Abstract

Background:

Maternal blood total mercury (THg) is a biomarker for prenatal methylmercury (MeHg) exposure. Few studies have quantified both blood THg and MeHg during pregnancy, and few studies have reported longitudinal trends.

Objectives:

We analyzed blood THg and MeHg in a cohort of pregnant mothers in Charleston, South Carolina (n=83), and investigated whether blood THg or MeHg changed between early and late gestation.

Methods:

THg and MeHg were analyzed in blood samples from early (12 ± 1.7 weeks) and late (35 ± 2.2 weeks) gestation.

Results:

Blood %MeHg (of THg) averaged 63% (range: 10–114%) and 61% (range: 12–117%) during early and late gestation, respectively. In unadjusted analyses, blood MeHg decreased from early to late pregnancy (paired t-test, p=0.04), while THg did not change (paired t-test, p=0.34). When blood MeHg was normalized by the hematocrit, this decrease was no longer statistically significant (paired t-test, p=0.09).

Conclusions:

In unadjusted analyses, blood MeHg, but not THg, decreased significantly between early and late gestation; this decrease was due in part to hemodilution. Percent MeHg (of THg) varied by up to one order of magnitude. Results highlight the importance of Hg speciation in maternal blood samples to assess prenatal MeHg exposure.

Keywords: methylmercury, prenatal, speciation, hemodilution

1. INTRODUCTION

Mercury (Hg) is a global pollutant and potent neurotoxin, which poses a threat to human health.1 Methylmercury (MeHg) is one of the most toxic Hg species, which has the ability to cross the placenta and the blood-brain barriers.2 Maternal blood total Hg (THg) is a biomarker for fetal MeHg exposure;3 however, blood THg reflects exposure to both MeHg and inorganic Hg.4 Fish tissue is the main dietary source of MeHg, while dental amalgams are an important exposure source of inorganic Hg.2 Hg from dental amalgams is lower compared to fish tissue Hg.2

Blood THg is estimated to be >90% MeHg (of THg).2 However this value was based on ingestion of MeHg-poisoned bread in Iraq between 1971–1972.1 For those studies that measured both blood THg and MeHg (or inorganic Hg) in populations with low-level MeHg exposure, the average proportion of MeHg was <90%, and the range was wide (Table 1).5–10 Percent MeHg (of THg) averaged 57% among 150 children in Lisbon, Portugal,5 who participated in a randomized clinical trial involving dental amalgam restoration.6 In Greenville, South Carolina, USA, %MeHg (of THg) in cord blood among seven mothers averaged 69% (range: 25–124%, n=7 mothers); average hair THg concentrations were low, suggesting low fish consumption.7 Within a cohort of 148 Swedish pregnant women, of whom a majority (95%) ingested some fish, blood %MeHg (of THg) averaged 72% (range for 90% of samples: 22–95%).8 Among 263 pregnant women in Baltimore, Maryland, USA, cord blood %MeHg (of THg) averaged 74.6% (95% confidence interval: 71.2%, 78.1%).9 Among 400 Korean adults, who were frequent fish consumers, blood %MeHg (of THg) averaged 79% (range: 77–80%).10 In addition to differences in dental amalgams and dietary Hg sources, variability in %MeHg (of THg) may reflect local exposure sources, as well as metabolism of Hg.2

Table 1.

Studies reporting percent methylmercury (of total mercury) in maternal blood or cord blood.

| Reference | Location | N | Matrix | THg (μg/L) Mean ± 1 SD (range) | MeHg (μg/L) Mean ± 1 SD (range) | IHg Mean ± 1 SD (range) | %MeHg (of THg) Mean ± 1 SD (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study | Charleston, South Carolina, USA | 83 | Early gestation, Maternal blood | 0.87 ± 0.79 (0.02–3.9) | 0.58 ± 0.61 (0.01–2.7) | 0.30 ± 0.331 (0–2.0) | 63 ± 24 (10–114) |

| This study | Charleston, South Carolina, USA | 83 | Late gestation, Maternal blood | 0.79 ± 0.75 (0.06–4.0) | 0.46 ± 0.41 (0.01–2.1) | 0.33 ± 0.411 (0–2.1) | 61 ± 22 (12–117) |

| 5-6 | Lisbon, Portugal | 150 | Maternal blood | 4.82 ± 2.31 (1.03–12.0) | 2.73 ± 1.52 (0.47–9.12) | 4.82 ± 2.311 (1.03–12.0) | 56.62 |

| 7 | Greenville, South Carolina, USA | 7 | Cord blood | 0.34 (BDL-0.67) | 0.23 (0.061–0.73) | 69 (25–124) | |

| 8 | Sweden | 148 | Early gestation, Maternal blood | 0.943 (<BDL-6.8) | 0.373 (<BDL-4.2) | 72 (22–95)4 | |

| 8 | Sweden | 112 | Late gestation, Maternal blood | 0.733 (<BDL-2.8) | 0.323 (<BDL–1.9) | Not given | |

| 9 | Korea | 400 | Maternal blood | 5.275 (5.00–5.57) | 4.055 (3.81–4.32) | 78.535 (77.09–79.97) | |

| 10 | Baltimore, Maryland, USA | 263 | Cord blood | 1.77 (1.58–1.97)6 | 1.45 (1.26–1.65)6 | 0.43 (0.38–0.48)6 | 74.6 (71.2–78.1)6 |

IHg (inorganic mercury), MeHg (methylmercury), SD (standard deviation), THg (total mercury)

IHg (estimated) = THg-MeHg

Range not given

Median

Range for 90% of the samples

Geometric mean

95% confidence interval

Important trends regarding public health may be missed if blood MeHg is not analyzed. For example, in Baltimore, MD (n=263), in adjusted models, increasing cord blood MeHg was associated with significantly higher systolic blood pressure among pregnant mothers, whereas associations were non-significant and trends differed for cord blood inorganic Hg (decreasing trend) and cord blood THg (increasing trend).9

We recruited pregnant mothers in Charleston, South Carolina, and investigated whether blood THg, MeHg, and inorganic Hg (=THg-MeHg) differed between early and late gestation. Few studies have reported longitudinal trends in prenatal MeHg exposure; however, changes in metabolism during pregnancy11 may influence prenatal MeHg exposure.7 We also assessed whether blood THg, MeHg, or inorganic Hg was associated with seafood consumption or maternal characteristics, such as race/ethnicity, education level, and maternal age.

