Key Points

Question

What is the most cost-effective infection control strategy for reducing hospital-onset Clostridioides difficile infection?

Findings

In this economic evaluation study, an agent-based simulation of C difficile transmission at a 200-bed model hospital found 5 dominant interventions that reduced costs and improved outcomes compared with baseline practices, as follows: daily cleaning (the most cost-effective, saving $358 268 and 36.8 quality-adjusted life-years annually), terminal cleaning, health care worker hand hygiene, patient hand hygiene, and reduced intrahospital patient transfers. The incremental cost-effectiveness of implementing multiple intervention strategies quickly decreased beyond a 2-pronged bundle.

Meaning

The findings of this study suggest that institutions should streamline infection control bundles, prioritizing a small number of highly cost-effective interventions.

This economic evaluation study compares the cost-effectiveness of 9 Clostridioides difficile single intervention strategies and 8 multi-intervention bundles.

Abstract

Importance

Clostridioides difficile infection is the most common hospital-acquired infection in the United States, yet few studies have evaluated the cost-effectiveness of infection control initiatives targeting C difficile.

Objective

To compare the cost-effectiveness of 9 C difficile single intervention strategies and 8 multi-intervention bundles.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This economic evaluation was conducted in a simulated 200-bed tertiary, acute care, adult hospital. The study relied on clinical outcomes from a published agent-based simulation model of C difficile transmission. The model included 4 agent types (ie, patients, nurses, physicians, and visitors). Cost and utility estimates were derived from the literature.

Interventions

Daily sporicidal cleaning, terminal sporicidal cleaning, health care worker hand hygiene, patient hand hygiene, visitor hand hygiene, health care worker contact precautions, visitor contact precautions, C difficile screening at admission, and reduced intrahospital patient transfers.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Cost-effectiveness was evaluated from the hospital perspective and defined by 2 measures: cost per hospital-onset C difficile infection averted and cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).

Results

In this agent-based model of a simulated 200-bed tertiary, acute care, adult hospital, 5 of 9 single intervention strategies were dominant, reducing cost, increasing QALYs, and averting hospital-onset C difficile infection compared with baseline standard hospital practices. They were daily cleaning (most cost-effective, saving $358 268 and 36.8 QALYs annually), health care worker hand hygiene, patient hand hygiene, terminal cleaning, and reducing intrahospital patient transfers. Screening at admission cost $1283/QALY, while health care worker contact precautions and visitor hand hygiene interventions cost $123 264/QALY and $5 730 987/QALY, respectively. Visitor contact precautions was dominated, with increased cost and decreased QALYs. Adding screening, health care worker hand hygiene, and patient hand hygiene sequentially to the daily cleaning intervention formed 2-pronged, 3-pronged, and 4-pronged multi-intervention bundles that cost an additional $29 616/QALY, $50 196/QALY, and $146 792/QALY, respectively.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this study suggest that institutions should seek to streamline their infection control initiatives and prioritize a smaller number of highly cost-effective interventions. Daily sporicidal cleaning was among several cost-saving strategies that could be prioritized over minimally effective, costly strategies, such as visitor contact precautions.

Introduction

Clostridioides difficile is the most common hospital-acquired infection in the United States, responsible for more than 15 000 deaths and $5 billion in direct health care costs annually.1 Health care facilities are a major source of new infections, and in-hospital prevention is critical to decreasing its overall incidence. Efforts to control C difficile infection (CDI) have intensified in recent years, with the addition of CDI to Medicare’s Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program.2 However, the results of targeted infection control initiatives have been variable, and CDI incidence continues to rise.1,3,4

Nationwide, interventions are typically implemented simultaneously in multi-intervention bundles.3 This strategy makes it impossible to identify the isolated effects of single interventions using traditional epidemiologic methods.5 However, by developing an agent-based simulation model of C difficile transmission, our group was previously able to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of 9 interventions and 8 multi-intervention bundles in a simulated general, 200-bed, adult hospital.6 All hospitals operate in a setting of constrained resources. Thus, evaluating the cost-effectiveness of common infection control interventions is essential to providing evidence-based recommendations regarding which strategies to prioritize and implement.

While several C difficile cost-effectiveness studies have been published, the overwhelming majority focus on comparing treatment or diagnostic testing modalities.7 Among those that assess infection control initiatives, most evaluate a single intervention or single bundle. To our knowledge, only 2 other studies8,9 have investigated the comparative cost-effectiveness of multiple C difficile interventions. Neither evaluated emerging patient-centered interventions, such as screening at admission or patient hand hygiene. Furthermore, both studied environmental cleaning only as a bundled strategy and did not distinguish between daily and terminal cleaning8 or daily cleaning, terminal cleaning, and hand hygiene.9 Daily cleaning and screening are highly effective in their own right,6,10,11 and an evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of single-intervention strategies such as these is essential. Thus, we aimed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of 9 infection control interventions and 8 multi-intervention bundles using an agent-based model of adult C difficile transmission.

Methods

Approach

We previously published an agent-based model of C difficile transmission in a simulated general, 200-bed, tertiary, acute care adult hospital.6 Output from this model was used to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of infection control strategies in terms of 2 primary outcomes: the cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) saved and cost per hospital-onset CDI (HO-CDI) averted. The study was reviewed and approved by the University of Wisconsin–Madison institutional review board. This study follows the recommendations of the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) reporting guideline.12

Agent-Based Model

For additional modeling details, see the eAppendix in the Supplement. Briefly, the model simulated a dynamic hospital environment and 4 agent types (ie, patients, visitors, nurses, and physicians), during a 1-year time period (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).6 Patients were categorized into 1 of 9 clinical states representing their CDI-related status. These clinical states were updated every 6 hours by a discrete-time Markov chain. Patients in the colonized, infected, recolonized, or recurrent infection states were contagious and could transmit C difficile to other agents and the environment. Once contaminated, visitors, nurses, physicians, and the environment could transmit C difficile to susceptible patients and the environment. The probability of transmission occurring during a given interaction was dependent on the agent types involved and the duration of the interaction (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Key model parameter estimates are shown in Table 1.6,10,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94 The model was developed and run in NetLogo software version 5.3.1.95 We used synchronized random numbers, which allowed us to directly compare runs under different intervention scenarios, while minimizing variability owing to chance.96

Table 1. Select Parameter Estimates for the Agent-Based Model.

| Admission parameter | Mean, % | Source | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Enhanced | Ideal | ||

| Patient length of stay, mean (SD), d | 4.8 (4.8) | 4.8 (4.8) | 4.8 (4.8) | AHA,13 2016; AHRQ,14 2012; AHRQ,15 2012; Kaboli et al,16 2012 |

| Proportion in each category at admission (total 100%) | ||||

| Susceptible patients | 39.7 | 39.7 | 39.7 | AHRQ,14 2012; CDC,17 2010; Hicks et al,18 2015; Frenk et al,19 2016; Dantes et al,20 2015 |

| Asymptomatic colonized | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.1 | Longtin et al,10 2016; Koo et al,21 2014; Alasmari et al,22 2014; Leekha et al,23 2013; Loo et al,24 2011; Eyre et al,25 2013; Nissle et al,26 2016; Kagan et al,27 2017; Gupta et al,28 2012; Hung et al,29 2013; Dubberke et al,30 2015 |

| Patients with C difficile infection | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 | Koo et al,21 2014; Kagan et al,27 2017; AHRQ,31 2009; Evans et al,32 2014 |

| Nonsusceptible patients | 53.9 | 53.9 | 53.9 | NA |

| Hand hygiene | ||||

| Effectiveness at spore removal | ||||

| Soap and water | 96 | 96 | 96 | Bettin et al,33 1994; Oughton et al,34 2009; Edmonds et al,35 2013; Jabbar et al,36 2010 |

| ABHR | 29 | 29 | 29 | |

| Compliance in standard room | ||||

| Nurse | 60 | 79 | 96 | Dierssen-Sotos et al,37 2010; Randle et al,38 2013; Monistrol et al,39 2012; Tromp et al,40 2012; Kowitt et al,41 2013; Mestre et al,42 2012; Eldridge et al,43 2006; Zerr et al,44 2005; Mayer et al,45 2011; Muto et al,46 2007; Grant and Hofmann,47 2011; Grayson et al,48 2011; Pittet et al,49 2004; Clock et al,50 2010; Birnbach et al,51 2015; Randle et al,52 2014; Birnbach et al,53 2012; Caroe Aarestrup et al,54 2016; Nishimura et al,55 1999; Randle et al,56 2010; Davis,57 2010; Srigley et al,58 2014; Cheng et al,59 2007; Hedin et al,60 2012; Gagné et al,61 2010 |

