Abstract

Accurate tumor detection and establishment of disease extent are important for optimal management of prostate cancer. Disease stage, beginning with identification of the index prostate lesion, followed by primary tumor, lymph node, and distant metastasis evaluation, provide crucial clinical information that not only have prognostic and predictive value, but guide patient management. A wide array of radiological imaging modalities including ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging have been used for the purpose of prostate cancer staging with variable diagnostic performance. Especially, the last years have seen remarkable technological advances in magnetic resonance imaging technology, enabling referring clinicians and radiologists to obtain even more valuable data regarding staging of prostate cancer. Marked improvements have been seen in detection of the index prostate lesion and evaluation of extraprostatic extension while further improvements are still needed in identifying metastatic lymph nodes. Novel approaches such as whole-body MRI are emerging for more accurate and reproducible assessment of bone metastasis. Post-treatment assessment of prostate cancer using radiological imaging is a topic with rapidly changing clinical context and special consideration is needed for the biochemical setting, that is, the relatively high serum prostate-specific antigen levels in studies assessing the value of radiological imaging for posttreatment assessment and emerging therapeutic approaches such as early salvage radiation therapy. The scope of this review is to provide the reader insight into the various ways radiology contributes to staging of prostate cancer in the context of both primary staging and posttreatment assessment. The strengths and limitations of each imaging modality are highlighted as well as topics that warrant future research.

Tumor Detection and Primary Staging

Primary staging of prostate cancer can be applied to several clinical scenarios that include the following: (1) detecting abnormal lesions in biopsy-naïve patients with clinical suspicion of prostate cancer (eg, elevated serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels or a positive digital rectal exam); (2) detecting cancer in patients who had negative biopsy results despite persisting clinical suspicion of prostate cancer (eg. rising PSA); or (3) staging in patients with biopsy-proven prostate cancer (1).

Identification of Index Lesion

The overarching goal in this context is to identify the presence of clinically significant prostate cancer, as not all cancers lead to adverse outcomes such as cancer-related deaths. In fact, it is well known based on clinical and autopsy studies that a significant proportion of prostate tumors grow at a rate so slow that patients will often die from other causes even before the prostate cancer starts to manifest with any clinical symptoms or signs (2). Several radiological imaging modalities have been used for detecting prostate cancer, including US, CT and MRI. Although there have been several reports showing that US (especially with advanced US technology such as elastography and contrast-enhanced US) and CT can be helpful, these modalities have inherent pitfalls such as high inter-operator variability (for US) and limited capability for soft tissue contrast, which hinders their application in clinical practice (3–6). Currently, MRI is accepted as the conventional imaging method that can be used to detect the index primary prostatic lesion with the highest accuracy and reproducibility. A multiparametric (mp) imaging approach is recommended, which includes anatomical sequences of T1-weighted (T1W) and T2-weighted (T2W) images and also functional sequences such as diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI (1). Magnetic resonance spectroscopy has been advocated in the past (7); but is currently deemed optional and no longer required as part of the contemporary mpMRI protocol due to low spatial resolution and long acquisition time of the commonly used acquisition protocols (8). For standardization and optimization of image acquisition and interpretation of mpMRI, one of the most up-to-date trends is to use the prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PIRADS) version 2 (9). Based on a recent meta-analysis, PIRADS version 2 shows relatively good diagnostic performance for detecting prostate cancer with a pooled sensitivity of 0.89 (95% CI 0.84–0.92) with specificity of 0.73 (95% CI 0.46–0.78) based on 21 studies (10).

Primary Tumor Staging

After initial detection of the index prostate lesion, the next step is “staging”. Primary tumor staging, or T staging, can be done in terms of various aspects using radiological imaging modalities. There has been attempts to use MRI for determination of tumor size, but MRI can substantially under- or over-estimate the size of the tumor specimens with wide variability (11, 12). One of the most important roles of imaging in T staging is assessment of the presence of extraprostatic extension (EPE) (Figure 1). Extraprostatic extension refers to either local extension beyond the prostatic capsule (ECE), into the seminal vesicles (SVI), or to adjacent organs. Identifying the presence of EPE is of utmost importance in that if present, it is associated with an increased likelihood of adverse outcomes (eg, postoperative biochemical recurrence) and that is crucial in optimizing patients’ management strategies (13). Despite advances in MRI technology, T2WI remains the main MRI sequences for evaluating EPE as it has inherently high spatial resolution (for outlining the margin of the tumor and prostate) and relatively high contrast resolution between tumor and the normal prostatic tissue. Specific imaging findings on T2WI such as broad tumor contact, bulging of the capsule, obliteration of the rectoprostatic angle, and asymmetry of the neurovascular bundle have been shown to be associated with ECE (14). In addition, low signal intensity within the seminal vesicle with loss of its normal architecture on T2WI is highly predictive of SVI and MRI has been shown to improve the performance in predicting SVI when added to clinical nomograms (eg, Kattan nomogram) (15, 16). Based on meta-analysis of 38 studies including 4001 patients, the pooled sensitivity and specificity of overall detection of stage T3 prostate cancer was 0.61 (95% CI 0.54–0.67) and 0.88 (95% CI 0.85–0.91), respectively (17). As such, albeit the relatively high specificity, there is much room for improvement with regard to the sensitivity for determining EPE. Until now, assessment of EPE has mostly been done on subjective analysis like the Likert scale for likelihood of EPE and have been criticized that the level of experience could alter the diagnostic performance (14, 18). Therefore, more recent efforts focus on finding ways to potentially improve diagnostic accuracy and to reduce inter-observer variability. Some examples of these are quantitative biomarkers such as tumor size/volume (19), length of capsular contact, ADC calculated DWI, and DCE parameters. Larger tumor size of greater length of contact between the tumor and prostatic capsule (>12–14 mm) (20), either measured on cross-sectional imaging or US (21), have been shown to independently significant predictive factors of EPE. Lower tumor ADC values have also been shown to improve the prediction of EPE compared to T2WI alone in numerous studies (22, 23). Several DCE MRI variables such as plasma flow (PF) and mean transit time (MTT) have also shown ability to predict EPE (24). These functional MRI sequences are thought to of incremental value as they indirectly provide information associated with tumor aggressiveness (i.e., Gleason score, cellularity, and angiogenesis). In addition, standardized image interpretation (i.e., PIRADS) should contribute to diagnostic performance and leveling out the differences between readers with different levels of experience (25).

