Abstract

Objectives. To examine whether growing use of telemental health (TMH) has reduced the rural–urban gap in specialty mental health care use in the United States.

Methods. Using 2010–2017 Medicare data, we analyzed trends in the rural–urban difference in rates of specialty visits (in-person and TMH).

Results. Among rural beneficiaries diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, TMH use grew by 425% over the 8 years and, in higher-use rural areas, accounted for one quarter of all specialty mental health visits in 2017. Among patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, TMH visits differentially grew in rural areas by 0.14 visits from 2010 to 2017. This growth partially offset the 0.42-visit differential decline in in-person visits in rural areas. In net, the gap between rural and urban patients in specialty visits was larger by 2017.

Conclusions. TMH has improved access to specialty care in rural areas, particularly for individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. While growth in TMH use has been insufficient to eliminate the overall rural–urban difference in specialty care use, this difference may have been larger if not for TMH.

Public Health Implications. Targeted policy to extend TMH to underserved areas may help offset declines in in-person specialty care.

Mental illnesses are common—in the United States, the lifetime prevalence of mental illness that impairs functioning is 46%.1 However, mental health treatment rates in the United States remain low, particularly for specialty care. Fewer than a third of individuals with mental illness in the United States received specialty mental health care in the previous year.2 Among individuals with more serious mental illness, fewer than half received specialty mental health care,3 and 43% reported unmet need for mental health care.4 Treatment by a specialty mental health provider, particularly among those patients with serious and disabling mental illness, has been associated with greater use of guideline-concordant care.1,4

Specialty care rates are particularly low in rural areas relative to urban areas, with rural patients receiving up to 73% fewer specialty mental health visits than urban residents.5 While barriers to treatment exist for all, barriers to access are greater in rural areas, where specialty provider shortages are especially acute and individuals seeking treatment may have to travel long distances.6–9

Telemedicine in the form of live video teleconferencing with a specialty mental health clinician—known as telemental health—has the potential to address this rural–urban difference in specialty mental health use. In randomized trials, telemental health has been shown to be comparable or even superior to in-person care,10–12 including for patients with depression13–15 and schizophrenia.16–18 Under current regulations, Medicare chiefly covers telemedicine visits if a beneficiary is hosted at a clinic or other health care facility located in a rural area (that is, telemental health visits cannot be received in the home or in a hosting site in an urban area; see Appendix J, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, for details of how eligibility for telemedicine is determined). While Medicare’s coverage of telemedicine began as early as 2000,19 telemental health use among rural Medicare beneficiaries with mental illness has grown most rapidly starting in 2010 and has been increasing at a rate of roughly 50% per year.20 Many bills have been introduced in Congress to address telemedicine barriers and accelerate growth.21

Given the growing use of telemental health in rural areas, it is possible that the rural–urban difference in specialty mental health treatment has narrowed. To answer this question, using 2010–2017 Medicare data, we describe trends in rural–urban differences in outpatient specialty mental health utilization rates—both in-person and via telemental health—among adults with mental illness.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective analysis of 2010–2017 de-identified Medicare Part B claims for a 20% random sample of Medicare beneficiaries throughout the United States. We excluded patients not continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B for 12 months during the calendar year.

Identification of Adult Beneficiaries With Mental Illness

We focused on 2 populations of adults aged 18 years and older: (1) those diagnosed with any mental illness and (2) the subgroup of patients with any mental illness diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. We created person–year cohorts for each calendar year. To be included in our mental illness population, we required at least 2 outpatient visits with a mental health diagnosis in any diagnosis field on different days or 1 inpatient admission with a mental health diagnosis as the primary diagnosis in a given year (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9; Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1980], codes 295 to 302, 306 to 309, or 311 to 316 and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision [ICD-10; Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992], codes F20 to F69 or F80 to F99). To identify patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, we used ICD-9 codes 295, 296.0, 296.1, 296.4 to 296.9, 297, 301.11, or 301.13 and ICD-10 codes F20 to F29, F30 to F31, or F34. We examined schizophrenia and bipolar disease as examples of more serious and disabling mental illnesses. The proportion of urban and rural beneficiaries included in the person–year cohorts identified by different criteria (1 or more inpatient visits, 2 or more outpatient visits, or both) was similar (Appendix I, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Beneficiary Characteristics

