Abstract

Background

Despite the benefits of relational continuity of care, particularly for patients with multimorbidity, the traditional model of continuity is changing. Revisiting what patients with ongoing problems want from relational continuity could encourage initiatives to achieve these within a modern healthcare system.

Aim

To examine the attributes of GPs that patients with long-term conditions value most, and which attributes patients believe are facilitated by relational continuity.

Design and setting

Qualitative study in UK general practice.

Method

A thematic analysis was carried out, based on secondary analysis of interviews with 25 patients with long-term conditions that were originally conducted to inform a patient-reported outcome measure for primary care.

Results

Patients with long-term conditions wanted their GPs to be clinically competent, to examine, listen to, care for, and take time with them, irrespective of whether they have seen them before. They believed that relational continuity facilitates a GP knowing their history, giving consistent advice, taking responsibility and action, and trusting and respecting them. Patients acknowledged practical difficulties and safety issues in achieving the first three of these without relational continuity. However, patients felt that GPs should trust and respect them even when continuity was not possible.

Conclusion

Policy initiatives promoting continuity with a GP or healthcare team should continue. Many patients see continuity as a safety issue. When patients experience relationship discontinuity, they often feel that they are not taken seriously or believed by their GP. GPs should therefore consistently seek to visibly demonstrate trust in their patients, particularly when they have not seen them before.

Keywords: continuity of patient care, patient satisfaction, physician–patient relations, primary health care, qualitative research, quality of health care

INTRODUCTION

Continuity of care has traditionally been defined as the ongoing relationship between a practitioner and a patient. This ongoing relationship, referred to by Haggerty as ‘relational continuity’, is distinct from ‘information continuity’ (shared information between providers) and ‘management continuity’ (a consistent approach across providers).1 Longitudinal continuity (seeing the same doctor over time) is often used as a proxy for relational continuity,2 although interpersonal continuity (building a relationship of mutual trust with a single doctor or healthcare team) is also necessary for true relational continuity.3 The concept of relational continuity is adapting to fit the current context, where it is more practical to offer small practice teams, aiming to ensure continuity, with more than one clinician at a time.4

Research shows that relational continuity, despite not being universally preferred by patients,1,5,6 is highly valued by many patient groups,2 and may improve outcomes.2,7 Despite this, relational continuity in the UK has been consistently decreasing since at least 2012,8 because of falling numbers of GPs,9 rising workload, increasing complexity,10 and policies that prioritised access over continuity.11,12 The NHS Long Term Plan has encouraged new models of primary care to deal with the workload crisis, including primary care networks, e-consultations, and task-shifting to free up GP time.13 All of these will affect relational continuity. It is important to identify the benefits that patients associate with relational continuity, in order to seek ways to maintain these benefits within a modern healthcare system.14 This involves, first, characterising what attributes affect patient satisfaction with primary care. Such attributes have variously been described in terms of provider behaviour (for example, technical care, interpersonal care, patient-centredness), organisation and delivery of care (for example, access, continuity), and outcomes.15

Discrete choice experiments (DCEs) have been conducted to identify which attributes are most important for patients. Although results have been inconsistent,16 some studies have shown that patients value the attributes of GP behaviour more than organisational aspects.17,18 However, few, if any, qualitative studies have examined how patients perceive GP attributes and behaviours to be facilitated by continuity of care. Such an analysis can, first, identify how relational continuity (or lack thereof) may affect the patient experience, and, second, explore how any adverse effects can be mitigated within a new model of continuity.

This study details findings from interviews held with primary care patients with long-term conditions on, first, the GP attributes and behaviours that are most important to these patients, and, second, which of these attributes and behaviours they perceive as being affected by relational continuity.

