Abstract

Background

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a global social and public health problem but published literature regarding the exacerbation of physical IPV during the COVID-19 pandemic is lacking.

Purpose

To assess the incidence, patterns, and severity of injuries in victims of intimate partner violence (IPV) during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, compared with the prior three years.

Materials and Methods

The demographics, clinical presentation, injuries, and radiological findings of patients reporting physical abuse arising from IPV during the statewide COVID-19 pandemic between March 11th and May 3rd, 2020 were compared with the same period over the past three years. Pearson’s chi-squared and Fischer’s exact have been used for analysis.

Results

26 physical IPV victims from 2020 (37+/-13 years, 25 women) were evaluated and compared with 42 physical IPV victims (41+/-15 years, 40 women) from 2017-2019. While the overall number of patients reporting IPV decreased during the pandemic, the incidence of physical IPV was 1.8 times greater (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1 to 3.0, p = 0.01). The total number of deep injuries was 28 during 2020 versus 16 from 2017-2019; the number of deep injuries per victim was 1.1 during 2020 compared with 0.4 from 2017-2019 (p<0.001). The incidence of high-risk abuse defined by mechanism was greater by 2 times (95% CI 1.2 to 4.7, p = 0.01). Patients with IPV in during the COVID-19 pandemic were more likely to be ethnically white, 17 (65%) victims in 2020 were ethnically white compared to 11 (26%) in the prior years (p=0.007).

Conclusion

There was a higher incidence and severity of physical intimate partner violence (IPV) during the COVID 19 pandemic compared with the prior three years. These results suggest that IPV victims delayed reaching out to health care services until the late stages of the abuse cycle during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Summary

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a higher rate of physical intimate partner violence (IPV) with more severe injuries on radiology images - despite fewer patients reporting IPV.

Key Results

■ Compared with 2017-2019, the incidence of physical intimate partner violence (IPV) in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic was 1.8-fold (p=0.01) higher.

■ The number of deep injuries during the pandemic period of observation was 28 compared to a total of 16 deep injuries during the prior 3 years.

■ The reported ethnicity of victims of IPV was white in 17 (65%) individuals in 2020 versus 11 (26%) white individuals in the prior three years, p=0.007).

Introduction

COVID-19 started in China in late December of 2019 and spread to the entire world, with 16,341,920 positive cases and 650,805 death as of July 29, 2020 (1). In response to this pandemic, most countries adopted quarantines, social isolation, travel restrictions, and stay-at-home orders. Although the degree of COVID-19 pandemic closures of business and schools varied between countries, most non-essential businesses closed, and hospitals shut down any elective procedures and non-emergent outpatient visits. Social distancing has proven to be effective for controlling the spread of infection but with negative socioeconomic and psychological impacts (2-4). Especially affected, service-oriented economies have seen increased unemployment and a higher incidence of substance/alcohol abuse or mental disorders(4, 5).

Emerging data shows that since the outbreak of COVID-19, reports of intimate partner violence (IPV) have increased worldwide as a result of mandatory “lockdowns” to curb the spread of the virus (6, 7). The UN Chief has described the current situation as a “horrifying global surge in domestic violence” (8). Even in the absence of a global pandemic, IPV is a common social and public health problem worldwide. According to the national survey in 2015, 1 in 4 women and nearly 1 in 10 men have experienced IPV during their lifetime in the United States (9). It is challenging to help IPV victims in the time of the pandemic when the majority of healthcare providers are overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients (10). Therefore, the role of radiologists in identifying victims of IPV through radiological studies has become crucial when there is limited personal contact during a health care visit due to social distancing.

Anecdotally, despite a decrease in our overall imaging volume, we encountered severe physical injuries related to IPV in the Emergency Department during the COVID-19 pandemic. We expected to see a greater number of victims of IPV during the pandemic as IPV victims are quarantined with their abusers at home, which is considered to be the most dangerous environment for victims (8, 11-13). Socioeconomic instability related to stay at home orders and business closures increased substance abuse, and lack of community support would be expected to further contribute to an increased occurrence of IPV. Therefore, the purpose of our study was to assess the incidence, pattern and severity of injuries related to IPV at our institution during COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., from March 11th to May 3rd), and compare it with the prior three years.

