Abstract

Robust research shows that parenting stress is associated with reduced parental sensitivity toward their children (i.e., parental responsiveness), thus negatively influencing child outcomes. While there is strong research supporting these associations, most studies utilize self-report measures of responsiveness and exclude fathers. This study examines whether observed parental responsiveness mediates the relationship between parenting stress and child cognitive development, prosocial behavior, and behavior problems in a large sample of diverse low-income families. Data were obtained from the Building Strong Families Project (N=1,173). Dyadic bootstrapped mediation models were estimated in Mplus. For mothers and fathers, parenting stress was negatively associated with responsiveness (B = −.08, 95% CI = [−.14, −.02], p = .012), and responsiveness was positively associated with child cognitive development (B = .15, 95% CI = [.11, .19], p < .001) and child prosocial behavior (B = .12, 95% CI = [.08, .15], p < .001). Mothers’ responsiveness was negatively associated with child behavior problems (B = −.07, 95% CI = [−.13, −.01], p = .020), but fathers’ responsiveness was not (B = −.01, 95% CI = [−.06, .05], p = .814). For mothers and fathers, parenting stress was indirectly related to child cognitive development and prosocial behavior via responsiveness. Indirect effects were not found for mothers or fathers when predicting child behavior problems. To improve children’s wellbeing, interventions may consider strengthening responsiveness and reducing parental stress among both mothers and fathers.

Keywords: father, father-child relations, behavior problems, prosocial behavior, cognitive development, family stress model, parenting

1.0. Introduction

Parenting stress, which is characterized by taxing or frustrating interactions between parents and children (Abidin, 1995), is a challenge that many parents face. According to the National Survey of Children’s Health (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2014), parents of approximately 11% of children in the U.S. usually or always feel stress related to parenting. This percentage is higher for low-income families, where parents of approximately 19% of children usually or always feel parenting stress. Individuals may experience stress from being a parent for a multitude of reasons, including child-rearing difficulties, child-related financial burdens, child behavioral management, and the coordination of everyday parenting events. Nevertheless, parenting stress has long been recognized as a predictor of children’s outcomes, including child behavior problems, child attention problems, and child cognitive development (Guajardo, Snyder, & Peterson, 2009; Neece, Green, & Baker, 2012). Due to the prevalence of parenting stress being relatively high (USDHHS, 2014), it is essential to understand the consequences of parental stress as well as the factors that explain or mediate the relationship between parenting stress and children’s outcomes.

Prior research suggests that parenting stress influences parent-child interactions by reducing the quality of parental responsiveness, which may, in turn, influence child outcomes (Conger, Rueter, & Conger, 2000). Many existing studies measure parent-child interactions via maternal reports, which may be influenced by social desirability bias, recall bias, and other factors. Further, few studies have examined these relationships among fathers, even though the quality of father-child interactions can influence children’s outcomes (Cabrera, Volling, & Barr, 2018; McWayne, Downer, Campos, & Harris, 2013). To address these gaps in the literature, this study examines whether parenting stress relates to child outcomes via an observational measure of parental responsiveness among both mothers and fathers in a large sample of diverse low-income families.

1.1. Family Stress Model

Broadly, the family stress model (Conger et al., 2000; Conger et al., 2002; McLoyd, 1990) posits that financial stressors exert influence on parental psychological states, which impacts how parents interact with their children, which ultimately influences children’s outcomes. Parents who experience financial stress may engage in few nurturing behaviors toward their children, be more punitive toward their children, and show more indifference in interactions with their children (Elder, Nguyen, & Caspi, 1985; McLoyd, 1989). Further, changes in the quality of parenting due to financial stress has been linked with changes in child behavior, such as increased hyperactivity and aggression (Mistry, Vandewater, Huston, & McLoyd., 2002). These patterns may be amplified among racial and ethnic minority populations in the U.S., who tend to experience disproportionate amounts of financial strain and racial discrimination (McLoyd, 1990; Murry et al., 2001).

In recent years, researchers have extended the family stress model to examine external stressors beyond financial stress, including parenting stress, which can serve as a predictor of parent-child interactions. For example, parenting stress is shown to reduce parental responsiveness toward their children, which refers to parenting behaviors such as sensitivity to the child’s needs, quickly and contingently responding to children, and engaging in positive interactions with children (Landry, Smith, & Swank, 2006). Also, parents who have higher levels of parental stress tend to have an authoritarian parenting style, engage in harsh parenting, be less involved with their child, and have an insecure attachment with their child (Belsky, Woodworth, & Crnic, 1996; Rholes, Simpson, & Friedman, 2006; Tharner et al., 2012). This empirical evidence demonstrates that parenting stress is an important variable to consider in the context of the family stress model.

Although the family stress model theoretically accounts for the roles of both mothers and fathers in influencing child outcomes, most studies have focused on mothers. Recent studies suggest that higher maternal parenting stress is associated with lower child health ratings (Larkin & Otis, 2019), and mothers’ supportiveness mediates the relationship between parenting stress and child behavior problems (Cherry, Gerstein, & Ciciolla, 2019). When examining fathers, cross-sectional studies show that fathers’ parenting stress is associated with lower self-reported measures of caregiving involvement (Fagan, Bernd, & Whiteman, 2007) and child behavior problems (Lee, Pace, Lee, & Knauer, 2018). Longitudinal studies find that parenting stress significantly influences mothers’ and fathers’ parental sensitivity (Lau & Power, 2019; Pelchat, Bisson, Bois, & Saucier, 2003) as well as their responsiveness toward and involvement with their children (Coats & Phares, 2019; Ponnet et al., 2013). These studies suggest that, like mothers’ parenting stress, fathers’ parenting stress may be an important determinant of parenting-child interactions and child outcomes. However, existent studies are limited in study design (e.g., cross-sectional analysis; Fagan et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2018), measurement of the parent-child interactions (e.g., non-observational; Ponnet et al., 2013), and the lack of testing mechanisms that explain the relationship between parenting stress and child outcomes (e.g., Pelchat et al., 2003). This study aims to respond to these gaps by exploring whether mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress relates to future child outcomes through the mechanism of parental responsiveness.

1.2. Mothers’ and Fathers’ Responsiveness and Child Outcomes

Bornstein and colleagues (2008) define parental responsiveness as “… the prompt, contingent, and appropriate reactions parents display to their children in the context of everyday exchanges,” (Bornstein, Tamis-Lemonda, Hahn, & Haynes, 2008, pg. 867). In observational studies, parental responsiveness is measured based on the quality of the parent-child interaction, parents’ demonstration of positive regard toward their child, and parents’ sensitivity to the child. As parents respond promptly and warmly to their children in the context of caregiving and play, they provide a developmentally stimulating environment that can benefit children (Jeong et al., 2019). Responsive parenting behaviors are thought to foster healthy child outcomes, including cognitive development and prosocial behavior (Brady-Smith et al., 2013; Fuligni et al., 2013; Fuligni & Brooks-Gunn, 2013; Jeong et al., 2019; John, Halliburton, & Humphrey, 2013; Lemelin, Tarabulsy, & Provost, 2006; O’Neal, Weston, Brooks-Gunn, Berlin, & Atapattu, 2017; Wang, Christ, Mills-Koonce, Garrett-Peters, & Cox, 2013). Consistent with the family stress model, parenting stress inhibits’ parental responsiveness to their child (Crnic, Gaze, & Hoffman, 2005; Crnic & Ross, 2017).

