptamer | 0.43 pM | 167 |

| FRET | cDNA | AIV | Quantum dots | Immobilization of oligonucleotides | 0.27 nM | 168 |

Abbreviation: Graphene oxide and Pt nanoparticles functionalized CeO2 nanocomposites (Pt/CeO2/GO), silver nanoparticle-graphene-chitosan nanocomposite (AgNPs-G) /gold nanoparticle-graphene nanocomposites (AuNPs-G), localized surface plasmon coupled fluorescence (LSPCF), linear sweep voltammetry (LSV), reduced graphene oxide (RGO), plasmonic photothermal (PPT), localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR), fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), field-effect transistor (FET), gold binding polypeptides (GBP), multi-wall carbon nanotubes (MWNT), polypyrrole nanowires (PPNWs), avian influenza virus (AIV)

For example, AuNPs deposition on the indium tin oxide (ITO) coated glass slides capable of enhancing the detection of electron transfer signals from the HIV-1 virus-like particles (VLP) 147 This system detects HIV-1 at a concentration of 600 ngmL−1 to 375 pgmL−1. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are useful in increasing the intensity of electron transfer to the electrode surface. AgNPs are mostly exploited in the electrochemiluminescence (ECL) biosensors 145. Functionalization and immobilization of AgNPs provide enhancement to the ECL of the luminophores. Nanosilver substrate has been found very promising for the SERS, which helps in achieving reproducible signals in aqueous solutions 148. Moreover, the combination of Ag and Au has been used for the synthesis of bimetallic NPs for more efficient sensing applications 149.

Silicon nanowires are emerging as an ultrasensitive and label-free detection technique. Silicon nanowire-based transistors are able to detect even the single virus after modification with antibodies 150. On combining the air sampling with the microfluidics, it was noticed to detect even airborne influenza-like H3N2 viruses 151. A surface plasmon resonance biosensor (without label or enzyme amplification) can detect the HIV target DNA within a linear range of 1 pM to 150 nM and limit of detection (LOD) of 48 fM along with high accuracy and reproducibility. The time required for the test is ~ 60 min 152.

Nanozymes are the artificial enzyme comprised of nanomaterials that have similar efficiency and catalytic abilities as natural enzymes 169. For example, Fe3O4 nanoparticles exhibit intrinsic peroxidase activity, while many other nanomaterials have shown enzymatic activities such as catalase, oxidase, superoxide dismutase, and many others 170, 171. Nanozymes can also regulate the redox level of the cells, as the excess ROS causes oxidative stress and damages the cells 172. Nanozymes have been used for detecting viruses, such as HIV and Ebola. A BSA-Ag nanocluster formulation can enhance Hg2+ oxidase activity, which can produce superoxide anions for the 3,3,5,5-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) oxidation. This system was able to detect the 20 nmolL−1 of HIV DNA 173. Another nanozyme system was found to be 100 fold more sensitive and quick in the detection of Ebola 174 Together, it is viable that by combining different types of antibodies and probes, these diagnostic strips can be applied for different viruses.

4.2. Nanotherapeutics

4.2.1. Nanomedicine

The size and morphology of nanomaterials are comparative to the SARS-CoV-2, which can facilitate binding to the spike protein and help in the localized killing. There is an enormous demand for nanotherapeutics or nanomedicine (medicine in nanoparticles) for the treatment of various diseases. These nanoparticles can efficiently deliver earlier mentioned number of repurposing and other therapeutic agents. However, in this section, we focused two molecules, curcumin and niclosamide, how nanoformulations of these molecules can be improved for viral diseases, including SARS-CoV

Curcumin is a polyphenol compound obtained from Curcuma longa and extensively used as an anti-inflammatory agent 175, 176. Thus, the usage of curcumin seems promising for the COVID-19 driven severe lung inflammation. Inflammation is the result of immune response, overexpressed inflammation markers, and increase in lipid peroxide and free radicals 177. Curcumin efficiently interrupts various pathways, such as NF-κB, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), cyclin Dl, signal transducer, cyclooxygenase, and transcription activators 178, 179, Figure 9. It also suppresses the expression of interleukin 6 (IL-6) by inhibiting the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and NF-kB signaling pathway 180, 181.

