Abstract

Context and Objective

Posture-responsive and posture-unresponsive aldosterone-producing adenomas (APAs) account for approximately 40% and 60% of APAs, respectively. Somatic gene mutations have been recently reported to exist in approximately 90% of APAs. This study was designed to characterize the biochemical, histopathologic, and genetic properties of these 2 types of APA.

Methods

Plasma levels of aldosterone and hybrid steroids (18-oxocortisol and 18-hydroxycortisol) were measured by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Immunohistochemistry for CYP11B2 (aldosterone synthase) and CYP17A1 (17α-hydroxylase) and deoxyribonucleic acid sequencing (Sanger and next-generation sequencing) were performed on APA tissue collected from 23 posture-unresponsive and 17 posture-responsive APA patients.

Results

Patients with posture-unresponsive APA displayed higher (P < 0.01) levels of hybrid steroids, recumbent aldosterone and cortisol, larger (P < 0.01) zona fasciculata (ZF)-like tumors with higher (P < 0.01) expression of CYP17A1 (but not of CYP11B2) than patients with posture-responsive APA (most of which were not ZF-like). Of 40 studied APAs, 37 (92.5%) were found to harbor aldosterone-driving somatic mutations (KCNJ5 = 14 [35.0%], CACNA1D = 13 [32.5%], ATP1A1 = 8 [20.0%], and ATP2B3 = 2 [5.0%]), including 5 previously unreported mutations (3 in CACNA1D and 2 in ATP1A1). Notably, 64.7% (11/17) of posture-responsive APAs carried CACNA1D mutations, whereas 56.5% (13/23) of posture-unresponsive APAs harbored KCNJ5 mutations.

Conclusions

The elevated production of hybrid steroids by posture-unresponsive APAs may relate to their ZF-like tumor cell composition, resulting in expression of CYP17A1 (in addition to somatic gene mutation-driven CYP11B2 expression), thereby allowing production of cortisol, which acts as the substrate for CYP11B2-generated hybrid steroids.

Keywords: aldosterone-producing Adenoma, APA, posture responsiveness, hybrid steroids, immunohistochemistry, IHC, somatic gene mutations

Primary aldosteronism (PA) is the most common endocrine cause of hypertension with a prevalence approaching 5% to 13% in the hypertensive population (1-3). The overproduction of aldosterone in PA, caused by adenoma and/or hyperplasia of 1 or both adrenal glands, is relatively autonomous of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS). Unilateral aldosterone-producing adenoma (APA) and so-called bilateral adrenal hyperplasia (BAH; also known as idiopathic hyperaldosteronism) are the 2 major subtypes of PA, accounting for approximately 30% and 60% of all PA cases, respectively (4,5). The differentiation of PA subtype is critical, as unilateral (laparoscopic) adrenalectomy (ADX) improves and may even cure hypertension in patients with APA, whereas mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and amiloride have substantial beneficial effects on the control of hypertension in patients with BAH (6,7).

Besides the just described differentiation based on laterality, PA can also be divided into angiotensin II (AngII)-responsive and AngII-unresponsive forms according to the ability of aldosterone levels to increase after AngII infusion (no longer available in Australia for clinical research use) or upright posture (which is associated with activation of the RAS). In those with AngII-responsive forms of PA, including AngII-responsive APA and most cases of BAH (8-11), aldosterone has been observed to demonstrate normal responsiveness to upright posture (posture-responsive, defined as a rise in plasma aldosterone concentration of at least 50% 2 to 3 h after the assumption of upright posture above the basal level following overnight recumbency). In contrast, in those with AngII-unresponsive forms of PA, including AngII-unresponsive APA and familial hyperaldosteronism type I (FH-I), aldosterone demonstrates a lack of responsiveness to upright posture or even a fall (posture-unresponsive). It is likely that adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) assumes a dominant role over AngII in regulating aldosterone production in patients with posture (or AngII)-unresponsive forms of PA, because endogenous ACTH generally peaks around the early morning hours and then falls afterward when these posture studies are carried out (8). Further comparisons conducted by our Center in the 1990s revealed that posture (or AngII)-unresponsive APAs were predominately composed of adrenal zona fasciculata (ZF)-like cells and were associated with elevated urinary levels of hybrid steroids (18-hydroxycortisol [18-OHF] and 18-oxocortisol [18-oxoF]). In contrast, posture (or AngII)-responsive APAs mainly consisted of adrenal zona glomerulosa (ZG)-like or mixed ZG and ZF-like cell populations, both of which were associated with normal levels of hybrid steroids (12-16).

While initial reports suggested that somatic mutations in KCNJ5, CACNA1D, ATP1A1, ATP2B3, and CTNNB1 were present in approximately 60% of sporadic APAs (17-20), more recent studies using immunohistochemistry (IHC) to detect and target APA tissue expressing aldosterone synthase (CYP11B2) have shown that around 90% of APAs have mutations in 1 of these genes (21-23). Moreover, somatic mutations in CLCN2 (24) or CACNA1H (25) have also recently been identified in sporadic cases of APA, further expanding the spectrum of somatic gene mutations associated with APA. Because these genes (except for CTNNB1, which encodes β-catenin) encode ion channels/pumps in adrenal cell membranes, mutations within them result in dysfunctional cellular ion transport, which leads to Ca2+ influx and a rise in intracellular Ca2+ levels, which in turn activates CYP11B2 expression and aldosterone production. Among these genes, KCNJ5 mutations are the most prevalent, occurring in approximately 35% to 50% of APAs (26-29) (higher in Asian cohorts (30-32)]). Compared to patients with APAs that lack KCNJ5 mutations, patients with KCNJ5-mutated APAs are more often females and tend to be younger at diagnosis (probably due to their more florid PA phenotype) (33,34). Moreover, KCNJ5-mutated APAs are larger in size, have a higher proportion of ZF-like cells, and secrete higher levels of hybrid steroids than those without KCNJ5 mutations (35-38). Our Center previously reported that among 26 Australian APA patients who had undergone both posture stimulation testing and Sanger sequencing of KCNJ5, all 10 with somatic KCNJ5 mutations (G151R, n = 8; L168R, n = 2) were posture-unresponsive, compared with 6 of 16 without KCNJ5 mutations (39). This raises the possibility that KCNJ5 mutations are the genetic basis for the biochemical and morphological phenotype associated with the posture (or AngII)-unresponsive APAs, while APAs without KCNJ5 mutations are more likely to resemble and behave like posture (or AngII)-responsive APAs, as originally defined by Gordon et al (10-16).

To our knowledge, there are no reported studies comparing posture-responsive with posture-unresponsive APAs in terms of their peripheral hybrid steroid levels, expression of adrenal steroidogenic enzymes, and spectrum of somatic gene mutations. The current study, therefore, was designed to define the clinical, biochemical, histopathologic, and genetic differences between these two types of APA.

