Abstract

Background

Crisis Standards of Care (CSC) provide a framework for the fair allocation of scarce resources during emergencies. The novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has disproportionately affected Black and Latinx populations in the USA. No literature exists comparing state-level CSC. It is unknown how equitably CSC would allocate resources.

Methods

The authors identified all publicly available state-level CSC through online searches and communication with state governments. Publicly available CSC were systematically reviewed for content including ethical framework and prioritization strategy.

Results

CSC were identified for 29 states. Ethical principles were explicitly stated in 23 (79.3%). Equity was listed as a guiding ethical principle in 15 (51.7%); 19 (65.5%) said decisions should not factor in race, ethnicity, disability, and other identity-based factors. Ten states (34.4%) allowed for consideration of societal value, which could lead to prioritization of health care workers and other essential personnel. Twenty-one (72.4%) CSC provided a specific strategy for prioritizing patients for critical care resources, e.g., ventilators. All incorporated Sequential Organ Failure Assessment scores; 15 (71.4%) of these specific CSC considered comorbid conditions (e.g., cardiac disease, renal failure, malignancy) in resource allocation decisions.

Conclusion

There is wide variability in the existence and specificity of CSC across the USA. CSC may disproportionately impact disadvantaged populations due to inequities in comorbid condition prevalence, expected lifespan, and other effects of systemic racism.

Keywords: Crisis Standards of Care, COVID-19, Infectious disease, Pandemic, Equity

Introduction

As the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) spreads across the USA, many communities are facing the threat of shortages and limitations on healthcare resources, including hospital beds, staff, and critical equipment such as ventilators, hemodialysis machines, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) machines. In times of crisis such as the current national state of emergency [1, 2], individual states may choose to implement uniform criteria to guide the allocation of scarce resources. These so-called Crisis Standards of Care (CSC) provide a framework for determining who is prioritized to receive scarce resources. At present, the existence of state-level CSC has not been described in the literature, nor have such guidelines been compared at a regional or national level to identify trends or discrepancies that may prove important in the overall health of the nation and that of more vulnerable segments of the population. This study sought to identify and review all publicly available state-level CSC in the USA. Secondarily, we sought to compare the ways in which CSC prioritize patients for the allocation of scarce resources such as ventilators, and to consider the ethical and equity implications of these decisions.

Background

As the H1N1 virus spread in 2009, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) asked that the Institute of Medicine develop guidelines for resource allocation in times of scarcity. The resulting report [3] led to recommendations and regional workshops [4–6] for developing CSC. Key principles on which this framework suggests developing CSC include fairness, duty to care, duty to steward resources, transparency, consistency, proportionality, and accountability [7].

In 2014, the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) published consensus recommendations for triage [8] and surge capacity logistics [9] during pandemics and other disasters. Key recommendations include the need for preparation with local and regional stockpiles as well as surge plans across all departments within a health system. With regard to triage [8], CHEST recommends enacting a unified process across an affected geographic area (e.g., state), with appropriate oversight to ensure adherence to the same standards despite potential local differences. They also note that triage processes should rely on protocols, rather than clinical judgment, and that such protocols should be developed in advance of emergencies. Further, they recommend use of an appropriately accurate physiologic scoring system, and reevaluation over time.

As COVID-19 has spread around the world and resources in parts of even the wealthiest nations have become limited, many have again called for explicit planning for the allocation of scarce resources [7, 10, 11]. Within the USA, early data has raised concerns about stark disparities in incidence and case fatality rates among communities of color [12–16]. This has called attention to the ways in which systemic racism may be shaping the pandemic, and has subsequently brought increased scrutiny of existing CSC in states such as Massachusetts [17], where clinicians [18–21] and politicians [22, 23] alike raised concern about the racial, ethnic, and disability-related inequities that may emerge if and when existing CSC are implemented. Massachusetts’ CSC have since been updated [24] in response to this advocacy, incorporating more specific language around health equity but retaining the same decision-making structure.

This review was undertaken in an effort to better understand the current status of CSC around the country, including the ways in which existing guidelines instruct physicians and healthcare systems to allocate specific resources such as ventilators, which may become scarce during a widespread respiratory illness such as the present COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

