Abstract

Background/Objective

The incidence of pain and/or fatigue in people with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is associated with reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and the ability to work, despite modern advanced therapeutic approaches. This real-world, international study examined these relationships in patients with PsA treated with tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi).

Methods

Data from 13 countries were analysed. Patients with PsA and their physicians completed questionnaires capturing demographics, current therapy, current disease status, HRQoL and work status via Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form version 2 (SF-36v2), 3-level 5-dimension EuroQoL questionnaire, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index, and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire.

Results

640 patients with PsA were included who had been receiving TNFi for ≥3 months and had completed SF-36v2 bodily pain and vitality domains. Of these, 33.1%, 29.2% and 37.7% of patients reported no, moderate and severe pain, respectively, and 31.9%, 22.5% and 45.6% of patients reported low, moderate and severe fatigue, respectively. Scores across HRQoL variables and WPAI were significantly different across pain and fatigue cohorts (all p<0.0001), with HRQoL and WPAI measures considerably worse in patients with moderate to severe pain or fatigue than those with low pain or fatigue.

Conclusions

Despite treatment with biologic agents such as TNFi, data from this global study demonstrated that substantial pain and/or fatigue persist in patients with PsA and that these are significantly associated with reduced HRQoL, physical function and work productivity. These findings suggest that there is an unmet need for additional PsA therapies.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Early Rheumatoid Arthritis, Knee Osteoarthritis, Outcomes research, Treatment, Patient perspective, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Corticosteroids, Ankylosing Spondylitis, Psoriatic Arthritis, Anti-TNF, DAS28, DMARDs (biologic)

INTRODUCTION

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic inflammatory disease with diverse effects on both skin and joints, varied course and long-term impact on patients’ lives.1– 4 The prevalence of PsA varies geographically, from 0.001% adults in Japan, 0.16% in the USA, up to 0.42% in Italy, and can occur in up to 40% of patients with psoriasis.1– 4

Patients with PsA experience local and systemic symptoms, erosive joint disease, impaired functioning and higher mortality.1 2 Pain and fatigue, common symptoms in patients with PsA, are often severe and represent an important element in the patient concept of PsA disease activity.5– 8 Pain in PsA may be persistent, and remains present even in patients who achieve minimal disease activity and who are on pharmacotherapy.8– 10 People with PsA report ‘role limitation’ and body pain, which can cause severe disability and seriously impact quality of life.11 Severe fatigue has been described as overwhelming and unlike normal tiredness, permeating every aspect of life and difficult to self-manage with little outside support.12 It is difficult to assess how widespread severe fatigue is among patients with PsA as multiple instruments have been used to assess fatigue in both research and clinical practice. However, estimates are that 57% of patients with PsA suffer from severe fatigue.5 There is a scarcity of information of the impact of fatigue on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and ability to work in this patient population.5 6

It has been shown that the proinflammatory cytokines tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), interleukin 23 (IL-23), interleukin 17 (IL-17) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) are elevated in PsA13– 17; therefore, current treatments available are targeted to these pathways. Therapy for PsA involves conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), targeted synthetic DMARDs such as apremilast and tofacitinib, and biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs). TNF inhibitors (TNFi) have historically been the most widely used bDMARDs.18 19

The purpose of this international study was to evaluate the frequency and severity of pain and fatigue in patients with PsA treated with TNFi in a real-world setting and explore the relationship of pain and fatigue severity with HRQoL and ability to work.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Data source

This study was a retrospective analysis using data from the Adelphi PsA Disease Specific Program (DSP) conducted in 13 countries between 2015 and 2016 in the USA and Mexico (N America), Europe (EU5; covering France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK), Asia-Pacific (APAC; covering Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Australia), and Turkey and Middle East (T&ME; covering Turkey and the United Arab Emirates).20 DSPs are large, multinational surveys designed to identify current disease management and patient- and physician-reported disease impact. They are point-in-time surveys conducted in real-world clinical practice.

Physicians included in the survey were instructed to complete a prespecified form for the next one to eight (variable by country) consecutive patients with active PsA who visited for diagnosis or routine care. Physician-reported forms included detailed questions querying patient demographics, clinical assessments, medication use and treatment history. Completion of the physician-reported form was undertaken through consultation of existing patient clinical records, as well as the judgement and diagnostic skills of the respondent physician, which is entirely consistent with decisions made in routine clinical practice.

Each patient for whom a physician-reported form was completed was invited to complete a voluntary patient-reported form, providing informed consent to participate. Patient-reported forms included the 3-level 5-dimension EuroQoL questionnaire (EQ-5D-3L),21 Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form health survey version 2 (SF-36v2),22 and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) general health questionnaire.23 Patients completed their forms independently from physicians and returned them in sealed envelopes to ensure confidentiality.

The DSP collected retrospective data using a non-interventional market research approach; no identifiable protected health information was collected. The DSP was conducted in accordance with the relevant legislation at the time of data collection, including the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act 199624 and Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act legislation.25 As this market research was run in accordance with the European Pharmaceutical Marketing Research Association guidelines, it did not require ethics committee approvals.26

Participating physicians and patients

Rheumatologists and dermatologists were eligible to participate in the study if they had worked ≥3 years as a physician, had qualified between 1979 and 2012, and were responsible for treatment decisions and management of patients with PsA.

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the study if they were ≥18 years old with a physician-confirmed diagnosis of PsA and were not currently enrolled in a clinical trial. Patients were eligible for inclusion in the analysis if they were receiving TNFi for ≥3 months and completed the SF-36v2 health survey. There were no exclusion criteria in the study.

Patient characteristics were provided by physicians, covering demographics, comorbidities including fibromyalgia, disease status including duration of disease, presence of inflammation, presence of enthesitis and treatment details including type of immunomodulatory therapy and use of prescribed and non-prescribed pain medication. Patient-reported happiness was assessed using SF-36v2 question 9 ‘How much of the time during the past week have you been happy?’ with possible responses: all of the time, most of the time, some of the time, a little of the time, none of the time.