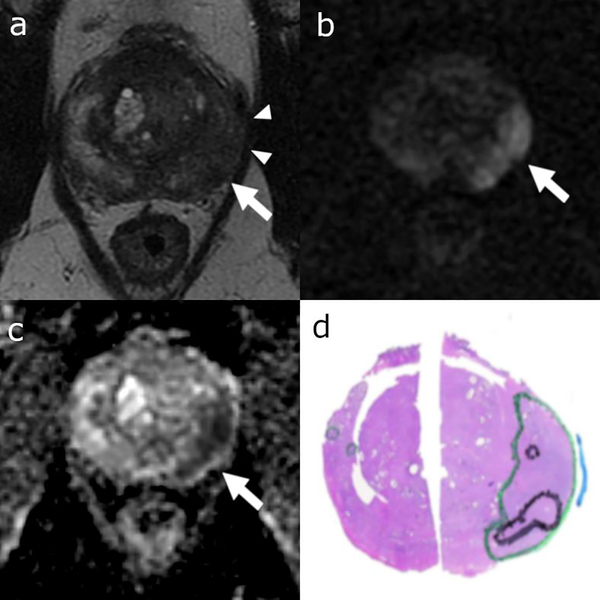

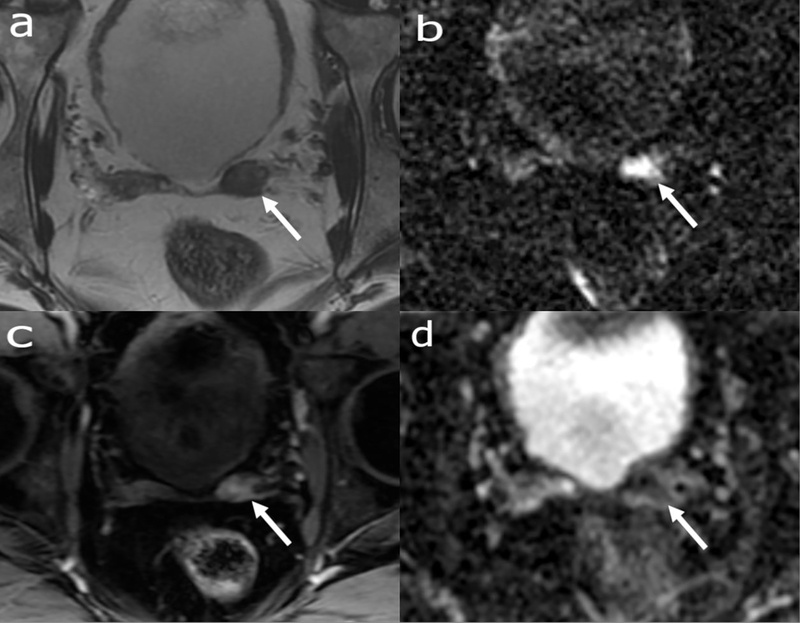

Figure 1:

Axial T2 weighted (a), DWI (b) and ADC (c) MRI images and correlating representative pathology tumor map (d) from whole-mount slide. Colored ink outlines tumor location (green = Gleason pattern 3, black = Gleason pattern 4 or 5, blue = areas of extracapsular extension). 58-year-old patient with a left posterolateral peripheral zone base to mid gland dominant lesion on T2 weighted images (arrows in a-c), diffusion restriction with broad capsular abutment suspicious for extracapsular extension (arrowheads in a, blue ink in d).