How this fits in

| It is already known that relational continuity of care (seeing the same GP over time) is valued by patients with long-term conditions. This qualitative study identifies that patients believe that relational continuity facilitates having a GP who knows their history, gives consistent advice, takes responsibility and action, and trusts and respects them. The first three of these attributes are difficult to achieve in the absence of continuity. Patients’ perception of GP trust and respect in them appears to be facilitated by relational continuity, but can also be achieved without continuity. This concept of trust and respect involves patients being believed, taken seriously, and respected as experts in their own health and body. Because patients often feel mistrusted and taken less seriously by GPs who do not know them, GPs should particularly seek to visibly demonstrate these aspects of trust and respect to their patients, especially when they do not have relational continuity. |

METHOD

Overall design

The study was a secondary analysis of qualitative data, originally collected to inform a patient-reported outcome measure for primary care.19 In the original interviews, 30 patients and eight clinicians were asked what they valued in consultations. If patients described their experience of provider behaviours, the researcher probed further on how these behaviours affected their outcome. Patients found it easier to talk about GP behaviours than outcome, so there was a substantial amount of data collected on this topic. Patients were also asked if they valued continuity of care, and if they thought it affected their outcomes. Again, because patients found it easier to talk about their experience than health outcomes, some rich data were collected on how patients perceived that relational continuity affected their experience of GP behaviour in the consultation.

Data collection

This study purposefully sampled from five NHS sites in Bristol including three GP practices (with varying levels of deprivation), one walk-in centre, and one GP out-of-hours service. Thirty patients were interviewed, 25 of whom had one or more self-reported long-term conditions, which is broadly in line with the GP waiting room population.20 This paper is based only on the 25 with long-term conditions. Patients were approached by one of the researchers in the waiting rooms of the general practices and the walk-in centre, and were recruited by letter from the GP out-of-hours service provider. Participating patients provided written consent and data about their age, ethnicity, sex, and long-term conditions.

The interviews were conducted face-to-face in patients’ own homes or another location of their choice, or by telephone.

Analysis

The analysis used a qualitative descriptive approach.21,22 This allowed the authors to directly reflect the views of the participants. One researcher analysed the data using thematic analysis, focusing on patients’ preferred provider attributes and behaviours, taking an inductive approach. A second researcher independently read a sample of transcripts to agree the themes, and how they were coded. After agreeing on the thematic analysis, the first researcher then reviewed the transcripts a second time to see which of the attributes and behaviours were identified by patients as being particularly affected by relational continuity, and this was agreed between both researchers before finalising.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows a demographic breakdown of the 25 patients whose interviews were analysed for this study. The age population distribution is representative of the UK GP-registered population.23 Information on long-term conditions was collected by patient self-report. Subject to this limitation, the population distribution is representative of the distribution of GP consultations in patients with long-term conditions.24

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients interviewed

| Characteristic | n |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 13 |

| Male | 12 |

|

| |

| Age range, yearsa | |

| 18–34 | 4 |

| 35–54 | 9 |

| 55–64 | 4 |

| 65–74 | 4 |

| ≥75 | 4 |

|

| |

| Ethnicity | |

| Asian | 1 |

| Black | 3 |

| White | 21 |

|

| |

| Number of long-term conditions | |

| 1 | 13 |

| >1 | 12 |

Because of the increasing number of health problems in older populations, age was captured in 10-year age ranges after the age of 55 years.