| Doctor | 50 | 71 | 91 | |

| Visitor | 35 | 55 | 84 | |

| Patient | 33 | 59 | 84 | |

| Fraction of soap and water vs ABHR use in standard room | 10 | 10 | 10 | Mestre et al,42 2012; Stone et al,62 2007 |

| Compliance in known C difficile rooma | Golan et al,63 2006; Morgan et al,64 2013; Swoboda et al,65 2007; Almaguer-Leyva et al,66 2013 | |||

| Nurse | 69 | 84 | 97 | |

| Doctor | 61 | 77 | 93 | |

| Visitor | 50 | 65 | 88 | |

| Patient | 48 | 68 | 88 | |

| Fraction soap and water vs ABHR use in known C difficile room | 80 | 90 | 95 | Zellmer et al,67 2015 |

| Contact precautions | ||||

| Gown and glove effectiveness at preventing spore contamination | 70 | 86 | 97 | Morgan et al,68 2012; Landelle et al,69 2014; Tomas et al,70 2015 |

| Health care worker compliance | 67 | 77 | 87 | Clock et al,50 2010; Morgan et al,64 2013; Weber et al,71 2007; Manian and Ponzillo,72 2007; Bearman et al,73 2007; Bearman et al,74 2010; Deyneko et al,75 2016 |

| Visitor compliance | 50 | 74 | 94 | Clock et al,50 2010; Weber et al,71 2007; Manian and Ponzillo,72 2007 |

| Environmental cleaning | ||||

| Daily cleaning compliance | 46 | 80 | 94 | Sitzlar et al,76 2013; Goodman et al,77 2008; Hayden et al,78 2006; Boyce et al,79 2009 |

| Terminal cleaning compliance | 47 | 77 | 98 | Sitzlar et al,76 2013; Hess et al,80 2013; Ramphal et al,81 2014; Anderson et al,82 2017; Clifford et al,83 2016; Carling et al,84 2008 |

| Nonsporicidal effectiveness at spore removal | 45 | 45 | 45 | Nerandzic and Donskey,85 2016; Wullt et al,86 2003 |

| Sporicidal effectiveness at spore removal | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | Wullt et al,86 2003; Perez et al,87 2005; Deshpande et al,88 2014; Block et al,89 2004 |

| Screening | ||||

| Compliance | 0 | 96 | 98 | Jain et al,90 2001; Harbath et al,91 2008 |

| PCR test | ||||

| Sensitivity | 93 | 93 | 93 | Deshpande et al,92 2011; Bagdasarian et al,93 2015; O’Horo et al,94 2012 |

| Specificity | 97 | 97 | 97 | |

| Patient transfer rate | ||||

| Intraward | 5.7 | 2.8 | 1.4 | ID |

| Interward | 13.7 | 6.8 | 3.4 | |

Abbreviations: ABHR, alcohol-based hand rub; ID, internal data; NA, not applicable; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Based on standard room estimates and standard-to-known C difficile room hand hygiene noncompliance ratio of 1.34, adapted from Barker et al.6

Interventions

We simulated the effects of 9 interventions, as follows: daily cleaning with sporicidal products; terminal cleaning with sporicidal products; patient hand hygiene; visitor hand hygiene; health care worker hand hygiene; visitor contact precautions; health care worker contact precautions; reduced intrahospital patient transfers; and screening for asymptomatic C difficile colonization at admission. Each intervention was modeled individually at an enhanced and ideal implementation level that reflected typical and optimal implementation contexts, respectively. We also simulated 8 infection control bundles that included between 2 and 5 enhanced-level interventions. Ideal-level interventions were not included in the bundle strategies because in general they did not result in considerable improvement compared with enhanced-level strategies. Thus, they were not deemed a high priority for bundle inclusion.

All strategies were compared with a baseline state, in which no interventions were enacted but standard hospital practices, such as hand hygiene, occurred at rates expected in a nonintervention context (Table 1). Ideal-level single interventions were also compared with the enhanced-level of each intervention, and bundles were compared among themselves. Each single intervention and bundle was simulated 5000 times. One replication of the simulation took approximately 115 seconds on a single core of a 1.80 GHz Intel Core i5-5350U processor with 8 GB of RAM running macOS Mojave version 10.14.3.

Cost

This study was conducted from the hospital perspective. Cost estimates (Table 21,14,62,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140) were derived from the literature and converted into 2018 US dollars using the Personal Consumption Expenditure Health Index.141 Fixed and variable costs were considered. Both were higher for corresponding ideal-level vs enhanced-level interventions. Fixed costs included the cost of additional infection control staffing to implement, support, and serially evaluate compliance with an intervention (eAppendix in the Supplement). Ideal-level interventions had increased intervention compliance. Thus, the variable costs inherent in each successful intervention event (ie, alcohol-based hand rub product, labor related to alcohol-based hand rub hygiene time) also increased. We assumed that all costs occurred in the same year as the patient’s hospital visit; therefore, costs were not discounted. The excess cost attributable to a single CDI was estimated at $12 313 (range, $6156-$18 469).100,102,142

Table 2. Infection and Infection Control–Related Cost and QALY Estimates.

| Parameter | Mean (range), 2018 US $ | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed costs | ||

| Standard education and printing materials | 1535 (556-2386) | Nelson et al,97 2016; Nyman et al,98 2011; Stone et al,62 2007 |

| Education and printing materials for serial campaignsa | 4606 (1669-7157) | Nelson et al,97 2016; Nyman et al,98 2011; Stone et al,62 2007 |

| Full-time infection preventionist salary and benefitsb | 111 527 (94 798-128 256) | Nelson et al,97 2016; Nyman et al,98 2011; BLS,99 2019 |

| PCR laboratory equipment annual overhead cost for screening | 5563 (5007-6120) | Nyman et al,98 2011 |

| Variable costs | ||

| General | ||

| Excess hospital cost attributable to C difficile infection | 12 313 (6156-18 469) | Zimlichman et al,100 2013; AHRQ,101 2017; Magee et al,102 2015 |

| Physician hourly wage and benefits, meanc | 115.34 | BLS,99 2019 |

| Nurse hourly wage and benefits, meanc | 48.58 | |

| Cleaning staff hourly wage and benefits, meanc | 18.56 | |

| Hand hygiene | ||

| Soap and water labor time, s | 23 (15-40) | Cimiotti et al,103 2004; Larson et al,104 2001; Voss and Widmer,105 1997; Girou et al,106 2002 |

| Soap and water product | 0.06 (0.03-0.10) | Stone et al,62 2007; Larson et al,104 2001; Boyce,107 2001 |

| ABHR labor time, s | 13 (5-20) | Cimiotti et al,103 2004; Larson et al,104 2001; Voss and Widmer,105 1997; Girou et al,106 2002 |

| ABHR product | 0.03 (0.02-0.04) | Stone et al,62 2007; Larson et al,104 2001 |

| Contact precautions | ||

| Donning and doffing labor time, s | 60 (35-95) | Puzniak et al,108 2004; Papia et al,109 1999 |

| Gloves product | 0.09 (0.12-0.15) | |

| Gown product | 0.75 (0.49-1.01) | |

| Environmental cleaning | ||

| UV light and fluorescent gel to assess compliance | 435 (200-500) | Glogerm110; Glitterbug111; CDC,112 2010; ID |

| Standard daily cleaning supplies per roomd | 0.91 (0.68-1.14) | Saha et al,113 2016; ID |

| Standard terminal cleaning supplies per roomd | 1.34 (1.00-1.67) | |

| Sporicidal daily cleaning supplies per roome | 1.05 (0.79-1.32) | |

| Sporicidal terminal cleaning supplies per roome | 2.19 (1.65-2.74) | |

| Daily cleaning staff labor time, min | 15 (10-20) | Doan et al,114 2012; ASHES,115 2009; ID |

| Terminal cleaning staff labor time, min | 50 (40-60) | |

| Screening | ||

| PCR test materials | 6.99 (3.69-17.67) | Curry et al,116 2011; Schroeder et al,117 2014 |

| Overhead on testing supplies, eg, delivery, storage, % | 20 | Nyman et al,98 2011 |

| Labor collection time per swab, min | 5 (3-7) | Nyman et al,98 2011 |

| Nursing assistant hourly wage and benefitsc | 19.72 | BLS,99 2019 |

| Laboratory technician time, min | 14 (10-25) | Nyman et al,98 2011; Curry et al,116 2011; Schroeder et al,117 2014; Sewell et al,140 2014 |