Lymph Node Staging

Lymph node staging, has been an area of interest for the use of radiological imaging. However, as of now, no single modality has shown an optimal diagnostic performance to detect or rule out metastatic lymph nodes. While US has virtually no role in this area, radiologists have traditionally used certain size- and shape-specific criteria on CT and MRI to assess lymph node metastasis. For example, one of the most commonly used criteria for metastatic lymph nodes from prostate cancer is a round lymph node with short axis diameter greater than 8 mm or an oval node with larger than 10 mm (26). With use of such size and shape criteria, both the sensitivity and specificity are low with reported pooled estimates of 0.42 (95% CI, 0.26–0.56) and 0.82 (95% CI, 0.8–0.83), respectively according to a meta-analysis of 24 studies based on CT and MRI (27). The low sensitivity of using cross-sectional imaging, especially arises from the fact that LNs that harbor only microscopic metastasis does not show significant changes in size and shape (Figure 2); while benign processes such as reactive hyperplasia can also lead to enlarged LNs, and in turn, false-positive results for metastatic LNs (28). Therefore, in clinical practice, routine or extended pelvic lymph node dissection is commonly practiced with up to one third of patients without suspicious looking LNs on cross-sectional imaging found to have actually had metastatic LNs (29).

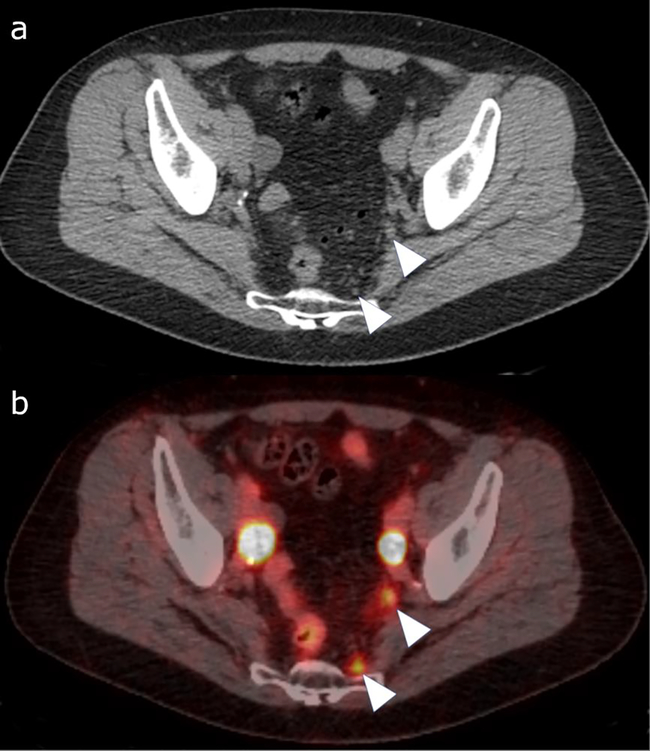

Figure 2:

Gallium-68 PSMA PET/CT study with the CT (a) and fused PET/CT (b) image. 67-year-old patient with biochemical recurrence following radical prostatectomy, pelvic lymph node dissection and radiation. The CT image shows punctate pelvic lymph nodes, not suspicious based on morphology (arrow heads in a). The fused image shows uptake within small left internal iliac and presacral lymph nodes (arrowheads in b), suspicious for metastasis.

In the recent years, intensive efforts to improve the diagnostic performance of CT and MRI for detecting LN metastasis have been carried out. Up to now the most promising technique seems to be the use of a lymphotropic MRI contrast agent, ultrasmall superparamagnetic particles of iron oxide (USPIO). Several studies have shown that using USPIO even microscopic metastasis can be identified with high accuracy in patients with prostate cancer (30–35). In addition, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that although there has not been a substantial improvement in the diagnostic performance of MRI in LN staging (pooled sensitivity and specificity of 0.56 and 0.94, respectively, in 24 studies with 2928 patients), studies using USPIO had significantly greater sensitivity of 0.84 (0.71–0.97) than those that did not use USPIO (0.46, 95% CI 0.34–0.58) which is comparable to the performance of prostate-specific membrane antigen PET/CT (0.86 95% CI 0.37–0.98) (36, 37). This improved capability of USPIO in detecting micrometastasis seems to stem from its unique characteristics. After USPIO injected, it leaks into the extravascular space, is taken up by the lymphatics to the lymph nodes and then is internalized by macrophages. As USPIO is superparamagnetic accumulation of the contrast agent lead to T2 shorting and in turn decreased signal intensity (SI) on T2WI and T2*WIs. However, LNs harboring metastasis will have areas having no or few normal macrophages, and therefore will not show decreased SI (38). Nevertheless, there are still obstacles for the translation of USPIO from the research realm into real-life clinical practice. The most important factor is the lack of commercial availability and regulatory approvals of USPIO agents. Ferumoxtran-10, the USPIO agent used in the studies above, is only manufactured privately in the Netherlands. Agents with similar properties such as Ferumoxytol, which was originally approved for iron replacement therapy in anemia associated with renal failure are being tested as an alternative with better availability (39). Other drawbacks include the need for two separate image interpretation sessions (baseline and 24–36 hours after injection of USPIO) (38), inter-reader variability associated with level of reader experience (32, 40), and potential adverse reactions (eg, back pain, hypersensitivity reactions, hypotension, and chest pain) (41).

Based on the published literature, other advanced MRI sequences do not seem to provide substantial incremental value in the N staging of prostate cancer either due to lack of studies testing the MRI sequence (eg, DCE-MRI) or due to absence of improved diagnostic performance when additionally using the MRI sequence (eg, DWI) (36). Although these DWI may not directly contribute to prediction of metastatic LNs, studies have shown that DWI used in conjunction with USPIO may not only improve diagnostic performance, but also shorten interpretation time and reduce inter-reader variability (34, 35).

