Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Akin to the nonoperative management of benign intracranial tumors, stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) has emerged as a nonoperative treatment option for noninfiltrative primary spine tumors such as meningioma and schwannoma. The majority of initial series used higher doses of 16–24 Gy in 1–3 fractions. The authors hypothesized that lower doses (such as 12–13 Gy in 1 fraction) might provide an efficacy similar to that found with the dose de-escalation commonly used for intracranial radiosurgery to treat acoustic neuroma or meningioma and with a lower risk of toxicity.

METHODS

The authors identified 38 patients in a prospectively maintained institutional radiosurgery database who were treated with definitive SBRT for a total of 47 benign primary spine tumors between 2004 and 2016. SBRT consisted of 9–21 Gy in 1–3 fractions using the CyberKnife (n = 11 [23%]), Synergy S (n = 21 [45%]), or TrueBeam (n = 15 [32%]) radiosurgery platform. For a comparison of SBRT doses, patients were dichotomized into 1 of 2 groups (low-dose or high-dose SBRT) using a cutoff biologically effective dose (BED10Gy) of 30 Gy. Tumor control was calculated from the date of SBRT to the last follow-up using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, with comparisons between groups completed using a log-rank method. To account for potential indication bias, a propensity score analysis was completed based on the conditional probabilities of SBRT dose selection. Toxicity was graded using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0 with a focus on grade 3+ toxicity and the incidence of pain flare.

RESULTS

For the 38 patients, the most common histological findings were meningioma (15 patients), schwannoma (13 patients), and hemangioblastoma (7 patients). The median age at SBRT was 58 years (range 25–91 years). The 47 treated lesions were located in the cervical (n = 18), thoracic (n = 19), or lumbosacral (n = 10) spine. Five (11%) lesions were lost to follow-up after SBRT. The median follow-up duration for the remaining 42 lesions was 54 months (range 1.2–133 months). Six (16%) patients (with a total of 8 lesions) experienced pain flare after SBRT; no significant predictor of pain flare was identified. No grade 3+acute- or late-onset complication was noted. The 5-year local control rate was 76% (95% CI 61%–91%). No significant difference in local control according to dose, fractionation, previous radiation, surgery, tumor histology, age, treatment platform, planning target volume, or spine level treated was found. The 5-year local control rates for low- and high-dose treatments were 73% (95% CI 53%–93%) and 83% (95% CI 61%–100%) (p = 0.52). In propensity score–adjusted multivariable analysis, no difference in local control was identified (HR 0.30, 95% CI 0.02–5.40; p = 0.41).

CONCLUSIONS

Long-term follow-up of patients treated with SBRT for benign spinal lesions revealed no significant difference between low-dose (BED10Gy ≤ 30) and high-dose SBRT in local control, pain-flare rate, or long-term toxicity.

Keywords: SBRT, spine, dose, benign tumors, meningioma, schwannoma, hemangioblastoma, oncology

THE majority of primary spinal cord tumors are benign noninfiltrative lesions, such as meningiomas or schwannomas, for which microsurgical resection has long been recognized as a standard of care.1 However, tumor location, patient age, and medical comorbidities can challenge the application of microsurgery. Building on the successful use of stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for the management of malignant metastatic spinal tumors and frame-based stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) for unresectable benign intracranial lesions, SBRT for benign spinal tumors was initially reported in the late 1990s.2,5 Reports from numerous additional single-institution cohort series that highlight the potential safety and efficacy of SBRT as a nonoperative alternative for a variety of benign spinal tumors have since been published.3,5,8,17,18 Unlike patients treated with SBRT for malignant metastatic spinal tumors, patients with benign spine tumors have a long natural history. Continuous long-term follow-up is warranted both for the evaluation of tumor control and to address concerns regarding delayed myelopathy caused by the extreme hypofractionation inherent to spinal SBRT.

The majority of the initial experiences with SBRT for benign primary spinal tumors involved a dose similar to that used for malignant metastatic spinal tumors (i.e., 16–30 Gy in 1–5 fractions).3,5,8,17,18 Similarly, intracranial application of SRS for benign tumors, such as meningioma and acoustic neuroma, began with a high dose similar to that used to treat malignant intracranial tumors. Additional experience with intracranial SRS dose de-escalation to 12–13 Gy in 1 fraction was found to reduce toxicity while maintaining excellent rates of tumor control.6,11,14 Contemporary reports of outcomes with long-term follow-up and use of lower-dose spinal SBRT in patients with benign tumors have been limited.15,19 Thus, we aimed to assess the long-term outcomes in patients after spinal SBRT for benign tumors. We hypothesized that lower doses (such as 12–13 Gy in 1 fraction) might provide an efficacy similar to that found with the dose de-escalation commonly used for intracranial radiosurgery to treat acoustic neuroma or meningioma and a lower risk of toxicity.

