Abstract

Objectives. To identify lessons learned from implementation of the nation’s first sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) excise tax in 2015 in Berkeley, California.

Methods. We interviewed city stakeholders and SSB distributors and retailers (n = 48) from June 2015 to April 2017 and analyzed records through January 2019.

Results. Lessons included the importance of thorough and timely communications with distributors and retailers, adequate lead time for implementation, advisory commissions for revenue allocations, and funding of staff, communications, and evaluation before tax collection begins. Early and robust outreach about the tax and programs funded can promote and sustain public support, reduce friction, and facilitate beverage price increases on SSBs only. No retailer reported raising food prices, indicating that Berkeley’s SSB tax did not function as a “grocery tax,” as industry claimed. Revenue allocations totaled more than $9 million for public health, nutrition, and health equity through 2021.

Conclusions. The policy package, context, and implementation process facilitated translating policy into public health outcomes. Further research is needed to understand long-term facilitators and barriers to sustaining public health benefits of Berkeley’s tax and how those differ from facilitators and barriers in jurisdictions facing significant industry-funded repeal efforts.

Berkeley, California became the first US jurisdiction to pass a sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) tax1 in 2014 via referendum, which garnered 76% of the vote. The ordinance levied a $0.01 per ounce excise tax on SSB distribution. Artificially sweetened beverages are not taxable. Although SSB taxes evoke higher support when revenues are designated for health or education, Berkeley’s measure appropriated revenues to the general fund. This was a strategic decision made by SSB tax proponents and City Council to keep the vote threshold at a simple majority; California requires a two thirds vote for earmarked taxes.2 However, to promote revenue allocations aligned with public health, the ordinance established an SSB Product Panel of Experts (SSBPPE) to advise the city on funding “programs to further reduce [SSB] consumption … [and its] consequences.”

As of fall 2019, 8 US jurisdictions had implemented SSB taxes.1 Since Berkeley’s implementation, the evidence base for SSB taxation has strengthened. Within 1 year, SSB consumption declined in Berkeley’s lower-income neighborhoods,3,4 and SSB purchasing dropped 10% in supermarkets.5 These results are consistent with findings of lower consumption and sales of taxed beverages following enactment of beverage taxes in Mexico (in 2013),6 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (2016),7 and Seattle, Washington (2017).8

Given the growing interest in SSB taxes,9 it is critical to use implementation science to identify barriers, facilitators, and resources required to translate taxation policy into public health outcomes.10 To our knowledge, no other study has examined implementation of an SSB tax. Lessons learned from Berkeley could inform the success of future taxes. Therefore, we conducted key-informant interviews and record review, informed by implementation science frameworks, to characterize the implementation process, barriers and facilitators, and lessons learned for achieving public health impact.

METHODS

From June 2015 to April 2017, we conducted semistructured interviews with city staff, its tax administrator, SSB distributors, Berkeley retailers, and SSBPPE commissioners.

We invited staff of the city’s finance, legal, and public health offices, tax administrator, and SSBPPE commissioners for interviews; all participated (n = 9). From stores sampled for a prior study,11 we invited all independent stores (except 1 selling few SSBs) and 1 store from each drugstore, supermarket, and convenience chain (n = 22); 16 participated (3 declined, 3 were unreachable). We also interviewed staff from an independently owned supermarket and university dining (n = 2). Finally, we invited a random sample of 35 self-distributors (i.e., stores and restaurants buying drinks from stores outside Berkeley to sell in Berkeley or making in-house SSBs); 16 participated (8 declined, 11 were unreachable). Of 26 distributors invited, 5 participated (7 refused, 14 were unreachable; the latter included large distributors).

Table 1 describes the sample and gives interview dates and topics. We developed interview guides based on prior retailer feedback,11 beverage industry claims that SSB taxes raise food prices (amounting to a “grocery tax”),12 stakeholder response to excise taxes of other products,13,14 and select constructs of frameworks by Frieden15 and Damschroder et al.16: policy characteristics, context (inner and outer setting of the implementing organization), and implementation process (including communication and engagement). We audio-recorded interviews and transcribed them verbatim. We took detailed notes for 3 retailers and 3 distributors who declined recording. We used both deductive and inductive analysis; using a collaborative and iterative process, we developed a codebook with structural codes (based on question theme and the range of responses) and codes based on themes that emerged. We double-coded interviews using NVivo 11 (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) and resolved disagreements through consensus.

TABLE 1—

Participant Sample, Interview Dates, and Interview Topics Around Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax: Berkeley, CA, 2015–2019

| Interview Datesa | Type of Participant | No. (No. That Were Likely Self-Distributors) | Interview Topics |

| Nov 2015–Jul 2016 | City staff and officials from the Department of Finance, City Attorney’s Office, and Public Health Division | 5 | Implementation time line and roles |

| Tax administrator | 2 | Communications with distributors and retailers | |

| Process for tax collection | |||

| Facilitators and barriers to tax collection and communication | |||

| Recommendations for other cities | |||

| Jul 2016–Aug 2016, with verification in Aug 2019 | SSBPPE commissioners | 2 | Composition of Commission |

| Process for and content of recommendations to city | |||

| Appraisal of City Council’s decisions | |||

| Facilitators and barrier to achieving the Commission’s objectives | |||

| July–Dec 2015 | SSB distributors | 5 | Knowledge of SSB tax |

| Communications with city or tax administrators | |||

| Process for calculating and paying SSB tax | |||

| If and how making up for any costs of SSB tax | |||

| Recommendations about implementation | |||

| Jun 2015–April 2017 | Retailers and likely self-distributors | Knowledge of SSB tax | |

