Abstract

SUGCT (C7orf10) is a mitochondrial enzyme that synthesizes glutaryl-CoA from glutarate in tryptophan and lysine catabolism, but it has not been studied in vivo. Although mutations in Sugct lead to Glutaric Aciduria Type 3 disease in humans, patients remain largely asymptomatic despite high levels of glutarate in the urine. To study the disease mechanism, we generated SugctKO mice and uncovered imbalanced lipid and acylcarnitine metabolism in kidney in addition to changes in the gut microbiome. After SugctKO mice were treated with antibiotics, metabolites were comparable to WT, indicating that the microbiome affects metabolism in SugctKO mice. SUGCT loss of function contributes to gut microbiota dysbiosis, leading to age-dependent pathological changes in kidney, liver, and adipose tissue. This is associated with an obesity-related phenotype that is accompanied by lipid accumulation in kidney and liver, as well as “crown-like” structures in adipocytes. Furthermore, we show that the SugctKO kidney pathology is accelerated and exacerbated by a high-lysine diet. Our study highlights the importance of non-essential genes with no readily detectable early phenotype, but with substantial contributions to the development of age-related pathologies, which result from an interplay between genetic background, microbiome, and diet in the health of mammals.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00018-019-03359-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Glutaric aciduria type 3 (GA3), C7orf10, Sugct, Gut microflora, Metabolomics, Lipids, Obesity

Introduction

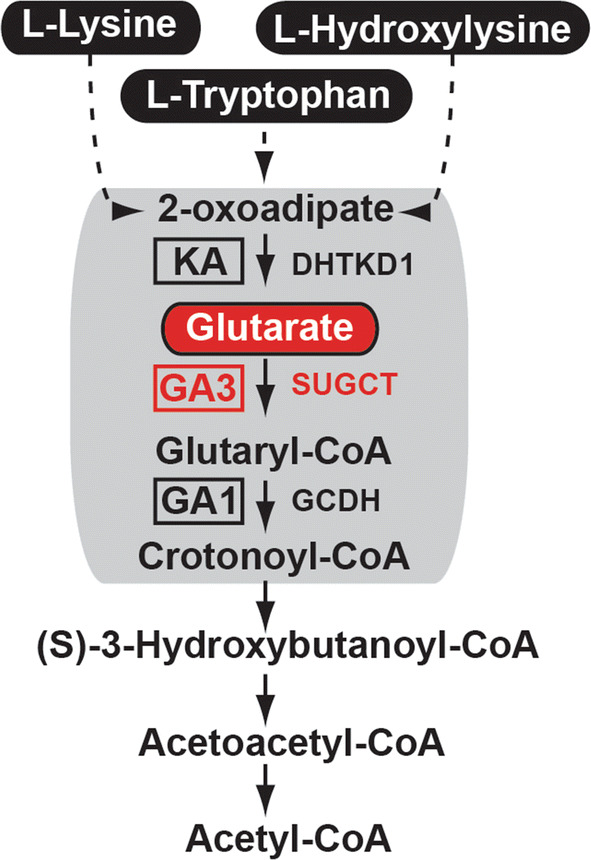

Although mitochondrial enzymes are useful therapeutic targets to combat metabolic disorders, such as obesity and diabetes, many of them still lack proper characterization [1, 2]. C7orf10 (SUGCT) is a gene with mitochondrial functions but unknown physiological role. Mutations in Sugct lead to a non-functional protein product that causes glutaric aciduria type 3 (GA3) disease in humans [3, 4]. Three types of glutaric aciduria diseases have been characterized [5]. Glutaric aciduria type 1 (GA1) develops due to mutations in glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase (GCDH) (Fig. 1), which results in severe neurologic defects [6], while glutaric aciduria type 2 (GA2) is caused by mutation of genes involved in electron transfer in the mitochondrial respiratory chain [7]. GA3 arises from the lack of function of the SUGCT gene, which disrupts mitochondrial catabolism of lysine, hydroxylysine, and tryptophan (Fig. 1). SUGCT is a well-conserved enzyme across species and encodes a succinate hydroxymethylglutarate CoA-transferase, which converts glutarate into glutaryl-CoA [3, 4]. Although many mutations have been identified in human SUGCT, only a few are thought to be associated with GA3 including two nonsense mutations (Arg108Ter and Arg142Ter) and one missense arginine to tryptophan replacement (Arg336Trp), being previously characterized as Arg299Trp due to a different reference mRNA used [3]. According to the ExAC Browser [8], the frequencies of the GA3-linked Arg108Ter and Arg336Trp mutations are approximately 1/3000 and 1/200 worldwide, respectively. Despite the high frequency of C7orf10 allele nonsense mutations, until now, only 12 patients with GA3 have been reported in the medical literature, with glutaric acid being the only significantly altered metabolite associated with the disease [3, 9–11]. In contrast to GA1 and GA2, patients with GA3 do not share distinctive symptoms, among which gastroenteritis, developmental delays, and dysmorphic features are reported, but other patients often remain asymptomatic [3, 9–11]. Therefore, unlike GA1 and GA2, the GA3 disease is poorly understood and underdiagnosed. Interestingly, a patient with GA3 disease was reported with gastrointestinal disturbances [11], and after treatment with antibiotics, the symptoms were alleviated, which could potentially suggest a role of the gut microflora in the GA3 disease.

Fig. 1.

Pathway of lysine–tryptophan catabolism. Mitochondrial enzymatic defects in tryptophan, lysine, and hydroxylysine degradation pathway found in alpha-ketoadipic aciduria, GA1, and GA3 diseases. KA ketoadipic aciduria, DHTKD1 dehydrogenase E1 and transketolase domain containing 1; [72]; GCDH glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase, SUGCT succinate hydroxymethylglutarate CoA-transferase

Driven by the ambiguous symptoms in patients with GA3, we generated Sugct knockout mice (hereinafter referred to as SugctKO) to determine in vivo functions of SUGCT in mammals. We used non-targeted global metabolomic profiling of mouse kidney and plasma, which is a powerful tool for assessing biochemical metabolites in various biological contexts. Loss of Sugct evoked changes of the gut microbiome-dependent metabolism resulting in acylcarnitine and bacterial metabolite accumulation in kidney. These symptoms are aggravated with age or when mice are fed high-lysine diet, which resulted in an obesity-related phenotype that is accompanied by lipid accumulation in kidney and liver, as well as “crown-like” inflammatory structures in adipocytes. Our findings suggest that mutations in Sugct causing GA3 disease need to be studied in the context of the gut microflora, diet, and age.

Results

Generation of Sugct knockout mice

To establish the role of the C7orf10 gene in vivo in mammals, we generated Sugct knockout mice by inserting loxP sites flanking the third exon of the Sugct gene (Figure S1a, Table S1). The targeting vector was electroporated into embryonic stem cells (ESCs) to generate heterozygous Sugct+/flox ESCs via homologous recombination (Figure S1b). Sugct+/flox ESCs were then injected into mouse blastocysts and targeted mice were obtained by standard procedures [12]. Sugctflox/flox were bred with β-actin-cre mice to generate heterozygous null (Sugct+/null) animals, which were then intercrossed to get homozygous null animals (Sugctnull/null; hereinafter referred to as SugctKO). PCR genotyping of Sugct+/flox and SugctKO mice revealed bands at the expected sizes (Figure S1c). Homozygous SugctKO mice were obtained at the typical Mendelian frequencies (Figure S1d) and were viable.

To investigate Sugct/SUGCT expression levels in various tissues and verify the efficiency of the constructed SugctKO, we isolated RNA and proteins from several WT and SugctKO organs. Unlike in the mutant animals, we detected the expression of Sugct/SUGCT in WT kidney and liver at the mRNA and protein levels, respectively (Figure S1e, f). Both tissues are known to contain a high number of mitochondria due to their elevated metabolic rate and are often challenged by toxins and pathogens. Interestingly, it has been shown using single-cell transcriptomics in mouse kidney that Sugct is mainly expressed in proximal tubules, which are immune responders to toxic injuries [13]. Accumulation of urinary metabolites in kidney, where SUGCT is mostly expressed could cause deleterious phenotypes, and therefore, we started our study with investigations of renal mouse tissue.

