Abstract

Purpose

Close to 100 genes cause retinitis pigmentosa, a Mendelian rare disease that affects 1 out of 4000 people worldwide. Mutations in the ceramide kinase-like gene (CERKL) are a prevalent cause of autosomal recessive cause retinitis pigmentosa and cone–rod dystrophy, but the functional role of this gene in the retina has yet to be fully determined. We aimed to generate a mouse model that resembles the phenotypic traits of patients carrying CERKL mutations to undertake functional studies and assay therapeutic approaches.

Methods

The Cerkl locus has been deleted (around 97 kb of genomic DNA) by gene editing using the CRISPR-Cas9 D10A nickase. Because the deletion of the Cerkl locus is lethal in mice in homozygosis, a double heterozygote mouse model with less than 10% residual Cerkl expression has been generated. The phenotypic alterations of the retina of this new model have been characterized at the morphological and electrophysiological levels.

Results

This CerklKD/KO model shows retinal degeneration, with a decreased number of cones and progressive photoreceptor loss, poorly stacked photoreceptor outer segment membranes, defective retinal pigment epithelium phagocytosis, and altered electrophysiological recordings in aged retinas.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first Cerkl mouse model to mimic many of the phenotypic traits, including the slow but progressive retinal degeneration, shown by human patients carrying CERKL mutations. This useful model will provide unprecedented insights into the retinal molecular pathways altered in these patients and will contribute to the design of effective treatments.

Keywords: CERKL, CRISPR, gene editing, retinitis pigmentosa, cone–rod dystrophy

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) (OMIM #268000) belongs to a group of heterogeneous inherited retinal dystrophies that affect 1 in 3000 to 5000 people worldwide1–3 RP, a highly clinically and genetically heterogeneous disease, is characterized by degeneration of photoreceptors, with alteration of rods in the early stages followed by cone death at later stages of the disease1 Mutations in CERKL cause non-syndromic autosomal recessive RP (OMIM #608380), although it has also been associated with autosomal recessive cone–rod dystrophy (CRD) (first alterations detected in cones and later in rods).4–8

CERKL shares more than 50% homology to CERK, a kinase that phosphorylates ceramide to ceramide 1-phosphate, a sphingolipid metabolite involved in proliferation, apoptosis, phagocytosis, and inflammation9–11; however, no kinase activity has been confirmed for CERKL thus far.12 CERKL shows a highly dynamic subcellular localization, as it can shift from nucleus to cytoplasm, and it has also been associated with Golgi vesicles and endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria membranes13,14 Previous results support its involvement in protecting cells against oxidative stress injury.13,15 CERKL is expressed not only in the retina but also in several adult and fetal tissues in human and mouse. In humans, the highest expression of CERKL is detected in the retina, some brain regions, lung, and kidney,4 whereas in the adult mouse, the highest levels of expression can be detected in the retina, liver, and testis.16

Attempts to generate a mouse model to both unveil the physiological function of CERKL and generate an RP model to study the progression of the retinal disorder have not been successful.17 A knockout (KO) murine model generated by deleting the proximal promoter and the first exon of CERKL using cre/loxP turned into a knockdown, due to the use of alternative promoters. The levels of sphingolipids were altered in the model,13 but no retinal morphological degeneration was detected except for electroretinographic alterations in the oscillatory potentials (OPs) of the retinal ganglion cell layer.18 It is plausible that the high transcriptional complexity of CERKL, which produces more than 20 transcript isoforms in humans and mice due to the combination of extensive alternative splicing and the use of additional promoters hampers the generation of a mouse model that mimics the human phenotype.16 Nonetheless, the morpholino knockdown of Cerkl in zebrafish embryos caused abnormal eye development, and the retina showed lamination defects, altered photoreceptor outer segments, and increased apoptosis, thus supporting the relevance of Cerkl for survival and protection of the retina.19 On the other hand, the study of the retinal neurodegeneration phenotype in morpholino-treated zebrafish embryos cannot be easily extrapolated to adult humans; therefore, the generation of a genetically amenable model to unveil the physiological role of CERKL and study the effect of associated mutations still remains a challenge.

In this work, we have generated the deletion of the whole Cerkl locus (approximately 100 kb) by gene editing using a CRISPR/Cas9 D10A nickase. Unexpectedly, the complete ablation of Cerkl in homozygosis resulted in embryonic/perinatal lethality in mouse. We have thus generated a new double heterozygote model in which the expression of Cerkl is reduced to less than 10% in the retina.

Materials and Methods

Animal Handling and Ethics Statement

Murine tissue samples were obtained from C57BL/6J and Albino B6(Cg)-Tyrc-2J/J (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) background mice at different ages. Animal handling was performed according to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, as well as the regulations of the animal care facilities at the University of Barcelona. All procedures were evaluated and approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of the University of Barcelona.

CerklKOKO Mouse Model Generation by CRISPR/Cas9 System

The CRISPR/Cas9 system was used to generate a CerklKOKO mouse model by deleting the whole Cerkl locus, approximately 97 kb. To minimize potential off-targets, we used the D10A Cas9 nickase (Addgene, Watertown, MA, USA). For the deletion, two guides per site were designed (a total of four) (Fig. 1) and injected in murine zygotes together with the endonuclease Cas9 D10A mRNA. To facilitate the generation of a recombinant deletion allele, single-stranded donor oligonucleotides (ssODNs) with the flanking sequence of the expected deleted allele were also microinjected. In our conditions, ssODNs appeared integrated in the target site in some alleles but did not enhance deletion, as none of the recovered alleles in the mosaic pups contained the precise designed allele. All embryonic procedures up to the generation of the founder mice were performed at the Mouse Mutant Core Facility, Institute for Research in Biomedicine (Barcelona, Spain).

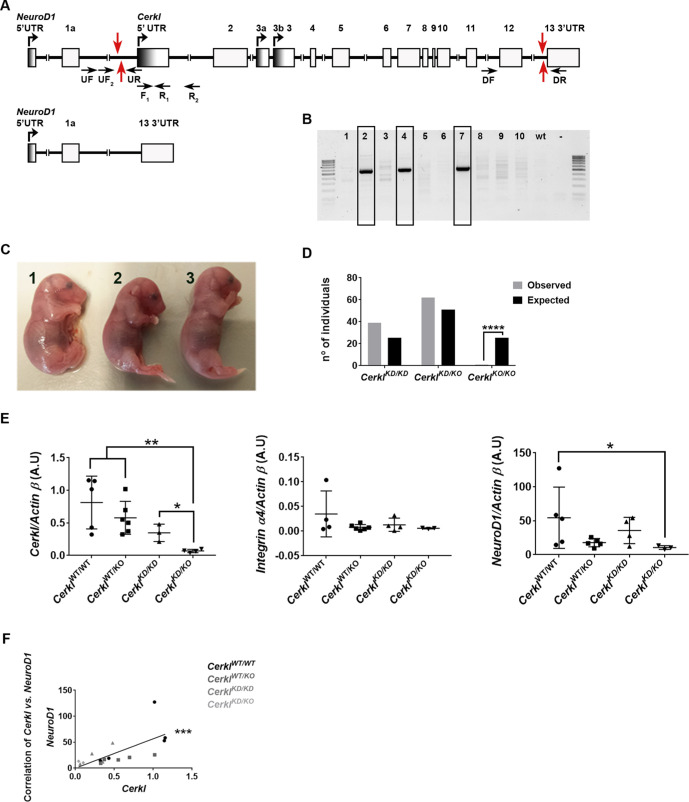

Figure 1.

Generation of a CerklKO/KO mouse model by CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. (A) Representation of the Cerkl locus with the position of exons and active promoters in the retina and of the targeting sequences for the four CRISPR gRNAs (red arrows). The resulting gene structure of the CRISPR-edited allele with full deletion from the proximal promoter to exon 13 is indicated below. Black arrows indicate the position of the primers used for genotyping. (B) PCR genotyping analysis (using forward primers [UF] and reverse primers [DR]) of the mosaic CerklKO pups obtained after CRISPR/Cas9 zygote microinjections. (C) Image of three E18 embryos showing the only homozygous CerklKO/KO mouse recovered (1) and the other two siblings, whose genotype was CerklKD/KO (2 and 3). No gross morphological alterations were observed. (D) Complete ablation of the Cerkl locus causes perinatal lethality in mice. Only one embryo (E18, shown in C) out of 102 mice (adding embryos and newborns) from matings between CerklKD/KO heterozygotes was a CerklKO/KO homozygote. P < 0.0001 (χ2 test) represents statistically significant differences between the expected results (25%) and the observed results (0.98%) for the CerklKO/KO genotype. The offspring of the matings were 1:2 instead of 1:2:1, thus supporting the lethality of the CerklKO/KO genotype. (E, F) Effect of the Cerkl knockout allele on the expression levels of genes in the same locus. Transcriptional levels of Cerkl, Integrin α4, and NeuroD1 (E) in the retinas of Cerkl CRISPR-ed P60 mice (n = 3–6), C57BL/6J mice strain. Levels were normalized against Actin B expression. Statistical significance is indicated with asterisks (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; Mann–Whitney test). Correlation analyses between the Cerkl and the NeuroD1 values (F) are also shown. Statistical significance, assessed by the Spearman correlation test, confirmed a strong correlation between the expression of Cerkl and NeuroD1 genes (***P < 0.001).

Mosaic pups were genotyped, and DNA samples from ear punches were screened by PCR using specific primers for detection of gene edited alleles (only at 5′ or 3′ sites, full deletion, inversion) (Table). PCR products were electrophoresed in high-resolution agarose gels, and gene edition was confirmed by Sanger sequencing. To confirm that the CRISPR/Cas9 technique did not introduce any off-target deletions or mutations, all of the potential off-target sequences determined by a prediction software (up to three mismatches with single guide RNA) were analyzed. PCR primers for potential off-target regions are listed in Supplementary Table S1. After discarding any off-target events or on-target chromosomal rearrangements (inversions/duplications), selected founder animals were crossed with wild-type black or albino animals in order to transmit the Cerkl allele bearing the 97 kb deletion to the offspring. Additional matings with a floxed CerklKD model18 were performed to obtain the heterozygote CerklKD/KO lineage in both the C57BL/6J and Albino B6 murine backgrounds.