| Laboratory technician hourly wage and benefits, meanc | 34.83 | BLS,99 2019 |

| Patient transferf | ||

| Transport staff intraward transport labor time, min | 7 (5-15) | Hendrich and Lee,118 2005 |

| Transport staff interward transport labor time, min | 15 (7-25) | Hendrich and Lee,118 2005 |

| Transport staff hourly wage and benefits, mean | 18.84 | BLS,99 2019 |

| Handoff time, per nurse in interward transfers only, min | 10 (5-15) | Hendrich and Lee,118 2005; Catchpole et al,119 2007; Rayo et al,120 2014 |

| QALY-related estimates | ||

| Utilities | ||

| Age of healthy patients, y | ||

| 18-34 | 0.91 | Gold et al,121 1998; Swinburn and Davis,122 2013 |

| 35-64 | 0.88 | |

| 65-84 | 0.85 | |

| ≥85 | 0.83 | |

| C difficile infection | 0.81 (0.70-0.86) | Ramsey et al,123 2005; Bartsch et al,124 2012; Konijeti et al,125 2014; Tsai et al,126 2008; Thuresson et al,127 2011 |

| Age of all hospitalized patients, y | ||

| 18-34 | 14.8 | AHRQ,14 2012; AHRQ,128 2010 |

| 35-64 | 43.8 | |

| 65-84 | 31.7 | |

| ≥85 | 9.7 | |

| Age of patients with CDI, % | ||

| 18-34 y | 5.7 | AHRQ,129 2019; IDPH,130 2019 |

| 35-64 y | 31.7 | |

| 65-84 y | 44.6 | |

| ≥85 y | 18.0 | |

| Life expectancy by age, yg | ||

| 25 | 54.9 | National Vital Statistics Report,131 2014 |

| 50 | 31.7 | |

| 75 | 12.3 | |

| ≥85 | 6.7 | |

| Mean Charlson Comorbidity Index score for in-hospital CDI patients | 2.57 | Magee et al,102 2015 |

| QALYs lost owing to CDI-related mortality by age, No.h | ||

| 26 y | 48.11 (36.14-60.24) | NA |

| 49.5 y | 28.70 (22.04-36.73) | |

| 74.5 y | 12.00 (9.13-15.21) | |

| 85 y | 6.39 (4.98-8.30) | |

| Other | ||

| Time at lower utility owing to symptomatic diarrhea, d | 4.2 (3.15-5.25) | Sethi et al,132 2010; Bobulsky et al,133 2008 |

| Hospitalization utility value | 0.63 | Shaw et al,134 2005 |

| Proportion of modeled deaths among CDI patients attributable to CDI | 0.48 | Tabak et al,135 2013; Lessa et al,1 2015 |

| Proportion of patients with CDI readmitted within 30 d, % | 23.2 (20.0-30.1) | Magee et al,102 2015; Chopra et al,136 2015; AHRQ,137 2009 |

| Proportion of patients with no CDI readmitted within 30 d, % | 14.4 (13.9-14.8) | Magee et al,102 2015; Chopra et al,136 2015; AHRQ,138 2013; AHRQ,139 2014 |

Abbreviations: ABHR, alcohol-based hand rub; AHRQ, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; ASHES, American Society for Healthcare Environmental Services; BLS, Bureau of Labor Statistics; CDC, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CDI, Clostridioides difficile infection; IDPH, Illinois Department of Public Health; NA, not applicable; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; UV, ultraviolet.

Enhanced health care worker, patient, and visitor hand hygiene and health care worker and visitor contact precautions as well as all ideal-level campaigns.

For details regarding intervention specific staffing requirements, see the Cost subsection in Methods.

These data are based on BLS data; no range is available.

Category includes nonsporicidal quaternary ammonium solution, mops, and rags.

Category includes peracetic acid and/or hydrogen peroxide solution, mops, and rags.

Each patient transfer also requires an additional terminal cleaning per patient hospitalization.

Parameterizes time horizon.

Data in this section was based on calculations from Table 1.

Outcomes

The number of HO-CDIs per year was output directly from the model for each run.6 We defined HO-CDI based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidelines as symptomatic diarrhea plus a positive laboratory test result on a specimen collected more than 3 days after hospital admission.143 We calculated QALYs using model output and the utility values shown in Table 2. To determine the QALYs lost because of CDI-associated mortality, the age distribution for CDI cases was used in conjunction with age-specific utility values from healthy adults. Mean life expectancies were derived from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention life tables, accounting for a mean Charlson Comorbidity Index for in-hospital CDI patients of 2.57.102 The total number of deaths output from the model was multiplied by 0.48 to account for C difficile–associated mortality.1,135 Discounting future QALYs is controversial144; thus, they were not discounted in the primary analysis, similar to costs. Results of a supplemental analysis in which future QALYs were discounted at 3% is included in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

The minor loss in QALYs due to CDI symptoms was calculated from a mean symptomatic period of 4.2 days and utility value for symptomatic CDI of 0.81.132,133 Since there is no established utility measure of CDI in the United States, this followed a standard practice of basing it on that of noninfectious diarrhea.123,124,125,126,127 A loss in QALYs owing to time spent in a hospital admission was accounted for with a 0.63 utility value for hospitalized patients, derived using the EuroQol-5D instrument.134 Thus, it was possible to have a net negative QALY, despite a minimally net positive CDI averted.

Statistical Analysis

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) for HO-CDIs averted and QALYs gained were calculated using 2 methods. In the first approach, we found means for each intervention’s costs, HO-CDIs, and QALYs across all runs. We then calculated ICERs using these means for compared interventions. In the second method, an ICER was calculated based on the costs, HO-CDIs, and QALYs of 2 interventions for each run. These ICERs were then used to calculate the proportion of runs that met 21 willingness-to-pay thresholds. We assumed that any run resulting in negative incremental QALYs was not cost-effective. Analysis was conducted in R version 3.4.3 (R Project for Statistical Computing). No statistical testing was performed, so no prespecified level of significance was set.

A probabilistic sensitivity analysis was conducted varying cost and QALY parameter estimates simultaneously. Estimates were varied using the triangular distribution, with the minimum, mean, and maximum values reported in Table 2. Each single intervention and bundle simulation was run 100 000 times. One-way sensitivity analyses were also performed using the minimum and maximum reported values (Table 2).

Results

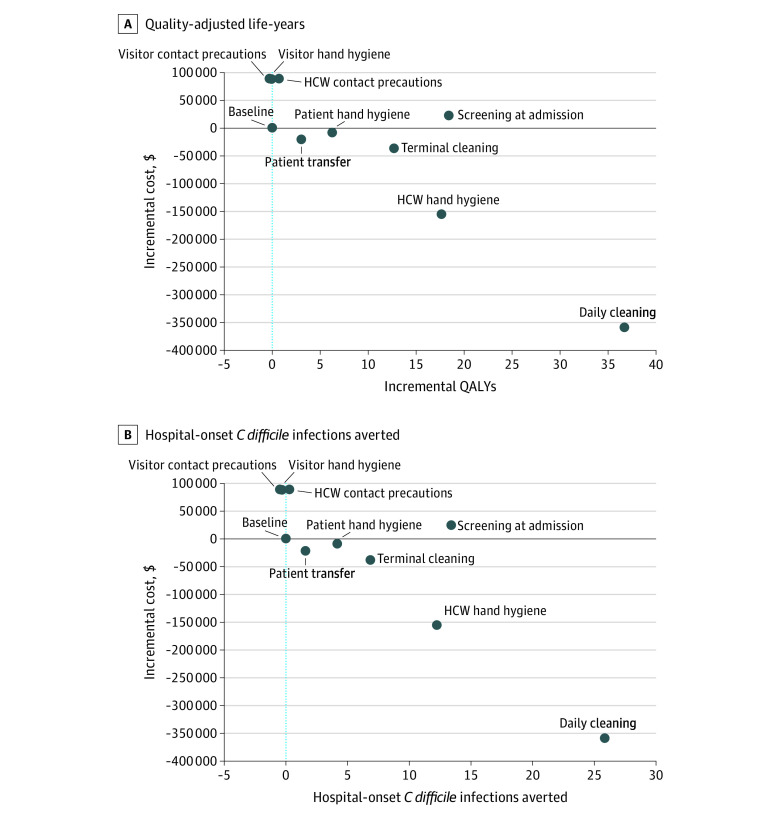

In this agent-based model of a simulated 200-bed tertiary, acute care, adult hospital, 5 of 9 enhanced-level interventions were dominant compared with baseline hospital practices, resulting in cost savings, increased QALYs, and averted infections, as follows: daily cleaning (the most cost-effective, saving $358 268, 25.9 infections, and 36.8 QALYs annually), terminal cleaning, health care worker hand hygiene, patient hand hygiene, and reduced patient transfers (Table 3 and Figure 1). The clinical consequences of these interventions ranged considerably, with daily cleaning preventing more than 16 times as many infections as the patient transfer intervention (25.9 vs 1.6). Screening at admission cost $1283 per QALY, while health care worker contact precautions and visitor hand hygiene interventions cost $123 264 and $5 730 987 per QALY, respectively. The visitor contact precautions intervention was dominated, with increased costs and decreased QALYs.