Metabolic changes in SugctKO mouse kidney

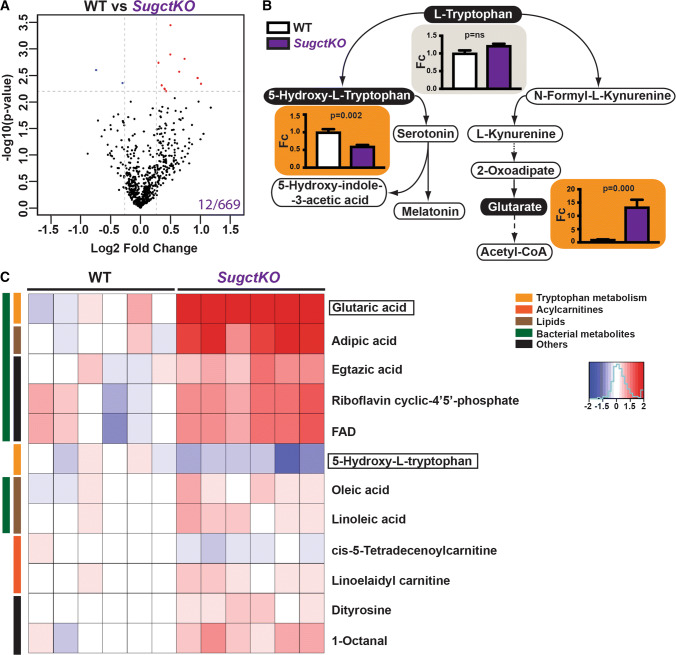

Patients with GA3 disease are known to excrete high levels of glutarate with no significant changes of acetylcarnitine, 3-hydroxyglutarate, glutarylcarnitine, and glutarylglycine in the urine [3]. To investigate whether these metabolites can be detected in SugctKO mice, we performed untargeted metabolomics using Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (LC–MS) in extracts isolated from WT and SugctKO kidney. All experimental mice were co-housed and matched gender- (male), age- (15 weeks), and backgroundwise (C57BL/6J), which means that usually, 2 wild type and 2 SugctKO mice were housed in a single cage. We detected a total of 669 compounds and tentatively annotated metabolites with an associated unique molecular mass, which in numerous cases was followed up by identity confirmation either via chemical standards or using metabolite fragmentation against libraries for possible matches [14] (Tables S2, S3, see “Materials and methods”). The data were visualized in a Volcano plot representing the differences in detected metabolites between WT and SugctKO mouse kidney (Fig. 2a). Among all identified compounds, differences in 12 metabolites were considered significant (2.2% of all metabolites; q value of 0.15, 15% False Discovery Rate (FDR), Fc ≥ 1.2). Importantly, amidst shortlisted metabolites were those involved in tryptophan catabolism (Fig. 2b). In line with the urinary metabolic alterations characteristic for patients with GA3 [3], the 11-fold increase in glutarate levels was the most prominent in SugctKO mouse kidney (Fig. 2b, c). Besides glutarate upregulation, we did not detect significant changes in acetylcarnitine, 3-hydroxyglutarate, glutarylcarnitine, and glutarylglycine in SugctKO mouse kidney (Figure S2a, Table S2) consistent with the previous clinical reports for GA3 [3]. Unfortunately, due to technical limitations, we were unable to detect lysine and its co-metabolites. Intriguingly though, tryptophan degradation via 5-hydroxy-l-tryptophan (Fig. 2b, c) was found downregulated despite unchanged tryptophan levels (Fig. 2b), which might suggest alternative degradation pathways for tryptophan. Thus, our results indicate that besides the reported altered levels of glutarate in urine of patients with GA3, there may be also changes in other metabolites.

Fig. 2.

Mass-spectrometry-based metabolite profiling in SugctKO mouse kidney. Untargeted LC–MS was performed from WT and SugctKO mouse kidney using six biological and three technical replicates. a Volcano plot of 669 metabolites detected in SugctKO vs WT mouse kidney. The volcano plot was generated as a log scaled axes of fold change (Log2, x-axis) and p value (− log10, y-axis). Significantly altered metabolites (q value = 0.15, Fc ≥ 1.2) are indicated by dashed grey lines and colored in red and blue representing up- and downregulated metabolites, respectively. Note that glutarate was excluded from the Volcano plot since the scale would be vastly different. b l-tryptophan, 5-hydroxy-l-tryptophan, and glutarate levels in tryptophan catabolism from WT vs SugctKO mouse kidney. Orange and grey boxes indicate statistically significant (q value = 0.15, Fc ≥ 1.2) and nonsignificant metabolite levels, respectively. Statistical analysis was done using two-tailed parametric paired t test. c Heatmap depicting up- (red) and downregulated (blue) compounds (q value = 0.15, Fc ≥ 1.2) from WT vs SugctKO mouse kidney. Metabolites are clustered according to the following classes: tryptophan metabolism (yellow), acylcarnitines (orange), lipids (brown), metabolites of bacterial origin (green), and others (black)

To investigate whether we can identify other metabolites related to GA3 in SugctKO mice, we expanded the analysis of our metabolomic data. The vast majority of significantly altered kidney metabolites (80%) were upregulated in SugctKO mice with only few downregulated, suggesting that SUGCT is a “repressor” of those compounds (Fig. 2c, Table S2). To get a more expanded view of the metabolic changes, we lowered the FDR to 25%, which allowed us to detect besides tryptophan co-metabolites (5.5%), also differentially regulated acylcarnitines (25.5%) and lipids (20%) (Figures S2b, S2c, Table S2). Most of these metabolites were only modestly increased, but these data still give an impression of the direction of the metabolic rewiring in SugctKO kidney. 30% of detected lipids were prenols (arnamiol, armillarin, valtrate, isopetasoide, icariside B8), while the rest, where medium/long-chain fatty acids, one glycerophospholipid, and acyl choline (Table S2). Intriguingly, among the detected lipids were those associated with gut microflora metabolism, such as adipic acid [15], as well as those contributing to dysbiosis (palmitic acid, oleic acid, and linoleic acid) [16]. In addition, 24% of detected metabolites either did not have a eukaryotic origin and/or are co-regulated by gut bacteria (Fig. 2c, S2c, S3, Table S2, S3), indicating a prokaryotic contribution to the results that we observed. Considering that the kidney is held in a sterile environment, any presence of the non-host-derived metabolites was surprising. Interestingly, it has been shown that a substantial amount of the dietary tryptophan in the human gut is metabolized by bacteria [17]. In accordance with this, we detected in SugctKO mouse kidney increased indoleacrylic acid, which derives from indole-propionic acid [18], and is known as a suppressor of commensal inflammation [19]. It is important to keep in mind that gut bacteria-derived metabolites in kidney are pathological and linked to an early decline in renal function [20, 21] (Figure S3).

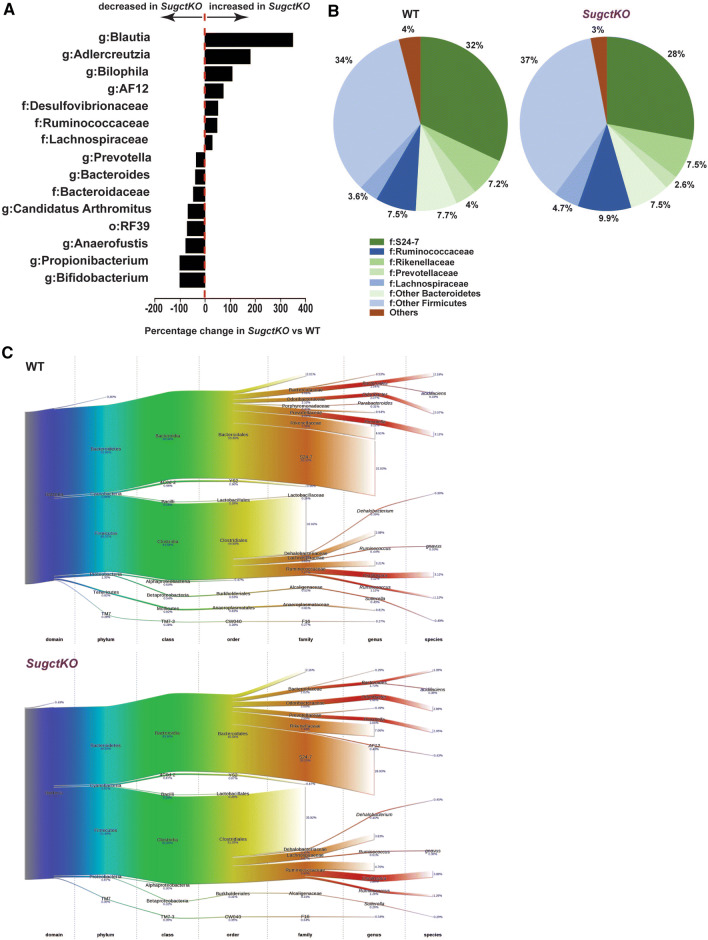

16S rRNA microbiome sequencing from stool DNA

Following recent improved understanding of the relation between the gut microbiome and human health [22], we wanted to get an overview of the bacteria species in the gut of WT and SugctKO mice and performed 16S rRNA microbiome sequencing from stool DNA. We ensured exposure to the same microbial environment by co-housing both groups of mice and found substantial differences in the proportion and also type of bacteria species detected. In particular, there was a shift resulting in increase of firmicutes relative to bacteroidetes in SugctKO mice (Fig. 3a–c and Table S5). This is strongest in the Blautia genus containing the families Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae, which mirror the changes seen in a rat model of type 2 diabetes [23] as well as a metabolic syndrome in Mexican women with diabetes [24]. The metabolic effect of these bacterial families has been attributed to presence of carbohydrate-active enzymes, sugar transport, and metabolic pathways in their genome [25]. In addition, microbial diversity changes including the Blautia genus have also been linked to levels of indole-propionic acid [26] also identified in our metabolomics data. The second most increased genus, Adlercreutzia, has also been found increased in a diabetic rat model, and interestingly, this increase could be reverted by traditional Chinese medicine Xiexin Tang [23]. The third most increased genus in SugctKO mice is Bilophila, which is known to promote inflammation and aggravates high fat diet-induced metabolic dysfunctions in mice [27]. The fourth most increased genus AF12 has also been found increased in obese mice under high-fat diet [28]. At the same time, the common health-promoting gut microbes from the Bifidobacterium genus [29] were decreased (Fig. 3a–c).

Fig. 3.

Diversity of gut bacterial microbiome in WT and SugctKO mice. a Graph depicting percentage change of indicated bacteria in SugctKO vs WT mice. The bars on the left and right side represent a percentage decrease and increase in SugctKO vs WT mice, respectively. Only significant differences between the groups with p < 0.1 are shown. b Pie chart representing changes in abundance of indicated families of bacteria. Only families with a change ≥ 10% are indicated. Shades of green indicate Bacteriodetes while shades of blue cover Firmicutes and red are others. c Sankey diagrams depicting the taxonomic flow from domain to species for WT and SugctKO mice

Our results indicate that loss of Sugct affects the microbiome with changes closely resembling observed microbiome disbalance in metabolic diseases like diabetes.