Materials and Methods

Patients

This Institutional Review Board-approved, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant, retrospective study was conducted at a large, urban academic medical center located in the northeast United States. Written informed consent was waived. Since 1997, all patients screening positive or reporting IPV are referred to our institutional domestic violence intervention and prevention program. The program has grown substantially since its establishment, although there has been no change in the number of referral sites or data collection over the last four years. Data for patients with IPV reports were obtained from our institution’s IPV prevention program for the period of COVID-19 crisis from March 11, 2020 to May 3, 2020 and for the same period of time for the three prior years (2019, 2018, and 2017) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the COVID-19 pandemic victims and control groups.

Data Collection

Four radiologists in the emergency radiology fellowship training program (BG, 7 years; HP, 11 years; RT, 11 years; RG, 12 years of experience in radiology) divided up the physical IPV victims and reviewed the institution’s electronic health record of each victim. In addition to extracting age, sex, race, marital status, history of substance use, they reviewed the health care provider's notes for the mechanism of injury, injuries documented in the physical examination, surgical notes, and reviewed the radiological studies.

Imaging Findings

All radiology reports and images were reviewed by the same four radiologists. Injuries were grouped into nine anatomical areas- head, face, cervical spine, thoracic spine, lumbar spine, chest, abdomen, upper limb, and lower limb. A single injury was defined as physical trauma to one site. In patients with multiple injuries, injury to each organ/ site was counted as one injury. Deep injuries include injuries to deep internal organs. For instance, if a patient had liver laceration, renal laceration, and hemoperitoneum secondary to bowel injury, the total number of injuries in that patient were counted as three deep injuries in the abdomen.

Injuries were classified as central and peripheral. Central injuries included injuries of the head, face, spine, chest, and abdomen. Peripheral injuries included injuries of the upper and lower extremities. Injuries were also classified as superficial and deep injuries. Superficial injuries included injuries to the skin, subcutaneous soft tissues and muscles; as indicated above, deep injuries include injuries to deep internal organs.

Grading of IPV Based on Objective Signs of Abuse

We developed an objective grading system by considering the anatomical location of the physical injuries by dividing the body into six major parts (head and face, neck, chest, abdomen, extremities, and spine) and considering the depth of injuries (superficial injuries and deep injuries). Four grades of IPV based on the anatomical location and depth of injury defined the severity of physical injuries of IPV, as Grade 1 (mild), Grade 2 (moderate), Grade 3 (severe), and Grade 4 (very severe), summarized in Table 1. Additionally, the Injury Severity Scale (ISS) was calculated for each year by a registered trauma nurse with 5 years of experience in injury scoring. The injury severity score (ISS) is an anatomical scoring system that provides an overall score for patients with multiple injuries. Each injury is assigned a severity and is allocated to one of six body regions (head or neck, facial, chest, abdominal or pelvic, extremities, external and other trauma). The ISS score ranges from 3 (minor injury) to 75 (most severe injury).

Table 1.

Grading of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Based on Injuries

Outcome Measures

The outcome measures compared the following incidence between the COVID-19 pandemic and the same period over 2017-2019; (1) the incidence of physical IPV, defined as the total number of victims sustaining physical injuries from domestic violence per time period, (2) the incidence of severe and very severe physical IPV, defined as the total number of victims sustaining grade 3 injuries and grade 4 injuries respectively per time period, (3) the absolute number of injuries classified as central versus an extremity injury, (4) the absolute number of deep injuries versus superficial injuries, (5) the incidence of high-risk mechanism of abuse by reported history, defined as the total number of victims sustaining injuries due to strangulation, stab injuries, burns or use of weapons such as knives, guns and other objects that could inflict deep injuries per time period and the Injury Severity Scale.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for continuous measures are presented as means with standard deviations and as frequencies with proportions for categorical measures. The mean age of individuals experiencing physical IPV was compared between 2020 and 2017-2019 using a two-independent samples t-test. Race/ethnicity and the proportion of individuals experiencing substance abuse were compared between the same time periods using a Fisher's exact test and Pearson's chi-squared test, respectively. The incidence of physical IPV, severe IPV, very severe IPV, high risk abuse mechanisms, and deep injuries was compared between 2020 and 2017-2019 using Poisson regression with a log link. Additionally, the proportion of individuals having an injury classified as central versus extremity and deep versus superficial only, were compared using a Pearson's chi-squared test. Lastly, a Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare distributions of ISS scores between the two time periods. All testing was two-tailed and p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. No patients were present in more than a single year of data; therefore, no accounting for clustered data was required. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient Demographics