Table.

Sequences of Primers Used in PCR Assays

| Name | Forward (5′→3′) | Assay | Name | Reverse (5′→3′) | Assay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerkl UF2 | GAAGCCCTGAAGGAGACAACTC | CRISPR/Cas9 | Cerkl UR | CTCTACCTGGATGCGACAGC | CRISPR/Cas9 |

| Cerkl DF | GAAAACCTGGGGCTATCTGGT | CRISPR/Cas9 | |||

| Cerkl UF | CAGGACAGTTCTGGAGTTGATG | CRISPR/Cas9 | Cerkl DR | GGGAGCAGGGCTAGAGAGTAT | CRISPR/Cas9 |

| Genotyping | Genotyping | ||||

| Cerkl F1 | ACACATTAGAAGCCCTGAAGGA | Genotyping | Cerkl R1 | TCTTTGTGCTGTAGCAGTGACC | Genotyping |

| Cerkl R2 | TTCTCCCGCTGTGATTGC | ||||

| Thy-1 F | TCTGAGTGGCAAAGGACCTTAGG | Genotyping | Thy-1 R | CGCTGAACTTGTGGCCGTTTACG | Genotyping |

| NeuroD1 Fw | AACAACAGGAAGTGGAAACATGACC | Real-time qPCR | NeuroD1 Rv | ACACTCATCTGTCCAGCTTGGG | Real-time qPCR |

| Integrin α4 Fw | CAGTGGAGAGCCTTGTGGGAA | Real-time qPCR | Integrin α4 Rv | GTGCCCACAAGTCACGATAGAGC | Real-time qPCR |

| Actin β Fw | GATGACCCAGATCATGTTTGAGACC | Real-time qPCR | Actin β Rv | CTCCGGAGTCCATCACAATGC | Real-time qPCR |

For arborization studies, selected matings between two strains, the transgenic Thy1-YFP-H mice (a kind gift from Ángel Carrión20) and CerklKD/KO mice (generated in this work), were performed to generate a new mouse line, CerklKD/KO/Thy1-YFP.

Genomic DNA and Genotyping by PCR

DNA for genotyping was extracted from ear punches from weaning mouse pups, following standard procedures. In brief, each sample was lysed in a mild lysis buffer and incubated overnight with proteinase K, and the nucleic acid was precipitated with ethanol. Primers for genotyping each strain are depicted in Figure 1 and listed in the Table. Three-step PCR conditions for amplification of genomic DNA were used for individual genotyping.

RNA Isolation and RT-qPCR

For each genotype, three to six independent animal samples were homogenized using a Polytron PT1200E homogenizer (Kinematica AG, Lucerne, Switzerland). Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), following the manufacturer's instructions with minor modifications (treatment with DNAse I during first hour). Reverse transcription reactions were carried out using the qScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Quanta BioSciences, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master and a LightCycler 480 Multiwell Plate 384 (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Penzberg, Germany) in a final reaction volume of 10 µL (primers are listed in the Table). Raw data were analyzed with the Advanced Relative Quantification method (LightCycler 480). The Mann–Whitney test was performed to assess statistical significance.

Cell Culture and Constructs

The coding region of hCERKL532 cDNA (NM_201548.4) and mCerkl525 cDNA were cloned into pcDNA3.1. Site-directed mutagenesis by inverse PCR was performed when coding mCerkl525 cDNA (NM_001048176.1) to generate constructs carrying the deletion of exon 2, exon 5, and exon 12 in frame. The constructs were transfected in HEK293 using Lipotransfectine (Niborlab, Guillena, Spain). Four hours after transfection, the medium was changed, and the cells were then harvested after 48 hours of growth for subsequent assays.

In-House Antibody Generation

We generated in-house anti-CERKL antibodies against specific mouse CERKL antigenic peptides—CERKL2 (peptide encoded in exon 2): CLKEQRNKLKDSTLDL; CERKL5 (peptide encoded in exon 5): CSEAARALLLRAQKNAGVE; and CERKL12 (peptide encoded in exon 12): CVDGDLMEAASEVHIR. Peptides were conjugated to the keyhole limpet hemocyanin carrier and subsequently injected into rabbits together with complete Freund's adjuvant or incomplete Freund's adjuvant adjuvants for antibody production. These antibodies were used for western blot, immunofluorescence, and immunoprecipitation assays. The specificity of the antibodies was tested using constructs with specific in-frame deletions spanning the immunogenic peptides.

Western Blot Immunodetection

Adult retinas and other tissue samples were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer consisting of 50-mM Tris (pH 7.4), 150-mM NaCl, 1-mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.25% Na-deoxycholate, and protease inhibitors. Transiently transfected HEK293 cells were lysed using 1× Laemmli buffer. Samples were electrophoresed in a sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) western blotting membrane (Roche Diagnostics), which was blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk and 5% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (Sigma-Aldrich). Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C followed by incubation with the corresponding secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature using standard procedures: rabbit αCERKL2 (1:1000, in-house), rabbit αCERKL5 (1:1000, in-house), mouse αGFAP (1:500; MAB8360, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA), mouse αGAPDH (1:1000; ab8245, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated α-mouse (1:2000; ab5706, Abcam), Rabbit IgG HRP Linked Whole Ab (1:2000, NA934VS; GE HealthCare, Chicago, IL, USA).

Immunohistochemistry on Mouse Retina Cryosections

Eyes from mice 2 to 18 months old were enucleated, fixed, and embedded as described elsewhere.21 Cryosections (12-µm section) were collected and kept frozen at –80°C until used. For immunohistochemistry (IHC), cryosections were air dried for 10 minutes and rehydrated with 1× PBS (3 × 5 minutes) and blocked in blocking solution (1× PBS containing 2% sheep serum and 0.3% Triton X-100 [Sigma-Aldrich]) for 1 hour at room temperature. Primary antibody incubation was performed overnight at 4°C. After three rinses with 1× PBS (10 minutes each), cryosections were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with the corresponding secondary antibodies conjugated to a fluorophore. Finally, the slides were washed with 1× PBS (3 × 10 minutes) and coverslipped with Fluoprep (BioMerieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France). The primary antibodies and dilutions used included rabbit αCERKL2 (1:200, in-house), rabbit αCERKL5 (1:100, in-house), mouse αRhodopsin (1:300, ab5417; Abcam), rabbit αL-/M-opsin (1:300, ab5405; MilliporeSigma), rabbit αS-opsin (1:300, ab5407; MilliporeSigma), 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1:1000, 10236276001; Sigma-Aldrich), mouse αGFAP (1:200, MAB8360; MilliporeSigma), PNA (1:50, L32460; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and mouse αTUJ-1 (1:1000, 801201; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA). Image visualization was performed using confocal microscopy and optical transmission microscopy utilizing the LSM 880 confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Jena, Germany) and Leica TCS-SP2 True Confocal Scanner (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), as well as high-resolution microscopy utilizing the Leica TCS SP5 STED CW.

Retinal Sections for Morphometrical Measurements and Transmission Electron Microscopy

Eyes from CerklKD/KO and CerklWT/WT mice (albino strain) were perforated using a needle, and the eyes were immersed in fixative solution (2.5% glutaraldehyde, 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1-M phosphate buffer) and incubated at 4°C overnight. They were then rinsed with buffer, post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide and 0.8% K4Fe(CN)6, and maintained in the dark for 2 hours at 4°C, followed by another rinse in double distilled water to remove the osmium. Eyes were dehydrated in increasing concentrations of acetone and then infiltrated and embedded in Epon (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA). Blocks were obtained after polymerization at 60°C for 48 hours. Semithin sections 1 µm thick were obtained using a Leica UC6 Ultramicrotome; they were dyed with 0.5% methylene blue and observed using a Leica DM200 microscope. Sections containing the optic nerve were photographed under a Leica MZFLIII fluorescence stereomicroscope and ZOE Fluorescent Cell Imager (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Fiji software (ImageJ; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to measure retinal layer thickness at 200-µm intervals.

For transmission electron microscope (TEM) imaging, ultrathin (60-nm) sections were obtained using a Leica UC6 Ultramicrotome. These sections were stained with 2% UranyLess (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and lead citrate and observed in a Jeol EM J1010 (Jeol Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Images were acquired at 80 kV with a 1000 × 1000 MegaView CCD camera (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions, Münster, Germany). For retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) phagosome/lysosome distribution analysis, the RPE cell was longitudinally divided in two halves (basal and apical), and the number of each vesicle type was counted per eye.

Retinal Whole Mount

For whole-mount retina staining, retinas from CerklWT/WT, CerklWT/KO, and CerklKD/KO mice (2–18 months old) were placed on glass slides photoreceptors side up, flattened by cutting the edges, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 hour at room temperature, and rinsed with 1× PBS (3 × 5 minutes). The retinas were then blocked in blocking solution (1× PBS containing 2% sheep serum and 0.3 % Triton X-100) for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated for 1 hour with Invitrogen Alexa Fluor 647 conjugate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) in blocking solution (1:50). Retinas were washed with 1× PBS (3 × 5 minutes), mounted with Fluoprep (BioMerieux), and photographed with a Leica TCS-SP2 confocal microscope. For arborization studies, retinas from 3-month-old CerklWT/WT/Thy1-YFP and CerklKD/KO/Thy1-YFP mice were placed on glass slides ganglion cells up, flattened by cutting the edges, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 hour at room temperature, rinsed with 1× PBS (3 × 10 minutes), and permeabilized in 1× PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes. Blocking was performed for 1 hour in 1% FBS (Roche Diagnostics) in PBS. Rabbit Anti-GFP Antibody (1:50, ab290; Abcam) was used overnight at 4°C to amplify the yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) signal. Retinal whole mounts were rinsed for 10 minutes in 3× PBS and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour with secondary antibody conjugated to Invitrogen Alexa Fluor 488 (1:100; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and DAPI. After three washes in 1× PBS (10 minutes), retinas were mounted with Mowiol (Sigma-Aldrich).