Importantly, both fathers’ and mothers’ responsive parenting behaviors have an important impact on children’s outcomes (Cabrera et al., 2018; John et al., 2013; McWayne et al., 2013). Although there are relatively few studies examining father responsiveness in early childhood, studies show that the father-child relationship quality directly predicts child prosocial behavior (Ferreira et al., 2016). Positive paternal involvement is positively associated to children’s cognitive development (Dubowitz et al., 2001). In addition, fathers’ responsiveness in infancy is associated with fewer child externalizing behaviors in middle childhood (Trautmann-Villalba, Gschwendt, Schmidt, & Laucht, 2006).

1.3. Dyadic Models with Mothers and Fathers

Family researchers have long acknowledged that parents are non-independent from one another; thus, researchers need to account for this dependence in statistical analyses. Yet, much of the available literature either presents analyses that focus on mothers only, or places mothers and fathers in separate models. For example, in one study that analyzed mothers and fathers in separate models, the authors found that maternal, but not paternal, sensitivity was related to children’s prosocial behavior (Newton, Laible, Carlo, & Steele, 2014), suggesting that mothers’ sensitivity influences children’s prosocial behavior, while fathers’ sensitivity does not. However, Kenny (2010) cautions that by analyzing mothers and fathers in separate models, researchers may be reducing statistical power and finding differences between parents, when no such difference statistically exists. Ideally, mothers’ and fathers’ responsiveness could be analyzed in a dyadic fashion in order to account for both influences on future child outcomes (Kenny, 2010).

In addition to including mothers and fathers in the same statistical model, it is crucial to consider sociodemographic variables that may influence parenting stress, parental responsiveness, and child outcomes. For example, several factors can influence parenting stress, including postnatal depression, parental marital and/or cohabitation status, and the number of children parents have had together (Chang, et al., 2004; Cooper, McLanahan, Meadows, & Brooks-Gunn, 2009; Lee et al., 2018; Leigh & Milgrom, 2008). Additionally, parental age, race, income, and education level may influence the quantity and quality of parental responsiveness (Baker, 2017; Harper & Fine, 2006). Prior research also indicates that a child’s gender may be an important factor to consider, such that parents of girls may experience slightly less parenting stress when children are toddlers, and parents of boys tend to rate their children higher on problem behaviors (Willford, Calkins, & Keane, 2007). Thus, these variables may be relevant to account for in this study.

1.4. The Current Study

In summary, parental responsiveness may serve as a mechanism through which parenting stress affects child outcomes. Few studies to date have tested these associations among mothers and fathers simultaneously using dyadic models of observed parental responsiveness. This study responds to these gaps in the literature by (a) using an observed measure of parental responsiveness, (b) testing whether parental responsiveness serves as a mechanism in the relationship between parenting stress and child outcomes, (c) examining these associations among mothers and fathers simultaneously, and (d) modeling positive and negative child outcomes, including child cognitive development, child prosocial behavior, and child behavior problems. Using data from a large sample of diverse low-income families, we hypothesize the following:

Mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress at 15-months will be negatively associated with observed parental responsiveness at 36-months.

Mothers’ and fathers’ observed parental responsiveness at 36-months will be positively associated with child prosocial behavior and child cognitive development, and negatively associated with child behavior problems, at 36-months.

The relationship between mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress at 15-months will be indirectly related to all three child outcomes at 36-months via observed parental responsiveness at 36-months.

2.0. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

Data came from the Building Strong Families Project (BSF) study (Hershey, Devaney, Wood, & McConnell, 2014). The BSF project was a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of relationship education courses for low-income heterosexual couples aimed to improve child well-being and strengthen relationships. The control group did not receive services or participate in the relationship education intervention. Eligibility criteria included (1) the mother and father were both at least 18 years old, (2) the mother and father both provided informed consent to participate in the study, (3) the mother and father were expecting a baby or had a child under three months old, (4) the mother and father were romantically involved, and (5) the mother and father were unmarried at the time of their child’s conception. Couples were recruited from programs serving low-income families, such as maternity wards, hospitals, health clinics, prenatal clinics, and Special Supplemental Nutrition Programs for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) clinics. Given the fact that parents were unmarried at the start of the study and were recruited from sites that served low-income families, BSF is described as a low-income sample throughout BSF documentation (Dion, Avellar, & Clary, 2010). Data collection via survey occurred between 2005 and 2011 across eight U.S. sites at three time points: near the time of the child’s birth (Baseline), 15 months post-Baseline measure, and 36 months post-Baseline measure (Hershey et al., 2014). Mathematica Policy Research analyzed the effectiveness of the RCT and found no intervention effects on the study’s key outcomes, including father involvement, the likelihood of marriage, relationship quality, and co-parenting quality (Wood, Moore, Clarkwest, & Killewald, 2014). However, they did find a small intervention effect that suggested that children in the treatment group exhibited fewer behavior problems. Since BSF was an RCT, all analyses in this study controlled for assignment to the BSF intervention group. The Institutional Review Board at [omitted for blind review] considered our secondary analyses of de-identified data exempt from further review.

The full sample of BSF data included 5,102 couples. Only some couples participated in the in-person assessments, during which our key mediator variable, responsiveness, was measured (Hershey et al., 2014). Couples participating in the Florida, San Angelo, and Boston programs did not participate in the in-person assessments. At other sites, not all parents were invited to participate in the in-person assessments. According to Hershey and colleagues (2014), couples who enrolled very early and very late during the enrollment period were not invited to participate in the in-person assessments. Therefore, we dropped all participants who had missing data on the responsiveness variable (n = 3,929). This resulted in a final sample size of 1,173 families. Similarly, not all children took the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT; a key dependent variable); therefore, for analyses involving the PPVT, we dropped any child with missing PPVT data (n = 361), leaving a final sample size of 812 for the PPVT analyses.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the sample. On average, mothers were approximately 23 years old, and fathers were 26 years old. The majority of couples identified as Black (52%) and were unmarried at Baseline (92%) and 36-months (69%). Nearly half of couples both had a high school education (48%), and approximately half of the children in the sample were male (51%). The majority of couples stated they were living in the same household at least most of the time at 15-months (78%) and 36-months (70%), and only had one child together (75%). Some statistically significant correlations between study variables of interest include maternal responsiveness and maternal parenting stress (r = −0.12, p = .001); paternal responsiveness and paternal parenting stress (r = −0.09, p = .005); maternal parenting stress and maternal depression (r = 0.31, p < .001); and paternal depression and paternal parenting stress (r = 0.29, p < .001).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables (N = 1,173)

| Variable | M | SD | Min | Max | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers Parenting Stress, 15 months | 1.56 | 0.52 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Fathers Parenting Stress, 15 months | 1.52 | 0.52 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Mothers Parenting Stress, 36 months | 1.59 | 0.52 | 1 | 3.5 | ||

