Abstract

Objectives. To compare the health and health care utilization of persons on and not on probation nationally.

Methods. Using the National Survey of Drug Use and Health, a population-based sample of US adults, we compared physical, mental, and substance use disorders and the use of health services of persons (aged 18–49 years) on and not on probation using logistic regression models controlling for age, race/ethnicity, gender, poverty, and insurance status.

Results. Those on probation were more likely to have a physical condition (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.2, 1.4), mental illness (AOR = 2.4; 95% CI = 2.1, 2.8), or substance use disorder (AOR = 4.2; 95% CI = 3.8, 4.5). They were less likely to attend an outpatient visit (AOR = 0.8; 95% CI = 0.7, 0.9) but more likely to have an emergency department visit (AOR = 1.8; 95% CI = 1.6, 2.0) or hospitalization (AOR = 1.7; 95% CI = 1.5, 1.9).

Conclusions. Persons on probation have an increased burden of disease and receive less outpatient care but more acute services than persons not on probation.

Public Health Implications. Efforts to address the health needs of those with criminal justice involvement should include those on probation.

The United States incarcerates more people than any other country, and many adverse health consequences are associated with incarceration.1,2 Moreover, the correctional system affects many more people than those who are incarcerated in prisons and jails. The majority of persons under correctional control are managed outside of the carceral setting, including 3.6 million who are on probation,3 a number that is expected to increase as criminal justice policies increasingly emphasize alternatives to incarceration.4

Probation, a court-ordered period of community supervision in lieu of incarceration, may come in the form of a sentence served entirely in the community or a sentence involving a shortened period of incarceration followed by community supervision.5 The original intent of probation was to provide an alternative to incarceration that focused on community-based rehabilitation, which could include linkage to care for those with health needs. However, given the growth of probational supervision during the past 4 decades and the lack of concomitant investments in rehabilitation or health services for those under supervision, many criminal justice researchers argue that probation has been largely unsuccessful at providing rehabilitative services.4,6

Studies suggest that the greatest health risks of justice involvement occur in the community rather than in the carceral setting,7 yet scant previous research has examined the health or health care of people on probation. One analysis found that persons on probation are at higher risk of death compared with both the general population and those currently incarcerated,8 although the comparisons were not adjusted for underlying health conditions. A study that surveyed adult correctional agencies and administrators nationally indicated that persons on probation often failed to receive needed medical care for chronic conditions, substance use, and mental illness, or infectious disease detection.9 In addition, other research has found high emergency department (ED) utilization and hospitalization rates among those recently arrested or on probation or parole, suggesting increased acute care needs.10

Decreased access to health care may contribute to poor health outcomes of persons under probational supervision. While incarcerated persons are constitutionally guaranteed health care, no such guarantee applies to those on probation. Some states, particularly those that have rejected the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion, limit access to publicly funded health insurance among those with a felony record.11 Moreover, persons with a criminal record often face barriers to employment, effectively excluding them from private health insurance coverage.12

However, no previous study has examined the health profile or health care utilization patterns of persons under probational supervision. Using nationally representative, cross-sectional data, we sought to address this knowledge gap. We hypothesized that, relative to the general population, persons on probation would demonstrate a greater burden of physical disease, mental illness, and substance use disorders, and would utilize less outpatient services but more acute hospital-based services.

METHODS

We analyzed the 4 most recent years of data (2015–2018) from the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), a cross-sectional, nationally representative survey sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The NSDUH surveys noninstitutionalized individuals via in-person interviews with most questions anonymously entered by computer entry to assess the prevalence of substance use and mental health conditions in the United States.13 The annual response rates ranged from 66% to 69%. We restricted our analysis to adults aged 18 to 49 years (n = 136 524) because the vast majority (90%) of those on probation are aged younger than 50 years.

Identifying Persons on Probation

We categorized respondents as “on probation” on the basis of the following question: “Were you on probation at any time in the past 12 months?” A small proportion (< 1%) of those not on probation reported being on parole (a period of conditional supervised release at the end of a prison sentence)5; we excluded them from the analysis. We refer to persons who were not on probation or parole as the “general population.”

