Abstract

Background

Time in general practice offers medical students opportunities to learn a breadth of clinical knowledge and skills relevant to their future clinical practice. Undergraduate experiences shape career decisions and current recommendations are that 25% of undergraduate curriculum time should be focused on general practice. However, previous work demonstrated that GP teaching had plateaued or reduced in UK medical schools. Therefore, an up-to-date description of undergraduate GP teaching is timely.

Aim

To describe the current picture of UK undergraduate GP teaching, including the amount of time and resources allocated to GP teaching.

Design and setting

A cross-sectional questionnaire study across 36 UK medical schools.

Method

The questionnaire was designed based on a previous survey performed in 2011–2013, with additional questions on human and financial support allocated to GP teaching. The questionnaire was piloted and revised prior to distribution to leads of undergraduate GP teaching in UK medical schools.

Results

The questionnaire response rate was 100%. GP teaching constituted an average of 9.2% of medical curricula; this was lower than previous figures, though the actual number of GP sessions has remained static. The majority (n = 23) describe plans to increase GP teaching in their local curricula over the next 5 years. UK-wide average payment was 55.60 GBP/student/session of in-practice teaching, falling well below estimated costs to practices. Allocation of human resources was varied.

Conclusion

Undergraduate GP teaching provision has plateaued since 2000 and falls short of national recommendations. Chronic underinvestment in GP teaching persists at a time when teaching is expected to increase. Both aspects need to be addressed to facilitate high-quality undergraduate GP teaching and promotion of the expert medical generalist role.

Keywords: cost, general practice, medical students, primary health care, teaching, workforce

INTRODUCTION

General practice is the bedrock of the NHS1 and a core component of UK undergraduate medical school curricula. It is an ideal setting for students to learn clinical and communication skills in the context of holistic patient-centred care.2 Learning from GPs as expert medical generalists provides medical students with valuable lessons about managing uncertainty, health promotion, disease prevention, multimorbidity, continuity of care, and NHS organisation.3 Undergraduate teaching in general practice fosters students’ abilities to deliver integrated care for complex patients with multimorbidity outside of the hospital context, shifting focus from specialist to generalist care, as recommended by General Medical Council (GMC) and Shape of Training reports.4,5

However, general practice is under pressure. Government responses to the workforce crisis in the UK include a target of 50% of medical graduates choosing to enter GP training,6 but current trends indicate the proportion is far lower.7 There is a shortage of GPs in many health economies globally.8,9 While career specialty decision making is complex and not fully understood, specialty perceptions are a key component, themselves influenced by medical school experiences, in particular exposure to role models and clinical placements.10–12 International evidence shows that students are positively influenced towards a career in general practice by undergraduate GP placements.13

Across the UK, the number of medical schools and medical student places has increased over the past two decades,14–18 and curricula have evolved in response to changing GMC guidance.4 Current trends in medical education promote a transition to undergraduate curricula becoming more community focused,4,19 yet previous work has shown the amount of GP teaching has plateaued or even reduced.20 GP teaching remains subject to local tariff arrangements, resulting in funding that is variable both regionally and across the four nations, and considerably less than actual teaching costs.21–23 Given this complex and changing landscape, and the recruitment issues for general practice, it is now vital to consider issues of quantity and resources in relation to undergraduate GP teaching.

A survey of all UK medical schools was undertaken in order to describe the current national picture of undergraduate GP teaching in UK medical schools, which specifically aimed to:

quantify the exposure of undergraduate medical students in the UK to general practice;

compare this with historical data; and

describe the financial and human resources allocated to support GP teaching.

How this fits in

| Undergraduate GP teaching offers high-quality, clinically focused tuition, promoting generalism in medicine and encouraging students to consider a possible career in general practice. Changing patient needs have resulted in a move towards more generalist, community-based care and prompted calls to focus undergraduate curricula more on community-based learning. However, this study shows that the amount of GP teaching in UK medical curricula is static or even falling, and that investment is variable and inadequate to maintain or expand GP teaching. Unless curriculum priorities change and there is adequate investment in GP teaching, outcomes necessary to meet future population health needs are unlikely to be met. |

METHOD

Design

The questionnaire was designed by the authors (Supplementary Appendix S1), with input from the Heads of GP Teaching (HoTs) Group at the Society for Academic Primary Care. Questions were based on a previous survey published in 201520 and new ideas generated by the HoTs Group. The questionnaire also contained questions based on the By Choice — Not by Chance report’s recommendations;24 thus these results are reported in detail elsewhere.