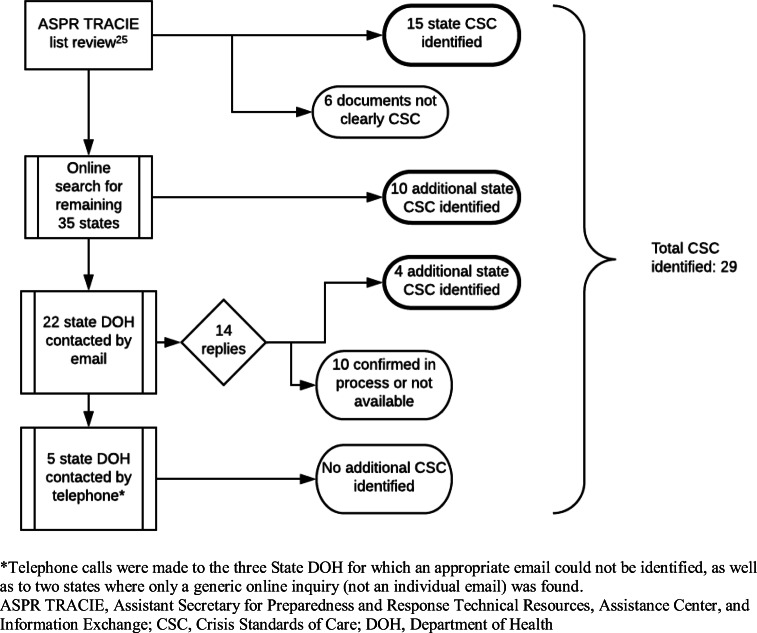

Two authors (ECM and CS) attempted to identify CSC for each state between April 13 and April 17, 2020. Identification of state-level CSC was first attempted using a list available on the ASPR Technical Resources, Assistance Center, and Information Exchange (TRACIE) website [25]. If no document or only a nonspecific CSC was found, Google was used to search using the terms “state name” and “crisis standards of care.” If the first ten search results failed to yield a specific CSC, the state’s department of health (DOH) website was searched, with particular attention to Preparedness, Emergency Response, and COVID-19 pages. If this, too, failed to identify a guideline, the DOH was contacted via the website’s information request form, and/or via a personalized email from ECM or CS to an individual from the DOH’s Preparedness (or equivalent) team. If an email address for a relevant DOH employee was not easily identified but a telephone number was listed, the DOH was called to request information about CSC for the state.

Available CSC were read by the first two authors and categorized as “specific” if they include explicit decision-making criteria for allocation of resources including ventilators, or “nonspecific” if they lacked clear decision-making criteria. Reviewer agreement on this distinction was 100%. CSC were systematically examined for the following content: explicit ethical principles around which guidelines were created; whether equity was explicitly listed as a guiding principle (e.g., explicit discussion of equity between individuals of different identities, marginalized groups, or discussion of population-level disparities); whether CSC explicitly state that resources should be allocated in an identity-blind manner (i.e., without regard to race, ethnicity, gender); specific guidance for allocation of critical care resources, including ventilators; exclusion criteria for access to critical care; criteria used for prioritization of patients for critical care resources, i.e., use of SOFA [26] or Modified SOFA (MSOFA) [27, 28] scores; and consideration of long-term comorbidities in the prioritization framework. Reviewer agreement on each of these factors was greater than 90%; discrepancies were adjudicated by discussion. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize characteristics of identified CSC.

Results

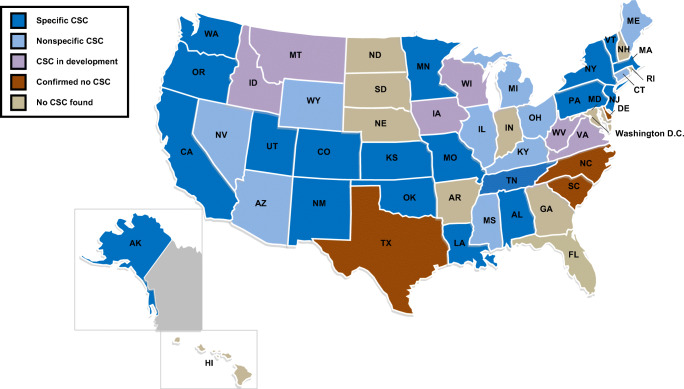

A state-level CSC document was identified for 29 states (see Fig. 1 and Table 1). Fifteen were identified from the ASPR TRACIE website [25]. Six of the 28 state-level resources listed at that site (CA, FL, MD, MT, OH, TN) were either not available via the provided links, or were deemed to not be CSC as they did not include guidance for triage and/or resource allocation. Updated versions of several other CSC documents in that list were identified by the authors (e.g., MA and PA). An additional ten CSC were found through electronic searches either using the search terms noted above or on the state DOH website. A total of 22 state DOH were contacted by email, 14 of whom replied on or before May 3, 2020. Four additional CSC were identified after email correspondence with state DOH personnel, and six states confirmed that CSC were in development. For the three states without an identified email address, as well as two for which only a generic inquiry email address was available, state DOH were contacted by telephone; these calls did not yield any additional CSC documents (Fig. 2). Appendix 1 contains links to each of the reviewed CSC documents.

Fig. 1.

Crisis Standards of Care guideline identification process

Table 1.

Comparison of available state-level Crisis Standards of Care (CSC)

| State | Existence of CSC* | Date of identified document** | Explicit ethical framework | Health equity as a guiding principle | Explicitly identity-blind allocation of resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Yes | 4/2010; 2/2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Alaska | Yes | 3/2020 | No | No | No |

| Arizona | Yes | 2020 | Yes | No | Yes |

| Arkansas | None identified | ||||

| California | Yes | 4/2020++ | Yes | No | Yes |

| Colorado | Yes | 4/2020++ | No | No | No |

| Connecticut | Yes | 10/2010 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Delaware | None identified | ||||

| Florida | None identified | ||||

| Georgia | None identified | ||||

| Hawaii | None identified | ||||

| Idaho | No–in development | ||||

| Illinois | Yes | 3/2018; 3/2020++ | Yes | No | Yes |

| Indiana | None identified | ||||

| Iowa | No–in development | ||||

| Kansas | Yes | 9/2013 | No | No | No |

| Kentucky | Yes | 3/2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Louisiana | Yes | 9/2011 | Yes | Yes | No |

| Maine | Yes | 6/2015 | No | No | No |

| Maryland | None identified | ||||

| Massachusetts | Yes | 4/2020++ | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Michigan | Yes | 11/2012 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Minnesota | Yes | 12/2013; 1/2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mississippi | Yes | 2/2017 | Yes | No | No |