Outcomes

We first examined the prevalence of a range of physical conditions based on responses to questions asking if the respondents had ever been told by a doctor that they had the relevant condition. The physical conditions included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, diabetes, hypertension, a heart condition, obesity (body mass index > 30.0), cirrhosis, hepatitis B or C, HIV, a cancer diagnosis, kidney disease, and a past-year diagnosis of a sexually transmitted infection. We also created binary variables indicating whether the individual had any of the physical conditions, 2 or more of the conditions, or self-reported fair or poor health status (vs good, very good, or excellent health).

We identified persons with any mental illness or serious mental illness based on a previously described and extensively used NSDUH-specific prediction model that uses responses to survey questions about mental health symptoms.14 That model also identified any episode of major depressive disorder within the past year based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), criteria. Multiple survey questions assess substance use, which the NSDUH model employs to generate variables for alcohol use disorder only, illicit drug use disorder only, or either alcohol or illicit drug use disorder, as determined from standardized diagnostic assessments using DSM-IV criteria for substance abuse or dependence.15 Illicit substances included marijuana, cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, methamphetamine, pain relievers, tranquilizers, stimulants, or sedatives. We defined current smoking as self-reported past-month daily cigarette use.

In addition, we examined self-reported health care utilization, including having 1 or more outpatient medical visits in the past 12 months, 1 or more ED visits in the past 12 months, or 1 or more nights of hospitalizations in the past 12 months.

Finally, we examined self-reported unmet need for mental health and substance use treatment. Unmet need for mental health treatment was defined as “feeling a perceived need for mental health treatment/counseling that was not received” within the past year. Unmet need for substance use treatment was defined as “needing illicit drug or alcohol treatment in the past year, but not receiving illicit drug or alcohol treatment at a specialty facility.”

Covariates

We included the following covariates in our models comparing persons on probation with the general population: age category (18–25, 26–34, or 35–49 years), race/ethnicity (White [non-Hispanic], Black [non-Hispanic], Hispanic [any race], Native American, or other [Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Asian, more than 1 race]), gender, poverty level (as determined by the US Census Bureau; income < poverty level, 100%–200% of poverty level, or > 200% of poverty level), and health insurance status (uninsured vs any coverage). In models assessing health care utilization, we also controlled for urbanicity of the county of residence based on the National Center for Health Statistics’ 2013 Urban–Rural Classification Scheme (large metro, small metro, nonmetro [or “rural”]).16

Statistical Analysis

We first compared sociodemographic characteristics of persons on probation to those of the general population by using the Pearson χ2 test. To compare the burdens of physical conditions, mental illness, and substance use disorders in the 2 populations, we first calculated the proportion in each group reporting each condition and the unadjusted odds ratio of having a condition among those on probation compared with the general population. We then estimated the adjusted odds ratios (AORs) for each condition by using logistic regression models that controlled for age, gender, poverty level, and health insurance status.

To understand the racial/ethnic distribution of health in the population on probation, we stratified by race/ethnicity and calculated unadjusted proportions of respondents in each stratum reporting serious mental illness, any mental illness, substance use disorder, and 1 or more physical conditions.

To examine differences in health care utilization, we first calculated the unadjusted proportion of those on probation (and other respondents) who reported having received each type of care. We then estimated the adjusted odds of having had an outpatient visit, an ED visit, or a hospitalization in the past year in 2 sequential models. In model 1 we controlled for age, gender, race/ethnicity, poverty level, and county of residence. In model 2, we additionally controlled for insurance status. Substantial changes in AORs between model 1 and model 2 would imply that health insurance is independently associated with differences in utilization rates between people on probation versus the general population.

To examine the differences in perceived unmet health needs between the general population and those on probation, we calculated the unadjusted proportion of respondents in each group who reported an unmet mental health or substance use treatment need. We then estimated the AORs of having an unmet health need in the past year controlling for age, race/ethnicity, gender, poverty level, insurance status, and county of residence. We conducted these analyses only among those with any mental illness (for perceived unmet mental health treatment need) or those with any substance use disorder (for perceived unmet substance use treatment need).