Primary Retinal Ganglion Cell Culture

For primary retinal ganglion cell (RGC) culture, coverslips were coated with poly-l-ornithine (Sigma-Aldrich). A drop of complete Invitrogen Neurobasal medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific), supplemented with 0.06% d-glucose, 0.0045% NaHCO3, 1-mM l-glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin) plus 10 µg/mL laminin (Roche Diagnostics), was added on coated coverslips. The cultures were incubated overnight at 37°C and washed three times with complete Neurobasal medium before cell culture. P0 mouse retinas were dissociated using the Neural Tissue Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions with minor modifications. Approximately 100,000 cells per well were seeded onto freshly prepared coverslips in 24-well plates. Neuronal supplements and factors were added: Invitrogen B-27 (1×; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 5-µM Forskolin (Sigma-Aldrich), 50-ng/mL human brain-derived neurotrophic factor (PeproTech, Rock Hill, NJ, USA), and 20-ng/mL rat ciliary neurotrophic factor (PeproTech). After 7 days of in vitro neuron differentiation, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes, washed three times with 1× PBS, and cryoprotected (30% glycerol, 25% ethylene glycol, and 0.1-M PBS) for further experiments.

In Vivo and In Vitro Arborization Studies

Image visualization was performed using a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope. The mouse retina has more than 30 distinct ganglion cell subtypes, which can be distinguished by their morphological and functional features.22,23 In vitro cultured mouse RGCs were recognized by their morphology and long axons after immunostaining for anti-beta III tubulin antibody (TUJ-1). For analysis of in vivo RGC morphology, YFP-positive RGCs from CerklWT/WT/Thy1-YFP and CerklKD/KO/Thy1-YFP mice were identified by the presence of an axon and the morphology of large-field RGCs.22 For arborization quantification, confocal images were analyzed using ImageJ software, and dendritic arbors of ganglion cells were traced on projected z-stacks using a Fiji NeuronJ plugin.

Electroretinograms

Eight Cerklwt/wt mice and eight CerklKD/KO mice were used for electroretinogram recordings. Dark-adapted animals were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of Ketalar (ketamine, 95 mg/kg; Parke-Davis, Wellington, New Zealand) and Rompun (xylazine, 5 mg/kg; Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany) in saline solution (NaCl 0.9%). Pupils were dilated with 1% tropicamide (Alcon Cusí S.A., El Masnou, Barcelona, Spain). A Burian–Allen corneal electrode (Hansen Ophthalmic Development, Coralville, IA, USA) was used to record ERGs from the right eye. An electrode was placed 1 to 2 mm from the cornea, and a drop of 2% METHOCEL (methylcellulose; DuPont, Bomlitz, Germany) was placed between the cornea and the electrode to ensure electrical conductivity. Animal handling was performed under dim red light (>640 nm), and mice were maintained for >5 minutes in absolute darkness before recording. Mouse temperature was maintained at 37°C with a water heating pad. Full-field flash ERG was performed with a Ganzfeld dome. The intensity of light stimuli was measured with a Mavo-Monitor USB photometer (Gossen, Nürenberg, Germany) at the level of the eye. At each light intensity, four to six consecutive recordings were averaged. The interflash interval in scotopic conditions ranged from 3 seconds for dim flashes up to 30 seconds for the highest intensity stimuli. Under photopic conditions, the interval between light flashes was fixed at 1 second. ERG signals were amplified and bands filtered between 0.3 and 1000 Hz with a CP511 AC amplifier (Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA, USA). Electrical signals were digitized at 2 kHz with Labchart Pro software and a PowerLab data acquisition device (AD Instruments, Chalgrove, UK). Bipolar recording was performed between the corneal electrode and a reference electrode located in the mouth, with a ground electrode located on the tail. The stimulation protocols were designed according to the International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision.24 Rod-mediated responses were recorded under dark adaptation using light flashes of 0.01 cd·s/m2. Mixed rod- and cone-mediated responses were recorded in response to light flashes of 3 cd·s/m2. Cone-mediated responses were obtained for light flashes of 3 cd·s/m2 on a rod-saturating background of 30 cd/m2. Oscillatory potentials were isolated using white flashes of 3 cd·s/m2 and bandpass filtered between 100 and 10,000 Hz. The amplitudes of the a-wave, b-waves, and OPs were measured offline,24 and results were averaged in both animal groups. The amplitudes of the ERG-recorded traces were measured by an observer blind to the animal genotype. ERG parameters recorded from Cerklwt/wt and CerklKD/KO animals of different ages were statistically analyzed by Student's t-test.

Results

CRISPR/Cas9 Deletion of the Cerkl Locus

To produce the deletion of the whole Cerkl locus (97 Kb) and minimize potential off-target effects, the gene-editing strategy selected relied on the use of the Cas9 D10A nickase, which requires four guides (gRNAs), two per site (see Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. S1 for guide RNA positions and details). This deletion extended from the proximal promoter to exon 12 but did not affect exon 13, which is also transcribed in the opposite direction as part of the Integrin-α4 3′ untranslated region. The mRNA encoding the Cas9 D10A nickase and the four gRNAs were injected into zygotes. Mosaic pups were genotyped by PCR to identify those carrying gene-edited alleles. Nearly 50% of the microinjected mice were genetically modified at the target gene, at either the 5′ or 3′ gRNA target sites. Six out of 46 mice (13%) carried the expected 97-kb deletion (Fig. 1B), which confirmed that large deletions could be generated with the same frequency as moderate deletions (less than 1 kb) with the Cas9 nickase. The microinjection of Cas9 mRNA instead of an expression plasmid restricted the action to the first zygote divisions, so that the number of alleles per mosaic was very low (mainly one modified allele, rarely two, plus the wild-type). Specific primer pairs were designed to check both the deletion of the full locus and the gene edition at any of the two cleavage sites (Table). When the specific band for the deletion or gene modification was identified, gene editing was confirmed by Sanger sequencing of the PCR bands (Supplementary Fig. S2). Our results showed that guides at 5′ were much more successful than guides at 3′, suggesting preferences in the endonuclease action probably by sequence context, secondary structure, or closeness between the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequences of the two guides. Each of the six Cerkl-deleted alleles showed different gene-edited sequences around the PAM sites (Supplementary Fig. S2). All of the mosaic animals carrying the full CerklKO allele were checked for off-target modifications (see Materials and Methods section) and/or chromosomal rearrangements in the Cerkl locus, but none was identified (data not shown).

Cerkl Complete Ablation Causes Embryonic/Perinatal Lethality

To generate the CerklKO/KO model, heterozygous mice were mated (in black and albino backgrounds). Unfortunately, after repeated attempts none of the live offspring mice was homozygous for the Cerkl deletion in any background. These unexpected results suggested that either the complete ablation of Cerkl expression or the deletion of nearly 100 kb of the Cerkl genomic locus was lethal. To test whether this lethality occurred during embryonic or perinatal stages, embryos (age E13–E18) from selected matings were genotyped. Only one out of 35 embryos was homozygous for the deletion, but no gross abnormalities could be observed in the CerklKO/KO embryo (Fig. 1C).

Because the full Cerkl knockout model was lethal, we resorted to generating a new animal model in which the expression of Cerkl was extremely reduced, the double heterozygote CerklKD/KO. CerklKD/KO mice carry the KO allele in trans with the knockdown allele CerklKD (generated previously18). Of note, the matings between CerklKD/KO double heterozygotes never produced a homozygote CerklKO/KO animal. Altogether, considering all the live mice (67) and embryos (35) obtained by these multiple crossings, only one E18 embryo out of 102 animals was a full knockout, which confirms the lethality of this CRISPR gene-edited allele in homozygosis (χ2 test, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1D). The work presented here relies on the CerklKD/KO mice as a model to study the retinal phenotype caused by Cerkl mutations.

Cerkl Expression in the CerklKD/KO Murine Retinas

The murine Cerkl gene maps at chromosome 2 between NeuroD1, which is transcribed in the same direction as Cerkl, and Itga4, which is transcribed in the opposite direction. The Cerkl locus is relatively large and may contain regulatory regions of the adjacent genes; therefore, Cerkl deletion might alter their expression. The expression of Cerkl and flanking genes was quantified in adult murine retinas CerklKD/KO (P60) by RT-qPCR and compared to other genotypes. On average, the expression levels of Cerkl in the retina were reduced to 71% in CerklWT/KO, 42% in CerklKD/KD (as reported previously18), and 8.5% in CerklKD/KO. This drastic decrease in Cerkl expression in our model was statistically significant in comparison to CerklWT/WT and any of the other genotypes (Fig. 1E), indicating that the double heterozygote could be used as a knockdown that barely expressed Cerkl. On the other hand, Itga4 was apparently expressed at very similar levels in the different Cerkl genotypes (Fig. 1E). In contrast, NeuroD1 expression was significantly reduced in CerklKD/KO retinas in comparison with those of CerklWT/WT (P < 0.05). NeuroD1 expression was lower in all the genotypes that carried one allele with the full deletion of Cerkl in heterozygosis (Fig. 1E) and was highly correlated with that of Cerkl in the different genotypes (Fig. 1F). These results may reflect the fact that Cerkl and NeuroD1 share the same promoter (the NeuroD1 promoter is an alternative promoter of Cerkl), but they may also indicate that the Cerkl locus contains regulatory sequences of NeuroD1.

CERKL Isoforms Are Differentially Expressed in the Murine Retina

Cerkl shows a high transcriptional complexity, having more than 20 transcripts and more than a dozen protein isoforms due to alternative splicing and the use of at least three different alternative promoters.16 To detect different CERKL isoforms, several in-house antibodies were generated against the mouse protein, and domains were selected that were not highly conserved between human and mouse sequences; anti-CERKL5 recognizes a peptide encoded in exon 5, whereas anti-CERKL2 recognizes a peptide encoded in exon 2. The specificity of the antibodies was tested against proteins encoded by CERKL constructs bearing deletions of the target peptide region of each antibody, and they showed specificity for the mouse but not the human CERKL protein (Fig. 2A). The antibodies were also tested using different mouse tissues, but the number and size of protein isoforms recognized by each antibody were difficult to assess due to the high number of protein isoforms produced by Cerkl (Fig. 2A).

