Abstract

Decontamination can limit environmental transmission of infectious agents. It is required for the safe re-use of contaminated medical, laboratory and personal protective equipment, and for the safe handling of biological samples. Heat is widely used for inactivation of infectious agents, notably viruses. We show that for liquid specimens (here, solution of SARS-CoV-2 in cell culture medium), virus inactivation rate under heat treatment at 70°C can vary by almost two orders of magnitude depending on the treatment procedure, from a half-life of 0.86 min (95% credible interval: [0.09, 1.77]) in closed vials in a heat block to 37.00 min ([12.65, 869.82]) in uncovered plates in a dry oven. These findings suggest a critical role of evaporation in virus inactivation via dry heat. Placing samples in open or uncovered containers may dramatically reduce the speed and efficacy of heat treatment for virus inactivation. We conducted a literature review focused on the effect of temperature on coronavirus stability and found that specimen containers, and whether they were closed, covered or uncovered, are rarely reported in the scientific literature. Heat-treatment procedures must be fully specified when reporting experimental studies to facilitate result interpretation and reproducibility, and carefully considered when designing decontamination guidelines.

Keywords: Environmental stability, environmental persistence, decontamination, temperature, heat treatment, coronavirus

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to millions of infections worldwide via multiple modes of transmission. Transmission is thought to occur via respiratory particles expelled by individuals infected by the causative virus, SARS-CoV-2 [1–3]. Epidemiological investigations suggest the occurence of environmental transmission of SARS-CoV-2 [4], which is possible because the virus remains stable for a period of time on inert surfaces and in aerosols [5, 6]. Environmental transmission has been suspected or demonstrated for many other viruses, including hepatitis viruses [7], noroviruses [8], and influenza viruses [9] among others. Rapid and effective decontamination methods can help limit environmental transmission during infectious disease outbreaks.

Heat is widely used for the inactivation of various infectious agents, notably viruses [10]. It is thought to inactivate viruses mainly by denaturing the secondary structures of proteins and other molecules, resulting in impaired function [11]. It is used for the decontamination of various materials, such as personal protective equipment (PPE), examination and surgical tools, culture and transportation media, and biological samples [12–15]. For SARS-CoV-2, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends moist heat as a virus inactivation method [16].

In this context, studies have evaluated the effectiveness of heat to inactivate coronaviruses on various household surfaces, PPE, culture and transportation media, and blood products [14, 17–22]. Heat-based decontamination procedures are also used for many other viruses, including hepatitis viruses [23], influenza viruses [24], parvoviruses [25], and human immunodeficiency viruses [26].

There are multiple ways to apply heat treatment. Heat can be dry or moist, heating implements can differ in degree of heat transfer (e.g. oven versus heat block, the latter theoretically allowing a higher heat transfer), and different levels of evaporation may be permitted (e.g. samples deposited on flat surfaces or contained in open plates will evaporate more than those in closed vials; both types of container are used in laboratories). Local temperature and humidity impact virus inactivation rates by affecting molecular interactions and solute concentration [27]. It follows that factors such as heat transfer and evaporation (which determine solute concentration and alter microenvironment temperature through evaporative cooling) likely modulate virus inactivation rates just as ambient temperature does.

We assessed the impact of heat-treatment procedure on SARS-CoV-2 inactivation. We studied dry heat treatment applied to a liquid specimen (virus suspension in cell culture medium), keeping temperature constant (at 70°C) but allowing different degrees of heat transfer (using a dry oven or a heat block) and evaporation (placing samples in closed vials, covered plates or uncovered plates). We then compared the half-lives of SARS-CoV-2 under these different procedures. In light of our results, we reviewed the literature to assess whether heat-treatment procedure descriptions are detailed enough to allow replication and inter-study comparison. We focused our literature review on coronavirus inactivation.

