Abstract

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) have immune regulatory and tissue regenerative properties. MSCs are being studied as a therapy option for many inflammatory and immune disorders and are approved to treat acute graft-versus-host disease (GvHD). The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic and associated coronavirus infectious disease-19 (COVID-19) has claimed many lives. Innovative therapies are needed. Preliminary data using MSCs in the setting of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in COVID-19 are emerging. We review mechanisms of action of MSCs in inflammatory and immune conditions and discuss a potential role in persons with COVID-19.

Keywords: Mesenchymal stromal cell, SARS-CoV2, COVID-19

1. Introduction

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are a promising therapy of inflammatory and immune disorders because of their immune modulatory properties [1,2]. MSCs, by interacting with the innate immune system, sense inflammatory signals and exert anti- and pro-inflammatory roles making them an option to treat auto- and allo-immune processes [3,4]. MSCs are used to treat some diseases with promising results [[5], [6], [7]]. There are recent reports of therapy of COVID-19-related severe acute respiratory syndrome (ARDS) with MSCs [8,9]. ARDS is the leading cause of death in COVID-19. It is characterized by acute onset with bilateral lung infiltrates, no evidence of elevated left atrial pressure and arterial oxygen tension to inspired oxygen fraction (PaO2/FiO2) < 200 mmHg [10]. The cytokine storm caused by the viral infection probably precipitates COVID-19-associated ARDS. Avoiding this storm using the anti-inflammatory properties of MSCs may be effective [9,11,12]. We review data on anti-inflammatory activity of MSCs and discuss mouse and human studies in COVID-19.

2. Mechanism of action of MSCs in inflammatory conditions

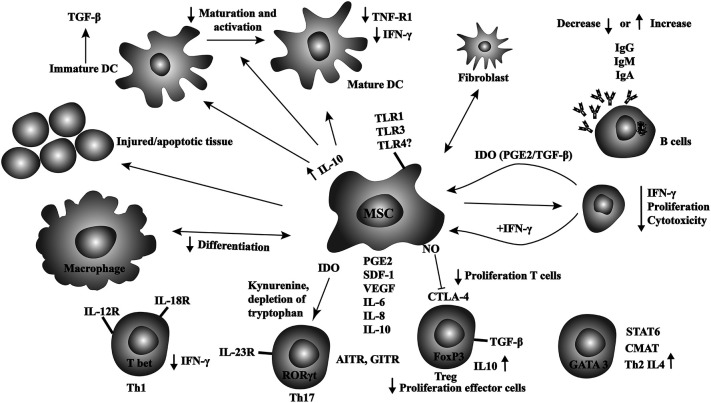

Accurate identification of MSCs is challenging and imprecise [13,14]. Homing of MSCs to different tissues or organs may lead to different effects [15]. Cell source, surface markers and cytokine profile in the cell culture can influence the behavior and activity of MSCs [[15], [16], [17], [18]]. Also, the cell and molecular mechanisms how MSCs interact and modulate other immune cells are complex and incompletely understood [15]. These prevent accurate understanding of their mechanism of action. MSCs express several adhesion molecules, endopeptidases and growth factors which facilitate migration to different tissues. They modulate several immune cells including regulatory T-cells (T-regs), conventional T-cells (T-cons), B-cells, natural killer (NK)-cells, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells via direct interactions and via secretion of diverse cytokines [15,19]. Fig. 1 shows interactions between MSCs and immune cells. MSCs promote anti-inflammatory response by promoting monocytes and macrophages polarization toward a type II phenotype and by inhibiting differentiation toward a type I phenotype [20,21]. MSCs-produced interleukin-6 (IL-6) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) stimulate monocytes to secrete interleukin-10 (IL-10) at high concentrations. These effects reduce IL-12p70, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a), interleukin-17 (IL-17), high levels of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II antigens, CD45R and CD11b which suppress T-cells. This action of MSCs is independent of FoxP3+ Tregs and inhibits differentiation of dendritic cells (DCs) to a type I phenotype [15,[22], [23], [24]]. Also, Tregs are stimulated by MSCs and achieve immune homeostasis by suppressing auto-immunity [25,26]. In preclinical models, treatment of MSCs with interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) enhances their anti-inflammatory effects. Incubation with muramyl dipeptide (MDP) increases their ability to suppress mononuclear cell proliferation and reduce inflammation [27,28]. Additionally, MSCs produce LL37 (a 37 amino acid cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide), a potent anti-microbial that kills bacteria and viruses [18]. As such MSCs inhibit dendritic cells maturation, suppress T- and NK-cells and promote regulatory T-cells resulting in anti-inflammatory effects in diverse models of acute inflammation in different tissues and organs [[29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36]].