Methods

After institutional review board approval, our prospectively maintained institutional radiosurgery database was queried to identify patients treated with SBRT for benign primary spinal tumors between 2004 and 2016. Patients were included irrespective of previous treatments (including surgery) and tumor location (intradural or extradural). Patients with malignant or metastatic tumors were excluded. SBRT consisted of 9–21 Gy in 1–3 fractions using the CyberKnife (Accuray, Inc.), Synergy S (Elekta), or TrueBeam (Varian Medical Systems) radiosurgery platform. Our technique for spinal SBRT was described previously.8,13 In brief, SBRT targets included a gross tumor volume without a clinical target volume expansion; gross tumor volume–to–planning target volume expansions of 0–2 mm were based on treatment-delivery platform and physician preference. Daily image guidance was used in all cases with near-real-time 6-D tracking (Xsight Spine, Accuray, Inc.), daily cone-beam CT, and/or the ExacTrac system (Brainlab Novalis). Immobilization for linear accelerator-based radiosurgery-delivery platforms was accomplished by using either the BodyFIX system (Elekta) or a custom thermoplastic mask, depending on tumor location. Follow-up included MRI at 6-month intervals after the completion of SBRT.

Statistical analyses were completed using IBM SPSS 22. For a comparison of SBRT doses, the patients’ lesions were dichotomized into 1 of 2 groups, low-dose SBRT (n = 34) or high-dose SBRT (n = 8), using a cutoff median biologically effective dose (BED10Gy) value of 30 Gy. Tumor control was calculated from the date of SBRT to the last follow-up visit using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, and comparisons between groups were completed using a log-rank method. Local control was defined as either a stable or smaller lesion size. To account for potential indication bias, a propensity score analysis was completed based on the conditional probabilities of SBRT dose selection with nearest-neighbor propensity score matching. Toxicity was graded using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0 with a focus on grade 3+ toxicities and the incidence of pain flare.

Results

For the included 38 patients the most common histological findings were meningioma (15 patients), schwannoma (13 patients), and hemangioblastoma (7 patients). The median age at SBRT was 58 years (interquartile range 25–91 years). The 47 treated lesions were located in the cervical (n = 18), thoracic (n = 19), or lumbosacral (n = 10) spine. Of these lesions, 8 (17%) were previously irradiated, and surgery had previously been performed for 25 (53%). Five (11%) lesions were lost to follow-up after SBRT. Each lesion was treated using the CyberKnife (n = 11), Synergy S (n = 21), or TrueBeam (n = 15) radiosurgery platform. The median spinal cord maximum dose was 11.6 Gy (interquartile range 10–13.2 Gy). Table 1 provides baseline patient and tumor characteristics.

TABLE 1.

Patient (n = 38), lesion (n = 47), and treatment characteristics

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Patient age in yrs (median [range]) | 58 (25–91) |

| Patient sex | |

| Male | 16 (42) |

| Female | 22 (58) |

| Treatment platform | |

| CyberKnife | 11 (23) |

| TrueBeam | 15 (32) |

| Synergy S | 21 (45) |

| Histology | |

| Hemangioblastoma | 10 (21) |

| Meningioma | 18 (38) |

| Paraganglioma | 1 (2) |

| Schwannoma | 18 (38) |

| Spine level treated | |

| Cervical | 18 (38) |

| Thoracic | 19 (40) |

| Lumbosacral | 10 (21) |

| Previous radiotherapy | |

| Yes | 8 (17) |

| No | 39 (83) |

| Previous surgery | |

| Yes | 25 (53) |

| No | 22 (47) |

| SBRT dose in Gy (median [IQR]) | 13 (12–17) |

Values shown are number (%) unless specified otherwise.