We conducted all analyses with Stata version 15.1 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX) and used weights provided by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration that account for the NSDUH’s complex survey design and allow extrapolation for the US population as a whole. We considered 2-sided P values of less than .05 to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Our unweighted sample consisted of 3685 adults aged 18 to 49 years on probation during the previous 12 months and 132 839 other adult respondents, representing 3 313 501 (2.5%) and 131 147 555 (97.5%) US adults, respectively. We found substantial demographic differences between the 2 groups (Table 1). Nearly one third (31.8%) of those on probation were female (vs 51.0% in the general population), which is similar to data presented by the Bureau of Justice Statistics.3 Persons on probation were younger, more likely to be Black (18.9% vs 12.9%) or Native American (1.8% vs 0.6%), and more likely to be covered by Medicaid (29.7% vs 15.1%) or uninsured (25.9% vs 14.0%) than the general population. Those on probation also reported lower educational attainment, rates of current employment, and income.

TABLE 1—

Demographic Characteristics of Study Population According to Probation Status: United States, 2015–2018

| Under Probation (n = 3685), Weighted No. (%) | General Populationa (n = 132 839), Weighted No. (%) | |

| Total population | 3 313 501 (2.5) | 131 147 555 (97.5) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 2 260 232 (68.2) | 64 277 227 (49.0) |

| Female | 1 053 269 (31.8) | 66 870 328 (51.0) |

| Age group, y | ||

| 18–25 | 1 036 109 (31.3) | 33 416 607 (25.5) |

| 26–34 | 1 115 776 (33.7) | 38 058 988 (29.0) |

| 35–49 | 1 161 617 (35.1) | 59 671 960 (45.5) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 1 759 714 (53.1) | 74 861 129 (57.1) |

| Black | 625 721 (18.9) | 16 853 650 (12.9) |

| Hispanic | 697 826 (21.1) | 26 724 626 (20.4) |

| Native American | 60 751 (1.8) | 749 540 (0.6) |

| Other | 169 488 (5.1) | 15 944 814 (9.1) |

| Education level | ||

| < high school | 735 752 (22.2) | 15 623 644 (11.9) |

| High school | 1 202 798 (36.3) | 30 399 237 (23.1) |

| > high school | 1 374 951 (41.5) | 85 184 675 (65.0) |

| Currently employed | ||

| Yes | 2 520 764 (57.6) | 121 302 125 (70.0) |

| No | 1 859 209 (42.5) | 52 035 710 (30.0) |

| Poverty level | ||

| < PL | 1 039 372 (31.5) | 22 834 921 (17.5) |

| 100%–200% PL | 902 142 (27.3) | 26 846 295 (20.6) |

| > 200% PL | 1 360 582 (41.2) | 80 747 299 (61.9) |

| Health insurance | ||

| Private | 1 225 341 (37.0) | 85 176 060 (64.3) |

| Medicaid | 984 186 (29.7) | 19 825 141 (15.1) |

| Medicare | 37 806 (1.1) | 757 558 (0.6) |

| Veteran’s health | 77 739 (2.4) | 2 693 912 (2.1) |

| Other/unspecified | 129 050 (3.9) | 4 404 914 (3.36) |

| Uninsured | 859 379 (25.9) | 18 289 972 (14.0) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 490 815 (20.3) | 43 519 755 (44.1) |

| Widowed | 19 589 (0.8) | 561 500 (0.6) |

| Divorced | 391 038 (16.2) | 9 513 568 (9.7) |

| Never married | 1 517 122 (62.7) | 45 034 715 (45.7) |

| County status | ||

| Large metro | 1 656 983 (50.0) | 76 961 954 (58.7) |

| Small metro | 1 073 142 (32.4) | 38 060 912 (29.0) |

| Rural | 583 376 (17.6) | 16 124 689 (12.3) |

Note. PL = poverty line. All demographics covariates are statistically significant with P < .001.

Persons living in the community and not under probation or parole.

Persons on probation had a higher burden of physical conditions, mental illnesses, and substance use disorders than did the general population in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses (Table 2). Those on probation were more likely to report any physical condition (AOR = 1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.2, 1.4), to suffer 2 or more physical conditions (AOR = 1.5; 95% CI = 1.3, 1.7), and to report fair or poor health (AOR = 1.7; 95% CI = 1.4, 2.2) compared with the general population. Being on probation was also associated with reporting several specific physical conditions, including COPD, a heart condition, hepatitis B or C, HIV, kidney disease, and past-year sexually transmitted infection. Persons on probation were more likely to have any mental illness (AOR = 2.0; 95% CI = 1.8, 2.2), including a serious or moderate mental illness or a recent episode of major depression. Finally, those on probation were much more likely to meet criteria for any substance use disorder (AOR = 4.2; 95% CI = 3.8, 4.5), including illicit drug use disorder, alcohol use disorder, or current smoking.

