Abstract

Candidiasis is a fungal infection caused by Candida species that have formed a biofilm on epithelial linings of the body. The most frequently affected areas include the vagina, oral cavity and the intestine. In severe cases, the fungi penetrate the epithelium and cause systemic infections. One approach to combat candidiasis is to prevent the adhesion of the fungal hyphae to the epithelium. Here we demonstrate that the endocannabinoid anandamide (AEA) and the endocannabinoid-like N-arachidonoyl serine (AraS) strongly prevent the adherence of C. albicans hyphae to cervical epithelial cells, while the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) has only a minor inhibitory effect. In addition, we observed that both AEA and AraS prevent the yeast-hypha transition and perturb hyphal growth. Real-time PCR analysis showed that AEA represses the expression of the HWP1 and ALS3 adhesins involved in Candida adhesion to epithelial cells and the HGC1, RAS1, EFG1 and ZAP1 regulators of hyphal morphogenesis and cell adherence. On the other hand, AEA increased the expression of NRG1, a transcriptional repressor of filamentous growth. Altogether, our data show that AEA and AraS have potential anti-fungal activities by inhibiting hyphal growth and preventing hyphal adherence to epithelial cells.

Subject terms: Antimicrobials, Fungi, Experimental models of disease

Introduction

Candida albicans is a common commensal organism in the genitourinary tracts, the intestine and the oral cavity, but can also be pathogenic causing infections by invading and damaging epithelial cells, a condition called candidiasis. In addition, C. albicans can cause life-threatening systemic infections by penetrating through the epithelial barriers1. C. albicans is a dimorphic fungus that can transform from budding yeast form cells at room temperature to invasive filamentous hyphae at 37 °C, a process vital to pathogenesis2. This transition is tightly regulated. The mitogen-activated protein kinase Mkc1 that is activated upon physical contact, is required for invasive hyphal growth and normal biofilm development3. The transcription factor Czf1 controls the contact-dependent invasive filamentation4. Other gene products regulating filamentous growth include the transcriptional regulators Cph1, Ume6, Bcr1, Tec1 and Efg15. Hyphal growth is characterized by the expression of different genes, some of which are involved in adhesion.

Biofilm formation by C. albicans is characterized by four major phases: adherence of yeast cells to a surface; initiation of biofilm formation where the hyphae are formed; maturation into complex, structured biofilm in which the fungi are embedded in an extracellular matrix; and dispersion of yeast cells from the biofilm to initiate biofilms at other sites5. The dispersion from biofilms may lead to systemic infections in the bloodstream and dissemination into other tissues. More than 50 interconnected transcriptional regulators are involved in regulating biofilm formation5. Initial attachment of C. albicans to a surface appears to involve the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked cell wall protein Eap1 and the agglutinin-like protein Als16. The agglutinin-like protein Als3 and the hyphal-specific wall protein-1 gene product Hwp1 function as complementary adhesins involved in cell–cell and cell-surface interactions of hyphae2,6. Als3 was found to bind N-Cadherin on endothelial cells and E-Cadherin on epithelial cells7. Strains defective in ALS3 can form mycelium normally, but are defective in biofilm formation8. HWP1 encodes a cell wall mannose protein essential for normal growth of the mycelium2. HWP1 mutant strains could not stably adhere to the epithelial mucosal cells and were more easily engulfed and cleaned by the host cells9. ALS3, HWP1, HGC1 and ECE1 are upregulated in hyphae2. Hyphal G cyclin 1 (Hgc1) is involved in regulating mycelial growth and represses cell separation from hyphae2. ECE1 encodes for candidalysin, a peptide toxin that activates epithelial cells10 and leads to cytolysis of mononuclear phagocytes11, and as such is considered to be a virulence factor. EED1 and PGA34 are dispensable for epithelial invasion, but essential for damage of epithelial cells12.

One approach to prevent systemic candidiasis is to prevent the adherence of the filamentous fungi to epithelial cells. Here we have studied the ability of the endocannabinoids anandamide (N-arachidonoylethanolamine; AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), and the endocannabinoid-like compound N-arachidonoyl serine (AraS) to prevent the interaction between C. albicans hyphae and the epithelial cells. Endocannabinoids are endogenous bioactive lipids derived from arachidonic acid which is produced by hydrolysis of membrane phospholipids13. The endocannabinoid system affects multiple functions including feeding, pain, learning and memory14. In addition, AEA has been shown to exert anti-inflammatory activities attenuating the development of inflammation in a mouse model of ulcerative colitis15. In human and rodents, AEA acts as an endogenous agonist of the cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors, and can also activate the vanilloid receptor TRPV1 resulting in transient calcium influx16,17. Also 2-AG may act on other receptors besides CB1 and CB2, including GABAA, PPARγ, TRPV1 and GPR5518. AraS binds weakly to the CB1, CB2 and TRPV1 receptors17, but seems to act on GRP55 to stimulate angiogenesis and endothelial wound healing19.

We have previously shown that both AEA and AraS reduce biofilm formation of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA)20 and sensitize MRSA to antibiotics21. Both compounds reduced the metabolic activity and spreading ability of these bacteria20. So far, endocannabinoids have not been tested for their activity on Candida, and the aim of the present research was to study this issue. We show here that treatment of C. albicans with either AEA or AraS strongly reduced the interaction between C. albicans hyphae and cervical epithelial cells. In addition, we observed that AEA and AraS prevented yeast-hypha transition and the growth of preformed hyphae. Gene expression studies showed down-regulation of the adhesins HWP1 and ALS3, the transcriptional regulators EFG1 and ZAP1, and the hyphal morphogenesis regulators HGC1 and RAS1. On the other hand, NRG1, a repressor of filamentous growth, was upregulated.

Results

Anandamide and N-arachidonoyl serine prevent the yeast-hypha transition of Candida albicans

