Abstract

Objective

We aimed to determine how often patients who choose voluntary stopping of eating and drinking (VSED) are accompanied by Swiss family physicians, how physicians classify this process, and physicians’ attitudes and professional stance toward VSED.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study between August 2017 and July 2018 among 751 practicing family physicians in Switzerland (response rate 74%; 70.7% men; average age 58 (±9) years). We used a standardized evidence-based questionnaire for the survey.

Results

VSED is well-known among family physicians (81.9%), and more than one-third (42.8%) had accompanied at least one patient during VSED. In 2017, 1.1% of all deaths that occurred in Swiss nursing homes or in a private home were owing to VSED. This phenomenon was classified as a natural dying process (59.3%), passive euthanasia (32.0%), or suicide (5.3%).

Conclusions

Although about one in three Swiss family physicians have accompanied a person during VSED, family physicians lack sufficient in-depth knowledge to address patients and their relatives in an appropriate manner during the process. Further training and development of practice recommendations are needed to achieve more standardized accompaniment of VSED.

International Registered Report Identifier: DERR1-10.2196/10358

Keywords: General practitioner, food refusal, end-of-life decision making, outpatient care, voluntary stopping of eating and drinking, advance care planning, self-determination, end-of-life practice

Introduction

Decisions on health matters are strongly influenced by the autonomy and self-determination of the person concerned. Healthcare professionals encourage and require decisions from their patients; however, patients are increasingly interested in making their own decisions.1 Yet healthcare decisions do not refer exclusively to therapies and measures. Patients, especially those receiving end-of-life care, also entrust healthcare professionals with their wishes regarding their own death and they want to be supported in this.2

Besides assisted suicide, which is legal or prohibited depending on legal regulations, another option to end one’s life prematurely is by voluntary stopping of eating and drinking (VSED), which has become the recent focus of end-of-life practices.3–8 VSED is the act of a person who consciously refuses to eat or drink with the intention of dying.9 Healthcare professionals are therefore not charged with providing a lethal drug to the patient but rather with caring for and accompanying the patient from the beginning of VSED until her or his death.10 It is a phenomenon that is increasingly being researched internationally.4,7,8,11 In published studies, one- to two-thirds of participating healthcare professionals have accompanied at least one person during VSED.3–8 The occurrence of deaths attributable to VSED in Europe is between 0.4% to 2.1%, and a high number of unreported cases can be expected.4,7,8,11

The Swiss are very open and have conversations about the desire to die; Swiss people attach great importance to making self-determined end-of-life decisions.12 Alongside the already keen interest in legal assisted suicide in Switzerland, as evidenced by the growing membership in ‘euthanasia organisations’,13 there is also a growing public interest in VSED. This is particularly evident in public discussions in newspapers, television reports, and lectures delivered by healthcare professionals.14–17 This also means that healthcare professionals are increasingly confronted with their patients’ desire to die,12 and the likelihood of being confronted with a patient’s wish to die by VSED is increasing. The Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences has responded to this public interest and included an option for VSED in the ‘Management of Death and Dying’ Guideline in 2018.18 This guideline is intended to provide healthcare professionals with recommendations regarding the challenges that arise when providing end-of-life care and how to deal with them effectively. Less guidance is given regarding VSED; however, this option has been included as a controversial option. According to current knowledge, VSED typically occurs at home (52%) or in a nursing home (42%).3,19 In both cases, medical care in Switzerland is provided by family physicians, which is why we targeted this group in the current study.

The decision to embrace VSED is made by a person capable of judgement regarding the intention to die prematurely.5,9,20,21 VSED must be clearly distinguished from artificial feeding,22 from external influences that impair food intake (e.g., pain, malnutrition ),23–25 and from psychological impairments (e.g., dementia, depression).26,27 People choosing VSED are mostly women (62%) and can be found in all age groups; however, most individuals who opt for VSED (48%–70%) are aged 80 years or older.3,7,19,28

Because many people have an intimate relationship with their family physician, these professionals are often involved in the decision-making process regarding VSED.3,4 This is particularly important because as VSED progresses, the patient is dependent on the support of third parties owing to increasing physical weakness.29 A study among German palliative and family physicians showed that regardless of their health condition, these healthcare professionals give patients the right to receive medical care during VSED. In addition, they are also willing to accompany a person during VSED, although this willingness is considerably higher for patients with an oncological disease than for older people without serious illness.4 If family physicians are involved in the course of VSED from the outset, appropriate preparations can be made, including the involvement of outpatient or inpatient care staff, pastors, volunteers, and others. The inclusion of medical and nursing care becomes increasingly important as the person develops further dependence on such care.29,30

Family physicians can currently use a Dutch guideline31 to determine the necessary steps in preparation for and during VSED accompaniment, and they can receive valuable information in discussions with patients and relatives. Importantly, it is essential to determine the mental fitness of a person wishing to die before agreeing to accompany the individual in VSED.32–35 Furthermore, physiological changes in the body during this process must be considered, as should its duration and that side effects such as delirium can occur under certain circumstances.31,36–38

Considering the above, we described the occurrence of VSED accompaniment by Swiss family physicians and assessed how they classify the VSED process and physicians’ attitudes and professional stance concerning VSED.