Study variables

The SF-36v2 includes eight domains; bodily pain (BP) domain scores were stratified into tertiles to define patient cohorts with low, moderate or severe pain. The SF-36v2 vitality (VT) domain was used as an inverse construct for fatigue, and scores were stratified into tertiles to define patient cohorts with high vitality (low fatigue), moderate vitality (moderate fatigue) and low vitality (severe fatigue), balancing patient numbers between the three groups as far as possible while still satisfying the clinical definitions.27 The EQ-5D-3L questionnaire, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI), SF-36v2 domains and WPAI questionnaire were also used to assess patient outcomes.23 28 SF-36v2 age and gender normative data were generated based on US norms published in SF-36v2 manuals and updates.27

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses were conducted at global and regional levels (N America, EU5, APAC and T&ME). Categorical variables were described by counts and proportion of respondents, and continuous numerical variables were described by their means and SD.

Statistical differences across patient-reported outcomes by tertiles of pain and fatigue were assessed separately using Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous or ordinal data, and χ2 tests for categorical data. A significance level of 95% was used throughout. All analyses were conducted in Stata Statistical Software: Release 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Patients and physicians

Of 3782 patients with PsA who participated in the study, 1475 (39%) patients had been receiving TNFi for at least 3 months at the time of data collection. Of those, 640 (43.4%) patients (N America, n=176; EU5, n=329; APAC, n=97; T&ME, n=38) who completed both the SF-36v2 BP and VT domains were included in this analysis. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics for all patients by inclusion status and geographical region can be found in online supplementary table 1. The included patients were recruited by 320 physicians from 13 countries (N America, n=91; EU5, n=164; APAC, n=47; T&ME, n=18). Of 640 patients included in the analysis, 625 (97.7%) patients completed the EQ-5D-3L questionnaire and 623 (97.3%) patients completed the WPAI questionnaire, of whom 458 (84.0%) were employed at the time of questionnaire completion.

rmdopen-2020-001240s001.pdf (248.6KB, pdf)

Levels of pain and fatigue

Stratification of patients based on SF-36v2 BP domain scores resulted in three similarly sized patient tertiles of low pain (BP score: 76–100; n=212 (33.1%)), moderate pain (BP score: 53–75; n=187 (29.2%)) and severe pain (BP score: 0–52; n=241 (37.7%)) (table 1). The SF-36v2 BP domain scores were correlated with pain dimension of the EQ-5D-3L (spearman correlation coefficient=0.6756). Stratification of patients based on SF-36v2 VT domain scores resulted in three similarly sized patient tertiles of low fatigue (VT score: 66–100; n=204 (31.9%)), moderate fatigue (VT score: 51–65; n=144 (22.5%)) and severe fatigue (VT score: 0–50; n=292 (45.6%)).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics by pain and fatigue levels

| Pain | Fatigue | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Overall (n=640) |

Low (BP score 76–100) (n=212) |

Moderate (BP score 53–75) (n=187) |

Severe (BP score 0–52) (n=241) |

P value | Low (VT score 66–100) (n=204) |

Moderate (VT score 51–65) (n=144) |

Severe (VT score 0–50) (n=292) |

P value |

| Age, years | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 48.8 (11.6) | 46.2 (11.5) | 49.0 (10.6) | 50.9 (12.0) | 0.0002 | 47.6 (11.6) | 48.6 (11.1) | 49.7 (11.8) | 0.2428 |

| <65, n (%) | 573 (89.5) | 197 (92.9) | 167 (89.3) | 209 (86.7) | 0.0981 | 183 (89.7) | 131 (91.0) | 259 (88.7) | 0.7628 |

| Male, n (%) | 357 (55.8) | 132 (62.3) | 102 (54.5) | 123 (51.0) | 0.0516 | 118 (57.8) | 79 (54.9) | 160 (54.8) | 0.7725 |

| Mean (SD) BMI, kg/m2 | 26.3 (4.6) | 25.4 (3.9) | 27.0 (4.7) | 26.7 (4.9) | 0.0003 | 25.9 (4.6) | 26.3 (4.0) | 26.6 (4.9) | 0.0739 |

| Patient region, n (%) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| N America | 176 (27.5) | 59 (27.8) | 59 (31.6) | 58 (24.1) | 70 (34.3) | 44 (30.6) | 62 (21.2) | ||

| EU5 | 329 (51.4) | 113 (53.3) | 86 (46.0) | 130 (53.9) | 99 (48.5) | 69 (47.9) | 161 (55.1) | ||

| APAC | 97 (15.2) | 40 (18.9) | 31 (16.6) | 26 (10.8) | 35 (17.2) | 18 (12.5) | 44 (15.1) | ||

| T&ME | 38 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (5.9) | 27 (11.2) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (9.0) | 25 (8.6) | ||

| Time since symptom onset (years) | (n=531) | (n=169) | (n=157) | (n=205) | (n=160) | (n=121) | (n=250) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 7.9 (7.5) | 7.4 (7.0) | 8.0 (6.9) | 8.3 (8.3) | 0.7556 | 7.5 (6.6) | 7.0 (6.9) | 8.6 (8.2) | 0.1366 |

| Time since diagnosis (years) | (n=571) | (n=192 | (n=163) | (n=216) | (n=182) | (n=125) | (m=264) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 6.3 (6.4) | 6.0 (6.3) | 6.6 (6.1) | 6.3 (6.7) | 0.5556 | 6.5 (6.5) | 5.9 (6.2) | 6.3 (6.4) | 0.3846 |

| Presence of psoriasis, n (%) | 620 (96.9) | 205 (96.7) | 184 (98.4) | 231 (95.9) | 0.3189 | 198 (97.1) | 140 (97.2) | 282 (96.6) | 0.9200 |