The median follow-up duration for the 42 lesions with available follow-up data was 54 months (range 1.2–133 months). Six (16%) patients (with a total of 8 lesions) had a pain flare after SBRT. No significant predictor of pain flare was identihed; we found no difference according to dose (low versus high), fractionation (single versus multifractionation), previous radiation, previous surgery, tumor histology, age, treatment platform, planning target volume, or spine level treated. Table 2 lists the incidence of pain flare, and a chi-square analysis revealed no significant correlation between any of the factors. No grade 3+ acute- or late-onest complication was noted; 1 patient who suffered local recurrence that required salvage SRS and surgery had grade 2 myelitis manifested as imbalance and impaired proprioception.

TABLE 2.

Pain-flare correlation chi-square analysis

| No. of Lesions |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| No Pain Flare (n = 32) | Pain Flare (n = 8) | p Value | |

| Fractions | 0.245 | ||

| 1 | 26 | 5 | |

| 3 | 6 | 3 | |

| Previous surgery | 0.118 | ||

| Yes | 18 | 2 | |

| No | 14 | 6 | |

| SBRT dose | 0.487 | ||

| High (BED10Gy >30 Gy) | 7 | 1 | |

| Low (BED10Gy ≤30 Gy) | 25 | 7 | |

| Histology* | 0.383 | ||

| Meningioma | 11 | 2 | |

| Schwannoma | 14 | 3 | |

| Hemangioblastoma | 5 | 2 | |

| Age | 0.118 | ||

| ≤57 yrs | 14 | 6 | |

| >57 yrs | 18 | 2 | |

| Spinal segment | 0.487 | ||

| Cervical | 11 | 3 | |

| Thoracic | 11 | 4 | |

| Lumbosacral | 10 | 1 | |

| Radiosurgery platform | 0.230 | ||

| CyberKnife | 8 | 1 | |

| TrueBeam | 12 | 2 | |

| Synergy S | 12 | 5 | |

Complete background (pretreatment) data were available for only 40 of the 47 treated lesions.

Meningioma, schwannoma, and hemangioblastoma represented the 3 most common tumor histology types but were not the only types found.