| Fathers Parenting Stress, 36 months | 1.60 | 0.51 | 1 | 3.5 | ||

| Mothers Responsiveness | 4.64 | 0.85 | 1.6 | 7 | ||

| Fathers Responsiveness | 4.58 | 0.86 | 1.6 | 7 | ||

| Child PPVT | 90.24 | 15.33 | 26 | 142 | ||

| Child Prosocial Behavior | 2.39 | 0.49 | 0.2 | 3 | ||

| Child Behavior Problems | 0.39 | 0.26 | 0 | 1.5 | ||

| Mothers Depressive Symptoms | 4.51 | 5.67 | 0 | 36 | ||

| Fathers Depressive Symptoms | 3.86 | 5.42 | 0 | 34 | ||

| Mothers Age | 23.20 | 4.75 | 18 | 41 | ||

| Fathers Age | 25.52 | 6.17 | 18 | 61 | ||

| Biological children | 1.35 | 0.72 | 1 | 5 | ||

| How Often Live Together, 15 months | 3.35 | 1.12 | 1 | 4 | ||

| How Often Live Together, 36 months | 3.08 | 1.26 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Income-to-Poverty Status, 15 months | 1.23 | 0.84 | 0 | 5.21 | ||

| Marital Status, Baseline | ||||||

| Unmarried | 1079 | 91.99 | ||||

| Married | 94 | 8.01 | ||||

| Marital Status, 36-Month | ||||||

| Unmarried | 815 | 69.48 | ||||

| Married | 358 | 30.52 | ||||

| Couple Race | ||||||

| White | 231 | 19.79 | ||||

| Black | 610 | 52.27 | ||||

| Hispanic | 209 | 17.91 | ||||

| Other | 117 | 10.03 | ||||

| Child Sex | ||||||

| Female | 545 | 48.92 | ||||

| Male | 569 | 51.08 | ||||

| Treatment Group | ||||||

| Control | 571 | 48.68 | ||||

| Treatment | 602 | 51.32 | ||||

| Parent Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 180 | 15.38 | ||||

| 1 parent high school diploma | 426 | 36.41 | ||||

| 2 parents high school diploma | 564 | 48.21 | ||||

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Parenting stress

Parenting stress was measured at the 15-month time point using the Aggravation in Parenting Scale (Ehrle & Moore, 1997). The scale contained four items measured on a scale from 1=none of the time to 4=all of the time assessing if parents felt their children are harder to care for than most; if the child did things that bothered them; if they felt they were giving up their lives to meet their child’s needs more than expected; and how angry they felt with their children. The scale’s internal reliability in our sample was lower than desired (mothers: α = .53, fathers: α = .52).

2.2.2. Mothers’ and fathers’ responsiveness

Parental responsiveness was measured at 36-months during the semi-structured two-bag play task, which was designed to elicit meaningful parent-child interactions. This task, which was a modified version of the three-bag task used in the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study- Birth Cohort (ECLS-B; Roisman & Fraley, 2008) as well as the Early Head Start Research and Evaluation Study (EHSREP; Nord et al., 2004), involved a 10-minute videotaped interaction where parents and children played with objects in bags in numerical order. Trained coders from Mathematica rated parents on five dimensions on a scale from 1=low to 7=very high: quality of the relationship, parents’ positive regard, parent cognitive stimulation, parent sensitivity, and parent detachment (reverse-coded). The scale exhibited good internal reliability in our sample (mothers: α = .85; fathers: α = .84).

2.2.3. Child PPVT

The PPVT-4 was administered to English-speaking children at the 36-month time point. The PPVT is a well established standardized measure of children’s receptive language development (Dunn & Dunn, 2007) that assesses their knowledge of the meaning of words. Within the test, children are given a series of words (ranging from easy to difficult) that are accompanied by a picture plate that contains multiple drawings. Children are instructed to point to the drawing that best represents each target word. The test typically takes approximately 20 to 30 minutes to complete and concludes when the difficulty level becomes too high for the child. Among population samples, the mean score of the PPVT is typically 100 and has a standard deviation of 15.

2.2.4. Child prosocial behaviour

Child prosocial behavior was measured at 36-months by mother-reported responses on the Social Interaction scale of the Preschool and Kindergarten Behavior Scales–Second Edition (PKBS-2; Merrell, 2002). On a four-point Likert scale (0=never, 1=rarely, 2=sometimes, 3=often), mothers rated nine items on how frequently child behaviors occurred over the past month. Sample items include, “How often did [child] comfort other children who were upset,” “How often did [child] invite other children to play,” and “How often did [child] show affection for other children.” The scale’s internal reliability in our sample was good (α = .75).

2.2.5. Child behavior problems

To measure child behavior problems at 36-months, mothers responded to 26 items on a three-point Likert scale (0=never true, 1=sometimes true, or 2=often true) from the Behavioral Problems Index (BPI; Peterson & Zill, 1986). Sample items include “[child] has a very strong temper and loses it easily,” “[child] demands a lot of attention,” and “[child] is unhappy, sad, or depressed.” The scale’s internal reliability in our sample was good (α = .86).

2.2.6. Control variables

Some control variables that could influence our key variables of interest were included in all analyses. Mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms at the 15-month time point were measured using the 12-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977). Mothers’ and fathers’ ages, the number of biological children the mother had with the father before the focal child was born (capped at 5), and maternal report of how often the parents lived together in the same household at 15- and 36-months (“residential status;” 1=none of the time, 2=some of the time, 3=most of the time, 4=all of the time) were specified as continuous variables. The couple’s income-to-poverty status at 15-months was also specified as a continuous variable. Marital status at the 15- and 36-month time points (0=unmarried, 1=married), child sex (0=girl, 1=boy), and treatment group (0=control, 1=treatment) were specified as dichotomous variables. Couples’ race was captured with a variable that Mathematica generated, which reflects the race of the couple; this variable was modeled with a set of dummy codes for whether couples identified as White (omitted), Black, Hispanic, or Other (“Other” included biracial couples). We also controlled for whether both parents had less than a high school education, whether one parent had a high school diploma, or both parents had a high school diploma (both parents having less than a high school education was specified as the comparison variable).

2.3. Statistical Analyses

We first scanned the data for missing data and outliers. No outliers were present. Scales in our models were all observed (i.e., no latent variables), and all scales were generated such that no missing values were permitted in the creation of the scale; nevertheless, few missing data were present on our key scales of interest (no missing data on responsiveness; 6.39% missing data on mothers’ parenting stress; 12.19% missing data on fathers’ parenting stress; <1% missing data on child behavior problems and child prosocial behavior). Therefore, we utilized full-information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML), which uses all available data and has been documented as a generally unbiased way to handle missing data in structural equation modeling (SEM; Kline, 2016). Our analyses utilized the maximum likelihood estimator, which provides estimates and standard errors that are robust to non-normality. To determine whether our data fit our specified model, we examined the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). For CFI, values of .95 and greater generally suggest a good fit. For RMSEA and SRMR, values of .05 and below generally suggest a good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Because our data were dyadic, we followed Kenny’s (2010) guidelines for analyzing dyadic data. First, we correlated mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress as well as mothers’ and fathers’ responsiveness measures. Next, we utilized SEM model comparison techniques, namely the chi-square difference test (χ 2 Δ), to examine whether constraining mothers’ and fathers’ paths to be equal fit the data better than unconstraining mothers’ and fathers’ paths. A non-significant chi-square difference test indicates that mothers and fathers have statistically indistinguishable effects on each of the outcome measures; however, a significant chi-square difference test indicates that the estimated pathways statistically differ for mothers and fathers. To examine mothers’ and fathers’ indirect effects, we utilized mediation bootstrapping techniques (500 bootstraps), which is the most rigorous test of indirect effects to date (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Following Shrout and Bolger’s (2002) recommendations for detecting indirect effects, we considered a statistically significant indirect effect to be detected through a bootstrapped 95% confidence interval that does not include zero.

