Abstract

Accumulated experience supports the efficacy of allogenic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in arresting the progression of childhood-onset cerebral form of adrenoleukodystrophy in early stages. For adulthood-onset cerebral form of adrenoleukodystrophy, however, there have been only a few reports on haematopoietic stem cell transplantation and the clinical efficacy and safety of that for adulthood-onset cerebral form of adrenoleukodystrophy remain to be established. To evaluate the clinical efficacy and safety of haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, we conducted haematopoietic stem cell transplantation on 12 patients with adolescent-/adult-onset cerebral form/cerebello-brainstem form of adrenoleukodystrophy in a single-institution-based prospective study. Through careful prospective follow-up of 45 male adrenoleukodystrophy patients, we aimed to enrol patients with adolescent-/adult-onset cerebral form/cerebello-brainstem form of adrenoleukodystrophy at early stages. Indications for haematopoietic stem cell transplantation included cerebral form of adrenoleukodystrophy or cerebello-brainstem form of adrenoleukodystrophy with Loes scores up to 13, the presence of progressively enlarging white matter lesions and/or lesions with gadolinium enhancement on brain MRI. Clinical outcomes of haematopoietic stem cell transplantation were evaluated by the survival rate as well as by serial evaluation of clinical rating scale scores and neurological and MRI findings. Clinical courses of eight patients who did not undergo haematopoietic stem cell transplantation were also evaluated for comparison of the survival rate. All the patients who underwent haematopoietic stem cell transplantation survived to date with a median follow-up period of 28.6 months (4.2–125.3 months) without fatality. Neurological findings attributable to cerebral/cerebellar/brainstem lesions became stable or partially improved in all the patients. Gadolinium-enhanced brain lesions disappeared or became obscure within 3.5 months and the white matter lesions of MRI became stable or small. The median Loes scores before haematopoietic stem cell transplantation and at the last follow-up visit were 6.0 and 5.25, respectively. Of the eight patients who did not undergo haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, six patients died 69.1 months (median period; range 16.0–104.1 months) after the onset of the cerebral/cerebellar/brainstem lesions, confirming that the survival probability was significantly higher in patients with haematopoietic stem cell transplantation compared with that in patients without haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (P = 0.0089). The present study showed that haematopoietic stem cell transplantation was conducted safely and arrested the inflammatory demyelination in all the patients with adolescent-/adult-onset cerebral form/cerebello-brainstem form of adrenoleukodystrophy when haematopoietic stem cell transplantation was conducted in the early stages. Further studies are warranted to optimize the procedures of haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for adolescent-/adult-onset cerebral form/cerebello-brainstem form of adrenoleukodystrophy.

Keywords: adrenoleukodystrophy, haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, nonmyeloablative preparative regimen, adult cerebral form, cerebello-brainstem form

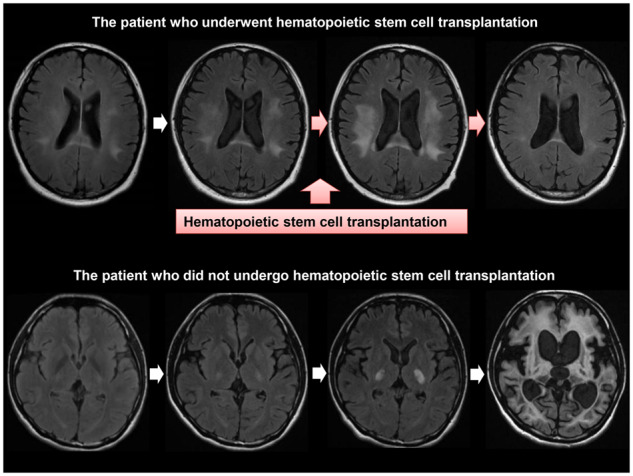

Presently, there are only a few reports on allogenic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for adult-onset adrenoleukodystrophy. Matsukawa et al. report that survival probability was significantly higher in 12 patients with adolescent-/adult-onset cerebral/cerebello-brainstem form of adrenoleukodystrophy who underwent haematopoietic stem cell transplantation than that in 8 patients who did not undergo haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation arrested the inflammatory demyelination in all the patients.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD) is an X-linked neurological disorder caused by mutations in ABCD1 encoding the ALD protein in peroxisomes, which leads to increased levels of very-long-chain saturated fatty acids (VLCFAs) in blood and various tissues (Igarashi et al., 1976; Moser et al., 1981; Tsuji et al., 1981; Mosser et al., 1993). Ages at onset and clinical presentations are highly variable, including childhood-/adolescent-/adult-onset cerebral form of ALD (CCALD/AdolCALD/ACALD), adrenomyeloneuropathy (AMN), cerebello-brainstem form of ALD, Addison disease only, asymptomatic male and symptomatic heterozygotes (Ohno et al., 1984; Suzuki et al., 2005; Moser et al., 2007). These various phenotypes are observed even in patients carrying the same mutation without any obvious genotype–phenotype correlations (Takano et al., 1999; Matsukawa et al., 2011).

In CCALD, once neurological symptoms appear, inflammatory demyelination progresses rapidly and patients become bedridden within a few years. Allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) was first conducted on a child with early-stage CCALD, who showed the arrest of demyelinating lesions (Aubourg et al., 1990). Subsequently, HSCT was conducted on many CCALD patients, which showed convincing beneficial effects when conducted in early stages (Shapiro et al., 2000; Peters et al., 2004).

The clinical presentations of AdolCALD and ACALD are similar to those of CCALD. Although patients with AMN initially show slowly progressive lower limb spasticity and pyramidal weakness, ∼50% of the patients develop cerebral form of ALD within 10 years after onset (AMN with later development of cerebral form of ALD) (Suzuki et al., 2005). Approximately 50% of patients with cerebello-brainstem form of ALD develop the cerebral form within 2 years (cerebello-brainstem form with later development of cerebral form of ALD) (Suzuki et al., 2005). Patients with AMN with later development of cerebral form of ALD and cerebello-brainstem form with later development of cerebral form of ALD show a rapidly deteriorating clinical course similarly to patients with ACALD (Suzuki et al., 2005).

In contrast to HSCT for CCALD, however, HSCT for ACALD has been conducted only on a few patients to date (Hitomi et al., 2005; Fitzpatrick et al., 2008; Saute et al., 2016; Kühl et al., 2017; Waldhüter et al., 2019). Recently, a multicenter-based retrospective study of long-term outcomes of HSCT in 14 patients with ACALD has been reported (Kühl et al., 2017). Although the arrest of progressive cerebral lesions was observed in five patients, three patients showed the progression of brain MRI lesions >1 year after HSCT and eight patients died (Hitomi et al., 2005; Fitzpatrick et al., 2008; Saute et al., 2016; Kühl et al., 2017). A single center-based retrospective study of additional seven ACALD patients in addition to the eight patients in the previous report (Kühl et al., 2017) has also been reported (Waldhüter et al., 2019). Of additional seven patients with ACALD, two patients died after HSCT. Thus, the clinical efficacy and safety of HSCT for ACALD remain to be established.

We herein report the clinical outcomes of 12 patients with AdolCALD/ACALD and cerebello-brainstem form of ALD treated with HSCT in a single-institution-based prospective study. Comparison of the survival time after the onset of cerebral/cerebellar/brainstem lesions between the 12 HSCT-treated patients and the 8 non-HSCT-treated patients convincingly supports the clinical efficacy and safety of HSCT based on patient selection at early stages.