TABLE 2—

Prevalence Rates of Physical Conditions, Mental Illness, and Substance Use Disorders Among Persons Aged 18–49 Years According to Probation Status: United States, 2015–2018

| Under Probation, % | General Population, % | AORa (95% CI) | |

| Physical condition, ever | |||

| Any physical condition | 30.6 | 26.6 | 1.3 (1.2, 1.4) |

| ≥ 2 physical conditions | 10.1 | 7.0 | 1.5 (1.3, 1.8) |

| Fair/poor health | 16.2 | 9.1 | 1.6 (1.4, 1.7) |

| COPD | 3.3 | 1.8 | 1.7 (1.4, 2.2) |

| Asthma | 10.4 | 10.7 | 1.0 (0.9, 1.2) |

| Diabetes | 5.0 | 4.5 | 1.2 (0.9, 1.4) |

| Hypertension | 7.1 | 8.4 | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) |

| Heart condition | 5.0 | 3.7 | 1.4 (1.1, 1.9) |

| Obesity | 32.0 | 33.6 | 0.9 (0.8, 1.0) |

| Cirrhosis | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.3 (0.1, 1.5) |

| Hepatitis B or C | 3.0 | 0.6 | 4.9 (3.7, 6.5) |

| HIV | 0.7 | 0.2 | 2.5 (1.3, 4.7) |

| Cancer diagnosis | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.2 (0.8, 1.8) |

| Kidney disease | 1.3 | 0.8 | 1.8 (1.2, 2.6) |

| STI, past y | 5.9 | 2.5 | 2.5 (2.1, 3.1) |

| Mental illness, past y | |||

| Serious/moderate mental illnessb | 11.9 | 5.6 | 2.4 (2.1, 2.8) |

| Any mental illnessb | 34.3 | 21.9 | 2.0 (1.8, 2.2) |

| Major depression | 13.9 | 8.6 | 1.8 (1.6, 2.1) |

| Substance use disorders, past y | |||

| Any substance use disorderc | 35.1 | 10.3 | 4.2 (3.8, 4.5) |

| Illicit drug use disorderc | 20.0 | 3.9 | 5.1 (4.6, 5.6) |

| Alcohol use disorderc | 21.8 | 7.7 | 3.0 (2.7, 3.4) |

| Current smoking | 37.4 | 12.3 | 3.8 (3.3, 4.3) |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; STI = sexually transmitted infection.

Adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, poverty level, and insurance.

Presence of mental illness in National Survey of Drug Use and Health is based on statistical prediction model.

Substance use disorder in National Survey of Drug Use and Health defined using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, criteria for substance dependence or abuse.

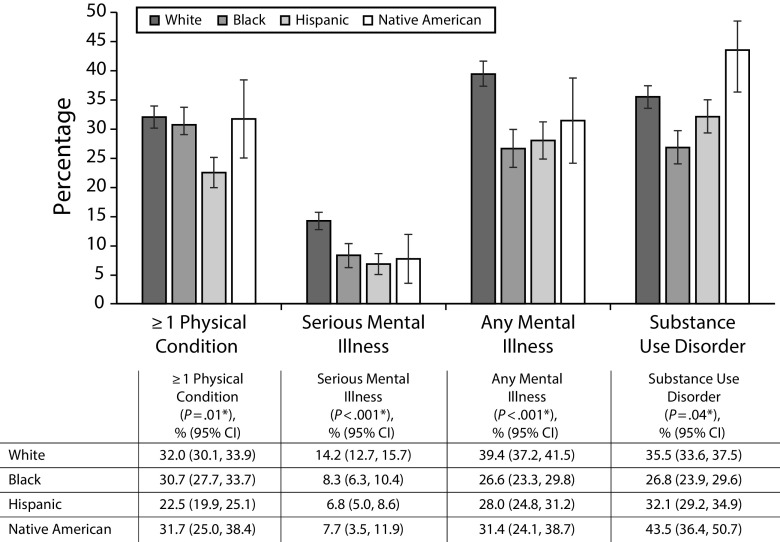

Figure 1 displays the distribution of physical conditions, mental illness, and substance use disorder among persons on probation stratified by race. There were no differences in the proportion reporting any physical condition between White, Black, and Native American respondents; Hispanic respondents were less likely to have a physical condition than were respondents of other races/ethnicities. White respondents on probation were more likely to have a serious or any mental illness compared with Black, Hispanic, or Native American respondents, and were more likely to have any substance use disorder compared with Black respondents.