Methods

Study design and setting

We used a cross-sectional study design. According to our study protocol,39 practicing family physicians providing primary medical care to the Swiss population were randomly selected and invited to participate in the study, conducted between August 2017 and July 2018. A response rate of 20% was targeted throughout Switzerland. Owing to cultural and linguistic differences within Switzerland, where German, French, and Italian are spoken, a response rate of 20% per major region was also targeted. There are seven major regions in Switzerland, consisting of one or more cantons with an average population density of 1,041,144.40

The initial questionnaire was Internet-based and designed using the survey software Questback (EFS 10.9). Swiss family physicians are well organised through the Confederation of the Swiss Medical Association ‘Médecins de famille et de l’efance Suisse’ (MFE; https://www.medecinsdefamille.ch/qui-sommes-nous/lassociation);41 therefore, we contacted physicians by post via the MFE, in their respective national language. The mailing contained a cover letter with a link to the questionnaire and a flyer with a description of the project. Reminders were sent by mail via the MFE 3 and 6 weeks later.

Five months after recruitment had begun, the response rate was 2.8%. We assumed that the low response rate was owing less to a lack of interest than to unsuitability of the recruitment strategy, i.e., using an online survey for this target group. This could not have been predicted in advance; therefore, we deviated from the online survey described in our study protocol and distributed a paper-and-pencil questionnaire instead. In February 2018, family physicians were invited to participate by post. Mailings contained a cover letter with information about the change in the survey strategy, the questionnaire, a description of the research project, an informed consent form, and a stamped return envelope. Completed questionnaires were scanned and read into EvaSys (Electric Paper (Schweiz), Lachen, Switzerland). The system automatically captures the responses; for unclear responses (e.g., corrected answers and free-text fields), the system reports an error message. All error messages were checked by one author (S. S.) and corrected manually. Free-text fields that were completed in French or Italian were translated into German by the first author (S. S.). Ambiguities were resolved by native speakers from the healthcare field. After the data collection was completed, an SPSS file was exported from EvaSys.

Participants

Practicing family physicians who were either specialized in general internal medicine or had completed further training to become a practical doctor (similar to a general practitioner) were included. Deceased or retired family physicians were excluded, as were those who exclusively care for children and adolescents and those who were unreachable.

Ethics approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the appropriate institutional review board of the Greater Region of Eastern Switzerland (EKOS 17/083; May 2017). Participation in the study was voluntary, and irreversible anonymity was guaranteed.

Variables

We used a previously developed and validated standardized questionnaire42 to calculate the occurrence of VSED accompaniment as well as attitudes, experiences, and the professional stance of family physicians toward VSED. First, participants were asked about their experiences with VSED. Participants were asked whether they had previously accompanied a person during VSED, to determine the occurrence of VSED accompaniment. Physicians who responded affirmatively were asked how often they had accompanied patients during VSED in their professional careers as well as during the past year. Respondents’ attitudes were measured using items related to personality, e.g., the compatibility of VSED with their worldview or religion. Professional stance was queried using items directly related to respondents’ professional actions, such as whether they would accompany a person during VSED and how they would classify VSED.

Data sources and measurement

The occurrence of VSED was calculated for two situations in 2017. First, the occurrence was calculated among all deaths (total 66,971) throughout Switzerland in 2017.43 Second, we calculated the occurrence among all deaths occurring in a nursing home or at home; in Switzerland, family physicians are responsible for both groups of patients. Of a total 40,183 deaths in 2017, 40% occurred in nursing homes and 20% occurred at home.44

Bias

There is no central platform where all practicing family physicians in Switzerland are listed, nor is everyone listed on the Internet. We used a professional association (MFE) to contact all family physicians in Switzerland. VSED was defined at the beginning of the questionnaire to ensure it was not confused with other forms of food refusal, such as anorexia.

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). To describe participants, the occurrence of VSED, and the attitudes and professional stance of family physicians, appropriate statistical methods were used such as mean and standard deviation, and frequency and percentage.

Subsequently, we performed logistic regression analyses using the following factors: age (years), sex (female, male), professional experience (years), VSED experience (yes, no), and VSED classification (not suicide [e.g., natural death, passive euthanasia, self-determination, alternative, and depends on the case], suicide). For multiple regression analyses, a 5-point Likert scale of agreement was dichotomised into 0 = disagree (neutral, disagree somewhat, and strongly disagree) and 1 = agree (strongly agree and agree somewhat).

Adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated as the effect measure. To evaluate model quality, we used Nagelkerke R square (R2). Significance was set at α = .05. Missing values were coded as such and automatically excluded from the analysis. The number of missing values in the analyses was indicated by the number of included values.