| Missouri | Yes | 4/2020++ | Yes | No | No |

| Montana | No–in development | ||||

| Nebraska | None identified | ||||

| Nevada | Yes | 4/2020++ | Yes | Yes | No |

| New Hampshire | None identified | ||||

| New Jersey | Yes | 4/2020++ | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| New Mexico | Yes | 6/2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| New York | Yes | 11/2015 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| North Carolina | No | ||||

| North Dakota | None identified | ||||

| Ohio | Yes+++ | 4/2020 | Yes | No | No |

| Oklahoma | Yes | 4/2020 | Yes | No | Yes |

| Oregon | Yes | 6/2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pennsylvania | Yes | 4/20202 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Rhode Island | No | ||||

| South Carolina | No | ||||

| South Dakota | No | ||||

| Tennessee | Yes | 7/2016 | Yes | No | Yes |

| Texas | No | ||||

| Utah | Yes | 6/2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Vermont | Yes | 5/2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Virginia | No–in development | ||||

| Washington | Yes | 3/2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| West Virginia | No–in development | ||||

| Wisconsin | No–in development | ||||

| Wyoming | Yes | 6/2019 | No | No | No |

CSC Crisis Standards of Care

*As of May 3, 2020

**Where more than one document was identified, both were reviewed. Details presented here reflect a combination of available information from these guidelines

+Specific guidance for critical care and ventilator allocation in 2010; 2/2020 document provides broader guidance

++Specific guidance related to the COVID-19 pandemic

+++Guidelines obtained from the Ohio Hospital Association through correspondence with the Ohio Department of Health’s Chief of the Bureau of Health Preparedness

Fig. 2.

Crisis Standards of Care across the USA, by status of development as of May 3, 2020

Wide variation was noted in the degree of detail provided in CSC regarding the process of their development and the principles on which they were created (Table 1). Fifteen CSC (51.7%) were created or updated this year; eight (27.5%) specifically addressed the COVID-19 pandemic. Twenty-four (85.7%) explicitly stated the ethical principles on which resource allocation decisions should be made. Nineteen (65.5%) explicitly articulated that resource allocation decisions should be made without regard to race, ethnicity, disability, and other identity-based factors. Health equity with respect to these identities, not including equity among hospitals, was identified as an ethical consideration in 16 of the available CSC (55.2%).

The means by which scarce resources should be allocated under each of the 29 identified CSC varied widely (Table 2). Three states (KY, MI, WY) explicitly left all triage and decision-making to local institutions. Ten CSC (34.5%) incorporated exclusion criteria which would preclude patients from access to critical care when CSC are enacted (see Tables 2 and 3). The most common exclusion criteria (Table 3) included low likelihood of immediate survival, e.g., ongoing cardiac arrest (80% of states with exclusion criteria), neurologic conditions including “severe dementia,” or “advanced” and/or “irreversible” neurologic events (70% of states with exclusion criteria), and “severe” or “overwhelming” trauma or burns with very poor (e.g., < 10%) predicted survival (80% of CSC with exclusion criteria). The degree of specificity provided within each category varied widely, e.g., “CHF (NYHA Class III or IV), left ventricular dysfunction, hypotension, new ischemia; known congestive heart failure with ejection fraction less than 25% or persistent ischemia/pulmonary edema unresponsive to therapy,” in one CSC (AL), compared with “severe congestive heart failure” as a criterion for transfer to palliative care rather than ICU admission during periods of resource limitation (WA).

Table 2.

Comparison of available state-level Crisis Standards of Care guidance for the allocation of critical care resources

| State | Date of identified document+ | Specific guidance for allocation of critical care resources, including ventilators | Factors included in specific guidance for ventilator allocation, if any | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusion criteria for access to critical care | Use of SOFA or MSOFA for determining priority | Consideration of long-term comorbidities | Consideration of pregnancy++ | Consideration of essential worker status | |||

| Alabama | 4/2010 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Alaska | 3/2020 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Arizona | 2020 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes* |

| California | 4/2020 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Colorado | 4/2020 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes** |

| Connecticut* | 10/2010 | No | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | Yes* |

| Illinois* | 3/2018; 3/2020 | No | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | Yes* |

| Kansas | 9/2013 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Kentucky | 3/2020 | No | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Louisiana | 9/2011 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Maine | 6/2015 | No | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Massachusetts | 4/2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes** |

| Michigan | 11/2012 | No | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Minnesota | 12/2013 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Mississippi | 2/2017 | No | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Missouri | 4/2020 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes* |

| Nevada | 4/2020 | No | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| New Jersey | 4/2020 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes** |

| New Mexico | 6/2018 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes* |

| New York | 11/2015 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Ohio | 4/2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Oklahoma | 4/2020 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes** |

| Oregon | 6/2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes* |

| Pennsylvania | 4/2020 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Tennessee | 7/2016 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Utah | 6/2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Vermont | 5/2019 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Washington | 3/2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Wyoming | 6/2019 | No | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

SOFA Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, MSOFA Modified Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

+Where more than one document was identified, both were reviewed. Details presented here reflect a combination of available information from these guidelines

++Variable consideration; some CSC (MA, PA, UT) increased priority based on gestational age and fetal viability; CO incorporated pregnancy as a third-tier tie-breaker; OR stated it can be considered, although no specific guidance is given as to how

*CSC included language noting that essential workers, including healthcare personnel, could or should receive priority for scarce resources, although exactly how this should be factored into specific resource allocation frameworks was not discussed

**Essential worker status was used as a tie-breaker, if needed, after consideration of exclusion criteria, acuity of illness (SOFA/MSOFA), and/or comorbidities

Table 3.

