Abstract

The characteristics of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have primarily been described in hospitalized adults. Characterization of COVID-19 in ambulatory care is needed for a better understanding of its evolving epidemiology. Our aim is to provide a description of the demographics, comorbidities, clinical presentation, and social factors in confirmed SARS-CoV-2-positive non-hospitalized adults. We conducted a retrospective medical record review of 208 confirmed SARS-CoV-2-positive patients treated in a COVID-19 virtual outpatient management clinic established in an academic health system in Georgia. The mean age was 47.8 (range 21–88) and 69.2% were female. By race/ethnicity, 49.5% were non-Hispanic African American, 25.5% other/unknown, 22.6% non-Hispanic white, and 2.4% Hispanic. Nearly 70% had at least one preexisting medical condition. The most common presenting symptoms were cough (75.5%), loss of smell or taste (63%), headache (62%), and body aches (54.3%). Physician or advanced practice provider assessed symptom severity ranged from 51.9% mild, 30.3% moderate, and 1.4% severe. Only eight reported limitations to home care (3.8%), 55.3% had a caregiver available, and 93.3% reported initiating self-isolation. Care needs were met for 83.2%. Our results suggest the demographic and clinical characteristics of COVID-19 illness in non-hospitalized adults differ considerably from hospitalized patients and warrant greater awareness of risk among younger and healthier individuals and consideration of testing and recommending self-isolation for a wider spectrum of clinical symptoms by clinicians. Social factors may also influence the efficacy of preventive strategies and allocation of resources toward the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Non-hospitalized, Outpatient, Telemedicine, Characteristics, Comorbidities

Introduction

The first case of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and its associated clinical disease coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was reported in the United States (US) in January 2020 1. As of May 13, 2020, over 1.36 million subsequent US cases have been confirmed, resulting in over 82, 000 deaths 2. The characteristics of patients with COVID-19 have been detailed in a limited but rapidly growing literature of hospitalized patients. Reports from China 3, 4, Italy 5, and globally 6have found incidence and case fatality to be higher in older patients and those with pre-existing comorbid conditions. Studies from the US have similarly found higher population-based rates of COVID-19-related hospitalizations among older adults and those with underlying medical conditions 7. Additionally, US-based hospitalization rates have shown over-representation of non-Hispanic black patients 8. However, hospitalized patients with COVID-19 have been estimated to be less than 30% of total cases 4, 5. Seroprevalence data suggests far greater numbers of SARS-CoV-2 exposure in the ambulatory population 9. To date, little is known about the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with COVID-19 managed in the outpatient setting.

Similarly, the presenting symptoms of COVID-19 have been detailed among hospitalized patients 3, 10–12, but scant information is available about the spectrum and severity of clinical symptoms among patients suitable for outpatient management 13–15. Characterizing symptoms among non-hospitalized patients may guide more effective screening strategies 16. Social and behavioral factors, such as limitations to self-care, availability of a caregiver, and practice of home isolation among non-hospitalized patients, have also not been described but are critical for understanding clinical outcomes, risk of complications, and the epidemiology of COVID-19. Our aim is to begin to fill the current gap in knowledge about outpatients with COVID-19 by presenting detailed demographic, clinical, and social characteristics of 208 non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients followed by a virtual outpatient management clinic in the Atlanta metropolitan area.

Methods

Study Setting and Population

The study was conducted within the Emory Healthcare Network, the largest academic health system in Georgia (primarily serving the greater Atlanta metropolitan area). As of May 14, 2020, the state of Georgia ranks 10th in the prevalence of COVID-19 cases in the US 2. In March 2020, Emory Healthcare created a virtual outpatient management clinic (VOMC) for COVID-19 patients. The aim was to provide proactive care and support to non-hospitalized patients and reduce in-person care escalation and within-health system viral transmission. Patients referred to the VOMC had confirmed positive results for SARS-CoV-2 ribonucleic acid (RNA) by polymerase chain reaction testing of a nasopharyngeal sample performed at an Emory Healthcare Network location. Testing was available by appointment following assessment by a nurse managed triage protocol. Due to limited supply of testing kits during the study time period, testing was restricted based on symptom severity and risk of complications and prioritized to healthcare employees. Patients were offered management through the VOMC at the time of test result notification.