Distant Metastasis Staging

Distant metastasis (M) staging for patients with prostate cancer typically focuses on detecting bone metastasis, which is the most common site of initial metastasis. Metastasis to other visceral organs can occur and is particularly important in certain situations, for example: (1) the presence of visceral metastasis precluding radionuclide therapy (i.e., alpha-particle emitter, radium-223) for metastatic bone lesions (42); and (2) brain imaging to detect subclinical metastases in atypical prostate cancer histologies (eg. small cell or cribriform histological subtypes) (43).

Radiological imaging is important to identify bone metastasis, especially in patients with high-risk or locally-advanced prostate cancer. At present, bone scans and CT are recommended by guidelines for detection of metastatic bone disease, but due to their low sensitivity and specificity, it is generally recognized that more advanced techniques are needed for this purpose (44). Although in general, PET/CT using different radiopharmaceuticals (PSMA, choline, and fluciclovine) is considered to be the primary next generation imaging method for bone metastasis by experts (45), whole body MRI could also play a role in this area. A recent meta-analysis of 10 studies with 1031 patients demonstrated that pooled sensitivity and specificity of MRI for detection of bone metastasis in patients with prostate cancer were 0.96 (95% CI 0.87–0.99) and 0.98 (95% CI 0.93–0.99) on a per-patient basis (46). Nevertheless, there has been concern on issues regarding verification bias (i.e., not all bone lesions can be confirmed as metastasis pathologically), the fact that previous studies are based on per-patient analysis but not per-lesion analysis, and that routine prostate MRI does not cover all areas of potential bone metastasis (eg, cervicothoracic spine, ribs and appendicular skeletons) (47, 48). To this end, whole body MRI could play a key role in not only bone metastasis imaging, but also may be the solution for “one size fits all” approach for detecting and monitoring metastasis in general (i.e., bones, lymph nodes, and visceral metastases) (49). Sequence components for whole body MRI generally require the following: (1) whole spine sagittal T1WI, (2) whole spine sagittal STIR or fat saturated T2WI, (3) whole body axial or coronal T1WI, and (4) whole body axial DWI with calculation of ADC values (50). However, based on a consensus meeting by a multidisciplinary panel of experts in prostate cancer, a consensus for using whole body MRI has not been achieved yet, and this is thought to have arisen from lack of standardization for acquisition and interpretation of whole body MRI and experience in this area (51). Recent efforts to overcome these hurdles include the METastasis Reporting and Data System for Prostate Cancer (MET-RADS-p) which aims for standardization and decreasing variability of whole body MRI, and in turn in anticipated to act as a catalyst for increased use and verification of whole body MRI for potential contribution in patients with prostate cancer (50).

Post-treatment Assessment

Post-treatment assessment refers to detection of local recurrence or metastasis in patients with rising PSA levels or other clinical suspicion of prostate cancer recurrence after primary treatment (eg, radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy). This is an area of rapidly changing clinical context due to accumulating evidence of imaging modalities and treatment methods.

MRI has been the mainstay of the contemporary approach for detecting locally recurrent prostate cancer among all conventional imaging modalities. Bone scans and CT are commonly used in this clinical setting despite of their low yield for detecting recurrence or metastasis, at least partly due to easier accessibility. For example, in a previous study including 93 patients with PSA relapse after radical prostatectomy, it was shown that the bone scans were of limited value as the probability of a positive scan was <5%, unless PSA levels were very high (>40–45 ng/mL) (52). In addition, another study assessing CT in patients with biochemical recurrence, it was found that the positivity of CT was 0% in med with low PSA levels (<10ng/ml) (53). On the other hand, there does seem to be improved diagnostic performance when using MRI. Especially when using multiparametric MRI, relatively high pooled sensitivities and specificities of 0.84 and 0.85 for detection of locoregional recurrences in patients with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy have been reported (54). Furthermore, multiparamateric MRI using T2WI, DWI and DCE MRI has been shown to demonstrated moderate sensitivity and high specificity of 0.71 and 0.94, respectively, for detection of locally recurrent prostate cancer after radiation therapy (55). However, interpretation of these studies using MRI need to be done with caution. The mean PSA levels of the study populations at the time of MRI in available studies range between 0.71 and 5.26 ng/ml with upper limits ranging from 1.7–68.3 ng/ml, which is considered to be above what would be clinically acceptable today without intervention (56–63). Contemporary guidelines suggest that patients receive salvage radiation therapy before PSA levels rise over 0.5 ng/ml (64). Therefore, more recent efforts focus on assessing the performance of MRI in patients experiencing early post-prostatectomy PSA elevation. For example, in a study of 142 patients with PSA elevation of ≤1 ng/mL after radical prostatectomy, pelvic MRI was only positive in 11% of the patients predominantly in the form of local recurrence (65). Based on these studies, it may be premature to strongly advocate the use of conventional radiological imaging modalities to guide management in all patients with biochemical recurrence. Not only is salvage radiation therapy is done commonly empirically without confirmation on imaging or pathology, there is available evidence indicating that patients with biochemical recurrence with no detectable lesions on multiparametric MRI, the majority of them showed response to salvage radiation therapy (66). Additional evidence shows that “early” or “very early” salvage radiation therapy, with variable definitions of PSA levels <0.5 ng/ml (67, 68), <0.2 ng/ml (69), or even at the very first sign of PSA rise improve outcomes (70).