Comparison of exclusion criteria for access to critical care from available state-level Crisis Standards of Care

| State | Poor short-term survival1 | Commonly cited specific examples of exclusion criteria related to end-organ failure | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac2 | Pulmonary3 | Renal4 | Hepatic5 | Neurologic6 | Oncologic7 | Trauma & burns8 | ||

| Alabama | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Kansas | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Louisiana | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Massachusetts | X | X | X | X | ||||

| New York | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Ohio | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Oregon | X | |||||||

| Tennessee | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Utah | X | |||||||

| Washington* | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

NYHA New York Heart Association, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in the first second of expiration, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, MELD model for endstate liver disease

1Variable, e.g., “severe advanced chronic disease with short life expectancy, < 6 months” (AL) or “immediate or near-immediate death despite aggressive therapy” (MA, NY)

2Cardiac arrest (all), heart failure classified as “severe” (WA), NYHA Class III or IV (AL, KS, OH, TN) or Class IV (LA)

3Wide variation in specificity, from FEV1 < 25% (KS, TN) to “end-stage COPD” (OH) or “severe chronic lung disease” (WA)

4Variable, including “anyone on or requiring dialysis” (AL), or “dialysis dependent” (KS, TN)

5Severe cirrhosis (AL, WA); MELD score > 20 (AL, KS); Pugh score > 7 (OH, TN) or > 9 (LA)

6Severe dementia (AL, LA, TN); “severe,” “advanced,” and/or “irreversible” neurologic event or functional impairment (AL, KS, LA, MA, TN); “traumatic brain injury with no motor response to painful stimulus” (NY)

7“Incurable” or “metastatic” malignancy with “poor prognosis” (all)

8Severe burns (e.g., “> 60% body surface area” (AL), “body surface > 40%” (TN), or “where predicted survival ≤ 10%” (NY, OH)); “severe” or “overwhelming” trauma (AL, LA, MA, OH, WA)

*Washington’s CSC listed conditions that should be considered as criteria for transfer to outpatient or palliative care during times of resource limitation; although not explicitly called “exclusion criteria,” these were incorporated into the screening process to determine eligibility for ICU care, and were thus included here

Of the 29 identified CSC, ten (34.5%) allowed for the consideration of societal value in prioritizing health care workers; four used essential worker status as a tie-breaker for otherwise equally prioritized patients, while the remaining six did not specify exactly how essential workers might be given priority (Table 2). Five (17.9%) CSC factored pregnancy into decision making, either as a general consideration (OR), explicitly in algorithms by increasing priority for pregnant patients, particularly if at a gestational age compatible with fetal viability (MA, PA, UT), or as a tie-breaker if other factors are equal (CO) (Table 2). Specific processes for ventilator allocation were discussed in 21 CSC (72.4%). All 21 states with specific frameworks for allocation of critical care resources recommended SOFA [26] or MSOFA [27, 29] scores as a component of prioritizing patients for allocation of resources. Among the 21 specific CSC frameworks, 15 (71.4%) incorporated consideration of pre-existing chronic health conditions/comorbidities which affect long-term survival (Tables 2 and 4). Within the 15 CSC that recommended consideration of comorbid conditions in prioritizing patients for resource allocation, the most frequently cited comorbidities included heart failure or severe coronary artery disease (53.3%), chronic lung disease (60%), end-stage renal disease (46.7%), cirrhosis or other end-stage liver disease (53.3%), neurologic disorders (e.g., Alzheimer’s dementia) (33.3%), and active malignancy with poor prognosis (46.7%). The specificity with which each of these comorbid conditions was described varied between states. For example, Utah listed “end-stage COPD” while other states included “home oxygen dependent” (AK, MN, VT) as descriptors of the degree of chronic lung disease that should be factored into prioritization considerations. The Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index [30–32] was used by Colorado as a means for accounting for comorbidities in prioritization of resource allocation.

Table 4.

Comparison of long-term comorbidities included in prioritization framework from available state-level Crisis Standards of Care

| State | Comorbidities affecting longer-term survival1 | Commonly cited comorbid conditions noted for consideration | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac2 | Pulmonary3 | Renal4 | Hepatic5 | Neurologic6 | Oncologic7 | ||

| Alaska | X | X | X | ||||

| California | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Colorado | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Massachusetts | X | ||||||

| Minnesota | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Missouri | X | ||||||

| New Jersey | X | ||||||

| Ohio | X | ||||||

| Oklahoma | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Oregon | X | ||||||

| Pennsylvania | X | ||||||

| Tennessee | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Utah | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Vermont | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Washington | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

1Most commonly a two-tiered consideration of comorbidities predicting likely death within 1 year or within 5 years (MA, MO, NJ, PA) or identification of “severe underlying disease with poor long-term prognosis and/or ongoing resource demand,” or “severe underlying disease with poor short-term (< 1 year) prognosis” (AK, MN, TN, VT). Some states considered only near-term mortality, e.g., within 6–12 months (OR). CO used the Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index Score. Others were less specific, e.g., “life-limiting illnesses” (UT), or “severe medical comorbidities and advanced chronic conditions that limit near-term duration of benefit and survival” (CA)

2Congestive heart failure, specified as NYHA Class III or IV (CA), and NYHA Class IV with frailty (WA), with ejection fraction < 25% (TN, VT), “end-stage” or “severe” (UT, WA); severe multi-vessel CAD (CA, OK)

3Chronic lung disease, characterized as “home oxygen dependent” (AK, MN, TN, VT); “moderate” (CA) or “severe” (CA, WA); “severe with frailty” (OK); or “end-stage COPD” (UT)

