Summary

The wild boar (Sus scrofa) has a wide geographical distribution and can be an important source of Trichinella spp. infection in humans in Romania.

The objective of this study was to identify the presence of Trichinella spp. in the wild boar population in Bihor County, Romania.

Eighty four plasma and diaphragm samples, collected from wild boars, were included in this study. Artificial digestion, ELISA and Western blot were performed on these specimens. All diaphragm samples were negative for Trichinella larvae in artificial digestion, while in ELISA, 54 (64.2 %) plasma samples were positive and 6 (7.1 %) plasma samples were doubtful. Western blot was performed on 26 plasma samples from which only 6 (23.0 %) gave a positive result.

Serological evidences indicate the presence of Trichinella spp. in wild boars from western Romania. Therefore, human consumers might be at risk to ingest Trichinella larvae, even in low numbers.

Keywords: Wild boars, Romania, artificial digestion, ELISA, Western blot

Introduction

The wild boar (Sus scrofa) has one of the widest geographical distributions of all terrestrial wild mammals with increasing populations in all European countries (Massei & Genov, 2004). Moreover, they are considered to be an important source of Trichinella spp. infection in humans (Boadella et al., 2011). In Romania, trichinellosis, is considered “a never-ending story” because of the local traditions and culinary customs that favor the parasites transmission to humans. Especially the consumption of undercooked meat and meat products has led to various outbreaks over the years (Neghina, 2010).

The magnetic stirrer digestion is the gold standard method for the direct detection of Trichinella larvae in meat samples (Gamble at al., 2000). This method is mandatory for meat inspection according to EU regulation (EU 2015/1375). Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using excretory-secretory (ES) antigen is a highly sensitive test for the detection of circulating antibodies against Trichinella spp. in blood samples from pigs and wild boars (Kapel & Gamble, 2000; Kapel, 2001). On the other hand, Western blot allows the identification of Trichinella infection by highlighting bands characteristic of the genus (Cuttell et al., 2014). However, this method is time consuming and is mostly used as a confirmatory assay. Successful Trichinella spp. diagnosis and controls are important for ensuring food safety and for preventing future out-breaks (Gajadhar et al., 2009).

Trichinelloscopy and artificial digestion were previously used for the identification of Trichinella spp. in wild animals in Romania (Blaga et al., 2009a; Blaga et al., 2009b; Ciobotă et al., 2015). Therefore, the objectives of this study was to assess the presence and prevalence of Trichinella spp. in wild boars from Bihor County, Romania, by using artificial digestion and serological methods.

Materials and Methods

Study area and samples

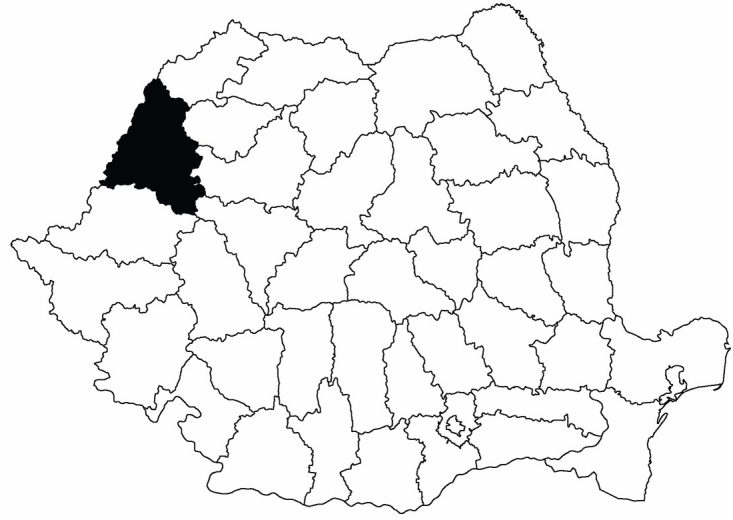

Romania is located in Eastern Europe, in the north of the Balkan Peninsula. The country has a temperate-continental climate of transitional type, with four clearly defined seasons (Trusca & Alecu, 2005). The animals originated from Bihor County (Fig. 1), a high-altitude area covered by forest. During the hunting season, in 2018, 84 plasma and diaphragm samples were collected from wild boars for research purposes. The blood samples, from each animal, were collected by jugural venipuncture into EDTA tubes. Plasma was obtained after the centrifugation of blood samples at 2500 RPM for 15 min and frozen at -15 °C until further use.

Fig. 1.