Fig. 1.

Schematic overview of the complex interactions between MSCs and immune.

Toll-like Receptors (TLR) are the main sensors of viral presence and involved in many immune responses during infection. Inflammation caused by direct viral injury results in TLR-priming (TLR-agonist engagement) which can affect MSC phenotype, multi-lineage potential and their immune-modulatory capacity. TLR activation in response to viral infection modulates expression of HLA-antigens and other co-stimulatory molecules resulting in impaired function of some immune cells. Because MSC exposed to TLR ligands up-regulate expression of HLA—I, HLA-II and costimulatory molecules (CD40, CD80, CD86) it is important to consider this when giving allogeneic MSCs [37,38].. Additionally, pre-stimulation of MSCs with specific TLR-ligands could be a priming step to modulate their function to achieve a desired effect in specific viral infections such as with SARS-CoV-2.

Exosomes, apoptotic bodies and micro-vesicles, are formed by budding from the endosomes and other membranes of MSCs and released into the extra-cellular space [39,40]. Considerable data indicate MSC-exosomes contain molecules (tetraspanins, heat shock protein, phosphatidylserine, annexins, MHC class I and II, etc.) released in response to diverse stimuli. These molecules interact with target cells resulting in similar therapeutic benefits as intact cells [15,[41], [42], [43], [44]].

3. MSCs in human disease

Immune modulatory effects of MSCs offer an attractive potential therapy for several reasons including safety, availability, ex vivo expandability, and ease of in vitro modification to produce diverse effects. However, there are many unanswered questions such as best tissue source of MSCs (bone marrow, fat, placenta, dental pulp, etc.), best dose, route, frequency, recipient age-dependency groups, interaction with other therapies and the long term effects [[45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51]].

There are few data of safety and efficacy of MSCs in humans [52]. In a transplant study investigator infused culture-expanded MSCs with HLA-identical sibling-matched hematopoietic stem cells in 46 subjects with hematologic cancers. There were no adverse effects [53]. A phase-3 trial comparing MSCs or placebo in subjects with corticosteroid refractory acute GvHD showed no benefit [54,55]. A single arm trial of ex vivo expanded MSCs for corticosteroid refractory acute GvHD in children had a 70% overall response rate compared with a pre-specified target of 45% [56]. These trials were neither blinded nor placebo-controlled. A meta-analysis suggested safety and efficacy of MSCs in acute GvHD [57]. Based on these data MSCs were approved to treat gastro-intestinal GvHD in children in Canada and New Zealand but not in the US or EU [58]. Studies using MSCs for ARDS report safety but little efficacy [59,60]. A meta-analysis suggested efficacy of MSCs in inflammatory bowel disease [61]. A search of ClinicalTrials.gov identified 282 studies of MSCs in diverse settings. Table 1 summarizes these data.

Table 1.

Completed and recruiting studies of MSCs for diverse diseases.

4. MSCs for inflammatory lung injury in mice

Precisely how SARS-CoV-2-infection causes COVID-19 including ARDS is unknown, some data indicate high plasma concentrations of inducible protein-10 (IP10), monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), macrophage Inflammatory protein 1A (MIP1A), IL-6, granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF α). These molecules may be responsible for an exaggerated systemic immune inflammatory state with resultant ARDS [11]. MSCs are a potential intervention in this setting. In animal models of viral infections many chemokines cause an exaggerated inflammatory response and lung injury. In some but not all studies lung injury was reduced by giving MSCs [44,62]. Additionally, MSCs are effective in several mouse models such as endotoxin- and bleomycin-induced lung injury [[63], [64], [65]]. MSCs were ineffective in a mouse model of H1N1 influenza-induced lung injury [66] but effective in a model of a more virulent strain of influenza H5N1 [67]. Another preclinical study used intravenous MSCs combined with oseltamivir to prevent or treat mice inoculated with the 2009 pandemic H1N1. This strategy was ineffective [68].