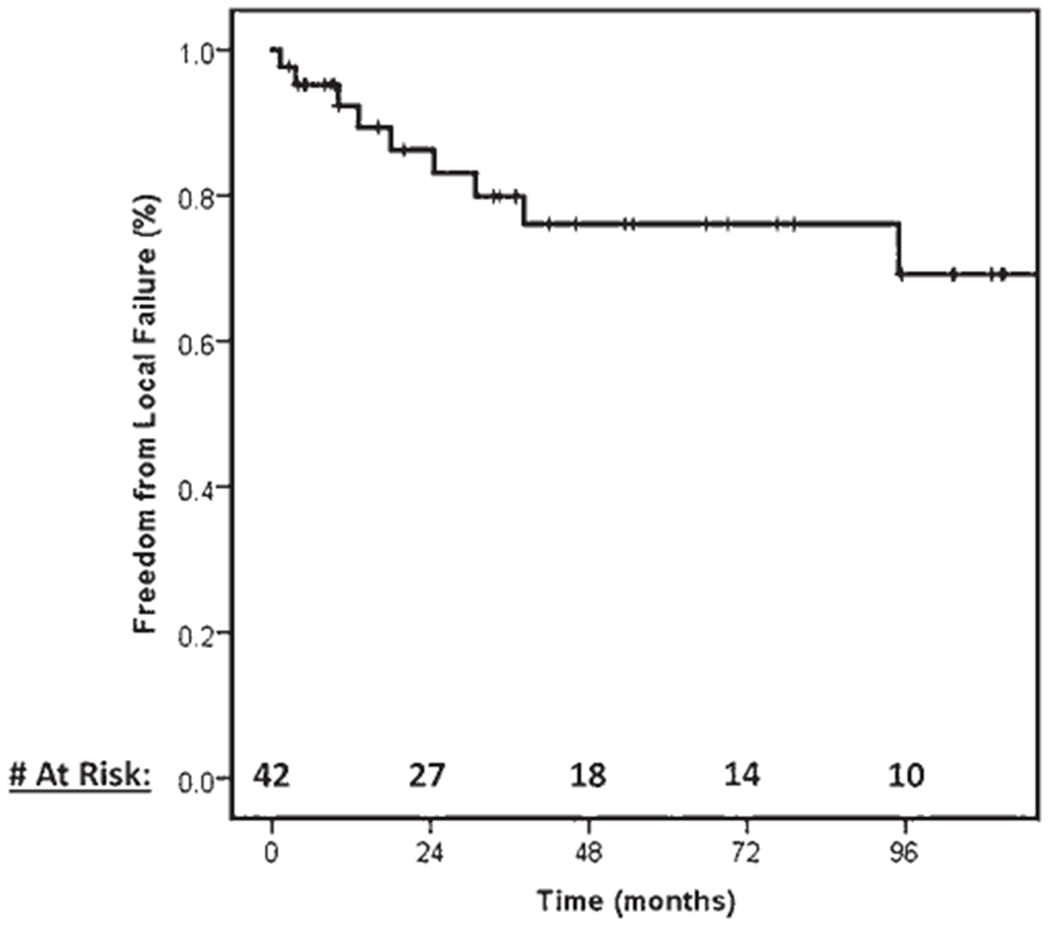

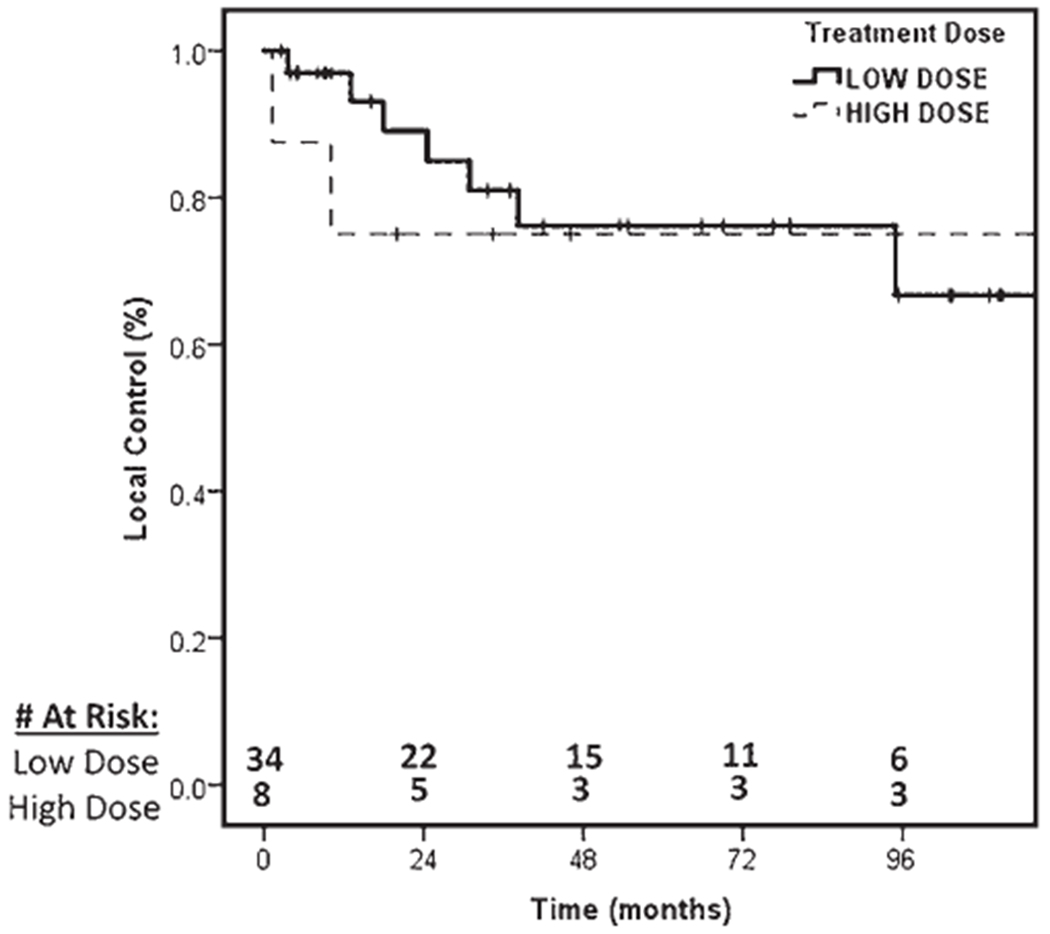

The 5-year local control rate was 76% (95% CI 61%–91%), as found using a Kaplan-Meier survival plot (Fig. 1). We found no significant difference in local control rates according to dose (low [BED10Gy ≤ 30 Gy] vs high [BED10Gy > 30 Gy]), fractionation (single versus multifractionation), previous radiation, previous surgery, tumor histology, age, treatment platform, planning target volume, or spine level treated (p > 0.05). Durable control of pain after treatment was experienced by 80% of the patients. No significant difference between the high- and low-dose groups in baseline patient or tumor characteristics was identified other than an increased use of the CyberKnife platform in the high-dose group. The 5-year local control rates for the low-dose and high-dose groups were 73% (95% CI 53%–93%) and 83% (95% 61%–100%), respectively (p = 0.52). Fig. 2 shows a Kaplan-Meier survival plot that compares the local control rates in the high- and low-dose groups. A propensity score–matched multivariable analysis identified no difference in local control rates (HR 0.30, 95% CI 0.02–5.40, p = 0.41).

FIG. 1.

Local control of benign spinal lesions treated with SBRT.

FIG. 2.

Local control of benign spinal tumors treated with low-dose (BED10Gy ≤ 30 Gy) or high-dose (BED10Gy > 30 Gy) SBRT.

Discussion

Modern radiation treatment-planning and -delivery techniques have enabled a safe escalation of dose per fraction while targeting lesions in close proximity to the spinal cord. Analogous to the initial experiences with intracranial SRS, treatment of benign lesions began by prescribing doses necessary to control malignant/metastatic lesions (i.e., 20–30 Gy in 1–5 fractions).3,5,8,17,18 A greater understanding of the natural history and responsive nature of most benign intracranial lesions has prompted a de-escalation of prescribed SRS doses with similar excellent rates of local control and further avoidance of treatment-related toxicity.6,11,14 The majority of modern series to date have included a large spectrum of dose schedules without a comparison of outcomes between each of them.3,5,8,17,18 The results of our analysis revealed no significant patient characteristic that was predictive of receiving high- or low-dose SBRT, and we found that patients were less likely to receive a high dose when the TrueBeam or Synergy S platform was used (Table 3). To our knowledge, few data sets have reported parallel findings with de-escalation of SBRT doses for the treatment of benign intraspinal lesions.

TABLE 3.