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective medical record review using data collected in the electronic health record (Cerner, North Kansas City, MO) from the baseline evaluation of patients managed through the VOMC between March 24, 2020, and April 10, 2020. The baseline visit was performed via a secured videoconference or telephone visit with one of the physicians or advanced practice providers at the VOMC. We used descriptive statistics for each of the reported variables using StataSE 14 software (College Station, TX) 17. This was a quality improvement study that met criteria for determination of non-human subject research by the Emory Institutional Review Board (IRB).

The data was structured by a medical record template that included fields for patient demographics, comorbid medical conditions, symptoms (description, course, severity, and duration), social factors (including self-care limitations, caregiver availability, isolation practices, and contact exposure), and a clinical assessment of risk for complications based on an internally developed guideline utilizing age, comorbid medical conditions, symptom severity, course of illness, and social factors. Patients were excluded from the analysis if they were missing demographic information (n = 2), if data did not pull correctly from the electronic health record (n = 1), or if they had a prior hospitalization for COVID-19 (n = 7).

Results

Demographic and Risk Exposure Summary

The 208 patients seen in the VOMC between March 24, 2020, and April 10, 2020, received testing between March 12, 2020, and April 9, 2020. The referring screening clinics tested 2766 patients for SARS-CoV-2 between March 12, 2020, and April 9, 2020, of whom 817 (29.5%) were positive. After exclusion criteria were applied, 208 (25.5%) COVID-19-positive patients were included in the study population. The mean age was 47.8 (SD 15.1) years, with nearly a quarter (24.5%) between the ages of 19 to 34 and 87.5% younger than 65 years (Table 1). The patients included more women (69.2%) than men (30.8%) and a greater proportion were non-Hispanic African American (49.5%) than non-Hispanic white (22.6%), Hispanic (2.4%), or other/unknown (25.5%). English was the primary language spoken by 67.8%. Most did not travel outside Georgia for 21 days prior to baseline evaluation (85.2%), and more than half did not have contact with a person known or suspected to be positive for COVID-19 (52.9% and 56.7%, respectively) (Table 1). Of those with known contact with a confirmed COVID-19-positive individual, the most common place of exposure was through work (26.4%) rather than home (8.7%) or in the community (3.4%). In our patients, since testing was preferentially offered to healthcare workers, a high percentage of those exposed through work (56.5%) were employed in a clinical setting.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of COVID-19 VOMC patients

| Characteristics | No. (%) of patients |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age, mean (SD) (range) | 47.8(15.1)[21–88] |

| 19–24 | 6 (2.9) |

| 25–34 | 45 (21.6) |

| 35–44 | 33 (15.9) |

| 45–54 | 46 (22.1) |

| 55–64 | 52 (25.0) |

| 65–74 | 18 (8.7) |

| ≥ 75 | 8 (3.8) |

| Sex | |

| Women | 144 (69.2) |

| Men | 64 (30.8) |

| Race | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 47(22.6) |

| Non-Hispanic Black or African American | 103 (49.5) |

| Hispanic | 5 (2.4) |

| Other/unknown | 53 (25.5) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 60 (28.8) |

| Married | 71 (34.1) |

| Divorced, widowed, separated | 12 (5.8) |

| Other/unknown | 65 (31.3) |

| Primary language spoken | |

| English | 141(67.8) |

| Other/unknown | 67(32.2) |

| COVID-19 information | |

| Location of testing | |

| Emory outpatient screening site | 151(72.6) |

| Emergency department | 23(11.1) |

| Other/unknown | 34(16.3) |

| Travel outside Georgia in the last 21 days | |

| No | 177(85.1) |

| Yes: domestic | 14(6.7) |

| Yes: unknown location | 4(2.4) |

| Unknown travel | 12(5.8) |

| Known contact with confirmed positive | |

| No | 110(52.9) |

| Yes: family/household member | 18(8.7) |

| Yes: community | 7(3.4) |

| Yes: non-clinical work setting | 19(9.1) |

| Yes: clinical work setting | 36(17.3) |

| Unknown | 18(8.7) |

| Known contact with suspected positive | |

| No | 118(56.7) |

| Yes: family/household member | 9(4.3) |

| Yes: community | 6(2.9) |

| Yes: non-clinical work setting | 9(4.3) |

| Yes: clinical work setting | 24(11.5) |

| Unknown | 42(20.2) |

N = 208 patients seen in the Emory Healthcare COVID-19 Positive Virtual Outpatient Management Clinic 3/24/2020–4/10/2020

