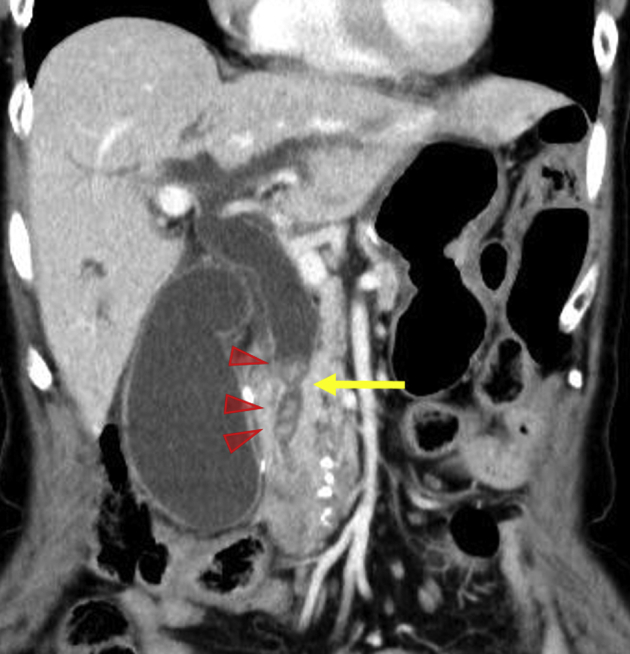

A 75-year-old woman who previously underwent distal gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction had acute calculous cholangitis with continuous abdominal pain, jaundice, and signs indicating sepsis. Enhanced CT revealed a stricture at the distal bile duct with multiple stones both upstream and downstream (Fig. 1). Acute cholangitis improved after percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PTGBD) as a temporizing intervention (endoscopic intervention was avoided because of the patient’s unstable condition).

Figure 1.

Enhanced CT showing a stricture at the distal bile duct and stones obstructing the biliary system. Arrow, biliary stricture; arrowheads, stones.