We captured age, sex, rural–urban status, county-level Federal Information Processing Standards code, dual enrollment in the Medicaid program, and diagnosis of co-occurring substance use disorder (SUD). We identified SUD if a patient had at least 1 SUD claim in any diagnostic field or at least 1 inpatient admission for SUD in the primary diagnostic field in a given year (ICD-9 codes 291 to 292, 303, 304, 305.0, 305.2 to 305.7, or 305.9 and ICD-10 codes F10 to F16 or F18 to F19; see Appendix E, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, for full list of SUD codes). Consistent with previous work,22 only 1 SUD claim was required because SUD is often undercoded in administrative claims data.

Consistent with Medicare’s definition, we classified patients as rural if they lived outside a metropolitan statistical area or in a community categorized as a nonmetropolitan rural–urban commuting area code of 4 to 10, and urban if they lived in an area with rural–urban commuting area code of 1 to 3. While other measures of rural and urban status exist, we implemented Medicare’s definition as it determines reimbursement for telemental health visits for rural patients.

Classification of Mental Health Visits

As in our previous work,19 we defined visits (in-person and telemedicine) as outpatient mental health–related visits if the first or second diagnosis code was a mental health diagnosis (using the list of previously mentioned diagnosis codes). To address the possibility of double counting because of multiple claims for a single visit, we included a maximum of 1 visit per day.

We defined specialty mental health visits as visits to a psychiatrist, psychologist, or clinical social worker and identified them by using Medicare specialty codes 26, 86, 62, 68, and 80.

Telemental health visits were outpatient mental health visits with GT, GQ, or 95 modifier codes, or place-of-service code 02 (telemedicine). We classified all other outpatient specialty mental health visits as in-person visits.

Utilization Measures

For each calendar year, we measured the number of telemental health, in-person, and total (telemental plus in-person) specialty mental health visits per rural and urban Medicare beneficiary per year who met diagnostic criteria described previously. We calculated these rates by dividing the total number of visits for each group by the total number of beneficiaries in each group per year. We assigned zero visits if the beneficiary did not have a specialty visit during the year.

Analyses

To describe our sample, we present unadjusted averages of patient characteristics for urban and rural patients over time in Table 1. We measured the standardized difference in patient characteristics between 2010 and 2017 among rural and urban beneficiaries. Standardized differences are increasingly used in health services research to compare the distribution of continuous and dichotomous covariates between groups, particularly in observational studies using big data.23 Across all years in our data, we measured unadjusted telemental health utilization rates in both the urban and rural populations.

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of Medicare Patients Diagnosed With Mental Illness and Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder in Rural and Urban Areas: United States, 2010 Versus 2017

| Rural Beneficiaries |

Urban Beneficiaries |

|||||

| 2010 | 2017 | Standardized Differencea | 2010 | 2017 | Standardized Differencea | |

| All beneficiaries diagnosed with mental illness | ||||||

| No. | 238 606 | 348 080 | 620 402 | 897 775 | ||

| Age, y | ||||||

| Mean | 65.3 | 67.0 | 0.11 | 66.0 | 68.1 | 0.14 |

| 18–39, % | 7.7 | 5.7 | −0.08 | 7.6 | 5.6 | −0.08 |

| 40–64, % | 34.8 | 29.8 | −0.11 | 33.3 | 26.1 | −0.16 |

| 65–79, % | 38.2 | 47.4 | 0.18 | 37.6 | 49.0 | 0.23 |

| ≥ 80, % | 19.3 | 17.1 | −0.06 | 21.4 | 19.4 | −0.05 |

| Male, % | 35.1 | 34.1 | 0.02 | 35.3 | 34.4 | 0.02 |

| Medicaid dual enrollment, % | 49.2 | 41.9 | −0.15 | 46.4 | 36.6 | −0.20 |

| SUD comorbidity, % | 5.7 | 7.5 | 0.08 | 6.2 | 7.8 | 0.07 |

| Beneficiaries diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder | ||||||