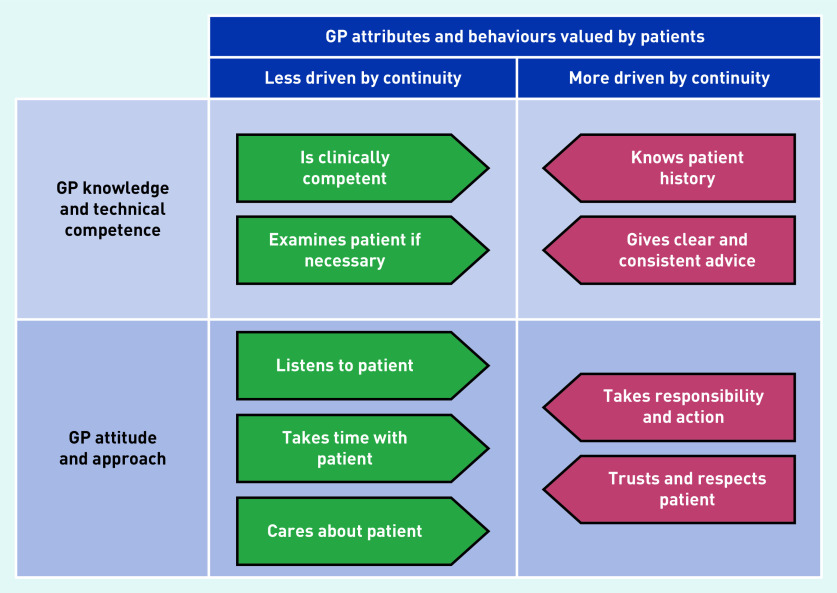

In the qualitative analysis, two overarching themes were identified of patients’ perceptions of GP attitude and approach, and patients’ perceptions of GP knowledge and technical competence. Figure 1 shows the behaviours and attributes of GPs within these categories that patients perceived as the most important, and the attributes that patients perceived as particularly affected by relational continuity.

Figure 1.

Attributes and behaviours of GPs valued by patients with long-term conditions.

Attributes perceived as driven by continuity

Most patients perceived continuity as very important. Although, for some patients, continuity could be achieved with a healthcare team, relational continuity with a single GP was essential for many patients. The attributes and behaviours of GPs that patients perceived as driven by relationship continuity converged on four themes, highlighted below.

GPs knowing patient history

Knowledge of the patient’s history was the attribute most clearly perceived as driven by relational continuity. One patient explained:

‘You don’t have to go through the same stuff over again [with relational continuity] … and having an unusual disability … I think that does also make a difference because you don’t have to try and explain it to yet another person.’

(P10, female [F], 35–54 years, white)

This language of ‘going over the same stuff’ was used by other patients. More than simply an inconvenience, some patients perceived this as a safety issue. One patient with a rare long-term condition described the impact of seeing different doctors:

‘I find with GPs, they’re very good but when you go in there, they haven’t looked up your notes and sometimes they try and give me things that I know I shouldn’t, perhaps, be having.’

(P9, F, 55–64 years, white)

This patient attributed this to the rarity of her condition, and to her receiving secondary, as well as primary, care.

There were some exceptions, where patients believed that informational continuity was sufficient for good care. One patient, with postoperative cancer, explained why he did not prioritise relational continuity:

‘They’re very knowledgeable, they seem to … know my problems, they’ve got it all on computer … I don’t think I got a problem with any of the doctors down there … They seem to know what’s going on.’

(P1, male [M], ≥75 years, white)

However, most patients who raised GP knowledge of their history as important felt it was strongly affected by relational continuity.

GPs giving clear and consistent advice

Patients found inconsistent advice between different GPs disconcerting, and felt that this was often a consequence of discontinuity. One patient explained why she disliked seeing different GPs:

‘Very often, they [other GPs] will criticise a plan of action that you’ve already discussed with your own GP for relevant reasons … There’s an inconsistency.’

(P15, F, 35–54 years, black)

Although there were some exceptions, most patients agreed that clarity and consistency of advice were affected by relational continuity, particularly patients with ongoing problems that had not yet been fully diagnosed.

GPs taking responsibility and action

Patients valued their GPs taking, first, responsibility and, second, action, and many thought this was affected by relational continuity. The word ‘responsibility’ is not intended to imply paternalism, nor override the patient’s responsibility for their own health, but refers to the GP assuming an ongoing duty of care for their patient. The word ‘action’ means taking steps to progress the presenting problem. This could include new prescriptions, advice, referrals, or a ‘wait and see’ approach, set within an overall plan. Indeed, patients often saw the most appropriate action as seeking to understand the problem and developing an ongoing plan rather than a ‘quick fix’ prescription.