The map of Romania with counties

Artificial digestion

For artificial digestion, 5 g of diaphragm tissues were used from each animal. Four digestion pools of 100 g and one digestion pool of 20 g were made. For each pool of 100g, 2 l of heated water, 10 g of pepsin powder (1: 10,000 NF) and 16 ml of hydrochloric acid 25 % were added. The artificial digestion method was performed on all the samples according to Gamble and others (2000), in order to detect and collect the larvae for species identification.

The artificial digestion method was carried out as stated in the European community regulation EU 2015/1375.

ELISA

Eighty four samples of plasma were tested for the presence of anti-Trichinella (IgG) antibodies by an indirect ELISA commercial kit (IDEXX, Westbrook, Maine, USA). Plasma and controls were diluted to 1/20 in dilution buffer provided in the kit. Afterwards, 200 μl were transferred into the wells and incubated 30 minutes at room temperature. After 3 washes, a volume of 100 μl of diluted conjugate was introduced in each well and incubated 30 minutes at room temperature, followed by 3 repetitions of the washing step. Subsequently, 100 μl of TMB(Tetramethylbenzidine) were added and left in contact for 10 minutes at room temperature in darkness. Finally, 100 μl of stop solution were transferred into each well. The optical densities were read at 450 nm.

Samples with a cut off value (E/P- positivity index calculation formula) equal or lower than 30 % were considered negative, while values that ranged from 30 % to 40 % were doubtful. Moreover, positive samples were associated with E/P values that were equal or higher than 40 % (IDEXX ELISA technical guide, 2007).

Western blot

Twenty six plasma samples were tested with the Western blot technique. The samples were chosen randomly from the total of 84 samples previously tested in ELISA. Antigens were separated on a 10 % SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Plasma, diluted 1/100 in TBS, with an addition of 5 % milk was incubated for 1 hour at room temperature under gentle shaking. After 3 washes in TBS-tween, secondary antibodies diluted 1/15 000 in TBS, with 5 % milk were incubated in the same conditions, followed by 3 repetitions of the washing step. The obtained bands were identified by chemiluminescence with GeldocTM reader (Bio-Rad, Bulletin 6376).

Statistical analysis

The prevalence of Trichinella spp. and the associated confidence intervals at a confidence level of 95 % were established for each diagnosis tests. Furthermore, the difference in seroprevalence among females and males was analyzed by chi-squared independence test. A p value lower than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. The agreement between the results obtained in artificial digestion, ELISA and Western blot, was evaluated by Kappa statistics method (Landis, & Koch, 1977). Analyses were performed with SPSS® 20 software for Windows.

Ethical Approval and/or Informed Consent

All applicable national and institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Results and Discussion

Among the 84 animals included in the study, 45 (53.6 %) were females (38 adults, 7 juveniles) and 39 (46.4 %) were males (30 adults, 9 juveniles). All the samples were negative when artificial digestion was conducted. In ELISA 54 samples (64.2 %; 95 % CI: 53.7 – 74.2) were positive and 6 samples (7.1 %; 95 % CI: 1.4 – 12.5) were doubtful. Western blot was performed on 26 random samples, from which only 6 samples (23.0 %; 95 % CI: 5.6 – 40.3) gave a positive result. All the positive samples had three bands which were situated in the margin of 46 – 56.8.kD. Furthermore, ELISA and Western blot showed different results in the 26 samples tested. Thus, from the six samples that were positive in Western blot, only five were positive in ELISA. In addition, 11 (42.3 %; 95 % CI: 31.1 – 78.8) of the samples that were negative in Western blot, were positive in ELISA, as shown in Table 1. A Kappa value of 0.18 was found between ELISA and Western blot results, which demonstrated a slight agreement between the two methods used. Also, a Kappa value of 0.0 was observed in case of Western blot and artificial digestion, but also in case of ELISA and artificial digestion, respectively showing no inter-rated agreement between the methods chosen for diagnosis. Moreover, the seroprevalence of Trichinella spp. was statistically higher in females than males, when ELISA test was used, at a p value < 0.01.

Table 1.

The comparative results for artificial digestion, ELISA, and Western blot.