Results

Estimation of SARS-CoV-2 half-life under four distinct heat-treatment procedures

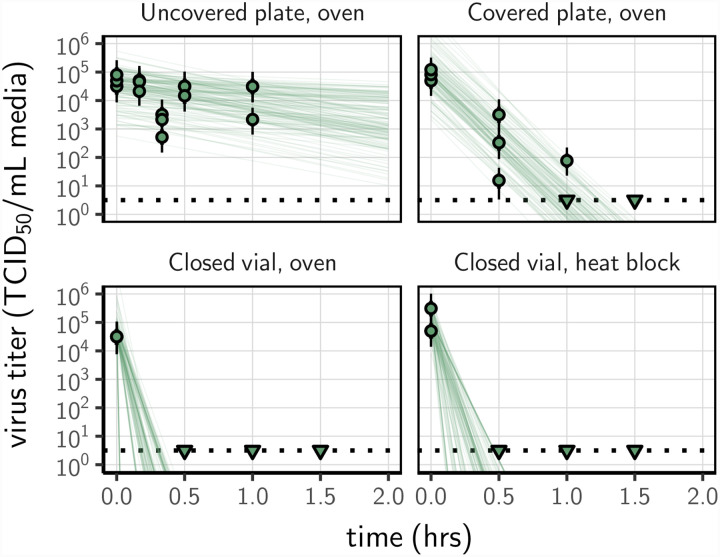

We prepared a solution of cell culture medium containing SARS-CoV-2, and exposed it to 70°C heat following four procedures using different sample containers or heating systems: (1) an uncovered 24-well plate, (2) a covered 24-well plate (using an unsealed plastic lid), (3) a set of closed 2 mL vials in a dry oven, and (4) a set of closed 2 mL vials in a heat block containing water. Three replicates were performed for each treatment. The inactivation rate of SARS-CoV-2 differed sharply across the heat-treatment procedures. There were large differences in the time until the virus dropped below detectable levels despite comparable initial quantities of virus (estimated mean initial titer ranging from 4.5 [4.1,5.0] log10 TCID50/mL for the uncovered plate in an oven to 5.0 [4.7,5.5] for the closed vials in a heat block, Fig. 1). We could not detect viable virus in the medium after 30 min of treatment (the earliest time-point) in closed vials heated either in a heat block or in a dry oven; we could not detect viable virus after 90 min in covered plates (Fig. 1). In uncovered plates, we observed a reduction of viral titer of approximately 1log10 TCID50/mL after 60 min. Macroscopic evaporation was observed in the uncovered plates and almost complete at 60 min.

Figure 1.

Inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 by heat treatment under different procedures. A solution of SARS-CoV-2 was exposed to 70°C heat. Samples were placed in uncovered or covered 24-well plates, or in closed 2 mL vial before heat treatment using a dry oven or a heat block. Samples were then collected at indicted time-points during heat treatment. Viable virus titer estimated by end-point titration is shown in TCID50/mL media on a logarithmic scale. Points show estimated titers for each collected sample; vertical bar shows a 95% credible interval. Time-points with no positive wells for any replicate are plotted as triangles at the approximate single-replicate detection limit of the assay (LOD; denoted by a black dotted line at 100.5 TCID50/mL media) to indicate that a range of sub-LOD values are plausible. Lines show predicted decay of virus titer over time (10 random draws per datapoint from the joint posterior distribution of the exponential decay rate, i.e. negative of the slope, and datapoint intercept, i.e. initial virus titer).

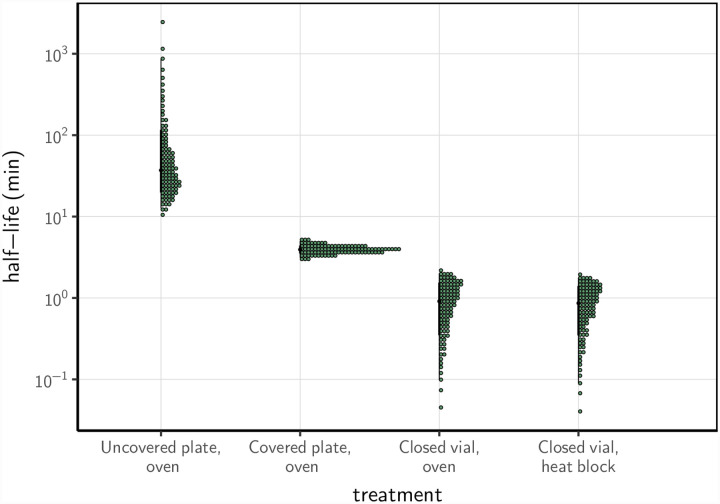

Using a Bayesian regression model, we estimated inactivation rates from the experimental data and converted them to half-lives to compare the four procedures. SARS-CoV-2 inactivation in the solution was most rapid in closed vials, using either a heat block or a dry oven (half-lives of 0.86 [0.09,1.77] and 1.91 [0.10,1.99] min, respectively), compared to the other treatment procedures (Fig. 2; Supplemental Material, Table S1). Inactivation rate was intermediate in covered plates (half-life of 3.94 [3.12,5.01] min) and considerably slower in uncovered plates (37.04 [12.65,869.82] min).