Table 3. Incremental Cost-effectiveness Ratios of Single and Bundled Intervention Strategies.

| Intervention strategy | Comparison | Mean incremental | Cost per HO-CDI averted, 2018 US $ | Cost per QALY, 2018 US $ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost, 2018 US $ | HO-CDI averted | QALY | ||||

| Enhanced-level single interventions | ||||||

| Enhanced daily cleaning | Baseline | –358 268 | 25.9 | 36.8 | Dominant | Dominant |

| Enhanced HCW CP | Baseline | 87 080 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 217 266 | 123 264 |

| Enhanced HCW HH | Baseline | –155 575 | 12.3 | 17.7 | Dominant | Dominant |

| Enhanced patient HH | Baseline | –8235 | 4.2 | 6.3 | Dominant | Dominant |

| Enhanced patient transfer | Baseline | –19 892 | 1.6 | 3.1 | Dominant | Dominant |

| Enhanced screening | Baseline | 23 763 | 13.4 | 18.5 | 1771 | 1283 |

| Enhanced terminal cleaning | Baseline | –38 039 | 6.9 | 12.8 | Dominant | Dominant |

| Enhanced visitor CP | Baseline | 88 863 | 0.1 | –0.2 | 982 995 | Dominated |

| Enhanced visitor HH | Baseline | 88 745 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3 697 712 | 5 730 987 |

| Ideal-level single interventions | ||||||

| Ideal daily cleaning | Enhanced daily cleaning | 38 707 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 24 071 | 18 399 |

| Ideal HCW CP | Enhanced HCW CP | 53 537 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 118 182 | 136 135 |

| Ideal HCW HH | Enhanced HCW HH | –66 808 | 7.1 | 9.9 | Dominant | Dominant |

| Ideal patient HH | Enhanced patient HH | –33 303 | 4.0 | 5.9 | Dominant | Dominant |

| Ideal patient transfer | Enhanced patient transfer | 7573 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 9772 | 6194 |

| Ideal screening | Enhanced screening | 56 150 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 158 080 | 100 084 |

| Ideal terminal cleaning | Enhanced terminal cleaning | 18 791 | 2.1 | 3.6 | 9093 | 5275 |

| Ideal visitor CP | Enhanced visitor CP | 55 896 | –0.2 | 0.03 | Dominated | 1 669 089 |

| Ideal visitor HH | Enhanced visitor HH | 55 304 | –0.1 | –0.01 | Dominated | Dominated |

| Intervention bundles | ||||||

| HH bundle, ie, patient and HCW HH | Baseline | –188 164 | 15.3 | 22.0 | Dominant | Dominant |

| HH bundle, ie, patient and HCW HH | HCW HH | –32 588 | 3.0 | 4.2 | Dominant | Dominant |

| Environmental cleaning bundle, ie, daily and terminal cleaning | Baseline | –253 982 | 26.1 | 37.4 | Dominant | Dominant |

| Environmental cleaning bundle, ie, daily and terminal cleaning | Daily cleaning | 104 285 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 494 712 | 170 469 |

| Patient-centered bundle, ie, screening, patient HH, patient transfer | Baseline | –35 594 | 19.9 | 28.3 | Dominant | Dominant |

| Daily cleaning, screening | Baseline | –172 979 | 30.9 | 43.0 | Dominant | Dominant |

| Daily cleaning, screening | Daily cleaning | 185 288 | 5.0 | 6.3 | 36 769 | 29 616 |

| Daily cleaning, screening, HCW HH | Daily cleaning, screening bundle | 79 998 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 74 293 | 50 196 |

| Daily cleaning, screening, HCW HH, patient HH | Daily cleaning, screening, HCW HH bundle | 56 836 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 214 315 | 146 792 |

| Daily cleaning, screening, HCW HH, patient HH, terminal cleaning | Daily cleaning, screening, HCW HH, patient HH bundle | 134 921 | 0.03 | 0.2 | 4 164 243 | 758 618 |

| Daily cleaning, screening, HCW HH, patient HH, terminal cleaning, patient transfer | Daily cleaning, screening, HCW HH, patient HH, terminal cleaning bundle | 17 761 | 0.04 | 0.1 | 422 885 | 221 009 |

Abbreviations: CP, contact precautions; HCW, health care worker; HH, hand hygiene; HO-CDI, hospital-onset Clostridioides difficile infection; QALY, quality-adjusted life year.

Figure 1. Incremental Cost vs Quality-Adjusted Life-Years (QALYs) and Hospital-Onset Clostridioides difficile Infections Averted for Enhanced Interventions, Compared With Baseline.

HCW indicates health care worker.

Improving from enhanced to ideal intervention levels offered only small clinical benefits for most interventions (Table 3). It was cost saving and most effective for ideal health care worker and patient hand hygiene, averting an additional 7.1 and 4.0 HO-CDIs a year, respectively, compared with enhanced interventions. The ideal level was cost-effective for daily cleaning ($18 399/QALY), terminal cleaning ($5275/QALY), and patient transfer ($6194/QALY) at a willingness-to-pay threshold of $50 000/QALY.

Cost-effectiveness of the bundle strategies varied based on a bundle’s intervention components (Table 3). Adding patient hand hygiene to the health care worker hand hygiene intervention was cost saving, saving a mean of $32 588 and 4.2 QALYs annually in the model 200-bed hospital compared with the health care worker hand hygiene intervention alone. When screening, health care worker hand hygiene, and patient hand hygiene interventions were sequentially added to daily cleaning to form 2-, 3-, and 4-pronged bundles, the ICERs for these additions were $29 616, $50 196, and $146 792 per QALY, respectively.

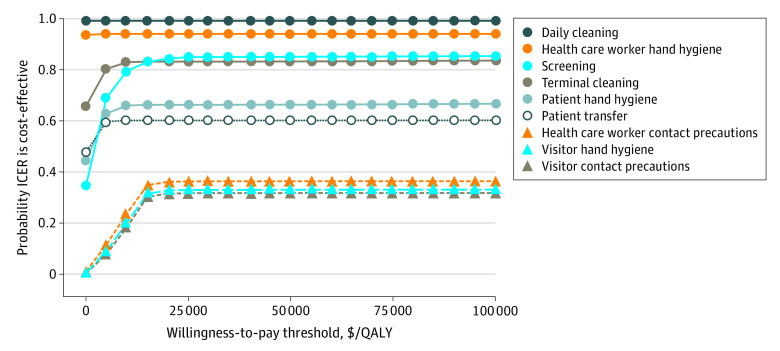

We also evaluated the percentage of times each intervention was cost-effective at 21 willingness-to-pay thresholds. These results are presented as an acceptability curve (Figure 2). Daily cleaning consistently had the greatest proportion of runs that were cost-effective, with 99% of runs cost-effective at a willingness-to-pay threshold of $5000 per QALY.

Figure 2. Acceptability Curve Based on 5000 Runs of Each Intervention at 21 Willingness-to-Pay Thresholds.

ICER indicates incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; and QALY, quality-adjusted life-year.

