Abstract

The novel Coronavirus pandemic defines a new risk for all dental practitioners, hygienists, and dental assistants. As an increasing number of dentists are now developing this disease, we wanted to provide some measures to manage this risk in the dental practice, by undergoing a review of the current literature. This minireview searches the literature for articles that both defined the infection risk in the dental practice and provided evidence on the efficacy of some procedures on reducing the infection risk. Several articles have already pointed out some necessary measures: fewer patients have to be admitted to the practice, a short triage should be carried out, and the appropriate measures of protection have to be used. On the basis of the literature collected, a short questionnaire and a flowchart is proposed to define the risk that each patient carries, and to appropriately adapt each procedure based on the patient’s risk. The literature is still limited on this subject, but on the basis of what is available, dental practices have to adapt to the situation in order to protect dental health professionals.

Impact statement

Dentists have always been taught how to protect themselves and their patients from potential blood-borne pathogens, but the Coronavirus pandemic has brought a new unprecedented challenge to the world of dentistry; we therefore reviewed the literature to provide suggestions on how to accordingly change dental practice prevention.

Keywords: Coronavirus, dentistry, risk management

Introduction

The novel Coronavirus, officially named as SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2), is a newly discovered virus, responsible for the so-called COVID-19, an infection of the upper airways.

After a median incubation period of 3.0 days,1 the main clinical symptoms of the infection were described to be fever, cough, fatigue, anosmia, and ageusia,2 with some of these patients also developing conjunctivitis as a consequence of the virus spreading to the ocular area.3

The time from onset to the development of an acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) was recorded to be only 9 days in the initial patients,4 and in those who developed this condition, several comorbidities (such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity) are much more frequent.5,6 Currently, the main treatment for the COVID-19 infection is a symptomatic one, but several pre-existent drugs are being tested, and the preliminary results are promising.7

Searching on ClinicalTrials.com with the keyword Covid-19, we found 6818 different clinical trials studying different aspects of Covid-19 and testing various drugs. For example, in the United States, Remdesivir, previously used to treat Ebola, is being tested9 in Trials NCT04292899, NCT04280705, and NCT04292730, which are still in the recruiting phase.10 Moreover, 15811 clinical trials are investigating the effects of hydroxychloroquine, an anti-malarial drug, as in-vitro studies have shown its efficacy.12 The results of these trials are highly anticipated.

The common transmission routes of coronavirus include direct transmission and indirect transmission; eye exposure may also provide a way for the virus to enter the body,13 and its infectivity has been demonstrated to be even higher than that of the original SARS.4

Healthcare professionals are in extreme danger of contracting this virus; it is not surprising that they represent 9% of all the infected individuals.14

Dental practitioners are also exposed to high risks of contracting COVID-19, due to their direct exposure to saliva and blood.15

At the moment, several countries have issued some levels of quarantine measures, to “flatten the curve” during this first outbreak, and dentists have been instructed to only provide emergency treatments for the time being.

Going forward, as SARS-CoV-2 is going to represent a menace presumably until a vaccine is developed and distributed, dental practitioners have to adapt their practices to protect themselves and their patients from this infection. This minireview searched the literature for procedures that could significantly reduce the risk of an operator or a dental assistant to get contaminated, while at the same time protecting their patients.

Discussion

The literature was searched using the following MeSH terms: “disinfection,” “dentistry,” “triage,” “dental infection control,” “dental infection,” and “coronavirus.” The research was then extended to sites of major disease control authorities and dental societies. An additional hard research on selected articles was performed.