4Renal disease, characterized as “dialysis dependent” (AK, MN, TN, VT); “end-stage” (CA); or “end-stage renal disease and age 75 or older” (OK)

5Variably characterized liver disease, including “cirrhosis with a history of decompensation” (CA), MELD score ≥ 20 and ineligible for transplant (OK); “terminal” (UT); or “severe cirrhotic liver disease with multi-organ dysfunction” (WA)

6Wide variability, including “moderate” (CA) or “severe Alzheimer’s disease or related dementia” (CA, OK); “dementia or hemiplegia” (CO); and “baseline functional status (...physical ability, cognition)” (WA)

7Malignancy, with “< 10-year expected survival” (CA); metastatic disease (CO); “terminal” (UT); or “with poor prognosis for recovery” (MN, TN, VT, WA)

NYHA New York Heart Association, CAD coronary artery disease, CHF congestive heart failure, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in the first second of expiration, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, MELD model for endstate liver disease

Discussion

The allocation of scarce healthcare resources during times of crisis is fraught with ethical challenges. Development of CSC has the potential to mitigate both individual and societal moral injury by establishing a clear framework for decision-making and prioritization. This is of particularly urgent concern due not only to the rapid progression of the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA and impending resource shortages, but also due to increasingly widespread concerns about racial inequities that are emerging from states and communities that are tracking demographic data for patients with COVID-19 [12–16]. This review endeavors to identify and compare all publicly available, state-level CSC as SARS-CoV-2 continues to spread throughout the USA.

The development of CSC was identified as a priority by the federal government, which has provided strategic guidance for how to do so [3–6, 11]. Although some have suggested that as many as 36 states have developed CSC [33], we identified only 29 states with publicly available CSC as of May 3, 2020. The degree of specificity and detail in available CSC is extremely varied, ranging from broad ethical guidance to shape the development of local- or hospital-level policy, to explicit criteria and algorithms for determining the allocation of ventilators and other specific resources. The general structure of these algorithms includes consideration of the following: (1) exclusion criteria, usually based on a low likelihood of survival despite maximal resource allocation; (2) a calculation of an objective score to reflect the severity of present illness and thus prioritization category; and (3) repeated evaluation over time to determine ongoing priority status. In some cases, additional consideration is made for factors that may predict individual or societal benefit. Most algorithms explicitly state that the physician responsible for direct patient care should not be the same individual making decisions regarding allocation of scarce resources to that patient. It is essential that the equity implications of CSC content at each level—exclusion criteria, use of SOFA/MSOFA as a marker of acute illness severity, and the consideration of comorbid conditions and other individual factors such as social worth—be critically examined before CSC are implemented. Similarly, the process by which CSC are developed must include diverse perspectives to ensure resulting documents are not inadvertently discriminatory.

Crisis Standards of Care: Content

Exclusion criteria are intended to avoid allocating scarce resources to patients who are unlikely to survive regardless of the care provided; however, when CSC include broad, nonspecific exclusion criteria, their application may introduce significant bias or variability at either the clinician or institutional levels. For example, the Kansas CSC [34] had broad exclusion criteria including renal failure requiring hemodialysis, and metastatic malignancy with poor prognosis. In contrast, New York’s CSC for ventilator allocation [35] explicitly did not exclude patients based on the need for dialysis or the presence of metastatic malignancy, a decision which their guidelines report was made due to wide variations in prognosis, life expectancy, and quality of life among individuals in these groups. If exclusion criteria for accessing critical care are used, it may be that very specific guidance are more useful than broad recommendations for excluding those with “poor prognosis,” as interpretation at the facility or individual level may lead to inequitable exclusion of some individuals.

All 21 CSC that specifically discussed critical care and ventilator allocation relied on the SOFA/MSOFA score as an objective means of evaluating the severity of illness at the time of triage although SOFA scores were developed for use in the study of populations, and are thus not accurate for predicting individual-level mortality [36]. Some studies have raised concerns with the validity of these scoring systems as a triage tool, given that more than half of patients with the highest category of SOFA or MSOFA scores (> 11) ultimately survived [27]. Nevertheless, most CSC used SOFA scores to categorize patients into one of four priority levels. Most CSC explicitly counsel against the comparison of two individuals within the same category based on a slightly differences in the exact SOFA score, although some suggest using the numeric score as a tie-breaker. Further research is needed to better understand the ways in which this could disproportionately affect different communities.

A great deal of variation emerged when comparing the extent to which CSC incorporated consideration of factors beyond the severity of acute illness requiring ICU care. Of the 29 available specific CSC, 19 (5.5%) explicitly stated that triage decisions should be made in an identity-blind manner (i.e., without consideration of race or ethnicity). Eleven of these CSC, however, are among the 15 states (see Tables 2 and 4) that considered comorbid conditions in resource allocation decisions. The consideration of life-limiting comorbidities in allocation of resources during times of crisis may contribute to maximizing the number of lives, and/or the number of life-years saved. However, given the well-described and profoundly unequal distribution of illness between racial and ethnic groups in the US [37–41], the consideration of comorbid conditions such as hypertension [42], diabetes [43, 44],, and chronic kidney disease [45], is likely to function as a proxy for allocation of resources by race and ethnicity. Similarly, individuals with disabilities have a greater incidence of comorbid health conditions [46], and have more limited life expectancies [47] than able-bodied individuals. Consideration of long-term prognosis in allocation decisions may prove problematic, as CSC from Pennsylvania acknowledge: “Based on consultation with experts… we have intentionally not included a list of example conditions associated with life expectancy <1 year and <5 years… [to avoid decisions] being applied as blanket judgments, rather than in the context of individualized assessments by clinicians, based on the best available objective medical evidence.” [48]