Materials and methods

Patients

Forty-five male patients with ALD were enrolled in this study prospectively from September 29, 2003, to October 31, 2018. The average (SD) follow-up period was 5.2 (4.3) years. When cerebral/cerebellar/brainstem lesions were detected by MRI, we then confirmed the progressive enlargement of the lesions by brain MRI with gadolinium (Gd) enhancement. Indications for HSCT included cerebral form of ALD or cerebello-brainstem form of ALD with Loes scores (Loes et al., 1994) up to 13, the presence of progressively enlarging white matter lesions and/or lesions with Gd enhancement on brain MRI. Patients with severe neuropsychiatric symptoms that made coordinated treatment during HSCT difficult were not enrolled.

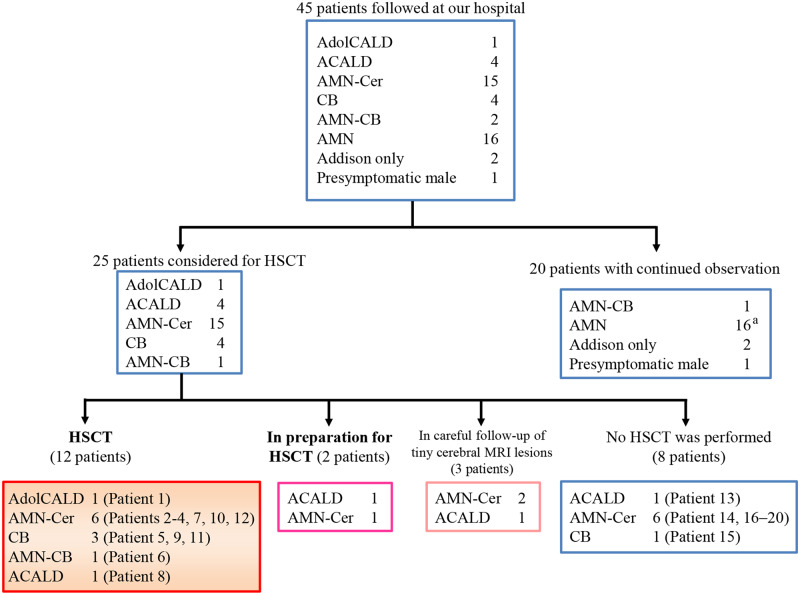

Of the 45 ALD patients, 25 patients were considered for HSCT, among whom 12 patients were treated (Fig. 1 and Table 1A). We did not conduct HSCT on eight patients for the following reasons: five patients were in advanced stages not fulfilling the inclusion condition and three patients declined to undergo HSCT (Fig. 1 and Table 1B). Three patients with minute white matter lesions without any neurological symptoms were under careful observation. The other two patients were at the stage of preparing for HSCT.

Figure 1.

Prospective follow-up of 45 patients with adolescent/adult ALD and enrolment for HSCT. Forty-five male patients with ALD were enrolled in this study in a prospective manner from September 29, 2003, to October 31, 2018. Among them, 25 patients were considered for HSCT on the basis of detection of MRI lesions in the cerebrum, cerebellum or brainstem. HSCT was conducted on 12 patients. We did not conduct HSCT on eight patients because five patients were in advanced stages (Patients 13, 14, 16, 17 and 19) and three declined to undergo HSCT (Patients 15, 18 and 20). CB = cerebello-brainstem form of ALD; AMN-CB = AMN with later development of cerebello-brainstem form of ALD. aOne patient with AMN died of a brain haemorrhage.

Table 1A.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who underwent HSCT for adult/adolescent cerebral form of ALD and cerebello-brainstem form of ALD

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype | AdolCALD | AMN-Cer | AMN-Cer | AMN-Cer | Cerebello-brainstem | AMN-cerebello-brainstem | AMN-Cera | ACALD | Cerebello- brainstem | AMN-Cer | Cerebello-brainstem | AMN-Cer |

| Age at onset of neurological symptoms | 16 | 30 | 31 | 20 | 18 | 37 | 25 | 42 | 23 | 24 | 20 | 25 |

| Age at onset of cerebral/ cerebellar/brainstem lesions | 16 | 33 | 39 | 24 | 18 | 39 | 43 | 42 | 23 | 28 | 20 | 32 |

| Age at HSCT | 18 | 35 | 40 | 26 | 21 | 42 | 45 | 44 | 25 | 29 | 22 | 34 |

| Interval from the onset of cerebral/cerebellar/brainstem lesions to HSCT | 1.9 yearsb | 1.9 yearsc | 1.1 yearsc | 1.8 yearsc | 3.5 yearsb | 3.7 yearsc | 2.2 yearsc | 2.5 yearsb | 2.2 yearsb | 11 monthsb | 2.8 yearsb | 1.3 yearsc |

| Mutation in ABCD1 | c.1552C>T (p.Arg518Trp) | Large deletion including exons 3–10 and large insertiond | c.1999C>A (p.His667Asn) | c.1825G>A (p.Glu609Lys) | c.1825G>A (p.Glu609Lys) | c.1661G>A (p.Arg554His) | c.829G>A (p.Gly277Arg) | c.1415_1416delAG (p.Gln472Argfs*83) | c.521A>C (p.Tyr174Ser) | c.521A>G (p.Tyr174Cys) | c.521A>C (p.Tyr174Ser) | Large deletion including exons 3–10e |

| Neurological findings before HSCT | Ataxia, dysarthria, dysphagia, pyramidal signs | Pyramidal signs, dysesthesia of the feet | Pyramidal weakness, ataxia | Dysarthria, dysphagia, pyramidal signs, ataxia, bladder and bowel disturbance, impotence | Ataxia, dysarthria, dysphagia, pyramidal signs, decreased superficial and deep sensation | Pyramidal weakness, ataxia | Pyramidal weakness, decreased superficial and deep sensation, bladder and bowel disturbance, impotence | Apathy, cognitive decline (WAIS-III: FIQ 70, VIP88, PIQ 59, MMSE 27), pyramidal weakness, spinal automatism, bladder and bowel disturbance | Ataxia, dysarthria, dysphagia, pyramidal weakness, decreased deep sensation, bladder and bowel disturbance | Dysarthria, dysphagia, small voice, vertigo, pyramidal weakness, decreased superficial and deep sensation, bladder and bowel disturbance, impotence | Ataxia, dysarthria, pyramidal weakness, decreased superficial and deep sensation, bowel disturbance | Pyramidal signs, ataxia, cognitive decline (WAIS-III: FIQ 85, VIP103, PIQ 65, MMSE 28), bladder disturbance |

| EDSS/Barthel Index/ALD-DRS before HSCT | 2.5/100/I | 2.5/100/I | 2.0/95/I | 7.0/70/III | 6.5/100/II | 6.0/100/II | 6.5/95/II | 3.5/90/II | 4.0/100/II | 9.0/10/III | 3.0/100/I | 3.5/100/I |

| MRI findings | ||||||||||||

| Loes score before HSCT | 11 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 7.5 | 6.5 | 5.5 | 8.5 | 5 | 13 |

| Affected lesionsf | +/−/−/+ | −/−/+/+ | −/−/−/− | −/−/−/+ | −/−/−/+ | −/−/−/+ | +/+/+/− | +/−/+/− | +/−/−/+ | +/−/−/− | +/−/−/+ | **/**/+/− |

| Parietooccipital/frontal/temporal/cerebellum/brainstem/pyramidal tracts/corpus callosum/others | +/+/**/− | −/+/−/+ | +/+/+/− | +/+/−/− | +/−/−/− | −/−/−/− | +/+/+/+ | +/+/+/− | −/+/−/− | **/**/−/− | −/+/−/− | +/+/**/− |

| Progression of white matter lesions before HSCT | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gd enhancement on brain MRI before HSCT | Enhanced | Enhanced | Enhancedg | Enhanced | Enhanced | Not enhanced | Enhancedh | Enhanced | Enhanced | Enhanced | Not enhanced | Enhanced |

AMN-cerebello-brainstem = AMN with later development of cerebello-brainstem form; WAIS-III = Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 3rd edition; FIQ = full scale intelligence quotient; VIQ = verbal intelligence quotient; PIQ = performance intelligence quotient; ALD-DRS = X-linked ALD-disability rating scale, AMN-Cer = AMN with later development of cerebral form of ALD, EDSS = expanded disability status scale, MMSE = Mini–Mental State Examination.