Figure 2.

Half-life of SARS-CoV-2 in a solution exposed to 70°C heat under different procedures. Quantile dotplots [62] of the posterior distribution for half-life of viable virus under each different heat-treatment procedure. Half-lives were calculated from the estimated exponential decay rates of virus titer (Fig. 1) and plotted on a logarithmic scale. For each distribution, the black dot shows the posterior median estimate and the black line shows the 95% credible interval.

Reporting of heat-treatment procedures in the literature

Given these findings, we conducted a literature review in order to assess whether heat-treatment procedures were reported with sufficient details to allow reproducibility. Our literature review identified 41 studies reporting the effect of temperature on coronavirus stability (Fig. S1), covering 12 coronavirus species, and temperature ranging from −70 to 100°C (Table. S2). Among those 41 studies, 14 included some information about the containers used, and 5 specified whether containers were closed. Only a single study reported container type and container closure explicitly for all experimental conditions [28]. Studies of virus stability in bulk liquid medium were conducted in vials [6, 20, 21, 28–35]. Studies interested in virus stability on surfaces were conducted directly in vials, in well plates [36] or trays [37], or on surface coupons placed in vials [29] or placed directly on oven rack (personal communication [14]). When specified, vial volume ranged from 1.5 mL to 50 mL [21, 30, 32], and sample volume from 0.001 to 45 mL. Finally, 24 studies included some information about how controlled temperature (and, in some cases, humidity) conditions were created. Methods included water baths [17, 19, 20, 28, 32, 34, 35, 38, 39], heat blocks [30, 33, 40], incubators [37, 41–45], ovens [14], refrigerators [46–48], isothermal boxes [47], and boxes with saturated salt solutions [49].

Discussion

Using SARS-CoV-2 as an illustration, we demonstrate that the choice of heat treatment procedure has a considerable impact on virus inactivation in liquid specimens. In liquid specimens (here, virus suspension in cell culture medium), SARS-CoV-2 half-life can vary from 0.86 min ([0.09, 1.77]) in closed vials to 37.0 min ([12.65, 869.82]) in uncovered plates treated with dry heat at 70°C. The rapid virus inactivation rate seen in closed vials subject to dry heat at 70°C agrees with previously reported results for inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 in virus transportation medium [50], SARS-CoV-1 in human serum [17], and MERS-CoV [18] and canine coronavirus in cell culture medium [21], among other results. All showed a loss of infectivity on the order of 104–6 TCID50 after 5–10 min at 65–75°C. None of these studies report sufficient details on their protocol to know which of our tested procedures corresponds most closely to their approach.

Our findings suggest that evaporation may play a critical role in determining the rate of virus inactivation during dry heat treatment. There are several mechanisms by which evaporation could impact the effectiveness of heat treatments to inactivate viruses. First, evaporation could induce a local drop in temperature due to the enthalpy of vaporization of water (or evaporative cooling), limiting the effect of heat itself. Second, evaporation could lead to modifications of the virion’s solute environment: solutes become more concentrated as the solvent evaporates, and under certain conditions efflorescence (i.e., crystal formation) can occur [51]. Mechanistic modeling of virus inactivation data shows that increased solute concentration increases virus inactivation rate, but efflorescence decreases inactivation rate [27]. We find that the more evaporation is allowed during dry heat treatment, the slower inactivation becomes. This suggests that evaporative cooling, efflorescence, or both, but not concentration of dissolved solutes, may drive lower inactivation rates in closed containers. This could help explain why low ambient humidity levels lead to slow inactivation at high temperatures [43], as low humidity levels allow for more evaporation and possibly efflorescence.

Better understanding the impact of temperature and humidity on virus inactivation is critical not only for designing efficient decontamination protocols but also for predicting virus persistence under different environmental conditions, with consequences for real-world transmission [27, 52, 53]. Heat transfer could potentially also play a role in determining the rate of virus inactivation using dry heat, but our experimental design did not allow us to explore this hypothesis since virus inactivation was extremely rapid in closed vials regardless of whether they were exposed to heat using an dry oven or a heat block.