2. METHODS

2.1. Enrollment and biomarker collection

Mothers were recruited at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, South Carolina, a coastal city. A majority of mothers were enrolled in a double-blind vitamin D supplementation study, while seven mothers were enrolled in an observational study concerning Hg metabolism. Eligible mothers were in good general health, between 18–45 years old, expecting a singleton birth, and within 14 weeks of the last menstrual period. Mothers provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. Protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Medical University of South Carolina and approved by cooperative review at the University of South Carolina. The vitamin D supplementation study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01932788).

Whole blood samples for Hg analyses were collected from mothers at 12 ± 1.7 weeks gestation (range: 8.2–17 weeks) and 35 ± 2.2 weeks gestation (range: 28–38 weeks) (Becton Dickinson, K2EDTA, Royal Blue). Vials were frozen at −20°C, and transported to the University of South Carolina Mercury Lab in a Credo Cube (−20°C) (20M, Pelican, MN, USA). Details on Hg analyses are in section 2.4.

After collection of the first blood sample, participants in the vitamin D supplementation study were randomized into placebo (400 IU) or supplemented (4400 IU) groups. No associations were observed between vitamin D supplementation status and maternal blood THg or blood MeHg (Wilcoxon rank-sum, p=0.66–0.83, n=83), indicating it was possible to pool mothers together for this analysis.

From October 2014 to March 2016, a total of 149 mothers were enrolled, including 83 mothers (56%), who donated blood samples during early and late gestation. In a post-hoc power analysis, a sample size of 83 provided 0.77 power to detect differences in blood MeHg between early/late gestation using a two-tailed paired t-test. There were no differences in age, ethnicity, or blood MeHg (early gestation only) between mothers who donated just one blood sample compared to those who donated two blood samples (Wilcoxon rank-sum or chi-squared test, p=0.22–0.84, n=142–149).

2.2. Food Frequency Questionnaire

During their second trimester, mothers completed at home the Block Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ),12 which was previously utilized in this population.13 The FFQ included five questions pertaining to seafood consumption, including “oysters,” “shellfish like shrimp, scallops, crabs,” “tuna, tuna salad, tuna casserole,” “fried fish or fish sandwich,” and “other fish, not fried.” For each type of food, there were nine possible responses, ranging from “never” to “every day,” which were converted to servings per day: 0=never or a few times per year, 1/30.5=once per month, 2.5/30.5=two to three times per month, 1/7=once per week, 2/7=twice per week, 3.5/7=three to four times per week, 5.5/7=five to six times per week, and 1=every day. Daily servings of each seafood were summed, providing total seafood intake. Proportional intake of oysters, shellfish, fried fish, other fish, and tuna was also determined. Dietary exposure to MeHg may also occur through rice ingestion.14–16 The FFQ included one question regarding rice ingestion, and servings per day were calculated as described above.

2.3. Other covariates

We considered the covariates listed below, which were associated with blood Hg in other studies,9,17–22 Mothers completed a sociodemographic questionnaire, including race/ethnicity, maternal age, education level, parity, and alcohol and tobacco use before and during their pregnancy. Height and weight were recorded at the first visit, and weight was recorded at subsequent visits. First trimester body mass index (BMI) was calculated, including underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (≥30.0 kg/m2). Gestational weight gain was classified as below, within, or above recommended weight gain based on guidelines from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Academies.23 Antibiotic treatment between the first and second blood draw was obtained from the medical record (range: 0–7 times), and categorized (0 times, 1 time, ≥2 times). Mothers reported whether they received the flu vaccine and the date of the vaccine.

2.4. Hg analyses

Blood THg was analyzed using the cold digestion method, following U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Method 1631.24–25 Approximately 0.5 g of thawed blood was aliquotted into a 40 mL borosilicate vial with a Teflon-lined cap. Blood was digested in 4 mL of hydrochloric acid and 1 mL of nitric acid overnight at room temperature. Then 1% 0.2N bromine monochloride (BrCl) solution was added at least 12 hours prior to analysis to oxidize all Hg to Hg(II). To neutralize BrCl, 0.1 mL of 30% hydroxylamine hydrochloride was added, followed by 0.1 mL of tin (II) chloride to reduce Hg(II) to volatile Hg(0). De-foaming agent (Spectrum brand Antifoam AF) (2% v/v, 1 mL) was added to analysis vials to reduce foaming. THg concentrations were quantified using cold vapor atomic fluorescence spectrometry (CVAFS) (MERX-T with Model III Detector, Brooks Rand Instruments, Seattle, WA).

Blood MeHg was analyzed using methods from Liang et al.5 Approximately 0.5 g of thawed blood was weighed into a 50 mL polypropylene tube, and dried in an oven overnight at 70°C. Samples were digested in 2 mL of 25% potassium hydroxide:methanol (w/v) for 3 hours at 75°C. Then 10 mL of dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) and 2 mL of hydrochloric acid were added to each sample. Samples were shaken for 30 minutes, then left overnight to complete phase separation. Approximately 8 mL of the CH2Cl2 layer was transferred to a pre-weighed 50-mL polypropylene tube, and double-distilled H2O (>18.0 MΩ cm−1) was added to 30 mL. Vials were heated in a water bath (60–70°C) for 1.5 hours to evaporate the CH2Cl2 layer, and then the volume was raised to 40 ml using double-distilled H2O. MeHg was quantified using gas chromatography (GC)-CVAFS, including ethylation with sodium tetraethylborate, following U.S. EPA Method 163026 (Model-III Detector, Brooks Rand Instruments, Seattle, WA).

Results for quality assurance/quality control are summarized in Table S1. Calibration curves were generated daily with a minimum of five standard points, and r-squared ≥0.99. For THg, average percent recoveries for four standard reference materials (n=34) and matrix spikes (n=30) ranged from and 93–108%. For MeHg, average percent recoveries for three standard reference materials (n=66) and matrix spikes (n=43) ranged from 81–118%. The average relative standard deviation (100 × standard deviation/mean) between sample replicates was 3.3% for THg (n=33) and 12% for MeHg (n=50).