Antibiotic treatment reverses the metabolite profile of SugctKO mice

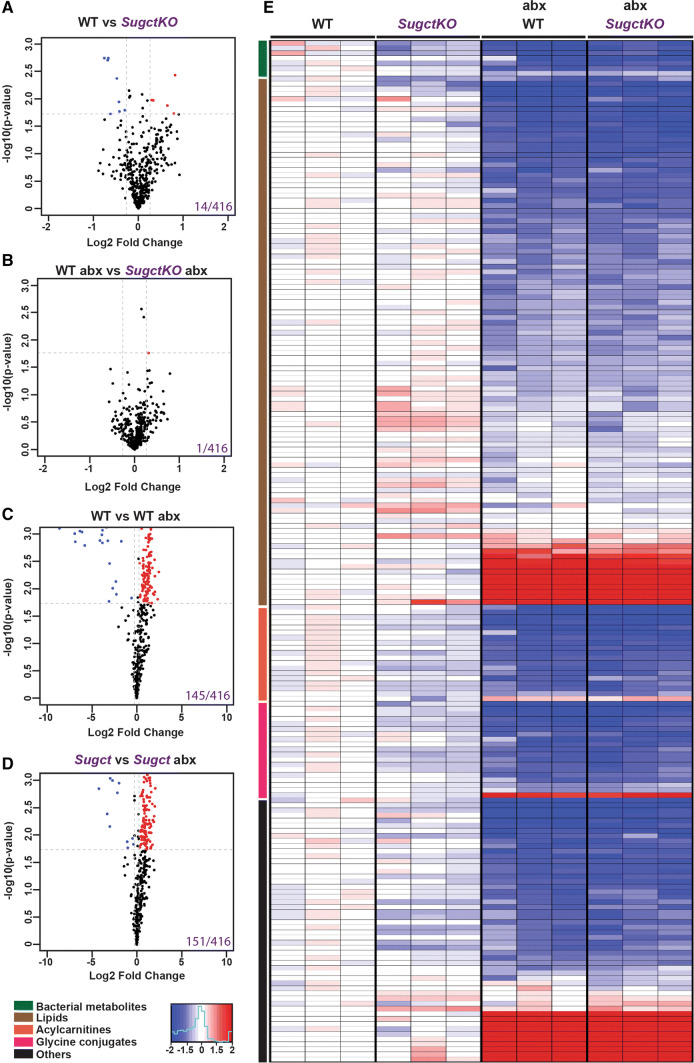

To investigate the potential contribution of intestinal bacteria to the metabolic changes detected in the SugctKO mouse kidney, we eliminated gut bacteria residing in the intestines by treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics. The efficiency of antibiotic administration (hereinafter referred to as “abx”) on intestinal bacteria clearance was tested by 16S rRNA gene amplification of bacterial nucleic acids extracted from feces (Figure S4a, see also “Materials and methods”) [30]. We were not able to detect bacterial DNA after antibiotic treatment, indicating that the number of bacteria in the intestines of our mice was below the detection limit.

To compare WT and SugctKO mice prior and post-antibiotic administration, we collected blood from the same animal and the plasma was then subjected to metabolomic analysis by untargeted LC–MS. Using the same annotation criteria as described for the kidney (see “Materials and methods”), among 416 detected peaks (Fig. 4a–d, Table S4), we found that 145 and 151 metabolites were significantly changed after antibiotic treatment in WT and SugctKO, respectively (Fig. 4c, d). Furthermore, we tentatively annotated 14 compounds with significantly altered levels in WT vs SugctKO (Fig. 4a, 14/416), which were reduced to 1 metabolite after antibiotic treatment (Fig. 4b, 1/416), indicating that the differences in metabolites between WT and SugctKO were mostly governed by gut microbiota. Both control and mutant animals treated with antibiotics displayed very low levels of bacterial metabolites, further confirming the efficiency of the gut microflora clearance (Fig. 4e, green bar). In agreement with the LC–MS study in kidney (see Fig. 2), the alterations of metabolite expression in SugctKO mouse plasma, when compared to WT, included mainly lipids and acylcarnitines (Fig. 4e). Among the upregulated lipids (32%) were mostly lysophospholipids and phosphatidylserines (Fig. 4e, Table S4), which are known to accumulate in organs with high metabolic activity, as liver [31] and brain [32], but not in plasma. High levels of lysophospholipids in the bloodstream are linked to renal failure in hemodialysis [33], while the presence of phosphatidylserines is still not understood. Despite increased lipid levels, acylcarnitines appeared to be downregulated after antibiotic treatment (Fig. 4e, Table S4), suggesting that they may originate either directly or indirectly from microbiota. We also found significantly decreased concentrations of glycine-conjugated compounds, which serve as phase II metabolic products in chemical detoxification processes and are associated with the action of gut microflora [17] (Fig. 4e, pink bar). As expected, upon antibiotic administration, the levels of glycine conjugates became similarly low in WT abx and SugctKO abx plasma (pink bar, Fig. 4e, Table S4). Of interest, among other significant metabolites detected only in SugctKO mouse plasma (Fig. 4e, black bar) were dipeptides (Table S4). Although the consequences of dipeptides in plasma remain elusive, it is known that the clearance of not fully digested proteins depends on kidney and intestine functions [34]. In addition to metabolomic differences in SugctKO mouse plasma, we did not detect any morphological changes in kidney of young SugctKO mice prior and post abx treatment (Figure S4b). Nevertheless, we observed a mild increase of lipids in SugctKO mouse kidney that disappeared in gut microflora-deprived mice (Figure S4c, d), which agrees with the lipid imbalance in SugctKO mouse kidney (see Figs. 2c, 4e, S2, S3, Tables S2, S4).

Fig. 4.

Contribution of gut microflora to plasma biochemistry in SugctKO mice. Untargeted LC–MS was performed from WT and SugctKO mouse plasma prior and post-antibiotic (abx) treatment. Three biological and three technical replicates were used for each tested condition. Volcano plots of 416 detected metabolites in mouse plasma from (a) WT vs SugctKO, b WT abx vs SugctKO abx, c WT vs WT abx, and d SugctKO vs SugctKO abx. Volcano plots were generated as previously described. X- and y-axis of depicted volcano plots display Log2FC and − log10p value, respectively. Significantly altered metabolites (q value = 0.05, Fc ≥ 1.2) are indicated by grey dashed lines and are colored in red and blue representing up- and downregulated metabolites, respectively. e Heatmap of the top 201 significantly altered (q value = 0.05, Fc ≥ 1.2) compounds from WT vs SugctKO mouse plasma, prior and post-antibiotic (abx) treatment. Red and blue color indicates up- and downregulation, respectively. Metabolites are clustered according to the following classes: bacteria-derived (green), lipids (brown), acylcarnitines (orange), glycine conjugates (pink), and others (black)

Altogether, our data suggest that the antibiotic clearance of gut microflora in SugctKO mice alleviates alterations in the levels of lipids, acylcarnitines, bacterial metabolites, glycine conjugates, and dipeptides in SugctKO mouse plasma. This indicates that the absence of the gut microbiome restores the metabolic homeostasis in the animals harboring the Sugct mutation and may also suggest that the gut microbiome plays an important role in the GA3 disease.

Age-associated obesity and glucose intolerance in SugctKO mice

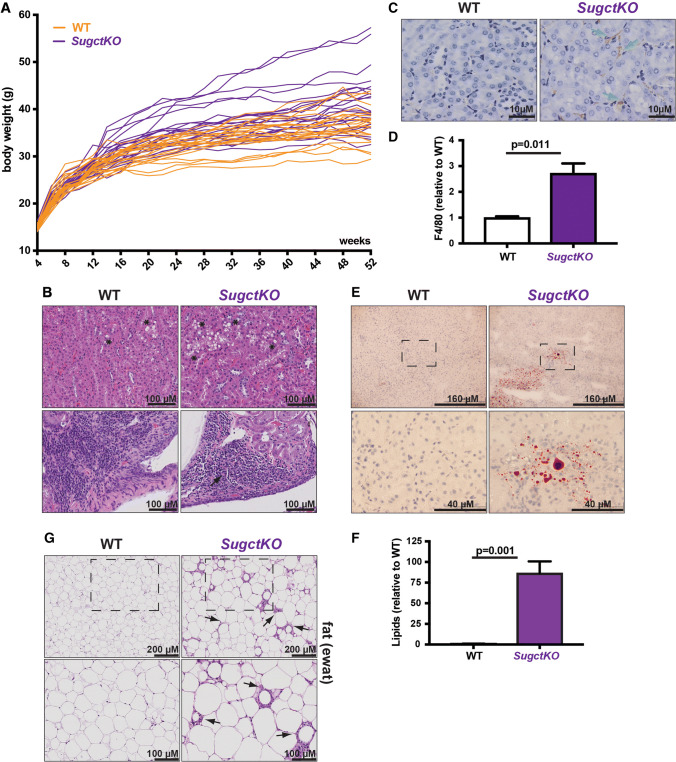

Initially, we did not observe obvious phenotypic changes in young SugctKO mice and their WT counterparts. However, renal lipidosis (see Fig. 2 and S2, S3, S4c, d) is associated with age-related progressive kidney failure and as a consequence, decreased physical and functional well-being of the patients [35, 36]. Based on this, we hypothesized that Sugct mutations could affect kidney functions in an age-dependent manner. Therefore, we aged WT and SugctKO animals for 52 weeks and monitored their body weight (Fig. 5a). Interestingly, the body weight of SugctKO mice was significantly elevated (≈ 41.5 g) when compared to their co-housed WT equivalents (≈ 36.7 g) at 52 weeks.

Fig. 5.