Comorbidities

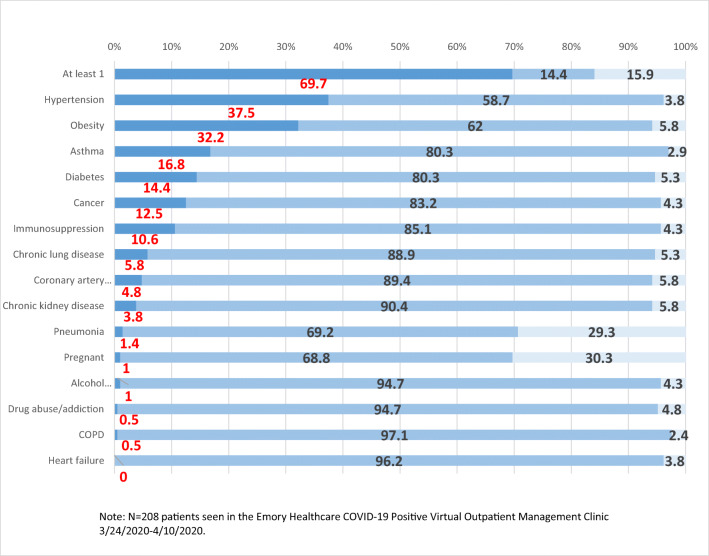

In this population of non-hospitalized adults with COVID-19, almost 70% reported at least one preexisting medical condition. In those reporting any preexisting medical condition, the most common were hypertension (37.5%), obesity with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 (32.2%), asthma (16.8%), and diabetes mellitus (14.4%) (Fig. 1 and Appendix Table 4). Of note, hypertension and BMI < 40 kg/m2 are not considered high risk conditions 18. Other preexisting medical conditions included cancer (12.5%), immunosuppression (10.6%), chronic lung disease (5.8%), coronary arterial disease (4.8%), and chronic kidney disease (3.8%).

Fig. 1.

Comorbidities of COVID-19 VOMC patients. Percentage with comorbidity (x-axis). Type of comorbidity (y-axis). Color key: Yes/No/Unknown

Table 4.

Comorbidities of COVID-19 VOMC patients

| Condition | No. (%) of patients |

|---|---|

| Any condition | |

| None of these | 30 (14.4) |

| At least 1 of these | 145 (69.7) |

| Unknown | 33 (15.9) |

| Chronic lung disease | |

| No | 185 (88.9) |

| Yes | 12 (5.8) |

| Unknown | 11 (5.3) |

| Asthma | |

| No | 167 (80.3) |

| Yes | 35 (16.8) |

| Unknown | 6 (2.9) |

| COPD | |

| No | 202 (97.1) |

| Yes | 1 (0.5) |

| Unknown | 5 (2.4) |

| Diabetes | |

| No | 167 (80.3) |

| Yes | 30 (14.4) |

| Unknown | 11 (5.3) |

| Chronic kidney disease | |

| No | 188 (90.4) |

| Yes | 8 (3.8) |

| Unknown | 12 (5.8) |

| Immunosuppression | |

| No | 177 (85.1) |

| Yes | 22 (10.6) |

| Unknown | 9 (4.3) |

| Hypertension | |

| No | 122 (58.7) |

| Yes | 78 (37.5) |

| Unknown | 8 (3.8) |

| Coronary arterial disease | |

| No | 186 (89.4) |

| Yes | 10 (4.8) |

| Unknown | 12 (5.8) |

| Heart failure | |

| No | 200 (96.2) |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) |

| Unknown | 8 (3.8) |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30) | |

| No | 129 (62.0) |

| Yes | 67 (32.2) |

| Unknown | 12 (5.8) |

| Alcohol abuse/addiction | |

| No | 197 (94.7) |

| Yes | 2 (1.0) |

| Unknown | 9 (4.3) |

| Drug abuse/addiction | |

| No | 197 (94.7) |

| Yes | 1 (0.5) |

| Unknown | 10 (4.8) |

| Cancer | |

| No | 173 (83.2) |

| Yes | 26 (12.5) |

| Unknown | 9 (4.3) |

| Pneumonia | |

| No | 144 (69.2) |

| Yes | 3 (1.4) |

| Unknown | 61 (29.3) |

| Pregnancy | |

| No | 142 (68.3) |

| Yes | 2 (1.0) |

| N/A | 64 (30.8) |

N = 208 patients seen in the Emory Healthcare COVID-19 Positive Virtual Outpatient Management Clinic 3/24/2020–4/10/2020