Routes of transmissions and possible risks in a dental practice

Several dental instruments aerosolize saliva or blood to the surroundings, especially when using an ultrasonic instrument; it is possible that the whole dental apparatus could be contaminated by the SARS-CoV-2 after these procedures; it is not surprising that dental hygienists are more exposed to this infection than actual dentists.16

The SARS-CoV-2019 can remain viable in aerosol for over 3 h and can be detected on several surfaces even after 72 h, although at a greatly reduced virus titer.17

It is not certain if it is possible to get infected via a glove puncture, but this eventual risk can be notably reduced following the same practices that have been followed by the dental community for the protection from several blood-borne pathogens.18

Also one should remember that this risk does not only come with symptomatic patients, as recent evidence has demonstrated that subclinical patients can spread COVID-19.19

Reduce the number of patients and provide preventive measures

Reducing the number of patients coming to a practice can be extremely helpful in avoiding cross-infections in dental patients.20

By having fewer people in the waiting room at the same time, it is quite easier to maintain a distance of 2 m (±6.5 feet) between each other, as a distance of approximately at least 1 m (3.2 feet) has been established as an area of risk,21 and reducing the number of patients can provide the staff with the time needed to properly disinfect the clinical area. It is advisable to reduce the on-site waiting-time, and, if possible, schedule vulnerable patients (i.e. immunosuppressed, or affected with serious systemic comorbidities) at the end of the day, when the waiting room should be empty.

Patients should be provided with an antiseptic gel as soon as they enter the waiting room, as hand disinfection is the main approach in stopping the spread of this virus, and with a surgical mask that meets a minimum protection level of 1 according to the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) classification,22 as it can block up to 97.14% of the virus in aerosols;23 their temperature should be measured.

Short telephone triage

Before admitting any patient to the practice, any sign of COVID-19 should be properly assessed, as other medical specialties are now doing.24

This can easily be done with a short triage, assessing the presence of the clinical elements that are more frequently linked to this disease, especially in its early stages (fever, cough, fatigue6); this procedure can be carried out on the phone, and can easily be done by a properly trained assistant, 1 or 2 days before the actual procedure.

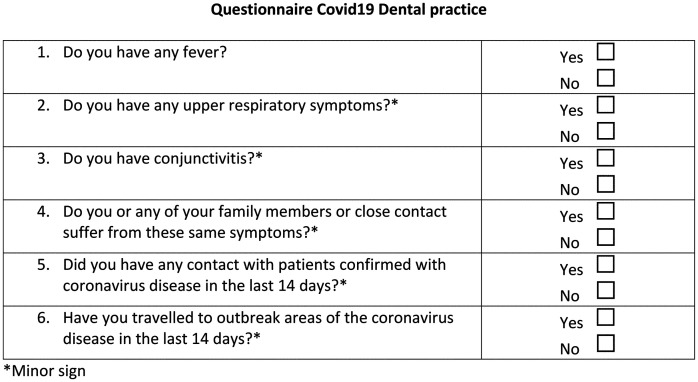

We propose this simple questionnaire, which can be easily delivered on the phone (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Covid-19 questionnaire.

Protective measures

Conventional protective measures are not sufficient to protect healthcare personnel from getting infected; several reports have suggested different measures, but there is a clear lack of evidence on what the standard should be for dentists, even though, to the date this paper was drafted, several cases of infection between dental practitioners have been recorded. As defined by Peng et al.,25 the main difference in the protection that a clinician has to wear when treating a suspected COVID-19 patient in a dental practice is in the isolation clothing and in the face mask.

Respiratory protection is usually classified in three grades: FFP(1,2,3).

This subdivision accounts for their filtering and face adhesion capabilities;26 it is recommended to use at least a FP2 face mask when in contact with an infected patient or a suspected one, as simple surgical masks were made to protect patients from droplets coming from surgeons, not the other way around.

Using the dental dam

The dental dam can effectively reduce the amount of aerosol formed; therefore, it should be used in any procedure that allows doing so, as it has been reported that the rubber dam can reduce airborne particles by 70%.27

Clearly, rubber dam isolation is not always possible, so in some cases, hand scaler can be recommended for periodontal scaling.25

Preoperative mouthwash

Dentists commonly administer mouthwashes to patients before surgical procedure, as it has been proven that this procedure can effectively reduce the risk of an infection in the surgical site.28

Administering a mouthwash could reduce the presence of the virus in the oral cavity and reduce the risk of aerosol transmission; we know that mouthwashes can be effective in reducing the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia29 and several reports have proven how Povidone-Iodine at a dilution of 7% is effective in reducing the viral count of SaRS-CoV in vitro.30,31

Therefore, it is at least logical, as there is no evidence that mouthwashes could effectively reduce the presence of this virus in the aerosol created during the procedure.2

Environmental sanitation

Given the capability of the SARS-CoV-2 of surviving over surfaces for at least several hours, it is crucial to perform an appropriate sanitation of the potentially contaminated environment.