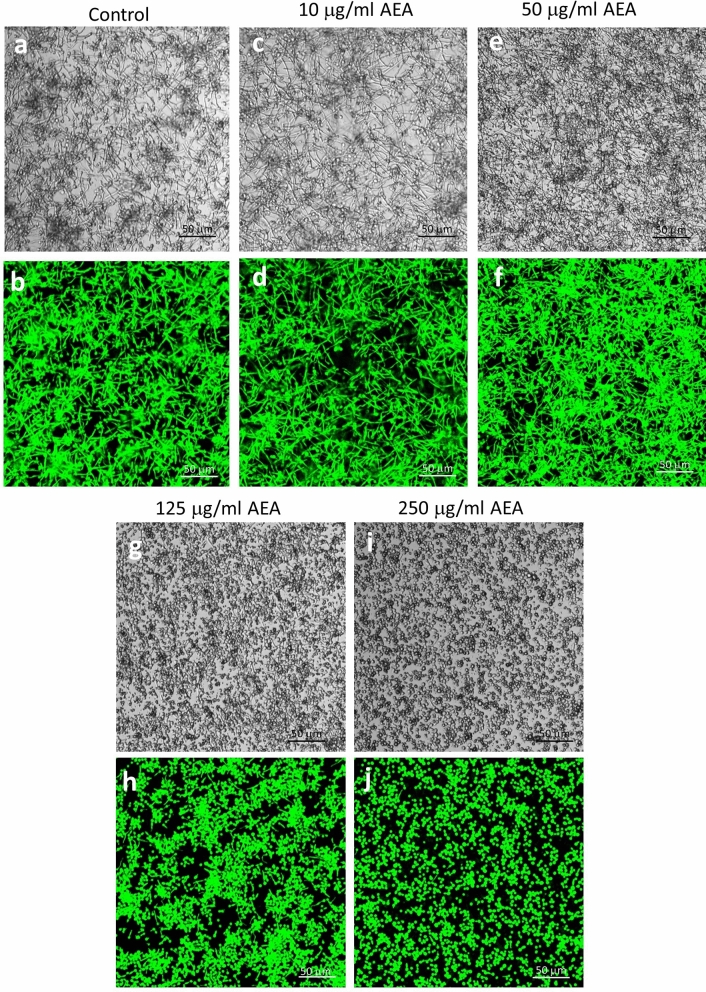

It is well known that the virulence of Candida depends on its transition from the yeast form to filamentous hyphae2. It was therefore important to study the effect of the endocannabinoids anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), and the endocannabinoid-like N-arachidonoyl serine (AraS) on this transition. To this end, we exposed GFP-expressing Candida albicans in the yeast form to various concentrations of AEA, AraS and 2-AG and incubated them for 4 h at 37 °C, a condition resulting in the transition to hyphae. Most of the fungi have transformed to filamentous hyphae in the control and in the fungi exposed to 10 μg/ml AEA (Fig. 1a–d). In samples treated with 50 μg/ml AEA, most of the fungi had transformed to hyphae, but also several fungi in yeast form and fungi with short hyphae were seen (Fig. 1e–f). However, almost no transformation to hyphae was observed in Candida exposed to 125 and 250 μg/ml AEA (Fig. 1g–j), indicating that AEA at these concentrations prevents the yeast-hypha transition. Similarly, AraS strongly inhibited yeast-hypha transition at 125 and 250 μg/ml, with partial inhibitory effect at 50 μg/ml (Suppl. Figure 1). 2-AG had no significant effect on the yeast-hypha transition (data not shown). When looking at the vegetative growth of C. albicans in the yeast form, a delay in the growth was observed in the presence of higher concentrations of AEA, AraS and 2-AG (Suppl. Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Anandamide prevents yeast-hypha transition. GFP-expressing Candida albicans taken from PDA plates in its yeast form was incubated with different concentrations of AEA at 37 °C for 4 h, and the morphology studied by confocal microscopy. (a, c, e, g, i) Bright field. (b, d, f, h, j) green fluorescence.