| Retailers and UC dining: Jun–Nov 2015 | Supermarkets (chain or specialty) | 5 | Awareness of distributor price increases |

| Self-distributors and follow-up interview of 6 nonchain retailers: May–Jul 2016 | Small grocery stores | 11 (6) | If and how making up for any SSB tax costs (e.g., higher distributor prices or tax on self-distribution) |

| 1 chain supermarket: Nov 2016 | Liquor stores | 2 | Communications with city and distributors |

| Follow-up with UC dining: April 2017 | Convenience stores | 5 (2) | Recommendations about the implementation process |

| Independent restaurants and cafes | 9 (8) | Process for calculating and paying SSB tax (self-distributors only) | |

| Drugstore | 1 | Awareness of how revenues are being spent via City Council and SSBPPE | |

| UC Berkeley dining | 1 | Opinions about SSB tax | |

| All dates | Total retailers | 34 | • |

Note. SSB = sugar-sweetened beverage; SSBPPE = SSB Product Panel of Experts Commission; UC = University of California. Interviews lasted approximately 15 to 90 minutes and were conducted in-person, except for distributors and SSBPPE commissioners, who were interviewed by phone.

Interview dates were spread out because some stakeholder interviews were timed according to implementation steps (e.g., we interviewed self-distributors after their remittance began). For other stakeholders (e.g., city officials and retailers), their schedules dictated dates.

From January 2015 to January 2019, we identified city records (SSBPPE minutes, Council resolutions and contracts, and Web sites17–19; n = 93 screened, 31 included). We used records to construct a time line and determine revenue allocations and tax administrator cost. We reviewed documents provided by retailers (10 distributor invoices and 2 distributor letters) to characterize the information retailers received.

RESULTS

We present results by the following constructs: policy characteristics, context (inner and outer settings), and implementation process. “Implementation process” comprises tax collection and engagement of distributors and self-distributors, retailer perceptions, and revenue allocations.

Policy Characteristics

Three policy characteristics facilitated implementation of Berkeley’s SSB tax: legitimacy of the policy source,16 policy simplicity,15,16 and the policy “package.”16 First, Berkeley’s SSB tax was championed by the Berkeley Healthy Child Coalition, which comprised parents, teachers, health professionals, the Berkeley NAACP, Latinos Unidos, and others. The tax had unanimous City Council support and garnered 76% of the popular vote. The policy source and mechanism of enactment facilitated implementation: “there is politically a sense of inevitability to it. People … are very aware that 70-something percent of the electorate voted for this, [which] makes it difficult to attack” (city official).

Second, regarding simplicity, the tax administrator described the tax calculation ($0.01/oz) as “actually really simple” compared with tobacco tax rates, which can vary “per pack, per carton, per cigar.” Third, a policy “package” can better promote public health through synergy among its components. The 2 core components of Berkeley’s ordinance, the tax and SSBPPE, worked synergistically: the excise tax reduced SSB consumption while generating revenue, which the SSBPPE directed to new public health programs.

A policy-specific implementation barrier was the ordinance’s effective date of January 1, 2015, less than 2 months after the vote. This time line was not feasible, so enforcement began March 1, 2015—still “extraordinarily quick by municipal standards” (city staff). City staff, retailers, and distributors recommended more lead time (e.g., “6 months” [city official and small grocer]).

Context

The Berkeley city government and the SSBPPE were the implementing organizations (i.e., inner setting). The outer setting comprised Berkeley residents, institutions, and retailers, and the SSB industry.

Outer setting.

Characteristics of Berkeley’s history, institutions, and residents were conducive to public support for SSB tax enactment and implementation. First, Berkeley has a history of policy leadership (e.g., busing for desegregation,20 tobacco control21). City officials and retailers noted that regulation was already the norm. Second, although Berkeley is perceived as a relatively healthy city, there were widely publicized chronic disease inequities,22,23 and the public schools’ popular Cooking and Gardening Program lost all funding because of federal cuts. SSB taxation was pitched as addressing both issues. Fourth, Berkeley is home to the University of California, Berkeley, and its School of Public Health, students, graduates, and professors, contributing to an educated24 and engaged electorate who may have been particularly attuned to the rationale for the tax.

The SSB tax campaign made Berkeley’s 2014 election the most expensive in the city’s history, and the beverage industry sued over the measure’s language.25 However, unlike Philadelphia and Cook County, Illinois,26 Berkeley did not face postenactment lawsuits or well-funded repeal efforts. Otherwise, implementation would have required more resources. However, as the nation’s first, Berkeley’s tax was high profile, with both protax and antitax stakeholders monitoring implementation. This created external pressure on the inner setting—the city—to prioritize implementation: “Researchers, the media, big soda companies: they're all watching. … [Thus,] the whole city is very interested in [making] this is a successful program” (city official).

Inner setting.

The inner setting placed a high priority on implementation. There was early leadership engagement across multiple city departments, especially Finance, the City Attorney’s Office, and, later, Public Health, with leadership from the City Manager’s Office. “They’re interested that implementation happens as smoothly, effectively, and efficiently as possible” (city official).

A city the size of Berkeley did not have available capacity to conduct in-house collection so quickly. Therefore, a city official said, “the city manager made a good executive decision” to hire a tax administration company to coordinate tax outreach and collection, which cost 2% of tax proceeds.