Methods

Study design and patients

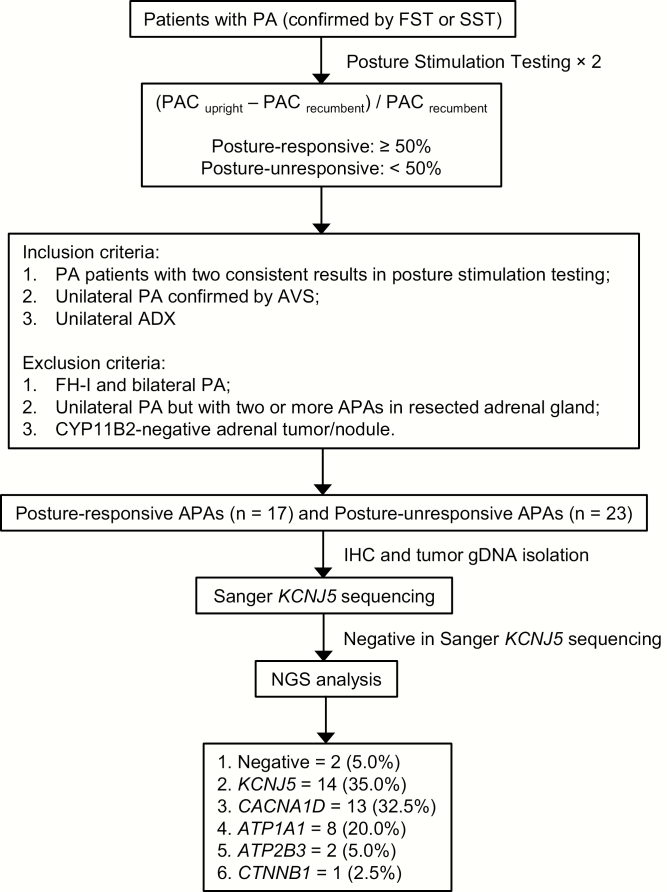

This study was approved by the Human Ethics Review Committees of the Princess Alexandra Hospital, the Greenslopes Private Hospital, and the University of Queensland (HREC/13/QPAH/232; SSA/13/QPAH/244). Among the total of 63 patients (21 females and 42 males) who underwent unilateral ADX in our Center from March 2016 to January 2019, 40 patients with unilateral APA (12 females and 28 males, age range: 24-69 years old) were recruited (posture-unresponsive, n = 23; posture-responsive, n = 17) according to the criteria shown in Fig. 1. The clinical characteristics of all recruited patients are displayed in Table 1. For assessing posture responsiveness, blood was collected at 7 am after overnight recumbency and at 10 am after 3-h upright posture (standing, sitting, or walking). Adrenal venous sampling (AVS) was performed in the morning with samples collected sequentially after ACTH stimulation (50 mcg/h infusion). Plasma concentrations of aldosterone (PAC), 18-oxoF, and 18-OHF were measured by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), while plasma concentrations of renin (DRC) and cortisol were measured by chemiluminescent immunoassay. Detailed descriptions of these assay methods and performance characteristics are provided in the online supplemental data at available at (40).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patient recruitment and study procedure.

Table 1.

Clinical and biochemical characteristics of 40 studied APA patients

| Characteristics | Posture-R APAs | Posture-U APAs | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 17) | (n = 23) | ||

| Pre-ADX | |||

| Age at ADX, yr | 49 (43–56) | 49 (33–54) | NS |

| Female, n (%) | 5 (29.4%) | 7 (30.4%) | NS |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.5 (28.3–33.2) | 30.9 (26.9–34.2) | NS |

| Known duration of HTN, months | 60 (23–200) | 72 (27–108) | NS |

| SBP, mmHg | 153 (147–162) | 151 (143–167) | NS |

| DBP, mmHg | 93 (88–97) | 91 (86–100) | NS |

| Number of anti-HTN drugs | 3 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | NS |

| Total DDD (anti-HTN) | 2.4 (1.6–3.4) | 2.2 (1.3–3.0) | NS |

| Recumbent PAC, pmol/L | 356.5 (270.8–459.0) | 941.0 (590.0–1880.0) | <0.01 |

| Recumbent DRC, mU/L | 2.0 (1.3–2.5) | 2.0 (1.0–2.8) | NS |

| Recumbent ARR, pmol/mU | 175.0 (140.1–276.1) | 531.0 (295.0–1396.3) | <0.01 |

| Recumbent cortisol, nmol/L | 272.0 (214.5–295.5) | 338.0 (301.0–427.0) | <0.01 |

| Upright PAC, pmol/L | 693.0 (514.0–976.5) # | 680.0 (532.0–972.5) # | NS |

| Upright DRC, mU/L | 4.0 (2.0–6.0) # | 3.0 (2.1–5.0) # | NS |

| Upright ARR, pmol/mU | 142.8 (111.2–314.1) | 175.3 (118–752.5) # | NS |

| Upright cortisol, nmol/L | 241.0 (201.5–268.0) | 240.0 (177.0–328.0) # | NS |

| Plasma 18-oxoF, nmol/L | 0.16 (0.08–0.29) | 0.85 (0.40–1.52) | <0.01 |

| Plasma 18-OHF, nmol/L | 1.72 (1.13–2.61) | 5.14 (3.18–8.90) | <0.01 |

| Lowest K+, mmol/L | 3.1 (2.8–3.3) | 2.8 (2.6–3.2) | NS |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 87 (76–107) | 79 (68–94) | NS |

| AVS (post-ACTH stimulation) | |||

| SI_LAV | 16.9 (14.8–19.7) | 19.8 (13.6–30.0) | NS |

| SI_RAV | 30.4 (15.0–39.9) | 34.4 (22.4–47.0) | NS |

| LI | 13.3 (6.4–22.2) | 20.3 (7.4–41.4) | NS |

| CSI | 0.5 (0.2–0.8) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | <0.05 |

| Dominate side in right, n (%) | 5 (29.4%) | 9 (39.1%) | NS |

| Nodule size (maximum diameter) | |||

| Adrenal CT, mm | 8.0 (0–11.0) | 16.0 (12.0–21.0) | <0.01 |

| Pathology, mm | 9.0 (8.0–11.5) | 19.0 (15.0–23.0) | <0.01 |

| CYP11B2 IHC score | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | NS |

| CYP17A1 IHC score | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | <0.01 |

| ZG-like APA, n (%) | 8 (47.1%) | 0 | <0.01 |

| ZF-like APA, n (%) | 3 (17.6%) | 20 (87.0%) | |

| ZG-ZF mixed APA, n (%) | 6 (35.3%) | 3 (13.0%) |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) or number (percentage). IHC scores are presented as mean ± SEM.

#, P < 0.01, for pairwise comparison between recumbent and upright positions within the same group.

SI = (cortisol in AV)/(cortisol in PV);

LI = (A/C ratio in dominant AV): (A/C ratio in non-dominant AV);

CSI = (A/C ratio in non-dominant AV): (A/C ratio in non-dominant PV).

Abbreviations: 17α-hydroxylase; 18-OHF, 18-hydroxycortisol; 18-oxoF, 18-oxocortisol; A/C ratio, aldosterone to cortisol ratio; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; ADX, adrenalectomy; APA, aldosterone-producing adenoma; ARR, aldosterone/renin ratio; AV, adrenal vein; AVS, adrenal venous sampling; BMI, body mass index; CSI, contralateral suppression index; CYP11B2, aldosterone synthase; CYP17A1, DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DDD, defined daily dose (all anti-HTN drugs); DRC, plasma direct renin concentration; HTN, hypertension; LI, lateralization index; NS, not significant (P > 0.05); PAC, plasma aldosterone concentration; posture-R, posture responsive; posture-U, posture unresponsive; PV, peripheral vein; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SI_LAV, selectivity index in left adrenal vein; SI_RAV, selectivity index in right adrenal vein; ZF, zona fasciculata; ZG, zona glomerulosa.