Figure 9.

Anti-inflammatory action mechanism of curcumin. It follows diverse pathways to inhibit the inflammation. Adapted with permission from reference 179 [de Almeida Alvarenga, L., Leal, V. d. O., Borges, N. A., Silva de Aguiar, A., Faxen-Irving, G., Stenvinkel, P., Lindholm, B., and Mafra, D. (2018) Curcumin - A promising nutritional strategy for chronic kidney disease patients. Journal of Functional Foods 40, 715–721].

Curcumin inhibits the Epstein-Barr virus by blocking the inducers and suppresses the proliferation of Epstein-Barr virus transformed human B cells 182. It can obstruct the integrase 1 for preventing the HIV infection 183. Curcumin has been found effective for the treatment of various viral diseases such as chikungunya, hepatitis C, Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), flock house virus (FHV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV), and RSV 184, 185. It was observed that at 30 μM curcumin, the strains of HIN1, H6N1, and PR8 strains got inactivated, and at 30 μM conc., the infection was reduced due to HSV-1 and HSV-2 virions in the Vero cells 186. Also, it has been tested in silico for the treatment of Ebola 187 It also worked against the Zika virus in a dose and time-dependent manner 188.

Although curcumin has diverse medicinal properties, the low bioavailability limits its application. Various methods have been proposed to increase bioavailability, such as loading curcumin in polymer micelles, polymer nanoparticles, liposomes, metal complexes, and analogs as well as derivatives 189. There are several nanoformulations of curcumin have been prepared with the most common ones are poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid, poly(butyl cyanoacrylate), chitosan, solid lipid, and albumin nanoparticles 190. For example, the binding of curcumin with chitosan increases its bioavailability, biodistribution, chemical stability, and reduce systemic toxicity 191. Curcumin nanoformulations have been shown to have minimum inhibitory concentration ~1 mg/ml while the crude one had 350 mg/ml 192. It reflects the superior antipathogenic activity of curcumin when encapsulated in nanoparticles. The PEGylated lipid formulations of curcumin have been found to be 10 fold more effective for malaria than crude curcumin 193, 194 The composite nanofilms based on curcumin, chitosan, and silver nanoparticles or nanoclay have been reported to induce synergistic antibacterial effects 195, 196.

Niclosamide is an FDA approved anthelmintic drug developed for the treatment of tapeworms and nematodes. Currently, WHO listed it as one of the essential drugs 197 Niclosamide inhibits oxidative phosphorylation and stimulates the ATPase activity in the mitochondria and regulate the other pathways, such as Wnt/β catenin, STAT3, Notch, mTORC1, NF-kB, NS2B-NS3, and pH in treatment of bacterial and viral infections, cancers, and other metabolic diseases 198. Niclosamide inhibits the replication of SARS-CoV in less than 0.1 μM (EC50 value) along with cutting off the cytopathic effect at 1 μM 199. Its 2-chloro-4-nitroanilide derivative is a potent inhibitor of 3CL protease of SARS-CoV. Niclosamide found to be more effective at a concentration of 10 μM to MERS-CoV with 1000-fold reduction in replication by inhibiting S-phase kinase associate protein 2 (SKP2) through autophagy induction 200. This drug has also been tried for the treatment of flavivirus, hepatitis C, Ebola, rhinovirus, chikungunya, and human adenovirus, epstein-barr virus.