Ageing contributes to weight gain and kidney disease in SugctKO mice. a Body weight analysis of WT (n = 22, orange) and SugctKO (n = 22, purple) mice from 4 to 52 weeks after birth. Each line depicts the body weight of one experimental mouse. b Kidneys from 52-week-old WT (n = 10) and SugctKO (n = 10) mice were fixed and processed for H&E staining. Black asterisks indicate vacuolation, while black arrows indicate interstitial mononuclear cell infiltrate. c F4/80 immunostaining of paraffin-embedded kidney sections from 52-week-old WT (n = 3) and SugctKO (n = 3) mice. Green arrows indicate F4/80 positively stained macrophages. d Quantitative analysis of F4/80 positive staining from (c) using ImageJ. e ORO staining for lipids in the kidney from ~ 52-week-old WT (n = 4) and SugctKO (n = 4) mice. The region from the black-dashed square was 4X magnified on the picture below. f Quantification of ORO staining (e) relative to WT using ImageJ. g H&E staining of the fat (ewat) sections from ~ 52-week-old WT (n = 6) and SugctKO (n = 6) mice. Black arrows indicate adipocyte atrophy with granulomatous/mononuclear cell infiltrate (”crown-like structures”). The adipose tissue region from the black-dashed square was ×2 magnified in the picture below. Statistical analysis was done using two-tailed parametric paired t test

The significant increase of body weight in SugctKO mice could indicate metabolic dysfunction due to the loss of Sugct. Since SUGCT is highly expressed in kidney (see Figure S1e, f), where we observed metabolic changes in SugctKO mice (see Fig. 2, S2, S3), we collected kidneys from 52- to 58-week-old WT and mutant animals. We detected elevated number of vesicles in cytoplasm of renal tubular epithelial cells in WT mice [37], which in a subset of experimental SugctKO animals were further elevated (Fig. 5b, top panel). In addition, we noticed an increase of interstitial mononuclear cell infiltrate in SugctKO in comparison with WT mice (Fig. 5b, lower panel), an indication of inflammation. Therefore, we investigated the number of macrophages by tissue staining with F4/80 antibodies, best known as a marker of mature mouse macrophages and microglia [38] (Fig. 5c). We detected a threefold increased staining of macrophages in kidneys of aged SugctKO mice when compared to WT animals (Fig. 5d), which supports our hypothesis that metabolic changes in SugctKO mice may promote an inflammatory response.

Furthermore, there was lipid accumulation in the SugctKO kidney (Fig. 5e, f). Beside kidney, we analyzed histopathological changes in the liver (Figure S5a) and epididymal white adipose tissue (ewat; Fig. 5g, S5b) due to the observed weight gain in mutant animals (Fig. 5a). We observed micro- and macrovesicular steatosis in SugctKO mouse liver (Figure S5a) and we detected lipids by Oil Red O staining (Figure S5c, quantification shown in S5d). In addition, SugctKO mice displayed a greater degree of inflammation in adipose tissue, often forming “crown-like structures” [39] (Fig. 5g). This type of adipose tissue pathology indicates adipocyte death, which is often associated with macrophages surrounding dying adipocytes [39]. Despite the histopathological changes detected in kidney, liver, and epididymal white adipose tissue (ewat), no additional gross abnormalities were found in aged mutant animals.

In summary, we uncovered that ageing significantly contributes to the phenotype in SugctKO mice through increased body fat accumulation and progressive renal tubular vacuolation, which was accompanied with increased macrophage levels, fat accumulation in liver, and adipocyte death.

Lysine-enriched diet aggravates histopathological changes in SugctKO mouse kidney

Diet composition has far-reaching effects on mammalian physiology [40]. Certain diet-induced pathologies that are severe in humans might only appear later or never in mice, since they are not exposed to varied diets. As previously shown in a mouse model for GA1, GcdhKO mice despite accumulating glutaric and 3-hydroxyglutaric acid, develop only mild motor deficits, unlike humans [41]. However, 4-week-old GcdhKO mice exposed to high-lysine diet display severe striatal degeneration typical of the human GA1 disease and 75% of the mice die within 3–12 days [42].

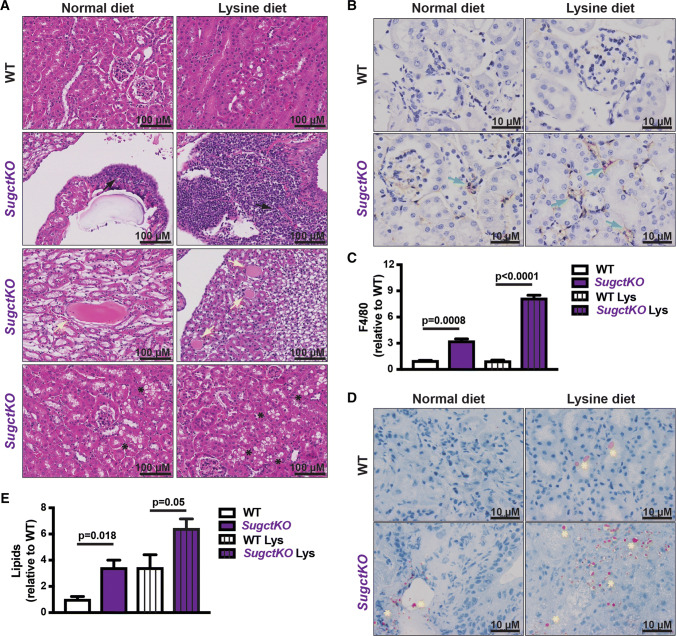

To accelerate and/or aggravate pathological changes observed in aged SugctKO mice (see Fig. 5b–f, S5), 8–12 week-old WT and SugctKO animals were fed with high-lysine diet for 20 weeks. The choice of diet was based on a previously reported study on GcdhKO mice fed with high-lysine or high-protein but not high-tryptophan diet [42] that substantially aggravated the phenotype. Although the histopathology of WT and SugctKO mice exposed to lysine diet (hereinafter referred to as “Lys”) revealed inflammation accompanied by steatosis in both WT Lys and SugctKO Lys mouse liver (data not shown), morphological changes in kidney were only detected in SugctKO Lys mice (Fig. 6a). SugctKO Lys developed acerbated interstitial mononuclear cell infiltrate, medullary tubule mineralization, tubular proteinosis, tubule dilation, and cystic change accompanied with increased renal tubular vacuolation compared to their corresponding controls (Fig. 6a). The presence of inflammatory cells in SugctKO Lys mouse kidney was confirmed by F4/80 staining (Fig. 6b, c). The number of detected macrophages in SugctKO on normal diet was threefold higher when compared to WT, while SugctKO Lys displayed almost a 2.5-fold increase in respect to SugctKO with no observed change in WT Lys mouse kidney (Fig. 6c). Moreover, the inflammatory state in kidney of SugctKO mice on normal diet was accompanied by an increase in lipid accumulation, which was aggravated by approximately threefold in SugctKO mouse kidney in relative comparison to WT and increased by additional twofold in SugctKO Lys (Fig. 6d, e). Interestingly, the lipid levels in WT Lys were similar to SugctKO on normal diet (Fig. 6d, e). Taken together, increased intake of dietary lysine in the context of Sugct deficiency elevates lipid accumulation and inflammatory cells in the kidney, suggesting that diet could also be a factor in the development of the GA3 disease.

Fig. 6.

Dietary lysine supplementation aggravates the phenotype of SugctKO mice. 8–14 week-old mice were fed a normal [WT (n = 3), SugctKO (n = 4)] or 5xlysine diet [WT Lys (n = 4), and SugctKO Lys (n = 6)] for 20 weeks. a Kidneys were fixed and sections were subjected to H&E staining. Black arrows indicate mononuclear interstitial cell infiltrate, yellow arrows display tubule dilation, cystic change and tubular proteinosis, and black asterisks indicate macrovesicular renal tubule vacuolation, respectively. b F4/80 immunostaining of paraffin-embedded kidney sections from WT (n = 3) and SugctKO (n = 3) mice. Green arrows indicate F4/80 positively stained macrophages. c Quantification of (b) by ImageJ. d ORO staining of frozen kidney sections from WT (n = 3) and SugctKO (n = 3) mice to detect lipids. Yellow asterisks indicate lipid accumulation. e Quantification of (d) by Image J. Statistical analysis was done using two-tailed parametric paired t test

Discussion

We investigated the pathophysiology of the GA3 disease by performing metabolomics in kidney and plasma using our SugctKO mouse model. We found that Sugct loss of function is not only correlated with increased glutarate levels but also lipid/acylcarnitine imbalances and dysbiosis. In addition, we uncovered significant changes in the gut microbiome of SugctKO compared to WT mice. To further investigate the influence on the gut microflora metabolism caused by the SugctKO mutation, we expanded our study to mouse plasma, whose biochemistry is known to be strongly affected by bacterial metabolites that enter host’s circulatory system [17]. We found that the clearance of the gut microflora eliminated the metabolic differences between WT and SugctKO mouse plasma, indicating that the metabolism of SugctKO mice is regulated indirectly or directly by the microbiome. Furthermore, metabolic changes in SugctKO mice were connected to age-dependent susceptibility to excessive weight gain, as well as a potential decline in kidney function accompanied with pathological changes in liver and white adipose tissue. Last but not least, high-lysine diet was an important factor in aggravating and accelerating the severity of the observed pathologies in SugctKO mouse kidney. Overall, our results indicate that outcome of genetic mutations in Sugct is modulated by the microbiome, age, and diet.