Patient characteristics and SBRT dose analysis

| No. of Lesions |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient or Dose Characteristic | Low-Dose Group (BED10Gy ≤ 30 Gy) (n = 34) | High-Dose Group (BED10Gy > 30 Gy) (n = 8) | p Value |

| Patient age | 0.132 | ||

| ≤57 yrs | 15 | 6 | |

| >57 yrs | 19 | 2 | |

| Spinal segment | 0.707 | ||

| Cervical | 12 | 2 | |

| Thoracic | 14 | 3 | |

| Lumbosacral | 8 | 3 | |

| Histology | 0.418 | ||

| Meningioma | 11 | 3 | |

| Schwannoma | 15 | 3 | |

| Hemangioblastoma | 7 | 0 | |

| Other | 1 | 2 | |

| Previous surgery | 0.881 | ||

| Yes | 18 | 4 | |

| No | 16 | 4 | |

| Previous radiation | 0.604 | ||

| Yes | 7 | 1 | |

| No | 27 | 7 | |

| Radiosurgery platform | 0.047 | ||

| CyberKnife | 3 | 6 | |

| TrueBeam | 13 | 2 | |

| Synergy S | 18 | 0 | |

Our retrospective review of 38 patients who underwent SBRT for a total of 47 benign spine tumors revealed a 5-year local control rate of 76%, and no significant difference was found among patients who underwent low-dose (BED10Gy ≤ 30 Gy) treatment and those who underwent high-dose (BED10Gy > 30 Gy) treatment or in those with a single-fraction plan and those with a multifractionation plan. Initial dose selection was determined by lesion size and proximity to the spinal cord, with a temporal association with lower dose use (i.e., patients were more likely to receive a lower dose toward the end of our review period). Our threshold for low and high doses was based on the median dose across the entire patient cohort. Several separate analyses using different high- and low-dose thresholds were performed, each of which yielded findings similar to those reported here. Table 4 summarizes the published literature that supports the use of SBRT for benign spinal tumors to date. Our local control rate was similar to that found in historical higher-dose series and was associated with durable pain control in 80% of patients. These findings are more compelling when we consider that SBRT served as a salvage modality after surgery for 25 (53%) lesions and previous radiotherapy was provided for 8 (17%) of the lesions in this cohort. Of all the patients treated, no grade 3+ acute- or late-onset complication was experienced, and one grade 2 myelitis was noted in a patient who underwent 2 courses of SRS and previous surgery. This extremely low toxicity rate is in line with those in previous reports from Stanford18 and high-dose series from our institution8,9 (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Summary of previous series of SBRT for benign spinal lesions