However, niclosamide is also not spared from demerits, such as unneglectable cytotoxicity, high hydrophobicity, low bioavailability, and absorption. To overcome these limitations, a number of strategies, such as chemical modification, prodrug, loading in drug carriers, have been implemented to improve the pharmacokinetic properties and to maximize the therapeutic versus side-effect ratio 201, 202. A nanocrystal suspension formulation of niclosamide (nebulizer, 1–5 μm droplet size) stabilized by the surfactant can deliver therapeutic load to the lungs 202. The pegylated nanoformulation has been proven to increase the hydrophilicity, half-life, enhance the bioavailability, and reduce the systemic toxicity 203. Other methods are encapsulation inside albumin, solid lipid and polymeric nanoparticles. Also, it has been conjugated with the chimeric polypeptide, which self-assemble to form the monodisperse nanoparticles and worked as a prodrug for various types of infection 204.

4.2.2. Inorganic nanoparticles

The commercial antiviral drugs for the influenza virus mainly target neuraminidase (NA) and matrix protein 2 (M2) ion channel 205. The M2 ion inhibitor blocks the transportation of H+ ions, thus the coating of the viral genome and prevents the replication. NA inhibitors prevent the release of virus from the cells by interrupting the hydrolysis of the terminal sialic acid residues. U.S. center for disease control (CDC) says that 99% of influenza virus’ strains show resistance to M2 inhibitors 206. The continuous mutations have changed the drug binding sites of the influenza virus, thus increased the infectivity and mortality rates 207, 208. Another target is hemagglutinin (HA) (involved in the fusion of the virus with the host cells) of influenza virus 209. Silver nanoparticles interfere with disulfide bonds of HA and block entry of the virus in host cells 210. Additionally, there have been many combinations of silver and gold nanoparticles, such as tannic acid, chitosan, PVP and curcumin modified silver, and gallic acid-modified gold nanoparticles for checking the infection of influenza virus 211–215. Porous gold nanoparticles provide extensive surface area and more efficiently binds the disulfide bonds 216 and stop the viral infection compared to conventional inorganic nanoparticles, Figure 10 217.

Figure 10.

Mechanism of action of porous gold nanoparticles to prevent the attachment of viruses on the cell surface. A. Virus interaction with host cells and internalization through cellular receptors with hemagglutinin. B. Prevention of cellular receptor and hemagglutinin binding via nanoparticles. The porous gold nanoparticles provide larger surface area for the breakage of disulphide bond. Adapted from reference217 [Meléndez-Villanueva, M. A.; Morán-Santibañez, K.; Martínez-Sanmiguel, J. J.; Rangel-López, R.; Garza-Navarro, M. A.; Rodríguez-Padilla, C.; Zarate-Triviño, D. G.; Trejo-Ávila, L. M., Virucidal Activity of Gold Nanoparticles Synthesized by Green Chemistry Using Garlic Extract. Viruses 2019, 11 (12)].

The other perspective is to develop the inanimate surface by spraying the antiviral nanoparticles. It will inactivate the virus even before it attacks the body. These nanoparticles can release active ingredients on the surface in a slow and controlled manner. Zinc oxide (ZnO), copper, silver, and other cationic nanomaterials being used for the development of self-cleanable cloths with broad antiviral activity 218, 219. There is a report that viral infection progress due to deficiency of zinc, thus being exposed to zinc due to nanocoating of inanimate surfaces might help another way 220.

There are established reports that SARS-CoV-2 spreads through the air droplets, and it comes out when someone talks, sneeze, or even breath heavily. In such conditions, the antiviral nanocoating on the mask can prevent such intermediate infection. Such coating approaches may desiccate the virions and reduce capillary condensation of water 221. These nanocoatings can become active on the exhalation, i.e., in the presence of warm and moisturized air but not in the cold and dried inhaled air. The implementation of nanocoatings can be widely applied without disrupting the supply chain of masks 222. These coatings are already in use to prevent molds, mildews, and other humidity problems in buildings 223.