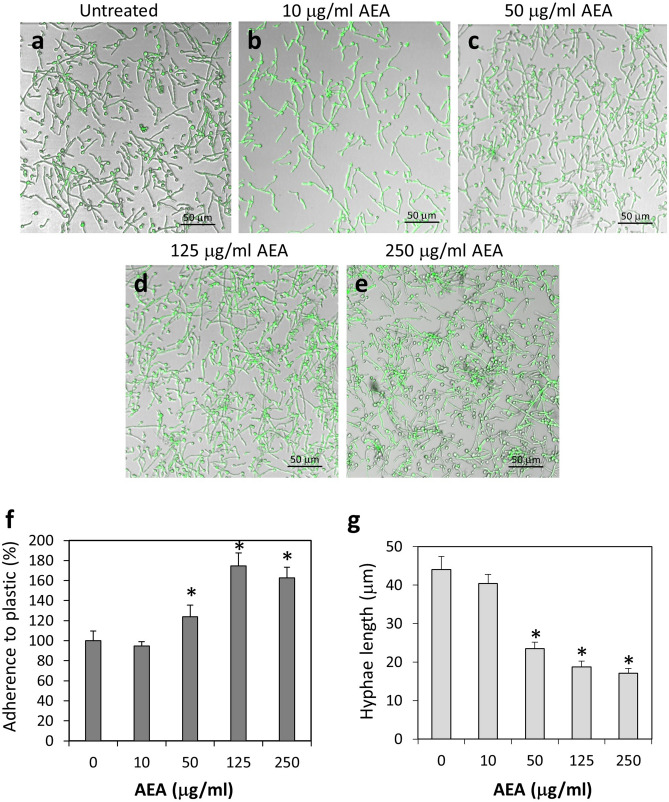

Anandamide impairs the further growth of preformed hyphae

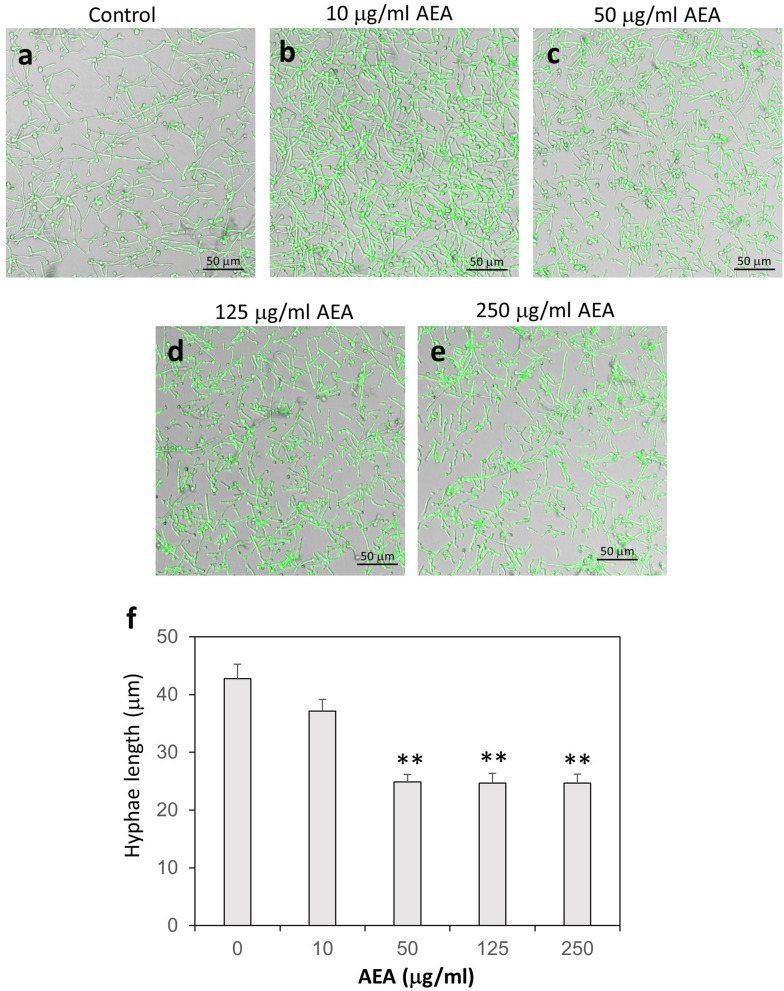

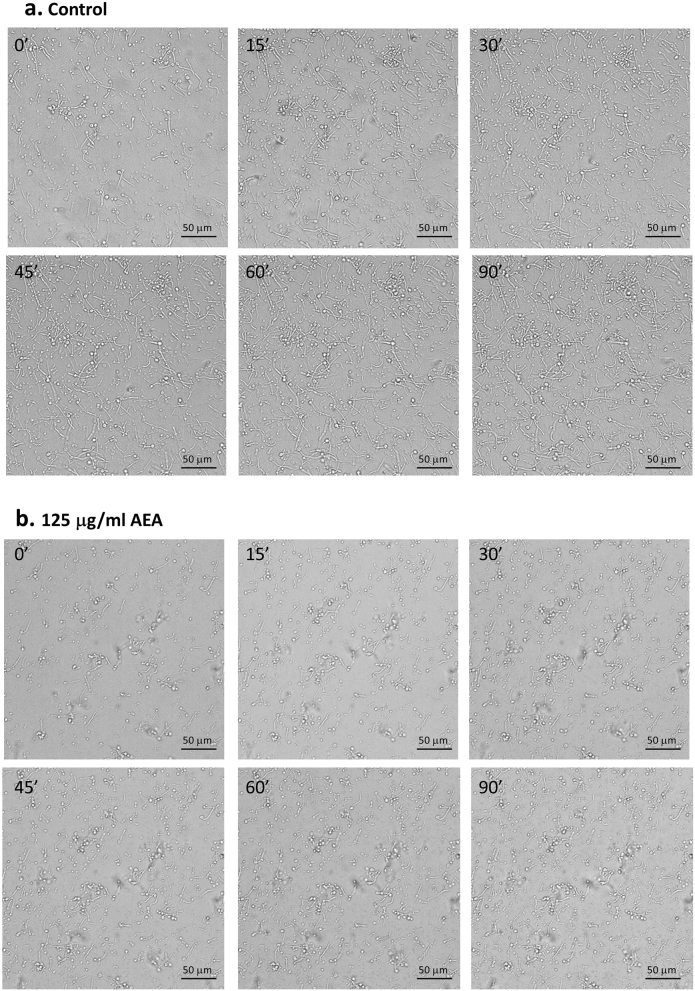

Since AEA prevented the morphogenetic switch from yeast to hyphae, we wondered whether AEA could affect the hyphae after being formed. For this purpose, we allowed the Candida to form hyphae by an overnight incubation at 37 °C, and then exposed the hyphae to various concentrations of AEA for 1 h. The majority of the hyphae length in the control and 10 μg/ml AEA-treated samples ranged between 25–60 μm (Fig. 2a,b). Most of the C. albicans hyphae treated with 50, 125 and 250 μg/ml AEA for 1 h showed shorter hyphae length ranging from 15–30 μm (Fig. 2c–e). Occasionally, some hyphae with exceptional long length (90–100 μm) appeared in both the control and treated samples (Fig. 2). We next wanted to know whether the shorter hyphae observed in the AEA-treated samples are due to an inhibition of hyphal growth. To study this possibility, C. albicans in its yeast form was first allowed to form hyphae by incubating them 4 h at 37 °C, and then subjected to a 3 h time-lapse microscopy at 37 °C in the absence or presence of 125 μg/ml AEA. As expected, the hyphae continued to grow in the control samples (Fig. 3a and Suppl. Figure 3a—time-lapse video). However, most of the hyphae ceased growing after being exposed to AEA (Fig. 3b and Suppl. Figure 3b—time-lapse video), suggesting that AEA interferes with hyphal morphogenesis. Similar inhibition of hyphal growth was observed when exposing the hyphae to 50 μg/ml AEA (data not shown).

Figure 2.

AEA treatment of C. albicans hyphae leads to shorter hyphae than control. (a–e) Confocal microscopy of control and AEA-treated C. albicans. GFP-expressing C. albicans taken from PDA plates in its yeast form was incubated in RPMI at 37 °C for 16 h, and then exposed to different concentrations of AEA for 1 h and the morphology studied by confocal microscopy. The merged bright fields and green fluorescence are shown. (f) The average hyphae lengths of untreated and AEA-treated C. albicans. Number of hyphae measured for each sample was 90–110 from 4–5 different fields. **p < 0.001.

Figure 3.

AEA inhibits hyphal growth. (a) Spinning scan microscopy of control hyphae at time 0, 15, 30, 45, 60 and 90 min. (b) Spinning scan microscopy of hyphae at time 0, 15, 30, 45, 60 and 90 min in the presence of 125 μg/ml AEA. C. albicans in yeast form was allowed to form hyphae by incubating them 4 h at 37 °C, and thereafter a time-lapse study was performed using a Nikon spinning scan microscopy in the absence (a) or presence of 125 μg/ml AEA (b). Time 0 is 30 min after adding AEA.

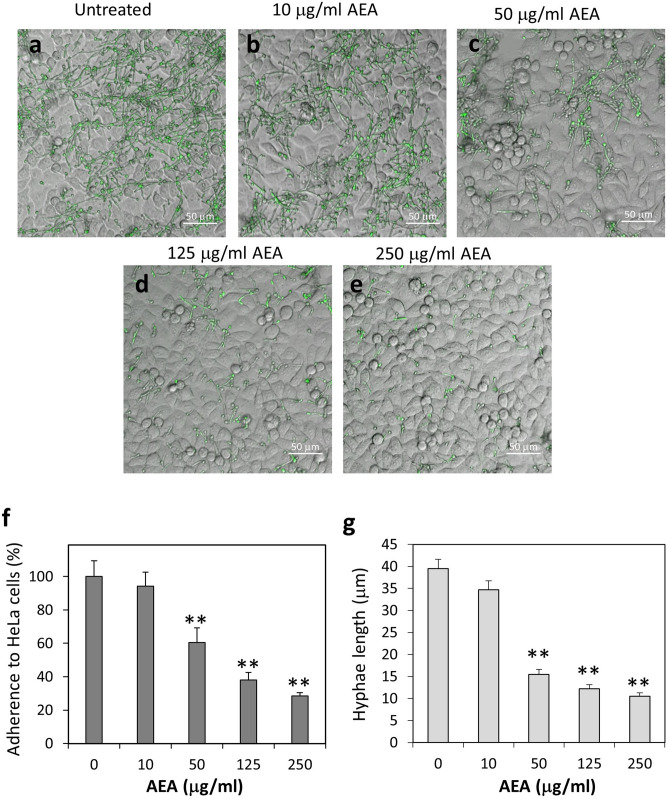

Anandamide (AEA) prevents the adherence of Candida albicans to cervical epithelial cells

Next we studied the effect of AEA on C. albicans adherence to cervical epithelial cells. GFP-expressing C. albicans were allowed to form hyphae by an overnight incubation at 37 °C. The hyphae were pretreated with various concentrations of AEA for 1 h, and then co-cultured on confluent HeLa cervical epithelial cells for another hour (Fig. 4a–e). In parallel, the same fungi samples were incubated on tissue culture plastic plates as controls that reflect the inputs (Fig. 5a–e). The morphology of the whole fungal population prior to incubation with HeLa or on plastic is shown in Fig. 2. Pretreatment of C. albicans hyphae with 50 μg/ml and 125 μg/ml AEA (Fig. 4c,d) reduced their adherence to the epithelial cells by 40 ± 8% and 62 ± 4%, respectively, with a statistical significance of p < 0.001 compared to control (Fig. 4f). Increasing the AEA concentration to 250 μg/ml (Fig. 4e) did only cause a slightly higher inhibition of 72 ± 2% (Fig. 4f), suggesting that a plateau effect is observed at 125 μg/ml. Of note, AEA-treated C. albicans hyphae that were able to bind to the epithelial cells, showed 3–fivefold shorter hyphae (Fig. 4d,e) compared to control fungi (Fig. 4a) with a p < 0.001 for 50–250 μg/ml AEA (Fig. 4g). A maximal effect on hyphae length was observed at 50 μg/ml (Fig. 4g). At a concentration of 10 μg/ml, AEA had no significant effect on the hyphae length (Fig. 4b). The hyphae that adhered to HeLa cells were also thinner and several fungi appeared without hyphae at all when using 50–250 μg/ml AEA. The appearance of shorter hyphae adherent to HeLa cells following AEA treatment is a direct consequence of the AEA effect on hyphal growth as described above (Figs. 2, 3). Of particular importance is the preferential inhibition of hyphal adhesion to HeLa cells in comparison to plastic as shown by the relative reduction in the ratio of HeLa-adherent versus plastic-adherent hyphae (Suppl. Figure 4). Pretreatment of HeLa cells with AEA prior to addition of C. albicans didn't alter the attachment of the fungi to the cells (data not shown). It should be noted that normal untreated hyphae of different lengths exhibited similar ability to adhere to HeLa cells (Suppl. Figure 5), meaning that the preferential appearance of shorter adherent hyphae after exposure to AEA is a direct consequence of the treatment.

Figure 4.

AEA treatment of C. albicans reduced their adherence to HeLa cervical epithelial cells. (a–e) Confocal microscopy of co-cultures of control and AEA-treated C. albicans on confluent HeLa cells. The fungi were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of AEA for 1 h prior to co-incubation with HeLa cells for an additional 1 h. The fungi express GFP. (f) Quantification of the relative adherence of untreated and AEA-treated C. albicans to HeLa cells. 8–10 images taken from 3 independent experiments were analyzed for each treatment. (g) The average hyphae lengths of untreated and AEA-treated C. albicans that were able to adhere to HeLa cells. The number of hyphae measured for each treatment was 50–75. **p < 0.001.

Figure 5.

