Abstract

Despite the ubiquity of health-related communications via social media, no consensus has emerged on whether this medium, on balance, jeopardizes or promotes public health. During the COVID-19 pandemic, social media has been described as the source of a toxic “infodemic” or a valuable tool for public health. No conceptual model exists for examining the roles that social media can play with respect to population health.

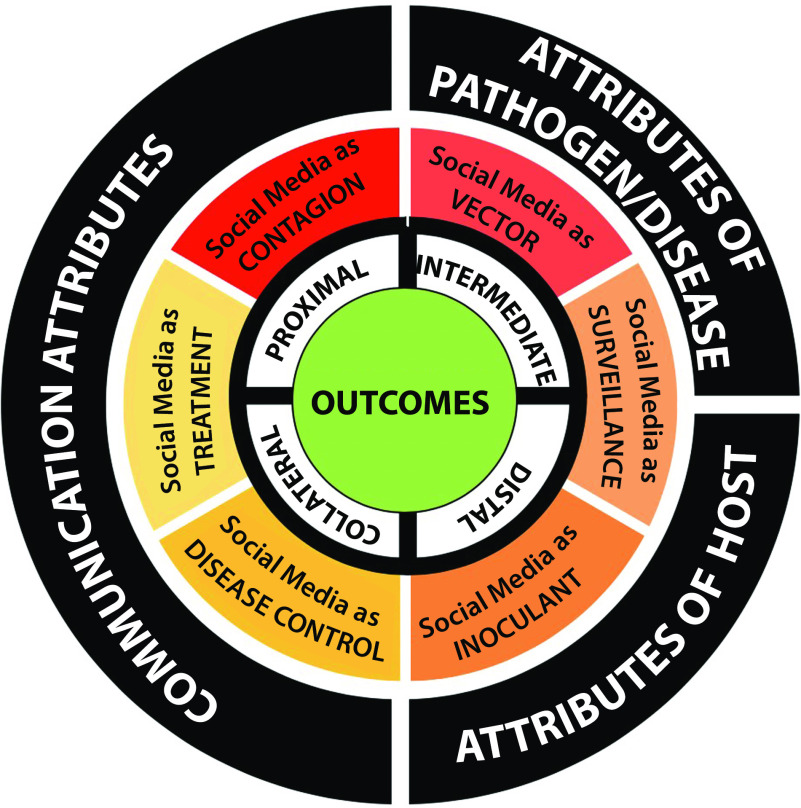

We present a novel framework to guide the investigation and assessment of the effects of social media on public health: the SPHERE (Social media and Public Health Epidemic and REsponse) continuum. This model illustrates the functions of social media across the epidemic–response continuum, ranging across contagion, vector, surveillance, inoculant, disease control, and treatment.

We also describe attributes of the communications, diseases and pathogens, and hosts that influence whether certain functions dominate over others. Finally, we describe a comprehensive set of outcomes relevant to the evaluation of the effects of social media on the public’s health.

Over the past 25 years, the field of health communication has established itself as central to clinical medicine and public health. In clinical contexts, how patients and clinicians communicate determines a range of health outcomes. In public health contexts, mass communications—whether generated by the private or public sector—influence population health by shaping discourse about exposure risk and disease, influencing the adoption (or nonadoption) of health-promoting social policies, linking people to health services, and providing education and motivation that influence behaviors. These conclusions emerged in an era when communications were predominantly controlled by individuals and entities endowed with the power, money, public trust, or platforms required to drive the conversation.

In the modern era, however, health communications have become more democratized through social media’s interactive functionality and popularity. Social media are means of interactions among people in which individuals create, share, or exchange information and ideas in virtual (online or cloud-based) communities and networks. Three quarters of US adults use social media; of these, three quarters engage at least once daily1 and nearly 50% report that information found via social media affects the way they deal with their health. In China, more than 740 million individuals (> 50% of the population) have social media accounts with which they daily engage,2 and more than 70% of WeChat’s (a Chinese messaging, social media, and mobile payment app) 570 million users report it to be their primary source of health education.3

Despite the ubiquity of health-related content on social media, no consensus has emerged on whether this medium, on balance, jeopardizes or promotes health. During the COVID-19 pandemic, social media has been described by some as the source of a toxic “infodemic” and considered by others as an emerging tool for public health.4 There is little question that social media has the potential to facilitate or undermine public health efforts.5,6 Yet no widely accepted conceptual model exists for examining the roles that social media can play with respect to population health.7,8

HOW SOCIAL MEDIA CAN INFLUENCE PUBLIC HEALTH

To describe the functions that social media can play, we employ the metaphor of an epidemic. This metaphor is both understandable and fitting: communication is the process of passing information and understanding from one person to another, just as communicable diseases can be passed from person to person. It is no coincidence, then, that social media messages that achieve widespread exposure are often described as “having gone viral.” Accordingly, we developed a novel framework to guide the investigation and assessment of social media and public health: the SPHERE (Social media and Public Health Epidemic and REsponse; Figure 1) continuum. This model illustrates potential—and often conflicting—functions of social media across the epidemic–response continuum (Figure 1, middle concentric ring), recognizing that communication itself can contribute to health or disease. We also describe factors that influence which roles social media play based on the contextual attributes in a given circumstance (Figure 1, outer ring) and outcomes relevant to the evaluation of the effects of social media on the health of the public (Figure 1, inner ring).