| No. | 47 138 | 54 467 | 147 090 | 159 523 | ||

| Age, y | ||||||

| Mean | 54.3 | 57.2 | 0.19 | 54.8 | 57.9 | 0.20 |

| 18–39, % | 18.2 | 14.8 | −0.09 | 16.9 | 14.5 | −0.07 |

| 40–64, % | 55.9 | 52.5 | −0.07 | 56.7 | 50.4 | −0.13 |

| 65–79, % | 20.0 | 25.3 | 0.13 | 20.0 | 27.3 | 0.17 |

| ≥ 80, % | 6.0 | 7.4 | 0.06 | 6.4 | 7.9 | 0.06 |

| Male, % | 44.1 | 43.8 | −0.01 | 45.8 | 45.1 | −0.01 |

| Medicaid dual enrollment, % | 73.0 | 72.8 | 0.00 | 70.9 | 68.8 | −0.05 |

| SUD comorbidity, % | 10.0 | 13.4 | 0.11 | 11.0 | 13.9 | 0.09 |

Notes. SUD = substance use disorder. The sample size is based on the 20% random sample of Medicare beneficiaries.

Standardized difference measures the distance between the mean of each beneficiary characteristic from 2010 and 2017 for both rural and urban beneficiaries.

To estimate rural–urban differences in service utilization rates over time, we estimated a linear regression model of each utilization outcome using the initial and final years of data only (2010 and 2017). We calculated the unadjusted rural–urban difference in the number of specialty outpatient mental health visits (in-person, telemental health, and overall) per Medicare beneficiary for each year and observed a linear change over time for each outcome variable (Appendix G, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). To assess change in the rural–urban difference in specialty care use between 2010 and 2017, we tested the significance of the rural-by-year interaction term. Negative coefficient values indicated an increase in the rural–urban difference, and positive values indicated a decrease. We controlled for beneficiary characteristics as defined previously and state fixed effects (see Appendix A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, for model specification). Analyses adjusted for repeated measures (i.e., the same beneficiary in 2010 and 2017).

In a sensitivity analysis, we used a zero-inflated negative binomial regression model to account for the distributional characteristics of the outcome variables. The results were similar in both the direction of the point estimate and level of significance for the rural-by-year interaction term. Results from linear regression models are presented in Tables 2 and 3, and results from the negative binomial models are presented in Appendix C (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

TABLE 2—

Differences in the Number of Specialty Outpatient Mental Health Visits per Beneficiary Diagnosed With Mental Illness Between Rural and Urban Patients: United States, 2010 vs 2017

| Rural Rate of Mental Health Visits per Individual |

Urban Rate of Mental Health Visits per Individual |

Difference in Rate of Mental Health Visits per Individual (Rural vs Urban) |

Adjusted Change in Difference From 2010 to 2017,a Rural vs Urban (95% CI) | ||||

| 2010 | 2017 | 2010 | 2017 | 2010 | 2017 | ||

| All beneficiaries diagnosed with mental illness | |||||||

| In-person | 1.73 | 1.43 | 2.93 | 2.61 | −1.20 | −1.19 | −0.03 (−0.07, 0.01) |

| TMH | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.04* (0.038, 0.042) |

| All | 1.75 | 1.49 | 2.93 | 2.62 | −1.19 | −1.13 | 0.01 (−0.03, 0.05) |

| Beneficiaries diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder | |||||||

| In-person | 4.12 | 3.52 | 5.52 | 5.33 | −1.40 | −1.81 | −0.42* (−0.55, −0.29) |

| TMH | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.14* (0.13, 0.15) |

| All | 4.16 | 3.73 | 5.53 | 5.36 | −1.36 | −1.63 | −0.28* (−0.41, −0.15) |

Notes. CI = confidence interval; TMH = telemental health. Adjusted change is based on a linear regression model. Rates were calculated by dividing the total number of visits for each group by the total number of beneficiaries in each group.