To elicit precise data on the amount of GP teaching in curricula, responders were asked to provide granular detail on the number of sessions of GP teaching by each curriculum year, including:

GP teaching delivered in the GP setting;

GP teaching delivered by GPs outside the general practice setting, for example, seminars and classroom teaching; and

optional GP teaching, for example, electives and student-selected components.

Teaching time across the entire curriculum was calculated using the number of sessions per week and the number of weeks per curriculum year, with a session assumed to last 3.5 hours based on discussion with representatives from a variety of medical schools. Responders were asked to exclude revision and assessment weeks. The curriculum was not divided into ‘pre-clinical’ and ‘clinical’ stages, as such distinctions were considered to be no longer applicable given the current aim of undergraduate curricula to give students early clinical experience.

An initial draft of the questionnaire was revised on the basis of an internal pilot with four potential responders and again after discussion at a meeting of the HoTs Group. Revisions comprised rewording of questions to increase validity, for example, by defining the exact nature of a teaching session.

Distribution

Email invitations to complete the survey were sent to leads for GP teaching at all UK medical schools with an active cohort of medical students during the academic year 2017–2018. An active cohort was defined as there being medical students enrolled and studying on the course; therefore, this included recently opened medical schools who had not yet produced graduates by the academic year 2017–2018, and excluded schools whose first cohort of students began in September 2018.

A password-protected online survey tool (Online Surveys, www.onlinesurveys.ac.uk) was used. Two email reminders were sent 1 month apart. When necessary, the lead researcher sought clarification of individual submitted data for specific questions only, for example, if data suggested that a question had been misinterpreted.

Analysis

For the purposes of investigating the amount of GP teaching in the overall curriculum, 32 of 36 medical schools were included for analysis. Four schools were excluded as they were not yet producing graduates at the time of the survey. All 36 schools were included for analysis in the data relating to financial and human resources allocated to GP teaching, as well as the perceived trends in GP teaching.

Microsoft Excel was used for basic calculations, and IBM SPSS Statistics (version 24) for detailed statistical analysis. To augment the basic statistics gained from the survey, detailed statistical analysis was conducted to investigate associations between the data and medical school characteristics, including the location and age of medical schools. ‘Older’ and ‘newer’ schools were defined as those established before and since the year 2000, respectively, given the expansion in UK medical schools since 2000.

Member checking was undertaken: interim results were shared and discussed with responders at a HoTs meeting in July 2019. Following this discussion, responders were given the opportunity to revise responses that were incomplete or inaccurate because of inconsistency in question interpretation. Only three schools needed to amend responses because of inaccuracy in their original response, for instance, by giving daily payment rates for GP teaching when the question asked for sessional payment rates.

RESULTS

All (n = 36/36) UK medical schools with an active cohort of medical students for the academic year 2017–2018 completed the questionnaire between December 2018 and February 2019. The median is reported as the measure of average owing to data skew.

Amount of GP teaching

Percentage of the curriculum

Of the 32 included schools, the median proportion of medical curriculum assigned to GP teaching was 9.2%, with a wide variation from 3.9% to 19.0%. There was no significant difference in the percentage of GP teaching based on a school’s location (England versus devolved nations; north versus south). However, the percentage of GP teaching in ‘older’ medical schools was significantly lower than that in ‘newer’ medical schools (Mann–Whitney U test: median = 8.3% versus 12.9%; U = 168.0; P = 0.006).

Total number of sessions delivered

In the 32 included schools, the median number of sessions of GP teaching delivered was 144, equivalent to 14.5 to 16 weeks teaching over the entire course. The variation between schools was again significant: a range of 65 to 313 sessions of teaching.