Method detection levels were determined using two EPA methods.27 Using 3 × standard deviation of blanks, the method detection levels were 0.001 μg/L and 0.0001 μg/L for blood THg and MeHg, respectively (THg, n=14 blanks, MeHg, n=19 blanks). Alternatively, dividing the lowest point on the calibration curve by the average mass of blood analyzed (0.5 g), the method detection levels were 0.01 μg/L and 0.002 μg/L for THg and MeHg, respectively. All THg and MeHg values exceeded the method detection levels, regardless of the method used to derive these levels.

Seventeen observations out of 166 values (10%) had %MeHg (of THg) >100%, which was due in part to analytical variability, as noted above. Our lab and others have reported >100%MeHg (of THg).7,16,28 We retained 12 observations ≤117%MeHg (of THg) (Table 1). For five observations >125%MeHg (of THg), MeHg concentrations were imputed using multiple imputation based on the multivariate normal distribution,29 conditional on maternal blood THg, the hematocrit, weekly servings of seafood (for mothers that completed the FFQ), and maternal characteristics listed in Table 2. We imputed blood MeHg rather than blood THg because the relative standard deviation for MeHg was higher (12%) compared to THg (3.3%) (Table S1). Data were analyzed with and without imputed observations as a sensitivity analysis, and no differences in our results were observed.

Table 2.

Maternal characteristics (n=83 mothers).

| Mean ± 1 SD (range) or n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30 ± 5.4 (18, 42) |

| First trimester BMI (kg/m2) | 29 ± 8.2 (17, 60) |

| Weight change (kg)1 | 9.7 ± 5.6 (−7.7, 23) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| African American | 32 (39) |

| Caucasian | 31 (37) |

| Hispanic | 20 (24) |

| Education | |

| ≤ High school | 35 (42) |

| College (some or completed) | 31 (37) |

| Graduate school | 17 (20) |

| Parity | |

| 0 | 28 (34) |

| 1 | 25 (30) |

| ≥2 (range: 2–5) | 30 (36) |

| BMI class1 | |

| Underweight or normal weight | 29 (35) |

| Overweight | 24 (29) |

| Obese | 29 (35) |

| IOM weight gain guidelines1 | |

| Below | 22 (27) |

| Within | 34 (42) |

| Above | 25 (31) |

| Antibiotic treatment between first/second blood draws | |

| 0 times | 54 (65) |

| 1 time | 16 (19) |

| ≥2 times (range: 2–7) | 13 (16) |

| Flu vaccine | |

| No | 59 (71) |

| Yes | 22 (27) |

| Uncertain | 2 (2) |

| Did you drink alcohol prior to this pregnancy? | |

| No | 37 (45) |

| Yes | 46 (55) |

| Alcohol consumption during pregnancy | |

| No | 82 (99) |

| Yes | 1 (1) |

| Were you ever a smoker? | |

| No | 65 (78) |

| Yes | 18 (22) |

| Smoking during pregnancy | |

| No | 81 (98) |

| Yes | 2 (2) |

BMI (body mass index), IOM (Institute of Medicine), n (sample size), SD (standard deviation)

Sample size: BMI (n=82), BMI categorical (n=82), Weight change (n=81), IOM (n=81)

Blood inorganic Hg was estimated by subtraction (=THg-MeHg).5 For 12 observations >100%MeHg (of THg), a value of 0 was imputed for inorganic Hg. Prior to the log-transformation, 0.01 μg/L was added to all inorganic Hg concentrations so that observations=0 were not dropped from the data set.

Blood THg and MeHg were analyzed at the University of South Carolina Mercury Lab.

2.5. Hematocrit

The hematocrit (%) is part of the Complete Blood Count, and is defined as the ratio between the volume of red blood cells over the total volume of blood. Data for the hematocrit was abstracted from the medical record. About 80% of blood MeHg binds to red blood cells, while inorganic Hg is more evenly distributed between blood cells and plasma.1 Plasma volume increases from early to late pregnancy,30 and may contribute to a dilution effect for blood MeHg.8 To investigate the effect of hemodilution, blood THg, MeHg and inorganic Hg were normalized using an equation previously used for blood lead (100 × blood Hg/hematocrit).31 On average the Complete Blood Count occurred 2.4 weeks before the first blood draw for Hg, and 2.1 weeks later than the second blood draw for Hg (median=4 weeks for both).

2.6. Statistical analyses

Differences in blood Hg between early and late pregnancy were determined using 2-tailed paired t-tests. Bivariate associations between continuous variables were examined using Spearman’s correlation. Wilcoxon rank-sum test or Kruskal-Wallis test was used for comparison between continuous and categorical variables. To determine associations between two categorical variables, a chi-squared statistic with Fisher’s exact test was used.

The SAS Proc Mixed procedure for repeated measures was used to model blood Hg by calculating maximum likelihood estimates for covariates as fixed effects using an autoregressive covariance matrix. Diagnostics for model fit included comparison of the Bayesian Information Criterion, examination of Cook’s distance, and examination of residual plots to ensure assumptions for residuals were met (no evidence of non-linearity, constant variance, and normal distribution). Separate models were fit for blood MeHg, blood THg, and inorganic Hg. To adjust for positive skew and normalize the residuals, blood MeHg, THg, and inorganic Hg were log10 transformed. The variable for “time” (early pregnancy, late pregnancy) was forced into the model to examine the primary study question of whether blood Hg changed over the course of the pregnancy, after controlling for other covariates. Hematocrit was included in the model to adjust for hemodilution effects, and vitamin D supplementation status was included because most mothers were enrolled in the vitamin D study (section 2.1). Additional variables were assessed for inclusion in the model one at a time via forward selection, and were retained in the model if the variable was statistically significant (p≤0.05), or inclusion of the variable modified the beta coefficient for time by ≥10%, or by prior association with MeHg exposure (e.g., maternal age). Type III sums of squares were used to evaluate the statistical significance of all variables. In instances of multicollinearity, the variable that was most predictive of blood Hg remained in the model.

An alpha-level of 0.05 was used as a guide for statistical significance for all analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (Version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), Stata (Version 9.2, College Station, TX, USA), and the R-platform.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study population

Maternal characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Education level varied significantly by ethnicity (Fisher’s exact test, p<0.001, n=83), including a higher percentage of Caucasian mothers (94%) educated at the college or graduate school level, compared to African American (47%) and Hispanic mothers (13%). A total of 64% of women were overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m2). Only one mother was underweight (BMI<18.5 kg/m2), and henceforth, underweight and normal weight mothers were combined. BMI differed significantly by race/ethnicity (Kruskal-Wallis, p<0.001, n=82), including higher average BMI for African American mothers (34 kg/m2) compared to Caucasian and Hispanic mothers (26 kg/m2 for both).