| % BSA psoriasis | (n=498) | (n=169) | (n=151) | (n=178) | (n=163) | (n=115) | (n=220) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 9.1 (11.2) | 6.5 (9.0) | 7.4 (9.4) | 13.0 (13.4) | <0.0001 | 7.7 (11.7) | 7.0 (7.3) | 11.3 (12.2) | <0.0001 |

| HLA-B27 | (n=236) | (n=74) | (n=69) | (n=93) | (n=74) | (n=55) | (n=107) | ||

| +ve, n (%) | 92 (39.0) | 26 (35.1) | 31 (44.9) | 35 (37.6) | 0.4591 | 26 (35.1) | 31 (56.4) | 35 (32.7) | 0.7117 |

| Comorbid fibromyalgia*, n (%) | 23 (3.6) | 4 (1.9) | 5 (2.7) | 14 (5.8) | 0.0592 | 2 (1.0) | 6 (4.2) | 15 (5.1) | 0.0458 |

| Number of TNFi ever received, n (%) | (n=640) | (n=212) | (n=187) | (n=241) | 0.0227 | (n=204) | (n=144) | (n=292) | 0.0139 |

| 1 | 533 (83.3) | 184 (86.8) | 160 (85.6) | 189 (78.4) | 181 (88.7) | 111 (77.1) | 241 (82.5) | ||

| 2 | 61 (9.5) | 22 (10.4) | 15 (8.0) | 24 (10.0) | 13 (6.4) | 17 (11.8) | 31 (10.6) | ||

| 3+ | 18 (2.8) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (2.1) | 13 (5.3) | 2 (1.0) | 5 (3.5) | 11 (3.8) | ||

| Unknown | 28 (4.4) | 5 (2.4) | 8 (4.3) | 15 (6.2) | 8 (3.9) | 11 (7.6) | 9 (3.10) | ||

| Current severity*, n (%) | (n=640) | (n=212) | (n=187) | (n=241) | <0.0001 | (n=204) | (n=144) | (n=292) | <0.0001 |

| Mild | 435 (68.0) | 180 (84.9) | 148 (79.1) | 107 (44.4) | 168 (82.4) | 107 (74.3) | 160 (54.8) | ||

| Moderate | 182 (28.4) | 31 (14.6) | 36 (19.3) | 115 (47.7) | 34 (16.7) | 33 (22.9) | 115 (39.4) | ||

| Severe | 23 (3.6) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.6) | 19 (7.9) | 2 (1.0) | 4 (2.8) | 17 (5.8) | ||

| In remission*, n (%) | 349 (54.5) | 151 (71.2) | 102 (54.5) | 96 (39.8) | <0.0001 | 135 (66.2) | 81 (56.3) | 133 (45.5) | <0.0001 |

| Disease status*, n (%) | (n=639) | (n=212) | (n=187) | (n=240) | <0.0001 | (n=204) | (n=144) | (n=291) | 0.0016 |

| Stable/improving | 584 (91.4) | 203 (95.7) | 181 (96.8) | 200 (83.3) | 198 (92.1) | 130 (90.3) | 256 (88.0) | ||

| Unstable/deteriorating | 55 (8.6) | 9 (4.2) | 6 (3.2) | 40 (16.7) | 6 (2.9) | 14 (9.7) | 35 (12.0) | ||

| Current flare status*, n (%) | (n=639) | (n=212) | (n=187) | (n=240) | 0.0001 | (n=204) | (n=144) | (n=291) | 0.032 |

| Never flared | 373 (58.4) | 144 (67.9) | 101 (54.0) | 128 (53.3) | 133 (65.2) | 81 (56.3) | 159 (54.6) | ||

| Flares, not current | 242 (37.9) | 66 (31.1) | 80 (42.8) | 96 (40.0) | 68 (33.3) | 56 (38.9) | 118 (40.5) | ||

| Currently flaring | 24 (3.8) | 2 (0.9) | 6 (3.2) | 16 (6.7) | 3 (1.5) | 7 (4.9) | 14 (4.8) | ||

| ESR, mm/hour | (n=270) | (n=80) | (n=97) | (n=93) | (n=81) | (n=68) | (n=121) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 15.4 (12.2) | 11.2 (8.7) | 16.2 (13.0) | 18.3 (13.0) | <0.0001 | 12.0 (10.3) | 16.6 (15.8) | 17.1 (10.6) | 0.0001 |

| CRP, mg/L | (n=264) | (n=77) | (n=94) | (n=93) | (n=78) | (n=66) | (n=120) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 4.8 (7.2) | 2.2 (3.0) | 5.3 (7.2) | 6.4 (9.1) | <0.0001 | 3.4 (4.7) | 5.4 (8.4) | 5.3 (7.8) | 0.0115 |

APAC, Asia-Pacific Region; BMI, body mass index; BP, bodily pain domain; BSA, body surface area; CRP, C reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; EU5, Europe; HLA-B27, human leucocyte antigen B27; N America, the USA and Mexico; T&ME, Turkey and the Middle East; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitors; VT, vitality domain.

Physician reported. Tertiles generated to balance patient numbers between the groups, while still satisfying the definitions of low, moderate and severe pain and fatigue.