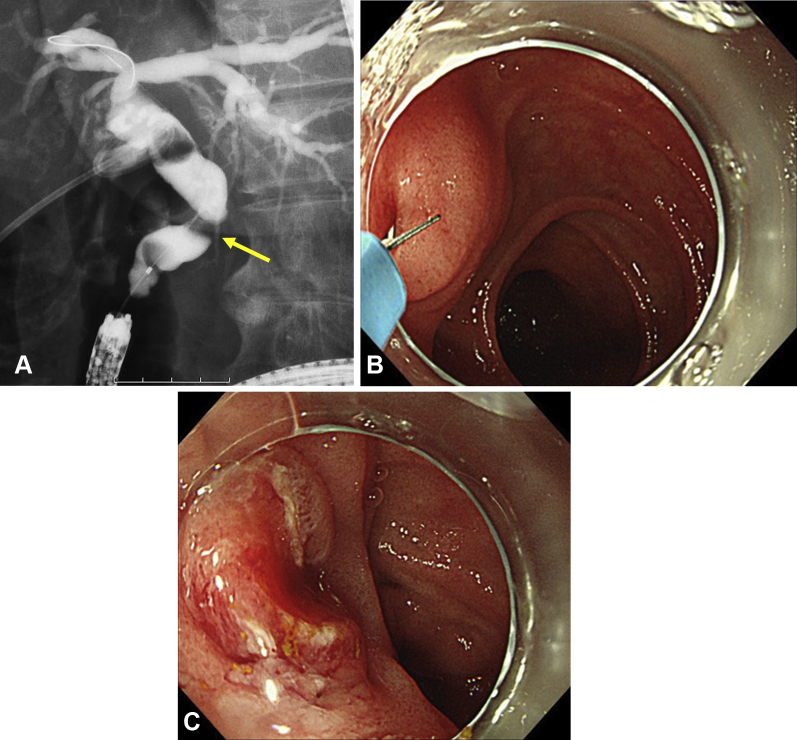

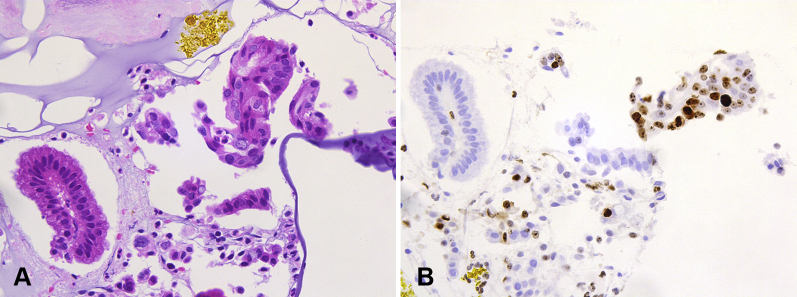

Using a single-balloon enteroscope, we performed endoscopic sphincterotomy to prevent recurrence of biliary stone incarceration involving the pancreatic duct, which occurred at the onset with highly elevated levels of serum pancreatic enzymes (Fig. 2). Stone removal was not attempted because the biliary orifice could not be opened wide enough using a simple needle-knife endoscopic sphincterotomy without large balloon dilation, which might induce biliary perforation because of the immovable stones pressed against the biliary wall.1 Forceps (Radial Jaw 4; Boston Scientific, Marlborough, Mass, USA) biopsy of the stricture strongly indicated adenocarcinoma (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography using a single-balloon enteroscope. A, Cholangiogram showing stones on both the hilar and ampullary sides of the stricture (arrow). B, C, Endoscopic views showing endoscopic sphincterotomy using a needle knife.

Figure 3.

Biopsy specimen from the bile duct stricture strongly indicating adenocarcinoma. A, H&E, orig. mag. X40. B, Ki-67 staining showing 40% of positive cells.

Because the patient refused surgery, permanent biliary drainage was needed. However, transpapillary drainage appeared unfavorable because metal stents could press the stones against the bile duct wall and plastic stents would have limited patency, resulting in frequent enteroscopic exchange. Moreover, EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy (HGS) may become impossible once the bile duct shrinks after transpapillary drainage and removal of the percutaneous tube, which can be blocked. Therefore, we thought that EUS-HGS without transpapillary drainage was the best intervention.

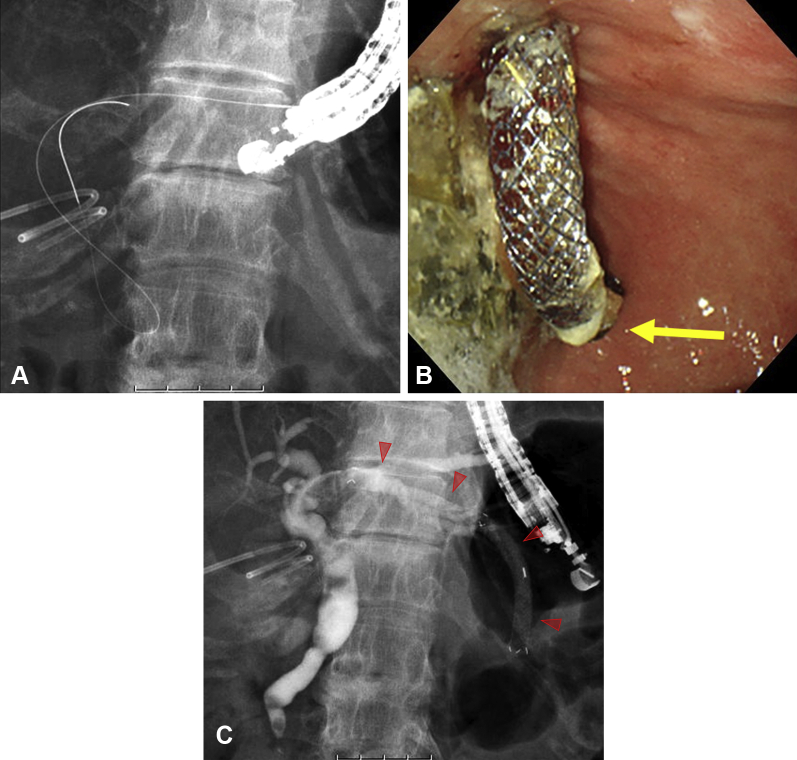

After an 8-day block of the PTGBD tube, EUS-HGS was performed (Video 1, available online at www.VideoGIE.org). A B3 branch with a diameter of 4 mm was punctured using a 22-gauge needle (Expect; Boston Scientific) equipped with a 0.018-inch guidewire (Fielder; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) (Fig. 4). After dilation and contrast injection using a 7F bougie dilator dedicated to 0.018-inch wires with a tapered tip (ES Dilator; Zeon Medical Inc, Tokyo, Japan), a fully covered metal stent (Hanaro, 6 mm in diameter, 10 cm in length; M.I.Tech Co, Ltd, Pyeongtaek, South Korea) was placed, bridging the biliary system and remnant stomach (Fig. 5). No procedure-related adverse events were observed. After confirming that biliary obstruction did not recur when blocking the PTGBD tube, the percutaneous tube was removed 5 days after EUS-HGS.