Patients experienced situations where a GP seemed unwilling to take responsibility or action, often related to discontinuity. One patient with multiple long-term conditions explained the effect of moving to a practice where continuity was prioritised:

‘Well, the previous [practice], if, like, I was ill, I’d see different doctors, and they, sort of, just wanted me in, straight out, giving me different pills and all that, and, sort of, nothing worked, but then when I changed [practices], I [saw] one doctor, GP, and he just tells me what’s wrong with me and gives me advice, sort of, and it’s quite good.’

(P2, M, 35–54 years, white)

From the patient’s perspective, the new doctor explained things clearly, whereas the patient experienced a lack of engagement and a dismissive attitude from his previous GPs. The patient went on to describe how he perceives his GP as treating him as ‘his’ patient, for whom he has ongoing responsibility. He also explained how the ‘advice’ included self-management, dietary advice, and switching from injecting to tablets, through a process of shared decision making.

Another patient felt that her GP’s knowledge of her history helped him to take responsibility and action:

‘I prefer to see […] my own GP [because otherwise] … the GP don’t understand the complications of my personal circumstances, very often GPs don’t want to listen to… the ongoing issues, they want to be able to … deal with something there and then, within a couple of minutes … GPs that don’t know you well and the situation well, are not willing to … act.’

(P15, F, 35–54 years, black)

The patient’s perception was that, when relational continuity was broken, the GP sought to deal with the presenting problem as quickly as possible, without addressing ongoing problems. The patient acknowledged that this is partly down to issues of time and patient safety; valuable consultation time is spent re-explaining the problem and the GP does not understand her clinical history sufficiently to safely take action.

Patients were also aware of the risks in relational continuity; some patients perceived that over-familiarisation prevented GPs from taking necessary action, for example, a change of medication or a referral. One patient, with multiple long-term conditions, prioritised relational continuity of care for years, but felt that more decisive action occurred when she changed GPs.

‘Like, I’m in pain … “Oh, I’ll give her tramadol, that’ll knock her out, that’ll shut her up.” [Laughs] … I don’t know. I just feel that I’ve had a better service by moving to see somebody else … Because, I think, he’s used to me coming through the door and thinking “Oh, it’s her again” … but, if I go to somebody new, they’re looking at me afresh.’

(P16, F, 35–54 years, white)

This patient felt that relational continuity of care had perpetuated the same management, despite it not working for her.

GP trust and respect in the patient

GP trust and respect in the patient was frequently raised as of key importance. The concept of trust and respect explored here (which is the patient’s perception of GP trust and respect, not necessarily the GPs’ intentions) involved three related aspects: first, the patient perceiving that they are believed; second, the patient perceiving that their problems have been taken seriously, rather than minimised; and, third, the patient perceiving that the GP has respect for their expertise in their own health and body.

The first aspect described was belief. Several patients felt that their GP simply disbelieved them.

‘Sometimes they [doctors] sort of listen to what is said and then they kind of, in a way, … halve it for seriousness or for accuracy.’

(P8, F, 65–74 years, white)

This patient described this as a characteristic of ‘some doctors’, but suggested it happens more when continuity is broken. Another patient similarly described feeling disbelieved after seeing different doctors for the same recurring problem:

‘I think it is true that if you go to the same doctor and you say to them, “Oh, the thing you gave me last week didn’t work.” They’d actually believe you … While sometimes they just don’t believe you in a way, you know.’

(P20, F, 18–34 years, white)

The second aspect of trust was patients perceiving their problems being taken seriously. One female patient who had a long-term condition with a physical and mental component said:

‘I don’t like being brushed aside as being … neurotic or something like that, erm. I think it occurs more with doctors that don’t really know you … I mean, there’s a trust issue, isn’t there? You have to have a trust, erm going on between you and the practitioner.’

(P10, F, 35–54 years, white)

This patient’s experience of being ‘brushed aside’ occurred more often with discontinuity. She explicitly described ‘trust’ as being built up through relational continuity. However, although she talked about mutual trust, her examples were about her perception of the GP’s trust in her. Other patients agreed that discontinuity resulted in their problems being minimised. One female patient explained the effects of seeing a different doctor thus:

‘I think they don’t have a feel for either me as a patient, they don’t know me, whether I’m … somebody who wimps about something little, or I’m seriously only come for really bad things.’