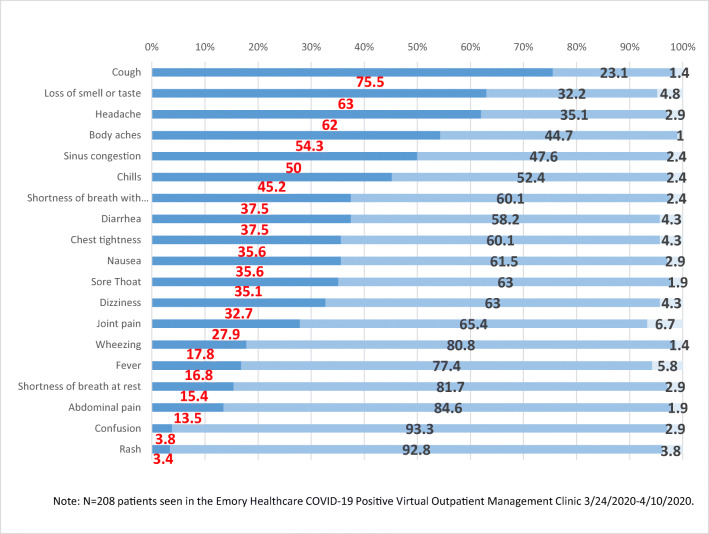

Symptoms and Severity

The most common presenting symptoms were cough (75.5%), loss of smell or taste (63%), headache (62%), and body aches (54.3%) (Fig. 2 and Appendix Table 5). Only 16.8% reported a fever but 45.2% experienced chills. Upper respiratory symptoms (sinus congestion 50%, sore throat 35.1%) and gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea 35.6%, diarrhea 37.5%, abdominal pain 13.5%) were common. Dizziness (32.7%), joint pains (27.9%), chest tightness (35.6%), shortness of breath at rest (15.4%), confusion (3.8%), and rash (3.4%) were also reported. Most patients rated their symptoms as mild (51.9%) and improving (58.7%) (Table 2). At the time of evaluation, the symptoms reported to have lasted the longest in duration were cough (mean 8.9 days, SD 5.8), sinus congestion (mean 8.4 days, SD 5.9), and loss of smell or taste (mean 7.1 days, SD 3.5). All other symptoms were reported to have resolved within 1 week. The percentage of patients without any symptoms was 10.1%.

Fig. 2.

Clinical symptoms of COVID-19 VOMC patients. Percentage with symptom (x-axis). Type of symptom (y-axis). Color key: Yes/No/Unknown

Table 2.

Risk assessment factors of COVID-19 VOMC patients

| Factor | No. (%) of patients |

|---|---|

| Age > 60 | |

| No | 160 (76.9) |

| Yes | 48 (23.1) |

| Underlying pertinent medical condition per clinician judgment | |

| No | 88 (42.3) |

| Yes | 120 (57.7) |

| Immunosuppression | |

| No | 187 (89.9) |

| Yes | 21 (10.1) |

| Inadequate care available | |

| No | 200 (96.2) |

| Yes | 8 (3.8) |

| Severity of symptoms | |

| None | 21 (10.1) |

| Mild | 108(51.9) |

| Moderate | 63(30.3) |

| Severe | 3(1.4) |

| Unknown | 13(6.3) |

| Symptom course | |

| Improving | 122(58.7) |

| Stable | 51(24.5) |

| Worsening | 14(6.7) |

| Unknown | 21(10.1) |

| Care needs can be adequately met | |

| No | 4(1.9) |

| Yes | 173(83.2) |

| Unknown | 31(14.9) |

| Risk for medical complications | |

| Low risk | 94(45.2) |

| Medium risk | 77(37.0) |

| High risk | 37(17.8) |

| Overall risk for complications (based on age, medical, and social factors) | |

| Low risk (Tier 1) | 95(45.7) |

| Medium risk (Tier 2) | 77(37.0) |

| High risk (Tier 3) | 36(17.3) |

N = 208 patients seen in the Emory Healthcare COVID-19 Positive Virtual Outpatient Management Clinic 3/24/2020–4/10/2020