3.2. Blood Hg

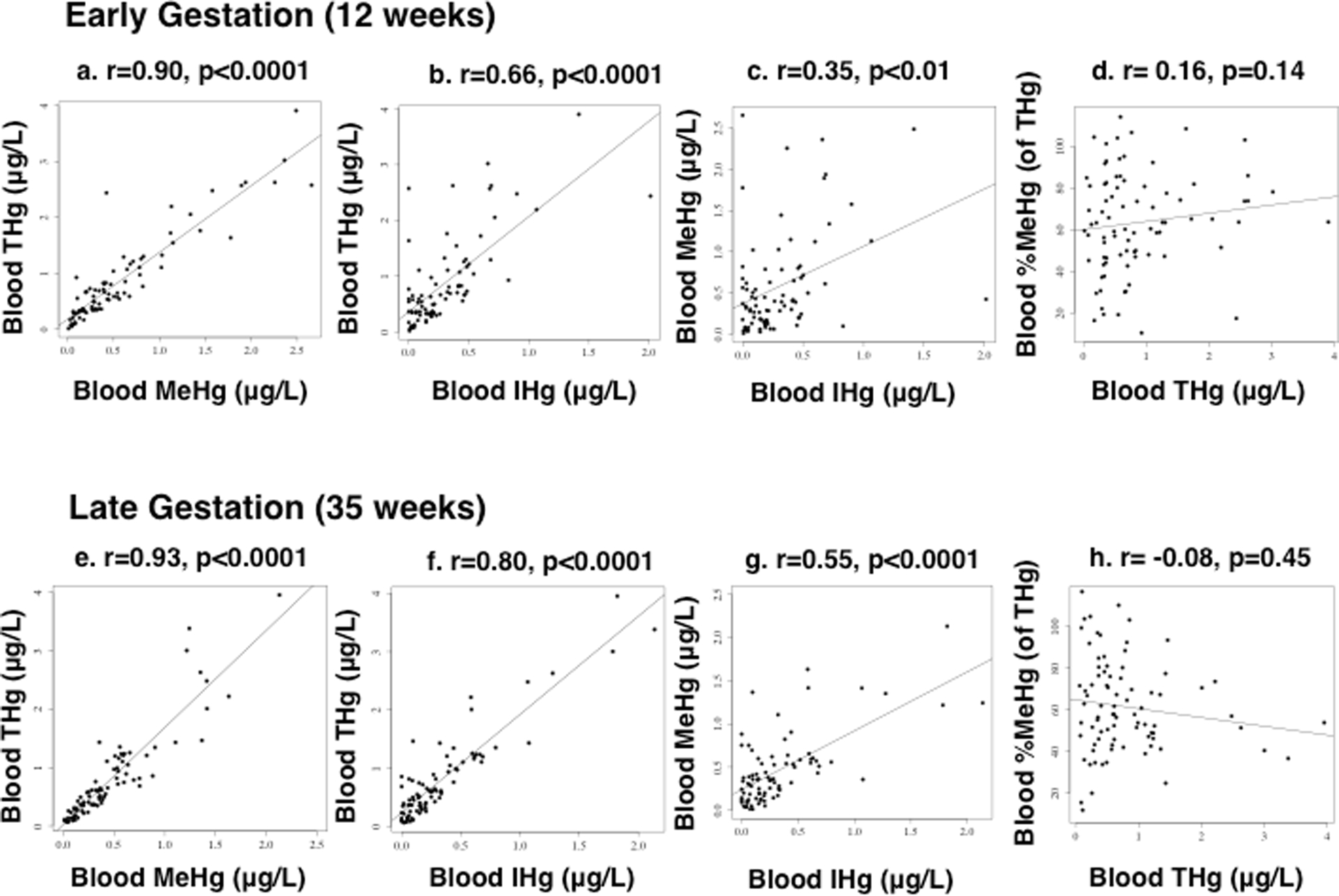

Descriptive statistics for maternal blood Hg are summarized in Tables 1 and S2. Blood THg, MeHg, and inorganic Hg were significantly correlated in both early and late pregnancy, including THg versus MeHg [Spearman’s rho: (0.90, 0.93), p<0.0001, n=83], THg versus inorganic Hg [Spearman’s rho: (0.66, 0.80), p<0.0001, n=83], and MeHg versus inorganic Hg [Spearman’s rho: (0.35, 0.55), p<0.01, n=83] (Figures 1a–c, e–g). Conversely, %MeHg (of THg) was not correlated with THg during early or late gestation (Spearman’s rho: (−0.08, 0.16), p=(0.14–0.45), n=83) (Figures 1d, h).

Figure 1.

Bivariate scatterplots relating (non-transformed) maternal blood mercury during early (12 ± 1.7 weeks) (figures a–d) and late (35 ± 2.0 weeks) gestation (figures e–h), including: (a, e) total mercury (THg) versus methylmercury (MeHg), (b, f) THg versus inorganic mercury (IHg), (c, g) MeHg versus IHg, and (d, h) %MeHg (of THg) versus THg (n=83 mothers). Spearman’s rho (r) and p-values are reported.

The reference dose for blood THg is based on cord blood (5.8 μg/L),2 and the estimated corresponding dose for maternal blood is 3.5 μg/L.32 Two blood samples (1.2%) had THg levels above 3.5 μg/L, and no blood THg concentrations exceeded 5.8 μg/L.

3.3. Seafood consumption

A total of 49 mothers completed the FFQ (59%). A higher percentage of Caucasian mothers (77%) completed the FFQ compared to African American (53%) and Hispanic mothers (40%) (Chi-squared, p=0.02, n=83). Mothers who were more educated (≥some college) (75%) were twice as likely to complete the FFQ, compared to mothers who had an education level of high school or less (37%) (Chi-squared, p<0.01, n=83). Other covariates in Table 2 did not differ between mothers who completed the FFQ and those who did not (Chi-squared or Wilcoxon rank-sum, p=0.08–0.71, n=81–83).