(P17, F, 55–64 years, white)

The third aspect of trust identified was GPs trusting patients as experts on their own health and body.

For example, one patient, who had seen different GPs for pain following his third back surgery, and was ultimately found to have an infection, felt the GPs did not respect his knowledge and experience of his own symptoms:

‘I think they were going on assumptions that because I’d had … a discectomy and a laminectomy … there is muscular pain, as it all heals and then tightens up … but I was trying to explain to them that that wasn’t the pain. And I know the difference, and they just weren’t really having it.’

(P3, M, 35–54 years, white)

This patient felt that his understanding of his own body was not respected or trusted by health professionals. He acknowledged that, because he had been in a lot of pain, he had prioritised access over continuity. When asked if he felt continuity made a difference, he said:

‘If I did see the person over time, they would … probably get some picture of my ability to understand what’s wrong with me … that’s probably really irritating to GPs, that people come in that self-diagnose, but if you’ve got a long-term condition, you kind of get an idea of … what’s normal and what’s not normal.’

(P3, M, 35–54 years, white)

Many patients perceived that trust and respect from their GP is particularly affected by relational continuity. However, there were some patients who felt that their GP trusted and respected them even without continuity. P3 described how, before his last surgery, he had seen various GPs before the protruding disc was diagnosed. The GPs explained that the symptoms were likely a weakness from his previous operation, until one GP took his problems seriously.

‘I got a sense that she … that when I said, “Look, it’s really painful and I know pain because I’ve had lots of back problems, I know what that pain’s like and … this is really … this is really bad” … I felt when I left, thank God, she … she realises this is something different.’

(P3, M, 35–54 years, white)

A young female similarly described repeatedly consulting GPs with anxiety and depression, but the extent of her illness was downplayed, until she connected with her current GP:

‘I was going to leave that surgery because I was so fed up and then I just walked in, in a real state and saw anyone … she didn’t make me feel stupid, or like I was being over the top or anything like that … which I’ve had before, people just, sort of, be like, “Oh you’ll get over it”, I’ve been dealing with … anxiety and this sort for over 10 years. So, you know, if it was just something that would pass, I’d know.’

(P18, F, 18–34 years, white)

Both of these patients felt an immediate connection with a GP, who they felt respected their understanding of their own conditions. The examples show that, although patients are more likely to perceive that their GP trusts and respects them when they have continuity, they can also perceive it at a first consultation. This differs slightly from the other three attributes that patients saw as driven by relational continuity, in that patients believed it was possible for GPs to trust and respect them even without continuity, whereas patients acknowledged practical problems and safety issues with GPs knowing their history, giving consistent advice, and taking responsibility and action without continuity.

Attributes perceived as less driven by continuity

Several attributes of a GP were important to patients, including listening, taking time, and caring (GP approach), and clinical competence and performing an examination (GP knowledge and expertise). However, patients perceived these as less directly affected by relational continuity. Instead they saw these as traits/practices inherent to a particular doctor. Although patients who had good relational continuity did often perceive their usual doctor to listen, take time, and care, the distinction was that these patients sought continuity of care with doctors who they perceived as possessing these important traits, rather than seeing them as attributes and behaviours that are driven by continuity.

GP attitude and approach

Of these attributes and behaviours, listening was the one most frequently raised as important. One patient explained:

‘Doctor P is like that … He will sit back and listen to you … he won’t be playing on his computer … and that’s, that’s, to me, is 90 per cent of it, is listening to what you’ve got to say.’

(P14, M, 65–74 years, white)

The patient describes a doctor who not only listens, but is also seen by the patient to be listening, for example, by not ‘playing’ on his computer. The patient described the doctor as ‘like that’, seeing his listening skills as an inherent quality rather than driven by the doctor–patient relationship.