Given the substantial effect of heat-treatment procedure on virus inactivation rates, it is critical to specify procedures precisely when comparing inactivation rates between studies or producing guidelines for decontamination. In particular, our results show that protocols that use open containers or uncovered surfaces lead to much slower viral inactivation, at least in bulk medium. If meta-analyses of the effect of temperature on virus inactivation were to integrate together data collected following different procedures, without corrections, they may lead to false conclusions.

Our work has critical implications for practical decontamination practice using heat treatment. Inactivation rates reported by studies conducted using closed vials may dramatically underestimate the time needed to decontaminate a piece of equipment (uncovered) in a dry oven. We have previously estimated the half-life of SARS-CoV-2 on stainless steel and N95 fabric when exposed to 70°C using a dry oven, without a container to limit evaporation. We found half-lives of approximately 9 and 5 min, respectively [14]. These values are on the same order of magnitude as the half-life of the virus in bulk solution exposed to heat treatment in a covered plate (3.94 [3.12,5.01] min), and considerably higher than the half-life of the virus exposed to heat treatment in bulk solution in a closed vial. Inactivation rates reported by studies conducted on closed vials should not be used to directly inform decontamination guidelines of pieces of equipment that cannot be treated using the same exact procedure.

Despite the limited information available, our literature review reveals that a variety of setups are used to hold samples and control environmental conditions for virus stability and inactivation experiments. Unfortunately, the majority of studies of heat treatment for virus inactivation do not report the exact procedures under which the samples were exposed to heat (in particular whether they were in closed, covered, or uncovered containers). This makes it difficult to compare inactivation rates among studies, and risky to use estimates from the literature to inform decontamination guidelines. More generally, given the large effect of environment on virus inactivation rate, we recommend that decontamination procedures be validated specifically for the setup to be used, rather than based on inactivation rate estimates from the literature, especially if experimental protocols are unclear.

Our study focuses exclusively on virus inactivation by heat. Other factors may affect virus inactivation rate in liquid specimens, including pH, salinity, and protein concentration [20, 51, 54]; we consider these only implicitly, insofar as they are affected by evaporation. In addition, the impact of heat treatment procedure on inactivation rate may differ across microbes. Enveloped and non-enveloped viruses may behave differently from each other, and bacteria may behave differently from viruses [51]. Finally, decontamination procedures must consider not only the effectiveness and speed of pathogen inactivation but also the potential impact of the procedure on the integrity of the decontaminated equipment or specimen. This is particularly important for PPE and for biological samples [14, 55, 56]. Any effort to translate inactivation rates (or even relative patterns) from one setting to another should thus be undertaken cautiously, accounting for these factors. Effective, reliable decontamination requires careful attention to treatment procedure; results from the literature with unclear methods may not be translatable.

Material and Methods

Laboratory experiments

We used SARS-CoV-2 strain HCoV-19 nCoV-WA1–2020 (MN985325.1) [57] for all our experiments. We prepared a solution of SARS-CoV-2 in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium cell culture medium (Sigma-Aldrich, reference D6546) supplemented with 2 nM L-glutamine, 2% fetal bovine serum and 100 units/mL penicillin/streptomycin. For each of the four heat-treatment procedures considered, we placed samples of 1 mL of this solution in plate wells or vials before heat treatment. Samples were removed at 10, 20, 30 and 60 min from the uncovered 24-well plate, or at 30, 60 and 90 min for the three other procedures. We took a 0 min time-point measurement prior to exposing the specimens to the heat treatment. As evaporation was observed after exposure to heat, all the samples were complemented to 1 mL with suspension medium (supplemented DMEM) at sampling. At each collection time-point, samples were transferred into a vial and frozen at −80°C until titration (or directly frozen for experiments conducted in vials). We performed three replicates for each inactivation procedure. Samples were not exposed to direct sunlight during the experiment. We quantified viable virus contained in the collected samples by end-point titration on Vero E6 cells as described previously [14].

Statistical analyses

We quantified the inactivation rate of SARS-CoV-2 in a solution following different heat-treatment procedures by adapting a Bayesian approach described previously [14]. Briefly, we inferred virus titers from raw endpoint titration well data by modeling well infections as a Poisson single-hit process [58]. Then, we estimated the decay rates of viable virus titer using a regression model. This modeling approach allowed us to account for differences in initial virus titers (0 min time-point) across samples as well as other sources of experimental noise. The model yields posterior distributions for the virus inactivation rate under each of the treatment procedures—that is, estimates of the range of plausible values for each of these parameters given our data, with an estimate of the overall uncertainty [59]. We then calculated half-lives from the estimated inactivation rates. We analyzed data obtained under different treatment procedures separately. We placed weakly informative prior distributions on mean initial virus titers and log virus half-lives. The complete model is detailed in the Supplemental Material.