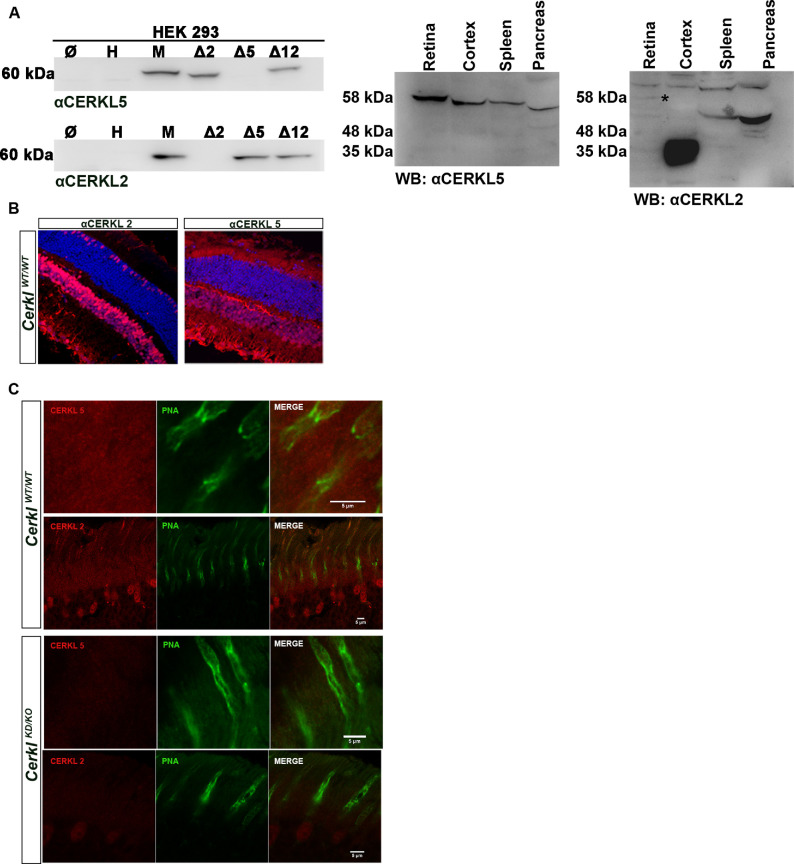

Figure 2.

CERKL immunolocalization in murine retina sections. (A) Western blot of HEK293 cells transfected with different Cerkl constructs bearing specific peptide deletions generated to test the specificity of the rabbit polyclonal antibodies generated in-house against two different peptides, one encoded in exon 2 (αCERKL2) and another encoded in exon 5 (αCERKL5). These exons are differentially spliced or expressed in CERKL transcript isoforms.16 The antibodies are specific for the murine CERKL protein (M) and do not recognize the human CERKL (H). The antibodies were also tested in different mouse tissues and detected bands of different sizes and intensities due to isoforms produced by multiple alternative splicing and alternative promoters. (B) CERKL isoforms are differentially expressed throughout retinal layers, as detected by αCERKL2 and/or αCERKL5. αCERKL2 detects isoforms that are mainly expressed in the nuclei of cones, inner nuclear layer (INL), and ganglion cell layer (GCL), whereas αCERKL5 detects isoforms highly expressed in rods, the outer plexiform layer (OPL), the INL, the plexiform layer (IPL), and the GCL. (C) High-resolution confocal microscopy confirmed the distribution of this preferential CERKL isoform in photoreceptors, as the isoforms detected by αCERKL2 were preferentially detected in cones (nuclei, inner and outer segments) and more weakly in rods, in contrast to the isoforms detected by αCERKL5, which are highly expressed in the inner and outer photoreceptor segments (both rods and cones) but undetectable in photoreceptor nuclei. Immunodetection of CERKL in the CerklKD/KO mice retinas was strongly decreased, as expected by the low remaining levels of CERKL expression (below 20% of the CerklWT/WT controls). CERKL is shown in red, peanut agglutinin (PNA) is shown in green; and nuclei counterstained with DAPI are shown in blue. All of the animals were C57BL/6J.

These antibodies were used for immunohistochemistry on retinal cryosections to observe the spatial pattern of CERKL in the retina. CERKL expression was detected in the ganglion cell, inner nuclear, and photoreceptor layers. Interestingly, when using anti-CERKL5, rods appeared more intensely labeled in contrast to the pattern detected with anti-CERKL2, which primarily labeled cones and their nuclei (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that different protein isoforms could be detected with antibodies against different domains. Using high-resolution confocal microscopy and focusing exclusively on the photoreceptor layer, we observed that the antibodies did not exclusively label rods or cones, but rather they recognized protein isoforms preferentially expressed in rods (anti-CERKL5) or cones (anti-CERKL2) (Fig. 2C, upper panel). These results indicate that distinct alternatively spliced isoforms carrying different protein domains are enriched in specific photoreceptor cell types. The specificity of these antibodies was validated on retinal cryosections of our CerklKD/KO model, in which we barely detected CERKL expression, thus confirming the results of transcript analysis (Fig. 2C, lower panel). CERKL was also highly expressed in the RPE, as detected by immunodetection with the two antibodies (Supplementary Fig. S3).

CerklKD/KO Retinas Show Photoreceptor Cell Layer Alterations with a Decreased Number of Cones

We hypothesized that the low expression of Cerkl in our mouse model might mimic the effect of CERKL mutations in human patients. In humans, mutations in CERKL cause both RP and CRD, and the phenotypic traits are usually reported in late teens or young adults. Therefore, we surmised that the age of around 1 year was an appropriate time frame to detect retinal alterations solely due to the depletion in Cerkl expression and before age-related neurodegeneration might blur the genetic effect.

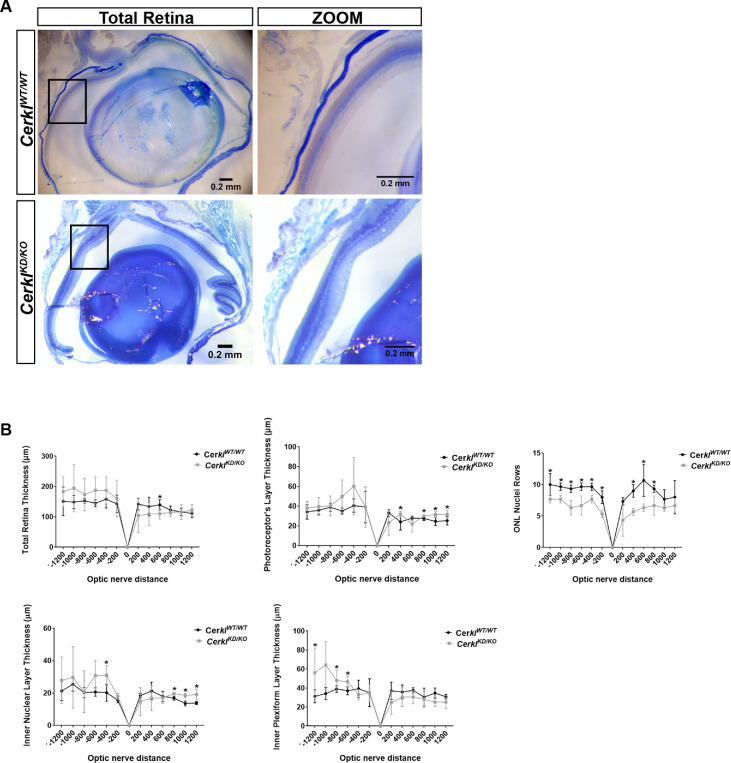

As a first approach, a comparative morphometric analysis of retinal morphology and layer structure between retinas from CerklKD/KO and CerklWT/WT mice was performed (Fig. 3). Regional differences in retinal thickness were clearly observed in the CerklKD/KO retinas, which displayed a wavy outer nuclear layer, with zones with fewer nuclei and others with an increased number of nuclei compared to the wild-type counterparts (Fig. 3A, zoom magnification). Consistent observations showed that, in the whole retina, half of them seemed thicker (with enlargement of the inner nuclear and plexiform layers) and the other half of them appeared thinner in the CerklKD/KO retinas (Fig. 3B, upper left panel). The most relevant observation was the consistent and significant decrease in the number of nuclei rows in the outer nuclear layer of the CerklKD/KO mice detected on both sides of the retina. Notably, the number of photoreceptor nuclei rows was statistically significantly decreased along the whole retina of the CerklKD/KO, which is a hallmark of severe retinal degeneration (Fig. 3B, upper right panel). The CerklKD/KO mice retina in comparison with the CerklWT/WT exhibited irregular thickness along the retina, severe layer organization defects, and a decreased number of photoreceptor nuclei.

Figure 3.

Retinal morphometric measures of CerklKD/KO and CerklWT/WT mice. (A) Stereo microscope representative images of CerklKD/KO and CerklWT/WT mouse retinas (semi-thin sections of epoxy-embedded eyes of 1-year-old mice) used for morphometry (n = 3 per group). (B) The thickness of each retinal layer along the retina was measured at every 200 µm from the optic nerve, which was set up as point 0. Differences in retinal layer thickness were detectable in CerklKD/KO retinas compared to controls. Statistically significant differences are indicated with asterisks (*P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney test). Scale bar: 200 nm (black). Control and mutant animals were from an albino B6(Cg)-Tyrc-2J/J strain background.