Patient 7 was diagnosed as having Addison’s disease at age 14, and he showed spasticity of lower limbs at age 25.

Interval from the first detection of clinical symptoms attributable to cerebral/cerebellar/brainstem MRI lesions to HSCT.

Interval from the first detection of cerebral/cerebellar/brainstem MRI lesions other than pyramidal tracts to HSCT.

Large deletion from chromosome X: 152, 997, 187 to 153, 011, 810 (GRCh37/hg19); followed by ATC 3-bp insertion with large insertion derived from chromosome 13: 113, 874, 123–113, 983, 144; accompanied by 9-bp deletion of CTACAGGCA from chromosome X: 153, 011, 834 to 153, 011, 842.

Large deletion from chromosome X: 152, 997, 857 to 153, 029, 285 (GRCh37/hg19).

The affected white matter lesions were graded as follows: −, no; +, moderate; **, extensive.

The auditory pathway in the brainstem was Gd-enhanced 9.5 months before HSCT, but Gd enhancement was not obvious 0.8 months before HSCT.

Gd enhancement was observed in the splenium of the corpus callosum 4.9 months (double-dose infusion) and 0.3 months (single-dose infusion) before HSCT.

Table 1B.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who did not undergo HSCT for adult cerebral form of ALD and cerebello-brainstem form of ALD

| Patient | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype | ACALD | AMN-Cer | Cerebello- brainstem | AMN-Cer | AMN-Cer | AMN-Cer | AMN-Cer | AMN-Cer |

| Age at onset of neurological symptoms | 76 | 36 | 39 | 33 | 25 | 18 | 28 | 43 |

| Age at onset of cerebral/cerebellar/brainstem lesions | 76 | 47 | 39 | 45 | 34 | 29 | 31 | 52 |

| Age at considering HSCT | 76 | 47 | 55 | 48 | 35 | 29 | 33 | 53 |

| Interval from the cerebral/cerebellar/brainstem onset to the time when HSCT was considered | 3 monthsa | 7 monthsa | 15.3 yearsa | 3.2 yearsa | 9 monthsa | 7 monthsb | 1.7 yearsb | 1.5 yearsa |

| Mutation in ABCD1 | c.566G>A (p.Arg189Gln) | c.1850G>A (p.Arg617His) | c.1619T>C (p.Phe540Ser) | c.1850G>A (p.Arg617His) | c.869C>G (p.Ser290Trp) | c.841dupT (p.Tyr281Leufs) | c.1415_1416delAG (p.Gln472Argfs*83) | c.1876G>A (p.Ala626Thr) |

| Neurological findings at time of considering HSCT | Disturbance of consciousness, visual hallucination, dysphagia, pyramidal signs | Cognitive decline, dysarthria, pyramidal weakness, decreased superficial and deep sensation, ataxia, urinary frequency | Dysarthria, vertigo, ataxia, pyramidal signs, character change, cognitive decline | Dysarthria, dysphagia, ataxia, pyramidal weakness, character change, cognitive decline, urinary frequency, impotence | Pyramidal weakness, dysphagia, dysarthria, decreased superficial and deep sensation, bladder and bowel disturbance, myoclonus, cognitive decline | Pyramidal weakness, ataxia, dysphagia, dysarthria, decreased superficial and deep sensation, bladder and bowel disturbance, impotence | Impaired attention, frontal release signs, slurred speech, pyramidal weakness, decreased superficial sensation, bladder and bowel disturbance, impotence | Impaired attention, emotional incontinence, cognitive decline, ataxia, pyramidal weakness, urinary frequency |

| EDSS/Barthel Index/ALD-DRS at time of considering HSCT | N.A./0/N.A. | 2.0/100/II | 3.5/100/I | N.A./5/N.A. | 9.0/5/III | 8.0/50/III | 3.5/90/N.A. | 2.0/100/I |

| EDSS/Barthel Index/ALD-DRS (months after considering HSCT) | 10.0/0/IV (13) | 10.0/0/IV (22) | 6.5/50/III (98) | 10.0/0/IV (66) | 10.0/0/IV (68) | 10.0/0/IV (64) | 10.0/0/IV (47) | 7.0/25/III (20) |

| MRI findings | ||||||||

| Loes score at time of considering HSCT | 13.5 | 11 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 3.5 | 5 | 7 |

| Loes score (years after considering HSCT) | 13.5 (0.1) | N.A. | 8 (8.1) | 6 (0.9) | 8 (0.5) | 34 (4.8) | 16 (2.5) | N.A. |

| Affected lesionsc | **/+/**/− | **/**/**/− | −/−/−/+ | +/+/−/+ | −/−/−/+ | +/−/−/+ | +/−/−/+ | +/−/−/+ |

| Parietooccipital/frontal/temporal/cerebellum/ brainstem/pyramidal tracts/corpus callosum/others | −/**/**/− | −/+/**/− | +/+/−/− | +/+/−/− | +/**/−/− | **/**/−/− | +/+/−/− | +/+/+/− |

| Progression of white matter lesions | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gd enhancement on brain MRI at time of considering HSCT | Enhanced | Enhanced | Enhancedd | Enhanced | Enhanced | Enhanced | Enhancede | Enhanced |

N.A. = not available; ALD-DRS = X-linked ALD-disability rating scale, AMN-Cer = AMN with later development of cerebral form of ALD, EDSS = expanded disability status scale.

Interval from the first detection of clinical symptoms attributable to cerebral/cerebellar/brainstem MRI lesions to the time when HSCT was considered.

Interval from the first detection of cerebral/cerebellar/brainstem MRI lesions other than pyramidal tracts to HSCT.

Affected white matter lesions were graded as follows: −, no; +, moderate; **, extensive.

The dorsal part in the brainstem was Gd-enhanced at the time when we considered HSCT, but Gd enhancement was not obvious 7 months later.

A double dose of the Gd contrast was injected at the time when we performed MRI when we considered HSCT.

This is a single-institution-based prospective study. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Tokyo.

Allogenic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Bone marrow transplantation from unrelated donors was performed in Patients 1–7, 9, 10 and 12 [human leukocyte antigen-8/8 allele-matched donors in Patients 1–3, 5, 7, 10 and 12 and one-antigen (DRB1) mismatched donors in Patients 4, 6 and 9], and that from allele-matched related donors was performed in Patients 8 and 11 (Table 2). Allele-matched female siblings carrying heterozygous ABCD1 mutations were not considered as candidate donors. Details of the nonmyeloablative preparative regimens and prophylaxis of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) are summarized in Table 2.