A lesson learned was the importance of funding and hiring personnel in advance of implementation. Existing city staff had to absorb initial implementation responsibilities. Later, after implementation began, the city hired a part-time program specialist (subsequently converted to full-time) in the Berkeley Public Health Division, funded by a grant. City staff recommended that other jurisdictions identify funding for and hire long-term implementation staff in advance of implementation. Although responsibilities and staffing needs would vary by jurisdiction size and context, Berkeley required at least 1 full-time position (with support from junior staff or interns) for coordinating across divisions, managing contracts with community agencies, staffing the SSBPPE, overseeing communications, and advising other jurisdictions.

Implementation Process

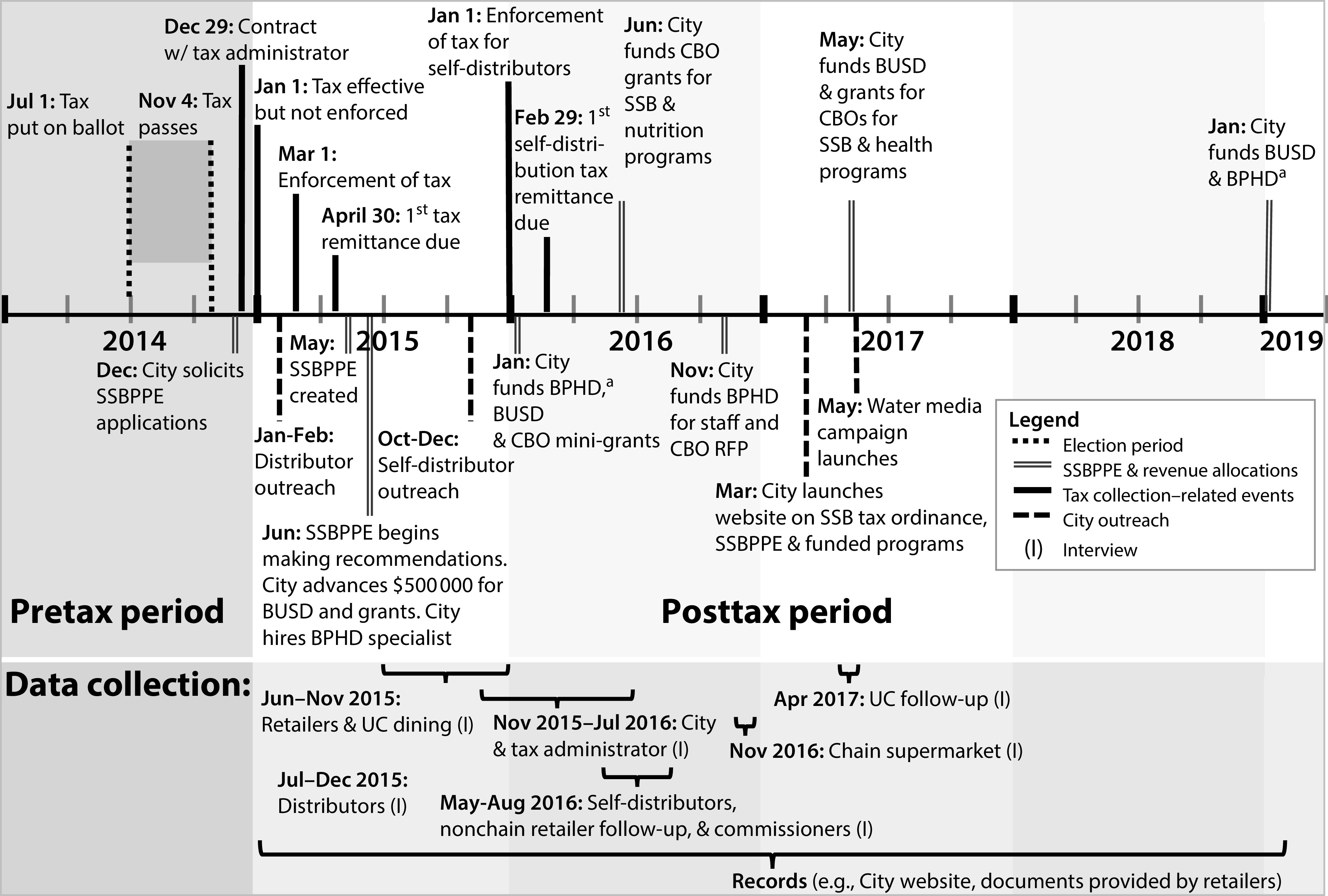

We describe the implementation process by the policy’s core components: tax collection and SSBPPE. Figure 1 shows an implementation time line, and the box on page 1433 summarizes lessons learned.

FIGURE 1—

Time Line of Events Around Implementation of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax: Berkeley, CA, 2015–2019

Note. BPHD = City of Berkeley Public Health Division; BUSD = Berkeley Unified School District (for Gardening & Cooking Program); CBO = community-based organization; RFP = request for proposals; SSB = sugar-sweetened beverage; SSBPPE = SSB Product Panel of Experts Commission.

aTo manage RFP process for community grants, coordinate overall evaluation of funded programs, and in 2016 to develop a branding strategy and education and communications campaign.