Several formulations are capable of deactivating the virus (such as sodium hypochlorite 0.5%–5%, or Povidone-Iodine 10%),32 and many of these are already commonly used in dental offices. If these formulations are lacking, the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) advises using neutral soap, or for surfaces that can be damaged by these substances, a 70% alcohol solution.32

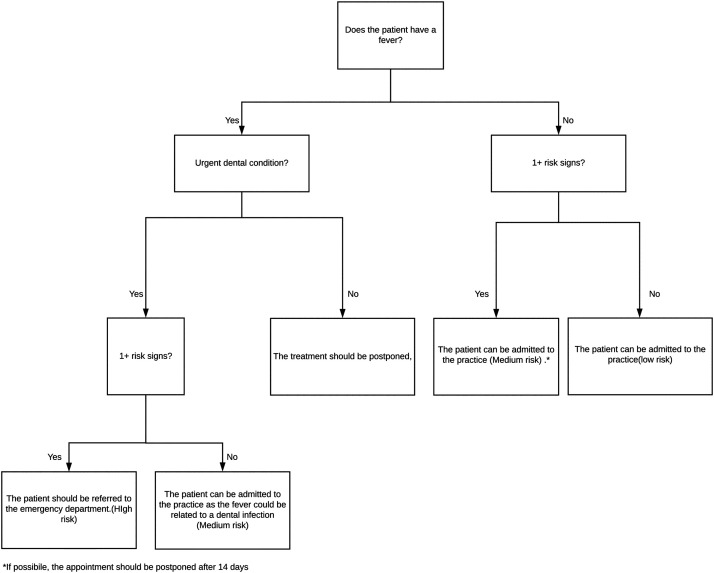

Following what has been proposed in China in an ophthalmological practice,20 we propose a protocol that outlines the protective measures that should be carried out on each patient, according to their personal risk of infection.

Each patient is defined according to their answers to the questionnaire as: “low-risk patient,” “medium-risk patient,” or” high-risk patient” (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Covid-19 flowchart.

We then propose to divide procedures into two classes: “high-risk procedures” and “low-risk procedures.”

Procedures that carry a high risk are all the procedures that can produce high levels of aerosol, so (a) procedures that involve an ultrasonic instrument, or (b) procedures that involve a high-speed handpiece and cannot be carried out with dental dam isolation.

All other procedures can be defined as low risk.

Low-risk patients

Low-risk procedure

The patient should be administered a 7%–10% Povidone-Iodine mouthwash before the procedure;2 the clinician and the assistant should wear a surgical mask, normal work clothes, surgical gloves, and protective goggles. This suggestion is based on the highly probable event that there is going to be a shortage in FP2 and above masks, and that they are going to be quite difficult to buy for the average dentist; we also advise to always use a FP2 mask.

After the procedure, the dental chair should be appropriately disinfected, and the clinician should maintain extremely accurate hygiene between each appointment.

High-risk procedures

The patient should be administered a 7%–10% Povidone-Iodine mouthwash before the procedure, and the clinician and the assistant should wear a FP2 surgical mask, a surgical gown (as long as it is single-use and waterproof) surgical gloves, and a protective facemask/protective goggles. After the procedure, the room should be appropriately cleaned with one of the products we previously mentioned, and, given the risk of aerosols remaining in the air, it is advisable to wait at least for one hour before allowing another patient in the room, if they are not functioning under negative pressure.

Medium-risk patients

Appointments for medium-risk patients should preferably be postponed at least for 14 days, and then, their clinical status can be updated according to the workflow.