5. MSCs in COVID-19-related ARDS

Because ARDS in persons with COVID-19 is thought to result from cytokine release syndrome (CRS) studies of interventions to moderate this response seem reasonable. Corticosteroids were used in several uncontrolled studies but a recent meta-analysis reported them ineffective with prolonged virus clearing and other adverse events in severe coronavirus infections [69]. MSCs in the lung release anti-inflammatory mediators responsible for ameliorating respiratory viral-induced lung injuries [70,71]. In an uncontrolled study investigators gave MSCs to 7 subjects with COVID-19-related pneumonia and results compared with 3 non-randomized, non-concurrent controls [9]. MSCs recipients had decreased plasma concentrations of C-reactive protein (CRP), TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor), and increased IL-10. Blood lymphocyte concentrations increased and cytokine-secreting cells including CXCR3 + CD4+ T-cells, CXCR3 + CD8+ T-cells, and CXCR3+ NK-cells decreased. CD14 + CD11c + CD11bmid regulatory DCs also increased. There were no adverse events. Because MSCs have no ACE2 or TMPRSS2 receptors they are likely protected from infection by SARS-CoV-2. However, there are some methodological issues with this study and the above observations require confirmation. In another uncontrolled phase-2 study, 7 subjects with COVID-19-related ARDS received allogeneic placenta-derived MSCs. Four improved but there were no controls and investigators were not blinded (https://www.hospimedica.com/covid-19/articles/294781654/pluristem-reports-preliminary-data-from-its-covid-19-compassionate-use-program.html). Recently, Mesoblast Ltd. announced its allogeneic MSC therapy showed an 83% survival rate in ventilator-dependent COVID-19 patients with moderate to severe ARDS. (https://www.bioworld.com/articles/434640-mesoblast-reports-83-survival-in-ventilator-dependent-covid-19-patients-following-stem-cell-therapy). Nine of 12 subjects were weaned off the ventilator support within 10 days following two infusions of MSCs. A recent meta-analysis of cell based therapies for COVID-19 identified 200 subjects receiving allogeneic MSCs intra-tracheally or intravenously [72]. There were no adverse events and authors reported a non-statistically-significant improvement in mortality, pulmonary function, oxygenation and inflammatory markers. Exosomes derived from allogeneic bone marrow-derived MSCs were given to 24 subjects with severe COVID-19 in an uncontrolled study [73]. There were no adverse events. The authors reported improvement in oxygenation and acute phase reactants. Four subjects died, 3 remained critically ill and 17 recovered. Without controls it is impossible to critically analyze these data. These studies are uncontrolled and critical interpretation of these data is impossible.

Many questions regarding the use of MSCs in COVID-19 remain unanswered including best source, dose, route of administration etc. Because MSCs take 3–4 weeks to expand, the use of autologous MSCs in COVID-19 related ARDS is impractical. Data using MSCs in persons with COVID-19-related ARDS are encouraging but not convincing. Studies were small, none were randomized, there were no placebo-treated controls and investigators were not blinded. Based on these data we conclude it is reasonable to study MSCs in COVID-19-related ARDS but only in the context of appropriately designed and controlled clinical trial with blinded investigators. Because single arm trials report few adverse events we suggest the next step should be evaluating MSCs in randomized phase trials with appropriate endpoints.

6. MSCs safety profile

Giving MSCs to humans seems safe [8,9,54,56,61,72]. A meta-analysis with data of >1000 subjects reported only transient fever [74]. Reports of using MSCs for diverse setting including heart failure, kidney transplant and multiple sclerosis report few adverse events [[75], [76], [77], [78]]. MSCs products are diverse with multiple potential sources, production methods and delivery routes complicating critical analyses of safety. Serious adverse events including thrombosis, embolization and death are reported with some products in animals and humans but at a low frequency [[79], [80], [81], [82], [83]].

7. Conclusion and future directions

MSCs are an attractive potential therapy of diverse diseases including ARDS in persons with COVID-19. Several trials of MSCs are ongoing. Preliminary studies report favorable effects but have severe methodological limitations precluding critical analyses (Table 2 ). There are several unanswered questions: (1) the best donor; (2) source; (3) dose, route and frequency; (4) fresh or cryopreserved; (5) expanded or not; (6) when to begin therapy and others. These questions can only be answered in controlled trials. Table 3 summarizes our opinions regarding potential solutions to current methodological limitations and heterogeneity in MSCs trials. Although phase-3 studies may be impractical in the setting of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, randomized phase-2 studies with a placebo control and blinded investigators are possible. We hope societies such as the International Society of Cell Therapy (ISCT) and International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) update guidelines and recommendations to improve the quality and conduct of trials of MSCs in COVID-19.

Table 2.