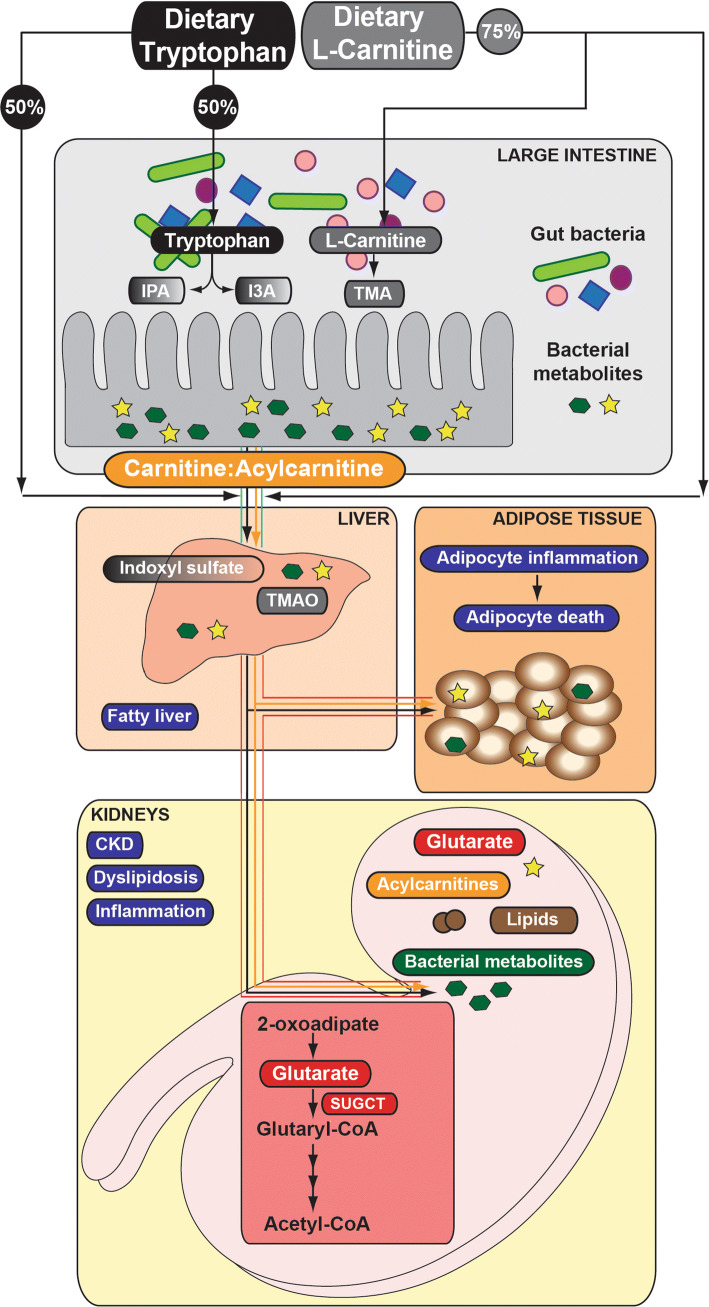

Phenotypic diversity of mammals is not only determined by the host, but also by its gut-residing microorganisms [43]. Since diet is the main source of metabolic precursors, biochemical compounds that are used in eukaryotic and prokaryotic signaling are either identical or very similar and sensing of metabolic cues depends on the communication between the host and microbes [22]. Despite that most amino acids are directly absorbed in the small intestine and further metabolized by the host [44, 45], the majority including tryptophan are degraded by the microbiota residing the large intestine [17, 46]. Such gut compartment-dependent metabolic preference depends on tryptophan’s beneficial influence on epithelial physiology and the mucosal immune system [47]. Apparently 40–60% of tryptophan is catabolized by tryptophanase-expressing bacteria to indole and its derivatives [17, 48] (Fig. 7), despite that eukaryotes retain the ability to metabolize tryptophan. Gut microbes possess different catalytic enzymes and often depend on mutual cooperation, thus any changes in tryptophan metabolism (including impaired endogenous tryptophan catabolism of the host) affects microbial homeostasis [49]. The shift between eukaryotic vs bacterial tryptophan metabolism can have far-reaching consequences for the host’s health, since indole-containing metabolites display either beneficial [indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) and indole-3-carboxaldehyde (I3A)] [50, 51] or toxic properties [indoxyl sulfate] [52]. Such harmful metabolites, if not cleared by the kidney and excreted in the urine, may circulate in the host’s body and accumulate in various organs, including kidney [52], liver, and/or adipose tissue leading to the development of severe pathologies over time (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Generation, absorption, and circulation of gut bacteria-derived metabolites. Microbiome-derived metabolites are produced from dietary precursors, such as tryptophan and l-carnitine. Beneficial (IPA, I3A) and toxic [trimethylamine (TMA)] metabolites cross the intestinal epithelium to enter the liver through the portal vein (blue lines). Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) and indoxyl sulfate are synthesized in the liver from TMA and indole, respectively. Once in circulation (red lines), toxic metabolites travel to distant tissues/organs/cells (adipose, kidney etc.). Accumulation of toxic solutes in the host contributes to numerous pathological changes and the development of disease

We have shown that loss of Sugct leads to modestly increased accumulation of a number of different acylcarnitines in the kidney (see Figure S2c, Table S2). Acylcarnitines are acyl esters of carnitine and essential compounds involved in energy production via fatty acids in mitochondria [53, 54]. l-carnitine (l-3-hydroxy-4-aminobutyrobetaine) is either synthesized in kidney and liver by the host from two essential amino acids, lysine and methionine (25%), or is directly absorbed from food (75%). Hypothetically, in the absence of functional SUGCT, the endogenous levels of carnitine in kidney might be higher due to its elevated precursor lysine, which cannot be efficiently catabolized to acetyl-CoA (see Fig. 1). The metabolic shift towards eukaryotic carnitine production increases the amount of unabsorbed dietary carnitine and triggers its bacterial metabolism into TMA (trimethylamine), whose oxidized form (trimethylamine N-oxide; TMAO) contributes to the fatty liver phenotype in the human population [55, 56]. Considering that the major source of renal ATP production is mitochondrial β-oxidation of free non-esterified fatty acids, carnitine imbalances could result in disturbances of the carnitine : acylcarnitine ratio and consequently leads to dyslipidosis followed by renal dysfunction [57, 58] (Fig. 7). Our discovery that loss of Sugct contributes to altered metabolic homeostasis between host and gut bacteria accompanied by dyslipidosis, is in line with a recent study of the GA3 disease, where a patient was reported with gastrointestinal disturbances [11]. Interestingly, treatment of the patient with antibiotics alleviated the symptoms, which indicates an important role of the gut microflora in the GA3 disease progression. Although this anecdotal finding supports our own results, a lot more GA3 patients will need to be treated with antibiotics before a final conclusion can be drawn.

There is growing evidence that beside environmental factors, genetic control shapes host-gut microbiota interactions [43, 59], which partially explains the emerging contribution of the microbiome to the onset of obesity [60, 61]. Until now, the GA3 disease has been poorly understood, underdiagnosed and in the majority of cases untreated. Therefore, mutations in Sugct should be considered as an important contributing factor in patients with metabolic disorders and detection of acylcarnitines/lipids/bacterial metabolites could serve as useful biomarkers for the choice of disease treatment.

Materials and methods

All animal works were done in a humane way and were approved by Biological Resource Center (BRC) of Biopolis in A*STAR (IACUC #171268). Mice were housed under standard conditions, maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle, and were co-housed. If not stated differently, mice were fed a standard chow diet containing 6% crude fat (Altromin, #1810) and were treated in compliance with the institutional guidelines for animal care and use. The high-lysine diet was prepared by adding free lysine to a standard diet (customized from Altromin) to achieve 4.7% total lysine (5X of the normal diet).

Generation of knockout mice

Mouse genomic DNA harboring the Sugct locus was retrieved from the BAC clone RP23-451G10 (Invitrogen, PKB1129) and inserted into the pBlight-TK vector. LoxP recombination sites and Neo cassette were introduced flanking the third exon of murine Sugct genomic locus [62]. The targeting vector (PKB1318) was linearized by NotI digestion and electroporated into ES cells. Positive and negative selection with geneticin and ganciclovir, respectively, was followed by the homologous recombination screen of genomic DNA from ES cell colonies using Southern blot technique (5′ probe: chromosome 13, 17670059–17670559 bp; 3′ probe: chromosome 13, 17675399–17675899 bp). XhoI was a restriction enzyme used for screening both 5′ and 3′ end recombination events. Correctly targeted ES clones (9002, 9022, 9030) were used for the generation of the Sugct conditional knockout mouse strain. The Sugctflox allele was obtained by crossing Sugct conditional knockout mice with β-actin-Flpe transgenic mice [63] [strain name: B6.Cg-Tg(ACTFLPe) 9205Dym/J; stock no.: 005703.; The Jackson Laboratory] to remove the Neo cassette. Sugctflox mice were then crossed with β-actin-Cre transgenic mice [strain name: FVB/N-Tg(ACTB-cre)2Mrt/J; stock no.: 003376; The Jackson Laboratory] [64] to generate Sugct+/null mice that were subsequently intercrossed to obtain Sugctnull/null mice and these were backcrossed at least 10 times to a C57BL/6 J background.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR

RNA extraction was performed using the TRIzol® Reagent (Ambion™ Life technologies, #15596018) extraction protocol. The TRIzol reagent was added to kidney and liver samples (~ 40 mg) in 2 mL lysing matrix D tubes (MP Biomedicals™, #6913-500). Tissues were homogenized in a Precellys 24 Dual® (Bertin Technologies) at 4 °C using three cycles of 60 s at 5000 rpm. RNA concentration was measured with an eight-sample spectrophotometer (ND-800, NanoDrop®). cDNA was prepared using Maxima® Reverse transcriptase (Fermentas Life Sciences, #EP0741), followed by qPCR using Maxima® SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Fermentas Life Sciences, #K0251) with 10 ng of cDNA per reaction in a real-time thermal cycler (Corbett Research). Absolute quantification was obtained by a standard curve method using known concentration of serially diluted kidney RT-PCR product [65]. Primers used in this study are listed in Table S1.

Western blot analysis

Frozen tissues were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 2X protease inhibitors [20 μg/mL each of leupeptin, chymostatin, and pepstatin; Chemicon, EI8, EI6, and EI10, respectively]) for 20 min on ice and clarified by centrifugation. Protein concentration was assessed using the BCA assay (Thermo Scientific, #23225). The protein extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PDVF membrane (Millipore, IPVH0010) using a semi-dry trans-blot system. Buffer containing TBS with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T) and 4% milk (Biorad, 1706404) was used as a blocking agent. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-C7ORF10 (Proteintech Group, #21589-1-AP) and anti-Hsp90 (BD Transduction Laboratories, #610419).

LC–MS profiling from mouse kidney and plasma

Aqueous fractions were analyzed on a 6540 Quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (QTOF-MS, Agilent Technologies). The instrument was run in both positive and negative electrospray ionization (ESI) modes with scan range 50–1700 m/z and scan rate of 2 spectra/s. 5 μL of kidney and plasma extracts were injected onto Atlantis T3 Columns (100Å, 3 μm, 4.6 mm × 150 mm, #186003729). The mobile phases A and B consisted of 100% water with 0.1% formic acid and 100% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid, respectively. The gradient elution was as follows: 99.5% mobile phase A starting point held for 5 min, decreased over 15 min to 0% mobile phase A and held for 8 min. The column was re-equilibrated for 10 min. Total run time per sample was 38 min including equilibration.