Detailed results of the 1-way sensitivity analyses and probabilistic sensitivity analysis are included in eFigure 2, eFigure 3, eFigure 4, and eTable 3 in the Supplement. The trends in comparative cost-effectiveness were stable across most variations in cost and utility parameters. The 5 cost-saving interventions were most sensitive to hospitalization costs (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Screening at admission was most sensitive to increased costs of polymerase chain reaction testing. Visitor hand hygiene and health care worker contact precautions were most sensitive to changes in age-related utility values (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). Most notably, in the probabilistic sensitivity analysis (eFigure 4 in the Supplement), the patient-centered intervention bundle (comprised of screening at admission, patient hand hygiene, and patient transfer) changed from cost-saving to a cost of $245/QALY, and the visitor hand hygiene intervention became dominated (compared with $5 730 987/QALY) (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Discussion

In this model-based economic evaluation, daily cleaning, health care worker hand hygiene, patient hand hygiene, terminal cleaning, and reduced patient transfers were all found to be cost saving. Daily cleaning was the most clinically effective and cost-effective intervention by far, saving $358 268, 25.9 infections, and 36.8 QALYs annually in the 200-bed model hospital. In comparison with the other existing C difficile simulation models, Brain et al9 found that a cleaning and hand hygiene bundle had the greatest increase in QALYs and was the most cost-saving of 9 bundle strategies. Nelson et al8 reported that increasing environmental cleaning within the context of multi-intervention bundles resulted in minimal gains in effectiveness. However, their bundle strategies included up to 6 interventions simultaneously and are not comparable with an isolated daily cleaning intervention. Similarly, a recent multicenter trial by Ray et al145 found that reduction of C difficile environmental cultures did not correlate with reduced infection rates. However, this study is also not comparable, given that it targeted sporicidal daily cleaning only in known CDI rooms and did not change practices for non-CDI patient rooms and hospital common rooms. Thus, it appears that blocking asymptomatic transmission by using sporicidal products hospitalwide may be essential to obtaining a reduction in HO-CDI rates.

Among all the interventions we modeled, health care worker hand hygiene is the most well studied and has been shown to be cost saving in several prior contexts. Chen et al146 reported that every dollar spent on their hospital’s 4-year hand hygiene program resulted in a $32.73 return on investment (2018 USD). Likewise, Pittet et al147 found that hand hygiene needed to account for less than 1% of the concurrent decline in hospital-associated infections at their institution to be cost saving. Our results are also in line with the prior modeling studies. Nelson et al8 reported that adding health care worker hand hygiene to existing bundles increased total QALYs with few additional costs, and health care worker hand hygiene was a key component of the most cost-saving cleaning and hygiene bundle in the study by Brain et al.9

C difficile screening has also recently been shown to be highly effective at reducing HO-CDI in real-world and modeling contexts.6,10,11,148,149 This intervention was highly cost-effective in our model, at a cost of $1283/QALY and is similar to the results of the study by Bartsch et al,124 in which screening cost less than $310/QALY (2018 USD).124 Both are likely conservative estimates because the cost-effectiveness of screening is expected to increase if the intervention is targeted to high-risk populations. In fact, when Saab et al149 modeled a C difficile screening and treatment intervention exclusively for patients with cirrhosis, costs were found to be 3.54 times lower than under baseline conditions.

The Veterans Affairs methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) screening bundle, instituted at Veterans Affairs hospitals nationwide in 2007, provides a precedent for large-scale screening implementation. It ultimately had a 96% participation rate and reduced MRSA by 45% among patients not in the intensive care unit patients and 62% among patients in the intensive care unit.90 The cost-effectiveness of this intervention was calculated at between $31 979 and $64 926 per life-year saved (2018 USD).97 Given the evidence from our study and others,124,149 we expect that screening for C difficile would be even more cost-effective than the Veteran Affairs MRSA initiative. However, additional work is needed to identify which populations to target before widespread implementation.

While screening is not yet standard practice, contact precautions are a mainstay of C difficile infection prevention programs.3 They are recommended by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America for both health care workers and visitors of patients with CDI.150,151 However, evidence for these guidelines is based primarily on studies of other pathogens and theoretical transmission concerns,108,152 given that C difficile–targeted studies are lacking. In our study, we found neither health care worker nor visitor contact precautions to be cost-effective. The enhanced-level health care worker contact precautions intervention cost $123 264 per QALY, with another $136 135 per QALY for the ideal-level implementation. The results were even worse for visitor contact precaution interventions, with the enhanced level being dominated and the ideal level costing $1 669 089 per QALY. Thus, it is likely that the screening intervention, which, as modeled, prompts the use of visitor and health care worker contact precautions for asymptomatic colonized patients, would be even more cost-effective if contact precautions were not used for asymptomatic patients who test positive.

Recognizing that all hospitals operate in an environment of constrained resources, support must be shifted from minimally effective, high-cost interventions, such as visitor contact precautions, to more innovative, cost-effective solutions. For example, patient hand hygiene, which is rarely incorporated into C difficile bundles,3 was 1 of only 2 interventions to be cost saving at both the enhanced and ideal level. It was also cost saving compared with health care worker hand hygiene alone. In fact, all 2-pronged intervention bundles investigated in this study were cost saving. However, incremental intervention cost-effectiveness decreased beyond 2-intervention bundles. Adding subsequent interventions to the 2-pronged daily cleaning and screening at admission bundle came at an ICER of $50 196/QALY for the third strategy, $146 792/QALY for the fourth strategy, and $758 618/QALY for the fifth strategy.

The recommendation to implement a smaller number of highly effective interventions runs contrary to the current infection control climate. A recent review of CDI bundles found that more than half of bundles include 6 or more components, with a minimum of 3 and maximum of 8 interventions.3 Given the lack of evidence and guidelines surrounding bundle composition, it is not surprising that institutions seek to maximize CDI reduction by implementing increasingly larger bundled strategies. However, our results provide evidence that continuing to increase bundles without accounting for the cost and effectiveness of individual components may be counterproductive, depending on institutional priorities and cost constraints. Instead, institutions should consider streamlining their infection control initiatives and may opt to focus on a smaller number of highly cost-effective interventions.

It is important to note that while many of the interventions in this study were cost saving, they are not without upfront costs. Even at the enhanced level, each intervention required the employment of additional infection control nursing staff. These individuals have the critical responsibility of coordinating implementation, assessing compliance, providing direct frontline feedback, and iteratively evaluating intervention effectiveness. Hospital administrative buy-in and financial support is key to both the initial implementation of an intervention and sustaining its long-term success.

Limitations

This study has limitations. The cost-effectiveness results presented in this study are inherently dependent on the quality of our agent-based model, which underwent rigorous verification and validation processes.6 It suffers from limitations of the original model, such as assuming transmission of a generic C difficile strain and the lack of an antibiotic stewardship intervention. Particularly relevant to this study, we did not stratify CDI by severity or include complications such as colitis or toxic megacolon. By evaluating all cases using a utility value that corresponds to mild to moderate CDI, we likely underestimate the true cost-effectiveness of these interventions.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this was the first C difficile cost-effectiveness analysis to compare standard infection control strategies and emerging patient-centered interventions. In a field that lacks specific guidance regarding the cost-effectiveness of interventions targeting C difficile, this study provides critical evidence regarding where to allocate limited resources for the greatest potential success. Daily sporicidal cleaning is among several promising, cost-saving strategies that should be prioritized over minimally effective, costly strategies, such as visitor contact precautions. Maintaining the status quo, focused on large, multipronged bundles with variable efficacy, will continue to shift limited resources away from more productive, cost-saving strategies that have greater potential to improve patient outcomes.

eAppendix. Agent-Based Simulation Model

eTable 1. Transmission Parameters Estimates

eTable 2. Discounted QALY Analysis

eTable 3. Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis Results of Incremental Cost-effectiveness Ratios for 100 000 Runs

eFigure 1. Schematic of the 200-Bed Model Hospital and Possible Agent Movement

eFigure 2. One-Way Sensitivity Analysis of Cost-Saving Interventions

eFigure 3. One-Way Sensitivity Analysis of Cost-effective Interventions

eFigure 4. Incremental Cost-effectiveness of 100 000 Runs of the Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis

eReferences.