Role of the funding source

This research was funded by ‘Research in Palliative Care’ of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences, supported by the Stanley Thomas Johnson Foundation and the Gottfried and Julia Bangerter-Rhyner Foundation. The authors had complete control over the design, conduct, analysis, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

Description of participants

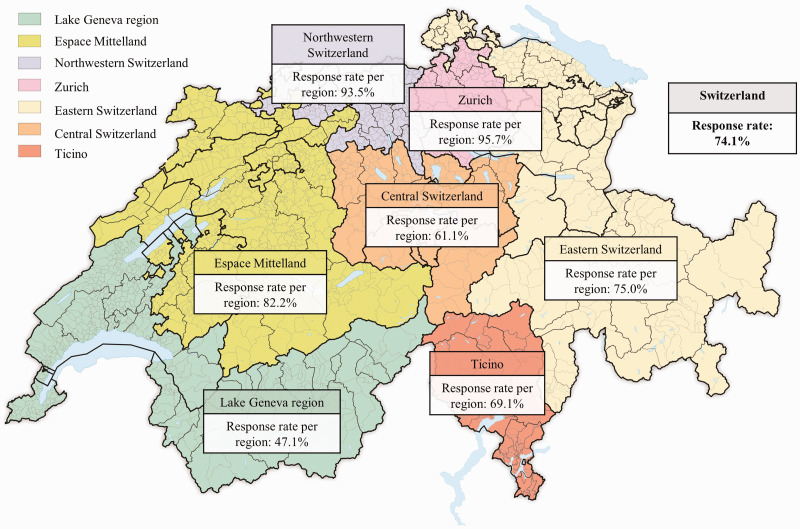

Of all 1,411 respondents, 1,013 were suitable for study participation. Respondents (n = 398) were excluded because of: recent death (n = 11), retirement (n = 86), exclusive care of children and young people (n = 67), and inaccessibility (n = 234). A total of 751 participants throughout Switzerland completed the questionnaire (response rate = 74%). As shown in Figure 1, the response rate in the seven major regions of the country ranged between 47% and 96%. Participants’ demographics are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Response rate of family physicians in the seven regions of Switzerland.

Source: Map of Tschubby45 with information on family physicians, provided by the authors.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics.

| N | 751 |

|---|---|

| Age (15 missing) | |

| - Mean (SD) (range) | 58 (9) (31–86) |

| - 30–39 years | 23 (3.1%) |

| - 40–49 years | 126 (17.1%) |

| - 50–59 years | 224 (30.4%) |

| - ≥60 years | 363 (49.3%) |

| Sex (15 missing) | |

| - Male | 520 (70.7%) |

| - Female | 216 (29.3%) |

| Medical specialty (0 missing) | |

| - General internal medicine | 743 (98.9%) |

| - Practical doctor | 8 (1.1%) |

| In addition to the physician’s practice, also work in (0 missing) | |

| - Hospital | 37 (4.9%) |

| - Hospice | 8 (1.1%) |

| - Nursing home | 122 (16.2%) |

| Work experience (10 missing) | |

| - Mean (SD) (range) | 29 (10) (1–58) |

| - <10 years | 15 (2.0%) |

| - 10–19 years | 125 (16.9%) |

| - 20–29 years | 216 (29.1%) |

| - 30–39 years | 282 (38.1%) |

| - 40–49 years | 99 (13.4%) |

| - 50–58 years | 4 (0.5%) |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation, VSED, voluntary stopping of eating and drinking.

Relevance, knowledge, experiences, occurrence, and recommendations regarding VSED by family physicians

We were interested in assessing the relevance of VSED in the everyday professional life of family physicians. On two scales (first scale: not relevant, less relevant, relevant, and very relevant; second scale: the relevance of VSED will not increase, will only increase a little, will increase, and will increase considerably), most participants rated VSED in their daily work as a topic of little or no relevance (64%, n = 462), which will not increase or will only increase slightly in the future (58%, n = 385).

Participants (n = 747, missing = 4) were asked to indicate (scale: no, yes) whether they were aware of VSED, whether they felt familiar with the topic, and whether they had already accompanied a patient during VSED. VSED was known by 82% of respondents (n = 612) as a way to end life prematurely. Only about half of physicians (49%, n = 362) felt that they were familiar with the topic, and 43% (n = 320) reported that they had already accompanied at least one person during VSED.

Participants with experience of VSED (n = 320) were asked further questions, to calculate the occurrence of VSED; a total of 302 responded. During their professional careers, participants had accompanied an average of 11 patients (N = 3,173, SD = 18, range = 1–100). In 2017, an average of two patients per respondent had been accompanied during VSED (N = 458, SD = 2, range = 0–30). In relation to all deaths that occurred at home or in nursing homes, the occurrence of VSED in 2017 was 1.1% (or 0.7% across all deaths).43,44

On average, in 2017, respondents recommended VSED as an end-of-life option to one patient (N = 397, SD = 2, range = 0–15). Of the 171 physicians who did not make this recommendation, 78 (46%) were against recommending VSED to anyone.