Kidney sample preparation for LC–MS analysis

Approximately 100 mg of kidney tissue per sample was homogenized twice with 800 µL of 1:1 methanol (MeOH):H2O and followed by centrifugation at 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was further partitioned twice using liquid–liquid extraction with 800 µL 4:1 dichloromethane:MeOH. The aqueous fraction was centrifuged, dried, resuspended in 200 µL 1:1 MeOH:H2O, and subsequently processed by LC–MS analysis.

Antibiotic treatment, blood collection, and sample preparation for LC–MS analysis

Streptomycin sulfate salt (Sigma-Aldrich, #S6501) and penicillin G sodium salt (Sigma-Aldrich, #P3032) were added to drinking water at the concentration of 2 g/L and 1500 U/mL, respectively. The drinking water was changed every 3 days during the 4-week long treatment. Blood from WT and SugctKO mice (5-week-old prior and 9-week-old post-treatment) was collected into lithium/heparin-coated vacutainers (Microvette 500 LH, Sarstedt, #20.1345.100) either by submandibular bleeding or by terminal cardiac puncture. Vacutainers were centrifuged for 5 min at 3000 rpm at 4 °C and supernatant was immediately frozen at − 80 °C. 200 µL of acetonitrile was added to 50 µL of blood plasma per sample. The mixture was vortexed vigorously for 1 min and incubated on ice for 10 min. Subsequently, the mixture was centrifuged at 14,000g for 15 min and the supernatant was transferred for LC–MS analysis. Blank and pooled quality control (QC) samples were prepared for instrument QC purposes.

LC–MS data and statistical analysis

The MassHunter Profinder software (Agilent technologies, version 6.0) was used for data extraction with the following parameters: batch recursive feature extraction; ion species allowed: H+, Na+, and K+; charge states were limited to a maximum of 2; compound ion count threshold was set to 2 or more ions; Extracted Ion Chromatogram (EIC) tolerance for mass was set to 10 ppm; retention time 2–13 min; and absolute height > 1000 counts. Peak area values from precursor ion chromatograms, extracted by the Mass Profiler Professional (MPP) software, were averaged over technical triplicate experiments by geometric mean. Compound identities for extracted precursor ion peaks were assigned by two modes of identification. First, identifications by isotopic standards were considered identified with full confidence. Second, the remainder of peaks without standard-based verification was queried against a composite database of formula-mass information from the NIST version 14 [66], HMDB version 3 [67], MassBank [68], and LIPIDBLAST [69] libraries based on the similarity of neutral mass (mass error). The distribution of mass errors against the best matching compounds was decomposed into true and false identifications, where the sub-distribution of the false identifications was learned from that of the second-best matching database entries of all peaks. The mixture deconvolution enabled us to compute the posterior probability of true identification, up to unique formula (subject to the uniqueness of mass value per structure). Compound assignments of probability 0.8 or above were taken as positive identifications, which corresponded to less than 20 ppm mass error in all cases. Finally, the identifications resulting in assignment of two or more isomers (of identical formula) were further removed from the data to avoid ambiguity of identification. Positive and negative ion mode data were processed separately throughout this process. For statistical analysis, the data were log-transformed (base 2) after adding a small fudge factor, determined by the 10 percentile point of each data set (by organ, by ionization mode) to avoid over-estimated fold change originating from noisy peaks with low peak area values. All statistical analyses were performed using R (http://cran.r-project.org), including principal component analysis, two-sample independent t tests and q value calculation, and generation of heat maps and volcano plots. In differential abundance analysis, the quantitative data matrix was obtained by summing peak area values of all peaks with identical compound identity in each sample, since abundant species tend to appear in multiple peaks, indicating long chromatographic elution. Two-sample t test followed by multiple testing correction (q value, [70]) was used for testing differential abundance in all comparisons. For the kidney data, as the total number of significant findings was very small, we applied q value of 0.15 (15% FDR) as the threshold of statistical significance. In the plasma data, we applied q value of 0.05 (5% FDR) to control the total number of false discoveries reasonably low. We also applied minimal 20% change as additional requirement in the selection of significant findings.

Bacterial DNA extraction from mouse fecal pellets and 16S rRNA gene PCR amplification

Feces were freshly collected and immediately snap frozen in liquid nitrogen before extraction using QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (#51604). Extracted bacterial DNA was amplified using the primer pair 338F* (PKO6597) and 1061R (PKO6598), as has been described [30]. All primers are listed in Table S1.

16S rRNA gene amplification and sequencing

We used the method that has been described by Ong et al. [30] and recently by Ta et al. [71]. Our comparison groups consisted of 7 WT and 7 SugctKO mice that were all co-housed for consistent exposure to the same microbial environment, which meant that always 2 WT and 2 SugctKO mice were housed in the same cage. We identified significant differences between the averages of the two groups with one-sided t test assuming equal variance (p < 0.1) and rank them by percent increase or decrease in SugctKO mice (Fig. 3a). In addition, we summarize the total composition of the microbiome as pie charts (Fig. 3b) and Sankey diagrams (Fig. 3c) generated using a sequence similarity cut off [30, 71] and the bacterial accession in the Greengenes database.

Histology

For hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF, Sigma-Aldrich, HT501128) for 18–24 h, transferred to ice–cold 70% ethanol, and embedded in paraffin blocks followed by the staining of tissues sections.

Oil red O (ORO) staining

Slides with frozen tissue sections were dipped in isopropanol 60% for 5 min and stained in filtered ORO working solution [3:2—ORO stock (1% ORO in isopropanol): Dextrin (1% Dextrin in water)], followed by rinse in isopropanol 60%. Then, slides were counterstained in hematoxylin solution for 2 min, washed in deionized water for 1 min, followed by the wash in tap water for 5 min.

F4/80 immunohistochemistry

Slides with paraffin-embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated at room temperature for 5 min, followed by blocking of endogenous peroxidase in methanol/H2O2 (1:33.3) for 15 min and rehydration in water for 1 min. Subsequently, slides were incubated with 20 mg/mL Proteinase K (Invitrogen, #25530-049) for 20 min at 37 °C, washed 2× in Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), and blocked with 1% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA, Sigma-Aldrich, #A7906-100G) for 45 min at RT. After blocking, slides were incubated with primary rat anti-mouse F4/80 (Serotec, #MCA497G) antibodies (1/200) at RT, washed 3× in PBS followed by incubation with AffiniPure rabbit anti-rat secondary antibodies (1:5000, Jackson ImmunoResearch, #312 005-003) for 1 h at RT. Slides were washed 3X in PBS, treated for 30 min with Dako Envision + System-HRP Labeled Polymer Anti-mouse (DAKO, #K4001) for 30 min at RT, washed 3× in PBS, incubated with Dako Liquid 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) + Substrate Chromogen System [(DAKO, #K3468), 1 drop of the DAB Chromogen per mL of Substrate Buffer] for 5 min at RT, counterstained with hematoxylin for 5 min at RT, washed 3X in PBS, rinsed with running water, and mounted.

Statistics

All experiments were performed with a minimum of three animals. For data that followed a normal distribution, statistical significance was tested using the two-way Student t test. For LC–MS plasma analysis, we used two-way ANOVA. Data were represented, as the mean value and error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). p value was calculated with two-tailed paired t test with 95% level of confidence.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 Generation of Sugct knockout mice. (A) Sugct targeting strategy: lane I—Sugct genomic locus, lane II—gene targeting construct, lane III—Sugct flox locus after Frt-mediated recombination (Sugctflox allele), lane IV—Sugct null locus after Cre-mediated recombination. Coding exons are depicted as black boxes and are numbered above. The neomycin selectable marker (Neo), LoxP, and FRT sequences are shown as a green box, grey triangles, and red rectangles, respectively. Restriction enzyme recognition sites are shown with black vertical arrows: XhoI. Horizontal arrows denote PCR primers used for genotyping animals (P1, P2, P3). (B) Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA extracted from WT and Sugct+/flox embryonic stem cell clones. Genomic DNA was digested with XhoI and hybridized with a 5′ or a 3′ probe. (C) Genotyping PCR of DNA extracted from tails of WT, Sugct+/flox and Sugct+/null mice using primers P1, P2, and P3. (D) Expected and observed frequency (%) of P21 pups (200 pups counted in total) obtained from heterozygous Sugct intercrosses. (E) Real-time (R-T) PCR of Sugct mRNA expression levels in liver, kidney, lungs, brain, skin, muscle, heart, spleen, stomach, and testis. Sequences of primers used are listed in Table S1. There was no signal detected in SugctKO organs (data not shown). (F) Western blot analysis of SUGCT expression in liver, kidney, lungs, brain, and spleen from WT and SugctKO (P60) mice. Results represent three independent experiments. HSP90 served as a loading control (JPEG 2776 kb)

Supplementary material 2 Related to Fig. 2. LC–MS-based metabolomic profiling of kidney extracts from WT and SugctKO mice. (A) Graphs representing fold change (Fc) and significance (p) of detected glutarylcarnitine and acetylcarnitine from WT (white) and SugctKO (purple) mouse kidney. (B) Volcano plot of 808 metabolites detected in WT vs SugctKO mouse kidney. The volcano plot was generated as a log scaled axes of fold change (Log2, x-axis) and p value (-log10, y-axis). Significantly altered metabolites (p value ≤ 0.05, Fc ≥ 1.2) are indicated by dashed grey lines and colored in red and blue representing up- and downregulated metabolites, respectively. (C) Heatmap depicting up- (red) and downregulated (blue) compounds (p value ≤ 0.05, Fc ≥ 1.2) from WT vs SugctKO mouse kidney. Metabolites are clustered according to the following classes: tryptophan metabolism (yellow), acylcarnitines (orange), lipids (brown), metabolites of bacterial origin (green), and others (black). The estimated false discovery rate at p value cutoff 0.05 was 25.4% (q value = 0.254) (JPEG 3413 kb)

Supplementary material 3 Related to Fig. 2. Accumulation of the microbiome-derived metabolites in the kidney. Various metabolites are generated solely in the presence of the gut microflora, enter the blood flow, and possibly accumulate in kidney. The graphs depict fold change (Fc) differences of significantly altered (q value = 0.15, Fc ≥ 1.2) bacteria-derived molecules (p) between WT (white) and SugctKO mouse kidney (purple) (JPEG 1684 kb)