References

- 1.Lessa FC, Mu Y, Bamberg WM, et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):825-834. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Hospital Acquired Condition (HAC) Reduction Program. Updated January 6, 2020. Accessed July 15, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/HAC/Hospital-Acquired-Conditions.html

- 3.Barker AK, Ngam C, Musuuza JS, Vaughn VM, Safdar N. Reducing Clostridium difficile in the inpatient setting: a systematic review of the adherence to and effectiveness of C. difficile prevention bundles. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(6):639-650. doi: 10.1017/ice.2017.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Redelings MD, Sorvillo F, Mascola L. Increase in Clostridium difficile–related mortality rates, United States, 1999-2004. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(9):1417-1419. doi: 10.3201/eid1309.061116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grigoras CA, Zervou FN, Zacharioudakis IM, Siettos CI, Mylonakis E. Isolation of C. difficile carriers alone and as part of a bundle approach for the prevention of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI): a mathematical model based on clinical study data. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker AK, Alagoz O, Safdar N. Interventions to reduce the incidence of hospital-onset clostridium difficile infection: an agent-based modeling approach to evaluate clinical effectiveness in adult acute care hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(8):1192-1203. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nanwa N, Kendzerska T, Krahn M, et al. The economic impact of Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(4):511-519. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson RE, Jones M, Leecaster M, et al. An economic analysis of strategies to control Clostridium difficile transmission and infection using an agent-based simulation model. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0152248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brain D, Yakob L, Barnett A, et al. Economic evaluation of interventions designed to reduce Clostridium difficile infection. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0190093. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Longtin Y, Paquet-Bolduc B, Gilca R, et al. Effect of detecting and isolating Clostridium difficile carriers at hospital admission on the incidence of C difficile infections: a quasi-experimental controlled study. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(6):796-804. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linsenmeyer K, O’Brien W, Brecher SM, et al. Clostridium difficile screening for colonization during an outbreak setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(12):1912-1914. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. ; CHEERS Task Force . Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. Value Health. 2013;16(2):e1-e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Hospital Association AHA Hospital Statistics, 2016. American Hospital Association; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Statistical brief #180: overview of hospital stays in the United States, 2012. Accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb180-Hospitalizations-United-States-2012.pdf [PubMed]

- 15.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Statistical brief #187: overview of hospital stays for children in the United States, 2012. Accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb187-Hospital-Stays-Children-2012.pdf [PubMed]

- 16.Kaboli PJ, Go JT, Hockenberry J, et al. Associations between reduced hospital length of stay and 30-day readmission rate and mortality: 14-year experience in 129 Veterans Affairs hospitals. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(12):837-845. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-12-201212180-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Number, rate, and average length of stay for discharges from short-stay hospitals, by age, region, and sex: United States, 2010. Accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhds/1general/2010gen1_agesexalos.pdf

- 18.Hicks LA, Bartoces MG, Roberts RM, et al. US outpatient antibiotic prescribing variation according to geography, patient population, and provider specialty in 2011. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(9):1308-1316. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frenk SM, Kit BK, Lukacs SL, Hicks LA, Gu Q. Trends in the use of prescription antibiotics: NHANES 1999-2012. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(1):251-256. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dantes R, Mu Y, Hicks LA, et al. Association between outpatient antibiotic prescribing practices and community-associated Clostridium difficile infection. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2(3):ofv113. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofv113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koo HL, Van JN, Zhao M, et al. Real-time polymerase chain reaction detection of asymptomatic Clostridium difficile colonization and rising C difficile-associated disease rates. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(6):667-673. doi: 10.1086/676433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alasmari F, Seiler SM, Hink T, Burnham C-AD, Dubberke ER. Prevalence and risk factors for asymptomatic Clostridium difficile carriage. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):216-222. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leekha S, Aronhalt KC, Sloan LM, Patel R, Orenstein R. Asymptomatic Clostridium difficile colonization in a tertiary care hospital: admission prevalence and risk factors. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(5):390-393. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loo VG, Bourgault A-M, Poirier L, et al. Host and pathogen factors for Clostridium difficile infection and colonization. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(18):1693-1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eyre DW, Griffiths D, Vaughan A, et al. Asymptomatic Clostridium difficile colonisation and onward transmission. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e78445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nissle K, Kopf D, Rösler A. Asymptomatic and yet C. difficile-toxin positive? prevalence and risk factors of carriers of toxigenic Clostridium difficile among geriatric in-patients. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):185. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0358-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kagan S, Wiener-Well Y, Ben-Chetrit E, et al. The risk for Clostridium difficile colitis during hospitalization in asymptomatic carriers. J Hosp Infect. 2017;95(4):442-443. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2017.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta S, Mehta V, Herring T, et al. A large prospective north american epidemiologic study of hospital-associated Clostridium difficile colonization and infection. Paper presented at: Fourth International Clostridium Difficile Symposium; September 22, 2012. Bled, Slovenia. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hung Y-P, Lin H-J, Wu T-C, et al. Risk factors of fecal toxigenic or non-toxigenic Clostridium difficile colonization: impact of Toll-like receptor polymorphisms and prior antibiotic exposure. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dubberke ER, Burnham C-AD. Diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection: treat the patient, not the test. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1801-1802. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) statistical briefs: Clostridium difficile infections (CDI) in hospital stays, 2009; statistical brief #124. Accessed February 19, 2019. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK92613/

- 32.Evans ME, Simbartl LA, Kralovic SM, Jain R, Roselle GA. Clostridium difficile infections in Veterans Health Administration acute care facilities. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(8):1037-1042. doi: 10.1086/677151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bettin K, Clabots C, Mathie P, Willard K, Gerding DN. Effectiveness of liquid soap vs. chlorhexidine gluconate for the removal of Clostridium difficile from bare hands and gloved hands. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1994;15(11):697-702. doi: 10.1086/646840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oughton MT, Loo VG, Dendukuri N, Fenn S, Libman MD. Hand hygiene with soap and water is superior to alcohol rub and antiseptic wipes for removal of Clostridium difficile. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30(10):939-944. doi: 10.1086/605322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edmonds SL, Zapka C, Kasper D, et al. Effectiveness of hand hygiene for removal of Clostridium difficile spores from hands. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(3):302-305. doi: 10.1086/669521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jabbar U, Leischner J, Kasper D, et al. Effectiveness of alcohol-based hand rubs for removal of Clostridium difficile spores from hands. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(6):565-570. doi: 10.1086/652772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dierssen-Sotos T, Brugos-Llamazares V, Robles-García M, et al. Evaluating the impact of a hand hygiene campaign on improving adherence. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(3):240-243. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Randle J, Firth J, Vaughan N. An observational study of hand hygiene compliance in paediatric wards. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(17-18):2586-2592. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04103.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monistrol O, Calbo E, Riera M, et al. Impact of a hand hygiene educational programme on hospital-acquired infections in medical wards. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(12):1212-1218. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03735.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tromp M, Huis A, de Guchteneire I, et al. The short-term and long-term effectiveness of a multidisciplinary hand hygiene improvement program. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40(8):732-736. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kowitt B, Jefferson J, Mermel LA. Factors associated with hand hygiene compliance at a tertiary care teaching hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(11):1146-1152. doi: 10.1086/673465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mestre G, Berbel C, Tortajada P, et al. “The 3/3 strategy”: a successful multifaceted hospital wide hand hygiene intervention based on WHO and continuous quality improvement methodology. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47200. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eldridge NE, Woods SS, Bonello RS, et al. Using the six sigma process to implement the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guideline for hand hygiene in 4 intensive care units. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(suppl 2):S35-S42. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0273-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zerr DM, Allpress AL, Heath J, Bornemann R, Bennett E. Decreasing hospital-associated rotavirus infection: a multidisciplinary hand hygiene campaign in a children’s hospital. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24(5):397-403. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000160944.14878.2b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mayer J, Mooney B, Gundlapalli A, et al. Dissemination and sustainability of a hospital-wide hand hygiene program emphasizing positive reinforcement. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(1):59-66. doi: 10.1086/657666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muto CA, Blank MK, Marsh JW, et al. Control of an outbreak of infection with the hypervirulent Clostridium difficile BI strain in a university hospital using a comprehensive “bundle” approach. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(10):1266-1273. doi: 10.1086/522654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grant AM, Hofmann DA. It’s not all about me: motivating hand hygiene among health care professionals by focusing on patients. Psychol Sci. 2011;22(12):1494-1499. doi: 10.1177/0956797611419172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grayson ML, Russo PL, Cruickshank M, et al. Outcomes from the first 2 years of the Australian National Hand Hygiene Initiative. Med J Aust. 2011;195(10):615-619. doi: 10.5694/mja11.10747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pittet D, Simon A, Hugonnet S, Pessoa-Silva CL, Sauvan V, Perneger TV. Hand hygiene among physicians: performance, beliefs, and perceptions. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):1-8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-1-200407060-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clock SA, Cohen B, Behta M, Ross B, Larson EL. Contact precautions for multidrug-resistant organisms: current recommendations and actual practice. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(2):105-111. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Birnbach DJ, Rosen LF, Fitzpatrick M, Arheart KL, Munoz-Price LS. An evaluation of hand hygiene in an intensive care unit: are visitors a potential vector for pathogens? J Infect Public Health. 2015;8(6):570-574. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2015.04.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Randle J, Arthur A, Vaughan N, Wharrad H, Windle R. An observational study of hand hygiene adherence following the introduction of an education intervention. J Infect Prev. 2014;15(4):142-147. doi: 10.1177/1757177414531057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Birnbach DJ, Nevo I, Barnes S, et al. Do hospital visitors wash their hands? assessing the use of alcohol-based hand sanitizer in a hospital lobby. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40(4):340-343. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caroe Aarestrup S, Moesgaard F, Schuldt-Jensen J Nudging hospital visitors' hand hygiene compliance. Published 2016. Accessed July 16, 2020. https://inudgeyou.com/en/nudging-hospital-visitors-hand-hygiene-compliance/