FIGURE 1—

Proportions of Respondents on Probation With Physical Conditions, Mental Health Disorders, and Substance Use Disorders, by Race/Ethnicity: United States, 2015–2018

Note. CI = confidence interval.

*Statistical significance level for χ2 test.

Persons on probation compared with the general population had lower odds of having had an outpatient visit in the previous 12 months (AOR = 0.8; 95% CI = 0.7, 0.9) but higher odds of having had an ED visit (AOR = 1.8; 95% CI = 1.6, 2.0) or inpatient hospitalization (AOR = 1.7; 95% CI = 1.5, 1.9). The association between being on probation and lacking an outpatient visit was stronger among respondents with any or multiple chronic conditions than among those with no chronic condition. Comparable associations of utilization with probation status were present among persons with any mental illness (outpatient visit: AOR = 0.8; 95% CI = 0.7, 0.9; ED visit: AOR = 1.8; 95% CI = 1.6, 2.0; hospitalization: AOR = 1.7; 95% CI = 1.3, 2.1) or any substance use disorder (outpatient visit: AOR = 0.8; 95% CI = 0.6, 1.0; ED visit: AOR = 1.6; 95% CI = 1.3, 1.8; hospitalization: AOR = 1.7; 95% CI = 1.3, 2.2). In models that additionally controlled for insurance status, point estimates for outpatient utilization for most groups were minimally attenuated, but the patterns of statistical significance persisted overall (Table 3). The additional adjustment for insurance status had no impact on models of ED visits or hospitalizations for any group.

TABLE 3—

Proportion of Participants With Outpatient, Emergency Department, and Hospital Utilization by Probation Status for Those Aged 18–49 Years: United States, 2015–2018

| Outpatient Visit |

ED Visit |

Hospitalized ≥ 1 Night |

||||||||||

| PP, % | GP, % | Model 1,a AOR (95% CI) | Model 2,b AOR (95% CI) | PP, % | GP, % | Model 1,a AOR (95% CI) | Model 2,b AOR (95% CI) | PP, % | GP, % | Model 1,a AOR (95% CI) | Model 2,b AOR (95% CI) | |

| Total population | 65.4 | 75.4 | 0.8 (0.7, 0.9) | 0.9 (0.8, 0.9) | 40.5 | 25.7 | 1.8 (1.6, 2.0) | 1.8 (1.6, 2.0) | 11.4 | 7.5 | 1.7 (1.5, 1.9) | 1.7 (1.5, 2.0) |

| Any physical condition | 78.0 | 86.8 | 0.7 (0.5, 0.8) | 0.8 (0.6, 0.9) | 51.9 | 34.3 | 1.7 (1.5, 2.1) | 1.8 (1.5, 2.1) | 17.9 | 11.7 | 1.5 (1.2, 1.9) | 1.6 (1.3, 1.9) |

| ≥ 2 physical conditions | 83.7 | 91.0 | 0.6 (0.4, 0.9) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.1) | 64.0 | 44.0 | 1.8 (1.3, 2.5) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.6) | 27.4 | 16.8 | 1.6 (1.2, 2.2) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.3) |

| Any mental Illness | 75.6 | 83.4 | 0.8 (0.7, 0.9) | 0.8 (0.7, 0.9) | 52.0 | 35.4 | 1.8 (1.6, 2.0) | 1.8 (1.6, 2.0) | 18.0 | 11.0 | 1.7 (1.3, 2.1) | 1.7 (1.4, 2.1) |

| Serious mental illness | 82.1 | 85.8 | 0.9 (0.6, 1.2) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.4) | 58.3 | 43.7 | 1.7 (1.3, 2.2) | 1.7 (1.3, 2.2) | 23.2 | 15.5 | 1.5 (1.1, 2.1) | 1.6 (1.1, 2.2) |

| Past year any substance use disorder | 67.5 | 75.4 | 0.8 (0.6, 1.0) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) | 46.0 | 33.0 | 1.6 (1.3, 1.8) | 1.6 (1.3, 1.9) | 14.7 | 8.4 | 1.7 (1.3, 2.2) | 1.7 (1.3, 2.3) |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; GP = general population; PP = probation population.

Adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, gender, poverty level, and county status.

Adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, gender, poverty level, county status, and insurance.

The odds of an unmet mental health need (among those with any mental illness) were significantly higher for those on probation than in the general population (AOR = 1.3; 95% CI = 1.1, 1.6; Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). However, among those with a substance use disorder, the odds of not receiving treatment of a substance use disorder were significantly lower for those on probation compared with the general population (AOR = 0.1; 95% CI = 0.1, 0.2), although the absolute proportion of those not receiving treatment was high in both groups (70% probation; 95% general population).

DISCUSSION

In this nationally representative study of the health and health care utilization of people on probation, we found elevated rates of a wide array of physical conditions, mental illnesses, and substance use disorders. The higher prevalence of substance use disorders and related conditions such as hepatitis C and HIV was expected given the criminalization of illicit drug use, as were the adverse physical and mental health outcomes associated with alcohol use disorder.17,18 However, it is unclear why those on probation reported higher rates of kidney disease and heart conditions. It is plausible, although unproven, that the association between probation status and these conditions arises from the stress of criminal justice involvement—or unmeasured socioeconomic factors correlated with justice involvement—that may accelerate atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction.19,20 Not surprisingly, we also found higher rates of mental health disorders among those on probation compared with those in the general population. Although we could not determine the direction of causality, 2 longitudinal analyses have suggested that criminal justice involvement may cause a deterioration in mental health.21,22 Consistent with past studies, we found that White persons on probation are more likely than persons of color on probation to have substance use or mental health disorders.23

Previous studies suggest that poor access to both medical care and addiction treatment are associated with high mortality rates among persons recently released from incarceration.24 Our finding that individuals on probation had high rates of physical conditions, substance use disorders, and unmet mental health needs, but reduced use of outpatient care may help explain the recently published finding of increased mortality of those on probation compared with the general population.8

Our findings also suggest that persons on probation face particularly severe or unique access barriers. Their greater use of ED and inpatient services may reflect inadequate access to outpatient care. A previous study found that, among people with a history of incarceration, expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act was associated with increased outpatient utilization and greater likelihood of reporting a usual source of care.25 However, the findings of our tiered logistic regression models that health insurance only minimally attenuated the association between being on probation and outpatient health care utilization suggest that factors beyond insurance coverage likely play important roles in producing differentials in utilization. Such factors might include structural barriers including stigma and discrimination, which may obstruct access to ambulatory care among those with justice involvement.26 Future research should focus on understanding why people on probation, particularly those who have insurance, may face barriers to accessing and utilizing outpatient care.

Unmet mental health treatment needs were higher among those on probation. Previous research suggests that improving insurance coverage among the justice involved alone may not be sufficient to improve mental health treatment utilization or reduce unmet mental health needs.27 While use of needed treatment of substance use disorders was actually higher among those on probation, possibly because of court-mandated treatment, the absolute level of unmet need for treatment was still high, at 70%. In addition, our findings do not address the quality of substance use disorder treatment received by those on probation, which previous research has shown to be lacking. Those on probation—especially those with opioid use disorder—often fail to receive evidence-based treatment because court-ordered substance treatment programs rarely offer access to pharmacotherapy, such as buprenorphine and methadone,28 which, in criminal justice settings, have been shown to reduce risk of overdose death, increase the time to relapse, and possibly decrease recidivism.29 Our findings suggest significant room for improvement in the treatment of mental illness and substance use among those on probation, which could improve health and reduce criminal justice involvement.