A total of 62 IPV victims of all types (physical and non-physical abuse) were identified in 2020; 104 in 2019; 106 in 2018; and 146 in 2017 for this seven-week time window. Thus, the overall number of reported IPV victims of all types (including physical and non-physical abuse) during 2020 was 62 victims compared to 342 victims during the prior years (114 per each year), i.e., 0.5 times the incidence in 2020 versus 2017-2019 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.4 to 0.7, p<0.001). Of all the victims of IPV, 20/62 (38%) victims were referred from the Emergency Department during the pandemic as opposed to 62/342 (18%) victims from 2017-2019.

From these IPV victims, we identified victims reporting physical IPV: 26/62 patients for 2020, 20/104 patients for 2019, 7/106 patients for 2018 and 15/146 patients for 2017 which constituted the study sample (Figure 1).

The average age of the 26 physical IPV victims from 2020 was 37+/-13 years of age (25 women) versus 41+/-15 years of age (40 women) for 42 physical IPV victims from 2017-2019.17 victims in 2020 reported white ethnicity (17/26 = 65%) compared with 11 victims in 2017-2019 (11/42 = 26%) (p=0.007 across all race categories). Only 2 victims were African American in 2020 (2/26=8%) compared with 15 in 2017-2020 (15/42= 35%). 10 victims reported substance abuse in 2020 (10/26= 38%) compared with 11 victims in 2017-2019 (22/42= 26%) [p=0.29] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of Demographic Variables, Injury Patterns, and Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Grading in Victims of Physical Abuse between 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic Group and Victims of 2017, 2018, and 2019.

Description of IPV Injuries

As indicated above, the number of victims sustaining physical IPV was 26 during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to 20 in 2019, 7 in 2018 and 15 in 2017. Five victims of severe abuse classified as grade 3 were identified in 2020 (5/26=19%) compared to 1 in 2019 (1/10= 5%); 1 in 2018 (1/7=14%); and 1 in 2017(1/15=7%). 5 victims of very severe abuse classified as grade 4 were identified in 2020 (5/26=19%) compared to 2 in 2019 (2/10= 10%); 1 in 2018 (1/7=14%); and 1 in 2017 (1/15=7%).

Compared to 2017-2019, the incidence of physical IPV was 1.9 times greater in 2020 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1 to 3.0, p = 0.01). Compared to 2017-2019, the incidence of severe grade IPV (classified as grade 3) was 5 times greater in 2020 (95% CI 1.1 to 20.9, p = 0.03), with very severe grade IPV classified as grade 4, the incidence was 3.8 times greater in 2020 (95% CI 1.0 to 14, p=0.049) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Graph illustrates year-wise comparison of total intimate partner violence (IPV), physical intimate partner violence (IPV), severe and mild grades of physical intimate partner violence (IPV).

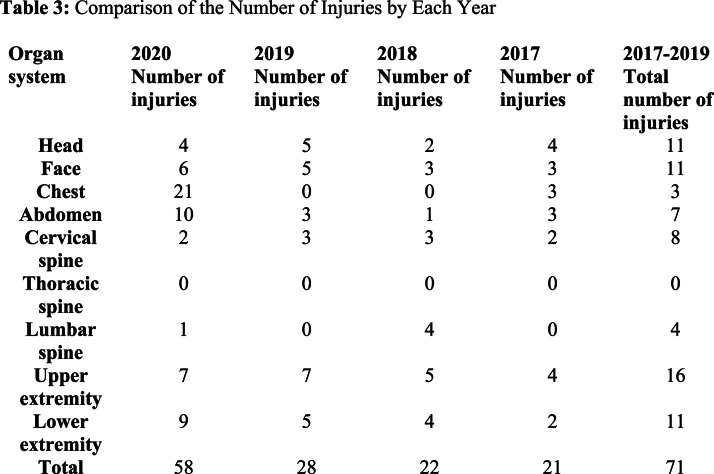

58 injuries were observed in the victims of physical IPV in 2020 compared to 28 in 2019; 22 in 2018; and 21 in 2017. Among these, 28 deep injuries were seen in the victims of COVID 19 pandemic compared to 7 in 2019; 5 in 2018; and 4 in 2017, with a mean of 1.1 deep injuries (2.2 total injuries) per person compared to 0.4 deep injuries (1.7 total injuries) per person in 2017-2019 (p<0.001).