Outcome evaluations after allogenic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Survival probability was evaluated using Kaplan–Meier plots. We determined survival time from the earliest time of either the onset of cerebral/cerebellar/brainstem MRI lesions or the onset of clinical symptoms attributable to cerebral/cerebellar/brainstem lesions. Clinical rating scale scores including the expanded disability status scale (Kurtzke, 1983), the Barthel Index (Mahoney and Barthel, 1965), and X-linked ALD-disability rating scale (Peters et al., 2004), neurological findings, brain MRI findings and blood examination results were evaluated prospectively before and after HSCT. The Loes score (Loes et al., 1994) on brain MRI was evaluated by the radiologist (H.M.) and the neurologist (T.M.) independently, and we made the ultimate decision by mutual agreement.

Mutational analyses of ABCD1

We conducted mutational analysis of ABCD1 as described previously (Matsukawa et al., 2011). For the analysis of large-deletion and large-insertion mutations in ABCD1, we employed GS junior (F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland) to determine breakpoints in ABCD1 and fluorescence in situ hybridization.

Very-long-chain saturated fatty acid measurement

The VLCFA levels in plasma and red blood cell membrane sphingomyelin (C24:0/C22:0, C25:0/C22:0 and C26:0/C22:0) were measured using gas–liquid chromatography–quadrupole mass spectrometry as described previously (Tsuji et al., 1981; Ohno et al., 1984).

Chimerism analysis after allogenic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation

We performed chimerism analysis by deep sequencing of ABCD1 PCR products employing MiSeq (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) or by detecting ABCD1 mutations employing QX200 droplet digital PCR (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) using genomic DNAs extracted from peripheral white blood cells (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). We also conducted microsatellite analysis for sex-matched HSCT and fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis for sex-mismatched HSCT using bone marrow cells.

Statistical analysis

We analysed the survival time of patients who underwent HSCT and those who did not using Kaplan–Meier plots and the log-rank test using EZR (Easy R) (Kanda, 2013). Statistical significance was defined as a P-value of <0.05.

Data availability

The data supporting these findings are available upon request.

Results

Clinical outcomes

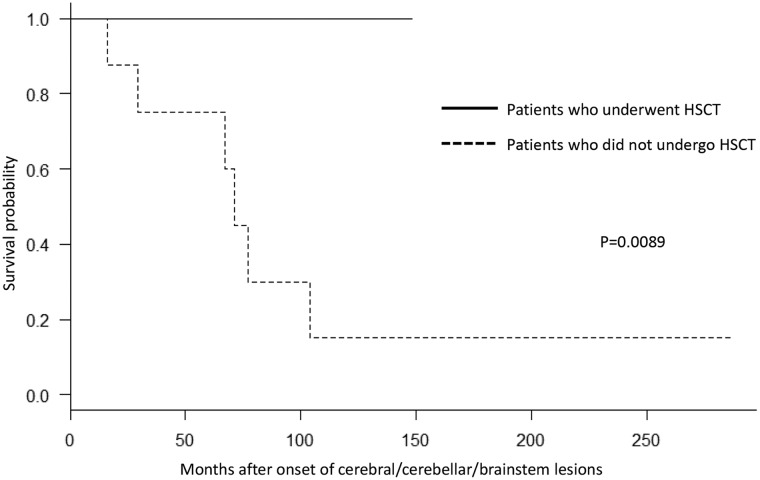

All the 12 patients have achieved neutrophil engraftment and survived to date with a median follow-up period of 28.6 months (4.2–125.3 months) after HSCT (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Table 3). To evaluate the efficacy of HSCT, we conducted Kaplan–Meier survival analysis by comparing the survival time from the onset of cerebral/cerebellar/brainstem involvement between the 12 patients who underwent HSCT and the 8 patients who did not. Six of the eight patients who did not undergo HSCT died 69.1 months (median period; range 16.0–104.1 months) after the onset of cerebral/cerebellar/brainstem involvement (Fig. 2 and Table 1B). The remaining two patients became wheelchair bound owing to disease progression. The survival probability was significantly higher in patients with ALD who underwent HSCT than in those who did not (P = 0.0089) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Survival probability of HSCT-treated and non-HSCT-treated ALD patients. We performed Kaplan–Meier analysis and the log-rank test for patients with ALD who underwent HSCT and for those who did not. The horizontal axis shows months after the onset of cerebral/cerebellar/brainstem lesions. The vertical axis shows the survival probability of patients with ALD. The solid line shows the survival probability of patients with ALD who underwent HSCT, and the dotted line shows the survival probability of those who did not. Survival probability was significantly different between patients with ALD who underwent HSCT and those who did not (P = 0.0089). The numbers of Patients 0, 50, 100, 150, 200 and 250 months after the onset of cerebral/cerebellar/brainstem lesions were 12, 7, 2, 0, 0 and 0 among those who underwent HSCT and 8, 5, 2, 1, 1 and 1 among those who did not undergo HSCT, respectively.

Table 2.

Summary of HSCT

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLA matching (A, B, C, DRB1) | 8/8 HLA allele- matched unrelated donor | 8/8 HLA all ele-matched unrelated donor | 8/8 HLA allele-matched unrelated donor | One-antigen (DRB1)- mismatched unrelated donor | 8/8 HLA allele-matched unrelated donor | One-antigen (DRB1)- mismatched unrelated donor | 8/8 HLA allele-matched unrelated donor | 8/8 HLA allele-matched related donor | One-antigen (DRB1)-mismatched unrelated donor | 8/8 HLA allele-matched unrelated donor | 8/8 HLA allele-matched related donor | 8/8 HLA allele-matched unrelated donor |

| Interval from application for bank donors to HSCT (months) | 3 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 4 | Related donor | 4 | 5 | Related donor | 8 |

| Stem cell source | Bone marrow | Bone marrow | Bone marrow | Bone marrow | Bone marrow | Bone marrow | Bone marrow | Bone marrow | Bone marrow | Bone marrow | Bone marrow | Bone marrow |

| Preparative regimen for HSCT | Bu, Cy, TLI | Bu, Cy, TBI | Bu, Cy, TBI | Flu, Mel, ATG, TBI | Flu, Mel, ATG, TBI | Flu, Mel, ATG, TBI | Flu, Mel, ATG, TBI | Flu, Mel, TBI | Flu, Mel, ATG, TBI | Flu, Mel, ATG, TBI | Flu, Mel, TBI | Flu, Mel, ATG, TBI |

| Prophylaxis of GVHD | CSPa, MTXb | TACc, MTXb | TACc, MTXb | TACc, MTXb | TACc, MTXb | TACc, MTXb | TACc, MTXb | TACc, MTXb | TACc, MTXb | TACc, MTXb | TACc, MTXb | TACc, MTXb |

| GVHD | ||||||||||||

| Acute GVHD | Grade III | Grade I | None | Grade I | None | Grade I | None | None | None | None | Grade I | None |

| Chronic GVHD | BO (5 months) | None | Dry eye (2.5 years), oral mucositis (2.6 years) | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

Bu = busulfan (3.2 mg/kg/day, 2 days); Cy = cyclophosphamide (60 mg/kg/day, 2 days); TLI = total lymphoid irradiation (7.5 Gy/day, 1 day); TBI = total body irradiation with brain shielding (4 Gy/day, 1 day); Flu = fludarabine (30 mg/m2/day, 5 days); Mel = melphalan (140 mg/m2/day, 1 day); ATG = rabbit antithymocyte globulin (ThymoglobulinⓇ, 2.5 mg/kg/day, 2 days); CSP = cyclosporine; MTX = methotrexate; TAC = tacrolimus; BO = bronchiolitis obliterans; HLA = human leukocyte antigen.