We estimated virus titers and model parameters by drawing posterior samples using Stan [60], which implements a No-U-Turn Sampler (a form of Markov Chain Monte Carlo), via its R interface RStan. We report estimated titers and model parameters as the median [95% credible interval] of their posterior distribution. We assessed convergence by examining trace plots and confirming sufficient effective sample sizes and values for all parameters. We confirmed appropriateness of prior distributions with prior predictive checks and assessed goodness of fit by plotting regression lines against estimated titers and through posterior predictive (SI, Fig. S2–S4).

Literature review

We screened the Web of Science Core Collection database on December 28, 2020 using the following key words: “coronavir* AND (stability OR viability OR inactiv*) AND (temperature OR heat OR humidity)” (190 records). We also considered opportunistically found publications (23 records). We then selected the studies reporting original data focused on the effect of temperature on coronavirus inactivation obtained in experimental conditions (Fig. S1). For each selected study, we recorded information on virus, suspension medium, container, incubator, temperature and humidity (Table. S2).

Data accessibility

Code and data to reproduce the Bayesian estimation results and produce corresponding figures are available on Github: https://github.com/dylanhmorris/heat-inactivation [61]

Supplementary Material

Importance.

Heat is a powerful weapon against most infectious agents. It is widely used for decontamination of medical, laboratory and personal protective equipment, and for biological samples. There are many methods of heat treatment, and methodological details can affect speed and efficacy of decontamination. We applied four different heat-treatment procedures to liquid specimens containing SARS-CoV-2. The results reveal an important effect of the containers used to store specimens during decontamination: for a given initial level of contamination, decontamination time can vary from a few minutes in closed vials to several hours in uncovered plates. Reviewing the literature, we found that container choices and heat treatment methods are rarely made explicit in methods sections. Our study shows that careful consideration of heat-treatment procedure—in particular the choice of specimen container, and whether it is covered—can make results more consistent across studies, improve decontamination practice, and provide insight into the mechanisms of virus inactivation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Linsey C. Marr for helpful discussions. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH). JOL-S, AG, and DHM were supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency DARPA PREEMPT (D18AC00031), JOL-S and AG were supported by the UCLA AIDS Institute and Charity Treks, and JOL-S was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (DEB-1557022), the Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP, RC-2635) of the U.S. Department of Defense.

Footnotes

Supplemental Material file list

Supplemental file 1 - Supplemental text, tables (Tables S1–S2) and figures (Figures S1–S4). PDF file

References

- 1.Ong S. W. X. et al. Air, Surface Environmental, and Personal Protective Equipment Contamination by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from a Symptomatic Patient. JAMA (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai J. et al. Indirect Virus Transmission in Cluster of COVID-19 Cases, Wenzhou, China, 2020. Emerging Infectious Diseases 26 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwon K.-S. et al. Evidence of Long-Distance Droplet Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by Direct Air Flow in a Restaurant in Korea. Journal of Korean medical science 35 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azimi P., Keshavarz Z., Cedeno Laurent J. G., Stephens B. & Allen J. G. Mechanistic transmission modeling of COVID-19 on the Diamond Princess cruise ship demonstrates the importance of aerosol transmission. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118. eprint: https://www.pnas.org/content/118/8/e2015482118.full.pdf. https://www.pnas.org/content/118/8/e2015482118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Doremalen N. et al. Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1. New England Journal of Medicine, NEJMc2004973 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matson M. J. et al. Effect of Environmental Conditions on SARS-CoV-2 Stability in Human Nasal Mucus and Sputum. Emerging Infectious Diseases 26 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfaender S. et al. Environmental Stability and Infectivity of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) in Different Human Body Fluids. Frontiers in microbiology 9, 504 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopman B. et al. Environmental Transmission of Norovirus Gastroenteritis. Current opinion in virology 2, 96–102 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breban R., Drake J. M., Stallknecht D. E. & Rohani P. The Role of Environmental Transmission in Recurrent Avian Influenza Epidemics. PLoS computational biology 5, e1000346 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogers W. in Sterilisation of Biomaterials and Medical Devices 20–55 (Elsevier, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wigginton K. R., Pecson B. M., Sigstam T., Bosshard F. & Kohn T. Virus Inactivation Mechanisms: Impact of Disinfectants on Virus Function and Structural Integrity. Environmental Science & Technology 46, 12069–12078 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang L., Yan Y. & Wang L. Coronavirus Disease 2019: Coronaviruses and Blood Safety. Transfusion Medicine Reviews (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henwood A. F. Coronavirus Disinfection in Histopathology. Journal of Histotechnology(2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischer R. J. et al. Effectiveness of N95 Respirator Decontamination and Reuse against SARS-CoV-2 Virus. Emerging Infectious Diseases 26, 2253 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heimbuch B. K. et al. A Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Study: Use of Energetic Methods to Decontaminate Filtering Facepiece Respirators Contaminated with H1N1 Aerosols and Droplets. American Journal of Infection Control 39, 265–270 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Implementing Filtering Facepiece Respirator (FFR) Reuse, Including Reuse after Decontamination, When There Are Known Shortages of N95 Respirators 2020.