The risk for medical complications assessed at the time of baseline evaluation was low for 45.2% of patients, medium for 37%, and high for 17.8%. The overall risk of complications, based on an internally created guideline that used age, social factors, underlying medical condition, and illness severity, was assessed by the intake medical provider to be low in 45.7%, medium in 37%, and high in 17.3% of patients (Table 2).

Social Characteristics

While most people (96.2%) did not have a limitation to home care, such as a restriction due to mobility, memory, mental health, socioeconomics, food availability, or other causes, only slightly more than a half (55.3%) had a caregiver available (Table 3). Caregivers were most often a significant other (22.5%) or alternative family member (28.8%). Most (91.4%) lived with one or more household members, with a quarter (25.5%) living with 4 or more people. Nearly a fourth of household members (22.1%) had an underlying high-risk medical condition. Self-isolation was reported by 93.3% of patients, with the majority initiating self-isolation either before (63%) or upon testing (20.2%). During baseline evaluation, fewer than five patients (< 2.4%) were assessed to be inappropriate for outpatient management and 83.2% had their care needs adequately met per clinical judgment.

Table 3.

Social background of COVID-19 VOMC patients

| Characteristics | No. (%) of patients |

|---|---|

| Limitations to home care | |

| None | 200 (96.2) |

| At least 1 identified | 8 (3.8) |

| Caregiver available | |

| No | 68 (32.7) |

| Yes | 115 (55.3) |

| Significant other | 47 (22.6) |

| Other family member | 60 (28.8) |

| Friend | 6 (2.9) |

| Unknown | 25 (12.0) |

| Number of family/contacts living in same residence | |

| None | 5 (2.4) |

| 1 | 38 (18.3) |

| 2 | 59 (28.4) |

| 3 | 40 (19.2) |

| ≥ 4 | 53 (25.5) |

| Unknown | 13 (6.3) |

| Household members with high-risk medical conditions | |

| No | 141 (67.8) |

| Yes | 46 (22.1) |

| Unknown | 21 (10.1) |

| Isolation | |

| Yes: prior to testing | 131 (63.0) |

| Yes: upon testing | 42 (20.2) |

| Yes: prior to notification of status | 11 (5.3) |

| Yes: upon notification of status | 10 (4.8) |

| Unknown | 14 (6.7) |

N = 208 patients seen in the Emory Healthcare COVID-19 Positive Virtual Outpatient Management Clinic 3/24/2020–4/10/2020

Discussion

Characterization of COVID-19 patients has thus far been primarily limited to hospitalized patients. Our results suggest that demographic and clinical characteristics of COVID-19 may differ in non-hospitalized patients. Hospitalized patients in the US have been mostly older adults, with median age 60 years or higher, with underlying medical conditions, in up to 94% of cases when non-high-risk conditions have been included 7, 10. In contrast, 87.5% of patients in our outpatient population were younger than 65 years old and 30.3% did not have an underlying medical condition, with the inclusion of non-high risk conditions 18. With over 70% of those with COVID-19 illness managed outside the hospital setting 4, 5, our findings raise the possibility that the risk of severe illness may be higher in medically vulnerable older people while the prevalence of mild and moderate COVID-19 illness may be higher in younger, healthier individuals. The demographic and clinical characteristics of our patients reinforce the need for all adults, regardless of age or underlying medical condition, to consider themselves at risk for COVID-19 illness. Additionally, prior studies have shown higher rates of hospitalization among men and African Americans 7, 8. The higher prevalence of comorbidities among African-Americans may contribute to the disproportionate number of cases and mortality, with higher obesity trends alone among African-Americans having been associated with increased mortality in COVID-19 patients 19. In our non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients, however, most were female (69.2%) and African Americans were not over-represented relative to the population demographics of the Atlanta metropolitan area (49.5% in study versus 51.8% city of Atlanta 20). Further investigation is needed to understand the risk associated with gender and race/ethnicity across the continuum of COVID-19 illness.