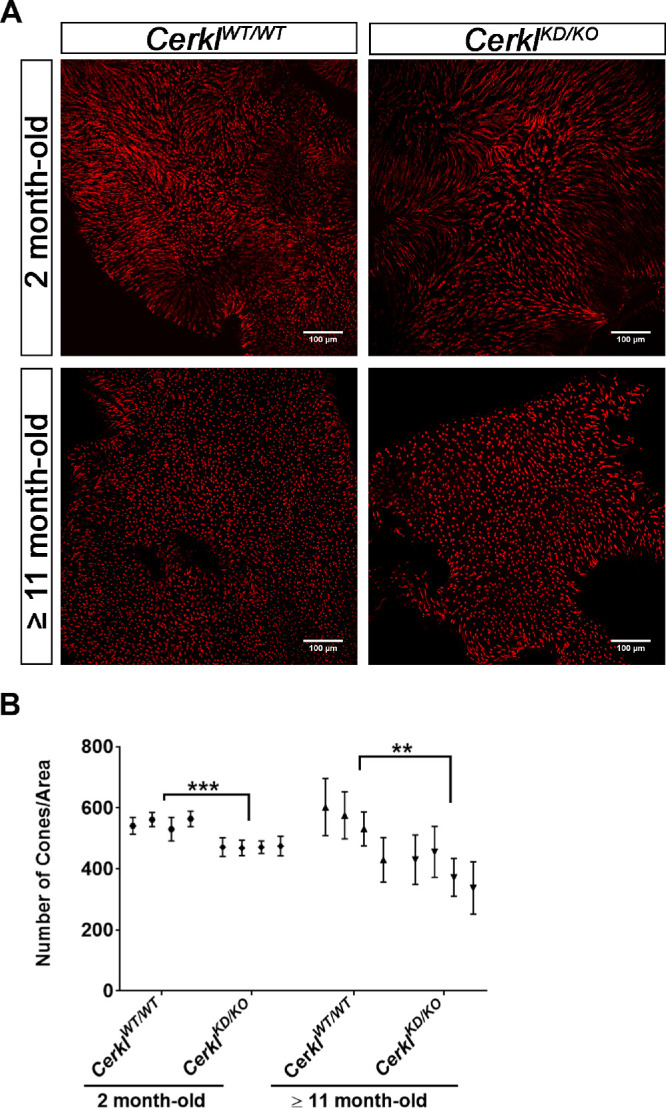

These results prompted us to determine whether rods or cones were most affected in the CerklKD/KO mouse model. To study whether the decrease in the number of nuclei was progressive, the retinas of young mice (2 months old) and older mice (≥11 months old) were compared. The attrition of cone photoreceptors was evaluated by whole mounts of retinas stained with PNA to visualize and quantify the number of cones (see Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. S4). The number of cones in old CerklKD/KO mice (11–18 months of age, or ≥11 months old) was notably diminished in comparison to CerklWT/WT (Fig. 4). This decrease in the number of cones is statistically significant, and it was also detected in younger mice (2 months) when the values obtained within each genotype are more robust and compact. With age, the number of cones was more variable in both genotypes, but, as mentioned, the decrease was more apparent in the CerklKD/KO retinas. Therefore, the depletion of Cerkl expression caused an early-onset decrease in the number of cones, as detected in both young and old animals.

Figure 4.

Cone count in whole mount retinas. (A) Murine retinas of CerklWT/WT and CerklKD/KO mice (n = 4) at 2 months and ≥11 months of age were flattened, fixed, and stained with PNA conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 (red). The number of cones was counted by positioning three regions of interest (ROIs; area 164.79 µm2) in different parts of the image and summing the cones of each ROI. For each retina we analyzed 10 to 12 images in order to cover the whole retina. (B) Statistical significance showed differences among genotypes by two-way ANOVA test (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). Scale bar: 100 µm (white). All of the animals were C57BL/6J.

Of note, and as an external ocular phenotype, the lens of old but not of young animals presented non-uniform calcified cataracts, which were not present in the wild-type animals (Supplementary Fig. S5). Although it does not occur often, some human patients bearing CERKL mutations have been reported to develop posterior subcapsular cataracts, very similar to those observed in our model.25,26

Alteration of Rod and Cone Photoreceptor Outer Segments in CerklKD/KO Retinas

We next focused on the photoreceptor morphology and structure by performing immunohistochemistry on retinal cryosections from the CerklKD/KO model in young mice (2 months old) and older mice (11–18 months old). The dorsal and ventral regions in retinal cryosections can be distinguished because in the C57BL/6J strain the distribution of short-wavelength-sensitive opsin (S-opsin) and medium-/long-wavelength-sensitive opsin (M-/L-opsin) cones are distributed in opposing gradients, as S-opsin cones are more concentrated in the ventral region and M-/L-opsin cones are more concentrated in the dorsal retina27,28 (blue and red gradient lines in the scheme at the top of Fig. 5 indicate the opposing gradient of M-/L- and S-opsin cones, respectively).

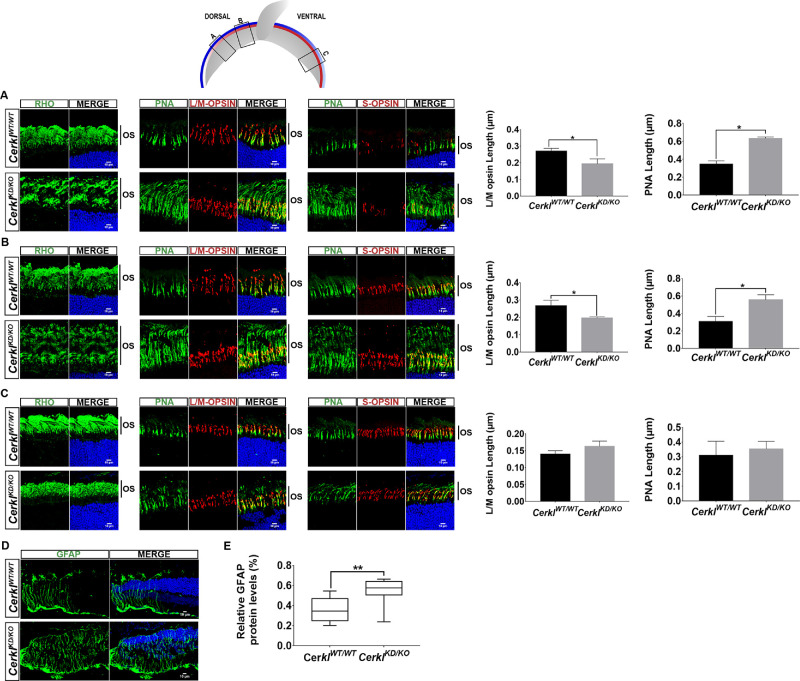

Figure 5.

Alteration of photoreceptor OS length in CerklKD/KO mice. The scheme at the top shows the position of the images in the dorsal and ventral retina. The M-/L-opsin (blue line) and S-opsin (red line) cones were distributed in an opposing gradient. (A–C) Immunodetection of rhodopsin (green), M-/L-opsin, and S-opsin (each in red) in retinal cryosections at the optic nerve level of CerklKD/KO versus the CerklWT/WT mouse retinas showed a notable enlargement of the photoreceptor layer due to elongation of the rod OSs and cone sheaths (stained by PNA), as indicated by vertical bars. This OS elongation in CerklKD/KO mice showed a consistent gradient distribution along the retina, being much more prominent at different locations of the dorsal retina (low number of S-opsin cones and high number of M-opsin cones) as shown in A and B, slowly decreasing to normal OS length in the ventral retina (higher number of S-opsin cones and lower number of M-cones) in C. Images are representative of three different animals (2 months old). Quantification of cone sheath length (PNA) and M-/L-opsin localization in regions A and B show an elongation of the sheath and a shorter opsin-functional outer segment in CerklKD/KO compared to CerklWT/WT, suggesting opsin mislocalization in dorsal but not in ventral retina (*P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney test). (D) Increased levels of GFAP (in green) were detected in retinal cryosections comparing CerklWT/WT and CerklKD/KO mice and are indicative of macrogliosis. (E) The GFAP increase in the CerklKD/KO mouse retinas compared to CerklWT/WT was quantified by western immunodetection and showed statistical significance (n = 8 per group; P < 0.01, Student's t-test). In all images, nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (in blue). Scale bar: 10 µm (white). All of the animals were C57BL/6J.

After immunodetection of rods (rhodopsin) and cones (S-opsin, M-opsin, and PNA, which stains all cone types), CerklKD/KO retinas showed statistically significant longer rod outer segments (OSs) and cone sheaths along the dorsal retina of the retina, doubling the length of those in CerklWTTWT (Figs. 5A, 5B; black bars at the side, 2-month-old mice). Also, in these regions, S-opsin and M-opsin proteins are detected up to the middle of the cone sheath compared to what is observed in the CerklWT/WT retinas (Fig. 5, quantification panels at the right). In contrast, the length of rod OSs and cone sheaths and the distribution of cone opsins gradually return to values similar to those of controls in the S cone-rich ventral retina (Fig. 5C). These results were also consistent in aged retinas (data not shown).

A trait of retinal neurodegeneration is retinal gliosis, which indicates a glial response to retinal dysfunction. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) is considered a macroglia marker. The CerklKD/KO retinas showed a marked and statistical increase in GFAP expression, thus indicating reactive gliosis due to retinal stress (Figs. 5D, 5E).

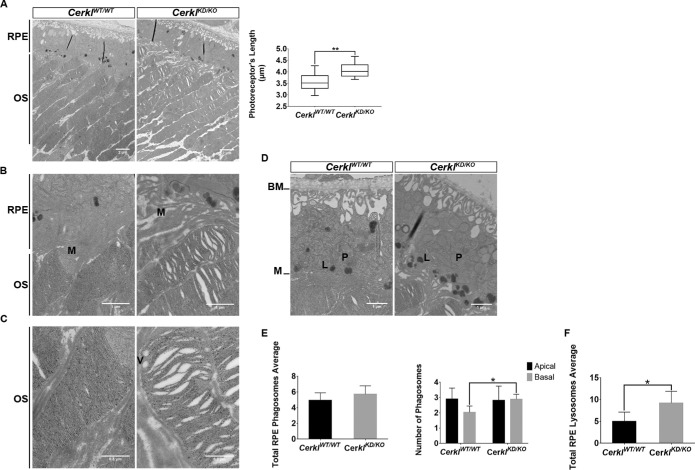

Stacking Defects of the Photoreceptor Membraneous Disks in the CerklKD/KO

The ultrastructural alterations of the photoreceptor layer in this model were analyzed by transmission electron microscopy in old animals (Fig. 6). In wild-type retinas, photoreceptor OSs were ordered in parallel and packed with closely stacked membraneous disks (where photoreception and phototransduction occur). However, CerklKD/KO photoreceptors displayed disordered and loosely stacked disks, and the OSs appear disarrayed (Figs. 6A, 6B; additional images in Supplementary Fig. S6). Quantification of photoreceptor OS length confirmed that the CerklKD/KO photoreceptors were significantly longer than those of the controls (Fig. 6A, right panel), in agreement with what we observed in the confocal IHC images (Fig. 5). Moreover, photoreceptor OSs in CerklKD/KO showed double membrane vesicles (indicated with a V in Fig. 6C) that disrupted the stacking of disks.