| Author & Year | No. of Patients | Dose (Gy)/No. of Fractions | Histology (no. of tumors)* | Median Follow-Up (mos) | Previous Treatment | Local Control | Late Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chang et al., 1998 | 3 | 21/3 (hemangioblastoma); 21/1 (AVM) | Hemangioblastoma (2); AVM (1) | 18 | None | 33%–70% size reduction | None |

| Dodd et al., 2006 | 51 | 16/1–30/5 | Schwannoma (30); meningioma (16); neurofibroma (9) | 36 | Surgery (51%) | Partial response at all sites | Grade 2+ radiation myelopathy (n = 1) |

| Ryu et al., 2001 | 11 | 11/1–25/5 | Hemangioblastoma (1); AVM (6); schwannoma (2); meningioma (1); chordoma (1) | 6 | Surgery (n = 4); XRT (n = 2) | 100% | None |

| De Salles et al., 2004 | 3 | 12/1 | Neurofibroma (2); meningioma (1) | 6 | Surgery (n = 3); XRT (n = 1) | 70% | 0% |

| Marchetti et al., 2013 | 18 | 10/1–25/5 | Schwannoma (9); meningioma (11); neurofibroma (1) | 43 | Surgery (n = 14); XRT (n = 1) | 100% | 0% |

| Gerszten et al., 20129 | 45 | 12/1–24/1 | Schwannoma (16); meningioma (10); neurofibroma (14) | 32 | Surgery (n = 21); XRT (n = 2) | NR | 0% |

| Gerszten et al., 201210 | 40 | 11/1–21/3 | Schwannoma (15); meningioma (8); neurofibroma (7) | 26 | Surgery (n = 18); XRT (n = 4) | 100% | 0% |

| Gerszten et al., 2008 | 73 | 15/1–25/3 | Schwannoma (35); meningioma (13); neurofibroma (25) | 37 | Surgery (n = 19); XRT (n = 6) | 100% | Grade 2+ radiation myelopathy (n = 3) |

| Gagnon et al., 2009 | 13 | 21/3–37.5/5 | Schwannoma (6); meningioma (5); neurofibroma (2) | 12 | 63% surgery; XRT | NR | 0% |

| Sahgal et al., 2007 | 16 | 10/1–30/5 | Meningioma (2); chordoma (4); hemangioma (2); neurofibroma (11) | 25 | Surgery (n = 5); XRT (n = 2) | 89% | 0% |

| Current cohort | 38 | 9/1–21/3 | Schwannoma (13); meningioma (15); hemangioblastoma (7) | 54 | Surgery (n = 25); XRT (n = 8) | 76% | Grade 2+ radiation myelopathy (n = 1) |

AVM = arteriovenous malformation; NR = not reported; XRT = conventional radiotherapy.

Some patients had more than 1 tumor.

We recognize the limitations of this study, which include its retrospective nature and the potential for selection bias, both when treatment was initiated and when we reviewed the patient records. This study also included significant heterogeneity in lesion histology, similar to most studies of SBRT for benign spine tumors, and standardized follow-up was lacking. In addition, after treatment, 5 lesions were subsequently lost to follow-up. With a small sample size, this study was limited in power to detect small differences in tumor control according to dose levels. Last, high-dose treatment and the CyberKnife platform were used more often based on a temporal relationship of platform selection and high-dose use in our clinic. Aside from these limitations, this cohort represents one of the largest series and longest follow-ups of benign spine tumors treated with SBRT to date. This report highlights effective local tumor control and minimal toxicity irrespective of SBRT dose in a patient population that was previously treated heavily and in 70% of whom previous surgery or radiation had failed.

Conclusions

Stereotactic radiation therapy represents an effective treatment for benign primary malignancies of the spine. After 5 years of follow-up, we report no significant difference in pain control, local control, pain flare, or long-term toxicity between patients in the high-dose group and those in the low-dose treatment group. Akin to the de-escalation of SRS dose used for benign intracranial tumors, such as meningioma or acoustic neuroma, de-escalation of SBRT to a lower dose might be a reasonable approach for treating benign spinal tumors, even in a salvage setting.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BED10Gy

biologically effective dose

- SBRT

stereotactic body radiation therapy

- SRS

stereotactic radiosurgery

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Vargo receives speaking honoraria from Brainlab.