‘Taking time’ was also consistently seen as an important GP behaviour and patients preferred to see GPs who were prepared to spend time:

‘I do like to see the same one if I can, even though it’ s quite hard to get, but he is good, and it’ s like he’ s got time for you, some of them … As you get in there, ’it s like you haven’ t even finished writing your prescription, and then you’ re finished, you know.’

(P22, F, 18–34 years, black)

As with listening, this patient preferred continuity because of the GP’s approach of having ‘time for you’, but saw this as a characteristic of this GP and the reason she sought continuity with him, rather than being facilitated through continuity.

The last attribute in this category that patients found important was that their GP cared for them. Patient opinion varied as to the extent to which continuity of care influenced this. Some patients felt that they had a strong relationship with their GP, which had built up over time and was strengthened by continuity of care. Patients used words such as ‘caring’, ‘empathy’, and ‘a good friend’ to describe such clinicians. However, although patients saw continuity as strengthening the doctor–patient relationship, most patients perceived ‘caring’ as a character trait. For example:

‘He’ s a great guy.’

(P14, M, 65–74 years, white)

‘In the past, ’I ve seen some not very nice doctors who have sort of implied that’I m being a drama queen and that I should just get on with it.’

(P18, F, 18–34 years, white)

Although both these patients valued the doctor–patient relationship, and perceived it as being built over time, their descriptions (‘a great guy’ and ‘not very nice’ doctors) are of character traits inherent within the doctor, rather than driven by continuity of care.

GP knowledge and technical competence

Performing an examination (where necessary) and clinical competence were important to patients, but not perceived as being driven by continuity. These attributes and behaviours were raised much less frequently than those related to GP attitude and approach.

DISCUSSION

Summary

Key GP attributes that patients prioritised were categorised into five attitude- and approach-related attributes, and four knowledge- and competence-related attributes (Figure 1). Patients focused mostly on the importance of attitude and approach, with listening, trust and respect, and taking responsibility and action being the three most important. Patients felt that GP demonstration of trust and respect, taking responsibility and action, knowledge of their history, and giving clear and consistent advice were mostly strongly affected by relational continuity. Patients felt that the other attributes, including having a GP who listened to them, were largely driven by the inherent traits of a particular doctor and thus less affected by relational continuity. However, patients would seek continuity with GPs who they perceived as possessing these traits.

Strengths and limitations

This study used rigorous methods of qualitative data collection and analysis. The findings are grounded in data from a maximum variation sample of patients; coding was carried out iteratively and inductively, and reviewed by a second researcher. The maximum-variation sample is representative of the UK GP-registered population in terms of age23 and the UK GP consultation distribution for number of long-term conditions.24

This study has some limitations. The framework that was developed (Figure 1) is not the only framework possible for preferred provider attributes and behaviours. As with many other qualitative studies, the sample was self-selecting, limited to people approached who agreed to an interview, and this may have influenced the findings. This was a secondary analysis; the original research question was about patient outcomes, not relational continuity and the patient experience; the data may have been richer if this had been the study objective. Furthermore, the patients were recruited from a narrow geographical area following a consultation. Although patients were asked to also recall previous consultations, the findings may have been unduly influenced by the most recent consultation, including whether the patient had relational continuity with the consulted GP.

Because of the limits of the available data, this study took a single perspective, that is, what GP attributes and behaviours patients associate with continuity. However, the advantages and disadvantages of continuity are much wider than this and include, for example, increased patient trust in GP and improved communication. Nonetheless, the single perspective focus contributes to knowledge in the field, and the findings are consistent with and complementary to previous research.

Comparison with existing literature

Qualitative research has already been carried out to establish patient priorities in primary care. The themes identified in the current study overlap with some models of patient-centred care25,26 and with measures of GP empathy,27 but also differ from these in that they are described entirely in terms of GP behaviours and attributes.