Seafood consumption averaged 0.83 ± 0.78 meals/weekly (range: 0–3.5 meals/weekly). Nine mothers (18%) did not eat any seafood, and four mothers (8.2%) consumed seafood ≥twice/weekly. Of the five categories of seafood, average proportional intake was highest for shellfish (mean: 35%, median: 33%), then fried fish (mean: 22%, median: 0%), other fish not fried (mean: 21%, median: 6.3%), tuna (mean: 20%, median: 0%), and oysters (mean: 1.2%, median: 0%). African American mothers consumed seafood most frequently (mean: 0.96 meals/weekly, n=17), followed by Caucasian mothers (mean: 0.89 meals/weekly, n=24), and Hispanic mothers (mean: 0.34 meals/weekly, n=8); however, differences were not statistically significant (Kruskal-Wallis, p=0.06, n=49).

The number of weekly seafood meals was positively correlated with blood THg and MeHg concentrations during both early and late gestation [Spearman’s rho: (0.42, 0.64), p<0.01, n=49]. Blood inorganic Hg was not correlated with seafood ingestion during both early and late gestation (Spearman’s rho = 0.15 and 0.21, respectively, p=0.29 and 0.14, respectively, n=49).

3.4. Rice consumption

Mothers ingested on average 1.7 ± 1.7 servings/weekly of rice (range: 0–7.0 servings/weekly, n=49). Rice consumption differed significantly by ethnicity (Kruskal-Wallis, p<0.001, n=49), including higher rice consumption for African-American mothers (mean: 3.0 meals/weekly, n=17) compared to Caucasian and Hispanic mothers (mean for both: 1.0 meals/weekly, n=24 and n=8, respectively). Rice consumption (servings/weekly) was not correlated with blood THg, MeHg, or inorganic Hg during early and late gestation [Spearman’s rho: (0.01, 0.18), p= 0.21–0.92, n=49].

3.5. Changes in blood Hg between early/late gestation

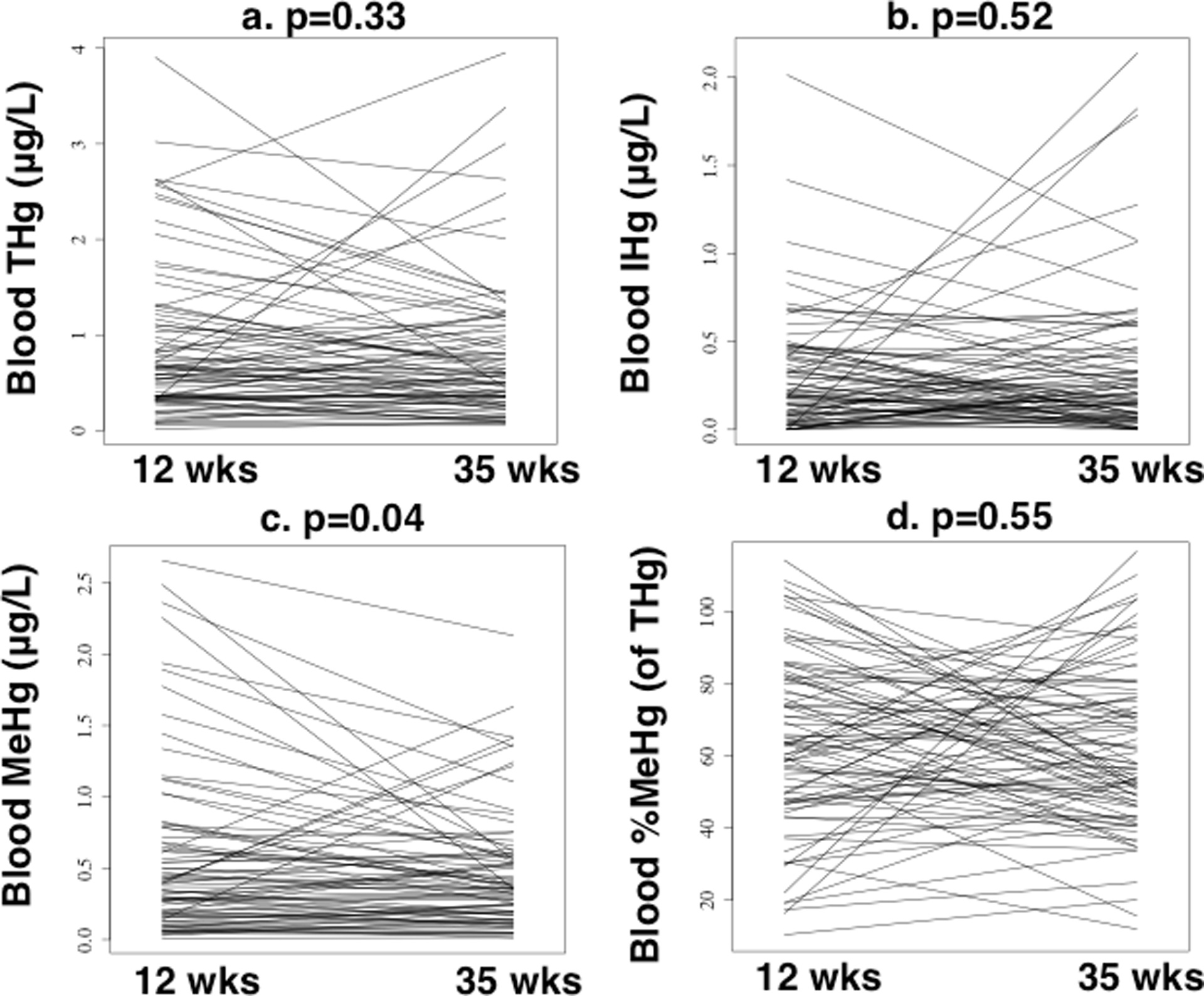

Average blood THg and MeHg concentrations decreased by 9.2% and 21%, respectively, while the average inorganic Hg concentration increased by 10% (Table 1). Average %MeHg (of THg) decreased by 2% (Table 1, Figures 2 and S1). The average change ± 1 SD (late gestation-early gestation) for blood THg, MeHg, and inorganic Hg was −0.08 ± 0.75 μg/L, −0.11 ± 0.48 μg/L, and +0.03 ± 0.44 μg/L, respectively, which indicated blood MeHg decreased, while blood inorganic Hg increased slightly. Between early gestation (12 ± 1.7 weeks) and late gestation (35 ± 2.2 weeks), blood MeHg decreased significantly (paired t-test, p=0.04, n=83), while no significant changes were observed for blood THg, inorganic Hg, or %MeHg (of THg) (2-tailed paired t-test: p= 0.34–0.55, n=83) (Figures 2 and S1).