Negative value indicates that the rural–urban difference in the rate of outpatient mental health visits per individual increased between 2010 and 2017. Positive value indicates that the rural–urban difference decreased between 2010 and 2017.

P < .05.

TABLE 3—

Differences in the Number of Specialty Outpatient Mental Health Visits per Beneficiary Diagnosed With Mental Illness Between All Urban Patients and Rural Patients Who Resided in Counties With the Highest Uptake of Telemental Health: United States, 2010 vs 2017

| Rurala Rate of Mental Health Visits per Individual |

Urban Rate of Mental Health Visits per Individual |

Difference in Rate of Mental Health Visits per Individual (Ruralb vs Urban) |

Adjusted Change in Difference From 2010 to 2017,a Rural vs Urban (95% CI) | ||||

| 2010 | 2017 | 2010 | 2017 | 2010 | 2017 | ||

| All beneficiaries diagnosed with mental illness | |||||||

| In-person | 1.77 | 1.29 | 2.93 | 2.61 | −1.16 | −1.32 | −0.24* (−0.35, −0.12) |

| TMH | 0.05 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.37 | 0.32* (0.31, 0.33) |

| All | 1.83 | 1.67 | 2.93 | 2.62 | −1.11 | −0.95 | 0.09 (−0.03, 0.20) |

| Beneficiaries diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder | |||||||

| In-person | 4.38 | 3.14 | 5.52 | 5.33 | −1.14 | −2.19 | −1.06* (−1.43, −0.70) |

| TMH | 0.11 | 1.07 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 1.04 | 0.93* (0.91, 0.96) |

| All | 4.49 | 4.21 | 5.53 | 5.36 | −1.04 | −1.15 | −0.13 (−0.50, 0.24) |

Notes. CI = confidence interval; TMH = telemental health. Adjusted change is based on a linear regression model. Rates were calculated by dividing the total number of visits for each group by the total number of beneficiaries in each group.

Negative value indicates that the rural–urban difference in the rate of outpatient mental health visits per individual increased between 2010 and 2017. Positive value indicates that the rural–urban difference decreased between 2010 and 2017.

This analysis included the top decile of rural patients residing in counties with the highest telemental health uptake in 2017.

P < .05.

Rural Counties With Highest Telemental Health Utilization

While telemental health uptake has been modest overall, uptake is highly variable across counties.19 To offer insight on how future growth in telemental health could affect rural–urban differences in specialty mental health care utilization, we performed a subanalysis focused on the counties with the highest uptake of telemental health in 2017. The assumption is that, with continued growth, the care patterns in these counties could be a baseline estimate for what we will see nationally in the future. We compared differences between all urban patients versus rural patients who reside in these counties.

To identify these high-use counties, we measured each county’s telemental health utilization rates for 2017 among rural residents. We rank ordered the counties, and we included the top counties encompassing 10% of our rural sample with the highest telemental health utilization rates in this subanalysis. The 348 080 rural Medicare patients diagnosed with mental illness resided in 2719 counties in 2017. The high-use counties encompassed 358 counties with 10% of these patients (34 808 beneficiaries). We used the same 358 counties for both 2010 and 2017.

RESULTS

Among the 20% sample of Medicare beneficiaries (n = 12 856 313 in 2010; n = 13 224 017 in 2017), there were 238 606 rural and 620 402 urban beneficiaries diagnosed with any mental illness in 2010 and 348 080 rural and 897 775 urban beneficiaries diagnosed in 2017. The schizophrenia or bipolar sample comprised 47 138 rural and 147 090 urban beneficiaries in 2010, and 54 467 rural and 159 523 urban beneficiaries in 2017 (Table 1).

Between 2010 and 2017, there was a decrease in the proportion of beneficiaries diagnosed with any mental illness dually enrolled in the Medicaid program (49% to 42% and 46% to 37%, rural and urban, respectively) and an increase in the proportion of beneficiaries with SUD comorbidity (5.7% to 7.5% and 6.2% to 7.8%, rural and urban, respectively). From 2010 to 2017, there was an increase in the proportion of beneficiaries with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder who had an SUD comorbidity (10% to 13.4% and 11% to 13.9%, rural and urban, respectively; Table 1).