Practice-based versus out-of-practice teaching

Across the 32 included schools, the median number of sessions of GP teaching in practice was 108, forming 7.0% of the entire curriculum. The trend was for a small amount of practice-based GP teaching in years 1 and 2 (2.1% and 3.0%, respectively), increasing in years 3, 4, and 5 to 7.7%, 8.3%, and 10.5%, respectively. The reverse was true for teaching delivered by GPs out of practice, with a larger proportion delivered earlier in the course.

Compulsory versus optional GP teaching

Although the majority of schools (n = 30/32) reported some optional GP teaching, such as student-selected components or electives, this was typically on a small scale or only undertaken by a small number of students.

Comparison with historical trends

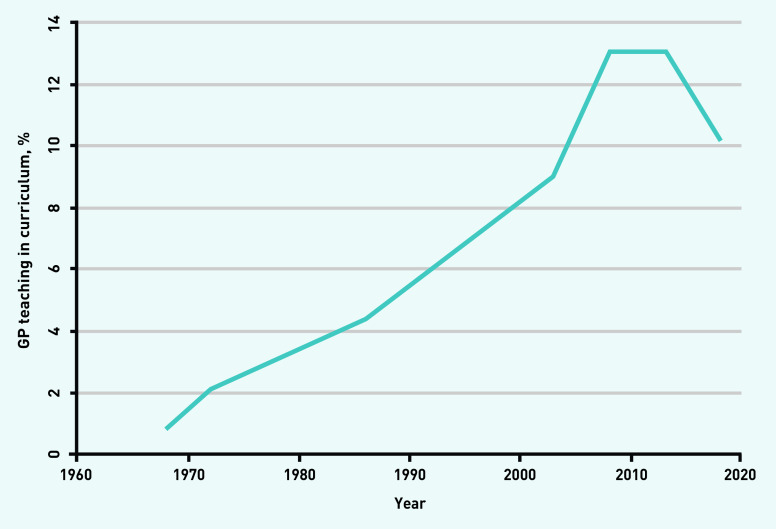

The percentage of GP teaching appears to be declining: from 13.0% in Harding et al‘s 2015 study20 to 9.2% in the present one. However, different methods have been used historically to measure GP teaching, such as measuring GP teaching only in the clinical curriculum.20 If the final 3 years of medical school are taken as a proxy for the ‘clinical’ years, the percentage of GP teaching still appears to be decreasing; using this definition in this study, 10.2% of the clinical curriculum was taught in general practice or by GPs. For a comparison with previous surveys, based on years 3–5 as a proxy for the clinical curriculum in the included 32 medical schools, see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Average percentage of undergraduate clinical curriculum taught in general practice, or by a GP.

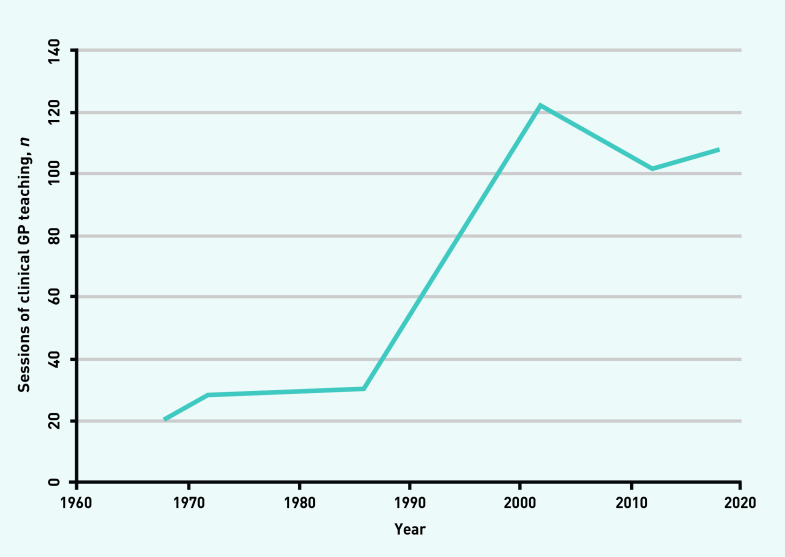

The number of sessions of clinical GP teaching appears stable, with 108 sessions of practice-based GP teaching across the entire curriculum in 2018 (Figure 2) compared to Harding et al‘s 102 sessions.20

Figure 2.