| Nr. Ctr. | Gender | Artificial digestion | ELISA (E/P) | Western blot (bands) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | N | D (34.55%) | N |

| 3 | Male | N | D (38.66%) | N |

| 4 | Male | N | P (66.42%) | N |

| 6 | Female | N | P (41.85%) | N |

| 8 | Female | N | D (32.18%) | N |

| 11 | Female | N | N (29.51%) | N |

| 15 | Male | N | P (47.33%) | N |

| 18 | Female | N | P (52.52%) | N |

| 25 | Female | N | P (40.79%) | N |

| 30 | Female | N | D (30.58%) | P (47.4; 51.8; 55.6 kD) |

| 32 | Male | N | P (157.72%) | P (46.4; 50.7; 58.5 kD) |

| 39 | Female | N | P (62.04%) | N |

| 68 | Male | N | P (53.37%) | N |

| 79 | Male | N | N (27.20%) | N |

| 81 | Male | N | N (26.78%) | N |

| 83 | Male | N | P (171.46%) | P (48.7; 52.3; 57.4 kD) |

| 92 | Female | N | P (63.20%) | P (47.4; 51.8; 55.6 kD) |

| 104 | Male | N | P (57.03%) | P (47.0; 51.8; 56.7 kD) |

| 115 | Female | N | D (39.11%) | N |

| 154 | Female | N | N (25.70%) | N |

| 156 | Male | N | P (65.00%) | N |

| 157 | Male | N | P (49.52%) | P (46.0; 50.2; 55.7 kD) |

| 158 | Female | N | P (42.48%) | N |

| 166 | Female | N | D (37.12%) | N |

| 169 | Female | N | P (56.14%) | N |

| 176 | Female | N | P (50.10%) | N |

In case of artificial digestion, the lack of other regional muscles samples that are recommended in EU regulation can be responsible for the negative results. Kapel (2001) suggested that diaphragm and tongue muscles were the predilection sites in wild boars, independent of Trichinella genotype and infection level. Blaga et al., (2009a) observed that in Romania from 1997 to 2004, the prevalence rate of Trichinella spp. infection in wild boars tested by trichinelloscopy was 8.6 %. Another study conducted from 2010 to 2014 in Hunedoara county, Romania, indicated a prevalence rate of 0.82 % for Trichinella spp. infection in wild boars after the examination of intercostal muscle samples by trichinelloscopy and artificial digestion (Ciobotă et al., 2015). Moreover, another study in which the preferential muscles samples were tested with trichinoscopy and artificial digestion, found the presence of Trichinella larvae in five wild boars. In three of the animals, T. britovi was identified, while the remaining two animals were diagnosed with T. spiralis infection (Blaga et al., 2009b). Some recently collected larvae in Romania, during the artificial digestion of diaphragm samples from pigs and wild boars evidenced the circulation of T. spiralis and T. britovi in these animal species (personal communication, unpublished data).

Although artificial digestion was negative, ELISA and Western blot showed high rates of positivity. Indirect ELISA is commonly used for the surveillance of Trichinella spp. infection (Elbers et al., 2000; Gamble et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2015) and it can detect infection levels as low as 1 larvae/ 100g of tissue (Gamble et al., 1983). Møller et al. (2005), by using indirect ELISA, detected Trichinella specific antibodies in sera and muscle fluid samples from wild boars. Moreover, ELISA based on carbohydrate tyvelose or excretory/secretory antigens, have been considered the most suitable antigens available (Forbes et al., 2004). However, the assay yields false positive results due to cross-reactivity of the secondary antibodies (Nöckler et al., 2004; Davidson et al., 2009; Széll et al., 2012). Therefore, ELISA positive results are recommended to be confirmed by Western blot due to its specificity of 100 % and the capacity to eliminate ELISA false-positive sera results (Gómez-Morales et al., 2012; Cuttell et al., 2014).

Taken together, these results indicate the circulation of Trichinella larvae at a low level in wild boar population of Bihor County. The larvae burden might be too low to be detected by direct artificial digestion whereas serological approaches allow to detect circulating antibodies or the presence of Trichinella spp. specific antigens. However, other studies observed a higher seroprevalence percentages, than the positivity rates observed in Western Blot or muscle digestion (Davidson et al., 2009).

In Romania, the human population can acquire trichinellosis mainly by consuming raw pork and wild boar meat. The meat from these animals are usually prepared accordingly to local habits and traditions. Commonly, the wild boar meat products (dried raw salami, raw dried sausage, smoked pastrami e.g.) are not subjected to thermal processing, exposing the population to parasitic infestations. In 1993, controlled pig meat was mixed with infested wild boar meat, causing an extensive outbreak in Romania (Cironeanu & Ispas, 2002). Moreover, in January 2007, in the city of Timisoara, 5 humans acquired trichinellosis after consuming sausages with infected wild boar meat mixed with pork (Neghina, unpublished data).