Immunohistochemistry

Resected adrenal tumor tissue samples were either frozen in O.C.T compound (frozen blocks, n = 33) or fixed in 10% (vol/vol) formaldehyde and embedded with paraffin (FFPE blocks, n = 7). Tissue blocks were cut into 7 μm serial sections for hematoxylin and eosin staining (slides 1 and 10), IHC staining (slides 2-3), and mutation analysis (slides 4-9). Cellular composition of APA tissues was determined by independent pathologists. IHC staining was performed using Dako EnVision® + Dual Link System-HRP (DAB+) kit (Dako) antibodies against aldosterone synthase (CYP11B2, mouse monoclonal clone 41-17B, 1:200, Millipore, MABS1251) and 17α-hydroxylase (CYP17A1, rabbit polyclone, 1:500, Sigma-Aldrich, HPA048533). The relative immunoreactivity of CYP11B2 and CYP17A1 was determined semiquantitatively by calculating the percentage of tissue area within the APA staining positively by IHC (using ImageJ software) (41,42) and was scored as undetectable (0, no expression), low (1, <30% expression), moderate (2, 30%-70% expression) and high (3, >70% expression).

DNA isolation

Genomic deoxyribonucleic acid (gDNA) was extracted using the AllPrep® DNA/RNA Micro Kit (QIAGEN, Cat#80284) and AllPrep® DNA/RNA FFPE Kit (QIAGEN, Cat#80234) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For each sample, unstained slides were used to collect tissues from CYP11B2-positive (as indicated by IHC) tumor regions (n = 40), CYP11B2-negative tumor regions (n = 3; 3 adrenal tumors had both CYP11B2-positive and CYP11B2-negative tumor regions), and adjacent normal adrenal (n = 40).

Detections of somatic gene mutations

For all tumor gDNA samples (n = 43), Sanger sequencing of KCNJ5 was initially performed (40). Template gDNA with the region covering major hotspots of KCNJ5 mutations was amplified using primers as follows: KCNJ5 forward 5’-GGACCATGTTGGCGACCAAGAGTG-3’, reverse 5’-GACAAACATGCACCCCACCATGAAG-3’ (43). For each polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification reaction, 20 ng of template gDNA was used. Bidirectional Sanger sequencing of the purified PCR product was performed using the BigDyeTM Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) on an Applied Biosystems 3730xl DNA sequencer. Tumor gDNA samples that were negative for KCNJ5 mutations by Sanger sequencing (n = 29) were subsequently subjected to next-generation sequencing (NGS) analysis. For NGS analysis, barcoded libraries were generated by multiplex PCR using the Ion AmpliSeq Library Kit 2.0 and a custom Ion Torrent AmpliSeq Panel (Thermo Fisher Scientific) that includes full coding regions of KCNJ5, CACNA1D, ATP1A1, ATP2B3, CACNA1H, and CLCN2 and oncogenic hotspots in CTNNB1 and GNAS as described previously (21,22).

Statistical analysis

Nonnormal distribution data are presented as median (interquartile range), while categorical data are presented as number (percentage). IHC scores are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. Independent samples Mann-Whitney U test and t-test were used to compare data between the posture-responsive and posture-unresponsive groups and between groups with different genotypes. Related samples Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare within-group data before and after posture stimulation testing and before and after ADX. Chi-square test was used to compare numbers and percentages. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Biochemical and histological comparisons between posture-responsive and posture-unresponsive APAs

Before ADX, median DRC increased (P < 0.01) in both groups after posture stimulation testing (Table 1), while median PAC increased from 356.5 to 693.0 pmol/L (P < 0.01) in the posture-responsive APA group but decreased from 941.0 to 680.0 pmol/L (P < 0.01) in the posture-unresponsive APA group. Patients with posture-unresponsive APA were observed to have higher (P < 0.01) plasma levels of recumbent PAC, recumbent cortisol, and upright hybrid steroids than patients with posture-responsive APA. Adrenal venous sampling results revealed that posture-unresponsive APA patients also displayed higher lateralization index (median 20.3 vs 13.3, not significant) and lower contralateral suppression index (CSI; median 0.2 vs 0.5, P < 0.05) than posture-responsive APA patients (results of adrenal/peripheral aldosterone and cortisol ratios in both the dominant and nondominant sides are provided in (40)).

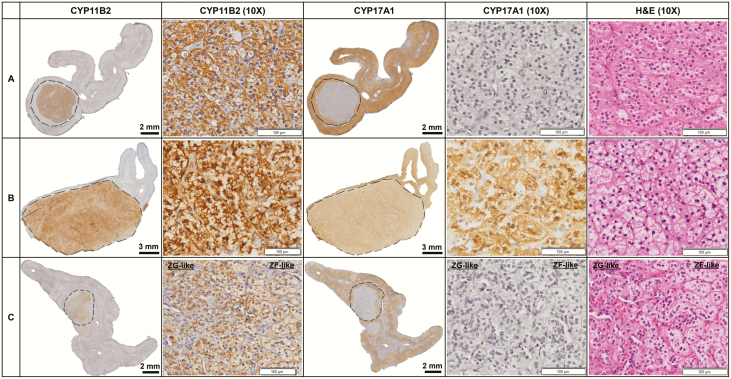

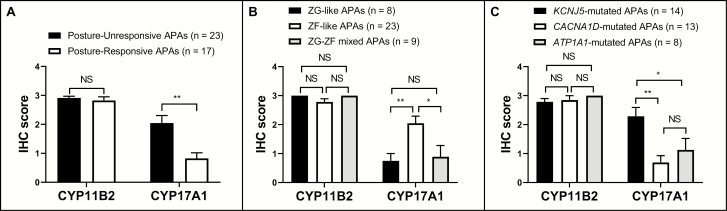

After ADX, plasma levels of aldosterone and hybrid steroids both decreased significantly (P < 0.01 or P < 0.05) in the 2 groups and no longer differed between the 2 groups (40). Patients with posture-unresponsive APA were found to have larger tumors than those with posture-responsive APA (median diameter: 19.0 vs 9.0 mm, P < 0.01). As shown in Fig. 2, the majority (20/23, 87.0%) of posture-unresponsive APAs displayed predominantly ZF-like cellular composition, whereas in posture-responsive APAs, ZG-like (8/17, 47.1%) and ZG-ZF mixed (6/17, 35.3%) cellular compositions were the most prevalent (14/17, 82.4%; P < 0.01). The expression of CYP11B2 was not significantly different between the 2 groups (mean IHC score: 2.9 vs 2.8), but posture-unresponsive APAs demonstrated higher expression of CYP17A1 than posture-responsive APAs (mean IHC score: 2.0 vs 0.8, P < 0.01) (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Representative histopathologic findings of posture-responsive and posture-unresponsive APAs.

Figure 3.

Immunoreactivity of CYP11B2 and CYP17A1 among different groups.

Somatic gene mutations in posture-responsive and posture-unresponsive APAs

Of 40 studied APAs, 37 (92.5%) were found to harbor aldosterone-driving somatic mutations (KCNJ5 = 14, 35.0%; CACNA1D = 13, 32.5%; ATP1A1 = 8, 20.0%; ATP2B3 = 2, 5.0% (40)), including 5 previously unreported mutations (3 in CACNA1D and 2 in ATP1A1). In the matched adjacent adrenals, there was no evidence of the variants that were detected in APA, confirming the variants are of somatic origin. The novel variants were also confirmed by Sanger sequencing (40). Notably, 64.7% (11/17) of posture-responsive APAs carried CACNA1D mutations, whereas 56.5% (13/23) of posture-unresponsive APAs harbored KCNJ5 mutations (P < 0.01). In addition, we also identified 1 unresponsive case (ZF-like, CYP11B2-positive, CYP17A1-positive) with a reported CTNNB1 mutation (c.C134T; p.S45F) (20,23).