The COVID-19 epidemic has expedited release of incarcerated persons and increased the number of individuals placed on probation in lieu of incarceration to minimize the population of those susceptible and exposed to COVID-19 behind bars. Many of those on probation will live in communities with disproportionately high rates of COVID-19 infection.30 Furthermore, our findings suggest that those on probation, with higher rates of physical conditions, mental illness, and substance use disorders compared with the general population, may face increased barriers to initiating and maintaining outpatient treatment as most outpatient care has transitioned to telephone and video visits. To mitigate risk, individuals on probation must have continuing access to health insurance coverage, appropriate medications, and telephone access to stay connected to care.31 Furthermore, communication with probation officers should be minimized or limited to telephone visits to diminish transmission of COVID-19 on public transportation and in probation offices.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, because the data were observational, we cannot establish causation. Second, the survey data are subject to potential selection bias, and unmeasured confounders (especially adverse childhood experiences) are likely. Nonetheless, the findings suggest substantially worse health and access to outpatient care among those on probation, information that could help clinicians and public health officials better meet the health needs of this population. Third, all data are self-reported and not verified with clinical or administrative data. Finally, exposure to probation was determined on the basis of self-report, an ascertainment method that might cause underreporting. However, studies suggest that self-reported exposure to justice involvement is as accurate as administrative data.32 Moreover, our estimate of the total number of persons on probation closely mirrors the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ administrative data,5 suggesting that respondents provided reasonably accurate information on their probation status.

Public Health Implications

Our findings highlight the high burden of disease and poor access to care among persons on probation, a large but poorly studied population of young to middle-aged adults. Previous research on the health effects of incarceration has largely omitted this group. This omission may reflect the lack of uniform data on this population, heterogeneous implementation of probation programs across states, or researchers’ beliefs that probation is a “privilege,” especially when compared with incarceration.33 Our findings underscore the need for better empirical data on the health needs of the vast probation population, including the special needs of vulnerable populations such as sexual minorities and immigrants, and suggest that better access to care is imperative for those on probation.

The creation of a more uniform system to understand the health of persons on probation would help elucidate their care needs. Ensuring access to health insurance for all persons and tasking probation officers with linking those on probation to care resources may improve access to outpatient services and reduce ED visits and hospitalizations. Models of primary care engagement for persons following release from incarceration34,35 indicate that patient-centered interventions can increase outpatient engagement among the recently incarcerated. Further expansion of these models to include those on probation should be explored.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

L. Hawks received funding support from an Institutional National Research Service Award from T32HP32715 and from the Cambridge Health Alliance.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The Cambridge Health Alliance institutional review board deemed this research exempt from review.

Footnotes

See also Puglisis and Shavit, p. 1262.

REFERENCES

- 1.Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA et al. Release from prison—a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):157–165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Boyd JW et al. The health and health care of US prisoners: results of a nationwide survey. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(4):666–672. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.144279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaeble D, Cowhig M. Correctional Populations in the United States, 2016. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phelps MS. Mass probation: toward a more robust theory of state variation in punishment. Punishm Soc. 2017;19(1):53–73. doi: 10.1177/1462474516649174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaeble D. Probation and Parole in the United States, 2016. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schiraldi VN. Too Big to Succeed: The Impact of the Growth of Community Corrections and What Should Be Done About It. New York, NY: Columbia Justice Lab; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spaulding AC, Seals RM, McCallum VA, Perez SD, Brzozowski AK, Steenland NK. Prisoner survival inside and outside of the institution: implications for health-care planning. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(5):479–487. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wildeman C, Goldman AW, Wang EA. Age-standardized mortality of persons on probation, in jail, or in state prison and the general population, 2001–2012. Public Health Rep. 2019;134(6):660–666. doi: 10.1177/0033354919879732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cropsey KL, Binswanger IA, Clark CB, Taxman FS. The unmet medical needs of correctional populations in the United States. J Natl Med Assoc. 2012;104(11-12):487–492. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30214-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank JW, Linder JA, Becker WC, Fiellin DA, Wang EA. Increased hospital and emergency department utilization by individuals with recent criminal justice involvement: results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(9):1226–1233. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2877-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKee C, Somers S, Artiga S, Gates A. State Medicaid eligibility policies for individuals moving into and out of incarceration. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2015. Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/state-medicaid-eligibility-policies-for-individuals-moving-into-and-out-of-incarceration. Accessed December 8, 2019.