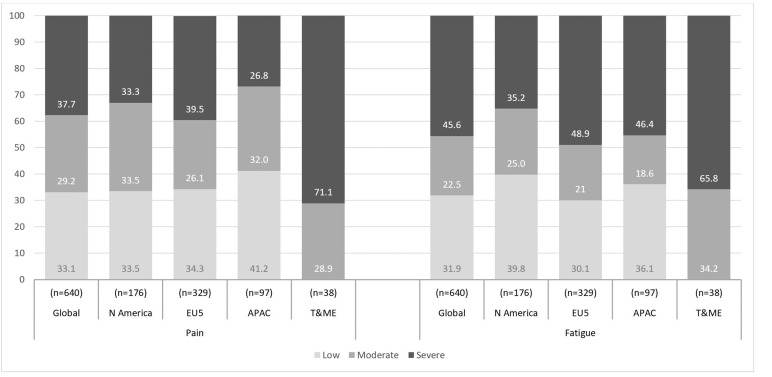

Pain and fatigue levels by geographical region are shown in figure 1. Globally, 37.7% and 45.6% of patients reported severe pain and fatigue, respectively. A higher proportion of patients in EU5 reported severe pain (39.5%) and severe fatigue (48.9%) than in other regions except for T&ME, where 71.1% and 65.8% of patients reported severe pain and fatigue, respectively.

Figure 1.

Pain and/or fatigue levels by region.

SF-36v2 BP and VT domain scores were stratified into tertiles to define patients with low, moderate or severe pain or fatigue. APAC, Asia-Pacific Region; BP, bodily pain; EU5, Europe; N America, the USA and Mexico, T&ME, Turkey and the Middle East; VT, vitality.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics by pain and fatigue levels

Patient characteristics that differed across pain (age, body mass index, geographical region, body surface area (BSA) affected by psoriasis) and fatigue (geographical region, BSA affected by psoriasis, comorbid fibromyalgia) levels are reported in table 1.

A higher proportion of patients reporting severe pain and fatigue had their disease rated as ‘severe’ by their physician than those reporting no or low pain and fatigue (Pain: 7.9% vs 0.5%, p<0.0001; Fatigue: 5.8% vs 1.0%, p<0.0001). A higher proportion of patients reporting severe pain and fatigue had their disease rated as ‘unstable/deteriorating’ by their physician than those reporting no or low pain and fatigue (Pain: 16.7% vs 4.2%, p<0.0001; Fatigue: 12.0% vs 2.9%, p=0.0016). A higher proportion of patients reporting severe pain and fatigue had current flares than those reporting low or no pain and fatigue (Pain: 6.7% vs 0.9%, p<0.0001; Fatigue: 4.8% vs 1.5%, p=0.032). However, 83.3% of patients reporting severe pain and 88.0% of patients reporting severe fatigue were considered to have ‘stable/improving’ disease by their physician, while a notable proportion of patients reporting severe pain (39.8%) and severe fatigue (45.5%) were deemed to be in remission, indicating a discordance between patient-reported pain and/or fatigue and physician’s assessment of disease (table 1).

Patients reporting severe pain and fatigue had erythrocyte sedimentation rate levels at 18.3 mm/hour and 17.1 mm/hour, respectively, compared with patients with low pain and fatigue with levels at 11.2 mm/hour and 12.0 mm/hour, respectively (p<0.0001 across low, moderate and severe pain and fatigue groups). Patients reporting severe pain and fatigue had C reactive protein levels at 6.4 mg/L and 5.3 mg/L, respectively, compared with patients with low pain and fatigue with levels at 2.2 mg/L and 3.4 mg/L, respectively (p<0.0001 across low, moderate and severe pain groups, and p=0.0115 across low, moderate and severe fatigue groups).

HRQoL by pain and fatigue levels

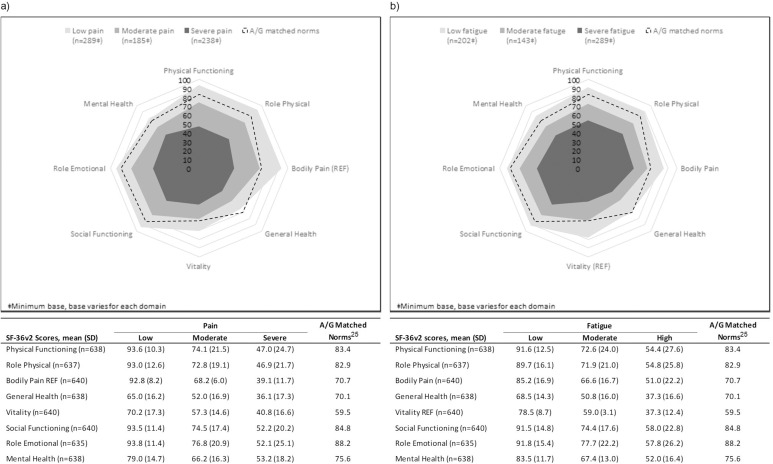

Figure 2 illustrates global SF-36v2 data reported by patients with low, moderate and severe pain and fatigue levels. Scores across all SF-36v2 domains (excluding BP, which is the reference category) were significantly different across the three pain cohorts (p<0.0001) (figure 2A). Similarly, all SF-36v2 domain scores (excluding VT, which is the reference category) were significantly different across the three fatigue cohorts (p<0.0001) (figure 2B). Scores in patients with moderate or severe pain and/or fatigue were considerably lower than the normative scores, whereas patients reporting low pain and/or fatigue levels had scores that approximated normal values for most SF-36v2 domains. In relation to mental health, in addition to the SF-36v2 Mental Health domain being significantly different across pain and fatigue cohorts, patient-reported happiness was also significantly different across pain and fatigue cohorts (both p<0.0001), with lower levels of happiness reported by patients with either severe pain or fatigue (table 2).

Figure 2.

Spydergram29 of SF-36v2 domain scores by pain (A) and fatigue (B) levels.

A/G, age/gender; SF-36v2, Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form version 2. All p<0.0001 across levels of pain and fatigue (low, moderate, severe).

Table 2.