FIGURE 1—

The SPHERE Continuum Model for How Social Media Influences Public Health

Note. SPHERE = Social media and Public Health Epidemic and REsponse continuum.

Social Media as Contagion

Social media influences attitudes, beliefs, norms, and behaviors4 that can undermine public health. Examples of this include exposure to industry-generated promotional messages related to products that contribute to tobacco and e-cigarette use8 and obesity and type 2 diabetes.9,10 For communicable diseases, the dissemination of misinformation can lead to what World Health Organization (WHO) director general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus recently referred to as an infodemic.11 Such misinformation, in part because of its tendency to spread widely and rapidly, has the potential to lead individuals, subgroups, or communities to institute ineffective, unsafe, costly, or inappropriate protective measures; undermine public trust in more evidence-based public health messages and interventions; and lead to a range of collateral negative consequences12 (see the section “Outcomes of Interest”).

Social Media as Vector

Social media can serve as a medium through which risky behaviors are enabled and associated diseases transmitted. Examples include outbreaks of sexually transmitted infections4 and opiate use. For noncommunicable diseases, social media have been harnessed by industry to deliver targeted content and purchasing opportunities in the online market, increasing the consumption of tobacco and e-cigarette products and junk food8–10 that contribute to cancer, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Social Media as Inoculant

On the other hand, proactive communications—usually generated by public health entities—can effectively prevent or minimize the spread of misinformation and increase public awareness of accurate information.13 More often, such inoculating messages are created and disseminated as a reaction to misinformation. In response to misinformation concerns related to COVID-19, WHO’s risk communication team launched a new information platform called WHO Information Network for Epidemics, which uses social media amplifiers to share tailored information with target groups.11

Social Media for Surveillance

Social media has the potential to enhance real-time surveillance related to incident disease,14 as well as to monitor exposures, including changes in air, soil, and water contaminant levels, and the food and built environments. Advances include so-called citizen science platforms15 and computational linguistics methods that allow the harnessing of big data from social media to identify emerging trends, track behavioral changes, and detect or even predict disease outbreaks.4

Social Media for Disease Control and Mitigation

Social media can disseminate health-promoting information that positively influences health behaviors, such as those that can reduce the spread or impact of a disease by encouraging appropriate preventive measures.4,7,16 Public health entities increasingly recognize that social media can be an effective platform for disseminating messages to the population at large as well as to vulnerable, hard-to-reach subgroups.9 Furthermore, social media can generate public demand for transparency regarding the severity of an outbreak and modes of transmission and can provide a platform for discourse about the balance between protecting health and preserving individual freedoms. Similarly, social media communications can apply pressure and motivate resource allocation in support of outbreak preparedness and a robust public health response. Finally, social media can be an engine for grassroots movements to develop a common cause and narrative to advocate and implement policies that combat public health problems, such as type 2 diabetes and gun violence. These movements often employ countermessaging to hold accountable industries, such as junk food, beverage, and gun manufacturers, that contribute to modern epidemics.17

Social Media as Treatment

Social media can increase the likelihood that screening or treatment interventions are accessed when appropriate, including where and when (and when not) to seek care and how to be treated if ill.4 For noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes, chronic communicable diseases such as HIV, and mental health disorders such as depression, social media applications and networks provide peer support that can reduce symptom burden and improve quality of life, disseminate information on effective treatments, and promote recovery from illness.18 Finally, social media can play an important role in enhancing social connectedness and well-being for populations with a range of disabilities or those subject to social or geographic isolation.19 Relatedly, social media can serve as an important human bridge that connects people during outbreaks that require social distancing as well as a vehicle for uplifting and even humorous messages or other forms of support that promote healthy coping responses and advance communal resilience.4

INFLUENCING FACTORS

A number of factors influence the role of social media across the SPHERE continuum (Figure 1).