Figure 2.

Changes in maternal blood mercury between early (12 ± 1.7 weeks) and late (35 ± 2.0 weeks) gestation (n=83 mothers), including a) total mercury (THg), b) inorganic mercury (IHg), c) methylmercury (MeHg), and d)%MeHg (of THg). P-values are reported for two-sided paired t-tests.

The hematocrit decreased on average (± 1 SD) from 36 ± 3.1 (%) to 35 ± 3.2 (%) between early/late gestation (2-tailed paired t-test, p<0.001, n=83). After adjusting blood Hg for the hematocrit (see Methods, Section 2.5), the decrease in blood MeHg was no longer statistically significant (2-tailed paired t-test, p=0.09, n=83). Hematocrit-adjusted blood THg did not change from early to late pregnancy (2-tailed paired t-test, p=0.66, n=83). Hematocrit-adjusted inorganic Hg increased between early and late gestation; however, this trend remained non-significant (2-tailed paired t-test, p=0.31, n=83).

3.6. Associations between blood Hg and other covariates

Blood THg and MeHg concentrations were significantly higher during early and late gestation for mothers who drank alcohol before becoming pregnant (Wilcoxon rank-sum, p≤0.01, n=83). Seafood consumption and alcohol consumption before pregnancy were also correlated (Wilcoxon rank-sum, p=0.04, n=49), suggesting mothers who ingested seafood also likely consumed alcohol. Blood THg and MeHg were also higher for mothers who previously smoked (during late gestation only) (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, p<0.05, n=83). As expected, previous smoking and alcohol consumption were strongly correlated (Fisher’s exact test, p<0.001, n=83). Blood THg and MeHg differed by race/ethnicity during both early and late gestation, including highest average values for African American mothers, compared to Caucasian and Hispanic mothers; although differences were not statistically significant (Kruskal-Wallis, p=0.07–0.10, n=83). Blood MeHg during early and late gestation differed significantly by IOM weight gain (Kruskal-Wallis, p<0.05, n=83), including higher blood MeHg for mothers who gained inadequate weight (n=22) compared to mothers who gained normal (n=34) or excessive weight (n=25). Blood inorganic Hg was not correlated with covariates in Table 2, aside from previous alcohol consumption during late gestation; i.e., blood inorganic Hg was higher for mother who drank alcohol before becoming pregnant (Wilcoxon rank-sum, p<0.05, n=83), which was similar to blood THg and MeHg. Additionally, blood inorganic Hg during late gestation was higher for mothers with more education (Kruskal-Wallis, p<0.05, n=83).

Using a mixed model, which adjusted for within-person variability, some differences were noted between the unadjusted and adjusted analyses (Table 3). Blood THg and blood MeHg (both log10-transformed) were significantly higher for African-American mothers compared to Caucasian mothers; however, no significant differences were observed for other variables. In addition, changes over time for blood MeHg were no longer significant.

Table 3.

Results for the fully adjusted model relating log10 blood mercury (dependent variable) and maternal characteristics using repeated-measures multivariable regression (n=81 mothers).

| Blood THg Exp (Beta) (95% CI) | Blood MeHg Exp (Beta) (95% CI) | Blood IHg1 Exp (Beta) (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time | |||

| Early gestation | (Referent) | (Referent) | (Referent) |

| Late gestation | 0.98 (0.82, 1.2) | 0.92 (0.78, 1.1) | 1.1 (0.77, 1.6) |

| Maternal Age (years) | 1.0 (0.97, 1.0) | 1.0 (0.97, 1.0) | 1.0 (0.96, 1.0) |

| Hematocrit (%) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.1) | 1.0 (0.98, 1.1) | 1.0 (0.94, 1.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| African American | (Referent) | (Referent) | (Referent) |

| Caucasian | 0.56 (0.36, 0.85)** | 0.57 (0.35, 0.94)* | 0.74 (0.44, 1.2) |

| Hispanic | 0.87 (0.52, 1.5) | 0.79 (0.42, 1.5) | 1.2 (0.64, 2.3) |

| Previous alcohol consumption (yes) | 2.2 (1.4, 3.3)*** | 2.1 (1.3, 3.4)** | 2.1 (1.3, 3.4)** |

| Vitamin D supplementation (yes) | 1.2 (0.82, 1.7) | 0.99 (0.65, 1.5) | 1.2 (0.81, 1.9) |

| IOM recommended weight gain | |||

| Inadequate | (Referent) | (Referent) | (Referent) |

| Adequate | 0.73 (0.47, 1.1) | 0.64 (0.38, 1.1) | 0.85 (0.50, 1.5) |

| Excessive | 0.65 (0.41, 1.0) | 0.48 (0.28, 0.83)** | 0.88 (0.51, 1.5) |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

CI (confidence interval), Exp (exponentiated), GW (gestational weeks), IHg (inorganic mercury), IOM (Institute of Medicine),23 MeHg (methylmercury), THg (total mercury)

IHg (estimated) = THg - MeHg

DISCUSSION

Proportional differences in blood MeHg.

We observed a wide range in values for the proportion of MeHg (of blood THg) (range: 10–117%, Table 1), which may have implications regarding the application of the MeHg reference dose. Blood THg is estimated to be >90% MeHg.2 For those studies that reported %MeHg (of THg), average values ranged from 57–79%,5,7–10 including the present study (Table 1). The reference dose for MeHg is 5.8 μg THg/L in cord blood, which was extrapolated to maternal blood THg (3.5 μg/L).32 However, the corresponding reference dose in maternal blood may be higher or lower than 3.5 μg/L, depending on the proportion of MeHg in maternal blood. Assuming the reference dose in cord blood is 80% MeHg (of THg) (0.8 × 5.8 μg/L THg = 4.6 μg/L MeHg), the corresponding dose in maternal blood is 2.8 μg/L MeHg. If maternal blood is also 80% MeHg (of THg), the reference dose remains 3.5 μg/L. However, in our study, blood %MeHg (of THg) ranged from 10–117%. The corresponding dose for maternal blood THg may be as low as 2.8 μg/L [assuming 100% MeHg (of THg)], or as high as 28 μg/L [assuming 10% MeHg (of THg)]. Our results suggest the reference dose for cord blood THg (5.8 μg/L) may be less protective when the proportion of MeHg is higher in maternal blood compared to cord blood; however, more studies are needed.