Figure 6.

CerklKD/KO retinas showed defects in the photoreceptor outer segments and alterations in RPE-mediated phagocytosis. Retinas of CerklKD/KO compared to CerklWT/WT mice (all albino B6(Cg)-Tyrc-2J/J mice) showed clear defects on photoreceptor OSs as revealed by TEM at increasing magnifications (5000×, 20000×, and 40000×): (A) The membraneous disks of CerklKD/KO photoreceptor OSs were loosely stacked and showed vacuoles in between disks compared to the compact disk staking in control retinas. Quantification of the photoreceptor OS length showed significantly longer OSs in CerklKD/KO photoreceptors compared to those of CerklWT/WT mice (**P < 0.01, Student's t-test), with three measures per animal (n = 3) per genotype. (B) Microvilli (indicated by M) from CerklKD/KO mice RPE appeared disorganized instead of closely wrapped around the photoreceptor tips as observed in CerklWTWT RPE. (C) High magnification of the photoreceptor OS tips focusing on the disk disorganization in CerklKD/KO compared to CerklWTWT. Double membrane vesicles (V) disrupt the membrane disk stacking in CerklKD/KO OSs. Scale bars: 2 µm, 1 µm, and 0.5 µm, respectively. TEM high magnification of CerklKD/KO and CerklWTWT retinas was performed to analyze the number and distribution of phagosomes and lysosomes within RPE cells: (D) Representative RPE images of CerklKD/KO and CerklWTWT for analyzing phagosomes (P) and lysosomes (L). Microvilli (M) formed at the apical region, whereas Bruch’s membrane (BM) indicates the basal region. (E) The total number of phagosome/endosome vesicles did not differ significantly (left), but a higher number of vesicles was observed in the RPE basal versus apical region in CerklKD/KO compared to controls (right). (F) The total number of lysosomes also increased in the RPE cells of CerklKD/KO (*P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney test). There were 15 representative images per retina and three animals per group. Scale bar: 1 µm. All animals were from an albino B6(Cg)-Tyrc-2J/J mice strain.

By increasing the magnification, were also able to study the RPE morphology. RPE performs the daily shedding of the photoreceptor OS tips by phagocytosis. A possible explanation for the extreme length of photoreceptor OSs observed in CerklKD/KO retinas could be alteration of RPE phagocytosis. This hypothesis is in agreement with the highly disorganized microvilli observed in this model compared to control retinas (indicated with an M in Fig. 6B). In this context, it is worth remarking that Cerkl was highly expressed in the RPE (Supplementary Fig. S3). We observed that microvilli from control retinas surrounded the tip of photoreceptor OSs, whereas CerklKD/KO microvilli were disarrayed and did not wrap the OS tips, thus pointing to defective phagocytosis. Within the RPE cell, trafficking of the phagosome vesicles until fusion with lysosomes was observed. Early and late phagosome vesicles could be distinguished from lysosomes by the density and color of the captured material. We performed TEM imaging in albino strains, the RPE of which does not have pigment in the melanosomes, and studied the number and distribution of apical and basal phagosomes/endosomes, as well as lysosomes in old mouse RPEs (Fig. 6D). Although the number of total phagosomes did not differ significantly between CerklKD/KO and control retinas of the same age (Fig. 6E, left), their distribution was altered, and the number of basal endosomes was statistically significantly increased in the CerklKD/KO model Fig. 6E, right). The total number of lysosomes is also altered between the two groups of animals and increases close to twofold in the RPE CerklKD/KO (Fig. 6F).

In summary, CerklKD/KO mouse retinas showed (1) disarrayed photoreceptor segments, with disorganized and loosely stacked disks; (2) defects in retinal pigment epithelium microvilli; (3) round vesicles within photoreceptor OSs; and (4) increased numbers of basal phagosomes/endosomes and total lysosomes in the RPE compared to CerklWT/WT, all of which are highly indicative of retinal dysfunction and vision impairment.

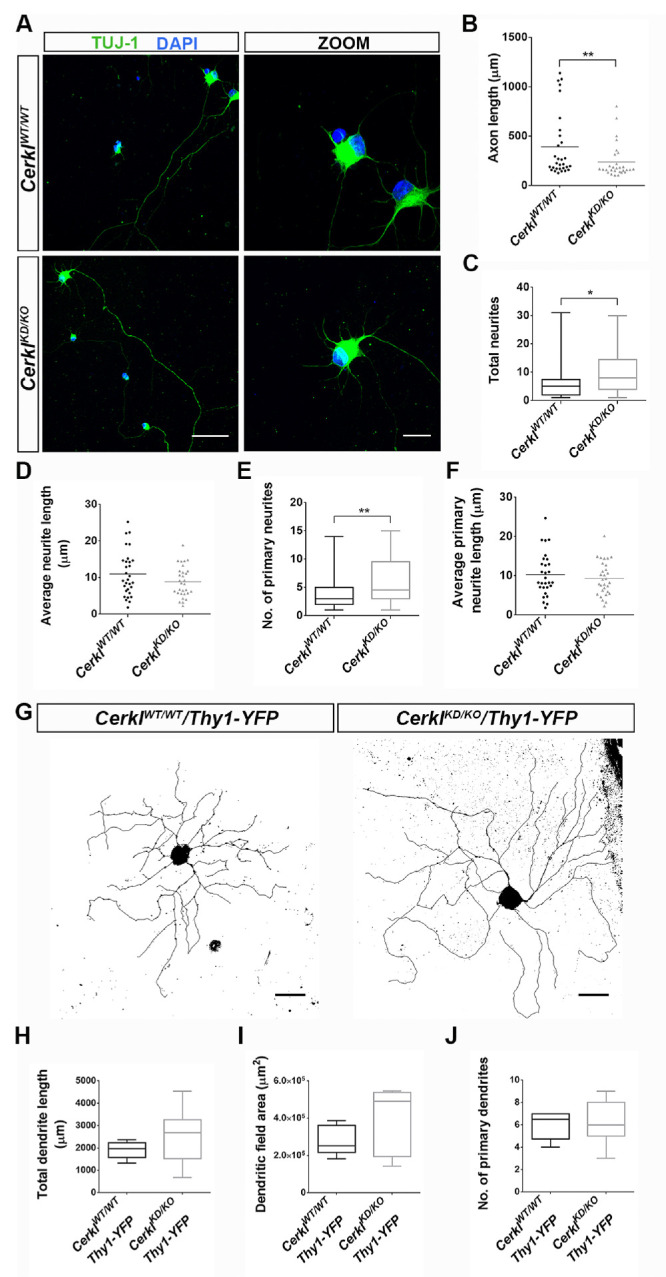

In Vitro and In Vivo Studies of Neurite Arborization in CerklKD/KO in RGCs

In the previous knockdown CerklKDKD mouse model, the retina showed no clear phenotype except for mild, although consistent and statistically significant, electrophysiological alterations in the OPs of RGCs. Because the double heterozygote CerklKD/KO shows a lower level of Cerkl expression (less than 10% compared to controls), RGCs might be even more affected at the morphological and functional levels. To analyze the RGC population phenotypic traits, we dissected retinas and cultured primary RGCs (P0, P1) for longer than 1 week in vitro. After 1 week, the ganglion cells spread neurites, dendrites, and axon, which could be distinguished and analyzed (Fig. 7A). Notably, the axons of the CerklKD/KO RGCs were shorter than those of control RGCs (Fig. 7B). Also, the total number of neurites was statistically significantly higher (Fig. 7C), but the average length appeared to be shorter (Fig. 7D). In fact, the number of primary neurites increased, although their length was not different (Fig. 7E). In summary, in vitro RGC primary cultures of CerklKD/KO showed differences in the arborization response and displayed shorter axons and increased numbers of neurites, although the length of the dendritic projections remained unaltered.

Figure 7.

Differences in neurite arborization between CerklKD/KO and CerklWT/WT RGCs. In vitro RGC neurite arborization after 1 week of primary cell culture of P0 retinas. (A) Representative confocal images of primary RGCs from CerklWTWT and CerklKD/KO mice. TUJ-1-labeled neuronal cells (green) and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars: 50 µm; 15 µm in high-magnification micrographs. (B) Axon length quantification showed that axons were significantly shorter in CerklKD/KO RGCs compared to those in CerklWT/WT. Analysis of total RGC neurites showed that, although the total number was slightly higher in CerklKD/KO compared to CerklWT/WT mice (C), their average length was very similar between the two genotypes (D). Analysis of primary RGC neurites pointed to slight significant differences in the number (E) but not in their average length (F) between genotypes. Results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = total of 30 neurons from 4–6 animals per group). In vivo RGC neurite arborization: (G) Dendritic arborization of retinal ganglion cells in vivo in CerklWT/WT/Thy1-YFP and CerklKD/KO/Thy1-YFP transgenic mice. Projected z-stacks of YFP-labeled large-field ganglion cells in CerklWT/WT/Thy1-YFP and CerklKD/KO/Thy1-YFP adult mice. Scale bar: 100 µm. No significant differences were found between genotypes when measuring in vivo total dendritic length (H), dendritic field area (I), or number of primary dendrites (J). Results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 6–7 neurons from 3–5 animals). Statistical analyses were performed by either Student's t-test (C–F) or Mann–Whitney test (B, H–J), depending on whether or not they adjusted to normality (*P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01).

For the in vivo analysis of RGC arborization, we used a Thy1-YFP-H transgenic line in which the YFP transgene is controlled by the Thy-1 promoter and expressed in a small fraction of RGCs.20 We analyzed the dendritic morphology of large field ganglion cells (see Materials and Methods section) in flat whole-mount retinas from CerklKD/KO/Thy1-YFP adult mice compared to CerklWT/WT/Thy1-YFP controls (Fig. 7G). The area of the dendritic field was determined as the area of a polygon obtained by joining the distal dendritic extremities. RGC dendrites were traced to determine the total dendritic length and the number of primary dendrites. In contrast to the in vitro results, no clear mophological differences were apparent between RGCs from CerklWT/WT/Thy1-YFP or CerklKD/KO/Thy1-YFP retinas, not in total dendrite length, dendritic field area, or number of primary dendrites (Figs. 7H–7J), pointing to a differential response to the stress of dissection and culture more than to an intrinsic trait.