Patient-reported quality of life and societal burden by pain and fatigue levels

| Pain | Fatigue | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Low (BP score 76–100) |

Moderate (BP score 53–75) |

Severe (BP score 0–52) |

P value | Low (VT score 66–100) |

Moderate (VT score 51–65) |

Severe (VT score 0–50) |

P value | |

| EQ-5D-3L | (n=625) | (n=208) | (n=183) | (n=234) | (n=198) | (n=143) | (n=284) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 0.756 (0.288) | 0.960 (0.094) | 0.790 (0.213) | 0.548 (0.313) | <0.0001 | 0.940 (0.100) | 0.776 (0.247) | 0.618 (0.320) | <0.0001 |

| EQ-VAS | (n=625) | (n=206) | (n=187) | (n=236) | (n=201) | (n=144) | (n=284) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 69.9 (19.2) | 82.0 (15.6) | 72.1 (14.4) | 57.5 (18.0) | <0.0001 | 82.5 (13.6) | 71.8 (17.3) | 60.0 (18.1) | <0.0001 |

| HAQ-DI | (n=625) | (n=206) | (n=184) | (n=235) | (n=200) | (n=141) | (n=284) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 0.6 (0.7) | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.5 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.7) | <0.0001 | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.5 (0.6) | 1 (0.8) | <0.0001 |

| SF-36v2 Q9. How much time during the past week … have you been happy?, n (%) | (n=635) | (n=211) | (n=186) | (n=238) | <0.0001 | (n=203) | (n=143) | (n=289) | <0.0001 |

| All/most of the time | 298 (46.9) | 152 (72.0) | 90 (48.4) | 56 (23.5) | 180 (88.7) | 68 (47.6) | 50 (17.3) | ||

| Some of the time | 220 (34.6) | 42 (19.9) | 73 (39.2) | 105 (44.1) | 21 (10.3) | 61 (42.7) | 138 (47.8) | ||

| A little/none of the time | 117 (18.4) | 17 (8.1) | 23 (12.4) | 77 (32.4) | 2 (1.0) | 14 (9.8) | 101 (34.9) | ||

| Current employment status among patients of working age, n (%) | (n=545) | (n=188) | (n=161) | (n=196) | <0.0001 | (n=176) | (n=123) | (n=246) | 0.0001 |

| Employed/Student/Homemaker | 458 (84.0) | 169 (89.9) | 134 (83.2) | 155 (79.1) | 160 (90.9) | 102 (82.9) | 196 (79.7) | ||

| Unemployed/retired not due to condition or unspecified | 25 (4.6) | 15 (8.0) | 25 (15.5) | 22 (11.2) | 16 (9.1) | 18 (14.6) | 28 (11.4) | ||

| Unemployed/retired due to condition | 62 (11.4) | 4 (2.1) | 2 (1.2) | 19 (9.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.4) | 22 (8.9) | ||

| WPAI: Overall Work Impairment, % | (n=319) | (n=117) | (n=98) | (n=104) | (n=113) | (n=73) | (n=133) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 26.9 (25.6) | 8.5 (13.5) | 25.1 (19.1) | 49.4 (24.0) | <0.0001 | 9.5 (12.0) | 28.5 (24.9) | 40.9 (25.7) | <0.0001 |

| WPAI: Presenteeism, % | (n=337) | (n=129) | (n=101) | (n=107) | (n=122) | (n=76) | (n=139) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 24.0 (23.4) | 7.8 (12.6) | 22.0 (16.1) | 45.3 (22.8) | <0.0001 | 8.3 (10.5) | 26.6 (23.2) | 36.3 (23.8) | <0.0001 |

| WPAI: Absenteeism, % | (n=329) | (n=117) | (n=100) | (n=112) | (n=114) | (n=76) | (n=139) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 7.2 (18.4) | 0.5 (2.2) | 5.6 (14.6) | 15.6 (26.2) | <0.0001 | 1.9 (10.7) | 6.2 (17.4) | 12.1 (22.4) | <0.0001 |

| WPAI: Activity Impairment, % | (n=623) | (n=207) | (n=183) | (n=233) | (n=200) | (n=141) | (n=282) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 32.2 (27.4) | 8.9 (12.1) | 27.4 (17.8) | 56.6 (23.0) | <0.0001 | 10.9 (13.6) | 31.3 (23.7) | 47.7 (26.1) | <0.0001 |

Tertiles generated to balance patient numbers between the groups, while still satisfying the definitions of low, moderate and severe pain and fatigue.

BP, bodily pain domain; EQ-5D-3L, 3-level version of 5-dimension EuroQol questionnaire, EQ-VAS, EuroQol visual analogue scale; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; SF-36v2, Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form version 2; VT, vitality; Q, question; WPAI, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire.

Regional SF-36v2 domain scores are presented in online supplementary table 2. The greatest difference in domain scores across regions was in the physical functioning domain, where scores ranged from 32.1 in T&ME to 76.8 in APAC. Scores in T&ME were consistently lower than other regions for all domains with the exception of General Health where the EU5 score was lower.

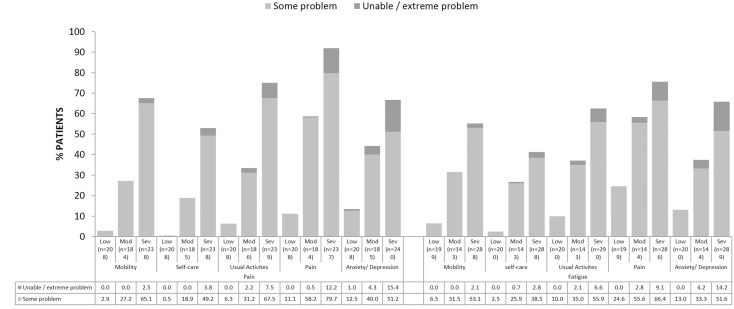

As pain and/or fatigue levels increased from low to moderate to severe, a significantly higher percentage of patients reported ‘some’ or ‘extreme’ problems with mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain and anxiety/depression as measured by the EQ-5D-3L (all p<0.0001) (figure 3). EQ-5D-3L, EQ-visual analogue scale (VAS) and HAQ-DI scores were significantly different across pain and fatigue cohorts (all p<0.0001), with scores lower in patients reporting severe pain and/or fatigue compared with those reporting low pain and/or fatigue (table 2). Regional EQ-5D-3L, EQ-VAS and HAQ-DI scores can be found in online supplementary table 2.