Comparisons between APAs with different genotypes

As shown in Table 2, patients with KCNJ5 mutations were younger (median age at 34 years old) than patients with other mutations at the time of ADX, while patients with ATP1A1 mutations were older (median age at 57 years old). Patients with ATP1A1 mutations also had a longer (P < 0.01) duration of hypertension and were taking a higher (P < 0.05) defined daily dosage of anti-hypertensive drugs before ADX than patients with KCNJ5 or CACNA1D mutations.

Table 2.

Comparison of KCNJ5, CACNA1D, and ATP1A1 mutated APAs

| Characteristics | KCNJ5 | CACNA1D | ATP1A1 | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 14) | (n = 13) | (n = 8) | KCNJ5 vs. CACNA1D | KCNJ5 vs. ATP1A1 | CACNA1D vs. ATP1A1 | |

| Pre-ADX | ||||||

| Age at ADX, yr | 34 (30–52) | 47 (43–54) | 57 (51–62) | <0.05 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| BMI | 30.6 (24.0–33.1) | 30.5 (28.3–33.6) | 33.4 (29.9–41.8) | NS | NS | NS |

| Known duration of HTN, months | 53 (24–85) | 48 (23–159) | 210 (120–321) | NS | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Female, n (%) | 6 (42.9%) | 3 (23.1%) | 1 (12.5%) | NS | NS | NS |

| SBP, mmHg | 147 (138–168) | 153 (149–162) | 160 (148–171) | NS | NS | NS |

| DBP, mmHg | 92 (86–100) | 93 (89–97) | 91 (82–98) | NS | NS | NS |

| Number of anti-HTN drugs | 3 (1–3) | 2 (2, 3) | 3 (2–5) | NS | NS | NS |

| Total DDD (anti-HTN) | 2.0 (1.1–2.9) | 2.0 (1.3–2.5) | 4.0 (1.6–7.8) | NS | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| Recumbent PAC, pmol/L | 990.5 (494.3–1675.0) | 347.5 (269.8–426.3) | 771.0 (595.0–2462.5) | <0.01 | NS | <0.01 |

| Recumbent DRC, mU/L | 2.2 (0.9–2.8) | 2.0 (1.2–2.5) | 2.3 (1.3–4.5) | NS | NS | NS |

| Recumbent ARR, pmol/ mU | 419.2 (233.0–1828.2) | 178.2 (143.0–276.1) | 549.7 (219.7–1172.5) | <0.05 | NS | <0.05 |

| Recumbent cortisol, nmol/L | 356.5 (300.8–411.3) | 290.0 (253.0–321.5) | 283.5 (253.8–447.5) | NS | NS | NS |

| Upright PAC, pmol/L | 608.5 (472.5–878.6) # | 558.0 (500.8–867.0) # | 1387.5 (836.0–2328.8) | NS | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Upright DRC, mU/L | 3.8 (1.9–5.8) # | 3.5 (2.0–5.3) # | 3.3 (2.0–7.9) * | NS | NS | NS |

| Upright ARR, pmol/mU | 154.4 (100.0–492.0) # | 142.8 (123.3–314.0) | 462.5 (128.4–1039.5) | NS | NS | NS |

| Upright cortisol, nmol/L | 236.0 (176.5–300.3) # | 230.0 (201.5–244.0) * | 320.5 (198.8–390.0) | NS | NS | NS |

| Plasma 18-oxoF, nmol/L | 1.15 (0.70–2.21) | 0.10 (0.08–0.18) | 0.31 (0.19–1.25) | <0.01 | <0.05 | <0.01 |

| Plasma 18-OHF, nmol/L | 6.24 (3.64–8.64) | 1.53 (1.07–2.08) | 3.93 (2.14–8.02) | <0.01 | NS | <0.01 |

| Lowest K+, mmol/L | 2.8 (2.6–3.0) | 3.1 (2.8–3.3) | 3.0 (2.7–3.2) | NS | NS | NS |

| Posture-R, n (%) | 1 (7.1%) | 11 (84.6%) | 3 (37.5%) | <0.01 | NS | <0.05 |

| Posture-U, n (%) | 13 (92.9%) | 2 (15.4%) | 5 (62.5%) | |||

| AVS (Post-ACTH stimulation) | ||||||

| LI | 34.5 (9.4–60.1) | 9.5 (5.8–13.6) | 27.8 (9.1–38.3) | <0.01 | NS | NS |

| CSI | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 0.5 (0.4–0.8) | 0.2 (0.1–0.5) | <0.01 | NS | <0.01 |

| Right ADX, n (%) | 6 (42.9%) | 4 (30.8%) | 1 (12.5%) | NS | NS | NS |

| Size of adenoma, mm | 20.0 (16.5–21.5) | 9.0 (7.5–10.0) | 15.0 (12.0–19.8) | <0.01 | NS | <0.01 |

| CYP11B2 IHC score | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.0 | NS | NS | NS |

| CYP17A1 IHC score | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | <0.01 | <0.05 | NS |

| ZG-like APA, n (%) | 0 | 5 (38.5%) | 2 (25.0%) | <0.01 | <0.05 | NS |

| ZF-like APA, n (%) | 13 (92.9%) | 3 (23.0%) | 4 (50.0%) | |||

| ZG-ZF mixed APA, n (%) | 1 (7.1%) | 5 (38.5%) | 2 (25.0%) |

P values are for pairwise comparison between recumbent and upright positions within the same group.

Abbreviation: NS, not significant (P > 0.05)

*P < 0.05.

# P < 0.01.

Compared to patients with CACNA1D mutations, patients with KCNJ5 mutations had higher (P < 0.01) plasma levels of recumbent PAC and upright hybrid steroids. Patients with KCNJ5 mutations also displayed higher lateralization index (34.5 vs 9.5, P < 0.01) and lower CSI (0.2 vs 0.5, P < 0.01) than patients with CACNA1D mutations. Moreover, KCNJ5-mutated APAs were larger than CACNA1D-mutated APAs (median diameter 20.0 vs 9.0 mm, P < 0.01), and 92.9% (13/14) of KCNJ5-mutated APAs consisted of ZF-like cells, whereas CACNA1D-mutated APAs were predominantly (10/13, 76.9%) comprised of ZG-like (5/13, 38.5%) or ZG-ZF mixed cells (5/13, 38.5%). Although the expression of CYP11B2 was not significantly different between the 2 groups (Fig. 3), KCNJ5-mutated APAs showed higher levels of CYP17A1 than CACNA1D-mutated APAs (mean IHC score: 2.3 vs 0.7, P < 0.01).