Cyclosporine was started on day −1 at a dose of 3 mg/kg/day by continuous infusion, and the dose was adjusted to maintain a blood concentration of around 500 ng/ml.

Methotrexate was administered at a dose of 15 mg/m2 on day 1 and 10 mg/m2 on days 3, 6 and 11 in Patient 6, 10 mg/m2 on day 1 and 7 mg/m2 on days 3, 6 and 11 in Patients 1–3, 5, 7, 9, 10 and 12 and 10 mg/m2 on day 1 and 7 mg/m2 on days 3 and 6 in Patients 4, 8 and 11.

Tacrolimus was started on day −1 at a dose of 0.03 mg/kg/day by continuous infusion, and the dose was adjusted to maintain a blood concentration of around 15 ng/ml.

Table 3.

Summary of clinical outcomes of HSCT

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up period after HSCT (years) | 10.4 | 6.7 | 4.9 | 4.6 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Neurological outcome | Stable for 10.4 years. Dysarthria improved, lower limb weakness progressed graduallya | Stable for 6.7 years | Stable for 4.9 years | Stable for 4.6 years. Dysarthria and dysphagia improved, lower limb weakness slightly progressed till 1 month after HSCT | Stable for 3.0 years. Dysarthria improved, truncal ataxia slightly progressed till 9 months after HSCT | Stable for 2.7 years | Stable for 2.1 years. Gait speed decreased till 8 months after HSCTb | Stable for 1.5 years | Stable for 0.7 years. Ataxia and lower limb weakness slightly progressed till 2 months after HSCT | Stable for 0.5 years.Small voice and pyramidal weakness substantially improved, dysphagia, deep sensation and bowel disturbance improved | Stable for 0.4 years. Decreased superficial sensation spread to the trunk/upper limbs and right dominant spasticity of lower limbs slightly progressed till 2 months after HSCT | Stable for 0.3 years. Pyramidal weakness and bladder disturbance slightly progressed till 2 months after HSCT |

| EDSS/Barthel Index/ALD-DRS (months after HSCT) | 8.5/55/II (95) | 2.0/100/I (79) | 3.5/90/I (12) | 7.0/40/III (26) | 6.5/85/II (13) | 6.0/100/II (24) | 6.5/90/II (24) | 3.0/90/II (14) | 6.5/85/III (3) | 8.5/15/III (1) | 6.0/85/II (2) | 5.0/85/II (2) |

| C26:0/C22:0 after HSCT (normal range 0.003–0.006) | 0.014 | 0.028 | 0.016 | 0.021 | 0.019 | 0.032 | 0.016 | 0.023 | 0.022 | 0.033 | 0.019 | N.T.c |

| Percentage of DNAs from the recipient (months after HSCT)d | 0.03% (95) | <0.01% (50) | 0.06% (12) | 0.06% (26) | 0.42% (5) | 0.08% (11) | 0.05% (9) | 0.43% (2) | 0.12% (2) | 0.17% (1) | 0.62% (2) | N.T.c |

| MRI findings | ||||||||||||

| Brain MRI after HSCT | Reduction in size of lesions of auditory pathway and splenium of corpus callosum. Atrophic changes in cerebellum and brainstem | Reduction in size of temporal and cerebellar lesions | Reduction in size of brainstem lesions | Reduction in size of pyramidal tract and cerebellar lesions. Atrophic changes in cerebellum and brainstem | Stabilization of enlargement of white matter lesions. Atrophic changes in cerebellum and brainstem | Stabilization of enlargement of white matter lesions | Reduction in size of frontal, parietal, occipital and temporal lesions | Stabilization of enlargement of white matter lesions | Reduction in size of pyramidal tract in brainstem, middle cerebellar peduncles and cerebellar lesions | Reduction in size of pyramidal tract and auditory pathway lesions | Stabilization of enlargement of white matter lesions | Stabilization of enlargement of white matter lesions |

| Loes scores before HSCT | 11 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 7.5 | 6.5 | 5.5 | 8.5 | 5 | 13 |

| Loes scores after HSCT (years after HSCT) | 12 (3.1) | 1.5 (6.7) | 2 (4.4) | 5 (3.1) | 7 (1.1) | 2 (1.9) | 5.5 (2.0) | 6.5 (1.2) | 5 (0.5) | 8.5 (0.4) | 5 (0.2) | 13 (0.1) |

| Gd enhancement on brain MRI before HSCT | Enhanced | Enhanced | Enhancede | Enhanced | Enhanced | Not enhanced | Enhanced | Enhanced | Enhanced | Enhanced | Not enhanced | Enhanced |

| Gd enhancement on brain MRI after HSCT (months after HSCT) | Not enhanced (37) | Not enhanced (80)f | Not enhanced (12) | Not enhanced (12) | Not enhanced (13) | Not enhanced (1) | Not enhanced (1) | Not enhanced (14) | Not enhanced (6) | Obscuredg (1) | Not enhanced (3) | Obscuredg (2) |

N.T. = not tested; ALD-DRS = X-linked ALD-disability rating scale, EDSS = expanded disability status scale.

Owing to lower limb weakness, patients’ activities of daily living decreased. Patient 1 spends a lot of time in a seated position, but he can move to his portable toilet with a grab bar.

He encountered a traffic accident with a right tibiofibular fracture 1.4 years after HSCT, which impaired his gait.

We have not measured the VLCFA levels in plasma sphingomyelin and performed chimerism analysis using peripheral white blood cells for Patient 12 because HSCT has been conducted very recently. The fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of bone marrow cells a month after HSCT in Patient 12 showed that the percentage of cells from the recipient with respect to that from the donor was 0.5%.

The percentages of the DNAs derived from the recipients with respect to those from their donors in peripheral white blood cells after HSCT.

The auditory pathway in the brainstem was Gd-enhanced 9.5 months before HSCT, but Gd enhancement was not obvious 0.8 months before HSCT.

Gd-enhanced lesions on brain MRI became obscure 3.5 months after HSCT and undetected 19 months after HSCT.

Gd-enhanced lesions on brain MRI became obscure but did not completely disappear, presumably because the follow-up period of brain MRI was short (around 1–2 months) after HSCT.

Neurological findings attributable to the cerebral/cerebellar/brainstem lesions became stable or partially improved in all the patients after HSCT (Table 3). In Patients 4, 5, 7, 9, 11 and 12, slight progression of lower limb weakness, ataxia, sensory disturbance, decreased gait speed or bladder disturbance was observed in 1–9 months after HSCT but became stable thereafter. Improvement of dysarthria or dysphagia was observed in Patients 1, 4, 5 and 10. Patient 10 could not turn in bed without using his hands and had communication difficulties due to weak voice before HSCT but became able to sit on a wheelchair and communicate with a normal voice volume. Patient 1 showed gradual progression of bilateral lower limb weakness accompanied by disuse muscle atrophy presumably attributable to AMN symptoms but he did not develop any new symptoms attributable to brain lesions. Patients 2, 3 and 7 returned to their previous working places, Patient 4 started to work at another place and Patient 5 returned to his university and recently graduated from the university. Patient 6 started to work at home. Patients 1 and 8 stayed at home. Patients 9–12 have undergone HSCT recently and await careful follow-up.