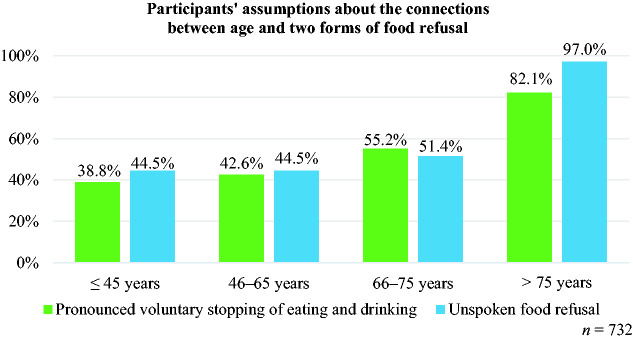

Family physicians’ classification of VSED

When asked how respondents would classify VSED (n = 735, missing = 16), more than half (59%) stated that VSED is a natural death process when overseen by a healthcare professional. One-third of respondents felt that VSED is equivalent to passive euthanasia (32.0%; see Figure 2). Among the remaining respondents, VSED was regarded as suicide (5%), a self-determined decision at the end of life (2%), and an alternative form of dying (1%). One percent of physicians said they would classify VSED differently depending on the case, which would also be based on the patients’ motives and physical health.

Figure 2.

Classification of voluntary stopping of eating and drinking by family physicians.

Factors that influenced physician VSED accompaniment

In general, more than two-thirds (73%) of respondents stated that VSED is compatible with their worldview and religion (see Table 2). The VSED experience increased the compatibility of VSED with one’s own worldview among 50% of experienced respondents (95% CI: 0.297–0.869, p = .013) and among 75% of those who classified VSED as suicide (95% CI: 0.117–0.518, p < .001, R2 = 0.06).

Table 2.

Family physicians´ attitudes and professional stance toward voluntary stopping of eating and drinking.

| Attitudes (A) and stance (S) toward voluntary stopping of eating and drinking (VSED) | Strongly disagree | Disagree somewhat | Neutral | Agree somewhat | Strongly agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

In general, regarding VSED |

Coding Mean (SD) |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| (A) Compatible with world view or religion | n = 7484.5 (0.9) | 202.7% | 162.1% | 567.5% | 11215.0% | 54472.7% |

| (S) Contradicts professional ethics | n = 7392.5 (1.4) | 24332.9% | 18824.8% | 13418.1% | 9813.3% | 8111.0% |

| (S) Determination of the patient's ability to judge is important | n = 7354.2 (1.1) | 141.9% | 628.4% | 9713.2% | 14019.0% | 42257.4% |

| (S) Entitled to medical and nursing care | n = 7454.9 (0.4) | 10.1% | 20.3% | 141.9% | 638.5% | 66589.3% |

| (S) Accept decision | n = 7494.7 (0.6) | 30.4% | 91.2% | 324.3% | 11014.7% | 59579.4% |

| (S) Respect decision | n = 7474.8 (0.5) | 20.3% | 50.7% | 121.6% | 9312.4% | 63585.0% |

| No | Yes | – | – | – | ||

| (A) Option for yourself | n = 7321.8 (0.4) | 17523.9% | 55776.1% | – | – | – |

| (S) Recommend VSED | n = 7251.6 (0.5) | 30241.7% | 42358.3% | – | – | – |

| (S) Ready to care for a patient during VSED | n = 7351.9 (0.3) | 628.4% | 67391.6% | – | – | – |

|

During VSED support |

|

Strongly disagree |

Somewhat disagree |

Neutral |

Somewhat agree |

Strongly agree |

| (A) Have moral doubts | n = 7452.4 (1.3) | 25334.0% | 20327.2% | 12917.3% | 7910.6% | 8110.9% |

| (A) A dignified manner of dying | n = 7444.1 (1.0) | 152.0% | 354.7% | 13518.1% | 24733.2% | 31241.9% |

| (S) Professionals are burdened | n = 7343.5 (1.1) | 344.6% | 10113.8% | 22030.0% | 23031.3% | 14920.3% |

| (S) Relatives are burdened | n = 735 4.2 (0.9) | 6 0.8% | 141.9% | 14319.5% | 27537.4% | 29740.4% |

| (S) Relatives have trouble accepting the decision | n = 7263.7 (0.9) | 91.2% | 537.3% | 23432.2% | 26636.6% | 16422.6% |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation, VSED, voluntary stopping of eating and drinking.

Regarding their professional position, 24% of respondents stated that VSED contradicts their ethics, 18% held a neutral stance, and 58% stated that VSED coincided with their ethical values. In total, 76% of physicians agreed that assessment of the patients’ ability to judge was necessary. Nearly all respondents believed that patients have a right to medical and nursing care (98%) and stated that they would respect the patient’s decision to choose VSED (97%); however, slightly fewer (94%) stated that they would accept the patient’s’ decision. The likelihood of accepting the patient’s decision regarding VSED was increased by 78% among physicians with experience of VSED (95% CI: 0.082–0.577, p = .002) and by 69% among physicians who classified VSED as suicide (95% CI: 0.108–0.872, p = .027, R2 = 0.09).

When asked whether participants would consider VSED as an option for themselves, most (76%) answered affirmatively. This likelihood increased by 70% among physicians who had accompanied a patient during VSED (95% CI: 0.194–0.452, p < .001) and by 75% among those who considered VSED to be suicide (95% CI: 0.123–0.494, p < .001, R2 = 0.12). Nearly all respondents (92%) said they felt ready to accompany a patient during VSED; the probability of accompanying a patient was increased by 75% among respondents with VSED experience (95% CI: 0.119–0.535, p < .001) and by 80% by those who classified VSED as suicide (95% CI: 0.089–0.442, p < .001, R2 = 0.13).