C. albicans treated with AEA adhered to polystyrene plastic surface even better than untreated fungi. (a–e) Confocal microscopy of control and AEA-treated C. albicans on tissue culture plates. The fungi were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of AEA for 1 h prior to incubation on polystyrene surfaces for an additional 1 h. (f) Quantification of the relative adherence of untreated and AEA-treated C. albicans to plastic. 8–10 images taken from 3 independent experiments were analyzed for each treatment. (g) The hyphae lengths of untreated and AEA-treated C. albicans that were able to adhere to plastic. The number of hyphae measured for each treatment was 50–75. *p < 0.05.

In contrast to the reduced adherence of AEA-treated C. albicans to HeLa cells, the AEA-treated fungi adhered even better to polystyrene tissue culture plates in comparison to untreated fungi (Fig. 5a–e) with statistical significance in the concentration range of 50–250 μg/ml AEA (Fig. 5f; p < 0.05). This accords with the higher amount of hyphae observed in AEA-treated samples in comparison to control samples (Fig. 5). The hyphae length of AEA-treated C. albicans that bound to plastic were about twofold shorter on average in comparison to control (Fig. 5g) with statistical significance in the concentration range of 50–250 μg/ml AEA (p < 0.05). When incubating the C. albicans with AEA for 24 h, there was no significant alteration in the biofilm mass formed on plastic (Suppl. Figure 6). However, both 2-AG and AraS significantly reduced the biofilm mass on plastic in a dose-dependent manner with a p < 0.05 (Suppl. Figure 6).

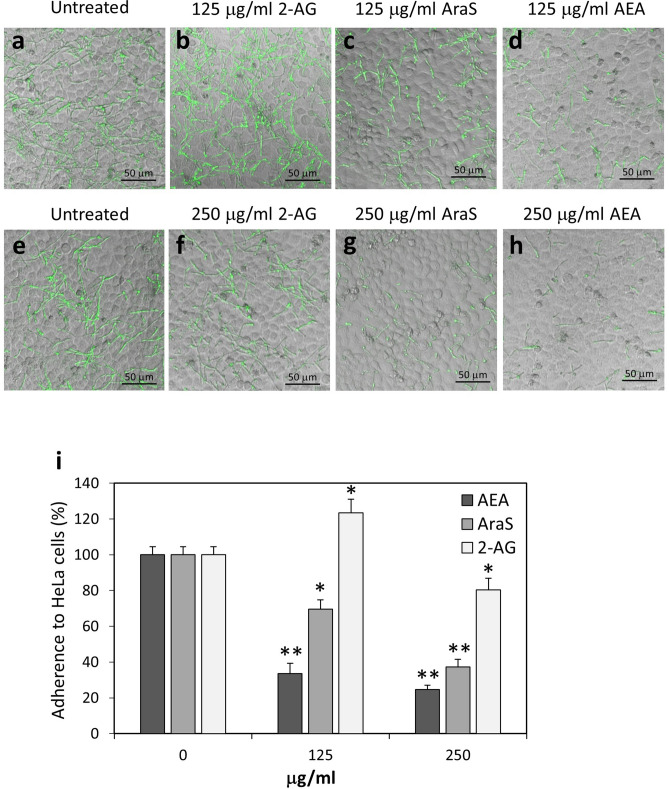

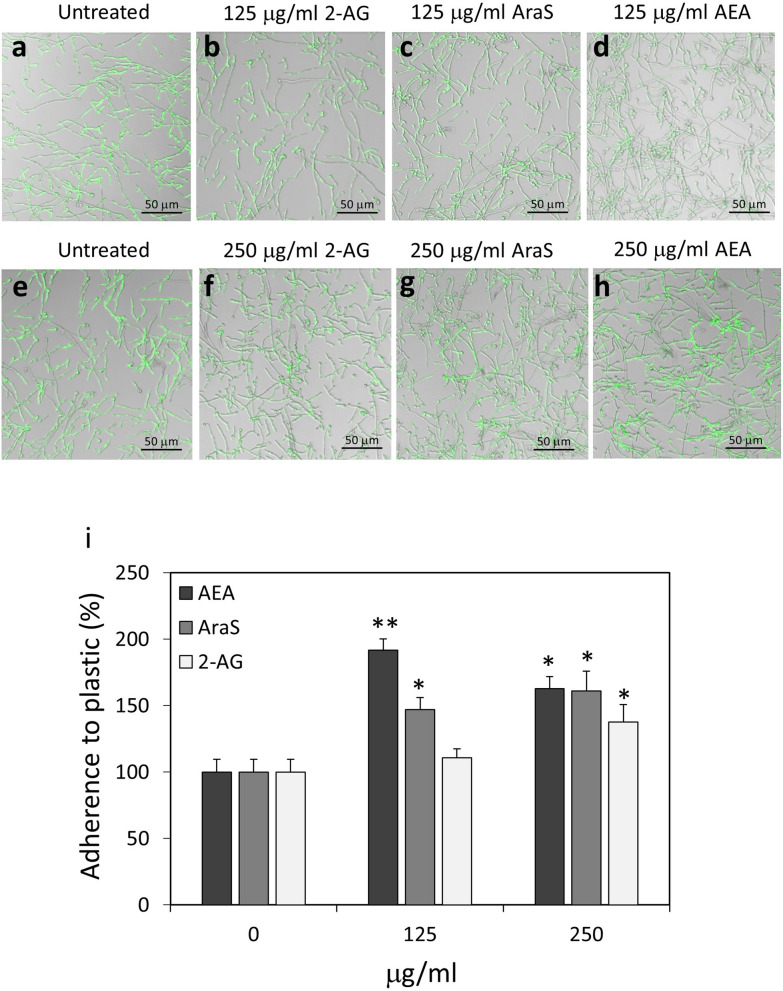

N-Arachidonoyl serine (AraS), but not 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), prevents the adherence of Candida albicans to cervical epithelial cells

We next analyzed the effect of AraS and 2-AG on the ability of C. albicans to adhere to cervical epithelial cells and compared their effect with that of AEA (Fig. 6a–h). Pretreatment of C. albicans with 125 μg/ml and 250 μg/ml AraS for 1 h (Fig. 6c,g) reduced adherence to the epithelial cells by 30 ± 5% and 63 ± 5%, respectively, with a statistical significance of p < 0.05 compared to control (Fig. 6i). The hyphae of the fungi that adhered to the epithelial cells following AraS treatment (Fig. 6g) were shorter and thinner in comparison to untreated fungi (Fig. 6a,e). However, treatment of C. albicans with 125 μg/ml and 250 μg/ml 2-AG (Fig. 6b,f) didn’t interfere with their adherence to HeLa cells (Fig. 6i). Both AraS and 2-AG treated C. albicans adhered well to polystyrene plastic within 1 h (Fig. 7). This is in contrast to the reduced biofilm mass formation on plastic after 24 h incubation in the presence of the compounds (Suppl. Figure 6).

Figure 6.

C. albicans treated with AraS showed strong reduction in their adherence to cervical epithelial cells. (a–h) Confocal microscopy of co-cultures of control and AEA-treated C. albicans on confluent HeLa cells. The fungi were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of 2-AG, AraS or AEA for 1 h prior to co-incubation with HeLa cells for an additional 1 h. (i) Quantification of the relative adherence of untreated and treated C. albicans to HeLa cells. 5–7 images were analyzed for each treatment. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

Figure 7.