Hypothesis 1 was examined by observing the pathways between parenting stress and parental responsiveness; Hypothesis 2 was examined by observing the pathways between parental responsiveness and the three child outcomes; Hypothesis 3 was examined by observing whether the 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effects excluded zero. Preliminary and descriptive analyses were conducted in Stata version 15.1, and path analyses were conducted in Mplus version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2018).

3.0. Results

3.1. Child Cognitive Outcomes

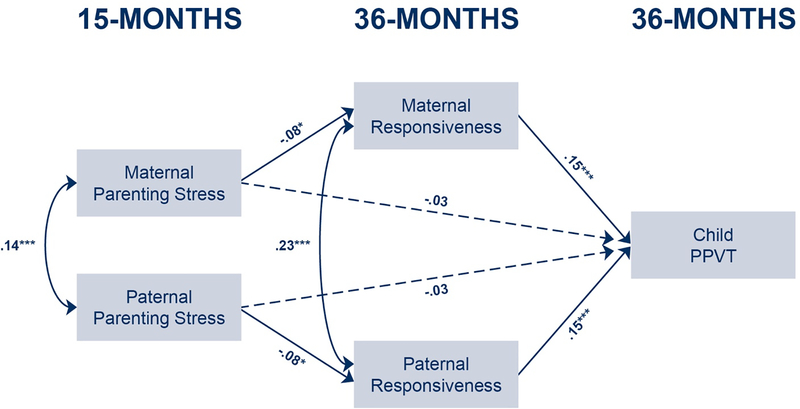

Results for the model examining child PPVT as the dependent variable are presented in Figure 1. When comparing the unconstrained and constrained model, the chi-square difference test was non-significant (χ 2Δ[3]= 5.03); therefore, the constrained model was examined. For both mothers and fathers, parenting stress at 15-months was negatively associated with parental responsiveness at 36-months (mothers and fathers: B = −.08, 95% CI = [−.14, −.02], p = .012). Additionally, parental responsiveness at 36-months was positively associated with child PPVT at 36-months (mothers and fathers: B = .15, 95% CI = [.11, .19], p < .001). In terms of the direct effect, neither mothers’ nor fathers’ parenting stress at 15-months was associated with child PPVT at 36-months (mothers and fathers: B = −.03, 95% CI = [−.07, .02], p = .289). A statistically significant indirect effect was found (b = −0.34, SE = .14, p = .017, bootstrapped 95% CI [−0.62, −0.06]), signaling that parenting stress at 15-months was indirectly related to child PPVT at 36-months through parental responsiveness at 36-months.

Figure 1.

Associations between parenting stress, responsiveness, and child PPVT. Mothers’ and fathers’ pathways are constrained.

Dotted lines indicate pathways where p > .05.

Note: Coefficients are standardized. Mothers’ and fathers’ pathways are constrained to be equal. Model controls for parental depression, race, education, age, number of biological children, child sex, treatment group, income-to-poverty ratio, marital status, and residential status.

N = 812 *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

CFI: 1.00, RMSEA: 0.02; SRMR: 0.00. Indirect effect, mothers and fathers: b = −0.34, SE = 0.14, p = .017, bootstrapped 95% CI: [−0.62, −0.06]

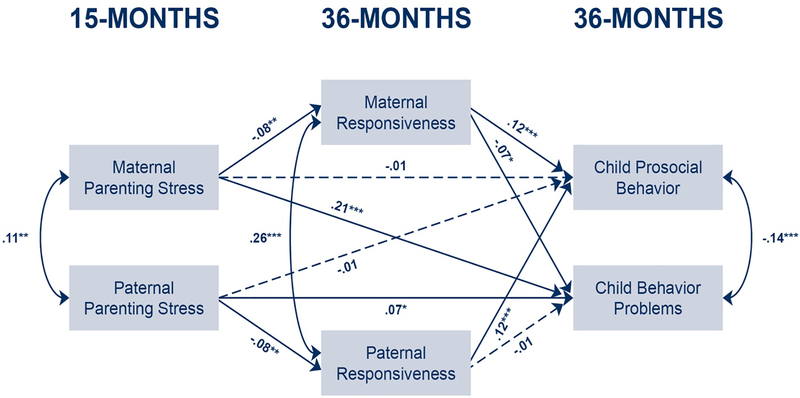

3.2. Child Prosocial Behavior and Child Behavior Problems

Results for the model examining child prosocial behavior and child behavior problems as the dependent variables are presented in Figure 2. When comparing the unconstrained and constrained model for child prosocial behavior, the chi-square difference test was non-significant (χ 2 Δ[3]= 1.20); therefore, constrained pathways were examined for prosocial behavior. When comparing the unconstrained and constrained model for child behavior problems, the chi-square difference test was significant for the model pathways from the parenting stress and responsiveness measures to child behavior problems (χ 2Δ[2]= 12.18); therefore, these pathways were unconstrained. For both mothers and fathers, parenting stress at 15-months was negatively associated with parental responsiveness at 36-months (mothers and fathers: B = −.08, 95% CI = [−.12, −.03], p = .002). Parental responsiveness at 36-months was positively associated with child prosocial behavior at 36-months (mothers and fathers: B = .12, 95% CI = [.08, .15], p < .001). In terms of the direct effect, neither mothers’ nor fathers’ parenting stress at 15-months was associated with child prosocial behavior at 36-months (mothers and fathers: B = −.01, 95% CI = [−.05, .03], p = .753). A small, but statistically significant indirect effect was found for prosocial behavior (b = −0.01, SE = .00, p = .007, bootstrapped 95% CI [−0.014, −0.002]), signaling that parenting stress at 15-months was indirectly related to child prosocial behavior at 36-months through parental responsiveness at 36-months.

Figure 2.

Associations between parenting stress, responsiveness, child prosocial behavior and child behavior problems. Mothers’ and fathers’ pathways are constrained, except for pathways from predicting child behavior problems. Dotted lines indicate pathways where p > .05.

Note: Coefficients are standardized. Model controls for parental depression, race, education, age, number of biological children, child sex, treatment group, income-to-poverty ratio, marital, and residential status.