Active trials of MSCs in the setting of COVID-19 infection.

| NCT number | Title | Phase | Condition | Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04313322 | Treatment of COVID-19 Patients Using Wharton Jelly- Mesenchymal Stem Cells | I | Use of Stem Cells for COVID-19 Treatment | Wharton Jelly MSCs |

| NCT04288102 | Treatment With Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Severe Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) | II | Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) | MSCs |

| NCT04252118 | Mesenchymal Stem Cell Treatment for Pneumonia Patients Infected With 2019 Novel Coronavirus | I | 2019 Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia | MSCs |

| NCT04339660 | Clinical Research of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Treatment of COVID-19 Pneumonia |

I/II | COVID-19 | MSCs |

| NCT04273646 | Study of Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Treatment of Novel Coronavirus Severe Pneumonia | NA | 2019 Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia | MSCs |

| NCT04293692 | Therapy for Pneumonia Patients infected by 2019 Novel Coronavirus | NA | COVID-19 | MSCs |

| NCT04269525 | Umbilical Cord(UC)- Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) Treatment for the 2019-novel Coronavirus (nCOV) Pneumonia | II | Pneumonia, Viral Pneumonia, Ventilator- Associated |

MSCs |

| NCT04333368 | Cell Therapy Using Umbilical Cord-derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in SARS-CoV-2- related ARDS | I/II | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 | Umbilical cord Wharton's jelly- derived human MSCs |

| NCT04276987 | A Pilot Clinical Study on Inhalation of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Exosomes Treating Severe Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia | I | Coronavirus | MSCs- derived exosomes |

Table 3.

Authors' opinions regarding potential solutions to overcome current methodological limitations and heterogeneity in MSCs trials.

| Current stance | Potential solutions |

|---|---|

| No prospective studies available evaluating autologous versus allogeneic source of MSC for infections | Allogeneic source can be utilized under clinical trial. Given the public health crises, an allogeneic source may be logistically easier and quicker |

| No randomized data available to differentiate between the various tissue sources for MSCs | A clinical trial may utilize any of the tissue sources for generation of MSCs. At least 3 culture passages should be undertaken the MSCs should fulfill at least the definition proposed by the ISCT [62] |

| No randomized data available evaluating the optimal route of delivery in human trials. Earlier data suggesting “lung trapping” of MSCs when given via intravenous route, however, other studies did not report a difference in outcomes (historic controls) based on the route of delivery |

Intravenous systematic delivery of the MSCs has been the most common route evaluated in clinical trials, and is an acceptable and logistically feasible way to try MSC intervention for a COVID-19 infection complication, even when the target organ is the lung |

| No concrete data that the expanded MSC pool can improve clinical hard end points | Clinical trials can be conducted for COVID-19 complication treatment with or without culture expansion of MSCs |

| Various end-points have been used in different clinical trials which have utilized MSCs for different diseases. E.g. for GVHD, response rates have been the most common end-point reported in the clinical trials. | Given COVID-19 is a highly fatal disease, the primary outcome variable should focus on mortality. Proposed primary end-point for MSC trials in COVID-19 ARDS: All-cause hospital mortality Or A scale which encompasses mortality e.g. 7-point ordinal scale for COVID-19 severity |

8. Practice points

-

•

After licensing MSCs express HLA class I and can express HLA class II molecules. However, MSCs may have low immunogenicity.

-

•

Allogeneic MSC source can be utilized for ARDS in COVID-19 infection. The allogeneic source provides an off the shelf quick option for these acutely ill patients in need for a quick intervention.

-

•

MSC characterization should fulfill at least the definition proposed by the ISCT.

-

•

Intravenous systematic delivery of the MSCs has been the most common route evaluated in clinical trials.

-

•

Earlier data suggest lung trapping of MSCs, this may be advantageous for COVID-19 infection, however the optimal route of administration still has not been determined.

-

•

Clinical trials can be conducted for COVID-19 complication treatment with or without culture expansion of MSCs.

-

•

Given COVID-19 is a highly fatal disease therefore the primary outcome variable should focus on mortality. Proposed primary end-point for MSC trials in COVID-19 trials may include: All-cause hospital mortality or a scale which encompasses mortality e.g. 7-point ordinal scale for COVID-19 severity.

9. Research agenda

-

•

Optimum donor source of MSCs i.e. allogeneic versus autologous should be determined.

-

•

Best tissue source for MSCs: adipose tissue, dental pulp, umbilical cord, bone marrow, etc. should be evaluated.

-

•

Best route to administer MSCs: systemic or proximal should be studied.

-

•

The role of expanded versus unmanipulated MSCs has to be explored.

-

•

The optimal end point of the clinical trials of MSC usage for COVID-19 treatments must be determined.

-

•

Microvesicles and exosomes efficacy and safety should be explored, as these can bypass a number of logistic issues with MSCs.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

cells.

