Editor:

Patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) present with a wide spectrum of symptoms, but mounting experience is noted with an apparent prothrombotic state. In addition to microvascular thromboses, there are reports of macrovascular thrombotic events in critically ill patients infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (1,2). However, acute limb ischemia was also seen in a patient only minimally symptomatic with SARS-CoV-2 infection and no other risk factors for embolus or thrombosis. The present case report was approved by the institutional review board.

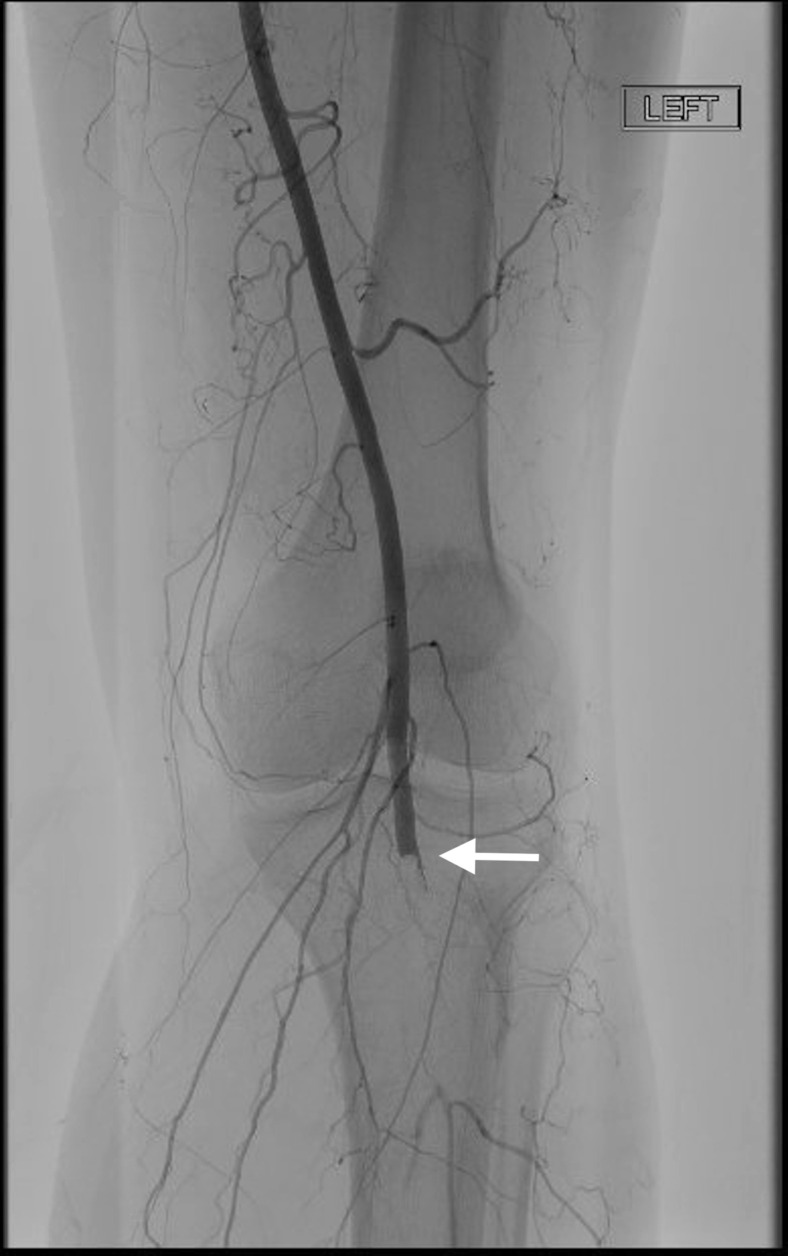

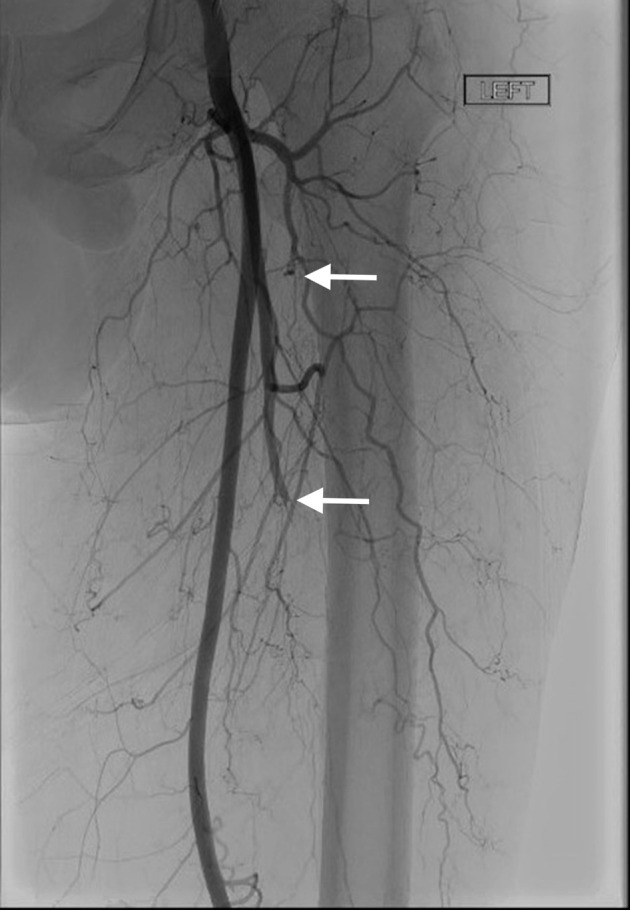

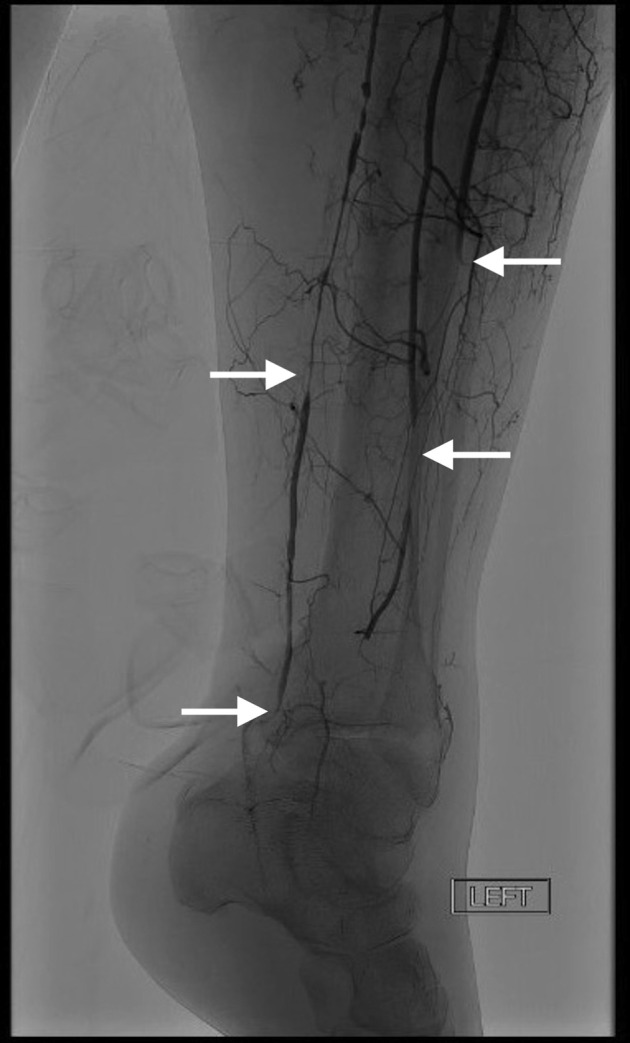

The patient is a 60-year-old obese nonsmoker with hypertension presenting with a 10-day history of fever, sinus congestion, anosmia, ageusia, and 3 days of new-onset left-foot aching pain and coolness, digital numbness, and inability to bear weight. Cardiovascular examination demonstrated a normal sinus rhythm. Physical examination was consistent with acute limb ischemia (Rutherford class IIa). An emergent arteriogram demonstrated thrombus in the distal left profunda femoris artery (Fig 1 ), occlusion of the left popliteal artery (Fig 2 ), and thrombi throughout the left tibial arteries without flow into the left foot (Fig 3 ). The patient received 100 U/kg of intravenous heparin. Mechanical thrombectomy of the anterior tibial and peroneal arteries with 2 mg of intraarterial tissue plasminogen activator laced into the popliteal and anterior tibial arteries was performed with an Indigo