In patients with ATP1A1 mutations, recumbent and upright PAC and hybrid steroid levels were higher (P < 0.01) than that in the patients with CACNA1D mutations (Table 2). Tumors were also larger in the ATP1A1-mutated group than the CACNA1D-mutated group (median diameter 15.0 vs 9.0 mm, P < 0.01), but there was no significant difference between the 2 groups in terms of their IHC scores or cellular composition. When compared to patients with KCNJ5 mutations, patients with ATP1A1 mutations displayed lower levels of hybrid steroids (P < 0.05 for 18-oxoF) but higher levels of upright PAC (P < 0.01). Although no significant difference was observed between the 2 groups in terms of their tumor size and the expression of CYP11B2, KCNJ5-mutated APAs demonstrated higher percentage of ZF-like tumors (92.9% vs 50.0%, P < 0.05) and higher expression of CYP17A1 (mean IHC score: 2.3 vs 1.1, P < 0.05) than ATP1A1-mutated APAs (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The current study is the first to compare the characteristics of posture-responsive and posture-unresponsive APAs in terms of their peripheral hybrid steroid levels (measured by LC-MS/MS), CYP11B2/CYP17A1 IHC staining, and spectrum of somatic gene mutations. Our results have reconfirmed that, consistent with our Center’s previous reports (10-16), posture-unresponsive APAs have higher hybrid steroid levels and predominantly consist of ZF-like cells, while posture-responsive APAs have lower hybrid steroid levels and are mainly comprised of ZG-like or ZG-ZF mixed cells. As a result of this study, we also demonstrated that (i) compared to posture-responsive APAs, posture-unresponsive APAs had higher (P < 0.01) recumbent levels of PAC and cortisol, lower (P < 0.05) CSI, larger (P < 0.01) tumors, and higher (P < 0.01) tumor expression of CYP17A1 and (ii) posture-responsive APAs more frequently had CACNA1D mutations (11/17, 64.7%), whereas posture-unresponsive APAs were more likely to harbor KCNJ5 mutations (13/23, 56.5%; P < 0.01). ATP1A1 mutations ranked second within both the posture-responsive (3/17, 17.6%) and posture-unresponsive (5/23, 21.7%) APA groups.

The posture stimulation test was initially thought to be helpful in distinguishing APA from BAH, as aldosterone in BAH patients usually showed normal responsiveness to upright posture, whereas in most patients with APA, aldosterone displayed absence or reversal of such responsiveness (44-48). However, subsequent studies revealed that in approximately 30% of patients with APA, aldosterone levels responded to upright posture (49-52), indicating that posture-responsiveness lacked reliability as a means of excluding APA. With imaging studies such as adrenal computed tomography also having poor discriminatory ability, AVS remains the only reliable means of differentiating unilateral, surgically correctable forms of PA from bilateral forms. In normal subjects and patients with posture (or AngII)-responsive forms of PA, the proposed mechanisms by which assuming upright posture increases plasma aldosterone include (i) the rise in renin associated with sequestration of 600 to1000 mL blood into the lower limbs, which leads to reduced venous return, decreased renal perfusion, and increased sympathetic output (to prevent blood pressure falling and syncope) with activation of beta-adrenoceptors on renal juxtaglomerular cells (53,54), and (ii) reduced metabolic clearance of aldosterone by the liver due to reduced hepatic blood flow (8). A number of factors may contribute to the increase of aldosterone seen in posture (or AngII)-responsive APA, including (i) the smaller size of the APA lesion and (ii) the greater expression of AngII type 1 (AT1) receptors in the APA. In the current study, posture-responsive APAs were much smaller than posture-unresponsive APA patients, raising the possibility that the former may have a greater area of “normal” adrenal ZG which is capable of responding to the activation of the RAS. However, we believe this is an unlikely explanation as we did not observe greater CYP11B2 expression within the ZG area in removed adrenals from posture-responsive APA patients than that from posture-unresponsive APA patients. In addition, it is known that the expression of AT1 receptors is greater in human adrenal ZG cells (than in ZF cells (55)) and in ZG-like APAs (than in ZF-like APAs (35)). Chen et al reported that messenger ribonucleic acid levels of AT1 receptors correlated inversely with the percentage of ZF-like cells within the APA, and messenger ribonucleic acid levels of AT1 receptors in posture-responsive APAs (ZG-like) were 2.4-fold higher than that in posture-unresponsive APAs (ZF-like) (56). In our current study, 82.4% of posture-responsive APAs had ZG-like or ZG-ZF mixed cellular composition, which may have contributed to them being more sensitive to AngII (due to the greater expression of AT1 receptors within their tumors).

Recently, a study on BAH (another AngII-responsive form of PA) revealed that subcapsular aldosterone-producing cell clusters (APCCs) may be the major source of aldosterone excess in BAH rather than the previously proposed diffuse hyperplasia of adrenal ZG cells (57). All 15 studied adrenals from patients with bilateral PA were observed to harbor at least 1 APCC and/or micro-APA, while only 4/15 cases showed diffuse hyperplasia of the adrenal ZG with positive CYP11B2 staining. Interestingly, NGS analysis on 99 gDNA samples isolated from APCCs and micro-APA tissues demonstrated that CACNA1D mutations were the most prevalent (n = 57, 57.6%), whereas KCNJ5 mutation was detected in only 1 micro-APA (n = 1, 1.0%). APCCs have been reported (58) to be common in normal adrenals or in adjacent nontumorous portions of adrenals containing an APA. Unlike posture (or AngII)-unresponsive APA, APCCs are histopathologically characterized by showing predominantly ZG-like cellular composition with IHC staining positive for CYP11B2 but negative for CYP11B1 (11β-hydroxylase) and CYP17A1. An earlier study on 42 normal adrenals from kidney donors found that the transcriptome of APCCs was most similar to ZG cells (with less similarity to ZF cells) but with enhanced capacity to produce aldosterone, in that CYP11B2 expression was higher in APCCs compared with that in the ZG (59). Moreover, somatic mutations were identified in 8 of 23 studied APCCs, and CACNA1D mutations were again the most frequent (with no KCNJ5 mutations detected). Therefore, BAH (or, more precisely multiple, APCCs) and posture-responsive APA seem to share common characteristics: (i) both are AngII-responsive forms of PA; (ii) aldosterone-producing lesions in both are smaller (compared to posture-unresponsive APA) and are mainly comprised of ZG-like cells with positive CYP11B2 staining but generally negative CYP17A1 staining; and (iii) unlike posture-unresponsive APA (KCNJ5 mutations >> CACNA1D mutations), both BAH and posture-responsive APA are more likely to harbor somatic mutations in CACNA1D (>> KCNJ5).

In the current study, the median CSI was significantly higher in posture-responsive than posture-unresponsive APA patients. Our Center previously reported that following unilateral ADX, patients with AngII-responsive APA demonstrated a lower cure rate of hypertension than patients with AngII-unresponsive APA (70% vs 39%; P < 0.05) (60). These observations raise the possibility that the contralateral adrenal in patients with AngII (or posture)-responsive APA may be producing aldosterone autonomously, in relatively small amounts so as not to prevent lateralization on AVS, but enough to result in CSIs that are higher and post-ADX cure rates that are lower than those with AngII (or posture)-unresponsive APA. Could this be genetically based? Patients with CACNA1D-mutated APA (which comprised nearly two-thirds of posture-responsive APAs in this study) also demonstrated higher CSIs than those with KCNJ5-mutated APA (comprising over half of posture-unresponsive APAs), as well as higher contralateral adrenal/peripheral aldosterone ratios (40). It is possible that the APCCs are more prevalent within the adrenal cortices (both ipsilateral and contralateral to the APA) of these patients, perhaps because of a general predisposition to the development of somatic CACNA1D mutations in adrenal ZG cells and because their persistent in the contralateral gland following ADX predisposes them to mild, ongoing autonomous aldosterone overproduction.