Historical and current trend of clinical GP teaching.

Reported trends in GP teaching

In 36 UK medical schools, the HoTs Group perceived that GP teaching in the curriculum has generally increased (n = 21/36) or remained stable (n = 9/36) over the past 5 years. The majority (n = 23/36) describe plans to increase GP teaching in their local curricula over the next 5 years, with only two schools anticipating a decrease.

Financial resources allocated to GP teaching

All 36 medical schools provided financial information regarding funding for GP teaching. The average payment was 55.60 GBP/student/session of practice-based GP teaching. The variation between schools was marked, ranging from 32.21 GBP to 120.00 GBP/student/session. One-quarter of schools provided the same payment per student per session regardless of the curriculum year and placement expectations. The payment rates offered in ‘newer’ medical schools were significantly higher than those offered in ‘older’ medical schools (Mann–Whitney U test: median = 62.95 GBP versus 51.31 GBP; U = 230.0; P = 0.003). Funding beyond the immediate costs of teaching students was unusual. The majority of schools were not able to invest in GP premises to encourage expansion of teaching (n = 32/36), and the majority do not plan to increase funding for GP teaching in the next 5 years (n = 22/36). Many of those who do plan to increase funding state that this is dependent on increases in funding nationally.

Human resources allocated to GP teaching

Academic general practice faculty and administrative support

Academic general practice faculty time and administrative support allocated to GP teaching varies considerably: mean total academic general practice faculty time was 2.6 whole-time equivalent (WTE) (range: 1.1 to 11.4) and administrative support allocated to GP teaching was 2.4 WTE (range: 0.6 to 14.0).

Recruitment

Recruitment was a mixed picture: 11.1% of medical schools (n = 4/36) found it difficult to recruit campus-based GP teachers, whereas 77.8% (n = 28/36) described difficulty in recruiting GP teaching practices. Cited reasons for this include increasing service demands on general practice staff (n = 6/36), increasing student numbers (n = 5/36), increasing GP teaching creating a demand–supply imbalance of GP teaching practices (n = 3/36), competition for teaching practices in areas where medical schools’ localities overlap (n = 5/36), and poor remuneration for in-practice teaching (n = 1/36).

DISCUSSION

Summary

GP teaching constitutes 9.2% of medical curricula in the UK. The majority of GP teaching (108 of 144 sessions) was practice based, equivalent to 11–12 weeks. Compared with historical trends, the amount of GP teaching was static or reducing. Average funding for practice-based GP teaching was 55.60 GBP/student/session. Considerable variation exists between UK medical schools in the amount of GP teaching, payment for practice-based GP teaching, and human resources allocated to GP teaching.

Strengths and limitations

The 100% response rate combined with the specific, detailed questions about GP teaching in the questionnaire suggest that this study gives the most accurate representation of GP teaching to date. It is also the first UK-wide description of funding made available by all medical schools of practice-based GP teaching.

As curricula are continually evolving, this study provides a snapshot only. This work focuses on the quantity of GP teaching; it cannot provide data on the quality of teaching, nor on other types of community-based teaching that may be increasing. Staffing calculations assume alignment between funding sources and allocated activities; however, staff may undertake roles supporting both GP teaching and other teaching. Measuring the amount of all GP teaching in the entire curriculum has made the reliability of comparisons to historical data limited because of previous methods being unclear or different from those used in this study.20

The percentage of curriculum spent in general practice does not assume that the remainder of the curriculum is dedicated to hospital-based specialties. The significance of GP representation would be enhanced by comparative data on other specialties, as well as data on teaching in other primary care or community settings that may be expanding.

Finally, the authors acknowledge that this discussion focuses entirely on UK medical schools. The international picture is unfortunately even more variable and challenging, for example, in Brekke et al’s 2013 study25 of 400 medical schools in 39 European countries, many schools had only very brief exposure to general practice, and 13.5% had none at all.