BOX 1— Summary of Lessons Learned and Recommendations for Other US Jurisdictions: Sugar-Sweetened Beverage (SSB) Tax: Berkeley, CA, 2015–2019.

| Topic | Lessons Learned or Recommendations Based on Facilitators and Barriers Identified in Analysis |

| Time line | Allow sufficient time (e.g., ≥ 6 mo),a between enactment and implementation. |

| Communication | Communicate early with distributors around time line and calculation and collection of tax. |

| Communicate early with retailers about the tax. Even if not liable, retailers are important stakeholders. | |

| Use multiple modes of communication to reach businesses (e.g., in-person, e-mail, mail, phone, newspaper). | |

| Provide distributors and retailers definitions and guidance to identify taxable and nontaxable beverages, including exemplary lists of beverage categories or products. | |

| Consider providing retailers with materials to show customers who have questions about the tax. | |

| Fund early and robust communications with the public, including retailers, on why the law focuses on SSBs and how revenues are spent. | |

| Tax collection | Consider hiring an experienced tax administrator to collect the tax and coordinate communications, particularly for small or medium cities. |

| Inner setting: staffing | In advance of implementation, identify funds for and hire personnel to adequately staff implementation. |

| Inner setting: advisory committee on revenue allocations | Immediately after enactment, begin the process of establishing an advisory committee to ensure timely, transparent, and accountable distribution of funding from tax revenues, even if revenues are earmarked. |

| Vet and appoint members with broad expertise (e.g., public health, research, equity, nutrition, early care and education, medical, dental). | |

| Do not permit members with beverage industry conflicts of interest. | |

| Encourage formation of subcommittees for efficiency. | |

| Staff or mentor the advisory committee on navigating city rules. | |

| Revenue allocations and funding | Arrange for advanced funding (before tax collection begins) of staffing, communications, and evaluation. |

| In many communities, it may be especially impactful to direct revenues for health equity and policy, systems, and environmental change to support chronic disease prevention. | |

| Allocate revenues to the community in a timely manner. | |

| Quickly fund and roll out (during the first year of the tax) a robust communications and media campaign on health consequences of SSBs, the tax, and revenue allocations. | |

| Ensure that allocations fund programs within the scope specified by the ordinance (if applicable). | |

| Stipulate that funding allocations not replace already existing funds. | |

| Require realistic reporting and evaluation from funded organizations. | |

| Other | Ask for guidance from other cities that have implemented an SSB tax. |

For comparison, other SSB tax laws were effective 5 months after enactment in Albany, CA; 6 months after enactment in Philadelphia, PA; 7 months after enactment in Seattle, WA; 8 months after enactment in Oakland, CA, and Boulder, CO; and 14 months after enactment in San Francisco, CA.

Tax collection.

Effective tax collection matters because taxes can fund critical programs and because it reduces consumer demand for SSBs. Berkeley’s tax collection was divided into phases focusing on (1) distributors and (2) self-distributors. Although distributors are free to assume the costs of the tax, they typically raise SSB prices to retailers, and retailers typically raise SSB shelf prices, lowering demand for SSBs.27,28 Although retailers do not remit the tax, they are constituents affected by the tax, and their actions affect customers. Therefore, we also discuss retailers.

Phase 1—distributors.

In January 2015, the city and the tax administrator sent a flyer to distributors, “manually called everyone, [and] … followed up with an email” about tax outreach sessions in February 2015. “All 30-something distributors were essentially [there] and had tons of questions” (tax administrator). Afterward, there were additional phone calls, mailings, and an online FAQ.18 The city played a leading role in outreach: “The city manager felt we should do the outreach. The primary address should be local. … It was like a partnership, but we were in front. … We approved the language. We know our citizens” (city official).

City officials and the tax administrator perceived successful execution of the implementation plan, noting their wide-reaching communication strategy, high attendance at education sessions, and timely execution of tax collection (e.g., “We did a pretty quick job … collecting without a lot of friction.” Another official characterized the tax as “beyond my dreams,” from “$0 to $1.6 million you can spend educating kids,” referring to the additional money raised by the tax.

Barriers included early distributor confusion about calculating taxes from syrup and misperceptions that use of “natural” caloric sweeteners exempted certain SSBs. A distributor said, “If you grab a bottle of Snapple, it says ‘all natural.’ … To me … that drink would not be subject to the tax.” This distributor described making many phone calls to determine that it was taxable. The distributor also cited challenges programming software to calculate the tax, but ultimately characterized the tax as “just an inconvenience.” Other distributors described the tax as “not hard” and “fairly simple now that it is up and running.” Some distributors were dissatisfied with uncertainty around the enforcement date, echoed in local news.29 None of the 5 distributors interviewed had attended outreach sessions. Some cited not receiving notice, suggesting some communication gaps despite well-attended sessions.

Phase 2—self-distributors.

Enforcement for self-distributors began in January 2016, 10 months after enforcement for distributors began: “We rolled it out in chunks we could manage” (city staff); “We knew who the big [distributors] were. … [The self-distributors] would take more time” (city official). The Berkeley Public Health Division became more involved, and through a foundation grant it hired a program specialist in summer 2015 to be the liaison for self-distributors and to staff the SSBPPE, increasing readiness for phase 2.

The city and the administrator engaged potential self-distributors in November 2015 through a mailing and phone call, inviting them to attend 2 education sessions. Although few attended, those who did found it useful (e.g., “Otherwise I don’t understand the whole thing” [restaurant owner]). An additional mailing with remittance forms was sent in December 2015.