Longitudinal changes in blood MeHg.

Longitudinal trends for maternal blood MeHg were previously reported among pregnant mothers between 12 and 36 weeks gestation in Sweden (n=112)8 and between second trimester and delivery in Canada (n=101).33 Similar decreases in average blood MeHg were observed across all three studies, including this study (i.e., 21%, this study, 23% in Sweden, and 24% in Canada). Differences between early/late gestation were also significant in Sweden (paired t-test, p<0.001)8 and Canada (Wilcoxon signed rank, p≤0.02).33 Women in both the Swedish and Canadian pregnant cohorts reported reductions in fish consumption frequency during pregnancy, which may have contributed to decreases in blood MeHg.8,33 In our study, it is uncertain whether mothers reduced fish/shellfish consumption during pregnancy, because information on food frequencies was collected just one time. However, we were able to test whether hemodilution contributed to this decrease (Section 3.5), which was hypothesized as one reason for the decline in blood MeHg in Canada and Sweden.8,33 In our cohort, the decrease in blood MeHg was attenuated when blood MeHg was normalized by the hematocrit (paired t-test, p=0.09, n=83), suggesting hemodilution contributed to lower blood MeHg. Results for blood THg were less consistent between the three studies, including a non-significant decrease for the present study (2-tailed t-test, p=0.34, n=83), and a significant decrease in blood THg in Canada (Wilcoxon signed rank, p<0.01, n=101),33 while longitudinal changes for blood THg were not discussed in the Swedish study.8 Between the three studies, unadjusted trends were more consistent for blood MeHg compared to blood THg.

Racial/ethnic differences in blood Hg.

In repeated-measures multivariable regression analyses, African American mothers had higher blood THg and MeHg concentrations compared to Caucasian mothers (Table 3). Results for THg were consistent with other reports. For U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2010, non-Hispanic Black women had higher average blood THg concentrations compared to Non-Hispanic White women (n=10,087 women 16–49 years).34 Along the northeast Florida coast (n=703), African American women consumed more fish meals per month and had higher hair THg levels than Caucasian women.35 Among 258 fishermen in the Savannah River region, African Americans consumed more fish meals per month and larger portion sizes relative to Caucasians.36 Higher blood THg may contribute to greater health disparities among African American mothers,37 which should be further investigated.

There are some limitations of this study, which are worth noting. Only 49 mothers (59%) completed the FFQ, which differed by race/ethnicity, including a lower proportion of Hispanic mothers (40%) and African American mothers (53%), compared to Caucasian mothers (77%). Therefore, the relationship between blood Hg and fish/shellfish consumption may have been biased. However it is uncertain the direction of bias because seafood consumption was highest among African American mothers, and lowest among Hispanic mothers (Section 3.3). In addition, FFQs were administered one time, and there was no fish consumption information for participants during late pregnancy. This may have resulted in an underestimation or overestimation of blood Hg relative to fish/shellfish consumption. Other limitations include the small sample size, reliance on self-reported data for many demographic characteristics, lack of data on Hg in cord blood, and estimation of inorganic Hg through subtraction, which possibly introduced a substantial amount of error in these estimates.

Despite limitations, there were several strengths. Blood THg and MeHg were analyzed using CVAFS and GC-CVAFS, respectively, yielding low method detection levels. For comparison, the method detection levels using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry for blood THg and MeHg were 0.33 μg/L and 0.48 μg/L, respectively.9,34 Lower detection levels are important in populations with low MeHg exposure. The hematocrit was also quantified and the effect of hemodilution was investigated, which was not reported in previous longitudinal studies among pregnant mothers.8,33

In summary, in unadjusted models, blood MeHg decreased significantly from early to late pregnancy, while THg and inorganic Hg did not change significantly. Our results demonstrate that trends in blood THg may not always accurately reflect blood MeHg, especially in populations where %MeHg (of THg) is highly variable.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank the study coordinators, including Judy Shary and Martha Murphy, who oversaw participant recruitment and data collection. This study was supported in part by grants to S. Rothenberg from the U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R21 ES026412), the U.S. National Institute of Health Loan Replacement Program (L30 ES023165), and the University of South Carolina (Aspire-1). This study was also supported in part by a grant to C. Wagner from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the study sponsors. The study sponsors did not play a role in the study design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information includes Table S1 (quality assurance/quality control), Table S2 (summary statistics for blood Hg), and Figure S1 (box plots comparing blood Hg between early/late gestation). Supplemental information is available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-018-0033-1