N = 1,173 *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

CFI: 1.00, RMSEA: 0.00; SRMR: 0.00. Indirect effect, prosocial behavior, mothers and fathers: b = −0.01, SE = 0.00, p = .007, bootstrapped 95% CI [−0.014, −0.002]. Indirect effect, child behavior problems: mothers: b = 0.003, SE = 0.00, p = .065, bootstrapped 95% CI [0.00, 0.006] fathers: b = 0.00, SE = 0.00, p = .827, 95% CI [−0.002, 0.002].

Regarding child behavior problems, mothers’, but not fathers’, responsiveness at 36-months was associated with child behavior problems at 36-months (mothers: B = −.07, 95% CI = [−.13, −.01], p = .020; fathers: B = −.01, 95% CI = [−.06, .05], p = .814). In terms of the direct effect, both mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress at 15-months was associated with an increase in child behavior problems at 36-months, but mothers’ was more strongly related (mothers: B = .21, 95% CI = [.14, .28], p < .001; fathers: B = .07, 95% CI = [.01, .14], p = .032). The indirect effect was non-significant for both parents (mothers: b = 0.01, SE = .00, p = .067, bootstrapped 95% CI [0.000, 0.006]; fathers: 0.00, SE = .00, p = .827, bootstrapped 95% CI [−0.002, 0.002]).

3.3. Comparing Mothers’ and Fathers’ Patterns of Influence

Table 2 summarizes overall patterns of associations for mothers and fathers. For the child PPVT and prosocial behavior outcomes, the pattern of results was consistent for mothers and fathers: structural invariance testing indicated that mothers’ and fathers’ pathways did not differ in those models, and thus pathways could be constrained. For the PPVT outcome, for both parents there were (H1) significant associations from parenting stress to observed parental responsiveness; (H2) significant associations from observed parental responsiveness to PPVT; and (H3) observed parental responsiveness mediated the association from parenting stress to child PPVT (indirect effect). Similarly, for the measure of child prosocial behavior, for both parents there were (H1) significant associations from parenting stress to observed parental responsiveness; (H2) significant associations from observed parental responsiveness to child prosocial behavior; and (H3) observed parental responsiveness mediated the association from parenting stress to child prosocial behavior (indirect effect). Mothers and fathers did not differ in these patterns of associations.

Table 2.

Summary Comparing Patterns of Mother and Father Results

| Direct Effect |

Pathway A |

Pathway B |

Indirect Effect |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Outcome Measure | Stress ➔ Outcome | H1: Stress ➔ Responsiveness | H2: Responsiveness ➔ Outcome | H3: Responsiveness as Mediator |

| PPVT | --- | M, F | M, F | M, F |

| Prosocial Behavior | --- | M, F | M, F | M, F |

| Behavior Problems | M, F | M, F | M | --- |

Note: M denotes that the pathway was significant for mothers; F denotes that the pathway was significant for fathers. Dashed lines indicate a non-significant relationship for mothers and fathers.

However, for child behavior problems, although there were (H1) significant associations from mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress to parental responsiveness, there were (H2) significant associations from parental responsiveness to child behavior problems for mothers only. Furthermore, (H3) parental responsiveness did not mediate the association from parenting stress to child behavior problems (indirect effect) for either parent.

3.4. Robustness Checks

We conducted numerous robustness checks to examine the sensitivity of our results to model specification. All results from these checks are available upon request. First, because the BSF study stemmed from an RCT, we conducted a multiple-group analysis to determine whether our results differed based on treatment assignment (i.e., the treatment and control groups). Structural invariance testing indicated that all model pathways across treatment and control groups could be constrained to be equal. This suggests that the pathways estimated in our study were not moderated by treatment assignment. Second, we tested whether our results changed when accounting for the clustering by site location using the cluster option in Mplus. To note, although the full BSF sample spanned across eight sites, our restricted sample only included five sites, because measures of key study variables for our analyses were not obtained at every site, as described in the Methods section. Additionally, some sites had relatively small sample sizes (i.e., < 150) considering the number of parameters we were estimating. For the child PPVT model, all standardized coefficients remained the same after accounting for clustering, and the indirect effect’s p-value changed to < .001. For the child prosocial behavior and child behavior problems model, all standardized coefficients remained the same, except for (a) the p-value for the indirect effect for child prosocial behavior changed to <.001, and (b) the p-value from maternal responsiveness to child behavior problems changed to .085. Third, we re-ran the PPVT model utilizing FIML to estimate the same sample from our other models (i.e., N=1,173); none of the standardized coefficients or p-values changed.

Fourth, we re-ran all models but included the 36-month measures of maternal and paternal parenting stress to account for possible increases or decreases in parenting stress. This was conducted by including an autoregressive pathway between parenting stress at 15-months and parenting stress at 36-months, and then co-varying the 36-month parenting stress measures with the 36-month responsiveness measures. None of the standardized coefficients or p-values changed. Finally, because the alpha coefficient for parenting stress was low for both mothers and fathers, we conducted a post-hoc exploratory factor analysis with a promax rotation on the parenting stress items. The factor analysis indicated that the first and third items of the parenting stress scale (i.e., felt their children are harder to care for than most; felt they were giving up their lives to meet their child’s needs more than expected) loaded onto one factor, and the second and fourth items (i.e., the child did things that bothered them; how angry they felt with their children) loaded onto a different factor. Therefore, we ran all the models again, keeping all parenting stress items separate. We found that our initial results were only substantiated when utilizing the first and third items of the parenting stress scale. Therefore, this suggests that our results were primarily driven by parents feeling their children were harder to care for than most, and parents feeling they were giving up their lives to meet their children’s needs more than expected.

4.0. Discussion

The current study expands upon components of the family stress model by proposing that parenting stress can negatively influence children’s cognitive and prosocial outcomes via an observed measure of parental responsiveness. Few studies have examined these components of the family stress model using large, diverse samples of low-income parents. Additionally, using an observational measure of responsiveness allowed this study to overcome some of the biases inherent in self-report data. While dozens of studies have utilized observational measures of responsiveness among mothers only (Brady-Smith et al., 2013; Fuligni et al., 2013; Fuligni & Brooks-Gunn, 2013; O’Neal et al., 2017), few studies of this scale (i.e., consisting of over 1,100 families) have utilized observational data of both father-child and mother-child responsiveness among low-income parents. Data from both mothers and fathers allowed us to conduct dyadic analyses that examined the processes linking mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress to child outcomes (child cognitive development, child prosocial behavior, and child behavior problems), as well as to assess whether these associations differed between mothers and fathers.

There are several key findings of this study. First, the processes linking parenting stress, parental responsiveness, and child cognitive development and prosocial behavior appear to differ from the processes linking such parenting variables to child behavior problems (summarized in Table 2). Specifically, parental responsiveness did mediate the association between parenting stress and child cognitive development and prosocial behavior; however, parental responsiveness did not mediate the association between parenting stress and child behavior problems. Second, the associations between parenting stress, parental responsiveness, and child cognitive development and prosocial appear to be quite similar for mothers and fathers. However, mothers’ and fathers’ influence on child behavior problems differ, with mothers’ parenting stress and responsiveness being more strongly linked with child behavior problems that fathers’ parenting stress and responsiveness.