Comparison with existing literature

The proportion of undergraduate curricula dedicated to GP teaching appears to be falling, contrasting with the perception of most participants that the GP teaching in their curricula has increased over the last 5 years. A number of factors may explain this apparent discrepancy.

Differences in the methods of calculating GP teaching historically may obscure the trend: previous surveys asked individual medical schools to calculate the percentage of GP teaching themselves,20,26 whereas this survey produced more standardised and granular results by calculating the percentage from detailed data requested from medical schools.

Alternatively, GP teaching may truly be falling, with widely discussed proposals for expansion not materialising in reality. Recruitment difficulties, reported here and in the literature,27 alongside inadequate remuneration for teaching, are likely to be contributors.

The perceptions held by leads of undergraduate GP teaching that teaching is either increasing or static contradict the survey’s quantitative findings. This may be a result of increasing student numbers necessitating increasing delivery of GP teaching from a medical school perspective, but without translating to an increase in GP teaching experienced by individual students. Other possible explanations are that the increased focus on GP teaching gives the impression of a greater volume of teaching, or of an impending increase in teaching in new curricula, which has not been captured in this survey.

It is clear that GP teaching is not expanding as recommended by academics, the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP), the GMC, the NHS Chief Executive, and the Scottish Government.3,4,20,23,28,29 This threatens the future medical workforce, given the importance of students gaining sufficient experience in general practice to understand primary health care, gain medical generalist skills, and to consider a career in general practice.11,12 The lack of expansion of GP teaching also undermines building a medical workforce for sustainable primary health care.30

Funding levels and mechanisms for GP teaching differ across the UK: in England and Wales there is no national tariff and funding has not been updated since 1995,21,22 whereas in 2019 the funding in Scotland was increased.23 The data in this study demonstrate funding for in-practice GP teaching varies significantly across UK medical schools. The average funding for in-practice GP teaching of 55.60 GBP/student/session translates to an annual sum of 20 572 GBP based on 37 weeks per year and 10 sessions per week. In contrast, the 2019 national tariff for secondary care placements in England is 33 286 GBP per year,21 and a recent costing exercise has found the actual cost of undergraduate teaching to GP practices in England to be 111 GBP per teaching session, equivalent to 40 700 GBP per year.22 A similar costing exercise in Scotland found the cost of teaching to be 85 GBP per teaching session, equivalent to 31 450 GBP per year.23 A lack of funding to support investment in practices is also concerning given the evidence that space is a barrier to hosting medical students.29,34

In 2016, the UK House of Commons Health Select Committee called for new funding arrangements that reflect the true cost of teaching undergraduates to be expedited to be in place by 2016–2017.35 Despite these recommendations, no changes have been made to date. Underfunding of undergraduate GP teaching has also been highlighted by the RCGP; the disparity of funding between primary and secondary care teaching is emphasised by the cited statistic that GPs receive around 40% less than their hospital counterparts for undergraduate teaching.36

Implications for research and practice

In summary, the authors would recommend that a minimum quantity of GP teaching is mandated across all regions of the UK, an adequate primary care tariff is agreed, and a similar survey is repeated on a 5-yearly basis in the UK and replicated internationally. The authors’ recommendations are outlined in Box 1.

Box 1.

Recommendations

| Study finding | Background | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| The amount of GP teaching in undergraduate medical curricula has not increased over the past 20 years | The Scottish Government has mandated 25% of the curriculum is delivered in the primary care setting and allocated funding in support23 | The authors recommend a similar central mandate to make more GP teaching in undergraduate curricula a reality for all UK medical schools |

| Funding for undergraduate teaching in general practice falls well below estimated costs to practices | Funding that reflects the actual cost of teaching medical students is urgently needed to maintain current teaching levels and additional funding (for example, investment in surgeries that lack space to teach) is needed to increase the quantity and quality of GP teaching | The authors recommend an adequate primary care tariff, which reflects the cost of teaching and simplifies current payment mechanisms |

| Recruitment of teaching practices is a challenge for most medical schools | Near peer teaching is recognised to be mutually beneficial for GP trainees and students alike, and recent literature provides practical suggestions to help promote these developments31–33 | The authors recommend an introduction of formal mechanisms to encourage GP teachers from underused areas such as GP trainees, early-career GPs, and locums27 |

| Less transparent and granular methods have been used historically to measure GP teaching in the UK | Few similar surveys have been undertaken internationally | The authors recommend that this survey is repeated on a 5-year basis to review progress in the UK and is replicated elsewhere to make international comparisons |