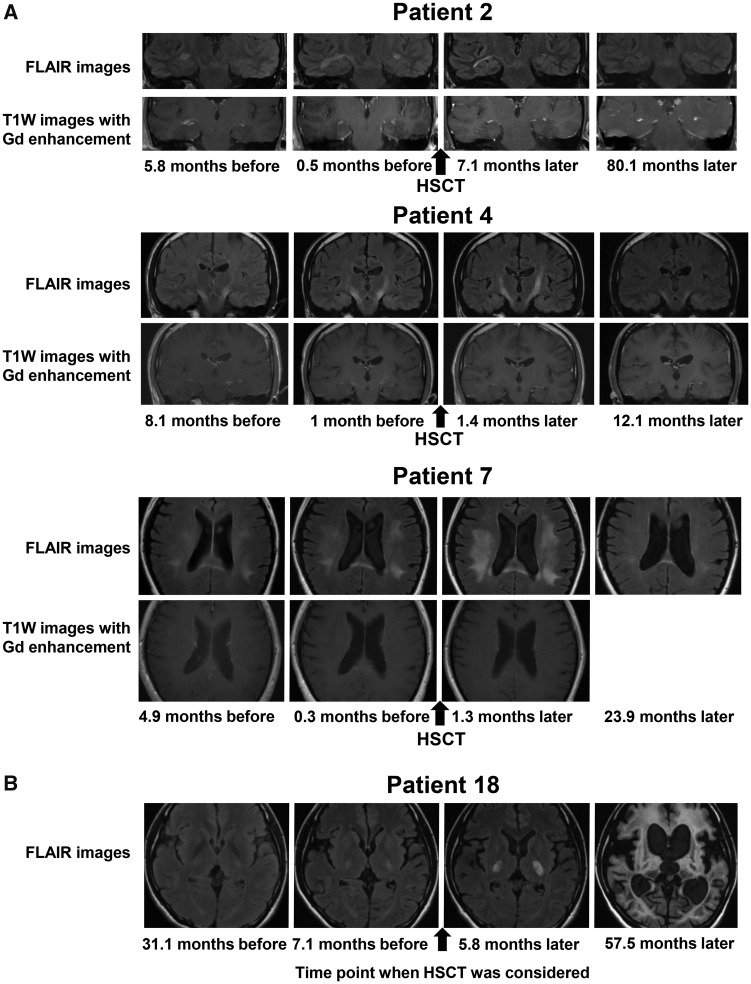

MRI findings after allogenic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Gd-enhanced brain MRI lesions rapidly disappeared within 2 months after HSCT in all the patients except in Patients 2, 10 and 12. As shown in Fig. 3, reduction of contrast enhancement in the right temporal lobe white matter (Patient 2), in the pyramidal tract (Patient 4) and in the splenium of the corpus callosum (Patient 7) is obvious. The Gd-enhanced lesion in Patient 2 became obscure at 3.5 months and was no longer detected 19 months after HSCT. The Gd-enhanced lesions in Patients 10 and 12 became obscure 1.4 and 1.6 months after HSCT, respectively.

Figure 3.

Changes in brain MRI findings. (A) Representative coronal or axial images obtained by FLAIR imaging (upper panels) and T1W imaging with Gd enhancement (lower panels) on brain MRI before and after HSCT in Patients 2, 4 and 7. In Patient 2, the white matter lesions enlarged and were Gd-enhanced before HSCT. The white matter lesions became small (upper panels) and the Gd-enhanced lesions became gradually obscure (lower panels) after HSCT. In Patient 4, the white matter lesions in the pyramidal tracts enlarged until 1.4 months after HSCT but subsequently became small (upper panels). The white matter lesions in the pyramidal tracts were Gd-enhanced before HSCT but disappeared after HSCT (lower panels). In Patient 7, the white matter lesions in the frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital lobes enlarged until 1.3 months after HSCT, but the white matter lesions subsequently became small (upper panels). The white matter lesion in the splenium of the corpus callosum was Gd-enhanced before HSCT but disappeared after HSCT (lower panels). (B) Axial FLAIR images of Patient 18 who declined to undergo HSCT. When we considered HSCT for the patient, brain MRI showed limited white matter lesions in the pyramidal tracts and mild white matter lesions in the optic radiations, the brachia of the inferior colliculus and the cerebellum (Loes score, 3.5). These white matter lesions showed progressive enlargement, and brain MRI taken 57.5 months later showed massive cerebral, cerebellar and brainstem white matter lesions accompanied with marked atrophy (Loes score, 34). FLAIR = fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; T1W = T1 weighted.

The white matter lesions stopped enlarging within 2 months in nine patients (Patients 1–3, 6, 8 and 9–12) and within 12 months in the remaining three patients (Patients 4, 5 and 7) after HSCT. No new white matter lesions have appeared in any of them to date. Of note, reduction in size of the white matter lesions was observed in seven patients (Patients 1–4, 7 and 9–10) (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3 and Table 3). The median Loes scores before HSCT and at the last follow-up visit after HSCT were 6.0 and 5.25, respectively. The Loes score increased by one point in Patients 1, 4 and 5 with atrophic changes of the brainstem, but otherwise stabilized or even improved (Table 3). Representative MRI findings of Patients 2, 4 and 7 showing reduction in the size of the white matter lesions are shown in Fig. 3A. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 3, in Patient 1, reduction in the size of the lesion of the splenium of the corpus callosum is obvious. There was also a prominent regression of the white matter lesions in the auditory pathways even taking the mild atrophic change of the brainstem into consideration. In Patient 4, there was a regression of white matter lesions in the pyramidal tracts including the internal capsule and the brainstem, and in the cerebellum even allowing the mild atrophic changes of the brainstem and cerebellum. In Patient 5, white matter lesions in the brainstem and cerebellum stabilized and the atrophic changes in the brainstem and cerebellum progressed. In Patients 2, 3 and 6–12, there were no obvious atrophic changes of brain. In patients who did not undergo HSCT, the white matter lesions continued to enlarge accompanied by marked atrophic changes in the brain (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. 4).

Complications associated with allogenic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation

No grade IV infections or other serious complications including neurological problems (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 3.0) were observed in all the patients after HSCT (Table 2). Cryptogenic organizing pneumonitis appeared in Patient 2, transplantation-associated thrombotic microangiopathy appeared in Patient 6 with declining renal functions 5 months after HSCT, which became stable in the follow-up study, and Patient 7 was suspected of having tacrolimus-induced nephrotoxicity with declining renal function 2 months after HSCT.

No acute GVHD symptoms appeared in Patients 3, 5, 7–10 and 12. Only grade I cutaneous symptoms of acute GVHD appeared in Patients 2, 4, 6 and 11 and treated with topical or oral steroid (Przepiorka et al., 1995). Stage 2 gastrointestinal and stage 3 skin acute GVHD appeared in Patient 1 and managed with methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg). Chronic GVHD appeared in two patients, including bronchiolitis obliterans in one patient.