Visit Trends Among Patients With Any Mental Illness

Rates of in-person specialty mental health visits fell from 2010 to 2017 among both urban and rural beneficiaries diagnosed with any mental illness. The decline was differentially larger among rural residents between 2010 and 2017, but the change in the difference was not statistically significant (differential decline in rural areas = −0.03 visits; 95% confidence interval [CI] = −0.07, 0.01).

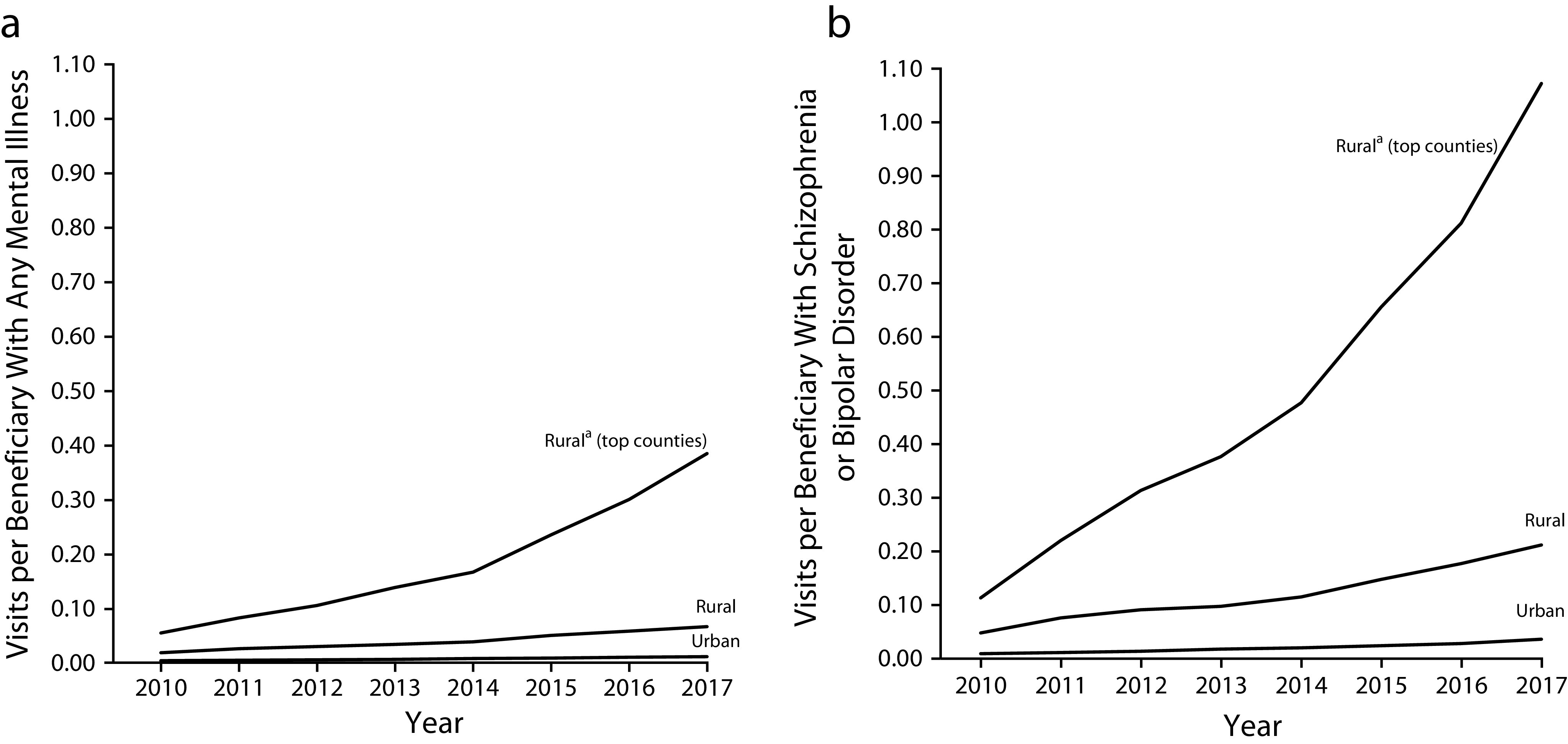

Rates of telemental health specialty visits grew among Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with any mental illness, increasing from 0.02 visits per rural beneficiary in 2010 to 0.06 visits in 2017 and from approximately zero visits per urban beneficiary in 2010 to 0.01 visits in 2017 (Figure 1 and Table 2). The differential increase in telemental health specialty care in rural areas was 0.04 visits (95% CI = 0.038, 0.042). This differential increase in telemental health was similar in magnitude to the differential decline in in-person visits and, in net, the overall rural–urban difference in specialty care use did not change (+0.01; 95% CI = −0.03, 0.05).

FIGURE 1—

Unadjusted Rates of Telemental Health Specialty Care Use Among Medicare Beneficiaries Diagnosed With Mental Illness in Rural and Urban Areas for Beneficiaries Diagnosed With (a) Any Mental Illness or (b) Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder: United States, 2010–2017

aRural patients who reside in counties with the highest uptake of telemental health in 2017.

Visit Trends Among Patients With Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder

Rates of in-person specialty mental health care among those with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder fell from 2010 to 2017, and the decline was larger in rural areas (differential decline in rural areas = −0.42 visits; 95% CI = −0.55, −0.29).

Telemental health specialty visits grew among Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, increasing from 0.04 visits per rural beneficiary in 2010 to 0.21 visits in 2017, and 0.01 visits per urban beneficiary in 2010 to 0.03 visits in 2017. The differential increase in telemental health specialty care in rural areas (0.14 visits; 95% CI = 0.13, 0.15) partially offset the decline in in-person visits. In net, there was an increase in the rural–urban difference in all specialty care (differential decline in rural areas = −0.28 visits; 95% CI = −0.41, −0.15).