The most common signs and symptoms of COVID-19 illness, present in more than half of hospitalized patients, have included cough, fever, and dyspnea 7, 12. In our non-hospitalized patients, 75.5% had cough but clinical presentation differed in that loss of smell or taste (63%), headache (62%), and body aches (54.3%) were among the most common symptoms. Interestingly, fever was not frequently reported (16.8%), but we did not query regarding the use of antipyretics. The high prevalence of loss of smell or taste was similar to that previously reported in a mildly symptomatic outpatient COVID-19 population 13 and may be attributed to the highest expression of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, being in nasal epithelial cells 21. In this group of mostly mild to moderately ill patients, at least a third presented with upper respiratory symptoms (sinus congestion 50%, sore throat 35.1%), gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea 35.6%, diarrhea 37.5%), dizziness (32.7%), or chest tightness (35.6%). The wide range of presenting symptoms in the outpatient setting warrants increased awareness about the diverse manifestations of COVID-19 illness and may support a broader indication for testing and self-isolation. The percentage of asymptomatic patients in this study may be under-represented relative to the general population due to limited supply of test kits available during the study period.

Self-isolation is a key component of community mitigation efforts 22. Previous studies have shown that socioeconomic factors, such as concern over loss of compensation, may affect compliance with public health isolation recommendations 23. A key strength of our study is the description of social characteristics that may influence care outcomes and adherence to preventive strategies. In our patients, 93.3% self-reported that they were following home isolation measures. However, 32.7% did not have an available caregiver, which may reduce the ability to strictly adhere to home isolation. In the future, a better understanding of factors contributing to non-compliance with mitigation strategies is needed to assess feasibility and efficacy of current public health recommendations. Additionally, we found that over half of the people with COVID-19 did not have known contact with a person confirmed or suspected to be positive for SARS-CoV-2. This supports the need for maintaining vigilance about social distancing to reduce viral transmission. Further inquiry about the suspected place or person of potential exposure may be informative for future studies. Lastly, our population was diverse, with potentially up to a third (32.2%) speaking a language other than English as their primary language. Consideration should be given for designing public health messaging that reflects the cultural and language backgrounds of local communities.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Our sample was relatively small and limited to one geographic location. The patients do not necessarily represent all patients testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection in the Emory Healthcare Network or within Georgia. Therefore, our results may not be generalizable to other populations. Testing restrictions during the study time period may have also led to a higher proportion of symptomatic adults and healthcare workers relative to SARS-CoV-2 infection in the general outpatient population. Our method of data collection included medical record information and patient-reported history. The latter, as a result of reliance on recollection and inadvertent biases, may have led to inaccuracies in descriptions or durations of presenting symptoms and omissions or misclassifications of comorbidities. The cross-sectional design of this study also limits the ability to make conclusions about causality, course of illness, or patient outcomes.

Conclusions

In summary, our findings suggest that the demographic and clinical characteristics of non-hospitalized adults with COVID-19 illness differ from hospitalized patients with regard to age, gender, race/ethnicity, and prevalence of underlying medical conditions. Our results support the need for greater awareness of risk among younger and healthier individuals and for consideration of testing and recommending self-isolation for a wide spectrum of clinical symptoms by clinicians. Additionally, we found characterization of social factors informative for understanding feasibility of outpatient management, patient outcomes, and compliance with community mitigation strategies. Future studies on outpatient populations with COVID-19 are needed to better understand the epidemiology and manifold characteristics of COVID-19 illness.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Elizabeth Harrell, Tina-Ann Thompson, and the staff and physicians at the Paul W. Seavey Comprehensive Internal Medicine Clinic, the Emory Clinic Rockbridge, and the COVID-19 Virtual Outpatient Management Clinic for their contribution to data collection for this study.

Appendix

Table 5.