If the appointment cannot be postponed, they can be treated, but their appointment should be left at the end of the day, and every procedure should be treated as a Medium-Risk one, following the appropriate guidelines.

High-risk patients

Patients with a high risk of infection should not be admitted to the practice and they should be invited to contact their physician in order to better assess and monitor their clinical condition and be referred to the emergency department if they suffer from a dental emergency. Patients that have been diagnosed as positive to the Coronavirus and still have not been confirmed as negative should be treated as high-risk patients.

According to our suggestions, it is imperative to postpone appointments if possible, if there are some signs that may actually be indicative of Coronavirus.

In this case, the practitioner has to provide some temporary treatment, as we defined in a previously published article,33 to maintain a healthy eating plan, which is paramount for global health.34,35

The literature is quite scarce on this subject, but based on this evidence, we think that it is imperative to change the way dentistry is conducted from now on and that our suggestions could make a serious effort in protecting dentists, hygienist, assistants, and their patients.

Authors’ contributions

PCP designed the article; PCP and ER wrote and reviewed the article; PFM, FGG, and AD supervised and reviewed the article. FG-G and AD contributed equally to this work.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

FUNDING

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Pier Carmine Passarelli https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6416-8131

References

- 1.Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, Liang W, Ou C, He J, Liu L, Shan H, Lei C, Hui DSC, Du B, Li L, Zeng G, Yuen K-Y, Chen R, Tang C, Wang T, Chen P, Xiang J, Li S, Wang J, Liang Z, Peng Y, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu Y, Peng P, Wang J, Liu J, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng Z, Qiu S, Luo J, Ye C, Zhu S, Zhong N. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Passarelli PC, Lopez MA, Bonaviri GNM, Garcia-Godoy F, D’Addona A. Taste and smell as chemosensory dysfunction in COVID-19 infection. Am J Dent 2020;33:In Press [PubMed]

- 3.Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, Zhan C, Chen C, Lv W, Tao Q, Sun Z, Xia L. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology 2020;200642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L, Wang Y, Ye D, Liu Q. A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) based on current evidence. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020;105948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simonnet A, Chetboun M, Poissy J, Raverdy V, Noulette J, Duhamel A, Labreuche J, Mathieu D, Pattou F, Jourdain M. Lille intensive care COVID-19 and obesity study group. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020; doi: 10.1002/oby.22831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S, Huang H, Zhang L, Zhou X, Du C, Zhang Y, Song J, Wang S, Chao Y, Yang Z, Xu J, Zhou X, Chen D, Xiong W, Xu L, Zhou F, Jiang J, Bai C, Zheng J, Song Y. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med 2020; doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao J, Tian Z, Yang X. Breakthrough: chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. Biosci Trends 2020; 14:72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Search of Interventional Studies | Covid-19 – results by topic, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results/browse?type=Intr&cond=Covid-19&brwse=cond_alpha_all (accessed 3 May 2020).

- 9.Gilead and Moderna lead on coronavirus treatments. Chem Eng News, https://cen.acs.org/pharmaceuticals/vaccines/Gilead-Moderna-lead-coronavirus-treatments/98/web/2020/02 (accessed 3 May 2020).

- 10.Jogalekar MP, Veerabathini A, Gangadaran P. Novel 2019 coronavirus: genome structure, clinical trials, and outstanding questions. Exp Biol Med 2020;153537022092054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Search of Hydroxychloroquine | Recruiting, not yet recruiting, active, not recruiting, enrolling by invitation studies | Covid-19 – List Results, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=hydroxychloroquine&cond=Covid-19&recrs=b&recrs=a&recrs=f&recrs=d&age_v=&gndr=&type=&rslt=&Search=Apply (accessed 3 May 2020).

- 12.Principi N, Esposito S. Chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine for prophylaxis of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30296-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu C, Liu X, Jia Z. 2019-nCoV transmission through the ocular surface must not be ignored. The Lancet 2020; 395:e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.EpiCentro: Sorveglianza integrata COVID-19: i principali dati nazionali, https://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/sars-cov-2-sorveglianza-dati (accessed 3 April 2020).