Figure 3.

EQ-5D-3L by pain and/or fatigue levels.

Categories of EQ-5D-3L responses are percentages of patients with (a) no problems, (b) some problems and (c) confined to bed/unable to perform task/extreme problems; only (b) and (c) are shown on the graph. P values across (a), (b) and (c) response categories of EQ-5D-3L for each level of pain and fatigue (low, moderate and severe) are all p<0.0001.

Societal burden by pain and fatigue levels

Of 545 patients of working age (<65 years) who provided employment information, 458 (84.0%) patients were employed, defined as employed, a student or a homemaker (table 2). Employment status differed significantly across pain cohorts (p=0.0001), with lower employment rates (79.1%, 83.2% and 89.9%) and higher unemployment/retirement due to PsA (9.7%, 1.2% and 2.1%) in severe, moderate and low pain cohorts, respectively. Similar results were seen across fatigue cohorts (p=0.0001), with lower employment rate (79.7%, 82.9% and 90.9%) and higher unemployment/retirement due to PsA (8.9%, 2.4% and 0%) in severe, moderate and low fatigue cohorts, respectively. HAQ-DI was significantly different across patients reporting severe, moderate and low pain and fatigue (both p<0.0001) (table 2).

All WPAI measures were significantly different across the pain and fatigue severity cohorts (all p<0.0001), indicating that more severe pain and/or fatigue were associated with greater work impairment, more work time missed and greater impairment while working and during daily activities (table 2). Overall regional results can be found in online supplementary table 2. Regionally, the majority of patients were employed; among employed patients who completed the WPAI questionnaire, the overall work impairment, presenteeism and activity impairment was around 20–30% in N America, EU5 and APAC, and approximately 70% of patients in T&ME. Absenteeism ranged from 0.8% in APAC to 15% in T&ME.

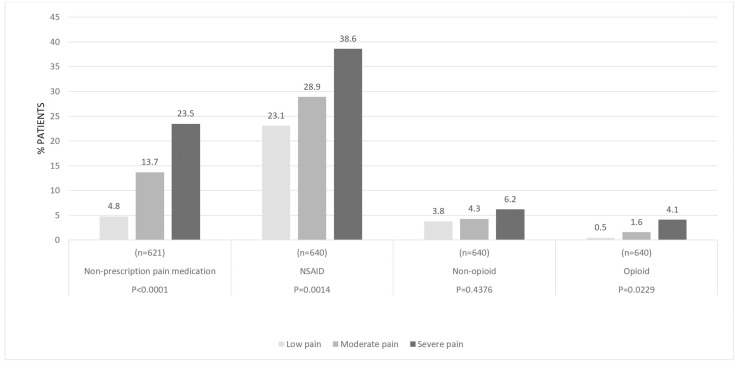

Use of pain medication by pain levels

Globally, the use of non-prescription pain medication, prescribed non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids was significantly different across pain severity cohorts (figure 4). Non-prescription pain medication use was 4.8%, 13.7% and 23.5% (p<0.0001); prescription NSAID use was 23.1%, 28.9% and 38.6% (p=0.0014); and opioid use was 0.5%, 1.6% and 4.1% (p=0.0229) in patients reporting low, moderate and severe pain, respectively.

Figure 4.

Use of pain medication by pain levels.

NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; OTC, over the counter.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first global real-world study of the relationship between pain and/or fatigue with HRQoL and work status in patients with PsA treated with TNFi. We observed that higher levels of pain and/or fatigue were associated with decreased HRQoL, as well as reduced physical functioning, ability to participate in activities of daily living and work productivity. Our results also suggest a discordance between patient-reported pain and/or fatigue and physicians’ assessment of disease control.

Our results are in agreement with other studies that pain is a common complaint in patients with PsA treated with TNFi therapy.8– 10 Patients reporting severe pain also exhibited more severe psoriasis. As pain is a common symptom of psoriasis,30 it may be that the skin-component of PsA, for example, itching, is a contributor to the pain these patients experience. In our study, we observed statistically increased levels of inflammatory markers with greater severity of pain; though these absolute levels were not high, they may indicate that the disease is not under control with the ongoing treatment. We previously reported that even while experiencing a lack of efficacy, switching of TNFi was often delayed in patients with PsA.31 In addition, we observed a higher rate of physician-reported fibromyalgia in patients reporting severe pain and/or severe fatigue, which is consistent with previous reports that patients with PsA often exhibit widespread pain from fibromyalgia and that severe fatigue is common in patients with PsA with co-morbid fibromyalgia.5 32 The prevalence of moderate to severe fatigue in our study (63%) is in line with a previous estimate of fatigue of 57% in this patient population.5

Our study demonstrates that patients reporting severe pain and/or fatigue have reduced HRQoL, impaired ability to work and high rates of unemployment and retirement compared with patients reporting low pain and/or low fatigue. This finding is consistent with a report that overall employment rates are significantly lower in patients with rheumatic diseases than in the general population, especially in those with ankylosing spondylitis and PsA.33– 35 Unemployment and work impairment, including time away from work (absenteeism) or reduced effectiveness at work (presenteeism), affects up to 50% of people with PsA.6 A National Psoriasis Foundation (US) survey found that 49% of respondents routinely missed work due to psoriasis or PsA, with more than 10 workdays per month missed by 31% of those respondents.36 Impaired ability to work impacts HRQoL and is costly to society as a whole.37 38 In the Norwegian (NOR-DMARD) study, the cost of absenteeism in patients with PsA taking bDMARDs over a 2-year period was €111 200.38