C. albicans treated with 2-AG, AraS or AEA retained binding capacity to polystyrene surface. (a–h) Confocal microscopy of control and treated C. albicans bound to polystyrene plastic surface. The fungi were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of 2-AG, AraS or AEA for 1 h prior to incubation in tissue culture plates for an additional 1 h. (i) Quantification of the relative adherence of untreated and treated C. albicans to plastic. 5–7 images were analyzed for each treatment. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

AEA altered the expression of genes involved in adhesion and hyphal morphogenesis

In order to understand the anti-adhesive effects of AEA on C. albicans interaction with epithelial cells, we exposed the fungi to various concentrations of AEA for 2 h, followed by gene expression analysis of genes relevant for biofilm formation, adherence and hyphal morphogenesis (Tables 1, 2 and 3). Some genes were upregulated including the ALS1 adhesion molecule, the transcription factor TEC1 involved in hyphal development and the transcriptional repressor NRG1 that prevents filamentous growth (Table 1). ALS1 and TEC1 were mainly upregulated at the lower concentrations (10 and 50 μg/ml AEA), while NRG1 was upregulated at the higher concentrations (50–250 μg/ml AEA). Of note, the three multidrug efflux transporters MDR1, CDR1 and CDR2 were strongly upregulated (Table 1). On the other hand, AEA repressed the expression of the adhesins HWP1 and ALS3, the cell elongation protein ECE1, the signal transduction regulators HGC1 and RAS1 and the transcription regulators EFG1 and ZAP1 (Table 2). Also the cell hydrophobicity-associated protein CSH1 was strongly repressed as well as the virulence factor phospholipase D1 (PLD1) (Table 2). There were also several genes that were not significantly affected by AEA including the cell wall adhesion EAP1 and the anti-adhesive protein YWP1 (Table 3). Altogether, these alterations in gene expression may explain, at least in part, the inhibition of hyphal growth by AEA and the reduced adherence of AEA-treated hyphae to epithelial cells.

Table 1.

Genes that are upregulated in C. albicans after a 2 h-incubation with AEA.

| Gene | AEA conc (μg/ml) | Fold change | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALS1 | 10 | + 1.9 ± 0.5* | Major cell surface adhesion protein which mediates yeast-to-host tissue adherence and yeast aggregation |

| 50 | + 4.1 ± 1.3* | ||

| 125 | n.s | ||

| 250 | n.s | ||

| TEC1 | 10 | + 2.1 ± 0.4* | Transcription factor of the TEA/ATTS family which regulates genes involved in hyphal development, cell adhesion, biofilm development, and virulence |

| 50 | + 3.9 ± 1.3* | ||

| 125 | n.s | ||

| 250 | n.s | ||

| NRG1 | 10 | n.s | Transcriptional repressor of filamentous growth |

| 50 | + 2.2 ± 0.7* | ||

| 125 | + 2.6 ± 1.0* | ||

| 250 | + 2.0 ± 0.3* | ||

| MDR1 | 10 | − 3.0 ± 0.3* | Multidrug resistance protein 1 |

| 50 | n.s | ||

| 125 | + 2.5 ± 1.1* | ||

| 250 | n.s | ||

| CDR1 | 10 | + 3.0 ± 0.3* | Pleiotropic ABC efflux transporter of multiple drugs |

| 50 | + 4.8 ± 1.6* | ||

| 125 | + 1.6 ± 0.4* | ||

| 250 | n.s | ||

| CDR2 | 10 | + 5.7 ± 0.6* | Multidrug efflux transporter |

| 50 | + 8.5 ± 2.9* | ||

| 125 | + 5.2 ± 2.4* | ||

| 250 | + 3.4 ± 0.1* |

n.s not significant.

*p < 0.05.

Table 2.

Genes that are downregulated in C. albicans after a 2 h-incubation with AEA.

| Gene | AEA conc. (μg/ml) | Fold change | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| HWP1 | 10 | n.s | A major hyphal cell wall protein that acts as an adhesin and is required for normal hyphal development and cell-to-cell adhesive functions |

| 50 | − 2.4 ± 0.6* | ||

| 125 | − 3.6 ± 1.2* | ||

| 250 | − 2.3 ± 0.3* | ||

| ALS3 | 10 | − 1.5 ± 0.3* | Agglutinin-like protein 3 acts as an adhesin that is involved in cell–cell and cell-surface interactions of hyphae |

| 50 | − 2.8 ± 0.6* | ||

| 125 | − 5.2 ± 1.4* | ||

| 250 | − 5.2 ± 0.6* | ||

| HGC1 | 10 | − 1.3 ± 0.1* | Hypha-specific G1 cyclin-related protein 1 that regulates the CDC28 kinase during hyphal growth |

| 50 | − 1.8 ± 0.4* | ||

| 125 | − 3.0 ± 0.1* | ||

| 250 | − 4.0 ± 0.2* | ||

| RAS1 | 10 | − 2.0 ± 0.3* | Ras-like protein 1, a GTPase that regulates both the MAP kinase signaling pathway and the cAMP signaling pathway |

| 50 | − 1.9 ± 0.4* | ||

| 125 | − 2.5 ± 0.6* | ||

| 250 | − 4.5 ± 0.3* | ||

| EFG1 | 10 | n.s | Enhanced filamentous growth protein 1 is a basic helix-loop helix transcriptional transcription factor that regulates the switch between the white and opaque states |

| 50 | − 2.4 ± 0.5* | ||

| 125 | − 1.8 ± 0.4* | ||

| 250 | − 1.7 ± 0.4* | ||

| ZAP1 | 10 | − 3.7 ± 0.5* | Zinc-response transcription factor that activates zinc acquisition genes that are necessary for proliferation |

| 50 | − 4.2 ± 1.1* | ||

| 125 | − 2.4 ± 0.5* | ||

| 250 | − 5.2 ± 0.6* | ||

| CSH1 | 10 | − 2.0 ± 0.2* | Cell surface hydrophobicity-associated protein |

| 50 | − 3.3 ± 0.8* | ||

| 125 | − 2.5 ± 0.6* | ||

| 250 | − 14.2 ± 2.6* | ||

| ECE1 | 10 | − 1.8 ± 0.3* | Extent of cell elongation protein 1 is involved in biofilm formation |

| 50 | − 2.4 ± 0.5* | ||

| 125 | − 2.2 ± 0.8* | ||

| 250 | − 2.6 ± 0.3* | ||

| PLD1 | 10 | − 1.5 ± 0.1* | Phospholipase |

| 50 | − 2.1 ± 0.4* | ||

| 125 | − 3.2 ± 0.7* | ||

| 250 | − 6.3 ± 1.2* |

n.s not significant.

*p < 0.05.

Table 3.

Genes that are not significantly affected in C. albicans after a 2 h-incubation with AEA.

| Function | Gene |

|---|---|

| EAP1 | Cell wall adhesin EAP1, Cell wall protein which mediates cell–cell and cell-substrate adhesion. Required for biofilm formation and plays a role in virulence |

| YWP1 | Yeast-form wall Protein 1, Cell wall protein which plays an anti-adhesive role and promotes dispersal of yeast forms, which allows the organism to seek new sites for colonization |

| FKS1 | Beta-1,3-glucan synthase catalytic subunit 1 |

| GSP1 | GTP-binding nuclear protein GSP1/ran |

| CDC35 | Adenylyl cyclase |

| CST20 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase, MAP4K, required for hyphal formation and virulence |

| HST7 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase |

| CPH1 | Transcription factor involved in the formation of pseudohyphae and hyphae |

| EFB1 | Elongation factor 1-beta |

| UME6 | Transcription factor regulating filamentous growth |

| TUP1 | Transcription corepressor that represses filamentous growth |

| EED1 | A key regulator of hyphal maintenance |

Discussion

Candidiasis is a major health problem where Candida species forms biofilm on endothelial and epithelial cells. In immunosuppressed people it can lead to systemic infection and even death6,22. The oral cavity, the genitourinary tract and the intestine are the most frequent infection sites. It is important to find treatments that can interfere with the early adhesion of the fungi to the host cells. Here we have shown that treatment of C. albicans with either AEA or AraS strongly reduced their adherence to cervical epithelial cells, making them potential drugs in the co-treatment of this infectious disease. Not only do these compounds affect the hyphal attachment to epithelial cells, but they also lead to a strong reduction in the hyphal length in comparison to control. The appearance of shorter hyphae in the AEA and AraS-treated samples is a direct result of their inhibitory effect on hyphal growth. These compounds were also shown to prevent the yeast-hypha transition. Since the hyphae are associated with higher infectivity than the yeast form6,22, the perturbation of hyphal growth by AEA and AraS might be beneficial in reducing the virulence of C. albicans. Of note, AEA didn't affect the biofilm formation on polystyrene plastic surface, suggesting different requirements for the two modes of adhesion.