4.2.3. Multifunctional nanotherapy

The long-life dosage regimen of antiretroviral therapy (ART) cause pill fatigue. Thus, there is a requirement of long-acting theranostic solutions. Nanomaterials act as contrast agents or contrast enhancers in imaging applications. Bismuth and sulfur-containing nanorods intrinsically radiolabeled with the luteium177 (177LuBSNRs) can render both antiviral therapy and multimodal imaging 224 The gold nanorods combined with the curcumin loaded poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid)-block-poly (ethylene glycol) (PLGA-b-PEG) copolymer are helpful for triggered and localized release of therapeutics along with photothermal capacity in one system 225. The albumin-Bi2S3 and magnetic nanoparticles can be developed for the combination of radiotherapy, magnetic hyperthermia, and chemotherapy. In comparison to non-targeted nanoparticles, the retention time of targeted nanoparticles increases to 3–6 folds 226. Several other inorganic, organic, and hybrid multifunctional nanoparticles can be applied for viral diseases, Table 4.

Table 4.

List of inorganic, organic, and hybrid nanomaterials used for the viral diseases theranostic.

| Nanomaterials | Virus | Therapeutic potential | Imaging potential |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Silver nanoparticles | HHV, HIV-1, RSV, MPXV, IV, TV, HBV, CoV | Affect attachment and block replication | SERS |

| Gold nanoparticles | IV, HSV-1, CSFV, HIV | Prevent attachment as well as penetration, PTT | CT, PAT, SERS |

| Copper oxide nanoparticles | HSV-1, HIV-1 | Degradation of genome and oxidation of proteins | PAT |

| Zinc oxide nanoparticles | H1N1, HSV | Inhibition after viral entry | Optical |

| Zirconia nanoparticles | H5N1 | Promote cytokines | Optical, MRI |

| Silicon nanoparticles | IV | Reduce number of progeny | Optical |

| Nano-carbon | HHV, IV | Inhibit entry of virus, PTT | SERS, Optical |

| Graphene oxide | HHV, HCV, RSV | inhibit attachment, PTT | SERS, Optical |

| Iron oxide nanoparticles | HCV | Magnetic hyperthermia | MRI |

| Dendrimers | HIV, HSV | Drug delivery system | Multimodal |

| Polymeric | HIV, IV | Drug delivery system | Multimodal |

| Biological nanoparticles | IV | Antigenic presentation, Drug delivery system | Multimodal |

| Liposomes | HCV, IV, HIV | Antigenic presentation, Drug delivery system | Multimodal |

Abbreviation: Human herpesvirus (HHV), human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), monkeypox virus (MPXV), influenza virus (IV), Tacaribe virus (TV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), coronavirus (CV), swine fever virus (CSFV), human papillomavirus (HPV), herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), adenovirus (Adv), herpes simplex virus (HSV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), avian influenza virus subtype (H5N1), surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS), computed tomography (CT), photoacoustic tomography (PAT), single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), photothermal therapy (PTT)

4.2.4. Nano vaccine

The majority of the vaccines help in generating the antibodies for neutralizing the pathogen; however, recent findings show that activation of both humoral and cellular immune response is necessary to control diseases, like HIV, hepatitis C, and many others 227–229. Virus-like nanoparticles (VLPs) balances the safety and immunogenicity of the vaccine. VLPs are non-infectious and at the same time carrying similar protein composition of the virus. Most of the VLPs don’t have nucleic acid; some have but don’t allow it to be replicated in mammals. Currently, hepatitis B & E, and human papillomavirus vaccines are based on VLPs 230. These vaccines require the adjuvants to get completely effective. The VLPs size ranges from 20 – 300 nm, which can be efficiently recognized by the dendritic or other antigen-presenting cells 231, 232. VLPs also help in generating the innate immune response with the help of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), lead to the generation of type I interferon (IFN-I), better cross-presentation capacity and cell-mediated T lymphocyte response 233–235. Further, VLPs have been studied to induce the cellular immune response, wherein antigen containing VLPs was presented by APCs to activate the pathogen-specific CD8+ T cells through Tap-proteasome independent pathway 236–238. VLPs are safer than conventional vaccines and can be injected into immunocompromised individuals 239. There are number of VLPs that have been developed for several viral infections, Table 5.