A recent study comparing the perceptions of psoriatic disease symptoms in the USA revealed areas of discordance between both patients and physicians, and between rheumatologists and dermatologists, on a comprehensive set of disease symptoms and functional impacts.39 In agreement with this and other studies, we also observed discordance between patient-reported symptoms and physician’s assessment of disease in our global patient sample.39– 41

A major strength of this study is that it presents real-world data in patients with PsA treated with TNFi around the world, and the negative impact on patient’s HRQoL and WPAI associated with pain and/or fatigue despite advanced therapy. However, several potential limitations associated with data derived from this study should be considered. It has been suggested that domains within patient-reported outcome measures are correlated with each other; therefore, analysis between domains within the same outcome measure should be interpreted with caution. Cross-sectional studies are limited in their selection of patients, sample size and data collection. In contrast to a clinical trial where disease activity is assessed by a range of validated measures, physicians’ ratings of disease activity may be considered subjective. However, our study reflects physician practice in a real-world clinical setting where assessments may include a global assessment rather than focusing on disease activity. Another limitation of this study is that it is not possible to determine the impact of undiagnosed fibromyalgia on our results despite observing that overall physician-reported comorbid fibromyalgia levels were low yet increased in the patient groups with high pain and/or fatigue. Also, there is likely variability in clinician and regional sensitivity to, and reporting of, fibromyalgia. Another limitation of our study is that we did not compare pain and/or fatigue in patients with PsA not on TNFi with those on TNFi. While we do show that there is still a major unmet need (continuing pain and/or fatigue) in patients treated with TNFi, there is a possibility that for patients not treated this need is even higher. We did not capture patient-reported details on depression, which is associated with the incidence and severity of disease activity and HRQoL. For the purposes of the analysis, working age was set to patients ≤65 years, meaning that the variable working age by country was not considered. In general, regional results were consistent with global results, with the exception of T&ME, where most outcome measures were worse than those observed in other regions; however, since there was a low sample size in this region (n=38), results for T&ME should be interpreted with caution. Finally, although recall bias is a common limitation of surveys, data in our study were collected at the time of patients’ appointments, thus reducing the likelihood of recall bias.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study is the first global real-world analysis of the relationship between pain and/or fatigue with HRQoL and WPAI in patients with PsA treated with TNFi. Our results show that greater severity of pain and/or fatigue are associated with decreased HRQoL, as well as reduced physical functioning, ability to participate in daily activities and work productivity. Our study confirms previous reports that patients with PsA commonly report pain despite being treated with TNFi.8 The high burden that severe pain and/or fatigue, in spite of TNFi treatment, place on patients in terms of limited function, diminished HRQoL and reduced ability to contribute to society as part of the workforce indicate that these are areas of significant unmet need in the treatment and management of PsA.

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Pain and/or fatigue are significant burdens for people with psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

What does this study add?

This study is the first global real-world analysis of the relationship between pain and/or fatigue with health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and work productivity in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) treated with tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi).

Our results show that greater severity of pain and/or fatigue is associated with decreased HRQoL, as well as reduced physical functioning, ability to participate in daily activities and work productivity.

Our study confirms previous reports that patients with PsA commonly report pain despite being treated with TNFi.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Improved disease management with modern advanced therapies may address the significant burden of pain and/or fatigue associated with reduced HRQoL in people with PsA.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Kate Revill of Adelphi Real World, funded by Novartis Pharma AG. PGC is supported in part by the UK NIHR Leeds Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health. The authors and Novartis would like to thank all patients and physicians who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data; or the creation of new software used in the work; have drafted the work or substantively revised it. All authors have approved the submitted version and agreed to be personally accountable for its integrity.

Funding: This study was supported by Novartis Pharma AG, Switzerland.

Competing interests: PGC has received speakers’ bureau or consulting fees from Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Eli Lilly and Novartis. RA has received grants or research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer Roche and Eli Lilly. AD has received grants or research support from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB Pharma, and consulting fees from Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB Pharma. VS has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celltrion, Corrona LLC, Crescendo Bioscience, EMD Serono, F. Hoffmann-La Roche/Genentech, GSK, Janssen, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Samsung, Sandoz, Sanofi and UCB, and has served on advisory boards for AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, BMS, Celltrion, Crescendo/Myriad Genetics, EMDSerono, Genentech/Roche, GSK, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sandoz, Sanofi and UCB. ES and SB are employees of Adelphi Real World. HT and KKG are shareholders and employees of Novartis. SMJ is a shareholder and employee of Novartis Pharma AG.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Data sharing statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1. Liu J-T, Yeh H-M, Liu S-Y, et al. Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. World J Orthop 2014;5:537–43. 10.5312/wjo.v5.i4.537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lloyd P, Ryan C, Menter A. Psoriatic arthritis: an update. Arthritis 2012;2012:176298 10.1155/2012/176298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reveille JD, Witter JP, Weisman MH. Prevalence of axial spondylarthritis in the United States: estimates from a cross-sectional survey. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:905–10. 10.1002/acr.21621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hukuda S, Minami M, Saito T, et al. Spondyloarthropathies in Japan: Nationwide questionnaire survey performed by the Japan Ankylosing Spondylitis Society. J Rheumatol 2001;28:554–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Overman CL, Kool MB, Da Silva JAP, et al. The prevalence of severe fatigue in rheumatic diseases: an international study. Clin Rheumatol 2016;35:409–15. 10.1007/s10067-015-3035-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Walsh JA, McFadden ML, Morgan MD, et al. Work productivity loss and fatigue in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2014;41:1670–4. 10.3899/jrheum.140259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reygaerts T, Mitrovic S, Fautrel B, et al. Effect of biologics on fatigue in psoriatic arthritis: a systematic literature review with meta-analysis. Joint Bone Spine 2018;85:405–10. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2018.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rahman P, Zummer M, Bessette L, et al. Real-world validation of the minimal disease activity index in psoriatic arthritis: an analysis from a prospective, observational, biological treatment registry. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016619 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Walsh JA, Adejoro O, Chastek B, et al. Treatment patterns among patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with a biologic in the United States: descriptive analyses from an administrative claims database. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2018;1–11. 10.18553/jmcp.2018.17388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhu B, Edson-Heredia E, Gatz JL, et al. Treatment patterns and health care costs for patients with psoriatic arthritis on biologic therapy: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Ther 2013;35:1376–85. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.07.328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Institute For Health and Clinical Excellence health technology appraisal: etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis (review of TA104 and TA125), published May 2009. Available https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta199/documents/psoriatic-arthritis-etanercept-infliximab-golimumab-and-adalimumab-review-final-scope2 (accessed 4 May 2020)