Only a little more than half of participants (58%) stated that they would recommend VSED to a patient who inquired about life-shortening measures. The probability of recommending VSED to a patient decreased by 3% with increased physician age (95% CI: 1.009–1.051, p = .004), increased by 49% among physicians with VSED experience (95% CI: 0.371–0.716, p < .001), and increased by 55% among those who classified VSED as suicide (95% CI: 0.229–0.892, p < .022, R2 = 0.08).

Attitudes during VSED accompaniment

Concerning VSED accompaniment, 22% of physicians stated that they had moral concerns whereas most (61%) had no moral concerns. In logistic regression analysis, no significant difference in moral concerns was identified. Most physicians (75%) considered VSED a dignified way to die; the probability of considering this form of death dignified increased by 52% after accompanying a patient during VSED (95% CI: 0.326–0.703, p < .001) and by 69% among those who considered VSED a form of suicide (95% CI: 0.160–0.621, p = .001, R2 = 0.06). While accompanying a person during VSED, half (52%) of physicians considered the situation to be stressful for themselves; previous experience with VSED reduced stress by 52% (95% CI: 1.109–2.076, p < .009, R2 = 0.03). Three-quarters of respondents (78%) considered the VSED process to be stressful for relatives, and 59% assumed that relatives would have problems accepting their loved one’s decision.

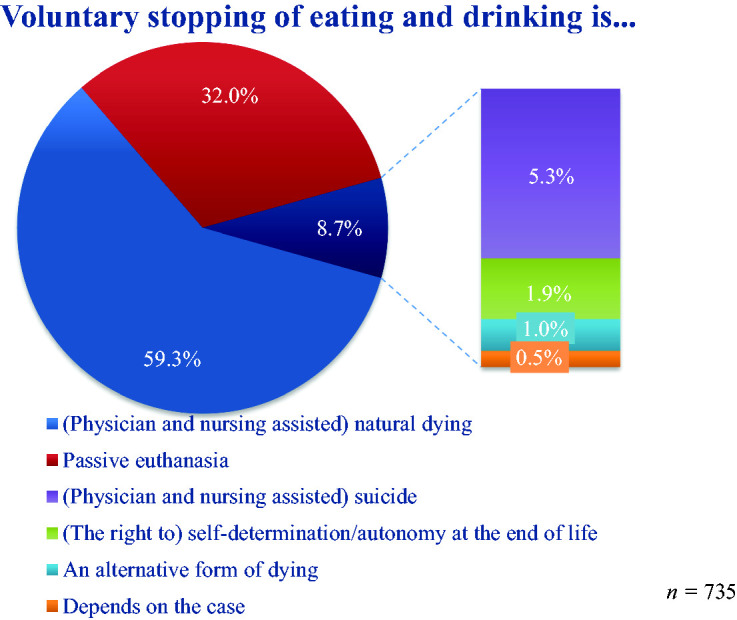

Family physicians’ assumptions about two forms of food refusal

Participants were asked to assess how often patients openly communicate their wish to die through VSED versus refusing to eat or drink without declaring the wish to die in this manner. This question regards patients who consciously and deliberately refuse to eat but do not inform people in their social environment; in this way, these patients engage in VSED secretly. It is also possible that certain individuals are privy to the individual’s real intention, but there is no clear communication of intention to the family physician. Respondents (n = 732) believed that many patients tend to stop eating without any communication about their intention (70%) and rarely (30%) announce their choice to engage in VSED. Family physicians were asked to estimate the age groups in which these two forms of food refusal most often occur. For both groups of patients, participants could give one or more responses for four age groups (≤45 years, 46–65 years, 66–75 years, >75 years). As seen in Figure 3, both forms of food refusal were estimated to occur in roughly equal proportions across age groups.

Figure 3.

Participants’ assumptions about the connections between age and two forms of food refusal.

Discussion

Almost half of all family physicians surveyed stated that they had previously accompanied a patient during VSED. Similar results were obtained in international studies.3,4,6 Furthermore, we found that 0.7% of all deaths in Switzerland in 2017 were owing to VSED, or 1.1% of all deaths that occurred at home or in a nursing home. In 2017, about one in eight family physicians in Switzerland had accompanied a patient who declared their wish to die by VSED. These results are comparable to results from the Netherlands, where between 0.4% and 2.1% of all deaths are owing to declared VSED.7,11

A new finding from this study is that, in addition to declared VSED, undeclared food refusal is also common. Based on the opinions of family physicians, undeclared food refusal occurs more frequently than declared VSED. Family physicians assume that about two of three cases of VSED remain unrecognised because patients do not talk openly about their plans. Professionals must be made aware of this. The refusal to eat is not always an expression of a wish to die. It can be misinterpreted; for example, patients may be in pain or homesick and stop eating as a result.46