References

- 1.Bernardo M.E., Fibbe W.E. Mesenchymal stromal cells: sensors and switchers of inflammation. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13(4):392–402. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keto J., Kaartinen T., Salmenniemi U., Castren J., Partanen J., Hanninen A., et al. Immunomonitoring of MSC-treated GvHD patients reveals only moderate potential for response prediction but indicates treatment safety. Mol Ther-Meth Clin D. 2018;9:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keating A. Mesenchymal stromal cells: new directions. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10(6):709–716. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le Blanc K., Mougiakakos D. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells and the innate immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(5):383–396. doi: 10.1038/nri3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walter J., Ware L.B., Matthay M.A. Mesenchymal stem cells: mechanisms of potential therapeutic benefit in ARDS and sepsis. Lancet Resp. Med. 2014;2(12):1016–1026. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parekkadan B., Milwid J.M. Mesenchymal stem cells as therapeutics. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2010;12:87–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-070909-105309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson J.G., Liu K.D., Zhuo H., Caballero L., McMillan M., Fang X., et al. Mesenchymal stem (stromal) cells for treatment of ARDS: a phase 1 clinical trial. Lancet Resp. Med. 2015;3(1):24–32. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70291-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang B., Chen J., Li T., Wu H., Yang W., Li Y., et al. Clinical remission of a critically ill COVID-19 patient treated by human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells. ChinaXiv. 2020;99:e21429. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000021429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leng Z., Zhu R., Hou W., Feng Y., Yang Y., Han Q., et al. Transplantation of ACE2-mesenchymal stem cells improves the outcome of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Aging Dis. 2020;11(2):216–228. doi: 10.14336/AD.2020.0228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pierrakos C., Karanikolas M., Scolletta S., Karamouzos V., Velissaris D. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: pathophysiology and therapeutic options. J Clin Med Res. 2012;4(1):7. doi: 10.4021/jocmr761w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orleans L.A., is Vice H., Manchikanti L. Expanded umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (UC-MSCs) as a therapeutic strategy in managing critically ill COVID-19 patients: the case for compassionate use. Pain Physician. 2020;23:E71–E83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prockop D.J. The exciting prospects of new therapies with mesenchymal stromal cells. Cytotherapy. 2017;19(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lazarus H.M., Haynesworth S.E., Gerson S.L., Caplan A.I. Human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal (stromal) progenitor cells (MPCs) cannot be recovered from peripheral blood progenitor cell collections. J Hematother. 1997;6(5):447–455. doi: 10.1089/scd.1.1997.6.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matthay M.A., Pati S., Lee J.-W. Concise review: mesenchymal stem (stromal) cells: biology and preclinical evidence for therapeutic potential for organ dysfunction following trauma or sepsis. Stem Cells. 2017;35(2):316–324. doi: 10.1002/stem.2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Witte S.F.H., Peters F.S., Merino A., Korevaar S.S., Van Meurs J.B.J., O’Flynn L., et al. Epigenetic changes in umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells upon stimulation and culture expansion. Cytotherapy. 2018;20(7):919–929. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2018.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Witte S.F.H., Lambert E.E., Merino A., Strini T., Douben H.J.C.W., O’Flynn L., et al. Aging of bone marrow-and umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stromal cells during expansion. Cytotherapy. 2017;19(7):798–807. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2017.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caplan A.I., Sorrell J.M. The MSC curtain that stops the immune system. Immunol Lett. 2015;168(2):136–139. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riquelme P., Haarer J., Kammler A., Walter L., Tomiuk S., Ahrens N., et al. TIGIT+ iTregs elicited by human regulatory macrophages control T cell immunity. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05167-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng G., Huang R., Qiu G., Ge M., Wang J., Shu Q., et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles: regenerative and immunomodulatory effects and potential applications in sepsis. Cell Tissue Res. 2018;374(1):1–15. doi: 10.1007/s00441-018-2871-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melief S.M., Schrama E., Brugman M.H., Tiemessen M.M., Hoogduijn M.J., Fibbe W.E., et al. Multipotent stromal cells induce human regulatory T cells through a novel pathway involving skewing of monocytes toward anti-inflammatory macrophages. Stem Cells. 2013;31(9):1980–1991. doi: 10.1002/stem.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deng Y., Zhang Y., Ye L., Zhang T., Cheng J., Chen G., et al. Umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells instruct monocytes towards an IL10-producing phenotype by secreting IL6 and HGF. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep37566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fedorenko E., Behr M.K., Kanwisher N. Functional specificity for high-level linguistic processing in the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108(39):16428–16433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112937108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramasamy R., Fazekasova H., Lam E.W.F., Soeiro Is, Lombardi G., Dazzi F. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit dendritic cell differentiation and function by preventing entry into the cell cycle. Transplantation. 2007;83(1):71–76. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000244572.24780.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marson A., Kretschmer K., Frampton G.M., Jacobsen E.S., Polansky J.K., MacIsaac K.D., et al. Foxp3 occupancy and regulation of key target genes during T-cell stimulation. Nature. 2007;445(7130):931–935. doi: 10.1038/nature05478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakaguchi S., Sakaguchi N., Asano M., Itoh M., Toda M. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol Res. 1995;155(3):1151–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duijvestein M., Wildenberg M.E., Welling M.M., Hennink S., Molendijk I., van Zuylen V.L., et al. Pretreatment with interferon gamma enhances the therapeutic activity of mesenchymal stromal cells in animal models of colitis. Stem Cells. 2011;29(10):1549–1558. doi: 10.1002/stem.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim H.-S., Shin T.-H., Lee B.-C., Yu K.-R., Seo Y., Lee S., et al. Human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells reduce colitis in mice by activating NOD2 signaling to COX2. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(6):1392–1403. e8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta N., Krasnodembskaya A., Kapetanaki M., Mouded M., Tan X., Serikov V., et al. Mesenchymal stem cells enhance survival and bacterial clearance in murine Escherichia coli pneumonia. THORAX. 2012;67(6):533–539. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta N., Su X., Popov B., Lee J.W., Serikov V., Matthay M.A. Intrapulmonary delivery of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells improves survival and attenuates endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in mice. J Immunol. 2007;179(3):1855–1863. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Islam M.N., Das S.R., Emin M.T., Wei M., Sun L., Westphalen K., et al. Mitochondrial transfer from bone-marrow-derived stromal cells to pulmonary alveoli protects against acute lung injury. Nat Med. 2012;18(5):759. doi: 10.1038/nm.2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krasnodembskaya A., Samarani G., Song Y., Zhuo H., Su X., Lee J.-W., et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells reduce mortality and bacteremia in gram-negative sepsis in mice in part by enhancing the phagocytic activity of blood monocytes. Am J Physiol-Lung C. 2012;302(10):L1003–L1013. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00180.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mei S.H.J., McCarter S.D., Deng Y., Parker C.H., Liles W.C., Stewart D.J. Prevention of LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice by mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing angiopoietin 1. PLoS Med. 2007;4(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mei S.H.J., Haitsma J.J., Dos Santos C.C., Deng Y., Lai P.F.H., Slutsky A.S., et al. Mesenchymal stem cells reduce inflammation while enhancing bacterial clearance and improving survival in sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(8):1047–1057. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0010OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nemeth K., Mayer B., Mezey E. Modulation of bone marrow stromal cell functions in infectious diseases by toll-like receptor ligands. J Mol Med. 2010;88(1):5–10. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0523-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu J., Woods C.R., Mora A.L., Joodi R., Brigham K.L., Iyer S., et al. Prevention of endotoxin-induced systemic response by bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in mice. Am J Physiol-Lung C. 2007;293(1):L131–L141. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00431.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Opitz C.A., Litzenburger U.M., Lutz C., Lanz T.V., Tritschler I., Koppel A., et al. Toll-like receptor engagement enhances the immunosuppressive properties of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells by inducing indoleamine-2, 3-dioxygenase-1 via interferon-beta and protein kinase R. Stem Cells. 2009;27(4):909–919. doi: 10.1002/stem.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lombardo E., DelaRosa O., Mancheno-Corvo P., Menta R., Ramirez C., Buscher D. Toll-like receptor-mediated signaling in human adipose-derived stem cells: implications for immunogenicity and immunosuppressive potential. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15(7):1579–1589. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Witwer K.W., Buzas E.I., Bemis L.T., Bora A., Lasser C., Lotvall J., et al. Standardization of sample collection, isolation and analysis methods in extracellular vesicle research. J Extracell Vesicles. 2013;2(1) doi: 10.3402/jev.v2i0.20360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gould S.T., Anseth K.S. Role of cell-matrix interactions on VIC phenotype and tissue deposition in 3D PEG hydrogels. J Tissue Eng. Regen M. 2016;10(10):E443–E453. doi: 10.1002/term.1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park J., Kim S., Lim H., Liu A., Hu S., Lee J., et al. Therapeutic effects of human mesenchymal stem cell microvesicles in an ex vivo perfused human lung injured with severe E. coli pneumonia. Thorax. 2019;74(1):43–50. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang B., Yin Y., Lai R.C., Tan S.S., Choo A.B.H., Lim S.K. Mesenchymal stem cells secrete immunologically active exosomes. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23(11):1233–1244. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gennai S., Monsel A., Hao Q., Park J., Matthay M.A., Lee J.W. Microvesicles derived from human mesenchymal stem cells restore alveolar fluid clearance in human lungs rejected for transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(9):2404–2412. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khoury M., Cuenca J., Cruz F.F., Figueroa F.E., Rocco P.R.M., Weiss D.J. Current status of cell-based therapies for respiratory virus infections: applicability to COVID-19. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:1–18. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00858-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bader P., Kuci Z., Bakhtiar S., Basu O., Bug G., Dennis M., et al. Effective treatment of steroid and therapy-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease with a novel mesenchymal stromal cell product (MSC-FFM) Bone Marrow Transplant. 2018;53(7):852–862. doi: 10.1038/s41409-018-0102-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fisher SA, Cutler A, Doree C, Brunskill SJ, Stanworth SJ, Navarrete C, Girdlestone J. Mesenchymal stromal cells as treatment or prophylaxis for acute or chronic graft-versus-host disease in haematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients with a haematological condition. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019(1). DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009768.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Munneke J.M., Spruit M.J.A., Cornelissen A.S., van Hoeven V., Voermans C., Hazenberg M.D. The potential of mesenchymal stromal cells as treatment for severe steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease: a critical review of the literature. Transplantation. 2016;100(11):2309–2314. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rizk M., Monaghan M., Shorr R., Kekre N., Bredeson C.N., Allan D.S. Heterogeneity in studies of mesenchymal stromal cells to treat or prevent graft-versus-host disease: a scoping review of the evidence. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(8):1416–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elgaz S., Kuci Z., Kuci S., Bonig H., Bader P. Clinical use of mesenchymal stromal cells in the treatment of acute graft-versus-host disease. Transfus Med Hemother. 2019;46(1):27–34. doi: 10.1159/000496809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Galleu A., Milojkovic D., Deplano S., Szydlo R., Loaiza S., Wynn R., et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells for acute graft-versus-host disease: response at 1 week predicts probability of survival. Br J Haematol. 2019;185(1):89–92. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Caimi P.F., Reese J., Lee Z., Lazarus H.M. Emerging therapeutic approaches for multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) Curr Opin Hematol. 2010;17(6):505. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32833e5b18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koc O.N., Gerson S.L., Cooper B.W., Dyhouse S.M., Haynesworth S.E., Caplan A.I., et al. Rapid hematopoietic recovery after coinfusion of autologous-blood stem cells and culture-expanded marrow mesenchymal stem cells in advanced breast cancer patients receiving high-dose chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(2):307. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lazarus H.M., Koc O.N., Devine S.M., Curtin P., Maziarz R.T., Holland H.K., et al. Cotransplantation of HLA-identical sibling culture-expanded mesenchymal stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells in hematologic malignancy patients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11(5):389–398. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martin P.J., Uberti J.P., Soiffer R.J., Klingemann H., Waller E.K., Daly A.S., et al. Prochymal improves response rates in patients with steroid-refractory acute graft versus host disease (SR-GVHD) involving the liver and gut: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase III trial in GVHD. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(2):S169–S170. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kebriaei P., Hayes J., Daly A., Uberti J., Marks D.I., Soiffer R., et al. A phase 3 randomized study of remestemcel-L versus placebo added to second-line therapy in patients with steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;26:835–844. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kurtzberg J., Abdel-Azim H., Carpenter P., Chaudhury S., Horn B., Mahadeo K., et al. A phase 3, single-arm, prospective study of remestemcel-L, ex vivo culture-expanded adult human mesenchymal stromal cells for the treatment of Pediatric patients who failed to respond to steroid treatment for acute graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020;26(5):845–854. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hashmi S., Ahmed M., Murad M.H., Litzow M.R., Adams R.H., Ball L.M., et al. Survival after mesenchymal stromal cell therapy in steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Haematol. 2016;3(1):e45–e52. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(15)00224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cyranoski D. Canada approves stem cell product. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(7):571. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zheng G., Huang L., Tong H., Shu Q., Hu Y., Ge M., et al. Treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome with allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells: a randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study. Respir Res. 2014;15(1):39. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-15-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matthay M.A., Calfee C.S., Zhuo H., Thompson B.T., Wilson J.G., Levitt J.E., et al. Treatment with allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells for moderate to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (START study): a randomised phase 2a safety trial. Lancet Resp. Med. 2019;7(2):154–162. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30418-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dave M., Mehta K., Luther J., Baruah A., Dietz A.B., Faubion W.A., Jr. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(11):2696–2707. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li Y., Xu J., Shi W., Chen C., Shao Y., Zhu L., et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell treatment prevents H9N2 avian influenza virus-induced acute lung injury in mice. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2016;7(1) doi: 10.1186/s13287-016-0395-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen J., Li C., Gao X., Li C., Liang Z., Yu L., et al. Keratinocyte growth factor gene delivery via mesenchymal stem cells protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moodley Y., Vaghjiani V., Chan J., Baltic S., Ryan M., Tchongue J., et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of adult stem cells in sustained lung injury: a comparative study. PloS One. 2013;8(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xu J., Qu J., Cao L., Sai Y., Chen C., He L., et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-based angiopoietin-1 gene therapy for acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide in mice. J Pathol. 2008;214(4):472–481. doi: 10.1002/path.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gotts J.E., Abbott J., Matthay M.A. Influenza causes prolonged disruption of the alveolar-capillary barrier in mice unresponsive to mesenchymal stem cell therapy. Am J Physiol-Lung C. 2014;307(5):L395–L406. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00110.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chan M.C.W., Kuok D.I.T., Leung C.Y.H., Hui K.P.Y., Valkenburg S.A., Lau E.H.Y., et al. Human mesenchymal stromal cells reduce influenza A H5N1-associated acute lung injury in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113(13):3621–3626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601911113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Darwish I., Banner D., Mubareka S., Kim H., Besla R., Kelvin D.J., et al. Mesenchymal stromal (stem) cell therapy fails to improve outcomes in experimental severe influenza. PLoS One. 2013;8(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li H., Chen C., Hu F., Wang J., Zhao Q., Gale R.P., et al. Impact of corticosteroid therapy on outcomes of persons with SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, or MERS-CoV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Leukemia. 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0848-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee R.H., Pulin A.A., Seo M.J., Kota D.J., Ylostalo J., Larson B.L., et al. Intravenous hMSCs improve myocardial infarction in mice because cells embolized in lung are activated to secrete the anti-inflammatory protein TSG-6. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5(1):54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Krasnodembskaya A., Song Y., Fang X., Gupta N., Serikov V., Lee J.-W., et al. Antibacterial effect of human mesenchymal stem cells is mediated in part from secretion of the antimicrobial peptide LL-37. Stem Cells. 2010;28(12):2229–2238. doi: 10.1002/stem.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Qu W., Wang Z., Hare J.M., Bu G., Mallea J.M., Pascual J.M., et al. Cell-based therapy to reduce mortality from COVID-19: systematic review and meta-analysis of human studies on acute respiratory distress syndrome. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2020 May 29 doi: 10.1002/sctm.20-0146. [2020] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sengupta V., Sengupta S., Lazo J.A., Woods P., Nolan A., Bremer N. Exosomes derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells as treatment for severe COVID-19. Stem Cells Dev. 2020;29(12):747–754. doi: 10.1089/scd.2020.0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lalu M.M., McIntyre L., Pugliese C., Fergusson D., Winston B.W., Marshall J.C., et al. Canadian critical care trials G. safety of cell therapy with mesenchymal stromal cells (SafeCell): a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. PloS One. 2012;7:10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Genc B., Bozan H.R., Genc S., Genc K. Stem cell therapy for multiple sclerosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1084:145–174. doi: 10.1007/5584_2018_247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Peng Y., Ke M., Xu L., Liu L., Chen X., Xia W., et al. Donor-derived mesenchymal stem cells combined with low-dose tacrolimus prevent acute rejection after renal transplantation: a clinical pilot study. Transplantation. 2013;95(1):161–168. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182754c53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tan J., Wu W., Xu X., Liao L., Zheng F., Messinger S., et al. Induction therapy with autologous mesenchymal stem cells in living-related kidney transplants: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2012;307(11):1169–1177. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fan M., Huang Y., Chen Z., Xia Y., Chen A., Lu D., et al. Efficacy of mesenchymal stem cell therapy in systolic heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1) doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1258-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cyranoski D. Korean deaths spark inquiry: cases highlight the challenge of policing multinational trade in stem-cell treatments. Nature. 2010;468(7323):485–486. doi: 10.1038/468485a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jung J.W., Kwon M., Choi J.C., Shin J.W., Park I.W., Choi B.W., et al. Familial occurrence of pulmonary embolism after intravenous, adipose tissue-derived stem cell therapy. Yonsei Med J. 2013;54(5):1293–1296. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2013.54.5.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vulliet P.R., Greeley M., Halloran S.M., MacDonald K.A., Kittleson M.D. Intra-coronary arterial injection of mesenchymal stromal cells and microinfarction in dogs. Lancet. 2004;363(9411):783–784. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15695-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tatsumi K., Ohashi K., Matsubara Y., Kohori A., Ohno T., Kakidachi H., et al. Tissue factor triggers procoagulation in transplanted mesenchymal stem cells leading to thromboembolism. Biochem Biophys Res. 2013;431(2):203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.12.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Christy B.A., Herzig M.C., Montgomery R.K., Delavan C., Bynum J.A., Reddoch K.M., et al. Procoagulant activity of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83(1):S164–S169. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]