Counties With Highest Telemental Health Utilization

In a subanalysis, we examined rural–urban differences in specialty care between all urban patients and 10% of rural patients who resided in counties with the highest telemental health utilization rates in 2017 (in Appendix B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, we compare the patient characteristics of these counties). Among rural beneficiaries in these areas with any mental illness, telemental health specialty visits increased from 0.05 visits per rural beneficiary in 2010 to 0.38 visits in 2017. In 2017, telemental health visits accounted for 23% of all outpatient specialty visits in these areas (0.38/1.67 = 23%).

In this subset of rural areas, the differential increase of telemental health visits (0.32 visits; 95% CI = 0.31, 0.33) fully offset the differential decline in in-person specialty care (–0.24 visits; 95% CI = −0.35, −0.12), resulting in no net change in the rural–urban difference (0.09 visits; 95% CI = −0.03, 0.20).

We found a similar trend among rural beneficiaries diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, but the changes were greater in magnitude. In this subset of rural areas, telemental health visits increased from 0.11 to 1.07 visits per rural beneficiary in 2010 and 2017, respectively. Telemental health specialty visits accounted for 25% of all outpatient mental health specialty visits in 2017 among rural beneficiaries diagnosed with any mental illness (1.07/4.21 = 25%). Rates of in-person specialty visits fell from 2010 to 2017, particularly for these rural areas. The differential increase in telemental health (0.93 visits; 95% CI = 0.91, 0.96) in these rural areas fully offset the differential decline in in-person specialty care (–1.06 visits; 95% CI = −1.43, −0.70). As a result, there was no significant change in the rural–urban difference in all specialty mental health care between 2010 and 2017 (–0.13 visits; 95% CI = −0.50, 0.24).