As early as the 1980s, hybrid steroid levels were observed to be higher in patients with FH-I (another AngII-unresponsive form of PA, in which aldosterone is mainly regulated by ACTH) than in patients with BAH or APA (61-64). Lifton et al in 1992 elucidated that the genetic defect of FH-I is a “hybrid gene,” which is composed of regulatory sequences derived from CYP11B1 at its 5’ end and coding sequences derived from CYP11B2 at its 3’ end (65). Physiologically, CYP11B2, which possesses both 18-hydroxylase (catalyzing corticosterone to generate 18-hydroxycorticosterone) and 18-oxidase (catalyzing 18-hydroxycorticosterone to generate aldosterone) activities (66), is expressed only in ZG cells (67). By contrast, CYP11B1 and CYP17A1, the 2 key enzymes required for cortisol synthesis, are mainly expressed in ZF cells. In patients with FH-I, because the hybrid gene is expressed throughout all adrenocortical layers (68), the normal adrenocortical functional zonation is breached, resulting in ZF cells being capable of producing not only cortisol but also aldosterone (because of the coding sequences of CYP11B2). Furthermore, cortisol, which is normally “protected” by the functional zonation against the effects of CYP11B2, is now exposed to CYP11B2’s 18-hydroxylase (catalyzing cortisol to generate 18-OHF) and 18-oxidase (catalyzing 18-OHF to generate 18-oxoF) activities, thereby resulting in excessive production of hybrid steroids (69,70). In our current study, plasma hybrid steroids decreased significantly after ADX in both posture-responsive and posture-unresponsive groups (and were no longer different between the 2 groups after ADX), indicating that APA is the source of hybrid steroid production. At present, the basis for excessive production of hybrid steroids in posture-unresponsive APA is still unknown, but our results imply that it might be associated with the histopathologic and genetic characterization of APA. We speculate that the excessive production of hybrid steroids in posture-unresponsive APAs may occur because they strongly express not only CYP11B2 (due to aldosterone-driving somatic gene mutations, such as KCNJ5) but also CYP17A1 (a feature of adrenal ZF cells), thereby allowing production not only of aldosterone but also of cortisol, which in turn acts as the substrate for the generation of hybrid steroids. The observation that patients with posture-unresponsive APA displayed higher (P < 0.01) aldosterone and cortisol levels in the recumbent position than posture-responsive APA patients is also consistent with their ZF-like histology and consequent preferential regulation by ACTH, as endogenous levels of ACTH peak around 7 am (71,72) (which is when the recumbent samples were collected).

In the current study, although the expression of CYP11B2 did not differ significantly among three groups classified by cellular composition, ZF-like APAs (n = 23, 20 were posture-unresponsive) displayed higher (P < 0.01 or P < 0.05) expression of CYP17A1 (Fig. 3) and higher (P < 0.01 or P < 0.05) plasma hybrid steroid levels (40) than ZG-like (n = 8, all were posture-responsive) or ZG-ZF mixed (n = 9, 6 were posture-responsive) APAs. Our findings in posture-unresponsive APAs, which mostly had ZF-like cellular composition, somatic KCNJ5 mutations, and excessive production of hybrid steroids, are also reminiscent of those in the first reported family (1 father and 2 daughters) with familial hyperaldosteronism type III (17,73,74). These patients demonstrated (i) early-onset, severe hypertension associated with marked hyperaldosteronism and hypokalemia, which was resistant to aggressive antihypertensive therapy, thus requiring bilateral ADX to control; (ii) extremely high excretion of urinary hybrid steroids (much higher than that in FH-I); (iii) markedly enlarged adrenal glands with diffuse hyperplasia of ZF; and (iv) germline mutations in the KCNJ5. Gomez-Sanchez et al later in 2016 performed triple immunofluorescence on resected adrenals from two daughters of the previously mentioned family and found that CYP11B2 was expressed sporadically throughout their adrenal cortex, in addition to relatively frequent expression of CYP17A1 but less so of CYP11B1 (75).

Consistent with our findings (Table 2), Williams et al reported that patients with APAs harboring KCNJ5 mutations had higher peripheral plasma 18-oxoF and 18-OHF levels (also measured by LC-MS/MS) than those with CACNA1D or ATP1A1 mutations or APAs without mutations detected (37). Tezuka et al recently also reported that patients with KCNJ5-mutated APAs had higher peripheral plasma 18-oxoF levels (also measured by LC-MS/MS) than those without KCNJ5 mutations (38). In our current study, the prevalence of somatic KCNJ5 mutations (35.0%) is slightly lower than that in previous reports (around 50% (34,76)), but this may be due to the lower percentage of female patients (who have a higher prevalence of KCNJ5 mutations than men (21,34)) in our study cohort. However, consistent with previous studies (18,21,34,76,77), KCNJ5 mutations were still more prevalent in females within our study, whereas CACNA1D mutations and ATP1A1 mutations were more prevalent in males.

There are several limitations of our current study: (i) by NGS analysis, 5 previously unreported (to our knowledge) mutations were identified, including 3 in CACNA1D (c.G2978T, c.T3452C, and co-existence of c.T2240C and c.A2261G) and 2 in ATP1A1 (c.2877_2888del and c.2874_2882del). Although these 5 novel variants are quite close to the domains recurrently mutated in APA (supporting their potential pathogenicity) (27,78), in vitro functional experiments would be necessary in the future to validate their effects on aldosterone production, and (ii) the molecular mechanisms leading to a higher prevalence of CACNA1D mutations in posture-responsive APAs and higher prevalence of KCNJ5 mutations in posture-unresponsive APAs remains to be defined. Comparisons of transcriptome profiling between these 2 types of APAs are warranted and could provide clues on the underlying mechanisms.

In conclusion, the current study demonstrated that posture-responsive APAs are characterized by smaller non-ZF-like tumors, lower expression of CYP17A1, and predominantly CACNA1D mutations, whereas posture-unresponsive APAs are associated with higher levels of hybrid steroids, recumbent aldosterone and cortisol, larger ZF-like tumors, higher expression of CYP17A1, and predominantly KCNJ5 mutations. The excessive production of hybrid steroids by posture-unresponsive APAs may relate to their ZF-like tumor cellular composition, resulting in the expression of CYP17A1 (in addition to somatic gene mutation-driven CYP11B2 expression), thereby allowing production of cortisol, which acts as the substrate for CYP11B2-generated hybrid steroids.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Celso E. Gomez-Sanchez (Division of Endocrinology, University of Mississippi Medical Centre, Jackson, MI, US) for the generous gift of purified 18-oxocortisol reagent, and hypertension nurses Diane Cowley at the Princess Alexandra Hospital and Cynthia Kogovsek at the Greenslopes Private Hospital for their assistance in sample collection and retrieval of medical records. The authors also thank Nolan Bick and Amy R. Blinder at the University of Michigan for their technical assistance.

Financial support: This work was funded by the 2017 Metro South Health SERTA (Study, Education and Research Trust Account) Research Support Scheme (Queensland Government) and the Irene Patricia Hunt Memorial Hypertension Research Fund. This work was also in part supported by grants from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK106618 to W.E. Rainey) and American Heart Association (17SDG33660447 to K. Nanba).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- 18-OHF

18-hydroxycortisol

- 18-oxoF

18-oxocortisol

- ACTH

adrenocorticotrophic hormone

- ADX

adrenalectomy

- APA

aldosterone-producing adenoma

- ATP1A1

gene encoding ATPase Na+ / K+ transporting subunit alpha 1

- ATP2B3

gene encoding ATPase plasma membrane Ca2+ transporting 3

- AVS

adrenal venous sampling

- CACNA1D

gene encoding Ca2+ voltage-gated channel subunit alpha 1 D

- CACNA1H

gene encoding Ca2+ voltage-gated channel subunit alpha 1 H

- CLCN2

gene encoding voltage-gated ClC-2 chloride channel

- CSI

contralateral suppression index

- CTNNB1

gene encoding beta-catenin

- CYP11B2

aldosterone synthase

- CYP17A1

17α-hydroxylase

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- KCNJ5

gene encoding K+ inward-rectifying channel subfamily J member 5

- NGS

next-generation sequencing

- PA

primary aldosteronism

- NS

not significant (P > 0.05)

- RAS

renin-angiotensin system

- ZF

zona fasciculata

- ZG

zona glomerulosa

Additional Information

Disclosure: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.