- 12. Kirwan JR, Hewlett S. Patient perspective: reasons and methods for measuring fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2007;34:1171–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim CF, Moalem-Taylor G. Interleukin-17 contributes to neuroinflammation and neuropathic pain following peripheral nerve injury in mice. J Pain 2011;12:370–83. 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang JM, An J. Cytokines, inflammation, and pain. Int Anesthesiol Clin 2007;45:27–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Louati K, Berenbaum F. Fatigue in chronic inflammation - a link to pain pathways. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:254 10.1186/s13075-015-0784-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Baronaite Hansen R, Kavanaugh A. Secukinumab for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2016;12:1027–36. 10.1080/1744666X.2016.1224658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Partsch G, Steiner G, Leeb BF, et al. Highly increased levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and other proinflammatory cytokines in psoriatic arthritis synovial fluid. J Rheumatol 1997;24:518–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Braun J, Sieper J. Ankylosing spondylitis. Lancet 2007;369:1379–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60635-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nash P. Psoriatic arthritis therapy: NSAIDs and traditional DMARDs. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:ii74–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Anderson P, Benford M, Harris N, et al. Real-world physician and patient behaviour across countries: disease-specific programmes: a means to understand. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:3063–72. 10.1185/03007990802457040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. EuroQoL G. EuroQoL: a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ware JE Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). Med Care 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharm 1993;4:353–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Services UDoHaH Summary of the HIPAA privacy rule. 2003. Available http://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/privacysummary.pdf (accessed3 Feb 2020).

- 25. Technology HI Health information technology act. Available https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/hitech_act_excerpt_from_arra_with_index.pdf (accessed 3 Feb 2020).

- 26. Association EPMR European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association (EphMRA) code of conduct 2017; European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association (EphMRA) code of conduct updated January 2017. Available http://www.ephmra.org/Code-of-Conduct-Support (accessed 11 May 2017).

- 27. Ware J. User’s manual for the SF-36v2 health survey. Lincoln (RI), QualityMetric Incorporated; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQoL health states. Med Care 1997;35:1095–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Strand V, Crawford B, Singh J, et al. Use of "spydergrams" to present and interpret SF-36 health-related quality of life data across rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1800–4. 10.1136/ard.2009.115550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Martin ML, Gordon K, Pinto L, et al. The experience of pain and redness in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat 2015;26:401–5. 10.3109/09546634.2014.996514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Alten R, Conaghan PG, Strand V, et al. Unmet needs in psoriatic arthritis patients receiving immunomodulatory therapy: results from a large multinational real-world study. Clin Rheumatol 2019;38:1615–26. 10.1007/s10067-019-04446-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Magrey MN, Antonelli M, James N, et al. High frequency of fibromyalgia in patients with psoriatic arthritis: a pilot study. Arthritis 2013;2013:762921 10.1155/2013/762921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mau W, Listing J, Huscher D, et al. Employment across chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases and comparison with the general population. J Rheumatol 2005;32:721–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gottlieb A, Gratacos J, Dikranian A, et al. Treatment patterns, unmet need, and impact on patient-reported outcomes of psoriatic arthritis in the United States and Europe. Rheumatol Int 2019;39:121–30. 10.1007/s00296-018-4195-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thomsen SF, Skov L, Dodge R, et al. Socioeconomic costs and health inequalities from psoriasis: a cohort study. Dermatology 2019;235:372–9. 10.1159/000499924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Armstrong AW, Schupp C, Wu J, et al. Quality of life and work productivity impairment among psoriasis patients: findings from the national psoriasis foundation survey data 2003–2011. PLoS One 2012;7:e52935 10.1371/journal.pone.0052935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Williams EM, Walker RJ, Faith T, et al. The impact of arthritis and joint pain on individual healthcare expenditures: Findings from the medical expenditure panel survey (MEPS), 2011. Arthritis Res Ther 2017;19:38 10.1186/s13075-017-1230-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kvamme MK, Lie E, Kvien TK, et al. Two-year direct and indirect costs for patients with inflammatory rheumatic joint diseases: data from real-life follow-up of patients in the NOR-DMARD registry. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:1618–27. 10.1093/rheumatology/kes074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Husni ME, Fernandez A, Hauber B, et al. Comparison of US patient, rheumatologist, and dermatologist perceptions of psoriatic disease symptoms: results from the DISCONNECT study. Arthritis Res Ther 2018;20:102 10.1186/s13075-018-1601-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Desthieux C, Granger B, Balanescu AR, et al. Determinants of patient-physician discordance in global assessment in psoriatic arthritis: a multicenter European study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017;69:1606–11. 10.1002/acr.23172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lindstrom Egholm C, Krogh NS, Pincus T, et al. Discordance of global assessments by patient and physician is higher in female than in male patients regardless of the physician’s sex: data on patients with rheumatoid arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis, and psoriatic arthritis from the DANBIO Registry. J Rheumatol 2015;42:1781–5. 10.3899/jrheum.150007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2020-001240s001.pdf (248.6KB, pdf)