Table 5.

Clinical trials of VLPs for respiratory viruses

| Source | Component | Expression system | Protective immunity | Age group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| H1N1, H5N1 240 |

HA+NA+M1 | E. coli | Neutralizing antibody with 79% seroprotection rate | 18–64 |

| H5N1241 | HA+NA+M1 | E. coli | Seroconversion: HAI based- 61% MN based- 76% | 18–40 |

| H7N9 242, 243 | HA VLP + ISCOMATRIX | E. coli | Neutralizing antibody against both homologous and heterologous strains (H7-A/Netherlands/219/03 strain) | ≥18 |

| H1N1244 | gH1-Qbeta/alhydrogel | E. coli | Seroconverison- Adjuvant group: 65.4%; Non-adjuvant: 65.4 | 21–64 |

| H5N1245, 246 | HA | Nicotiana benthamiana | Hemagglutination inhibition with virus microneutralization | 18–60 |

| RSV-A2247, 248 | RSV F | Sf9 insect cell | Neutralizing antibodies | >55 & healthy women |

Abbreviation: Swine-origin influenza A (H1N1), Avian influenza A subtype (H7N9), hemagglutinin (HA), neuraminidase (NA), matrix (M1), Globular head domain of hemagglutinin (gH1)

The Novovax patent (US20160206729A1) discloses VLPs containing at least one trimer of S protein of MERS-CoV induced the high level of neutralizing antibodies in conjugation to proprietary adjuvant Matrix M in mice and cattle. These VLPs were proven to promote protection against the MERS-CoV. Recently, Novovax has announced to be working with SARS-CoV-2 using patented recombinant technology and proprietary adjuvant.

4.2.5. Nanosponges

Nanosponge category of nanoparticles is a new generation drug delivery system 249 and act as virus filter(s). The unique structure and core of nanosponges can separate viruses. The exterior cross-connected structure with cavities (250–1 μm width) of nanosponge similar to RBCs can also release drugs at the site in a controlled manner 250–253. Nanosponges can also act as depots for soaking up the toxins. For example, on the injection of nanosponges, bacteria, and other pathogens attack to it being similar to the RBCs. Once these depots are saturated with toxins, go to the liver, and filter out content 253. Nanosponges have been used for the treatment of viral diseases like influenza, rhinovirus, RSV, HIV, and HSV 254–256. Such systems with antivirals effectively inactivate and kill the viruses in nasal epithelial and lungs 257.

4.2.5. Autophagy Modulation

Autophagy has got significant attention from the past decade since the outbreak of SARS in 2002. There are number of evidence suggesting the involvement of endocytic pathways in facilitating the entry of coronaviruses like SARS-CoV, Mers-CoV via two critical steps, i.e., i) clathrin-dependent endocytosis, and ii) cathepsin mediated S protein cleavage 258. It has also been experienced that enhancing the autophagy of viral proteins heightened adaptive immunity due to increase in antigen priming 259. Also, the role of autophagy has been established substantially in the regulation of inflammatory cytokines. Thus, the autophagy modulating drugs in combination with antivirals might be another breakthrough in handling the COVID-19 crisis. Further, a recent study also suggests that out of two synonymous mutations in SARS-CoV-2, non-structural protein 6 (NSP6) mutation could lead to significant change in the pathogenicity and intracellular survival of the SARS-CoV-2 due to its involvement in the autophagic lysosomal machinery 260. Thus, there is also a need to monitor this mutation and leverage the opportunity.

Also, number of evidence shows that nanomaterials can be tuned accordingly to modulate the endocytic pathway towards the treatment and control of diseases like cancer and other neurodegenerative disorders, wherein the removal of protein aggregates and damaged cellular components is critical 261. It’s indicated that nanomaterials cause disturbances in the signaling pathways, lysosome destruction, oxidative stress, etc., which modulates the autophagy driven suicide of the cells. However, there are also reports wherein nanomaterials enhanced the survival of the cells. Further research is needed in this direction to discover the exact underlying mechanism to harness the potential of nanomaterials in autophagy modulation.