Conclusion

The role of radiological imaging modalities in staging of prostate cancer is continuously evolving. Currently, multiparametric MRI is the accepted modality of choice, especially for detecting the index prostate lesion and evaluation of extraprostatic extension. Areas of further improvement include N and M staging. While MRI has shown some value in the context of post-treatment assessment, future studies with patients having low PSA levels are needed to meet the shifting paradigm of early salvage therapy. Knowledge of the strengths and limitations of each imaging modality is crucial for accurately interpreting images and understanding the role of their contribution to prostate cancer staging.

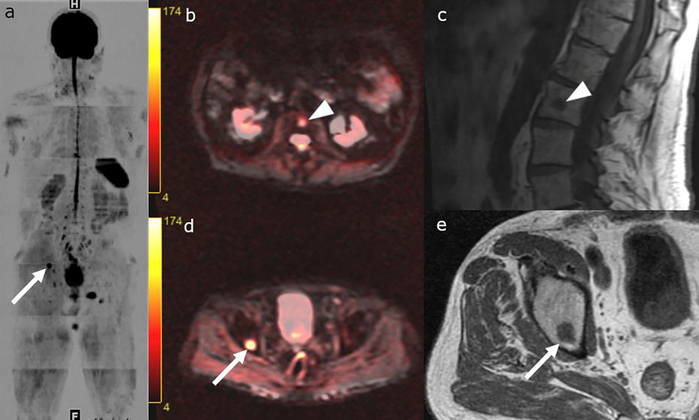

Figure 3:

Whole body MRI with greyscale inverted DWI image (a), axial T1-weighted and DWI fused images (b and d), sagittal (c) and axial (e) T1 weighted images. 79-year-old patient with metastatic Gleason 8 Prostate Cancer. T1 hypointense lesions with diffusion restriction in the right superior acetabulum (arrows in a, d-e) and L2 vertebral body (b-c), consistent with metastases.

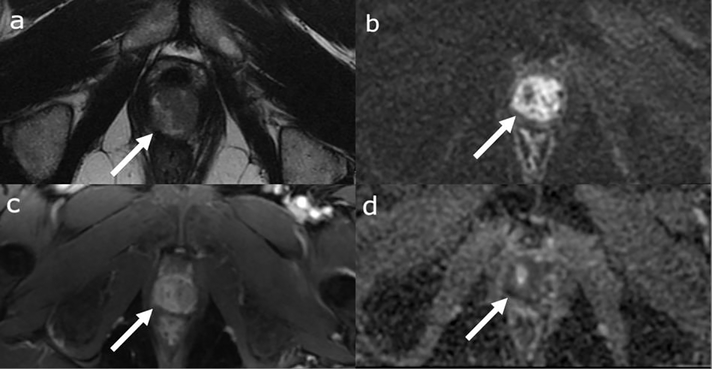

Figure 4:

Multiparametric Prostate MRI with axial T2 weighted image (a), DWI (b), dynamic contrast enhanced image (c) and ADC (d). 63-year-old patient with rising PSA 10 years after radical prostatectomy. MRI shows a new mass at the site of the vesicourethral anastomosis (arrow in a) with diffusion restriction (arrows in b and d) and avid enhancement (arrow in c).

Figure 5:

Multiparametric Prostate MRI with axial T2 weighted image (a), DWI (b), dynamic contrast enhanced image (c) and ADC (d). 72-year-old patient with biochemical recurrence with a T2 intermediate nodular mass (arrow in a) with diffusion restriction (arrows in b-c) and early avid enhancement (arrow in d) in the left seminal vesicle surgical bed suspicious for recurrent tumor.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Turkbey B, Brown AM, Sankineni S, Wood BJ, Pinto PA, Choyke PL. Multiparametric prostate magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of prostate cancer. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2016;66(4):326–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powell IJ, Bock CH, Ruterbusch JJ, Sakr W. Evidence supports a faster growth rate and/or earlier transformation to clinically significant prostate cancer in black than in white American men, and influences racial progression and mortality disparity. The Journal of urology. 2010;183(5):1792–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woo S, Suh CH, Kim SY, Cho JY, Kim SH. Shear-Wave Elastography for Detection of Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Diagnostic Meta-Analysis. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2017;209(4):806–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Y, Tang J, Fei X, Gao Y. Diagnostic performance of contrast enhanced ultrasound in patients with prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. Academic radiology. 2013;20(2):156–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho JY, Kim SH, Lee SE. Peripheral hypoechoic lesions of the prostate: evaluation with color and power Doppler ultrasound. European urology. 2000;37(4):443–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schieda N, Al-Dandan O, Shabana W, Flood TA, Malone SC. Is primary tumor detectable in prostatic carcinoma at routine contrast-enhanced CT? Clinical imaging. 2015;39(4):623–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, Hricak H, Shukla-Dave A, Akin O, Ishill NM, Carlino LJ, et al. Clinical stage T1c prostate cancer: evaluation with endorectal MR imaging and MR spectroscopic imaging. Radiology. 2009;253(2):425–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li B, Cai W, Lv D, Guo X, Zhang J, Wang X, et al. Comparison of MRS and DWI in the diagnosis of prostate cancer based on sextant analysis. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 2013;37(1):194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinreb JC, Barentsz JO, Choyke PL, Cornud F, Haider MA, Macura KJ, et al. PI-RADS Prostate Imaging - Reporting and Data System: 2015, Version 2. European urology. 2016;69(1):16–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woo S, Suh CH, Kim SY, Cho JY, Kim SH. Diagnostic Performance of Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System Version 2 for Detection of Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Diagnostic Meta-analysis. European urology. 2017;72(2):177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Nobin J, Orczyk C. Prostate tumour volumes: evaluation of the agreement between magnetic resonance imaging and histology using novel co-registration software. 2014;114(6b):E105–e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazaheri Y, Hricak H, Fine SW, Akin O, Shukla-Dave A, Ishill NM, et al. Prostate tumor volume measurement with combined T2-weighted imaging and diffusion-weighted MR: correlation with pathologic tumor volume. Radiology. 2009;252(2):449–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Godoy G, Tareen BU, Lepor H. Site of positive surgical margins influences biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. BJU international. 2009;104(11):1610–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu KK, Hricak H, Alagappan R, Chernoff DM, Bacchetti P, Zaloudek CJ. Detection of extracapsular extension of prostate carcinoma with endorectal and phased-array coil MR imaging: multivariate feature analysis. Radiology. 1997;202(3):697–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sala E, Akin O, Moskowitz CS, Eisenberg HF, Kuroiwa K, Ishill NM, et al. Endorectal MR imaging in the evaluation of seminal vesicle invasion: diagnostic accuracy and multivariate feature analysis. Radiology. 2006;238(3):929–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang L, Hricak H, Kattan MW, Chen HN, Kuroiwa K, Eisenberg HF, et al. Prediction of seminal vesicle invasion in prostate cancer: incremental value of adding endorectal MR imaging to the Kattan nomogram. Radiology. 2007;242(1):182–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Rooij M, Hamoen EH, Witjes JA, Barentsz JO, Rovers MM. Accuracy of Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Local Staging of Prostate Cancer: A Diagnostic Meta-analysis. European urology. 2016;70(2):233–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wibmer A, Vargas HA, Donahue TF, Zheng J, Moskowitz C, Eastham J, et al. Diagnosis of Extracapsular Extension of Prostate Cancer on Prostate MRI: Impact of Second-Opinion Readings by Subspecialized Genitourinary Oncologic Radiologists. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2015;205(1):W73–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim C, Flood TA, Hakim SW, Shabana WM, Quon JS, El-Khodary M, et al. Evaluation of apparent diffusion coefficient and MR volumetry as independent associative factors for extraprostatic extension (EPE) in prostatic carcinoma. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 2016;43(3):726–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woo S, Kim SY, Cho JY, Kim SH. Length of capsular contact on prostate MRI as a predictor of extracapsular extension: which is the most optimal sequence? Acta radiologica (Stockholm, Sweden : 1987). 2017;58(4):489–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ukimura O, Troncoso P, Ramirez EI, Babaian RJ. Prostate cancer staging: correlation between ultrasound determined tumor contact length and pathologically confirmed extraprostatic extension. The Journal of urology. 1998;159(4):1251–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chong Y, Kim CK, Park SY, Park BK, Kwon GY, Park JJ. Value of diffusion-weighted imaging at 3 T for prediction of extracapsular extension in patients with prostate cancer: a preliminary study. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2014;202(4):772–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woo S, Cho JY, Kim SY, Kim SH. Extracapsular extension in prostate cancer: added value of diffusion-weighted MRI in patients with equivocal findings on T2-weighted imaging. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2015;204(2):W168–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sertdemir M, Weidner AM, Schoenberg SO, Morelli JN, Haecker A, Kirchner M, et al. Is There a Role for Functional MRI for the Assessment of Extracapsular Extension in Prostate Cancer? Anticancer research. 