That declared VSED is classified as a natural dying process5,9 is probably owing to the experiences of family physicians who described such death as dignified. Moreover, a good death is measured by one’s actions going hand in hand with the patients’ wishes;47 this is the case with VSED because a detailed consultation is a prerequisite before the patient can be accompanied in VSED by a physician. Further, pronounced VSED was classified as passive euthanasia by one-third of our respondents, which also represents attitudes in Germany.4 Whereas many physicians in the Netherlands classify declared VSED as suicide,3,7 few in the present study said they believed that VSED is equivalent to suicide. This quite different attitude regarding the classification of declared VSED is also discussed in the international literature.20,29,48–55 However, regression analysis showed that respondents who classify declared VSED as suicide are very open-minded toward it and would still be willing to accompany a willing patient. Our results regarding family physicians’ attitudes toward declared VSED can be compared with the findings of international studies, which show that pronounced death through VSED is often described as dignified.5 Furthermore, professionals would accompany a patient during VSED and can imagine this process as an option for themselves.56

It was striking that neither age (except concerning physicians’ recommendation for declared VSED), sex, nor professional experience had a significant influence on the responses of our participants regarding their decision to accompany a patient during VSED. It can therefore be assumed that professional understanding of how to accompany a person during VSED is similar among family physicians in Switzerland. Specifically, Swiss family physicians who have previously accompanied a patient during pronounced VSED are better able to accept patients’ decisions and have fewer moral concerns during VSED accompaniment.

The published literature reports3,7,19,28 that declared VSED can occur at any age, which was confirmed by participants in this study. Most physicians felt that both forms of food refusal occur mainly from the age of 75 years onwards. This is when the likelihood of having a disease, feeling lonely, or being dependent increases, which are also reasons to choose VSED.3,19 It is important to clarify the cause when a person expresses a wish to die by VSED or refuses to eat. All possibilities should be considered and options for resuming nutrition discussed. Only after clarifying the judgement ability of the person should an informed discussion follow in which all alternatives, including the VSED option, are addressed. We also recommend including relatives in these conversations, to ensure their support.

Limitations

Owing to the poor response rate, we had to deviate from the original recruitment strategy. We achieved an adequate response rate by changing from an online survey to a paper-and-pencil format. One limitation of our study was that we used retrospective data collection. Respondents report the number of accompanied VSED cases during the previous year; however, because VSED accompaniment is very intensive, we assumed that respondents’ memories would accurately reflect reality.

Conclusion

In this study, the occurrence among Swiss family physicians of accompanying declared VSED was described for the first time. This shows that 1.1% of all deaths at home or in a nursing home were owing to declared VSED. We estimate that two or more undeclared cases of food refusal occur for each case of declared VSED. Although VSED was classified heterogeneously among our participants, most equated it with a natural dying process or passive euthanasia. Although our respondents were generally very open in their basic attitude toward VSED, the personal experience of accompanying a person during the VSED process had an additional positive effect. Knowledge gaps among family physicians could be closed with further training. Practice recommendations should be developed for more standardized accompaniment of patients during VSED. In addition, an online platform might be helpful to collect the latest findings regarding declared VSED such that the current state of knowledge can be maintained up to date.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to all participating family physicians, without whom this study would not have been possible. Special thanks also go to Dr. Philippe Luchsinger and Reto Wiesli of Médecins de famille et de l’efance Suisse for their support in distributing our questionnaire. We also express our sincere thanks to the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences who supported us in this study.

Authors’ contributions

AF designed the study. All authors were responsible for data acquisition. SS analysed and interpreted the data. SS drafted the article, which was critically revised by WS, DB, CH, and AF. All authors contributed substantially to this work and agreed to the final version of the article.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research was sponsored by the funding program “Research in Palliative Care” of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences (SAMS), supported by the Stanley Thomas Johnson Foundation and the Gottfried and Julia Bangerter-Rhyner Foundation. This paper is independent research. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the SAMS.

ORCID iD

Sabrina Stängle https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1664-8824