The total number of central injuries in 2020 were 44 compared to 16 in 2019, 13 in 2018, and 15 in 2017. The total number of central injuries compared with extremity injuries was higher in 2020 (46/12 injuries) compared with 2017-2019 (44/27 injuries) (p=0.03) (Figure 3, Table 3).

Figure 3.

Graph illustrates organ wise injuries for victims of intimate partner violence (IPV) based on the year.

Table 3:

Comparison of the Number of Injuries by Each Year

Figure 4.

Images in a 27-year-old female victim was stabbed in the right mid abdomen by her boyfriend. (a) Axial abdomen CT scan demonstrates an AAST (American Association for the Surgery of Trauma) grade 2 liver laceration (arrowhead) with a small perihepatic hematoma (asterisk), and subcutaneous emphysema (arrow) at the site of stab injury. (b) Additional axial CT abdomen image demonstrated irregular hypoattenuation in the inferior aspect of left kidney, representing an AAST grade 2 laceration. The patient underwent surgical repair of liver laceration and cholecystectomy. The renal injury was managed conservatively.

Figure 5.

Images in a 38- year-old female victim struck in the face and chest by her boyfriend. The patient sustained multiple right sided rib fractures. (a) Axial post contrast chest CT demonstrates a comminuted right fourth rib fracture (arrow), extensive swelling of right breast (arrowheads) and anterior chest wall muscle (asterisk), suggesting contusion and intramuscular hematoma. (b) Ground-glass opacity in the right lung peripherally suggestive of lung contusion (arrow). (c) Additional chest CT image through apices on lung window demonstrates trace right apical pneumothorax (arrow). (d) Bilateral rib fractures (arrowheads).

Figure 6.

Images in a 35-year-old female victim was strangulated and hit on the face multiple times by her boyfriend. (a) Coronal reconstructed non-contrast face CT demonstrates acute comminuted inferiorly displaced fracture of the left inferomedial orbital wall (arrow), with herniation of fat and inferior rectus muscle into the left maxillary sinus. Asymmetric subcutaneous swelling is noted on the left. (b) Axial face CT image demonstrates a minimally displaced left nasal bone fracture (arrow). The patient underwent surgical repair of the left orbital wall.

15 victims suffered abuse from high risk abuse mechanisms in 2020 compared to 6 in 2019; 6 in 2018; and 7 in 2017. The incidence of high-risk abuse mechanism by reported history was greater by 2.4 times (95% CI 1.2 to 4.6, p = 0.01) compared with 2017-2019.

ISS scores for victims during 2020 had a mean of 3.0 (range 1-10); 2019 had a mean of 1.3 (range 1-4); 2018 had a mean of 1.0 (range 1-1); and 2017 had a mean of 2.6 (range 1-9) (p = 0.17 for comparison of ISS by year).

Radiological Studies

Radiology studies were performed in 17 victims in 2020 (17/26=65%) compared with 27 victims from 2017-2019 (27/42=64%). Studies from 7 victims were positive for physical injuries in 2020 (7/26=27%) compared to 12 victims from 2017-2020(12/42=28%). Remote injuries were seen in 1 victim in 2020 (fifth metatarsal fracture), 1 victim in 2019 (zygomatic bone fracture), and 1 victim in 2017 (nasal bone fracture).