A lesson learned was the need for more widespread outreach. “Maybe we should’ve hired staff, maybe a college student, to go visit each” self-distributor (city official). Most self-distributors did not recall receiving session notifications but acknowledged that mail gets overlooked. Retailers suggested communicating via letters, calls, and newspapers, but e-mail and in-person visits were most preferred (e.g., “It would be nice to just have that one-on-one. … why can’t you send someone to 10 stores a day?”).

When asked about ease of tax remittance, many self-distributors described it as not challenging, “just more work” or “time-consuming.” One wished calculation was easier but said it is “already … the simplest.” Two described confusion about syrup. One suggested quarterly instead of monthly payments.

Retailers.

Retailer interviews revealed (1) how retailers adjusted business practices, (2) a desire for city outreach, (3) barriers to raising SSB prices, and (4) varied appraisals of the tax.

First, retailers reported that major distributors raised SSB prices immediately. When asked if and how retailers were making up for costs, including probes about nonbeverage items, retailers reported raising beverage prices only (n = 24, 71%) or absorbing or delaying beverage price increases (n = 10, 29%; Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Retailers’ reasons for absorbing or delaying price increases included the following: they had not gone through all the invoices, the time needed for—and technical challenges associated with—repricing products in point-of-sale software, regional pricing, not selling enough SSBs to care, and preferring “round” prices. Of 24 retailers raising beverage prices, 18 (75%) reported raising SSB prices only and 5 (21%) reported also raising prices of nontaxable artificially sweetened drinks or not raising all SSB prices. No retailers reported raising food prices.

When we asked city staff if they would consider issuing guidance to businesses, especially retailers, stating that the best practice for public health is to raise SSB prices in response to an excise tax, responses were mixed. Some staff felt that it was not their place to advise on specific business decisions or that it would not be well received. When asked if issuing such guidance would be legally permissible, an interviewee from the Attorney’s Office said that it is permissible as long as the guidance is factual and conveyed as being voluntary for businesses. There is precedent for cities advising businesses for public health.30

Other business changes included discontinued SSB promotions or inventory changes: “You can’t do a 4 [bottles] for $5 [sale] now” (supermarket manager). A convenience store no longer participated in SSB promotions. A restaurateur said, “Now I go for non-sugar stuff.” Two small grocers discontinued soda sales (e.g., “I’ve expanded my dairy department, squeezing out sodas”).

Among retailers that increased customer costs of SSBs, chains raised shelf prices whereas some nonchains added a surcharge at the register. Some reasons for the surcharge were “[otherwise] the customers believe that we’re collecting it for us” and to “have a better chance selling the item.” Others perceived that this was the proper or most feasible method. A city attorney clarified that although stores “can say your price went up by X amount … because of the city tax, they can’t have it as a line item” that misrepresents the consumer as paying a tax “that’s already been paid.”

Second, the city did not engage retailers generally, only self-distributors. However, many retailers wanted early outreach from the city “to let everyone know.” Another said, “I would have liked the city to stop by—just train [us].” Retailers described learning about the tax from distributors, their own research, advocates, the city Web site, and letter or flyer. One café owner said beverage companies “came in to persuade [them] to go and testify” against the tax. Two retailers provided distributor letters, which contained incomplete or inaccurate information, and 1 letter encouraged retailers to “voice their opinions” to the city.

Third, although retailers were generally knowledgeable about the tax (even in summer 2015), some did not know if artificially sweetened drinks and sugar-sweetened coffee and fruit drinks were taxable. Furthermore, retailers described not being able to identify taxable beverages from distributor invoices—an important barrier. Only a few described invoices listing a surcharge under each beverage (typically, invoices contained the total surcharge). Retailers widely expressed wanting help identifying taxable and exempt beverages, including category lists or examples, to facilitate raising SSB prices, “because you can go through that and say, ‘okay, yes, no,’ and exclude or include [a price increase] as you’re getting the products in.” Retailers also wanted information to share with customers “if someone is complaining” and information on how revenues were spent (even in later interviews).

Fourth, retailer appraisal of the tax varied. Many were supportive, mentioning benefits for children or health. A small grocer said, “This law has made a lot of people aware of what they’re actually drinking. … So I think it has brought in a lot of good.” Others mentioned family: “I don’t want [my grandkids] to drink soda. … Let them put more tax on the soda” (café owner). A supermarket manager said, “I support it. … It hasn’t hurt our business. I think it hasn’t upset our customers.”

Criticisms were voiced, particularly by small retailers bordering other cities (e.g., “I’m on the border. … a lot of my clients leave the merchandise on the counter and just go” [small grocery owner]). However, later interviews indicated that customers became accustomed to the tax. Several retailers described wanting the tax to cover a larger jurisdiction (e.g., “I’m in favor if it is implemented everywhere” [convenience store manager]). Others discussed the tax in the context of general cost concerns: “… anything that’s more expensive—minimum wage—that’s going up. Got the sugar tax going. That’s just increased prices for us” (convenience store manager). Other store owners and managers expressed indifference: “We’re kinda used to it. … Berkeley has a bunch of weird laws” (liquor store owner). Two small grocery owners said they wanted revenues to “help the community stores.”

SSBPPE and revenue allocations.

The month the ordinance passed, the mayor appointed a City Council subcommittee to create an appointment process. Councilmembers and the Berkeley Healthy Child Coalition reviewed 42 applications. The Council appointed 9 resident commissioners—1 per district: “It is a very well-balanced, diverse panel of experts. For example, we have an early-childhood nurse; a dentist; a public health researcher with expertise in child nutrition, the prevention of chronic disease and evaluation; and someone who has served on other city commissions. We have a former health officer of Berkeley. The remainder of the Commission are community members … active in the campaign—experts on the intent of the campaign and the voice of the people” (commissioner).