References

- 1.Fringer A. Freiwilliger Verzicht auf Nahrung und Flüssigkeit am Lebensende - Die Sichtweise der Wissenschaft In: S Eychmüller, H Amstad. (eds) Freiwilliger Verzicht auf Nahrung und Flüssigkeit (FVNF). Folia Bioethica: Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Biomedizinische Ethik, 2015, pp.11–26. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohnsorge K, Rehmann-Sutter C, Streeck N, et al. Wishes to die at the end of life and subjective experience of four different typical dying trajectories. A qualitative interview study. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0210784. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolt EE, Hagens M, Willems D, et al. Primary care patients hastening death by voluntarily stopping eating and drinking. Ann Fam Med 2015; 13: 421–428. DOI: 10.1370/afm.1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoekstra NL, Strack M, Simon A. Physicians Attitudes on Voluntary Refusal of Food and Fluids to Hasten Death - Results of an Empirical Study Among 255 Physicians. Z Palliativmed 2015; 16: 68–73. DOI: 10.1055/s-0034-1387571. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganzini L, Goy ER, Miller LL, et al. Nurses’ experiences with hospice patients who refuse food and fluids to hasten death. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 359–365. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa035086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shinjo T, Morita T, Kiuchi D, et al. Japanese physicians’ experiences of terminally ill patients voluntarily stopping eating and drinking: a national survey. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2017; 9: 143–145. DOI: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2017-001426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chabot BE, Goedhart A. A survey of self-directed dying attended by proxies in the Dutch population. Soc Sci Med 2009; 68: 1745–1751. DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stängle S, Schnepp W, Büche D, et al. Long-term care nurses´ attitudes and the incidence of voluntary stopping of eating and drinking: a cross-sectional study. J Adv Nurs 2019; 76: 526–534. DOI: 10.1111/jan.14249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ivanović N, Büche D, Fringer A. Voluntary stopping of eating and drinking at the end of life - a ‘systematic search and review’ giving insight into an option of hastening death in capacitated adults at the end of life. BMC Palliat Care 2014; 13: 1–8. DOI: 10.1186/1472-684X-13-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stängle S, Domeisen Benedetti F, Fringer A. Sterbefasten - Freiwilliger Verzicht auf Nahrung und Flüssigkeit in der Onkologie. Onkologiepflege 2019; 2019: 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Penning C, et al. Trends in end-of-life practices before and after the enactment of the euthanasia law in the Netherlands from 1990 to 2010: a repeated cross-sectional survey. Lancet 2012; 380: 908–915. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmid M, Zellweger U, Bosshard G, et al. Medical end-of-life decisions in Switzerland 2001 and 2013: who is involved and how does the decision-making capacity of the patient impact? Swiss Med Week 2016; 146: w14307. DOI: 10.4414/smw.2016.14307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiler J. EXIT hat mehr leidende Menschen begleitet [EXIT has accompanied more suffering people], https://exit.ch/news/news/details/exit-hat-mehr-leidende-menschen-begleitet/ (2019, accessed 12 February 2019).

- 14.Donzé R. Sterbefasten fordert Schweizer Pflegeheime. NZZ am Sonntag, 2019.

- 15.Gigon A. Des résidents qui se laissent mourir. La Liberté, 2019.

- 16.Niedermann M. Fasten bis zum Tod. Report, SRF Schweiz Aktuell, Zürich, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frey O. Herausforderung fürs Gesundheitssystem. Report, Swiss Radio and Television, Switzerland, 2018.

- 18.Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences. Management of dying and death. https://www.samw.ch/en/Ethics/Ethics-in-end-of-life-care/Guidelines-management-dying-death.html (2018, accessed 6 August 2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Stängle S, Schnepp W, Büche D, et al. Pflegewissenschaftliche Erkenntnisse über die Betroffenen, den Verlauf und der Begleitung beim freiwilligen Verzicht auf Nahrung und Flüssigkeit aus einer standardisierten schweizerischen Gesundheitsbefragung. ZfmE 2019; 65: 237–248. DOI: 10.14623/zfme.2019.3.237-248. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernat JL, Gert B, Mogielnicki RP. Patient refusal of hydration and nutrition. An alternative to physician-assisted suicide or voluntary active euthanasia. Arch Intern Med 1993; 153: 2723–2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mattiasson AC, Andersson L. Staff attitude and experience in dealing with rational nursing home patients who refuse to eat and drink. J Adv Nurs 1994; 20: 822–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Druml C, Ballmer PE, Druml W, et al. ESPEN guideline on ethical aspects of artificial nutrition and hydration. Clin Nutr 2016; 35: 545–556. DOI: 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hopkinson JB. The nursing contribution to nutritional care in cancer cachexia. Proc Nutr Soc 2015; 74: 413–418. DOI: 10.1017/S0029665115002384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hopkinson JB. Nutritional support of the elderly cancer patient: the role of the nurse. Nutrition 2015; 31: 598–602. DOI: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arends J, Baracos V, Bertz H, et al. ESPEN expert group recommendations for action against cancer-related malnutrition. Clin Nutr 2017; 36: 1187–1196. 2017/07/12. DOI: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Volkert D, Chourdakis M, Faxen-Irving G, et al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in dementia. Clin Nutr 2015; 34: 1052–1073. DOI: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stängle S, Schnepp W, Fringer A. The need to distinguish between different forms of oral nutrition refusal and different forms of voluntary stopping of eating and drinking. Palliat Care Soc Pract 2019; 13: 1–7. DOI: 10.1177/1178224219875738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Der Heide A, Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Van Delden H, et al. Sterfgevallenonderzoek 2010: Euthanasie en andere medische beslissingen rond het levenseinde. https://publicaties.zonmw.nl/sterfgevallenonderzoek-2010-euthanasie-en-andere-medische-beslissingen-rond-het-levenseinde/ (2012, accessed 8 November 2019).

- 29.Fringer A, Fehn S, Büche D, et al. [Voluntary stopping of eating and drinking (VSED): suicide or natural decision at the end of life?]. Pflegerecht 2018; 7: 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lachman VD. Voluntary stopping of eating and drinking: an ethical alternative to physician-assisted suicide. Medsurg Nurs 2015; 24: 56–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Royal Dutch Medical Association and Dutch Nurses’ Association. Caring for people who consciously choose not to eat and drink so as to hasten the end of life. https://www.knmg.nl/advies-richtlijnen/knmg-publicaties/publications-in-english.htm (2014, accessed 6 August 2019).