Changes in very-long-chain saturated fatty acid levels after allogenic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation of patients with adrenoleukodystrophy

The average ratios of C26:0/C22:0 before and after HSCT, excluding the data of Patients 4 and 6 taking Lorenzo’s oil before HSCT, were 0.024 and 0.022 (normal range 0.003–0.006), respectively (Table 3). Considering the possibility that plasma sphingomyelin VLCFAs may not have exclusively derived from bone marrow-derived cells, we further measured VLCFA levels in red blood cells. In Patient 2, the ratio of C26:0/C22:0 in the red blood cell membrane sphingomyelin 25.1 months after HSCT was 0.190, which was between the average levels in patients [0.26 + 0.04, mean + SD (n = 8)] and those in controls [0.10 + 0.02 (n = 16)] in the previous report (Tsuji et al., 1981). These results suggest that VLCFAs may not be exclusively derived from bone marrow-derived cells.

Chimerism analysis after allogenic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Chimerism analysis showed that all the patients kept full-donor chimerism after HSCT to date (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

We showed that HSCT was safely conducted and effective in arresting the progression of brain MRI lesions. As shown in Fig. 2, the survival probability was significantly higher in the patients who underwent HSCT than in those who did not (P = 0.0089). The arrest of enlargement of brain MRI lesions was confirmed in all the 12 patients. Of note, seven patients showed reduction in size of the white matter lesions (Table 3), suggesting that HSCT not only stabilizes the enlargement of brain lesions but may also improve the brain lesions in patients in early stages. Moreover, neurological findings attributable to cerebral/cerebellar/brainstem lesions became stable or partially improved in all the 12 patients. Compared with the clinical outcomes in previous studies (Hitomi et al., 2005; Fitzpatrick et al., 2008; Saute et al., 2016; Kühl et al., 2017; Waldhüter et al., 2019), the results described in the present report demonstrated outstanding clinical outcomes including arrest of disease progression of the clinical presentations and stabilization of the MRI findings as well as the safety associated with HSCT. The clinical courses of patients with ALD after HSCT were also better than those described in a natural history study (Suzuki et al., 2005).

In previous reports on HSCT for ACALD, variable clinical outcomes have been described (Hitomi et al., 2005; Fitzpatrick et al., 2008; Saute et al., 2016; Kühl et al., 2017; Waldhüter et al., 2019). Recently, a multicenter-based retrospective study of the long-term outcomes of HSCT in 14 patients with ACALD has been reported (Kühl et al., 2017). Stabilization of cerebral lesions within 1 year after HSCT was observed in five patients, supporting the efficacy of HSCT (Hitomi et al., 2005; Fitzpatrick et al., 2008; Saute et al., 2016; Kühl et al., 2017). Of the 17 patients, however, three patients showed the progressive enlargement of cerebral lesions or appearance of new lesions >1 year after HSCT and eight patients died because of HSCT-related complications or disease progression (Hitomi et al., 2005; Fitzpatrick et al., 2008; Saute et al., 2016; Kühl et al., 2017). Of the additional seven patients with ACALD recently reported in addition to the eight patients in the previous multicenter-based retrospective study, two patients died because of HSCT-related complications or disease progression (Waldhüter et al., 2019). The source of stem cells was either cord blood or peripheral blood for 4 of the 10 patients who died (Fitzpatrick et al., 2008; Saute et al., 2016; Kühl et al., 2017; Waldhüter et al., 2019), whereas the source of the stem cells in the present study was the bone marrow for all the patients. In CCALD, cord blood is often selected as the source of stem cells owing to not only the unavailability of the bone marrow from allele-matched related donors but also the relatively short coordination period for cord blood transplantation (Martin et al., 2006). Limitation in the number of stem cells obtained from cord blood might underlie the different survival rates among patients with ACALD. In the abovementioned previous studies (Kühl et al., 2017; Waldhüter et al., 2019), myeloablative regimens were used in 19 of the 21 patients. In our study, we safely conducted nonmyeloablative regimens in all the patients with full-donor chimerism and without any fatal complications (Table 2). Nonmyeloablative regimens seem to be favourable because of their reduced toxicity to the central nervous system and mucosal membrane. Life-threatening or fatal infections occurred in five of the six patients who died in the previous study, whereas no such infections occurred in the present study. A good condition in activities of daily living, a prerequisite for HSCT in the present study, may have contributed to the prevention of serious infections. Relatively low incidence of acute and chronic GVHD in our study also may contribute to the good outcome. Nonmyeloablative regimens and use of antithymocyte globulin might have contributed to the low frequency of GVHD (Kröger et al., 2016).

The present study demonstrates that HSCT was conducted safely and arrested the inflammatory demyelination in patients with AdolCALD/ACALD and cerebello-brainstem form of ALD similarly to the clinical outcomes that have been accumulated with HSCT for CCALD (Shapiro et al., 2000; Peters et al., 2004). In particular, early diagnosis of cerebral form and cerebello-brainstem form of ALD based on the careful prospective observation of the patients seems to be essential for better outcomes with HSCT. The brain MRI lesions were first detected in Patient 7 when he still did not show any neurological symptoms attributable to the lesions. It is helpful to provide detailed clinical information including that on HSCT to patients, male individuals at risk and families to facilitate the early detection of brain lesions. Indeed, 5 of the 12 patients with ALD who underwent HSCT in this study had a family history of ALD, which contributed to early diagnosis. Thus, patient selection at early stages in a setting of a single-institution-based prospective study substantially contributed to the excellent clinical outcomes in the present study. We consider that patients with adult-onset cerebral form of ALD fulfilling the following conditions would be ideal to achieve a good outcome of HSCT: (i) MRI findings with Loes scores ≤13 and with an early stage of white matter lesions in brain MRI and (ii) good conditions in activities of daily living and cooperativity along with preserved or only mildly decreased cognitive functions (Mini–Mental State Examination ≥25). These conditions are consistent with those that have been recommended for CCALD (Peters et al., 2004).

Although unrelated donors were found for all the patients, it took 3–8 months from the time of registration with the Japan Marrow Donor Program to HSCT (Table 2). During this period, white matter lesions enlarged in seven patients (Patients 1, 2, 4, 5, 9, 10 and 12) and neurological symptoms deteriorated in five patients before HSCT (Patients 4, 5, 9, 10 and 12). Since it is of vital importance to conduct HSCT as early as possible, every effort should be made to accelerate coordination with unrelated donors.

Despite the arrest of inflammatory demyelination in the brain white matter, including reduction in the size of lesions of auditory pathways, Patient 1 showed gradual progression of bilateral lower limb weakness. We need to further follow-up the patient to address the long-term outcomes of HSCT with regard to AMN symptoms, because in some patients with CCALD who underwent HSCT, AMN symptoms reportedly developed later in life (van Geel et al., 2015).

The efficacy of the gene therapy for CCALD has recently been reported (Eichler et al., 2017). In that report, 17 patients with CCALD received infusion of autologous CD34+ cells transduced with a lentiviral vector containing normal ABCD1 complementary DNA. Fifteen of the 17 patients survived with no major functional disability, demonstrating the clinical efficacy of the gene therapy. One patient, however, died due to disease progression. Most of the patients showed deterioration of their Loes scores on MRI, and the reemergence of enhancement was observed in four patients 18–24 months after the therapy. Thus, clinical efficacy may be limited in part. Since the ages of the patients are different, direct comparison of the clinical efficacy between gene therapy and HSCT is difficult. However, we consider that the following point deserves attention. All of our patients showed full-donor chimerism after HSCT throughout the observation period, while the median percentage of CD14+ cells expressing the ALD protein was 19% 24 months after the therapy. Thus, the proportion of cells expressing the normal ALD protein might be useful in evaluating the clinical efficacy in these therapies. The clinical efficacies of HSCT and gene therapy for cerebral ALD should be further investigated.