DISCUSSION

There has been great interest in the potential for telemental health to increase access to specialty mental health care among rural beneficiaries with mental illness and thereby reduce rural–urban differences in use of specialty mental health visits. Across both urban and rural populations, we observed a general decline in in-person specialty visits from 2010 to 2017 that was differentially greater in rural areas compared with urban areas. The differential growth of telemental health in rural areas has helped partially or fully offset some of this differential decline of in-person visits in rural areas, particularly for individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

The patterns we observed in rural areas with higher uptake of telemental health are promising if they portend what we may see nationally in the future given the growth in telemental health over the past several years. In rural counties with the highest telemental health uptake, telemental health made up roughly a quarter of all outpatient mental health specialty visits in 2017. In these rural areas, the differential growth of telemental health in rural areas has fully offset the differential decline in in-person specialty mental health care. Together, this suggests that, in these communities, telemental health has already become a core component of specialty mental health care delivery,24 in particular for those with more serious and disabling mental illnesses. Without the growth of telemental health, the rural–urban differences would likely have been even larger. Given increasing shortages in in-person specialty providers in rural areas, telemental health may be even more important in the future. We observed wide variation in the use of telemental health across communities, and future research should explore local factors that might explain the use of telemental health.

We observed a general decline in use of specialty mental health care attributable to a substantial decline in in-person visits. It is unclear what is driving the overall decline in in-person mental health specialty care, particularly in rural areas. Potential factors that may contribute include a relative decline in supply of specialty providers6 because of an aging mental health workforce25 and a decrease in the number of specialty providers accepting Medicare.7 Another factor driving the drop in in-person visits is that they could be replaced with telemental health visits. Given the general decline across the United States in all areas in in-person specialty mental health visits, our hypothesis was that telemental health would be additive to in-person care. However, it is possible that, in some cases, telemental health visits are replacing in-person specialty mental health visits and have no net impact on total use of specialty mental health care (Appendix H, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). In previous qualitative interviews with community mental health centers, they report that they generally view telemental health visits as a supplement to in-person care.24 However, in some cases, clinics allow patients to choose between tele- and in-person visits, which could imply that telemental health visits could be replacing in-person care.

Limitations

These analyses had several limitations. First, our analyses were limited to the Medicare population and, therefore, the care patterns we observed may not translate to the Medicaid or commercially insured population. It is notable that a large proportion of our Medicare mental illness cohort is disabled and aged younger than 65 years. Beneficiaries aged younger than 65 years used specialty mental health care (in-person, telemental health, and overall) at higher rates than those aged 65 years or older (Appendix F, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org), indicating that their needs may be different than those aged 65 years or older. Second, we may have undercounted the number of telemental health visits. For example, clinicians may provide telemental health services for which they do not seek reimbursement.26 To the degree that this undercounting is differential in rural areas, this could bias our estimates on trends in the differences in care. Third, our definition of specialty mental health care providers was limited to psychologists, psychiatrists, and clinical social workers. Because Medicare data do not specify the specialization of other providers (such as psychiatric nurse practitioners), we were unable to include these other specialty providers. It is possible that nurse practitioners are differentially used in rural areas. However, given that only 2.9% of all nurse practitioners specialize in psychiatric or mental health care, and less than 18% practice in rural communities,27 it is unlikely to substantially affect our results.

Public Health Implications

Our findings demonstrate that telemental health could be an important mechanism for improving access to specialty mental health care in lieu of in-person care, particularly among rural Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with serious and disabling mental illnesses. In some rural communities in the United States, telemental health has already become a core component of specialty mental health care delivery. To date, Medicare has taken a targeted approach focused primarily on telemedicine visits only for rural beneficiaries and those that are hosted at a local clinic or provider.