- 15.Spagnuolo G, De Vito D, Rengo S, Tatullo M. COVID-19 outbreak: an overview on dentistry. IJERPH 2020; 17:2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gamio L. The workers who face the greatest coronavirus risk. The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/03/15/business/economy/coronavirus-worker-risk.html (2020, accessed 9 April 2020).

- 17.van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med 2020; doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang L, Yan Y, Wang L. Coronavirus disease 2019. Coronaviruses and blood safety. Transfus Med Rev 2020; doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2020.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang D, Xu H, Rebaza A, Sharma L, Cruz C. Protecting health-care workers from subclinical coronavirus infection. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8:e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai THT, Tang EWH, Chau SKY, Fung KSC, Li KKW. Stepping up infection control measures in ophthalmology during the novel coronavirus outbreak: an experience from Hong Kong. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2020; 258:1049–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subhash SS, Baracco G, Miller SL, Eagan A, Radonovich LJ. Estimation of needed isolation capacity for an airborne influenza pandemic. Health Secur 2016; 14:258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ASTM Standards & COVID-19, https://www.astm.org/COVID-19/ (accessed 10 April 2020).

- 23.Ma Q-X, Shan H, Zhang H-L, Li G-M, Yang R-M, Chen J-M. Potential utilities of mask-wearing and instant hand hygiene for fighting SARS-CoV-2. J Med Virol 2020. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Romano MR, Montericcio A, Montalbano C, Raimondi R, Allegrini D, Ricciardelli G, Angi M, Pagano L, Romano V. Facing COVID-19 in ophthalmology department. Curr Eye Res 2020; doi: 10.1080/02713683.2020.1752737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng X, Xu X, Li Y, Cheng L, Zhou X, Ren B. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci 2020;12:9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.ECDC. Personal protective equipment (PPE) needs in healthcare settings for the care of patients with suspected or confirmed novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/personal-protective-equipment-ppe-needs-healthcare-settings-care-patients (2020, accessed 11 April 2020).

- 27.Samaranayake LP, Reid J, Evans D. The efficacy of rubber dam isolation in reducing atmospheric bacterial contamination. ASDC J Dent Child 1989; 56:442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solderer A, Kaufmann M, Hofer D, Wiedemeier D, Attin T, Schmidlin PR. Efficacy of chlorhexidine rinses after periodontal or implant surgery: a systematic review. Clin Oral Investig 2019; 23:21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koeman M, Ven Ajam van der Hak E, Joore HCA, Kaasjager K, Smet AGA, de Ramsay G, Dormans TPJ, Aarts Lphj Bel EE, de Hustinx WNM, Tweel I, van der Hoepelman AM, Bonten M. Oral decontamination with chlorhexidine reduces the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173:1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eggers M, Koburger-Janssen T, Eickmann M, Zorn J. In vitro bactericidal and virucidal efficacy of Povidone-Iodine gargle/mouthwash against respiratory and oral tract pathogens. Infect Dis Ther 2018; 7:249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eggers M. Infectious disease management and control with povidone iodine. Infect Dis Ther 2019; 8:581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ECDC. Disinfection of environments in healthcare and non-healthcare settings potentially contaminated with SARS-CoV-2 https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/disinfection-environments-covid-19 (2020, accessed 11 April 2020).

- 33.Passarelli PC, Passarelli G, Charitos IA, Rella E, Santacroce L, D’Addona A. COVID-19 and oral diseases: how can we manage hospitalized and quarantined patients while reducing risks? Electron J Gen Med 2020; 17:em238 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Azzolino D, Passarelli PC, De Angelis P, Piccirillo GB, D’Addona A, Cesari M. Poor oral health as a determinant of malnutrition and sarcopenia. Nutrients 2019;11:2898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bollero P, Passarelli PC, D’Addona A, Pasquantonio G, Mancini M, Condò R, Cerroni L. Oral management of adult patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2018; 22:876–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]