Supplementary material 4 Related to Fig. 4. Effects of antibiotic treatment on the plasma metabolome in SugctKO mice. (A) Bacterial DNA extraction from feces and subsequent 16S rRNA gene PCR amplification in WT (n = 3) and SugctKO (n = 3) mice prior and post-antibiotic (abx) treatment. (B) H&E staining of kidney sections from 12-week-old WT (n = 3) and SugctKO (n = 3) mice without treatment and treated for 4 weeks with abx. (C) ORO staining of frozen kidney sections from (B). Black arrow indicates lipid accumulation. (D) Quantification of ORO staining using ImageJ. Statistical analysis was done using two-tailed parametric paired t test (JPEG 4723 kb)

Supplementary material 5 Related to Fig. 5. Increased hepatic and subcutaneous fat accumulation in aged SugctKO mice. (A) H&E staining of the liver from ~ 52-week-old WT (n = 6) and SugctKO (n = 6) mice. Yellow arrows indicate hepatocellular macrovesicular lipids accumulation. (B) Body, liver, fat (ewat), and kidney (left and right) were weighed in 52-week-old WT (n = 6, white) and SugctKO (n = 6, purple) mice. (C) ORO staining of the liver from ~ 52-week-old WT (n = 4) and SugctKO (n = 4) mice. The region from the black-dashed square was 4X magnified on the picture below. (D) Quantification of ORO staining (C) relative to WT using ImageJ. Statistical analysis was done using two-tailed parametric paired t test (JPEG 5356 kb)

Supplementary material 6 Related to Figs. S1 and S4. Primers used in this manuscript (XLSX 9 kb)

Supplementary material 7 Related to Figs. 2 and S2. The combined list of detected metabolites from WT and SugctKO mouse kidney (XLSX 792 kb)

Supplementary material 8 Related to Figs. 2, 4, S2, and S3. The list of chemical standards used in our metabolomic study (XLSX 10 kb)

Supplementary material 9 Related to Fig. 4. The combined list of detected metabolites from WT vs SugctKO, WT abx vs SugctKO abx, WT vs WT abx, and SugctKO vs SugctKO abx mouse plasma (XLSX 573 kb)

Supplementary material 10 Related to Fig. 3. 16S sequencing of the microbiome (XLSX 44 kb)

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Lund University. We thank Zakiah Talib for animal care and all past and current members of the Kaldis lab for support and discussions. We thank Roger Low for contributions at early project stages and Keng Hwee Neo for exploratory work and controls not included here. We thank Falicia Goh from Natural Product Research Laboratory in BII for the discussions about the analysis of the metabolomics data. We thank Norman Pavelka for discussions and Mark Lewandoski for the β-actin–Cre/Flpe mice. We acknowledge the technical expertise provided by the Advanced Molecular Pathology Laboratory at IMCB. Lino Tessarollo was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. This work was supported by the Biomedical Research Council of A*STAR (Agency for Science, Technology and Research), Singapore, and in part by a Grant from the National Medical Research Council Singapore, NMRC (OFIRG15nov120), Natural Product Research Laboratory BMRC Transition Fund (H16/99/b0/004), and the National Research Foundation Singapore (NRF-CRP17-2017-06).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sebastian Maurer-Stroh, Email: sebastianms@bii.a-star.edu.sg.

Philipp Kaldis, Email: philipp.kaldis@med.lu.se.

References

- 1.Sinha S, Eisenhaber B, Jensen LJ, Kalbuaji B, Eisenhaber F. Darkness in the human gene and protein function space: widely modest or absent illumination by the life science literature and the trend for fewer protein function discoveries since 2000. Proteomics. 2018;18:e1800093. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201800093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenhaber F. A decade after the first full human genome sequencing: when will we understand our own genome? J Bioinform Comput Biol. 2012;10:1271001. doi: 10.1142/S0219720012710011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherman EA, et al. Genetic mapping of glutaric aciduria, type 3, to chromosome 7 and identification of mutations in c7orf10. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:604–609. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marlaire S, Van Schaftingen E, Veiga-da-Cunha M. C7orf10 encodes succinate-hydroxymethylglutarate CoA-transferase, the enzyme that converts glutarate to glutaryl-CoA. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2014;37:13–19. doi: 10.1007/s10545-013-9632-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodman SI, Markey SP, Moe PG, Miles BS, Teng CC. Glutaric aciduria; a “new” disorder of amino acid metabolism. Biochem Med. 1975;12:12–21. doi: 10.1016/0006-2944(75)90091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morton DH, Bennett MJ, Seargeant LE, Nichter CA, Kelley RI. Glutaric aciduria type I: a common cause of episodic encephalopathy and spastic paralysis in the Amish of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Am J Med Genet. 1991;41:89–95. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320410122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frerman FE, Goodman SI. Deficiency of electron transfer flavoprotein or electron transfer flavoprotein:ubiquinone oxidoreductase in glutaric acidemia type II fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:4517–4520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.13.4517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karczewski KJ, et al. The ExAC browser: displaying reference data information from over 60,000 exomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D840–D845. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennett MJ, Pollitt RJ, Goodman SI, Hale DE, Vamecq J. Atypical riboflavin-responsive glutaric aciduria, and deficient peroxisomal glutaryl-CoA oxidase activity: a new peroxisomal disorder. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1991;14:165–173. doi: 10.1007/BF01800589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knerr I, et al. Glutaric aciduria type III: a distinctive non-disease? J Inherit Metab Dis. 2002;25:483–490. doi: 10.1023/a:1021207419125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waters PJ, et al. Glutaric aciduria type 3: three unrelated canadian cases, with different routes of ascertainment. JIMD Rep. 2017;39:89–96. doi: 10.1007/8904_2017_49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diril MK, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1) is essential for cell division and suppression of DNA re-replication but not for liver regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:3826–3831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115201109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park J, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics of the mouse kidney reveals potential cellular targets of kidney disease. Science. 2018;360:758–763. doi: 10.1126/science.aar2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heischmann S, et al. Exploratory metabolomics profiling in the kainic acid rat model reveals depletion of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 during epileptogenesis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:31424. doi: 10.1038/srep31424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujisaka S, et al. Diet, genetics, and the gut microbiome drive dynamic changes in plasma metabolites. Cell Rep. 2018;22:3072–3086. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.02.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alcock J, Lin HC. Fatty acids from diet and microbiota regulate energy metabolism. F100Res. 2015;4:738. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.6078.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wikoff WR, et al. Metabolomics analysis reveals large effects of gut microflora on mammalian blood metabolites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3698–3703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812874106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macfarlane GT, Allison C, Gibson SA, Cummings JH. Contribution of the microflora to proteolysis in the human large intestine. J Appl Bacteriol. 1988;64:37–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1988.tb02427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wlodarska M, et al. Indoleacrylic acid produced by commensal peptostreptococcus species suppresses inflammation. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;22:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramezani A, Raj DS. The gut microbiome, kidney disease, and targeted interventions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:657–670. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrios C, et al. Gut-microbiota-metabolite axis in early renal function decline. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0134311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gentile CL, Weir TL. The gut microbiota at the intersection of diet and human health. Science. 2018;362:776–780. doi: 10.1126/science.aau5812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei X, et al. Xiexin Tang improves the symptom of type 2 diabetic rats by modulation of the gut microbiota. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3685. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22094-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chavez-Carbajal A, et al. Gut microbiota and predicted metabolic pathways in a sample of mexican women affected by obesity and obesity plus metabolic syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:438. doi: 10.3390/ijms20020438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biddle A, Stewart L, Blanchard J, Leschine S. Untangling the genetic basis of fibrolytic specialization by lachnospiraceae and ruminococcaceae in diverse gut communities. Diversity. 2013;5:627–640. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menni C, et al. Circulating levels of the anti-oxidant indoleproprionic acid are associated with higher gut microbiome diversity. Gut Microbes. 2019;10:688–695. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2019.1586038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Natividad JM, et al. Bilophila wadsworthia aggravates high fat diet induced metabolic dysfunctions in mice. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2802. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05249-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lai ZL, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation confers beneficial metabolic effects of diet and exercise on diet-induced obese mice. Sci Rep. 2018;8:15625. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33893-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bottacini F, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. Omics of bifidobacteria: research and insights into their health-promoting activities. Biochem J. 2017;474:4137–4152. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ong SH, et al. Species identification and profiling of complex microbial communities using shotgun Illumina sequencing of 16S rRNA amplicon sequences. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60811. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cantero I, et al. Changes in lysophospholipids and liver status after weight loss: the RESMENA study. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2018;15:51. doi: 10.1186/s12986-018-0288-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim HY, Huang BX, Spector AA. Phosphatidylserine in the brain: metabolism and function. Prog Lipid Res. 2014;56:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sasagawa T, Suzuki K, Shiota T, Kondo T, Okita M. The significance of plasma lysophospholipids in patients with renal failure on hemodialysis. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 1998;44:809–818. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.44.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adibi SA. Clearance of dipeptides from plasma: role of kidney and intestine. Ciba Found Symp. 1977;50:265–285. doi: 10.1002/9780470720318.ch15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martino-Costa AL, Malhao F, Lopes C, Dias-Pereira P. Renal interstitial lipid accumulation in cats with chronic kidney disease. J Comp Pathol. 2017;157:75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2017.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wahl P, Ducasa GM, Fornoni A. Systemic and renal lipids in kidney disease development and progression. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;310:F433–F445. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00375.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson RC, et al. Vacuolation in renal tubular epithelium of Cd-1 mice: an incidental finding. Toxicol Pathol. 1998;26:789–792. doi: 10.1177/019262339802600611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Austyn JM, Gordon S. F4/80, a monoclonal antibody directed specifically against the mouse macrophage. Eur J Immunol. 1981;11:805–815. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830111013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murano I, et al. Dead adipocytes, detected as crown-like structures, are prevalent in visceral fat depots of genetically obese mice. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:1562–1568. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800019-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leulier F, et al. Integrative Physiology: at the crossroads of nutrition, microbiota, animal physiology, and human health. Cell Metab. 2017;25:522–534. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koeller DM, et al. Biochemical, pathologic and behavioral analysis of a mouse model of glutaric acidemia type I. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:347–357. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.4.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zinnanti WJ, et al. A diet-induced mouse model for glutaric aciduria type I. Brain. 2006;129:899–910. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goodrich JK, Davenport ER, Clark AG, Ley RE. The relationship between the human genome and microbiome comes into view. Annu Rev Genet. 2017;51:413–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davila AM, et al. Intestinal luminal nitrogen metabolism: role of the gut microbiota and consequences for the host. Pharmacol Res. 2013;68:95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stoll B, et al. Catabolism dominates the first-pass intestinal metabolism of dietary essential amino acids in milk protein-fed piglets. J Nutr. 1998;128:606–614. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.3.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neis EP, Dejong CH, Rensen SS. The role of microbial amino acid metabolism in host metabolism. Nutrients. 2015;7:2930–2946. doi: 10.3390/nu7042930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blachier F, Mariotti F, Huneau JF, Tome D. Effects of amino acid-derived luminal metabolites on the colonic epithelium and physiopathological consequences. Amino Acids. 2007;33:547–562. doi: 10.1007/s00726-006-0477-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee JH, Lee J. Indole as an intercellular signal in microbial communities. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2010;34:426–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gao J, et al. Impact of the gut microbiota on intestinal immunity mediated by tryptophan metabolism. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:13. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karbownik M, et al. Indole-3-propionic acid, a melatonin-related molecule, protects hepatic microsomal membranes from iron-induced oxidative damage: relevance to cancer reduction. J Cell Biochem. 2001;81:507–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang LS, Davies SS. Microbial metabolism of dietary components to bioactive metabolites: opportunities for new therapeutic interventions. Genome Med. 2016;8:46. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0296-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deguchi T, et al. Major role of organic anion transporter 3 in the transport of indoxyl sulfate in the kidney. Kidney Int. 2002;61:1760–1768. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rebouche CJ. Kinetics, pharmacokinetics, and regulation of l-carnitine and acetyl-l-carnitine metabolism. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1033:30–41. doi: 10.1196/annals.1320.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Flanagan JL, Simmons PA, Vehige J, Willcox MD, Garrett Q. Role of carnitine in disease. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2010;7:30. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koeth RA, et al. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2013;19:576–585. doi: 10.1038/nm.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen YM, et al. Associations of gut-flora-dependent metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide, betaine and choline with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19076. doi: 10.1038/srep19076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bobulescu IA. Renal lipid metabolism and lipotoxicity. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2010;19:393–402. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32833aa4ac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kang HM, et al. Defective fatty acid oxidation in renal tubular epithelial cells has a key role in kidney fibrosis development. Nat Med. 2015;21:37–46. doi: 10.1038/nm.3762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goodrich JK, et al. Human genetics shape the gut microbiome. Cell. 2014;159:789–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davis CD. The gut microbiome and its role in obesity. Nutr Today. 2016;51:167–174. doi: 10.1097/NT.0000000000000167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parekh PJ, Balart LA, Johnson DA. The influence of the gut microbiome on obesity, metabolic syndrome and gastrointestinal disease. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015;6:e91. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2015.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee EC, et al. A highly efficient Escherichia coli-based chromosome engineering system adapted for recombinogenic targeting and subcloning of BAC DNA. Genomics. 2001;73:56–65. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rodriguez CI, et al. High-efficiency deleter mice show that FLPe is an alternative to Cre-loxP. Nat Genet. 2000;25:139–140. doi: 10.1038/75973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lewandoski M, Meyers EN, Martin GR. Analysis of Fgf8 gene function in vertebrate development. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1997;62:159–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bustin SA. Absolute quantification of mRNA using real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assays. J Mol Endocrinol. 2000;25:169–193. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0250169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stein S. Mass spectral reference libraries: an ever-expanding resource for chemical identification. Anal Chem. 2012;84:7274–7282. doi: 10.1021/ac301205z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wishart DS, et al. HMDB: the human metabolome database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D521–D526. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Horai H, et al. MassBank: a public repository for sharing mass spectral data for life sciences. J Mass Spectrom. 2010;45:703–714. doi: 10.1002/jms.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kind T, et al. LipidBlast in silico tandem mass spectrometry database for lipid identification. Nat Methods. 2013;10:755–758. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ta LDH, et al. Establishment of the nasal microbiota in the first 18 months of life: correlation with early-onset rhinitis and wheezing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142:86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hagen J, et al. Genetic basis of alpha-aminoadipic and alpha-ketoadipic aciduria. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2015;38:873–879. doi: 10.1007/s10545-015-9841-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1 Generation of Sugct knockout mice. (A) Sugct targeting strategy: lane I—Sugct genomic locus, lane II—gene targeting construct, lane III—Sugct flox locus after Frt-mediated recombination (Sugctflox allele), lane IV—Sugct null locus after Cre-mediated recombination. Coding exons are depicted as black boxes and are numbered above. The neomycin selectable marker (Neo), LoxP, and FRT sequences are shown as a green box, grey triangles, and red rectangles, respectively. Restriction enzyme recognition sites are shown with black vertical arrows: XhoI. Horizontal arrows denote PCR primers used for genotyping animals (P1, P2, P3). (B) Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA extracted from WT and Sugct+/flox embryonic stem cell clones. Genomic DNA was digested with XhoI and hybridized with a 5′ or a 3′ probe. (C) Genotyping PCR of DNA extracted from tails of WT, Sugct+/flox and Sugct+/null mice using primers P1, P2, and P3. (D) Expected and observed frequency (%) of P21 pups (200 pups counted in total) obtained from heterozygous Sugct intercrosses. (E) Real-time (R-T) PCR of Sugct mRNA expression levels in liver, kidney, lungs, brain, skin, muscle, heart, spleen, stomach, and testis. Sequences of primers used are listed in Table S1. There was no signal detected in SugctKO organs (data not shown). (F) Western blot analysis of SUGCT expression in liver, kidney, lungs, brain, and spleen from WT and SugctKO (P60) mice. Results represent three independent experiments. HSP90 served as a loading control (JPEG 2776 kb)