2018;38(1):427–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schieda N, Quon JS, Lim C, El-Khodary M, Shabana W, Singh V, et al. Evaluation of the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR) PI-RADS scoring system for assessment of extraprostatic extension in prostatic carcinoma. European journal of radiology. 2015;84(10):1843–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jager GJ, Barentsz JO, Oosterhof GO, Witjes JA, Ruijs SJ. Pelvic adenopathy in prostatic and urinary bladder carcinoma: MR imaging with a three-dimensional TI-weighted magnetization-prepared-rapid gradient-echo sequence. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 1996;167(6):1503–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hovels AM, Heesakkers RA, Adang EM, Jager GJ, Strum S, Hoogeveen YL, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of CT and MRI in the staging of pelvic lymph nodes in patients with prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. Clinical radiology. 2008;63(4):387–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Studer UE, Scherz S, Scheidegger J, Kraft R, Sonntag R, Ackermann D, et al. Enlargement of regional lymph nodes in renal cell carcinoma is often not due to metastases. The Journal of urology. 1990;144(2 Pt 1):243–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bader P, Burkhard FC, Markwalder R, Studer UE. Is a limited lymph node dissection an adequate staging procedure for prostate cancer? The Journal of urology. 2002;168(2):514–8; discussion 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harisinghani MG, Barentsz J, Hahn PF, Deserno WM, Tabatabaei S, van de Kaa CH, et al. Noninvasive detection of clinically occult lymph-node metastases in prostate cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;348(25):2491–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harisinghani M, Ross RW, Guimaraes AR, Weissleder R. Utility of a new bolus-injectable nanoparticle for clinical cancer staging. Neoplasia (New York, NY). 2007;9(12):1160–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heesakkers RA, Hovels AM, Jager GJ, van den Bosch HC, Witjes JA, Raat HP, et al. MRI with a lymph-node-specific contrast agent as an alternative to CT scan and lymph-node dissection in patients with prostate cancer: a prospective multicohort study. The Lancet Oncology. 2008;9(9):850–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heesakkers RA, Jager GJ, Hovels AM, de Hoop B, van den Bosch HC, Raat F, et al. Prostate cancer: detection of lymph node metastases outside the routine surgical area with ferumoxtran-10-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 2009;251(2):408–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thoeny HC, Triantafyllou M, Birkhaeuser FD, Froehlich JM, Tshering DW, Binser T, et al. Combined ultrasmall superparamagnetic particles of iron oxide-enhanced and diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging reliably detect pelvic lymph node metastases in normal-sized nodes of bladder and prostate cancer patients. European urology. 2009;55(4):761–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Birkhauser FD, Studer UE, Froehlich JM, Triantafyllou M, Bains LJ, Petralia G, et al. Combined ultrasmall superparamagnetic particles of iron oxide-enhanced and diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging facilitates detection of metastases in normal-sized pelvic lymph nodes of patients with bladder and prostate cancer. European urology. 2013;64(6):953–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woo S, Suh CH, Kim SY, Cho JY, Kim SH. The Diagnostic Performance of MRI for Detection of Lymph Node Metastasis in Bladder and Prostate Cancer: An Updated Systematic Review and Diagnostic Meta-Analysis. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2018;210(3):W95–w109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perera M, Papa N, Christidis D, Wetherell D, Hofman MS, Murphy DG, et al. Sensitivity, Specificity, and Predictors of Positive (68)Ga-Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen Positron Emission Tomography in Advanced Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. European urology. 2016;70(6):926–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thoeny HC, Barbieri S, Froehlich JM, Turkbey B, Choyke PL. Functional and Targeted Lymph Node Imaging in Prostate Cancer: Current Status and Future Challenges. Radiology. 2017;285(3):728–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Provenzano R, Schiller B, Rao M, Coyne D, Brenner L, Pereira BJ. Ferumoxytol as an intravenous iron replacement therapy in hemodialysis patients. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2009;4(2):386–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Triantafyllou M, Studer UE, Birkhauser FD, Fleischmann A, Bains LJ, Petralia G, et al. Ultrasmall superparamagnetic particles of iron oxide allow for the detection of metastases in normal sized pelvic lymph nodes of patients with bladder and/or prostate cancer. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2013;49(3):616–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernd H, De Kerviler E, Gaillard S, Bonnemain B. Safety and tolerability of ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide contrast agent: comprehensive analysis of a clinical development program. Investigative radiology. 2009;44(6):336–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, Helle SI, O’Sullivan JM, Fossa SD, et al. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;369(3):213–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tremont-Lukats IW, Bobustuc G, Lagos GK, Lolas K, Kyritsis AP, Puduvalli VK. Brain metastasis from prostate carcinoma: The M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Cancer. 2003;98(2):363–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, Briers E, Cumberbatch MG, De Santis M, et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Part 1: Screening, Diagnosis, and Local Treatment with Curative Intent. European urology. 2017;71(4):618–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gillessen S, Attard G, Beer TM, Beltran H, Bossi A, Bristow R, et al. Management of Patients with Advanced Prostate Cancer: The Report of the Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference APCCC 2017. European urology 2018;73(2):178–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woo S, Suh CH, Kim SY, Cho JY, Kim SH. Diagnostic Performance of Magnetic Resonance Imaging for the Detection of Bone Metastasis in Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. European urology. 2018;73(1):81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lecouvet FE, Geukens D, Stainier A, Jamar F, Jamart J, d’Othee BJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the axial skeleton for detecting bone metastases in patients with high-risk prostate cancer: diagnostic and cost-effectiveness and comparison with current detection strategies. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(22):3281–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lecouvet FE, El Mouedden J, Collette L, Coche E, Danse E, Jamar F, et al. Can whole-body magnetic resonance imaging with diffusion-weighted imaging replace Tc 99m bone scanning and computed tomography for single-step detection of metastases in patients with high-risk prostate cancer? European urology. 2012;62(1):68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lecouvet FE, Talbot JN, Messiou C, Bourguet P, Liu Y, de Souza NM. Monitoring the response of bone metastases to treatment with Magnetic Resonance Imaging and nuclear medicine techniques: a review and position statement by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer imaging group. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2014;50(15):2519–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Padhani AR, Lecouvet FE, Tunariu N, Koh DM, De Keyzer F, Collins DJ, et al. METastasis Reporting and Data System for Prostate Cancer: Practical Guidelines for Acquisition, Interpretation, and Reporting of Whole-body Magnetic Resonance Imaging-based Evaluations of Multiorgan Involvement in Advanced Prostate Cancer. European urology. 2017;71(1):81–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fanti S, Minozzi S, Antoch G, Banks I, Briganti A, Carrio I, et al. Consensus on Molecular Imaging and Theranostics in Prostate Cancer. The Lancet Oncology. 2018. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cher ML, Bianco FJ, Jr., Lam JS, Davis LP, Grignon DJ, Sakr WA, et al. Limited role of radionuclide bone scintigraphy in patients with prostate specific antigen elevations after radical prostatectomy. The Journal of urology. 1998;160(4):1387–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Okotie OT, Aronson WJ, Wieder JA, Liao Y, Dorey F, De KJ, et al. Predictors of metastatic disease in men with biochemical failure following radical prostatectomy. The Journal of urology. 2004;171(6 Pt 1):2260–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sandgren K, Westerlinck P, Jonsson JH, Blomqvist L, Thellenberg Karlsson C, Nyholm T, et al. Imaging for the Detection of Locoregional Recurrences in Biochemical Progression After Radical Prostatectomy-A Systematic Review. European urology focus. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Donati OF, Jung SI, Vargas HA, Gultekin DH, Zheng J, Moskowitz CS, et al. Multiparametric prostate MR imaging with T2-weighted, diffusion-weighted, and dynamic contrast-enhanced sequences: are all pulse sequences necessary to detect locally recurrent prostate cancer after radiation therapy? Radiology. 2013;268(2):440–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kitajima K, Murphy RC, Nathan MA, Froemming AT, Hagen CE, Takahashi N, et al. Detection of recurrent prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy: comparison of 11C-choline PET/CT with pelvic multiparametric MR imaging with endorectal coil. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2014;55(2):223–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cha D, Kim CK, Park SY, Park JJ, Park BK. Evaluation of suspected soft tissue lesion in the prostate bed after radical prostatectomy using 3T multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging. 2015;33(4):407–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cirillo S, Petracchini M, Scotti L, Gallo T, Macera A, Bona MC, et al. Endorectal magnetic resonance imaging at 1.5 Tesla to assess local recurrence following radical prostatectomy using T2-weighted and contrast-enhanced imaging. European radiology. 2009;19(3):761–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sciarra A, Panebianco V, Salciccia S, Osimani M, Lisi D, Ciccariello M, et al. Role of dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR) imaging and proton MR spectroscopic imaging in the detection of local recurrence after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. European urology. 2008;54(3):589–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Panebianco V, Barchetti F, Sciarra A, Musio D, Forte V, Gentile V, et al. Prostate cancer recurrence after radical prostatectomy: the role of 3-T diffusion imaging in multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging. European radiology. 2013;23(6):1745–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Casciani E, Polettini E, Carmenini E, Floriani I, Masselli G, Bertini L, et al. Endorectal and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI for detection of local recurrence after radical prostatectomy. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2008;190(5):1187–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sella T, Schwartz LH, Swindle PW, Onyebuchi CN, Scardino PT, Scher HI, et al. Suspected local recurrence after radical prostatectomy: endorectal coil MR imaging. Radiology. 2004;231(2):379–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rischke HC, Schafer AO, Nestle U, Volegova-Neher N, Henne K, Benz MR, et al. Detection of local recurrent prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy in terms of salvage radiotherapy using dynamic contrast enhanced-MRI without endorectal coil. Radiation oncology (London, England). 2012;7:185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, Joniau S, van der Kwast T, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: Treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. European urology. 2014;65(2):467–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vargas HA, Martin-Malburet AG, Takeda T, Corradi RB, Eastham J, Wibmer A, et al. Localizing sites of disease in patients with rising serum prostate-specific antigen up to 1ng/ml following prostatectomy: How much information can conventional imaging provide? Urologic oncology. 2016;34(11):482.e5–e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Buergy D, Sertdemir M, Weidner A, Shelan M, Lohr F, Wenz F, et al. Detection of Local Recurrence with 3-Tesla MRI After Radical Prostatectomy: A Useful Method for Radiation Treatment Planning? In vivo (Athens, Greece). 2018;32(1):125–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pfister D, Bolla M, Briganti A, Carroll P, Cozzarini C, Joniau S, et al. Early salvage radiotherapy following radical prostatectomy. European urology. 2014;65(6):1034–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Taguchi S, Shiraishi K, Fukuhara H. Optimal timing of salvage radiotherapy for biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy: is ultra-early salvage radiotherapy beneficial? 2016;11:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Abugharib A, Jackson WC, Tumati V, Dess RT, Lee JY, Zhao SG, et al. Very Early Salvage Radiotherapy Improves Distant Metastasis-Free Survival. The Journal of urology. 2017;197(3 Pt 1):662–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fossati N, Karnes RJ, Cozzarini C, Fiorino C, Gandaglia G, Joniau S, et al. Assessing the Optimal Timing for Early Salvage Radiation Therapy in Patients with Prostate-specific Antigen Rise After Radical Prostatectomy. European urology. 2016;69(4):728–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]