In order to gain better insight into the action mechanism of AEA, we undertook a gene expression study focusing on genes relevant to adhesion, biofilm formation and hyphal morphogenesis. We found genes that were upregulated by AEA, others that were down-regulated and even others that were not significantly affected. Of the genes whose expression was altered by AEA, the upregulation of ALS1, TEC1 and NRG1 and the downregulation of HWP1, ALS3, HGC1, RAS1, ZAP1, CSH1, ECE1 and PLD1 were the most outstanding. Als1, Als3 and Hwp1 are adhesins that are involved in the attachment of C. albicans to epithelial cells7,12,23–26. Eap1 and Als1 are important for the initial attachment to a surface, while Hpw1 and Als3 are important for the stable attachment to epithelial cells2,6. EAP1 expression was unaffected by AEA, while ALS1 was only upregulated at the lower AEA concentrations (10–50 μg/ml). The upregulation of ALS1 showed a similar pattern to that of the transcription factor TEC1, which is known to regulate ALS1 expression6. In contrast, HPW1 and ALS3 were downregulated at the higher AEA concentrations (50–250 μg/ml), an effect that seems to outweigh the upregulation of ALS1. This conclusion is based on the observation that C. albicans strains lacking HWP1 are unable to form stable attachments to human buccal epithelial cells23, and specific antibodies to Als3 blocks C. albicans adhesion to vascular endothelial cells and buccal epithelial cells24. The downregulation of HWP1 and ALS3 together with the simultaneous downregulation of ECE1, which is also known to support adhesion26, might explain, at least partly, the reduced adhesion of AEA-treated C. albicans to epithelial cells.

Interesting is the AEA-mediated downregulation of RAS1, an upstream regulator of the Cdc35/cAMP/PKA/Efg1 and the Cdc24/Cst20/Hst7/Cph1 MAPK signal transduction pathways that regulate hyphal morphogenesis6,22. Ras1 is considered a master hyphal regulator and mutant RAS1 strains show severe defects in hyphal growth27 and reduced adherence to epithelial cells12. Alteration in RAS1 levels by AEA has thereby direct influence on hyphae formation and adhesion to epithelial cells. In addition, AEA reduced the gene expression of hyphal-promoting transcription factor EFG1 whose activity is affected by the Ras1/Cdc35/cAMP/PKA pathway, while it had no significant effect on the expression of the hyphal-promoting transcription factor CPH1 that is affected by the Ras1/Cdc24/Cst20/Hst7 MAPK pathway. Efg1 has been shown to be required for the adhesion of fungi to both reconstituted human epidermis and reconstituted intestinal epithelium28 and the cAMP/PKA/Efg1 signal transduction pathway has been demonstrated to be necessary for all stages of oral C. albicans infection12. Efg1 is an upstream regulator of the adhesins ALS1, ALS3, ECE1 and HWP129. The gene expression of the intermediate mediators CDC35, CST20, HST7 were, however, unaffected by AEA. Since the signals transmitted by Ras1 are reduced by AEA, the activity of these intermediate mediators as well as the activity of the transcription factors Efg1 and Chp1 will consequently be dampened, resulting in retarded hyphal morphogenesis. The retardation of hyphae growth might further be effectuated by the prominent downregulation of the hypha-specific G1 cyclin-related protein 1 (HGC1) that regulates the Cdc28 kinase during hyphal growth30. On top of these effects, the AEA-mediated upregulation of NRG1, a transcriptional repressor of filamentous growth31, may further contribute to the observed reduction in hyphae length and size. Nrg3 has been shown to repress the expression of ALS329, ECE131 and HPW131. Thus the upregulation of NRG1 together with the downregulation of EFG1 may fortify the repression of the adhesin genes. Moreover, the AEA-mediated downregulation of the zinc-responsive transcription factor ZAP1 that is known to be required for efficient hyphae formation32,33, might have an additional impact. Altogether, the combined alterations in gene expression caused by AEA might explain both the AEA-induced inhibition of hyphal growth and the reduced adherence of AEA-treated hyphae to epithelial cells.

AEA and 2-AG were originally discovered to be endocannabinoids that bind to the cannabinoid receptor CB134. It later emerged that AEA has anti-anxiety activities by regulating the neurotransmitter system by being a retrograde synaptic messenger35,36. AEA binds also to other membrane molecules in mammalian besides CB1 including CB2, GRP55 (CB3) and TRPV136. AEA usually does not bind to the extracellular part of the receptors, but rather, its binding domain is frequently located deep in the plasma membrane37. The interactions of AEA with membrane-bound cholesterol and ceramides facilitate its transport to the receptor binding domains37. The binding of AEA to TRPV1 leads to transient calcium influx in neurons38. It remains to be determined whether AEA also affects calcium influx in fungi.

In conclusion, AEA and AraS prevent yeast-hyphae transition, inhibit hyphal growth and reduce the ability of C. albicans hyphae to adhere to epithelial cells. This is, among others, achieved by altered expression of genes involved in cell–cell interaction and of genes regulating hyphal morphogenesis.

Material and methods

Chemicals

Anandamide (AEA), N-arachidonoyl serine (AraS) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) were synthesized as described39–41 and dissolved in ethanol. We also purchased anandamide from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), and N-arachidonoyl serine (AraS) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) from Cayman Chemical.

Cell lines

HeLa cervical carcinoma cells were cultivated in DMEM (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 8% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS; Biological Industries, Beth HaEmek, Israel), 2 mM L-glutamine and 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Fungal strain and growth conditions

C. albicans SC5314 that has the GFP gene integrated within the ENO1 genomic locus42, was kindly provided by Prof. J. Berman (Tel Aviv University, Israel). The fungi were first seeded on potato-dextrose agar plates (Acumedia, Neogen, Lansing, MI) at room temperature where they grow in the yeast form, and then inoculated in RPMI (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for a 16–18 h incubation at 37 °C to let them form hyphae. For the yeast-hypha transition assay, colonies of C. albicans in yeast form were inoculated in RPMI at an OD600nm of 0.5 and incubated with different concentrations of AEA, AraS and 2-AG at 37 °C for 4 h. For time-lapse microscopy, hyphae that has been formed after 4 h incubation of C. albicans in yeast form (OD600nm of 0.25) at 37 °C, were incubated in 300 μl RPMI in a μ-slide 8 well chambered coverslip (ibidi GmbH, Martinsried, Germany) in the absence or presence of 125 μg/ml AEA. The Okolab incubation chamber was used to maintain the temperature at 37 °C. Images were captured each 5 min for 3 h using the Nikon spinning disk microscope (Yokogawa W1), the × 20 CFI PLAN APO VC objective and the SCMOS ZYLA camera. The images were processed using the NIS-Element AR program.

Biofilm formation on plastic culture plates

C. albicans that have been cultivated overnight in RPMI at 37 °C, were resuspended and diluted to an OD600nm of 0.25 in RPMI and then seeded in 96-flat bottomed microplates (Corning, NY) in 200 μl RPMI with different concentrations of test compounds per well. Following an overnight incubation at 37 °C, the biofilms formed in the wells were washed twice with PBS and stained for 20 min with 1% crystal violet. The stained biofilms were washed twice with DDW and after drying, the stain was dissolved in 200 μl of 33% acetic acid and the absorbance read in a Tecan M200 microplate reader at 595nm20.