Policy interventions to increase use of telemental health specialty care could help to further offset declines in in-person specialty care. One strategy would be to allow rural patients to receive telemedicine visits in their home. In urban areas, underserved populations could also be targeted by allowing patients of federally qualified health centers to receive telemedicine. Another strategy would be to increase reimbursement for telemental health specialty visits such that telemedicine is paid more than in-person visits. While all of these interventions will address access barriers attributable to proximity to a provider, it will not address a lack of providers. The national decline of mental health providers, in particular those who accept Medicare,7 means that there simply may not be enough providers to deliver specialty mental health care to rural and urban residents and that interventions are also required to increase the supply of mental health providers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH112829-01, T32MH019733).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflict of interest.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This study was reviewed and approved by the Harvard Medical School institutional review board.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG et al. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(24):2515–2523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa043266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Bruce ML, Koch JR, Laska EM, Leaf PJ. The prevalence and correlates of untreated serious mental illness. Health Serv Res. 2001;36(6 pt 1):987–1007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang PS, Lane MS, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merwin E, Hinton I, Dembling B, Stern S. Shortages of rural mental health professionals. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2003;17(1):42–51. doi: 10.1053/apnu.2003.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirby JB, Zuvekas SH, Borsky AE, Ngo-Metzger Q. Rural residents with mental health needs have fewer care visits than urban counterparts. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38(12):2057–2060. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):176–181. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bishop TF, Seirup JK, Pincus HA, Ross JS. Population of US practicing psychiatrists declined, 2003–13, which may help explain poor access to mental health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(7):1271–1277. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrilla CHA, Patterson DG, Garberson LA, Coulthard C, Larson EH. Geographic variation in the supply of selected behavioral health providers. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(6)(suppl 3):S199–S207. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García-Lizana F, Muñoz-Mayorga I. What about telepsychiatry? A systematic review. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(2) doi: 10.4088/PCC.09m00831whi. pii: PCC.09m00831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chakrabarti S. Usefulness of telepsychiatry: a critical evaluation of videoconferencing-based approaches. World J Psychiatry. 2015;5(3):286–304. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v5.i3.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilty DM, Ferrer DC, Parish MB, Johnston B, Callahan EJ, Yellowlees PM. The effectiveness of telemental health: a 2013 review. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(6):444–454. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fortney JC, Pyne JM, Mouden SB et al. Practice-based versus telemedicine-based collaborative care for depression in rural federally qualified health centers: a pragmatic randomized comparative effectiveness trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(4):414–425. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12050696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruskin PE, Silver-Aylaian M, Kling MA et al. Treatment outcomes in depression: comparison of remote treatment through telepsychiatry to in-person treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(8):1471–1476. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.García-Lizana F, Munoz-Mayorga I. Telemedicine for depression: a systematic review. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2010;46(2):119–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2010.00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zarate CA, Jr, Weinstock L, Cukor P et al. Applicability of telemedicine for assessing patients with schizophrenia: acceptance and reliability. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(1):22–25. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasckow J, Felmet K, Appelt C, Thompson R, Rotondi A, Haas G. Telepsychiatry in the assessment and treatment of schizophrenia. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2014;8(1):21–27A. doi: 10.3371/CSRP.KAFE.021513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunkeler EM, Meresman JF, Hargreaves WA et al. Efficacy of nurse telehealth care and peer support in augmenting treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(8):700–708. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.8.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Telehealth services. January 2019. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/TelehealthSrvcsfctsht.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2020.

- 20.Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Souza J et al. Rapid growth in mental health telemedicine use among rural Medicare beneficiaries, wide variation across states. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(5):909–917. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Congressional Budget Office. H.R. 3417: Beneficiary Education Tools, Telehealth, and Extenders Reauthorization Act of 2019. September 30, 2019. Available at: https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2019-09/hr3417.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2019.

- 22.Huskamp HA, Busch AB, Souza J et al. How is telemedicine being used in opioid and other substance use disorder treatment? Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37(12):1940–1947. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Austin PC. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Stat Simul Comput. 2009;38(6):1228–1234. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uscher-Pines L, Raja P, Qureshi N, Huskamp HA, Busch A, Mehrotra A. Use of telemental health in conjunction with in-person care: a qualitative exploration of implementation models. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(5):419–426. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merritt Hawkins. 2017 review of physician and advanced practitioner recruiting incentives. Available at: https://www.merritthawkins.com/uploadedFiles/MerrittHawkins/Pdf/2017_Physician_Incentive_Review_Merritt_Hawkins.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2019.

- 26.Antoniotti NM, Drude KP, Rowe N. Private payer telehealth reimbursement in the United States. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(6):539–543. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goolsby M. AANP national nurse practitioner sample survey: an overview. JAANP. 2009–2010;2009;23(5):266–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2011.00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]