Listening was the most important attribute, which was consistent with previous qualitative research.28 However, this prioritisation of clinician attitude and approach was in contrast with DCEs that show that patients prioritise clinical competence over approach.17 As other researchers have noted, this may suggest that patients take clinical competence for granted, rather than they don’t value it,17 which is corroborated by the fact that primary care patients do have high levels of trust in the clinical competence of their GPs.29

In the current study the authors explored patient perceptions of GP trust and respect in them, rather than asking GPs directly how much they trusted and respected their patients. In a qualitative synthesis of studies on the doctor–patient depth of relationship, Ridd et al also found that patients’ perceptions of their doctor’s trust in them were associated with feelings of being believed, and that patients felt mistrusted if their symptoms were minimised or not taken seriously.30 Patients with medically unexplained symptoms have consistently described feeling that their GP does not believe them, or minimises their problems.31 This study found that a wide range of people with long-term conditions have a similar experience, in particular, where there is relational discontinuity. Trust is often credited as being built through relational continuity.2 However, although the association between relational continuity and trust has been widely explored, the concept of trust has almost always been the patient trust in the clinician, even where a study purports to explore mutual trust.32,33 In 2013, a systematic review of clinician–patient trust found only one study where the explicit focus was GP trust in patients,34 and one further study has since explored this.35

Implications for practice

In the current context, where achieving relational continuity is becoming increasingly difficult, it is relevant to revisit why primary care patients with ongoing problems want relational continuity. Continuity appears to be a means to several ends, and not an end in itself. Even without relational continuity, patients can perceive their GP as trusting them, and respecting them as experts in their own health. There have been a number of calls for policy initiatives to promote relational continuity,11 which should continue. This study confirms that many patients rightly see relational continuity as a safety issue; relational continuity enables the GP to become a repository of information, acquire specialist knowledge of a patient’s condition, become familiar with the patient’s consulting behaviour, and foster trust.36 However, given that impediments to traditional relational continuity seem set to continue, GPs should be aware that patients often feel that they are not taken sufficiently seriously or believed by GPs who do not know them. GPs should, therefore, consistently seek to visibly demonstrate trust and respect in their patients, particularly when they have not seen them before.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants in this study, the Bristol Primary Care Research Network for assisting with recruiting the participants, and the NIHR SPCR for funding the research.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care Research (NIHR SPCR) through a post-doctoral fellowship. Mairead Murphy received funding from Bristol, North Somerset and South Gloucestershire Clinical Commissioning Group (BNSSG CCG; BNSSG CCG: 17/18-10A) to carry out the secondary analysis and write the paper. Chris Salisbury receives support from BNSSG CCG and as an NIHR Senior Investigator. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Ethical approval

This study received ethical approval from the committee of Nottingham 1 National Research Ethics Service, REC reference 13/EM/0197.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, et al. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. BMJ. 2003 doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7425.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman G, Hughes J. Continuity of care and the patient experience. London: King’s Fund; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saultz JW. Defining and measuring interpersonal continuity of care. Ann Fam Med. 2003 doi: 10.1370/afm.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engamba SA, Steel N, Howe A, Bachman M. Tackling multimorbidity in primary care: is relational continuity the missing ingredient? Br J Gen Pract. 2019 doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X701201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Pandhi N, Saultz JW. Patients’ perceptions of interpersonal continuity of care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(4):390–397. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.4.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliver D, Deal K, Howard M, et al. Patient trade-offs between continuity and access in primary care interprofessional teaching clinics in Canada: a cross-sectional survey using discrete choice experiment. BMJ Open. 2019 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pereira Gray DJ, Sidaway-Lee K, White E, et al. Continuity of care with doctors — a matter of life and death? A systematic review of continuity of care and mortality. BMJ Open. 2018 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levene LS, Baker R, Walker N, et al. Predicting declines in perceived relationship continuity using practice deprivation scores: a longitudinal study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2018 doi: 10.3399/bjgp18X696209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Beech J, Bottery S, Charlesworth A, et al. Closing the gap: key areas for action on the health and care workforce. Health Foundation, King’s Fund, and Nuffield Trust; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hobbs FD, Bankhead C, Mukhtar T, et al. Clinical workload in UK primary care: a retrospective analysis of 100 million consultations in England, 2007–14. Lancet. 2016 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00620-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tammes P, Salisbury C. Continuity of primary care matters and should be protected. BMJ. 2017 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NHS England Next Steps on the NHS Five Year Forward View. 2017 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1678. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NEXT-STEPS-ON-THE-NHS-FIVE-YEAR-FORWARD-VIEW.pdf (accessed 30 July 2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.NHS England The NHS long term plan. 2019 https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/nhs-long-term-plan-june-2019.pdf (accessed 21 May 2020).