CAT5 catheter (Penumbra, Alameda, California). An overnight dual-level tissue plasminogen activator infusion was started at 0.5 mg/h each into a 10-cm MicroMewi infusion catheter (Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland) that was placed into the anterior tibial artery and a CAT5 catheter (Penumbra) in the popliteal artery. Intravenous heparin (500 U) was also administered through the sheath.

Figure 1.

Angiogram shows left distal profunda femoris artery branch occlusion.

Figure 2.

Angiogram shows left below-knee popliteal artery occlusion.

Figure 3.

Angiogram shows thrombi throughout the left tibial arteries without flow into the foot.

The patient showed clinical improvement overnight, without evidence of compartment syndrome. Follow-up angiography demonstrated residual thrombi in the anterior and posterior tibial arteries. The left peroneal artery had segmental occlusion and terminated just above the ankle (Fig 4 ). Vacuum-assisted thrombectomy of the anterior and posterior tibial arteries was performed with an Indigo CAT6 catheter (Penumbra), and patency was restored to the level of the ankle; flow into the foot remained minimal via small plantar vessels. Catheter-directed thrombolysis was continued with a 5-cm Uni-Fuse infusion catheter (AngioDynamics, Latham, New York) placed in the distal left popliteal artery at a rate of 0.75 mg/h. A repeat angiogram on the third hospital day demonstrated patent anterior and posterior tibial arteries with restored perfusion into the left foot (Fig 5 ). Catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy was discontinued.