References

- 1. Rossi GP, Bernini G, Caliumi C, et al. ; PAPY Study Investigators . A prospective study of the prevalence of primary aldosteronism in 1,125 hypertensive patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(11):2293-2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nishikawa T, Saito J, Omura M. Prevalence of primary aldosteronism: should we screen for primary aldosteronism before treating hypertensive patients with medication? Endocr J. 2007;54(4):487-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hannemann A, Wallaschofski H. Prevalence of primary aldosteronism in patient’s cohorts and in population-based studies–a review of the current literature. Horm Metab Res. 2012;44(3):157-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mulatero P, Stowasser M, Loh KC, et al. Increased diagnosis of primary aldosteronism, including surgically correctable forms, in centers from five continents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(3):1045-1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Young WF. Primary aldosteronism: renaissance of a syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2007;66(5):607-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stowasser M, Gordon RD. Primary aldosteronism: careful investigation is essential and rewarding. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;217(1-2):33-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Funder JW, Carey RM, Mantero F, et al. The management of primary aldosteronism: case detection, diagnosis, and treatment: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(5):1889-1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stowasser M, Gordon RD. Primary aldosteronism: changing definitions and new concepts of physiology and pathophysiology both inside and outside the kidney. Physiol Rev. 2016;96(4):1327-1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ganguly A, Dowdy AJ, Luetscher JA, Melada GA. Anomalous postural response of plasma aldosterone concentration in patients with aldosterone-producing adrenal adenoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1973;36(2):401-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gordon RD, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Hamlet SM, Tunny TJ, Klemm SA. Angiotensin-responsive aldosterone-producing adenoma masquerades as idiopathic hyperaldosteronism (IHA: adrenal hyperplasia) or low-renin essential hypertension. J Hypertens Suppl. 1987;5(5):S103-S106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gordon RD, Hamlet SM, Tunny TJ, Klemm SA. Aldosterone-producing adenomas responsive to angiotensin pose problems in diagnosis. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1987;14(3):175-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hamlet SM, Gordon RD, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Tunny TJ, Klemm SA. Adrenal transitional zone steroids, 18-oxo and 18-hydroxycortisol, useful in the diagnosis of primary aldosteronism, are ACTH-dependent. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1988;15(4):317-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tunny TJ, Gordon RD, Klemm SA, Cohn D. Histological and biochemical distinctiveness of atypical aldosterone-producing adenomas responsive to upright posture and angiotensin. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1991;34(5):363-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tunny TJ, Klemm SA, Stowasser M, Gordon RD. Angiotensin-responsive aldosterone-producing adenomas: postoperative disappearance of aldosterone response to angiotensin. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1993;20(5):306-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gordon RD, Stowasser M, Klemm SA, Tunny TJ. Primary aldosteronism–some genetic, morphological, and biochemical aspects of subtypes. Steroids. 1995;60(1):35-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stowasser M, Bachmann AW, Tunny TJ, Gordon RD. Production of 18-oxo-cortisol in subtypes of primary aldosteronism. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1996;23(6-7):591-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Choi M, Scholl UI, Yue P, et al. K+ channel mutations in adrenal aldosterone-producing adenomas and hereditary hypertension. Science. 2011;331(6018):768-772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beuschlein F, Boulkroun S, Osswald A, et al. Somatic mutations in ATP1A1 and ATP2B3 lead to aldosterone-producing adenomas and secondary hypertension. Nat Genet. 2013;45(4):440-4, 444e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Scholl UI, Goh G, Stölting G, et al. Somatic and germline CACNA1D calcium channel mutations in aldosterone-producing adenomas and primary aldosteronism. Nat Genet. 2013;45(9):1050-1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Åkerström T, Maharjan R, Sven Willenberg H, et al. Activating mutations in CTNNB1 in aldosterone producing adenomas. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nanba K, Omata K, Else T, et al. Targeted molecular characterization of aldosterone-producing adenomas in white Americans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(10):3869-3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nanba K, Omata K, Gomez-Sanchez CE, et al. Genetic characteristics of aldosterone-producing adenomas in blacks. Hypertension. 2019;73(4):885-892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wu VC, Wang SM, Chueh SJ, et al. The prevalence of CTNNB1 mutations in primary aldosteronism and consequences for clinical outcomes. Sci Rep. 2017;7:39121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dutta RK, Arnesen T, Heie A, et al. A somatic mutation in CLCN2 identified in a sporadic aldosterone-producing adenoma. Eur J Endocrinol. 2019;181(5):K37-K41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nanba K, Blinder AR, Rege J, Hattangady NG, Else T, Liu CJ, et al. Somatic CACNA1H mutation as a cause of aldosterone-producing adenoma. Hypertension. 2020;75:645-649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Åkerström T, Crona J, Delgado Verdugo A, et al. Comprehensive re-sequencing of adrenal aldosterone producing lesions reveal three somatic mutations near the KCNJ5 potassium channel selectivity filter. PloS One. 2012;7(7):e41926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fernandes-Rosa FL, Williams TA, Riester A, et al. Genetic spectrum and clinical correlates of somatic mutations in aldosterone-producing adenoma. Hypertension. 2014;64(2):354-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lenzini L, Rossitto G, Maiolino G, Letizia C, Funder JW, Rossi GP. A meta-analysis of somatic KCNJ5 K(+) channel mutations in 1636 patients with an aldosterone-producing adenoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(8):E1089-E1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dutta RK, Söderkvist P, Gimm O. Genetics of primary hyperaldosteronism. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2016;23(10):R437-R454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zheng FF, Zhu LM, Nie AF, et al. Clinical characteristics of somatic mutations in Chinese patients with aldosterone-producing adenoma. Hypertension. 2015;65(3):622-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Okamura T, Nakajima Y, Katano-Toki A, et al. Characteristics of Japanese aldosterone-producing adenomas with KCNJ5 mutations. Endocr J. 2017;64(1):39-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Warachit W, Atikankul T, Houngngam N, Sunthornyothin S. Prevalence of somatic KCNJ5 mutations in thai patients with aldosterone-producing adrenal adenomas. J Endocr Soc. 2018;2(10):1137-1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Boulkroun S, Beuschlein F, Rossi GP, et al. Prevalence, clinical, and molecular correlates of KCNJ5 mutations in primary aldosteronism. Hypertension. 2012;59(3):592-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Williams TA, Lenders JW, Burrello J, Beuschlein F, Reincke M. KCNJ5 Mutations: sex, salt and selection. Horm Metab Res. 2015;47(13):953-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Azizan EA, Lam BY, Newhouse SJ, et al. Microarray, qPCR, and KCNJ5 sequencing of aldosterone-producing adenomas reveal differences in genotype and phenotype between zona glomerulosa- and zona fasciculata-like tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(5):E819-E829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Monticone S, Castellano I, Versace K, et al. Immunohistochemical, genetic and clinical characterization of sporadic aldosterone-producing adenomas. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;411:146-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Williams TA, Peitzsch M, Dietz AS, et al. Genotype-specific steroid profiles associated with aldosterone-producing adenomas. Hypertension. 2016;67(1):139-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tezuka Y, Yamazaki Y, Kitada M, et al. 18-oxocortisol synthesis in aldosterone-producing adrenocortical adenoma and significance of KCNJ5 mutation status. Hypertension. 2019;73(6):1283-1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Azizan EA, Murthy M, Stowasser M, et al. Somatic mutations affecting the selectivity filter of KCNJ5 are frequent in 2 large unselected collections of adrenal aldosteronomas. Hypertension. 