This research has shown current levels of GP teaching are static or falling. Significant variation exists across the UK in the amount of GP teaching and its support, both financial and human. Continuing underinvestment relative to the actual costs of teaching students seems to be the main factor threatening the sustainability of GP teaching and preventing its expansion. Without sufficient funding, medical schools are unlikely to influence GP recruitment issues positively or be able to promote generalism for all future doctors.

Based on these findings, and building on recent work in Scotland, a UK-wide review of general practice in medical curricula and its associated funding is urgently required to facilitate high-quality undergraduate GP teaching and promotion of the expert medical generalist role.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all members of staff at the participating medical schools who assisted in data collection of the survey.

Funding

Not applicable.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by Newcastle University Ethics Committee (Ref: 7432/2018).

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.NHS England General Practice Forward View. 2016 https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/gpfv.pdf (accessed 14 Jul 2020).

- 2.Park S, Khan NF, Hampshire M, et al. A BEME systematic review of UK undergraduate medical education in the general practice setting: BEME Guide No. 32. Med Teach. 2015;37(7):611–630. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1032918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Royal College of General Practitioners, Society for Academic Primary Care Teaching general practice Guiding principles for undergraduate general practice curricula in UK medical schools. 2018 https://sapc.ac.uk/sites/default/files/rcgp-curriculum-guidance-oct-2018.pdf (accessed 20 Jul 2020).

- 4.General Medical Council Outcomes for graduates 2018. 2018 https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/dc11326-outcomes-for-graduates-2018_pdf-75040796.pdf (accessed 14 Jul 2020).

- 5.UK Shape of Training Steering Group UK Shape of Training Steering Group report. 2017 https://www.gov.scot/publications/report-uk-shape-training-steering-group/pages/4 (accessed 14 Jul 2020).

- 6.Department of Health Delivering high quality, effective, compassionate care: developing the right people with the right skills and the right values. A mandate from the Government to Health Education England: April 2013 to March 2015 2013. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/203332/29257_2900971_Delivering_Accessible.pdf (accessed 14 Jul 2020).

- 7.Lambert T, Goldacre M. Trends in doctors’ early career choices for general practice in the UK: longitudinal questionnaire surveys. Br J Gen Pract. 2011 doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X583173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Frisch S. The primary care physician shortage. BMJ. 2013;347:f6559. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viscomi M, Larkins S, Gupta TS. Recruitment and retention of general practitioners in rural Canada and Australia: a review of the literature. Can J Rural Med. 2013;18(1):13–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Querido SJ, Vergouw D, Wigersma L, et al. Dynamics of career choice among students in undergraduate medical courses. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 33. Med Teach. 2016;38(1):18–29. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1074990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Royal College of General Practitioners, Medical Schools Council Destination GP: medical students’ experiences and perceptions of general practice. 2017 https://www.rcgp.org.uk/-/media/Files/Policy/A-Z-policy/2017/RCGP-destination-GP-nov-2017.ashx (accessed 14 Jul 2020).

- 12.Alberti H, Randles HL, Harding A, McKinley RK. Exposure of undergraduates to authentic GP teaching and subsequent entry to GP training: a quantitative study of UK medical schools. Br J Gen Pract. 2017 doi: 10.3399/bjgp17X689881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Amin M, Chande S, Park S, et al. Do primary care placements influence career choice: what is the evidence? Educ Prim Care. 2018;29(2):64–67. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2018.1427003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McManus IC. Medical school applications — a critical situation. BMJ. 2002;325(7368):786–787. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7368.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Office for Students Health education funding: medical and dental target intakes for entry in 2019–20. https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/funding-for-providers/health-education-funding/medical-and-dental-target-intakes (accessed 14 Jul 2020).