Given the significant disparities in incidence, morbidity, and mortality from COVID-19 that have emerged among minority populations [12–16], the consideration of identity-based characteristics and their proxies must be carefully weighed in the development and implementation of CSC. Clarity is needed as to why specific comorbidities should lead to exclusion or lower prioritization for resources. There may be a fundamental ethical difference between excluding a patient because their condition significantly reduces long-term life expectancy, and excluding a patient because their condition significantly reduces their likelihood of surviving the acute illness that has led to their need for life support. But that distinction alone may not prove dispositive. How likely their survival is in the short term may matter as well. Giving equal priority to certain conditions that reduce short-term survival to some degree but are highly linked with race or socio-economic status, for example, may be justifiable on equity grounds. Yet as short-term survival becomes increasingly poor for certain comorbidities, arguments for equal access to scarce equipment may prove less convincing. Consensus on these challenging questions remains elusive. However, CSC that elucidate the rationale for these choices enable more meaningful equity analysis and are more conducive to widespread acceptance. In the absence of compelling reasons to include consideration of specific comorbid conditions, particularly if these are inequitably distributed between racial and ethnic groups as a result of persistent structural racism within American society, CSC would more equitably distribute resources by using a lottery system to break ties between patients who are equally acutely ill. Although none of the reviewed CSC suggested using a weighted lottery, the process recently developed for the allocation of scarce medications (e.g., novel antivirals) at the University of Pittsburg provides an interesting strategy for prioritizing more socially vulnerable individuals [49]. Further research is needed to determine the equity implications of such a strategy.

Crisis Standards of Care: Process

The development of CSC, while critically important to support clinicians and healthcare systems during times of crisis, must not be undertaken in a rushed or siloed manner. Failure to incorporate broad perspectives and public comment may lead to oversights or unintentional consequences. These may ultimately lead to CSC needing to be revised. For example, due to the equity concerns raised by clinicians, politicians, and disability activists, the Massachusetts CSC were revised 2 weeks after they were first published [17, 23]. Input from diverse individuals and stakeholders is critical to ensuring that CSC reflect the values of the populations they will affect. While ethical frameworks for allocation of scarce resources seek to provide the greatest good for the greatest number, interestingly, this may be at odds with what the general public may classify as a more equitable way of distributing in times of a pandemic [50]. Arriving at consensus with input from diverse stakeholders, with particular attention to the inclusion of historically marginalized groups, may prove crucial to ensuring the acceptance of CSC and the consequences of their implementation in the long term.

Failing to provide any guidance at the regional or state level may prove even more problematic than developing CSC with insufficient community input. Without objective and concrete guidance for resource allocation during times of scarcity, “first-come, first-served” remains the default triage process, thereby allowing patients who arrive sooner to receive care, even if they have a far lower likelihood of survival than someone who arrives shortly thereafter. Most people, including ethicists, agree that such a system is not in society’s best interest [51, 52]. Not only does this method fail to maximize the number of lives saved or allocate care in a health-preserving manner, but it raises grave equity issues of its own. Socio-economic factors may increase healthcare literacy and thus awareness of the need to seek care earlier during a crisis, while lower-income workers may not be able to leave their jobs to line up first. In addition, well-resourced patients may travel farther to seek hospitals where lines for critical equipment are shorter.

The absence of state-level guidance places the burden of decision making upon hospitals and often upon individual providers. Fewer than half of the hospitals in the country appear to have developed CSC [53]. At present, the majority of hospital administrators and physicians in the USA are upper-middle class (or wealthier) and white [54]. No matter how good their intentions, they are likely to be blind to biases built into protocols designed without external input. Clinicians in the field, forced to make rapid decisions, will inevitably bring their own biases—conscious and unconscious—into the triage process. This may affect both patient assessment and resource allocation decisions. These biases, if unchecked, may result in stark inequities in both care and survival at the population level.

In addition, leaving doctors in the field to make decisions about triage criteria is bound to take a significant emotional and psychological toll. This toll may weigh more heavily on physicians of color and those from lower socio-economic backgrounds if they consistently witness patients with identities similar to their own losing out in the triage process. Finally, it is worth noting that optics matter: Even if the allocation were to prove equitable, the long history of systemic and structural racism in the USA may lead patients and families who do not receive priority to conclude that bias by the individual hospital or physician was a factor in their assessment, a concern which can be mitigated—at least to some degree—by a region or state-wide policy.

Conclusion

There is wide variability in the existence and specificity of CSC across the USA. Although many states have recently updated or developed CSC, and others are actively working to do so, these processes should be collaborative with broad input from the affected community. Many of these decision-making criteria have implications for health equity. CSC may disproportionately impact historically disadvantaged populations due to inequities in comorbid condition prevalence, expected lifespan, and other systemic disadvantages that result from structural racism within American society. Failure to consider these factors will inevitably lead to the perpetuation of structural and historical inequities through the application of these standards.

Disclaimer

This manuscript represents original material, has not been previously published, is not under consideration for publication elsewhere, and has not been previously submitted to the Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. All of the authors have read and approved the final submitted version of the manuscript.