Supplementary material 2 Related to Fig. 2. LC–MS-based metabolomic profiling of kidney extracts from WT and SugctKO mice. (A) Graphs representing fold change (Fc) and significance (p) of detected glutarylcarnitine and acetylcarnitine from WT (white) and SugctKO (purple) mouse kidney. (B) Volcano plot of 808 metabolites detected in WT vs SugctKO mouse kidney. The volcano plot was generated as a log scaled axes of fold change (Log2, x-axis) and p value (-log10, y-axis). Significantly altered metabolites (p value ≤ 0.05, Fc ≥ 1.2) are indicated by dashed grey lines and colored in red and blue representing up- and downregulated metabolites, respectively. (C) Heatmap depicting up- (red) and downregulated (blue) compounds (p value ≤ 0.05, Fc ≥ 1.2) from WT vs SugctKO mouse kidney. Metabolites are clustered according to the following classes: tryptophan metabolism (yellow), acylcarnitines (orange), lipids (brown), metabolites of bacterial origin (green), and others (black). The estimated false discovery rate at p value cutoff 0.05 was 25.4% (q value = 0.254) (JPEG 3413 kb)

Supplementary material 3 Related to Fig. 2. Accumulation of the microbiome-derived metabolites in the kidney. Various metabolites are generated solely in the presence of the gut microflora, enter the blood flow, and possibly accumulate in kidney. The graphs depict fold change (Fc) differences of significantly altered (q value = 0.15, Fc ≥ 1.2) bacteria-derived molecules (p) between WT (white) and SugctKO mouse kidney (purple) (JPEG 1684 kb)

Supplementary material 4 Related to Fig. 4. Effects of antibiotic treatment on the plasma metabolome in SugctKO mice. (A) Bacterial DNA extraction from feces and subsequent 16S rRNA gene PCR amplification in WT (n = 3) and SugctKO (n = 3) mice prior and post-antibiotic (abx) treatment. (B) H&E staining of kidney sections from 12-week-old WT (n = 3) and SugctKO (n = 3) mice without treatment and treated for 4 weeks with abx. (C) ORO staining of frozen kidney sections from (B). Black arrow indicates lipid accumulation. (D) Quantification of ORO staining using ImageJ. Statistical analysis was done using two-tailed parametric paired t test (JPEG 4723 kb)

Supplementary material 5 Related to Fig. 5. Increased hepatic and subcutaneous fat accumulation in aged SugctKO mice. (A) H&E staining of the liver from ~ 52-week-old WT (n = 6) and SugctKO (n = 6) mice. Yellow arrows indicate hepatocellular macrovesicular lipids accumulation. (B) Body, liver, fat (ewat), and kidney (left and right) were weighed in 52-week-old WT (n = 6, white) and SugctKO (n = 6, purple) mice. (C) ORO staining of the liver from ~ 52-week-old WT (n = 4) and SugctKO (n = 4) mice. The region from the black-dashed square was 4X magnified on the picture below. (D) Quantification of ORO staining (C) relative to WT using ImageJ. Statistical analysis was done using two-tailed parametric paired t test (JPEG 5356 kb)

Supplementary material 6 Related to Figs. S1 and S4. Primers used in this manuscript (XLSX 9 kb)

Supplementary material 7 Related to Figs. 2 and S2. The combined list of detected metabolites from WT and SugctKO mouse kidney (XLSX 792 kb)

Supplementary material 8 Related to Figs. 2, 4, S2, and S3. The list of chemical standards used in our metabolomic study (XLSX 10 kb)

Supplementary material 9 Related to Fig. 4. The combined list of detected metabolites from WT vs SugctKO, WT abx vs SugctKO abx, WT vs WT abx, and SugctKO vs SugctKO abx mouse plasma (XLSX 573 kb)

Supplementary material 10 Related to Fig. 3. 16S sequencing of the microbiome (XLSX 44 kb)