4.1. Parenting Stress, Observed Parental Responsiveness, and Child Outcomes

The results showing that mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress at 15-months was positively associated with observed parental responsiveness at 36-months aligns well with prior literature that suggests parenting stress can directly affect the quality of mother-child and father-child interactions (Belsky et al., 1996). The observational measure of responsiveness utilized in this study (i.e., two bags task) captures important dimensions of the parent-child relationship, including the quality of the relationship, parental positive regard toward the child, parental sensitivity, and parental detachment during the interaction (Fuligni & Brooks-Gunn, 2013). Thus, this study suggests that the experience of parenting stress makes it less likely that mothers and fathers would engage in positive interactions with their child. The association from parenting stress to parental responsiveness was similar for mothers and fathers in this study, who were living in highly economically disadvantaged circumstances and likely experienced high levels of parenting stress.

Among both mothers and fathers, parental responsiveness was positively associated with children’s cognitive development and prosocial behavior at 36-months. Again, these findings align with prior studies among mothers that show parental responsiveness is associated with child outcomes (Guajardo et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2013), including child cognitive abilities (Brady-Smith et al., 2013; Moreno et al., 2008). Results of this study showed that parental responsiveness mediated associations between parenting stress and child cognitive development and prosocial behavior. The behaviors that parents utilize when they are responsive to their child may role model prosocial behavior, thus encouraging their children to engage in similar behaviors. Responsive parenting also provides an environment in which children’s cognitive development is enhanced.

However, patterns of parental influence differed for the negative outcome of child behavior problems. Only mothers’ responsiveness was associated with lower child behavior problems, whereas fathers’ responsiveness was unrelated to child behavior problems. Further, mothers’ parenting stress was more strongly related to child behavior problems compared to fathers’. Although parental responsiveness played a mediating role in the associations of parenting stress to children’s cognitive development and prosocial behavior, this was not the case for child behavior problems: neither mothers’ nor fathers’ parental responsiveness was a mediator of parenting stress on child behavior problems. Overall, this pattern of findings may indicate that the parenting processes linked to positive outcomes (cognitive development, child prosocial behavior) differ in comparison to the processes associated with negative outcomes (child behavior problems).

4.2. Mother and Father Effects on Child Behavioral Outcomes

Whereas mothers’ and fathers’ patterns of influence were quite similar for the positive outcomes of child cognitive development and child prosocial behavior, mothers’ and fathers’ patterns of influence differed for the negative outcome of child behavior problems. In terms of structural invariance testing, mothers’ and fathers’ pathways predicting children’s cognitive development and child prosocial behavior could be constrained to be equal; however, mothers’ and fathers’ pathways predicting child behavior problems could not be constrained to be equal. Specifically, mothers’ parenting stress predicted child behavior problems more strongly than fathers’, and mothers’ responsiveness predicted child behavior problems while fathers’ responsiveness did not. This suggests that, on the whole, mothers’ parenting stress and responsiveness were more strongly related to child behavior problems than fathers’. This highlights the importance of researchers acknowledging the non-independence of mothers and fathers: in some cases, maternal and paternal parenting may contribute to children’s outcomes at a similar strength; in other cases, maternal parenting may contribute to specific child outcomes at a higher strength than paternal parenting, or vice versa. However, researchers will need to replicate existing analyses that involve mothers and fathers and agree upon how to best model dyadic data (for example, by following Kenny’s [2010] guidelines) in order to determine whether mothers’ and fathers’ parenting contributes to child outcomes differently.

Our results for the differing effects of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting on the development of child behavior problems is consistent with prior research. A number of studies have also found modest influence, or no influence, of fathers’ parenting behaviors on child behavior problems, particularly when mothers and fathers are modeled simultaneously in statistical analyses. For example, using Fragile Families and Child Well-being data, one study simultaneously examined mothers’ and fathers’ use of discipline and found that maternal and paternal parenting did not impact child outcomes in similar ways. Specifically, mothers’ spanking, but not fathers’ spanking, was associated with child behavior problems (Lee, Altshul, & Gershoff, 2015). Another study using Fragile Families and Child Well-being data investigated the associations of paternal anxiety and depression on child behavior problems and showed no significant associations of paternal mental health to child behavior problems (Meadows, McLanahan, & Brooks-Gunn, 2007). In a study that used BSF data (the same dataset as the current study) to examine the influence of mothers’ and fathers’ conflict behaviors on child outcomes, fathers’ reports of interparental conflict had no direct associations with child behavior problems, after accounting for maternal reports of interparental conflict (Lee, Pace, Lee, & Altschul, 2020). In sum, a number of studies—including the present study—suggest that mothers’ parenting behaviors may be more impactful than fathers’ parenting behaviors on children’s development of behavior problems. This is an important question for further research and replication.

Researchers have suggested that, because mothers spend more time in daily caregiving of young children than do fathers (Craig, 2006; Jones & Mosher, 2013), mothers may potentially exert a greater influence on child wellbeing than do fathers, by virtue of more considerable time spent caring for them. This may be particularly true for young children, such as the children in this study, who were age three and younger during data collection (Jones & Mosher, 2013). However, this study points to a limitation of this explanation, because results indicated that fathers’ influence was very similar to mothers’ influence for the positive outcomes of children’s cognitive development and child prosocial behavior. Thus, it would seem that time spent with the child cannot alone explain why mothers’ parenting behaviors, but less so fathers’ parenting behaviors, are associated with child behavior problems in particular.

4.3. Limitations

This study should be interpreted within the context of its limitations. Our sample consists of low-income parents who participated in an RCT of relationship education courses; therefore, our findings cannot be generalized to other populations. Along a similar vein, the parents in the sample self-selected into the study; therefore, their initial levels of parenting stress may not be random. Further, the majority of the families in our sample identified as Black, Hispanic, or “Other,” meaning that our sample is not racially representative of the U.S. as a whole. The study results must be interpreted in light of these selection bias issues.

Additionally, although part of our analyses were longitudinal, parental responsiveness and child outcomes were measured at the same time point; thus, we cannot conclude that parental responsiveness precedes child outcomes, and causal claims about this relationship should not be made. Further, child behavior problems and child prosocial behavior were both measured via maternal reports, meaning that these measures may be subject to social desirability bias or inaccurate reporting. Also, while parenting stress was measured utilizing a widely-used and validated scale in the literature, the internal consistency of the measure in our sample was much lower than desired. Results involving parenting stress should be replicated in future research. Also, future research should consider testing the validity and reliability of parenting stress scales among low-income parents.

4.4. Implications and Future Directions

The results of our study offer several theoretical and practical implications. In general, the findings of this study align with family stress theory. While the family stress model primarily focuses on how financial stress contributes to parenting behavior, this current study supports the proposition that parent-specific stressors can impact child outcomes through changes in the parent-child relationship. These results suggest that future studies with similar analytic samples may need to take parenting stress into account when studying parent-child interactions. Along a similar vein, clinicians that are helping families improve parental responsiveness and child outcomes may benefit from considering parenting stress.