Figure 4.

Follow-up angiography on the second hospital day shows residual distal left tibial occlusion and minimal flow into the foot.

Figure 5.

Final angiogram shows restored flow into the left foot.

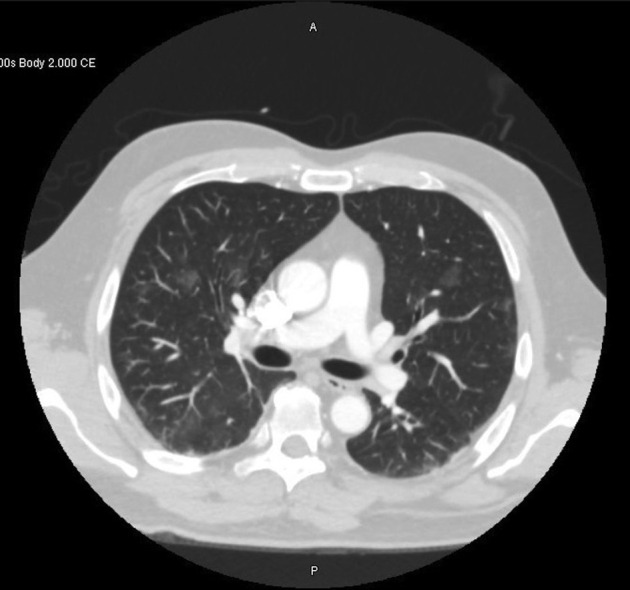

No source of embolus was discovered on an echocardiogram or computed tomographic (CT) angiography of the aorta. However, chest CT revealed scattered bilateral pulmonary ground-glass opacities (Fig 6 ). In-hospital SARS-CoV-2 testing was positive. A hypercoagulation panel was remarkable only for increased levels of anticardiolipin immunoglobulin M (39 phospholipid units per milliliter; normal range, 0–12) and immunoglobulin G (43 phospholipid units per milliliter; normal range, 0–14). Therapeutic intravenous heparin was continued during hospitalization. The patient was transitioned to oral anticoagulation and discharged on hospital day 6. At discharge, there was residual left foot swelling and superficial skin ischemia on the distal left first and fourth toes, in addition to palpable pedal pulses. The patient was able to bear weight on his left foot and subsequently returned to work 1 month later. Postintervention noninvasive vascular studies at 1 month demonstrated bilateral ankle-brachial indexes of 0.98, and there was no hemodynamically significant stenosis in either lower extremity.

Figure 6.

Chest CT demonstrates bilateral ground-glass opacities.

As the scientific community learns more about SARS-CoV-2, it is understood that the virus is capable of impacting multiple organ systems beyond its effect as a predominantly pulmonary pathogen. Although the data highlighting abnormal coagulation factors in patients with SARS-CoV-2 have mostly been obtained from critically ill patients (3), the case described here suggests that coagulopathy might exist in the absence of critical illness and may lead to large-vessel occlusion. The mechanism for SARS-CoV-2–induced coagulopathy is complex and likely has multiple contributing factors. Vascular endothelium is critical for maintaining vascular homeostasis. The virus acts on vascular endothelium via angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors, and there is evidence of direct virus infection of the vascular endothelial cells, resulting in diffuse endothelial inflammation and procoagulant state (4). Antiphospholipid antibodies may play a role (1). Published case reports of treatment of acute limb ischemia in patients with COVID-19 have been largely limited to an open surgical approach (2). Transluminal pharmacomechanical technique is an option in this vulnerable population. Anticoagulation appears to be associated with better prognosis in patients with severe COVID-19 with coagulopathy (2,4). How long inflammation and thrombotic derangements last after recovery from the symptoms of COVID-19 remains unclear. Therefore, extended posthospitalization anticoagulation with low molecular weight heparin or oral anticoagulant agents for 30 days to 6 weeks is currently empiric, and long-term treatment may be considered.

Various immunologic factors appear to contribute to the development of microvascular and macrovascular thromboses in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Although a direct link remains unclear, SARS-CoV-2 infection can present with acute limb ischemia, even in those who are not critically ill and have not had cardiovascular disease. In selected patients, this may be managed successfully with percutaneous transluminal intervention.

Footnotes

A.H.M.’s E-mail: annabella.maurera@sclhealth.org

None of the authors have identified a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Zhang Y., Xiao M., Zhang S. Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellosta R., Luzzani L., Natalini G. Acute limb ischemia in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. J Vasc Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.04.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sardu C., Gambardella J., Morelli M.B. Is COVID-19 an endothelial disease? Clinical and basic evidence. Preprints. 2020:2020040204. doi: 10.20944/preprints202004.0204.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]