Discussion

Our results showed that there was an overall decrease in the total number of IPV victims seeking hospital care during the pandemic (62 victims in 2020; 104 in 2019; 106 in 2018; and 146 in 2017, p<0.001). However, the incidence of physical abuse IPV and severity of injuries was greater during the pandemic: the number of victims of physical abuse was 26/62 (42%) in 2020 vs. 42/342 (12%) in 2017-19 (p = 0.01), and the number of victims of severe grade injury was 10 (38%) in 2020 vs. 7 (17%) in 2017-2019 (p = 0.03). This could be related to the closure of ambulatory/community referral sites during the pandemic and fear of being exposed to the virus in the Emergency Department, similar to other diseases (14, 15). We also observed a higher incidence of victims of high-risk abuse, including strangulation, use of weapons, stab, and burns. Radiological studies showed more central and visceral organ injuries during the 2020 state of emergency, which are suggestive of high-risk abuse (16, 17). This could potentially reflect that victims are reporting at the later stage of IPV, and victims of mild physical or emotional abuse are not seeking help at all when they usually visit clinics in the pre-pandemic period.

Women killed by intimate partners or family members account for 58% of all female homicide (12). Because victims reach out to health care providers before they present to social service or criminal justice, IPV screening is recommended by many health care organizations with an emphasis on appropriate referral and intervention of IPV (18). But the actual screening implementation rate reported in clinics is low at 1.5-13%, and IPV is still under-diagnosed (19-21). Especially in the time of the pandemic, in addition to underreporting, IPV-related injuries could be overlooked or misinterpreted while healthcare providers are overwhelmed by a vast number of COVID-19 patients in the emergency department. During this global public health crisis, alternative options for IPV victims to seek help have decreased. Many ambulatory clinics are no longer seeing as many patients in person due to the virus and are instead pivoting their services to virtual consultation. Telehealth visits limit the opportunity to visualize bruises or other signs of physical trauma and hamper the ability of the health care provider to gather nonverbal cues. It may also be difficult for victims who are at home to report IPV, and health care providers may be omitting IPV screening questions altogether on these calls due to patient’s limited privacy.

We believe that it is the right moment for radiologists to play a critical role as a team in identifying victims of IPV and become an integral member of the multidisciplinary teams providing direct care to these patients. With high-risk physical abuse being highly associated with homicide, a smaller number of victims seeking medical care, and emergency medicine physicians overwhelmed with treating COVID-19 victims, radiologists should embrace the opportunity to provide patient-centered care by integrating longitudinal imaging data and providing early identification of victims. By recognizing high imaging utilization, location and imaging patterns specific to IPV, old injuries of different body parts, and injuries inconsistent to provided history, radiologists can identify victims of IPV even when the victims are not forthcoming (22, 23). As radiologists are more becoming familiar and comfortable with various artificial intelligence algorithms, a clinical decision support rule-based on imaging and clinical risk factors can be established to proactively detect victims with more business and school closings expected in the future (7, 24).

This study has several limitations. First, this is a retrospective observational study from a single institution with a small number of IPV victims. Second, we focused on victims with physical injury only and did not review radiological studies of the patients who did not report physical IPV. Third, our injury severity scale is based on documented physical examination and radiological findings, not accounting for reported history. A patient with a reported history of strangulation with no physical or radiological findings will still be placed in Grade 1, though we also analyzed and compared the numbers of high-risk abuse, such as strangulation, weapons, stab, and burns individually.

Conclusion

An overall lower number of intimate partner violence (IPV) victims with a greater number and severity of physical abuse is suggestive of victims reaching out to healthcare services in their later stage of abuse due to fear of COVID-19. This may be due to limited availability of services and resources for victims during the pandemic. Radiologists and other health care providers should proactively participate in identifying IPV victims and reaching out to vulnerable communities as an essential service during the pandemic and other crisis situations.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Rohan Chopra for his assistance with manuscript editing and proofreading.

B.G. and H.P. contributed equally to this work.

Funding Information

Partners Innovation Discovery Grant, Mass General Brigham

Stepping Strong Injury Prevention Innovator award, Stepping Strong, Brigham Health

Brigham Care Redesign Incubator and Start up Program, Brigham Health

Abbreviations:

- IPV

- Intimate Partner Violence

- CI

- Confidence Interval

References

- 1.Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Situation Report – 190. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200728-covid-19-sitrep-190.pdf?sfvrsn=fec17314_2. Published July 28, 2020. Updated July 28, 2020. Accessed July 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkeson A. What will be the economic impact of COVID-19 in the US? Rough estimates of disease scenarios. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w26867. Published in March 2020. Updated in March 2020. Accessed July 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozili PK, Arun T. Spillover of COVID-19: impact on the Global Economy. SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3562570. Published March 27, 2020. Updated March 27, 2020. Accessed July 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. General psychiatry 2020;33(2): e100213. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental Health and the Covid-19 Pandemic. The New England journal of medicine 2020;383(6):510-512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boserup B, McKenney M, Elkbuli A. Alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med 2020; S0735-6757(20)30307-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matoori S, Khurana B, Balcom MC, Koh DM, Froehlich JM, Janssen S, Kolokythas O, Gutzeit A. Intimate partner violence crisis in the COVID-19 pandemic: how can radiologists make a difference? European radiology 2020:1-4. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07043-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.UN chief calls for domestic violence ‘ceasefire’ amid ‘horrifying global surge’. United Nation News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/04/1061052. Published April 6, 2020. Updated April 6, 2020. Accessed May 18, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith SG, Zhang X, Basile KC, Merrick MT, Wang J, Kresnow M-j, Chen J. The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey: 2015 data brief–updated release. 2018. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/2015data-brief508.pdf. Published November 2018. Updated November 2018. Accessed July 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roesch E, Amin A, Gupta J, García-Moreno C. Violence against women during covid-19 pandemic restrictions. BMJ 2020;369:m1712. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradbury-Jones C, Isham L. The pandemic paradox: The consequence of COVID-19 on domestic violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2020;29(13-14):2047-2049. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Global study on homicide: Gender-related killing of women and girls. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/GSH2018/GSH18_Gender-related_killing_of_women_and_girls.pdf. Published November 2018. Updated November 2018. Accessed July 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bosman J. Domestic Violence Calls Mount as Restrictions Linger: ‘No One Can Leave’. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/15/us/domestic-violence-coronavirus.html?campaign_id=2&emc=edit_th_200517&instance_id=18495&nl=todaysheadlines®i_id=67605176&segment_id=28156&user_id=a2712d6899381f929013dc043baab6e0. Published May 15, 2020. Updated May 15, 2020. Accessed May 18, 2020. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/05/12/metro/when-is-drop-domestic-violence-bad-news/. Published May 12, 2020. Updated May 12, 2020. Accessed May 18, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Southall A. Why a Drop in Domestic Violence Reports Might Not Be a Good Sign. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/17/nyregion/new-york-city-domestic-violence-coronavirus.html. Published April 17, 2020. Updated April 17, 2020. Accessed May 18, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu V, Huff H, Bhandari M. Pattern of physical injury associated with intimate partner violence in women presenting to the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 2010;11(2):71-82. doi: 10.1177/1524838010367503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhandari M, Dosanjh S, Tornetta P, III, Matthews D, Collaborative VAWHR. Musculoskeletal manifestations of physical abuse after intimate partner violence. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 2006;61(6):1473-1479. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196419.36019.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narayan AK, Lopez DB, Miles RC, Dontchos B, Flores EJ, Glover Mt, Lehman CD. Implementation of an Intimate Partner Violence Screening Assessment and Referral System in an Academic Women's Imaging Department. Journal of the American College of Radiology 2019;16(4 Pt B):631-634. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2018.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamberger LK, Saunders DG, Hovey M. Prevalence of domestic violence in community practice and rate of physician inquiry. Family medicine 1992;24(4):283-287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abbott J, Johnson R, Koziol-McLain J, Lowenstein SR. Domestic violence against women. Incidence and prevalence in an emergency department population. JAMA 1995;273(22):1763-1767. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.22.1763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chamberlain L, Perham-Hester KA. The impact of perceived barriers on primary care physicians' screening practices for female partner abuse. Women & health 2002;35(2-3):55-69. doi: 10.1300/J013v35n02_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.George E, Phillips CH, Shah N, Lewis-O'Connor A, Rosner B, Stoklosa HM, Khurana B. Radiologic Findings in Intimate Partner Violence. Radiology 2019;291(1):62-69. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019180801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rivara FP, Anderson ML, Fishman P, Bonomi AE, Reid RJ, Carrell D, Thompson RS. Healthcare utilization and costs for women with a history of intimate partner violence. Am J Prev Med 2007;32(2):89-96. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khurana B, Seltzer SE, Kohane IS, Boland GW. Making the ‘invisible’visible: transforming the detection of intimate partner violence. BMJ quality & safety 2020;29(3):241-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]