Additionally, although our study cross-sectionally linked parent-child interactions with child outcomes, future studies should determine whether parent-child interactions impact child outcomes further into adolescence (Wang et al., 2013). Our study indicates that parent-child interactions may serve as a mechanism through which parenting stress impacts children’s wellbeing; therefore, future studies may benefit from testing parental responsiveness as a mechanism through which other external circumstances (e.g., financial stress, housing instability, unemployment) impact child outcomes.

Researchers may investigate whether interventions to reduce parenting stress among low-income families would improve parent-child interactions; alternatively, perhaps interventions that improve parent-child interactions may reduce parenting stress and improve children’s well-being. Importantly, researchers and interventionists should consider the influence of both mothers and fathers when attempting to understand the relationships between parenting stress, parental responsiveness, and child wellbeing.

5.0. Conclusion

Parenting stress impacts many families across the U.S., especially low-income families. The family stress model suggests that external parental stressors can influence parent-child interactions, which can then influence children’s outcomes. Overall, the study results are in concordance with the family stress model (Conger et al., 2000), and provide additional evidence that parental stressors impact parent-child interactions, which then impact child outcomes. Among a large, diverse sample of low-income families, we find that parenting stress is indirectly related to children’s cognitive development and child prosocial behavior through parental responsiveness. Although maternal and paternal parenting stress was found to be directly associated with child behavior problems, these relationships were not indirectly related to these outcomes through parental responsiveness. Patterns for mothers’ and fathers’ influence were largely similar for positive child outcomes (cognitive development and prosocial behavior), but differed when looking at the negative outcome of child behavior problems. Future studies should continue to examine how mothers and fathers contribute to child wellbeing and should strive to replicate the findings in this study among diverse samples using a fully longitudinal framework.

Highlights.

Mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress was associated with lower responsiveness

Responsiveness was associated with higher child cognitive and prosocial outcomes

Responsiveness mediated associations of parenting stress and positive child outcomes

Mothers and fathers had similar influence on child cognitive and prosocial outcomes

Mothers’ parenting had a greater impact on child behavior problems than fathers’

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (1R15HD091763–01) to Dr. Shawna J. Lee.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abidin RR (1995). Parenting stress index manual (3rd ed.). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Baker CE (2017). Father-son relationships in ethnically diverse families: Links to boys’ cognitive and social emotional development in preschool. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26, 2335–2345. 10.1007/s10826-017-0743-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Woodworth S, & Crnic K (1996). Trouble in the second year: Three questions about family interaction. Child Development, 67, 556–578. 10.2307/1131832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Hahn CS, & Haynes OM (2008). Maternal responsiveness to young children at three ages: Longitudinal analysis of a multidimensional, modular, and specific parenting construct. Developmental Psychology, 44, 867 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady-Smith C, Brooks-Gunn J, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Ispa JM, Fuligni AS, Chazan-Cohen R, & Fine MA (2013). Mother–infant interactions in Early Head Start: A person-oriented within-ethnic group approach. Parenting, 13, 27–43. 10.1080/15295192.2013.732430 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ, Volling BL, & Barr R (2018). Fathers are parents, too! Widening the lens of parenting for children’s development. Child Development Perspectives, 12, 152–157. 10.1111/cdep.12275 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Fine MA, Ispa J, Thornburg KR, Sharp E, & Wolfenstein M (2004). Understanding parenting stress among young, low-income African-American first-time mothers. Early Education and Development, 15, 265–282. 10.1207/s15566935eed1503_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry KE, Gerstein ED, & Ciciolla L (2019). Parenting stress and children’s behavior: Transactional models during Early Head Start. Journal of Family Psychology. Advance online publication 10.1037/fam0000574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coats EE, & Phares V (2019). Pathways linking nonresident father involvement and child outcomes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 1681–1694. 10.1207/s15374424jccp2104_12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conger KJ, Rueter MA, & Conger RD (2000). The role of economic pressure in the lives of parents and their adolescents: The family stress model In Crockett LJ & Silbereisen RJ (Eds.), Negotiating adolescence in times of social change (pp. 201–223). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, & Brody GH (2002). Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology, 38, 179–193. 10.1037//0012-1649.38.2.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CE, McLanahan SS, Meadows SO, & Brooks-Gunn J (2009). Family structure transitions and maternal parenting stress. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 558–574. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00619.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig L (2006). Does father care mean fathers share? A comparison of how mothers and fathers in intact families spend time with children. Gender and Society, 20, 259–281. 10.1177/0891243205285212 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, Gaze C, & Hoffman C (2005). Cumulative parenting stress across the preschool period: Relations to maternal parenting and child behaviour at age 5. Infant and Child Development, 14, 117–132. 10.1002/icd.384 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crnic K, & Ross E (2017). Parenting stress and parental efficacy In Deater-Deckard K & Panneton R (Eds.), Parental stress and early child development: Adaptive and maladaptive outcomes (pp. 263–284). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International; 10.1007/978-3-319-55376-4_11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dion M, Avellar S, & Clary E (2010). The Building Strong Families Project: Implementation of eight programs to strengthen unmarried parent families. Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research. [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz H, Black MM, Cox CE, Kerr MA, Litrownik AJ, Radhakrishna A, English DJ, Schneider MW, & Runyan DK (2001). Father involvement and children’s functioning at age 6 years: A multisite study. Child Maltreatment, 6, 300–309. 10.1177/1077559501006004003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, & Dunn DM (2007). Peabody picture vocabulary test (4th ed.). San Antonio, TX: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrle J, & Moore KA (1997). NSAF benchmarking measures of child and family well-being. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; NSAF Methodology; Report No. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Nguyen T, & Caspi A (1985). Linking family hardship to children’s lives. Child Development, 56, 361–375. 10.1007/978-3-662-02475-1_9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J, Bernd E, & Whiteman V (2007). Adolescent fathers’ parenting stress, social support, and involvement with infants. Journal of Research on Adolescents, 17, 1–22. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00510.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira T, Cadima J, Matias M, Vieira JM, Leal T, & Matos PM (2016). Preschool children’s prosocial behavior: The role of mother-child, father-child and teacher-child relationships. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 1829–1839. 10.1007/s10826-016-0369-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AS, & Brooks-Gunn J (2013). Mother–child interactions in Early Head Start: Age and ethnic differences in low-income dyads. Parenting, 13, 1–26. 10.1080/15295192.2013.732430 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AS, Brady-Smith C, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Bradley RH, Chazan-Cohen R, Boyce L, & Brooks-Gunn J (2013). Patterns of supportive mothering with 1-, 2-, and 3-year-olds by ethnicity in Early Head Start. Parenting, 13, 44–57. 10.1080/15295192.2013.732434 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guajardo NR, Snyder G, & Peterson R (2009). Relationships among parenting practices, parental stress, child behavior, and children’s social-cognitive development. Infant and Child Development, 18, 37–60. 10.1002/icd.578 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harper SE, & Fine MA (2006). The effects of involved nonresidential fathers’ distress, parenting behaviors, inter-parental conflict, and the quality of father-child relationships on children’s well-being. Fathering, 4, 286–311. 10.3149/fth.0403.286 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hershey A, Devaney B, Wood RG, & McConnell S (2014). Building Strong Families (BSF) project data collection, 2005–2008. United States. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research; 10.3886/ICPSR29781.v3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J, Obradovic J, Rasheed M, McCoy DC, Fink G, & Yousafzai A (2019). Maternal and paternal stimulation: Mediators of parenting intervention effects on preschoolers’ development. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 60, 105–118. 10.1016/j.appdev.2018.12.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J, & Mosher WD (2013). Fathers’ involvement with their children: United States, 2006–2010. National Health Statistics Reports, 71, 1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA (2010). Commentary: Dyadic analysis of family data. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 36, 630–633. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Landry SH, Smith KE, & Swank PR (2006). Responsive parenting: Establishing early foundations for social, communication, and independent problem-solving skills. Developmental Psychology, 42, 627–642. 10.1037/0012-1649.42.4.627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin SJ, & Otis M (2019). The relationship of child temperament, maternal parenting stress, and maternal child interaction and child health rating. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 36, 631–640. 10.1007/s10560-018-0587-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lau EYH, & Power TG (2019). Coparenting, parenting stress, and authoritative parenting among Hong Kong and Chinese mothers and fathers. Parenting: Science and Practice (advanced online publication). 10.1080/15295192.2019.1694831 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lechowicz ME, Jiang Y, Tully LA, Burn MT, Collins DA, Hawes DJ, Lenroot RK, Anderson V, Doyle FL, Piotrowska PJ, Frick PJ, Moul C, Kimonis ER, & Dadds MR (2018). Enhancing father engagement in parenting programs: Translating research into practice recommendations. Australian Psychologist, 54, 83–89. 10.1111/ap.12361 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Altshul I, & Gershoff ET (2015). Wait until your father gets home? Mothers’ and fathers’ spanking and development of child aggression. Children & Youth Services Review, 52, 158–166. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Pace GT, Lee JY, & Altschul I (2020). Parental relationship status as a moderator of the associations between mothers’ and fathers’ conflict behaviors and early child behavior problems. (Manuscript submitted for publication but not yet accepted). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Pace GT, Lee JY, & Knauer H (2018). The association of fathers’ parental warmth and parenting stress to child behavior outcomes. Children & Youth Services Review, 91, 1–10. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh B, & Milgrom J (2008). Risk factors for antenatal depression, postnatal depression and parenting stress. BMC Psychiatry, 8, 24 10.1186/1471-244X-8-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemelin J-P, Tarabulsy GM, & Provost MA (2006). Predicting preschool cognitive development from infant temperament, maternal sensitivity, and psychosocial risk. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 53, 779–806. 10.1353/mpq.2006.0038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC (1989) Socialization and development in a changing economy: The effect of parental job and income loss on children. American Psychologist, 44, 293–302. 10.1037/0003-066X.44.2.293 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC (1990). The impact of economic hardship on Black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development, 61, 311–346. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWayne C, Downer JT, Campos R, & Harris RD (2013). Father involvement during early childhood and its association with children’s early learning: A meta-analysis. Early Education and Development, 24, 989–922. 10.1080/10409289.2013.746932 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows SO, McLanahan SS, & Brooks-Gunn J (2007). Parental depression and anxiety and early childhood behavior problems across family types. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 1162–1177. [Google Scholar]