- 17.Darnell M. E. R. & Taylor D. R. Evaluation of Inactivation Methods for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus in Noncellular Blood Products. Transfusion 46, 1770–1777 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leclercq I., Batéjat C., Burguière A. M. & Manuguerra J.-C. Heat Inactivation of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 8 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pagat A.-M. et al. Evaluation of SARS-Coronavirus Decontamination Procedures. Applied Biosafety 12, 100–108 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laude H. Thermal Inactivation Studies of a Coronavirus, Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus. The Journal of General Virology 56, 235–240 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pratelli A. Canine Coronavirus Inactivation with Physical and Chemical Agents. The Veterinary Journal 177, 71–79 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duan S.-M. et al. Stability of SARS Coronavirus in Human Specimens and Environment and Its Sensitivity to Heating and UV Irradiation. Biomedical and Environmental Sciences 16, 246–255 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abu-Aisha H. et al. The Effect of Chemical and Heat Disinfection of the Hemodialysis Machines on the Spread of Hepatitis c Virus Infection: A Prospective Study. Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation 6, 174 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeong E. K., Bae J. E. & Kim I. S. Inactivation of Influenza A Virus H1N1 by Disinfection Process. American Journal of Infection Control 38, 354–360 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eterpi M., McDonnell G. & Thomas V. Disinfection Efficacy against Parvoviruses Compared with Reference Viruses. Journal of Hospital Infection 73, 64–70 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Guidelines on Sterilization and Disinfection Methods Effective against Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) tech. rep. (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris D. H. et al. Mechanistic Theory Predicts the Effects of Temperature and Humidity on Inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 and Other Enveloped Viruses. bioRxiv. eprint: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2020/12/18/2020.10.16.341883.full.pdf (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hulst M. M. et al. Study on Inactivation of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhoea Virus, Porcine Sapelovirus 1 and Adenovirus in the Production and Storage of Laboratory Spray-Dried Porcine Plasma. Journal of Applied Microbiology 126, 1931–1943 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan K.-H. et al. Factors Affecting Stability and Infectivity of SARS-CoV-2. Journal of Hospital Infection 106, 226–231 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darnell M. E. R., Subbarao K., Feinstone S. M. & Taylor D. R. Inactivation of the Coronavirus That Induces Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, SARS-CoV. Journal of Virological Methods 121, 85–91 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gundy P. M., Gerba C. P. & Pepper I. L. Survival of Coronaviruses in Water and Wastewater. Food and Environmental Virology 1 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kariwa H., Fujii N. & Takashima K. Inactivation of SARS Coronavirus by Means of Povidone-Iodine, Physical Conditions and Chemical Reagents. Dermatology 212, 119–123 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim Y.-I. et al. Development of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Thermal Inactivation Method with Preservation of Diagnostic Sensitivity. Journal of Microbiology 58, 886–891 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pujols J. & Segalés J. Survivability of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus (PEDV) in Bovine Plasma Submitted to Spray Drying Processing and Held at Different Time by Temperature Storage Conditions. Veterinary microbiology 174, 427–432 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saknimit M., Inatsuki I., Sugiyama Y. & Yagami K. Virucidal Efficacy of Physico-Chemical Treatments against Coronaviruses and Parvoviruses of Laboratory Animals. Experimental Animals 37, 341–345 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan K. H. et al. The Effects of Temperature and Relative Humidity on the Viability of the SARS Coronavirus. Advances in Virology 2011, 1–7 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas P. R. et al. Evaluation of Time and Temperature Sufficient to Inactivate Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus in Swine Feces on Metal Surfaces. Journal of Swine Health and Production 23, 84 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hofmann M. & Wyler R. Quantitation, Biological and Physicochemical Properties of Cell Culture-Adapted Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Coronavirus (PEDV). Veterinary microbiology 20, 131–142 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Unger S. et al. Holder Pasteurization of Donor Breast Milk Can Inactivate SARS-CoV-2. Canadian Medical Association Journal 192, E1657–E1661 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Batéjat C., Grassin Q., Manuguerra J.