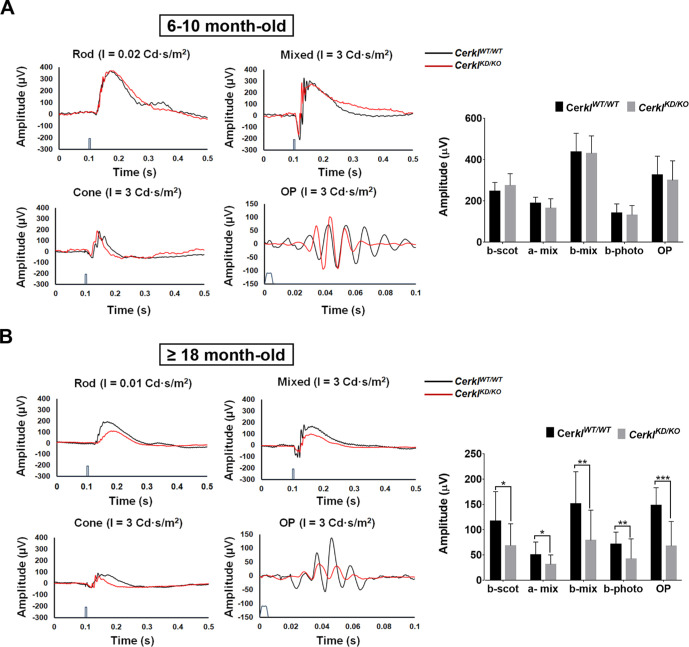

Retinal Electrophysiology of the CerklKD/KO Mice

In the previous knockdown CerklKD/KD mouse model, neither ERGs nor retinal morphology showed any clear retinal neurodegeneration phenotype, except for alterations in the OPs. This phenotype remained consistent and was not progressive with age. We surmised that this new model, with a lower expression of Cerkl, might show some retinal neurodegeneration detectable by ERGs. In young-adult mice (6–10 months old), we did not observe significant changes in any of the ERG measurements in comparison with wild-type animals (Fig. 8A). Because RP in humans is characterized by the progressive loss of photoreceptors, we deemed it reasonable to study the same cohort of animals (the two groups of animals) at older ages. Retinal degeneration is clearly observed in 18-month-old CerklKD/KO mice compared to CerklWT/WT mice (Fig. 8B). Rod (b-scot) and cone (b-phot) activity was statistically significant diminished, particularly in cones. These alterations were also reflected in postsynaptic photoreceptor activity (b-mix). In agreement with the previous mouse model, the OP responses, mostly contributed by the electrical activity of RGCs and amacrine cells, were the recordings affected most. Taking the morphometric and retinal morphology studies together with the ERGs, the CerklKD/KO retinas showed clear phenotypic structural alterations from a young age, but the electrophysiological response was not affected initially. However, with time, the abrogation of Cerkl expression caused progressive retinal dysfunction and vision impairment, similar to what occurs in humans carrying mutations in the CERKL gene.

Figure 8.

Electrophysiological recordings) of CerklKD/KO show progressive neurodegeneration and functional alteration of both rods and cones in aged mice. Figure shows representative ERG recordings obtained from one CerklWTWT animal (black traces) and one CerklKD/KO animal (red traces), and histogram representation of the averaged ERG wave amplitude for the two animal groups. (A) ERG measurements in young CerklKD/KO mice (6–10 months) show no clear alteration in either photoreceptor function in scotopic (rods) and photopic (cones) conditions or post-synaptic activity compared to age-matched controls (n = 6–8 animals per group). (B) In contrast, after aging (≥18 months), the same cohort of animals shows scotopic (b-scot) and photopic (b-photo) alterations in CerklKD/KO retinas, with a clear decrease in photoreceptor activity (a-mix, considering both rod and cone activity). This decrease was also observed in postsynaptic activity (b-mix) and was particularly evident in OPs, reflecting the synaptic activity of RGC and amacrine cells, overall indicating a progressive functional impairment of the retina in CerklKD/KO mice. The timing of stimulus application is shown on the time scale (for light stimuli details, see the Materials and Methods section). Bars represent data (mean ± SD) for b-scot, a-mix, b-mix, b-phot, and OP from CerklWTWT and CerklKD/KO mice. Statistical significant differences (one-tailed Student's t-test) are indicated above the histogram bars (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). All of the recordings were obtained from the C57BL/6J mice strain.

Discussion

Previous attempts to generate animal models to unveil CERKL physiological function have been hampered by the high transcriptional complexity of CERKL.16–19 Our first mouse model retained the expression of several Cerkl isoforms (40% of Cerkl expression) and did not show any severe retinal disorder except for a mild RGC alteration.18 CERKL is one of the most prevalent genes in the Spanish cohort of patients affected with autosomal recessive RP or CRD (5% prevalence).26 Because no other mouse model of retinal degeneration was available for this gene, we generated a novel Cerkl knockout mouse model by CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. Unfortunately, the complete ablation of Cerkl is not viable in homozygosis; therefore, we generated the double heterozygote CerklKD/KO, which retains less than 10% of Cerkl expression and thus provides a valuable model of slow retinal degeneration (physiological alterations are observed in mice at 18 months of age but not at 6–10 months), which mimics the relatively late-onset (second decade of life) but progressive degenerative disease observed in most patients bearing CERKL mutations.

The lethality of complete Cerkl ablation could be explained either by CERKL function being directly required for organism viability or by the presence of relevant regulatory elements for nearby genes embedded in the Cerkl locus. Cerk is rather ubiquitously expressed, including many vital organs,4,16 so lethality due to full Cerkl abrogation cannot be discarded. On the other hand, several cis-regulatory elements (enhancer sequences) have been functionally described within the CERKL locus in human cell lines (descriptions available at https://www.genecards.org/ and https://genome.ucsc.edu/) and appear to be physically associated with both CERKL and the upstream NEUROD1 gene promoters. The evolutionary conservation of these super-enhancers in vertebrate genomes supports their functional relevance. NeuroD1 is a neural and pancreatic transcription factor implicated in cell-cycle regulation, retinal cell genesis, and neuronal development,29,30 and NeuroD1 null mice die within a few days after birth due to severe diabetes.31 Because we have observed that the deletion of Cerkl significantly decreases the expression of NeuroD1, a plausible explanation for the lethality caused by the homozygous Cerkl deletion may be caused by both the direct loss of Cerkl expression in vital organs, such as liver or lungs, and the very low expression of NeuroD1 caused by the deletion of its enhancers. Further evidence should be gathered to understand the causes of the lethality associated with Cerkl locus deletion. It is worth noting that the most common CERKL mutation in humans (found in homozygosis and most often in double heterozygosis with other rarer mutations), c.847C>T (p.R283*),4 is not a complete null allele, as the mutation introduces a stop codon in exon 5, an exon that is included in some but not all isoforms due to alternative splicing.16

The high transcriptional complexity of Cerkl in the retina suggested preferential isoform expression in different neuron cell types. This is why we generated in-house antibodies, CERKL2 and CERKL5, against peptides encoded in different exons that recognize a different subset of CERKL isoforms. Immunohistochemistry of mouse retinal cryosections and high-resolution microscopy showed that isoforms containing exon 2 were preferentially expressed in cones, whereas those containing exon 5 were expressed more in rods, thus supporting the suggestion that different CERKL isoforms are preferentially expressed in rods versus cones and also lending credence to a differential function for the multiple isoforms. Further work on the effect of reported mutations on the function of different CERKL isoforms may explain why in some patients the phenotypic traits are clinically associated with RP or CRD, which differ in whether rods (peripheral retina) or cones (macula) are first affected, respectively (see Supplementary Table S2 for a complete list of CERKL mutations and reported retinal phenotypes in human patients). However, genotype–phenotype correlation in human patients may be particularly difficult for CERKL, as the same pathogenic mutation in homozygosis can cause either autosomal recessive RP with high macular affectation25 or autosomal recessive CRD,7,32 not only in different families but also in sibling patients within the same family,33 the main conclusion being that CERKL function is relevant for both types of photoreceptors. Also, the severity of retinopathy and visual loss in humans differ even in homozygous patients of the same family. Overall, it is tempting to speculate that both the type of mutation and the CERKL isoform affected, as well as additional mutations of modifier genes in each patient, might eventually determine which type of photoreceptors is initially more vulnerable to CERKL dysfunction; yet, after photoreceptor apoptosis is initiated, the disease progresses until all photoreceptors and eventually, all the retina—including inner cells—is affected. In this context, mice do not have a macula, but our mouse model is more similar to the CRD phenotype, as we will discuss below.

Concerning the retinal phenotype in this CerklKD/KO mouse model, we observed an extreme elongation of rod OSs and cone sheaths, as well as opsin mislocalization in cone OSs, at an early age (retinas 2 months old) following a dorsal to ventral longitudinal gradient in the retina, thus indicating an as-yet unknown Cerkl role in photoreceptor patterning. Furthermore, these very low levels of Cerkl expression can lead to photoreceptor OS disorganization, severe disk stacking alteration, and vesicle accumulation. All of these features could be explained by RPE phagocytosis dysfunction. In this context, a very recent report also associated suppression of Cerkl expression to defects in autophagy/macrophagy.34 It is worth noting that aged CerklKD/KO retinas (18 months old) display disarrayed RPE microvilli unable to engulf OS tips. In fact, the CerklKD/KO RPE shows high microvilli disorganization, phagosome accumulation in the basal membrane, and an increased number of total lysosomes, in full agreement with the results reported in a zebrafish Cerkl knockout model,35 overall suggesting a novel retinal role for CERKL in the regulation of vesicle formation, autophagy, and OS phagocytosis.