- 12.Solomon AL. In search of a job: Criminal records as barriers to employment. National Institute of Justice Journal. 2012;270. Available at: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/238488.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2020.

- 13.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health. About the survey. Available at: https://nsduhweb.rti.org/respweb/about_nsduh.html. Accessed November 26, 2019.

- 14.Aldworth J, Gulledge K, Warren L, Hedden S, Bose J. National Survey on Drug Use and Health: alternative statistical models to predict mental illness. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasin D, Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes K, Ogburn E. Substance use disorders: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM‐IV) and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD‐10) Addiction. 2006;101(suppl 1):59–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NCHS Urban–Rural Classification Scheme for Counties. 2013. Vital and Health Statistics. 2014;2(116). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_166.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2020.

- 17.Bronson J, Stroop J, Zimmer S, Berzofsky M. Drug use, dependence, and abuse among state prisoners and jail inmates, 2007–2009. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bronson J, Berzofsky M. Indicators of mental health problems reported by prisoners and jail inmates, 2011–12. Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2017. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/imhprpji1112.pdf. Accessed December 9, 2019.

- 19.Yao BC, Meng L, Hao M, Zhang Y, Gong T, Guo Z. Chronic stress: a critical risk factor for atherosclerosis. J Int Med Res. 2019;47(4):1429–1440. doi: 10.1177/0300060519826820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fobian AD, Froelich M, Sellers A, Cropsey K, Redmond N. Assessment of cardiovascular health among community-dwelling men with incarceration history. J Urban Health. 2018;95(4):556–563. doi: 10.1007/s11524-018-0289-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugie NF, Turney K. Beyond incarceration: criminal justice contact and mental health. Am Sociol Rev. 2017;82(4):719–743. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernandes AD. How far up the river? Criminal justice contact and health outcomes. Soc Currents. 2020;7(1):29–45. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winkelman TN, Frank JW, Binswanger IA, Pinals DA. Health conditions and racial differences among justice-involved adolescents, 2009 to 2014. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(7):723–731. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Mueller SR, Stern MF. Mortality after prison release: opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(9):592–600. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-9-201311050-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winkelman TN, Choi H, Davis MM. The Affordable Care Act, insurance coverage, and health care utilization of previously incarcerated young men: 2008–2015. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(5):807–811. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Redmond N, Aminawung JA, Morse DS, Zaller N, Shavit S, Wang EA. Perceived discrimination based on criminal record in healthcare settings and self-reported health status among formerly incarcerated individuals. J Urban Health. 2020;97(1):105–111. doi: 10.1007/s11524-019-00382-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howell BA, Wang EA, Winkelman TN. Mental health treatment among individuals involved in the criminal justice system after implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(9):765–771. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201800559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krawczyk N, Picher CE, Feder KA, Saloner B. Only one in twenty justice-referred adults in specialty treatment for opioid use receive methadone or buprenorphine. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(12):2046–2053. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moore KE, Roberts W, Reid HH, Smith KM, Oberleitner LM, McKee SA. Effectiveness of medication assisted treatment for opioid use in prison and jail settings: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;99:32–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson A, Buford T. Early data shows African Americans have contracted and died of coronavirus at an alarming rate. Propublica. April 3, 2020. Available at: https://www.propublica.org/article/early-data-shows-african-americans-have-contracted-and-died-of-coronavirus-at-an-alarming-rate. Accessed April 17, 2020.

- 31.Howell BA, Ramirez Batlle H, Ahalt C Protecting decarcerated populations in the era of COVID-19: priorities for emergency discharge planning. Health Affairs Blog. April 13, 2020. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200406.581615/full. Accessed April 15, 2020.

- 32.Wang EA, Long JB, McGinnis KA et al. Measuring exposure to incarceration using the electronic health record. Med Care. 2019;57(suppl 6):S157–S163. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doherty F. Obey all laws and be good: probation and the meaning of recidivism. Georgetown Law J. 2015;104:291–354. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gordon MS, Crable EL, Carswell SB et al. A randomized controlled trial of intensive case management (Project Bridge) for HIV-infected probationers and parolees. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(3):1030–1038. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-2016-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shavit S, Aminawung JA, Birnbaum N et al. Transitions clinic network: challenges and lessons in primary care for people released from prison. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(6):1006–1015. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]