- Merrell KW (2002). Preschool and kindergarten behavior scales (2nd ed.). Austin, TX: PRO-ED. [Google Scholar]

- Mistry RS, Vandewater EA, Huston AC, McLoyd VC ( 2002). Economic well-being and children’s social adjustment: The role of family process in an ethnically diverse low-income sample. Child Development, 73, 935–951. 10.1111/1467-8624.00448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Brown PA, Brody GH, Cutrona CE, & Simons RL (2001). Racial discrimination as a moderator of the links among stress, maternal psychological functioning, and family relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 915–926. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00915.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2018). Mplus user’s guide. Eighth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Neece CL, Green SA, Baker BL (2012). Parenting stress and child behavior problems: A transactional relationship across time. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 117, 48–66. 10.1352/1944-7558-117.1.48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton EK, Laible D, Carlo G, & Steele JS (2014). Do sensitive parents foster kind children, or vice versa? Bidirectional influences between child behavior problems and parental sensitivity. Developmental Psychology, 50, 1808–1816. 10.1037/a0036495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nord C, Edwards B, Hilpert R, Branden L, Andreassen C, Elmore A, & West J (2004). Early childhood longitudinal study, birth cohort (ECLS-B): User’s manual for the ECLS-B nine-month restricted-use data file and electronic code book. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neal CR, Weston L, Brooks-Gunn J, Berlin LJ, & Atapattu R (2017). Maternal responsivity to infants in the “High Chair” assessment: Longitudinal relations with toddler outcomes in a diverse, low-income sample. Infant Behavior and Development, 47, 125–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelchat D, Bisson J, Bois C, & Saucier J-C. (2003). The effects of early relational antecedents and other factors on the parental sensitivity of mothers and fathers. Infant and Child Development, 27, 27–51. 10.1002/icd.335 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JL, & Zill N (1986). Marital disruption, parent-child relationships, and behavior problems in children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 48, 295–307. 10.2307/352397 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnet K, Mortelmans D, Wouters E, Van Leeuwen K, Bastaits K, & Pasteels I (2013). Parenting stress and marital relationship as determinants of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting. Personal Relationships, 20, 259–276. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2012.01404.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rholes WS, Simpson JA, & Friedman M (2006). Avoidant attachment and the experience of parenting. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 275–285. 10.1177/0146167205280910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, & Fraley RC (2008). A behavior-genetic study of parent quality, infant attachment security, and their covariation in a nationally representative sample. Developmental Psychology, 44, 831–839. 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, & Bolger N (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan JR (2016). Peabody picture vocabulary test In Couchenour D & Chrisman JK, (Eds.), The SAGE encyclopedia of contemporary early childhood education (pp. 979–980). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Tharner A, Luijk MPCM, van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Jaddoe VWV, Hofman A, Verhulst FC, & Tiemeier H (2012). Infant attachment, parenting stress, and child emotional and behavioral problems at age 3 years. Parenting: Science and Practice, 12, 261–281. 10.1080/15295192.2012.709150 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trautmann-Villalba P, Gschwendt M, Schmidt MH, & Laucht M (2006). Father-infant interaction patterns as precursors of children’s later externalizing behavior problems: A longitudinal study over 11 years. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256, 344–349. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-0642-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). The health and well-being of children: A portrait of states and the nation, 2011–2012. Rockville, MD: USDHHS; https://mchb.hrsa.gov/nsch/2011-12/health/childs-family/parental-stress.html [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Christ SL, Mills-Koonce WR, Garrett-Peters P, & Cox MJ (2013). Association between maternal sensitivity and externalizing behavior from preschool to adolescence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 34, 89–100. 10.1016/j.appdev.2012.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willford AP, Calkins SD, & Keane SP (2007). Predicting change in parenting stress across early childhood: Child and maternal factors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 251–263. 10.1007/s10802-006-9082-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood RG, Moore Q, Clarkwest A, & Killewald A (2014). The long-term effects of building strong families: A program for unmarried parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76, 446–463. 10.1111/jomf.12094 [DOI] [Google Scholar]