- 16.Health and Education National Strategic Exchange Review of medical and dental school intakes in England. 2012 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/213236/medical-and-dental-school-intakes.pdf (accessed 14 Jul 2020).

- 17.Department of Health Expansion of undergraduate medical education: a consultation on how to maximise the benefits from the increases in medical student numbers. 2017 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/600835/Medical_expansion_rev_A.pdf (accessed 14 Jul 2020).

- 18.Roberts N, Bolton P. Medical school places in England from September 2018. 2017 http://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7914/CBP-7914.pdf (accessed 14 Jul 2020).

- 19.Royal College of General Practitioners Scotland From the frontline: the changing landscape of Scottish general practice. 2019 http://allcatsrgrey.org.uk/wp/download/primary_care/RCGP-scotland-frontline-june-2019.pdf (accessed 14 Jul 2020).

- 20.Harding A, Rosenthal J, Al-Seaidy M, et al. Provision of medical student teaching in UK general practices: a cross-sectional questionnaire study. Br J Gen Pract. 2015 doi: 10.3399/bjgp15X685321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Department of Health and Social Care Education and training tariffs: tariff guidance and prices for the 2019–20 financial year. 2019 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/791560/education-and-training-tariffs-2019-to-2020.pdf (accessed 14 Jul 2020).

- 22.Rosenthal J, McKinley R, Smyth C, Campbell J. The real costs of teaching medical students in general practice: a cost-collection survey of teaching practices across England. Br J Gen Pract. 2019 doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X706553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Scottish Government Undergraduate medical education: recommendations Funding and infrastructure. 2019 https://www.gov.scot/publications/undergraduate-medical-education-scotland-enabling-more-general-practice-based-teaching/pages/3 (accessed 14 Jul 2020).

- 24.NHS Health Education England By choice — not by chance: supporting medical students towards future careers in general practice. 2016 https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/By%20choice%20-%20not%20by%20chance.pdf (accessed 14 Jul 2020).

- 25.Brekke M, Carelli F, Zarbailov N, et al. Undergraduate medical education in general practice/family medicine throughout Europe — a descriptive study. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(1):157. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howie JG, Hannay DR, Stevenson JS. The Mackenzie report: general practice in the medical schools of the United Kingdom — 1986. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;292(6535):1567–1571. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6535.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barber JRG, Park SE, Jensen K, et al. Facilitators and barriers to teaching undergraduate medical students in general practice. Med Educ. 2019;53(8):778–787. doi: 10.1111/medu.13882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iacobucci G. NHS chief wants big overhaul of medical training. BMJ. 2017;356:j417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonald P, Jackson B, Alberti H, Rosenthal J. How can medical schools encourage students to choose general practice as a career? Br J Gen Pract. 2016 doi: 10.3399/bjgp16X685297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.World Health Organization Declaration of Astana. 2018 https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health/declaration/gcphc-declaration.pdf (accessed 14 Jul 2020).

- 31.Harrison M, Alberti H, Thampy H. Barriers to involving GP speciality trainees in the teaching of medical students in primary care: the GP trainer perspective. Educ Prim Care. 2019;30(6):347–354. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2019.1667267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thampy H, Alberti H, Kirtchuk L, Rosenthal J. Near peer teaching in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2019 doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X700361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Alberti H, Rosenthal J, Kirtchuk L, et al. Near peer teaching in general practice: option or expectation? Educ Prim Care. 2019;30(6):342–346. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2019.1657363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harding A, McKinley R, Rosenthal J, Al-Seaidy M. Funding the teaching of medical students in general practice: a formula for the future? Educ Prim Care. 2015;26(4):215–219. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2015.11494344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.House of Commons Health Committee Primary care: fourth report of session 2015–16. 2016 https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201516/cmselect/cmhealth/408/408.pdf (accessed 14 Jul 2020).

- 36.Royal College of General Practitioners Future GPs call for fair tariffs for primary care teaching. 2019 https://www.rcgp.org.uk/about-us/news/2019/june/future-gps-call-for-fair-tariffs-for-primary-care-teaching.aspx (accessed 14 Jul 2020).