C. albicans adherence to HeLa cells

The adherence assay was performed by a slight modification of Feldman et al.43. Two hundred and fifty thousand HeLa cells were seeded in 1 ml DMEM supplemented with 8% FCS in 24 well tissue culture plate (Corning, NY) the day before assay. At the following morning, the medium was changed to 1 ml of RPMI supplemented with 1% FCS. C. albicans that have grown for 16–18 h at 37 °C, were resuspended in fresh RPMI to an OD of 1.0, and then exposed to different concentrations of AEA, 2-AG, AraS or corresponding concentrations of ethanol for 1 h serving as controls. Thereafter, 100 μl of the pretreated C. albicans were added to the 1 ml HeLa cell cultures, and the co-culture incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. At the end of incubation, the cells were washed twice with 1 ml PBS and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) in PBS for 30 min. The co-cultures were visualized using NIKON confocal microscope and the NIS-Element AR software. Quantitative analysis of GFP was done using the ImageJ software. For each sample 8–10 images were taken and each image was analyzed for the amount of GFP. The percentage adherence was calculated according to relative GFP staining. In addition, the length of the hyphae was measured using the Adobe Photoshop software. Between 50 and 100 fungi were measured per sample.

Real-time quantitative PCR

C. albicans that have been grown overnight in RPMI at 37 °C were treated for 2 h with various concentrations of AEA or corresponding concentrations of ethanol. At the end of incubation, the RNA was extracted from the fungi using TRI-Reagent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO)44. Cell disruption was done in 1 ml TRI-Reagent in the presence of 200 μl 1 mm acid-washed glass beads (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) with the aid of a FastPrep cell disrupter (BIO 101, Savant Instrument). The purified RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the qScript cDNA synthesis kit (Quantabio, Beverly, MA) and PCR amplification was done in a CFX96 BioRad Connect Real-Time PCR apparatus using Power Sybr Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, ThermoFischer Scientific) on 2 ng cDNA in the presence of 300 nM forward/reverse primer sets (Table 4). PCR conditions included an initial heating at 50 °C for 2 min, an activation step at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of amplification (95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 1 min). Calculations were done according to the 2−ΔΔCt method, where both 18S rRNA and ACT1 were used as reference genes.

Table 4.

Primers used for real-time PCR.

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| 18S rRNA | TCTTCTTGATTTTGTGGGTGG | TCGATAGTCCCTCTAAGAAGTG |

| ACT1 | AAGAATTGATTTGGCTGGTAGAGA | TGGCAGAAGATTGAGAAGAAGTTT |

| ALS1 | TTGGGTTGGTCCTTAGATGG | ATGATTTCAAAGCGTCGTTC |

| ALS3 | TAATGCTGCTACGTATAATT | CCTGAAATTGACATGTAGCA |

| CDC35 | TTCATCAGGGGTTATTTCAC | CTCTATCAACCCGCCATTTC |

| CDR1 | GTACTATCCATCAACCATCAGCACTT | GCCGTTCTTCCACCTTTTTGTA |

| CDR2 | TGCTGAACCGACAGACTCAGTT | AAGAGATTGCCAATTGTCCCATA |

| CPH1 | ATGCAACACTATTTATACCTC | CGGATATTGTTGATGATGATA |

| CSH1 | CTGTCGGTACTATGAGATTG | GATGAATAAACCCAACAACT |

| CST20 | TTCTGACTTCAAAGACATCAT | AATGTCTATTTCTGGTGGTG |

| EAP1 | AGGCAAAGGTGGCTATCAAG | GTGCAGTCGTGTAGGAGGT |

| ECE1 | GCTGGTATCATTGCTGATAT | TTCGATGGATTGTTGAACAC |

| EED1 | AGCAACGACTTCCAAAAGGA | CGGTTTCTGGTTCGATGATT |

| EFB1 | GCTGCTAAAGGTCCAAAACC | CATCCCATGGTTTGACATCC |

| EFG1 | TATGCCCCAGCAAACAACTG | TTGTTGTCCTGCTGTCTGTC |

| FKS1 | CGTGAAATTGATCATGCCTGTAC | AACCCTTCTGGGCTCCAAA |

| GSP1 | TGAAGTCCATCCATTAGGAT | ATCTCTATGCCAGTTTGGAA |

| HGC1 | AATTGAGGACCTTTTGAATGGAAA | AAAGCTGTGATTAAATCGGTTTTGA |

| HST7 | ACTCCAACATCCAATATAACA | TTGATTGACGTTCAATGAAGA |

| HWP1 | CACAGGTAGACGGTCAAGGT | AAGGTTCTTCCTGCTGTTGT |

| MDR1 | TCAGTCCGATGTCAGAAAATGC | GCAGTGGGAATTTGTAGTATGACAA |

| NRG1 | CCAAGTACCTCCACCAGCAT | GGGAGTTGGCAGTAAATCA |

| PLD1 | GCCAAGAGAGCAAGGGTTAGCA | CGGATTCGTCATCCATTTCTCC |

| RAS1 | GGCCATGAGAGAACAATATA | GTCTTTCCATTTCTAAATCAC |

| TEC1 | AGGTTCCCTGGTTTAAGTG | ACTGGTATGTGTGGGTGAT |

| TUP1 | CTTGGAGTTGGCCCATAGAA | TGGTGCCACAATCTGTTGTT |

| UME6 | AGCACCAAATTCGCCTTATG | AGGTTGAGCTTGCTGCAGTT |

| YWP1 | GCTACTGCTACTGGTGCTA | AACGGTGGTTTCTTGAC |

| ZAP1 | ATCTGTCCAGTGTTGTTTGTA | AGGTCTCTTTGAAAGTTGTG |

Statistical analysis

Experiments were performed in triplicates and repeated twice. Results are presented as average of data obtained from three experiments ± standard error. Results are considered to be statistically significant when the p value was less than 0.05 using the Student's t-test.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was partially supported by Agriculture Ministry of Israel. We are grateful to Dr. Yael Feinstein-Rotkopf for operating the Nikon spinning scan microscope at our Interdepartment Core Research Facility. We thank Muna Aqawi and Sarah Gingichashvili for their support.

Abbreviations

- AEA

Anandamide, N-arachidonoylethanolamine

- 2-AG

2-Arachidonoylglycerol

- ALS1

Agglutinin-like sequence protein 1

- ALS3

Agglutinin-like sequence protein 3

- AraS

N-Arachidonoyl serine

- BCR1

Biofilm and cell wall regulator 1

- CDC35

Cell-division-cycle gene 35

- CPH1

Candida pseudohyphal regulator 1, a homolog of STE12-like transcription factor

- CSH1

Cell surface hydrophobicity associated protein 1

- CST20

C. albicans homologous to the p21-activated kinase (PAK) kinase Ste20, a serine/threonine protein kinase

- CZF1

C. albicans Zinc finger protein, a transcription factor

- EAP1

Enhanced adherence to polystyrene 1

- ECE1

Extent of cell elongation protein 1

- EED1

Epithelial escape and dissemination 1, a transcriptional regulator

- EFB1

Elongation factor 1-beta.

- EFG1

Enhanced filamentous growth protein 1

- FKS1

FK506 sensitivity, a 1,3-beta-glucan synthase

- GSP1

Genetic suppressor of Prp20-1, a GTP-binding nuclear protein

- HGC1

Hypha-specific G1 cyclin-related protein 1

- HST7

Homologous to the MAPK kinase (MAPKK) Ste7, a serine/threonine protein kinase

- HWP1

Hyphal wall protein 1

- MDR1

Multidrug resistance protein 1

- CDR1

Candida drug resistance 1, an ATP-dependent multidrug transporter 1

- CDR2

Candida drug resistance 2, an ATP-dependent multidrug transporter 2

- MKC1

Mitogen-activate protein kinase from C. albicans

- NRG1

Negative regulator of glucose-repressed genes 1, a transcriptional regulator

- PGA34

Predicted GPI-anchored protein 34

- PLD1

Phospholipase D1

- RAS1

Ras-like protein 1

- TEC1

Transposon enhancement control, a TEA/ATTS transcription factor

- TUP1

dTMP-uptake, a chromatin-silencing transcriptional regulator

- UME6

Unscheduled meiotic gene expression, a transcriptional regulator

- YWP1

Yeast-form wall protein 1

- ZAP1

Zinc-responsive activator protein 1

Author contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: R.S.V., M.F. and D.S. Performed the experiments: R.S.V. Analysed the data: R.S.V. Synthesized the reagents: R.S. and R.M. Wrote and reviewed the paper: R.S.V., M.F., R.S., R.M. and D.S.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-70650-6.