- 14.Wright M, Mainous A. Can continuity of care in primary care be sustained in the modern health system? Aust J Gen Pract. 2018 doi: 10.31128/AJGP-06-18-4618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheraghi-Sohi S, Bower P, Mead N, et al. What are the key attributes of primary care for patients? Building a conceptual ‘map’ of patient preferences. Health Expect. 2006 doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kleij K-S, Tangermann U, Amelung VE, Karuth C. Patients’ preferences for primary health care — a systematic literature review of discrete choice experiments. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017 doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2433-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheraghi-Sohi S, Hole AR, Mead N, et al. What patients want from primary care consultations: a discrete choice experiment to identify patients’ priorities. Ann Fam Med. 2008 doi: 10.1370/afm.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paddison CA, Abel GA, Roland MO, et al. Drivers of overall satisfaction with primary care: evidence from the English General Practice Patient Survey. Health Expect. 2015 doi: 10.1111/hex.12081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy M, Hollinghurst S, Turner K, Salisbury C. Patient and practitioners’ views on the most important outcomes arising from primary care consultations: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2015 doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0323-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stafford M, Steventon A, Thorlby R, et al. Understanding the health care needs of people with multiple health conditions. Health Foundation; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandelowski M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health. 2010 doi: 10.1002/nur.20362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000 doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.NHS Digital Patients registered at a GP practice (as at: 01 Sept 2019): Interactive Dashboard, 2019

- 24.Salisbury C, Johnson L, Purdy S, et al. Epidemiology and impact of multimorbidity in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract. 2011 doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X548929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med. 2000 doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart M. Towards a global definition of patient centred care. BMJ. 2001 doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7284.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mercer SW, Maxwell M, Heaney D, Watt GC. The consultation and relational empathy (CARE) measure: development and preliminary validation and reliability of an empathy-based consultation process measure. Fam Pract. 2004 doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jagosh J, Donald Boudreau J, Steinert Y, et al. The importance of physician listening from the patients’ perspective: enhancing diagnosis, healing, and the doctor–patient relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iacobucci G. Trust in GPs remains high but patients report more difficulties getting an appointment. BMJ. 2018 doi: 10.1136/bmj.k3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ridd M, Shaw A, Lewis G, Salisbury C. The patient–doctor relationship: a synthesis of the qualitative literature on patients’ perspectives. Br J Gen Pract. 2009 doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X420248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Peters S, Rogers A, Salmon P, et al. What do patients choose to tell their doctors? Qualitative analysis of potential barriers to reattributing medically unexplained symptoms. J Gen Intern Med. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0872-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baker R, Mainous AG, Gray DP, Love MM. Exploration of the relationship between continuity, trust in regular doctors and patient satisfaction with consultations with family doctors. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2003 doi: 10.1080/0283430310000528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamano J, Morita T, Fukui S, et al. Trust in physicians, continuity and coordination of care, and quality of death in patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2017 doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brennan N, Barnes R, Calnan M, et al. Trust in the health-care provider–patient relationship: a systematic mapping review of the evidence base. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013 doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzt063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sagsveen E, Rise MB, Gronning K, et al. Respect, trust and continuity: a qualitative study exploring service users’ experience of involvement at a healthy life centre in Norway. Health Expect. 2019 doi: 10.1111/hex.12846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rhodes P, Sanders C, Campbell S. Relationship continuity: when and why do primary care patients think it is safer? Br J Gen Pract. 2014 doi: 10.3399/bjgp14X682825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]