The SSBPPE began meeting monthly in May 2015 and formed subcommittees to get “through all of the things we wanted to do.” The 2 commissioners that we interviewed described prioritizing health disparities, policy, and environments: “We—and we feel that the community at large—all agreed that money should be used to reduce the high burden of disease in low-income populations”; “We didn’t just want to do education. We wanted to make the healthy choice the easy choice.”

The commissioners prioritized swift funding recommendations, to ensure the viability of the Cooking and Gardening Program, and to assure the community that they were adhering to the ordinance’s intent. Funding allocations totaled more than $9 million for use through June 2021 for purposes such as nutrition education in public schools, a healthy beverage media campaign, and community grants for health promotion in communities of color and obesity prevention for Head Start families (Table 2; Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

TABLE 2—

City of Berkeley Funding Allocations Related to the Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Product Panel of Experts (SSBPPE) Commission Recommendations Through January 2019

| Fiscal Year | Resolution No. | Resolution date | Purpose | Funding Amount, $ |

| 2016 | 67 137, 67 136 | Jun 2015 | BUSD Cooking and Gardening Program | 250 000 |

| 2017 | 67 355 | Jan 2016 | BUSD Cooking and Gardening Program | 637 500 |

| 67 355 | Jan 2016 | RFP process managed by BPHD for grants to CBOs to reduce SSB consumption and address its consequences | See total | |

| 67 536 | Jun 2016 | Ecology Center: It’s Your Body—Don’t Hate, Rehydrate! program to increase awareness about SSBs, water, and healthy foods among youths | 115 266 | |

| 67 537 | Jun 2016 | YMCA of the Central Bay Area: (1) Obesity Reduction Program for Head Start preschool-aged children and families; (2) Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) | 151 360 | |

| 67 538 | Jun 2016 | Healthy Black Families: program to reduce SSB-related health inequities | 245 874 | |

| 67 539 | Jun 2016 | Berkeley Youth Alternatives: collaborate with churches to address the nutrition and health needs of African American youths and families | 125 000 | |

| RFP Total | 637 500 | |||

| 2017 | 67 355 | Jan 2016 | BPHD to coordinate RFP process and process evaluation, produce annual report on SSBPPE funding, and hire third-party evaluator | 225 000 |

| 2016–2017 | 67 356 | Jan 2016 | Mini-grants program and third-party grants administrator; funded programs: | 149 900 |

| Bay Area Hispano Institute for Advancement: water access and education | ||||

| Community Adolescents Nutrition Fitness: SSB curriculum creation | ||||

| Community Child Care Council of Alameda County: healthy beverage kits | ||||

| Inter-City Services Inc: Water Wise contest for youths | ||||

| Multicultural Institute: education and access to health care for uninsured | ||||

| Options Recovery Services: workshops, water bottle and station installation | ||||

| Youth Spirit Artwork: educational, youth-driven community mural | ||||

| 2016 | 67 356, 67 481 | Jan 2016, May 2016 | BPHD for SSB program branding strategy and healthy beverage campaign17 | 100 100 |

| 2018–2019 | 67 764 | Nov 2016 | PHD Staffing: program specialist, epidemiologist, and operating expenses | 450 000 |

| 2018–2019 | 67 764 | Nov 2016 | RFP process managed by BPHD for grants to CBOs | See total |

| 68 018 | May 2017 | Ecology Center: Thirst, Water First! to increase awareness of SSBs and promote water consumption among youths | 271 918 | |

| 68 019 | May 2017 | Healthy Black Families: Thirsty for Change! to deliver SSB and healthy eating education, plan health parties, promote policy change, increase physical activity, and create health equity coalition | 510 000 | |

| 68 020 | May 2017 | Multicultural Institute: Life Skills Day Laborer: Health Activity program to provide SSB information and connect immigrants, day laborers, and low-income families to prevention resources | 30 000 | |

| 68 021 | May 2017 | YMCA of the Central Bay Area: obesity prevention and DPP | 280 074 | |

| 68 022 | May 2017 | Lifelong Medical Care: Dental Caries, Prevention Project to expand access to screening, education and treatment of low-income residents | 183 008 | |

| RFP Total | 1 275 000 | |||

| 2018–2019 | 68 017 | May 2017 | BUSD Cooking and Gardening Program and enhancements addressing SSBs | 1 275 000 |

| 2020–2021 | 68 746 | Jan 2019 | BUSD Cooking and Gardening Program and enhancements addressing SSBs | 1 745 200 |

| 2020–2021 | 68 746 | Jan 2019 | RFP process (managed by BPHD) for grants to CBOs | 1 745 200 |

| 2020–2021 | 68 746 | Jan 2019 | BPHD for RFP process, evaluation, and annual report on SSBPPE funding | 872 600 |

Notes. BPHD = City of Berkeley Public Health Division; BUSD = Berkeley Unified School District; CBO = community-based organization; RFP = Requests for Proposals; SSB = sugar-sweetened beverage.

Both interviewed commissioners felt they were fulfilling their mandate: “I’m very happy with the [agencies] funded … they’re really going to move diabetes prevention to the low-income parts of Berkeley.” The commissioners identified facilitating factors, including commissioner expertise, support from the Berkeley Public Health Division, clear Commission rules, and the subcommittee structure.