Clinical symptoms of COVID-19 VOMC patients

| Symptom | No. (%) of patients Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Fever | |

| No | 161 (77.4) |

| Yes | 35 (16.8) |

| Unknown | 12 (5.8) |

| Duration (days) | 6.5 (3.7) |

| Sore throat | |

| No | 131 (63.0) |

| Yes | 73 (35.1) |

| Unknown | 4 (1.9) |

| Duration (days) | 5 (4.3) |

| Chills | |

| No | 109 (52.4) |

| Yes | 94 (45.2) |

| Unknown | 5 (2.4) |

| Duration (days) | 5.6 (4.6) |

| Body aches | |

| No | 93 (44.7) |

| Yes | 113 (54.3) |

| Unknown | 2 (1.0) |

| Duration (days) | 5.9 (4.1) |

| Sinus congestion | |

| No | 99 (47.6) |

| Yes | 104 (50.0) |

| Unknown | 5 (2.4) |

| Duration (days) | 8.4 (5.9) |

| Cough | |

| No | 48 (23.1) |

| Yes | 157 (75.5) |

| Unknown | 3 (1.4) |

| Duration (days) | 8.9 (5.8) |

| Shortness of breath at rest | |

| No | 170 (81.7) |

| Yes | 32 (15.4) |

| Unknown | 6 (2.9) |

| Duration (days) | 5.1 (3.2) |

| Shortness of breath with exertion | |

| No | 125 (60.1) |

| Yes | 78 (37.5) |

| Unknown | 5 (2.4) |

| Duration (days) | 6.5 (3.6) |

| Wheezing | |

| No | 168 (80.8) |

| Yes | 37 (17.8) |

| Unknown | 3 (1.4) |

| Duration (days) | 5.4 (4.4) |

| Chest tightness | |

| No | 125 (60.1) |

| Yes | 74 (35.6) |

| Unknown | 9 (4.3) |

| Duration (days) | 6.3 (3.7) |

| Confusion | |

| No | 194 (93.3) |

| Yes | 8 (3.8) |

| Unknown | 6 (2.9) |

| Duration (days) | 2.8 (2.9) |

| Dizziness | |

| No | 131 (63.0) |

| Yes | 68 (32.7) |

| Unknown | 9 (4.3) |

| Duration (days) | 3.4 (2.5) |

| Headache | |

| No | 73 (35.1) |

| Yes | 129 (62.0) |

| Unknown | 6 (2.9) |

| Duration (days) | 6.7 (5.1) |

| Diarrhea | |

| No | 121 (58.2) |

| Yes | 78 (37.5) |

| Unknown | 9 (4.3) |

| Duration (days) | 4.1 (3.1) |

| Abdominal pain | |

| No | 176 (84.6) |

| Yes | 28 (13.5) |

| Unknown | 4 (1.9) |

| Duration (days) | 4.3 (5.3) |

| Nausea | |

| No | 128 (61.5) |

| Yes | 74 (35.6) |

| Unknown | 6 (2.9) |

| Duration (days) | 5.3 (5.7) |

| Rash | |

| No | 193 (92.8) |

| Yes | 7 (3.4) |

| Unknown | 8 (3.8) |

| Duration (days) | 7 (5.9) |

| Joint pain | |

| No | 136 (65.4) |

| Yes | 58 (27.9) |

| Unknown | 14 (6.7) |

| Duration (days) | 6.2 (4.5) |

| Loss of smell or taste | |

| No | 67 (32.2) |

| Yes | 131 (63.0) |

| Unknown | 10 (4.8) |

| Duration (days) | 7.1 (3.5) |

N = 208 patients seen in the Emory Healthcare COVID-19 Positive Virtual Outpatient Management Clinic 3/24/2020–4/10/2020

Author Contributions

Responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis: All authors.

Concept and design: All authors.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: MM, SB.

Drafting of the manuscript: SB, MM.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: MM.

Final approval of the submission: All authors.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Meeting Presentations

None.

Data Sharing Statement

N/A.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sharon H. Bergquist, Email: shoresh@emory.edu

Clyde Partin, Email: wpart01@emory.edu.

David L. Roberts, Email: drobe04@emory.edu

James B. O’Keefe, Email: jbokeef@emory.edu

Elizabeth J. Tong, Email: etong@emory.edu

Jennifer Zreloff, Email: jzrelof@emory.edu.