-C. & Leclercq I. Heat Inactivation of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2. bioRxiv, 2020.05.01.067769 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T. & Munster V. Stability of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) under Different Environmental Conditions. Eurosurveillance 18, 20590 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riddell S., Goldie S., Hill A., Eagles D. & Drew T. W. The Effect of Temperature on Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 on Common Surfaces. Virology Journal 17 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rockey N. et al. Humidity and Deposition Solution Play a Critical Role in Virus Inactivation by Heat Treatment of N95 Respirators. Msphere 5 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Daeschler S. C. et al. Effect of Moist Heat Reprocessing of N95 Respirators on SARS-CoV-2 Inactivation and Respirator Function. CMAJ 192, E1189–E1197 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Biryukov J. et al. Increasing Temperature and Relative Humidity Accelerates Inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 on Surfaces. mSphere 5 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mullis L., Saif L. J., Zhang Y., Zhang X. & Azevedo M. S. Stability of Bovine Coronavirus on Lettuce Surfaces under Household Refrigeration Conditions. Food Microbiology 30, 180–186 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guionie O. et al. An Experimental Study of the Survival of Turkey Coronavirus at Room Temperature and +4C. Avian Pathology 42, 248–252 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Casanova L., Rutala W. A., Weber D. J. & Sobsey M. D. Survival of Surrogate Coronaviruses in Water. Water Research 43, 1893–1898 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Casanova L. M., Jeon S., Rutala W. A., Weber D. J. & Sobsey M. D. Effects of Air Temperature and Relative Humidity on Coronavirus Survival on Surfaces. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 76, 2712–2717 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chin A. W. H. et al. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in Different Environmental Conditions. The Lancet Microbe 1, e10 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang W. & Marr L. C. Mechanisms by Which Ambient Humidity May Affect Viruses in Aerosols. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 78, 6781–6788 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Posada J., Redrow J. & Celik I. A Mathematical Model for Predicting the Viability of Airborne Viruses. Journal of Virological Methods 164, 88–95 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lofgren E., Fefferman N. H., Naumov Y. N., Gorski J. & Naumova E. N. Influenza Seasonality: Underlying Causes and Modeling Theories. Journal of Virology 81, 5429–5436 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benbough J. E. Some Factors Affecting the Survival of Airborne Viruses. The Journal of General Virology 10, 209–220 (1971). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Estep T. N., Bechtel M. K., Miller T. J. & Bagdasarian A. Virus Inactivation in Hemoglobin Solutions by Heat. Biomaterials, Artificial Cells and Artificial Organs 16, 129–134 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gertsman S. et al. Microwave- and Heat-Based Decontamination of N95 Filtering Facepiece Respirators: A Systematic Review. Open Science Framewor (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holshue M. L. et al. First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 382, 929–936 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brownie C. et al. Estimating Viral Titres in Solutions with Low Viral Loads. Biologicals 39, 224–230 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gelman A. et al. Bayesian Data Analysis, Third Edition (CRC Press, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carpenter B. et al. Stan: A Probabilistic Programming Language. Journal of statistical software 76 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gamble A.. et al. Data from “Heat-treated virus inactivation rate depends strongly on treatment procedure: illustration with SARS-CoV-2”. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00314-21. https://github.com/dylanhmorris/heat-inactivation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Kay M., Kola T., Hullman J. R. & Munson S. A. When (ish) is my bus? user-centered visualizations of uncertainty in everyday, mobile predictive systems in Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (2016), 5092–5103. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Code and data to reproduce the Bayesian estimation results and produce corresponding figures are available on Github: https://github.com/dylanhmorris/heat-inactivation [61]