Appendix 1

State-level Crisis Standards of Care (CSC) as of May 3, 2020

Authors’ Contributions

Emily Cleveland Manchanda—literature search, data analysis, writing, editing; Charles Sanky—literature search, data analysis, writing, editing; Jacob Appel—writing, editing.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex M Azar, Determination that a public health emergency exists. (Jan. 31, 2020), available at https://www.phe.gov/emergency/news/healthactions/phe/Pages/2019-nCoV.aspx).

- 2.Proclamation on Declaring a National Emergency Concerning the Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak (Mar. 13, 2020), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/proclamation-declaring-nationalemergency-concerning-novel-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-outbreak/.

- 3.Gostin LO, Hanfling D, Hanson SL, Stroud C, Altevogt BM. Guidance for establishing crisis standards of care for use in disaster situations: a letter report: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed]

- 4.IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2012. Crisis standards of care: a systems framework for catastrophic disaster response. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed]

- 5.Stroud C, Hick JL, Hanfling D. Crisis standards of care: a toolkit for indicators and triggers: National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed]

- 6.Hougan M, Nadig L, Altevogt BM, Stroud C. Crisis standards of care: summary of a workshop series. National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed]

- 7.Hick JL, Hanfling D, Wynia MK, Pavia AT. Duty to plan: health care, crisis standards of care, and novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Washington, DC: NAM Perspectives. Discussion paper. National Academy of Medicine; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biddison LD, Berkowitz KA, Courtney B, de Jong CMJ, Devereaux AV, Kissoon N, Roxland BE, Sprung CL, Dichter JR, Christian MD, Powell T. Ethical considerations: care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. 2014;146:e145S–e155S. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Einav S, Hick JL, Hanfling D, Erstad BL, Toner ES, Branson RD, Kanter RK, Kissoon N, Dichter JR, Devereaux AV, Christian MD. Surge capacity logistics: care of the critically ill and Injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. CHEST. 2014;146:e17S–e43S. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hick JL, Biddinger PD. Novel coronavirus and old lessons — preparing the health system for the pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hick JL, Hanfling D. Rapid expert consultation on crisis standards of care for the COVID-19 pandemic. National Academy Press 2020.

- 12.Kendi, IX. Stop blaming black people for dying of the coronavirus: new data from 29 states confirm the extent of the racial disparities. April 2020. The Atlantic. (Accessed April 15, 2020, at https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/04/race-and-blame/609946/.)

- 13.Thebault R, Tran AB, Williams V. The coronavirus is infecting and killing black Americans at an alarmingly high rate. April 2020. The Washington Post. (Accessed April 18, 2020, at https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/04/07/coronavirus-is-infecting-killing-black-americans-an-alarmingly-high-rate-post-analysis-shows/?arc404=true).

- 14.Stafford K, Hoyer M, Morrison A. Outcry over racial data grows as virus slams black Americans. April 2020. ABC News. (Accessed April 18, 2020, at https://abcnews.go.com/US/wireStory/outcry-racial-data-grows-virus-slams-black-americans-70050611.)

- 15.Wendland T. Black communities are hit hardest by COVID-19 in Louisiana and elsewhere. April 2020. New Orleans Public Radio 89.9 WWNO. (Accessed April 18, 2020, at https://www.wwno.org/post/black-communities-are-hit-hardest-covid-19-louisiana-and-elsewhere).

- 16.New York State Department of Health. COVID 19 Tracker: Fatalities. 2020. (Accessed April 19, 2020, at https://covid19tracker.health.ny.gov/views/NYS-COVID19-Tracker/NYSDOHCOVID-19Tracker-Fatalities?%3Aembed=yes&%3Atoolbar=no&%3Atabs=n).

- 17.Crisis Standards of Care: Planning Guidance for the COVID-19 Pandemic. April 2020. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts Department of Public Health. (Accessed April 17, 2020, at https://d279m997dpfwgl.cloudfront.net/wp/2020/04/CSC_April-7_2020.pdf).

- 18.Prakash N. Doctors are concerned that black communities might not be getting access to coronavirus tests. March 2020. BuzzFeed News. (Accessed April 17, 2020, at https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/nidhiprakash/coronavirus-tests-covid-19-black).

- 19.Open Letter to Massachusetts Crisis Standards of Care Advisory Committee. April 2020. (Accessed April 17, 2020, at https://docs.google.com/document/d/13kGxuxmIIdxbo3X2Kh_i7ruyelSsXBzEiQRL73KK_Vc/edit).

- 20.Letter from the Massachusetts Coalition on Health Equity to Secretary Marylou Sudders calling for the reconsideration of the Massachusetts Crisis Standards of Care, April 17, 2020.

- 21.Cleveland Manchanda E, Couillard C, Sivashanker K. Inequity in crisis standards of care. New England Journal of Medicine 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Pressley A. Letter to governor baker regarding Massachusetts Department of Public Health’s current crisis standards of care guidelines. April 2020. (Accessed April 18, 2020, at https://pressley.house.gov/sites/pressley.house.gov/files/200413%20Crisis%20Standards%20of%20Care%20Letter.pdf).

- 23.Rep. Pressley Calls on Governor Baker to Rescind Crisis of Care Standards that Disproportionately Harm Communities of Color & Disability Community. April 2020. (Accessed April 18, 2020, at https://pressley.house.gov/media/press-releases/rep-pressley-calls-governor-baker-rescind-crisis-care-standards.)

- 24.Crisis Standards of Care: Planning Guidance for the COVID-19 Pandemic. April 2020. (Accessed April 25, 2020, at https://www.mass.gov/info-details/covid-19-state-of-emergency).