- 55.Nishimura S, Kagehira M, Kono F, Nishimura M, Taenaka N. Handwashing before entering the intensive care unit: what we learned from continuous video-camera surveillance. Am J Infect Control. 1999;27(4):367-369. doi: 10.1016/S0196-6553(99)70058-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Randle J, Arthur A, Vaughan N. Twenty-four-hour observational study of hospital hand hygiene compliance. J Hosp Infect. 2010;76(3):252-255. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davis CR. Infection-free surgery: how to improve hand-hygiene compliance and eradicate methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from surgical wards. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92(4):316-319. doi: 10.1308/003588410X12628812459931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Srigley JA, Furness CD, Gardam M. Measurement of patient hand hygiene in multiorgan transplant units using a novel technology: an observational study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(11):1336-1341. doi: 10.1086/678419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cheng VCC, Wu AKL, Cheung CHY, et al. Outbreak of human metapneumovirus infection in psychiatric inpatients: implications for directly observed use of alcohol hand rub in prevention of nosocomial outbreaks. J Hosp Infect. 2007;67(4):336-343. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hedin G, Blomkvist A, Janson M, Lindblom A. Occurrence of potentially pathogenic bacteria on the hands of hospital patients before and after the introduction of patient hand disinfection. APMIS. 2012;120(10):802-807. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2012.02912.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gagné D, Bédard G, Maziade PJ. Systematic patients’ hand disinfection: impact on meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection rates in a community hospital. J Hosp Infect. 2010;75(4):269-272. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stone PW, Hasan S, Quiros D, Larson EL. Effect of guideline implementation on costs of hand hygiene. Nurs Econ. 2007;25(5):279-284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Golan Y, Doron S, Griffith J, et al. The impact of gown-use requirement on hand hygiene compliance. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(3):370-376. doi: 10.1086/498906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morgan DJ, Pineles L, Shardell M, et al. The effect of contact precautions on healthcare worker activity in acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(1):69-73. doi: 10.1086/668775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Swoboda SM, Earsing K, Strauss K, Lane S, Lipsett PA. Isolation status and voice prompts improve hand hygiene. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(7):470-476. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2006.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Almaguer-Leyva M, Mendoza-Flores L, Medina-Torres AG, et al. Hand hygiene compliance in patients under contact precautions and in the general hospital population. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(11):976-978. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zellmer C, Blakney R, Van Hoof S, Safdar N. Impact of sink location on hand hygiene compliance for Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(4):387-389. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morgan DJ, Rogawski E, Thom KA, et al. Transfer of multidrug-resistant bacteria to healthcare workers’ gloves and gowns after patient contact increases with environmental contamination. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(4):1045-1051. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31823bc7c8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Landelle C, Verachten M, Legrand P, Girou E, Barbut F, Brun-Buisson C. Contamination of healthcare workers’ hands with Clostridium difficile spores after caring for patients with C. difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(1):10-15. doi: 10.1086/674396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tomas ME, Kundrapu S, Thota P, et al. Contamination of health care personnel during removal of personal protective equipment. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1904-1910. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Weber DJ, Sickbert-Bennett EE, Brown VM, et al. Compliance with isolation precautions at a university hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(3):358-361. doi: 10.1086/510871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Manian FA, Ponzillo JJ. Compliance with routine use of gowns by healthcare workers (HCWs) and non-HCW visitors on entry into the rooms of patients under contact precautions. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(3):337-340. doi: 10.1086/510811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bearman GML, Marra AR, Sessler CN, et al. A controlled trial of universal gloving versus contact precautions for preventing the transmission of multidrug-resistant organisms. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(10):650-655. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bearman G, Rosato AE, Duane TM, et al. Trial of universal gloving with emollient-impregnated gloves to promote skin health and prevent the transmission of multidrug-resistant organisms in a surgical intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(5):491-497. doi: 10.1086/651671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Deyneko A, Cordeiro F, Berlin L, Ben-David D, Perna S, Longtin Y. Impact of sink location on hand hygiene compliance after care of patients with Clostridium difficile infection: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:203. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1535-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sitzlar B, Deshpande A, Fertelli D, Kundrapu S, Sethi AK, Donskey CJ. An environmental disinfection odyssey: evaluation of sequential interventions to improve disinfection of Clostridium difficile isolation rooms. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(5):459-465. doi: 10.1086/670217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Goodman ER, Platt R, Bass R, Onderdonk AB, Yokoe DS, Huang SS. Impact of an environmental cleaning intervention on the presence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant Enterococci on surfaces in intensive care unit rooms. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(7):593-599. doi: 10.1086/588566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hayden MK, Bonten MJM, Blom DW, Lyle EA, van de Vijver DA, Weinstein RA. Reduction in acquisition of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus after enforcement of routine environmental cleaning measures. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(11):1552-1560. doi: 10.1086/503845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Boyce JM, Havill NL, Dumigan DG, Golebiewski M, Balogun O, Rizvani R. Monitoring the effectiveness of hospital cleaning practices by use of an adenosine triphosphate bioluminescence assay. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30(7):678-684. doi: 10.1086/598243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hess AS, Shardell M, Johnson JK, et al. A randomized controlled trial of enhanced cleaning to reduce contamination of healthcare worker gowns and gloves with multidrug-resistant bacteria. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(5):487-493. doi: 10.1086/670205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ramphal L, Suzuki S, McCracken IM, Addai A. Improving hospital staff compliance with environmental cleaning behavior. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2014;27(2):88-91. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2014.11929065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Anderson DJ, Chen LF, Weber DJ, et al. ; CDC Prevention Epicenters Program . Enhanced terminal room disinfection and acquisition and infection caused by multidrug-resistant organisms and Clostridium difficile (the Benefits of Enhanced Terminal Room Disinfection study): a cluster-randomised, multicentre, crossover study. Lancet. 2017;389(10071):805-814. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31588-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Clifford R, Sparks M, Hosford E, et al. Correlating cleaning thoroughness with effectiveness and briefly intervening to affect cleaning outcomes: how clean is cleaned? PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0155779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Carling PC, Parry MM, Rupp ME, Po JL, Dick B, Von Beheren S; Healthcare Environmental Hygiene Study Group . Improving cleaning of the environment surrounding patients in 36 acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(11):1035-1041. doi: 10.1086/591940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nerandzic MM, Donskey CJ. A quaternary ammonium disinfectant containing germinants reduces Clostridium difficile spores on surfaces by inducing susceptibility to environmental stressors. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(4):ofw196. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wullt M, Odenholt I, Walder M. Activity of three disinfectants and acidified nitrite against Clostridium difficile spores. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24(10):765-768. doi: 10.1086/502129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Perez J, Springthorpe VS, Sattar SA. Activity of selected oxidizing microbicides against the spores of Clostridium difficile: relevance to environmental control. Am J Infect Control. 2005;33(6):320-325. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2005.04.240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Deshpande A, Mana TSC, Cadnum JL, et al. Evaluation of a sporicidal peracetic acid/hydrogen peroxide-based daily disinfectant cleaner. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(11):1414-1416. doi: 10.1086/678416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Block C. The effect of Perasafe and sodium dichloroisocyanurate (NaDCC) against spores of Clostridium difficile and Bacillus atrophaeus on stainless steel and polyvinyl chloride surfaces. J Hosp Infect. 2004;57(2):144-148. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jain R, Kralovic SM, Evans ME, et al. Veterans Affairs initiative to prevent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(15):1419-1430. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Harbarth S, Fankhauser C, Schrenzel J, et al. Universal screening for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at hospital admission and nosocomial infection in surgical patients. JAMA. 2008;299(10):1149-1157. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Deshpande A, Pasupuleti V, Rolston DDK, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of real-time polymerase chain reaction in detection of Clostridium difficile in the stool samples of patients with suspected Clostridium difficile infection: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(7):e81-e90. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bagdasarian N, Rao K, Malani PN. Diagnosis and treatment of Clostridium difficile in adults: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015;313(4):398-408. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.17103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.O’Horo JC, Jones A, Sternke M, Harper C, Safdar N. Molecular techniques for diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(7):643-651. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.02.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wilensky UN; Center for Connected Learning and Computer-Based Modeling NetLogo. Accessed July 15, 2020. http://ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo/