- 32.Bickhardt J, Hanke RM. [Voluntary stopping of eating and drinking: a very individual way of acting]. Dtsch Arztebl 2014; 111: 590–592. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Birnbacher D. [Is voluntarily stopping eating and drinking a form of suicide?]. Ethik Med 2015; 27: 315–324. DOI: 10.1007/s00481-015-0337-9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quill TE. Voluntary stopping of eating and drinking (VSED), physician-assisted death (PAD), or neither in the last stage of life? Both should be available as a last resort. Ann Fam Med 2015; 13: 408–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simon A, Hoekstra NL. Sterbefasten - Hilfe im oder Hilfe zum Sterben? Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2015; 140: 1100–1102. DOI: 10.1055/s-0041-102835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saladin N, Schnepp W, Fringer A. Voluntary stopping of eating and drinking (VSED) as an unknown challenge in a long-term care institution: an embedded single case study. BMC Nurs 2018; 17: 39. DOI: 10.1186/s12912-018-0309-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gärtner J, Müller L. Ein Fall von ‘Sterbefasten’ wirft Fragen auf. Schweiz Ärzteztg 2018; 99: 675–677. DOI: 10.4414/saez.2018.06691. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fehn S, Fringer A. Notwendigkeit, Sterbefasten differenzierter zu betrachten. Schweiz Ärzteztg 2017; 98: 1161–1163. DOI: 10.4414/saez.2017.05863. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stängle S, Schnepp W, Mezger M, et al. Voluntary Stopping of Eating and Drinking in Switzerland From Different Points of View: Protocol for a Mixed-Methods Study. JMIR Res Protoc 2018; 7: e10358. DOI: 10.2196/10358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schuler M, Dessemontet P, Joye D. Eidgenössische Volkszählung 2000 - Die Raumgliederung der Schweiz [Federal Population Census 2000 - The geographical levels of Switzerland]. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/grundlagen/raumgliederungen.assetdetail.342284.html (2005, accessed 6 August 2019).

- 41.Hostettler S, Kraft E. FMH physician statistics 2017 - current statistics. Schweiz Ärzteztg 2018; 99: 408–413. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stängle S, Schnepp W, Mezger M, et al. Development of a Questionnaire to Determine Incidence and Attitudes to “Voluntary Stopping of Eating and Drinking”. SAGE Open Nurs 2019; 5: 1–7. DOI: 10.1177/2377960818812356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Federal Statistical Office. 2000 more deaths in Switzerland in 2017. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/kataloge-datenbanken/medienmitteilungen.assetdetail.5389171.html (2018, accessed 6 August 2019).

- 44.Federal Office of Public Health. Data situation on palliative care - evaluation of data on the place of death. https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/das-bag/publikationen/forschungsberichte/forschungsberichte-palliative-care/datensituation-zu-palliative-care.html (2016, accessed 6 August 2019).

- 45.Tschubby. Grossregionen der Schweiz (CC BY-SA 3.0) [Major regions of Switzerland (CC BY-SA 3.0)]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=54356664 (2019, accessed 1 January 2019).

- 46.Bartholomeyczik S. [Prevention of malnutrition in institutional long-term care with the DNQP “nutrition management” expert standard]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2019; 62: 304–310. DOI: 10.1007/s00103-019-02878-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gibson MC, Gutmanis I, Clarke H, et al. Staff opinions about the components of a good death in long-term care. Int J Palliat Nurs 2008; 14: 374–381. DOI: 10.12968/ijpn.2008.14.7.30772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alt-Epping B. [Con: voluntary stopping of eating and drinking is not a form of suicide]. Z Palliativmed 2018; 19: 12–15. DOI: 10.1055/s-0043-124167. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simon A. Pro: voluntary stopping of eating and drinking as suicide? Z Palliativmed 2018; 19: 10–11. DOI: 10.1055/s-0043-124169. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Requena P, Andrade ADS. Hastening death by voluntary stopping of eating and drinking. A new mode of assisted suicide? Cuad Bioet 2018; 29: 257–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McGee A, Miller FG. Advice and care for patients who die by voluntarily stopping eating and drinking is not assisted suicide. BMC Med 2017; 15: 222. DOI: 10.1186/s12916-017-0994-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jansen LA. Voluntary stopping of eating and drinking (VSED), physician-assisted suicide (PAS), or neither in the last stage of life? PAS: no; VSED: it depends. Ann Fam Med 2015; 13: 410–411. DOI: 10.1370/afm.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Quill TE, Lee BC, Nunn S. Palliative treatments of last resort: choosing the least harmful alternative. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132: 488–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pope TM. Voluntarily stopping eating and drinking (VSED) to hasten death: may clinicians legally support patients to VSED? BMC Med 2017; 15: 187. DOI: 10.1186/s12916-017-0951-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Christenson J. An Ethical Discussion on Voluntarily Stopping Eating and Drinking by Proxy Decision Maker or by Advance Directive. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2019; 21: 188–192. DOI: 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harvath TA, Miller LL, Goy E, et al. Voluntary refusal of food and fluids: attitudes of Oregon hospice nurses and social workers. Int J Palliat Nurs 2004; 10: 236–241. DOI: 10.12968/ijpn.2004.10.5.13072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]