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). Environmental Health Criteria 101: Methylmercury. World Health Organization, Geneva: 1990; Available: http://www.inchem.org/documents/ehc/ehc/ehc101.htm [accessed 5 Dec 2017] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Research Council (NRC). Toxicological effects of methylmercury. National Academy Press, Washington D.C. 2000; Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK225778/ [accessed 5 Dec 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarkson TW, Magos L. The toxicology of mercury and its chemical compounds. Crit Rev Toxicol 2006; 36:609–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cernichiari E, Brewer R, Myers GJ, Marsh DO, Lapham LW, Cox C, et al. Monitoring methylmercury during pregnancy: maternal hair predicts fetal brain exposure. Neurotoxicology 1995; 16:705–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang L, Evens C, Lazoff S, Woods JS, Cernichiari E, Horvat M, et al. Determination of methyl mercury in whole blood by ethylation-GC-CVAFS after alkaline digestion-solvent extraction. J Anal Toxicol 2000; 24:328–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeRouen TA, Martin MD, Leroux BG, Townes BD, Woods JS, Leitao J, et al. Neurobehavioral effects of dental amalgam in children. J Am Med Assoc 2006; 295:1784–1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rothenberg SE, Keiser S, Ajami NJ, Wong MC, Gesell J, Petrosino JF, et al. The role of gut microbiota in fetal methylmercury exposure: insights from a pilot study. Toxicol Lett 2016a; 242:60–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vahter M, Åkesson A, Lind B, Björs U, Schütz A, Berglund M. Longitudinal study of methylmercury and inorganic mercury in blood and urine of pregnant and lactating women, as well as in umbilical cord blood. Environ Res Section A 2000; 84:186–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wells EM, Herbstman JB, Lin YH, Hibbeln JR, Halden RU, Witter FR, et al. Methyl mercury, but not inorganic mercury, associated with higher blood pressure during pregnancy. Environ Res 2017; 154:247–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.You C-H, Kim B-G, Jo E-M, Kim G-Y, Yu B-C, Hong M-G, et al. The relationship between the fish consumption and blood total/methyl-mercury concentration of coastal area in Korea. Neurotoxicology 2012; 33:676–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koren O, Goodrich JK, Cullender TC, Spor A, Laitinen K, Backhed HK, et al. Host remodeling of the gut microbiome and metabolic changes during pregnancy. Cell 2012; 150:470–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Block G, DiSogra C. WIC Dietary Assessment Validation Study. Final Report. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service: Alexandria, VA, 1994. Available: www.nutritionquest.com [accessed 5 Dec 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hollis BW, Johnson D, Hulsey TC, Ebeling M, Wagner CL. Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy: double blind, randomized clinical trial of safety and effectiveness. J Bone Miner Res 2011; 26:2341–2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong C, Yu X, Liu J, Cheng Y, Rothenberg SE. Low-level methylmercury exposure through rice ingestion in a cohort of pregnant mothers in rural China. Environ Res 2016; 150:519–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothenberg SE, Windham-Myers L, Creswell JE. Rice methylmercury exposure and mitigation: a comprehensive review. Environ Res 2014; 133:407–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothenberg SE, Yu X, Liu J, Biasini FJ, Hong C, Jiang X, et al. Maternal methylmercury exposure through rice ingestion and offspring neurodevelopment: a prospective cohort study. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2016b; 219:832–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grandjean P, Weihe P, White RF, Debes F, Araki S, Yokoyama K, et al. Cognitive deficit in 7-year old children with prenatal exposure to methylmercury. Neurotoxicol Teratol 1997; 19:417–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahaffey KR, Clickner RP, Jeffries RA. Adult women’s blood mercury concentrations vary regionally in the United States: association with patterns of fish consumption (NHANES 1999–2004). Environ Health Perspect 2009; 117:47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pichichero ME, Gentile A, Giglio N, Umido V, Clarkson T, Cernichiardi E, et al. Mercury levels in newborns and infants after receipt of thimerosal-containing vaccines. Pediatrics 2008; 121:e208–14, doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothenberg SE, Korrick SA, Fayad R. The influence of obesity on blood mercury levels for U.S. non-pregnant adults and children: NHANES 2007–2010. Environ Res 2015; 138:173–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rowland IR, Robinson RD, Doherty RA. Effects of diet on mercury metabolism and excretion in mice given methylmercury: role of gut flora. Arch Environ Health 1984; 39:401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seko Y, Miura T, Takahashi M, Koyama T. Methyl mercury decomposition in mice treated with antibiotics. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol 1981; 49:259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Institute of Medicine (IOM). Weight gain during pregnancy: reexamining the guidelines. 2009. Available: http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2009/Weight-Gain-During-Pregnancy-Reexamining-the-Guidelines/Report%20Brief%20-%20Weight%20Gain%20During%20Pregnancy.pdf [accessed 5 Dec 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA). Appendix to Method 1631, Total Mercury in Tissue, Sludge, Sediment, and Soil by Acid Digestion and BrCl Oxidation, EPA-821-R-01–013. 2001a; Available: https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi/40001F6A.PDF?Dockey=40001F6A.PDF, [accessed 5 Dec 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA). Method 1631, Revision E: Mercury in Water by Oxidation, Purge and Trap, and Cold Vapor Atomic Fluorescence Spectrometry, EPA-821-R-02–019. 2002; Available: https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi/P1008IW8.PDF?Dockey=P1008IW8.PDF, [accessed 5 Dec 2017] [Google Scholar]

- 26.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA). Method 1630, Methyl Mercury in Water by Distillation Aqueous Ethylation, Purge and Trap, and Cold Vapor Atomic Spectrometry, EPA-821-R-01–020. 2001b; Available: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-08/documents/method_1630_1998.pdf [accessed 5 Dec 2017] [Google Scholar]

- 27.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA). 40 Code of Federal Regulation, Appendix B to Part 136: Definition and Procedure for the Determination of the Method Detection Limit- Revision 1.11 2011; Available: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2011-title40-vol23/pdf/CFR-2011-title40-vol23-part136-appB.pdf [accessed 5 Dec 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voegborlo RB, Matsuyama A, Adimado AA, Akagi H. Head hair total mercury and methylmercury levels in some Ghanaian individuals for the estimation of their exposure to mercury: preliminary studies. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 2010; 84:34–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schafer JL. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. Chapman & Hall, London, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hytten F Blood volume changes in normal pregnancy. Clin Haematol 1985; 14:601–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schell LM, Czerwinski S, Stark AD, Parsons PJ, Gomez M, Samelson R. Variation in blood lead and hematocrit levels during pregnancy in a socioeconomically disadvantaged population. Arch Environ Health 2000; 55:134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahaffey KR, Clickner RP, Bodurow CC. Blood organic mercury and dietary mercury intake: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 and 2000. Environ Health Perspect 2004; 112:562–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morrissette J, Takser L, St-Amour G, Smargiassi A, Lafond J, Mergler D. Temporal variation of blood and hair mercury levels in pregnancy and relation to fish consumption history in a population living along the St. Lawrence River. Environ Res 2004; 95:363–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA). Trends in Blood Mercury Concentrations and Fish Consumption Among U.S. Women of Childbearing Age NHANES, 1999–2010. EPA-823-R-13–002. 2013; Available: https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi/P100LP7Q.PDF?Dockey=P100LP7Q.PDF [accessed 5 Dec 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Traynor S, Kearney G, Olson D, Hilliard A, Palcic J. Fish consumption patterns and mercury exposure levels among women of childbearing age in Duval County, Florida. J Environ Health 2013; 75:8–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burger J, Stephens WL Jr, Boring CS, Kuklinski M, Gibbons JW, Gochfeld M. Factors in exposure assessment: ethnic and socioeconomic differences in fishing and consumption of fish caught along the Savannah River. Risk Anal 1999; 19:427–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burch JB, Robb SW, Puett R, Cai B, Wilkerson R, Karmous W, et al. Mercury in fish and adverse reproductive outcomes: results from South Carolina. Int J Health Geogr 2014; 13:30, doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-13-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.