Thomas L. Jarrett, Email: tljarre@emory.edu

Miranda A. Moore, Email: miranda.moore@emory.edu

References

- 1.Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, Lofy KH, Wiesman J, Bruce H, Spitters C, Ericson K, Wilkerson S, Tural A, Diaz G, Cohn A, Fox L, Patel A, Gerber SI, Kim L, Tong S, Lu X, Lindstrom S, Pallansch MA, Weldon WC, Biggs HM, Uyeki TM, Pillai SK, Washington State 2019-nCoV Case Investigation Team. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med 2020;382(10):929–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.CDC COVID Data Tracker. https://www.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/index.html. Last accessed May 14, 2020.

- 3.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, Qiu Y, Wang J, Liu Y, Wei Y, Xia J', Yu T, Zhang X, Zhang L. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Livingston E, Bucher K. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(14):1335–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Sanyaolu A, Okorie C, Marinkovic A, Patidar R, Younis K, Desai P, Hosein Z, Padda I, Mangat J, Altaf M. Comorbidity and its impact on patients with COVID-19. SN Comprehensive Clinical Medicine. 2020;2:1069–1076. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00363-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garg S KL, Whitaker M, et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 — COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1–30, 2020. MMWR Morb mortal Wkly rep 2020;69:458–464. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3, Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 — COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1–30, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Gold JA WK, Szablewski CM, et al. Characteristics and clinical outcomes of adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19 — Georgia, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:545–550. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6918e1, Characteristics and clinical outcomes of adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19 — Georgia, March 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Sood N, Simon P, Ebner P, et al. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2–specific antibodies adults in Los Angeles County, California, on April 10-11, 2020. JAMA. :2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, and the Northwell COVID-19 Research Consortium. Barnaby DP, Becker LB, Chelico JD, Cohen SL, Cookingham J, Coppa K, Diefenbach MA, Dominello AJ, Duer-Hefele J, Falzon L, Gitlin J, Hajizadeh N, Harvin TG, Hirschwerk DA, Kim EJ, Kozel ZM, Marrast LM, Mogavero JN, Osorio GA, Qiu M, Zanos TP. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.W-j G, Z-y N, Hu Y, et al. clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang F, Deng L, Zhang L, Cai Y, Cheung CW, Xia Z. Review of the clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1545–1549. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05762-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spinato G, Fabbris C, Polesel J, Cazzador D, Borsetto D, Hopkins C, Boscolo-Rizzo P. Alterations in smell or taste in mildly symptomatic outpatients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA. 2020;323:2089. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kluytmans-van den Bergh MFQ, Buiting AGM, Pas SD, et al. Prevalence and clinical presentation of health care workers with symptoms of coronavirus disease 2019 in 2 Dutch hospitals during an early phase of the pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e209673–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Chow EJ, Schwartz NG, Tobolowsky FA, et al. Symptom screening at illness onset of health care personnel with SARS-CoV-2 infection in King County. JAMA: Washington; 2020. Symptom Screening at Illness Onset of Health Care Personnel With SARS-CoV-2 Infection in King County, Washington. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tostmann A, Bradley J, Bousema T, et al. Strong associations and moderate predictive value of early symptoms for SARS-CoV-2 test positivity among healthcare workers, the Netherlands, march 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25(16):2000508. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.16.2000508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.StataCorp . Stata statistical software: release 14. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): people who are at higher risk for severe illness. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-at-higher-risk.html. Last accessed May 20, 2020.

- 19.Asare S, Sandio A, Opara IN, Riddle-Jones L, Palla M, Renny N, Ayers E. Higher obesity trends among African Americans are associated with increased mortality in infected COVID-19 patients within the City of Detroit. SN Comprehensive Clinical Medicine. 2020;2:1045–1047. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00385-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.United States Census Bureau, Atlanta city, Georgia. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/atlantacitygeorgia,US/PST045219. Accessed May 17, 2020.

- 21.Sungnak W HN, Bécavin C, Berg M, Network HLB. SARS-CoV-2 entry genes are most highly expressed in nasal goblet and ciliated cells within human airways. ArXiv200306122 Q-Bio. March 13, 2020. https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.06122. Accessed May 17, 2020.

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Discontinuation of isolation for persons with COVID −19 not in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/disposition-in-home-patients.html. Last accessed May 18, 2020.

- 23.Self-isolation compliance in the COVID-19 era influenced by compensation: findings from a recent survey in Israel. Health Affairs.0(0):10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00382. [DOI] [PubMed]