- 96.Stout NK, Goldie SJ. Keeping the noise down: common random numbers for disease simulation modeling. Health Care Manag Sci. 2008;11(4):399-406. doi: 10.1007/s10729-008-9067-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nelson RE, Stevens VW, Khader K, et al. Economic analysis of Veterans Affairs initiative to prevent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(5)(suppl 1):S58-S65. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nyman JA, Lees CH, Bockstedt LA, et al. Cost of screening intensive care unit patients for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in hospitals. Am J Infect Control. 2011;39(1):27-34. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2010.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational employment statistics. Published May 2019. Accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_stru.htm

- 100.Zimlichman E, Henderson D, Tamir O, et al. Health care-associated infections: a meta-analysis of costs and financial impact on the US health care system. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(22):2039-2046. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Final report: estimating the additional hospital inpatient cost and mortality associated with selected hospital-acquired conditions. Published November 2017. Accessed April 10, 2019. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications2/files/hac-cost-report2017.pdf

- 102.Magee G, Strauss ME, Thomas SM, Brown H, Baumer D, Broderick KC. Impact of Clostridium difficile–associated diarrhea on acute care length of stay, hospital costs, and readmission: a multicenter retrospective study of inpatients, 2009-2011. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(11):1148-1153. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cimiotti JP, Stone PW, Larson EL. A cost comparison of hand hygiene regimens. Nurs Econ. 2004;22(4):196-199, 204, 175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Larson EL, Aiello AE, Bastyr J, et al. Assessment of two hand hygiene regimens for intensive care unit personnel. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(5):944-951. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200105000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Voss A, Widmer AF. No time for handwashing!? handwashing versus alcoholic rub: can we afford 100% compliance? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1997;18(3):205-208. doi: 10.2307/30141985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Girou E, Loyeau S, Legrand P, Oppein F, Brun-Buisson C. Efficacy of handrubbing with alcohol based solution versus standard handwashing with antiseptic soap: randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2002;325(7360):362. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7360.362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Boyce JM. Antiseptic technology: access, affordability, and acceptance. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7(2):231-233. doi: 10.3201/eid0702.010216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Puzniak LA, Gillespie KN, Leet T, Kollef M, Mundy LM. A cost-benefit analysis of gown use in controlling vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus transmission: is it worth the price? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25(5):418-424. doi: 10.1086/502416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Papia G, Louie M, Tralla A, Johnson C, Collins V, Simor AE. Screening high-risk patients for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus on admission to the hospital: is it cost effective? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20(7):473-477. doi: 10.1086/501655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Glogerm Supplies Accessed October 29, 2018. http://www.glogerm.com

- 111.Glitterbug Supplies Accessed October 29, 2018. https://www.brevis.com/glitterbug/supplies

- 112.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Options for Evaluating Environmental Cleaning. Published December 2010. Accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/toolkits/evaluating-environmental-cleaning.html

- 113.Saha A, Botha SL, Weaving P, Satta G. A pilot study to assess the effectiveness and cost of routine universal use of peracetic acid sporicidal wipes in a real clinical environment. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44(11):1247-1251. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.03.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Doan L, Forrest H, Fakis A, Craig J, Claxton L, Khare M. Clinical and cost effectiveness of eight disinfection methods for terminal disinfection of hospital isolation rooms contaminated with Clostridium difficile 027. J Hosp Infect. 2012;82(2):114-121. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2012.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.American Society for Healthcare Environmental Services Practice Guidance for Healthcare Environmental Cleaning. American Hospital Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Curry SR, Schlackman JL, Hamilton TM, et al. Perirectal swab surveillance for Clostridium difficile by use of selective broth preamplification and real-time PCR detection of tcdB. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(11):3788-3793. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00679-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Schroeder LF, Robilotti E, Peterson LR, Banaei N, Dowdy DW. Economic evaluation of laboratory testing strategies for hospital-associated Clostridium difficile infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(2):489-496. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02777-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hendrich AL, Lee N. Intra-unit patient transports: time, motion, and cost impact on hospital efficiency. Nurs Econ. 2005;23(4):157-164, 147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Catchpole KR, de Leval MR, McEwan A, et al. Patient handover from surgery to intensive care: using Formula 1 pit-stop and aviation models to improve safety and quality. Paediatr Anaesth. 2007;17(5):470-478. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2006.02239.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Rayo MF, Mount-Campbell AF, O’Brien JM, et al. Interactive questioning in critical care during handovers: a transcript analysis of communication behaviours by physicians, nurses and nurse practitioners. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(6):483-489. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gold MR, Franks P, McCoy KI, Fryback DG. Toward consistency in cost-utility analyses: using national measures to create condition-specific values. Med Care. 1998;36(6):778-792. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199806000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Swinburn AT, Davis MM. Health status-adjusted life expectancy and health care spending for different age groups in the United States. Mich J Public Aff. 2013;10:30-43. Accessed July 16, 2020. http://sites.fordschool.umich.edu/mjpa/files/2014/08/2013-DavisSwinburn-LifeExpectancy.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ramsey S, Veenstra D, Clarke L, Gandhi S, Hirsch M, Penson D. Is combined androgen blockade with bicalutamide cost-effective compared with combined androgen blockade with flutamide? Urology. 2005;66(4):835-839. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Bartsch SM, Curry SR, Harrison LH, Lee BY. The potential economic value of screening hospital admissions for Clostridium difficile. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31(11):3163-3171. doi: 10.1007/s10096-012-1681-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Konijeti GG, Sauk J, Shrime MG, Gupta M, Ananthakrishnan AN. Cost-effectiveness of competing strategies for management of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a decision analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(11):1507-1514. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Tsai HH, Punekar YS, Morris J, Fortun P. A model of the long-term cost effectiveness of scheduled maintenance treatment with infliximab for moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28(10):1230-1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03839.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Thuresson P-O, Heeg B, Lescrauwaet B, Sennfält K, Alaeus A, Neubauer A. Cost-effectiveness of atazanavir/ritonavir compared with lopinavir/ritonavir in treatment-naïve human immunodeficiency virus-1 patients in Sweden. Scand J Infect Dis. 2011;43(4):304-312. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2010.545835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical briefs: costs for hospital stays in the united states, 2010; statistical brief #146. Accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK121966/

- 129.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Statistical brief #50: Clostridium difficile-associated disease in US hospitals, 1993-2005. Accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb50.pdf [PubMed]

- 130.Illinois Department of Public Health Trends in Clostridium difficile in Illinois based on hospital discharge data, 1999-2015. Published November 2016. Accessed May 10, 2019. http://www.healthcarereportcard.illinois.gov/ files/pdf/cdiff_2015_Trends_1.pdf

- 131.National Vital Statistics Reports. United States Life Tables, 2014. Accessed April 10, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr66/nvsr66_04.pdf [PubMed]

- 132.Sethi AK, Al-Nassir WN, Nerandzic MM, Bobulsky GS, Donskey CJ. Persistence of skin contamination and environmental shedding of Clostridium difficile during and after treatment of C. difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(1):21-27. doi: 10.1086/649016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Bobulsky GS, Al-Nassir WN, Riggs MM, Sethi AK, Donskey CJ. Clostridium difficile skin contamination in patients with C. difficile–associated disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(3):447-450. doi: 10.1086/525267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Shaw JW, Johnson JA, Coons SJ. US valuation of the EQ-5D health states: development and testing of the D1 valuation model. Med Care. 2005;43(3):203-220. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200503000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Tabak YP, Zilberberg MD, Johannes RS, Sun X, McDonald LC. Attributable burden of hospital-onset Clostridium difficile infection: a propensity score matching study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(6):588-596. doi: 10.1086/670621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Chopra T, Neelakanta A, Dombecki C, et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection on hospital readmissions and its potential impact under the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(4):314-317. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Statistical brief #145: readmissions following hospitalizations with Clostridium difficile infections, 2009. Accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb145.jsp [PubMed]

- 138.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2013. Annual progress report to Congress: national strategy for quality improvement in health care. Accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.ahrq.gov/working forquality/reports/2013-annual-report.html

- 139.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Statistical brief #230: a comparison of all-cause 7-day and 30-day readmissions, 2014. Accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/ statbriefs/sb230-7-Day-Versus-30-Day-Readmissions.jsp [PubMed]