Regarding barriers and lessons learned, commissioners noted the significant effort to navigate city regulations around requests for proposals, which delayed their community grants work. One commissioner recommended having “a veteran person staff the commission … somebody who’s been on a similar commission that … gives out grants” or having “an ad hoc advisor.” Other recommendations were to get money quickly to the community (which the City Council did by advancing funds before revenues accrued), and to quickly fund a robust media campaign because “even after the tax was voted in, many people didn’t fully understand why it targeted SSBs.” Campaigns can also disseminate information on programs funded, which can sustain public support. The other commissioner said that advisory committees are important, even if revenues are earmarked because “the relationship between some communities and their Council is just so poor.” The commissioner cautioned against appointing individuals with beverage industry ties because “they water everything down and make it less effective; they make it less about their products and more about … exercise.” Lastly, they noted the importance of ensuring that funded programs are within the scope of the ordinance and that new funding not replace existing funding; they also noted the need for program evaluation. A commissioner suggested that ordinances require “monitoring of SSB consumption, obesity, and diabetes” and funding to collect baseline data prior to implementation.

DISCUSSION

Overall successful implementation of the nation’s first SSB tax was facilitated by policy characteristics (e.g., simplicity of the tax, synergy between components), inner and outer settings (e.g., supportive electorate, city prioritization), and policy process (e.g., distributor outreach). The tax ordinance generated more than $9 million in funding allocated for public health and equity from 2015 to 2021, facilitated by the SSBPPE Commission, which represented community and expert voices and provided a measure of accountability over revenue allocations.

Key lessons included the importance of thorough and timely communications with business, adequate lead time for implementation, and the need to immediately fund new staff, communications, outreach, and evaluation before implementation. Early and robust outreach to the public and retailers about the tax and programs funded may promote public support, correct misinformation, educate residents about healthy beverage consumption, reduce friction, and facilitate beverage price increases only on SSBs. Pretax outreach to retailers should include guidance on identifying taxed and exempt beverages and information on how SSB price increases are permitted to appear—or are prohibited from appearing—in prices and receipts (e.g., not as a tax paid by consumers).

No retailers reported raising food prices, indicating that Berkeley’s SSB tax was not a “grocery tax.” Most retailers reported raising SSB prices only, consistent with retail price data.5,11 Incomplete pass-through (i.e., SSB retail prices increasing by less than the full amount of the excise tax)11,31 likely reflected early retailer confusion about whether certain SSBs were taxable.

Limitations

Limitations include lack of interview data more than 2 years after initial implementation and lack of participation from large distributors. The latter may have skewed distributor findings, as campaigns32 and lawsuits indicate strong opposition from large soda companies. Regarding generalizability, all jurisdictions and ordinances2 are unique; for example, Cook County and Philadelphia are large jurisdictions that faced industry-funded repeal efforts and postenactment industry litigation (in Philadelphia, related to state law on taxation authority33). Challenges such as these require more resources to overcome. Also, those taxes were enacted by councilmembers or commissioners, not voters, possibly increasing susceptibility to repeal efforts. Philadelphia’s tax was earmarked for popular programs (e.g., free prekindergarten),34 but Cook County’s beverage tax, which was repealed, was primarily pitched as closing budget gaps.

Public Health Implications

SSB excise taxes reduced SSB purchases and consumption while generating revenues for health, equity, and education. Lessons learned from Berkeley provide a starting place for other jurisdictions considering SSB taxes. The policy package, context, and implementation process, including stakeholder engagement, were key for translating tax policy into public health behavioral outcomes. However, more research is needed to understand the long-term facilitators and barriers to sustaining the public health benefits of Berkeley’s SSB tax and how those differ from facilitators and barriers in jurisdictions with contrasting characteristics (e.g., aggressive repeal campaigns). Future research on SSB taxes should continue to track revenue expenditures and their impacts, as well as how different components of implementation (e.g., communications campaigns) affect public sentiment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH; award K01DK113068), and the Johns Hopkins University Global Obesity Prevention Center and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the NIH, Office of the Director (award U54HD070725).

This work was presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association; October 29–November 2, 2016; Denver, CO.

We thank the participants in this study.

Note. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The study was approved as exempt by the UC Berkeley Committee for Protection of Human Subjects.

Footnotes

See also Bleich et al., p. 1266.