Attributes of Health Communications

Features of the health communications can influence their impacts on the public, including

framing and content associated with messages, including their language, clarity, and ability to engage;

sources and messengers of the information, including official and unofficial sources;

characteristics of the platform and its participants;

timing of messages;

volume of messages, including numbers of messages initiated and remessaged;

influence of amplifiers and detractors on platforms,20 including autonomous social media agents (bots)21;

presence of message sponsorship and disclosure therein; and

rules, regulations, and controls, or extent of information filtering or censorship applied by the platform or its governing bodies.

Characteristics of the Pathogen or Disease

Characteristics of the pathogen or disease that are the subjects of communications can determine which of the functions in the SPHERE continuum social media is focused on. Spikes in related communications occur in the midst of a pandemic, such as COVID-19, or right after a catastrophic public or media event, such as a mass shooting or an unexpected celebrity death. Social media communications regarding common, noncommunicable diseases, such as diabetes or cancer, most often increase in the context of (1) regulatory efforts, such as sugary drink taxes or antivaping initiatives; (2) the emergence of controversial clinical or public health guidelines; or (3) compelling scientific publications, such as a controversial study—whose authors had financial conflicts with the food industry—that supported the consumption of red meat and a study demonstrating how beverage industry–related financial conflicts of interest unduly influence research examining the effects of sugary drinks on obesity and diabetes.22

Properties of the Host

The sociocultural and political contexts in which threats to health emerge present variable degrees of susceptibility or resistance to social media messages, engendering either receptivity or critical appraisal.23 These contexts can influence the extent of public trust in health authorities and the prevalence of science denial and conspiracy thinking. The balance between trust in science versus denial of science is a function, in part, of the perceived trustworthiness of official sources and channels.24 Characteristics and behaviors of social networks that receive and disseminate health communications to a community of listeners and amplifiers can also influence a subpopulation’s likelihood of responding to one or more of the functions on the SPHERE continuum, affecting whether social media work to undermine or support health-promoting information, beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, and population health. Social media networks and online communities often serve as echo chambers that foster the replication and amplification of health content that reflects the community’s beliefs and values, regardless of whether the communications are inaccurate versus accurate, or unofficial versus official, representations.

Under certain conditions, however, social media can serve as a platform that gradually reveals the wisdom of the crowd—enabling the sharing of disparate opinions and the development of a consensus that is more accurate, including decisions on productive, communal action. Specifically, in decentralized communication networks, group estimates become reliably more accurate as a result of information exchange, depending on network structure.25 Governments, regulatory agencies, and social media platforms themselves can institute digital policies and practices that determine allowable content and the extent of dissemination, including preferential message promotion, filtering and blocking messages, and censoring nonofficial communications.

OUTCOMES OF INTEREST

Health research on communications in the era of social media has largely limited itself to outcomes such as the accuracy of information, extent of dissemination, uptake of misinformation, and effects on knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs.3,7 A more comprehensive and balanced approach to measuring the public health effects of social media communications is needed (Figure 1). First, effects should include proximal communication outcomes, including surveillance and monitoring, uptake of accurate (and inaccurate) information, and public awareness. Intermediate outcomes should involve domains such as outbreak preparedness, implementation of health-promoting policies, mobilization of resources to combat disease, the adoption of health-promoting behaviors, and social well-being. Distal outcomes include disease incidence, transmission rates and morbidity and mortality, and cost-effectiveness. Finally, a number of collateral (nonhealth) consequences of communications disseminated via social media should be considered, including economic consequences, preferential or irrational allocation of public resources, mass anxiety or fear, discrimination and stigma, denial of basic rights, retaliation, and the erosion of public trust.12

CONCLUSIONS

Communication is the fundamental social process through which we all interact. And communicating about health—discussing how to stay strong, healthy, and well; sharing beliefs about how to avoid sickness and death; exchanging opinions about who will live or die; asking why some die and others do not—is a practice that likely began as early as human language emerged. From that perspective, the continuum of functions that social media can play with respect to public health is not surprising. What is novel, however, is how significantly social media has increased the capacity of communication to influence public health. To an unprecedented degree, the popularity and technical sophistication of social media platforms have translated into health discourse becoming more ubiquitous; content becoming more creative, innovative, and engaging; production becoming both more democratized and more market sponsored; communications becoming massively scalable and rapidly spreadable by influencers and autonomous bots20; artificial intelligence enabling high-volume tailoring and targeting of communications; and governments, regulatory agencies, corporate and sponsoring entities, and social media platforms themselves having the capacity to control the content and flow of communications.24

Yet scientists’ and public health practitioners’ abilities to make sense of the myriad ways that social media can influence public health have lagged, lacking a coherent framework for integrating core elements from communication and public health sciences. The SPHERE continuum can be used to guide researchers and practitioners. Given the scope of the digital revolution and its impact on contemporary communication, observational research is needed to deepen our understanding of the complex dynamics inherent in how social media functions across the public health continuum.