2012;59(3):587-591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Guo Z, Nanba K, Udager A, McWhinney BC, Ungerer JPJ, Wolley M, et al. Data from: biochemical, histopathologic, and genetic characterization of posture responsive and unresponsive APAs. Harvard Dataverse2020. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/UEWB2P. Deposited 26 May 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41. Nakamura Y, Maekawa T, Felizola SJ, et al. Adrenal CYP11B1/2 expression in primary aldosteronism: immunohistochemical analysis using novel monoclonal antibodies. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;392(1-2):73-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tan GC, Negro G, Pinggera A, et al. Aldosterone-producing adenomas: histopathology-genotype correlation and identification of a novel CACNA1D mutation. Hypertension. 2017;70(1):129-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nanba K, Omata K, Tomlins SA, et al. Double adrenocortical adenomas harboring independent KCNJ5 and PRKACA somatic mutations. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;175(2):K1-K6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ganguly A, Melada GA, Luetscher JA, Dowdy AJ. Control of plasma aldosterone in primary aldosteronism: distinction between adenoma and hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1973;37(5):765-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schambelan M, Brust NL, Chang BC, Slater KL, Biglieri EG. Circadian rhythm and effect of posture on plasma aldosterone concentration in primary aldosteronism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1976;43(1):115-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Biglieri EG. Effect of posture on the plasma concentrations of aldosterone in hypertension and primary hyperaldosteronism. Nephron. 1979;23(2-3):112-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Irony I, Kater CE, Biglieri EG, Shackleton CH. Correctable subsets of primary aldosteronism. Primary adrenal hyperplasia and renin responsive adenoma. Am J Hypertens. 1990;3(7):576-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fontes RG, Kater CE, Biglieri EG, Irony I. Reassessment of the predictive value of the postural stimulation test in primary aldosteronism. Am J Hypertens. 1991;4(9):786-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nomura K, Toraya S, Horiba N, Ujihara M, Aiba M, Demura H. Plasma aldosterone response to upright posture and angiotensin II infusion in aldosterone-producing adenoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;75(1):323-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Toraya S, Nomura K, Kono A, et al. Characteristics of aldosterone-producing adenoma responsive to upright posture. Endocr J. 1995;42(4):481-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Phillips JL, Walther MM, Pezzullo JC, et al. Predictive value of preoperative tests in discriminating bilateral adrenal hyperplasia from an aldosterone-producing adrenal adenoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(12):4526-4533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Espiner EA, Ross DG, Yandle TG, Richards AM, Hunt PJ. Predicting surgically remedial primary aldosteronism: role of adrenal scanning, posture testing, and adrenal vein sampling. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(8):3637-3644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cohen EL, Rovner DR, Conn JW. Postural augmentation of plasma renin activity. Importance in diagnosis of renovascular hypertension. JAMA. 1966;197(12):973-978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cohen EL, Conn JW, Rovner DR. Postural augmentation of plasma renin activity and aldosterone excretion in normal people. J Clin Invest. 1967;46(3):418-428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Breault L, Lehoux JG, Gallo-Payet N. Angiotensin II receptors in the human adrenal gland. Endocr Res. 1996;22(4):355-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chen YM, Wu KD, Hu-Tsai MI, Chu JS, Lai MK, Hsieh BS. Differential expression of type 1 angiotensin II receptor mRNA and aldosterone responsiveness to angiotensin in aldosterone-producing adenoma. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;152(1-2):47-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Omata K, Satoh F, Morimoto R, et al. Cellular and genetic causes of idiopathic hyperaldosteronism. Hypertension. 2018;72(4):874-880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nishimoto K, Nakagawa K, Li D, et al. Adrenocortical zonation in humans under normal and pathological conditions. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(5):2296-2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nishimoto K, Tomlins SA, Kuick R, et al. Aldosterone-stimulating somatic gene mutations are common in normal adrenal glands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(33):E4591-E4599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Stowasser M, Klemm SA, Tunny TJ, Storie WJ, Rutherford JC, Gordon RD. Response to unilateral adrenalectomy for aldosterone-producing adenoma: effect of potassium levels and angiotensin responsiveness. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1994;21(4):319-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chu MD, Ulick S. Isolation and identification of 18-hydroxycortisol from the urine of patients with primary aldosteronism. J Biol Chem. 1982;257(5):2218-2224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ulick S, Chu MD. Hypersecretion of a new corticosteroid, 18-hydroxycortisol in two types of adrenocortical hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens A. 1982;4(9-10):1771-1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gomez-Sanchez CE, Montgomery M, Ganguly A, et al. Elevated urinary excretion of 18-oxocortisol in glucocorticoid-suppressible aldosteronism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984;59(5): 1022-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mosso L, Gómez-Sánchez CE, Foecking MF, Fardella C. Serum 18-hydroxycortisol in primary aldosteronism, hypertension, and normotensives. Hypertension. 2001;38(3 Pt 2):688-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lifton RP, Dluhy RG, Powers M, et al. A chimaeric 11 beta-hydroxylase/aldosterone synthase gene causes glucocorticoid-remediable aldosteronism and human hypertension. Nature. 1992;355(6357):262-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kawamoto T, Mitsuuchi Y, Toda K, et al. Role of steroid 11 beta-hydroxylase and steroid 18-hydroxylase in the biosynthesis of glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(4):1458-1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gomez-Sanchez CE, Gomez-Sanchez EP. Immunohistochemistry of the adrenal in primary aldosteronism. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23(3):242-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Pascoe L, Jeunemaitre X, Lebrethon MC, et al. Glucocorticoid-suppressible hyperaldosteronism and adrenal tumors occurring in a single French pedigree. J Clin Invest. 1995;96(5):2236-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Stowasser M, Bachmann AW, Jonsson JR, Tunny TJ, Klemm SA, Gordon RD. Hybrid gene or hybrid steroids in the detection and screening for familial hyperaldosteronism type I. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1995;22(6-7):444-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Stowasser M, Gordon RD. Familial hyperaldosteronism. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;78(3):215-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Krishnan KR, Ritchie JC, Saunders W, Wilson W, Nemeroff CB, Carroll BJ. Nocturnal and early morning secretion of ACTH and cortisol in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 1990;28(1):47-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Gudmundsson A, Carnes M. Pulsatile adrenocorticotropic hormone: an overview. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41(3):342-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Geller DS, Zhang J, Wisgerhof MV, Shackleton C, Kashgarian M, Lifton RP. A novel form of human mendelian hypertension featuring nonglucocorticoid-remediable aldosteronism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(8):3117-3123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Mulatero P. A new form of hereditary primary aldosteronism: familial hyperaldosteronism type III. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(8):2972-2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gomez-Sanchez CE, Qi X, Gomez-Sanchez EP, Sasano H, Bohlen MO, Wisgerhof M. Disordered zonal and cellular CYP11B2 enzyme expression in familial hyperaldosteronism type 3. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017;439:74-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Stowasser M. Primary aldosteronism and potassium channel mutations. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2013;20(3):170-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Azizan EA, Poulsen H, Tuluc P, et al. Somatic mutations in ATP1A1 and CACNA1D underlie a common subtype of adrenal hypertension. Nat Genet. 2013;45(9):1055-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Åkerström T, Willenberg HS, Cupisti K, et al. Novel somatic mutations and distinct molecular signature in aldosterone-producing adenomas. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2015;22(5):735-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]