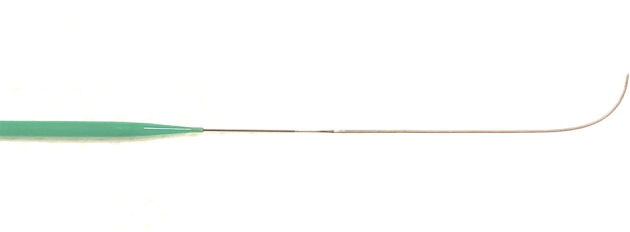

Figure 4.

The newly developed 0.018-in Fielder guidewire and dedicated ES Dilator with a minimal difference in diameters.

Figure 5.

EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy using a new 0.018-inch Fielder guidewire in combination with a 22-gauge needle and a dedicated dilator. A, The guidewire was inserted through the needle punctured into a B3 branch. B, Endoscopic view showing a 6-mm, 10-cm fully covered metal stent (Hanaro) bridging the stomach and bile duct. Arrow, the puncture point. C, Fluoroscopic view when completing the procedure. Arrowheads, the metal stent.

The newly developed Fielder 18 guidewire appears to have high maneuverability to access target ducts and sufficient stiffness for advancing devices, as shown in Video 1. The ES Dilator for the diameter of this guidewire enabled seamless dilation, which is the most important but sometimes difficult process in EUS-guided drainage procedures.2 Owing to the stability of the wire for dilator and stent deliveries, there was no need to exchange the wire to a stiffer one, which would prolong procedure times. These thinner devices using a 22-gauge needle might facilitate the EUS-guided drainage of tiny targets that has been performed using a 19-gauge needle plus 0.025-inch guidewire. Smaller needles increase both the ability to puncture small targets and the accessibility of locations because of the wide movement of the endoscope angle and the device elevator.

In previous reports on EUS-guided drainage using a 0.018-inch guidewire, use was limited to the rendezvous manner3 or placement of small-caliber devices (4F balloon and 3F plastic stent)4 because of their poor stability and a lack of usable dilators. The Fielder 18 guidewire, which will become commercially available soon, has the potential to be the first-line device in combination with a 22-gauge needle for EUS-guided drainage of tiny ducts, warranting further studies.

Disclosure

All authors disclose no financial relationships.

Supplementary data

With an oblique-viewing linear echoendoscope UCT260 from Olympus, a B3 branch without intervening vessels was punctured using a 22-G EUS-FNA Expect needle. After guidewire insertion toward the ampullary side, an ES Dilator, which was dedicated for this new guidewire, was smoothly inserted. Subsequently, without guidewire exchange, a 6 mm wide, 10 cm long metal stent was advanced and deployed, bridging the bile duct and stomach.

References

- 1.Shimatani M., Takaoka M., Mitsuyama T. Complication of endoscopic papillary large-balloon dilation using double-balloon endoscopy for biliary stones in a postoperative patient. Endoscopy. 2014;46:E390. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1377387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanno Y., Ito K., Koshita S. Efficacy of a newly developed dilator for endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;9:304–309. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i7.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martínez B., Martínez J., Casellas J.A. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided rendezvous in benign biliary or pancreatic disorders with a 22-gauge needle and a 0.018-inch guidewire. Endosc Int Open. 2019;7:E1038–E1043. doi: 10.1055/a-0918-5931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayat U., Freeman M.L., Trikudanathan G. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided pancreatic duct intervention and pancreaticogastrostomy using a novel cross-platform technique with small-caliber devices. Endosc Int Open. 2020;8:E196–E202. doi: 10.1055/a-1005-6573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

With an oblique-viewing linear echoendoscope UCT260 from Olympus, a B3 branch without intervening vessels was punctured using a 22-G EUS-FNA Expect needle. After guidewire insertion toward the ampullary side, an ES Dilator, which was dedicated for this new guidewire, was smoothly inserted. Subsequently, without guidewire exchange, a 6 mm wide, 10 cm long metal stent was advanced and deployed, bridging the bile duct and stomach.