In this regard, the SPHERE continuum can inform and explain the work of health communication research as well as provide a common language and an easily understood framework to encourage collaborations with practitioners in ways that can advance public health. Specifically, the framework can be employed to jointly generate the most salient research questions, select the most relevant outcomes, and apply the most appropriate methods. In addition, the SPHERE continuum provides landmarks and signposts for the design of experimental (simulation) research in carefully controlled settings via randomized controlled trials with selected samples, as well as a blueprint for real-world, real-time, practice-based quasiexperimental research to be conducted with large populations in collaboration with public health practitioners and communication entities. Both types of interventional research can further inform efforts to effectively harness social media for health promotion while maintaining the unique appeal and value of social media as a platform for constructive discourse in an open society.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Culture of Health grant 74557 to D. S.) and the National Institutes of Health (grants R01 NLM012355-01A1 and 2P30 NIDDK092924 to D. S., K01CA190659 to D. C., and P30DK092924 and K01CA190659 to A. S. R.).

Note. The opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the funders.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pew Research Center. Social media fact sheet. 2019. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- 2.Zhang X, Wen D, Liang J, Lei J. How the public uses social media WeChat to obtain health information in China: a survey study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2017;17(suppl 2):66. doi: 10.1186/s12911-017-0470-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun M, Yang L, Chen W et al. Current status of official WeChat accounts for public health education. J Public Health (Oxf). 2020 doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdz163. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giustini D, Ali SM, Fraser M, Kamel Boulos MN. Effective uses of social media in public health and medicine: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Online J Public Health Inform. 2018;10(2):e215. doi: 10.5210/ojphi.v10i2.8270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orr D, Baram-Tsabari A, Landsman K. Social media as a platform for health-related public debates and discussions: the polio vaccine on Facebook. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2016;5(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s13584-016-0093-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broniatowski DA, Jamison AM, Qi S et al. Weaponized health communication: Twitter bots and Russian trolls amplify the vaccine debate. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(10):1378–1384. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allegrante JP, Auld ME. Advancing the promise of digital technology and social media to promote population health. Heal Educ Behav. 2019;46(2 suppl):5–8. doi: 10.1177/1090198119875929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwon M, Park E. Perceptions and sentiments about electronic cigarettes on social media platforms: systematic review. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(1):e13673. doi: 10.2196/13673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freeman B, Kelly B, Baur L et al. Digital junk: food and beverage marketing on Facebook. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(12):e56–e64. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vassallo AJ, Kelly B, Zhang L, Wang Z, Young S, Freeman B. Junk food marketing on Instagram: content analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2018;4(2):e54. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.9594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pagoto S, Waring ME, Xu R. A call for a public health agenda for social media research. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(12):e16661. doi: 10.2196/16661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zarocostas J. How to fight an infodemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):676. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30461-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Southwell BG, Niederdeppe J, Cappella JN et al. Misinformation as a misunderstood challenge to public health. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(2):282–285. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Shea J. Digital disease detection: a systematic review of event-based internet biosurveillance systems. Int J Med Inform. 2017;101:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.English PB, Richardson MJ, Garzón-Galvis C. From crowdsourcing to extreme citizen science: participatory research for environmental health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:335–350. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gough A, Hunter RF, Ajao O et al. Tweet for behavior change: using social media for the dissemination of public health messages. JMIR Public Heal Surveill. 2017;3(1):e14. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.6313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schillinger D, Huey N. Messengers of truth and health—young artists of color raise their voices to prevent diabetes. JAMA. 2018;319(11):1076–1078. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox S. After Dr Google: peer-to-peer health care. Pediatrics. 2013;131(suppl 4):S224–S225. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3786K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: the need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yun GW, Morin D, Park S et al. Social media and flu: media Twitter accounts as agenda setters. Int J Med Inform. 2016;91:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sutton J. Health communication trolls and bots versus public health agencies’ trusted voices. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(10):1281–1282. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schillinger D, Tran J, Mangurian C, Kearns C. Do sugar-sweetened beverages cause obesity and diabetes? Industry and the manufacture of scientific controversy. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(12):895–897. doi: 10.7326/L16-0534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong JEL, Leo YS, Tan CC. COVID-19 in Singapore—current experience: critical global issues that require attention and action. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2467. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holeman I, Cookson TP, Pagliari C. Digital technology for health sector governance in low and middle income countries: a scoping review. J Glob Health. 2016;6(2):020408. doi: 10.7189/jogh.06.020408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker J, Brackbill D, Centola D. Network dynamics of social influence in the wisdom of crowds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(26):E5070–E5076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1615978114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]