5. Conclusion and Future Directions

The COVID-19 has caused the havoc worldwide with trillions of dollars of losses and millions of deaths. There is an urgent need to find an effective solution to control the pandemic. It has boosted R&D worldwide. High-resolution structure of 3CL protease and 3D structure of spike glycoprotein from SARS-CoV-2 have provided better understanding about the viral replication and pathogenesis, respectively. X-ray crystallographic studies of spike protein reveal that it has some ridges which are compact than the SARS-CoV, and responsible for adaptive and tighter binding to human ACE2 receptors. These advanced outcomes facilitate the development of vaccines and antivirals by correlating mutations. There are many reports wherein the therapeutic candidates show promising in vitro studies, while shows inefficacy or even cause fatal syndromes during in vivo studies and clinical trials. Consequently, more insights may be required for determining the effective binding pockets and finding clear cut medicines. So, for the safer side better to adopt broad-spectrum drugs and follow required precautions. It is also advised to look at the nanotechnological approaches for the improved theranostic deployable solution. In the past decades, there has been tremendous research on nanotechnology for increasing the efficacy of the therapeutics for various indications, which can be extended to COVID-19.

Acknowledgments

The study was partially supported by the National Institute of Health of United States of America (R01 CA210192, R01 CA206069, R01 CA204552), Faculty Start up fund from UTRGV (to M.M.Y., M.J., and S.C.C.), and Herb Kosten Foundation. This work is also supported by IIT Bombay Healthcare Initiative.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Chen Z; Zhang W; Lu Y; Guo C; Guo Z; Liao C; Zhang X; Zhang Y; Han X; Li Q; Lipkin WI; Lu J, From SARS-CoV to Wuhan 2019-nCoV Outbreak: Similarity of Early Epidemic and Prediction of Future Trends. bioRxiv 2020, 2020.01.24.919241. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stephenson J, Coronavirus Outbreak—an Evolving Global Health Emergency. https://iamanetwork.com/channels/health-forum/fullarticle/2760671, JAMA Network: 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rochmyaningsih D, Indonesia finally reports two coronavirus cases. Scientists worry it has many more. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/03/indonesia-finally-reports-two-coronavirus-cases-scientists-worry-it-has-many-more, Science 2020.

- 4.Dehelean CA; Lazureanu V; Coricovac D; Mioc M; Oancea R; Marcovici I; Pinzaru I; Soica C; Tsatsakis AM; Cretu O, SARS-CoV-2: Repurposed Drugs and Novel Therapeutic Approaches-Insights into Chemical Structure-Biological Activity and Toxicological Screening. Journal of clinical medicine 2020, 9 (7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ulm JW; Nelson SF, COVID-19 drug repurposing: Summary statistics on current clinical trials and promising untested candidates. Transboundary and emerging diseases 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thanh Le T; Andreadakis Z; Kumar A; Gomez Roman R; Tollefsen S; Saville M; Mayhew S, The COVID-19 vaccine development landscape. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2020, 19 (5), 305–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farzin L; Shamsipur M; Samandari L; Sheibani S, Advances in the design of nanomaterial-based electrochemical affinity and enzymatic biosensors for metabolic biomarkers: A review. Mikrochimica acta 2018, 185 (5), 276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma J; Wang J; Wang M; Zhang G; Peng W; Li Y; Fan X; Zhang F, Preparation of Cuprous Oxide Mesoporous Spheres with Different Pore Sizes for Non-Enzymatic Glucose Detection. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2018, 8 (2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JH; Cho HY; Choi HK; Lee JY; Choi JW, Application of Gold Nanoparticle to Plasmonic Biosensors. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19 (7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parhizkar M; Mahalingam S; Homer-Vanniasinkam S; Edirisinghe M, Latest developments in innovative manufacturing to combine nanotechnology with healthcare. 2018, 13 (1), 5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]