In conclusion, this single-institution-based prospective study demonstrated that HSCT is safe and efficacious for arresting the disease progression of AdolCALD/ACALD and cerebello-brainstem form of ALD. The source of stem cells, preparative regimens, early detection of brain lesions based on prospective follow-up and a good condition in activities of daily living play key roles in achieving better outcomes of HSCT.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms. Mio Takeyama, Ms. Keiko Hirayama and Ms. Zhenghong Wu for their support in the laboratory experiments, Dr. Mitsuto Sato for providing clinical information on the patient and prof. Hiromasa Yabe for his critical reading and suggestion.

Funding

This study was supported in part by KAKENHI (Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas Nos. 22129001 and 22129002) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, Grants-in-Aid [H23-Jitsuyoka (Nanbyo)-Ippan-004 and H26-Jitsuyoka (Nanbyo)-Ippan-080] from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan, and grants (nos. 15ek0109065h0002, 16kk0205001h001, 17kk0205001h0002 and 17ek0109279h0001) from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED).

Competing interests

K.K. has patent-pending genetic test for T-cell lymphoma and PD-L1 alterations. M.I. reports personal fees from Novartis, Janssen, Takeda Pharmaceutical and Nippon Shinyaku outside the submitted work. O.A. reports grants and personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited, Eisai Co., Ltd., Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd., FUJIFILM Toyama Chemical Co., Ltd., and Guerbet Japan and grants from Nihon Medi-Physics Co., Ltd., outside the submitted work. M.K. reports grants and personal fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Astellas Pharma, grants from Novartis Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer Seiyaku K.K. and personal fees from Shionogi & Co., Ltd., outside the submitted work. The remaining authors report no disclosures.

Glossary

- ACALD

adult-onset cerebral form of adrenoleukodystrophy

- AdolCALD

adolescent-onset cerebral form of adrenoleukodystrophy

- ALD

adrenoleukodystrophy

- AMN

adrenomyeloneuropathy

- CCALD

childhood-onset cerebral form of adrenoleukodystrophy

- Gd

= gadolinium

- GVHD

graft-versus-host disease

- HSCT

allogenic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- VLCFAs

very-long-chain saturated fatty acids

References

- Aubourg P, Blanche S, Jambaqué I, Rocchiccioli F, Kalifa G, Naud-Saudreau C, et al. Reversal of early neurologic and neuroradiologic manifestations of X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy by bone marrow transplantation. N Engl J Med 1990; 322: 1860–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler F, Duncan C, Musolino PL, Orchard PJ, De Oliveira S, Thrasher AJ, et al. Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Gene Therapy for Cerebral Adrenoleukodystrophy. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 1630–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick AS, Loughrey CM, Johnston P, McKee S, Spence W, Flynn P, et al. Haematopoietic stem-cell transplant for adult cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy. Eur J Neurol 2008; 15: e21–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitomi T, Mezaki T, Tomimoto H, Ikeda A, Shimohama S, Okazaki T, et al. Long-term effect of bone marrow transplantation in adult-onset adrenoleukodystrophy. Eur J Neurol 2005; 12: 807–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi M, Schaumburg HH, Powers J, Kishimoto Y, Koilodny E, Suzuki K, et al. Fatty acid abnormality in adrenoleukodystrophy. J Neurochem 1976; 26: 851–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013; 48: 452–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kröger N, Solano C, Wolschke C, Bandini G, Patriarca F, Pini M, et al. Antilymphocyte globulin for prevention of chronic graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühl J-S, Suarez F, Gillett GT, Hemmati PG, Snowden JA, Stadler M, et al. Long-term outcomes of allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for adult cerebral X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Brain 2017; 140: 953–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983; 33: 1444–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loes DJ, Hite S, Moser H, Stillman AE, Shapiro E, Lockman L, et al. Adrenoleukodystrophy: a scoring method for brain MR observations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1994; 15: 1761–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney FI, Barthel DW.. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J 1965; 14: 61–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin PL, Carter SL, Kernan NA, Sahdev I, Wall D, Pietryga D, et al. Results of the cord blood transplantation study (COBLT): outcomes of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood transplantation in pediatric patients with lysosomal and peroxisomal storage diseases. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2006; 12: 184–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsukawa T, Asheuer M, Takahashi Y, Goto J, Suzuki Y, Shimozawa N, et al. Identification of novel SNPs of ABCD1, ABCD2, ABCD3, and ABCD4 genes in patients with X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD) based on comprehensive resequencing and association studies with ALD phenotypes. Neurogenetics 2011; 12: 41–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser HW, Mahmood A, Raymond GV.. X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Nat Rev Neurol 2007; 3: 140–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser HW, Moser AB, Frayer KK, Chen W, Schulman JD, O'Neill BP, et al. Adrenoleukodystrophy: increased plasma content of saturated very long chain fatty acids. Neurology 1981; 31: 1241–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosser J, Douar A-M, Sarde C-O, Kioschis P, Feil R, Moser H, et al. Putative X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy gene shares unexpected homology with ABC transporters. Nature 1993; 361: 726–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno T, Tsuchida H, Fukuhara N, Yuasa T, Harayama H, Tsuji S, et al. Adrenoleukodystrophy: a clinical variant presenting as olivopontocerebellar atrophy. J Neurol 1984; 231: 167–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters C, Charnas LR, Tan Y, Ziegler RS, Shapiro EG, DeFor T, et al. Cerebral X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy: the international hematopoietic cell transplantation experience from 1982 to 1999. Blood 2004; 104: 881–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, Klingemann HG, Beatty P, Hows J, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant 1995; 15: 825–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saute JAM, Souza C. F M D, Poswar F. D O, Donis KC, Campos LG, Deyl AVS, et al. Neurological outcomes after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for cerebral X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy, late onset metachromatic leukodystrophy and Hurler syndrome. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2016; 74: 953–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro E, Krivit W, Lockman L, Jambaqué I, Peters C, Cowan M, et al. Long-term effect of bone-marrow transplantation for childhood-onset cerebral X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Lancet 2000; 356: 713–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Takemoto Y, Shimozawa N, Imanaka T, Kato S, Furuya H, et al. Natural history of X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy in Japan. Brain Dev 2005; 27: 353–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano H, Koike R, Onodera O, Sasaki R, Tsuji S.. Mutational analysis and genotype-phenotype correlation of 29 unrelated Japanese patients with X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Arch Neurol 1999; 56: 295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji S, Suzuki M, Ariga T, Sekine M, Kuriyama M, Miyatake T, et al. Abnormality of long-chain fatty acids in erythrocyte membrane sphingomyelin from patients with adrenoleukodystrophy. J Neurochem 1981; 36: 1046–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Geel BM, Poll-The BT, Verrips A, Boelens J-J, Kemp S, Engelen M, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation does not prevent myelopathy in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy: a retrospective study. J Inherit Metab Dis 2015; 38: 359–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldhüter N, Köhler W, Hemmati PG, Jehn C, Peceny R, Vuong GL, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with myeloablative conditioning for adult cerebral X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. J Inherit Metab Dis 2019; 42: 313–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting these findings are available upon request.