Epidemiological actions that limit the spread of the infestation to humans and animals should be widely available and correctly applied by pig breeders, hunters, and consumers to prevent future outbreaks. These measures should include hygiene conditions in backyard pig breeding and raising, testing of wild boar meat from hunters and the consumption of only controlled wild boar meat by the local population (Neghina, 2010). However, in countries with high percentages of Trichinella spp. infection, in both animals and humans, an effective diagnosis method is essential for providing food safety and preventing the onset of human outbreaks. Even if trichinelloscopy is a widely used method for Trichinella spp. detection, its sensitivity is lower than that of artificial digestion (Li et al., 2010). The digestion assay is considered to be the most reliable procedure and it can be widely applied in practice (Gamble et al., 2000).

The EU Regulation 2015/1375 highlights the importance, in case of wild boar meat, of using a sufficient amount of samples from the predilection sites, meaning foreleg, tongue or diaphragm muscles. In this regard and giving the recommendation of using at least 10 g of muscle tissue from each animal, is essential to ensure a correct training for the personnel that is responsible for the sample collection and inspection.

Conclusions

Serological evidences confirmed the exposure of wild boars from Bihor County, to Trichinella spp. Therefore, the consumers might be at risk to ingest low larvae burden as animals are misdiagnosed after the parasitological diagnosis by artificial digestion. To prevent future misdiagnosis by using artificial digestion, only trained personal should perform the sampling and the digestion assay protocol. Human trichinellosis is continuously reported in Romania, consequently, risk factor assessment and surveillance should be improved in wild boars and other wild species to monitor the parasite presence and prevalence.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank to, Sivia Diana Borșan, Maria Emilia Nedișan, Cristian Magdaș, and Andra Toma Naic, for their help in sample collection.

This research was supported by COST FA 1408 action, French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety (ANSES) and the University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine of Cluj-Napoca (USAMV Cluj-Napoca).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Authors have no potential conflict of interest pertaining to this submission to Helminthologia.

References

- Bio-Rad, Bulletin 6376, General Protocol for Western Blotting. Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc, 1-2. Retrieved January. 2016;10:2019. bio-rad.com https://www.bio-rad.com/web-root/web/pdf/lsr/literature/Bulletin_6376.pdf from. database. [Google Scholar]

- Blaga R., Durand B., Stoichici A., Gherman C., Stefan N., Cozma V., Boireau P.. Animal Trichinella infection in Romania: Geographical heterogeneity for the last 8 years. Vet. Parasitol. 2009a;159(3–4):290–294. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaga R., Gherman C., Cozma V., Zocevic A., Pozio E., Boireau P.. Trichinella species circulating among wild and domestic animals in Romania. Vet. Parasitol. 2009b;159(3–4):218–221. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boadella M., Gortazar C., Acevedo P., Carta T., Martin-Hernando M.P., de la Fuente J.. Six recommendations for improving monitoring of diseases shared with wildlife: examples regarding mycobacterial infections in Spain. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2011;57:697–706. doi: 10.1007/s10344-011-0550-x. Vicente. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Commission implementing regulation (EU) 2015/1375 of 10 August. laying down specific rules on official controls for Trichinella in meat, Official Journal of the European Union EN. 2015. [DOI]

- Ciobotă F. O., Cristea G., Ioniță M., Mitrea I. L.. Epidemiological study on Trichinella infection in pigs and wild boars in hunedoara county (romania), during of 2010–2014 period. Proc. Rom. Acad., Series B, Supplement 1, 45–47. Supplement 1/2015, 4th ISAA. Retrieved January. 2015;9:2020. academiaromana.rodatabasesectii2002/proceedingsChemistry/doc2015-3s/art11_45.pdf from. [Google Scholar]

- Cironeanu I., Ispas A. T. Totul despre trichineloza. [All about trichinellosis] Bucharest: MAST Publishing House, Bucharest, Romania; 2002. pp. 9–64. In Romanian. [Google Scholar]