References

- 1.Kim J, Sudbery P. Candida albicans, a major human fungal pathogen. J. Microbiol. 2011;49:171–177. doi: 10.1007/s12275-011-1064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan Y, He H, Dong Y, Pan H. Hyphae-specific genes HGC1, ALS3, HWP1, and ECE1 and relevant signaling pathways in Candida albicans. Mycopathologia. 2013;176:329–335. doi: 10.1007/s11046-013-9684-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumamoto CA. A contact-activated kinase signals Candida albicans invasive growth and biofilm development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:5576–5581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407097102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giusani AD, Vinces M, Kumamoto CA. Invasive filamentous growth of Candida albicans is promoted by Czf1p-dependent relief of Efg1p-mediated repression. Genetics. 2002;160:1749–1753. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.4.1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lohse MB, Gulati M, Johnson AD, Nobile CJ. Development and regulation of single- and multi-species Candida albicans biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018;16:19–31. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finkel JS, Mitchell AP. Genetic control of Candida albicans biofilm development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;9:109–118. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phan QT, et al. Als3 is a Candida albicans invasin that binds to cadherins and induces endocytosis by host cells. PLoS. Biol. 2007;5:e64. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cleary IA, et al. Candida albicans adhesin Als3p is dispensable for virulence in the mouse model of disseminated candidiasis. Microbiology. 2011;157:1806–1815. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.046326-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuchimori N, et al. Reduced virulence of HWP1-deficient mutants of Candida albicans and their interactions with host cells. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:1997–2002. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.1997-2002.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moyes DL, et al. Candidalysin is a fungal peptide toxin critical for mucosal infection. Nature. 2016;532:64–68. doi: 10.1038/nature17625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kasper L, et al. The fungal peptide toxin Candidalysin activates the NLRP3 inflammasome and causes cytolysis in mononuclear phagocytes. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4260. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06607-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wächtler B, Wilson D, Haedicke K, Dalle F, Hube B. From attachment to damage: defined genes of Candida albicans mediate adhesion, invasion and damage during interaction with oral epithelial cells. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freitas HR, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and endocannabinoids in health and disease. Nutr. Neurosci. 2018;21:695–714. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2017.1347373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murillo-Rodriguez E, Pastrana-Trejo JC, Salas-Crisostomo M, de-la-Cruz M. The endocannabinoid system modulating levels of consciousness, emotions and likely dream contents. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets. 2017;16:370–379. doi: 10.2174/1871527316666170223161908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engel MA, et al. Ulcerative colitis in AKR mice is attenuated by intraperitoneally administered anandamide. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2008;59:673–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muller C, Morales P, Reggio PH. Cannabinoid ligands targeting TRP channels. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018;11:487. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pacher P, Kogan NM, Mechoulam R. Beyond THC and endocannabinoids. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2020;60:637–659. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010818-021441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baggelaar MP, Maccarrone M, van der Stelt M. 2-Arachidonoylglycerol: a signaling lipid with manifold actions in the brain. Prog. Lipid. Res. 2018;71:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2018.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang X, Maor Y, Wang JF, Kunos G, Groopman JE. Endocannabinoid-like N-arachidonoyl serine is a novel pro-angiogenic mediator. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010;160:1583–1594. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00841.xBPH841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feldman M, Smoum R, Mechoulam R, Steinberg D. Antimicrobial potential of endocannabinoid and endocannabinoid-like compounds against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:17696. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35793-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feldman M, Smoum R, Mechoulam R, Steinberg D. Potential combinations of endocannabinoid/endocannabinoid-like compounds and antibiotics against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0231583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sudbery PE. Growth of Candida albicans hyphae. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;9:737–748. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Staab JF, Bradway SD, Fidel PL, Sundstrom P. Adhesive and mammalian transglutaminase substrate properties of Candida albicans Hwp1. Science. 1999;283:1535–1538. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coleman DA, et al. Monoclonal antibodies specific for Candida albicans Als3 that immunolabel fungal cells in vitro and in vivo and block adhesion to host surfaces. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2009;78:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fu Y, et al. Expression of the Candida albicans gene ALS1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae induces adherence to endothelial and epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:1783–1786. doi: 10.1128/IAI.66.4.1783-1786.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nobile CJ, et al. Critical role of Bcr1-dependent adhesins in C. albicans biofilm formation in vitro and in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e63. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng Q, Summers E, Guo B, Fink G. Ras signaling is required for serum-induced hyphal differentiation in Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:6339–6346. doi: 10.1128/JB.181.20.6339-6346.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dieterich C, et al. In vitro reconstructed human epithelia reveal contributions of Candida albicans EFG1 and CPH1 to adhesion and invasion. Microbiology. 2002;148:497–506. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-2-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bastidas RJ, Heitman J, Cardenas ME. The protein kinase Tor1 regulates adhesin gene expression in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000294. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bishop A, et al. Hyphal growth in Candida albicans requires the phosphorylation of Sec2 by the Cdc28-Ccn1/Hgc1 kinase. EMBO J. 2010;29:2930–2942. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braun BR, Kadosh D, Johnson AD. NRG1, a repressor of filamentous growth in C. albicans, is down-regulated during filament induction. EMBO J. 2001;20:4753–4761. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim MJ, Kil M, Jung JH, Kim J. Roles of Zinc-responsive transcription factor Csr1 in filamentous growth of the pathogenic Yeast Candida albicans. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008;18:242–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nobile CJ, et al. Biofilm matrix regulation by Candida albicans Zap1. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mechoulam R, Hanus LO, Pertwee R, Howlett AC. Early phytocannabinoid chemistry to endocannabinoids and beyond. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014;15:757–764. doi: 10.1038/nrn3811[pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radhakrishnan R, Ross DA. From, "Azalla" to anandamide: Distilling the therapeutic potential of cannabinoids. Biol. Psychiatry. 2018;83:e27–e29. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maccarrone M, et al. Endocannabinoid signaling at the periphery: 50 years after THC. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2015;36:277–296. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.02.008S0165-6147(15)00034-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Di Scala C, Fantini J, Yahi N, Barrantes FJ, Chahinian H. Anandamide revisited: how cholesterol and ceramides control receptor-dependent and receptor-independent signal transmission pathways of a lipid neurotransmitter. Biomolecules. 2018 doi: 10.3390/biom8020031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fenwick AJ, et al. Direct anandamide activation of TRPV1 produces divergent calcium and current responses. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017;10:200. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Devane WA, et al. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science. 1992;258:1946–1949. doi: 10.1126/science.1470919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milman G, et al. N-arachidonoyl L-serine, an endocannabinoid-like brain constituent with vasodilatory properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:2428–2433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510676103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mechoulam R, et al. Identification of an endogenous 2-monoglyceride, present in canine gut, that binds to cannabinoid receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1995;50:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00109-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gerami-Nejad M, Zacchi LF, McClellan M, Matter K, Berman J. Shuttle vectors for facile gap repair cloning and integration into a neutral locus in Candida albicans. Microbiology. 2013;159:565–579. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.064097-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feldman M, Tanabe S, Howell A, Grenier D. Cranberry proanthocyanidins inhibit the adherence properties of Candida albicans and cytokine secretion by oral epithelial cells. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012;12:6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feldman M, Al-Quntar A, Polacheck I, Friedman M, Steinberg D. Therapeutic potential of thiazolidinedione-8 as an antibiofilm agent against Candida albicans. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e93225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.