- 25.Technical Resources, Assistance Center, and Information Exchange (TRACIE). State Level Crisis Standards of Care. US Department of Health and Human Services: Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR). April 2020. (Accessed April 15, 2020 at https://files.asprtracie.hhs.gov/documents/4-9-20-state-level-csc-plans-guidance-policy.pdf).

- 26.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the working group on sepsis-related problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grissom CK, Brown SM, Kuttler KG, Boltax JP, Jones J, Jephson AR, Orme JF., Jr A modified sequential organ failure assessment score for critical care triage. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2010;4:277–284. doi: 10.1001/dmp.2010.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rahmatinejad Z, Reihani H, Tohidinezhad F, Rahmatinejad F, Peyravi S, Pourmand A, Abu-Hanna A, Eslami S. Predictive performance of the SOFA and mSOFA scoring systems for predicting in-hospital mortality in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37:1237–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cardenas-Turanzas M, Ensor J, Wakefield C, et al. Cross-validation of a sequential organ failure assessment score-based model to predict mortality in patients with cancer admitted to the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2012;27:673–680. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, Fushimi K, Graham P, Hider P, Januel JM, Sundararajan V. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:676–682. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stieb M. What coronavirus triage could look like in American hospitals. March 2020. NY Magazine. (Accessed April 16, 2020, at https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2020/03/what-coronavirus-triage-could-look-like-in-u-s-hospitals.html).

- 34.Pezzino G, Simpson SQ. Guidelines for the use of modified health care protocols in acute care hospitals during public health emergencies, Second Revision. Kansas Department of Health and Environment. September 2013. (Accessed April 18, 2020, at https://www.kdheks.gov/cphp/download/Crisis_Protocols.pdf).

- 35.New York State Task Force on Life and the Law. Ventilator Allocation Guidelines. New York State Department of Health. November 2015. (Accessed April 18, 2020, at https://www.health.ny.gov/regulations/task_force/reports_publications/docs/ventilator_guidelines.pdf).

- 36.Technical Resources, Assistance Center, and Information Exchange (TRACIE). SOFA Score: What is it and how to use it in triage. US Department of Health and Human Services: Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR). January 2017. (Accessed April 2020, at https://files.asprtracie.hhs.gov/documents/aspr-tracie-sofa-score-fact-sheet.pdf).

- 37.Hatzfeld JJ, LaVeist TA, Gaston-Johansson FG. Racial/ethnic disparities in the prevalence of selected chronic diseases among US Air Force members, 2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E112. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gravlee CC. How race becomes biology: embodiment of social inequality. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2009;139:47–57. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status and health: complexities, ongoing challenges and research opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:69–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen J, Vargas-Bustamante A, Mortensen K, Ortega AN. Racial and ethnic disparities in health care access and utilization under the Affordable Care Act. Med Care. 2016;54:140–146. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hardeman RR, Medina EM, Kozhimannil KB. Structural racism and supporting black lives-the role of health professionals. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2113–2115. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1609535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lackland DT. Racial differences in hypertension: implications for high blood pressure management. Am J Med Sci. 2014;348:135–138. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haire-Joshu D, Hill-Briggs F. The next generation of diabetes translation: a path to health equity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:391–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Galaviz KI, Varughese R, Agan BK, et al. The intersection of HIV, diabetes, and race: exploring disparities in diabetes care among people living with HIV. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care. 2020;19:2325958220904241. doi: 10.1177/2325958220904241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ortiz A. Burden, access and disparities in kidney disease: chronic kidney disease hotspots and progress one step at a time. Clin Kidney J. 2019;12:157–159. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfz026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cooper S-A, McLean G, Guthrie B, McConnachie A, Mercer S, Sullivan F, Morrison J. Multiple physical and mental health comorbidity in adults with intellectual disabilities: population-based cross-sectional analysis. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:110. doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0329-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bahk J, Kang H-Y, Khang Y-H. The life expectancy gap between registered disabled and non-disabled people in Korea from 2004 to 2017. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2593. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16142593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pennsylvania Department of Health. Interim Pennsylvania Crisis Standards of Care for Pandemic Guidelines, Version 2. April 2020. (Accessed April 17, 2020, at https://www.health.pa.gov/topics/Documents/Diseases%20and%20Conditions/COVID-19%20Interim%20Crisis%20Standards%20of%20Care.pdf.)

- 49.University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine: Department of Critical Care Medicine. Model hospital policy for fair allocation of scarce medications to treat COVID-19. (Accessed June 12, 2020, at https://ccm.pitt.edu/sites/default/files/2020-05-28b%20Model%20hospital%20policy%20for%20allocating%20scarce%20COVID%20meds.pdf.)

- 50.Krütli P, Rosemann T, Törnblom KY, Smieszek T. How to fairly allocate scarce medical resources: ethical argumentation under scrutiny by health professionals and lay people. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kanter RK. Would triage predictors perform better than first-come, first-served in pandemic ventilator allocation? Chest. 2015;147:102–108. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tabery J, Mackett CW. Ethics of triage in the event of an influenza pandemic. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2008;2:114–118. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e31816c408b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matheny Antommaria AH, Gibb TS, McGuire AL, et al. Ventilator triage policies during the COVID-19 pandemic at U.S. hospitals associated with members of the Association of Bioethics Program Directors. Ann Intern Med 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.United States Census Bureau. American community survey public use microdata sample - 1 year estimate. 2017. (Accessed April 19, 2020, at https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/technical-documentation/pums.html).