Another morphological defect observed in the CerklKD/KO mouse retinas is the difference in retinal thickness, probably due to the contribution of several traits: differential decrease in the number of nuclei rows, different thickness of the inner plexiform layer, and regional differences in the length of the photoreceptor OSs in an inverted gradient to S-opsin cone distribution. This is related to a slow but progressive neurodegeneration in aged CerklKD/KO retinas, as demonstrated by the progressive loss of cones and a clear decrease in the number of photoreceptor nuclei over time. Remarkably, similar traits are observed in human patients bearing CERKL mutations in advanced disease stages, with thinning of the fovea (extremely rich in cones) with loss of the outer nuclear layer or abnormal lamination, as visualized by careful optic coherence tomography imaging.7,25,30 The drastic reduction of Cerkl expression impinges on retinal homeostasis; consequently, GFAP expression by retinal astrocytes and Müller cells appear to be increased in CerklKD/KO, which is similar to findings in mouse models for retinitis pigmentosa and other inherited retinal diseases.28,36

To sum up, we generated a new Cerkl mouse model retaining less than 10% of Cerkl expression that mimics human CRD traits due to early cone loss and subsequent progressive degeneration of all photoreceptors. With age, our mouse model shows decreased number of cones, loss of photoreceptor nuclei, elongated OSs with mislocalized opsins, alterations in the RPE microvilli and phagocytosis, and stress-associated alterations (such as increased GFAP expression). These morphological alterations cause retinal physiological dysfunction and trigger photoreceptor apoptosis. Remarkably, the initial ERGs of 6-month-old mice (young mice) did not show significant differences compared to age-matched controls, but electrophysiological altered responses became very apparent in 18-month-old mice. In this respect, although not all of the phenotypic traits are shared between human and mouse, the retinal phenotype of the CerklKD/KO mouse model is by far more similar to the slow and progressive retinal neurodegeneration shown by human patients bearing the most prevalent CERKL mutation (p.R283*) than to other reported mouse models. This valuable model will be instrumental in determining the role of CERKL in the retina and testing the efficacy of potential therapeutic approaches.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the support and commitment of patients and associations to this work. The authors also acknowledge the technical support of Alba Pons-Pons and Paula Escudero-Ferruz.

Supported by Grants SAF2013-49069-C2-1-R and SAF2016-80937-R (Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad/FEDER), ACCI 2015 and ACCI 2016 (CIBERER /ISCIII), and 2017 SGR 738 (Generalitat de Catalunya) to GM; La Marató TV3 (Project Marató 201417-30-31-32) and FUNDALUCE funding for research projects to RGD; and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, cofounded with the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) within the Plan Estatal de Investigación Científica y Técnica y de Innovación 2017–2020 (RD16/0008/0020; FIS/PI 18-00754) to PdlV. EBD is a fellow of the FI-2017 (Generalitat de Catalunya), and SM has a postdoctoral contract with CIBERER/ISCIII.

Disclosure: E.B. Domènech, None; R. Andrés, None; M.J. López-Iniesta, None; S. Mirra, None; R. García-Arroyo, None; S. Milla, None; F. Sava, None; J. Andilla, None; P. Loza-Álvarez, None; P. de la Villa, None; R. Gonzàlez-Duarte, None; G. Marfany, None

References

- 1. Ferrari S, Di Iorio E, Barbaro V, Ponzin D, Sorrentino FS, Parmeggiani F. Retinitis pigmentosa: genes and disease mechanisms. Curr Genomics. 2011; 12: 238–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Haim M. Epidemiology of retinitis pigmentosa in Denmark. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2002; 80: 1–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Verbakel SK, van Huet RAC, Boon CJF, et al.. Non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2018; 66: 157–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tuson M, Marfany G, Gonzàlez-Duarte R. Mutation of CERKL, a Novel Human Ceramide Kinase Gene, Causes Autosomal Recessive Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP26). Am J Hum Genet. 2004; 74: 128–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Littink KW, Koenekoop RK, van den Born LI, et al.. Homozygosity mapping in patients with cone-rod dystrophy: novel mutations and clinical characterizations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010; 51: 5943–5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Auslender N, Sharon D, Abbasi AH, Garzozi HJ, Banin E, Ben-Yosef T. A common founder mutation of CERKL underlies autosomal recessive retinal degeneration with early macular involvement among Yemenite Jews. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007; 48: 5431–5438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aleman TS, Soumittra N, Cideciyan AV, et al.. CERKL mutations cause an autosomal recessive cone-rod dystrophy with inner retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; 50: 5944–5954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ali M, Ramprasad VL, Soumittra N, et al.. A missense mutation in the nuclear localization signal sequence of CERKL (p.R106S) causes autosomal recessive retinal degeneration. Mol Vis. 2008; 14: 1960–1964. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Inagaki Y, Mitsutake S, Igarashi Y. Identification of a nuclear localization signal in the retinitis pigmentosa-mutated RP26 protein, ceramide kinase-like protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006; 343: 982–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gomez-Muñoz A, Gangoiti P, Arana L, et al.. New insights on the role of ceramide 1-phosphate in inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013; 1831: 1060–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gómez-Muñoz A, Gangoit P, Granado MH, Arana L, Ouro A. Ceramide-1-phosphate in cell survival and inflammatory signaling. In: Chalfant C, Del Poeta M, eds. Sphingolipids as Signaling and Regulatory Molecules. New York, NY: Springer; 2010;118–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bornancin F, Metchcheriakova D, Stora S, et al.. Characterization of a ceramide kinase-like protein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005; 1687: 31–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tuson M, Garanto A, Gonzàlez-Duarte R, Marfany G. Overexpression of CERKL, a gene responsible for retinitis pigmentosa in humans, protects cells from apoptosis induced by oxidative stress. Mol Vis. 2009; 15: 168–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li C, Wang L, Zhang J, et al.. CERKL interacts with mitochondrial TRX2 and protects retinal cells from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014; 1842: 1121–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fathinajafabadi A, Pérez-Jiménez E, Riera M, Knecht E, Gonzàlez-Duarte R. CERKL, a retinal disease gene, encodes an mRNA-binding protein that localizes in compact and untranslated mRNPs associated with microtubules. PLoS One. 2014; 9: e87898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Garanto A, Riera M, Pomares E, et al.. High transcriptional complexity of the retinitis pigmentosa CERKL gene in human and mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 5202–5214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Graf C, Niwa S, Müller M, Kinzel B, Bornancin F. Wild-type levels of ceramide and ceramide-1-phosphate in the retina of ceramide kinase-like-deficient mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008; 373: 159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Garanto A, Vicente-Tejedor J, Riera M, et al.. Targeted knockdown of Cerkl, a retinal dystrophy gene, causes mild affectation of the retinal ganglion cell layer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012; 1822: 1258–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Riera M, Burguera D, Garcia-Fernàndez J, Gonzàlez-Duarte R. CERKL knockdown causes retinal degeneration in zebrafish. PLoS One. 2013; 8: e64048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Feng G, Mellor RH, Bernstein M, et al.. Neurotechnique imaging neuronal subsets in transgenic mice expressing multiple spectral variants of GFP. Neuron. 2000; 28: 41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Toulis V, Garanto A, Marfany G. Combining zebrafish and mouse models to test the function of deubiquitinating enzyme (DUBs) genes in development: role of USP45 in the retina. In: Matthiesen R, ed. Proteostasis: Methods and Protocols, New York, NY: Springer; 2016;85–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sun W, Li N, He S. Large-scale morphological survey of mouse retinal ganglion cells. J Comp Neurol. 2002; 451: 115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kong JH, Fish DR, Rockhill RL, Masland RH. Diversity of ganglion cells in the mouse retina: Unsupervised morphological classification and its limits. J Comp Neurol. 2005; 489: 293–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McCulloch DL, Marmor MF, Brigell MG, et al.. ISCEV standard for full-field clinical electroretinography (2015 update). Doc Ophthalmol. 2015; 130: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Avila-Fernandez A, Riveiro-Alvarez R, Vallespin E, et al.. CERKL mutations and associated phenotypes in seven Spanish families with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008; 49: 2709–2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zahid S, Branham K, Schlegel D, et al.. Retinal Dystrophy Gene Atlas. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International; 2018;51–53. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Roberts MR, Sirinivas M, Forrest D, Morreale de Escobar G, Reh TA. Making the gradient: thyroid hormone regulates cone opsin expression in the developing mouse retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006; 103: 6218–6223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen J, Nathans J. Genetic ablation of cone photoreceptors eliminates retinal folds in the retinal degeneration 7 (rd7) mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007; 48: 2799–2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ochocinska MJ, Muñoz EM, Veleri S, et al.. NeuroD1 is required for survival of photoreceptors but not pinealocytes: results from targeted gene deletion studies. J Neurochem. 2012; 123: 44–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pan N, Jahan I, Lee JE, Fritzsch B. Defects in the cerebella of conditional Neurod1 null mice correlate with effective Tg(Atoh1-cre) recombination and granule cell requirements for Neurod1 for differentiation. Cell Tissue Res. 2009; 337: 407–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Naya FJ, Huang HP, Qiu Y, et al.. Diabetes, defective pancreatic morphogenesis, and abnormal enteroendocrine differentiation in BETA2/NeuroD-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 1997; 11: 2323–2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sensiglio JD, Cho GY, Paavo M, et al.. Hyperautofuorescent dots are characteristic in ceramide kinase like-associated retinal degeneration. Sci Rep. 2019; 9: 876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rodríguez-Muñoz A, Aller E, Jaijo T, et al.. Expanding the clinical and molecular heterogeneity of nonsyndromic inherited retinal dystrophies. J Mol Diagn. 2020; 22: 532–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hu X, Lu Z, Yu S, et al.. CERKL regulates autophagy via the NAD-dependent deacetylase SIRT1. Autophagy. 2019; 15: 453–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yu S, Li C, Biswas L, et al.. CERKL gene knockout disturbs photoreceptor outer segment phagocytosis and causes rod-cone dystrophy in zebrafish. Hum Mol Genet. 2017; 26: 2335–2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Roche SL, Ruiz-Lopez AM, Moloney JN, Byrne AM, Cotter TG. Microglial-induced Müller cell gliosis is attenuated by progesterone in a mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa. Glia. 2018; 66: 295–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.