- Cuttell L., Gómez-Morales M. A., Cookson B., Adams P. J., Reid S. A., Vanderlinde P. B., Jackson A.L., Gray C., Traub R. J.. Evaluation of ELISA coupled with western blot as a surveillance tool for Trichinella infection in wild boar Sus scrofa. Vet. Parasitol. 2014;199(3–4):179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson R. K., Ørpetveit I., Møller L., Kapel C. M.. Serological detection of anti-Trichinella antibodies in wild foxes and experimentally infected farmed foxes in Norway. Vet. Parasitol. 2009;163(1–2):93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbers A.R.W., Dekkers L.J.M., van der Giesen J.W.B.. Sero-surveillance of wild boar in the Netherlands, 1996–1999. Rev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz. 2000;19(3):848–854. doi: 10.20506/rst.19.3.1254. http://agris.fao.org/agrissearch/search.do?recordID=FR2000004841 Retrieved January 10, 2020 from Agris database. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes L. B., Appleyard G. D., Gajadhar A. A.. Comparison of synthetic tyvelose antigen with excretory–secretory antigen for the detection of trichinellosis in swine using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J. Parasitol. 2004;90(4):835–840. doi: 10.1645/GE-187R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble H. R., Anderson W. R., Graham C. E., Murell K. D.. Diagnosis of swine trichinosis by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using an excretory-secretory antigen. Vet. Parasitol. 1983;13(4):349–361. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(83)90051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble H. R., Bessonov A.S., Cuperlovic K., Gajadhar A.A., van Knapen F., Noeckler K., Schenone H., Zhu X.. International commission on trichinellosis: recommendations on methods for the control of Trichinella in domestic and wild animals intended for human consumption. Vet. Parasitol. 2000;93:393–408. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(00)00354-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble H. R., Pozio E., Bruschi F., Nöckler K., Kapel C. M. O., Gajadhar A. A.. International Commission on Trichinellosis: recommendations on the use of serological tests for the detection of Trichinella infection in animals and man. Parasite. 2004;11(1):3–13. doi: 10.1051/parasite/20041113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajadhar A. A., Pozio E., Gamble H. R., Nöckler K., Maddox-Hyttel C., Forbes L. B., Vallee I., Rossi P., Marinculic A., Boireau P.. Trichinella diagnostics and control: mandatory and best practices for ensuring food safety. Vet. Parasitol. 2009;159(3–4):197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IDEXX ELISA technical guide. IDEXX Laboratories Inc, 10-18. Retrieved February. 2007;10:2019. idexx.com https://www.idexx.com/files/elisa-technical-guide.pdf from. database. [Google Scholar]

- Kapel C.M.O., Gamble H.R.. Infectivity, persistence, and antibody response to domestic and sylvatic Trichinella spp. in experimentally infected pigs. Int. J. Parasitol. 2000;30:215–221. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(99)00202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapel C.M.O.. Sylvatic and domestic Trichinella spp. in wild boars; infectivity, muscle larvae, distribution, and antibody response. J. Parasitol. 2001;87:309–314. doi: 10.2307/3285046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. J., Jeong W. S., Kim E. M., Yeo S. G., An D. J., Yoon H., Kim E.L., Park C. K.. Prevalence of Trichinella spp. anti-bodies in wild boars Sus scrofa and domestic pigs in Korea. Vet. Med. 2015;60(4):181–185. doi: 10.17221/8105-VETMED. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landis J.R., Koch G.G.. An application of hierarchical kappa-type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics. 1977;33(2):363–374. doi: 10.2307/2529786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Cui J., Wang Z.Q., Jiang P.. Factors affecting the sensitivity of artificial digestion and its optimization for inspection of Trichinella spiralis in meat. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2010;7(8):879–885. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2009.0445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Morales M. A., Ludovisi A., Amati M., Blaga R., Zivojinovic M., Ribicich M., Pozio E.. A distinctive Western blot pattern to recognize Trichinella infections in humans and pigs. Int. J. Parasitol. 2012;42(11):1017–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massei G., Genov P. V.. The environmental impact of wild boar. Galemys. 2004;16(1):135–145. semanticscholar.org pdfs.semantic-scholar.org/1717/da1dd916df958802589654700bf80045029c.pdf ISSN: 1137-8700. Retrieved July 20, 2019 from . database. [Google Scholar]

- Møller L. N., Petersen E., Gamble H. R., Kapel C. M.. Comparison of two antigens for demonstration of Trichinella spp. antibodies in blood and muscle fluid of foxes, pigs and wild boars. Vet. Parasitol. 2005;132(1–2):81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neghina R.. Trichinellosis, a Romanian never-ending story. An overview of traditions, culinary customs, and public health conditions. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2010;7(9):999–1003. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2010.0546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nöckler K., Hamidi A., Fries R., Heidrich J., Beck R., Marinculic A.. Influence of Methods for Trichinella Detection in Pigs from Endemic and Non-endemic European Region. J. Vet. Med. 2004;51(6):297–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.2004.00770.x. Series B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Széll Z., Marucci G., Ludovisi A., Gómez-Morales M. A., Sréter T., Pozio E.. Spatial distribution of Trichinella britovi, T. spiralis and T. pseudospiralis of domestic pigs and wild boars Sus scrofa in Hungary. Vet. Parasitol. 2012;183(3–4):393–396. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trusca V., Alecu M.. Romania’s Third National Communication on Climate Change under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Grue and Hornstrup, Holstebro. 2005;28 https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/natc/romnc3.pdf Retrieved January 5, 2020 from unfccc.int database. [Google Scholar]