REFERENCES

- 1.Global Food Research Program, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Multi-country obesity prevention initiative: resources. 2019. Available at: http://globalfoodresearchprogram.web.unc.edu/multi-country-initiative/resources. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 2.Hagenaars LL, Jeurissen PPT, Klazinga NS. The taxation of unhealthy energy-dense foods (EDFs) and sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs): an overview of patterns observed in the policy content and policy context of 13 case studies. Health Policy. 2017;121(8):887–894. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falbe J, Thompson HR, Becker CM, Rojas N, McCulloch CE, Madsen KA. Impact of the Berkeley excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverage consumption. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(10):1865–1871. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee MM, Falbe J, Schillinger D, Basu S, McCulloch CE, Madsen KA. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption 3 years after the Berkeley, California, sugar-sweetened beverage tax. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(4):637–639. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.304971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silver LD, Ng SW, Ryan-Ibarra S et al. Changes in prices, sales, consumer spending, and beverage consumption one year after a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages in Berkeley, California, US: a before-and-after study. PLoS Med. 2017;14(4):e1002283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colchero MA, Rivera-Dommarco J, Popkin BM, Ng SW. In Mexico, evidence of sustained consumer response two years after implementing a sugar-sweetened beverage tax. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(3):564–571. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberto CA, Lawman HG, LeVasseur MT et al. Association of a beverage tax on sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages with changes in beverage prices and sales at chain retailers in a large urban setting. JAMA. 2019;321(18):1799–1810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.4249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powell LM, Leider J. The impact of Seattle’s sweetened beverage tax on beverage prices and volume sold. Econ Hum Biol. 2020;37:100856. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2020.100856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falbe J, Madsen K. Growing momentum for sugar-sweetened beverage campaigns and policies: costs and considerations. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(6):835–838. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Estabrooks PA, Brownson RC, Pronk NP. Dissemination and implementation science for public health professionals: an overview and call to action. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:E162. doi: 10.5888/pcd15.180525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falbe J, Rojas N, Grummon AH, Madsen KA. Higher retail prices of sugar-sweetened beverages 3 months after implementation of an excise tax in Berkeley, California. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(11):2194–2201. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maa J. Taxing soda: strategies for dealing with the obesity and diabetes epidemic. Perspect Biol Med. 2016;59(4):448–464. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2016.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeCicca P, Kenkel D, Liu F. Excise tax avoidance: the case of state cigarette taxes. J Health Econ. 2013;32(6):1130–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fullerton D, Metcalf GE. Chapter 26 tax incidence. In: Alan JA, Martin F, editors. Handbook of Public Economics. Vol 4. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2002. pp. 1787–1872. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frieden TR. Six components necessary for effective public health program implementation. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):17–22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.City of Berkeley Public Health Division. Healthy Berkeley. 2019. Available at: http://www.healthyberkeley.com. Accessed February 23, 2019.

- 18.City of Berkeley. Frequently asked questions (FAQ) for the sweetened beverage tax of Berkeley, CA. 2015. Available at: https://www.cityofberkeley.info/uploadedFiles/Finance/Level_3_-_General/Frequently%20Asked%20Questions%20Edited%20Version%20111015.2.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2015.

- 19.City of Berkeley Web site. 2019. Available at: https://www.cityofberkeley.info. Accessed February 29, 2019.

- 20.Burress C. 50th anniversary of Berkeley’s pioneering busing plan for school integration. Berkeley Unified School District. 2018. Available at: https://www.berkeleyschools.net/2018/12/50th-anniversary-of-berkeleys-pioneering-busing-plan-for-school-integration. Accessed January 28, 2019.

- 21.American Lung Association in California. State of tobacco control 2019: California local grades. 2019. Available at: https://www.lung.org/local-content/ca/state-of-tobacco-control/2019/state-of-tobacco-control-2019. Accessed January 6, 2019.

- 22.Berreman J, Ducos J, Seale A. 2013 City of Berkeley health status report. City of Berkeley Public Health Division. 2013. Available at: https://www.cityofberkeley.info/uploadedFiles/Health_Human_Services/Level_3_-_Public_Health/BerkeleyHealthSummary_online_FINAL.pdf. Accessed August 5, 2016.

- 23.Scherr J. Report details Berkeley’s white-black health gap. East Bay Times. November 6, 2013. Available at: https://www.eastbaytimes.com/2013/11/06/report-details-berkeleys-white-black-health-gap. Accessed November 26, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Census Bureau. American Community Survey. Available at: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed February 23, 2019.

- 25.Raguso E. Judge changes Berkeley “soda tax” ballot language. Berkeleyside. September 4, 2014. Available at: https://www.berkeleyside.com/2014/09/04/judge-changes-berkeley-soda-tax-ballot-language. Accessed October 7, 2014.

- 26.Jacobs A. Tuesday could be the beginning of the end of Philadelphia’s soda tax. New York Times. May 20, 2019. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/20/health/soda-tax-philadelphia.html. Accessed May 21, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powell LM, Chaloupka FJ. Food prices and obesity: evidence and policy implications for taxes and subsidies. Milbank Q. 2009;87(1):229–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00554.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dewey C. Why Chicago’s soda tax fizzled after two months—and what it means for the anti-soda movement. Washington Post. October 10, 2017. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/10/10/why-chicagos-soda-tax-fizzled-after-two-months-and-what-it-means-for-the-anti-soda-movement. Accessed February 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee SY. Soda distributors frustrated at city of Berkeley’s lack of guidance on soda tax. Berkeleyside. March 2, 2015. Available at: https://www.berkeleyside.com/2015/03/02/soda-distributors-frustrated-at-berkeleys-lack-of-guidance-on-soda-tax. Accessed March 2, 2015.

- 30.Dannefer R, Williams DA, Baronberg S, Silver L. Healthy bodegas: increasing and promoting healthy foods at corner stores in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(10):e27–e31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cawley J, Frisvold DE. The pass‐through of taxes on sugar‐sweetened beverages to retail prices: the case of Berkeley, California. J Policy Anal Manage. 2017;36(2):303–326. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Falbe J. Sugar-sweetened beverage taxation: evidence-based policy and industry preemption. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(2):191–192. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Erb Phillips K. Double tax argument falls flat as Pennsylvania supreme court rules soda tax legal. Forbes. July 18, 2018. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/kellyphillipserb/2018/07/18/double-tax-argument-falls-flat-as-pennsylvania-supreme-court-rules-soda-tax-legal/#4a05b2371f61. Accessed February 19, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kane RM, Malik VS. Understanding beverage taxation: perspective on the Philadelphia beverage tax’s novel approach. J Public Health Res. 2019;8(1):1466. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2019.1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]