Previous Presentations

These data were presented at the Annual Meeting of the Radiosurgery Society, Fas Vegas, NV, November 3, 2017.

References

- 1.Chamberlain MC, Tredway TL: Adult primary intradural spinal cord tumors: a review. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 11:320–328, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang SD, Murphy M, Geis P, Martin DP, Hancock SL, Doty JR, et al. Clinical experience with image-guided robotic radiosurgery (the Cyberknife) in the treatment of brain and spinal cord tumors. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 38:780–783, 1998. (Tokyo) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang UK, Rhee CH, Youn SM, Lee DH, Park SQ: Radiosurgery using the Cyberknife for benign spinal tumors: Korea Cancer Center Hospital experience. J Neurooncol 101:91–99, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Salles AA, Pedroso AG, Medin P, Agazaryan N, Solberg T, Cabatan-Awang C, et al. Spinal lesions treated with Novalis shaped beam intensity-modulated radiosurgery and stereotactic radiotherapy. J Neurosurg 101 (Suppl 3):435–440, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dodd RL, Ryu MR, Kamnerdsupaphon P, Gibbs IC, Chang SD Jr, Adler JR Jr: CyberKnife radiosurgery for benign intradural extramedullary spinal tumors. Neurosurgery 58:674–685, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flickinger JC, Kondziolka D, Lunsford LD: Dose and diameter relationships for facial, trigeminal, and acoustic neuropathies following acoustic neuroma radiosurgery. Radiother Oncol 41:215–219, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gagnon GJ, Nasr NM, Liao JJ, Molzahn I, Marsh D, McRae D, et al. Treatment of spinal tumors using cyberknife fractionated stereotactic radiosurgery: pain and quality-of-life assessment after treatment in 200 patients. Neurosurgery 64:297–307, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerszten PC, Burton SA, Ozhasoglu C, McCue KJ, Quinn AE: Radiosurgery for benign intradural spinal tumors. Neurosurgery 62:887–896, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerszten PC, Chen S, Quader M, Xu Y, Novotny J Jr, Flickinger JC: Radiosurgery for benign tumors of the spine using the Synergy S with cone-beam computed tomography image guidance. J Neurosurg 117 (Suppl):197–202, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerszten PC, Quader M, Novotny J Jr, Flickinger JC: Radiosurgery for benign tumors of the spine: clinical experience and current trends. Technol Cancer Res Treat 11:133–139, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kondziolka D, Niranjan A, Lunsford LD, Flickinger JC: Stereotactic radiosurgery for meningiomas. Neurosurg Clin N Am 10:317–325, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marchetti M, De Martin E, Milanesi I, Fariselli L: Intradural extramedullary benign spinal lesions radiosurgery. Medium- to long-term results from a single institution experience. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 155:1215–1222, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monserrate A, Zussman B, Ozpinar A, Niranjan A, Flickinger JC, Gerszten PC: Stereotactic radiosurgery for intradural spine tumors using cone-beam CT image guidance. Neurosurg Focus 42(1):E11, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niranjan A, Funsford ED, Flickinger JC, Maitz A, Kondziolka D: Dose reduction improves hearing preservation rates after intracanalicular acoustic tumor radiosurgery. Neurosurgery 45:753–765, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Purvis TE, Goodwin CR, Fubelski D, Faufer I, Sciubba DM: Review of stereotactic radiosurgery for intradural spine tumors. CNS Oncol 6:131–138, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryu SI, Chang SD, Kim DH, Murphy MJ, Fe QT, Martin DP, et al. Image-guided hypo-fractionated stereotactic radiosurgery to spinal lesions. Neurosurgery 49:838–846, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sachdev S, Dodd RE, Chang SD, Soltys SG, Adler JR, Fuxton G, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery yields long-term control for benign intradural, extramedullary spinal tumors. Neurosurgery 69:533–539, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sahgal A, Chou D, Ames C, Ma F, Farnborn K, Huang K, et al. Image-guided robotic stereotactic body radiotherapy for benign spinal tumors: the University of California San Francisco preliminary experience. Technol Cancer Res Treat 6:595–604, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saraceni C, Ashman JB, Harrop JS: Extracranial radiosurgery—applications in the management of benign intradural spinal neoplasms. Neurosurg Rev 32:133–141, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]